Abstract

Highly satisfying social relationships make us happy and healthy—they fill us with joy and a sense of meaning and purpose. But do all the relationships in our lives contribute equally to our well-being and do some people benefit more from certain relationships? The current study examined associations between the satisfaction of specific relationships within a family (i.e., with parents, siblings) and adjustment (i.e., life satisfaction and depressive symptoms) among 572 emerging adults aged 18–25 (Mage = 19.95, SD = 1.42; 77.4% female). Overall, relationship satisfaction with mothers and fathers was associated with better adjustment. Attachment anxiety and avoidance moderated associations between relationship-specific satisfaction and adjustment. We discuss the findings in the context of the shifting of attachment functions during emerging adulthood and the dynamic nature of close relationships across the lifespan.

Keywords: attachment orientations, relationship-specific satisfaction, emerging adulthood, siblings, family systems

Highly satisfying social relationships make us happy and healthy—they fill us with joy and a sense of meaning and purpose (Carr et al., 2014; Ryan & Deci, 2001). However, happiness can come from many types of relationships. Do all the relationships in our lives contribute equally to our well-being? Does everyone universally benefit from having positive relationships? Recent research has highlighted the utility of examining the influence of multiple relationships on the link between social relationships and adjustment (Chopik, 2017; Kafetsios & Sideridis, 2006; Merz & Consedine, 2009). However, the contribution of different familial relationships to adjustment and possible moderators of these associations have been unexplored. The current study examined the link between familial relationship-specific satisfaction (e.g., with parents and siblings) and adjustment and the moderating role of attachment orientation in these associations among a large sample of emerging adults.

Family Well-being During Emerging Adulthood

The presence of highly satisfying close relationships is a consistent predictor of individual adjustment, subjective well-being, and physical health across the entirety of adolescence and the adult lifespan (Lucas & Dyrenforth, 2006; Pietromonaco & Collins, 2017; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2000). In emerging adulthood in particular, the benefits of close relationships for well-being are often found regardless of the type of relationship being examined. Positive relationships with parents (Amato & Afifi, 2006), siblings (Ponti & Smorti, 2019), friends (van der Horst & Coffé, 2012), and romantic partners are all associated with higher well-being (Demir, 2008). However, much of this research examines these relationships in isolation (e.g., examining only relationships with siblings irrespective of relationships with one’s parents). Despite this practice, individuals are embedded in family systems—managing multiple dynamic relationships over time (Lindell & Campione-Barr, 2017).

This is especially true in emerging adulthood. Emerging adults are navigating a unique life transition as they balance increasing independence and autonomy, the formation of new relationships, and the maintenance of existing relationships (see Arnett, 2000). The structure of family relationships changes during the transition of emerging adulthood. For instance, there is evidence that, despite spending less time with their family members, an individual’s relationship with their sibling becomes increasingly important for well-being during this time (Campione-Barr, 2017). Highly satisfying sibling relationships can often compensate for dissatisfying relationships individuals have with other family members, like their parents (Milevsky, 2005). However, siblings often satisfy interpersonal and emotional needs, even in the context of normative and positive relationships that individuals have with their parents (Padilla-Walker et al., 2017). These patterns are thought to explain why individuals choose to spend more time with their siblings than their parents as they approach young adulthood (McHale et al., 2012).

Family relationships in emerging adulthood are interconnected (Lindell & Campione-Barr, 2017). However, studies of emerging adults often focus on one relationship in isolation (often parents) while neglecting other family members’ roles (i.e., siblings) in predicting well-being. Do each of these relationships uniquely predict well-being? Or are the effects of one relationship (e.g., siblings) on well-being no longer significant after controlling for the effects of other family relationships (e.g., with parents)? The aforementioned discussion of relationships in emerging adulthood suggests a link between relationship functioning, life satisfaction, and depressive symptoms (Morgan et al., 2018; Roberson et al., 2018). To date, however, is a relative dearth regarding how general evaluations of sets of relationships (e.g., satisfaction with parents, siblings) contribute to well-being and depressive symptoms (Moore & Campbell, 2020). In other words, do emerging adults’ satisfaction with various relationships in their lives contribute to adjustment and well-being to a similar degree as other relationship characteristics (e.g., communication) examined in isolation from one another?

The fact that we do not know the relative influence of relationship satisfaction stemming from an individual’s entire immediate family is underscored by the very little research conducted on fathers, who have historically taken a back seat in family research (Lamb, 2000; Volling & Cabrera, 2019). This neglect has resulted in some ignorance about the role that relationships with fathers contribute to adjustment and well-being, particularly among their offspring beyond early childhood (e.g., in emerging adults). Studies linking retrospective memories of mothers’ and fathers’ caregiving to health and well-being across the lifespan suggest that satisfying relationships with fathers are likely influential for well-being (Chopik & Edelstein, 2019). However, the magnitude of these effects is unclear—occasionally the effects of fathers are on par with those of mothers; occasionally they are approximately half the size; and occasionally they are not significant altogether (Kuo et al., 2019). Intuitively, it would make sense that the more satisfying relationships emerging adults have, the better. But gendered dynamics around parenting might make the influences of maternal relationships stronger (as they more often serve as primary caregivers) and the influences of paternal relationships weaker. It is important to examine the magnitude of the effects of satisfaction with father-child relationships on adjustment in the context of the multiple relationships in emerging adults’ lives.

Given the increasing attention paid to the intrapersonal functioning and well-being of emerging adults—and how emerging adults might be at particular risk for lower well-being (Twenge, 2013)—identifying the antecedents of functioning and well-being is more important than ever. Well-being can serve as an indicator of broader adjustment among emerging adults as it is linked to lower feelings of loneliness and fewer behavioral problems, like substance abuse (Clifford et al., 1991; Salimi, 2011). Knowing more about the sources of subjective well-being and depressive symptoms among emerging adults can help guide researchers and practitioners with future family-focused interventions aimed at enhancing adjustment. In the current study, we examined how satisfaction with mothers, fathers, and siblings are simultaneously associated with depressive symptoms and life satisfaction among emerging adults.

Adult Attachment as a Moderator of How Relationships Contribute to Well-being

Along with examining the different sources of well-being in family systems, it is also important to identify individual difference factors that explain why some individuals are more likely to benefit from familial relationships than others. For example, some people might benefit more from relationships with siblings than other people. Likewise, some people may benefit less from having highly satisfying familial relationships. One such individual difference factor is an individual’s attachment orientation, or their characteristic way of approaching close relationships. An individual’s attachment orientation is conceptualized as their position on two conceptually distinct dimensions: avoidance and anxiety. The avoidance dimension is characterized by a dislike of emotional and physical intimacy and a lower likelihood of providing emotional support for close others (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2017). The anxiety dimension is characterized by a preoccupation with the availability of close others and a hypervigilance to signs of rejection and abandonment (Shaver et al., 2005).

