Abstract

Introduction

Numerous therapeutic agents specifically targeting the mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) oncogene are being developed.

Objective

The aim of the current review was to systematically identify and analyze clinical trials that have evaluated MET inhibitors in various cancer types and to provide an overview of their clinical outcomes.

Methods

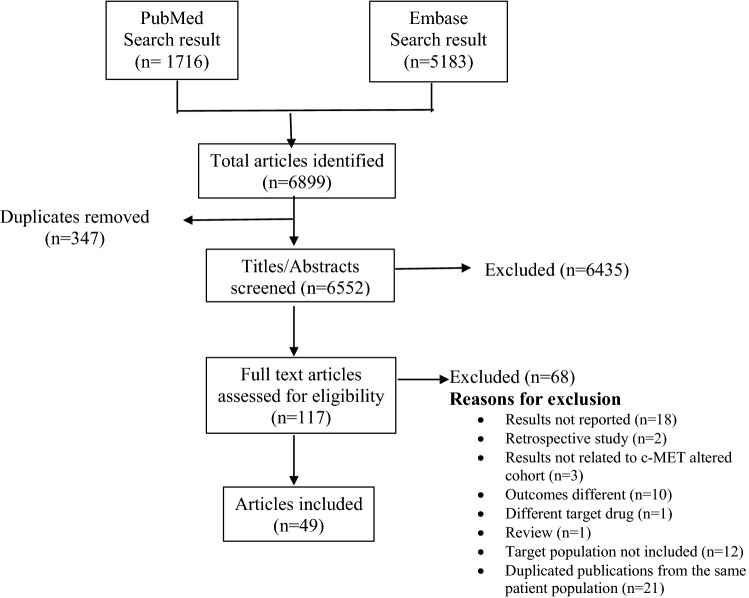

An electronic literature search was carried out in the PubMed and Embase databases to identify published clinical trials related to MET inhibitors. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement was followed for the systematic appraisal of the literature. Data related to clinical outcomes, including progression-free survival, overall survival, objective response rate, and overall tumor response, were extracted.

Results

In total, 49 publications were included. Among these, 51.02% were phase II studies, 14.28% were randomized controlled trials, three were phase III studies, two were prospective observational studies, and the remainder were either phase I or Ib studies. The majority (44.89%) of articles reported the clinical outcomes of MET inhibitors, including small molecules, monoclonal antibodies, and other agents, in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring MET alterations. MET amplification, overexpression, and MET exon 14 skipping mutations were the major MET alteration types reported across the included studies. Clinical responses/outcomes varied considerably.

Conclusion

This systematic literature review provides an overview of the literature available in Embase and PubMed regarding MET-targeted therapies. MET-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (capmatinib, tepotinib, and savolitinib) may become a new standard of care in NSCLC, specifically with MET exon 14 skipping mutations. A combination of MET TKIs with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) TKIs (osimertinib + savolitinib, tepotinib + gefitinib) may be a potential solution for MET-driven EGFR TKI resistance. Further, MET alteration (MET amplification/overexpression) may be an actionable target in gastric cancer and papillary renal cell carcinoma.

Key Points

| Mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) activity is dysregulated through diverse oncogenic alterations across a wide range of human cancers. |

| Several MET inhibitors targeting the hepatocyte growth factor/MET axis have been developed and used either as monotherapy or in combination therapy. |

| MET-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) might become the new standard of care in subsets of patients with MET alterations and MET-driven epidermal growth factor receptor TKI resistance. |

Introduction

In the past two decades, enormous advances have been made in the understanding of biological, genetic, and molecular mechanisms leading to cancer, and this has fueled the introduction of targeted therapies in cancer [1, 2]. Mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) proto-oncogene—receptor tyrosine kinase or hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) receptor—belongs to a family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and, along with its ligand HGF (HGF/MET axis), is involved in transduction pathways and modulates essential cellular processes under normal physiological conditions [3]. Copious evidence has indicated that diverse oncogenic alterations, including mutations, MET amplification, MET overexpression, chromosomal rearrangements, and fusions, cause dysregulation of the HGF/MET axis and lead to a wide range of human cancers [4, 5]. In addition to its physiological and pathological roles, increasing evidence implicates MET as a common mechanism of resistance to targeted therapies (epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR] and vascular EGFR [VEGFR] inhibitors) due to crosstalk between other RTKs [6, 7]. Based on this evidence, the HGF/MET axis has been explored as an intriguing actionable therapeutic target for drug development in different cancer types [8].

In the last decade, several MET inhibitors, including monoclonal antibodies, bispecific antibodies (bsAb), antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) and small molecules, have been developed and are in various phases of clinical evaluation [4, 5, 8]. These agents are used either as monotherapy or in combination therapy with other agents in various cancers [8, 9]. In March 2020, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare approved tepotinib for the treatment of unresectable, advanced, or recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with MET exon 14 skipping mutation [10, 11]. In May of the same year, the US FDA approved capmatinib for the treatment of adult patients with NSCLC with MET exon 14 skipping mutation. In addition, in July 2020, the China National Medical Products Administration granted priority review status to the new drug application for savolitinib, which was then approved in June 2021 for the treatment of NSCLC with MET exon 14 skipping mutations. Globally, this was the first NDA filing for savolitinib and the first in China for a selective MET inhibitor [12]. These approvals not only bridge the gap in the treatment landscape for MET-altered NSCLS but also drive the new era of MET inhibitors. The current systematic literature review summarizes and provides an overview of the clinical outcomes with various MET inhibitors (monoclonal antibodies and small-molecule inhibitors) in different cancer types.

Methodology

Evidence Acquisition

This systematic review was conducted following PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [13]. Figure 1 summarizes the search process.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow chart: Search process for study selection

Study Selection

An electronic literature search was carried out in the PubMed and Embase databases, with the final search on 8 February 2021. The following search strings were used.

PubMed: ((c-MET alterations OR c-MET aberrations OR MET amplification OR copy number gain OR MET mutations OR MET exon 14 skipping mutation) OR (TKI resistance) AND (c-MET inhibitors OR c-MET targeted therapy OR antibody-based c-MET inhibitors OR c-MET targeted antibodies) OR c-MET inhibitor combination therapy OR c-MET inhibitor treatment regimen)).

Embase: “c-MET alterations” OR “c-MET aberrations” OR “MET amplification” OR “copy number gain”/exp OR “copy number gain” OR “MET mutations” OR “MET exon 14 skipping mutation” OR “TKI resistance” OR “c-MET inhibitors” OR “c-MET targeted therapy” OR “antibody-based c-MET inhibitors” OR “c-MET targeted antibodies” OR “c-MET inhibitor combination therapy.”

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

As per the PRISMA statement, the inclusion criteria were prospectively defined. Articles (abstracts and full texts) were screened for eligibility independently by two reviewers. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)/observational studies that included patients with confirmed MET alterations, reported clinical outcomes of MET-targeted therapies in different cancers, and were published in the English language were included. During the screening process, we excluded duplicates, non-English articles, duplicate publications from the same patient population, case reports, articles reporting insufficient/inappropriate data, therapies including only chemotherapy regimens, reviews, and meta-analyses. The remaining articles (abstracts and full text) were reviewed by two independent reviewers until consensus was reached, with any disagreements resolved by the third reviewer.

A data extraction algorithm was constructed, and the following data were extracted from each included study: (1) MET inhibitor, (2) cancer type, (3) study type, (4) number of patients, (5) number of patients with MET positivity, (6) progression-free survival (PFS), (7) overall survival (OS), (8) objective response rate (ORR), and (9) overall tumor response. We used the Jadad scale and the Newcastle–Ottawa scale to evaluate the methodological quality of included RCTs and non-RCTs, respectively. The study was prospectively registered on the PROSPERO website (CRD42021268933).

Results

The electronic literature search retrieved 6552 references; after duplicates were removed, 49 were considered for final review: three were phase III studies, 25 were phase II studies, seven were RCTs, two were prospective observational studies, and the remainder were phase I or phase Ib studies (Table 1). The finalized studies were grouped according to cancer type: NSCLC (44.89%), papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC) (12.24%), gastric cancers (16.32%), and other cancers (26.53%) (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5).

Table 1.

Summary of identified studies

| Study no. | Study | Study design | Cancer type | Diagnostic platform | MET alteration type | MET positivity criteria | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Paik et al. [19] |

Phase II | NSCLC (advanced/metastatic) | NGS | MET exon 14 SM | – | 4 |

| 2 |

Lu et al. [23] |

Phase II | PSC and other NSCLC | – | MET exon 14 SM | – | 3 |

| 3 |

Drilon et al. [17] |

Phase I (NCT00585195) (PROFILE 1001) |

NSCLC | NGS | MET exon 14 SM | – | 3 |

| 4 |

Wolf et al. [85] |

Phase II | NSCLC (stage IIIB/IV) | – | MET exon 14 SM | – | 3 |

| 5 |

Wu et al. [33] |

Phase Ib/II | NSCLC | FISH, IHC | MET amp | MET GCN ≥ 5, MET/CEP7 ratio ≥ 2.0, or MET OE; ≥ 50% of tumor cells with IHC 3+ or IHC 2+ with MET GCN > 5 and then to 50% of tumor cells with IHC 3+ or MET GCN > 4 | 4 |

| 6 |

Sequist et al. [32] |

Phase Ib | NSCLC (locally advanced or metastatic) | FISH, NGS, IHC | MET amp | MET GCN ≥ 5 or MET/CEP7 ratio ≥ 2; IHC (MET +3 expression in ≥ 50% of tumor cells), or NGS (≥ 20% tumor cells, coverage of ≥ 200 × sequencing depth and ≥ 5 copies) | 4 |

| 7 |

Camidge et al. [42] |

Phase I | NSCLC (advanced) | – | MET amp | MET/CEP7 ratios ≥ 1.8 | 3 |

| 8 |

Yang et al. [37] |

Phase Ib study | NSCLC (advanced) | FISH | MET amp | MET/CEP7 ratio 2, MET gene number 5 | 3 |

| 9 |

Li et al. [86] |

Prospective observational |

NSCLC (advanced) | FISH, IHC | MET OE | MET/CEP7 ratio > 5 copies or MET/CEP7 ratio ≥ 1.8 (low ≥ 1.8 to ≤ 2.2, intermediate > 2.2 to < 5, high ≥ 5) | 3 |

