Abstract

Background:

Individuals with problematic gambling, alcohol and substance use commonly report lower employment rates and more employment-related problems such as job loss, work conflicts and poor performance.

Method:

A thematic qualitative analysis was conducted to extract employment-related themes from 21 sets of addiction counselors’ case notes of couple therapy sessions (average 10 sessions per case) from a randomized controlled trial of Congruence Couple Therapy (CCT). Case notes were examined for the types of employment issues to answer the research question: What are the interconnections of employment, couple adjustment and addictive behaviors as revealed in the CCT counselors’ case notes?

Results:

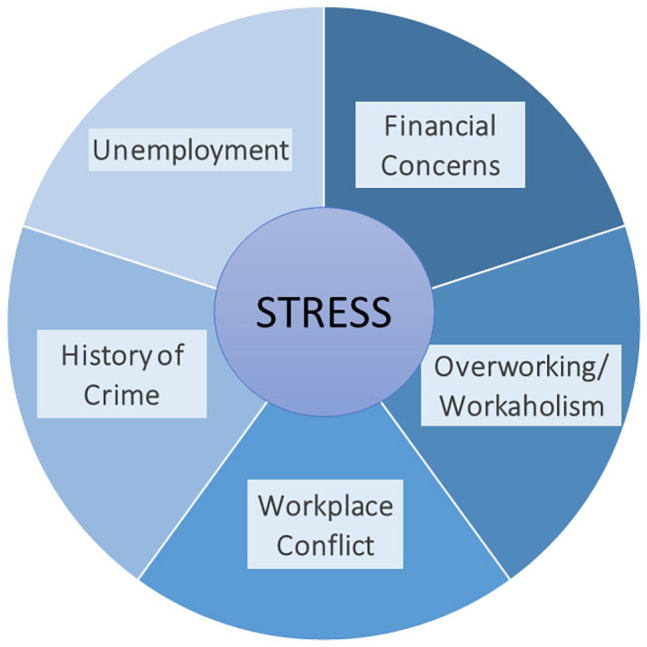

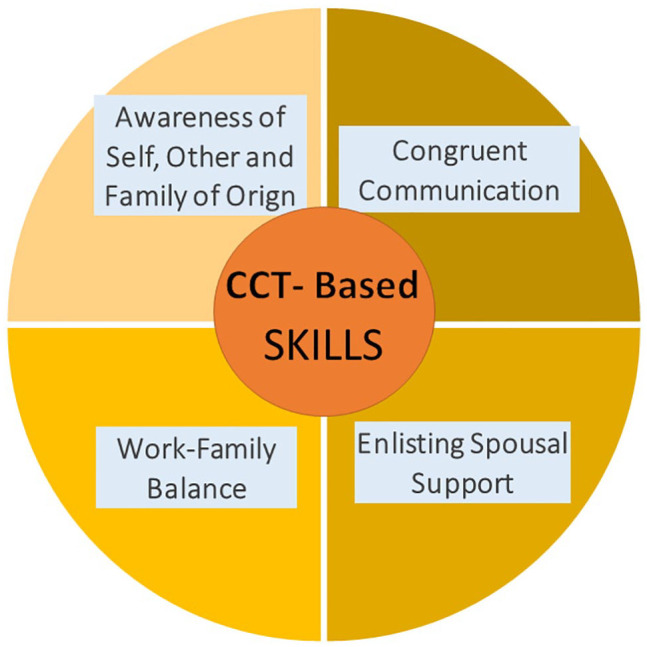

Five key areas of employment-related stress were identified: (1) unemployment, (2) financial concerns, (3) history of crime, (4) overworking and workaholism, and (5) workplace conflict. These themes interacted negatively with couple adjustment and addictive behaviors. Using CCT as an intervention, clients gained skills in 4 areas transferred to employment: (1) awareness of self, other and family of origin, (2) congruent communication, (3) work-family balance, and (4) enlisting spousal support. These themes intersected with enhanced work functioning and reduced stress, alcohol use and gambling.

Conclusion:

Employment problems negatively impacted addictive behaviors, couple adjustment and well-being of partners and clients. Skills and awareness gained in CCT promoted changes in addicted clients’ employment functioning and coping with employment stress. The domains of work and couple adjustment are mutually influential in increasing or reducing stress with implications for addiction recovery. CCT as a viable intervention for enhancing employment function should be further studied.

Keywords: Alcohol use, substance use, gambling, employment, work, stress, skills, recovery, family of origin, intimate partner, work-family interaction, Congruence Couple Therapy

Employment difficulties and concerns are common in individuals with alcohol and substance use disorders.1-3 Individuals with substance use find it harder to acquire and maintain employment as they are often challenged by lower educational credentials, poor interpersonal skills, domestic violence, criminal record, and poor work history.4-6 Unemployment is higher among those with severe forms of addiction cutting across all types of substances. 7

Employment problems also extend to behavioral addictions such as problem gambling. Gambling in general is associated with higher rates of future unemployment and higher negative associations are found among the heaviest gamblers. 8 Among disordered gamblers, unemployment is 2 times higher than social and recreational gamblers. 9 Absenteeism, lateness, poor job performance, moodiness and irritability, and frequent job loss render disordered gamblers less employable.9,10 These employment problems often co-occur with mood and personality disorders and family discord.9,10 Further, employment problems and instability in gamblers were found within a structure of psychological distress and poor psycho-social functioning reflected in separation and divorce, illegal acts, suicidal ideation and attempts that are associated with impulsivity and anti-social factors. 11 Sixty percent of male prisoners in 3 Australian prisons reported a lifetime prevalence of problem gambling and 18% reported offenses related to problem gambling, with comparable rates among female prisoners.12,13

Unemployment and substance use have a bidirectional relationship, as they mutually influence each another.6,7,14 Employment is a key index of treatment completion and successful recovery,6,15-17 and ranked as a top priority for clients in recovery.2,15,16 The benefits of employment extend to improved self-esteem, better quality of life, life satisfaction, happiness, lower stress, and lower drug craving.1,18

Employment and Couple Relationship

Employment provides a source of income and contributes to a positive family environment. 19 Conversely, unemployment negatively impacts the couple relationship 20 and the well-being of both partners. 21 Job insecurity is correlated with decreased relationship satisfaction. 22 Higher stress levels, greater pessimism, and low life satisfaction have been reported in couples where one partner was unemployed. 23 Unemployment can create couple conflict and contribute to divorce, while longer period of unemployment is a strong predictor of marital separation. 24

Work-family conflict has been an area of study showing that incompatible work and family demands are associated with lower couple relationship quality. 25 Work-related stress, exhaustion, and negative emotions may spill over into the home and negatively impact couple relationship.26,27 On the other hand, couple distress can also negatively impact work performance, 28 but spousal support acts a protective mechanism against work stress. 29 One partner’s employment can enhance the other’s employment through verbal persuasion and vicarious experience in sharing management of work issues. 30 Although the intersections of employment and couple relationship have been demonstrated in various studies, work and family interaction is an area that has not been explored in the field of addiction treatment and recovery.

