Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic generated a surge of critically ill patients greater than the capacity of the UK National Health Service (NHS). There have been multiple well-documented impacts associated with the national COVID-19 pandemic surge on ICU staff, including an increased prevalence of mental health disorders on a scale potentially sufficient to impair high-quality care delivery. We investigated the prevalence of five mental health outcomes; explored demographic and professional predictors of poor mental health outcomes; and describe the prevalence of functional impairment; and explore demographic and professional predictors of functional impairment in ICU staff over the 2020/2021 winter COVID-19 surge in England.

Methods

English ICU staff were surveyed before, during, and after the winter 2020/2021 surge using a survey which comprised validated measures of mental health.

Results

A total of 6080 surveys were completed, by ICU nurses (57.5%), doctors (27.9%), and other healthcare staff (14.5%). Reporting probable mental health disorders increased from 51% (before) to 64% (during), and then decreased to 46% (after). Younger, less experienced nursing staff were most likely to report probable mental health disorders. During and after the winter, >50% of participants met threshold criteria for functional impairment. Staff who reported probable post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or depression were more likely to meet threshold criteria for functional impairment.

Conclusions

The winter of 2020/2021 was associated with an increase in poor mental health outcomes and functional impairment amongst ICU staff during a period of peak caseload. These effects are likely to impact on patient care outcomes and the longer-term resilience of the healthcare workforce.

Keywords: COVID-19, functional impairment, healthcare worker, intensive care, mental health, presenteeism, PTSD

Editor's key points.

-

•

During the COVID-19 pandemic intensive care staff have experienced huge challenges in workload.

-

•

In this cross-sectional study, there was an increase in mental health disorders reported by ICU staff corresponding with the peak of the COVID-19 surge.

-

•

Further research is needed to understand the long-term mental health impacts of the pandemic on healthcare staff, and how best to mitigate these.

Psychological distress has increased in the general population over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic,1 with key workers reporting higher rates of probable mental health disorders than the general population.2 Healthcare workers, particularly those working on the frontline, have experienced high rates of mental health challenges such as depression, anxiety, stress, and burnout.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Furthermore, health and social care workers were already reporting high levels of pre-existing mental health disorders that may have increased their risk of experiencing mental health during a public health emergency.4

During the pandemic, staff working on ICUs, including doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals, have arguably been the most directly impacted by the surge in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Nurses appear to have been particularly exposed and have reported higher rates of symptoms consistent with common mental disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared with other ICU staff.8 During the pandemic, ICU staff have faced a constellation of specific stressors. These include the perceived risk to their own health from exposure to COVID-19, very high mortality rates among the patients in their care,9 reduced staffing ratios, shortages of personal protective equipment, and the need to work beyond their level of seniority.10 Poor mental health of ICU staff has the potential to impact the quality and safety of patient care. The phenomenon of presenteeism, in which staff continue to work while functionally impaired by the state of their mental health, may lead to an increased risk of errors and poorer performance, which in turn may impact the quality and safety of patient care.11 12 With COVID-19, and the backlog of care resulting from the pandemic, exerting ongoing pressures on ICU resources, it is important to understand how the mental health of ICU workers has been impacted. This is essential in the identification of risk factors in this population, to help ensure that appropriate support is made available for all,13 and to inform future pandemic planning.

This study builds on the initial ICU mental health survey conducted by Greenberg and colleagues,8 which found substantial rates of probable mental health disorders in ICU staff. The current study analysed data from three subsequent timepoints of the survey corresponding to before, during, and after the peak of the COVID-19 winter 2020/2021 surge in England, to explore the impact of this surge on the mental wellbeing of staff working in ICUs.14 Therefore, the current study aimed to: describe the prevalence of five mental health outcomes: probable depression, probable post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), probable general anxiety disorder, and problem drinking, in ICU staff over the winter 2020/2021 surge in England; explore demographic and professional predictors of poorer mental health outcomes in ICU staff over the 2020/2021 winter surge in England; describe the prevalence of functional impairment in ICU staff over the 2020/2021 winter surge in England; and explore demographic and professional predictors of functional impairment in ICU staff over the 2020/2021 winter surge in England.