| 10 |

Nishio et al. [38] |

Phase I | NSCLC | IHC, SISH | MET OE | IHC 2+ or 3+ | 3 |

| 11 |

McCoach et al. [39] |

Phase I | Lung adenocarcinoma | IHC, FISH, RT-PCR, NGS | MET expression | – | 3 |

| 12 |

Park et al. [87] |

Observational study |

NSCLC (stage IIIB/IV) | – | MET OE/MET amp | IHC 2+ or 3+ defined as positivity | 3 |

| 13 |

Wu et al. [30] |

Phase Ib/II | NSCLC (advanced or metastatic) | IHC, ISH (FISH) | MET OE or MET amp | IHC 2+ or 3+, GCN ≥ 5, MET/(CEP7) ratio of ≥ 2:1 | 3 |

| 14 |

Schuler et al. [80] |

Phase I | NSCLC (stage IIIB or IV) | IHC, FISH, NGS | MET amp, MET OE | MET H-score ≥ 150 or MET/centromere ≥ 2.0, or MET GCN ≥ 5, or ≥ 50% of tumor cells, IHC score 2+ or 3+ | 3 |

| 15 |

Camidge et al. [36] |

Phase Ib | NSCLC | IHC | MET amp/MET exon 14 SM | IHC H-score ≥ 150 | 3 |

| 16 |

Landi et al. [88] |

phase II | NSCLC (locally advanced or metastatic) | FISH, Sanger sequencing | MET exon 14 SM/MET amp | MET/CEP7 ratio > 2.2 | 5 |

| 17 |

Moro-Sibilot et al. [89] |

Phase II | NSCLC (locally advanced or metastatic) | IHC, FISH, NGS | MET amp and mutation (exons 14 and 16–19) | IHC 2+ or 3+, MET amp threshold ≥ 6 copies, MET/CEP7 ratio: high polysomy (< 1.8 c-MET/centromere), low (≥ 1.8–≤2.2), intermediate (> 2.2–< 5.0), and high (≥ 5.0) amps | 5 |

| 18 |

Seto et al. [90] |

Phase II GEOMETRY mono-1 study |

NSCLC (stage IIIb or IV) | MET exon 14 SM and MET amp | GCN ≥ 10; GCN ≥ 6 and < 10; GCN ≥ 4 and < 6; GCN < 6 | 4 | |

| 19 |

McCoach et al. [91] |

Phase I/II |

NSCLC (advanced/metastatic) | FISH, RT-PCR, IHC | MET amp, MET exon 14 SM | IHC 2–3+, CNG | 3 |

| 20 |

Wolf et al. [21] |

Phase II | NSCLC | MET amp and MET exon 14 SM | GCN ≥ 10; GCN 6–9; GCN 4 or 5; GCN < 4, MET exon 14 SM and any GCN ≥ 10; MET exon 14 SM and any GCN | 3 | |

| 21 |

Felip et al. [92] |

Phase Ib/II (NCT02335944) | NSCLC (stage IIIB/IV) | – | IHC 3+ and/or GCN ≥ 4 | 2 | |

| 22 |

Camidge et al. [40] |

Phase II | NSCLC stage IV | IHC | – | IHC: ≥ 10% of cells ≥ 2+ | 1 |

| 23 |

Van Cutsem et al. [50] |

Phase II | Gastric/GEJ/esophageal, and other solid tumors | FISH (IQ FISH) | MET amp | MET/CEN-7 ratio ≥ 2.0 | 4 |

| 24 |

Kang et al. [51] |

Phase I | Advanced GEC | FISH | MET amp | MET/CEP7 ratio > 2 in ≥ 20% | 3 |

| 25 |

Shah et al. [52] |

Phase II | Gastric cancer (metastatic) | FISH | MET amp | – | 3 |

| 26 |

Aparicio et al. [54] |

Phase II | Esogastric adenocarcinoma | FISH, IHC | MET amp | IHC scores ≥ 2+, GCN > 6 MET copies, whatever the MET/CEN7 ratio | 3 |

| 27 |

Shah et al. [56] |

Phase III | Advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma | IHC | MET OE | IHC 1+, 2+, or 3+ | 5 |

| 28 |

Iveson et al. [55] |

Phase Ib |

Advanced or metastatic gastric or esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma | FISH | MET OE (FISH) | MET probe to centromere probe of > 2; as ≥ 15 MET gene copies in 10% of tumor cells; or as four or more MET gene copies in 40% of tumor cells; 25% tumor membrane staining cutoff | 2 |

| 29 |

Lee et al. [53] |

Phase II NCT02299648: savolitinib monotherapy (biomarker D, NCT02449551); savolitinib + docetaxel (biomarker D, NCT02447406), savolitinib + docetaxel (biomarker E, NCT02447380) |

Metastatic and/or recurrent gastric adenocarcinoma | NGS, IHC | MET amp/MET OE | MET OE by IHC 3+ | 4 |

| 30 |

Kim et al. [70] |

Phase I | GC, melanoma, sarcoma, rectal cancer | IHC, FISH | MET OE/MET amp | MET/CEP7 ratio > 2.0 | 3 |

| 31 |

Catenacci et al. [93] |

Phase III (NCT01697072) | Locally advanced or metastatic gastric or GEJ adenocarcinoma | IHC | – | IHC (defined as ≥ 25% of tumor cells with membrane staining of ≥ 1+ intensity) | 3 |

| 32 |

Schöffski et al. [58] |

Phase II | PRCC (type I) | FISH | MET mutation exons (16–19)/MET amp | MET/CEP7 ratio ≥ 2 | 4 |

| 33 |

Choueiri et al. [59] |

Phase II | PRCC (type I and II) | – | MET/HGF GCN gain | – | 3 |

| 34 |

Gan et al. [94] |

Phase I | PRCC | – | MET copy number increase | – | 3 |

| 35 |

Choueiri et al. [95] |

Phase II | PRCC (advanced) | – | Germline MET mutation (n = 11), somatic mutation (n = 5), gain of chromosome 7= (n = 18), MET amp (n = 2) | – | 4 |

| 36 |

Choueiri et al. [57] |

Phase III (NCT03091192) | Metastatic papillary renal cancer | – | MET amp, chromosome 7 gain | – | 2 |

| 37 |

Suarez Rodriguez et al. [60] |

Phase I/II (NCT02819596) | Metastatic papillary renal cancer | – | MET expression | 3 | |

| 38 |

Angevin et al. [68] |

Phase I | Solid tumors | IHC, FISH | MET amp | IHC: MET (t-MET) protein expression (>/= 50% of tumor cells with 2+ or 3+ positive, MET amp (≥ 10% of cells with > 4, t-MET/CEP7 ratio ≥ 2, MET positivity (H-score 15) | 3 |

| 39 |

Shitara et al. [69] |

Phase I | Solid tumors (GC, colorectal, lung. kidney) | FISH, IHC | MET amp | MET-amplified if ≥ 10% of cells had GCN > 4, MET:CEP7 ratio ≥ 2. IHC > 50% of tumor cells with IHC 2+ or 3+ | 3 |

| 40 |

Bang et al. [67] |

Phase I | Solid tumors | FISH, IHC | MET OE | MET H-score ≥ 150 or MET/centromere ratio ≥ 2.0, MET GCN ≥ 5, IHC ≥ 50% of tumor cells with score 2+ or 3+; for HCC and GBM, a MET H-score ≥ 50 or a ratio of MET/centromere ≥ 2.0 or MET GCN ≥ 5 | 3 |

| 41 |

Bang et al. [65] |

Phase I | Solid tumors (advanced) | FISH, IHC | – | – | 3 |

| 42 |

Strickler et al. [66] |

Phase I | Advanced solid tumors (lung, GC, esophageal, ovarian, and colorectal cancer) | FISH, NGS | MET amp | MET/CEP7 ratio ≥ 2 in ≥ 20% of cells | 4 |

| 43 |

Schöffski et al. [64] |

Phase II (NCT01524926) | Advanced or metastatic clear-cell sarcoma | FISH | – | – | 3 |

| 44 |

Van den Bent et al. [62] |

Phase Ib/II | Glioblastoma | FISH, IHC, NGS | MET amp | MET-amplified GCN > 5 | 3 |

| 45 |

Hu et al. [96] |

Phase I (NCT02978261) | Gliomas (high grade) | ZM fusion and/or METex14 | – | 2 | |

| 46 |

Jia et al. [61] |

Phase I/II | Metastatic colorectal cancer | – | MET amp | – | 3 |

| 47 |

Decaens et al. [63] |

Phase II | HCC (advanced) | IHC, ISH | MET amp | MET/CEP7 ratio ≥ 2 or GCN ≥ 5, IHC, moderate (2+) or strong (3+) | 3 |

| 48 |

Banck et al. [71] |

Phase I | RCC, HCC, NSCLC | IHC | MET OE | IHC: ≥ 50% of cells ≥ 2+ | 3 |

| 49 |

Harding et al. [72] |

Phase Ib/II (NCT02082210) | GC (n = 16), HCC (n = 45), RCC (n = 15), NSCLC (n = 15) | IHC | MET OE | MET expression of 2+ staining intensity in ≥ 50% or < 50% of their tumor cells | 3 |

The Jadad scale was used to assess the randomized controlled trials, and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used to assess the quality of the non-randomized studies

amp amplification, CEP7 Chromosome 7 centromere, FISH fluorescence in-situ hybridization, GBM glioblastoma, GC gastric cancer, GCN gene copy number, GEC gastric or esophageal cancer, GEJ gastroesophageal junction, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, HGF hepatocyte growth factor, IHC immunohistochemistry, IQ FISH interphase quantitative FISH, ISH in situ hybridization, MET mesenchymal-epithelial transition, NGS next-generation sequencing, no. number, NSCLC non-small-cell lung cancer, OE overexpression, PRCC papillary renal cell carcinoma, PSC pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma, RCC renal cell carcinoma, RT-PCR reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, SISH silver in situ hybridization, SM skipping mutation

