Abstract

Dendriform pulmonary ossification is a rare condition characterized by branching bony spicules. A 33-year-old man was clinically considered to have sarcoidosis. At 53 years old, another attending physician performed a detailed evaluation. Computed tomography (CT) showed a fine nodular pattern with foci of calcifications and pulmonary function testing showed peripheral airway obstruction. We performed a surgical biopsy. A histological examination revealed dendriform pulmonary ossification. After surgery, CT showed progression of some lesions; the pulmonary function had also decreased slightly. Since dendriform pulmonary ossification might be a progressive disease, we should perform long-term follow-up.

Keywords: dendriform pulmonary ossification, pulmonary ossification, prognosis, clinical course

Introduction

Dendriform pulmonary ossification (DPO) is a rare condition characterized by branching bony spicules (1). As the disease usually occurs without symptoms, most cases are diagnosed at an autopsy. The clinical course is thus uncertain, and cases with long-term observation have rarely been reported (2-5).

We herein report the clinical course of a patient with DPO over eight years.

Case Report

A 33-year-old man was admitted to another hospital because of an abnormal shadow with unknown details. He was clinically considered to have sarcoidosis. He received an annual follow-up examination for the next 20 years. His clinical features and imaging findings had remained stable, but the details are unknown.

At 53 years old, his attending physician was changed. The new physician suspected that he did not have sarcoidosis. He was thus referred to our hospital. Computed tomography (CT) showed a fine nodular pattern with foci of calcifications (Fig. 1A). He had no symptoms in any other parts of the body. In addition, his levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme, soluble interleukin-2 receptor, and Krebs von den Lungen-6 were normal at the first visit to our hospital. Although he had a history of childhood asthma, he was asymptomatic. He was an office worker and had no history of occupational or environmental exposure, smoking, or dust inhalation. Pulmonary function tests revealed a normal vital capacity (VC; 3.55 L, 94.2% of predicted), forced vital capacity (FVC; 3.52 L, 93.4% of predicted), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1; 2.67 L), and FEV1/FVC (75.9%). However, the ratio of flow at 50% to 25% of FVC (V50/V25) (3.17) was decreased.

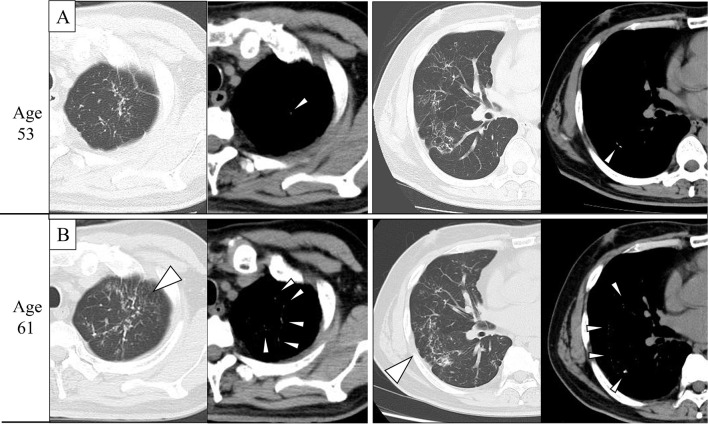

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) imaging findings at 53 and 61 years old. A: CT showed a fine nodular pattern with foci of calcifications in both lungs. B: CT showed the progression of some lesions over eight years (arrowheads). CT showed more fine calcifications in the mediastinal window (arrowheads).

We performed a lung biopsy via video-assisted thoracic surgery. A hard, white nodule was present in the visceral pleura (Fig. 2). A histological examination revealed dendriform mature bone formation with marrow in the alveolar spaces (Fig. 3). He was diagnosed with DPO and followed for the next eight years. In year 8, CT showed worsening of some lesions (Fig. 1B). Pulmonary function tests revealed a normal diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLco; 21.16 mL/min/mmHg). However, the VC (3.31 L, 91.2% of predicted), FVC (3.34 L, 92.0% of predicted), FEV1 (2.38 L), FEV1/FVC (71.0%), and V50/V25 (4.04) were decreased. Although he was asymptomatic, some lesions on CT had progressed, and the respiratory function had declined over the previous eight years (Table).

Figure 2.

Intraoperative findings during video-assisted thoracic surgery. A hard, white nodule (arrowhead) was present in the visceral pleura.

Figure 3.

Pathological findings of specimens obtained through video-assisted thoracic surgery. A histological examination revealed dendriform mature bone formation with marrow in the alveolar spaces. Hematoxylin and Eosin staining, original magnification ×5 (left) and ×10 (right).

Table.