Congruence Couple Therapy

CCT is a 4-dimensional systemic model consisting of “four doors” that are used as entry points for increasing awareness and alignment of intrapsychic, interpersonal, intergenerational, and universal-spiritual functioning in a couple unit. Its goal is to enable members in a couple to become more aware of themselves and each other to improve couple adjustment.

The intrapsychic door increases awareness of one’s inner world in terms of thinking, feeling, perceiving, and expectations in a relationship. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions interact and together can form a recursive vicious cycle. 31 Conversely, this pattern, once discerned, can be disrupted to generate a more benevolent and productive cycle. The interpersonal door develops awareness of self, other, and context in an interaction to facilitate the practice of congruent communication. Effective communication enhances the couple’s ability to problem solve, negotiate, and respond to stressful situations. Instead of disconnecting from one’s inner experience, a person learns to use increased awareness as information to make choices about how to communicate, cope and act. Gaining clarity into the origins of one’s reactions stemming from childhood adverse experiences (ACEs) including sexual, emotional and physical abuse, neglect, loss and abandonment, a person can choose new ways of emotion regulation, communication and self-management. The intergenerational dimension focuses on how family of origin and ACEs affect emotional reactivity and disconnection from one’s inner experience. ACEs could bring about difficulty with authority figures, avoidant and incongruent communication, and intolerance of differences. The fourth dimension is the universal-spiritual that validates the human universal yearnings for connection, safety, and worth. The universal-spiritual dimension emphasizes intrinsic human worth, self-affirmation, and self-care. It also connects a person with their higher aspirations for purpose, meaning, and desire to contribute to the larger good. 31

Purpose of the Study

This study is a secondary analysis of the data collected from a the RCT comparing the effectiveness of the systemic model of CCT and the individual-based treatment-as-usual (TAU) for alcohol use and gambling disorders and comorbidities. 32 Employment was noted by counselors and researchers during the RCT as an ongoing issue that was central to addiction and couple adjustment among the couples with addictive disorders. This observation gave the impetus for the present study to further analyze the interconnections of employment, couple adjustment and addiction in order to understand their interacting dynamics. CCT participants gave consent for the use of their data for secondary analyses for addiction and couple therapy related research. The randomized trial was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board—Health Panel, University of Alberta Pro00062248.

Research Question

Based on counselors’ case notes for couples enrolled in CCT regardless of treatment completion, where one partner met gambling and/or alcohol use disorder based on DSM-5 criteria in the moderate to severe range, we posed the research question: What are the interconnections of employment, couple adjustment, and addictive behaviors as revealed in the counselors’ CCT case notes?

Method

Twenty-four sets of couple case notes entered by 5 addiction counselors were reviewed initially for explicit mention of employment concerns, including couples who did not complete the full set of CCT intervention (average 12 sessions). Using the method of thematic analysis described by Braun and Clarke, 33 we analyzed the counseling case notes to answer the research question. Three cases with no explicit mention of employment-related issues were excluded. The couples in the 21 cases completed an average of 10 sessions of CCT (range 2-20). Case notes from the control group that underwent treatment-as-usual (TAU) with an individual-based approach were not available for analysis.

Data analysis

Counselors’ notes were written following a reporting structure of the Themes, Interventions, clients’ Responses and Plan (TIRP). Each set of case notes was first examined for content of employment stress. Initial codes for employment-related issues were extracted and further analyzed in relation to couple adjustment and addictive behaviors. Counselors’ interventions and the clients’ responses to CCT were analyzed in terms of whether and how the interventions improved couple relationships and the clients’ functioning at work. The naming of themes and the thematic analyses were corroborated by the 2 authors to increase reliability and validity. Themes were grouped to create higher-level themes across the 21 cases to answer the research question under 2 broad categories of (1) employment-related stress (2) employment-related skills and awareness and their connections with couple adjustment and addictive behaviors.

Results

Sample characteristics

Twenty-one out of 24 (88%) couples featured employment issues as a concern in the counselors’ case notes. In the 21 couples, primary clients reported a mean age of 44.2 years, majority were males, Caucasian, non-religious, with secondary or less education. Slightly more than half of primary clients were working in the last 30 days (52.4%), had a household income >$100 000, and majority had adequate housing. Percentage of primary clients with AUD-only was 71.4% based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria (M = 8.4, SD = 2.0) versus 23.8% of partners (M = 8.2, SD = 2.8); 4.8% of primary clients and none of the partners had GD only (M = 7.0, SD = 1.0); 23.8% of primary clients and 4.8% of partners had both disorders. AUD scores were in the severe range and GD scores were in the moderate-severe range. 34 Jointly addicted couples with both partners diagnosed with AUD and/or GD was 28.6%. Primary clients reporting a history of 1 or more ACEs was 57.1% and partners with ACE history was 52.4%. For demographic details, see Table 1. Note that these demographics are based on the sample included in this secondary analysis and may differ from those reported in the main RCT.

Table 1.

Demographics of clients and partners (N = 42).

| Clients (n = 21) | Partners (n = 21) | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 44.2 (10.4) | 43.1 (11.0) |

| Sex at birth | ||

| Female | 4 (19.0) | 17 (81.0) |

| Male | 17 (81.0) | 4 (19.0) |

| Gender orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 19 (90.5) | 19 (90.5) |

| Homosexual | 2 (9.5%) | 2 (9.5) |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married | 12 (57.1) | 12 (57.1) |

| All others | 9 (42.9) | 9 (42.9) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 17 (81.0) | 19 (90.5) |

| Other | 4 (19.0) | 2 (9.5) |

| Education | ||

| Secondary or less | 13 (61.9) | 6 (28.6) |

| Post-secondary | 8 (38.1) | 15 (71.4) |

| Employment | ||

| Working | 11 (52.4) | 14 (66.7) |

| Not working | 10 (47.6) | 7 (33.3) |

| Household annual income | ||

| ⩽$100 000 | 11 (52.4) | 9 (42.9) |

| >$100 000 | 10 (47.6) | 12 (57.1) |

| Household income meeting living needs | ||

| No | 4 (19.0) | 8 (38.1) |

| Sleeping place last 30 days | ||

| House/apartment | 18 (85.7) | 20 (95.2) |

| Group home | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) |

| Other | 2 (9.5) | |

| Religion | ||

| Christian (Protestant and Catholic) | 5 (23.8) | 3 (14.3) |

| Other (Hindu, Jewish, and other) | 7 (33.3) | 6 (28.6) |

| None | 9 (42.9) | 12 (57.1) |

| AUD (DSM-5) | 15 (71.4) | 5 (23.8) |

| GD (DSM-5) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| AUD/GD (DSM-5) | 5 (23.8) | 1 (4.8) |

| One or more adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) | 12 (57.1) | 11 (52.4) |

Themes

Employment stress refers to the perceived psychological load and demands related to employment that tax or strain the individual’s coping ability. Five key areas of employment-related stress were identified across the 21 cases, namely, (1) unemployment, (2) financial concerns, (3) history of crime, (4) overworking and workaholism, and (5) workplace conflict. Using the couple relationship as a medium for personal and interpersonal development, counselors’ notes indicated that the couple gained skills and awareness in 4 areas of skill and personal development transferrable to employment: (1) awareness of self, other and family of origin influences, (2) congruent communication, (3) work-family balance, and (4) enlisting spousal support. Links to addiction are described. Pseudonyms are used in reporting the results.

