Abstract

Background

The severity of COVID-19 remains high worldwide. Therefore, millions of individuals are likely to suffer from fear of COVID-19 and related mental health factors.

Aims

The present systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to synthesize empirical evidence to understand fear of COVID-19 and its associations with mental health-related problems during this pandemic period.

Method

Relevant studies were searched for on five databases (Scopus, ProQuest, EMBASE, PubMed Central, and ISI Web of Knowledge), using relevant terms (COVID-19-related fear, anxiety, depression, mental health-related factors, mental well-being and sleep problems). All studies were included for analyses irrespective of their methodological quality, and the impact of quality on pooled effect size was examined by subgroup analysis.

Results

The meta-analysis pooled data from 91 studies comprising 88 320 participants (mean age 38.88 years; 60.66% females) from 36 countries. The pooled estimated mean of fear of COVID-19 was 13.11 (out of 35), using the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. The associations between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors were mostly moderate (Fisher's z = 0.56 for mental health-related factors; 0.54 for anxiety; 0.42 for stress; 0.40 for depression; 0.29 for sleep problems and –0.24 for mental well-being). Methodological quality did not affect these associations.

Conclusions

Fear of COVID-19 has associations with various mental health-related factors. Therefore, programmes for reducing fear of COVID-19 and improving mental health are needed.

Keywords: COVID-19, fear, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, sleep disorders

COVID-19 pandemic and mental health

The entire world has experienced the threat of COVID-19 since the initial outbreak in China at the end of 2019. The World Health Organization1 announced COVID-19 as a global pandemic in March 2020, and the COVID-19 infection rate still remains high globally because of its several mutations.2,3 Indeed, at the time of writing (August 2021), the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases was near to 0.2 billion and the number of deaths had exceeded 4 million across 220 countries and territories worldwide.4 To control COVID-19 infection in an efficient and timely manner, different techniques have been used to rapidly develop COVID-19 vaccines.5 Unfortunately, empirical evidence shows that implementing COVID-19 vaccination programmes is not without difficulties, including the low willingness by some individuals in relation to vaccine uptake.6–9 Moreover, the speed that COVID-19 mutates into different variants is high,3 which may restrict the efficiency of the current COVID-19 vaccines in controlling the infection rate. Therefore, the uncontrolled pandemic causes several severe problems for individuals globally, and one of these problems relates to mental health.

Because the global reach of the COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented, with many different and vigorous infection control methods (e.g. lockdown) implemented,10–12 mental health problems (e.g. psychological distress) during the COVID-19 pandemic have been high.13–17 Moreover, one of the primary triggers for mental health problems during this period is fear of COVID-19.18 More specifically, COVID-19 is a new type of infection, and different stakeholders (including governments, healthcare providers, policy makers and scientists) require information and data to help fight the consequences of the disease. Therefore, fear is likely to develop among many individuals because of the life-threatening effects of COVID-19 and the fact that the many methods implemented to control the infection rate have had varied levels of success. Given that the COVID-19 infection and its severity are unlikely to be under control in the short term,19,20 it is important to accumulate scientific evidence regarding fear of COVID-19 and its association with mental health-related factors. Using the empirical data regarding the associations between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors, healthcare providers and policy makers can understand the importance of controlling fear of COVID-19 during the pandemic period, and implement initiatives to prevent potential mental health problems.

Factors included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis

In the present systematic review and meta-analysis, mental health-related factors, including depression, anxiety, stress, sleep problems, mental health-related factors and mental well-being, were identified, analysed and discussed. These factors were included because they are important factors that affect an individual's ability to live a happy and healthy life. For example, depression, anxiety, stress and mental health-related factors have been found to be important factors that jeopardise sleep quality and physical health.21–23 Moreover, sleep has been identified as an important and essential daily activity for individuals to maintain daily functions.24 In this regard, when individuals encounter any problem related to one of these mental health-related factors, their quality of life and well-being is jeopardised, and a minority of individuals may develop serious health problems.25–27

More specifically, when individuals encounter a mental health-related problem, they need additional support from community and/or healthcare systems to assist them in coping with both mental and physical health problems. Moreover, individuals with mental health-related problems may have decreased productivity, resulting in fewer contributions to society.25–27 As a result, society and healthcare system have higher levels of burden if the society and community have larger proportion of residents living with mental health-related problems.25–27 Therefore, understanding the associations between fear of COVID-19 and the aforementioned mental health-related factors are of great importance during the COVID-19 pandemic period.

Purpose and aim of the present systematic review and meta-analysis

Consequently, the present systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out to provide empirical evidence for healthcare workers and related stakeholders (e.g. government authorities, policy makers) to better understand fear of COVID-19 and its associations with mental health-related problems during the pandemic period. The main aims of the review were to (a) estimate the mean fear of COVID-19 scores in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic from studies, using the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S); (b) assess the association of fear of COVID-19 with mental health-related factors (including depression, anxiety, stress, sleep problems, mental health-related factors and mental well-being) in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic; (c) identify potential sources of heterogeneity and its possible sources for the aforementioned mean and association estimations; and (d) identify moderators in the mean estimation and association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors.

Method

Design and protocol registration

The project was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) website (registration number CRD42020188890.28 The study's findings are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.29

Search strategy

From December 2019 to June 2021, five academic databases (i.e. Scopus, ProQuest, EMBASE, PubMed Central and ISI Web of Knowledge) were systematically searched. COVID-19-related fear, in combination with mental health-related keywords including anxiety, depression, psychological distress, mental well-being and sleep problems, were used to develop search syntax. The relevant search terms were extracted from PubMed Medical Subject Headings and published studies. Search syntax was customised for the aforementioned academic databases based on their search attributes. Additionally, hand searches were performed by reading reference lists of included studies and published systematic reviews to increase the retrieval of relevant studies.

Outcomes

The main outcomes of the present systematic review were mean of fear of COVID-19 was estimated in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic based on FCV-19S scores internationally; and the association of fear of COVID-19 with other mental health-related factors (mentioned below), which was calculated in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, fear of COVID-19 was defined as the threatening stimulus of COVID-19 resulting in the triggering of unpleasant emotional state among individuals.30

The secondary outcomes were to identify potential sources of heterogeneity and its possible sources, moderators in mean estimation fear of COVID-19, and moderators in the association of fear of COVID-19 with other mental health-related factors. The other mental health-related factors were defined as follows: depression, defined as lacking interests of engaging in activities and having low mood without pleasure;31 anxiety, defined as having excessive worry on various activities, events, topics and daily errand;31 stress, defined as a nonspecific response from an individual's body that reacts to any demands;32 sleep problems, defined as sleep disorders in a broad category with some subcategories, including intrinsic, extrinsic and disturbances of circadian rhythm;33 mental health-related factors, defined as perceived discomfort from response to stressors that is hard to cope with;34 and mental well-being, defined as the psychological processes of individuals that promote life outcomes in a positive way, including happiness and growth toward optimal development.35

Eligibility criteria

All peer-reviewed observational studies published in the English language were considered eligible if relevant data regarding mean scores regarding fear of COVID-19 (on the FCV-19S) and their association with mental health problems and/or distress (e.g. anxiety, depression, mental health-related factors, mental well-being and sleep problems) were reported. To be included, the fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors had to have been assessed by valid and reliable psychometric scales. No limitation was exerted regarding participants’ characteristics. More specifically, studies were excluded if they had other study designs (intervention studies, letters to the editor, editorials, qualitative studies, systematic reviews), did not report numerical findings regarding the selected outcome measures, did not have valid or reliable measures for assessing the selected variables and were non-English language publications.

Screening process and study selection

First, titles and abstracts of all retrieved papers were independently screened based on eligibility criteria, by two of the research team. Then full texts of potentially eligible papers were downloaded and reviewed for final selection. During this process, relevant studies were selected. This stage was carried out independently by two members of the research team. The kappa score showed strong agreement between these reviewers (κ = 0.83).

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included papers was assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) checklist.36 The NOS checklist assesses the methodological quality of papers in three domains of selection, and comparability with seven items for cross-sectional studies. Studies yielding fewer than five points are classified as having a high risk of bias.36 No studies in the present review were excluded on the basis of poor methodological quality. However, the impact of quality on pooled effect size was assessed by subgroup analysis. Quality assessment of included studies were carried out independently by two members of the research team. The kappa score showed strong agreement between these reviewers (κ = 0.78).

Data extraction

A predefined Microsoft Excel version 2016 for Windows spreadsheet was designed to extract data based on the study aims and selected outcomes. Data extracted included the first author's name, publication date, title of the study, country of research, target population of study (categorised as general population, healthcare professionals and patients with COVID-19), sample size, study design, fear of COVID-19 measures and scores (including mean and s.d.), mental health-related factor outcomes measures and their association with fear of COVID-19, and NOS score (i.e. methodological quality). Data extraction of included studies were carried out independently by two members of the research team. The kappa score showed strong agreement between these reviewers (κ = 0.75).

It should also be noted that study selection, quality assessment and data extraction were processes performed independently by two reviewers. Disagreements regarding whether a study should be included or not, methodological quality assessment of included studies and data extraction were resolved through discussion by independent reviewers.

Data synthesis

A quantitative synthesis using Stata software version 14 for Windows was conducted. Meta-analysis was run with random effect model because the included studies were taken from different populations, and both within-study and between-study variances should be accounted for.37 The Q Cochrane statistic was used to assess heterogeneity. Also, the severity of heterogeneity was estimated with the I2 index. Heterogeneity is interpreted as mild when I2 is <25%, moderate when I2 is 25–50%, severe when I2 is 51–75% and highly severe when I2 is >75%.38 Two key measures were selected for present study:

Mean score of fear of COVID-19 (using the FCV-19S): The numerical findings regarding means and standard deviations of fear of COVID-19 scores were reported consistently in 71 included studies. This key measure and its 95% confidence interval were reported.

Correlation of fear of COVID-19 with other mental health-related factors: Other mental health-related factors were defined as depression, anxiety, stress, sleep problems, mental health-related factors and mental well-being. Pearson's correlation coefficient was the selected effect size for meta-analysis in assessing the associations between fear of COVID-19 and these mental health-related factors. Because of the potential instability of variance, Pearson's r correlation coefficient was converted to Fisher's z-statistic. Consequently, all analyses were performed with Fisher's z-values as effect sizes.39,40 Fisher's z-transformation was applied by using the following formula: z = 0.5 × ln[(1 + r) − (1 − r)]. The s.e. of z was calculated based on the following formula: s.e. z = 1/√(n − 3).41 Therefore, the selected measure of effect (selected for current meta-analysis) is expressed as Fisher's z-score and its 95% confidence interval. Moreover, Fisher's z at 0.1 is defined as weak, 0.11–0.3 is defined as weak to moderate, 0.3 is defined as moderate, 0.31–0.49 is defined as moderate to strong and ≥0.5 is defined as strong. For assessing moderator analysis, subgroup analysis or meta-regression was carried out. Funnel plot and the Begg's test were used to assess publication bias.42 The jackknife method was used for sensitivity analysis43 and to determine the effect of individual studies on the outcome. The jackknife method is also known as the ‘one-out method’, and was used to evaluate the quality and consistency of the results. More specifically, significant changes can be evaluated by removing each study individually.44

Results

Screening and selection process

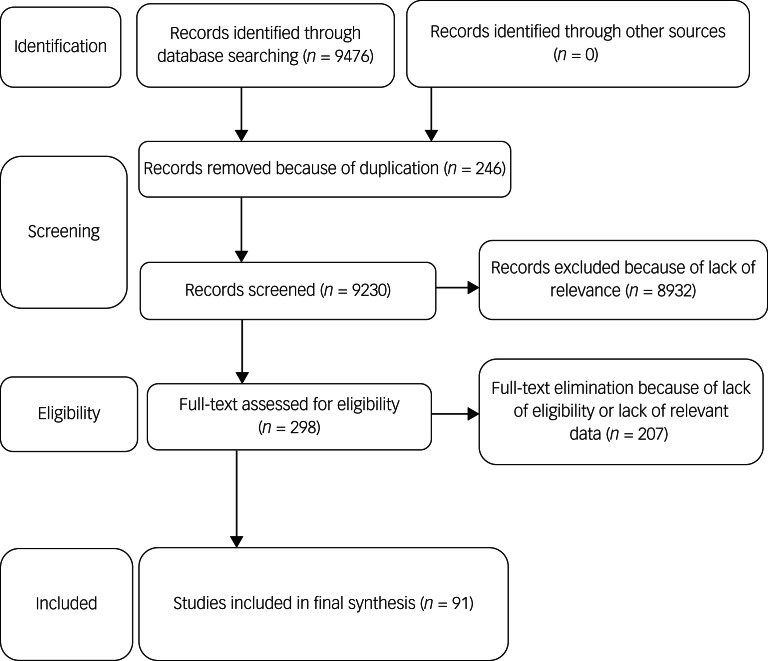

The initial search of five databases identified 9476 papers: Scopus (n = 1768), Web of Science (n = 1200), PubMed (n = 1240), EMBASE (n = 5012) and ProQuest (n = 256). After removing 246 duplicates, 9230 papers were screened based on the title and abstract. Finally, 298 papers deemed as eligible had their full texts were reviewed. During this process, 91 papers met the eligibility criteria and were pooled in the meta-analysis. Fig. 1 shows the search process based on the PRISMA (2009) flow chart.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart of selected studies.

