Abstract

Objective:

Pediatric health systems are increasingly screening caregivers for unmet social needs. However, it remains unclear how best to connect families with unmet needs to available and appropriate community resources. We aimed to explore caregivers’ perceived barriers to and facilitators of community resource connection.

Methods:

We conducted semi-structured interviews with caregivers of pediatric patients admitted to one inpatient unit of an academic quaternary care children’s hospital. All caregivers who screened positive for one or more unmet social needs on a tablet-based screener were invited to participate in an interview. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded by two independent coders using content analysis, resolving discrepancies by consensus. Interviews continued until thematic saturation was achieved.

Results:

We interviewed 28 of 31 eligible caregivers. Four primary themes emerged. First, caregivers of children with complex chronic conditions felt that competing priorities related to their children’s medical care often made it more challenging to establish connection with resources. Second, caregivers cited burdensome application and enrollment processes as a barrier to resource connection. Third, caregivers expressed a preference for geographically tailored, web-based resources, rather than paper resources. Lastly, caregivers expressed a desire for ongoing longitudinal support in establishing and maintaining connections with community resources after their child’s hospital discharge.

Conclusion:

Pediatric caregivers with unmet social needs reported competing priorities and burdensome application processes as barriers to resource connection. Electronic resources can help caregivers identify locally available services, but longitudinal supports may also be needed to ensure caregivers can establish and maintain linkages with these services.

Keywords: Social determinants of health, Unmet social needs, Health equity, Qualitative research

Introduction

Health-related social needs, which are defined as adverse social conditions associated with poor health outcomes, can negatively impact children’s health and development.1–5 The American Academy of Pediatrics therefore recommends that pediatricians routinely screen patients and caregivers for unmet social needs.6 In addition, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are currently evaluating strategies for identifying and addressing patients’ social needs, including food insecurity, assistance with transportation, assistance with utilities, and mental health support, through the Accountable Health Communities Model.7 Several state Medicaid agencies have also implemented programs and policies incentivizing providers to screen for and address social needs.8

As health systems across the country develop and implement social needs screening programs in response to these guidelines and incentives, it will be critically important to ensure that screening is used as the starting point for a discussion regarding families’ priorities and preferences, rather than an automatic indication for referral, and that families who express a desire for support related to their social needs can be linked to available and appropriate resources.9 Screening for unmet social needs without a feasible means for prioritizing caregiver preferences, providing relevant resource referrals, and supporting caregiver follow through can lead to frustration among both providers and patients and erode families’ trust in the healthcare system.10

However, it remains unclear how health systems can most effectively use the results of social needs screening to link families to community resources that will address caregiver-prioritized unmet social needs. Several previous studies of social needs screening followed by telephone-based or web-based resource referrals have shown low rates of successful linkage to resources, ranging from less than 10% to 33%.11–14 These low rates of linkage may be due to both inadequate support from health systems and caregivers’ mistrust of social service programs, stemming from previous negative interactions with the child protection or criminal justice systems.15 As screening becomes more widespread, it will be crucial for health systems to understand how to successfully link families with resources in a manner that is consistent with their preferences and builds trust in health and social service systems.

Prior qualitative studies of social needs screening interventions have focused predominantly on caregiver perspectives regarding the acceptability of screening and on their perceptions of verbal and tablet-based screening.16–18 These studies have found that the majority of caregivers believe social needs screening is acceptable across clinical settings and that many caregivers prefer the confidentiality of tablet-based screening to verbal screening. However, few studies have specifically explored caregivers’ perceived barriers to connection with community resources and elicited their preferences for health-system based assistance.

We therefore designed a qualitative study of caregivers with one or more unmet social needs to explore: (1) perceived barriers to connecting with resources targeted to their needs, and (2) perceived facilitators of connection with resources, and (3) preferences for how health systems could most effectively support this process. This study was conducted before and during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, and therefore, as an additional exploratory aim, we sought to identify additional barriers to resource connection that caregivers may have faced during the pandemic.