Employment-related stress

Unemployment

Unemployment impacted the family’s financial stability and how the individual with addiction was viewed by others and by themselves. It eroded a sense of personal adequacy and capability, altering the couple dynamics and posing a risk to relapse (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Employment-related stress.

Link to addiction

Those in active addiction had difficulty finding and maintaining employment due to their erratic lifestyle, absenteeism, and unsatisfactory performance when addiction became a preoccupation, for example, Derek and Dilys are both in active addiction and unable to maintain employment due to their lengthy and frequent alcohol binges. Individuals with substance-using or gambling problems were compromised in their concentration, judgment, and decision-making to keep their work and productivity on track, for example, Fay shared how Frank’s drinking had increased to the point he was not functioning at work, and she could see how stressed out he was and that he also wanted to let go of the business and the workers they hired. Negligence in managing their tasks and duties was detrimental to their work and business income. Unfortunately, employers were not always sympathetic or forgiving:

Dylan has lost his job as a result of his misuse of company funds. . . Dylan noted feeling hurt that his employers did not acknowledge his addiction or his willingness to repay his debts in their dismissal letter.

Operating safety-sensitive equipment at work under the influence of alcohol or other substances jeopardizes lives and safety and resulted in suspension or dismissal, for example, The husband shared that his workplace suspended him for being intoxicated on the job.

Employment is an important marker from which others view a person as a contributing member in society. Futility in attaining employment and loss of esteem in the eyes of family members re-ignited feelings of inadequacy, for example, Connor overheard mom say to dad after he lost his job again that she loves him, but she doesn’t know if she can afford him. Devoid of routine and structure, social isolation and boredom set in leading to the use of alcohol:

Jared claimed that being unemployed brought along boredom and alcohol “took the edge off,” but eventually he “went too far.” This writer tried to push Jared to examine his internal triggers and struggles to connect to his feelings.

Spousal and family impact

The drawn-out process of job search was taxing and discouraging not only to the addicted individual but also affected the partner and the couple relationship:

Clear themes of workplace stress (he from his unemployment and she at work) predominate, and they lacked coping skill or ability to support one another. . . She claimed that coming home to her husband drinking/drunk after a stressful day put strain on their relationship.

He drank during the week. . . they got into a confrontation. Jane described that she hit Jared with a cell phone and Jared pushed her back and she threw the phone. They called the cops for the first time in their lives because things were so out of control, but no charges were laid. This writer inquired into Jared’s trigger for drinking. . . he struggled to connect with his internal triggers, but this writer tried to help validate that feeling around his unemployment would be challenging. He then opened up that he feels bad about still being unemployed and no longer having a “career” let alone a “J-O-B.” He believes his parents would be disappointed in him if they could see him unemployed and drinking. He also opened up about increased anxiety and depression. Jared presented as very unkempt during today’s session.

A sense of helplessness and inadequacy was a recipe for relapse, for example, Wyatt feels powerless and helpless in contributing to the financial well-being of the household and his drinking is more frequent and intense.

Shifting financial responsibility on to the earning partner created an unequal couple dynamic, e.g., Sara reported she felt securing work would “even the playing field,” as she would be contributing to the household financially, which she believes Sue respects more. Resentment also developed in the earning partner who felt their hard work and finances were taken for granted, for example, she “had enough” of Wyatt’s drinking, him not paying bills, “checking out” etc. and asked him to leave the house. Marital breakdown added another layer of stress to the addicted client, precipitating relapse:

Matt reported he had trouble finding work which led to relapses with increasing frequency: monthly, then twice monthly, then weekly. Melanie indicated that he still has places, or “crackhouses” he can go to use and would disappear for 2 days at a time. Melanie reported this resulted in a “severe relapse/meltdown” last year when she left Matt. Matt reported that with Melanie away, he “had to step back.” However, Matt reflected that “when things go south” he “just wants to run.”

Financial concerns

Financial concern was experienced by both members in the couple due to lost income, debt, spending on addiction and financial uncertainty.

Link to addiction

Individuals spent inordinate amounts of money on their addiction that eroded trust in the handling of finances, for example, Hannah explained to her husband how he broke her trust in spending money on alcohol and now to rebuild her trust she wants to see the receipts to soothe her fears over their finances. Poor financial decisions and overspending had cumulative consequences, for example, Kyle is currently dealing with a lot of past debts and back-taxes, which is a stressor for him. Failed attempts to make things right led to addictive behaviors bringing on more self-derision:

Writer reflected back the yearning to have the family he always wanted is motivating him to try to fix the financial situation with a quick Lotto max win. . .Writer reframed the husband’s statement “I am retarded” because of the poor business decisions he made to “I made some poor financial decisions” or “Everyone makes mistakes and I can learn from my past.”

For disordered gamblers, gambling losses led to crimes of fraud and theft to pay off financial debts, for example, Dylan has lost his job as a result of his misuse of company funds.

Spousal and family impact

Financial instability was compounded by child or elderly care responsibilities. Partners were forced to manage family finances including bills and rent. In severe cases, partners had to borrow money from friends and family, for example, The husband shared he owes the father in-law money and appreciated his loaning them the money. Shouldering all these family responsibilities led to a build-up of the partner’s resentment and burn-out that drove a growing wedge in the couple relationship:

Lisa gave another example of a missed bill which she noticed. . . in the past [she] would have attacked Larry blaming him and his drinking for missing the bill. It would have been an excuse again for her to attack and for him to avoid and drink. We discussed the blame/avoidance dance that the two of them were engaged in.

Secrecy around the family’s financial situation and its discovery came as a shock and was traumatic for the partner, in many cases related to gambling:

Eva described a big blow-out that occurred when she discovered missing finances in their bank account that also had to do with their mortgage. This happened a few years ago and up to this point Ed had been managing to keep his gambling a secret. This was a shattering event and she said that for several months after the discovery there were ugly arguments and fights and that they had to take out another mortgage.

Trust was eroded over time through repeated betrayals:

Hannah was back into dark hole once again when she was betrayed by his addiction. She valued the power of money so the loss of all the money to gambling was something she could not fathom, could not understand, could not forgive, as it was such a huge betrayal.

In some cases, the addicted client became aggressive and violent in an attempt to regain power and control in the family, for example, He admitted he wanted to hurt her back as he was hurting still, started acting out like his parents would have to each other.

History of crime

Having a criminal record was a major barrier to employment and created stigma. Assumptions of incompetence, unreliability, and lack of responsibility were often made by the employer.

