Abstract

Obturator hernia is a rare variation of abdominal hernias that cause significant morbidity and mortality, especially in the elderly population. Incidence rates vary but account for approximately 0.07%–1.0% of all hernias. Literature on laparoscopic versus laparotomy, as well as types of closure (primary vs mesh) have not been well described in the literature. Obturator hernias, although rare, require a high index of suspicion and care in surgical management as many of these patients will be elderly with a multitude of comorbid conditions. Further research and reporting on technique and type of closures utilized when these rare hernias are encountered by surgeons would benefit the surgical community on practices and management of obturator hernias. Here, we present a case of an elderly female who presented with complaints of obstructive symptoms and abdominal pain secondary to an obturator hernia.

Keywords: Obturator’s hernia, obturator canal, small bowel obstruction, laparotomy, minimally invasive surgery, mesh

Introduction

Obturator hernia is a rare variation of abdominal hernias that cause significant morbidity and mortality, especially in the elderly population. Incidence rates vary but account for approximately 0.07%–1.0% of all hernias.1,2 Given the rarity of such hernias, there is no established standard approach to surgery. Open versus minimally invasive or primary repair versus herniorrhaphy versus hernioplasty are all appropriate options for surgical approach. 2 – 4 Patient’s presentation, surgical findings, and level of contamination are generally used as a guide for surgical planning. Here, we present a case of an elderly female who presented with complaints of obstructive symptoms and abdominal pain secondary to an obturator hernia.

Case report

An 89-year-old female presented with complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for approximately 6 days. Patient complained of pain in her left inguinal region and increasing abdominal distension. Patient’s last bowel movement was 2 days prior to presentation. On examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable, however thin and frail with a body mass index (BMI) of 18. Her left leg was flexed and she was appeared very uncomfortable. The abdomen was distended with voluntary guarding in the lower quadrants. Bowel sounds were hypoactive. There was no palpable mass in the inguinal region or inguinal canal. The patient reportedly underwent Ladd procedure approximately 4 months prior due to malrotation, resulting in a 20-pound weight loss. Patient denies history of chronic constipation or bowel issues prior to this past year.

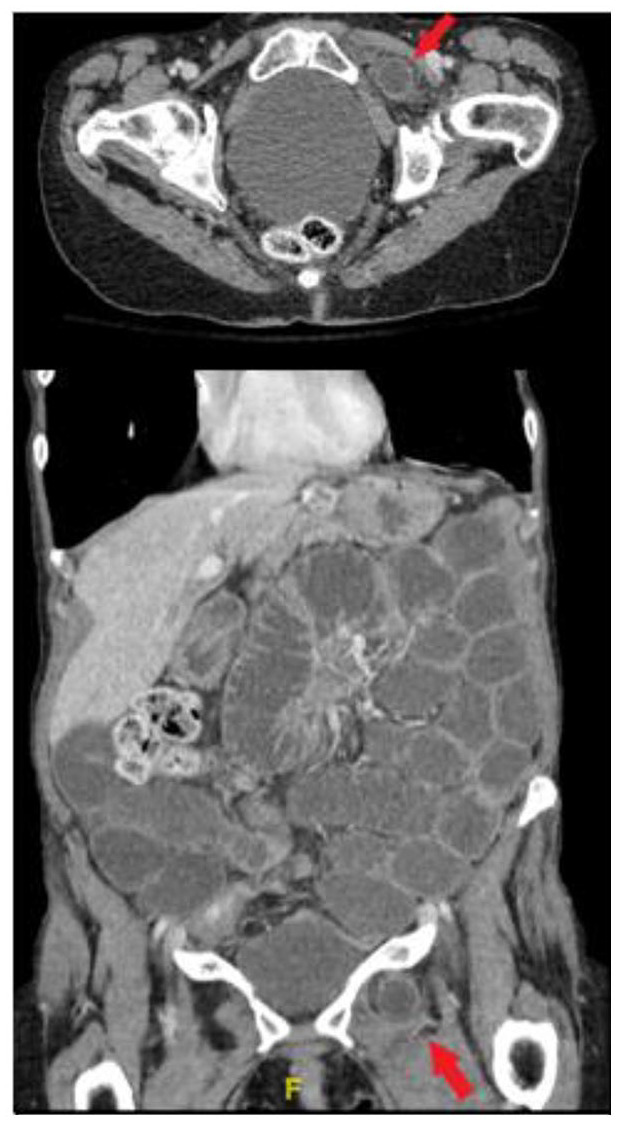

A computed tomography (CT) of her abdomen and pelvis with contrast was obtained which revealed dilated loops of small bowel and evidence of a loop of bowel through the left obturator foramen, significant for an obturator hernia, as shown in the Figure 1. Informed consent was obtained and she was taken to the operating room for surgical exploration.

Figure 1.

Axial and coronal CT cuts showing the left obturator’s hernia (red arrows) causing small bowel obstruction demonstrated by the dilated loops of small bowel.