There are many reasons to expect that attachment orientation might moderate how particular familial relationships affect well-being. For example, anxiety and avoidance are both associated with lower relationship satisfaction across a variety of relationships, which partially explains their lower levels of well-being (see Mikulincer & Shaver, 2017). However, attachment orientation also affects the relational dynamics between individuals, particularly those they reach out to for emotional and instrumental support (Simpson et al., 2002; Vogel & Wei, 2005). In interpersonally stressful situations, avoidant individuals are less likely to provide and seek out support from relational partners. Although anxious individuals tend to seek out support more often, they feel less satisfied and comforted by the support that they receive. Attachment insecurity also leads to memory biases of interpersonal conflict—insecure adolescents report more negative interactions with their parents six weeks after a conflict has passed compared to immediately after the conflict (Feeney & Cassidy, 2003). In other words, insecure adolescents remember familial conflicts as worse than they were after the fact. Altogether, attachment anxiety and avoidance are associated with less support seeking and provision, greater interpersonal conflict, cognitive biases that cast their relational partners in a negative light, and rumination on the negative features of close relationships (Burnette et al., 2007).

There are many plausible hypotheses that could be made about how attachment orientation would moderate the associations between relationship-specific satisfaction and well-being. First, we hypothesized that relationship satisfaction would be more strongly associated with well-being among those lower in anxiety and avoidance. We made this prediction because relatively secure individuals tend to derive emotional and interpersonal benefits from when their relationships are going well (Simpson & Rholes, 2012). The degree to which the association between relationship satisfaction and well-being would be attenuated among those high in anxiety and avoidance was less clear. We assumed the associations would be attenuated given some of the cognitive, emotional, and relational biases that prevent insecure adults from fully benefitting from positive interactions and experiences with their partners (Shaver et al., 2005). The association between satisfaction and well-being could be slightly reduced, such that the association is lower but still significant, so it is apparent that insecure adults are receiving some benefits from satisfying relationships (but not as much as secure adults). Alternatively, the satisfaction—well-being association could be non-significant, so it is apparent that insecure adults do not receive benefits from satisfying relationships. In the interim, we hypothesized that associations between relationship satisfaction and well-being would be smaller among those high in anxiety and avoidance but were agnostic about the exact degree to which the association would be reduced. There is little research on sibling relationships in emerging adulthood and, to our knowledge, no studies formally comparing the contributions of sibling versus parent-child relationships in predicting well-being (Greif & Woolley, 2016; McHale et al., 2012). Thus, we did not make specific hypotheses about which relationships (e.g., parents v. siblings) securely attached emerging adults would benefit most from.

The Current Study

Although the link between close relationships and well-being has been established in the past, rarely do researchers consider how relationships with particular people in our lives might contribute to our well-being (Chopik, 2017; Ross et al., 2019). Further, adult attachment orientation is often examined as a predictor of intra- and interpersonal adjustment (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2017). However, it was unclear whether attachment orientations might moderate the degree to which different familial close relationships contribute to psychological adjustment. To date, there has not been an examination into how the relationship satisfaction of constituent relationships within the broader family context simultaneously predict individual adjustment in emerging adulthood, let alone adolescence or adulthood. Identifying the most influential relationship—and who particularly benefits from certain relationships—is an important goal for researchers and practitioners alike. We investigated these questions in emerging adults who completed measures about attachment, adjustment, and the familial relationships in their lives.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 572 young adults aged 18–25 (Mage = 19.95, SD = 1.42; 77.4% female) recruited from a university subject pool. An additional 127 participants were excluded for failing to pass an attention check (i.e., “Mark ‘mostly disagree’ for this question.”) meant to root out inattentive responding (Curran, 2016). No other exclusions were made; exclusion criteria were decided in an a priori manner before data analysis. The racial/ethnic breakdown of the sample was 56.1% White/Caucasian, 15% Asian, 14% Black/African American, 6.1% multiracial, 4.7% Hispanic/Latino, and 4% other ethnicities. Most participants lived away from parents (79.4%) and had parents that were married to each other (67.7%). Regarding parental education, 54.7% of mothers and 55.9% of fathers had at least a Bachelor’s degree. The median household income was over $100,000 per year (42.7%) with 13.2% of participants coming from a household with an income of less than $40,000 per year (18.5% did not know their household income).

Study participation was limited to those who reported having a mother, a father, and at least one sibling, to ensure that there was adequate representation of parents and siblings. Participants answered questions about themselves, the sibling to whom they were closest in age (as is common in research on siblings; Buhrmester & Furman, 1990), their mother (if applicable), and their father (if applicable).

Sibling pairs were female(participant)-male(sibling target) (41.1%), female-female (36.4%), male-male (12.8%), or male-female (9.8%). Regarding birth order, 55.2% of the sample was younger than the target sibling. For 48.6% of the sample, the target sibling was their only sibling; the remaining participants (51.4%) had additional siblings. Additional analyses revealed that participant gender, sibling gender, and the gender match/mismatch rarely moderated the main findings. There was some evidence that the effects for relationship satisfaction with siblings were stronger for younger siblings, suggesting that they might particularly benefit from satisfying sibling relationships. But the vast majority of effects were unrelated to the relative age (i.e., birth order) of the siblings. A full summary of these supplementary analyses can be found in the supplement. Sample size was determined by collecting as many participants as we could within one 12-month period. Given a sample size of 572, we could reasonably detect effect sizes as small as f2 = .02 with 80% power at α = .05.

Measures

Relationship-specific Satisfaction

The satisfaction subscale from the Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992) was used as a measure of relationship-specific satisfaction. Participants answered three items about each target (i.e., sibling, mother, and father) relationship. A sample item is “How satisfied are you with your relationship with this person?” Participants rated each item on a scale ranging from 1(hardly at all) to 5(extremely). Responses were averaged to yield composites for satisfaction with siblings (α = .94), mothers (α = .94), and fathers (α = .96). Additional subscales from the NRI were also collected. Given that including all of these scales would introduce serious power issues and be unwieldy, they are not discussed in the current report. NRI relationship satisfaction toward other important figures (e.g., romantic partners, teachers, other family) was not assessed.

