Abstract

Objective

To compare the efficacy of different statin treatments by intensity on levels of non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in people with diabetes.

Design

Systematic review and network meta-analysis.

Data sources

Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Embase from inception to 1 December 2021.

Review methods

Randomised controlled trials comparing different types and intensities of statins, including placebo, in adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus were included. The primary outcome was changes in levels of non-HDL-C, calculated from measures of total cholesterol and HDL-C. Secondary outcomes were changes in levels of low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and total cholesterol, three point major cardiovascular events (non-fatal stroke, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and death related to cardiovascular disease), and discontinuations because of adverse events. A bayesian network meta-analysis of statin intensity (low, moderate, or high) with random effects evaluated the treatment effect on non-HDL-C by mean differences and 95% credible intervals. Subgroup analysis of patients at greater risk of major cardiovascular events was compared with patients at low or moderate risk. The confidence in network meta-analysis (CINeMA) framework was applied to determine the certainty of evidence.

Results

In 42 randomised controlled trials involving 20 193 adults, 11 698 were included in the meta-analysis. Compared with placebo, the greatest reductions in levels of non-HDL-C were seen with rosuvastatin at high (−2.31 mmol/L, 95% credible interval −3.39 to −1.21) and moderate (−2.27, −3.00 to −1.49) intensities, and simvastatin (−2.26, −2.99 to −1.51) and atorvastatin (−2.20, −2.69 to −1.70) at high intensity. Atorvastatin and simvastatin at any intensity and pravastatin at low intensity were also effective in reducing levels of non-HDL-C. In 4670 patients at greater risk of a major cardiovascular events, atorvastatin at high intensity showed the largest reduction in levels of non-HDL-C (−1.98, −4.16 to 0.26, surface under the cumulative ranking curve 64%). Simvastatin (−1.93, −2.63 to −1.21) and rosuvastatin (−1.76, −2.37 to −1.15) at high intensity were the most effective treatment options for reducing LDL-C. Significant reductions in non-fatal myocardial infarction were found for atorvastatin at moderate intensity compared with placebo (relative risk=0.57, confidence interval 0.43 to 0.76, n=4 studies). No significant differences were found for discontinuations, non-fatal stroke, and cardiovascular deaths.

Conclusions

This network meta-analysis indicated that rosuvastatin, at moderate and high intensity doses, and simvastatin and atorvastatin, at high intensity doses, were most effective at moderately reducing levels of non-HDL-C in patients with diabetes. Given the potential improvement in accuracy in predicting cardiovascular disease when reduction in levels of non-HDL-C is used as the primary target, these findings provide guidance on which statin types and intensities are most effective by reducing non-HDL-C in patients with diabetes.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42021258819.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is expected to affect 380 million people worldwide by 2025,1 2 and patients with type 2 diabetes are at increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, the leading cause of death globally, with an estimated 17.9 million deaths each year.3 4 Lipid modifying treatments, such as statins, are considered the basis of primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease by lowering levels of low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) in the blood.5 Statins have been found to be the most effective agents in reducing the risk of coronary heart disease in patients with diabetes, reducing the relative risk by a third.6 7

The National Cholesterol Education Program in the United States recommends that LDL-C values should be used to estimate the risk of cardiovascular disease related to lipoproteins in individuals.8 Non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), however, might be more strongly associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients receiving statins,9 and could be a better tool than LDL-C for assessing the risk of cardiovascular disease and the effects of treatment.10 The rationale for this recommendation is that non-HDL-C includes all potentially atherogenic cholesterol present in lipoprotein particles, including LDL, lipoprotein (a), intermediate density lipoprotein, and very low density lipoprotein remnants.

Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for adults with diabetes were updated in April 2021. NICE now recommends that non-HDL-C should replace LDL-C as the primary target for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease with lipid lowering treatment.11 In contrast, other international guidelines do not have a non-HDL-C target. The European Society of Cardiology uses LDL-C as their treatment goal.12 Similarly, the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and National Lipid Association target reductions in LDL-C based on patient risk.13

Despite the potential of non-HDL-C as a predictor of developing cardiovascular diseases, no study has assessed the comparative effectiveness of different lipid lowering treatments on levels of non-HDL-C in people with diabetes. Therefore, we carried out a systematic review and network meta-analysis to estimate the comparative effectiveness of seven statins on levels of non-HDL-C in patients with diabetes.

Methods

We undertook the systematic review and network meta-analysis according to a review protocol (PROSPERO CRD42021258819), and the results were reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension statement for network meta-analysis (PRISMA extension checklist, appendix 1).14

Data sources and search strategies

Searches were performed from inception to 1 December 2021 in Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Embase. Screening was done by two independent blinded reviewers (AH, DT) with Covidence software, and disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (MP). Appendix 2 shows the full search strategy. Reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were screened for more studies. Trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, ISCTRN (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number), WHO ICTRP (World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) portal, and OpenTrials.net) were also searched for unpublished or ongoing trials. Drug approval packages at the Food and Drug Administration and European Product Assessment Reports were also scanned for unpublished studies or relevant outcome data. We excluded studies not reported in English.

Eligibility criteria

Studies of patients aged ≥18 years with a diagnosis of type 1 or 2 diabetes were eligible. We included patients treated for primary (that is, no diagnosis of cardiovascular disease) or secondary (that is, history of a cardiovascular disease according to the three point major adverse cardiovascular events classification) prevention of cardiovascular disease. The seven globally prescribed statins were atorvastatin (Lipitor), fluvastatin (Lescol), lovastatin (Altoprev), pitavastatin (Livalo, Zypitamag), pravastatin (Pravachol), rosuvastatin (Crestor, Ezallor), and simvastatin (Zocor) at any dose. The comparator was placebo or any of the seven statins. The primary outcome was a reduction in levels of non-HDL-C, but we also included studies reporting both total cholesterol and HDL-C, allowing us to calculate non-HDL-C levels. Secondary outcomes were reductions in levels of LDL-C and total cholesterol, classical three point major cardiovascular events (defined as non-fatal stroke, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and death related to cardiovascular disease),15 and discontinuations because of adverse event. Only randomised controlled trials were included to limit potential bias.

Data extraction

We extracted data with a standardised form that was previously tested in a pilot study. Data included study characteristics (country, placebo controlled, length of follow-up, and number of patients and outcomes reported) and patient characteristics (mean or median age in years, percentage of men, ethnicity according to the definition of the Office for National Statistics for ethnic group, national identity and region,16 baseline body mass index, diabetes type (1 or 2), duration of diabetes, comorbidity, concomitant drug use (other lipid lowering treatments), and risk of patients according to major cardiovascular events). Data on interventions included the statin agent, dose in milligrams, and intensity based on guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association,17 European Society of Cardiology,18 and NICE.19 All data extractions were completed by two reviewers (AH, DT) and checked by another reviewer (MP).