Methods

Overview

This qualitative study was nested within a quality improvement project in which our team implemented (1) tablet-based social needs screening and (2) use of an electronic resource map website to support referrals, on an academic quaternary care children’s hospital inpatient unit.19 Patients on this unit are admitted to either a complex care or general pediatrics service and are cared for by a single care team, including pediatric resident physicians, attending physicians, nurses, a social worker, a case manager, and a care team assistant (CTA). CTAs are trained team members who assist providers with non-clinical tasks including engaging with family members and bedside nurses to support their participation in family-centered rounding.20

The tablet-based screener was administered by the unit CTA, who approached caregivers, introduced the opt out social needs screening questionnaire, and then provided caregivers with support in completing the questionnaire, if requested. The questionnaire (Appendix 1) included validated screening questions across five domains: food insecurity, difficulty with transportation, difficulty paying for utilities, depressed mood, and intimate partner violence. These domains were selected by our multidisciplinary team of social workers, nurses, and physicians because they were felt to be the most amenable to intervention and provision of local resource support. Screening questions were adapted from the Accountable Health Communities screening tool and the CDC toolkit for intimate partner violence prevention and included the validated Hunger Vital Sign to screen for food insecurity and the PHQ-2 to screen for caregiver mental health needs.21–26

After caregivers completed the questionnaire, the CTA showed them how to use the electronic resource map, a searchable web-based database of community resources, to find programs and services in their area. Caregivers were able to use the resource map either on their own mobile device or on hospital-provided tablets in each patient room. Caregivers could text or email resources to themselves, and all caregivers received information about the website, which is publicly available, as part of their discharge paperwork. Caregivers who screened positive for one or more social needs also received a social work evaluation prior to discharge.

The resource map used in this study was created by our study team in partnership with Aunt Bertha, a public benefit corporation focused on helping individuals connect with social services.27 Hospital social workers partnered with Aunt Bertha’s team to identify and vet local and regional resources and optimize the order of resources listed within its resource search engine.

Study Participants and Recruitment

Caregivers were eligible for inclusion in this qualitative study if they (1) screened positive for one or more social needs, (2) were 18 years of age or older, and (3) were able to understand and speak fluent English. Our sampling strategy, guided by our conceptual framework, established a goal of sampling caregivers from a range of circumstances. To this end, purposive sampling was used to recruit caregivers who: (1) endorsed each of the five included social needs, (2) had only one social need, (3) had multiple social needs, (4) had children admitted to the general pediatrics service, and (5) had children admitted to the complex care service.

After completing the screener, eligible caregivers were asked whether they would be willing to participate in a semi-structured interview either during or after their admission. Caregivers who expressed willingness to participate were contacted by a study team member who explained the study purpose and procedures, reviewed eligibility criteria, and confirmed their interest in participating. Caregivers received a $25 gift card for participation. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia institutional review board deemed this study non-human subjects research.