Study description

A total of 91 studies were included in the final analysis. Included studies comprised 88 320 participants from 36 countries (Australia, Bangladesh, Brazil, Canada, China, Ecuador, Egypt, Germany, Greece, India, Iran, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Korea, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, The Netherlands, Pakistan, Paraguay, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Romania, Russia, Taiwan, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Spain, United Arab Emirates, UK, USA and Vietnam). Turkey (n = 10 papers), Iran (n = 6 papers), Bangladesh (n = 5 papers) and Pakistan (n = 5 papers) had the highest number of studies. Almost all studies (n = 90) employed a cross-sectional design. Seven papers collected data during national lockdown periods in their respective countries. The target populations in the studies were either the general population (n = 80) or healthcare professionals (n = 11). Sample size varied between 58 and 10 067 participants. Mean age of participants was 38.88 years. Approximately 61% of the total number of participants were females. The FCV-19S, developed by Ahorsu et al,45 was the most frequently used instrument to assess COVID-19-related fear in 71 studies. Mental health-related factors assessed included sleep problems (n = 9), depression (n = 49), anxiety (n = 48), stress (n = 19), psychological distress (n = 6) and mental well-being (n = 3). Different valid and reliable psychometric instruments were used to assess these outcomes. Table 1 provides the summary characteristics of all included studies.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of included studies

| Study | Collection date | Country | Design | Participant group | Lockdown period | Sample size | Gender group | Female, % | Age, years | Fear of COVID-19 Scale | Psychological measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46 | India | Cross-sectional | General population | Yes | 625 | Both | 37.80 | 17–23 | FCV-19S | PSS-4; WHO-5 | |

| 47 | Bangladesh | Cross-sectional | General population | 262 male and 259 female | Both | 49.71 | 24.78 | FCV-19S | PSQI; PSS-10 | ||

| 48 | 15 June to 15 July 2020 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | General population | Yes | 1030 | Both | 76.10 | 36.40 | FCV-19S | HADS |

| 49 | 18 March to 15 May 2020 | Spain | Cross-sectional | General population | 124 | Both | 48.40 | 41.20 | FCV-19S | STAI | |

| 50 | Iran | Cross-sectional | Treatment-seeking patients with principal diagnoses of anxiety disorders | 300 | Both | 58.70 | 36.12 | COVID-19 Phobia Scale | PHQ-4; SHAI | ||

| 51 | May 2020 to June 2020 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | Older population | 310 | Both | 31.90 | 50−80 | FCV-19S | HADS | |

| 52 | April and May 2020 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | Undergraduate and graduate university students | 506 | Both | 78.70 | 21.69 | FCV-19S | DASS | |

| 53 | China | Longitudinal | College students | 867 | Both | 69.00 | 20.17 | Fear of contagion | PSS-10 | ||

| 54 | June 2020 | Australia | Cross-sectional | General population | 516 | Both | 62 | 41.10 | FCV-19S | Kessler Psychological Distress Scale | |

| 55 | Pakistan | Time-lagged | General population | 267 | Both | 34.00 | FCV-19S | PHQ-9 | |||

| 56 | 29 June to 9 August 2020 | Germany | Cross-sectional | General population | 515 | Both | 90.30 | FCV-19S | SHAI | ||

| 57 | 11 April to 11 May 2020 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | General population | 1029 | Both | 47.30 | 33.70 | FCV-19S | HADS | |

| 58 | 11 and 20 April 2020 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | General population | 693 | Both | 42 | 34.75 | FCV-19S | HADS | |

| 59 | Ecuador | Cross-sectional | Undergraduate students | Yes | 640 | Both | 72.00 | 21.69 | DASS | ||

| 60 | 31 January to 9 February 2020 | China | Cross-sectional | General population | 3233 | Both | 54.38 | 31.71 | FCV-19S | Psychological questionnaire for emergent events of public health | |

| 61 | 1 April to 30 April 2020 | Iran | Cross-sectional | General population | 413 | Both | 38.00 | 57.72 | FCV-19S | ISI; PHQ-9 | |

| 62 | 11 and 15 May 2020 | Poland | Cross-sectional | Cancer patients | 306 | Both | 54.58 | 63.00 | FCV-19S | Numeric Anxiety Scale | |

| 63 | April and May 2020 | Iran | Cross-sectional | General population | 651 | Both | 62.40 | FCV-19S | Anxiety Sensitivity Questionnaire | ||

| 64 | Philippines | Cross-sectional | Front-line nurses | 261 | Both | 73.56 | 30.95 | FCV-19S | |||

| 65 | March and April 2020 | Iran | Cross-sectional | Pregnant women | 222 | Female | 100.00 | 29.10 | FCV-19S | DASS | |

| 66 | 31 March to 21 April 2020 | Hong Kong | Cross-sectional | General population | 219 | Both | 74.90 | 23.17 | COVID-19 Fear (Higher Education) Scale | GAD-7 | |

| 67 | 19 June and 10 July 2020 | Brazil | Cross-sectional | Pregnant women | 204 | Female | 100.00 | 30.12 | FCV-19S | PDSS-24; PSS-10 | |

| 68 | Japan | Cross-sectional | General population | 450 | Both | 35.00 | 48.13 | FCV-19S | HADS | ||

| 69 | 1 and 30 June 2020 | Australia | Cross-sectional | General population | 58 | Both | 61.80 | 41.30 | FCV-19S | ||

| 70 | 20 September and 30 October | Vietnam | Cross-sectional | General population | 1510 | Both | 56.70 | >18 | Fear and anxiety of COVID-19 | PROMIS six-item Sleep Disturbance Scale; Kessler Psychological Distress Scale | |

| 71 | Japan | Cross-sectional | General population | 222 | Both | 43.70 | >18 | FCV-19S | DASS | ||

| 72 | The Netherlands | Cross-sectional | General population | 546 | Both | 44.69 | >18 | Fear of the Coronavirus Questionnaire | DASS | ||

| 73 | June and November 2020 | Korea | Cross-sectional | General population | 203 | Both | 57.64 | 39.63 | FCV-19S | HADS | |

| 74 | Singapore | Cross-sectional | General population | 413 | Both | 65.40 | 69.09 | COVID-19 Fear Inventory | GDS-15; GAI-SF | ||

| 75 | 1–25 May 2020 | UK | Cross-sectional | General population | Yes | 165 | Both | 61.00 | 15.90 | Coronavirus Inventory | HADS; PSS |

| 76 | 16–23 August 2020 | Jordan | Cross-sectional | Healthcare workers | 365 | Both | 55.60 | >20 | FCV-19S | DASS | |

| 77 | 8 October to 26 November 2020 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | General population | 3287 | Both | 56.70 | >16 | FCV-19S | DASS | |

| 78 | 4–25 August 2020 | Japan | Cross-sectional | General population | 6750 | Both | 63.50 | >18 | FCV-19S | GAD-7; Kessler Psychological Distress Scale | |

| 79 | 15 March and 30 April 2020 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | General population | 431 | Both | 66.60 | 33.81 | FCV-19S | ||

| 80 | 9–13 July 2020 | India | Cross-sectional | General population | 163 | Both | 26.64 | FCV-19S | CESD; GAD-7 | ||

| 81 | April to June 2020 | Lebanon | Cross-sectional | Individuals with physical disabilities | 118 | Both | 11.90 | 37.75 | FCV-19S | Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25 | |

| 82 | May 2020 | UK | Cross-sectional | General population | 226 | Both | 29.80 | FCV-19S | |||

| 83 | 19–21 March 2020 | Paraguay | Cross-sectional | General population | 1077 | Both | 68.71 | 30.95 | FCV-19S | HADS | |

| 84 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | General population | 255 | Both | 88.00 | 32.96 | FCV-19S | DASS | ||

| 85 | 15 April and 15 May 2020 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | General population | 362 | Both | 66.90 | 26.89 | FCV-19S | HADS | |

| 86 | 20–31 May 2020 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | General population | 355 | Both | 71.50 | 22.41 | FCV-19S | SCL-90 | |

| 87 | May 2020 | China | Cross-sectional | General population | 1794 | Both | 43.80 | 15.26 | FCV-19S | Youth Self-Rating Insomnia Scales | |

| 88 | 27 April and 10 May 2020 | Romania | Cross-sectional | General population | 809 | Both | 65.40 | 32.61 | FCV-19S | Short Depression-Happiness Scale; PSS | |

| 89 | July to October 2020 | USA | Cross-sectional | Patients with ovarian cancer | 100 | Female | 100.00 | 55.03 | FCV-19S | DASS | |

| 90 | 25 May to 12 June 2020 | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | General population | 255 | Both | 65.50 | FCV-19S | DASS | ||

| 91 | 1–10 April 2020 | Bangladesh | Cross-sectional | General population | 10067 | Both | 43.90 | >10 | FCV-19S | ISI | |

| 92 | 17 September and 10 November 2020 | Canada | Cross-sectional | Ophthalmology tertiary care centre | 160 | Both | 69.40 | FCV-19S | |||

| 93 | 30 June to 29 September 2020 | Egypt | Cross-sectional | Patients with diabetes mellitus | 200 | Both | 63.00 | 48.40 | FCV-19S | ||

| 94 | 1 April to 30 May 2020 | Canada | Cross-sectional | General population | 434 | Male | 0.00 | 39.76 | FCV-19S | ||

| 95 | 2 and 24 July 2020 | UK | Cross-sectional | People with chronic pain | 555 | Both | 86.30 | 40.00 | FCV-19S | PHQ-9 | |

| 96 Study 1 | Apr 2020 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | General population | 316 | Both | 71.00 | Fear of COVID-19 | Cole Insomnia Scale | ||

| 96 Study 2 | May 2020 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | General population | 421 | Both | 74.00 | Fear of COVID-19 | Cole Insomnia Scale | ||

| 97 | 10 May to 9 June 2020 | Egypt | Cross-sectional | Physicians | 320 | Both | 63.40 | 34.60 | FCV-19S | HADS | |

| 98 | Italy | Cross-sectional | General population | 1200 | Both | 76.60 | 39.59 | FCV-19S | SCL-90 | ||

| 99 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | Healthcare providers | 208 | Both | 27.90 | 29.00 | FCV-19S | |||

| 100 | 1–30 May 2020 | United Arab Emirates | Cross-sectional | General population | 433 | Both | 35.8 | 21 | FCV-19S | Kessler Psychological Distress Scale | |

| 101 | 13–22 February 2020 | China | Cross-sectional | General population | 4164 | Both | 48 | COVID-19 Fear Screening Scale | PHQ-9 | ||

| 102 | Greece | Cross-sectional | General population | 103 | Both | 61.17 | >60 | FCV-19S | |||

| 103 | 10–13 April 2020 | Greece | Cross-sectional | General population | Yes | 3029 | Both | 71.9 | >18 | FCV-19S | PHQ-9; GAD-7 |

| 104 | 17 April to 3 May 2020 | Italy | Cross-sectional | Dentists | 735 | Both | 32.7 | 44.8 | FCV-19S | DSM-5 Severity Measure for Depression–Adult | |

| 45 | Iran | Cross-sectional | General population | 717 | Both | 42 | 31.25 | FCV-19S | HADS | ||

| 105 | 18–21 March 2020 | Italy | Cross-sectional | General population | 249 | Both | 92 | 34.5 | FCV-19S | HADS | |

| 106 | 23-30 April 2020 | Bangladesh | Cross-sectional | General population | 232 | Both | 45.3 | 18-25 | FCV-19S | DASS | |

| 107 | March to April 2020 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | General population | 960 | Both | 69.1 | 29.74 | FCV-19S | DASS | |

| 108 | 17–23 April 2020 | Peru | Cross-sectional | General population | 546 Females and 28 males | Female | 65.63 | 38.37 | FCV-19S | PHQ-9; GAD-7 | |

| 109 | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | General population | 228 | Both | 71.1 | 26 | FCV-19S | DASS | ||

| 110 | Russia | Cross-sectional | General population | 939 | Both | 80.8 | 21.8 | FCV-19S | |||

| 111 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | Nurses | 380 | Both | 84.21 | 31.5 | FCV-19S | Cavanagh Psychological Distress Scale | ||

| 112 | Mexico | Cross-sectional | Hospital staff | 2860 | Both | 57.4 | 35.4 | FCV-19S | |||

| 113 | 1 April to 30 May 2020 | Bangladesh | Cross-sectional | Front-line doctors | 370 | Both | 39.7 | 30.5 | FCV-19S | ||

| 114 | May 2020 | Greece | Cross-sectional | General population | Yes | 538 | Both | 77.9 | 43.05 | FCV-19S | GAD-7 |

| 115 | 7 March and 21 April 2020 | Iran | Cross-sectional | Pregnant women | 290 Female and 290 male | Female | 50 | 29.24 | FCV-19S | HADS | |