Attachment Orientation

Participants completed the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) Inventory (Brennan et al., 1998), a widely used 36-item questionnaire designed to measure attachment anxiety and avoidance in romantic relationships in general. The 18-item ECR avoidance subscale (α = .94) reflects an individual’s discomfort with closeness. The 18-item ECR anxiety subscale (α = .93) reflects an individual’s concern about abandonment. Sample items include “I prefer not to be too close to romantic partners” (avoidance), and “I worry that romantic partners won’t care about me as much as I care about them” (anxiety). Participants rated the extent to which they agree with each statement, using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1(disagree strongly) to 7(agree strongly). Subscales were averaged for anxiety and avoidance. Anxiety and avoidance were moderately correlated (r = .45, p < .001).

Although the ECR was framed in terms of how people behave in romantic relationships generally, the results using this version often mirror the results found when referencing close others more generally and particular relational partners (e.g., mothers). Altogether, this suggests using this partner-version of the ECR is an appropriate way of capturing individual differences in attachment orientation given its high degree of overlap with other versions (Hudson et al., 2015).

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms was measured via the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is a list of 20 statements (e.g., “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me.”) that correspond to depressive symptoms. Participants indicated how frequently they felt each symptom in the last week on a scale ranging from 0(rarely or none of the time (less than one day)) to 3(most or all of the time (5–7 days)). Responses were averaged to create an overall composite of depressive symptoms (α = .90).

Life Satisfaction

The well-established Satisfaction with Life Scale was administered to assess subjective well-being (Diener et al., 1985). A sample item is, “In most ways my life is close to my ideal.” Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each of five items, on a scale ranging from 1(strongly disagree) to 7(strongly agree). Responses were averaged to create an overall composite of life satisfaction (α = .87).

Results

Preliminary Results

Bivariate and moderated regression analyses were conducted in SPSS version 26. Study descriptives and bivariate correlations are presented in Supplementary Table 1. There was a small amount of missing data (n = 5) on the life satisfaction variable; missing data were handled with listwise deletion. All correlations were significant at the p < .001 level unless otherwise indicated. Anxiety and avoidance were each associated with more depressive symptoms (Anx: r = .44, Avo: r = .29), lower life satisfaction (Anx: r = −.31, Avo: r = −.29), and lower relationship satisfaction with siblings (Anx: r = −.23, Avo: r = −.16), mothers (Anx: r = −.24, Avo: r = −.14), and fathers (Anx: r = −.31, Avo: r = −.09, p = .036). Satisfaction with each relationship was associated with greater life satisfaction (rs > |.27|) and fewer depressive symptoms (rs > |.28|). Satisfaction in one relationship was correlated with satisfaction in other relationships (rs > .44). Women were more satisfied in their relationships with their mothers compared (r = .08, p = .049), but no other gender differences emerged (ps > .054).

Regression Analyses

Each outcome (i.e., depressive symptoms and life satisfaction) was predicted separately from gender, anxiety, avoidance, relationship satisfaction with one’s sibling, relationship satisfaction with one’s mother, relationship satisfaction with one’s father, and two-way interactions between relationship-specific satisfaction and attachment orientation (see Tables 1 and 2 for the full models). Variables were centered prior to computing interaction terms. Any significant interactions were decomposed by estimating the slope of relationship-specific satisfaction on each outcome among those +/− 1 SD in anxiety or avoidance. Additional interactions including the product of anxiety and avoidance (e.g., anxiety × avoidance, father satisfaction × anxiety × avoidance) were not significant predictors of depressive symptoms (ps > .47) or life satisfaction (ps > .22).

Table 1.

Linear Regressions Predicting Depressive Symptoms

| 95% Conf. Intv (b) | 95% Conf. Intv (b) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | t | p | LB | UB | b | SE | β | t | p | LB | UB | |

| Intercept | 0.84 | 0.02 | 35.50 | < .001 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.02 | 35.07 | < .001 | 0.79 | 0.89 | ||

| Gender | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 1.77 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 1.56 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.09 |

| Attachment Anxiety | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 7.63 | < .001 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 7.74 | < .001 | 0.12 | 0.19 |

| Attachment Avoidance | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 2.62 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 2.67 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| Sibling Satisfaction | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −1.57 | 0.12 | −0.07 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −1.52 | 0.13 | −0.07 | 0.01 |

| Mother Satisfaction | −0.09 | 0.02 | −0.17 | −3.81 | < .001 | −0.13 | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.09 | −3.46 | 0.001 | −0.12 | −0.03 |

| Father Satisfaction | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.11 | −2.74 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.06 | −2.77 | 0.01 | −0.09 | −0.01 |

| Sibling Satisfaction × Anxiety | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.80 | 0.42 | −0.02 | 0.05 | |||||||

| Mother Satisfaction × Anxiety | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −1.85 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.002 | |||||||

| Father Satisfaction × Anxiety | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −2.13 | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.003 | |||||||

| Sibling Satisfaction × Avoidance | −0.003 | 0.02 | −0.004 | −0.14 | 0.89 | −0.04 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Mother Satisfaction × Avoidance | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.87 | 0.39 | −0.02 | 0.06 | |||||||

| Father Satisfaction × Avoidance | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 1.94 | 0.05 | < .001 | 0.07 | |||||||

Note. Main effects model: F(6,561) = 37.10, p < .001; R2 = .28. Interaction model: F(12,555) = 20.04, p < .001; R2 = .30; ΔR2 = .02, Fchange(6,555) = 2.41, p = .03. Gender: −1= men, 1= women. LB = Lower Bound; UB = Upper Bound.

Table 2.