Data Collection

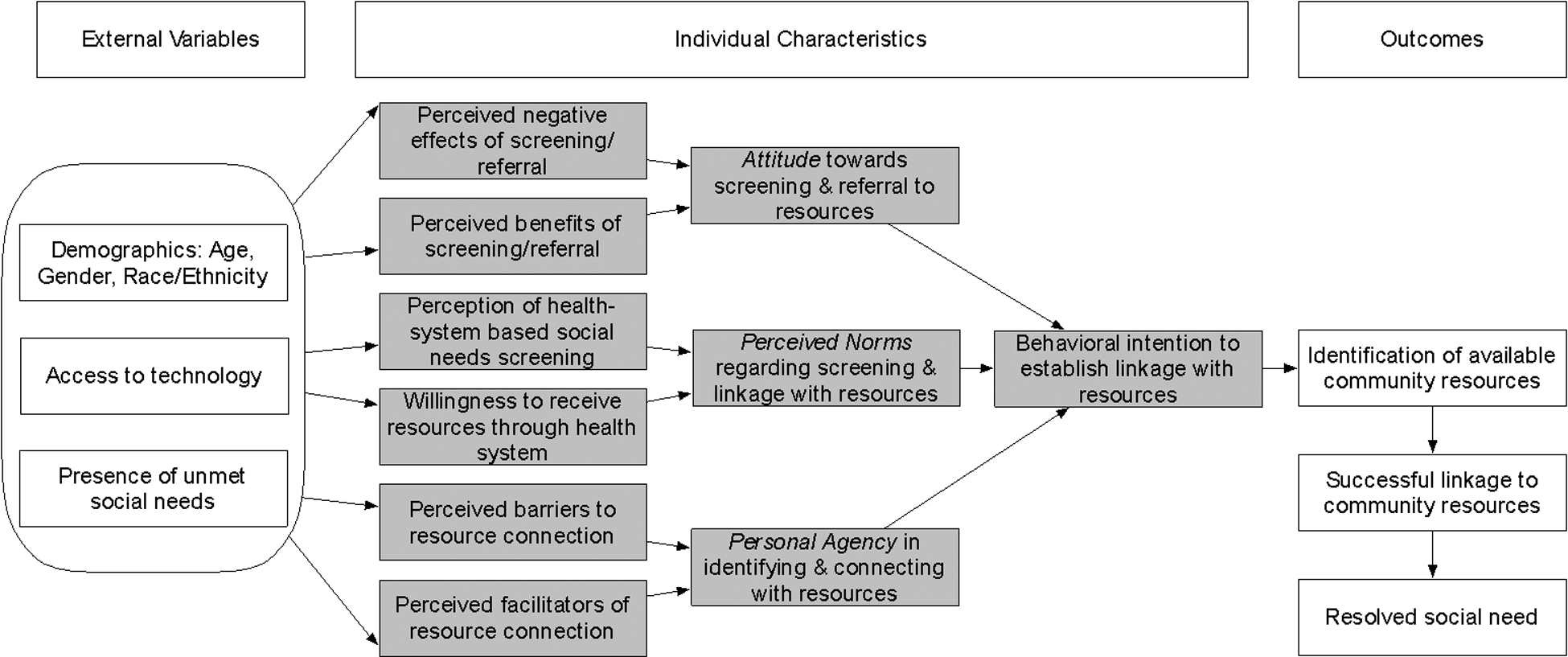

We first developed a conceptual model for linkage to community resources (Figure A1) adapted from the Integrated Behavioral Model.28,29 We then created a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 2) with prompts mapped onto the major drivers of resource linkage included in our conceptual model. The guide was specifically designed to first assess caregiver perspectives on screening and then explore perceived barriers to and facilitators of linkage with resources, as well as their preferences for assistance. We used open-ended questions to encourage caregivers to share barriers and facilitators related to not only the five social needs domains included in our screener, but also any other social needs they had experienced. The guide was pilot tested and refined based on feedback from three caregivers who met inclusion criteria.

With verbal informed consent, we conducted 14 semi-structured interviews in February-March 2020 and 14 semi-structured interviews in July-October 2020. For the second set of interviews, we modified our interview guide to include two additional questions exploring barriers to accessing resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A researcher trained in qualitative techniques conducted all interviews either in-person during a child’s admission, or over the phone (to minimize in-person exposures during the pandemic) within a week of hospital discharge. At the time of the interview, caregivers were asked to report their age, race, ethnicity, highest level of education completed, and receipt of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) benefits. Information about children’s age, insurance status, and presence of complex chronic conditions (CCCs) was abstracted from the electronic medical record. Demographic information was recorded and stored securely using a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database.

Data Analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, deidentified, and entered into QSR NVivo12 software for data analysis. We used content analysis to code the interviews inductively. A unique coding scheme and dictionary were developed based on the first five interviews, and codes were evaluated and revised after each coding session, consistent with a constant comparative method. Two members of the study team (A.V. and O.D.) coded each interview transcript independently. Through an iterative process, we reviewed codes, identified emerging themes, and resolved discrepancies through consensus. Interviews were continued until thematic saturation was reached.

Results

We approached 31 caregivers who screened positive for one or more social needs from February-March 2020 and July-October 2020. Two caregivers declined participation, and one caregiver initially consented to participate but could not be reached by phone following hospital discharge. Twenty-eight interviews were completed. Demographic characteristics of participating caregivers and their children are presented in Table 1. Most caregivers were mothers, with a mean age of 33 years. Forty-three percent identified as Black or African American, and 11% as Hispanic or Latino. More than half reported two or more unmet social needs. The most frequent social needs were depressed mood, food insecurity, and need for assistance with utilities. The majority of participating caregivers had children who were Medicaid-insured (82%) and had one or more CCCs (68%). Inter-rater reliability analysis of coded transcripts produced an average kappa statistic of 0.87.

Table 1.

Caregiver and Child Demographic Characteristics and Unmet Social Needs

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Caregiver Demographic Characteristics | |

| Age, mean (range) | 33 years (24–54 years) |

| Relationship to Child | |

| Mother | 25 (89%) |

| Father | 2 (7%) |

| Grandmother | 1 (4%) |

| Race | |

| White | 12 (43%) |

| Black or African American | 12 (43%) |

| Other | 4 (14%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (11%) |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 25 (89%) |

| Highest Level of Education Completed | |

| High School or GED | 10 (28%) |

| Some College | 7 (36%) |

| Graduated from College | 11 (36%) |

| Housing Status | |

| Unstable and/or Temporary Housing | 2 (7%) |

| Stable and/or Permanent Housing | 26 (93%) |

| Use of Government Benefits | |

| SNAP | 7 (25%) |

| WIC | 10 (36%) |

| Number of Unmet Social Needs | |

| 1 | 12 (43%) |

| 2 | 14 (50%) |

| 3 | 2 (14%) |

| Unmet Social Needs | |

| Depressed mood | 19 (68%) |

| Food insecurity | 15 (54%) |

| Assistance with utilities | 9 (32%) |

| Assistance with transportation | 4 (14%) |

| Intimate partner violence | 1 (4%) |

| Child Demographic Characteristics | |

| Age, mean (range) | 1.8 years, (1 month-12 years) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 14 (50%) |