Link to addiction

Addiction led to criminal behaviors in different ways. Some ended up with criminal records being charged for domestic violence or sexual assault, for example, Aaron disclosed that he was charged with sexually assaulting a child when inebriated and subsequently incarcerated with loss of his job. Gamblers were more likely to be charged with fraud or theft to cover their debt. When incarcerated, the individual suffered loss of their job and income, for example, Aaron disclosed letting his dad and boss know that he will most likely be going to jail. Decision was made to sell Aaron’s portion of the family business. The shame and guilt over criminal activities increased the risk of substance use, for example, Aaron felt blame and shame and had to be encouraged to open up about feelings and thoughts rather than shutting down and withdrawing.

Spousal and family impact

The stigma of crimes committed by the person with addiction that cast a long shadow, for example, Tyson lost his job due to his criminal record in the past – an assault charge from 10+ years ago. The stigma of criminality led to alienation from family and social support. A partner’s past trauma was triggered by the current event of loss and abandonment when the addicted individual was sent to jail with the potential impact on the family:

Increased awareness of Alyssa’s grief and loss around Aaron’s sentencing. Her past abandonment by the previous father of her children was being triggered. Alyssa shared her concerns about talking to her children about the potential outcome of Aaron’s incarceration. Talked about anticipated loss around the potential of Aaron not being present during their baby’s development.

Overworking and workaholism

Overworking was found in some individuals taking on excessive responsibility or expending an extreme number of hours at work that resulted in negative consequences in other areas of their life, such as interpersonal relationships, well-being, and health. When overworking took on the quality of compulsion and the inability to scale down despite negative consequences, a case of workaholism likely existed.

Link to addiction

Work in some cases was used as a form of avoidance, to get an adrenaline rush of excitement to compensate for dysphoria and to boost one’s low self-worth:

Frank also was letting his ego get out of control when he would rent more land and hire more people to be “successful.” He admitted he was overworking, overweight and drinking heavily at that point which resulted in injuries to himself by falling down the stairs.

Workaholism as a behavioral addiction was found in some cases to accompany substance-related and gambling disorders, for example, Dylan noted an escalation in his drinking and use of cannabis in the last week. . .he was able to link the increase to being absorbed in work.

Overworking or workaholism was seen as a virtue and a strong work ethic was inculcated in a child early in life, for example, The husband made the connection of how his own dad uses “workaholism” to hide out. . .and “lives to work.” In other cases, work was a way to avoid conflict and communication with the partner and family. These were often patterns learned from childhood:

Dylan would “retreat” on a bad day. . .and linked his avoidance to having a lot of shame and using work and alcohol to hide and numb. . . Writer inquired whether Dylan’s inner critic was completely him, Dylan acknowledged that the voice does come from his father.

As children, some individuals were valued mainly for their performance and achievement and sought to derive worth as an adult by proving themselves through promotions, status, and financial rewards from work, for example, Both Jared & Jane grew up in homes that emphasized keeping up appearances, with less focus, if any, on emotional needs. Derek was bent on proving himself at work, straining to receive the approval from his boss and accolades from his company to the detriment to his family relationships as a way to compensate for the lack of intrinsic self-worth:

Derek became a workaholic, obsessed with money and power. Had “blind ambition” and was driven to make more and more money and bigger deals with the company. Had multi-millionaire clients. Taking course after course and became obsessed with night school to gain more prestige and power while working full time. Drinking increasing and was part of working with clients. Also used cocaine. Was a wheeler and dealer in high stakes corporate world. Wanted more and more and more of money, power, control, drinking, women. Underneath power, money etc. was insecurity. He said he was making up for what he wasn’t, always felt second best, always felt angry, insecure, inferior and like a failure.

One addicted individual developed the fear of communicating her limits to her boss because of family rules around work and perfectionism learned in her childhood:

We once again discussed Sue speaking to her boss or office manager about her workload. Sue claimed she feels embarrassed about screwing up and doesn’t like to admit she can’t do it all.

Spousal and family impact

A partner inadvertently reinforced the over-achieving and over-working habits of the primary client because it brought prestige, luxury, and pride to the family:

Dylan also receives validation from Diana with respect to his work success, and this is the only area that Diana validates him, so there is further incentive to spend more time at work and be successful.

Depleted of energy from overworking, the couple relationship suffered, for example, Matt is exhausted after work, secludes himself watching TV or playing games on his phone; Melanie is frustrated. Resentment accumulated in the partner due to an absent husband, for example, Jane felt isolated and lonely at home with a new baby while he overworked and spent time with others, and an absent and neglectful parent due to workaholism brought ire from his children:

Diana discussed how their son Dennis holds a lot of anger toward Dylan. Dylan said that he wants to repair the relationship, understanding why Dennis still holds anger about him not being emotionally available.

Workplace pressure and conflict

Addicted clients faced challenges negotiating workplace relationships leading to distress that precipitated substance use and relapse.

Link to addiction

Most individuals with addiction had a history of ACEs that led to breaches in trust and relationship with their primary caregiver, which was replicated in the workplace. These “internal working models” of communication, attitude, view of self and other, commonly showed up at work with a supervisor or someone perceived as an authority figure. Trouble with one’s boss is a typical workplace conflict along with perception of bullying and rivalries with co-workers:

Matt is struggling with some difficult coworkers, feeling unjustly criticized and undermined. . . Matt struggles to find other ways to “release the pressure valve” other than drinking or using cannabis.

Growing up in a family where emotions were not allowed or acknowledged, compliance was easier than making one’s limits and feelings known at work:

Sue indicated that she was met with a lot of pressure and deadlines, leaving her feeling a sense of panic, flight, and activation the whole day. She noted at one point she cried at her desk, which she “hated”. . .Writer asked what it would be like to discuss her experience and feelings about work demands with her boss. Sue became tearful, indicating it would be really difficult to be vulnerable and express feelings. . . Sue would often drink before coming home and is yet to find a new ritual to help her cope with the stressful workday and transitioning home.

Dylan spoke about the influence of his upbringing on his intimate relationship and work:

Dylan agreed that intimacy has always been a challenge. He reported there were no hugs or verbal expressions of love as a child. “I never learned how to express my emotions.” At work, Dylan said that he can be a “cold-hearted ass.”

Some workplace cultures involved socializing over alcohol or substance use with co-workers and while entertaining clients. To assert one’s difference while maintaining these working relationships required tactful communication, however, it could be used as an excuse to indulge in drinking,

Melanie has asked him not to go to the bar with his coworkers after shift and he will return drunk later that night. Matt reported a lot of alcohol and some cocaine use on the job – “I used the work culture to my advantage,” where drinking in the afternoon or after a shift was ok.

Partner and family impact

Difficulties or exhaustion from work spilled over into the couple relationship in the form of withdrawal and substance use:

Matt is exhausted after work, secludes himself watching TV or playing games on his phone. Melanie is frustrated; feeling taken for granted, nags and complains. Matt minimizes her concerns, gets irritated, he shuts down more. Matt has been smoking cannabis nightly this past week, frustrating Melanie further.