Categorisation of statin intensity

Based on the recommendations of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, European Society of Cardiology, and NICE for assessing the risk of cardiovascular disease and the reduction in risk, including lipid modification, statins were grouped into three intensity categories according to the percentage reduction in levels of LDL-C: 20-30% reduction is low intensity; 31-39% reduction is medium intensity; and ≥40% reduction is high intensity.20 Table 1 shows the classification of the seven statins used in our analysis following the three dose intensity groups (low, moderate, and high) for the expected reduction in LDL-C. If the dose of statin was positioned between the range of two intensity groups, we chose the nearest group to ensure an intensity was assigned.

Table 1.

Statin dosing and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, European Society of Cardiology, and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence classification of intensity according to percentage reduction in low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)

| Statin | Total daily dose, mg | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low intensity (LDL-C reduced by 20-30%) | Moderate intensity (LDL-C reduced by 31-39%) | High intensity (LDL-C reduced by ≥40%) | |

| Atorvastatin | NA | 10-20 | 40-80 |

| Fluvastatin | 20-40 | 80 | NA |

| Lovastatin | 20 | 40-80 | NA |

| Pitavastatin | NA | 1-4 | NA |

| Pravastatin | 10-20 | 40-80 | NA |

| Rosuvastatin | NA | 5-10 | 20-40 |

| Simvastatin | 10 | 20-40 | 80 |

NA=no classification available from any guideline.

Quality assessment of evidence

The quality of the individual studies was assessed independently by two reviewers with the Cochrane risk of bias tool 2.0 for randomised controlled trials. The overall risk of bias was classified as: low (score=1), when a study was judged to be at low risk of bias for all domains with some concerns showing; some concerns (score=2), when the study was judged to raise more domains with at least some concerns or high risk of bias in one domain; or high (score=3), when the study was judged to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain or to have some concerns for multiple domains in a way that substantially lowered confidence in the result, or both.21 We also applied the CINeMA (confidence in network meta-analysis) framework22 23 to assess the certainty of evidence covering six key domains: within study bias, reporting bias, indirectness, imprecision, heterogeneity, and incoherence.

Data synthesis

The primary outcome of changes in levels of non-HDL-C was calculated as the net difference between levels of total cholesterol and HDL-C. The means and standard deviations of total cholesterol and HDL-C were converted from milligrams per decilitre (mg/dL) to millimoles per litre (mmol/L), the international standard measure for levels of cholesterol. Variance for these calculated values were determined with previously developed procedures.24

Net changes in levels of non-HDL-C were calculated as the difference (statin minus placebo or statin comparator) in these mean values in a network meta-analysis setting, which allowed for the simultaneous evaluation of the different statin intensities.25 To ensure transitivity within the network, we categorised all statin agents and intensity groups, and placebo, into nodes and compared the distribution of clinical (total cholesterol, HDL-C) and methodological (age, sex, and body mass index) variables.26 We used a bayesian random effects network meta-analysis model with a normal likelihood. To account for the correlations induced by multigroup studies, we used multivariate distributions. We considered the I2 statistic and the (heterogeneity) variance in the distribution of the random effect (τ2) to measure the extent of the influence of variability across and within studies on treatment effects. I2 statistic and the 95% confidence interval was interpreted as 0-29%, 30-59%, 60-89%, and >89%, indicating low, moderate, substantial, and high heterogeneity, respectively. To rank the treatments by efficacy, we used the surface under the cumulative ranking curve.27 We evaluated consistency (that is, agreement between direct and indirect evidence) by considering direct and indirect evidence separately with node splitting.28 29

We fitted all models with the MBNMAdose (version 0.3.0) package30 in R version 4.0.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Specifically, we used uninformative prior distributions for the treatment effects and a minimally informative prior distribution for the common standard deviation parameter. Model convergence was ensured by visual inspection of three Markov chain Monte Carlo chains after considering the Brooks-Gelman-Rubin diagnostic. Network graphs scaled by the number of studies and patients by each treatment node were presented graphically. The GeMTC package in R was used to produce some figures and to check the results.31 32 The secondary outcomes, changes in levels of LDL-C and total cholesterol, were analysed in the same way as non-HDL-C. We found few reports for the outcome, discontinuations because of adverse events, so we used the Peto odds ratio method, which is proven to be more suitable for meta-analysing rare events.33 The three point major cardiovascular event outcomes were analysed with DerSimonian and Laird pairwise meta-analysis with the relative risk.34

We performed a subgroup network meta-analysis for the non-HDL-C outcome that focused on high risk patients compared with patients at low to medium risk.35 With the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and baseline data from the individual trial reports, patient risk was categorised as: high, for those with a history of major cardiovascular event outcomes (that is, non-fatal stroke, non-fatal myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, or cardiovascular disease)36; and low to medium, for those who had no previous or current major cardiovascular events at baseline.

A sensitivity analysis with the dose specific network model was conducted to examine the robustness of the findings from the analysis involving categorisation by intensity. A network funnel plot was used to visually scrutinise the criterion of symmetry and penitential presence for small study effect bias.37

Patient and public involvement

In designing this study, we held a patient and public involvement focus group with 24 adults who had diabetes and were taking statins for prevention of cardiovascular disease, to help inform on the interpretation of our findings. These review results will be disseminated to the relevant patient communities.

Results

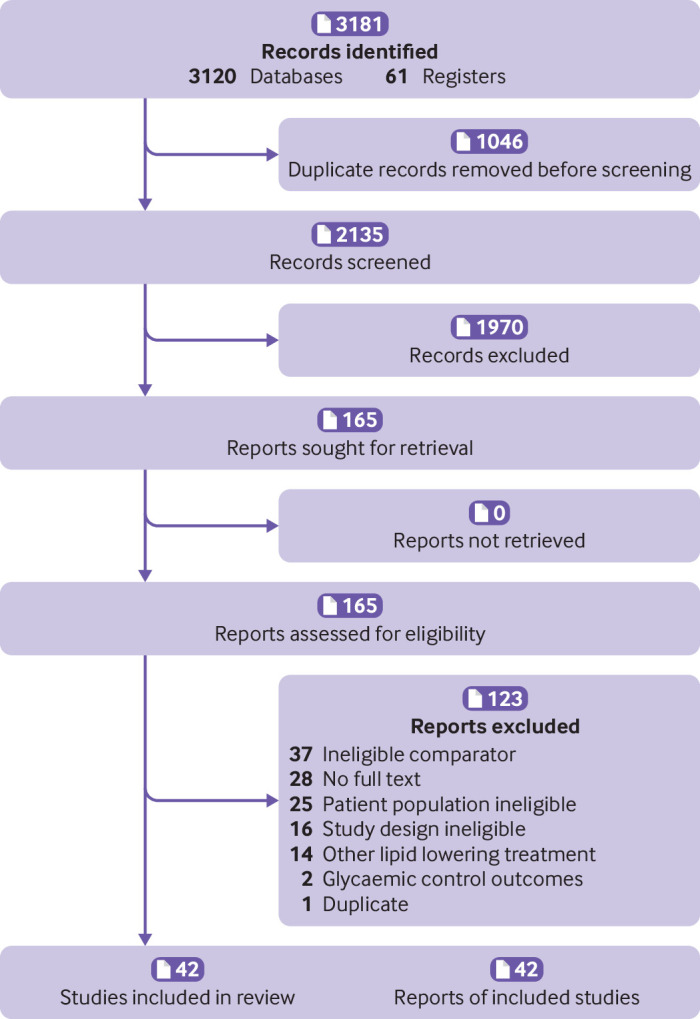

The search retrieved 3181 references. After screening the titles and abstracts of 2135 references, 1970 were excluded, and the full text of 165 reports were screened. Forty two randomised controlled trials, involving 20 193 participants, met our inclusion criteria (fig 1). Appendix 3 lists the included studies.