| 116 | 15 May 2020 | Japan | Cross-sectional | General population | 629 | Both | 49.13 | 12.96 | FCV-19S | PHQ-9; GAD-7 | |

| 117 | 10–23 May 2020 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | General population | Yes | 501 | Both | 41.5 | >25 | FCV-19S | |

| 118 | India | Cross-sectional | General population | 600 | Both | 61 | 38.76 | FCV-19S | Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale | ||

| 119 | June to July 2020 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | Nursing students | 234 | Both | 67.9 | 20.12 | FCV-19S | Beck Anxiety Inventory | |

| 120 | March to April 2020 | Israel | Cross-sectional | General population | 649 | Both | 84.5 | FCV-19S | DASS | ||

| 121 | July 2020 | Spain | Cross-sectional | Healthcare workers | 194 | Both | 83.5 | 45.94 | FCV-19S | HADS | |

| 122 | Russia | Cross-sectional | General population | 850 | Both | 73.2 | 34.8 | FCV-19S | |||

| 123 | Poland | Cross-sectional | General population | 907 | Both | 57.55 | 39.28 | FOC-6 | PSS | ||

| 124 | 22–26 April 2020 | Spain | Cross-sectional | General population | 606 | Both | 82 | 21.59 | FCV-19S | STAI | |

| 125 | May to July 2020 | Philippines | Cross-sectional | Nursing students | 261 | Both | 81.2 | 20.7 | FCV-19S | Sleep Quality Scale by Snyder | |

| 126 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | General population | 1772 | Both | 70 | 24.42 | FCV-19S | Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale | ||

| 127 | Israel | Cross-sectional | General population | 130 | Female | 100 | 36.15 | FCV-19S | Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) | ||

| 128 | 27 April to 5 May 2020 | Italy | Cross-sectional | General population | 623 | Both | 71.9 | 35.67 | Multidimensional Assessment of COVID-19-Related Fears | DSM-5 Self-Rated Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure–Adult | |

| 129 | China | Cross-sectional | General population | 907 | Both | 60 | FCV-19S | GAD-7 | |||

| 130 | 1–10 April 2020 | Bangladesh | Cross-sectional | General population | 8550 | Both | 44 | 26.53 | FCV-19S | PHQ-9 | |

| 131 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | General population | 381 | Both | 49.4 | 15.36 | FCV-19S | Revised Children's Anxiety and Depression Scale | ||

| 132 | 23 March to 30 June 2020 | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | Patients with mental illness | 414 | Both | 44.4 | 46.32 | FCV-19S | ||

| 133 | Greece | Cross-sectional | General population | 2970 | Both | 72.5 | >18 | FCV-19S | PHQ-9; GAD-7 | ||

| 134 | 27 - 28 March 2020 | UK | Cross-sectional | General population | 324 | Both | 50 | 34.32 | FCV-19S | PROMIS-SF | |

| 135 | 15 May to 15 June 2020 | Poland | Cross-sectional | General population | 708 | Both | 57.49 | 33.4 | FCV-19S |

FCV-19S, Fear of COVID-19 Scale; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; WHO-5, WHO-Five Well-Being Index; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Index; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; SHAI, Short Health Anxiety Inventory; DASS, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PDSS-24, Perinatal Depression Screening Scale; PASS, Perinatal Anxiety Screening Scale; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; GDS-15, Geriatric Depression Scale; GAI-SF, Geriatric Anxiety Inventory–Short Form; CESD, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SCL-90, Symptom Checklist-90; PROMIS-SF, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, Short Form.

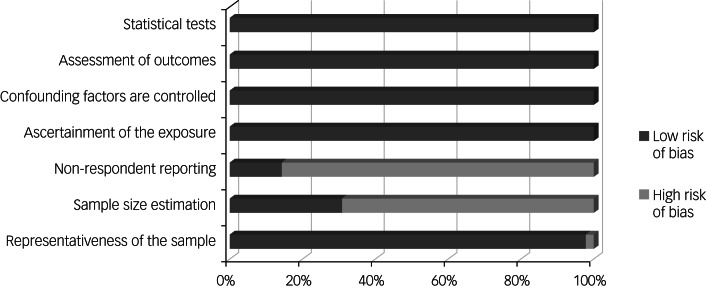

Methodological quality appraisal

Methodological quality together with risk of bias were both assessed on the basis of NOS scores. The scores were then categorised as having a low risk of bias if studies acquired scores higher than 5 from maximum score of 9.36 Based on this criterion, all studies were categorised as being high-quality studies. The effects of study quality were further assessed and reported in subgroup analysis. The most common problems were non-representativeness of the sample owing to online sampling, not reporting sample size estimation or justification, and number of non-respondents. The results of the quality assessment are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Results of quality assessment.

Outcome measures

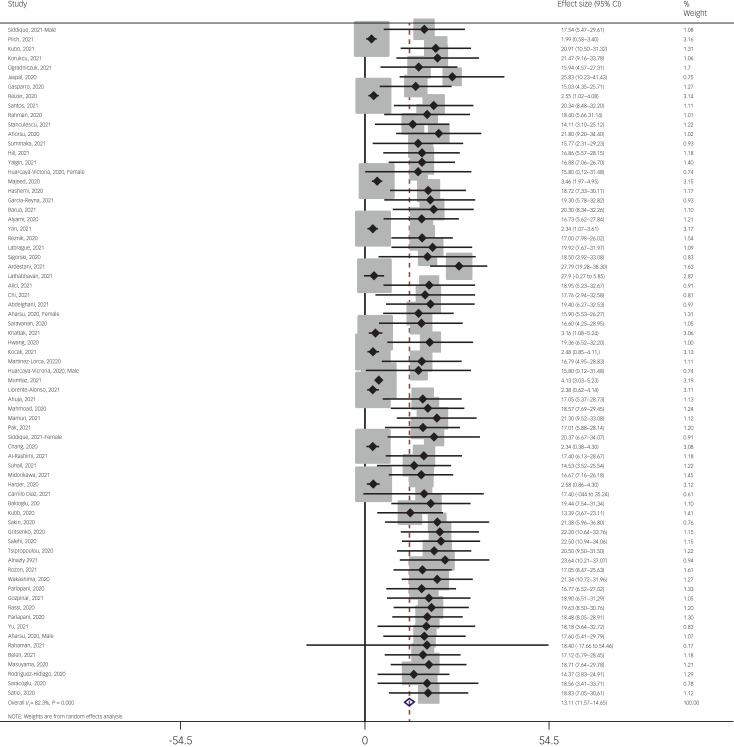

Mean estimation of fear of COVID-19

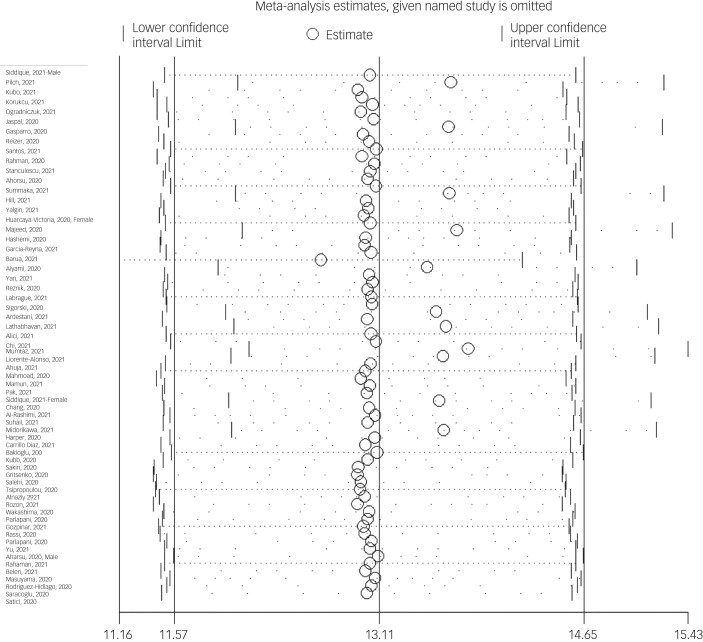

The pooled estimated mean of fear of COVID-19 was 13.11 out of 35, according to the FCV-19S (95% CI 11.57–14.65, I2 = 82.3%, τ2 = 19.02). More specifically, 76 studies reported mean fear scores, with 71 studies using the FCV-19S and five papers using other instruments. Because of the variation in the number of questions and the scoring method between the FCV-19S and the other instruments, mean estimation of fear of COVID-19 was meta-analysed using the 71 studies that utilised the FCV-19S. Fig. 3 provides the forest plot showing the pooled mean scores for fear of COVID-19.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot displaying the pooled estimated mean of fear of COVID-19.