Methods

Study setting

An online cross-sectional survey was designed and run in 56 English ICUs, which experienced a surge in adult patients, above their formally commissioned baseline. Collection occurred across three timepoints: before the surge-November 19, 2020 to December 17, 2020; during the surge-January 26, 2021 to February 17, 2021; and after the surge-April 14, 2021 to May 24, 2021. These data collection points were part of an ongoing service evaluation of ICU staff's mental health which commenced in June 2020.8 This study was approved by the Psychiatry, Nursing and Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee, King's College London reference number: MOD-20/21-18162. The 56 UK National health Service (NHS) hospitals which provided data comprised District General Hospitals, Teaching Hospitals, and Quaternary Paediatric Hospitals. The selection process reflected hospitals utilising surge capacity and hospitals receiving or making use of interhospital transfers as part of mutual aid support between neighbouring units. Where possible, data for hospital baseline ICU bed number (as declared in 2020, immediately before the pandemic) and actual maximum occupancy during COVID-19 were collected. All surveyed units exceeded 100% of their baseline ICU capacity during the winter 2020/2021 surge.

Survey design

Data were collected via an anonymised web-based survey, designed to be completed in <5 min, comprising validated questionnaires assessing mental health status and psychological wellbeing. Participants were aware that their participation was voluntary, their data would be anonymised, they were free to stop at any point during the completion of the study, and any incomplete surveys would be discarded. The Lime Survey tool (https://www.limesurvey.org/) was used to build the survey and hosted on a dedicated secure university server.

Survey distribution

Circulation and completion of the survey was encouraged through engagement with clinical leads in each of the ICUs. The survey was distributed through departmental email and messaging groups. All staff working in ICUs (doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals) were eligible to take part. Because of the recruitment method, the size of the sample was determined by the participants who chose to complete the survey. Individual respondents could not be followed across timepoints as the survey was anonymous in order to reduce barriers to reporting.15 16 No participant data were excluded. Figure 1 displays a participant flow chart.

Fig 1.

CONSORT 2020 participant flow diagram.

Collected variables and outcome definitions

Demographic data collected included age, gender, job role, and seniority. Doctors who were graded FY 1–2, ST 3–4, ST 5–6, ST 6–7 were classed as junior staff (staff still in training) and consultant and senior associate specialists as senior staff. Nurses in Band 5 (i.e. those newly qualified or staff nurses) or Band 6 (i.e. those who are nursing specialists or senior nurses) were classed as junior, with Band 7 (i.e. those who are advanced nurses or nurse practitioners) or higher (e.g. Matrons) classed as seniors.

The following measures, for which binary outcomes were set following cut-off scores to indicate a case, were used; the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) with a score of >9 indicating probable moderate depression and >19 probable severe depression17; the 6-item PTSD checklist (PCL-6) with a score of >17 indicating the presence of probable PTSD18; AUDIT-C with a score of >7 indicating problem drinking19; the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale with a score >9 indicating a probable moderate anxiety disorder and >15 indicating probable severe anxiety disorder.20 The primary variable was defined, any mental disorder (AMD), which referred to those meeting the threshold criteria for at least one of the following probable mental disorders: moderate or severe anxiety, moderate or severe depression, problem drinking, or PTSD.

The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) was added to the survey during the surge, therefore data are only available for the timepoints during and after the surge. The scale is based on how much an individual's ability to carry out day-to-day tasks is impacted by an identified problem in their lives (e.g. ‘Because of the way I feel my ability to work is impaired’), and consists of five items answered on an 8-point Likert scale. A score of >20 indicated severe psychopathology-related functional impairment and a score of >10 indicated moderate functional impairment.14