Pulmonary Function Data at 53, 56, and 61 Years Old.

| Age | VC(L) | %VC | FVC(L) | %FVC | FEV1(L) | FEV1/FVC | V25 | V50/V25 | Dlco | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 53 | 3.55 | 94.2 | 3.52 | 93.4 | 2.67 | 75.9 | 0.72 | 3.17 | 22.28 | |||||||||

| 56 | 3.42 | 92.2 | 3.54 | 95.4 | 2.58 | 72.9 | 0.51 | 3.47 | 21.94 | |||||||||

| 61 | 3.31 | 91.2 | 3.34 | 92 | 2.38 | 71 | 0.51 | 4.04 | 21.16 |

Pulmonary function tests revealed normal diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLco). In contrast, the vital capacity (VC), forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), FEV1/FVC, and ratio of the flow at 50% to 25% of the FVC (V50/V25) were decreased.

Discussion

DPO was first reported by Luschka in 1856 (1). It is a rare disease with an estimated incidence of 0.16-0.6% (6,7). Pulmonary ossification can be divided into two types: nodular and dendriform. Nodular ossification has been linked to passive congestion due to chronic heart failure, mitral stenosis, and hypertrophic subaortic stenosis. Dendriform ossification is called DPO and can be idiopathic or associated with primary lung disease (6). Regarding the imaging findings, chest X-ray shows a reticulonodular pattern in both the mid-to-lower lung fields, and CT shows a fine nodular pattern with foci of calcifications in both lungs. However, DPO is rarely recognized radiographically during life. In many patients, the radiological findings, clinical signs and symptoms, or laboratory investigations are often insufficient for a diagnosis (8). Most previously reported cases were therefore diagnosed at an autopsy. In addition, some patients are misdiagnosed as having interstitial lung disease, such as interstitial pneumonia or fibrosis, bronchiectasis, lymphangitic tumor spread, or septal thickening. Indeed, our patient was considered to have had sarcoidosis and was followed for 20 years despite having no symptoms in any other parts of the body. In addition, the levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme, soluble interleukin-2 receptor, and Krebs von den Lungen-6 were normal. Sarcoidosis, interstitial pneumonia, and fibrosis were thus denied as diagnoses, and we suspected that he had had DPO since 33 years old. Since there was no primary lung disease, this patient was considered to have idiopathic DPO. Therefore, despite its rarity, DPO should be considered in the differential diagnosis of diffuse lung disease.

Very few reports of long-term observation of DPO have been reported; thus, information on the prognosis is limited. Some case reports have described asymptomatic patients with normal pulmonary function test results for 9 and 12 years (2,3). However, two other patients had dyspnea on exertion. In addition, the VC and DLco decreased, and some lesions of the lung worsened on CT over 10 years of observation (4,5). DPO is thus thought to be stable or progress slowly over many years (9). Although the pathogenesis of DPO is uncertain, a previous report showed that DPO is common in patients with fibrosing interstitial lung disease (10). Some patients with dyspnea on exertion show reductions in their VC, which might reflect the progression of DPO. In our patient, the VC, FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, and V50/V25 decreased over eight years. However, at 53 years old, pulmonary function tests revealed peripheral airway obstruction. Although our patient had no history of smoking or dust inhalation, he had a history of childhood asthma. The obstructive airway lesions might therefore have been influenced by childhood asthma. However, he had been asymptomatic, and a previous report showed that DPO is accompanied by restrictive and obstructive airway lesions (5). Thus, an extensive number of micro-calcified lesions might be associated with small airway disease, which can cause airway obstruction.

The pathogenesis of idiopathic DPO remains uncertain and may be a mixture of several pathological conditions. Therefore, the clinical guidelines, histopathological diagnostic criteria, prognostic factors, and therapeutic regimens have yet to be established. Long-term observation that provides information on the clinical course, CT findings, and pulmonary function test results is needed.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Lushuka HV. Two interesting benign lung tumors of contradictory histopathology. J Thorac Surg 9: 119-131, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ono K, Takeda T, Fujinami M, et al. Case of idiopathic dendriform pulmonary ossification diagnosed by video-assisted thoracic surgery and followed over a long period of 12 years. Jpn J Chest Surg 2: 264-268, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enomoto T, Takimoto T, Kagawa T, et al. Histologically proven dendriform pulmonary ossification: a five-case series. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahari JE, Delaney M. Dendriform pulmonary ossification: a clinical diagnosis with 14 years follow-up. Chest 132: 701a, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuo H, Handa T, Tsuchiya M, et al. Progressive restrictive ventilatory impairment in idiopathic diffuse pulmonary ossification. Intern Med 57: 1631-1636, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lara JF, Catroppo JF, Kim DU, da Costa D. Dendriform pulmonary ossification, a form of diffuse pulmonaryossification: report of a 26-year autopsy experience. Arch Pathol Lab Med 129: 348-353, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tseung J, Duflou J. Diffuse pulmonary ossification: an uncommon incidental autopsy finding. Pathology 38: 45-48, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Donnell R, Nicholson S, Meaney J, McLaughlin A, O'Connell F, Breen D. A case of persistent pulmonary consolidation. Respiration 75: 355-358, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felson B, Schwarz J, Lukin RR, Hawkins HH. Idiopathic pulmonary ossification. Radiology 153: 303-310, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egashira R, Jacob J, Kokosi MA, et al. Diffuse pulmonary ossification in fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: prevalence and associations. Radiology 284: 255-263, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]