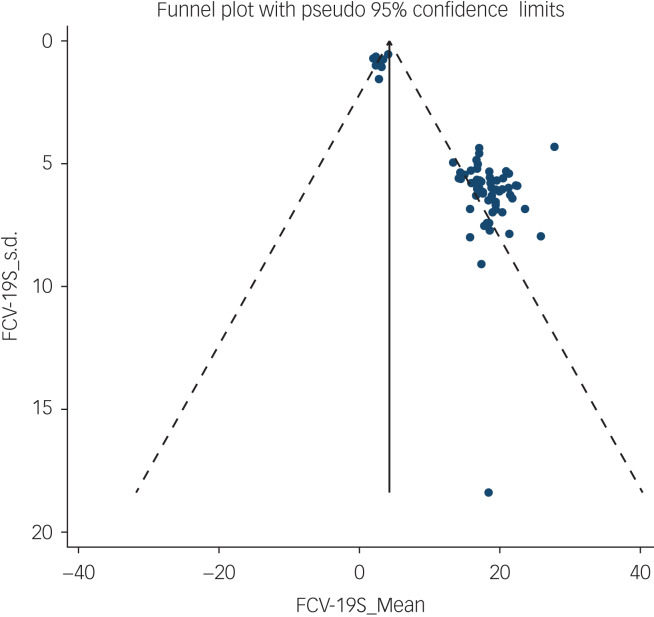

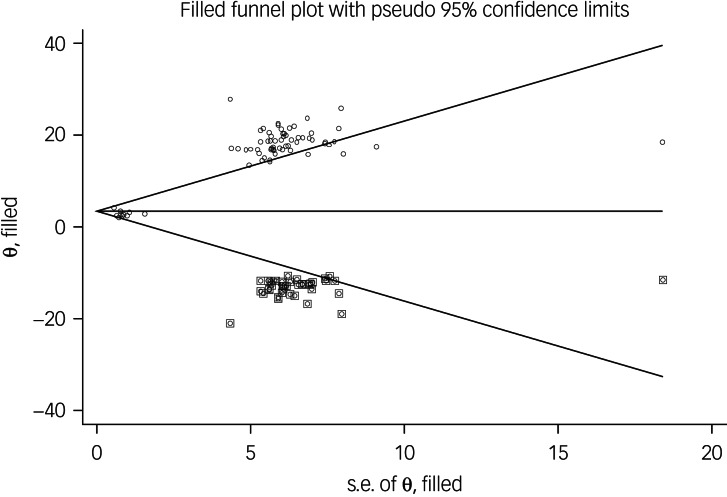

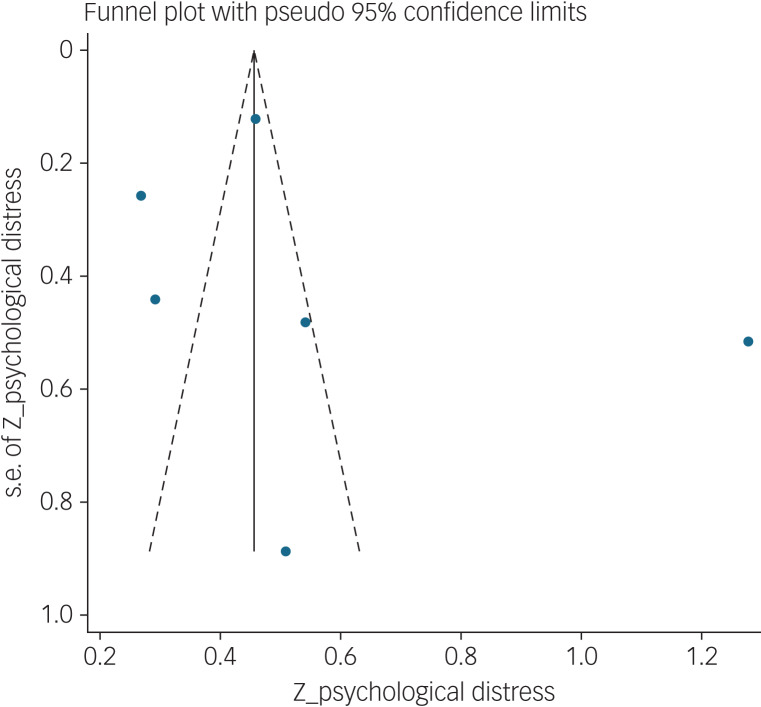

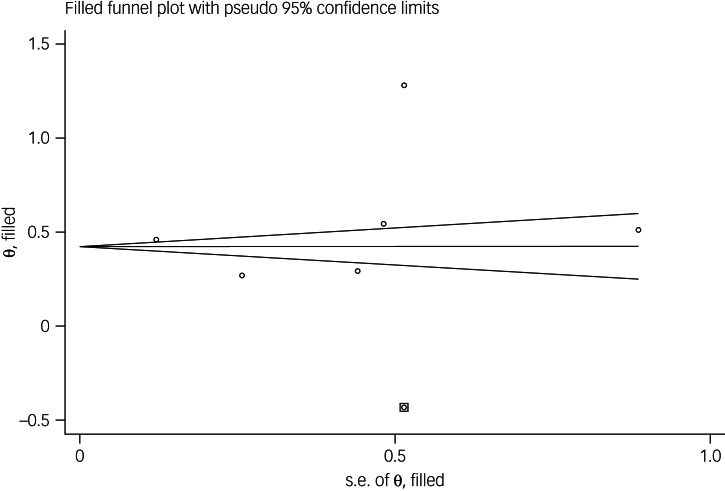

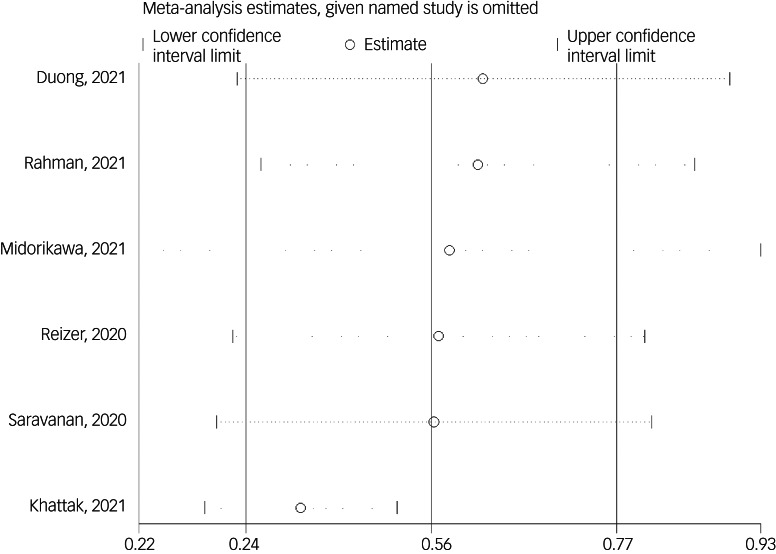

The probability of publication bias was assessed by Begg's test and funnel plot. Although the Begg's test (P = 0.63) did not consider publication bias, the funnel plot (Fig. 4) confirmed the probability of publication bias. Also, sensitivity analysis showed that the pooled effect size might be affected by the single-study effect (P < 0.001; Fig. 5). To this end, the fill-and-trim method was used to correct the results. In this method, 35 studies were imputed and the corrected results based on this method showed that pooled mean score of COVID-19-related fear was 6.20 (95% CI 4.69–7.71, P < 0.001). The funnel plot after trimming is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot assessing publication bias in studies regarding pooled estimated mean of fear of COVID-19.

Fig. 5.

Sensitivity analysis plot assessing small study effect in pooled estimated mean of fear of COVID-19.

Fig. 6.

Corrected funnel plot assessing publication bias in pooled estimated mean of fear of COVID-19.

Subgroup analysis showed that higher mean score was observed respectively in studies with male-only participants (16.79), female-only participants (14.89) and with gender participants (13), but this difference was not significant. Other variables did not influence heterogeneity or estimated pooled mean. Results of the subgroup analysis and meta-regression are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis for estimation mean for fear of COVID-19

| Variable | Number of studies | Effect size (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lockdown period | Yes | 5 | 13.18 (4.72–21.65) | 82.8 |

| No | 66 | 13.19 (11.59–14.79) | 79.9 | |

| Gender group | Both genders | 61 | 13 (11.35–14.64) | 82.9 |

| Female only | 6 | 14.89 (5.58–24.20) | 83.8 | |

| Male only | 4 | 16.79 (10.51–23.07) | 0 | |

| Participant groups | General population | 61 | 13.30 (11.63–14.97) | 82.6 |

| Healthcare professionals | 10 | 13.11 (8.64–18.13) | 82.1 | |

| Overall estimated prevalence | 73 | 13.21 (11.71–14.72) | 82.4 | |

Table 3.

Meta-regression analysis for estimation mean for fear of COVID-19

| Variable | Number of studies | Coefficient | s.e. | P-value | I2 residual (%) | Adjusted R2 (%) | τ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 71 | 0.008 | 0.09 | 0.94 | 82.53 | −1.50 | 45.4 |

| Age | 60 | −0.11 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 82 | 1.87 | 41.88 |

| Newcastle–Ottawa Scale score | 71 | 1.46 | 1.20 | 0.65 | 82.49 | 1.41 | 44.1 |

| Female % of participants | 69 | 0.009 | 0.04 | 0.99 | 82.70 | −1.38 | 47.41 |

Association between fear of COVID-19 and depression

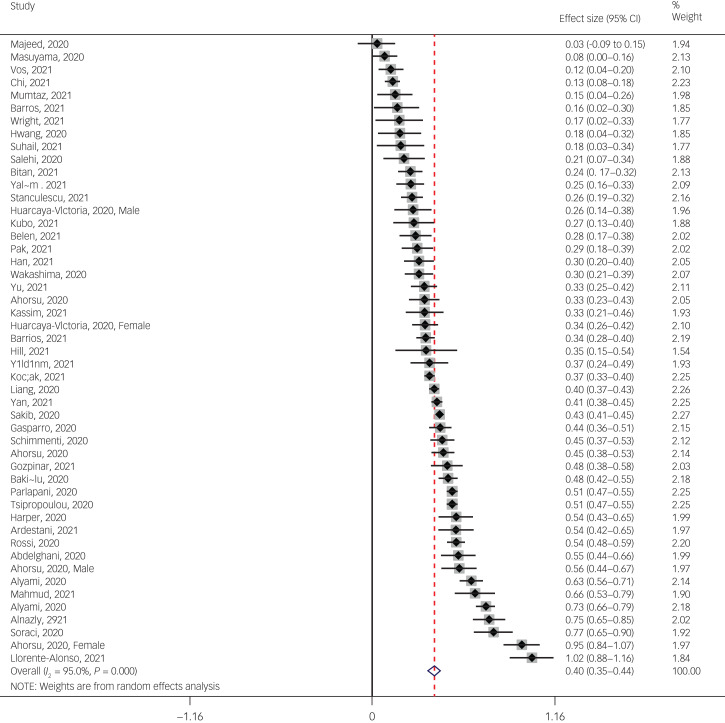

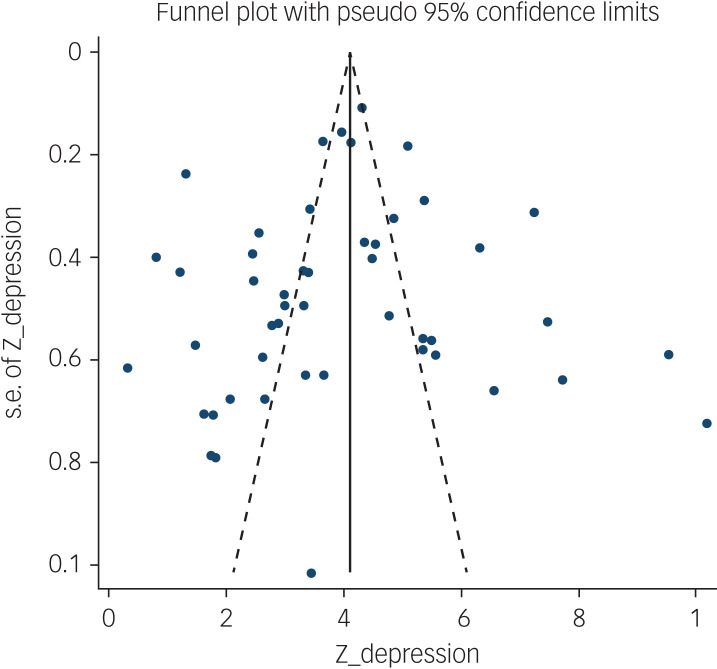

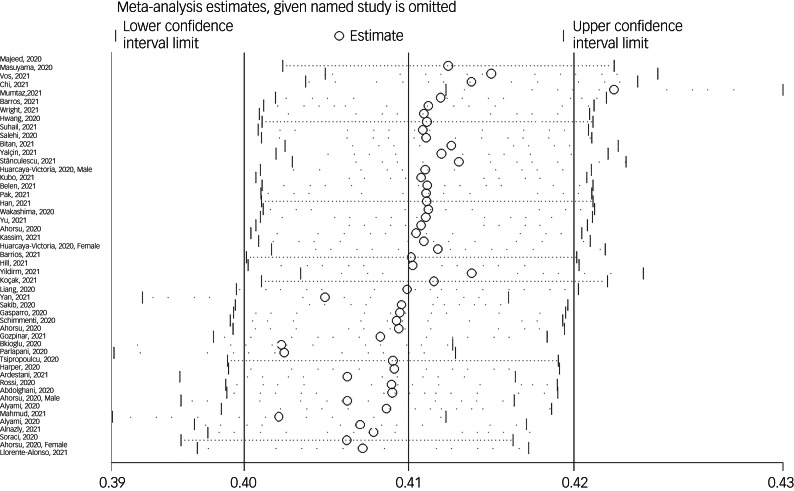

The association between fear of COVID-19 and depression was reported in 49 studies. The pooled estimated effect size showed moderate to strong correlation between fear of COVID-19 and depression, with a Fisher's z-score of 0.40 (95% CI 0.35–0.44, I2 = 95%, τ2 = 0.02). The forest plots are shown in Fig. 7. The probability of publication bias was assessed by Begg's test and funnel plot. Publication bias was not found in the association of fear of COVID-19 and depression based on Begg's test (P = 0.57) or funnel plot (Fig. 8). Sensitivity analysis showed that the pooled effect size was not affected by the single-study effect (P = 0.51; Fig. 9).

Fig. 7.

Forest plot displaying the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and depression.

Fig. 8.

Funnel plot assessing publication bias in studies regarding the association between fear of COVID-19 and depression.

Fig. 9.

Sensitivity analysis plot assessing small study effect in the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and depression.

Subgroup analysis showed that association between fear of COVID-19 and depression was significantly higher among healthcare professionals compared with the general population (0.68 v. 0.37). Also, a higher association was observed among studies with male-only participants (0.61) compared with studies with female-only participants (0.32) and both gender participants (0.40), but this difference was not significant. Other variables did not influence heterogeneity or estimated pooled Fisher's z-score. Results of the subgroup analysis and meta-regression are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis for association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factor outcomes

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | Sleep problems | Mental health-related factors | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Number of studies | Effect size (95% CI) | I2 (%) | Number of studies | Effect size (95% CI) | I2 (%) | Number of studies | Effect size (95% CI) | I2 (%) | Number of studies | Effect size (95% CI) | I2 (%) | Number of studies | Effect size (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |

| Lockdown period | No | 47 | 0.40 (0.35–0.44) | 95 | 44 | 0.53 (0.46–0.60) | 97.2 | 16 | 0.44 (0.36–0.52) | 93.5 | 9 | 0.29 (0.22–0.37) | 92.4 | 6 | 0.56 (0.34–0.77) | 98.5 |

| Yes | 2 | 0.35 (0.02–0.68) | 94.3 | 4 | 0.70 (0.50–0.91) | 96.5 | 3 | 0.33 (0.26–0.39) | 35.2 | |||||||

| Gender Group | Both genders | 42 | 0.40 (0.35–0.44) | 95.1 | 42 | 0.55 (0.48–0.63) | 97.8 | 18 | 0.42 (0.35–0.49) | 92.9 | 9 | 0.29 (0.22–0.37) | 92.4 | 5 | 0.57 (0.33–0.80) | 98.8 |

| Female only | 5 | 0.32 (0.19–0.46) | 83.1 | 4 | 0.52 (0.40–0.65) | 75.5 | 1 | 0.62 (0.42–0.82) | − | 1 | 0.51 (0.34–0.68) | − | ||||

| Male only | 2 | 0.61 (−0.07 to 1) | 98.5 | 2 | 0.41 (0.33–0.49) | 0 | ||||||||||

| Measure of fear | Fear of COVID-19 Scale | 43 | 0.41 (0.36– 0.45) | 95.3 | 42 | 0.55 (0.48– 0.63) | 97.7 | 15 | 0.47 (0.40– 0.54) | 90.2 | 5 | 0.28 (0.15– 0.40) | 95.1 | 5 | 0.62 (0.33– 0.90) | 98.5 |

| Other | 6 | 0.33 (0.22– 0.44) | 91.2 | 6 | 0.48 (0.29– 0.66) | 94.7 | 4 | 0.27 (0.14– 0.40) | 89.3 | 4 | 0.32 (0.22– 0.41) | 81.8 | 1 | 0.27 (0.22– 0.32) | − | |

| Participant groups | General population | 45 | 0.37 (0.33– 0.42) | 94.8 | 44 | 0.53 (0.46– 0.60) | 97.7 | 18 | 0.41 (0.34– 0.47) | 91.3 | 9 | 0.29 (0.22– 0.37) | 92.4 | 5 | 0.41 (0.30– 0.52) | 93.4 |

| Healthcare professionals | 4 | 0.68 (0.45– 0.92) | 95.2 | 4 | 0.67 (0.35– 0.99) | 96.5 | 1 | 0.76 (0.66– 0.86) | − | 1 | 1.28 (1.17– 1.38) | − | ||||

| Overall estimated Fisher's z-score | 49 | 0.40 (0.35– 0.44) | 95 | 48 | 0.54 (0.48– 0.61) | 97.6 | 19 | 0.42 (0.35– 0.50) | 92.6 | 9 | 0.29 (0.22– 0.37) | 92.4 | 6 | 0.56 (0.34– 0.77) | 98.5 | |

Table 5.