Linear Regressions Predicting Life Satisfaction

| 95% Conf. Intv (b) | 95% Conf. Intv (b) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | t | p | LB | UB | b | SE | β | t | p | LB | UB | |

| Intercept | 5.17 | 0.05 | 100.35 | < .001 | 5.07 | 5.28 | 5.18 | 0.05 | 100.58 | < .001 | 5.08 | 5.28 | ||

| Gender | −0.004 | 0.05 | −0.003 | −0.07 | 0.94 | −0.11 | 0.10 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.0003 | 0.01 | 0.99 | −0.10 | 0.10 |

| Attachment Anxiety | −0.15 | 0.04 | −0.15 | −3.54 | < .001 | −0.24 | −0.07 | −0.16 | 0.04 | −0.18 | −3.72 | < .001 | −0.24 | −0.08 |

| Attachment Avoidance | −0.18 | 0.04 | −0.18 | −4.21 | < .001 | −0.26 | −0.09 | −0.17 | 0.04 | −0.20 | −4.20 | < .001 | −0.25 | −0.09 |

| Sibling Satisfaction | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.43 | −0.05 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.37 | −0.05 | 0.13 |

| Mother Satisfaction | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 3.22 | 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 2.92 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.24 |

| Father Satisfaction | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 4.53 | < .001 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 4.62 | < .001 | 0.10 | 0.26 |

| Sibling Satisfaction × Anxiety | −0.13 | 0.04 | −0.18 | −3.31 | 0.001 | −0.21 | −0.05 | |||||||

| Mother Satisfaction × Anxiety | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 3.06 | 0.002 | 0.05 | 0.21 | |||||||

| Father Satisfaction × Anxiety | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 1.46 | 0.14 | −0.02 | 0.12 | |||||||

| Sibling Satisfaction × Avoidance | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 2.59 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.18 | |||||||

| Mother Satisfaction × Avoidance | −0.10 | 0.04 | −0.13 | −2.50 | 0.01 | −0.19 | −0.02 | |||||||

| Father Satisfaction × Avoidance | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.08 | −1.56 | 0.12 | −0.13 | 0.02 | |||||||

Note. Main effects model: F(6,558) = 26.39, p < .001; R2 = .22. Interaction model: F(12,552) = 15.52, p < .001; R2 = .25; ΔR2 = .03, Fchange(6,553) = 3.84, p = .001. Gender: −1= men, 1= women. LB = Lower Bound; UB = Upper Bound.

Depressive Symptoms

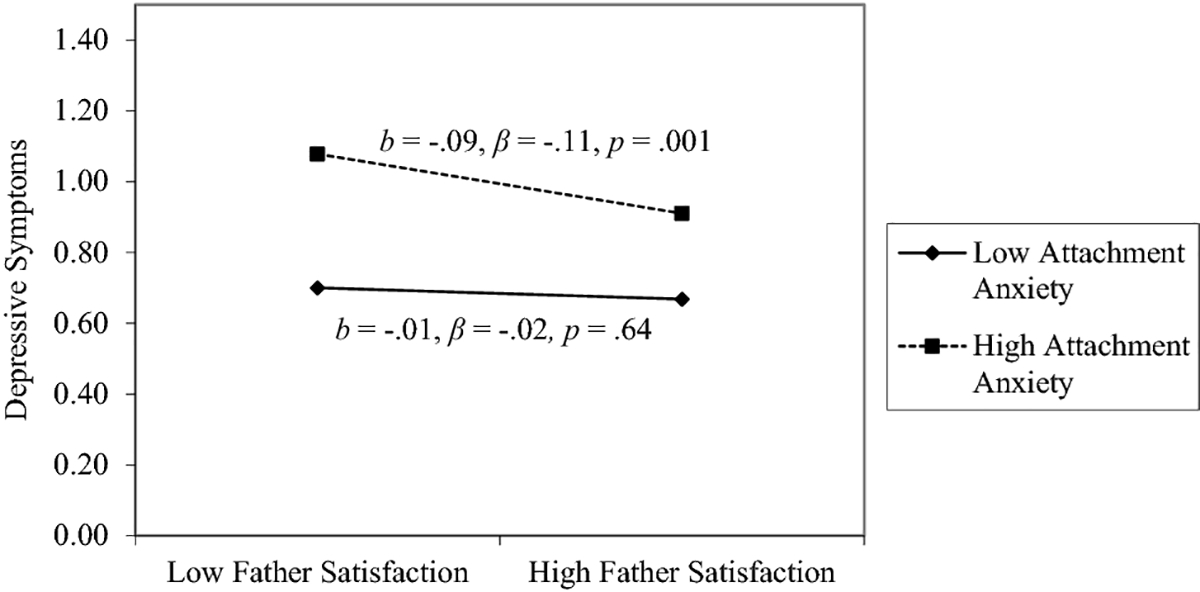

People high in anxiety, high in avoidance, and those dissatisfied with their parental relationships were higher in depressive symptoms (see Table 1; R2MainEffectsModel = .28; the inclusion of the interaction terms explained additional variance in depressive symptoms: ΔR2 = .02, p = .03). The father relationship satisfaction × anxiety interaction was the only significant moderation effect for depressive symptoms. As seen in Figure 1, among individuals high in attachment anxiety, higher relationship satisfaction with fathers was associated with fewer depressive symptoms. Among individuals low in attachment anxiety, relationship satisfaction with fathers was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

The Interaction Between Satisfaction with Father and Attachment Anxiety Predicting Depressive Symptoms