Repeated “slip-ups” into drinking or substance use could precipitate intimate partner violence, for example, When Matt slips up, Melanie stated that she will “drift off and pull away” then blow up at him later. She admitted to attacking him physically with a slap across the head if they are having an argument. Most clients did not feel safe disclosing work-related feelings and problems with their partner due to lack of safety in doing so in their family of origin experiences. The partner felt isolated and distanced. Conflict or power dynamics at home was replicated in the workplace, especially in family-run businesses. For example, an over-functioning wife could curb the initiative of an under-functioning husband affecting how the business is run, for example, Olivia feels she needs to rush in and fix things; Oscar feels deflated and deferring to his wife’s decisions.

Summary

Themes related to employment stress and couple stress were not isolated and impervious to each other but were closely intertwined. Work stress compounded family stress that triangulated with addiction as a way of regulating a range of emotions. The interaction of work-related stress and couple conflict led to feelings of helplessness, hopelessness and powerless that often precipitated or escalated substance use and relapse in a recursive and amplifying cycle.

Skills and awareness developed through Congruence Couple Therapy

The following themes described how the work done with the couple with CCT contributed to reducing employment stress and problems and how the awareness and skills gained in couple therapy are transferable to work functioning and lessened the need to resort to addictive behaviors (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Employment-related skills.

Awareness of self, other, and family of origin

The workplace is a complex and dynamic environment with many interactions throughout the day with co-workers, bosses, and customers. Hence awareness of one’s feelings, thoughts, perception, expectations, and beliefs is important to workplace communication and functioning, for example, Dylan said that he feels their couple sessions are like school for him where he is learning how to identify, feel, and express his emotions. Working with CCT, many addicted clients became aware of their intrapsychic world for the first time, for example, the main function alcohol served was to avoid. Ed avoided his whole life, so in sobriety it was hard to be present, express feelings and not succumb to default coping mechanisms. Ed was facing himself for first time in his life.

Equally important to awareness of self is the awareness of other. Awareness of other people and what motivated their actions was paramount to how clients conducted themselves in the workplace, for example, Writer reviewed steps of acknowledging and naming our internal experience, then attending to it with self-care and connection with others. Closed the session by exploring what each yearns to hear from each other. When unclear about other’s expectations and reactions, CCT encouraged individuals to ask questions to learn about the other and situations, leading to better mutual understanding and cooperation with bosses, co-workers, employees and customers, for example, They agreed that this “cleaning up” process at work is reflective of the work they are doing in their marriage.

Couples were prompted to connect their present behaviors with what they learnt in their family of origin and then to make new choices to improve their communication and emotion regulation. This is particularly important in clients with addiction because of the high prevalence of ACE in their background.

Sue learned where her fear of communication came from and came to see how Sara is not like her father. Her father was intrusive and other family members were emotionally neglecting. She has to learn to self-soothe and self-validate. Asked her how Sara is unlike her parents. Seeing Sara with new eyes (perception) is important to reduce her fears about communicating at work and at home.

The counselors put the 4-dimensional process of CCT into slow motion so clients could recognize how a person feels, thinks, makes meaning, perceives situations that could lead to withdrawal or confrontation. Job challenges became opportunities to enlarge upon the work in couple therapy and vice versa, as they are often isomorphic with each other:

Larry shared that he suppresses everything, then his mind starts racing. Writer invited him to practice identifying his feelings and sharing them. Larry said that he could not and noted anxiety rearing up like a knot in his stomach. . . Writer continued to work with him, processing the anxiety and invited him to share his feelings in a practice role play to Lisa. Lisa intervened to rescue Larry and writer intervened to stop Lisa and re-directed back to Larry. Worked further with this until Larry was able to identify that his fear is that he would give the answer wrong and be judged by Writer. Linked to family of origin and childhood whereby everything he did was judged bad or wrong, particularly if he showed feelings he was punished and judged. . .Larry was able to identify anger and the reason behind anger. . .He was also able to identify feeling helpless. . .Writer asked him to put all that together and turn to Lisa and share it. . .Larry was amazed that he did it and it seemed easier than the escalation in his head about how he couldn’t do it.

The above excerpt from the counselor’s notes illustrates how CCT raised awareness in all 4 dimensions of what Larry was experiencing in himself (intrapsychic), his attempts to speak for himself and Lisa’s interference (interpersonal), the influence of ACE (intergenerational) on his fear of speaking about himself and his feelings. Larry experienced the elevation of his self-worth (universal-spiritual) when he was finally able to represent himself in congruent communication. The counselor also had to modify Lisa’s tendency to take over speaking for Larry to make space for him to speak for himself, thus changing a long-standing pattern of Larry’s suppression of himself and his avoidance of communication. With more opportunities to practice representing himself at home, Larry became better able to do the same at work.

Congruent communication

Majority of participants with addiction were avoidant in communication. When under stress, they withdrew and stuffed their thoughts and feelings while struggling internally. They lacked the words to describe their emotions and viewpoints. Avoidance is a dangerous posture of “helplessness, hopelessness, worthlessness and despair” (p. 27). 31 This ineffectual coping style manifested in depression and addiction. Some clients with built-up stress at work due to poor communication vented their frustrations at the partner as an outlet:

Jane claimed this pattern comes out a lot regarding work stress, as she doesn’t assert her feelings around workplace frustration, feels angry and resentful, blows up at Jared when she gets home, feels bad for blowing up, so she goes back to placating and not expressing herself. When asked where in this cycle Jane felt she had some control in making change, she indicated around communication.

Clients learned that no 2 people are the same. They have different vantage points, backgrounds, and unique concerns and are naturally different. This learning allowed them to be more accepting of their differences in viewpoints regarding business decisions:

When an ex-employee filed a complaint with the labour board, Olivia wanted to pay the fine and put it behind them. Oscar indicated he has a hard time “letting go” of situations like this.

Couples learned to express appreciation toward one another, for example, Diana expressed appreciation for Dylan today, how significant it is that he’s been able to abstain from drinking. They turn their complaints into wishes, make requests so communication could lead to action, and ask questions to open a space for the partner to speak:

Kyle and Krystina stated that they have been practicing changing their complaints into requests. Krystina noted that this is difficult for her to do but she is taking the risk. She shared an example: she asked Kyle for help getting dinner on [son’s] first night back as she felt overwhelmed and took a risk to ask Kyle for help and he did help her. They both noted the tone in which the request was made which was not complaining but expressing a need.

Thus, the changes in awareness, communication, and boundaries in the couple therapy sessions became a model for the client to function more effectively at work, as in case of Oscar and Olivia allowing each other the space to do their job and to make decision in consultation with each other:

The couple agreed with the counselor that their [business] roles are more separate and cooperative now. Business decisions are being made together, and Oscar indicated he is feeling confident in his managerial role. He recounted a conflict with an ex-employee where he was able to handle most of the conversation and communicate his side clearly but that he was grateful to have Olivia’s support when he began to “get excited.” . . .Oscar identified that he can be people-pleasing but is getting better at setting limits, especially at work. Overall, Oscar reflected he is taking disappointments in stride, feeling in control, and their business is doing quite well which “takes a lot off my shoulders.” They agreed that “We are making decisions together.”

