Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is associated with autoimmunity and systemic inflammation. Patients with autoimmune rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease (RMD) may be at high risk for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. In this review, based on evidence from the literature, as well as international scientific recommendations, we review the relationships between COVID-19, autoimmunity and patients with autoimmune RMDs, as well as the basics of a multisystemic inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19. We discuss the repurposing of pharmaceutics used to treat RMDs, the principles for the treatment of patients with autoimmune RMDs during the pandemic and the main aspects of vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in autoimmune RMD patients.

Key words: Autoimmunity, COVID-19, drug repurposing, multisystemic inflammatory syndrome, rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases, SARS-CoV-2, vaccination

Introduction

Since the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, we have learned a lot about the development, clinical signs and symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, course and outcome of the disease (Refs 1, 2). The course of COVID-19 includes multiple stages, which also determines the indicated treatment strategy (Refs 1–3). Stage 1 is the period of early viral infection with fever, respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms and lymphopenia. Stage 2 is the pulmonary phase. It is divided into two substages: the non-hypoxemic Stage 2a and the hypoxemic Stage 2b. Finally, Stage 3 is the phase of a multisystemic inflammatory syndrome (MIS), occasionally accompanied by the cytokine storm as a pathogenetic feature (Refs 1–3). It is important to note that a real ‘cytokine storm’ occurs in only 2% of patients and in 8–11% of severe patients (Ref. 4). This late stage of COVID-19 also involves, among other mechanisms, bradykinin storm (Ref. 5), the activation of coagulation and complement cascades (Ref. 6), endotheliitis, vascular leak and oedema (Ref. 6), microthrombotic events (Ref. 4) and neutrophil extracellular traps (NET) (Ref. 7). As these anti-inflammatory agents are most effective during MIS, this should be confirmed by clinical, imaging and laboratory markers (Refs 1, 8–10). Laboratory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein, ferritin, D-dimer, cardiac troponin (cTn), NT-proBNP, lymphopenia, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and, if available, circulating interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels have been associated with MIS in Stages 2b-3 and also with the outcome of COVID-19 (Refs 9–11).

As rheumatologists and immunologists, we encounter a number of important issues with special relevance for autoimmunity, as well as rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMD). There may be multiple interactions between COVID-19, autoimmunity, systemic inflammation and RMDs. (1) COVID-19 may increase the risk of autoantibody production and autoimmunity (Ref. 12). (2) Autoimmune-inflammatory RMDs may increase susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (Ref. 13). (3) It is now clear that in the more advanced stages of COVID-19, systemic inflammation and MIS rather than the original viral infection may dominate the clinical picture (Refs 3, 8, 9, 14–16). (4) As a consequence of the above, immunosuppressive drugs successfully used for the treatment of RMDs, such as corticosteroids, biologics or Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors may also be applied to patients with severe COVID-19 and systemic inflammation (drug repurposing) (Refs 17–19). (5) It is also crucial how to manage patients with autoimmune RMDs during COVID-19 (Refs 20–23). (6) Vaccination of RMD patients against SARS-CoV-2 is also a fundamental issue (Refs 24, 25). Here we will briefly discuss all of these issues associated with autoimmunity, MIS and RMD patients.

SARS-CoV-2 infection, autoimmunity and autoimmune diseases

The development of autoimmunity has been previously described in connection with viral infections other than SARS-CoV-2, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), parvovirus B19, hepatitis B (HBV) and C viruses (HCV) (Refs 12, 26–28). Regarding the pathogenesis of autoimmune reactions, at least 30 epitopes (hexapeptides) have been described within both the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein and proteins in human organs allowing the development of autoimmunity through cross-reactivity including molecular mimicry and/or bystander activation. These proteins include ribosomal proteins, methyltransferases, cytokines, such as interleukin 7 (IL-7), as well as lysosomal, sodium channel, cell adhesion, myosin proteins and others (Ref. 12). This molecular cross-reactivity results in the production of numerous autoantibodies described later, as well as the activation of autoreactive T-cells (Refs 26, 27). In addition, epitope spreading, and the presentation of hidden antigens also emerge as mechanisms (Refs 12, 26, 27). Autoimmune phenomena based on cross-reactivity have already been described in the previous two major coronavirus epidemics, SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV (Refs 27–29). Peptides found in some proteins of SARS-CoV-2 may also cross-react with peptides of the lung alveolar surfactant protein (Ref. 30). As presented later, such molecular mimicry may also play a role in the development of paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome (PIMS) (Refs 16, 31). In addition, the described hexapeptide cross-reactivities discovered may play a role in the clinical symptoms associated with COVID-19. For example, one of histone lysine methyltransferases may play a role in neurodevelopmental disorders, convulsions and behavioural disorders (Ref. 32), while IL-7 plays a central role in immune regulation and its absence leads to severe lymphopenia (Ref. 33). Neuropsychiatric abnormalities and lymphopenia are relatively commonly associated with COVID-19 (Refs 15, 28). In paediatric MIS discussed later, at least six protein epitopes of the SARS-CoV-2 virus cross-react with the inositol triphosphate 3 kinase C (ITPKC) Kawasaki antigen, suggesting a role for molecular mimicry in the development of this disease (Ref. 31).

