Abstract

Purpose of Review

While research has identified racial trauma in other contexts, it is often overlooked amongst Canadian society. Racial trauma occurs as a result of an event of racism or cumulative events over time whereby an individual experiences stress and consequent mental health sequelae. Given that the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and/or Person of Colour) population in Canada is increasing, it is imperative to identify racial discrimination and the subsequent stress and trauma associated with being racialized in Canada, which subjects BIPOC Canadians to various forms of racism, including microaggressions.

Recent Findings

This paper reviews the published literature on racism and racial discrimination that identifies or infers racial trauma as the source of the mental health implications for various groups (e.g., Indigenous people, Black Canadians, Asian Canadians, immigrants, and refugees). In addition, intersectionality of racialized persons is prominent to their psychological well-being as their psychosocial and socioeconomic position are complex. Therefore, this paper both provides insight into the Canadian experience as a person of colour and signifies the need for further research on racial trauma in a Canadian context.

Summary

Despite Canada’s emphasis on multiculturalism, racialized individuals are at risk for racial trauma due to prejudice and discrimination. The politicization of multiculturalism has permitted Canada to deny claims of racism, yet the historical basis of established institutions results in irrefutable systemic and systematic barriers for Canadian people of colour.

Keywords: Discrimination, Racism, Racial trauma, Canadians of colour, Microaggressions, Intersectionality

Introduction

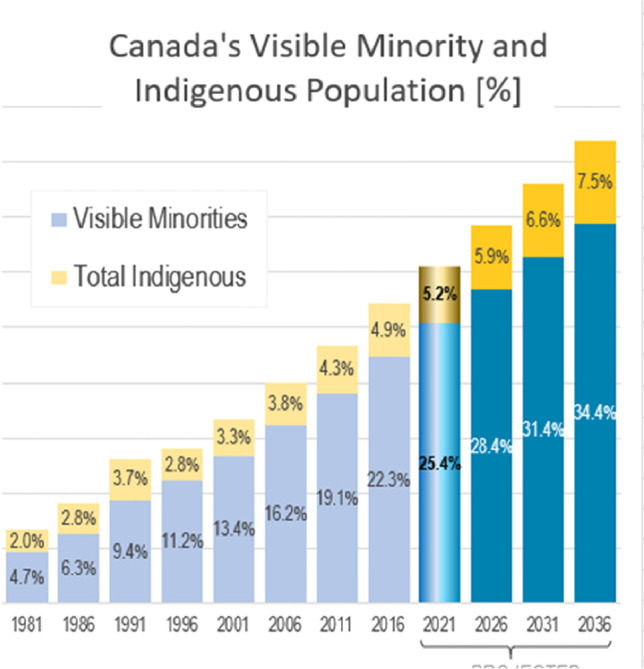

Canada promotes itself as a multicultural country, emphasizing the value of racial, ethnic, language, and religious diversity [1]. As such, Canada has been celebrated as an ideal inclusive nation, yet this fails to take into account the actual lived experiences of the 11.5 million persons of colour and indigenous persons who make up nearly 30% of all Canadians (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Canada’s visible minority and indigenous population (%). Note: The figure represents the proportion of people of colour in the Canadian population and future projections

Canadian society is often considered to be “colourblind” meaning it does not see or take race into consideration. Many Canadians describe themselves as egalitarian, tolerant, and diversity minded. As a whole, none of this is true [2–4]. Canadian society is actually quite racist, and even the preferred “colourblind” approach is itself racist, as it fails to recognize the differing lived experiences of people of colour. Racialized Canadians (visible minorities and Indigenous people) experience differential treatment by dominant members within Canadian society and sometimes even from other people of colour. Furthermore, because of the false discourse of multiculturalism, Canadian politicians have tended to validate their insouciance towards reports of racism made by Black, Indigenous, and other people of colour (BIPOC) [5, 6].

With regard to race, Canadians tend to view the USA as a racist country and Canada as non-racist [5], but this belief can only be true if acts of colonial and contemporary racism are “ignored, minimized, or denied” [7], p. 3. In general, White Canadians are neither sufficiently aware of their settler colonial history and its legacies nor the diversity of what constitutes Canadian people [7]. Racism is embedded in the history of Canada as demonstrated by legal slavery, the Chinese Head tax, colonialism, Residential Schools, the Komagata Maru, WWII Japanese internment camps, and the destruction of Africville. Racism continues to exist at both individual and structural levels in current Canadian society [2], as evidenced by racial profiling of Black Canadians by law enforcement, maltreatment of Indigenous people, forced sterilization, anti-Asian violence, and other ongoing acts of violence. In addition to these overt acts of racism, Canadians also have implicit biases, as shown in a preliminary study using the Implicit Associations Test (IAT), which found equal levels of anti-Black bias amongst White Canadians compared to White Americans and White Europeans [8].

Much of the research on the impacts of racism has been conducted in the USA and applied to the Canadian context. This has been necessary because there is a significant and problematic gap in Canadian literature, starting with the fact that race-based statistics only recently started being collected e.g., [9, 5, 10, 11, 12, 13, 3, 14]. We know from American, Australian, and British research that racism has significant mental health impacts on people of colour [5, 15]. However, there remains a dearth of systematic and research-based information available on the impact on Canadian people of colour. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to present an overview of the mental health impact of racism based on the literature to date, specifically how PTSD and racial trauma manifest in Canadians of colour.

Defining Racism

In order to fully understand the mental health impacts of racism, it is important to underscore that there are different types of racism which can occur in various ways. Thus, we will define racism and its various manifestations within Canadian structures and society.

Racism is a system of beliefs (racial prejudices), practices (racial discrimination), and policies based on individuals’ presumed race, which operates to advantage those with historical power in most Western nations including White people in the USA and Canada. In the USA and Canada, race operates as a social caste system used to categorize people based on shared physical and social features [16]. Even though an individual may be a racialized minority or Indigenous person, they can still harbour racism. This is because our culture of racism affects all who have been socialized within it from childhood, and eventually racist thought patterns seem normal [17].

Dominative racism refers to “old-fashioned racism,” consisting of beliefs and acts of bigotry such as racial slurs, threats, and acts of racial brutality. Symbolic racism, also known as “modern racism,” or “right-wing racism,” consists of negative attitudes and stereotypes about people of colour; examples include viewing them as inferior, lazy, or having criminal or aggressive tendencies. Aversive racism, also known as “left-wing racism,” is characterized by claiming support for racial equality and justice, while holding implicit conflicted negative feelings towards people of colour, and acting in ways that are racist. Internalized racism is a form of racism where people of colour hold negative views of other people of colour and value being “White,” adopt attributes associated with being White, and distance themselves from their racial group, often preferring to socialize with White people [16].

Everyday racism refers to unrecognized and unacknowledged acts of racism that occur in day-to-day situations through cognitive and behavioural practices that reinforce power relations [18]. Similar to everyday racism are microaggressions—common statements, actions, or environmental indignities and assaults, either intentional or unintentional, that convey “hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color” [19], p. 1. These often tend to be subtle, sometimes ambiguous, and deniable; have a cumulative impact; and are associated with negative mental health outcomes [18].

Structural racism refers to the system of institutional and public policies and practices that serve to maintain racial inequities and disadvantage people of colour [20, 21]. It is embedded in social systems which have been structured in ways that limit the ability of people of colour to access social, educational, economic, and political opportunities [22]. Thus, racism is not simply about acts of prejudice and violence committed by individuals against people of colour, but it is also organized in structures and societies within which people of colour live and aspire for their goals, operating in the form of barriers and inequities which are often unacknowledged.