Congruence means greater integrity with oneself and with others. Toward the end of therapy, Dylan took the following steps:

For the first time, Dylan disclosed to his employers the extent of his problem gambling and drinking. . . feeling freer to pursue leisure and more time with Diana. Though his future with the company is uncertain, Dylan is optimistic about finding a better work-life balance and a solid footing in recovery whether in this job or a new one. . . Diana expressed how proud she is of Dylan for his honesty with his boss. Although being in limbo is scary. Doug reflected that it feels like there is a “huge weight off.” He observed how his mentality has changed, and he is no longer so defensive and avoidant. “He’s a different guy,” observed Dana, “he’s present, I feel him there.”

Work-family balance

As noted earlier, overworking and workaholism are common among those with substance and gambling problems. CCT helped clients become more cognizant of work-family balance in learning about the harm that workaholism had brought to their partners and children. In CCT, clients set better boundaries to maintain a healthy work-family balance, and this could be in refusing to take double shifts, for example, Matt is now refusing to work double shifts to reduce his stress, or sharing the work of running the business more collaboratively with one’s partner. Self-awareness and communication skills about how to delegate, give feedback, and set reasonable priorities lessened the workload and stress.

The motivation for re-balancing work and one’s personal and family life came with a greater sense of self-worth:

Olivia expressed a hope that Oscar will look after himself and we linked it with valuing yourself (universal-spiritual dimension). Oscar stated he would go to the gym with Olivia and set a priority of losing the excess weight. Oscar was able to note a positive change that he now is comfortable going to the doctor where he used to hate it. Acknowledged his increasing self-care. Noted that taking care of his physical needs would contribute further to his emotional health & recovery. Encouraged Oscar to put in place a “transition ritual” (like changing clothes, saying a prayer, etc) at the end of the work day as he mentioned he still tends toward bringing work home and wishes to get better at “letting go” of work stress.

Partners harbored hurt and resentment of being unloved and unimportant with their partner’s prolonged workaholism. With better couple communication, couples were better able to negotiate the work-family balance:

Diana emphasized the need for more balance with their relationship. “He’s given a lot to that job and done very well professionally. He’s good at his job.” (turning to Dylan), “What are you willing to sacrifice?” Writer explored some things they could do to make it easier. Dylan could communicate how long he plans on spending in the office, check-in with each other at certain intervals if he’s working for extended periods. Writer noted the difference it could make if Dylan volunteers the information rather than Diana asking and Dylan feeling scrutinized. The couple was agreeable to these strategies. Diana recognized that it will take time for her not to automatically feel triggered when he enters his office.

Enlisting spousal support

Giving and receiving support from one’s intimate partner was an important part of recovery whereby the couple unit became a natural resource for them rather than seeking support through outside programs. Through CCT, clients clearly identified their goals regarding their addictive behaviors, for example, Jared is taking a harm reduction approach in attempting controlled drinking. He hopes to limit his drinking to social occasions, evenings only, no hard liquor, and limit number of drinks. Further, the couple turned to each other as allies to diffuse work stress and in making major career decisions:

She appeared supportive of her husband and understanding that applying for a new type of job will be stressful for him as well as exciting. Both want to see him try something new that will ultimately be less stressful than running their own trucking company.

The couple learned to confide in each other on work scenarios:

Encouraged the couple to talk about what are the husband’s options re work-related stressors. The wife was asked to practice reflective listening while her husband talked and let him rehearse what he will say to his boss.

Another couple set aside a check-in time with each other daily:

They continue to do their evening check-ins that have become a part of their evening routine. Knowing there is this time to check in has decreased Sara’s anxiety around needing to connect and allowed her to give Sue more space during her transition home.

Greater respect and trust in the couple made it easier for them to confide in each other and seek out each other’s support.

The couple continues to come in relaxed, sharing time equally. The husband appears happier and more expressive. The wife jumps in less when he is speaking, but is open and congruent when discussing her feelings and hopes.

The intersecting changes of increased self-other awareness and congruent communication with improved couple relationship, work functioning and addictive behaviors are summarized in the following counselor’s entry:

Olivia added that Oscar speaks up more now, and that they both appreciate that they don’t argue like they used to. . .He reflected “I was too involved in other stuff” with a mindset of “they’re wrong, I’m right.” Now, he says he tries to listen before responding. About himself, he said he appreciates being more honest, open-minded. “I’m glad I’m off alcohol, I hope I can be proud.” He stated he places higher value now on himself and his family. “If I can’t be there for myself, I can’t be there for my family.” Writer pointed out this powerful statement of building a healthy life from within.

Summary

The self-other awareness and communication skills developed through CCT in the couple context were transferred into handling work relationships. As the couple relationships improved, clients were more willing to reduce tendencies to overwork and prefer time with partner and family. They were also more willing to seek support from their partners as workplace issues arose. With lowering stress levels at work and at home, clients’ need to turn to substances and gambling to regulate emotional distress abates.

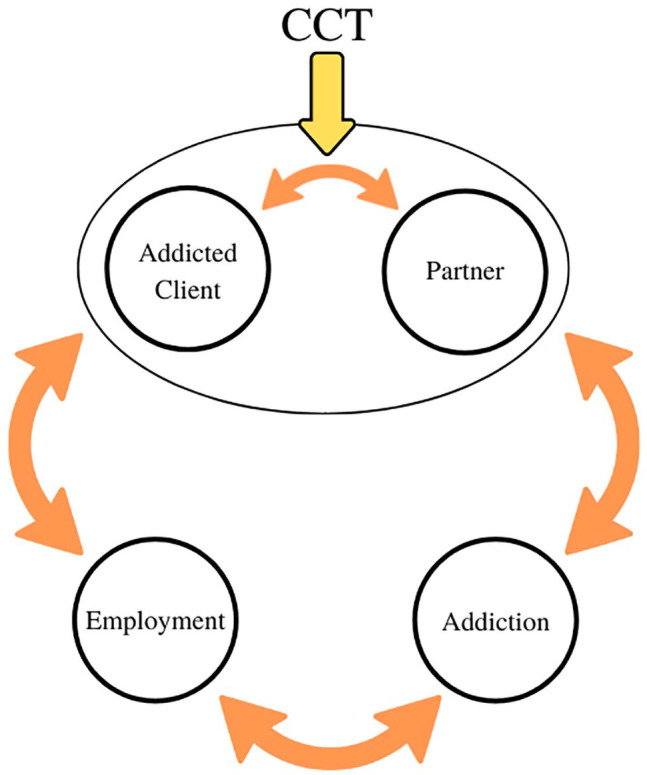

Discussion

Employment problems are prevalent among those struggling with substance use and gambling disorders.1,2 Prevailing programs to help addicted clients with employment usually assume a primary focus on job search and training with inconsistent results.16,35 An in-depth examination of what contributes to the employment problems of individuals with addiction has not been conducted, in particular in relation to their psychological and interpersonal functioning. To the best of our knowledge, qualitative studies to illuminate the interaction of employment issues and couple adjustment with addiction have not been undertaken to date. Neither has couple therapy been considered a viable intervention that could enhance employment functioning in existing literature. The present study contributes to fill these gaps of understanding and intervention, revealing how employment concerns are not separate from couple adjustment and the 2 are intertwined in elevating stress level in the maintenance of addiction. Systemic couple therapy such as CCT can serve to reduce employment stress (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Reciprocal interactions of employment—couple adjustment—addiction.