As for COVID-19, inflammation during the course of the disease, MIS, as well as clinical and radiological phenomena suggest that acute autoimmune and autoinflammatory mechanisms are triggered by viral infection (Refs 34, 35). SARS-CoV-2-induced lung injury (ARDS) is in many respects similar to the acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease (ILD) associated with autoimmune diseases (Ref. 35). In another study, autoantibodies were detected in 20–50% of pneumonia patients associated with COVID-19 (Ref. 36).

The number of identified autoantibodies associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection is now more than 20. Primarily antinuclear antibody (ANA) and antibodies against elements of the coagulation cascade, such as antiphospholipid (APLA), anti-prothrombin and anti-heparin antibodies have been described. However, anti-citrullinated protein (ACPA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antigen (ANCA), anti-SS-A/Ro antibodies and rheumatoid factor production has also been described with SARS-CoV-2 infection (Refs 12, 36–38).

Some studies have also analysed histological changes induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Tissue samples obtained from autopsies of a total of 18 patients who died of COVID-19 showed marked infiltration of T-cells and various T-cell subclasses in the lungs. There have been small cellular infiltrates in the kidney, liver, intestinal wall and pericardium. The dominant cell type was the CD8 + T lymphocyte (Ref. 39).

Regarding clinical autoimmune syndromes, mainly involvement of the nervous system, such as Guillain-Barré and Miller-Fisher syndrome, as well as immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) have been described, but systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or Kawasaki disease (KD) may also occur (Ref. 12). Thromboembolic complications including deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremity, pulmonary embolism or stroke have been reported in association with severe COVID-19 (Ref. 4). These events may be associated with the autoantibodies described above. For example, while the majority of thromboembolic events occurred in older patients, stroke was also observed in younger patients of 30–50 years of age. The latter may be explained by APLAs (Ref. 40). Indeed, APLAs have been detected in patients with severe thromboembolic COVID-19 (Refs 40, 41). In one study, lupus anticoagulant positivity was found in 45% of 56 COVID-19 patients (Ref. 42), compared with 85% in those admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) due to ARDS (Ref. 43). Lupus anticoagulant correlated with thrombotic events and D-dimer levels (Ref. 43). The predominant APLA isotype was IgA (Ref. 40). We have detected IgA APLA in patients with the acute coronary syndrome (Ref. 44). Thus, SARS-CoV-2 infection is likely to lead to an IgA-type immune response leading to mucosal damage (Refs 12, 36). Based on these results, the SARS-CoV-2 virus can induce APLA, which has also been described for other viruses, such as EBV, CMV and HCV (Ref. 12). It should be noted that APLA production does not always lead to thrombotic events or miscarriages and the occurrence of classical antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) after SARS-CoV-2 infection is rare (Ref. 12). Therefore, the pathogenetic role of APLA in these events remains to be elucidated (Refs 12, 45). Fibromyalgia symptoms may also worsen during COVID-19 (Ref. 46).

The risk and outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection in adult and paediatric RMD patients

Autoimmune RMDs with high inflammatory activity may increase susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection and worsen the outcome of COVID-19 (Ref. 13). According to the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance (C19-GRA) registry, age, previous corticosteroid use and comorbidities of RMD patients are considered to be poor prognostic factors for the development and course of COVID-19. In turn, tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor biologics, especially in monotherapy, have been associated with better COVID-19 outcomes (Ref. 20).

A recent meta-analysis determined the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in RMD patients and the factors influencing this risk. A total of 62 publications were suitable for assessing the prevalence, while 65 papers discussed the outcome of COVID-19 in RMDs. The survey included patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), SLE, systemic sclerosis (SSc), spondylarthritis (SpA), Sjögren's syndrome (SS), idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) and systemic vasculitis. Based on the results of 62 observational studies, a total of 878 cases of COVID-19 were found in 319 025 patients. Thus, in general, the prevalence of COVID-19 was 0.011 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.005–0.025]. The highest prevalence was observed in SLE, SSc and SS, where long-term corticosteroid use may also have played a role. Based on seven case-control studies, the risk of COVID-19 in RMD patients was 2.19-fold (95% CI: 1.05–4.58) higher than in the general population (P = 0.038). Based on regression analysis, long-term corticosteroid use was an independent factor for the development of COVID-19. In this study, age, gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus or the use of conventional synthetic (csDMARD), biologic (bDMARD) and targeted synthetic disease-modifying drugs (tsDMARD) were not associated with the risk of COVID-19 (Ref. 13).

The same group also investigated the clinical outcome of COVID-19 and its determinants. Data from 2766 patients with COVID-19 were reviewed in a total of 65 observational studies. The mean hospitalisation rate was 0.35 (95% CI: 0.23–0.50). The highest demand of hospitalisation was observed in RA and SpA. The COVID-19 mortality in RMD patients was 0.066 (95% CI: 0.036–0.120). Again, mortality in RA and SpA was higher compared to non-RMD patients or healthy individuals in part due to age and comorbidities. Age over 63 years, male gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and obesity were associated with a need for hospitalisation, intensive care and mortality. Regarding medication, previous long-term corticosteroid treatment, csDMARD use, as well as b/tsDMARD + csDMARD combination therapy, especially rituximab, negatively affected clinical outcome compared to b/tsDMARD monotherapy. In particular, there was a reduction in hospitalisation and mortality using anti-TNF monotherapy (Ref. 13). Some reports also suggest that sulfasalazine, abatacept and JAK inhibitors might also worsen COVID-19 outcomes, however, this needs to be confirmed in larger cohorts (Refs 47, 48).