These many different types of racism are experienced by people of colour, with cumulative effects that can contribute to traumatization [23–26]. Experiencing racial discrimination is proposed to be one factor in accounting for the higher rates of PTSD, also referred to as racial trauma, in people of colour [26, 27]. Racial trauma (also referred to as race-based traumatic stress) is the cumulative effects of racism on a person’s mental health. It consists of reactions to direct or vicarious exposure to real or perceived threats, experiences of humiliation and shame, and racial discrimination towards people of colour [28]. Racial trauma is associated with phenomena such as anxiety, depression, despair, suicidal ideation, and poor physical health [26, 29].

The Mental Health Impact of Racism

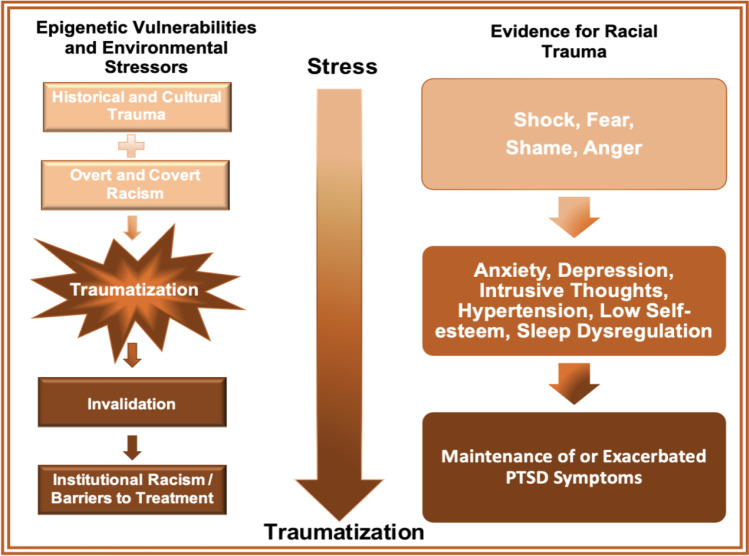

A model adapted from Williams and colleagues [26] explains how the cumulative effects of racism can lead to PTSD (Fig. 2). According to this model, predispositions of vulnerability, such as epigenetic risk factors from historical or cultural trauma or racial oppression, set up a stress base, which is exacerbated by cumulative experiences of overt and covert racism. If individuals are the targets of racially traumatic events, they will experience emotions associated with this event such as shock, fear, or anger. Furthermore, if these experiences are invalidated, these individuals may develop symptoms of PTSD such as intrusive thoughts, avoidance, hypervigilance, and negative changes in mood and cognitions. Finally, due to institutional racism and barriers to treatment, professional help may not be accessible, which maintains or worsens the symptoms of PTSD. This could take the form of lack of awareness by health care professionals and their discomfort with addressing issues of race, leaving racial PTSD/ trauma untreated [30].

Fig. 2.

Model of the cumulative effects of racial stress and trauma

It is difficult to determine the mental health impact of racism in Canada because, as noted previously, most healthcare institutions do not collect data on race and ethnicity [5, 14]. As such, it is difficult to make connections between racialization and mental health service use. Furthermore, unlike the USA, there is limited research on these issues in Canada, and there are no empirical studies at all on the impact of racism on francophones of colour. Collecting race-based data is essential for understanding and addressing mental health inequities and for creating more equitable and culturally competent care e.g., [14]. The collection of this data by government bodies and researchers is a more recent phenomenon, driven primarily by scholars and advocates of colour, as well as community organizations (e.g., Across Boundaries, Rainbow Health). This is further perpetuated by Canada’s emphasis on multiculturalism; this often insinuates that racism and health lack connection and disregards any discussion which tries to investigate their relationship [3].

Reviews of papers on the mental health impact of racism experienced by Canadian people of colour are presented in the following sections. These consist mainly of survey/questionnaire studies and focus group data. Sections include the experience of Indigenous people in Canada, Black Canadians, Asian Canadians, those with intersectional identities, and newcomers to Canada. We describe the role of epigenetics in the inheritance of trauma, discuss commonalities between the experiences of racialized groups, and conclude with recommendations for future research.

The Experience of Indigenous People in Canada

There is little to no data on PTSD across Indigenous populations in Canada (1.6 million individuals, 4.9% of all Canadians); nonetheless, it is clear that they are predisposed to several psychological conditions arising from ongoing experiences of racism and other forms of discrimination [29, 31]. In one study of First Nations adults across Canada, 99% of participants reported experiencing at least one instance of discrimination in the last year, and greater amounts of discrimination were correlated with greater symptoms of depression, especially in women [32]. Discrimination has been demonstrated to cause depression in First Nations adults living on rural reserves in Saskatchewan, with a greater prevalence in women than men [33]. Similar findings have been reported for Indigenous women in urban settings [34]. Racial discrimination has also been linked to prescription drug problems and gambling problems in Indigenous Canadians, which can be conceptualized as dysfunctional approaches for coping with stress and trauma due to racism [35, 36]. Indigenous college students in Canada have been found to experience more racism than African American or Latino American students in the USA, resulting in racial battle fatigue—a syndrome marked by anxiety, worrying, hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, and difficulty thinking clearly [37]. Housing discrimination against Indigenous people has been linked to stress and PTSD [38].

Much of the research that has been done in the USA to develop theories and mechanisms around historical and racial trauma can also be applied to Indigenous people in Canada due to similar histories of colonization and oppression [39]. The term “historical trauma” is sometimes used to describe the racial trauma of Indigenous peoples, since a history of cultural trauma is such a prominent part of the racial trauma experienced by Indigenous Canadians [31]. Although this term may imply that the traumatization of Indigenous peoples is related wholly to events in the distant past, racial trauma in Indigenous people in Canada is caused by a combination of factors, including being a target of historical aggression and genocide, the legacy of residential schools, inequitable distribution of resources to Indigenous communities, combined with encountering racial discrimination in daily life. Historical abuses and everyday racism have been implicated as a cause of stress and illness in Indigenous Canadians [31, 40], with educational systems, health care systems, and social services all contributing to the problem e.g., [41, 42].

Many Indigenous people live in fear of needing to access healthcare services and risking having their children apprehended by hospital staff following the legacy of the Sixties Scoop and years of discriminatory birth alerts [43]. More recently, birth workers have reported that pregnant Indigenous women within the current pandemic have faced racism, been denied pain medicines, stereotyped as “addicts” and “thieves,” unfairly surveilled by social workers, and subjected to medical treatments without their consent [44, 45]. Furthermore, coverage describing the discrimination of other Indigenous patients in Canada (e.g., the death of Joyce Echaquan of the Atikamekw Nation who was abused in a Quebec hospital) [46] may instil additional fear and vicarious traumatization on those reliant on the public healthcare system.

The Experience of Black Canadians

Black Canadians refer to individuals in Canada who are of African or Black Caribbean descent [9]. According to the 2016 Census, there are approximately 1.2 million Black Canadians, accounting for 3.5% of the total population in Canada and 15.6% of those defined as visible minorities [47]. According to the census, about 44% of Black Canadians in 2016 were Canadian citizens by birth, and more than half (56.7%) of the Black immigrants who came to Canada before 1981 were born in Jamaica and Haiti [48]. Due to the global prevalence of anti-Black racism, Black individuals experience various difficulties including racial profiling, carding, heightened hostile encounters with police, and distinct socioeconomic disadvantages. In juxtaposition to other Canadians, Black Canadians are amongst the poorest and least educated [10, 49]. Such findings further explain the difficulty of this population to combat the systemic and systematic barriers posited against them. In addition, Black Canadians are often subject to violent encounters with law enforcement [50]. With regard to police brutality, Canada has yet to provide a national database for police use of force and subsequent deaths. In fact, Canada does not collect race-based statistics for police-reported crime statistics. This is another indirect tool which results in the justice system avoiding claims of racism by Canadians of colour, especially for Black and Indigenous peoples. As a consequence, Black Canadians who report such experiences do not have the ability to prove that it is occurring on a systemic level. The denial of these claims by a system which refuses to collect the evidence to demonstrate its veracity is a kind of gaslighting for Black Canadians and is contrary to their own lived experience. This also carries implications for the physical, social, and psychological well-being of this population.