Work-family interface and addictive behaviors

Several models have been proposed for the relationship between work stress and alcohol use. 36 A direct cause-effect model is deemed to be too simplistic. A more plausible hypothesis is that of a mediator-moderator model that posits examining intervening variables that place the worker at increased risk of alcohol use in the face of work stress, as well as variables that can protect the worker from alcohol use with work stress. 36 Daily work-to-family conflict, defined as work that interferes with fulfilling the responsibilities of family, has been found to significantly predict employee’s alcohol use. 37 However, family support and co-worker support moderated the relationship between daily work-to-family conflict and daily alcohol use. 37 These research findings reinforce the importance of attending to family factors that can function as a moderator to drinking problems such as enlisting spousal support in problem solving, mutual emotional acknowledgment and encouragement as illustrated in this qualitative study.

Stress and couple adjustment in addiction

This study provided a granular description of the 5 types of employment-related stress encountered with addiction and showed their deleterious effects on the partner and the couple relationship. The harms to partners were emotional, relational, financial, and social due to criminal acts and loss of the good will of friends and family. Our findings align with those from a recent population-based problem gambling survey indicating that emotional, relationship, and financial harms were the most common among affected family members represented more by women. 38 Employment problems adding to couple discord increase the psychological load that strains the individual’s adaptive ability. The positive association of increased stress and stressful life events with the development and relapse of alcohol, substance use, and gambling disorders have been reported in numerous studies.39-42 Further, early life stress, child maltreatment, and accumulated adversity alter brain mechanisms that are associated with stress-related risk of addiction. 43 Hence reducing overall stress level at home and at work is conducive to more sustained recovery.

Reciprocal influence of work and family

Our findings highlight the interactive nature of work and family that had largely been ignored and regarded as separate domains in addiction treatment and its employment programs. Lively research on the intersection of family and work stress has been conducted in other disciplines such as organizational psychology since the beginning of the 21st century,28,44 but the addiction field had not paid attention to the work-family relationship. Studies found that work and family influence each other in reciprocal ways that can be positive or negative.45,46 High job stress such as more time at work, inflexible schedules and unsupportive boss and co-workers interfered with family while family stress and conflict posed the greatest disruption at work. 45 Our study found that the impact of employment stress on couple difficulties was more prominent than vice versa.

Greenhaus and Powell 46 proposed a model of work-family enrichment arguing that positive experience in one role can be transferred into the other role through instrumental or affective pathways such as skills and perspectives, improved psychological and physical well-being and social capital. This work-family enrichment model is supported by the findings of the present study showing that resources gained through couple therapy made a positive difference at work both indirectly and directly. Indirectly, the individual’s higher level of well-being and self-esteem lowered stress due to more harmonious and cooperative couple adjustment and less resort to addiction as a way of coping. Significant addiction symptom reduction together with improved couple adjustment, emotion regulation and reduced stress with CCT was found among the main RCT outcomes of the same study. 47 These areas of improvement were related to the increase in working days. 47 Work stress was ameliorated indirectly by the empathy, support, consultation and understanding partners gave to each other. More directly, the addicted individual applied the newly learned skills of congruent communication and awareness of self and other along with increased awareness of family of origin patterns to better respond to stress at work. Such skills involved setting boundaries, regulating one’s emotions, recognizing one’s triggers, making requests and using effective communication. Improvement in couple adjustment and communication were especially germane to family-run businesses. Coping styles and coping skills were the most protective factors to prevent work and family stress from spilling across domains. 45

Intergenerational impact

The work-family interface literature had not given attention to how intergenerational issues influence work, 48 such as learned behaviors and values from family of origin, distorted perceptions, avoidance and poor communication. Cumulating evidence has demonstrated the strong association of ACE and child maltreatment with substance use, disordered gambling and emotion dysregulation.49-51 In the present study, 57% of addicted clients and 52% of partners reported a history of ACEs, hence attention to intergenerational influence on work and family relationships in addiction recovery is especially pertinent. This study revealed that family of origin rules, expectations and communication insinuate their way into work and couple functioning. Raising awareness of dysfunctional intergenerational patterns and interrupting them would be an important component in programs to help individuals with addiction augment their employability and work relations.

Limitations

Several limitations accompany this study. First reliance on counselors’ case notes to answer our research questions is filtered through the counselors’ lens and therefore less trustworthy a source of data compared to analyzing actual counseling session transcripts. However, the counseling sessions were not recorded to protect clients’ privacy in the health system in which the research was conducted so we are left to rely on the secondary option. Second, in the context of the RCT, availability of the counselors’ case notes of the control group that used an individual approach of treatment could have been instructive for comparison.

Conclusion

Results from the thematic analysis of counselors’ clinical notes revealed that addicted clients face a myriad of challenges when unemployed as well as with employment. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first qualitative study to delineate the inter-relationship of employment stress and couple adjustment in the context of alcohol and substance use and gambling. Addiction is both a cause of employment problems and also a result of it.6,14 Work stress and couple stress are more intimately related than previously recognized and can compound the overall level of stress for the individual with detrimental results for addiction. Hence improving couple and family functioning should be incorporated into the design of programs to augment employability and employment of those in recovery.

Convergent findings in a parallel quantitative study drawing from the same RCT support the synchronous effects of work and couple functioning indicating that work status improved with increased couple adjustment, emotion regulation and reduced stress. 47 It further indicated that a systemic approach to treatment such as CCT that targets multiple areas of recovery capital variables is more likely than individually-based treatment to increase employment as measured by working days. 47 The thematic description of this study provides explanation for the correlated changes of couple adjustment, emotion regulation, and reduced stress that occurred with increased working days found in the CCT quantitative study. CCT enhanced skills and awareness in the couple domain that are transferrable to enhance work-related functioning. The domains of work and family are permeable and interactive, and this study has brought the light of the integral nature of work-family connection to inform addiction treatment as exemplified in Congruence Couple Therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the addiction counselors Chelsea Bronevitch, Dianne Hohol, Korie-Lyn Northey, Joleen Smith-Duff and Krista Yaskiw for their valuable contributions to this study. We also thank Dr. Samuel Ofori-dei and Jamie Groenenboom for their assistance with the literature review and comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Bonnie Lee is the developer of Congruence Couple Therapy and has received fees for workshops conducted on this model.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The data reported in this manuscript are part of a larger randomized controlled trial on Congruence Couple Therapy vs Treatment-as-Usual funded by a major grant of the Alberta Gambling Research Institute (Grant No. 43649), and sub-grants from CIHR Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse (CRISM Prairie Node) and the Canadian Depression Research and Intervention Network, Regional Depression Research Hub.

Author Contributions: Dr. BKL conceptualized this study and was the principal investigator and clinical consultant of the Congruence Couple Therapy randomized controlled trial on which this study is based. NKM conducted the thematic analysis with supervision from Dr. BKL. Both authors contributed to writing the article.