In a retrospective study carried out in Spain, patients with chronic inflammatory diseases had a 1.3-fold higher prevalence of hospital COVID-19 compared to the reference population. Patients receiving tsDMARDs or bDMARDs but not those on csDMARDs had a greater prevalence (Ref. 49). In the same cohort, severe COVID-19 was associated with autoimmune RMDs but not with inflammatory arthritis or immunosuppressive therapies (Ref. 50).

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, it seemed that the disease rarely affected children and if so, the course of the disease was still generally mild. Later, with the spread of new variants, paediatric COVID-19 became more common, and some severe cases were reported. COVID-19-associated paediatric MIS, in many ways similar to the classical KD, has been described in 6–9-year-old children. Clinical symptoms include fever, abdominal pain, mucosal signs, rash, lymph node swelling, hepatosplenomegaly, neurological symptoms and oedema of the hands and feet (Refs 16, 51). This condition was first termed hyperinflammation syndrome (HIS) but later the term PIMS was introduced and is still used today (Refs 9, 16, 51). The disease is also characterised by high CRP, ferritin and D-dimer levels. In rare, severe cases, it may also meet the criteria for macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) with pancytopenia and extremely high ferritin (Refs 16, 51). PIMS is similar to KD but also differs in many respects: it affects a wider age group, neurological, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal symptoms are more common, while CRP, platelet and lymphocyte counts are lower than in KD (Refs 16, 51). KD is more prevalent in infants, while PIMS is more common in 9–14-year-olds (Refs 16, 51). Cases of similar KD-like diseases have been reported in adults (Ref. 52). Seropositivity for IgG-type anti-SARS-CoV-2 is not detected in the majority of patients (Ref. 16).

Based on all this, the overall risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with autoimmune RMDs may be higher. The underlying RMD itself is unlikely to result in a higher need for hospitalisation and mortality. However, the outcome of COVID-19 in RMD patients may be associated with prior drug therapy (Ref. 13). It is of note that the possible harmful effects of previous long-term corticosteroid treatment on the outcome of COVID-19 do not contradict the indication of glucocorticoids in COVID-19-associated MIS (Refs 8, 17).

Repurposing of antirheumatic drugs for the treatment of severe COVID-19

We discussed the different stages of COVID-19 above (Refs 1–3). Patients in Stage 1 with early viraemia and mild symptoms should be treated with antiviral drugs, both small molecules or therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. We will not discuss these agents in the present review. Antirheumatic and anti-inflammatory drugs used in the treatment of RMDs may include corticosteroids, bDMARD and tsDMARDs. These compounds are also used in Stages 2b and 3 of COVID-19 (Refs 3, 14, 17).

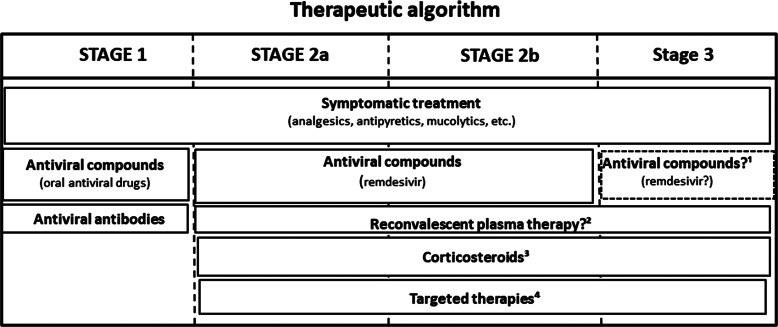

Antirheumatic drugs currently used to treat COVID-19 are listed in Table 1 and the use of different treatments in various stages of COVID-19 is shown in Figure 1. Of note, relatively few high-value, hard endpoint (mortality, hospitalisation), randomised, controlled trials (RCT) have been performed. In most cases, uncontrolled or minor studies are available, with a few exceptions (e.g., the RECOVERY trials). However, emergency use authorisation (EUA) has been donated to some of these agents due to urgency. First, some information on these anti-inflammatory agents will be discussed followed by the latest recommendations of the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR).

Table 1.

Antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive agents repurposed for the treatment of COVID-19 (Ref. 3)

| Compound | Dosing | COVID-19 stage | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone | 6 mg od PO/IV for <10 days | 2b-3 | |

| Methylprednisolone | 32 mg od PO for 10 days or 250 mg IV on day 1, 80 mg IV on days 2–5 or 0.5–1 mg/kg/day for up to 7 days |

2b-3 | |

| Tocilizumab | 8 mg/kg (up to 800 mg) IV once, may be repeated once within 24 h | 2b-3 | MIS, non-response to corticosteroids, in combination with corticosteroids |

| Baricitinib | 4 mg od PO for 7–28 days | 2b-3 | MIS, non-response to corticosteroids, in combination with corticosteroids and remdesivir |

| Anakinra | 100 mg SC tid or qid for up to 15 days | 2b-3 | MIS, non-response to corticosteroids, in combination with corticosteroids |

| Sarilumab | 200–400 mg IV once, may be repeated once within 24 h | 2b-3 | MIS, non-response to corticosteroids, in combination with corticosteroids, if tocilizumab is not available |

| Tofacitinib | 5 mg bid or 11 mg od PO for 7–28 days | 2b-3 | MIS, non-response to corticosteroids, in combination with corticosteroids, if baricitinib is not available |

| hIVIG | 0.5–1 g/kg/day IV/SC for 5 days | 3 | in refractory cases (paediatric MIS, immunodeficiency) |

bid, twice daily; hIVIG, human high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin; IV, intravenous; MIS, multisystemic inflammatory syndrome; od, once daily; PO, per os; qid; four times daily; SC, subcutaneously; tid, three times daily.