Likewise, a study of 50 African Canadian women living in Nova Scotia provided significant evidence for racial trauma [5]. Participants reported that they experienced various types of racism daily and that racism was apparent throughout every factor of their day-to-day life. These incidents included being followed in public and others confusing them for another person of the same race. In addition, “being stared at by strangers,” “being treated in an “overly” friendly or superficial way,” and their “ideas or opinions being minimized, ignored, or devalued” were the most common experiences for daily racism. Although 28% of the sample reported mild-to-moderate or major depression scores, these findings lacked association with self-reported racism or racism-related stress. Rather, participants felt that the term distress was the best descriptor with regard to racism and racism-related stress. Implications of such racism-related distress ranged from not caring about job performance due to lack of recognition to rumination and the subsequent sleep dysregulation. Others reported a lowered self-esteem and sense of safety as well as feeling violated and exhausted. One participant even stated that she experienced anger as a result of racism and that this suppressed anger results in hypertension; another identified the effects of racism on her physical health as for her, racism was a contributing factor to her over-eating [5]. In sum, the following account by one participant encapsulates the ubiquity of racism as a Black Canadian woman:

I’ve lived it all my life. And I can’t escape it. From the time I get up in the morning, once you step outside the door, it’s on. And it could be out there in any shape, form, whatever. You [turn on] the TV, you could see some commercial. You go out and you could see, you could experience it first-hand. It could be a comment, could be a look, could be somebody talking to somebody else . . . It’s extremely stressful.” (age 51). (p. 108).

A two-part study was conducted to investigate the direct implications of racism in a sample of Black Canadians [1]. From the survey study, the majority of participants were female (67.5%), Canadian citizens (80.4%) or landed immigrants (7.6%), and ranged in age from 16 to 65 years. Researchers found that their experiences of explicit racism were associated with lower depressive affect and externalizing symptoms, being angry, which resulted in anger-out coping. Contrarily, subtle racism was associated with internalizing symptoms and higher depressive affect. The experimental study revealed that when the racist experiences of subtle discrimination were described, both Black and White participants were less likely to appraise these events as racist. A notable finding of this study was that the distress elicited while listening to these descriptions was associated with heightened cortisol levels in Black participants only, especially in cases involving physical violence [1]. This study identified depression, anger, and elevated somatic responses to stress as a result of racism, and thus, exemplified a probable case of racial trauma in Black Canadians.

In all, the existing literature on Black Canadians displays common themes in the events of racism. However, literature on this population still remains insufficient in identifying specific effects of racism on mental health to address and inform treatment to combat the associated racial trauma [49]. In addition, it is imperative to note that racial profiling, police violence, and socioeconomic status are the most commonly reported determinants of race-based stress by Black Canadians [51]. Researchers identified socioeconomic and political conditions as the most important factor for Black people’s overall well-being, yet stigmas against Black individuals contribute towards their lack of accessibility; this topic, especially in relation to racism in the medical care field, remains unaddressed in Canadian research [49].

Racial Profiling

The Ontario Human Rights Commission conducted a report on anti-Black racism amongst the Toronto Police Service and compared it to other Canadian cities [50]. Black people living in Ottawa were 2.3 times more likely to be stopped by police than their white counterparts; in Halifax, Black Canadians were six times more likely to be carded by police in comparison to White people; in Vancouver, Black people were overrepresented in street check statistics as they consist of 1% of Vancouver’s population yet 5% of those “randomly” stopped; and those living in Toronto are 20 times more likely to be fatally shot by the police than white people [50]. These statistics signify how anti-Black racism is embedded in the law enforcement practices across Canada and the extent to which the discriminatory treatment is exacerbated for Black Canadians specifically.

Police Violence

Given the aforementioned statistics, police violence contributes towards racism experienced by Black Canadians. For instance, researchers assessed the psychosocial stressors for Black Canadian women living in Montreal [51]. Participants identified financial adversity, racism, and absent fathers as the most prominent stressors. In terms of racism, participants stated that they often experienced various accounts of everyday racism; one participant noted that it was subtle in comparison to the USA, being primarily “hostile stares” and “terse customer service.” Numerous participants identified state institutions, being primarily the police, immigration service, and provincial government, as a regular source of racism. In addition, when providing accounts of these experiences, it was apparent that participants were especially upset. Despite being Anglophones, participants insisted that being Black was the reason for experiencing such hostile interactions. Nonetheless, financial adversity was still the most prevalent stressor amongst participants [51].

Socioeconomic Status

Black Canadians are at a significant socioeconomic disadvantage in comparison to all other ethnoracial groups [9]. In fact, the last census reported that the unemployment rate for Black women was two times higher than white women; for Black men, their unemployment rate was 1.5 times higher than white men. This translates into the heightened food insecurity experienced by Black Canadian youth who experience moderate or severe household food insecurity by threefold in comparison to White Canadian youth. Moreover, Black Canadians reported discrimination in the hiring process and workplace as in 2014, 13% of Black Canadians experienced this discrimination, whereas 6% of the remainder of the Canadian population reported this discriminatory treatment. Last, reports have identified racial discrimination to have a significant impact on Black Canadian’s accessibility to the housing market as those with darker skin were mostly implicated [9].

For instance, a study of 1544 adults from Toronto and Vancouver found that Black participants were fivefold more likely to report hypertension than Asian, South Asian, and White participants [52]. Additionally, Black Canadians were at the greatest risk for major and routine discriminatory experiences; they were also the poorest and least educated in this sample. These findings are consistent with existing literature, which signifies the unique complexity of the socioeconomic and psychological disadvantages faced by Black Canadians [52].

As a consequence, this hinders accessibility for Black Canadians in terms of diagnosis and mental health services. Cumulatively, these factors further exacerbate the implications of race-based stress and racial trauma experienced by this demographic [5, 10]. As noted by researchers, this inaccessibility results in Black youth experiencing adversities in education, family dynamics, and the criminal justice system [10]. In addition, physicians and other medical professionals are not trusted by many Black Canadians due to historic, racially motivated events [10, 49]. Ergo, it is imperative for there to be acknowledgement and initiatives established towards eradicating the institutional racism that precludes the mental health of Black Canadians.

The Experience of Asian Canadians

Asian Canadians are the most rapidly growing and the most ethnoculturally diverse group in Canada, originating from various countries including China, India, Pakistan, Bangla-Desh, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines [11, 47]. This group consists of descendants of immigrants, essential labour immigrants, and higher educated immigrants. Anti-Asian racism has a long history with early Chinese, Japanese, and East Indian immigrants being viewed with hostility, and their entry and life in Canada being limited by exclusionary policies of head taxes, restricting citizenship, lack of voting rights, and occupation. Anti-Asian discrimination continues to exist in Canadian society, as evidenced by recent anti-Asian verbal and physical attacks and negative portrayals as sources of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though Vancouver is considered to be “the most Asian city outside of Asia,” in 2020, police recorded 98 anti-Asian hate crimes and thus was named the “Anti-Asian Hate Crime Capital of North America” [53].

Sue et al. [19] have identified certain themes along which anti-Asian discrimination occurs, such as being seen as aliens within the country, ascription of intelligence, exoticization of women, ignoring inter-ethnic diversity, denying their reality, pathologizing cultural values and communication style, ascribing second class citizenship, and invisibility. Such patterns have been observed in Canada; for example, a recent survey of 516 Chinese Canadians revealed that this population experienced discriminatory behaviours which significantly impacted their sense of self and belonging. Sixty-one percent of respondents said that they had to change their routines in order to avoid microaggressions, and over 50% expressed concern that Asian children would be subjected to bullying. Notably, 44% of these respondents were born in Canada, and one in four Chinese Canadians reported that they feel like outsiders living in Canada [54]. Results of a study investigating the effects of discrimination on hypertension showed that education moderated the impact of discrimination for Asians in Canada [52]. However, a paper commenting on the experience of Filipino youth and their educational underachievement implicates the roles of colonialism, internalized racism, trauma, and having to drop out of school to work in the long-term care industry [55].