Life Satisfaction

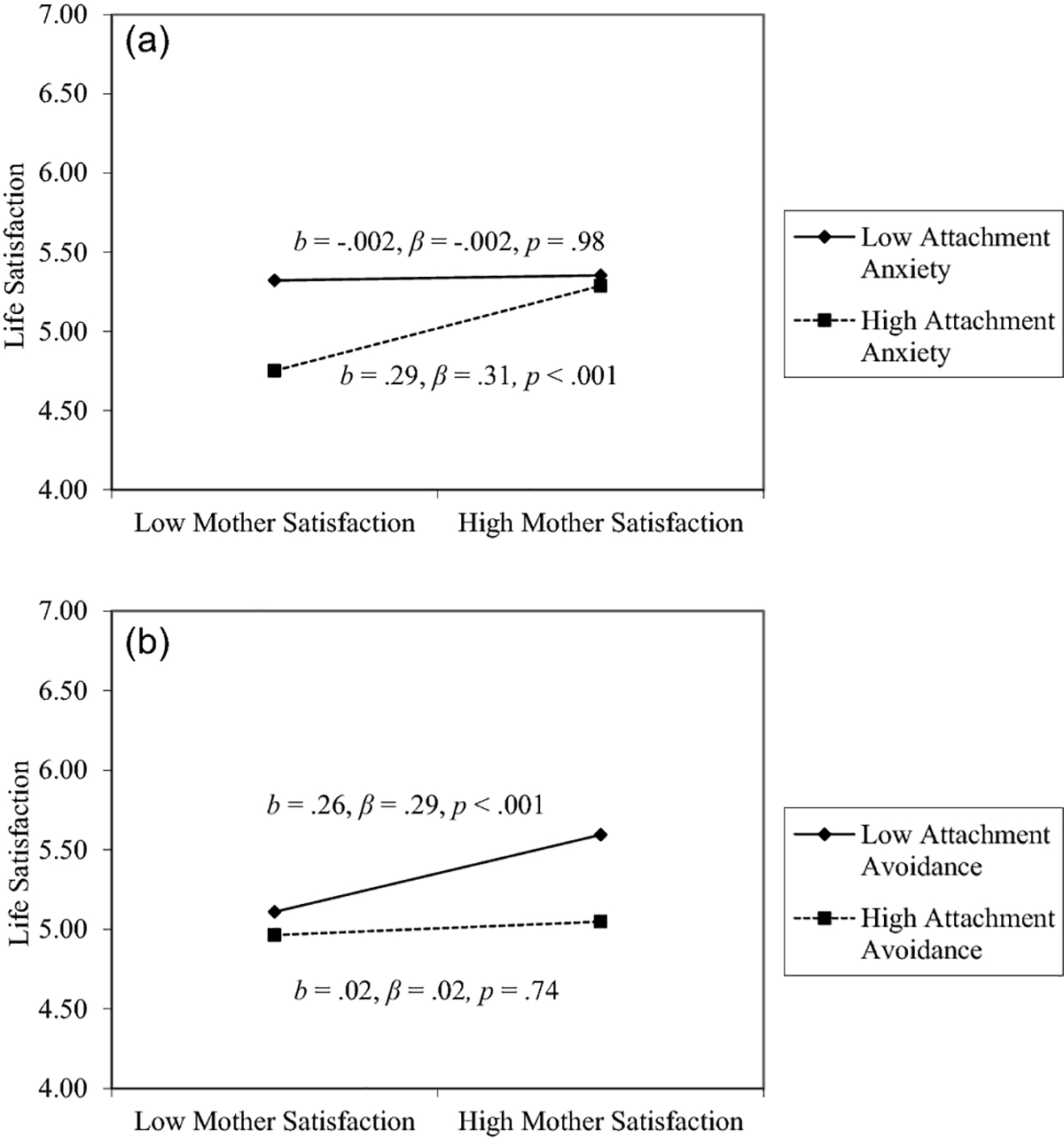

People high in anxiety, high in avoidance, and those dissatisfied with their parental relationships reported lower life satisfaction (see Table 2; R2MainEffectsModel = .22; the inclusion of the interaction terms explained additional variance in life satisfaction: ΔR2 = .03, p = .001). There were four significant two-way interactions predicting life satisfaction: sibling relationship satisfaction × anxiety (Figure 2a), sibling relationship satisfaction × avoidance (Figure 2b), mother relationship satisfaction × anxiety (Figure 3a), and mother relationship satisfaction × avoidance (Figure 3b). Each of these effects is decomposed below.

Figures 2a and 2b.

The Interaction Between Satisfaction with Sibling and Attachment Anxiety Predicting Life Satisfaction (2a) and the Interaction Between Satisfaction with Sibling and Attachment Avoidance Predicting Life Satisfaction (2b)

Figures 3a and 3b.

The Interaction Between Satisfaction with Mother and Attachment Anxiety Predicting Life Satisfaction (3a) and the Interaction Between Satisfaction with Mother and Attachment Avoidance Predicting Life Satisfaction (3b)

As seen in Figure 2a, among those low in anxiety, higher relationship satisfaction with their sibling was associated with higher life satisfaction. Among individuals high in anxiety, relationship satisfaction with their sibling was not significantly associated with life satisfaction. As seen in Figure 2b, among those high in avoidance, relationship satisfaction with their sibling was associated with higher life satisfaction. Among those low in avoidance, relationship satisfaction with their sibling was not significantly associated with life satisfaction. As seen in Figure 3a, among those high in anxiety, higher relationship satisfaction with mothers was associated with higher life satisfaction. Among those low in anxiety, relationship satisfaction with mothers was not significantly associated with life satisfaction. As seen in Figure 3b, among those low in avoidance, relationship satisfaction with mothers was associated with higher life satisfaction. Among those high in avoidance, relationship satisfaction with mothers was not significantly associated with life satisfaction.

Discussion

Satisfaction with parental relationships was consistently associated with fewer depressive symptoms and higher life satisfaction, which is consistent with previous research documenting such associations across the lifespan (Chopik & Edelstein, 2019). After controlling for the effects of parental relationship satisfaction, the association between sibling relationship satisfaction and adjustment was no longer significant, on average. One of the major benefits of the current study was that parental and sibling relationship satisfaction were considered simultaneously. Because satisfaction across relationships is often intercorrelated, controlling for the variance attributable to one relationship (e.g., mother-child) likely explains some of the predictive utility of another relationship (e.g., with a sibling).

Considering all the relationships simultaneously led to some intriguing findings. For example, instead of the effect size of paternal relationships being smaller compared to maternal relationship satisfaction (something occasionally seen among adults; Chopik & Edelstein, 2019), paternal satisfaction was either a comparable (for depressive symptoms) or stronger predictor (for life satisfaction) compared to maternal satisfaction. The comparable effect sizes underscore the importance of considering the relationship satisfaction individuals have with multiple caregivers, whenever possible. The inclusion of fathers, in particular, can provide better context for how parents as a unit contribute to the well-being and functioning of their adult children (Lamb, 2000). As for why paternal relationship satisfaction was a stronger predictor of life satisfaction is currently unknown and we can only speculate. One potential explanation is that, in their desire for more independence and autonomy, emerging adults and parents are often at odds about developmental milestones and the degree to which emerging adults either can, have, or should meet various milestones (Faas et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2007). There is some evidence that emerging adults might have more antagonistic relationships with their mothers around issues of independence and autonomy (Nelson et al., 2007). These antagonistic interactions have stronger links to well-being than antagonistic paternal relationships (Tighe et al., 2016). It is unclear why effects would be stronger for depressive symptoms; future research can better characterize the links between parental relationships and well-being in emerging adulthood.

The fact that relationship satisfaction and attachment orientations were each associated with better adjustment aligns with previous research. More intriguing was how attachment orientation moderated the effects of some specific relationships on well-being and the implications these have for how family systems evolve and change across the entire lifespan.

Why do Attachment Orientations Moderate the Effects of Some Relationships on Well-being but Not Others During Emerging Adulthood?

Individuals’ happiness and depressive symptoms often depended on their relationship satisfaction with their parents, their attachment orientations, and the interactions between relationship-specific satisfaction and attachment orientations. For example, the effects of sibling relationship satisfaction and maternal relationship satisfaction on well-being were indeed stronger for secure individuals (and attenuated and non-significant among those high in anxiety and avoidance, respectively). This pattern was consistent with our expectations that insecure adults might benefit less from the positive relationship evaluations (Shaver et al., 2005). Occasionally, the association between relationship satisfaction and well-being was attenuated in ways that differed from what we had originally hypothesized. For example, associations between paternal relationship satisfaction and depressive symptoms, maternal satisfaction and life satisfaction, and sibling satisfaction and life satisfaction were stronger among relatively insecure emerging adults (and attenuated to non-significance among secure emerging adults).