Statistics

Using SPSS V27, descriptive statistics were plotted using counts and percentages for all mental health outcomes across the entire sample. The various measures of psychological distress were highly correlated, so one multivariable logistic regression was carried out using AMD, with demographic (i.e. gender, age) and professional variables (i.e. role, seniority) as predictors. A second multivariable logistic regression was carried out for the WSAS, with all probable mental health disorders, demographic, and professional variables entered as predictors. Because of the small sample size of other healthcare professionals, only doctors and nurses were included in the logistic regressions. Comparator groups were chosen based on expected impact (e.g. junior staff would be impacted more than senior staff, so senior staff became the reference category). To counter sample size issues and to ensure an adequately sized comparator group, senior nurses were compared with all others (junior nurses and all doctors), and senior doctors were compared with all others (junior doctors and all nurses), as we expected that the effect of seniority might be different across the professions. AMD and the WSAS were visually compared across timepoints using forest plots with odds ratios and confidence intervals shown. Inferential statistics comparing across waves were not possible because of a lack of independence of observations: as the survey was completed anonymously, we could not match responses in different waves that may have been from the same individuals.

Results

Demographics

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the sample used within the current study. Across all three timepoints, most respondents were female, and the modal age group was 30–44 yr old. Nurses comprised >50% of the sample at all timepoints; they were mainly junior (Band 6 or below) and were regular ICU, rather than redeployed, staff. Doctors constituted ∼30% of the sample; the majority were anaesthetists and of a senior level (i.e. Senior Associate Specialist or Consultant).

Table 1.

ICU participant characteristics.

| Variables | Before the surge (n=809) |

During the surge (n=2792) |

After the surge (n=2479) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 266 (32.9) | 719 (25.8) | 667 (26.9) |

| Female | 536 (66.3) | 2053 (73.5) | 1790 (72.2) |

| Othera | 7 (0.9) | 20 (0.7) | 22 (0.9) |

| Age (yr) | |||

| 16–29 | 141 (17.4) | 550 (19.7) | 426 (17.2) |

| 30–44 | 374 (46.2) | 1320 (47.3) | 1216 (49.1) |

| 45–56 | 268 (33.1) | 849 (30.4) | 756 (30.5) |

| 60+ | 26 (3.2) | 73 (2.6) | 81 (3.3) |

| Role | |||

| Doctor | 258 (31.9) | 791 (28.3) | 649 (26.2) |

| Type | |||

| Anaesthesia | 157 (60.9) | 401 (50.7) | 322 (49.6) |

| ICU | 89 (34.5) | 317 (40.1) | 280 (43.1) |

| Other | 12 (4.7) | 73 (9.2) | 47 (7.2) |

| Grade | |||

| Juniorb | 93 (36.0) | 300 (37.9) | 197 (30.4) |

| Seniorc | 165 (64.0) | 491 (62.1) | 452 (69.6) |

| Nurse | 428 (52.9) | 1615 (57.8) | 1455 (58.7) |

| Type | |||

| ICU | 351 (82) | 1334 (82.6) | 1260 (86.6) |

| Other | 16 (3.7) | 171 (10.6) | 115 (7.9) |

| Theatres | 61 (14.3) | 110 (6.8) | 80 (5.5) |

| Grade | |||

| Juniord | 329 (76.9) | 1264 (78.3) | 1113 (76.5) |

| Seniore | 99 (23.1) | 351 (21.7) | 342 (23.5) |

| Otherf | 123 (15.2) | 386 (13.8) | 375 (15.1) |

Indicates both those who chose to not disclose their gender, and those who selected ‘other’.

Refers to those who chose the following grading categories: FY 1–2, ST 3–4, ST 5–6, ST 6–7.

Refers to those who chose the following grading categories: consultant or senior associate specialist.

Refers to those who chose the following grading categories: Band 5 or Band 6.

Refers to those who chose the following grading categories Band 7, Band 8, or Band 9.

Encompasses the following job roles: healthcare assistant, occupational therapist, operating department practitioner, pharmacist, physiotherapist, and ‘other'.