Despite the pervasive nature of anti-Asian discrimination, there is very little research on the mental health impact of racism on Asians in the Canadian context. In general, findings from the USA have been used to discuss these issues, and most existing Canadian research has focused on Asian immigrants. However, there has been some research since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, in response to reports that mental health issues in Canada have increased especially for visible minorities such as East Asian Canadians. Wu and colleagues [56] found a significant mental health gap between East Asian Canadians (Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Canadians) and White Canadians, such that East Asian Canadians had significantly worse mental health. The authors propose that acute discrimination can help account for over 20% of the mental health gap between East Asian and White Canadians, and after controlling for acute discrimination, this mental health gap was no longer significant.

Of the 22% of the Canadian population self-identified as a “visible minority,” South Asians make up the largest percent [47]. In spite of this, there are insufficient statistics on the mental health of South Asians in Canada [11]. Compared to White Canadians, South Asians are more likely to have college and university degrees; however, they encounter more barriers in obtaining employment and are often given lower employment income than White Canadians, suggesting that they are targets of systemic discrimination [57]. In a study on the impact of racism on South Asian university students, by Samuel [58], all participants strongly reported being the targets of racism at university, through feeling minimized, silenced, alienated, and excluded by peers, along with vicarious racism. They associated these experiences with an increase in self-doubts regarding their abilities and status, isolation, and lower sense of belonging to the university. Similarly, another focus group study identified certain microaggression themes—being “fresh off the boat,” not a part of Canadian society, assumptions of how they prefer to socialize, and ascribed stereotypes of intelligence and abilities (math and science) for which they felt exploited, and for men, being associated with terrorism. Finally, they felt that “being brown” is a liability and a barrier to success [57]. Additionally, South Asian women’s narratives indicated that they experience pressures to assimilate and internalize White beauty standards and behaviour, and despite being born in Canada, were othered [59]. Mahli and Boon [2] found that their South Asian participants were using the same narratives as White Canadians to rationalize and minimize their experiences of discrimination. This suggests the presence of internalized racism. In contrast, a study by Outten and Schmitt [60] showed that a strong identification with their South Asian ethnic identity served as a protective factor in mitigating the impact of discrimination and increased life satisfaction.

The relative success of Asian Canadians in comparison to others has often reinforced the myth of the model minority. However, the limited research that is available indicates that there are significant mental health impacts of racism and that this group is less likely to use mental health services [61], suggesting that these and potential racial trauma often remain unaddressed.

The Experience of Immigrants and Refugees to Canada

26Canada actively pursues immigration for its economic and social benefits; more than 20% of its population was born outside of Canada with migration accounting for approximately two-thirds of the population growth [62, 63]. Between 2011 and 2016, Canada saw its immigrant population increase by 19% (~ 1.2 million people) with larger provinces receiving the most immigrants. Over the last twenty years, the majority of Canada’s immigrants have arrived from South and East Asian countries, resulting in an increasingly racialized population [62, 63]. There is considerable diversity within the immigrant population, which influences their experiences in Canada based on their personal and social-cultural contexts. These include country of origin, age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, faith, place of settlement, education level, language proficiency, employment status, income and socioeconomic status, perceived discrimination, and language barriers [64, 65], which intersect to determine the immigrant experience e.g. [64, 62]. These social-cultural contexts can act either as risk or protective factors [64, 66]. Due to the diversity within the immigrant and refugee group, inaccuracies in counting populations, and because researchers have tended to “lump” them together as a monolithic group, it is difficult to obtain a definitive picture of the results of research on these groups [64, 66–68]. For example, when investigating the mental health of Latin American immigrants to Canada (another rapidly growing group), researchers have tended to focus primarily on Central American refugees without looking at other demographic variables such as education, income, employment (e.g., seasonal farm work), and language ability [67]. Overall, immigrants have different risks for developing mental health problems due to experiencing many different social-cultural contexts [64]. However, several studies have indicated that a significant number of immigrants and refugees experience many pre-migration stressors and traumas such as war, disruption, and human rights violations [64, 67, 69] and post-migration stressors such as ability to acculturate, low income, unemployment, lack of recognition of credentials, and hence working at a level below their qualifications [64, 66, 70, 71], and living in poorer neighbourhoods [72]. Notably, more immigrants and refugees have university degrees compared to the average Canadian, and yet earn less and work in jobs that are not commensurate to their education [66]. Such post-migration factors may be more critical than pre-migration factors [64, 73] and are believed to be associated with greater risk for developing mental health problems including PTSD. These post-migration factors are likely a reflection of structural and other forms of racism within which immigrants live in Canada. Taken together, applying the Williams et al. [26] model of trauma, all these factors can be seen as establishing vulnerabilities and a stress base for immigrants and refugees.

There is a greater negative impact of the social determinants of health in immigrant and refugee populations [66]. Amongst these various social determinants of health for immigrants, discrimination in the form of social inequality, social trauma (direct, witnessed, or vicarious), and insufficient and problematic health care is a major factor that influences the mental health of immigrants [63, 74]. For example, studies of first- and second-generation immigrants [75, 76] have revealed that experiences of discrimination have a negative impact on self-reported mental health and life satisfaction. Immigrants that are marginalized have poorer self-reported mental health, life satisfaction, and well-being, along with lesser economic and educational achievement. In contrast, immigrants who have a strong sense of belonging to both Canada and their own ethnic group report higher levels of well-being and success. Their results also showed that assimilation or having a strong sense of belonging to only Canada and not one’s ethnic group may mitigate the impacts of discrimination. However, they also found that for many second-generation immigrants, their cultural identity is an important part of being Canadian, which could potentially place them at risk for discrimination. In this regard, it is worth noting that people of colour do not always have a choice as to how they engage with their environment due to issues of structural racism [77], and hence, they can be at risk for poorer mental health.

Beiser and Hou [78] investigated mental health in a sample of refugees, economic immigrants, and family-class immigrants from 50 countries. They found that male refugees had poorer mental health compared to economic and family-class immigrants. Refugee men tended to perceive discrimination more than other immigrant men and were more impacted by it. Although female refugees reported experiencing more discrimination than males, discrimination accounted for mental health disparities only in males, and establishing social networks was a protective factor only for females. This study found that having a sense of belonging to Canada was associated with better mental health, underscoring the importance of addressing anti-refugee and anti-immigrant discrimination. In a previous study, Beiser and Hou [79] found that refugee youth showed higher levels of emotional problems and aggressive behaviour compared to immigrant youth. In addition to pre-migration trauma, refugee youth also reported more post-migration trauma including discrimination which accounted for these higher levels of emotional problems and aggressive behaviour. The authors concluded that anti-refugee discrimination has harmful mental health effects and it is critical to address not only pre-migration traumas but also post-migration discrimination experienced by refugees. Furthermore, Noh et al. [80] found that perceived racial discrimination was related to depressive symptoms and reduced positive affect in Korean immigrants in Toronto. Specifically, overt discrimination was related to decreased positive affect and subtle discrimination was related to depressive symptoms, underscoring the importance of subtle forms of discrimination. Similarly, De Maio and Kemp [81] found that immigrants who reported “unfair treatment” and discrimination experienced a decline in mental health after arriving in Canada. The phenomenon of a decline in immigrant health from a higher level to one that is similar to the Canadian-born population associated with the time spent living in Canada is referred to as the “healthy immigrant effect” [82] and is believed to be associated with discrimination, racism, and socioeconomic inequality [83]. This effect occurs disproportionately more in women and in non-European immigrants, including West Asian, South Asian, and Chinese people [84].