Meta-regression analysis for moderator analysis association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factor outcomes

| Number of studies | Coefficient | s.e. | P-value | I2 residual (%) | Adjusted R2 (%) | τ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Country | 49 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.69 | 95.11 | −1.99 | 0.04 |

| Age | 38 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.49 | 96.49 | −1.40 | 0.04 | |

| Newcastle–Ottawa Scale score | 49 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.61 | 95.06 | −1.67 | 0.04 | |

| Female % of participants | 48 | −0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.91 | 95.17 | −2.31 | 0.04 | |

| Measure of depression | 49 | −0.004 | 0.01 | 0.71 | 95.12 | −2.04 | 0.04 | |

| Anxiety | Country | 48 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.07 | 96.8 | 5.32 | 0.05 |

| Age | 35 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 95.27 | 15.54 | 0.04 | |

| Newcastle–Ottawa Scale score | 48 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 97.32 | 6.53 | 0.05 | |

| Female % of participants | 47 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.19 | 97.39 | 1.68 | 0.05 | |

| Measure of anxiety | 48 | −0.0001 | 0.009 | 1 | 97.57 | −2.27 | 0.05 | |

| Stress | Country | 17 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.71 | 92.99 | −5.25 | 0.02 |

| Age | 11 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.15 | 92.52 | 11.80 | 0.02 | |

| Newcastle–Ottawa Scale score | 17 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 91.62 | 15.51 | 0.02 | |

| Female % of participants | 17 | 0.0004 | 0.002 | 0.83 | 93 | −5.87 | 0.02 | |

| Measure of stress | 17 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.36 | 92.5 | −0.54 | 0.02 | |

| Sleep problems | Country | 9 | −0.0004 | 0.004 | 0.91 | 91.42 | −15.47 | 0.008 |

| Age | 5 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.11 | 50.18 | 63.58 | 0.002 | |

| Newcastle–Ottawa Scale score | 9 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.34 | 88.16 | 1.30 | 0.007 | |

| Female % of participants | 9 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.42 | 93.36 | −3.80 | 0.007 | |

| Measure of sleep problems | 9 | 0.009 | 0.02 | 0.61 | 92.15 | −12.75 | 0.008 | |

| Mental health-related factors | Country | 6 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 98.70 | −13.90 | 0.15 |

| Age | 4 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.73 | 99 | −39.93 | 0.26 | |

| Newcastle–Ottawa Scale score | 6 | −0.29 | 0.2 | 0.21 | 98.67 | 19.59 | 0.11 | |

| Female % of participants | 6 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.44 | 98.35 | −5.14 | 0.14 | |

| Measure of mental health-related factors | 6 | 0.87 | 0.14 | 0.003 | 93.38 | 89.68 | 0.01 | |

| Mental well-being | Country | 3 | −0.003 | 0.006 | 0.74 | − | − | − |

| Lockdown period | 3 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.68 | − | − | − | |

| Female % of participants | 3 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.67 | − | − | − | |

| Measure of mental well-being | 3 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.68 | − | − | − |

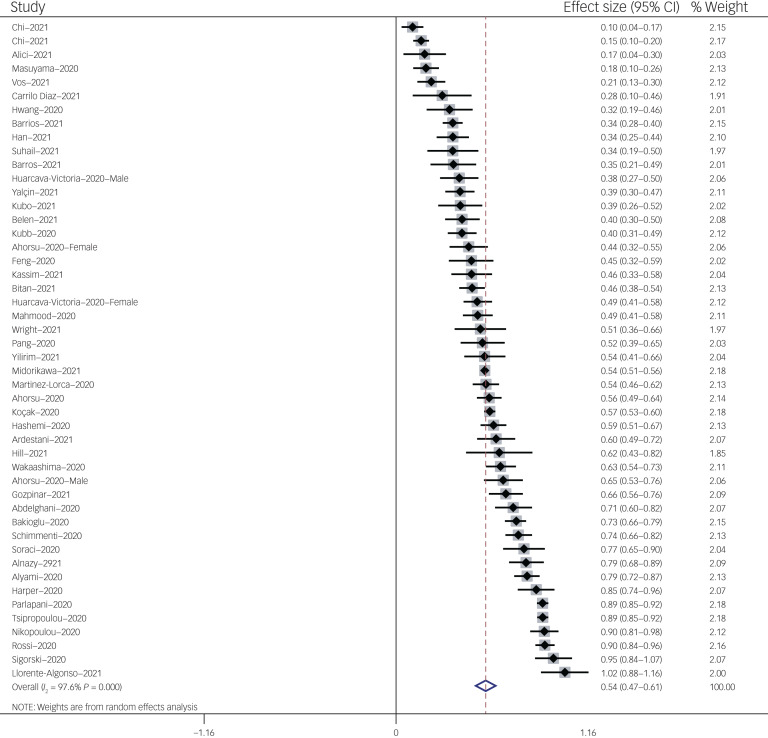

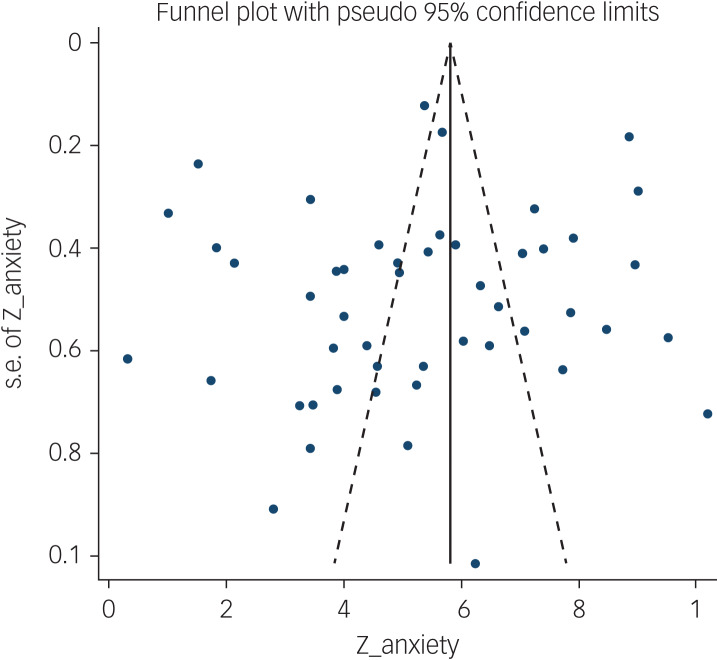

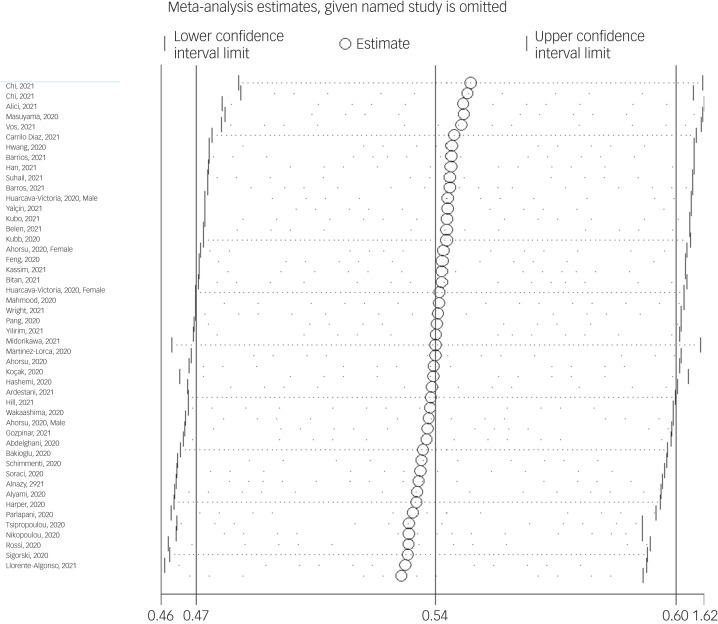

Association between fear of COVID-19 and anxiety

The association between fear of COVID-19 and anxiety was reported in 48 studies. The pooled estimated effect size showed strong correlation between fear of COVID-19 and anxiety, with a Fisher's z-score of 0.54 (95% CI 0.48–0.61, I2 = 97.6%, τ2 = 0.06). The forest plots are shown in Fig. 10. The probability of publication bias was assessed by Begg's test and funnel plot. Publication bias was not found in the association of fear of COVID-19 and anxiety based on Begg's test (P = 0.66) or funnel plot (Fig. 11). Sensitivity analysis showed that the pooled effect size was not affected by the single-study effect (P = 0.25; Fig. 12).

Fig. 10.

Forest plot displaying the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and anxiety.

Fig. 11.

Funnel plot assessing publication bias in studies regarding the association between fear of COVID-19 and anxiety.

Fig. 12.

Sensitivity analysis plot assessing small study effect in the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and anxiety.

Subgroup analysis showed that association between fear of COVID-19 and anxiety was positive and higher, but not significant, among healthcare professionals compared with the general population (0.67 v. 0.53), and during the lockdown period compared with not being lockdown (0.70 v. 0.53). Meta-regression showed that age was the only significant moderator in the association of COVID-19-related fear and anxiety, explaining 15.5% variance in this association. Other variables did not influence heterogeneity or estimated pooled Fisher's z-score. Results of the subgroup analysis and meta-regression are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