Mental health measures

Prevalence

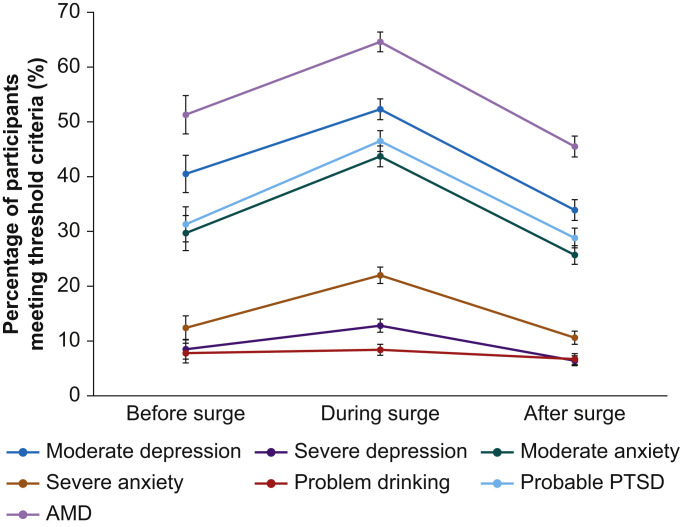

Figure 2 shows the percentage of ICU staff meeting the threshold criteria for all tested mental health measures. A clear pattern was observed across the timepoints. The prevalence of all tested mental disorders increased between before and during the surge (e.g. AMD 51.3% [47.8–54.8%] vs 64.6% [62.8–66.4%]), and then decreased after the surge (e.g. AMD 45.5% [43.6–47.5%]).

Fig 2.

Percentage prevalence and confidence intervals of participants meeting the threshold criteria for depression, anxiety, PTSD, and problem drinking across the COVID-19 2020/2021 winter surge. AMD, any mental disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder. Note. Before, after, and during samples are independent. The joining lines act as a visual aid. Before surge represents November 19, 2020 to December 17, 2020; during the surge represents January 26, 2021 to February 17, 2021; and after the surge represents April 14, 2021 to May 24, 2021.

Probable moderate depression was the most common across all timepoints (before: 40.5% [37.1–44.0%]; during: 52.3% [50.4–54.2%]; after: 33.9% [32.0–35.8%]), followed by probable PTSD (before: 31.3% [28.1–34.6%]; during: 46.5% [44.6–48.4%]; after: 28.8% [27.0–30.6%]), and moderate anxiety (before: 29.7% [26.5–33.0%]; during: 43.7% [41.8–45.5%]; after: 25.7% [24.0–27.5%]).

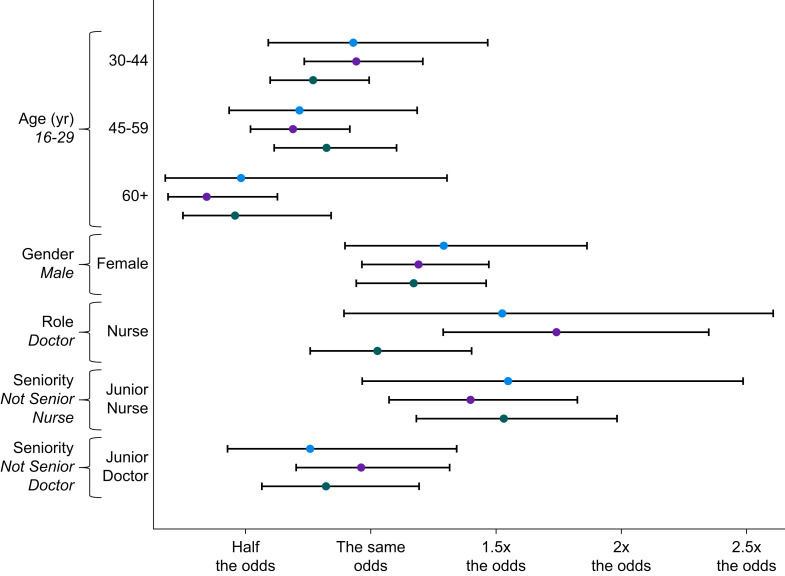

Adjusted outcomes

A multivariable logistic regression was performed to ascertain the association of age, gender, job role, and seniority with the likelihood that participants experienced AMD at each of the three timepoints. Results were relatively consistent across time. Figure 3 displays a forest plot of effect size and confidence intervals to allow visual comparison across timepoints. Older staff (30+ yr old) showed lower rates of AMD at all timepoints, with this result being statistically significant for some age groups during and after the surge. Nurses were more likely than doctors to have experienced AMD, although this was only statistically significant during the surge. Junior nurses were more likely than senior nurses or any doctors to have experienced AMD and this was significant during and after the surge. There were no statistically significant differences by gender or doctor seniority at any timepoint.