Veenstra et al. [85] found that Asian women and men were more likely to report experiencing fair/poor mental health in comparison to White women and men, and that immigrant status was a moderating factor. Furthermore, in a focus group study, refugee youth reported discrimination based on their race and visible minority status, English language proficiency, and newcomer status. The forms of discrimination ranged from being seen as less intelligent, more dangerous, and “not Canadian enough,” and being blamed for incidents by teachers and police, all of which impacted their sense of belonging and self-worth. These youth also reported that mental health problems are not acknowledged and are stigmatized in their communities which can account for underutilization of services [86]. Similar narratives and themes were found in another focus group study by Hilario and colleagues [87] where immigrant youth reported marginalization due to factors such as Islamophobia and anti-Asian racism, and feeling like second class citizens. According to these researchers, such practices reveal “…the biases in Canadian society that construct and justify the exclusionary practice of placing White Canadians into the category of true, first-class citizens and placing racial minority immigrants and refugees into the category of not-quite-Canadian second-class citizens” [87], p. 218.

Specific to PTSD, a longitudinal study of middle-aged and older adults revealed that “minority” immigrant Canadians had a higher chance of PTSD compared to non-immigrant Canadians, while White immigrants had a lower chance of PTSD [88]. It is very likely that this difference in the relationship between PTSD and ethnicity may be moderated by discrimination and racism. When it comes to mental health interventions, in comparison with Canadian-born citizens, immigrants and refugees tend to underuse mental health services because they are either under referred or do not seek out the services for a variety of reasons [89–91]. These include structural and cultural barriers such as lack of culturally competent services (ethnic mismatch, language barriers, perceptions of prejudice from health care providers, lack of trust of mental health services, and stigma; [91, 92]), and lack of adequate information on services and resources available or unfamiliarity with how to navigate the healthcare system [66]. In particular, existing health care systems have been criticized for failing to take into account the unique needs and experiences of various immigrant groups through being structured in standardized ways [66].

As per the model by Williams et al. [26], the experiences of immigrants and refugees can create a “stress base” which can predispose them to racial trauma, especially if these experiences are responded to with invalidation, lack of recognition, and ineffective interventions.

Intersectionality

Although thus far we have focused primarily on examining the mental health impact of racism by individuals’ ethnoracial groups, we acknowledge that this is but one marker of social identities, which are complex and multidimensional [93]. An individual’s experience of their racial identity is mediated by factors such as gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, religion, ability, family dynamics, and historical, social, and political contexts [94]. These markers of identity intersect to determine how the world perceives the individual, and informs their experiences including experiences of discrimination [93]. These points will be explored through an examination of the literature on the intersectionality between race/ethnicity and sexual orientation, and the intersectionality between race/ethnicity and religion.

Sexual and Gender Minorities of Colour

As noted by researchers [95], the intersectional microaggressions theory states the social experience of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people of colour (LGBTQ-POC) significantly differs from White LGBTQ individuals due to the unique sociodemographic factors (e.g., race) that intersect and cumulatively implicate their psychological and physical well-being. Intersectional microaggressions are defined as “subtle forms of discrimination, occurring in everyday life due to intersections of race, sexual identity, gender, social class, and other sociodemographic factors” [95], p. 112. This intersectionality, in turn, contributes to the exacerbated mental health needs for LGBTQ-POC as they are faced with unique psychological and social stressors [96, 97]. Such stressors include integrating two aspects of their identities (i.e., ethnic culture and sexual orientation) in a society in which both identities are subject to oppression [96]. In addition to experiencing acts of everyday racism and heterosexism, LGBTQ-POC experience racism from their LGBTQ communities, heterosexism from their ethnic communities, and other forms of oppression [97]. A study by Giwa and Greensmith [98] investigated racism and race relations within the Toronto LGBTQ community and found that both racism within the LGBTQ community and systemic racism impact LGBTQ individuals.

Given that research has established a link between sexual minority discrimination, stress as a result of racial prejudice, and mental and physical health [97], it is imperative to acknowledge the unique complexity for those who identify as POC and a sexual minority. Typically, for BIPOC individuals, their culture and community are protective factors to their physical and mental well-being, especially in terms of racial discrimination [99, 100]; however, due to the vast stigmatization of sexual minorities and transgender identities amongst racialized communities, this facet of resilience is not a certain option [97]. Additionally, a study of BIPOC members of the LGBTQ community via 11 semi-structured interviews with LGBTQ-POC individuals found that participants felt disconnected from their racial community as a result of their sexual identity [97]. Ironically, multiple participants felt ostracized from their local LGBT community as they experienced racism and exclusion from White members. This led five participants to only participate in LGBTQ-related events that involved POC members. Furthermore, the majority of participants reported stress and anxiety as a constant factor in their life; two individuals attributed these symptoms to police encounters involving racial profiling, and one individual attributed this to internalized racism and misogyny. Overall, four participants stated that the stress associated with these racialized and discriminatory experiences had negative health implications [97].

Likewise, this exclusion was found amongst LGBTQ-POC social service workers in Toronto [98]. Participants reiterated how pervasive racism is within the LGBTQ + community; while there are non-White members of the LGBTQ + community, the “coming out” process is not as feasible for racialized individuals when those cultures are only supportive of heteronormativity. As a result, the media relations and public perceptions of the LGBTQ + community as White have contributed to the erasure of POC voices within this community [98].

Muslim Canadians

Muslims represent approximately 3.2% of the Canadian population and are believed to be one of the rapidly increasing ethnoracial and religious minority groups in Canada [101]. Muslim Canadians represent a heterogeneous group of individuals based on factors such as race, ethnicity, gender, culture, economic situation, countries of origin, and national contexts that intersect to inform their experiences [102]. Canadian-born young Muslims are considered to be more integrated into mainstream society than their parents but are also more observant of their faith [103]. According to a 2016 survey, one in three Muslim Canadians reported experiencing discrimination in retail, public, and work spaces, and in educational institutions based on their ethnicity and religion [103]. Anti-Muslim attitudes and discrimination, including Islamophobia (fear and dislike of visible Muslims), have been increasing especially since 9/11 [104]. Canadian federal statistics suggest that there is an increase in hate crimes and aggression believed to be motivated by Islamophobia [105]; examples include the shootings and murder of six Muslims in a Quebec mosque [106] and the placement of a gift-wrapped pig’s head outside the same mosque [107]. Even as this paper is written, a Muslim family in London, Ontario, was targeted and murdered because of their faith [108]. A Canadian survey showed that between 33 and 57% of Canadians have negative views of Muslim people or of Islam. Additionally, 60% of Canadian Muslims were very (27%) or somewhat (35%) worried about anti-Muslim discrimination [103].

Within this population, Muslims who are also people of colour can experience discrimination associated with race. Furthermore, Muslim women can experience discrimination that is not only religious, but also racial and gendered [104, 109]. Similar to data from the USA and the UK, a Canadian survey revealed that 42% of Muslim women reported that they had experienced discrimination [103]. Muslim women are believed to be more vulnerable to discrimination due to wearing more visible markers of Islamic faith such as the hijab [102, 110]. Additionally, related institutional policies formulated by the government of Quebec, such as Bills 21 and 62, have served to further limit opportunities and marginalize Muslim women, increasing their vulnerability to racism.

The mental health stressors experienced by Muslim women in Canada are related to the various aspects of their identity—women, visible religious and racial markers, minority status, immigration histories, and culture-based stigma around mental illness [102]. Experiences of anti-Muslim discrimination and hate at individual and societal levels have several negative mental health effects on Muslim people in Canada. A community-based project investigating discrimination experienced by Muslim Women in Canada and the subsequent mental health impacts found that participants reported incidents of subtle discrimination in the form of assumptions and stereotypes, as well as overt discrimination in the form of verbal abuse and threatening messages, feelings of low self-esteem, isolation, and loneliness in response to discrimination and lack of support. Additionally, hijab-wearing Canadian-born Muslim women reported struggles in finding and maintaining their identities in the face of discrimination and stereotypes of Muslim women. Black Muslim women reported their own unique experiences of discrimination relating to their black identity and feeling invisible within the Muslim community [104].