Fig. 1.

The use of anti-COVID-19 therapies at different stages of the disease. Explanations: 1: in stage 3, remdesivir may be used in combination with baricitinib; 2: reconvalescent plasma therapy may be used in immunosuppressed states, as well as in sustained viraemia; 3: corticosteroids might be used in hypoxia and/or MIS; 4Targeted therapies should be applied in MIS. See Table 1 for more details.

Corticosteroids, as discussed above, are not recommended in the early stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection as, in retrospective studies in autoimmune RMD patients, previous long-term corticosteroid treatment was associated with increased susceptibility to COVID-19 and disease severity (Ref. 13). However, in more severe cases of COVID-19 with MIS and organ damage (Stages 2b-3), dexamethasone significantly reduced 28-day mortality. Efficacy was better in those in need for invasive ventilation in the ICU (Ref. 53). Hospital mortality and clinical outcome were also improved by methylprednisolone in a study conducted by the EULAR working group, particularly in those with marked elevations in CRP, D-dimer and ferritin (Ref. 54). Dexamethasone has received FDA EUA approval (Ref. 55) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

The IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) inhibitor tocilizumab has been effective in several RCTs in patients in Stages 2b-3 (Refs 56–58). In these studies, tocilizumab was effective in Stages 2b-3 in severe cases requiring ICU admission and ventilation. In these patients, tocilizumab improved survival and the chance of hospital discharge (Refs 56–58). In the REMAP-CAP study, tocilizumab was so effective within two days of ICU referral that the study was prematurely terminated (Ref. 57). In the CHIC study conducted by EULAR, tocilizumab in combination with corticosteroid improved the clinical picture and survival in patients initially treated with corticosteroids only but who did not show adequate response (Ref. 54). Finally, the largest COVID-19 therapeutic study to date (RECOVERY; 4116 patients) included patients requiring invasive ventilation, non-invasive oxygen therapy or none of these (control group). At baseline, 82% of the patients received corticosteroids. In hypoxic, Stage 2b-3 patients requiring hospitalisation, tocilizumab in comparison to standard care significantly reduced invasive mechanical ventilation or mortality (35 vs 42%) and improved the chance of hospital discharge within 28 days (57 vs 50%). Tocilizumab also decreased the need for invasive ventilation (Ref. 58) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

On the other hand, tocilizumab was not effective in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 not requiring ICU admission (Refs 59, 60). Thus, tocilizumab is recommended in patients with MIS who do not respond to corticosteroids (Refs 54, 57, 58) but not in the early stages of COVID-19 nor in the absence of significant inflammation (Refs 59, 60). It should also be noted that tocilizumab transiently increases circulating IL-6 levels (due to the competitive binding to the IL-6 receptor), therefore, determination of serum IL-6 concentration is only recommended at baseline, before the initiation of treatment (Ref. 61).

Another IL-6 receptor inhibitor, sarilumab, also improved the survival of patients with severe COVID-19 (REMAP-CAP trial). Sarilumab also increased the probability of ICU and hospital discharge (Ref. 57). In contrast, in a smaller study (SARI-RAF), no clinical improvement or longer survival was observed in patients with pneumonia who did not require invasive ventilation (Ref. 62) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Among the JAK inhibitors, baricitinib has antiviral effects by blocking viral entry through ACE2 into the cell (Ref. 63). Baricitinib also exerts anti-inflammatory effects leading to the reduction of MIS and restoration of immune regulation (Refs 63, 64). Baricitinib in combination with remdesivir significantly improved clinical status and reduced time to recovery in severe COVID-19 patients requiring respiratory therapy (Stages 2b-3). On the other hand, baricitinib was not effective in mild to moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection (Ref. 65). FDA approved the use of the baricitinib-remdesivir combination in severe COVID-19 (Ref. 66) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Another JAK inhibitor, tofacitinib was also effective in the STOP-COVID trial. Hospitalised adults with COVID-19 pneumonia received either tofacitinib 10 mg bid or placebo bid for up to 14 days or until hospital discharge. In this patient population, tofacitinib treatment led to a lower risk of death or respiratory failure through day 28 in comparison to placebo (Ref. 67) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

The role of autoinflammation including NLRP3 inflammasome activation, as well as IL-1β and IL-18 production has also been demonstrated in COVID-19. The IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) anakinra improved survival in patients with Stage 2b-3 COVID-19 (Refs 68–70). In contrast, anakinra was not effective in patients with hypoxia not requiring ventilation (Ref. 71). Early increase of plasma soluble urokinase activator receptor (sUPAR) levels has been associated with increased risk of COVID-19 progression. Interestingly, anakinra was particularly effective in patients with high plasma sUPAR (Ref. 72). The use of anakinra is also relevant in PIMS (Refs 16, 73) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

There have been very few studies on the use of high-dose human intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in COVID-19. In a controlled study of 59 patients, IVIG resulted in clinical improvement after initial treatment failure (Ref. 74). However, in a similarly designed RCT, IVIG in combination with other antiviral agents was ineffective (Ref. 75). In the recent ICAR RCT, IVIG was tried in patients with COVID-19 who received invasive mechanical ventilation for moderate-to-severe ARDS. In these patients, IVIG did not improve clinical outcomes at day 28 (Ref. 76). The effect of IVIG on earlier disease stages of COVID-19 is currently being assessed (Ref. 77). IVIG may also be administered to children with KD (Ref. 16), as well as to RMD patients with immunodeficiency (Ref. 3).