A vertical midline incision just inferior to the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis was utilized. The bowel was delivered out of the abdomen and the left obturator hernia was identified. The hernia was noted to contain a small loop of ileum 4 cm in length and approximately 15 cm from the ileocecal valve. This was carefully reduced out of the hernia sac. Bowel serosa was noted to be hemorrhagic but viable. The hernia sac was then reduced and a small defect in the obturator space was palpated. The defect was repaired with the use of a woven polypropylene mesh plug which was sutured to the surrounding muscle and abdominal fascia using 2-0 prolene suture. Peritoneal defect was closed with 3-0 Vicryl in a running fashion to cover the mesh plug. A sheet of biologic mesh was then placed over the peritoneum and secured with 2-0 prolene to the underlying pubic rami and periosteum. The small bowel was then inspected from the ligament of Trietz to the terminal ileum and no other pathology was identified. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for postoperative care. Her postoperative course was complicated by fascial dehiscence requiring an additional procedure on postoperative day 3. She had slow return of bowel function and was eventually discharged from the hospital on a regular diet on hospital day 15. At 30-day follow-up, the patient is doing well without recurrence or ongoing pain. Patient is slowly gaining weight back and is without further complications or complaints.

Discussion

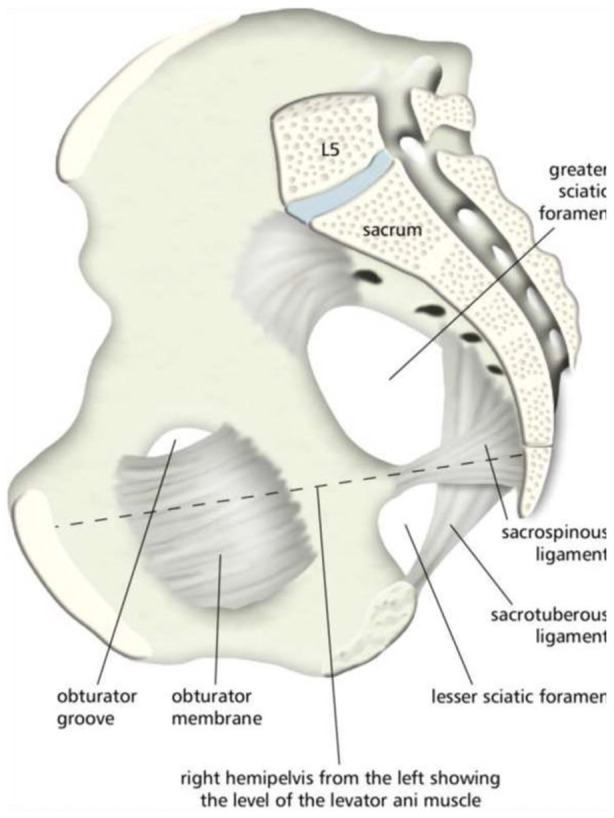

Obturator hernias were first described in the literature in 1742 by Arnaud de Ronsil. These hernias occur though the obturator canal which lies superiorly in the obturator foramen. The canal is formed by a ligamentous band connecting the anterior and posterior portions of the obturator tubercle. The canal is approximately 2–3 cm long and 1 cm wide, allowing passage of the obturator artery, vein, and nerve from the pelvis out to the thigh. It is covered by the obturator membrane which is pierced by these structures. Figure 2, from the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland, shows the obturator canal, labeled as the obturator groove, superior to the obturator foramen which allows the passage of these structures. 5 When an obturator hernia occurs, it will pass through the obturator internus, obturator membrane, and obturator externus. The sac is usually deep to the pectineus muscle and lateral to the adductors. The sigmoid colon overlies the obturator foramen on the left and can prevent hernia formation on this side; as such, obturator hernias are more common on the right. The obturator canal is larger, and more triangular shape in women increases the risk of herniation compared with men.

Figure 2.

“Hemipelvis and ligaments” by Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 1.0.

Obturator hernias occur typically in elderly emaciated females between the ages of 70 and 90 due to loss of pre-peritoneal fat which protects the obturator vessels and nerves in the canal. Increase in abdominal pressure such as ascites, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and chronic coughs are the risk factors for developing an obturator hernia. 2 Presentation can vary but over 80% present with obstructive-like symptoms. About 40%–100% of symptoms are caused by a Richter’s hernia of small bowel. 6 Patients may present with a Howship–Romberg sign or obturator nerve neuropathy due to irritation of the nerve by bowel in the hernia. Flexion of the thigh relieves the pain as seen in the patient who is presented here. 7

Various imaging modalities have been described in diagnosing obturator hernias. These include plain radiographs, ultrasound, barium enema, and CT scans, with CT being the most reliable and relevant. CT scans of the upper thigh and pelvis will show bowel herniating through the obturator foramen and lying between the pectineus and obturator muscles. 8 CT scans with their high sensitivity and specificity have become the gold standard to diagnose obturator hernias. 2 However, it is prudent not to have an over-reliance on imaging. In our patient above, the hernia was misinterpreted as an inguinal hernia on initial radiology evaluation.