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes of MET inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer with MET exon 14 skipping mutation

| Study | Study design | Cancer type | Study, population (MET +) | MET alteration type | Therapy | ORR, % | mPFS, months | OS, months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drilon et al. [17] | Phase I (NCT00585195) PROFILE 1001 | NSCLC | 69 (65 evaluable) | MET exon 14 alteration | Crizotinib 250 mg BID in continuous 28-d cycles | 32 (95% CI 21–45) | 7.3 (95% CI 5.4–9.1) | 20.5 (95% CI 14.3–21.8) |

| Paik et al. [19] | Phase II (NCT02864992) VISION study | NSCLC (advanced/metastatic) | 169 (152 received treatment) | MET exon 14 SM | Tepotinib 500 mg OD | Independent review 46%; investigator assessment 56% | Combined biopsy 8.5; liquid biopsy 8.5; tissue biopsy 11.0 | 17.1 |

| Wolf et al. [21] | Phase II (NCT02414139) | NSCLC (stage IIIB/IV) | 97 (cohort 4: 69 pts; cohort 5b: 28 pts) | MET exon 14 SM | Capmatinib 400 mg BID | Cohort 4: 41%; cohort 5b: 68% | BIRC 5.4 and 12.4 for cohorts 4 and 5b | NR |

| Lu et al. [23] | Phase II (NCT02897479) | PSC, NSCLC | 593 (70 [60 evaluable; 25 PSC, 45 other NSCLC]) | MET exon 14 SM | Savolitinib 600 and 400 mg | Tumor response evaluable set: 49.2 (95% CI 36.1–62.3); FAS 42.9 (95% CI 31.1–55.3) | Overall 6.8 (95% CI 4.2–9.6); PSC 5.5 (95% CI 2.8–6.9); other NSCLC 6.9 (95% CI 4.2–13.8) | 12.5 (95% CI 10.5–23.6) |

BID twice daily, BIRC blinded independent review committee, CI confidence interval, FAS full analysis set, mPFS median progression-free survival, NR not reported, NSCLC non-small-cell lung cancer, OD once daily, ORR objective response rate, OS overall survival, PSC pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma, pts patients, SM skipping mutation

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes of MET inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer with MET amplification/overexpression

| Study | Study design | Cancer type | Study; population (MET +) | MET alteration type | MET alteration status | Therapy | ORR, % | mPFS, mo | OS, mo | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monotherapy | |||||||||||

| Camidge et al. [42] | Phase I (NCT00585195) | Advanced NSCLC | 40 (37 evaluable) | MET amp | – | Crizotinib 250 mg BID | MET/CEP7 category: low (≥ 1.8–≤ 2.2) 33.3%; medium (> 2.2–< 5) 14.3%; high (≥ 5) 40.0% | MET/CEP7 category: low 1.8 mo; medium 1.9 mo; high 6.7 mo | – | ||

| Li et al. [86] | Prospective observational | Advanced NSCLC | 33 (23 evaluable) | MET OE | De novo | Crizotinib | – |

3.2 mo (ITT population) MET IHC (100%+++): 7.4 mo vs. MET IHC (50%++w100%+++) 1.9 m mo. For FISH-positive pts, 8.2 mo and FISH negative m 1.3 mo |

13.2 | ||

| Landi et al. [88] | Phase II (NCT 02499614) | NSCLC (locally advanced or metastatic) | 26 (MET amp [ n = 16], MET exon 14 SM [ n = 9], concurrent amp and mutation [ n = 1]) | MET exon 14 SM/MET amp | – | Crizotinib 250 mg BID | 27% | 4.4 mo; 6-mo PFS: 30.9%; 12-mo PFS: 20.6% | Mo 5.4: 6-mo OS: 43.9%; 12-mo OS: 26.3% | ||

| Wolf et al. [21] | Phase II | NSCLC | 364 | MET amp/MET exon 14 SM | – | Capmatinib 400-mg tablet BID |

GCN ≥ 10: 29 (19–41) GCN 6–9: 12 (4–26) GCN 4 or 5: 9 (3–20) GCN < 4: 7 (1–22) MET exon 14 SM and any GCN: 41 (29–53) GCN ≥ 10: 40 (16–68) MET exon 14 SM and any GCN: 68 (48–84) GCN ≥ 10, MET exon 14 SM and any GCN: 48 (95% CI 30–67) |

GCN ≥ 10: 4.1 (2.9–4.8) GCN 6 to 9: 2.7 (1.4–3.1) GCN 4 or 5: 2.7 (1.4–4.1) GCN < 4: 3.6 (2.2–4.2) MET exon 14 SM and any GCN: 5.4 (4.2–7.0) GCN ≥ 10: 4.2 (1.4–6.9) MET exon 14 SM and any GCN: 12.4 (8.2–NE) |

– | ||

| Moro-Sibilot et al. [89] | Phase II (NCT02034981) | NSCLC (locally advanced or metastatic) | MET > 6 copies cohort (n = 25), MET-mutated cohort (n = 28) (MET exon 14; n = 25) | MET amp and mutation (exons 14 and 16–19) | – | Crizotinib 250 mg BID | MET > 6 copies cohort: at 2 cycles 16%. Best ORR 32%. MET exon 14 cohort: ORR at 2 cycles 12%, best ORR 40% | MET > 6 copies cohort: 3.2 mo; MET exon 14 cohort: 3.6 mo | MET > 6 copies cohort: 7.7 mo; MET exon 14 cohort: 9.5 mo | ||

| Seto et al. [90] | Phase II GEOMETRY mono-1 study (NCT02414139) | Stage IIIb or IV NSCLC | 45 (Japanese) | MET exon 14 SM, MET amp | – | Capmatinib 400-mg tablets BID fasting (21-day cycles) | GCN ≥ 10: 5 (16.7–76.6); GCN ≥ 4 and < 6: 1 (0.3–44.5); GCN < 6:1 (0.4–64.1); GCN ≥ 10: 2 (15.8–100.0) | – | – | ||

| Schuler et al. [80] | Phase I (NCT01324479) | Advanced NSCLC (stage IIIB or IV) | 55 | MET amp, MET OE | – | Capmatinib 600 or 400 mg BID | Investigator assessment 20%; BIRC 22% | Investigator assessment 3.7 mo; BIRC assessment 3.7 mo | – | ||

| Park et al. [87] | Observational | Stage IIIB/IV NSCLC | 196. SISH positive (n = 20), IHC positive (n = 87) | MET OE/MET amp | – | Erlotinib 150 mg PO (28 days) | IHC positive: 8 (9.2%); SISH positive 1 (5.0%) | IHC positive: 2.0 (1.8–2.2), SISH positive: 1.7 (1.2–2.2) | – | ||

| Combination therapy | |||||||||||

| Tepotinib plus gefitinib | |||||||||||

| Wu et al. [30] | Phase Ib/II (NCT01982955) RCT | NSCLC advanced or metastatic | 55 | MET OE or MET amp | Acquired | Tepotinib 500 mg/day plus gefitinib 250 mg vs. chemotherapy (pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 + cisplatin 75 mg/m2 or carboplatin; n = 24) | Overall: 45%, MET IHC 3+: 4.33; MET amp: 2.67 vs. 8% (33%) | Investigator-assessed: 4.9 vs. 4.4 mo: mPFS (investigator assessment) was 8.3 mo with tepotinib plus gefitinib vs. pts with MET IHC3+ and doubled to 16.6 mo with tepotinib plus gefitinib in pts with MET amp | Overall: 17.3 mo vs. chemotherapy: 18.7 mo; MET IHC3+: OS 37.3 vs. 17.9 mo; MET amp: OS 37.3 vs. 13.1 mo | ||

| Osimertinib plus savolitinib | |||||||||||

| Sequist et al. [32] | Phase Ib (NCT02143466) | NSCLC (locally advanced or metastatic) | Part B 138 pts. Subcohort B1 = 72 (previous EGFR TKI treatment); B2 = 54 no EGFR-TKI pretreatment and Thr790Met negative; B3: 18 no previous EFGR TKI, Thr790Met-positive pts | MET amp | Acquired | Osimertinib 80 mg plus savolitinib 600 mg | Overall part B 48%. B1: 30%; B2: 65%; B3: 67% | Overall part B; median 7.6 mo. B1: 5.4 mo; B2: 9.0 mo; B3: 11.0 mo | – | ||

| Part D: 42 pts. No previous third-generation EFGR TKI, Thr790Met-negative pts | MET amp | Osimertinib 80 mg plus savolitinib 300 mg | 64% | 9.1 mo | – | ||||||

| Other combination therapies | |||||||||||

| Wu et al. [33] | Phase Ib/II (NCT01610336) | NSCLC (n = 161) | Phase Ib (n = 61) | MET amp | Acquired | Gefitinib 250 mg OD + capmatinib 100–800 mg OD or 200–600 mg BID | 0.23% | – | – | ||

| Phase II (n = 100) | Capmatinib 400 mg BID plus gefitinib 250 mg OD | Overall: 29%; GCN ≥ 6 (n = 36): 47%; 4 ≤ GCN < 6 (n = 18): 22%; GCN < 4 (n = 41): 12%; IHC 3+ (n = 78): 32%; IHC 2+ (n = 16): 19%; IHC 0 (n = 4): 25% | All pts: 5.5–5.6 mo; GCN ≥ 6 (n = 36), 5.49–7.29 mo; GCN < 6 (n = 18) 5.39–7.46 mo; GCN < 4 (n = 41) 3.91–5.55 mo; IHC 3+ (n = 78) 5.45 –7.10 mo; IHC 2+/GCN ≥ 5 (n = 8) 7.29–9.07 mo | – | |||||||

| Yang et al. [37] | Phase Ib (NCT02374645) | NSCLC (advanced) | 44 | MET amp | Acquired | Savolitinib 600 mg OD plus gefitinib 250 mg OD | – | – | – | ||

| McCoach et al. [39] | Phase I (NCT01911507) | Lung adenocarcinoma | 18 | MET expression | – | INC280 five dose levels (100–600 mg PO BID) + erlotinib 100 and 150 mg | – | – | – | ||

| McCoach et al. [91] | Phase I/II (NCT01911507) | Advanced/metastatic NSCLC | 17 | MET amp, MET exon 14 SM | – | INC280: 400 mg BID + erlotinib 150 mg BID | Cohort A (EGFR mutant n = 12) 50%; cohort B (EGFR wildtype, n = 5) 75% | – | – | ||

| Nishio et al. [38] | Phase I (JO25725; JapicCTI-111563) | NSCLC | Six: five adenocarcinoma, one SCC | MET OE | – | Onartuzumab 15 mg/kg plus erlotinib 150 mg/day PO | – | – | – | ||

| Camidge et al. [36] | Phase1b (NCT02099058) | NSCLC | 42 (37 [36 evaluable]; EGFR M+ in 29 pts, EGFR M- in 7 pts) | MET amp/MET exon 14 SM | – | Telisotuzumab vedotina 2.4 mg/kg (dose-escalation phase) or 2.7 mg/kg plus erlotinib 150 mg OD |