Fig 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart

Characteristic of included studies

Appendix 4 shows the characteristics of the included studies. Fourteen (33%) of the studies were carried out in the European Union, six (14%) in the US, and four (10%) in the UK.6 38 39 40 The studies involved a median of 145 (range 52-390, interquartile range 338) patients with a median age of 60 years (58-62, 4). Eighteen (43%) studies involved 55% or more men, 11 (26%) involved 55% or more women, and 11 (26%) had a mixture of both sexes. Patients were mostly overweight, with a median body mass index at baseline of 29 (26-31, 5). Seventeen (40%) of the studies included Asian populations (South Korean (n=6),41 42 43 44 45 46 Japanese (n=3),47 48 49 Taiwanese (n=3),50 51 52 Arabic (n=2),53 54 Chinese (n=1),55 Indian (n=1),56 and Thai (n=1) 57), 12 (29%) included white ethnic groups (western or European),6 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 and one (2%) study included patients of mixed ethnicity.69 In 12 of the studies (29%), ethnicity was not reported.38 40 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79

In 35 (83%) studies, patients had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, in five (12%), patients had a diagnosis of type 1 or 2 diabetes,55 70 71 79 80 and in two (5%) studies, patients had a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes only.63 74 Of the 22 (49%) studies that reported the average length of the diagnosis of diabetes, the median was 8 years (range 4-11, interquartile range 7). Most studies (n=32, 76%) involved the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease but nine (21%) studies targeted primary prevention; in one (2%) study, the target was unclear.76 Common comorbidities included stable hypercholesterolaemia (n=12), cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension (n=6), coronary artery disease (n=3), coronary heart disease or peripheral vascular disease (n=3), acute myocardial infarction (n=3), or stable angina (n=2)), metabolic syndrome (n=1), and retinopathy (n=1). Eleven studies reported diabetes status only. In six of the studies, patients were taking other (concomitant) lipid lowering treatment at enrolment; in the remaining 36 studies, most had a washout phase before recruitment or did not specify use of lipid lowering treatment. Eighteen (43%) of the studies involved mostly patients at low risk, 12 (29%) involved patients at moderate risk, and 12 (29%) involved patients at high risk with a current diagnosis of a cardiovascular disease or a previous history of major cardiovascular events. Twenty four (57%) of the studies were placebo controlled and 18 studies (43%) involved an active statin treatment as the comparator. The median length of the intervention period in the studies was 12 weeks (range 8-24).

Assessment of risk of bias

The quality of the studies varied (appendix 5). Five (12%) studies had a high risk of bias for the randomisation process, six (14%) had a high risk for deviations from the intended intervention, five (12%) had a high risk for missing outcome data, and 11 (26%) had a high risk for the measurement of the outcome domain. Selection reporting bias was found in seven (17%) of the studies. Overall, 19 studies (48%) had a low risk of bias (overall bias score of 1) and two of the studies (52%) had a score above 1, indicating some concerns or high risk of bias.