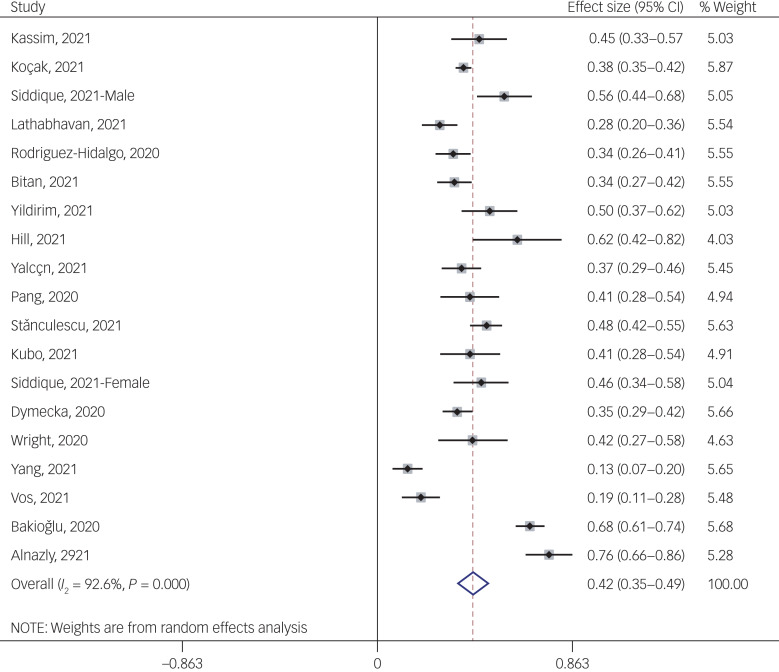

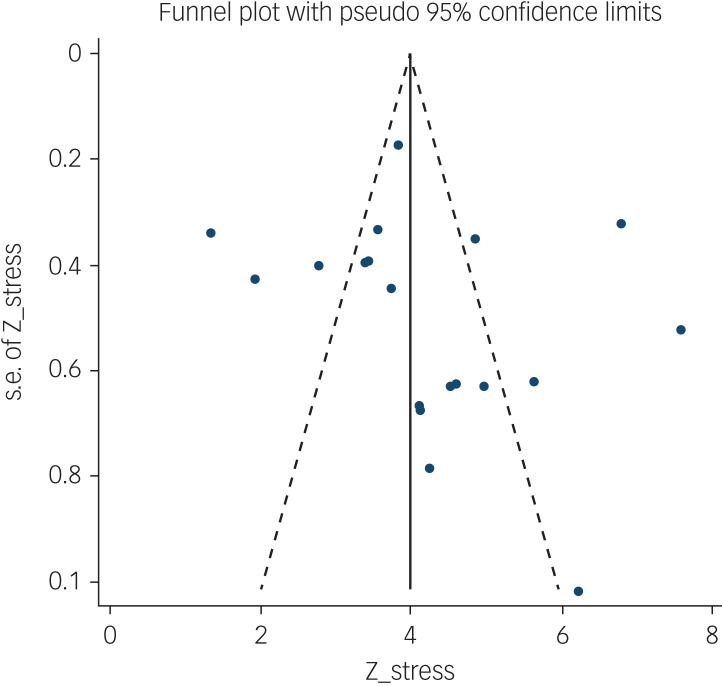

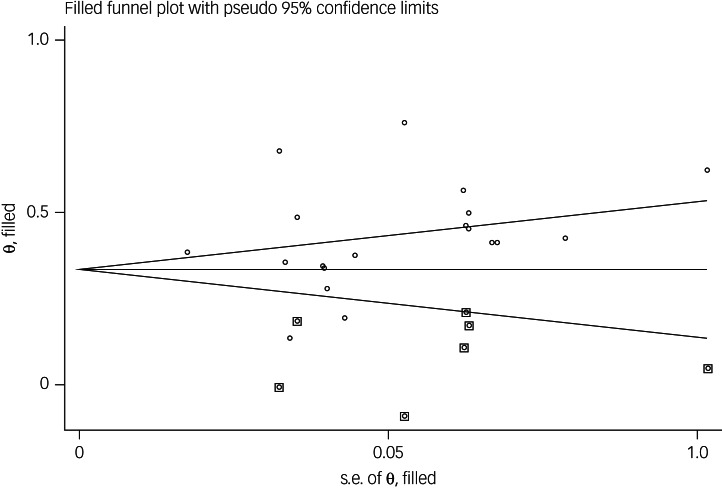

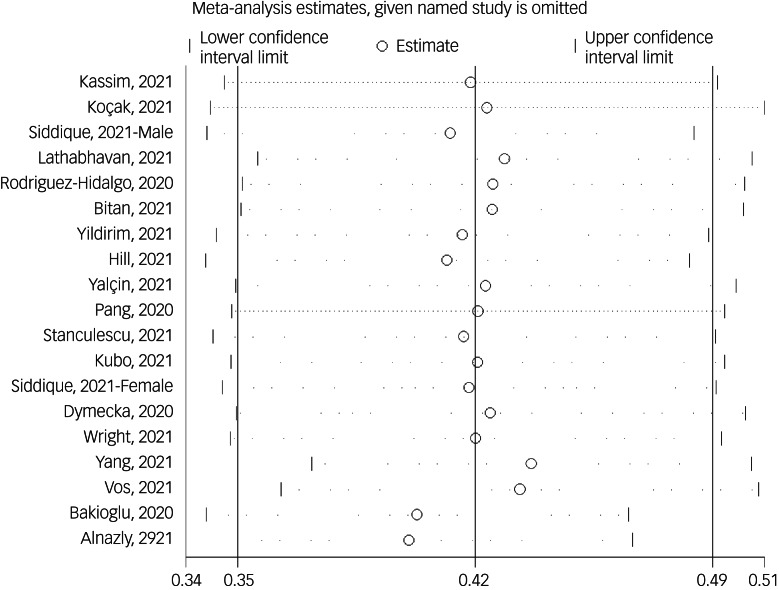

Association between fear of COVID-19 and stress

The association between fear of COVID-19 and stress was reported in 19 studies. The pooled estimated effect size showed moderate to strong association between fear of COVID-19 and stress, with a Fisher's z-score of 0.42 (95% CI 0.35–0.50, I2 = 92.6%, τ2 = 0.02). The forest plots are shown in Fig. 13. The probability of publication bias was assessed by Begg's test and funnel plot. Publication bias was not found in the association of fear of COVID-19 and stress based on Begg's test (P = 0.35), but was found in the funnel plot (Fig. 14). The fill-and-trim method was used to correct the results. In this method, seven studies were imputed, and the corrected results based on this method showed that pooled effect size of Fisher's z-score for association between fear of COVID-19 and stress was 0.34 (95% CI 0.26–0.41, P < 0.001). The funnel plot after trimming is shown in Fig. 15. Sensitivity analysis showed that the pooled effect size was not affected by the single-study effect (P = 0.42; Fig. 16).

Fig. 13.

Forest plot displaying the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and stress.

Fig. 14.

Funnel plot displaying the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and stress.

Fig. 15.

Corrected funnel plot assessing publication bias in the association between fear of COVID-19 and stress.

Fig. 16.

Sensitivity analysis plot assessing small study effect in the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and stress.

Subgroup analysis showed that lowest heterogeneity was observed in studies conducted during lockdown period (35.2%). Although it appears that association between fear of COVID-19 and stress was positive and higher in studies with female-only participants (0.62 v. 0.42 in studies that included both genders) and studies that used FCV-19S to measure fear of COVID-19 (0.47 v. 0.27 in studies that used other scales), it was not significant. Subgroup analysis showed that association between fear of COVID-19 and stress was significantly higher among healthcare professionals compared with the general population (0.76 v. 0.41). Meta-regression showed that age and methodological quality of studies were the significant moderators in the association of COVID-19-related fear and stress, explaining 11.8% and 15.51 variance, respectively, in this association. Other variables did not influence heterogeneity or estimated pooled Fisher's z-score. Results of the subgroup analysis and meta-regression are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

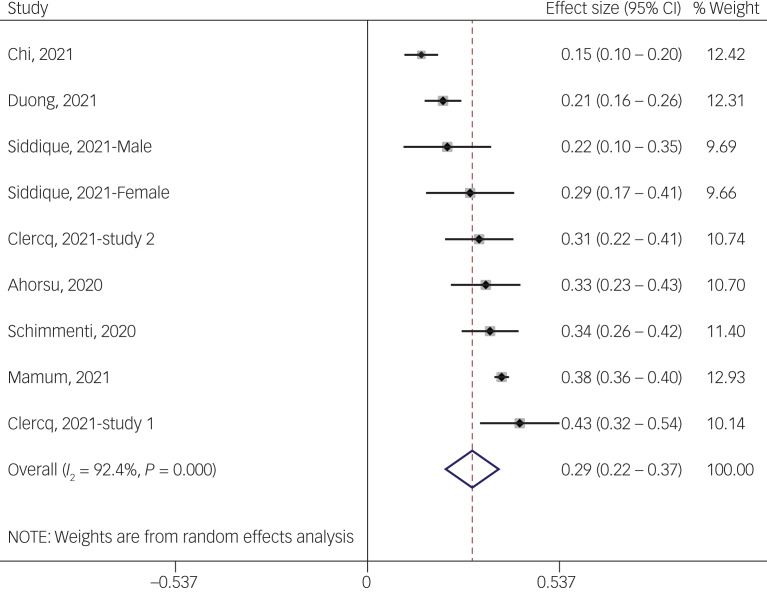

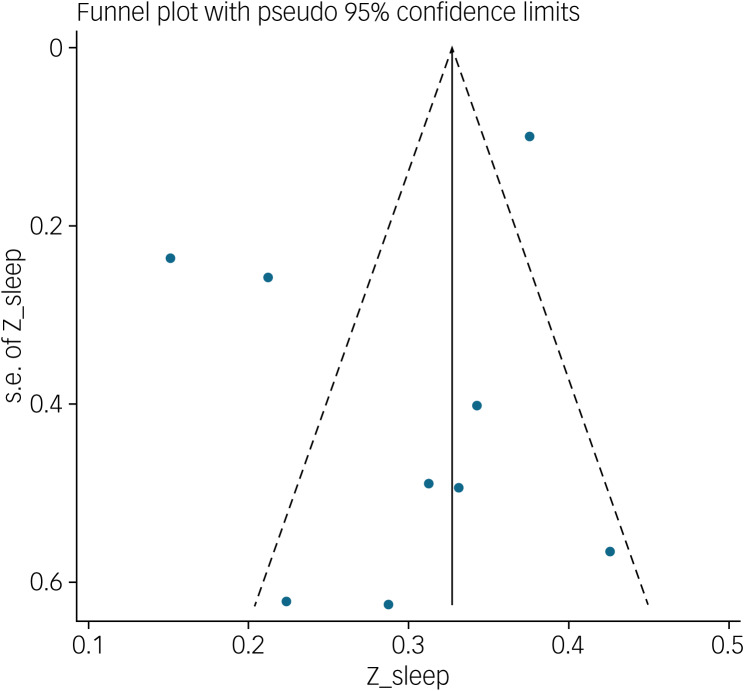

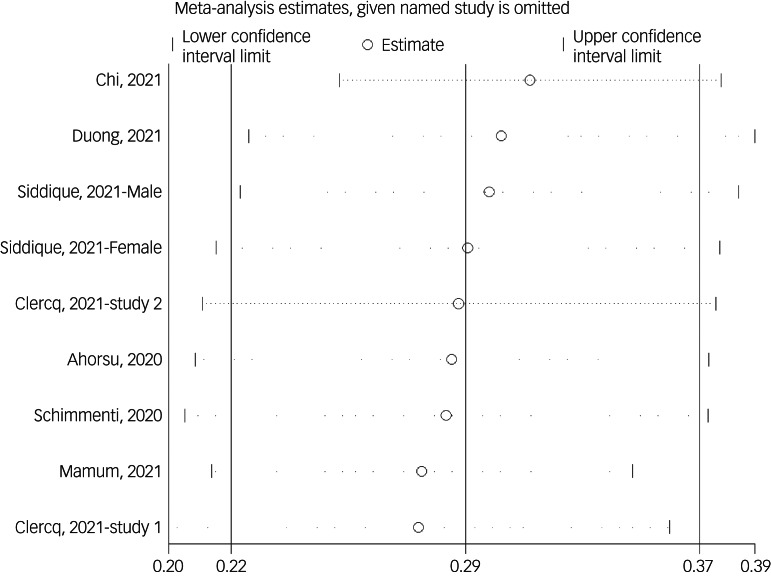

Association between fear of COVID-19 and sleep problems

The association between fear of COVID-19 and sleep problems was reported in nine studies. The pooled estimated effect size showed weak to moderate association between fear of COVID-19 and sleep problems, with Fisher's z-score of 0.29 (95% CI 0.22–0.37, I2 = 92.4%, τ2 = 0.01). The forest plots are shown in Fig. 17. The probability of publication bias was assessed by Begg's test and funnel plot. Publication bias was not found in the association of fear of COVID-19 and sleep problems based on Begg's test (P = 0.30) or funnel plot (Fig. 18). Sensitivity analysis showed that the pooled effect size was not affected by the single-study effect (P = 0.30; Fig. 19).

Fig. 17.

Forest plot displaying the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association fear of COVID-19 and sleep problems.

Fig. 18.

Funnel plot displaying the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and sleep problems.

Fig. 19.

Sensitivity analysis plot assessing small study effect in the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and sleep problems.

Meta-regression showed that age was the only significant moderator in the positive association of COVID-19-related fear and sleep problems, explaining 63.58% variance in this association. Other variables did not influence heterogeneity or estimated pooled Fisher's z-score. Results of the subgroup analysis and meta-regression are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

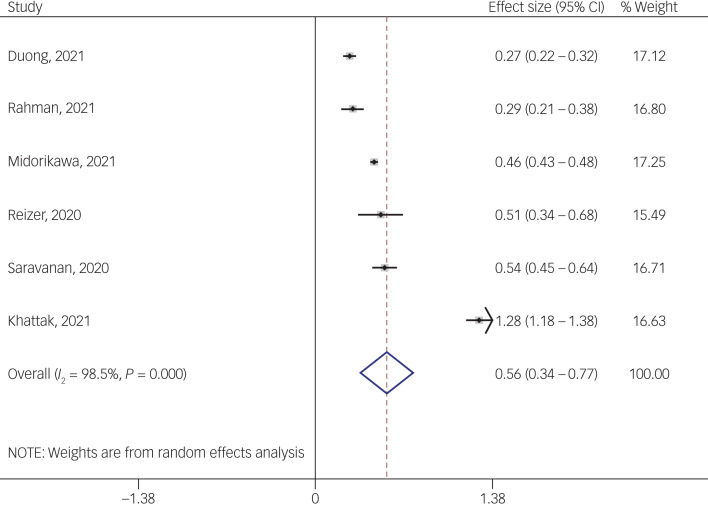

Association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors

The association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors was reported in six studies. The pooled estimated effect size showed strong association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors, with a Fisher's z-score of 0.56 (95% CI 0.34–0.77, I2 = 98.5%, τ2 = 0.07). The forest plots are shown in Fig. 20. The probability of publication bias was assessed by Begg's test and funnel plot. Publication bias was not found in the association of fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors based on Begg's test (P = 0.26), whereas the funnel plot appeared to be asymmetric (Fig. 21). The fill-and-trim method was used to correct the results. In this method, one study was imputed and the corrected results based on this method showed that pooled effect size of Fisher's z-score for the association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors was 0.42 (95% CI 0.16–0.67, P < 0.001). The funnel plot after trimming is shown in Fig. 22. Sensitivity analysis showed that the pooled effect size was not affected by the single-study effect (P = 0.58; Fig. 23).