| Female | 14 (50%) |

| Medical Complexity | |

| ≥ 1 Complex Chronic Conditions | 19 (68%) |

| No Complex Chronic Conditions | 9 (32%) |

| Insurance | |

| Medicaid | 20 (71%) |

| Private Insurance and Secondary Medicaid | 3 (11%) |

| Private Insurance Alone | 5 (18%) |

Barriers to Resource Connection

We identified two primary themes related to barriers to resource connection (Table 2A). First, caregivers described competing priorities related to caring for a chronically ill or medically complex child as a significant barrier to both identifying available resources and connecting to these resources. One mother of a medically complex infant who screened positive for depressed mood described prioritizing her child’s needs over her own, saying, “I’m going to make sure that my baby has everything they need before I take care of myself…therapy for me, that’s not really what comes first.” Another caregiver described the stress of applying for benefits while caring for her child, saying, “You don’t want to do the applications, you don’t want to sit on the phone with someone for 45 minutes running down, ‘How many people live in your household? How much income do you have?’ when your brain is thinking, ‘Is my kid going to be okay?’”.

Table 2A.

Barriers to Resource Connection

| Theme | Representative Quotations |

|---|---|

| 1. Competing priorities related to caring for a medically complex child |

|

| 2. Difficulty enrolling in and utilizing government benefit programs |

|

Second, caregivers described challenges they faced in enrolling in and utilizing government benefit programs, like WIC, SNAP, and the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP). One mother who screened positive for difficulty with utilities said, “Right now, I’m applying for LIHEAP, and I have to get these letters saying that my other son doesn’t have any income, stupid things like that. That makes it hard, little things that prolong the process that shouldn’t. My son is three. They should know he doesn’t work.” Several food insecure caregivers described barriers associated with obtaining and redeeming WIC benefits, including long wait times in the WIC office, difficulty identifying WIC-eligible products in stores, and difficulty redeeming WIC paper vouchers. One mother said, “Sitting in the WIC office for hours is horrible. Just having to sit in the office with your baby, especially if they’re sick. But they’re giving formula to feed your baby, and I would do anything for that.”

Facilitators of Resource Connection

We identified two primary themes related to facilitators of resource connection (Table 2B). First, most caregivers expressed appreciation for electronic resources, rather than paper resources, and for resources specific to their own neighborhood and community. One mother said, “A brochure, I would lose as soon as you hand it to me, I’d put it down. But you give me this website, and I can go on it whenever I want.” While the majority of caregivers identified electronic resources as a facilitator of resource connection, one caregiver noted that offering the option of paper resources might be beneficial for families with limited internet access, saying, “Some people don’t have the means to get the internet, and especially in the time that we’re in…So for them, paper might be better.”

Table 2B.

Facilitators of Resource Connection

| Theme | Representative Quotations |

|---|---|

| 1. Appreciation for electronic resources and information about locally available programs |

|

| 2. Desire for longitudinal support in establishing and maintaining connection with resources |

|

Many caregivers living farther from the hospital expressed appreciation for an electronic resource map that included information about programs and services closer to their home. One mother noted, “It’s nice putting in our zip code and having just our services. Because we’re from [another state], and a lot of stuff near [the hospital] is [state specific]. So it’s nice to be able to go into our state, our area, and see what’s out there.” Another mother described feeling initial apprehension about the screening questionnaire followed by relief when she was provided the resource map customized to her location, saying, “The [screening] questionnaire made me interested as to, once the questions are answered and the results are checked, then what? What will be the solution? You can tell someone something, but that doesn’t mean that something will be done about it. And it’s almost pointless to ask if you don’t have information to give… at the end of it, it was good, because you got to the website and you actually got to see what was available in your area. So I liked that.”

Second, when asked how the health system could help facilitate resource connection, several caregivers expressed a desire for longitudinal support and care coordination to help them establish connections with community resources and enroll in government benefit programs. One caregiver said, “It would be good if you had somebody you could call from the hospital…because sometimes you get so stressed that you can’t think of what to do. So it would be good to have someone who you could call and say, “Hey, I ran out of food, can you point me in the right direction?” Another caregiver said, “When I got hooked up with WIC, it was at my OB/GYN, and they actually helped do the application for me…That was the best thing I could have asked for.”