ORCID iD: Bonnie K Lee  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6601-3416

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6601-3416

References

- 1. Eddie D, Vilsaint CL, Hoffman LA, Bergman BG, Kelly JF, Hoeppner BB. From working on recovery to working in recovery: employment status among a nationally representative US sample of individuals who have resolved a significant alcohol or other drug problem. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;113:108000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Laudet AB, White W. What are your priorities right now? Identifying service needs across recovery stages to inform service development. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38:51-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siegal HA, Fisher JH, Rapp RC, et al. Enhancing substance abuse treatment with case management its impact on employment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1996;13:93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Laudet AB, Magura S, Vogel HS, Knight EL. Interest in and obstacles to pursuing work among unemployed dually diagnosed individuals. Subst Use Misuse. 2002;37:145-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morgenstern J, McCrady BS, Blanchard KA, McVeigh KH, Riordan A, Irwin TW. Barriers to employability among substance dependent and nonsubstance-affected women on federal welfare: implications for program design. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:239-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sherba RT, Coxe KA, Gersper BE, Linley JV. Employment services and substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;87:70-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Henkel D. Unemployment and substance use: a review of the literature (1990-2010). Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4:4-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Muggleton N, Parpart P, Newall P, Leake D, Gathergood J, Stewart N. The association between gambling and financial, social and health outcomes in big financial data. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:319-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nower L. Pathological gamblers in the workplace: a primer for employers. Employee Assist Q. 2003;18:55-72. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jeffrey L, Browne M, Rawat V, Langham E, Li E, Rockloff M. Til debt do us part: comparing gambling harms between gamblers and their spouses. J Gambl Stud. 2019;35:1015-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Steel Z, Blaszczynski A. The factorial structure of pathological gambling. J Gambl Stud. 1996;12:3-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Riley BJ, Larsen A, Battersby M, Harvey P. Problem gambling among female prisoners: lifetime prevalence, help-seeking behaviour and association with incarceration. Int Gambl Stud. 2017;17:401-411. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Riley BJ, Larsen A, Battersby M, Harvey P. Problem gambling among Australian male prisoners: lifetime prevalence, help-seeking, and association with incarceration and aboriginality. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2018;62:3447-3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Compton WM, Gfroerer J, Conway KP, Finger MS. Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002-2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:350-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harrison J, Krieger MJ, Johnson HA. Review of individual placement and support employment intervention for persons with substance use disorder. Subst Use Misuse. 2020;55:636-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Magura S, Marshall T. The effectiveness of interventions intended to improve employment outcomes for persons with substance use disorder: an updated systematic review. Subst Use Misuse. 2020;55:2230-2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sahker E, Ali SR, Arndt S. Employment recovery capital in the treatment of substance use disorders: six-month follow-up observations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Epstein DH, Preston KL. TGI Monday?: drug-dependent outpatients report lower stress and more happiness at work than elsewhere. Am J Addict. 2012;21:189-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walton MT, Hall MT. The effects of employment interventions on addiction treatment outcomes: a review of the literature. J Soc Work Pract Addict. 2016;16:358-384. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Soeker S, Matimba T, Machingura L, Msimango H, Moswaane B, Tom S. The challenges that employees who abuse substances experience when returning to work after completion of employee assistance programme (EAP). Work. 2016;53:569-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Esche F. Is the problem mine, yours, or ours? The impact of unemployment on couples’ life satisfaction and specific domain satisfaction. Adv Life Course Res. 2020;46:100354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blom N, Verbakel E, Kraaykamp G. Couples’ job insecurity and relationship satisfaction in the Netherlands. J Marriage Fam. 2020;82:875-891. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haid ML, Seiffge-Krenke I. Effects of (un)employment on young couples’ health and life satisfaction. Psychol Health. 2013;28:284-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kraft K. Unemployment and the separation of married couples. Kyklos. 2001;54:67-88. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fellows KJ, Chiu HY, Hill EJ, Hawkins AJ. Work–family conflict and couple relationship quality: a meta-analytic study. J Fam Econ Issues. 2016;37:509-518. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mauno S, Kinnunen U. The effects of job stressors on marital satisfaction in Finnish dual-earner couples. J Organ Behav. 1999;20:879-895. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The crossover of work engagement between working couples: a closer look at the role of empathy. J Manag Psychol. 2009;24:220-236. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Allen TD, Herst DEL, Bruck CS, Sutton M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for future research. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5:278-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manag Rev. 1985;10:76-88. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Neff A, Niessen C, Sonnentag S, Unger D. Expanding crossover research: the crossover of job-related self-efficacy within couples. Hum Relat. 2013;66:803-827. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee BK. Congruence Couple Therapy: Concept & Method Workbook. Open Heart Inc; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee BK, Ofori SM, Brown M, Awosoga A, Shi Y, Greenshaw A. Congruence couple therapy for alcohol use and gambling disorders and comorbidities (part I): outcomes from a randomized controlled trial. Fam Process. 2021, in revision. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 34. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sigurdsson SO, DeFulio A, Long L, Silverman K. Propensity to work among chronically unemployed adult drug users. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:599-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Frone MR. Work stress and alcohol use. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:284-291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang M, Liu S, Zhan Y, Shi J. Daily work–family conflict and alcohol use: testing the cross-level moderation effects of peer drinking norms and social support. J Appl Psychol. 2010;95:377-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Castrén S, Lind K, Hagfors H, Salonen AH. Gambling-related harms for affected others: a Finnish population-based survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:9564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Associations between exposure to stressful life events and alcohol use disorder in a longitudinal birth cohort studied to age 30. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:154-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Buchanan TW, McMullin SD, Baxley C, Weinstock J. Stress and gambling. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2020;31:8-12. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roberts A, Sharman S, Coid J, et al. Gambling and negative life events in a nationally representative sample of UK men. Addict Behav. 2017;75:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Young-Wolff KC, Kendler KS, Prescott CA. Interactive effects of childhood maltreatment and recent stressful life events on alcohol consumption in adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:559-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141:105-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bianchi SM, Milkie MA. Work and family research in the first decade of the 21st century. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72:705-725. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Byron K. A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its antecedents. J Vocat Behav. 2005;67:169-198. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Greenhaus JH, Powell GN. When work and family are allies: a theory of work-family enrichment. Acad Manag Rev. 2006;31:72-92. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee BK, Ofori SM. Changes in work status and recovery capital: secondary analysis of data from a congruence couple therapy randomized controlled trial. Addict Res Theory. 2022, in revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Powell GN, Greenhaus JH, Jaskiewicz P, Combs JG, Balkin DB, Shanine KK. Family science and the work-family interface: an interview with Gary Powell and Jeffrey Greenhaus. Hum Resour Manage Rev. 2018;28:98-102. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB. Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addict Behav. 2002;27:713-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Petry NM, Steinberg KL. Childhood maltreatment in male and female treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19:226-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Poole JC, Kim HS, Dobson KS, Hodgins DC. Adverse childhood experiences and disordered gambling: assessing the mediating role of emotion dysregulation. J Gambl Stud. 2017;33:1187-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]