We can only speculate why some relationships were more beneficial among highly anxious (i.e., parental relationships) and highly avoidant individuals (i.e., sibling relationships). Some reasons might lie in the specific attachment-related transitions that occur during emerging adulthood and possible individual differences in how well individuals make these transitions (Fraley & Davis, 1997). For example, several researchers have outlined a specific process through which individuals shift their attachment needs from their parents to their peers and romantic partners (see Heffernan et al., 2012, for a review). Specifically, individuals increasingly seek proximity to peers (i.e., proximity seeking), begin to use peers as a haven to turn to when they are distressed (i.e., safe haven), and finally begin to use peers as a secure base from which to explore new interpersonal situations (i.e., secure base behavior). Indeed, many other researchers have found support for this gradual transference of attachment needs as individuals age from childhood through emerging adulthood (Friedlmeier & Granqvist, 2006; Hazan & Zeifman, 1994, 2016). Although this work has exclusively focused on parents, peers, and romantic partners, presumably some of the same transference processes also apply to sibling relationships, given that siblings can serve attachment functions, particularly in the absence of highly satisfying parental relationships (Milevsky, 2005; Tancredy & Fraley, 2006).

The majority of the work on attachment transference has focused on characterizing the normative transitions people go through, rather than individual differences in the transition sequence. However, some research suggests that avoidant individuals often struggle with fully transitioning their attachment needs from their caregivers to more peer-like individuals (Fraley & Davis, 1997; Schindler et al., 2010). With avoidant individuals’ desire to seek out less dependency in relationships and situations (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2017), they may gravitate away from their parents and more toward less asymmetrical relationships (e.g., siblings) when transferring their attachment needs, particularly during emerging adulthood. As a result, avoidant individuals may be more influenced by satisfying relationships with their siblings in emerging adulthood. One possible prediction for future research is that sibling relationships might serve as a bridge in the transference process for avoidant individuals—as siblings are members of their family of origin, occasionally serve in caregiving type capacities, but are simultaneously more peer-like than parent-child relationships. Indeed, in the current study, the benefits of sibling relationships were found only among younger siblings (see supplement), for whom an older sibling could potentially serve as a caregiver yet may also be closer to a peer than a parent. As a consequence, sibling relationships might be particularly important for avoidant individuals given their unique juxtaposition between caregiver and peer-like relationships.

There is also evidence to suggest that anxious individuals also struggle with transferring attachment needs, but this research suggests that anxious individuals more readily attempt transfers of attachment needs indiscriminately, even in early, fledgling relationships (Eastwick & Finkel, 2008). Given their persistent ambivalent attitudes toward their parents (Maio et al., 2000), anxious individuals may continue to use their parents to satisfy attachment needs and be particularly negatively affected when these relationships are going poorly, as we found in the current study. The jealousy that anxious individuals feel over the differential affection and attention their siblings receive from their parents may be one explanation for why anxious individuals are less satisfied with their sibling relationships (Rauer & Volling, 2007). As an extension, only individuals low in anxiety benefit from these positive relationships with their siblings. One possible prediction for future research is that, whereas avoidant individuals might use siblings as a bridge in transferring attachment needs from parents to peers, anxious individuals may undergo more direct transference from parents to peers. Unfortunately, in the current study, we did not include measures of attachment features and functions of each relationship (Tancredy & Fraley, 2006), but future research can more directly examine the transitions that anxious and avoidant individuals undergo during emerging adulthood.

Again, the exact reasons why some relationships were more beneficial than others for anxious versus avoidant individuals are beyond what can be reasonably discussed and tested here. However, we hope that these initial findings provide a map for future research to more formally test how family systems and attachment orientations interact to predict adjustment.

How do Family Systems Change Throughout Emerging Adulthood and Beyond?

Still unaddressed by the current study is how adjustment in each of these relationships waxes and wanes in the years after emerging adulthood and what implications these changes have for an individual’s well-being. Although the satisfaction of sibling relationships was not associated with life satisfaction or depressive symptoms in the current sample, sibling relationship satisfaction could be more important at different life stages or predict important outcomes longitudinally. For example, poor sibling relationships prior to age 20 predict substance abuse and major depression at age 50 (Waldinger et al., 2007). Sibling relationships not only affect relationships with people inside the family but also relationships outside the family (Ponti & Smorti, 2019; Robertson et al., 2014). For example, among adolescents, experiencing greater intimacy with a sibling is associated with experiencing greater intimacy in a romantic relationship two years later (Doughty et al., 2015). The authors of that particular paper noted many similarities between sibling and romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. Sibling relationships often provide individuals with the tools for managing conflict, negotiating power and control dynamics, and forming emotional ties and a feeling of companionship (Lockwood et al., 2001; Updegraff et al., 2002). Thus, sibling relationships might provide a scaffolding of skills in early developmental periods of adulthood that individuals then apply in relationships moving forward. That skills and experiences learned in previous relationships are transferred to new relationships is also consistent with the aforementioned discussion on the shift of attachment functions across relationships (Heffernan et al., 2012).

Inherent in the discussion of the non-independence of different relationships is the need for more descriptive information for how the structure of relationships in emerging adulthood resembles the structure of relationships at different points in the adult lifespan. Studies purporting to measure changes in social network characteristics often examine relationships in isolation of one another or lump distinct relationships (e.g., mothers, fathers, siblings) into a superordinate category (e.g., general family relationships) (Chopik, 2017; Chopik & Edelstein, 2019). Other studies that do examine the multiple relationships in which people are embedded across the lifespan (e.g., via social network analysis) often do not make distinctions about the qualitative nature of these relationships (see Smith et al., 2015, for an exception). The current study can only speak to the utility of examining these separate relationships simultaneously during emerging adulthood. Future research can examine the predictive utility of each of these relationships (and others) at various points in the lifespan. As the functions of different relationships change in different ways across the lifespan (White, 2001), an appreciation for how the entirety of relationships in an individual’s life evolve and change together is an exciting avenue for future research.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations are worth acknowledging. First, our study was a cross-sectional examination that linked relationship-specific satisfaction to life satisfaction. As a result, the direction of the link between relationship satisfaction and adjustment cannot be known from our current study. For example, more depressive symptoms could be causing poor relationships with parents and siblings. Second, our data came from a sample of single informants comprised entirely of college students and predominantly females. One immediate concern of having only one person provide reports of relationship satisfaction (and attachment and well-being) is the problem of shared method bias/variance. This concern could be alleviated by having multiple reporters (i.e., siblings, mothers, fathers) provide ratings of how satisfied they are in their relationships with the participant. Worth noting, there is often high agreement on relationship satisfaction ratings provided by members of a relationship (Orth, 2013) which might reduce the amount of concern over the study’s single-informant design. Nevertheless, different perspectives on how well a relationship is going is an important consideration for future research.