Novel Barriers to Resource Connection During the COVID-19 Pandemic

We identified three novel barriers to resource connection during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 3). First, caregivers described having difficulty accessing food due to increased food costs and increased stress associated with grocery shopping. Second, caregivers described worsening administrative burdens and delays associated with accessing government benefit programs, particularly WIC, SNAP, and unemployment insurance, during the pandemic. Lastly, caregivers of medically complex children described increased stress associated with losing access to in-home and school-based supports for their children.

Table 3.

Novel Barriers to Resource Connection During the COVID-19 Pandemic

| Theme | Representative Quotations |

|---|---|

| 1. Increased cost of food and increased stress associated with grocery shopping |

|

| 2. Administrative delays associated with accessing government programs |

|

| 3. Loss of in-home and school-based services for children with medical complexity |

|

Discussion

In this qualitative study, we identified barriers to and facilitators of community resource connection for pediatric caregivers with unmet social needs. Four primary themes emerged from the interviews: (1) caregivers described competing priorities related to caring for a chronically ill child as a barrier to resource connection; (2) caregivers described burdensome application and enrollment processes as a barrier to applying for and utilizing government benefit programs; (3) caregivers expressed appreciation for electronic resources with information about locally available programs and services; and (4) caregivers expressed a desire for longitudinal support in establishing and maintaining connections with government benefit programs and community resources. Given the paucity of existing research focused on determinants of resource connection among pediatric caregivers with unmet social needs, our findings have several important implications for pediatric providers and health systems as they work to implement successful social needs screening and referral programs.

First, caregivers of medically complex children may be a particularly important population to engage with when implementing social needs screening and resource navigation programs. Implementing standardized social needs screening and referral programs in the neonatal intensive care unit represents one promising way to reach a subset of this patient population.30,31 Screening and referral programs implemented in the emergency department and in the inpatient setting may also help health systems identify and address social needs for caregivers of chronically ill children and caregivers who face barriers to accessing routine preventive care.32,33 In addition, interventions specifically designed to provide longitudinal support around unmet social needs and facilitate benefits enrollment and connection to community resources should be incorporated into health system-level and state-level care management programs for children with medical complexity.

Second, offering searchable electronic information tailored to families’ local context may help support resource connection. As caregivers in our study noted, a resource map website allows caregivers to dynamically search for and identify local resources tailored to their needs, including new needs that may arise after they are discharged. Our findings are in line with previous survey studies showing that electronic resource referral platforms improved adult patients’ knowledge about available community resources.34,35 Using electronic resource maps to support referrals may be particularly beneficial for tertiary and quaternary care hospitals that provide care for children and families from a large geographic catchment area. However, as noted by one of our study participants, caregivers with barriers to accessing the internet should also be offered the option of written resources.

Third, in addition to providing information about resources, pediatric health systems should consider offering longitudinal support focused on helping caregivers navigate application and enrollment processes for government benefit programs and community resources. Prior studies suggest that administrative burdens, like the burdensome enrollment paperwork and documentation processes that caregivers in our study described when trying to access programs like LIHEAP, WIC, and SNAP, can limit enrollment in and utilization of these government benefit programs.36–38 To help caregivers navigate these burdens, health systems could employ social workers, case managers, or trained community health workers (CHWs), who may have lived experience with accessing and utilizing these programs.

Securing sustainable funding and support for this multidisciplinary workforce may be challenging, but such funding represents a crucial investment, since clinics and health systems employing social workers and CHWs may be both more likely to screen for unmet social needs and better equipped to address them.39 State Medicaid agencies that implement incentives or mandates for social needs screening should consider providing concurrent support for social needs-focused interventions, including funding for health-system based social workers and CHWs, to ensure that patients’ and families’ unmet needs can be adequately addressed. Health systems could also partner with community-based organizations focused on increasing access to resources. Existing evidence-based models for supporting caregivers’ linkage with resources, such as Help Me Grow, WE CARE, and FINDconnect, could be used as models for this work.40–42 Augmenting screening and referral programs with a reliable and consistent system of closed-loop follow-up designed to provide caregivers with ongoing support could help build families trust and improve the success rate of initial referrals.

Lastly, our findings highlight the particular importance of helping families identify and connect with resources in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous studies have shown an increase in the prevalence of social needs, particularly food insecurity, since the start of the pandemic and associated recession.43,44 Our results underscore the importance of not only identifying these needs, but also offering caregivers assistance with accessing food and enrolling in government benefit programs, as well as providing supports for families who may have previously relied on in-home or school-based services during prolonged school closures.

Our study has several limitations. We interviewed caregivers of hospitalized patients at one academic pediatric children’s hospital, and although we utilized a purposive sample of caregivers designed to elicit a broad range of caregiver experiences, the perspectives and opinions expressed in this qualitative study are not intended to be representative of the experiences of all caregivers or of caregivers in other settings. Of note, our study population included a high proportion of caregivers of children with one or more CCCs, whose caregivers may have unique experiences or high burdens of social need. Additionally, we provided families with both a vetted electronic resource map and a social work evaluation, which may not be feasible in less-resourced settings.