Elkassam et al. [111] identified a gap in the literature on the impact of Islamophobia on Muslim children, which they believe may have even greater negative impacts. To address this, they conducted a focus group study with school-aged children and found that discrimination and Islamophobia were common occurrences in Muslim children’s lives; being bullied themselves and witnessing racism towards their family and community contributed to feelings of fear, marginalization, disempowerment, and internalizing negative beliefs and stereotypes about Muslims. At the same time, faith also provided them with a source of pride and comfort. Such experiences of discrimination can negatively affect mental and physical health, as well as children’s development [112].

As can be seen, Muslims in Canada experience race-based stressors in the form of historical trauma, hostile discourse, and institutional discrimination through policies and practices, along with interpersonal discrimination and microaggressions including perceptions, representation, and overt acts of racism such as hate crimes. The intersecting impact of these stressors can create a “stress base” and vulnerability for racial trauma. Despite the prevalence of incidents targeted at Muslims in Canada, they remain an understudied group in terms of their mental health and effective mental health services [110, 113]. The underutilization of mental health services is associated with several reasons. First, in Islam, problems of health are viewed as acts of destiny, determined by the will of God, and hence are addressed by prayer. Second, there is considerable stigma around mental health issues which are considered to be private, shameful, and to be addressed within the family and community. Finally, there is mistrust of existing mental health care systems that are designed to be a one size fits all and are difficult to access due to language, cultural mismatch, cultural barriers, and which generally do not incorporate spirituality in their practices [110, 114]. Thus, Muslims who require more specialized mental health care for PTSD and other symptoms are less likely to receive it.

The incidence of anti-Muslim racism has been documented by government and public policy institutes, the media, and Muslim organizations. However, as previously stated, there is a dearth of information on the mental health impact of constant racial harassment, microaggressions, discrimination, and hate crimes. In particular, despite the frequency of and potentially traumatizing nature of hate crimes against Muslims, the relationship between such events and PTSD or racial trauma remains understudied. Given this, more research about the mental health impacts of racism against Muslims is required in a Canadian context.

Racial Trauma and Epigenetics

It is clear that all non-White groups in Canada are subject to stress or even trauma due to racialization, and this may be compounded for those with additional stigmatized identities. Racial trauma has the potential to cause lasting biological effects above and beyond changes in emotion and behaviour. Trauma causes damaging effects down to the cellular level on neuronal circuitry and gene expression, and these detrimental changes can be passed down from parents to children [115, 116]. The mechanism by which traumatic environmental insults cause heritable modification in gene expression without actual changes in DNA sequence is called epigenetics. Epigenetic changes allow biological encoding of experience. There are at least five known mechanisms by which epigenetic modifications can occur; however, the most studied of these are DNA methylation, chromatin or histone remodelling, and microRNA expression [117, 118].

Genes active in the brain that stabilize the memory of trauma have been found to be associated with an increased risk of psychosis in individuals with childhood trauma. These are genes known to be regulated by epigenetic processes [117]. Traumatic experiences which occur early in life have also been shown to correlate specifically with methylation of genes in the glucocorticoid pathway, which has a role in a wide range of physiological systems including immune and metabolic functioning and regulating stress responses. DNA methylation is specifically altered in the glucocorticoid receptor gene, NR3C1, which has been associated with psychosis, war trauma victims, childhood stress, low socioeconomic status, depression, and chronic pain [115, 119, 120]. These changes have furthermore been shown to have generational effects, in that children of holocaust survivors with PTSD were shown to have lower cortisol and enhanced glucocorticoid sensitivity in comparison with age-matched Jewish control subjects [121]. In addition, severity of adversity has been positively correlated with alterations in methylation of the promoter of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in a group of racially diverse children under five, supporting this biological mechanism in mediating some of these behavioural effects and providing a mechanism as to how racially inflicted stress can impact the children of racialized individuals [122].

Notably, epigenetics provides clinicians with a mechanism by which to explain similar negative health effects, which have been now shown to be environmentally driven, across diverse groups who have experienced similar racial trauma. A recently published model elucidated by Conching and Thayer [115] provides further specificity in describing how similar health disparities can be consistently observed amongst populations such as war trauma victims, Jewish Holocaust survivors [121], and Native Indigenous populations that share histories of trauma and social subjugation [115].

In this conceptual framework, stress-induced epigenetic effects, established in past generations, affect the health of descendant generations by intergenerational effects. This provides a mechanism to perceive how a historical trauma, rooted in initial traumatic encounters between Indigenous and Western cultures, has ongoing effects and can be exacerbated by the original trauma. The resulting heritable alteration in gene expression (i.e., stress, memory, hormones) occurs through epigenetic mechanisms [115, 116]. There are unfortunately ongoing practices by the Canadian health service (coerced sterilization) which can worsen traumatization by exploiting existing epigenetic vulnerabilities.

Detrimental epigenetic changes caused by trauma can be mitigated with therapy. Targeted behavioural therapy, alone or in combination with classical pharmaceuticals, can induce changes in the brain which are similar or complementary to changes caused by neuromodulatory chemical substances [123].

Behavioural approaches such as CBT have been shown to induce epigenetic changes which correlate with improvement in clinical symptoms and have been demonstrated in clinical studies to result in improvement in patients with mental disorders. There is significant evidence in the literature that behavioural changes caused by behaviour-based therapeutic interventions have been shown to correlate with favourable changes in gene methylation patterns [123–125]. For example, patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) were demonstrated to have significantly lower MAOA promoter methylation in comparison to healthy controls. In a pilot trial of 14 controls and 12 OCD patients, reduction in OCD symptoms was significantly correlated with increases in MAOA methylation levels [125]. Behavioural therapy furthermore has been shown to be capable of altering dopaminergic signalling pathways, which are the targets of most antipsychotics [123, 124, 126].

Discussion

Overall, it is evident that all Canadians of colour are at risk for diminished mental health and traumatizing symptoms as a result of daily and lifetime racial discrimination, better denoted as racial trauma. The existing Canadian literature displays common themes and contrasts in the psychological ramifications of each group’s racial trauma. In addition to daily and lifetime racism, many groups reported other events of racism that significantly contributed to their traumatization; common events included health care discrimination for Indigenous [36] and immigrant/refugee populations [66], systemic discrimination for Indigenous [36] and Asian Canadians [57], and racial profiling for Black [50] and LGBT-POC Canadians [97]. As a consequence, various symptoms associated with trauma were exhibited by each group (Table 1). Specifically, depression was one of the most common symptoms as a result of racial discrimination and trauma, and this was well-documented for Indigenous [32–34], Black [5], and immigrant and refugee populations in Canada [80]. A notable finding was that depressive symptoms were exacerbated in women for the Indigenous population both on- and off-reserve [32]. Likewise, diminished psychological well-being was a prevalent factor for many populations, yet was found to be heightened amongst immigrant and refugee women [75, 76, 81]. To conclude, chronic stress was another consequential factor for Indigenous [37], Black [5], LGBTQ-POC Canadians [97], and immigrants/refugees [64, 72], whereas diminished self-esteem was commonly reported amongst Black [52], Asian [58], and Muslim Canadians [102, 111] as well as for immigrants and refugees [86, 87]. In terms of externalizing symptoms, studies found Black Canadians reported over-eating [52], while Indigenous Canadians reported excessive gambling and substance abuse [36].

Table 1.