Third, our analysis focused exclusively on emerging adulthood because this particular developmental period—and how relationships are changing throughout this period—was most interesting from an attachment and adjustment perspective. However, future research can examine how these relationships change in concert with (or in opposition to) one another across the adult lifespan (Hudson et al., 2015). Having long-term longitudinal data with a comprehensive set of relationship characteristics will allow us to test many of the mechanisms and processes that we proposed for future research. Likewise, our sample was a relatively narrow population of emerging adults. This is an important limitation to acknowledge, given that some of the specific transitions and family dynamics experienced by emerging adults likely differ by sub-populations (e.g., non-college students, those living far from their family of origin, and those differing in culture and socio-economic class; Arnett, 2016). Finally, relationships with close others are often organized hierarchically in people’s lives and minds (Hazan & Zeifman, 1994). The relative placement of close others within this hierarchy—and the satisfaction of these relationships—likely have implications for people’s well-being across the lifespan (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2017). Thus, having additional relationships beyond those considered here (e.g., romantic partners, friends/peers, and additional siblings) are likely worth integrating into studies of relationship hierarchies in emerging adulthood.

Conclusion

The current study examined the associations between relationship-specific satisfaction and adjustment and the moderating effect of attachment orientation in these associations. The specific ways in which some relationships contribute to well-being and how these patterns differ by attachment orientation may have implications for individuals as they shift their attachment needs across relationships. Future research can examine how the satisfaction and functions of different relationships change over time and across the lifespan.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

The study was funded by the National Institute of Aging of the National Institute of Health under Award Number 2R03AG054705-01A1. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Research Involving Human Subjects: This research was approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board (IRB #17-172e).

Informed Consent: All participants provided their informed consent before participating in this study.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. There are also no financial disclosures to report.

Data are proprietary but can be requested from the first author.

Contributor Information

William J. Chopik, Michigan State University

Amy K. Nuttall, Michigan State University

Jeewon Oh, Michigan State University.