Several other compounds used for the treatment of RMDs have been tested in mostly small COVID-19 studies. In summary, antimalarials including chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, as well as colchicine, leflunomide or cyclosporine A are not recommended due to controversial study results, a lack of real evidence or side effects (Refs 3, 17, 78).

Management of patients with autoimmune RMDs during the pandemic

With respect to autoimmune RMD patients, the main issue is their management including the use of immunosuppressive agents during the COVID-19 pandemic. As discussed above, these patients are at high risk of developing COVID-19 (Refs 12, 13). The management of already SARS-CoV-2-infected and not infected RMD patients are highly different (Refs 20, 79).

Regarding immunosuppressive treatment of autoimmune RMD patients, previous long-term corticosteroid therapy was associated with a more severe outcome of COVID-19, while anti-TNF bDMARDs tended to improve it (Ref. 13). We have less data on non-TNF bDMARDs and tsDMARDs (Refs 20, 79). In general, the activity of the underlying disease may confer more risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection than csDMARDs, bDMARDs or tsDMARDs (Refs 12, 19, 20, 79, 80). In RA, increased inflammatory activity increases the risk of severe infections and the infection itself may cause an exacerbation of the underlying disease (Refs 19, 80, 81). Thereafter, disease activity and infection can create a vicious cycle (Ref. 19).

Autoimmune RMDs may flare up without treatment or after reducing the dose leading to an increased risk of infection (Refs 19, 80, 81). Therefore, it is not recommended to discontinue immunosuppressive therapy, reduce its dose or increase treatment intervals. In an uninfected, stable RMD patient, the continuation of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, csDMARDs, bDMARDs and tsDMARDs in effective doses is recommended (Refs 19, 20, 79, 80). ACR also recommends that low-dose corticosteroids (≤10 mg prednisolone equivalent) should be initiated if necessary and continued at the lowest possible dose. In severe, life-threatening RMD, such as lupus nephritis or active systemic vasculitis, high-dose corticosteroid therapy is recommended (Ref. 79). Abrupt discontinuation of corticosteroids is not recommended even in the setting of severe infection (Refs 19, 79). There is also no contraindication to re-initiate targeted therapy if justified by disease activity (Refs 19, 20, 79, 80). Only febrile, acute COVID-19 may be an indication for discontinuation of csDMARDs, bDMARDs and tsDMARDs (Refs 19, 20, 79, 80). As discussed above, some bDMARD and tsDMARD agents have been introduced to the therapy of Stage 2b-3 COVID-19 with MIS through repurposing (Refs 14, 17). However, it still needs individual decision to continue tocilizumab or tsDMARDs in SARS-CoV-2-infected RMD patients (Refs 20, 79).

With respect of SARS-CoV-2-infected autoimmune RMD patients, according to the latest ACR recommendations, NSAIDs and sulfasalazine can be continued. DMARDs, with the exception of IL-6 inhibitors, should be temporarily suspended and restarted after 2 weeks of asymptomatic observation. In individual cases, anti-IL-6 receptor therapy may be used in agreement with the patient. In documented COVID-19 disease, regardless of disease severity, all DMARDs should be temporarily discontinued. However, suspension of corticosteroids is not recommended. In mild cases of COVID-19 with no or mild pneumonia requiring outpatient treatment and home quarantine, immunosuppressive agents may be restarted within 7–14 days of asymptomatic disease. Continuation of treatment after severe COVID-19 should be considered on an individual basis (Ref. 79).

EULAR has initiated a COVID-19 registry and issues a new report regularly (Ref. 82). As of October 2021, the database includes more than 10 300 patients. Two-third of patients are women, with a median age of 55 (Refs 43–66) years. Altogether 4% of patients are under 18 years of age and 36% are over 60 years of age. The most common diagnoses are RA (38%), axial or peripheral SpA (16%), PsA (13%) and SLE (6%). About 27% of patients required hospital care. Eighty-one % of patients received DMARDs, of which 45% received targeted therapies (Ref. 82).

Finally, In the Spanish COVIDSER study that include 7782 RMD patients, the use of TNF inhibitors was associated with decreased, while that of rituximab was associated with increased risk of hospitalisation. Yet, in this study, the use of bDMARDs was not associated with COVID-19 severity (Ref. 83).