EGFR M+: 34.5% EGFR M-: 28.6% |

EGFR M+ group mo NR; EGFR M - group 5.9 mo | – | ||

| Felip et al. [92] | Phase Ib/II (NCT02335944) | Stage IIIB/IV NSCLC | 68 (23) | – | Acquired | Capmatinib 400 mg BID + nazartinib 100 mg OD | 43.5 (23.2–65.5) | 7.7 (5.4–12.2) | 18.8 (14.0–21.3) | ||

| Camidge et al. [40] | Phase II (NCT01900652) (RCT) | NSCLC stage IV | 111 | – | Acquired | IV LY 750 mg Q2W + erlotinib 150 mg OD on a 28-day cycle | LY + E 3.0%, LY 4.3% | LY + E (3.3 mo), LY (1.6 mo) | NR | ||

amp amplification, BID twice daily, BIRC blinded independent review committee, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, FISH fluorescence in situ hybridization, GCN gene copy number, IHC immunohistochemistry, IRB institutional review board, IRC independent review committee, ITT intent to treat, IV intravenous, LY emibetuzumab, LY+ E emibetuzumab + erlotinib, M+ Mutation positive, M- Mutation negative, MET mesenchymal-epithelial transition, mo months, mPFS median progression-free survival, NE not evaluable, NR not reported, NSCLC non-small-cell lung cancer, OD once daily, OD once daily, OE overexpression, ORR objective response rate, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, PO oral administration, pts patients, Q2W every 2 weeks, SCC squamous cell carcinoma, SISH silver in situ hybridization, SM skipping mutation, TKI tyrosine kinase inhibitor, – indicates not reported

aABBV-399; teliso-v

Table 4.

Clinical outcomes of MET inhibitors in papillary renal cell carcinoma and gastric cancers

| Study | Study design | Cancer type | Study population (MET +) | MET alteration type | Therapy | ORR, % | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRCC | ||||||||

| Schöffski et al. [58] | Phase II (NCT01524926) | PRCC type 1 | 41 (23 eligible with PRCC) (4) | MET mutation exons (16–19)/MET amp | Crizotinib 250 mg BID | 50.0 | 1-year PFS 75.0%; 2-year PFS 75.0% | 1-year OS 75.0%; 2-year OS 75.0% |

| Choueiri et al. [59] | Phase II (NCT02127710) | PRCC (type I and II ) | 109 (44 [MET-driven group]) | MET/HGF gene copy number gain | Savolitinib (HMPL504/volitinib, AZD6094) 600 mg OD | – | 6.2 mo | – |

| Gan et al. [94] | Phase I (NCT01773018) | PRCC | 4 | MET copy number increase | AZD6094 (HMPL504/volitinib) | – | – | – |

| Choueiri et al. [95] | Phase II (NCT00726323) | PRCC (advanced) | 74 (36) | Germline MET mutation (n = 11); somatic mutation (n = 5); gain of chromosome 7= (n = 18); MET amp (n = 2) | Foretinib 240 mg OD (intermittent arm); cohort B, foretinib 80 mg daily (daily dosing arm) | – | – | – |

| Choueiri et al. [57] | Phase III NCT03091192 | Metastatic PRCC | 60 | MET amp, chromosome 7 gain | Savolitinib 600 mg PO (or 400 mg if < 50 kg) OD continuously, or sunitinib 50 mg PO OD in 6-wk cycles of 4 wks tx followed by 2 wks without tx | – | Savolitinib 7.0 (2.8–NC); sunitinib 5.6 (4.1–6.9) | Savolitinib NC (11.9–NC); sunitinib 13.2 (7.6–NC) |

| Suarez Rodriguez et al. [60] | Phase I/II (NCT02819596) | Metastatic PRCC | 42 (41) | MET expression | Durvalumab 1500 mg Q4W and savolitinib 600 mg OD | Overall: 27%; previously untreated cohort (n = 27) 33% | 4.9 mo (95% CI 2.5–12.0) | Overall: 12.3 mo (95% CI 5.8–21.3); previously untreated cohort 12.3 mo (95% CI 4.7–not reached) |

| Gastric cancers | ||||||||

| Aparicio et al. [54] | Phase II (NCT02034981) | Esogastric adenocarcinoma | 570 | MET amp | Crizotinib 250 mg BID | 55.6% | 3.2 mo | 8.1 mo |

| Van Cutsem et al. [50] | Phase II (NCT02016534) | GC/GEJ/esophageal and other solid tumors | 60 | MET amp | AMG 337 × 300 mg PO OD) | Overall 16% | 3.4 mo | 7.9 mo |

| Kang et al. [51] | Phase I (NCT01472016) | Advanced GEC | 6 (4) | MET amp | ABT-700 × 15 mg/kg IV | 75% | 27, 18, and 24 wks, for three pts with PR | – |

| Shah et al. [52] | Phase II (NCT00725712) | Metastatic GC | 74 (3 [intermittent cohort]) | MET amp | Foretinib 240 mg/day | – | 1.7 mo | – |

| Shah et al. [56] | Phase III (NCT01662869) RCT | Advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma | 562 (onartuzumab plus mFOLFOX6 [ n = 279] vs. PL plus mFOLFOX6 [ n = 283]) (MET 2+/3+ GEC in the PL plus mFOLFOX6 109 [38.5%]; MET 2+/3+ GEC in onartuzumab plus mFOLFOX6 groups, 105 [37.6%]) | MET OE | Onartuzumab 10 mg/kg plus mFOLFOX6 vs. PL + mFOLFOX6 | 44.6 vs. 53.8% | 6.7 vs. 6.8 mo | 11.0 vs. 11.3 mo |

| Lee et al. [53] | Phase II NCT#02299648: savolitinib monotherapy (biomarker D, #02449551); savolitinib + docetaxel (biomarker D, NCT#02447406), savolitinib + docetaxel (biomarker E, NCT#02447380); | Metastatic and/or recurrent gastric adenocarcinoma | 715; MET amp (25/715, 3.5%); MET OE by IHC 3+ (42/479, 8.8%) | MET amp/MET OE | Savolitinib | 50% (10/20; 95% CI 28.0–71.9) | – | – |

| Iveson et al. [55] | Phase Ib (NCT00719550) | Advanced or metastatic gastric or esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma | 121 included (91) | MET OE | Rilotumumab 15 mg/kg + ECX (epirubicin 50 mg/m2 IV on D1, cisplatin 60 mg/m2 IV on D1, and capecitabine 625 mg/m2 BID PO on D1–21) Q3W for maximum of 10 cycles | 20 (50%) | 5.7 mo (4.5–7.0) | 10.6 mo (95% CI 8.0–13.4) |

| Catenacci et al. [93] | Phase III study (NCT01697072) | Locally advanced or metastatic gastric or GEJ adenocarcinoma | 1477 (1291 evaluable ) (1043 c-MET +) | – | Rilotumumab 15 mg/kg IV, epirubicin 50 mg/m2 IV, and cisplatin 60 mg/m2 IV per 21-day cycle. Capecitabine 625 mg/m2 PO BID vs. PL | 29.8% (24.3–35.7) | Rilotumumab plus ECX: 5.6 (5.3–5.9); PL plus ECX 6.0 (5.7–7.2) | 8.8 mo (95% CI 7.7–10.2) with rilotumumab vs. 10.7 mo (9.6–12.4) with PL |

amp amplification, BID twice daily, CI confidence interval, D day, ECX Epirubicin cisplatin and capecitabine, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, GC gastric cancer, GEC gastric or esophageal cancer, GEJ gastroesophageal junction, HGF hepatocyte growth factor, IHC immunohistochemistry, IV intravenous, MET mesenchymal-epithelial transition, mFOLFOX6 leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin, mo month(s), NC not calculated, OD once daily, OE overexpression, ORR objective response rate, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, PL placebo, PO oral administration, PR partial remission, PRCC papillary renal cell carcinoma, pt(s) patient(s), QxW every x weeks, RCC renal cell carcinoma, RCT randomized controlled trial, tx treatment, wk(s) week(s), – indicates not reported

Table 5.

Clinical outcomes of MET inhibitors in solid tumors and other cancers

| Study | Study design | Cancer type | Study population (MET +) | MET alteration type | Therapy | ORR, % | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid tumors | ||||||||

| Bang et al. [65] | Phase I (NCT01324479) | Advanced solid tumors | 33 | – | INC280 (six dose cohorts of 100–600 mg BID) | – | – | – |

| Strickler et al. [66] | Phase I (NCT01472016) | Advanced solid tumors (lung, GC, esophageal, ovarian, and CRC) | 45 (10) | MET amp | Telisotuzumab (ADT 700) 15 mg/kg | 8.9% | 17.9 wks | – |

| Bang et al. [67] | Phase I (NCT01324479) | Solid tumors |

76 Dose-escalation cohort: n = 38 (with HCC [n = 15], colon [n = 8], GC [n = 2], lung [n = 1], and other advanced solid tumors [n = 12]) (23 evaluable pts) Dose expansion cohort: n = 38 (with HCC [n = 11], GC [n = 9], and other advanced solid tumors [non-NSCLC; n = 18]) (31 evaluable pts) |

MET OE | Capmatinib dose escalation: BID doses: 100 mg, 200 mg, 250 mg, 350 mg, 450 mg, and 600 mg. Dose expansion: 600 mg BID |

Dose-escalation cohort: 0 (0.0–9.3) Dose expansion: 0 (0.0–9.3) |

– | – |

| Angevin et al. [68] | Phase I (NCT01391533) | Solid tumors (including NSCLC) | 72 (68 involved in efficacy ); (29 pts with MET amp) | MET amp | SAR125844 (570 mg/m2) | – | – | – |

| Shitara et al. [69] | Phase I (NCT01657214) | Solid tumors (GC, CRC, lung, kidney) |

38 (19) Dose-expansion cohort: 14 (73.7%) had GC, one (5.3%) had CRC, two (10.5%) had lung cancer) Dose-escalation cohort: 3 (two with GC, one with lung cancer) |