We excluded non-English speaking patients from this study because our tablet-based screener and resource map had not yet been adapted to languages other than English. Eliciting the perspectives of families with limited English proficiency in designing interventions to promote successful resource connection is an important next step, as these families may face unique challenges both in identifying available resources and in connecting to these resources.45 Additionally, there may have been selection bias among the caregivers who agreed to participate in interviews, although our high response rate reduces the potential for this bias.

Conclusions

In this qualitative study, pediatric caregivers with one or more unmet social needs reported competing priorities related to caring for a medically complex child and burdensome application processes as two significant barriers to resource connection. Electronic resource maps may represent a valuable tool for helping caregivers identify locally available services. Health systems should also consider implementing longitudinal support services designed to ensure caregivers can establish and maintain linkages with resources that meet their needs.

What’s New?

Pediatric caregivers with unmet social needs face multiple challenges in identifying and connecting to resources. Web-based resource referral platforms can help caregivers identify services, but longitudinal support may be critical to help caregivers establish and maintain connections to community resources.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the clinicians and support staff at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for their assistance in implementing and sustaining our inpatient social needs screening and referral project, particularly Arleen Juca, BS, Stuti Tank, BA, Leigh Wilson-Hall, MSW, and Kimberley St. Lawrence, MSW. Shimrit Keddem, PhD, MPH and Judy A. Shea, PhD provided very helpful qualitative analytic support for this study. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at CHOP. This work was funded by a pilot grant from the Leonard Davis Institute for Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Funding Source:

All phases of this study were supported by a Pilot Grant from the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania. This work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health award grant no. K23HL136842 to C.C.K. The sponsors of this work had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Figure A1. Conceptual Model.

The conceptual model used for this study was adapted from the Integrated Behavioral Model,28 which describes how an individual’s intent to perform a behavior can be governed by their attitude regarding the behavior, their perceived norms regarding the behavior, and their sense of personal agency. Interview prompts were mapped onto the drivers of linkage with resources included in this model.

Appendix 1. Screening Questionnaire

Note: Domain headings and references are included below but were not included in the patient-facing questionnaire.

We ask all families the questions in this survey, which helps us provide the best care possible to you and your child. If you choose to answer the questions, the answers will be reviewed by the care team so they can find the best ways to support you and your family. This questionnaire is voluntary, and you can choose to skip questions by clicking “Next Page” without answering the question.

Food Insecurity22

Some people have made the following statements about their food situation. Please answer whether the statements were OFTEN, SOMETIMES, or NEVER true for you and your household in the last 12 months.

-

1Within the past 12 months, you worried that your food would run out before you got money to buy more?

- Often true

- Sometimes true

- Never true

-

2Within the past 12 months, the food you bought just didn’t last and you didn’t have money to get more.

- Often true

- Sometimes true

- Never true

Transportation23

-

3In the past 12 months, has lack of reliable transportation kept you or your child from medical appointments?

- Yes

- No

Utilities24

-

4In the past 12 months has the electric, gas, oil, or water company threatened to shut off services in your home?

- Yes

- No

- Already shut off

Depressed Mood25

Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems:

-

5Little interest or pleasure in doing things?

- Not at all

- Several days

- More than half the days

- Nearly every day

-

6Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?

- Not at all

- Several days

- More than half the days

- Nearly every day

Intimate Partner Violence26

The following questions are about safety in your relationship. If there are safety concerns, a social worker will talk to you privately.

-

7Have you been hit, kicked, punched, or otherwise hurt by someone within the past year?

- Yes

- No

-

8Do you feel safe and comfortable in your current relationship(s)?

- Yes

- No

-

9Is there a partner from a previous relationship who is making you feel uncomfortable or unsafe now?

- Yes

- No

Appendix 2. Semi-Structured Interview Guide

Note: Questions 7 and 8, in blue below, were added to the interview guide for the second set of 14 interviews, conducted from July-October 2020.

Hello [caregiver name], it’s nice to meet you. My name is [name]. I am a researcher at [hospital], working with a team of doctors, nurses, and other staff to understand and address some of the real-life issues that can make life harder for families and their kids: things like not having enough food and having trouble paying bills or getting transportation to appointments.

As you might remember, we have started asking families about these issues when they come into the hospital and then working to connect them with programs and resources in their neighborhoods that can help. We are trying to make this process better and make sure it is working for families.

