Abstract

Objective

Interleukin (IL)-35 is a comparatively novel immunosuppressive cytokine produced by T-regulatory cells, the purpose of which in periodontal well being and disease still eludes the researchers. This study intends to measure and compare the levels of IL-35 in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) taken from periodontitis patients before and at first, second and third week post non-surgical periodontal therapy.

Methodology

ology: Twenty patients having generalized chronic periodontitis (mean age of 36.25 ± 5.12 years) with moderate to severe disease were assessed clinically for the following parameters: plaque index, gingival index, probing pocket depth, and clinical attachment loss. GCF samples were collected from deepest pockets before performing a full mouth non-surgical periodontal therapy. GCF samples were again collected at 1st, 2nd, and 3rd week after non-surgical periodontal therapy and, IL-35 levels in the GCF samples were measured using an ELISA kit.

Results

All the clinical parameters improved significantly over time from baseline to 3rd week. The results for plaque index, gingival index, and probing pocket depth were highly significant (p < 0.001) and significant (p < 0.05) for clinical attachment loss. The IL-35 concentration in GCF increased post periodontal therapy from baseline till third week and results were statistically highly significant (p < 0.001). A significant negative correlation (p < 0.001) was found between clinical parameters and IL-35 levels.

Conclusions

With the healing of the previously diseased periodontal tissues, the levels of IL-35 in GCF increases significantly. Therefore, IL-35 can be considered as potential inflammatory marker of periodontal health and disease.

Keywords: Periodontitis, Interleukin-35, Gingival crevicular fluid, Non-surgical periodontal therapy

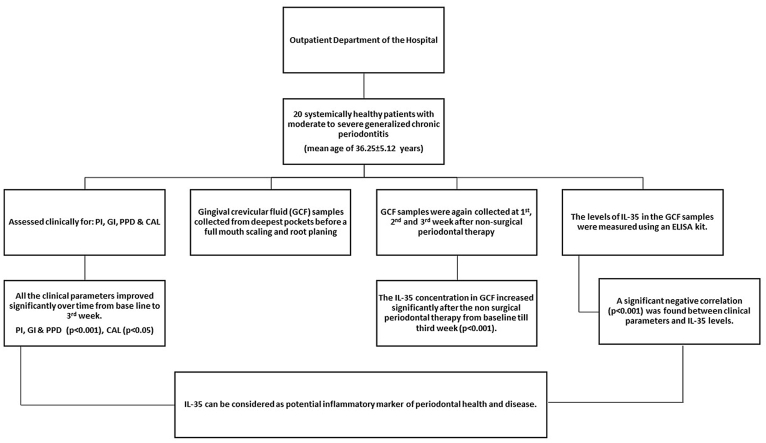

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Periodontitis, an immune-inflammatory disease affecting the supporting tissues of the tooth is among the most common diseases globally.1 Triggered primarily by the pathogenic bacteria, it is an interplay between microbial antigen and an unbalanced host immune response.2 Although genetics, environmental and systemic factors play a role, cytokines are critical in this delicate balance of destruction and restructuring of periodontal tissues.3

Cytokines, produced by a wide variety of cells are signaling molecules employed for cellular communication in immune responses. These molecules not only regulate the growth, differentiation, and migration of lymphocytes but also of other white blood cells and non-immune cells.4 Cytokines are cellular chemical switches that enhance or stop the action of other cytokines which include interleukins, interferons, and growth factors.5 They are produced by immune-inflammatory cells, for instance, macrophages and T-helper (Th) against antigens present on pathogens.6

Interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor family were among the initial pro-inflammatory cytokines recognized for lymphocyte promotion and tissue destruction in periodontitis.7 Later, anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, IL-16, and transforming growth factor β were recognized as acting as a balancing force in the destructive process.8 Both cytokines, pro and anti-inflammatory are critical for the destruction, repair, and remodeling of the supporting tissues of the tooth.9