References

- Amato PR, & Afifi TD (2006). Feeling caught between parents: Adult children’s relations with parents and subjective well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(1), 222–235. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00243.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. 10.1037/0003-066x.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2016). Does emerging adulthood theory apply across social classes? National data on a persistent question. Emerging Adulthood, 4(4), 227–235. 10.1177/2167696815613000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, & Shaver PR (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In Simpson JA & Rholes WS (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships. (pp. 46–76). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, & Furman W (1990). Perceptions of sibling relationships during middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development, 61(5), 1387–1398. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02869.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette JL, Taylor KW, Worthington EL, & Forsyth DR (2007). Attachment and trait forgivingness: The mediating role of angry rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(8), 1585–1596. 10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campione-Barr N (2017). The changing nature of power, control, and influence in sibling relationships. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 156, 7–14. 10.1002/cad.20202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, Freedman VA, Cornman JC, & Schwarz N (2014). Happy marriage, happy life? Marital quality and subjective well-being in later life. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 76(5), 930–948. 10.1111/jomf.12133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopik WJ (2017). Associations among relational values, support, health, and well-being across the adult lifespan. Personal Relationships, 24(2), 408–422. 10.1111/pere.12187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chopik WJ, & Edelstein RS (2019). Retrospective memories of parental care and health from mid to late life. Health Psychology, 38(1), 84–93. 10.1037/hea0000694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PR, Edmundson EW, Koch WR, & Dodd BG (1991). Drug use and life satisfaction among college students. International Journal of the Addictions, 26(1), 45–53. 10.3109/10826089109056238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PG (2016). Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 66, 4–19. 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.07.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M (2008). Sweetheart, you really make me happy: Romantic relationship quality and personality as predictors of happiness among emerging adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(2), 257–277. 10.1007/s10902-007-9051-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, & Griffin S (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty SE, McHale SM, & Feinberg ME (2015). Sibling experiences as predictors of romantic relationship qualities in adolescence. Journal of Family Issues, 36(5), 589–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwick PW, & Finkel EJ (2008). The attachment system in fledgling relationships: An activating role for attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 628–647. 10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faas C, McFall J, Peer JW, Schmolesky MT, Chalk HM, Hermann A, Chopik WJ, Leighton DC, Lazzara J, Kemp A, DiLillio V, & Grahe J (2020). Emerging Adulthood MoA/IDEA-8 scale characteristics from multiple institutions. Emerging Adulthood, 8(4), 259–269. 10.1177/2167696818811192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney BC, & Cassidy J (2003). Reconstructive memory related to adolescent-parent conflict interactions: The influence of attachment-related representations on immediate perceptions and changes in perceptions over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 945–955. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, & Davis KE (1997). Attachment formation and transfer in young adults’ close friendships and romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 4(2), 131–144. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1997.tb00135.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlmeier W, & Granqvist P (2006). Attachment transfer among Swedish and German adolescents: A prospective longitudinal study. Personal Relationships, 13(3), 261–279. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00117.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, & Buhrmester D (1992). Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development, 63(1), 103–115. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greif GL, & Woolley ME (2016). Adult siblings relationships. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, & Zeifman D (1994). Attachment processes in adulthood. In Bartholomew K & Perlman D (Eds.), Advances in personal relationships (Vol. 5, pp. 151–178). Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, & Zeifman D (2016). Pairbonds as attachments: Mounting evidence in support of Bowlby’s hypothesis. In Cassidy J & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (Vol. 3rd, pp. 416–434). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan ME, Fraley RC, Vicary AM, & Brumbaugh CC (2012). Attachment features and functions in adult romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29(5), 671–693. 10.1177/0265407512443435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson NW, Fraley RC, Chopik WJ, & Heffernan ME (2015). Not all attachment relationships develop alike: Normative cross-sectional age trajectories in attachment to romantic partners, best friends, and parents. Journal of Research in Personality, 59, 44–55. 10.1016/j.jrp.2015.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kafetsios K, & Sideridis GD (2006). Attachment, social support and well-being in young and older adults. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(6), 863–875. 10.1177/1359105306069084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo PX, Saini EK, Tengelitsch E, & Volling BL (2019). Is one secure attachment enough? Infant cortisol reactivity and the security of infant-mother and infant-father attachments at the end of the first year. Attachment & Human Development, 21(5), 426–444. 10.1080/14616734.2019.1582595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME (2000). The history of research on father involvement: An overview. Marriage & Family Review, 29(2–3), 23–42. 10.1300/J002v29n02_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindell AK, & Campione-Barr N (2017). Continuity and change in the family system across the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Marriage & Family Review, 53(4), 388–416. 10.1080/01494929.2016.1184212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood RL, Kitzmann KM, & Cohen R (2001). The impact of sibling warmth and conflict on children’s social competence with peers. Child Study Journal, 31(1), 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RE, & Dyrenforth PS (2006). Does the existence of social relationships matter for subjective well-being? In Vohs KD & Finkel EJ (Eds.), Self and relationships: Connecting intrapersonal and interpersonal processes. (pp. 254–273). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maio GR, Fincham FD, & Lycett EJ (2000). Attitudinal ambivalence toward parents and attachment style. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(12), 1451–1464. 10.1177/01461672002612001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Updegraff KA, & Whiteman SD (2012). Sibling relationships and influences in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 74(5), 913–930. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01011.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz EM, & Consedine NS (2009). The association of family support and wellbeing in later life depends on adult attachment style. Attachment and Human Development, 11(2), 203–221. 10.1080/14616730802625185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, & Shaver PR (2017). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milevsky A (2005). Compensatory patterns of sibling support in emerging adulthood: Variations in loneliness, self-esteem, depression and life satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22(6), 743–755. 10.1177/0265407505056447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KA, & Campbell A (2020). The Investment Model: Its antecedents and predictors of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Relationships Research, 11, E12. 10.1017/jrr.2020.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan P, Love HA, Durtschi J, & May S (2018). Dyadic causal sequencing of depressive symptoms and relationship satisfaction in romantic partners across four years. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 46(5), 486–504. 10.1080/01926187.2018.1563004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LJ, Padilla-Walker LM, Carroll JS, Madsen SD, Barry CM, & Badger S (2007). “If you want me to treat you like an adult, start acting like one!” Comparing the criteria that emerging adults and their parents have for adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 665–674. 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U (2013). How large are actor and partner effects of personality on relationship satisfaction? The importance of controlling for shared method variance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(10), 1359–1372. 10.1177/0146167213492429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker LM, Memmott-Elison MK, & Nelson LJ (2017). Positive relationships as an indicator of flourishing during emerging adulthood. In Padilla-Walker LM & Nelson LJ (Eds.), Flourishing in emerging adulthood: Positive development during the third decade of life. (pp. 212–236). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco PR, & Collins NL (2017). Interpersonal mechanisms linking close relationships to health. American Psychologist, 72, 531–542. 10.1037/amp0000129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, & Sörensen S (2000). Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 15(2), 187–224. 10.1037/0882-7974.15.2.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponti L, & Smorti M (2019). The roles of parental attachment and sibling relationships on life satisfaction in emerging adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(6), 1747–1763. 10.1177/0265407518771741 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rauer AJ, & Volling BL (2007). Differential parenting and sibling jealousy: Developmental correlates of young adults’ romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 14(4), 495–511. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00168.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson PNE, Lenger KA, Norona JC, & Olmstead SB (2018). A longitudinal examination of the directional effects between relationship quality and well-being for a national sample of U.S. men and women. Sex Roles, 78(1), 67–80. 10.1007/s11199-017-0777-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson R, Shepherd D, & Goedeke S (2014). Fighting like brother and sister: Sibling relationships and future adult romantic relationship quality. Australian Psychologist, 49(1), 37–43. 10.1111/j.1742-9544.2012.00084.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross KM, Rook K, Winczewski L, Collins N, & Dunkel Schetter C (2019). Close relationships and health: The interactive effect of positive and negative aspects. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13(6), e12468. 10.1111/spc3.12468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Deci EL (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salimi A (2011). Social-emotional loneliness and life satisfaction. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 292–295. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler I, Fagundes CP, & Murdock KW (2010). Predictors of romantic relationship formation: Attachment style, prior relationships, and dating goals. Personal Relationships, 17(1), 97–105. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01255.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Schachner DA, & Mikulincer M (2005). Attachment style, excessive reassurance seeking, relationship processes, and depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(3), 343–359. 10.1177/0146167204271709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, & Rholes WS (2012). Adult attachment orientations, stress, and romantic relationships. In Devine P & Plant A (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol 45. (pp. 279–328). Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394286-9.00006-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Oriña MM, & Grich J (2002). Working models of attachment, support giving, and support seeking in a stressful situation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(5), 598–608. 10.1177/0146167202288004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EJ, Marcum CS, Boessen A, Almquist ZW, Hipp JR, Nagle NN, & Butts CT (2015). The relationship of age to personal network size, relational multiplexity, and proximity to alters in the Western United States. Journals of Gerontology, 70(1), 91–99. 10.1093/geronb/gbu142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tancredy CM, & Fraley RC (2006). The nature of adult twin relationships: An attachment-theoretical perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 78–93. 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tighe LA, Birditt KS, & Antonucci TC (2016). Intergenerational ambivalence in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for depressive symptoms over time. Developmental Psychology, 52(5), 824–834. 10.1037/a0040146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM (2013). The evidence for generation me and against generation we. Emerging Adulthood, 1(1), 11–16. 10.1177/2167696812466548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, & Crouter AC (2002). Adolescents’ sibling relationship and friendship experiences: Developmental patterns and relationship linkages. Social Development, 11(2), 182–204. 10.1111/1467-9507.00194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Horst M, & Coffé H (2012). How friendship network characteristics influence subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 107(3), 509–529. 10.1007/s11205-011-9861-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DL, & Wei M (2005). Adult attachment and help-seeking intent: The mediating roles of psychological distress and perceived social support. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(3), 347. 10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volling BL, & Cabrera NJ (2019). Advancing research and measurement on fathering and children’s development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 84, 7–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger RJ, Vaillant GE, & Orav EJ (2007). Childhood sibling relationships as a predictor of major depression in adulthood: A 30-year prospective study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(6), 949–954. 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L (2001). Sibling relationships over the life course: A panel analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 555–568. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00555.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.