Network meta-analysis

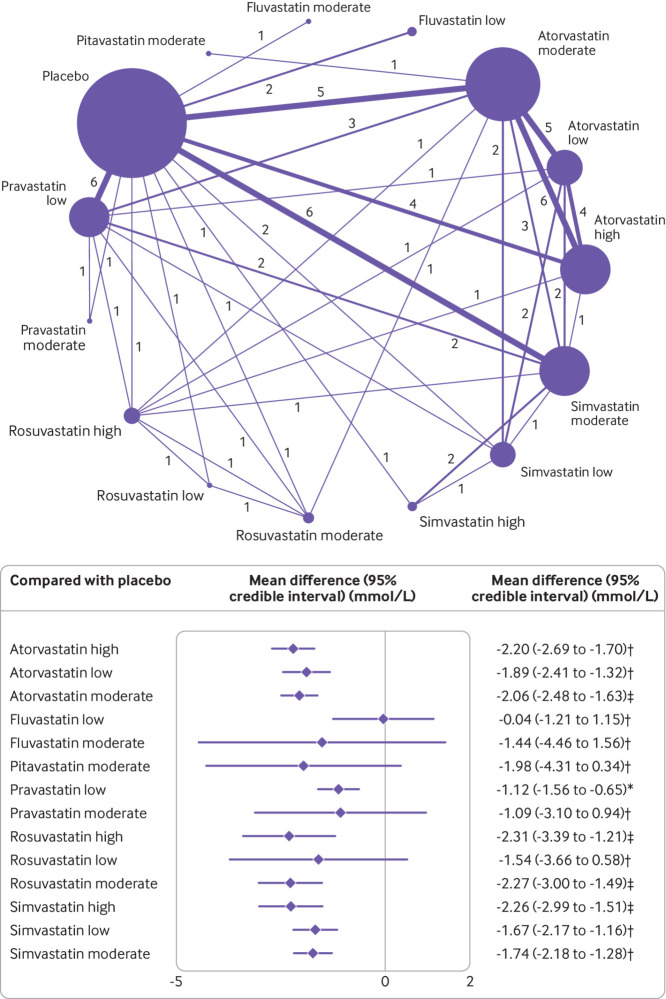

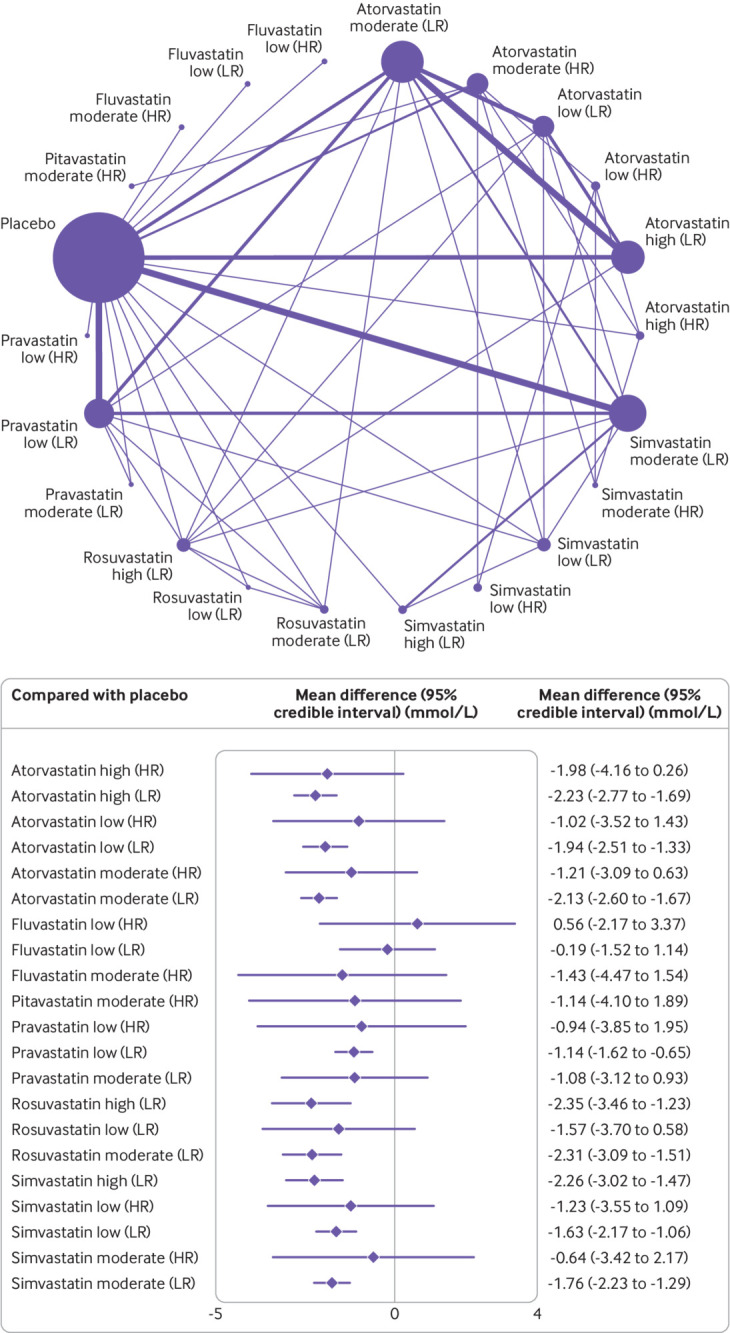

Figure 2 shows the network of eligible comparisons for the primary outcome, changes in levels of non-HDL-C, involving 36 of the trials with amenable data for including in the meta-analysis. The network of evidence included 15 interventions, 11 698 patients, 24 two arm studies, and 12 multi-arm studies. Twenty one studies involved atorvastatin (n=15 moderate intensity,6 42 46 49 50 51 52 53 58 59 67 71 72 73 75 n=10 high intensity,40 42 46 50 51 56 59 60 66 72 and n=7 low intensity46 50 51 57 58 72 76), three studies involved fluvastatin (n=2 low intensity47 68 and n=1 moderate intensity77), one study involved pitavastatin at moderate intensity,52 eight studies involved pravastatin (n=8 low intensity41 44 49 58 63 70 73 79 and n=1 moderate intensity41), four studies involved rosuvastatin (n=3 high intensity,45 56 58 n=2 moderate intensity,45 49 and n=1 low intensity45), and 14 studies involved simvastatin (n=10 moderate intensity,43 44 50 53 54 58 65 69 74 76 n=5 low intensity,43 57 71 73 76 and n=2 high intensity43 65). Appendix 6 shows the model fit statistics and the profile plots of treatment response by dose for the convergence model.

Fig 2.

Network of available comparisons between statin intensities for non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and forest plot of network effect sizes of statin intensities compared with placebo. Size of node is proportional to number of trial participants, and thickness of line connecting nodes is proportional to number of trial participants randomised in trials directly comparing the two treatments. Numbers represent the number of trials contributing to each treatment comparison. Certainty of the evidence, according to the confidence in network meta-analysis (CINeMA) framework, is included in the forest plot and classified as *low, †moderate, and ‡high confidence of evidence. Appendix 11 shows the full CINeMA assessments

Inconsistency analysis

We found evidence of statistical inconsistency through node splitting analysis owing to one comparison of atorvastatin at moderate intensity compared with pravastatin at low intensity (P=0.071); this inconsistency was because one study had a high risk of bias owing to a substantial difference in total cholesterol and HDL-C recordings at baseline73 for the measurement of outcome in the pravastatin treatment group (appendix 7). Another inconsistency was found for pravastatin at low intensity compared with simvastatin at moderate intensity (P=0.031). This inconsistency was because one study44 showed a moderate risk of bias owing to uncertainty with the randomisation process used and the high number of unexplained discontinuations. Because consistency (transitivity) is a central assumption of a network meta-analysis, we removed both trials, leaving 34 randomised controlled trials for the network on non-HDL-C.

Performance on non-HDL-C by statin intensity

Figure 2 shows the network meta-analysis results for the primary outcome of all eligible trials after the inconsistency analysis. Rosuvastatin at high (−2.31, 95% credible interval −3.39 to −1.21 mmol/L) and moderate (−2.27, −3.00 to −1.49) intensities, and simvastatin (−2.26, −2.99 to −1.51) and atorvastatin (−2.20, −2.69 to −1.70) at high intensity were the most effective in reducing concentrations of non-HDL-C compared with placebo. Atorvastatin and simvastatin at all intensities and pravastatin at low intensity also significantly reduced levels of non-HDL-C. Although the other statin agents (fluvastatin at low and moderate intensities, pitavastatin at moderate intensity, pravastatin at moderate intensity, and rosuvastatin at low intensity) effectively reduced levels of non-HDL-C compared with placebo, the relative effects were not significant. Heterogeneity was low in the network meta-analysis, with I2=0% (95% confidence interval 0 to 38%) (appendix 8).

The surface under the cumulative ranking curve score provides an overall ranking of each treatment. In reducing levels of non-HDL-C, rosuvastatin at moderate intensity was ranked as the best statin treatment (surface under the cumulative ranking curve 77.5%), the second best treatment was rosuvastatin at high intensity (76.8%), the third best was simvastatin at high intensity (76.7%), followed by atorvastatin at high intensity (76.3%). The treatment with the lowest surface under the cumulative ranking curve score (excluding placebo) was fluvastatin at low intensity (8.5%) (appendix 10).

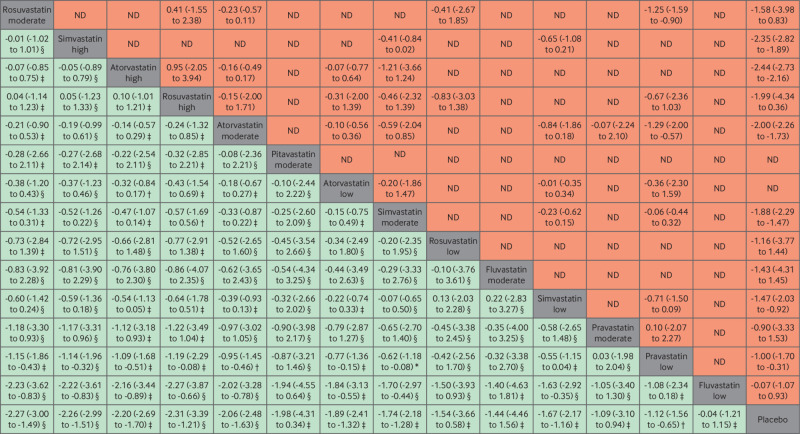

Figure 3 is a league table of the results of the network meta-analysis comparing the effects of the different statin intensities. Almost all statins were effective compared with fluvastatin and pravastatin at low intensity. Rosuvastatin at high intensity seemed to be the best performing statin in direct comparisons with other statin intensities, but the difference in effect sizes were not significant and showed a small benefit compared with other top performers (that is, rosuvastatin at moderate intensity, simvastatin at high intensity, and atorvastatin at high intensity). To ensure the certainty of evidence, we incorporated the CINeMA judgments into figure 2 and figure 3. The quality of the evidence according to CINeMA was mostly moderate or high overall (appendix 11), and we found no evidence of funnel plot asymmetry (appendix 12). Results of the sensitivity analyses of the network meta-analysis by specific statin dose were similar to the main statin intensity model, with atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin significantly reducing levels of non-HDL-C (except for rosuvastatin 25 mg) (appendix 13).