Interleukin-35 is a comparatively novel immunosuppressive cytokine produced by regulatory T (T-reg) cells.10 It regulates the proliferation of T effector cells, impedes differentiation of Th 17 cells, and inhibition of IL-17 synthesis. IL-35 is also responsible for the sustenance of the peripheral immune system.11 The continence of T cell proliferation along with suppression of IL-17 production has a protective role in various diseases such as asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, and rheumatoid arthritis.12,13 IL-35 has been found to prevent bone loss in rheumatoid arthritis disease in an experimental study on the animal model.14

The contribution of Interleukin-35 in periodontal inflammation is still under investigation. It has been previously identified in saliva, GCF and within periodontal tissues in both healthy and diseased periodontium.15,16 Even though the function of many cytokines has been evaluated, the exact purpose of IL-35 in periodontitis eludes the researchers. IL-35 could well prove to be a potential marker of periodontal health or disease if given considerable attention in research. Keeping this as a foundation, the current study aimed to estimate and compare the levels of IL-35 in GCF obtained from patients having generalized chronic periodontitis before and at first, second and third-week post non-surgical periodontal therapy. We also investigated in case any correlation prevails between the clinical parameters of periodontitis and levels of IL-35.

2. Material & methods

Systemically healthy patients with generalized chronic periodontitis reporting to the outpatient department of dentistry were examined for recruitment into the study. Minimum sample size was calculated to be 17 patients (power 90% and α error at 5%) which was increased to 20 patients based on anticipated dropout rate of 10%. Thereafter, twelve females and eight males within the age range of 25–60 years were selected into the study. Inclusions criteria for patients were set based on the 1999 International world workshop for Periodontal disease classification.17 The selection criteria were: a) pocket probing depth ≥5 mm in 30% of sites, b) Clinical attachment Level (CAL) ≥3 mm in 30% of sites, c) radiographic evidence of moderate to severe bone loss on an orthopantomogram.

All patients were systemically healthy with at least twenty natural teeth in dentition. Pregnant and breast-feeding females, patients who received periodontal therapy in the last one year, patients who consumed anti-inflammatory medicines and antibiotics in the past six months, and patients taking any form of tobacco were excluded from the study. This investigation was performed in accordance with ethical principles and an informed consent was signed by all participants before clinical examination and inclusion into the study. The study was approved by Institutional Ethics committee via letter no: SGTU/Exam./Scy/MDS./5101A

2.1. Periodontal examination

The following parameters were recorded to clinically assess the patients: Plaque Index (PI),18 Gingival Index (GI),19 pocket probing depth (PPD), and clinical attachment loss (CAL). PI and GI were measured at four sites around the tooth (buccal, Lingual/palatal, mesial, and distal) whereas PPD and CAL were assessed at six sites on every tooth (mesial, mid, distal aspect of the buccal, and palatal/lingual sites). All the recordings were made at baseline and 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-week post non-surgical periodontal therapy. Full mouth scores were obtained by adding individual tooth scores and dividing by the number of existing teeth. For measuring pocket depth and CAL, a UNC-15 periodontal probe was utilized. The level of attachment was measured from the base of the pocket to the cementoenamel junction. All measurements were made by a single trained clinician calibrated for the purpose.

2.2. Collection of GCF samples

GCF samples were accumulated from at least 3 sites with the deepest pockets in every patient. Micropipettes were used for collection of GCF from the selected sites as this technique yields undiluted native GCF.20 To avoid contamination with saliva, maxillary sites were selected wherever possible. Also, the sampling area was isolated by cotton rolls to prevent salivary contamination. First samples were gathered from patients before performing non-surgical periodontal therapy to avoid dilution of samples. GCF was collected by gently elevating the gingival margin and inserting micropipettes until resistance was felt. The site was gently cleared of supragingival plaque before the insertion of micropipettes with manual supragingival scalers. Samples contaminated with saliva and blood were discarded. Pooled samples from all sites in every patient were processed together for the assessment of IL-35 levels. Till the time of assay, the collected samples were stored at −80° Celsius. GCF samples were again collected at 1st, 2nd, and 3rd weeks after non-surgical periodontal therapy.