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination of autoimmune RMD patients

EULAR recommends that all autoimmune RMD patients should be vaccinated against COVID-19. The same is true for patients taking corticosteroids, MTX, bDMARDs or tsDMARDs. For B-cell depleting agents, such as rituximab, vaccination should be performed at least 3 months after the administration of this bDMARD (Ref. 25). ACR emphasises that the rheumatologist should monitor the patient's vaccination status and discuss the details of the vaccination. Factors related to the underlying disease, treatment, age, gender should be considered as they may affect the success of vaccination. In principle, patients with autoimmune RMDs should be prioritised for vaccination over the general population because of their increased risk of infection. Exacerbation of the underlying RMD after vaccination is extremely rare and the benefits of vaccination far outweigh the risks. Regarding vaccination practice, ACR points out that none of the FDA-approved vaccines is preferred; the first and second doses of the same vaccine should be administered unless contraindicated; routine laboratory testing, including anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing, before and after vaccination is not recommended; epidemiological regulations must be followed even after the full vaccination course; vaccination of people living together with the RMD patient is also recommended in order to protect the patient; and vaccination should be conducted as soon as possible, regardless of the severity of the underlying RMD, except in the severe conditions when the patient is in the ICU (Ref. 24).

In a recent multicentre observational study, the immunogenicity of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine including seropositivity rates and serum anti-S protein titres has been evaluated in autoimmune RMD patients. RA, axSpA, PsA, SLE and large-vessel vasculitis patients exerted seropositivity rates between 82.1 and 96.9% compared to controls (100%). On the other hand, patients with IIM and ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) had seropositivity rates of 36.8 and 30.8%, respectively. Similarly, patients excluding IIM and AAV had serum anti-S titres of 108.7–173.1 AU/ml compared to controls (218.6 AU/ml). Anti-S titres of IIM and AAV patients were only 42.9 and 40.3 AU/ml, respectively (Ref. 84).

Regarding vaccination of RMD patients taking immunosuppressive drugs, in the multicentre trial described above, corticosteroids, rituximab, abatacept belimumab and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) in monotherapy or in combination exerted significantly lower seropositivity rates (36–77%) compared to controls. On the other hand, seropositivity rates were acceptable (84–100%) in RMD patients receiving MTX, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), leflunomide, as well as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17 and JAK inhibitors (Ref. 84). In this regard, there is some inconsistency between ACR (Ref. 24) and EULAR recommendations (Ref. 25). ACR does not suggest any changes in the doses or timing of corticosteroids, antimalarials, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, MMF, azathioprine, oral cyclophosphamide (CYC) and bDMARDs. However, by referring to some previous studies, ACR suggests a 2–4-week break in MTX and tsDMARDs after vaccination. ACR also suggests a break after vaccination for abatacept (1 week), intravenous CYC (1 week) and rituximab (2–4 weeks) (Ref. 24). In contrast, EULAR recommends transient suspension for rituximab only (Ref. 25). As far as MTX is concerned, it has indeed been suggested in the past in relation to other vaccines (e.g. influenza) that vaccination may be more effective if MTX administration is suspended (Ref. 85). However, a more recent study has suggested that even a single dose of mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 is effective without temporary suspension of MTX therapy (Ref. 86). In the latter study, antibody responses to the mRNA vaccine were also acceptable in RMD patients receiving other bDMARDs and tsDMARDs with the exception of rituximab (Ref. 86). In addition, neither MTX nor bDMARDs affected the humoral and cellular immune responses to mRNA vaccines (Refs 87–89). In a recent study using questionnaires, up to 28% of immunosuppressive medications had to be modified around the time of anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. More modifications had to be carried out after the second compared to the first dose. A number of drug modifications were not consistent with recommendations (Ref. 90).

In conclusion, COVID-19 and autoimmune RMDs may have several links. Patients with autoimmune RMD might have increased susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. The SARS-CoV-2 virus might trigger autoimmunity. Immunosuppressive agents have been introduced to the treatment of MIS associated with COVID-19. Finally, patient care and vaccination of autoimmune RMD patients need special attention during the pandemic.

References

- 1.Gandhi RT, Lynch JB and Del Rio C (2020) Mild or moderate COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine 383, 1757–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siddiqi HK and Mehra MR (2020) COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: a clinical-therapeutic staging proposal. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 39, 405–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szekanecz Z et al. (2021) Antiviral and anti-inflammatory therapies in COVID-19. Hung Med J (Orvosi Hetilap) 162, 643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merrill JT et al. (2020) Emerging evidence of a COVID-19 thrombotic syndrome has treatment implications. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 16, 581–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garvin MR et al. (2020) A mechanistic model and therapeutic interventions for COVID-19 involving a RAS-mediated bradykinin storm. eLife 9, e59177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ackermann M et al. (2020) Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine 383, 120–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borges L et al. (2020) COVID-19 and neutrophils: the relationship between hyperinflammation and neutrophil extracellular traps. Mediators of Inflammation, 8829674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu B, Huang S and Yin L (2020) The cytokine storm and COVID-19. Journal of Medical Virology, 250–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webb BJ et al. (2020) Clinical criteria for COVID-19-associated hyperinflammatory syndrome: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol, e754–e763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caricchio R et al. (2020) Preliminary predictive criteria for COVID-19 cytokine storm. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karimi A et al. (2021) Novel systemic inflammation markers to predict COVID-19 prognosis. Frontiers in Immunology 12, 741061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrenfeld M et al. (2020) COVID-19 and autoimmunity. Autoimmunity Reviews 19, 102597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akiyama S et al. (2020) Prevalence and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. Epub 2020 Oct 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta P et al. (2020) COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet (London, England) 395, 1033–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhaskar S et al. (2020) Cytokine storm in COVID-19-immunopathological mechanisms, clinical considerations, and therapeutic approaches: the REPROGRAM consortium position paper. Frontiers in Immunology 11, 1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Constantin T et al. (2021) Diagnosis and treatment of paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome. Hung Med J (Orv Hetil) 162, 652–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alunno A et al. (2021) 2021 Update of the EULAR points to consider on the use of immunomodulatory therapies in COVID-19. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2022, 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alunno A et al. (2021) Immunomodulatory therapies for SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic literature review to inform EULAR points to consider. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 803–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Favalli EG et al. (2020) COVID-19 infection and rheumatoid arthritis: faraway, so close!. Autoimmunity Reviews 102523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landewe RB et al. (2020) EULAR Provisional recommendations for the management of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in the context of SARS-CoV-2. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 79, 851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American College of Rheumatology (2020) COVID-19 Clinical Guidance for Adult Patients with Rheumatic Diseases. Available at https://wwwrheumatologyorg/Portals/0/Files/ACR-COVID-19-Clinical-Guidance-Summary-Patients-with-Rheumatic-Diseasespdf.