Fig 3.

League table of direct comparisons for statin intensities with effect estimates as mean differences (mmol/L). Statin intensities are reported in order of most effective treatment based on surface under the cumulative ranking curve score compared with placebo. Data are standardised mean difference (95% credible interval) in the column defining treatment compared with the row defining treatment. Green=network meta-analysis estimates (105 comparisons); orange=direct pairwise meta-analysis estimates. Appendix 6 gives the numbers of patient and studies. ND=no direct evidence available. The certainty of the evidence, according to the confidence in network meta-analysis (CINeMA) framework, was classified as *very low, †low, ‡moderate, and §high confidence of evidence

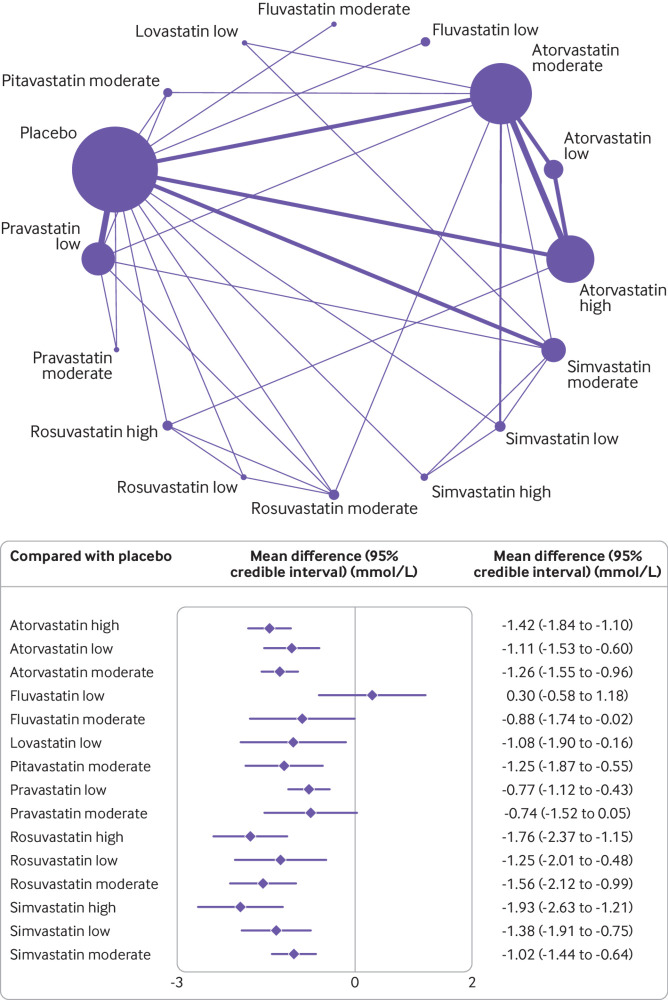

Secondary outcomes

For the secondary outcome, changes in levels of LDL-C, reported in 29 studies (18 two arm, nine three arm, and two four arm), simvastatin (−1.93, 95% credible interval −2.63 to −1.21 mmol/L, surface under the cumulative ranking curve 93%) and rosuvastatin (−1.76, −2.37 to −1.15, 89%) at high intensity doses were the most effective treatment options for reducing levels of LDL-C (fig 4). Heterogeneity was low in this network meta-analysis (I2=5%) and no inconsistency was found (appendix 7). For total cholesterol, reported in 36 studies (23 two arm, eight three arm, four four arm, and one five arm), atorvastatin (−2.21, −2.62 to −1.74), rosuvastatin (−2.18, −3.19 to −1.20), and simvastatin (−2.20, −2.96 to −1.42) at high intensity doses were the most effective treatment options for reducing levels of total cholesterol. Of the 12 studies that reported discontinuations of treatment because of an adverse event, only four statin interventions (pravastatin low, atorvastatin moderate, lovastatin low, and simvastatin moderate intensity) were possible for meta-analyses. We found no significant associations in these analysis, although high uncertainty around the estimates was found, as expected. Appendix 9 shows the raw data for discontinuations because of adverse events. Only five studies6 39 55 59 64 reported at least one of the three point major cardiovascular event outcomes, for atorvastatin moderate and high intensity treatment groups only. We found a significant reduction in non-fatal myocardial infarction for atorvastatin at moderate intensity compared with placebo (relative risk=0.57, 95% confidence interval 0.43 to 0.76, n=4 studies). We found no significant results for non-fatal stroke or death related to cardiovascular disease. Appendix 9 shows the results for the secondary outcomes.

Fig 4.

Network of available comparisons between statin intensities for low density lipoprotein cholesterol, and forest plot of network effect sizes of the statin intensities compared with placebo. Size of node is proportional to number of trial participants, and thickness of line connecting nodes is proportional to number of trial participants randomised in trials directly comparing the two treatments

Subgroup analysis of patient risk for non-HDL-C

Figure 5 shows the subgroup network meta-analysis of 4670 patients with a high risk (10 studies) and 7028 patients with a low-to-medium risk (26 studies) of a major cardiovascular event. The results showed that all statin agents and intensities, except fluvastatin, pravastatin, and rosuvastatin at low intensity, significantly reduced levels of non-HDL-C in patients with a low-to-medium risk of a major cardiovascular event. Atorvastatin at high intensity was the best (not significant, −1.98, 95% credible interval −4.16 to 0.26 mmol/L, surface under the cumulative ranking curve 64%) performer in patients at high risk, and fluvastatin at low intensity (0.56, −2.17 to 3.37, 12%) was the worst. Two studies50 79 with a high risk of bias score were removed from the network, but the results did not change (appendix 14).

Fig 5.

Network of available comparisons between statin intensities for non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol adjusted for patient risk, with forest plot of network effect sizes compared with placebo. Size of node is proportional to number of trial participants, and thickness of line connecting nodes is proportional to number of trial participants randomised in trials directly comparing the two treatments. Patient risk is classified as high (HR) and low to moderate (LR)

Discussion

Principal findings

This network meta-analysis compared the effectiveness of different statin agents at different intensities in adults with diabetes, with a reduction in levels of non-HDL-C as the primary lipid target. The findings derived from a population of 20 193 participants from randomised clinical trials showed that rosuvastatin, given at moderate and high intensity doses, and simvastatin and atorvastatin at high intensity doses, were the best performing statins at lowering levels of non-HDL-C compared with placebo over an average treatment period of 12 weeks. The network model, adjusting for patient risk, showed that of the 4670 adults (40% of the total number of adults) at high risk of major cardiovascular event outcomes (secondary prevention), atorvastatin at high intensity doses was the most effective. Rosuvastatin, at moderate and high intensity doses, and atorvastatin and simvastatin at high intensity doses, were the most effective statin treatment option in the population of 7028 adults at low to medium risk of major cardiovascular events and possible primary prevention.