2.3. Non-surgical periodontal therapy

Following the collection of GCF samples, a complete mouth non-surgical periodontal therapy was carried out in two sittings on consecutive days. SRP was performed using ultrasonic devices and manual scalers and for root planing; Gracey's specific curettes were used. Root surfaces were instrumented under local anesthesia if required. Oral hygiene instructions which included a modified bass method for brushing and interdental cleaning were given to all patients upon completion of the procedure. Patients were instructed against the use of any mouthwashes, antibiotics, or anti-inflammatory medication during the study. Motivation and hygiene instructions were reiterated at each visit during the course of study.

2.4. Measurement of IL-35 in GCF samples

The levels of IL-35 in the GCF samples were assessed using an ELISA kit following the guidelines by the manufacturer. The sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique was employed in the ELISA kit used. IL-35 is a dimer complex composed of 2 subunits therefore the kit used 2 antibodies which were designed for different subunits. The samples and ELISA kit were balanced for 30 min at ambient temperature. Samples were diluted by adding 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline. Consequently, the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 2000 rpm to remove any impurities. Forty μl of test samples and 10 μl of IL-35 antibody were combined. In standard wells, 50 μl of standard solution and 50 μl of Streptavidin-HRP were added. After sealing with sealing membranes, the samples were gently shaken and incubated at 37° centigrade for 60 min. The membrane was then removed carefully, and the liquid was drained and 50 μl each of chromogen solution A and chromogen solution B was infused into each well. It was gently mixed, incubated at 37° C for 10 min away from light. Fifty microlitres of stop solution to stop the reaction was introduced into each well. There was an immediate color change from blue to yellow. The optical density measurement under 450 nm wavelengths was carried out in an ELISA reader, within 15 min after the inclusion of a stop solution.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The data was tested with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test calculator to determine as to whether data distribution matches the characteristics of a normal distribution. All the parameters were normally distributed therefore, parametric statistical test were used to analyze data. Statistical analysis was performed by using commercially available software (SPSS Version 19.0; Chicago, USA). One-way ANOVA test was applied to assess a difference between groups, for both clinical and biological data, followed by Tukey's HSD test for pair-wise comparison. Relation between every clinical parameter and mean levels of IL-35 was established by Pearson's correlation coefficient. A p-value of <0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 20 patients with mean age of 36.25 ± 5.12 years were included into the study. Table 1 shows the clinical and biological data (mean ± standard deviation) of the study group at baseline, 1st, 2nd, and third week post non-surgical periodontal therapy. All the clinical parameters improved significantly over time from baseline to 3rd week. The results were highly significant (p < 0.001) for PI, GI and PPD. The IL-35 concentration in GCF increased sequentially and significantly after the non-surgical periodontal therapy from baseline (p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis of ANOVA for significant pairs was done through the Tukey HSD test (Table 2). The variation in clinical parameters was significant for all parameters one week post non-surgical periodontal therapy except CAL which came out to be significant after 3rd week.

Table 1.

Clinical and Biological parameters at baseline, 1st, 2nd and 3rd week post non-surgical periodontal therapy.

| Parameters | Baseline | 1st week | 2nd week | 3rd week | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | 2.385 ± 0.294 | 0.585 ± 0.281 | 0.88 ± 0.237 | 0.82 ± 0.263 | <0.0001* |

| GI | 2.64 ± 0.292 | 1.705 ± 0.252 | 0.965 ± 0.270 | 0.77 ± 0.222 | <0.0001* |

| PPD (mm) | 6.51 ± 0.285 | 5.81 ± 0.262 | 5.5 ± 0.369 | 5.43 ± 0.351 | <0.0001* |

| CAL (mm) | 5.07 ± 0.744 | 4.66 ± 0.560 | 4.6 ± 0.549 | 4.54 ± 0.566 | 0.032# |

| IL-35 (ng/μl) | 0.563 ± 0.312 | 0.812 ± 0.358 | 1.138 ± 0.367 | 1.323 ± 0.404 | <0.0001* |

One way ANOVA test of significance.

*Highly significant #Significant.

Table 2.