MET amp | SAR125844 (570 mg/m2) | GC subpopulation 14.3% | – | – |

| Other cancers | ||||||||

| Hu et al. [96] | Phase I (NCT02978261) | Gliomas (high grade) | 18 | ZM fusion and/or MET exon 14 | PLB-1001: 50–300 mg BID | – | 80 days | – |

| Jia et al. [61] | Phase I/II (NCT02008383) | CRC (metastatic) | 65 (8) (7 evaluable) | MET amp | Cohort: cabozantinib + panitumumab = 4; cohort: cabozantinib = 4 | – | – | – |

| van den Bent et al. [62] | Phase Ib/II study (NCT01870726) | Glioblastoma | 10 (phase II) | MET amp | INC280 monotherapy 400 mg BID | – | – | – |

| Kim et al. [70] | Phase I (NCT# 02447406) | Seven GC, five melanoma, three sarcoma, two rectal cancer | 17 (10) | MET OE/ MET amp | Savolitinib 200 mg OD, 400 mg OD, 600 mg OD, savolitinib 800 mg + docetaxel IV 60 mg/m2) | – | – | – |

| Decaens et al. [63] | Phase II NCT02115373 | HCC (advanced) | 49 | MET amp | Tepotinib 500 mg OD | 8.2% | Overall population (n = 49) 3.4 mo; IHC 2+ (n = 41) PFS 4.0 mo; IHC 3+ (n = 8) 3.2 mo; ISH status positive (n = 6) 4.2 mo, negative (n = 43) 3.2 mo | 5.6 mo |

| Banck et al. [71] | Phase I (NCT0128756) | RCC | 19 | MET OE | Emibetuzumab 2000 mg Q2W IV | – | – | – |

| HCC | 9 | |||||||

| NSCLC | 19 | |||||||

| Schöffski et al. [64] | Phase II (NCT01524926) | Advanced or metastatic clear-cell sarcoma | 43 (36 eligible); 31 (26 evaluable) | – | Crizotinib 200 mg BID, 250 mg BID | 3.8%; 95% CI 0.1–19.6 | 131 days (49–235); 3-, 6-, 12- and 24-mo PFR 53.8% (34.6–73.0), 26.9% (9.8–43.9), 7.7% (1.3–21.7), and 7.7% (1.3–21.7) | 277 days (232–442) |

| Harding et al. [72] | Phase Ib/II (NCT02082210) | GC (n = 16), HCC (n = 45), RCC (n = 15), NSCLC (n = 15) | 97 (73 evaluable) | MET OE | Emibetuzumab 750 mg and ramucirumab 8 mg/kg IV Q2W | – | MET expression of ≥ 2+ staining intensity in ≥ 50% of tumor cells: 7.4 mo, MET expression of ≤ 2+ staining intensity in < 50% of tumor cells: 2.8 mo | – |

amp amplification, BID twice daily, CI confidence interval , CRC colorectal cancer, GC gastric cancer, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, IHC immunohistochemistry, ISH in situ hybridization, IV intravenous, MET mesenchymal-epithelial transition, mo months, NSCLC non-small-cell lung cancer, OD once daily, OE overexpression, ORR objective response rate, OS overall survival, PFR, PFS progression-free survival, pts patients, Q2W every 2 weeks, RCC renal cell carcinoma, wk(s) week(s), – indicates not reported

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)

A total of 22 studies reporting the clinical outcomes of various MET inhibitors in NSCLC harboring different MET alterations were included. Four (18.18%) studies included patients with MET exon 14 skipping mutations (Table 2), and the remaining studies included patients with MET amplification or overexpression or MET exon 14 skipping mutation/MET amplification (Table 3). In total, 12 (52.17%) studies reported on monotherapy and ten (45.45%) reported on combination therapy. The majority of the studies reported on monotherapy involving crizotinib (41.66%).

MET-Targeted Therapy in NSCLC Harboring MET Exon 14 Skipping Mutation

MET exon 14 skipping mutation is believed to be an independent driver mutation in NSCLC and is usually mutually exclusive from other drivers (e.g., EGFR, anaplastic lymphoma kinase [ALK], c-ros oncogene 1 [ROS1]) and associated with a poor prognosis. Further, comprehensive studies conducted by Awad et al. [14] and Tong et al. [15] reported that MET exon 14 skipping mutations represent a clinically unique molecular subtype of NSCLC and aid in patient stratification for personalized therapy. Many advances in targeted therapy for MET exon 14 skipping mutations in NSCLC are being reported.

Crizotinib Monotherapy

Crizotinib is a multitargeted small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) specifically targeted to ALK, ROS1 and MET. However, it is also a potent inhibitor of ALK and ROS1. It competitively inhibits ALK phosphorylation and alters downstream signal transduction, which leads to G1/S-phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [16]. The efficacy of crizotinib against tumors with MET exon 14 skipping alterations or MET amplification has not been reported in a large population. Drilon et al. [17] conducted the phase I PROFILE 1001 study (n = 69) and reported the efficacy of crizotinib (median PFS [mPFS] 7.3 months; objective response rate [ORR] 32%) in patients with advanced stage NSCLC harboring MET exon 14 skipping alteration and showed that MET inhibition with crizotinib remains a treatment option for NSCLCs with MET exon 14 alterations (Table 2) [17].

Tepotinib Monotherapy

Tepotinib is a selective MET inhibitor that disrupts the MET signal transduction pathway and exhibits potential antineoplastic activity [18]. Only one of the studies included in this analysis reported the use of tepotinib monotherapy in patients with MET exon 14 altered NSCLC. VISION was a phase II trial by Paik et al. [19] that evaluated the durable clinical activity of tepotinib 500 mg once daily (OD) in 152 patients with MET exon 14 altered NSCLC, 99 of whom were followed for at least 9 months. The authors reported that tepotinib was associated with a partial response in approximately half the patients, with an overall response rate of 46% (95% confidence interval [CI] 36–57) by independent review committee (IRC) review and of 56% (95% CI 45–66) by investigator assessment. PFS and OS were 8.5 and 17.1 months, respectively (Table 2). These findings led to the regulatory approval of tepotinib in MET exon 14 skipping mutations in March 2020 in Japan [19].

Capmatinib Monotherapy

Capmatinib is a selective small-molecule MET inhibitor that prevents activation of downstream effectors in the MET signaling pathway by blocking MET phosphorylation [20]. Wolf et al. [21] conducted a phase II study (GEOMETRY mono-1 study) involving patients with NSCLC harboring MET exon 14 skipping mutations who were assigned to cohorts according to previous lines of therapy. The authors reported that patients with NSCLC with a MET exon 14 skipping mutation who had already received one or two lines of therapy receiving capmatinib 400 mg tablet twice daily (BID) exhibited an overall response of 41% (28/69) and a mPFS of 5.2 months. Treatment-naïve patients exhibited an overall response and PFS of 68% (19/28) and 12.4 months, respectively (Table 2) [21].

Savolitinib Monotherapy

Savolitinib is an inhibitor of the MET receptor that inhibits activation of MET by disrupting the MET signal transduction pathway in an adenosine triphosphate-competitive manner, resulting in cell growth inhibition in tumors [22]. Recently Lu et al. [23] conducted a multicenter phase II trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of savolitinib 600 and 400 mg in Chinese patients with MET exon 14 altered NSCLC (n = 70). Of these patients, 25 had pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma (PSC), which is a rare aggressive NSCLC subtype, and 45 had other histologies of NSCLC. The primary endpoint was ORR (assessed by IRC), assessed in the tumor response evaluable set, with a sensitivity analysis done in the full analysis set. Savolitinib showed an encouraging ORR in patients with MET exon 14 positive NSCLC, both in the tumor response evaluable set (N = 61; ORR 49.2% [95% CI 36.1–62.3]) and in the full analysis set (N = 70; ORR 42.9% [95% CI 31.1–55.3]). Savolitinib demonstrated similar tumor responses regardless of pathological subtype (ORR 44.4% in other NSCLC vs. 40.0% in PSC) or prior line of treatment (ORR 40.5% in later line vs. 46.4% in treatment-naïve patients). A post hoc analysis found that savolitinib also resulted in adequate control of brain metastases (Table 2) [23]. Overall, MET exon 14 skipping mutations define a special genomic subtype of NSCLCs, and existing evidence suggests that MET-selective TKIs have the potential to deliver better clinical outcomes than nonselective TKIs.

MET-Targeted Combination Therapies in MET-Amplified Post Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Resistance in NSCLC

MET activation negatively affects the effectiveness of TKIs because of crosstalk between MET and RTK (EGFR) signaling pathways, as the activation of EGFR leads to increased MET activation and vice versa [24, 25]. MET amplification promotes downstream signal transduction through bypass activation to evade cell death by EGFR TKIs. Therefore, MET amplification is an important resistance mechanism of EGFR TKI, with a prevalence of 5–21% after firstline/secondline EGFR TKI resistance, ~ 15% after first-line therapy, and ~ 19% after later line osimertinib resistance [26, 27]. Moreover, it is conceivable that MET activation could differ between patients who developed MET amplification after EGFR TKI treatment and treatment-naïve patients [28]. Therefore, the use of MET inhibitors in patients with acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs may require a different strategy than in treatment-naïve patients [28]. At this juncture, the combination of MET TKI and EGFR TKI may be the solution for MET-driven EGFR TKI resistance.

Tepotinib Plus Gefitinib Combination

Gefitinib is a selective EGFR TKI that inhibits the EGFR signaling transduction pathway by blocking the autophosphorylation receptor [29]. Wu et al. [30] documented a phase Ib/II multicenter randomized trial (INSIGHT) involving EGFR-mutant NSCLC with MET overexpression (immunohistochemistry [IHC] 2+ or 3+) or MET amplification having acquired resistance to EGFR inhibition. The phase II part of the study included 55 patients, 31 of whom received tepotinib 500 mg daily plus gefitinib 250 mg, and 24 received chemotherapy (pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 + cisplatin 75 mg/m2 or carboplatin). They reported that phase II survival outcomes were similar between the groups, with a mPFS of 4.9 and 4.4 months, respectively. However, survival outcomes were better with tepotinib plus gefitinib than with chemotherapy in patients with MET IHC 3+ (median OS 37.3 vs. 17.9 months; mPFS 8.3 vs. 4.4 months) and in patients with MET amplification (median OS 37.3 vs. 13.1 months; mPFS 16.6 vs. 4.2 months), suggesting improved activity for tepotinib plus gefitinib compared with standard chemotherapy in patients with MET amplification/overexpression (Table 3) [30]. Although the INSIGHT study was a small trial (MET+ [n = 31], MET 3+ [n = 19], and MET amplification [n = 12]) and was terminated early because of enrollment difficulties, it did shed light on the benefit of combination therapy versus chemotherapy in MET IHC 3+ or MET-amplified populations with acquired resistance to EGFR inhibition.