Comparisons with similar research

No previous meta-analysis has assessed the efficacy of statin intensity based on levels of non-HDL-C. But our findings are similar to a recent network meta-analysis3 that assessed the primary efficacy endpoint of the same seven statins based on management of levels of LDL-C, HDL-C, and total cholesterol in patients with dyslipidaemia, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes. This meta-analysis concluded that rosuvastatin was the most effect in reducing levels of LDL-C (−72.28 mg/dL, equivalent to −1.87 mmol/L), similar to our estimate of −1.76 mmol/L for rosuvastatin at a high intensity dose. However, the authors highlight that their overall findings should be interpreted with caution because of the large variations in follow-up trial periods, ranging from 14 weeks to 5 years; the intensity and doses of statins involved were not clearly unified; non-HDL-C was not used as an outcome; and several inconsistencies between direct and indirect evidence were identified, which could cause bias in the network findings.

Current evidence suggests that some statins cause more adverse events, and high doses might be more harmful to patients. For instance, a large meta-analysis of 246 955 patients assessing the tolerability and harms of individual statins81 found that, compared with other statins, higher doses of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin were associated with a higher risk of discontinuation, and higher doses of atorvastatin, fluvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin were associated with a greater risk of increases in levels of transaminase. Our meta-analysis on discontinuations because of adverse events involved fewer studies and patients, and few events were reported; some studies even reported no events in both treatment arms. Meta-analysing rare events is problematic in this setting and can give spurious findings.82 83 84 Therefore, the results on discontinuations need to be interpreted with caution. Discontinuations because of adverse events and other harm outcomes should be reported in a CONSORT (CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flow diagram and in the study results.85 The primary reports for drug treatment and device trials for chronic heart failure,86 and more specifically for statins,87 often do not provide these data, however. Practising cardiologists need these data to help support clinical judgments when balancing the benefit and harms of different statins.

Implications for policy and practice

The use of lipid or apolipoprotein parameters other than LDL-C as targets for treatment with statins continues to be strongly debated. The clinical applicability of non-HDL-C and LDL-C are identical, however, with the garnered evidence suggesting that non-HDL-C might be superior to LDL-C as a marker of cardiovascular risk,9 88 89 90 and therefore non-HDL-C levels are likely to be a more appropriate target than LDL-C levels for treatment with statins in the future.9 With non-HDL-C as a potential key lipid target, NICE has now recommended that physicians use non-HDL-C as their primary target. Specifically, NICE has set a target of reducing levels of non-HDL-C by >40% from baseline when high intensity statins are used. If the baseline value is not available, however, the Joint British Societies consensus recommends a target level of <2.5 mmol/L for non-HDL-C (equivalent to LDL-C <1.8 mmol/L).91 Further evidence from observational primary care data suggests that at the time of diagnosis of diabetes, the mean concentration of non-HDL-C is 4 mmol/L.92 Many of the patients in their study were taking statins and they would be expected to reach the target of <2.5 mmol/L over time.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Our review assessed the efficacy of the most prescribed statin treatments at different intensities in reducing levels of non-HDL-C in patients with diabetes. Our analysis used robust methods, including bayesian meta-analysis and rigorous quality assessment by CINeMA.

Our study had several limitations. Classification of patient risk was not confirmed at the individual participant level and hence cannot be considered exact. Therefore, we made assumptions based on the study inclusion and exclusion criteria and baseline characteristics to determine an appropriate risk category according to definitions of major cardiovascular events. Also, a flexible method for estimating the effective sample size in an indirect comparison meta-analysis and network meta-analysis93 suggests that some of the pairwise comparisons in the high risk group were underpowered, meaning the results of the subgroup analysis should be interpreted with caution. Our sensitivity analysis, however, removing the studies with a high risk of bias, showed no major differences from the main results.

Only two studies63 74 assessed people with type 1 diabetes, thus limiting our results to mostly patients with type 2 diabetes. The primary focus of our review and of the included studies was on surrogate outcome (lipid) measures and not cardiovascular disease or major cardiovascular event outcomes. Thus our results should mainly act as guidance for whether individuals will reach the target levels of non-HDL-C, LDL-C, and total cholesterol with a specific statin treatment delivered at a certain intensity. Nevertheless, the three point major cardiovascular event outcomes were analysed, but because only five studies6 55 59 64 67 reported these outcomes, the results were limited.

This study was a (network) meta-analysis of aggregate data, and standard practice when dealing with aggregate data is to focus on the final score values to obtain an effect estimate at the study level. Thus, based on this principle, our effect estimates did not adjust for baseline differences. A major constraint underlying this type of adjustment is that baseline data are often not reported in studies, which was the case in the studies in this meta-analysis. Also, if we had included studies that provided baseline data, a different methodological approach would be required, which would have substantially reduced the number of trials in our study pool.94 Nevertheless, meta-analysing randomised controlled trials makes this method feasible and defensible, because the underlying assumption (at least in large randomised controlled trials) is that baseline levels are almost identical in the two (or more) treatment arms, which was also shown to be true in the transitivity assessment as part of our CINeMA evaluation. With meta-analyses of aggregate data, little else can be done about baseline scores, except perhaps a meta-regression where the association between baseline levels and effect sizes can be explored. This approach comes with considerable power limitations, however, even for large meta-analyses. Hence to investigate the role of baseline scores, an individual patient data meta-analysis would be required. We tried contacting the authors for their baseline data, but only three responded.38 73 80 We recommend that these data are reported in future trials to allow the adjusted baseline change scores to be used instead of the final scores.

Conclusions

Rosuvastatin, given at moderate intensity doses, and rosuvastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin, given at high intensity doses, were the most effective treatments in patients with diabetes, modestly reducing levels of non-HDL-C over 12 weeks compared with placebo. Given the potential improvement in accuracy in predicting cardiovascular disease when non-HDL-C is used as the primary target, our findings could inform policy on which statin types and intensities are most effective by reducing non-HDL-C in patients with diabetes and at risk of cardiovascular disease.