Tukey HSD post hoc test for pairwise comparison of Clinical and Biological parameters.

| Parameters | Baseline v/s 1st week |

Baseline v/s 2nd week |

Baseline v/s 3rd week |

1st week v/s 2nd week |

1st week v/s 3rd week |

2nd week v/s 3rd week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | p < 0.0001* | p < 0.0001* | p < 0.0001* | p = 0.0048# | p = 0.036# | p = 0.99 NS |

| GI | p < 0.0001* | p < 0.0001* | p < 0.0001* | p < 0.0001* | p < 0.0001* | p = 0.93 NS |

| PPD | p < 0.0001* | p < 0.0001* | p < 0.0001* | p = 0.013# | p = 0.001# | p = 0.91 NS |

| CAL | p = 0.155 NS |

p = 0.079 NS |

p = 0.037# | p = 0.989 NS |

p = 0.924 NS |

p = 0.99 NS |

| IL-35 | p = 0.138 NS |

p < 0.0001* | p < 0.0001* | p = 0.03# | p < 0.0001* | p = 0.375 NS |

*Highly significant #Significant NS Non-significant.

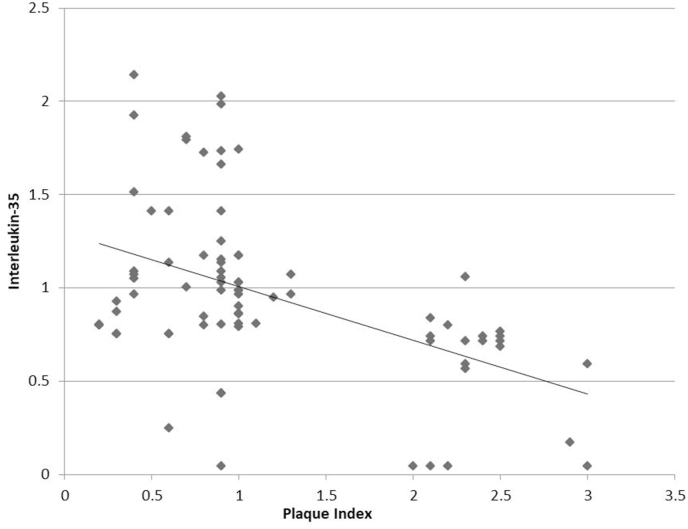

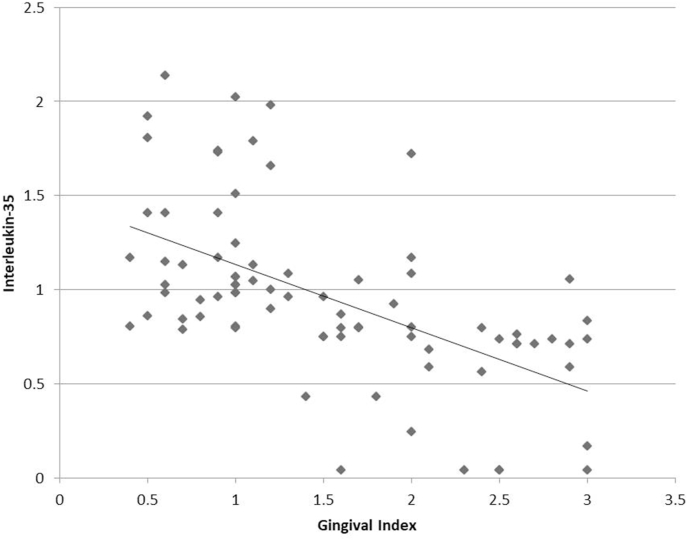

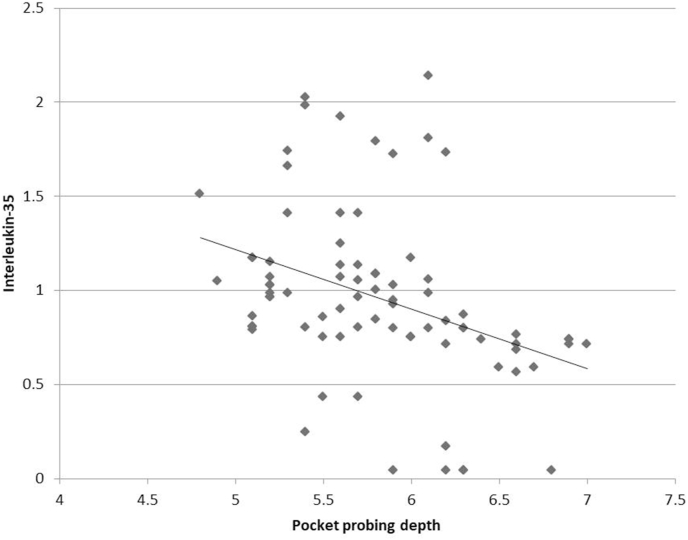

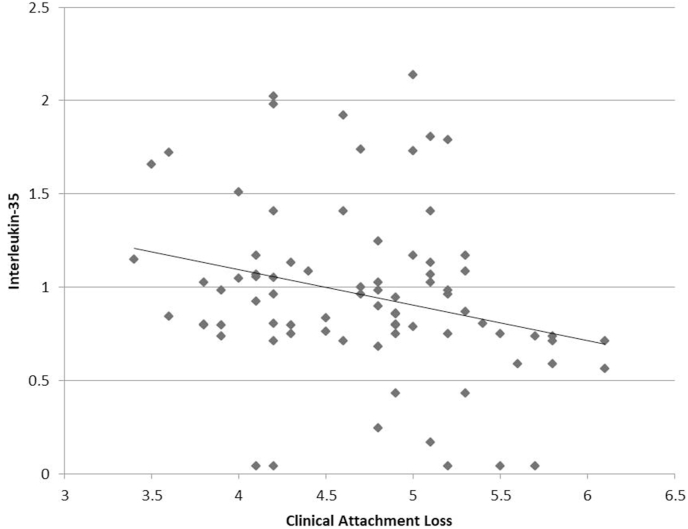

The correlation among biological and clinical parameters was analyzed with Pearson's correlation coefficient (Table 3). A highly significant negative correlation (p < 0.001) was found between IL-35 and clinical parameters of PI (r = −0.475), GI (r = −0.569) and PPD (r = −0.365) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3). For CAL, there was a significant negative correlation with IL-35 (p < 0.05), albeit a weaker one (r = −0.262) (Fig. 4). Since the lower values of clinical parameters depict healthier periodontium, a negative correlation with IL-35 means increased GCF concentration of IL-35 as the periodontal health improved.

Table 3.

Correlation between GCF Levels of Inteleukin-35 and clinical parameters.

| R value | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| PI | −0.475 | <0.001* |

| GI | −0.569 | <0.001* |

| PPD | −0.365 | <0.001* |

| CAL | −0.262 | 0.0189# |