- 22.European League Against Rheumatism (2020) EULAR Guidance for patients COVID-19 outbreak. Available at https://wwweularorg/eular_guidance_for_patients_covid19_outbreakcfm.

- 23.NICE COVID-19 rapid guideline: rheumatological autoimmune, inflammatory and metabolic bone disorders (2020) Available at wwwniceorguk/guidance/ng167. Epub 2020 Apr 3. [PubMed]

- 24.Curtis JR et al. (2021) American College of rheumatology guidance for COVID-19 vaccination in patients With rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: version 3. Arthritis & Rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.) 73, e60–e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bijlsma JW (2021) EULAR December 2020 view points on SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with RMDs. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 411–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujinami RS et al. (2006) Molecular mimicry, bystander activation, or viral persistence: infections and autoimmune disease. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 19, 80–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussein HM and Rahal EA (2019) The role of viral infections in the development of autoimmune diseases. Critical Reviews in Microbiology 45, 394–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galeotti C and Bayry J (2020) Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases following COVID-19. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 16, 413–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramadan N and Shaib H (2019) Middle East Respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): a review. Germs 9, 35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanduc D and Shoenfeld Y (2020) On the molecular determinants of the SARS-CoV-2 attack. Clinical Immunology 215, 108426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onouchi Y et al. (2008) ITPKC Functional polymorphism associated with Kawasaki disease susceptibility and formation of coronary artery aneurysms. Nature Genetics 40, 35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vallianatos CN and Iwase S (2015) Disrupted intricacy of histone H3K4 methylation in neurodevelopmental disorders. Epigenomics 7, 503–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponchel F, Cuthbert RJ and Goeb V (2011) IL-7 and lymphopenia. Clinica Chimica Acta 412, 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caso F et al. (2020) Could sars-coronavirus-2 trigger autoimmune and/or autoinflammatory mechanisms in genetically predisposed subjects? Autoimmunity Reviews 19, 102524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gagiannis D et al. (2020) Clinical, serological, and histopathological similarities between severe COVID-19 and acute exacerbation of connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD). Frontiers in Immunology 11, 587517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Y et al. (2020) Clinical and autoimmune characteristics of severe and critical cases of COVID-19. Clinical and Translational Science 13, 1077–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dotan A et al. (2021) The SARS-CoV-2 as an instrumental trigger of autoimmunity. Autoimmunity Reviews 20, 102792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Favaloro EJ, Henry BM and Lippi G (2021) COVID-19 and antiphospholipid antibodies: time for a reality check? Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis, 72–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zinserling VA et al. (2020) Inflammatory cell infiltration of adrenals in COVID-19. Hormone and Metabolic Research 52, 639–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y et al. (2020) Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine 382, e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiao M et al. (2020) Antiphospholipid antibodies in critically Ill patients with COVID-19. Arthritis & Rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.) 72, 1998–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harzallah I, Debliquis A and Drenou B (2020) Frequency of lupus anticoagulant in COVID-19 patients. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis: JTH 18, 2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helms J et al. (2020) High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Medicine 46, 1089–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veres K et al. (2004) Antiphospholipid antibodies in acute coronary syndrome. Lupus 13, 423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shoenfeld Y et al. (2006) Infectious origin of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 65, 2–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salaffi F et al. (2021) The effect of novel coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) on fibromyalgia syndrome. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology 39(Suppl 130), 72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strangfeld A et al. (2021) Factors associated with COVID-19-related death in people with rheumatic diseases: results from the COVID-19 global rheumatology alliance physician-reported registry. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 80, 930–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sparks JA et al. (2021) Associations of baseline use of biologic or targeted synthetic DMARDs with COVID-19 severity in rheumatoid arthritis: results from the COVID-19 global rheumatology alliance physician registry. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 80, 1137–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pablos JL et al. (2020) Prevalence of hospital PCR-confirmed COVID-19 cases in patients with chronic inflammatory and autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 79, 1170–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pablos JL et al. (2020) Clinical outcomes of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 and chronic inflammatory and autoimmune rheumatic diseases: a multicentric matched cohort study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 79, 1544–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verdoni L et al. (2020) An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet (London, England) 395, 1771–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sokolovsky S et al. (2021) COVID-19 associated Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory disease in an adult. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 39, e1–e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Group RC et al. (2020) Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 - preliminary report. New England Journal of Medicine, 693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramiro S et al. (2020) Historically controlled comparison of glucocorticoids with or without tocilizumab versus supportive care only in patients with COVID-19-associated cytokine storm syndrome: results of the CHIC study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 79, 1143–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: August 6, 2021 (2021) Available at https://wwwfdagov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-august-6-2021. Epub 2021 Aug 6.