Over the next 15–20 minutes, I’d like to ask you some questions about the survey you answered on your phone and the website we gave you a link to afterwards, as well as about the overall process of understanding issues families are dealing with and how health care providers can best help with those issues. If it’s okay with you, I’d like to record our conversation so that our team can listen to it later and make sure we hear all of your thoughts. Your answers will be anonymous, meaning they won’t be tied to your name or your child’s name. Your answers won’t be shared with your child’s care team, or any agency, or have any impact on your child’s medical care. If you would rather not answer more questions, we can stop at any time.

When we’re done with the interview, you’ll get a $25 gift card sent to you by mail as a thanks for your time. Is it okay if we begin?

First, I’d like to ask about your experience answering the questions we sent to you by text/email.

-

1

What was it like for you to answer these questions?

Probe:- How would it feel different being asked these questions by a person, instead of on the iPad?

-

2

When you filled out the survey for us, you mentioned worrying about [category of positive screen.] How important is getting help with [category] for you right now?

Next, I have some more big picture questions, about how you think we can help link families with programs that address these real-life issues.

-

3

In general, what do you think about a website as a way to let families know about community resources?

Probe:- What if instead of a website, we gave you a printed brochure that listed resources? Do you think that would be better or worse? Why?

- What do you think are the best ways for you to get information about resources? For example, from friends and neighbors, from a hospital or clinic, from a religious or community organization?

One thing we’ve heard from families in the past is that giving them information about resources isn’t always enough to make sure that they can actually connect with these programs and services.

-

4

What do you think would be the best way for us to help families actually connect with programs that can support their needs (things like food, shelter and safety)?

-

5

What kind of ongoing help or support would you want in connecting to resources, after you leave the hospital?

We are also curious about what families think would be most helpful in order for their needs to be resolved.

-

6

Thinking back to a time when you needed help with [need], or with something else, what would have helped you most in that moment?

Probe:- When you’ve received resources to help with [need] in the past, what has made it easier or harder to get connected with these resources?

We are also trying to understand how the current coronavirus pandemic has affected families, in terms of their needs and in terms of their ability to get connected with resources.

-

7

How have your family’s needs changed in the past few months, during the coronavirus pandemic?

-

8

What has it been like for you to get connected with resources during the pandemic? How is this different from what it was like before?

-

9

What else would you like to tell us about we can connect families to resources to help kids stay healthy?

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Rose-Jacobs R, Black MM, Casey PH, et al. Household Food Insecurity: Associations With At-Risk Infant and Toddler Development. Pediatrics. 2007. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. 2015. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook JT, Frank DA. Food security, poverty, and human development in the United States. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morales ME, Berkowitz SA. The Relationship Between Food Insecurity, Dietary Patterns, and Obesity. Curr Nutr Rep. 2016;5(1):54–60. doi: 10.1007/s13668-016-0153-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandel M, Sheward R, De Cuba SE, et al. Unstable housing and caregiver and child health in renter families. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AAP Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and Child Health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160339–e20160339. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable health communities - Addressing social needs through medicare and medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1512532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alderwick H, Hood-Ronick CM, Gottlieb LM. Medicaid Investments To Address Social Needs In Oregon And California. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck AF, Klein MD. Moving from Social Risk Assessment and Identification to Intervention and Treatment. Acad Pediatr. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garg A, Boynton-Jarrett R, Dworkin PH. Avoiding the unintended consequences of screening for social determinants of health. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2016;316(8):813–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palakshappa D, Vasan A, Khan S, Seifu L, Feudtner C, Fiks AG. Clinicians’ perceptions of screening for food insecurity in suburban pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schickedanz A, Sharp A, Hu YR, et al. Impact of Social Needs Navigation on Utilization Among High Utilizers in a Large Integrated Health System: a Quasi-experimental Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05123-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullen D, Abel D, Attridge M, Fein JA. Exploring the Gap: Food Insecurity and Resource Engagement. Acad Pediatr. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindau ST, Makelarski JA, Abramsohn EM, et al. CommunityRx: A real-world controlled clinical trial of a scalable, low-intensity community resource referral intervention. Am J Public Health. 2019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brayne S Surveillance and System Avoidance: Criminal Justice Contact and Institutional Attachment. https://doi.org/101177/0003122414530398. 2014;79(3):367–391. doi: 10.1177/0003122414530398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palakshappa D, Doupnik S, Vasan A, et al. Suburban families’ experience with food insecurity screening in primary care practices. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colvin JD, Bettenhausen JL, Anderson-Carpenter KD, Collie-Akers V, Chung PJ. Caregiver Opinion of In-Hospital Screening for Unmet Social Needs by Pediatric Residents. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(2):161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cullen D, Attridge M, Fein JA. Food for Thought: A Qualitative Evaluation of Caregiver Preferences for Food Insecurity Screening and Resource Referral. Acad Pediatr. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortin K, Vasan A, Wilson-Hall CL, Brooks E, Rubin D, Scribano PV. Using Quality Improvement and Technology to Improve Social Supports for Hospitalized Children. Hosp Pediatr. September 2021. doi: 10.1542/HPEDS.2020-005800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takei R, Dalembert G, Ronan J, et al. Implementing Resident Team Assistant Programs at Academic Medical Centers: Lessons Learned. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(6):769–772. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-20-00173.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billioux A, Verlander K, Anthony S, Alley D. Standardized Screening for Health-Related Social Needs in Clinical Settings: The Accountable Health Communities Screening Tool. NAM Perspect. 2017;7(5). doi: 10.31478/201705b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Association of Community Health Centers I. PRAPARE Implementation and Action Toolkit. National Association of Community Health Centers, Inc., Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, Oregon Primary Care Association. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook JT, Frank DA, Casey PH, et al. A brief indicator of household energy security: Associations with food security, child health, and child development in US infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2008. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The patient health questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerberding JL, Falk H, Arias I, Hammond WR. Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence Victimization Assessment Instruments for Use in Healthcare Settings. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/ipvandsvscreening.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- 27.Aunt Bertha, the Social Care Network. https://company.auntbertha.com/. Accessed January 3, 2021.