What is already known on this topic

In people with diabetes, statins are the basis of primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease by reducing plasma levels of low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), but evidence is lacking on the comparative effectiveness of statins on non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C)

Non-HDL-C is thought to be more strongly associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease than LDL-C in statin users, and therefore might be a better tool for assessing the risk of cardiovascular disease and the effects of treatment

Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for adults with diabetes recommend that non-HDL-C should replace LDL-C as the primary target for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease when taking lipid lowering agents

What this study adds

Rosuvastatin, given at moderate and high intensity doses, and simvastatin and atorvastatin, given at high intensity doses, were the most effective treatments in patients with diabetes, reducing concentrations of non-HDL-C by 2.20-2.31 mmol/L over 12 weeks

In patients at high risk of major cardiovascular events (secondary prevention), atorvastatin at high intensity doses showed the largest reduction in non-HDL-C (~2.0 mmol/L)

These findings can guide decision making for clinicians and support policy guidelines for the management of lipid levels, with non-HDL-C as a primary target, in patients with diabetes

Acknowledgments

We thank the Evidence Synthesis-Working Group at the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research who are funding this project and future ongoing work. This publication presents independent research funded by the NIHR School for Primary Care Research Project 461. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplementary appendix

Contributors: AH, MP, and EK had the initial research idea and obtained funding for this study. AH, MP, and DT formulated the research questions and designed the study. AH and DT searched for published work, selected articles, and extracted data. AH performed all analyses and EK checked over. AH and DT drafted the protocol and the manuscript. MP helped in the searching of articles and data selection and extraction. MP contributed to designing the searches and the statistical analysis plan, writing of the manuscript, and interpreting the findings. MAM, MKR, and EK contributed to the manuscript by providing review comments and edits. AH is the study guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research (461) and was supported by a presidential fellowship held by AH. The research team members were independent from the funding agencies. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The lead author AH affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: Dissemination of this research will be done at the World Heart Congress in October 2022 (https://heart.euroscicon.com/), and through a press release from the University of Manchester, social media and twitter, and charities, including the British Heart Foundation and Heart Research Institute UK.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

Not required.

Data availability statement

AH had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All data are publicly available.

References

- 1. Rydén L, Grant PJ, Anker SD, et al. Authors/Task Force Members. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) Document Reviewers . ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: the Task Force on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J 2013;34:3035-87. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Dieren S, Beulens JW, van der Schouw YT, Grobbee DE, Neal B. The global burden of diabetes and its complications: an emerging pandemic. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17(Suppl 1):S3-8. 10.1097/01.hjr.0000368191.86614.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang X, Xing L, Jia X, et al. Comparative lipid-lowering/increasing efficacy of 7 statins in patients with dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases, or diabetes mellitus: systematic review and network meta-analyses of 50 randomized controlled trials. Cardiovasc Ther 2020;2020:3987065. 10.1155/2020/3987065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. SAVOR-TIMI 53 Steering Committee and Investigators . Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1317-26. 10.1056/NEJMoa1307684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Herrett E, Williamson E, Brack K, et al. StatinWISE Trial Group . Statin treatment and muscle symptoms: series of randomised, placebo controlled n-of-1 trials. BMJ 2021;372:n135. 10.1136/bmj.n135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, et al. CARDS investigators . Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:685-96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins R, Armitage J, Parish S, Sleigh P, Peto R, Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group . MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361:2005-16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13636-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Cholesterol Education Program . National Cholesterol Education Program. Second Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II). Circulation 1994;89:1333-445. 10.1161/01.CIR.89.3.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boekholdt SM, Arsenault BJ, Mora S, et al. Association of LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B levels with risk of cardiovascular events among patients treated with statins: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2012;307:1302-9. 10.1001/jama.2012.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frost PH, Havel RJ. Rationale for use of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol rather than low-density lipoprotein cholesterol as a tool for lipoprotein cholesterol screening and assessment of risk and therapy. Am J Cardiol 1998;81(4a):26B-31B. 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. CKS. Lipid modification - CVD prevention. 2021. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/lipid-modification-cvd-prevention/

- 12. Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group . 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2999-3058. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019;139:e1082-143. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. The PRISMA Extension Statement for Reporting of Systematic Reviews Incorporating Network Meta-analyses of Health Care Interventions . Checklist and Explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777-84. 10.7326/m14-2385%m26030634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharma A, Pagidipati NJ, Califf RM, et al. Impact of regulatory guidance on evaluating cardiovascular risk of new glucose-lowering therapies to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus: lessons learned and future directions. Circulation 2020;141:843-62. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office for National Statistics. Ethnic group, national identity and religion. Measuring equality: A guide for the collection and classification of ethnic group, national identity and religion data in the UK. https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/classificationsandstandards/measuringequality/ethnicgroupnationalidentityandreligion#ethnic-group

- 17. Reiter-Brennan C, Osei AD, Iftekhar Uddin SM, et al. ACC/AHA lipid guidelines: Personalized care to prevent cardiovascular disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2020;87:231-9. 10.3949/ccjm.87a.19078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group . 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 2020;41:111-88. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE guidelines. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. Clinical guideline CG181. 2016. [PubMed]

- 20. Law MR, Wald NJ, Rudnicka AR. Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2003;326:1423. 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials [published Online First: 2019/08/30]. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nikolakopoulou A, Higgins JPT, Papakonstantinou T, et al. CINeMA: An approach for assessing confidence in the results of a network meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003082. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Papakonstantinou T, Nikolakopoulou A, Higgins JPT, et al. CINeMA: Software for semiautomated assessment of the confidence in the results of network meta-analysis. Campbell Syst Rev 2020;16:e1080. 10.1002/cl2.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Follmann D, Elliott P, Suh I, Cutler J. Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:769-73. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90054-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, et al. NICE DSU technical support document 2: a generalised linear modelling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK310366/. [PubMed]

- 26. Bafeta A, Trinquart L, Seror R, Ravaud P. Reporting of results from network meta-analyses: methodological systematic review. BMJ 2014;348:g1741. 10.1136/bmj.g1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:163-71. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Higgins JP, Jackson D, Barrett JK, Lu G, Ades AE, White IR. Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: concepts and models for multi-arm studies. Res Synth Methods 2012;3:98-110. 10.1002/jrsm.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM, Ades AE. Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med 2010;29:932-44. 10.1002/sim.3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MBNMAdose. Dose-response MBNMA Models (version 0.3.0). R-Package. Author: Hugo Pedder. 2021. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MBNMAdose/index.html