Osimertinib Plus Savolitinib Combination Therapy

Osimertinib is a third-generation EGFR TKI that binds irreversibly to certain mutant forms of EGFR (exon 19 deletion, and double mutants containing T790M) and inhibits several downstream pathways, such as rat sarcoma/rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma/mitogen activated protein kinase (RAS/RAF/MAPK) and phosphoinositide 3 kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT), which regulate various cellular process [31]. A phase Ib trial by Sequist et al. [32] assessed osimertinib plus savolitinib in two global expansion cohorts (parts B and D) of the TATTON study. Part B consisted of three cohorts of patients: those previously treated with a third-generation EGFR TKI (subcohort B1; n = 69) and patients not previously treated with a third-generation EGFR TKI who were either Thr790Met negative (subcohort B2; n = 51) or Thr790Met positive (subcohort B3; n = 18). Part D enrolled patients with MET-amplified, EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC who had received previous treatment with first-generation or second-generation EGFR TKIs but no previous treatment with third-generation EGFR TKI and were Thr790Met negative (cohort D; n = 36). They reported a higher proportion of responses in patients in subcohort B3 and part D (ORR 67 vs. 64%) and mPFS (11 vs. 9.1 months) and a poorer response (ORR 30%, PFS 5.4 months) in patients with prior third-generation EGFR TKI therapy. The authors concluded that osimertinib plus savolitinib might be a potential treatment option for patients with MET-driven resistance to EGFR TKIs (Table 3) [32].

Capmatinib Plus Gefitinib Combination Therapy

One phase Ib/II study reported capmatinib plus gefitinib combination therapy in NSCLC [33]. Wu et al. [33] reported data from another combination (capmatinib 400 mg plus gefitinib 250 mg) in a phase Ib/II trial in patients with MET-amplified and EGFR-mutated NSCLC for whom EGFR inhibitor therapy had failed (n = 100). The phase II results showed an ORR of 29% and PFS of 5.5 months with the capmatinib plus gefitinib combination. A subgroup analysis based on MET gene copy number (GCN) and IHC categories revealed that patients with GCN ≥ 6 and IHC 3+ had better ORRs (47 and 32%, respectively) (Table 3) [33].

Other Combination Therapies

Studies reporting the clinical evidence of combination therapies including small-molecule inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies, such as capmatinib plus gefitinib [33, 34], telisotuzumab plus erlotinib [35, 36], savolitinib plus gefitinib [37], onartuzumab plus erlotinib [38], capmatinib plus erlotinib [39], and emibetuzumab plus erlotinib [40], in patients with NSCLC with MET alterations were included in this review, with PFS ranging from 3.3 to 5.6 months. Camidge et al. [40] carried out a randomized open-label phase II study of intravenous emibetuzumab 750 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W) plus erlotinib 150 mg OD versus intravenous emibetuzumab 750 mg Q2W monotherapy in patients with acquired resistance to erlotinib and MET diagnostic-positive NSCLCs (n = 111). The combination of emibetuzumab plus erlotinib demonstrated a PFS of 3.3 months and an ORR of 3%, whereas emibetuzumab monotherapy exhibited a PFS and an ORR of 1.6 months and 4.3%, respectively. The authors further concluded that acquired resistance to erlotinib in patients with MET-positive disease was not reversed by emibetuzumab plus erlotinib or by emibetuzumab alone (Table 3) [40].

MET-Targeted Therapy in NSCLC with De Novo MET Amplification/Overexpression

Tumors harboring de novo MET amplifications (high level, i.e., MET to chromosome 7 centromere (CEP7) ratio ≥ 5) are primarily dependent on the MET signaling pathway for growth [41]. These amplifications are identified in < 1–5% of NSCLCs and indicate a poor prognosis [41]. Further, the literature suggested that, compared with low-level MET amplifications, higher-level MET amplifications are more likely to be indicative of oncogenic dependence on MET, thereby offering actionable subtypes of NSCLC. On the other hand, MET overexpression represents a poor predictor of benefit from MET TKIs in the absence of a known driver of MET dependence. However, MET overexpression or de novo MET amplification as oncogenic driver events remain under debate. Some trials have used MET inhibitors in MET amplification.

Crizotinib Monotherapy

The PROFILE 1001 study by Camidge et al. [42] evaluated the efficacy of crizotinib in patients with MET-amplified NSCLC categorized according to MET/CEP7 ratios (low ≥ 1.8 to ≤ 2.2; medium > 2.2 to < 5; or high ≥ 5) and reported that patients with high MET amplification (MET/CEP7 ≥ 4) had an ORR of 40% compared with low (ORR 33.3%) and medium (ORR 14.3%) MET/CEP7 ratio groups, inferring that patients with high MET amplification could benefit from the MET-targeted therapy (Table 3) [42].

Capmatinib Monotherapy

The GEOMETRY mono-1 study evaluated the efficacy and safety of capmatinib in patients with high-level MET-amplified advanced NSCLC (GCN ≥ 10) compared with low-level (GCN < 4) or midlevel (GCN 4–5 or 6–9) MET-amplified advanced NSCLC. In this study, patients with GCN ≥ 10 and no prior line of therapy exhibited higher ORRs (40%) and PFS (4.2 months) than other cohorts, indicating a better response with higher MET amplification [21].

New MET Inhibitors for NSCLC

Findings from MET-targeted therapy studies have suggested the reliability of MET inhibitors for NSCLC. Further, these achievements paved the way for researchers across the globe to look for other MET-targeted therapies, which has resulted in the production of several MET inhibitors, including Sym 015 [43], JNJ-372 (JNJ-61186372) [44], ningetinib [45], bozitinib [46], ABBV-399 (telisotuzumab vedotin; teliso-v) [36], and ADC (TR1801-ADC) [47], among others, that are in various phases of development. However, no further information about these studies is included in the current review as they did not meet the search criteria.

Gastric Cancers

The heterogenous molecular nature of gastric cancers offers amenable molecular targets, and emerging evidence suggests that MET-aberrant signaling provides actionable therapeutic targets in gastric cancer, so these are currently the subject of intense clinical investigation [48]. This review included two phase III, four phase II, and two phase I studies evaluating clinical outcomes in advanced/metastatic gastric carcinomas (GCs). Five of these reported the clinical outcomes of MET-inhibitor monotherapy, including crizotinib, savolitinib, AMG 337, ABT-700, and foretinib, in patients with GC harboring MET amplification [49–53].

Savolitinib Monotherapy

Lee et al. [53] reported results from the phase II VIKTORY umbrella trial, demonstrating that savolitinib monotherapy in metastatic and/or recurrent gastric adenocarcinoma (n = 20) exhibited an ORR of 50% (10/20) in a subset of patients with gastric cancer harboring MET amplifications. Further genomic analysis revealed that patients with high MET GCN > 10 (by tissue next-generation sequencing) exhibited ORRs of 70% (7/10) to savolitinib, inferring that the MET-amplified subset of patients experienced the largest absolute decrease in tumor burden (Table 4) [53].

Crizotinib Monotherapy

Aparicio et al. [54] reported results from the AcSe-crizotinib program involving patients with chemotherapy-refractory MET-amplified (GCN ≥ 6) esogastric adenocarcinoma (n = 9) receiving crizotinib 250 mg BID. They found an ORR of 5/9 (55.6% [95% CI 21.2–86.3]), an mPFS of 3.2 months (95% CI 1.0–5.4), and an OS of 8.1 months (95% CI 1.7–24.6) (Table 4) [54].

Combination Therapy

Iveson et al. [55] reported the efficacy results from a double-blind randomized phase II study of rilotumumab in combination with epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine in patients with advanced gastric or esophagogastric junction cancer harboring MET overexpression. They reported an ORR of 20 (50%) and PFS and OS of 5.7 and 10.6 months, respectively (Table 4) [55]. A phase I study of a MET antibody, ABT-700, conducted by Kang et al. [51] in patients with advanced gastric or esophageal cancer with MET amplification reported that ABT-700 was well-tolerated, with an ORR of 75% (n = 4). They further concluded that MET amplification appeared to be more common in treatment-refractory tumors than in primary untreated tumors, suggesting the need for further screening efforts focusing on this treatment-refractory patient population (Table 4) [51]. Van Cutsem et al. [50] carried out a phase II multicenter single-arm cohort study of AMG 337 in patients with MET-amplified (MET/CEP-7 ratio ≥ 2.0.) gastric/gastroesophageal junction/esophageal adenocarcinoma and other MET-amplified solid tumors. AMG 337 monotherapy resulted in an overall ORR of 18% in heavily pretreated patients with advanced MET-amplified gastric/gastroesophageal junction/esophageal adenocarcinoma and overall PFS and OS of 3.4 and 7.9 months, respectively. No activity was observed in MET-amplified NSCLCs (Table 4) [50]. A phase III trial of onartuzumab 10 mg/kg plus mFOLFOX6 (leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin; n = 279) versus placebo plus mFOLFOX6 (n = 283) in patients with metastatic human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative and MET-positive gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma demonstrated that the addition of onartuzumab to first-line mFOLFOX6 did not significantly improve clinical benefits, either in the overall population or in MET 2+/3+ subgroup populations (Table 4) [56].

Several MET inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies have been tested in gastric cancers; however, only a few of the tested agents proved to be of substantial clinical benefit. A lack of consensus and poor biomarker determination, as well as the diverse resistance mechanisms, limits the clinical efficacy of MET inhibitors in gastric cancer.

Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma

We included a total of six studies analyzing the effectiveness of MET inhibitors (crizotinib, savolitinib, foretinib) in patients with PRCC harboring MET alterations. SAVOIR, a phase III randomized clinical trial, evaluated the efficacy of savolitinib 600 or 400 mg versus sunitinib 50 mg in patients with MET-amplified/chromosome 7 gain PRCC. Chouieri et al. [57] reported a PFS of 7.0 (95% CI 2.8–not calculated [NC]) versus 5.6 (95% CI 4.1–6.9) and OS NC (95% CI 11.9–NC) versus 13.2 (95% CI 7.6–NC) and further concluded that efficacy data favored savolitinib over sunitinib and showed superior safety (Table 4). Schöffski et al. [58] reported a phase II trial (the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer [EORTC] 90101 CREATE trial) in patients with type 1 PRCC with MET exon mutations (16–19)/MET amplification, demonstrating that crizotinib had higher 1-year PFS (75%) and 1-year OS (75%) rates with long-lasting disease control in a MET-positive subcohort compared with a MET-negative subcohort (PFS rate 27.3%, OS rate 36.9%) [58]. Choueiri et al. [59] also conducted a large single-arm biomarker-profiled phase II trial of savolitinib in patients with type I or II PRCC with dysregulated MET pathway (MET/HGF GCN gain) and reported a median PFS of 6.2 versus 1.4 months in MET-driven and MET-negative groups, respectively, and concluded that savolitinib has acceptable antitumor activity and tolerability in patients with MET-driven PRCC (Table 4) [59]. Besides MET inhibitor monotherapy, novel combination therapies have also been tested in PRCC. Suarez Rodriguez et al. [60] reported the OS results for durvalumab and savolitinib from a phase I/II study involving patients with metastatic PRCC (n = 42), demonstrating an overall ORR of 27% with PFS and OS of 4.9 and 12.3 months, respectively. A higher ORR of 40% was observed in the MET-positive subgroup [60] (Table 4). However, further trials involving patient stratification based on MET alteration status are required to authenticate the effectiveness of these novel combination therapies

Other Cancers

A total of 13 studies demonstrating the clinical outcomes of MET-targeted therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer [61], glioblastoma [62], advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [63], clear-cell sarcoma [64], solid tumors [65–69], and other cancers [70–72] were included in this review (Table 5). In studies with solid tumors, capmatinib (INC280) 100–600 mg BID was used in a dose-escalation cohort [65, 67] and 600 mg BID was used in a dose-expansion cohort [67], whereas the dose of SAR125844 was 570 mg/m2. Only one study reported the clinical evidence for an antibody–drug conjugate in solid tumors: telisotuzumab (ADT 700) 15 mg/kg [66]. Among these studies, the best ORR was 14.3% with SAR125844 in gastric cancers, followed by telisotuzumab (ORR 8.9%) in advanced solid tumors (lung, gastric, esophageal, ovarian, and colorectal cancer) (Table 5). Other studies reported clinical evidence for monotherapy, including INC280 [62], tepotinib [63], and emibetuzumab [71] in glioblastomas and HCC. Decaens et al. [63] reported the efficacy and safety of tepotinib 500 mg OD in a single-arm phase II trial involving patients with MET-amplified HCC who had previously received sorafenib. The authors reported that, irrespective of IHC 2 versus 3+ or in situ hybridization (ISH)-positive versus -negative status, tepotinib resulted in antitumor activity with a median OS of 5.6 months and mPFS in the overall population of 3.4 months (IHC 2+ vs. 3+ mPFS 4.0 vs. 3.2 months: ISH positive vs. negative: PFS 4.2 vs. 3.2 months, respectively) [63].

Ongoing Trials

A robust pipeline of MET inhibitors across multiple tumor types targeting different aspects of the MET signaling pathway is currently being explored and at various phases of clinical development. Table 6 summarizes the various ongoing trials.

Table 6.

Summary of ongoing clinical trials in different cancer types

| Cancer type | Phase | MET alteration type | Study population (n) | MET inhibitor | Clinical trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSCLC | II | MET amp/MET exon 14 SM | 6/25 | Cabozantinib | NCT03911193 |

| II | MET amp | 172a | Osimertinib + savolitinib | NCT03778229 | |

| Ib | MET amp | 23b/135a | Capmatinib ± erlotinib | NCT02468661 | |

| II | MET exon 14 alterations | 20 | Capmatinib | NCT02750215 | |

| II | MET gene mutation/amp | 68b/200a | MGCD265 | NCT02544633 | |

| II | MET exon 14 SM | 12b/25a | Merestinib | NCT02920996 | |

| II | MET amp | 1b/168a | SAR125844 | NCT02435121 | |

| I | MET exon 14 SM/amp | 37b/60a | Bozitinib (PLB1001) | NCT02896231 | |

| I/II | MET exon 14 SM | 68c | Glumetinib | NCT04270591 | |

| II | MET mutation/amp | 68b/200a | MGCD265 | NCT02544633 | |

| I/II | MET amp/mutation | 5770a | Sym015 | NCT02648724 | |

| II | MET expression | 310c | Telisotuzumab vedotin (ABBV-399) | NCT03539536 | |

| I/II | MET-exon14 gene mutation and/or MET gene amp, and/or MET OE | 111c | REGN5093 | NCT04077099 | |

| I | MET amp/mutation | 460c | Amivantamab | NCT02609776 | |

| Solid tumors (advanced/metastatic) | I | MET exon k SM/MET amp/MET fusion | 120c | TPX-0022 | NCT03993873 |

| Solid tumors | I | MET amp | 40b/80a | OMO-1 | NCT03138083 |

| Solid tumors (advanced/metastatic) | II | MET exon k SM/MET amp/OE | 89a | AMG337 | NCT03147976 |

| Solid tumors, lymphomas, or multiple myeloma, including lung cancer | II | MET amp | – | Crizotinib | NCT02465060 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | I/II | MET + | 117b/158a | MSC2156119J | NCT01988493 |

| Metastatic colorectal cancer | II | MET amp | 15a | Savolitinib | NCT03592641 |

| Advanced tumors (NSCLC, head and neck cancer) | I | MET gene mutation/amp | – | Sitravatinib | NCT02219711 |

amp amplification, ID identification, MET mesenchymal-epithelial transition, NCT national clinical trials, NSCLC non-small-cell lung cancer, OE overexpression, SM skipping mutation

aOriginal estimated enrollment

bActual enrollment

cEstimated enrollment

Discussion

The MET pathway plays a remarkable role in the origin of cancer. Therefore, it is logical to consider MET as an actionable target for the treatment of invasive tumors with metastatic potential in different cancer types [3]. Current strategies for MET-targeted therapies include inhibiting kinase activity by preventing the MET-HGF extracellular association with biological antagonists or neutralizing antibodies, preventing the phosphorylation of the kinase domain with the aid of small-molecule inhibitors, and blocking MET signaling through relevant signal transducers [4, 5, 7, 9, 73]. Several trials evaluated the benefits of MET-targeted therapies involving various agents, including anti-MET antibodies (onartuzumab, emibetuzumab) [38, 74], anti-HGF antibodies (ficlatuzumab, rilotumumab) [75], and TKIs (crizotinib, tivantinib, cabozantinib). However, the overall activity of these therapies was low, possibly because of the lack of molecular stratification based on MET genetic status or the use of low MET status thresholds in those trials, diluting individual responses in patients with genetically susceptible tumors [5, 76–78]. Moreover, despite the failure of some clinical trials, investigators have observed certain benefits with MET inhibitors in a selected MET-altered population, which paved the way for investigators to carefully choose biomarkers and thresholds in subsequent trials of MET inhibitors, partially contributing to the success of MET TKIs, such as crizotinib, tepotinib, capmatinib, and savolitinib.

On the path to finding the right biomarkers for MET inhibitors, the first breakthrough was in MET exon 14 skipping mutations. The advent of MET TKIs, specifically crizotinib (PEOFILE 1001) [17], capmatinib (GEOMETRY mono-1) [21], tepotinib (VISION) [19], and savolitinib [79] has changed the therapeutic landscape of NSCLC harboring MET alterations (MET exon 14 skipping mutation), with these agents emerging as a new standard of care with acceptable clinical benefits. Further, in the development of MET-directed EGFR-TKI resistance, the combination of MET TKIs and EGFR TKIs might be beneficial, with existing literature suggesting the same. Trials such as INSIGHT [30] and TATTON [32] evidenced the clinical benefits of tepotinib plus gefitinib and osimertinib plus savolitinib, respectively, in patients with NSCLC. In addition, studies evaluating the clinical benefits in tumors harboring de novo MET amplifications demonstrated acceptable clinical benefits with crizotinib (PROFILE 1001) [42] and capmatinib (GEOMETRY mono-1) [21] in NSCLC and further confirmed that clinical responses were higher in patients with high MET amplification (MET/CEP7 ratios ≥ 5 or GCN ≥ 10), indicating the therapeutic benefits in particular subsets of patients.

In gastric cancers, noteworthy clinical benefits were reported with savolitinib (VIKTORY) [53] and crizotinib (AcSe) [49] specifically in high MET-amplified subsets of patients. On the other hand, multiple studies tested chemotherapy combined with MET inhibitors but had disappointing results [56]. In PRCC, notable clinical benefits were reported with savolitinib (SAVOIR trial) [57] and crizotinib (the EORTC 90101 CREATE trial) [58] in MET-driven disease. Other novel combination therapies are currently being trialed [60].

Most trials across different cancer types have been restricted to either MET amplification or MET overexpression. Accurate patient identification and stratification is critical for the success of MET-targeted therapy in clinical practice [6]. However, the selection of patients with a high likelihood of clinical benefit from MET-targeted therapies has become more ambiguous because of disparities in the criteria for selection of biomarkers [80]. Moreover, the predictive value of MET aberration biomarkers in tumor tissue has not always been consistent. The root for this inconsistency may lie in the diagnostic methods selected for assessment of alterations in tumor tissue [81]. On the other hand, discordance between MET GCN and protein expression requires careful consideration and highlights the challenges of defining molecular inclusion criteria for clinical trials [62].

The use of next-generation sequencing to detect MET alteration has been widely implemented in molecular laboratories, enabling the detection of a wide array of genetic abnormalities (insertions, substitutions, copy number changes, deletions, duplications, chromosome inversions, and chromosome translocations), facilitating the accurate detection of the MET exon 14 splice variant with good sensitivity and specificity [82]. Furthermore, although fluorescence ISH (FISH) was considered the gold standard for the detection of MET amplification, the prevalence of MET amplification detection with FISH is variable across the literature because of a lack of consensus in definitions of MET positivity [83]. IHC offers similar advantages to FISH in the detection of MET amplification, but several studies have reported that IHC was a poor screen for the detection of actionable MET alterations [84].