- 28.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitudes and normative beliefs as factors influencing behavioral intentions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1972. doi: 10.1037/h0031930 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice.; 2015.

- 30.Parker MG, Garg A, McConnell MA. Addressing Childhood Poverty in Pediatric Clinical Settings: The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Is a Missed Opportunity. JAMA Pediatr. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker MG, Garg A, Brochier A, et al. Approaches to addressing social determinants of health in the NICU: a mixed methods study. J Perinatol. October 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41372-020-00867-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiori KP, Heller CG, Rehm CD, et al. Unmet Social Needs and No-Show Visits in Primary Care in a US Northeastern Urban Health System, 2018–2019. https://doi.org/102105/AJPH2020305717. 2020;110:S242–S250. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semple-Hess JE, Pham PK, Cohen SA, Liberman DB. Community Resource Needs Assessment Among Families Presenting to a Pediatric Emergency Department. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(4):378–385. doi: 10.1016/J.ACAP.2018.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindau ST, Makelarski JA, Abramsohn EM, et al. CommunityRx: A real-world controlled clinical trial of a scalable, low-intensity community resource referral intervention. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(4):600–606. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tung EL, Abramsohn EM, Boyd K, et al. Impact of a Low-Intensity Resource Referral Intervention on Patients’ Knowledge, Beliefs, and Use of Community Resources: Results from the CommunityRx Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(3):815–823. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05530-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moynihan DP, Herd P. How Administrative Burdens Can Harm Health. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20200904.405159/abs/. Published 2020. Accessed February 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vasan A, Kenyon CC, Feudtner C, Fiks AG, Venkataramani AS. Association of WIC Participation and Electronic Benefits Transfer Implementation. JAMA Pediatr. March 2021:E1–E8. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.6973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vasan A, Kenyon CC, Roberto CA, Fiks AG, Venkataramani AS. Association of Remote vs In-Person Benefit Delivery With WIC Participation During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. August 2021. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2021.14356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgenlander MA, Tyrrell H, Garfunkel LC, Serwint JR, Steiner MJ, Schilling S. Screening for Social Determinants of Health in Pediatric Resident Continuity Clinic. Acad Pediatr. 2019;000:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, Lewis RA, Thompson RE, Serwint JR. Improving the Management of Family Psychosocial Problems at Low-Income Children’s Well-Child Care Visits: The WE CARE Project. Pediatrics. 2007. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dworkin PH. Towards a critical reframing of early detection and intervention for developmental concerns. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015;36(8):637–638. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pantell MS, Hessler D, Long D, et al. Effects of In-Person Navigation to Address Family Social Needs on Child Health Care Utilization: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e206445–e206445. doi: 10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2020.6445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gundersen C, Hake M, Dewey A, Engelhard E. Food Insecurity during COVID‐19. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. October 2020:aepp.13100. doi: 10.1002/aepp.13100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunn CG, Kenney E, Fleischhacker SE, Bleich SN. Feeding Low-Income Children during the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):e40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polk S, Leifheit KM, Thornton R, Solomon BS, DeCamp LR. Addressing the Social Needs of Spanish- and English-Speaking Families in Pediatric Primary Care. Acad Pediatr 2020;20(8):1170–1176. doi: 10.1016/J.ACAP.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]