- 56.Xu X et al. (2020) Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117, 10970–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gordon AC et al. (2021) Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically Ill patients with COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine 384, 1491–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Recovery Collaborative Group (2021) Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet (London, England) 397, 1637–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stone JH et al. (2020) Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine 383, 2333–2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hermine O et al. (2021) Effect of tocilizumab vs usual care in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 and moderate or severe pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. Jama Internal Medicine 181, 32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sciascia S et al. (2020) Pilot prospective open, single-arm multicentre study on off-label use of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology 38, 529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Della-Torre E et al. (2020) Interleukin-6 blockade with sarilumab in severe COVID-19 pneumonia with systemic hyperinflammation: an open-label cohort study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 79, 1277–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bronte V et al. (2020) Baricitinib restrains the immune dysregulation in patients with severe COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Investigation 130, 6409–6416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsai YC and Tsai TF (2020) Oral disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and immunosuppressants with antiviral potential, including SARS-CoV-2 infection: a review. Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease 12, 1759720X20947296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalil AC et al. (2021) Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine 384, 795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Drug Combination for Treatment of COVID-19 (2020) http://fdagov. Epub 2020 Nov 19.

- 67.Guimaraes PO et al. (2021) Tofacitinib in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia. New England Journal of Medicine 385, 406–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Langer-Gould A et al. (2020) Early identification of COVID-19 cytokine storm and treatment with anakinra or tocilizumab. International Journal of Infectious Diseases: IJID: Official Publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases 99, 291–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pontali E et al. (2021) Efficacy of early anti-inflammatory treatment with high doses of intravenous anakinra with or without glucocorticoids in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 147, 1217–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kyriazopoulou E et al. (2021) Effect of anakinra on mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and patient-level meta-analysis. Lancet Rheumatology 3, e690–e6e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Corimuno-Collaborative-group (2021) Effect of anakinra versus usual care in adults in hospital with COVID-19 and mild-to-moderate pneumonia (CORIMUNO-ANA-1): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine 9, 295–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kyriazopoulou E et al. (2021) Early treatment of COVID-19 with anakinra guided by soluble urokinase plasminogen receptor plasma levels: a double-blind, randomized controlled phase 3 trial. Nature Medicine 27, 1752–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phadke O et al. (2021) Intravenous administration of anakinra in children with macrophage activation syndrome. Pediatric Rheumatology Online Journal 19, 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gharebaghi N et al. (2020) The use of intravenous immunoglobulin gamma for the treatment of severe coronavirus disease 2019: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind clinical trial. BMC Infectious Diseases 20, 786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tabarsi P et al. (2021) Evaluating the effects of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) on the management of severe COVID-19 cases: a randomized controlled trial. International Immunopharmacology 90, 107205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mazeraud A et al. (2021) Intravenous immunoglobulins in patients with COVID-19-associated moderate-to-severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ICAR): multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine, 158–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mazeraud A et al. (2021) Effect of early treatment with polyvalent immunoglobulin on acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infections (ICAR trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 22, 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Horby P et al. (2020) Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine 383, 2030–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mikuls TR et al. (2021) American College of rheumatology guidance for the management of rheumatic disease in adult patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: version 3. Arthritis & Rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.) 73, e1–e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ferro F et al. (2020) COVID-19: the new challenge for rheumatologists. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology 38, 175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Listing J, Gerhold K and Zink A (2013) The risk of infections associated with rheumatoid arthritis, with its comorbidity and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 52, 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.EULAR COVID-19 Registry for rheumatologists and other clinicians (2021) Available at https://wwweularorg/eular_covid_19_registrycfm. Epub 2021 Oct 1.

- 83.Alvaro Gracia JM et al. (2021) Role of targeted therapies in rheumatic patients on COVID-19 outcomes: results from the COVIDSER study. RMD Open 7, e001925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Furer V et al. (2021) Immunogenicity and safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases and in the general population: a multicentre study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 80, 1330–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Park JK et al. (2018) Impact of temporary methotrexate discontinuation for 2 weeks on immunogenicity of seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 77, 898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Boyarsky BJ et al. (2021) Antibody response to a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. Epub 2021 Mar 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mahil SK et al. (2022) Humoral and cellular immunogenicity to a second dose of COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 in people receiving methotrexate or targeted immunosuppression: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Rheumatology 4, e42–e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mahil SK et al. (2021) The effect of methotrexate and targeted immunosuppression on humoral and cellular immune responses to the COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatology 3, e627–ee37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Connolly CM and Paik JJ (2021) Impact of methotrexate on first-dose COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Lancet Rheumatology 3, e607–e6e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barbhaiya M et al. (2022) Immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive medication modification among patients with rheumatic diseases at the time of COVID-19 vaccination. Lancet Rheumatology 4, e85–ee7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]