Pearson's Correlation test.

*Highly significant #Significant.

Fig. 1.

Correlation between plaque index and GCF Interleukin-35 levels.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between gingival index and GCF Interleukin-35 levels.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between pocket probing depth and GCF Interleukin-35 levels.

Fig. 4.

Correlation between clinical attachment loss and GCF Interleukin-35 levels.

4. Discussion

Periodontitis is an immune-inflammatory disease driven by host cell response to periodontopathic bacteria which initiate local degenerative pathways leading to periodontal tissue destruction. Given that the host cell response induces the release of inflammatory cytokines, attempts have been made to elucidate the assortment of pathways by the way in which these specific immune responses are elicited. CD4+ Th cells play an essential role in regulating immune responses in inflammatory diseases such as periodontitis. Pro-inflammatory cytokines further the progression of inflammation whereas anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β exert to promote healing and inhibit inflammation.21,22

Interleukin-35 is a relatively new immunosuppressive or anti-inflammatory cytokine that has drawn considerable attention. It is a dimeric protein with two subunits, IL-12A and Epstein-Barr virus-induced gene-3.23 IL-35 is expressed by both resting and activated T-regs but not by effector T cells.24 In various auto-immunity models, for instance, experimental colitis and collagen-induced autoimmune arthritis, IL-35 demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties.11,25 The purpose of IL-35 in periodontal inflammation remains a relatively unexplored area, hence in this study the IL-35 levels in the GCF of periodontitis patients, pre and post non-surgical periodontal therapy at an interval of one week till three weeks was assessed.