Many different surgical approaches have been described from transabdominal, extraperitoneal laparoscopic approaches and open laparotomy. The open laparotomy approach described in literature, usually via a low midline incision, allows for full evaluation of bowel, exposure of the obturator ring, identification of the inguinal and obturator vessels, and bowel resection if necessary. 2 –4,6 This has obvious advantages in emergent cases. Extraperitoneal approaches have been favored in more elective procedures if no bowel strangulation is suspected. This technique has its advantages such as reduced rate of postoperative ileus, adhesion formation, risk of injury to other abdominal viscera, and decreased length of stay. 6 Minimally invasive approach to all types of hernias is becoming more common as surgeons have mastered laparoscopy and robotics surgery. Simple closure of the hernia is found to have a recurrence rate of 10%–22%.3,9,10 Holm et al. 9 performed a literature review looking at 1299 patients and found no recurrences of obturator hernias with a laparoscopic technique with the use of mesh. A variety of other flaps and materials have historically been used for repair, but laparoscopic mesh repair is becoming a better and more common method. Given the rarity of such hernias, there is no established standard approach to surgery. Open surgery and minimally invasive, or primary repair and mesh repair have all been used and described in the literature.

Mortality from obturator hernias has ranged from 8% to 47% in the literature. A retrospective study performed at a single institution from 2001 to 2010 reviewed 21 patients with obturator hernias. Overall mortality was 47.6%. 11 Another retrospective study performed in 1999 demonstrated a mortality rate of 11.1% from their cohort of 36 patients. 12 CT scans were thought to decrease morbidity and mortality due to their high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis. Preoperative diagnosis of obturator hernias allows for perioperative planning with possible avoidance of exploratory laparotomy. Schizas et al. 2 recommend preoperative CT scans as they demonstrated its association with reduced postoperative mortality rates, a finding also demonstrated by Kammori et al. 13 However, Yokoyama et al. 12 found no benefit in mortality with preoperative CT scans. While early operative management is needed for obturator hernias, CT scans remain invaluable for diagnosis and surgical planning. More studies may be necessary to better evaluate CT scans’ efficacy to decrease perioperative mortality.

Conclusion

Literature on laparoscopic versus laparotomy, as well as types of closure (primary vs mesh) have not been well described in the literature. This is partly due to the rarity of these hernias and new techniques of laparoscopic surgery. Obturator hernias, although rare, require a high index of suspicion and care in surgical management as many of these patients will be elderly with a multitude of comorbid conditions. Further research and reporting on technique and type of closures utilized when these rare hernias are encountered by surgeons would benefit the surgical community on practices and management of obturator hernias.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported in whole by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare-affiliated entity. Views expressed in this publication represent those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Adam Delgado  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8457-7103

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8457-7103

References

- 1. Bjork KJ, Mucha P, Cahill DR. Obturator hernia. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1988; 167: 217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schizas D, Apostolou K, Hasemaki N, et al. Obturator hernias: a systematic review of the literature. Hernia 2020; 25(1): 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hunt L, Morrison C, Lengyel J, et al. Laparoscopic management of an obstructed obturator hernia: should laparoscopic assessment be the default option? Hernia 2008; 13(3): 313–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ziegler D, Rhoads J. Obturator hernia needs a laparotomy, not a diagnosis. Am J Surg 1995; 170(1): 67–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland. Hemipelvis and Pelvic Ligaments. HEalth Education Assets Library. University of Utah, 2012, https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=871955&q=obturator&fd=title_t%2Cdescription_t%2Csubject_t%2Ccollection_t&facet_setname_s=ehsl_heal (accessed 12 January 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mantoo S, Mak K, Tan TJ. Obturator hernia: diagnosis and treatment in the modern era. Singapore Med J 2009; 50(9): 866–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hodgins N, Cieplucha K, Conneally P, et al. Obturator hernia: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2013; 4(10): 889–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Losanoff J, Richman B, Jones J. Obturator hernia. J Am Coll Surg 2002; 194(5): 657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Holm MA, Fonnes S, Andresen K, et al. Laparotomy with suture repair is the most common treatment for obturator hernia: a scoping review. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2021; 406(6): 1733–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karasaki T, Nomura Y, Tanaka N. Long-term outcomes after obturator hernia repair: retrospective analysis of 80 operations at a single institution. Hernia 2013; 18(3): 393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chan KV, Chan CK, Yau KW, et al. Surgical morbidity and mortality in obturator hernia: a 10-year retrospective risk factor evaluation. Hernia 2013; 18(3): 387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yokoyama Y, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M, et al. Thirty-six cases of obturator hernia: does computed tomography contribute to postoperative outcome. World J Surg 1999; 23(2): 214–216; discussion 217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kammori M, Mafune K, Hirashima T, et al. Forty-three cases of obturator hernia. Am J Surg 2004; 187(4): 549–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]