Fig 3.

Forest plot displaying confidence internals and effect sizes for each variable's effect on AMD over each timepoint. AMD, any mental disorder. Blue markers indicate before the surge, black markers indicate during the surge, and green markers indicate after the surge. Reference group italicised under each variable. Analysis was only carried out for doctors and nurses, senior nurses were compared with all others (junior nurses and all doctors); senior doctors were compared with all others (junior doctors and all nurses). Blue dots represent data from before the surge, black dots represent data from during the surge, and green dots represent data from after the surge.

Functional impairment (WSAS)

Prevalence

Functional impairment was more prevalent during the surge in comparison to after. During the surge, 69.1% (67.4–70.8%) of participants met the threshold criteria for functional impairment (consisting of 27.9% moderate and 41.2% severe). After the surge, 52.8% (50.8–54.7%) of participants met the threshold criteria for functional impairment (consisting of 27.3% moderate and 25.5% severe).

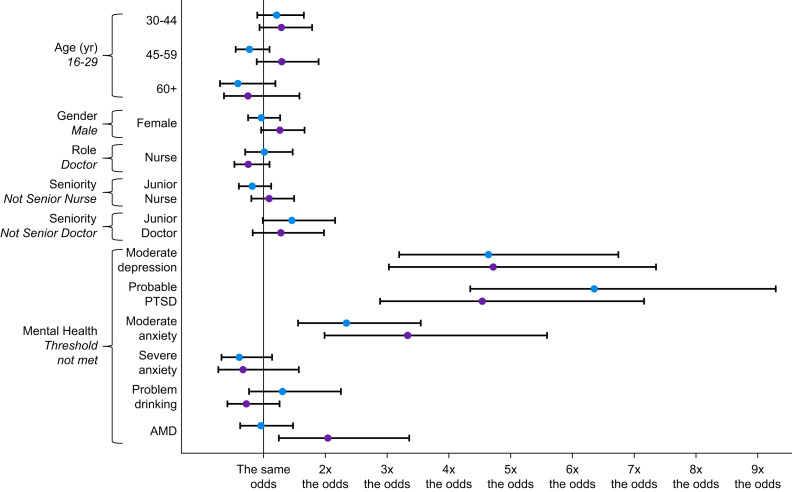

Adjusted outcomes

A multivariable logistic regression was performed to ascertain the association of age, gender, job role, seniority, and all mental health outcomes, with the likelihood that participants met the threshold criteria for functional impairment at both timepoints. Figure 4 displays a forest plot of effect size and confidence intervals to allow visual comparison across timepoints. Across both timepoints (during and after the surge), those with probable moderate depression (during odds ratio [OR]=4.7 [3.2–6.8], after OR=4.7 [3.0–7.4]), probable moderate anxiety (during OR=2.4 [1.6–3.6], after OR=3.3 [2.0–5.6]), and probable PTSD (during OR=6.4 [4.4–9.3], after OR=4.6 [2.9–7.2]) were all more likely to experience functional impairment in comparison to those without. There was no statistically significant relationship with problem drinking. While functional impairment was more prevalent overall during the surge, there was little difference in the likelihood of functional impairment between those with and without AMD (OR=0.95 [0.6–1.5]). After the surge, those respondents with AMD were twice as likely as those without to experience functional impairment. Controlling for mental health outcomes, there were no independent, statistically significant differences by age, gender, job role, or job seniority (for both doctors and nurses) at any timepoint.

Fig 4.