In quite a few in-vitro and preclinical studies the role and mechanism of IL-35 have been assessed. IL-35 demonstrated an inhibitory effect on alveolar bone resorption in an animal model.26 In concomitant research, it inhibited the production of IL-6 and IL-8 which are pro-inflammatory in nature.27 The studies in clinical settings, however, have given conflicting results regarding the IL-35 levels in periodontal health and disease. Kalburgi et al. compared the IL-35 levels in gingival tissues of healthy controls, chronic and aggressive periodontitis patients, and found it to have a maximum expression in chronic periodontitis followed by aggressive periodontitis and healthy controls.28 Other authors however found the concentration of IL-35 in GCF to be farther in the healthy group compared to the gingivitis and chronic periodontitis group.16 The results of our study demonstrate that the concentration of IL-35 was highest three weeks post-SRP when the tissues were the healthiest.

The clinical parameters were found to be negatively related with the GCF levels of IL-35 in the current study. These results confirm the increase in IL-35 levels within the gingival sulcus as the healing takes place following SRP. In a similar study rather, contrary results were found compared to ours. The authors established a positive correlation amongst clinical parameters and GCF IL-35 levels which was attributed to the decline in inflammation diminishing the expression of T-reg leading to reduced IL-35.15 The two studies had few variations, an important one being the time interval at which GCF was collected post SRP. While the present study collected samples at weekly intervals till the third week, the comparative study collected GCF samples at the first and third months.

In a latest systematic review, the current evidence available regarding the role of IL-35 in pathogenesis of periodontal disease was scrutinized.29 Three subclinical studies, ten cross sectional investigation and two randomized clinical trials were finally included in the review. Cross sectional observatory studies in humans confirmed the existence of elevated levels of IL-35 in serum, saliva, GCF, and gingival biopsies of periodontitis patients. Two included clinical trials demonstrated that non-surgical periodontal therapy could downregulate IL-35 production in chronic periodontitis patients. This conclusion was different from our results as both the trials included in this review used different methodology than ours and the time of collection of GCF after non surgical periodontal therapy was also different. The review itself though confirming the undeniable role of IL-35 in pathobiology of periodontitis, remained inconclusive about its functional pattern.

The routine measures of periodontal disease are probing depth, indices for inflammation such as gingival index, and radiographic measure of bone loss around teeth. These indices are customarily used to measure the success of periodontal therapy nonetheless are insufficient to predict disease activity. The biomarkers of inflammation tend to predict the actual environment present deep within the periodontium through which the success or failure of therapy could be predicted. Non-surgical periodontal therapy appears to substantially enhance levels of IL-35 within the gingival crevice which might be owing to the healing of the periodontal tissues. Evaluating its levels might help to monitor the response to therapy and the current state of inflammation within tissues. Further investigating its level for a longer duration throughout health and disease may prove it to be a valuable biomarker for periodontal diagnosis. Future studies may seek to develop its use as a therapeutic agent in addition to being a prognostic indicator.