The current review identified disparities in patient stratification, with studies adopting different cutoff ranges for MET positivity through the use of a range of diagnostic platforms, which may be the reason for non-consensus in the clinical outcomes among studies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic literature review summarizing the published evidence on the clinical outcomes of MET inhibitors in different cancers. However, our review has certain limitations. First, despite a careful electronic search of literature databases, some publications may have been missed. Second, comparatively few RCTs were included in this review.

Conclusion

This review provides an overview of the literature on various MET inhibitors in a range of clinical development phases. MET-selective TKIs (capmatinib, tepotinib, and savolitinib) have become the new standard of care in NSCLC, specifically with MET exon 14 skipping mutations. The combination of MET TKI and EGFR TKI (osimertinib plus savolitinib, tepotinib plus gefitinib) may be a potential solution for MET-driven EGFR TKI resistance. Further, MET alterations may be an actionable target in GC and PRCC. However, most of this evidence is based on phase I and II studies, so phase III studies are warranted to confirm the efficacy and safety of MET inhibitors in various cancers. Furthermore, to avoid disparities in evaluating clinical outcomes, unique biomarkers with accurate diagnostic platforms are much needed in MET-targeted therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Vengal Rao Pachava (PhD) and Dr. Amit Bhat (PhD) (Indegene, Bangalore, India) for providing medical writing support.

Declarations

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Sciences Foundation [81871889 and 82072586 to Z.W., 82102886 to J.X.]; CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences [2021-I2M-1-012 to Z.W]; Beijing Natural Science Foundation [7212084 to Z.W., 7214249 to R.W.]

Conflicts of interest

Yiting Dong, Jiachen Xu, Boyang Sun, Jie Wang, and Zhijie Wang have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of data confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Conception/design: Yiting Dong, Jiachen Xu, Jie Wang, Zhijie Wang. Manuscript writing: Yiting Dong, Jiachen Xu, Boyang Sun, Jie Wang, Zhijie Wang. Critical revision and final approval of manuscript: Jie Wang, Zhijie Wang.

Contributor Information

Jie Wang, Email: Jie_969@163.com.

Zhijie Wang, Email: zlhuxi@163.com.

References

- 1.Yan L, Rosen N, Arteaga C. Targeted cancer therapies. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:1–4. doi: 10.5732/cjc.010.10553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ke X. Molecular targeted therapy of cancer: the progress and future prospect. Front Lab Med. 2017;1:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Bono JS, Yap TA. c-MET: an exciting new target for anticancer therapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2011;3:S3–5. doi: 10.1177/1758834011423402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koch JP, Aebersold DM, Zimmer Y, Medová M. MET targeting: time for a rematch. Oncogene. 2020;39:2845–2862. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-1193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comoglio PM, Trusolino L, Boccaccio C. Known and novel roles of the MET oncogene in cancer: a coherent approach to targeted therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:341–358. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garajova I, Giovannetti E, Biasco G, Peters GJ. c-Met as a target for personalized therapy. Transl Oncogenom. 2015;Suppl. 1:13–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Boccaccio C, Comoglio PM. MET, a driver of invasive growth and cancer clonal evolution under therapeutic pressure. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;31:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puccini A, Marín-Ramos NI, Bergamo F, Schirripa M, Lonardi S, Lenz H-J, et al. Safety and tolerability of c-MET inhibitors in cancer. Drug Saf. 2019;42:211–233. doi: 10.1007/s40264-018-0780-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Recondo G, Che J, Jänne PA, Awad MM. Targeting MET dysregulation in cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:922–934. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.FDA Approves First Targeted Therapy to Treat Aggressive Form of Lung Cancer. [cited 2021 Mar 10]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-targeted-therapy-treat-aggressive-form-lung-cancer#:~:text=FDA%20Approves%20First%20Targeted%20Therapy%20to%20Treat%20Aggressive%20Form%20of%20Lung%20Cancer,-Share&text=Today%2C%20the%20U.S.%20Food%20and,other%20parts%20of%20the%20body.

- 11.TEPMETKO (Tepotinib) Approved in Japan for Advanced NSCLC with METex14 Skipping Alterations. [cited 2021 Mar 10]. Available from: https://www.merckgroup.com/en/news/tepotinib-25-03-2020.html.

- 12.Chi-Med’s NDA for Savolitinib in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Granted Priority Review in China. Available from: https://www.hutch-med.com/nda-for-savolitinib-in-nsclc-granted-priority-review-in-china/#:~:text=Hong%20Kong%2C%20Shanghai%20%26%20Florham%20Park,for%20the%20treatment%20of%20non%2D.

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, for the PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Awad MM, Oxnard GR, Jackman DM, Savukoski DO, Hall D, Shivdasani P, et al. MET Exon 14 mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer are associated with advanced age and stage-dependent MET genomic amplification and c-Met overexpression. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2016;34:721–730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong JH, Yeung SF, Chan AWH, Chung LY, Chau SL, Lung RWM, et al. MET amplification and exon 14 splice site mutation define unique molecular subgroups of non-small cell lung carcinoma with poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2016;22:3048–3056. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahu A, Prabhash K, Noronha V, Joshi A, Desai S. Crizotinib: a comprehensive review. South Asian J Cancer. 2013;2:91–97. doi: 10.4103/2278-330X.110506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drilon A, Clark JW, Weiss J, Ou S-HI, Camidge DR, Solomon BJ, et al. Antitumor activity of crizotinib in lung cancers harboring a MET exon 14 alteration. Nat Med. 2020;26:47–51. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0716-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tepotinib. https://ncit.nci.nih.gov/ncitbrowser/ConceptReport.jsp?dictionary=NCI_Thesaurus&ns=NCI_Thesaurus&code=C88314.

- 19.Paik PK, Felip E, Veillon R, Sakai H, Cortot AB, Garassino MC, et al. Tepotinib in non-small-cell lung cancer with MET exon 14 skipping mutations. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:931–943. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vansteenkiste JF. Capmatinib for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2019;19:659–671. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2019.1643239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf J, Seto T, Han J-Y, Reguart N, Garon EB, Groen HJM, et al. Capmatinib in MET exon 14-mutated or MET-amplified non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:944–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savolitinib. https://ncit.nci.nih.gov/ncitbrowser/ConceptReport.jsp?dictionary=NCI_Thesaurus&ns=NCI_Thesaurus&code=C104732.

- 23.Lu S, Fang J, Li X, Cao L, Zhou J, Guo Q, et al. Once-daily savolitinib in Chinese patients with pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas and other non-small-cell lung cancers harbouring MET exon 14 skipping alterations: a multicentre, single-arm, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;10:1154–1164. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo A, Villén J, Kornhauser J, Lee KA, Stokes MP, Rikova K, et al. Signaling networks assembled by oncogenic EGFR and c-Met. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:692–697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707270105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dulak AM, Gubish CT, Stabile LP, Henry C, Siegfried JM. HGF-independent potentiation of EGFR action by c-Met. Oncogene. 2011;30:3625–3635. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bean J, Brennan C, Shih J-Y, Riely G, Viale A, Wang L, et al. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20932–20937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710370104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papadimitrakopoulou V. Analysis of resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in patients with EGFR T790M advanced NSCLC from the AURA3 study. Annals of Oncology. 2018;29(supp8):741. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasquini G, Giaccone G. C-MET inhibitors for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2018;27:363–375. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2018.1462336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giaccone G. The role of gefitinib in lung cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2004;10:4233s–4237s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-040005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y-L, Cheng Y, Zhou J, Lu S, Zhang Y, Zhao J, et al. Tepotinib plus gefitinib in patients with EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer with MET overexpression or MET amplification and acquired resistance to previous EGFR inhibitor (INSIGHT study): an open-label, phase 1b/2, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet Respir Med [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 27]. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2213260020301545. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Zhang H. Osimertinib making a breakthrough in lung cancer targeted therapy. OncoTargets Ther. 2016;9:5489–5493. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S114722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sequist LV, Han J-Y, Ahn M-J, Cho BC, Yu H, Kim S-W, et al. Osimertinib plus savolitinib in patients with EGFR mutation-positive, MET-amplified, non-small-cell lung cancer after progression on EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors: interim results from a multicentre, open-label, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:373–386. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Y-L, Zhang L, Kim D-W, Liu X, Lee DH, Yang JC-H, et al. Phase Ib/II study of capmatinib (INC280) plus gefitinib after failure of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor therapy in patients with EGFR-mutated, MET factor-dysregulated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2018;36:3101–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Wu Y-L, Kim D-W, Felip E, Zhang L, Liu X, Zhou CC, et al. Phase (Ph) II safety and efficacy results of a single-arm ph ib/II study of capmatinib (INC280) + gefitinib in patients (pts) with EGFR-mutated (mut), cMET-positive (cMET+) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:9020–9020. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Camidge DR, Barlesi F, Goldman J, Morgensztern D, Heist R, Vokes E, et al. EGFR M+ subgroup of phase 1b study of telisotuzumab vedotin (Teliso-V) plus erlotinib in c-Met+ non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:S305–S306. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Camidge DR, Barlesi F, Goldman JW, Morgensztern D, Heist RS, Vokes EE, et al. Results of the phase 1b study of ABBV-399 (telisotuzumab vedotin; teliso-v) in combination with erlotinib in patients with c-Met+ non-small cell lung cancer by EGFR mutation status. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:3011–3011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J, Fang J, Shu Y, Chang J, Chen G, He J, et al. A phase Ib trial of savolitinib plus gefitinib for chinese patients with EGFR-mutant MET-amplified advanced NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:S1769. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishio M, Horiike A, Nokihara H, Horinouchi H, Nakamichi S, Wakui H, et al. Phase I study of the anti-MET antibody onartuzumab in patients with solid tumors and MET-positive lung cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2015;33:632–640. doi: 10.1007/s10637-015-0227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCoach CE, Yu A, Gandara DR, Riess J, Li T, Lara P, et al. Phase I study of INC280 plus erlotinib in patients with MET expressing adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2587–2587. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camidge DR, Moran T, Demedts I, Grosch H, Di Mercurio J-P, Mileham KF, et al. A randomized, open-label, phase 2 study of emibetuzumab plus erlotinib (LY+E) and emibetuzumab monotherapy (LY) in patients with acquired resistance to erlotinib and MET diagnostic positive (MET Dx+) metastatic NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:9070–9070. [Google Scholar]