Forest plot displaying confidence intervals and effect sizes for each variable's effect on functional impairment over each timepoint. PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder. Reference group italicised under each variable. Analysis was only carried out for doctors and nurses; senior nurses were compared with all others (junior nurses and all doctors); senior doctors were compared with all others (junior doctors and all nurses). Blue dots represent data from during the surge, and black dots represent data from after the surge.

Discussion

During the peak of the COVID-19 surge in England, during the winter of 2020/2021, almost two-thirds of ICU staff included in this study met the threshold criteria for at least one of the surveyed probable mental health disorders. The risk of reporting AMD was significantly increased among young, junior nursing staff. This study also identified that more than half of all sampled ICU staff during and after this surge met the threshold criteria for functional impairment, with the likelihood of meeting this threshold being substantially increased by the presence of probable PTSD, anxiety, or depression.

This study demonstrates a relationship between seniority and mental ill-health among ICU nursing staff. This group may have been at increased risk for a number of reasons. Younger adults are more likely to report poor wellbeing21, 22, 23, 24, 25; furthermore studies of emergency services26 consistently find that lower grade/ranked staff are more likely to report poorer mental health. However, beyond their baseline risk factors, the extraordinary experience of junior nursing staff during this pandemic must also be taken into account. Junior nursing staff working in ICU during the pandemic were arguably exposed more consistently, and more directly, to the consequences of the mismatch between demand for critical care and the supply of human resource than staff in any other grade or role. It is likely that these factors contributed substantially to their increased risk of reporting poor mental health. Additionally, the prevalence of reported AMD in our study aligns with research indicating an increased rate of probable mental health disorders among frontline healthcare staff working during the COVID-19 pandemic.2 8 9 General population studies have shown comparable rates of probable, common mental health problems.27 25 However, beyond the common mental health disorders, our study includes a self-report measure of PTSD symptoms, the PCL-6. We identified that a sizeable fraction of respondents met or exceeded the threshold for probable PTSD at all three time points. Whilst there are no robust pre-pandemic data from ICU staff against which to compare this finding, we note these rates of probable PTSD are comparable to that seen in British military veterans deployed in a combat role during the war in Afghanistan.28 In our study, mental health status was associated with functional impairment, with those experiencing probable moderate depression, moderate anxiety, or probable PTSD, more likely to meet the threshold criteria for functional impairment, although we did not test the direction of this relationship. However, a prospective, observational, multicentre study of 31 ICUs reported that depression symptoms were an independent risk factor for medical errors, as were organisational factors such as training and workloads.29 This points to a potential association between poorer staff mental health, quality of care, and patient outcomes. The hypothesised associations between functional impairment and patient safety, which this research points towards, are highly concerning. Safety critical, vigilance tasks are a core feature in the delivery of critical care and thus staff working in ICU settings must function at a high level to ensure the safety and quality of patient care.

The conduct of a study in the context of ongoing, severe COVID-19 patient surge presented many challenges. We drew on the experience of other, clinical research teams operating in this environment, and adopted a pragmatic approach to study design, opting for an agile, scalable tool which allowed the capture of data which have clear limitations but nevertheless provide unique insight into mental health impacts on staff during a unique period of operational stress in the NHS. We identified the following principal limitations. Firstly, to ensure anonymity, no identifiable data were collected. As a result, it was not possible to either link cases to allow for longitudinal analysis at the level of individuals, or establish exclusivity between cases, rendering the data collected effectively cross-sectional. Secondly, we do not have data on the current demographic and professional characteristics of the ICU staff population during the COVID-19 crisis, so we do not know how representative the current study is. Thirdly, the recruitment method leaves open the possibility that those with more severe mental health symptoms might be more—or less—likely to participate, thus leading to potential bias. Fourthly, this study uses self-report measures which only provide an estimate of prevalence; interview-based studies would be required to establish the true prevalence of those who would meet diagnostic criteria. Lastly, we recognise that the reported confidence intervals within the regression models are relatively large, which suggests imprecision of observed results. However, this is expected as there were only a limited number of participants at each timepoint and the differences across timepoints remain consistent within the confidence intervals, meaning useful conclusions can still be drawn from the analysis. Future research should explore in further detail the casual relationship between mental health in ICU staff, patient care, and outcomes, coupled with efforts to more accurately define AMD prevalence through diagnostic interviews.