5. Conclusion

Within the limitations of the present study, it can be suggested that with the healing of the formerly diseased periodontal tissues, there is a substantial increase in the levels of IL-35 in GCF. Therefore, IL-35 can be considered as a potential inflammatory marker of periodontal health and disease. However, further studies with greater sample size and a longer follow-up are needed to validate IL-35 as a potential biomarker of periodontal health and disease as well as its possible therapeutic application in periodontitis.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Sanz M., Marco Del Castillo A., Jepsen S., et al. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: consensus report. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47:268–288. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishikawa I., Nakashima K., Koseki T., et al. Induction of the immune response to periodontopathic bacteria and its role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Periodontol. 1997;14:79–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00193.x. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garlet G.P. Destructive and protective roles of cytokines in periodontitis: a re-appraisal from host defense and tissue destruction viewpoints. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1349–1363. doi: 10.1177/0022034510376402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J.-M., An J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2007;45:27–37. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e318034194e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon J.G. Inflammatory cytokines in nonpathological states. News Physiol Sci Int J Physiol Prod Jointly Int Union Physiol Sci Am Physiol Soc. 2000;15:298–303. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.6.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosmann T.R., Sad S. The expanding universe of T-cell subsets: Th1, Th2 and more. Immunol Today. 1996;17:138–146. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yucel-Lindberg T., Båge T. Inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Expet Rev Mol Med. 2013;15 doi: 10.1017/erm.2013.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takashiba S., Naruishi K., Murayama Y. Perspective of cytokine regulation for periodontal treatment: fibroblast biology. J Periodontol. 2003;74:103–110. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballini A., Cantore S., Farronato D., et al. Periodontal disease and bone pathogenesis: the crosstalk between cytokines and porphyromonas gingivalis. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2015;29:273–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawant D.V., Hamilton K., Vignali D.A.A. Interleukin-35: expanding its job profile. J Interf Cytokine Res Off J Int Soc Interf Cytokine Res. 2015;35:499–512. doi: 10.1089/jir.2015.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niedbala W., Wei X.-Q., Cai B., et al. IL-35 is a novel cytokine with therapeutic effects against collagen-induced arthritis through the expansion of regulatory T cells and suppression of Th17 cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:3021–3029. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J., Zhang Y., Wang Q., et al. Interleukin-35 in immune-related diseases: protection or destruction. Immunology. 2019;157:13–20. doi: 10.1111/imm.13044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khoshkhui M., Alyasin S., Sarvestani E.K., Amin R., Ariaee N. Evaluation of serum interleukin- 35 level in children with persistent asthma. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2017;35:91–95. doi: 10.12932/AP0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y., Li D., Li Y., et al. Interleukin-35 upregulates OPG and inhibits RANKL in mice with collagen-induced arthritis and fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Between Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found. USA. 2016;27:1537–1546. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3410-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raj S.C., Panda S.M., Dash M., et al. Association of human interleukin-35 level in gingival crevicular fluid and serum in periodontal health, disease, and after nonsurgical therapy: a comparative study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2018;9:293–297. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_51_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Köseoğlu S., Sağlam M., Pekbağrıyanık T., Savran L., Sütçü R. Level of interleukin-35 in gingival crevicular fluid, saliva, and plasma in periodontal disease and health. J Periodontol. 2015;86:964–971. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flemmig T.F. Periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:32–38. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silness J., Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–135. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Löe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38(Suppl):610–616. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fatima T., Khurshid Z., Rehman A., Imran E., Srivastava K.C., Shrivastava D. Gingival crevicular fluid (GCF): a diagnostic tool for the detection of periodontal health and diseases. Molecules. 2021;26:1208. doi: 10.3390/molecules26051208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dinarello C.A. Interleukin-1 beta and the autoinflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2467–2470. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0811014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bettini M., Vignali D.A.A. Regulatory T cells and inhibitory cytokines in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:612–618. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collison L.W., Vignali D.A.A. Interleukin-35: odd one out or part of the family? Immunol Rev. 2008;226:248–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collison L.W., Workman C.J., Kuo T.T., et al. The inhibitory cytokine IL-35 contributes to regulatory T-cell function. Nature. 2007;450:566–569. doi: 10.1038/nature06306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wirtz S., Billmeier U., Mchedlidze T., Blumberg R.S., Neurath M.F. Interleukin-35 mediates mucosal immune responses that protect against T-cell-dependent colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1875–1886. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cafferata E.A., Terraza-Aguirre C., Barrera R., et al. Interleukin-35 inhibits alveolar bone resorption by modulating the Th17/Treg imbalance during periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47:676–688. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shindo S., Hosokawa Y., Hosokawa I., Shiba H. Interleukin (IL)-35 suppresses IL-6 and IL-8 production in IL-17A-stimulated human periodontal ligament cells. Inflammation. 2019;42:835–840. doi: 10.1007/s10753-018-0938-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalburgi N.B., Muley A., Shivaprasad B.M., Koregol A.C. Expression profile of IL-35 mRNA in gingiva of chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis patients: a semiquantitative RT-PCR study. Dis Markers. 2013;35:819–823. doi: 10.1155/2013/489648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidlin P.R., Dehghannejad M., Fakheran O. Interleukin-35 pathobiology in periodontal disease: a systematic scoping review. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:139. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01515-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]