Fig. 20.

Forest plot displaying the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors. Arrow indicates that the CI does not fit the range of the x-axis.

Fig. 21.

Funnel plot displaying the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors.

Fig. 22.

Corrected funnel plot assessing publication bias in the association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors.

Fig. 23.

Sensitivity analysis plot assessing small study effect in the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors.

Subgroup analysis showed that association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors was significantly higher among healthcare professionals (1 v. 0.41 for the general population). Such associations were also higher among studies that used FCV-19S to assess fear of COVID-19 (0.62 v. 0.27 in studies using other scales). Meta-regression showed that methodological quality score and instrument used to assess mental health-related factors explained 19.59% and 89.68% variance in this positive association. Other variables did not influence heterogeneity or estimated pooled Fisher's z-score. Results of the subgroup analysis and meta-regression are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

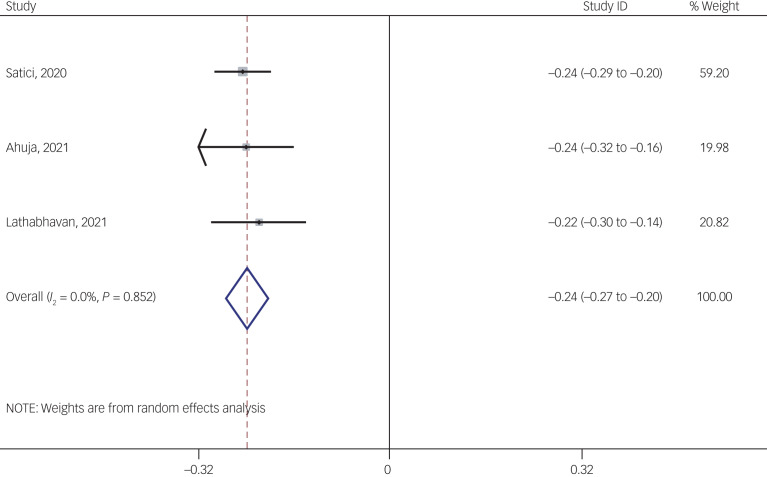

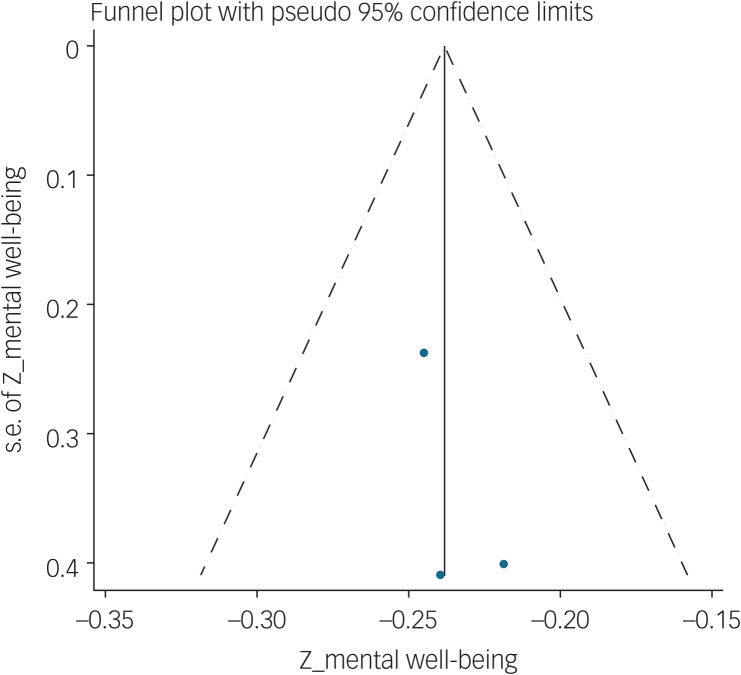

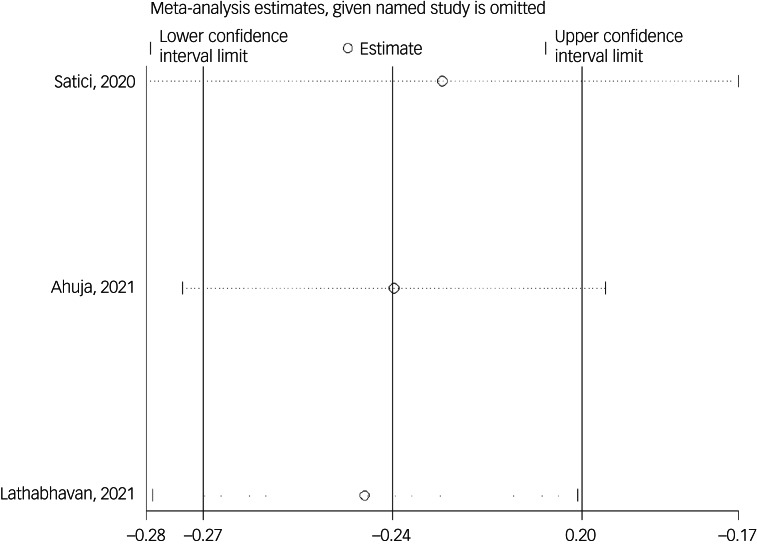

Association between fear of COVID-19 and mental well-being

The association of fear of COVID-19 with mental well-being was reported in three studies. The pooled estimated effect size showed negative and weak to moderate association between fear of COVID-19 and mental well-being, with a Fisher's z-score of −0.24 [95% CI −0.27 to −0.20, I2 = 0, τ2 = 0). The forest plots are shown in Fig. 24. The probability of publication bias was not found in the funnel plot (Fig. 25). Sensitivity analysis showed that pooled effect size was not affected by the single-study effect (P = 0.47; Fig. 26). Variables did not influence heterogeneity or estimated pooled Fisher's z-score. Results of the subgroup analysis and meta-regression are shown in Tables 4 and 5. Moreover, Table 6 summarises the pooled effect sizes for each studied variable associated with fear of COVID-19.

Fig. 24.

Forest plot displaying the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association fear of COVID-19 and mental well-being.

Fig. 25.

Funnel plot displaying the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and mental well-being.

Fig. 26.

Sensitivity analysis plot assessing small study effect in the estimated pooled Fisher's z-score in the association between fear of COVID-19 and mental well-being.

Table 6.

Pooled effect sizes for studied factors correlated with fear of COVID-19

| Fisher's z-score | 95% CI | I2 | τ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 0.40 | 0.35–0.44 | 95% | 0.02 |

| Anxiety | 0.54 | 0.48–0.61 | 97.6% | 0.06 |

| Stress | 0.42 | 0.35–0.50 | 92.6% | 0.02 |

| Sleep problems | 0.29 | 0.22–0.37 | 92.4% | 0.01 |

| Mental health-related factors | 0.56 | 0.34–0.77 | 98.5% | 0.07 |

| Mental well-being | −0.24 | −0.27 to −0.20 | 0.0% | 0.00 |

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present systematic review and meta-analysis is the first to analyse the associations between fear of COVID-19 and a variety of mental health-related factors. More specifically, the systematic review and meta-analysis synthesised the evidence on the associations between fear of COVID-19 and depression, anxiety, stress, sleep problems, mental health-related factors and mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic period. After rigorous literature search, full texts of 298 papers were reviewed and 91 studies were included in the meta-analysis. Among the 91 studies, data from 88 320 participants in 36 countries were analysed. Moreover, the present meta-analysis showed that the mean estimation of fear of COVID-19 (using the FCV-19S) was 13.11, which indicates low levels of fear. More specifically, the score range of the fear was between 7 and 35, with a score of <21 indicating a low level of fear. Moreover, no significant gender differences were found in the fear of COVID-19.

The association between fear of COVID-19 and depression was moderate to strong (Fisher's z = 0.40), and a stronger association was observed among healthcare professionals (0.68) compared with the general population (0.37). The association between fear of COVID-19 and anxiety was strong (Fisher's z = 0.54), and no significant difference in the magnitude of association was found between healthcare professionals (0.67) and the general population (0.53). The association between fear of COVID-19 and stress was moderate to strong (Fisher's z = 0.42), and a stronger association was observed among healthcare professionals (0.76) compared with the general population (0.41). The association between fear of COVID-19 and sleep problems was weak to moderate (Fisher's z = 0.29). The association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health-related factors was strong (Fisher's z = 0.56), and a stronger association was observed among healthcare professionals (1 v. 0.41 for the general population) The association between fear of COVID-19 and mental well-being was weak to moderate (Fisher's z = −0.27). Meta-regression further showed that country, age, study quality, gender and measures for mental health-related factors were mostly non-significant moderators. Significant moderated effects were identified for age in anxiety and instruments on mental health-related factors (Table 5).

According to the meta-analysis results, fear of COVID-19 appears to contribute to mental health problems across different types, including depression, anxiety, stress, sleep problems, mental health-related factors and impaired mental well-being. However, the present findings were based on cross-sectional designs, which can only provide evidence of association rather than causality. Nevertheless, prior evidence and theories have supported that fear is a trigger for different types of mental health problems.136–138 Therefore, it can be tentatively concluded that fear of COVID-19 may lead to mental health-related problems based on the moderate associations found in the present meta-analysis. Furthermore, the associations found between fear of COVID-19 and other mental health-related factors appeared to be higher among healthcare professionals than individuals in the general population. This can be explained by the high levels of risk that healthcare professionals have been exposed to during the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, the workplaces of healthcare professionals are usually hospitals, and their jobs do not allow them to work from home. Therefore, they are likely to be exposed to environments with a much higher risk of COVID-19 infection than the work environments of the general population.33,139 Moreover, healthcare professionals usually have irregular work schedules, which may contribute to their mental health problems.140–142 Therefore, the association between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems may be elevated when healthcare professionals are vulnerable in their mental health.

The instruments used for assessing fear of COVID-19 and other mental health-related factors are reported in Table 1. Diverse and inconsistent psychometric instruments were used for mental health-related factors in these studies. However, most of the studies used the FCV-19S to assess fear of COVID-19. The FCV-19S is a promising and robust instrument that has strong psychometric properties.143,144 Moreover, the FCV-19S45 contains only seven items, which is more practical to use in a busy setting, and provides accurate estimates of fear of COVID-19 in a short time (<5 mins). The FCV-19S has been validated in over 20 different languages.143,144 Therefore, it appears to be the most appropriate instrument assessing fear of COVID-19 for almost all of the studies reviewed in the present systematic review and meta-analysis. Future studies are recommended to use the FCV-19S if they want to assess the phenomenon of fear of COVID-19.

According to the findings derived from the present systematic review and meta-analysis, there are a number of implications. First, programmes to reduce fear of COVID-19, especially for healthcare professionals, are recommended during the pandemic period. More specifically, programmes with the support of strong theory (e.g. cognitive–behavioural therapy and meditation145,146) can be designed to tackle fear of COVID-19, and these may subsequently help maintain good mental health among both healthcare professionals and the general population during COVID-19 pandemic. Second, the associations between fear of COVID-19 and other mental health-related factors found in the present systematic review and meta-analysis indicate the importance of addressing the fear of COVID-19 together with other mental health-related factors. This may increase the effects of mental health improvement programmes during the pandemic. However, it should be noted that the present systematic review and meta-analysis found a large I2-value, which indicates the high levels of heterogeneity among the studies evaluated. However, large heterogeneity observed in the present findings is understandable because various factors that can increase the fear of COVID-19 together with the wide range of populations and measures were included in the meta-analysis.

Strengths and limitations

There are some strengths in the present systematic review and meta-analysis. First, the mean estimation of fear of COVID-19 and its associations with other mental health-related factors were estimated across different countries worldwide. Therefore, the analysis provides a contextualised picture regarding the psychological phenomenon during the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, the methodology of the present systematic review and meta-analysis was rigorous, given that each analysed study had been evaluated for their methodological quality by the NOS checklist. Moreover, a thorough literature review was conducted utilising five academic databases. In addition to the main and secondary outcomes, the synthesised findings were checked for their stability by additional analyses, including subgroup analysis and meta-regression. Third, the present findings have relatively high generalisability because the analysed data come from a large sample size (N = 88 320) across 36 countries.

There are also some limitations in the present systematic review and meta-analysis. First, fear of COVID-19 and other mental health-related factors analysed in the present meta-analysis were assessed by different psychometric instruments across the studies (e.g. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale). Therefore, the different item descriptions and scoring method used in these measures may cause biases in estimation. However, meta-regression in the present systematic review and meta-analysis shows that almost all of the measures had no significant effects on the synthesised results. Therefore, this limitation may not be serious. Second, all studies, except for one, that were analysed in the present systematic review and meta-analysis employed a cross-sectional design. Without the time factor in the study design, the associations found in the present findings do not have strong causal evidence in relation to the variables under investigation. Therefore, future studies using longitudinal designs are warranted to provide additional evidence in more rigorously exploring the causal relationships between fear of COVID-19 and other mental health-related factors. Third, although the present systematic review and meta-analysis analysed 91 studies, only three of them46,118,126 assessed the associations between fear of COVID-19 and mental well-being. Therefore, further studies are needed to corroborate the evidence regarding the association between fear of COVID-19 and mental well-being.