The causes of poor mental health and functional impairment in ICU staff during the pandemic are likely to be complex and multifactorial. However, our results reinforce that it is nevertheless important for healthcare managers to consider strategies to improve the psychological and functional health of their workforce. Delivering high-quality care requires functional staff and we suggest that wellbeing initiatives should be seen through the prism of improving patient safety, experience, and outcomes. In addition to ensuring psychologically healthy workplaces, managers should also take account of the need to develop resources and strategies such that individuals reporting high levels of distress can be rested or temporarily rotated away from higher intensity clinical roles. However, positively our results suggest that we should expect staff's mental health to improve if workload intensity decreases. However, there is, correspondingly, a risk of sustained impairment if demand for healthcare in this setting continues to outstrip capacity. Taken together, these findings provide a case for the establishment of a coherent and comprehensive recovery strategy, which appropriately matches demand for healthcare with NHS capacity and human resource, with the goal of protecting staff so that they in turn can continue to deliver safe, high-quality patient care. It is essential that staff are properly supported by employers who must recognise the association between mental health status and the ability of staff to safely carry out their caring duties.

Collaborators

Abhijoy Chakladar, Amy Scott, Anna Dennis, Caroline Dean, Catherine Snelson, Chris Langrish, Clare Dollery, Debbie Ford, Debbie Van Der Velden, Devaraja Acharya, Dominique Melville, Edward Cetti, Elaine Manderson, Fiona Kelly, Ganesh Suntharalingam, George Collins, Giulia Sartori, Hazem Rizk, Isatu Kargbo, Islam Saleh Abdo, James Holding, James Nicholson, Jennifer Ricketts, Jonathan Hulme, John-Paul Lomas, Judith Highgate, Katie Goodyer, Lawrence Wilson, Lindsay Ayres, Luis Colorado, Mark Paul, Nadine Weeks, Natasha Dykes, Nazril Nordin, Nitin Arora, Neil Allan, Neil Herbert, Nick Sherwood, Paul Dean, Paula Clements, Peter Bamford, Peter Hampshire, Raj Saha, Rebecca Gray, Rebecca O'Dwyer, Richard Breeze, Roopa McCrossan, Rosie Holmes, Samuel Graham, Sandra Barrington, Sarah Cooper, Stephane Ledot, Tristan McGeorge, Upeka Ranasinghe, Vivian Sathianathan

Author contributions

Performed data analysis, drafted the manuscript, constructed all tables, designed all figures and prepared the manuscript for submission: CEH.

Study coordinator, developed protocol: JM.

Supported data analysis, contributed to article revisions: JM, CS, TC.

Contributed to protocol: CS, JKB.

Contributed to write-up and article revisions: JKB.

Provided feedback on protocol and article revisions: DW.

Supported and guided data analysis, commented on multiple versions of the draft manuscript: HWWP.

Designed the electronic survey tools: TC.

Assisted with recruitment and data collection, contributed to study design and article revisions: MT, KK, SES.

Initiated the concept and formulated the initial design of the study and was a senior advisor to the project: KF.

Led study design, study deployment and study team, contributed to serial article revisions: NG.

Commented on earlier versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final version of the manuscript: all authors.

Funding

The National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emergency Preparedness and Response, a partnership between Public Health England, King's College London and the University of East Anglia. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, Public Health England, the UK Health Security Agency, or the Department of Health and Social Care (NIHR20008900).

Data sharing

The data used within this study are not publicly available.

Declarations of interest

NG runs a consultancy which provides the NHS with active listening and peer support training. KF works at University College London Hospitals as a consultant anaesthetist, holds an academic chair at University College London, and is seconded to NHS England as an advisor. HWWP has received funding from Public Health England and from NHS England. HWWP has a PhD student who works at and has fees paid by AstraZeneca. KK works for the Care Quality Commission.