Research-to-date summary of mental health outcomes due to racism

| Group | Reported events of racism | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Indigenous people in Canada |

• Daily racial discrimination/ “everyday” racism • Lifetime racial discrimination • Systemic and health care discrimination • Housing discrimination • Exclusion • Forced treatment |

• Depression* (on- and off-reserve) [32–34] • Substance abuse [36] • Gambling problems [36] • Stress, traumatization, PTSD, anxiety, rumination, intrusive thoughts, hypervigilance, cognitive distortions, isolation, exhaustion [31, 35, 37, 38, 40, 46] |

| Black Canadians |

• Daily racial discrimination • Police brutality • Racial profiling |

• Depression, stress, rumination, sleep dysregulation, diminished self-esteem, exhaustion, over-eating [5] • Hypertension [52] • Anger, heightened cortisol [1] • Traumatization [50] |

| Asian Canadians |

• Daily racial discrimination • Lifetime racial discrimination • Systemic discrimination • Alienation • Vicarious racism • Exclusion |

• Diminished psychological well-being [56] • Diminished self-esteem [57] • Lower sense of belonging [58] |

| Muslim Canadians |

• Subtle discrimination • Stereotypes • Overt discrimination • Verbal abuse • Threats • Lifetime/daily discrimination • Islamophobia; bullying |

• Diminished self-esteem, isolation, loneliness, traumatization [102, 104, 111] |

| LGBT-POC Canadians |

• Alienation • Exclusion • Racial profiling |

• Stress, anxiety [97] |

| Immigrants/refugees to Canada |

• Lifetime/daily discrimination • Overt discrimination • Subtle discrimination • Health care discrimination |

• Depression, reduced positive affect, stress [80] • Diminished psychological well-being*, lowered life satisfaction [64, 72, 75, 76, 81] |

Asterisk means the symptom was reported higher in women. Table is original

Furthermore, the multiple groups directly reported PTSD or traumatization as a result of racism, being Indigenous Canadians [35], Black Canadians [50], Muslim Canadians [102, 111], and immigrants/refugees [66]. While the literature on direct reports of traumatization for Asian and LGBTQ-POC Canadians was insufficient, both groups stated exclusion and alienation as a result of racism which resulted in their subsequent anxiety [58, 97]. Although the preceding literature gives inferences into the environmental ramifications of racial trauma, the overall amount of supporting literature remains inadequate.

While this research gives some insight into the experiences of Canadians of colour, there is a crucial need for more research that directly addresses the psychological symptoms associated with experiencing discrimination and racial trauma. Overall, Canadian research pertaining to racial trauma is insufficient and speaks to the urgent need for social justice and access to adequate, inclusive, and culturally competent healthcare systems. It also highlights the problems of current healthcare systems which have ignored the unique needs and lived experiences of Canadians of colour and have failed to provide adequate care.

There are numerous barriers to healthcare for Canadians of colour. People from racialized communities face greater cultural stigmas for simply having mental health difficulties let alone diagnosable mental disorders [127]. For many, it is taboo to discuss mental health difficulties with others outside of their community, and the lack of health professionals of colour to serve these communities is a major barrier to seeking mental health support. Additionally, when people of colour venture outside of their communities, it is not uncommon to find that healthcare professionals lack training in culturally informed approaches. Thus, Canadians of colour who are suffering from racial trauma may be in desperate need of mental health care to resolve symptoms and restore their quality of life, but are unable to access such care.

Future Directions

In spite of the serious gaps in the research on the traumatizing impact of racism in Canadians of colour and problems with existing healthcare, we believe that substantial change is possible through the following means. First and foremost, it is imperative that Canada adopts a more forward-thinking approach to combating the effects of racism as opposed to the withstanding lack of acknowledgement towards race and racism. Arguably, these wilful ignorance and indifference perpetuate the problem. To further enhance understanding of these topics, all health care providers and public agencies should be required to collect racial and ethnic data. Subsequently, these data must be analysed for racial discrepancies to inform interventions and to address structural racism in these systems. There are ample validated tools available that measure the level and impact of racism in society e.g., [26], and these urgently need to be employed to map the true extent of the issue and mitigate damages.

Similar to the National Survey of American Life (NSAL) [128] and the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLASS) [129] in the USA, national epidemiological surveys must be conducted in order to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mental health of Canadians of colour. This initiative would help to identify factors of stress, risk, and resilience for visible minorities in Canada and Indigenous Peoples and investigate the indirect and direct implications on their mental health. In turn, applying this methodology to a Canadian sample would allow for a better understanding of racial and ethnic differences in mental health in Canada, and thus, this would ultimately facilitate the incorporation of cultural competence into Canadian mental health practice.

Additionally, Canada must invest in diversifying the health care workforce to increase representation of racialized clinicians and train providers in anti-racist mental health care [130]. Federal funds should be allocated towards clinical research on the treatment of racial trauma. Cumulatively, these initiatives would improve the health of Canadians of colour who are suffering and reduce suffering in future generations.

Conclusion

Irrefutably, the Canadian experience is contingent on the hue of one’s skin, regardless of the national colourblind approach. The ultimate impact of experiences of racism is associated with deleterious outcomes such as chronic stress and trauma [9]. The magnitude and outcomes of such differential treatment are obfuscated by the lack of data to more precisely quantify these impacts; however, it does not make the status quo less true. The lack of these data, whether or not intentional, has worked to the advantage of Euro-Canadians and disadvantage of the full quarter of Canadians who are Indigenous or visible minorities. As described herein, there are numerous potential solutions for better understanding these problems, and with well-established models that have been successfully implemented in the USA and elsewhere, Canada has no excuse for remaining ignorant and indifferent. As a nation that values multiculturalism, it can and must do better.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to recognize Naomi Faber for assistance with proofreading.

Funding

This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant number 950–232127 (PI M. Williams).

Declarations

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors were performed in accordance with all applicable ethical standards including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical collection on Racism, Equity and Disparities in Trauma

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.• Matheson K. Pierre A. Foster M. D. Kent M. & Anisman H.. Untangling racism: stress reactions in response to variations of racism against Black Canadians. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, (2021) 8(1). 10.1057/s41599-021-00711-2. This article expressed how Canada’s multiculturalism policy actually hinders Canadians of colour as they experience systemic and systematic racism. Researchers examined the ramifications of explicit and implicit racism amongst Black Canadians. In all, this study provides further insight into racial trauma as this sample reported heightened cortisol levels, depression, and anger as a result of racist events.

- 2.Malhi RL, Boon SD. Discourses of “Democratic Racism” in the talk of South Asian Canadian women. Can Ethn Stud. 2007;39(3):125–149. doi: 10.1353/ces.0.0026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodney P, Copeland E. The health status of Black Canadians: do aggregated racial and ethnic variables hide health disparities? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(3):817–823. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart A. Penn and Teller magic: self, racial devaluation, and the Canadian academy. In: Nelson CA, Nelson CA, editors. Racism, eh?: A critical inter-disciplinary anthology of race and racism in Canada. Captus Press Inc; 2004. pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beagan BL, Etowa J, Bernard WT. “With God in our lives he gives us the strength to carry on”: African Nova Scotian women, spirituality, and racism-related stress. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2012;15(2):103–120. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2011.560145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satzewich V, Liodakis N. “Race” and ethnicity in Canada: a critical introduction. Oxford University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson CA, Nelson CA. Introduction. In: Nelson CA, Nelson CA, editors. Racism, eh?: a critical inter-disciplinary anthology of race and racism in Canada. Captus Press Inc; 2004. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faber S. C. Williams M. T. & Terwilliger P. R. Implicit racial bias across ethnic groups and cross-nationally: mental health implications. In M. Williams & N. Buchanan (Chairs), Racial issues in the assessment of mental health and delivery of cognitive behavioral therapies[Symposium].World Congress of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (WCBCT), Berlin, Germany. (2019, July)

- 9.Abdillahi I. & Shaw A. Social determinants and inequities in health for Black Canadians: a snapshot. (2020). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health/social-determinants-inequities-black-canadians-snapshot.html