In conclusion, the present study found that the fear of COVID-19 had associations with a variety of mental health-related factors, from slightly weak to relatively strong magnitudes. Moreover, healthcare professionals, as compared with the general population, had stronger magnitudes in the associations between fear of COVID-19 and some mental health-related factors (including depression, stress and mental health-related factors). Therefore, programmes on reducing fear of COVID-19 and improving mental health for both healthcare professionals and the general population are warranted during the ongoing pandemic.

Author contributions

Z.A. and A.H.P. contributed to the conception, design of the study and data collection. Z.A. and A.H.P. contributed to data analysis and interpretation of data. Z.A., C.-Y.L. and A.H.P. drafted the manuscript. M.M.O., M.D.G. and C.-Y.L. provided contributions to the literature review and discussion, and substantially edited the primary manuscript. A.H.P. prepared the final version of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript, agreed to be fully accountable for ensuring the integrity and accuracy of the study, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published. All of the authors met the criteria for authorship, and are listed as co-authors on the title page. A.H.P. and C.-Y.L. contributed equally to the study.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Declaration of interest

None.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. World Health Organization, 2021. (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abedi V, Olulana O, Avula V, Chaudhary D, Khan A, Shahjouei S, et al. Racial, economic, and health inequality and COVID-19 infection in the United States. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2021; 8: 732–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jungreis I, Sealfon R, Kellis M. SARS-CoV-2 gene content and COVID-19 mutation impact by comparing 44 sarbecovirus genomes. Nat Commun 2021; 12: 2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data, 2020. (https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Tenchov R, Smoot J, Liu C, Watkins S, Zhou Q. A comprehensive review of the global efforts on COVID-19 vaccine development. ACS Cent Science 2021; 7: 512–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yahaghi R, Ahmadizade S, Fotuhi R, Taherkhani E, Ranjbaran M, Buchali Z, et al. Fear of COVID-19 and perceived COVID-19 infectability supplement theory of planned behavior to explain Iranians’ intention to get COVID-19 vaccinated. Vaccines 2021; 9: 684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen I-H, Ahorsu DK, Ko N-Y, Yen CF, Lin CY, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH, et al. Adapting the Motors of Influenza Vaccination Acceptance Scale into the Motors of COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance Scale: psychometric evaluation among mainland Chinese university students. Vaccine 2021; 39(32): 4510–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan C-W, Chen I-H, Ko N-Y, Yen CF, Lin CY, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH, et al. Extended theory of planned behavior in explaining the intention to COVID-19 vaccination uptake among mainland Chinese university students: an online survey study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17(10): 3413–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kukreti S, Lu M-Y, Lin Y-H, Strong C, Lin CY, Ko NY, et al. Willingness of Taiwan's healthcare workers and outpatients to vaccinate against COVID-19 during a period without community outbreaks. Vaccines 2021; 9: 246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alijanzadeh M, Harati T. The role of social capital in the implementation of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Soc Health Behav 2021; 4: 45. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashraf A, Ali I, Ullah F. Domestic and gender-based violence: Pakistan scenario amidst COVID-19. Asian J Soc Health Behav 2021; 4: 47. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwok C, Leung PY, Poon KY, Fung XC. The effects of internet gaming and social media use on physical activity, sleep, quality of life, and academic performance among university students in Hong Kong: a preliminary study. Asian J Soc Health Behav 2021; 4: 36. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen C-Y, Chen I-H, Pakpour AH, Lin C-Y, Griffiths MD. Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during the COVID-19 school hiatus. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2021; 24(10); 654–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen I-H, Chen C-Y, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Lin CY, Li XD, et al. Problematic internet-related behaviors mediate the associations between levels of internet engagement and distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 lockdown: a longitudinal structural equation modeling study. J Behav Addict 2021; 10: 135–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen I-H, Chen C-Y, Liu C-h, Ahorsu DK, Griffiths MD, Chen YP, et al. Internet addiction and psychological distress among Chinese schoolchildren before and during the COVID-19 outbreak: a latent class analysis. J Behav Addict 2021; 10(3): 731–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu M-Y, Ahorsu DK, Kukreti S, Strong C, Lin YH, Kuo YJ, et al. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, sleep problems, and psychological distress among COVID-19 frontline healthcare workers in Taiwan. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12: 705657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patil ST, Datar MC, Shetty JV, Naphade NM. “Psychological consequences and coping strategies of patients undergoing treatment for COVID-19 at a tertiary care hospital”: a qualitative study. Asian J Soc Health Behav 2021; 4: 62. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajabimajd N, Alimoradi Z, Griffiths MD. Impact of COVID-19-related fear and anxiety on job attributes: a systematic review. Asian J Soc Health Behav 2021; 4: 51–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nkwayep CH, Bowong S, Tewa J, Kurths J. Short-term forecasts of the COVID-19 pandemic: a study case of Cameroon. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020; 140: 110106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pak A, Adegboye OA, Adekunle AI, Rahman KM, McBryde ES, Eisen DP. Economic consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak: the need for epidemic preparedness. Front Public Health 2020; 8: 241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gianaros PJ, Wager TD. Brain-body pathways linking psychological stress and physical health. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2015; 24: 313–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamang A, Eide GE, Rokne B, Nordin K, Øyen N. General anxiety, depression, and physical health in relation to symptoms of heart-focused anxiety-a cross sectional study among patients living with the risk of serious arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011; 9: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadeh A, Keinan G, Daon K. Effects of stress on sleep: the moderating role of coping style. Health Psychol 2004; 23: 542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Ohayon MM, Broström A, Lin C-Y. A good sleep: the role of factors in psychosocial health. Front Neurosci 2020; 14: 520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Grégoire J-P, Savard J. The economic burden of insomnia: direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep 2009; 32: 55–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lubetkin EI, Jia H. Burden of disease due to sleep duration and sleep problems in the elderly. Sleep Health 2018; 4: 182–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobocki P, Lekander I, Borgström F, Ström O, Runeson B. The economic burden of depression in Sweden from 1997 to 2005. Eur Psychiatry 2007; 22: 146–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alimoradi Z, Pakpour A. Fear of COVID-19: Measurement Properties of the Scale and its Relation with Psychological Distress. International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, 2020. (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=188890).

- 29.Page MJ, Moher D, Fidler FM, Higgins J, Brennan SE, Haddaway NR, et al. The REPRISE project: protocol for an evaluation of reproducibility and replicability in syntheses of evidence. Syst Rev 2021; 10: 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD. The fear of COVID-19 and its role in preventive behaviors. J Concurr Disord 2020; 2: 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Psychiatric Association D and Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selye H. Stress in Health and Disease. Butterworths, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alimoradi Z, Broström A, Tsang HW, Griffiths MD, Haghayegh S, Ohayon MM, et al. Sleep problems during COVID-19 pandemic and its’ association to psychological distress: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 36: 100916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ridner SH. Psychological distress: concept analysis. J Adv Nur 2004; 45: 536–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fen CM, Isa I, Chu CW, Ling C, Ling SY. Development and validation of a mental wellbeing scale in Singapore. Psychology 2013; 4: 592. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luchini C, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Veronese N. Assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses: advantages and limitations of the Newcastle Ottawa scale. World J Meta Anal 2017; 5: 80–4. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hox JJ, Leeuw ED. Multilevel models for meta-analysis. In Multilevel Modeling: Methodological Advances, Issues, and Applications (eds Reise SP, Duan N): 90–111. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I² index? Psychol Methods 2006; 11: 193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-Analysis. Sage Publications, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alimoradi Z, Golboni F, Griffiths MD, Broström A, Lin C-Y, Pakpour AH. Weight-related stigma and psychological distress: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr 2019; 39(7): 2001–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M. Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments. John Wiley & Sons, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hedges L, Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Academic Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller RG. The jackknife - a review. Biometrika 1974; 61: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahorsu DK, Lin C-Y, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lathabhavan R, Vispute S. Examining the mediating effects of stress on fear of COVID-19 and well-being using structural equation modeling. Int J Ment Health Addict 2021: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siddique RF, Ahmed O, Hossain KN. Relationship between the fear of COVID-19 disease and sleep quality: the mediating role of stress. Heliyon 2021; 7: e07033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Rahimi JS, Nass NM, Hassoubah SA, Wazqar DY, Alamoudi SA. Levels and predictors of fear and health anxiety during the current outbreak of COVID-19 in immunocompromised and chronic disease patients in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional correlational study. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0250554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carrillo-Diaz M, Lacomba-Trejo L, Del Valle-González A, Romero-Maroto M, González-Olmo MJ. Anxiety and facial self-contacts: possible impact on COVID-19 transmission in dental practice. BMC Oral Health 2021; 21: 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ardestani SMS, Khosravani V, Bastan FS, Baloğlu M. The Persian version of the COVID-19 Phobia Scale (Persian-C19P-S) and the differences in COVID-19-related phobic reactions in patients with anxiety disorders. Int J Ment Health Addict 2021: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mumtaz A, Manzoor F, Jiang S, Anisur Rahaman M. COVID-19 and mental health: a study of stress, resilience, and depression among the older population in Pakistan. Healthcare 2021; 9: 424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yalçın İ, Can N, Mançe Çalışır Ö, Yalçın S, Çolak B. Latent profile analysis of COVID-19 fear, depression, anxiety, stress, mindfulness, and resilience. Curr Psychol 2021; 41: 459–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang C, Chen A, Chen Y. College students’ stress and health in the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of academic workload, separation from school, and fears of contagion. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0246676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rahman MA, Salehin M, Islam SMS, Alif SM, Sultana F, Sharif A, et al. Reliability of the tools used to examine psychological distress, fear of COVID-19 and coping amongst migrants and non-migrants in Australia. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2021; 30: 747–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Majeed M, Irshad M, Fatima T, Khan J, Hassan MM. Relationship between problematic social media usage and employee depression: a moderated mediation model of mindfulness and fear of COVID-19. Front Psychol 2020; 11: 3368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kubb C, Foran HM. Measuring COVID-19 related anxiety in parents: psychometric comparison of four different inventories. JMIR Ment Health 2020; 7: e24507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alyami M, de Albuquerque JV, Krägeloh CU, Alyami H, Henning MA. Effects of fear of COVID-19 on mental well-being and quality of life among Saudi adults: a path analysis. Saudi J Med Sci 2021; 9: 24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alyami M, Henning M, Krägeloh CU, Alyami H. Psychometric evaluation of the Arabic version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020; 19: 2219–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodríguez-Hidalgo AJ, Pantaleón Y, Dios I, Falla D. Fear of COVID-19, stress, and anxiety in university undergraduate students: a predictive model for depression. Front Psychol 2020; 11: 591797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan L, Gan Y, Ding X, Wu J, Duan H. The relationship between perceived stress and emotional distress during the COVID-19 outbreak: effects of boredom proneness and coping style. J Anxiety Disord 2021; 77: 102328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahorsu DK, Lin C-Y, Pakpour AH. The association between health status and insomnia, mental health, and preventive behaviors: the mediating role of fear of COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med 2020; 6: 2333721420966081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sigorski D, Sobczuk P, Osmola M, Kuć K, Walerzak A, Wilk M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on anxiety levels among patients with cancer actively treated with systemic therapy. ESMO Open 2020; 5: e000970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hashemi SGS, Hosseinnezhad S, Dini S, Griffiths MD, Lin C-Y, Pakpour AH. The mediating effect of the cyberchondria and anxiety sensitivity in the association between problematic internet use, metacognition beliefs, and fear of COVID-19 among Iranian online population. Heliyon 2020; 6: e05135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Labrague LJ, de Los Santos JAA. Fear of COVID-19, psychological distress, work satisfaction and turnover intention among frontline nurses. J Nurs Manag 2021; 29: 395–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salehi L, Rahimzadeh M, Molaei E, Zaheri H, Esmaelzadeh-Saeieh S. The relationship among fear and anxiety of COVID-19, pregnancy experience, and mental health disorder in pregnant women: a structural equation model. Brain Behav 2020; 10: e01835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feng S, Zhang Q, Ho SM. Fear and anxiety about COVID-19 among local and overseas Chinese university students. Health Soc Care Commun 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barros M, Aguiar MM, Carvalho F, Macedo A, Pereira AT. COVID-19 fear scale-validation and adaptation for the perinatal period. J Hum Growth Dev 2021; 31: 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wakashima K, Asai K, Kobayashi D, Koiwa K, Kamoshida S, Sakuraba M. The Japanese version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale: reliability, validity, and relation to coping behavior. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0241958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rahman MA, Hoque N, Alif SM, Salehin M, Islam SMS, Banik B, et al. Factors associated with psychological distress, fear and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Global Health 2020; 16: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duong CD. The impact of fear and anxiety of Covid-19 on life satisfaction: psychological distress and sleep disturbance as mediators. Pers Individ Dif 2021; 178: 110869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]