Handling editor: Rupert Pearse

Footnotes

This article is accompanied by an editorial: Silver linings: will the COVID-19 pandemic instigate long overdue mental health support services for healthcare workers? by Stephens et al., Br J Anaesth 2022:128:912–914, doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.03.012

References

- 1.Aknin L., De Neve J.-E., Dunn E., et al. 2021. A review and response to the early mental health and neurological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson W., Raj J.P., Rao S., et al. Prevalence and predictors of stress, anxiety, and depression among healthcare workers managing COVID-19 pandemic in India: a nationwide observational study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42:353–358. doi: 10.1177/0253717620933992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Humadi S., Bronson B., Muhlrad S., et al. Depression, suicidal thoughts, and burnout among physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey-based cross-sectional study. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;45:557–565. doi: 10.1007/s40596-021-01490-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Kock J.H., Latham H.A., Leslie S.J., et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10070-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahebi A., Nejati-Zarnaqi B., Moayedi S., Yousefi K., Torres M., Golitaleb M. The prevalence of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;107:110247. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wanigasooriya K., Palimar P., Naumann D.N., et al. Mental health symptoms in a cohort of hospital healthcare workers following the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. BJPsych Open. 2021;7:e24. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto T., Uchiumi C., Suzuki N., Yoshimoto J., Murillo-Rodriguez E. The psychological impact of ‘mild lockdown’in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide survey under a declared state of emergency. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9382. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenberg N., Weston D., Hall C., et al. Mental health of staff working in intensive care during COVID-19. Occup Med (Lond) 2021;71:62–67. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg N., Docherty M., Gnanapragasam S., Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts T., Daniels J., Hulme W., et al. COVID-19 emergency response assessment study: a prospective longitudinal survey of frontline doctors in the UK and Ireland: study protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salyers M.P., Bonfils K.A., Luther L., et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:475–482. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tawfik D.S., Scheid A., Profit J., et al. Evidence relating health care provider burnout and quality of care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:555–567. doi: 10.7326/M19-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolev T., Zubedat S., Brand Z., et al. Physiological parameters of mental health predict the emergence of post-traumatic stress symptoms in physicians treating COVID-19 patients. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mundt J.C., Marks I.M., Shear M.K., Greist J.M. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–464. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fear N.T., Seddon R., Jones N., Greenberg N., Wessely S.J. Does anonymity increase the reporting of mental health symptoms? BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson A.L.G., Hoge C.W., McGurk D., et al. Application of a new method for linking anonymous survey data in a population of soldiers returning from Iraq. Ann. Epidemiol. 2010;20:931–938. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang A.J., Stein M.B. An abbreviated PTSD checklist for use as a screening instrument in primary care. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bush K., Kivlahan D.R., McDonell M.B., et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus and depression in adults, Great Britain: January to March 2021. 2021.

- 22.Daly M., Robinson E. Longitudinal changes in psychological distress in the UK from 2019 to September 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from a large nationally representative study. Psychiatry Res. 2021;300:113920. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickerson J., Kelly B., Lockyer B., et al. When will this end? Will it end?' The impact of the March-June 2020 UK COVID-19 lockdown response on mental health: a longitudinal survey of mothers in the Born in Bradford study. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moitra M., Rahman M., Collins P.Y., et al. Mental health consequences for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review to draw lessons for LMICs. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:22. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.602614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fancourt D., Bu F., Mak H., Paul E., Steptoe A. University College London. Health DoBS; London: 2021. Covid-19 Social Study Results Release 32. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fear N.T., Rubin G.J., Hatch S., et al. Job strain, rank, and mental health in the UK Armed Forces. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2009;15:291–298. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2009.15.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith L.E., Amlôt R., Fear N.T., Michie S., Rubin J., Potts H. February 1). Psychological wellbeing in the English population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a series of cross-sectional surveys. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Stevelink S.A., Jones M., Hull L., et al. Mental health outcomes at the end of the British involvement in the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: a cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:690–697. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrouste-Orgeas M., Perrin M., Soufir L., et al. The Iatroref study: medical errors are associated with symptoms of depression in ICU staff but not burnout or safety culture. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(2):273–284. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3601-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]