- 10.Fante-Coleman T, Jackson-Best F. Barriers and facilitators to accessing mental healthcare in Canada for Black youth: a scoping review. Adolesc Res Rev. 2020;5:115–136. doi: 10.1007/s40894-020-00133-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Islam F, Khanlou N, Tamim H. South Asian populations in Canada: migration and mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(154):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenzie K. (2020, November 12). Race and ethnicity data collection during COVID-19 in Canada: if you are not counted you cannot count on the pandemic response. Royal Society of Canada. https://rsc-src.ca/en/race-and-ethnicity-data-collection-during-covid-19-in-canada-if-you-are-not-counted-you-cannot-count

- 13.Nestel S. (2012, January). Colour coded health care: the impact of race and racism on Canadians’ health. Wellesley Institute. https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Colour-Coded-Health-Care-Sheryl-Nestel.pdf

- 14.Varcoe C, Browne AJ, Wong S, Smye VL. Harms and benefits: collecting ethnicity data in a clinical context. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(9):1659–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger M, Sarnyai Z. ‘More than skin deep’: stress neurobiology and mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Stress Int J Biol Stress. 2015;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2014.989204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haeny A, Holmes S, Williams MT. The need for shared nomenclature on racism and related terminology. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2021;16(5):886–892. doi: 10.1177/17456916211000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waxman S. Racial awareness and bias begin early: developmental entrypoints, challenges and a call to action. Perspectives in Psychological Science. (2021) [in press] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Williams MT. Microaggressions: clarification, evidence and impact. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2020;15(1):3–26. doi: 10.1177/1745691619827499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AMB, Nadal KL, Esquilin M. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;62(4):271–286. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequalities. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):115–132. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viruell-Fuentes E. A. Miranda P. Y. & Abdulrahim S. More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health, Social Science & Medicine, (2012), 75(12). 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Carter RT. Racism and psychological and emotional injury: recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. Couns Psychol. 2007;35(1):13–105. doi: 10.1177/0011000006292033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanter JW, Williams MT, Kuczynski AM, Manbeck K, Debreaux M, Rosen D. A preliminary report on the relationship between microaggressions against Blacks and racism among White college students. Race Soc Probl. 2017;9:291–299. doi: 10.1007/s12552-017-9214-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torres L, Taknint JT. Ethnic microaggressions, traumatic stress symptoms, and Latino depression: a moderated mediational model. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(3):393–401. doi: 10.1037/cou0000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams M. T. Kanter J. W. & Ching T. H. W. Anxiety, stress, and trauma symptoms in African Americans: negative affectivity does not explain the relationship between microaggressions and psychopathology. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. (2017), 10.1007/s40615-017-0440-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Williams MT, Metzger IW, Leins C, DeLapp C. Assessing racial trauma within a DSM–5 framework: the UConn Racial/Ethnic Stress & Trauma Survey. Practice Innovations. 2018;3(4):242–260. doi: 10.1037/pri0000076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butts HF. The Black mast of humanity: racial/ethnic discrimination and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(3):336–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comas-Díaz L, Hall GN, Neville HA. Racial trauma: theory, research, and healing: introduction to the special issue. Am Psychol. 2019;74(1):1–5. doi: 10.1037/amp0000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellamy, S., & Hardy, C. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder in Aboriginal people in Canada: review of the risk factors, the current state of knowledge and directions for further research. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/emerging/RPT-Post-TraumaticStressDisorder-Bellamy-Hardy-EN.pdf

- 30.Hemmings C, Evans A. Identifying and treating race-based trauma in counseling. J Multicult Couns Dev. 2018;46(1):20–39. doi: 10.1002/jmcd.12090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gone JP, Hartmann WE, Pomerville A, Wendt DC, Klem SH, Burrage RL. The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for Indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: a systematic review. Am Psychol. 2019;74(1):20–35. doi: 10.1037/amp0000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bombay A, Matheson K, Anisman H. Decomposing identity: differential relationships between several aspects of ethnic identity and the negative effects of perceived discrimination among First Nations adults in Canada. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2010;16(4):507–516. doi: 10.1037/a0021373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janzen B, Karunanayake C, Rennie D, Katapally T, Dyck R, McMullin K, Fenton M, Jimmy L, MacDonald J, Ramsden VR, Dosman J, Abonyi S, Pahwa P. Racial discrimination and depression among on-reserve First Nations people in rural Saskatchewan. Can J Public Health. 2017;108(5–6):e482–e487. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.108.6151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benoit A, Cotnam J, Raboud J, Greene S, Beaver K, Zoccole A, O’Brien-Teengs D, Balfour L, Wu W, Loutfy M. Experiences of chronic stress and mental health concerns among urban Indigenous women. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2016;19(5):809–823. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0622-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Currie CL, Wild TC, Schopflocher DP, Laing L, Veugelers P, Parlee B. Racial discrimination, post traumatic stress, and gambling problems among urban Aboriginal adults in Canada. J Gambl Stud. 2013;29(3):393–415. doi: 10.1007/s10899-012-9323-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Currie C, Wild TC, Schopflocher D, Laing L. Racial discrimination, post-traumatic stress and prescription drug problems among Aboriginal Canadians. Can J Public Health. 2015;106(6):e382–e387. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.106.4979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Currie CL, Wild C, Schopflocher DP, Laing L, Veugelers P. Racial discrimination experienced by Canadian Aboriginal university students. Can J of Psychiatry. 2012;57(10):617–625. doi: 10.1177/070674371205701006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motz TA, Currie CL. Racially-motivated housing discrimination experienced by Indigenous postsecondary students in Canada: impacts on PTSD symptomology and perceptions of university stress. Public Health. 2019;176:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fast E, Collin-Vézina D. Historical trauma, race-based trauma and resilience of Indigenous peoples: a literature review. First Peoples Child Fam Rev. 2010;5(1):126–136. doi: 10.7202/1069069ar. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Currie C, Copeland J, Metz G, Chief Moon-Riley K, Davies C. Past-year racial discrimination and allostatic load among Indigenous adults in Canada: the role of cultural continuity. Psychosom Med. 2020;82(1):99–107. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bailey KA. Racism within the Canadian university: Indigenous students’ experiences. Ethn Racial Stud. 2015;39(7):1261–1279. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2015.1081961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips-Beck W, Eni R, Lavoie J, Avery Kinew K, Kyoon Achan G, Katz A. Confronting racism within the Canadian healthcare system: systemic exclusion of First Nations from quality and consistent care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):1–20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bergen R. (2020, January 31). Manitoba to end birth alerts system that sometimes leads to babies being taken. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/birth-alerts-ending-1.5447296

- 44.Burns-Pieper A. (2020, October 20). Indigenous women report racism and neglect in COVID-19 Canada childbirth. OpenDemocracy (London). https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/indigenous-women-racism-covid-19-canada-childbirth/

- 45.Sharma S. Kolahdooz F. Launier K. Nader F. June Yi K. Baker P. McHugh T. & Vallianatos H. Canadian Indigenous women’s perspectives of maternal health and health care services: a systematic review. Diversity and Equality in Health and Care, (2016), 13(5). 10.21767/2049-5471.100073

- 46.Lowrie M. & Malone K. G. (2020, October 4). Joyce Echaquan’s death highlights systemic racism in health care, experts say. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/7377287/joyce-echaquans-death-highlights-systemic-racism-in-health-care-experts-say/

- 47.Statistics Canada. (2017a). Focus on geography series, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98–404-X2016001. Ottawa, Ontario. Data products, 2016 Census.

- 48.Do D. & Maheux H. (2019). Diversity of the black population in Canada: an overview (Catalogue no. 89–657-X2019002). Ottawa, ON; Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-657-x/89-657-x2019002-eng.pdf?st=CGMgsBU5.