- 31. van Valkenhoef G, Lu G, de Brock B, Hillege H, Ades AE, Welton NJ. Automating network meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2012;3:285-99. 10.1002/jrsm.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Valkenhoef G, Tervonen T, de Brock B, et al. Algorithmic parameterization of mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Comput 2012;22:1099-111. 10.1007/s11222-011-9281-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bradburn MJ, Deeks JJ, Berlin JA, Russell Localio A. Much ado about nothing: a comparison of the performance of meta-analytical methods with rare events. Stat Med 2007;26:53-77. 10.1002/sim.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177-88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Caldwell DM, Welton NJ. Approaches for synthesising complex mental health interventions in meta-analysis. Evid Based Ment Health 2016;19:16-21. 10.1136/eb-2015-102275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kip KE, Hollabaugh K, Marroquin OC, Williams DO. The problem with composite end points in cardiovascular studies: the story of major adverse cardiac events and percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:701-7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ 2001;323:101-5. 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Betteridge DJ, Gibson JM, Sager PT. Comparison of effectiveness of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin on the achievement of combined C-reactive protein (<2 mg/L) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (<70 mg/dl) targets in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (from the ANDROMEDA study). Am J Cardiol 2007;100:1245-8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sever PS, Poulter NR, Dahlöf B, Wedel H, Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial Investigators . Different time course for prevention of coronary and stroke events by atorvastatin in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Lipid-Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA). Am J Cardiol 2005;96(5a):39F-44F. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lawrence JM, Reid J, Taylor GJ, Stirling C, Reckless JP. The effect of high dose atorvastatin therapy on lipids and lipoprotein subfractions in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis 2004;174:141-9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim JH, Lee MR, Shin JA, et al. Effects of pravastatin on serum adiponectin levels in female patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis 2013;227:355-9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim JM, Back MK, Yi HS, Joung KH, Kim HJ, Ku BJ. Effect of atorvastatin on growth differentiation factor-15 in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia. Diabetes Metab J 2016;40:70-8. 10.4093/dmj.2016.40.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Koh KK, Quon MJ, Han SH, et al. Simvastatin improves flow-mediated dilation but reduces adiponectin levels and insulin sensitivity in hypercholesterolemic patients. Diabetes Care 2008;31:776-82. 10.2337/dc07-2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Koh KK, Quon MJ, Han SH, et al. Differential metabolic effects of pravastatin and simvastatin in hypercholesterolemic patients. Atherosclerosis 2009;204:483-90. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Koh KK, Oh PC, Sakuma I, Lee Y, Han SH, Shin EK. Rosuvastatin dose-dependently improves flow-mediated dilation, but reduces adiponectin levels and insulin sensitivity in hypercholesterolemic patients. Int J Cardiol 2016;223:488-93. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Son JW, Kim DJ, Lee CB, et al. Effects of patient-tailored atorvastatin therapy on ameliorating the levels of atherogenic lipids and inflammation beyond lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig 2013;4:466-74. 10.1111/jdi.12074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ichihara A, Hayashi M, Ryuzaki M, Handa M, Furukawa T, Saruta T. Fluvastatin prevents development of arterial stiffness in haemodialysis patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;17:1513-7. 10.1093/ndt/17.8.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ishigaki Y, Kono S, Katagiri H, Oka Y, Oikawa S, NTTP investigators . Elevation of HDL-C in response to statin treatment is involved in the regression of carotid atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb 2014;21:1055-65. 10.5551/jat.22095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mori H, Okada Y, Tanaka Y. Effects of pravastatin, atorvastatin, and rosuvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia. Diabetol Int 2013;4:117-25. 10.1007/s13340-012-0103-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chang YH, Lin KC, Chang DM, Hsieh CH, Lee YJ. Paradoxical negative HDL cholesterol response to atorvastatin and simvastatin treatment in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients. Rev Diabet Stud 2013;10:213-22. 10.1900/RDS.2013.10.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chu CH, Lee JK, Lam HC, et al. Atorvastatin does not affect insulin sensitivity and the adiponectin or leptin levels in hyperlipidemic type 2 diabetes. J Endocrinol Invest 2008;31:42-7. 10.1007/BF03345565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu PY, Lin LY, Lin HJ, et al. Pitavastatin and atorvastatin double-blind randomized comPArative study among hiGh-risk patients, including thOse with Type 2 diabetes mellitus, in Taiwan (PAPAGO-T Study). PLoS One 2013;8:e76298. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hadjibabaie M, Gholami K, Khalili H, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of atorvastatin, simvastatin and lovastatin in the management of dyslipidemic type 2 diabetic patients. Therapy 2006;3:759-64. 10.2217/14750708.3.6.759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tekin A, Tekin G, Sezgin AT, Müderrisoğlu H. Short- and long-term effect of simvastatin therapy on the heterogeneity of cardiac repolarization in diabetic patients. Pharmacol Res 2008;57:393-7. 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu K, Han YL, Jing QM, et al. Lipid-modifying therapy in diabetic patients with high plasma non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol after percutaneous coronary intervention. Exp Clin Cardiol 2007;12:48-50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sindhu S, Singh HK, Salman MT, Fatima J, Verma VK. Effects of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and lipid profile in obese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2011;2:261-5. 10.4103/0976-500X.85954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Thongtang N, Piyapromdee J, Tangkittikasem N, Samaithongcharoen K, Srikanchanawat N, Sriussadaporn S. Efficacy and safety of switching from low-dose statin to high-intensity statin for primary prevention in type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2020;13:423-31. 10.2147/DMSO.S219496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cheung RC, Morrell JM, Kallend D, Watkins C, Schuster H. Effects of switching statins on lipid and apolipoprotein ratios in the MERCURY I study. Int J Cardiol 2005;100:309-16. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Diabetes Atorvastin Lipid Intervention (DALI) Study Group . The effect of aggressive versus standard lipid lowering by atorvastatin on diabetic dyslipidemia: the DALI study: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1335-41. 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dallinga-Thie GM, van Tol A, Dullaart RP, Diabetes Atorvastatin lipid intervention (DALI) study group . Plasma pre beta-HDL formation is decreased by atorvastatin treatment in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Role of phospholipid transfer protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1791:714-8. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Goldberg RB, Guyton JR, Mazzone T, et al. Ezetimibe/simvastatin vs atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia: the VYTAL study. Mayo Clin Proc 2006;81:1579-88. 10.4065/81.12.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Insull W, Jr, Kafonek S, Goldner D, Zieve F, ASSET Investigators . Comparison of efficacy and safety of atorvastatin (10mg) with simvastatin (10mg) at six weeks. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:554-9. 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01430-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Janatuinen T, Knuuti J, Toikka JO, et al. Effect of pravastatin on low-density lipoprotein oxidation and myocardial perfusion in young adults with type 1 diabetes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004;24:1303-8. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000132409.87124.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Knopp RH, d’Emden M, Smilde JG, Pocock SJ. Efficacy and safety of atorvastatin in the prevention of cardiovascular end points in subjects with type 2 diabetes: the Atorvastatin Study for Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease Endpoints in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (ASPEN). Diabetes Care 2006;29:1478-85. 10.2337/dc05-2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Miller M, Dobs A, Yuan Z, Battisti WP, Borisute H, Palmisano J. Effectiveness of simvastatin therapy in raising HDL-C in patients with type 2 diabetes and low HDL-C. Curr Med Res Opin 2004;20:1087-94. 10.1185/030079904125004105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schneider JG, von Eynatten M, Parhofer KG, et al. Atorvastatin improves diabetic dyslipidemia and increases lipoprotein lipase activity in vivo. Atherosclerosis 2004;175:325-31. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sever PS, Poulter NR, Dahlöf B, et al. Reduction in cardiovascular events with atorvastatin in 2,532 patients with type 2 diabetes: Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial--lipid-lowering arm (ASCOT-LLA). Diabetes Care 2005;28:1151-7. 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Visseren F, Bouter P, van Loon B, Erkelens W. Treatment of dyslipidaemia with fluvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Drug Investig 2001;21:671-8 10.2165/00044011-200121100-00001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lewin AJ, Kipnes MS, Meneghini LF, et al. Simvastatin/Thiazolidinedione Study Group . Effects of simvastatin on the lipid profile and attainment of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals when added to thiazolidinedione therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Ther 2004;26:379-89. 10.1016/S0149-2918(04)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Behounek BD, McGovern ME, Kassler-Taub KB, Markowitz JS, Bergman M, Pravastatin Multinational Study Group for Diabetes . A multinational study of the effects of low-dose pravastatin in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia. Clin Cardiol 1994;17:558-62. 10.1002/clc.4960171009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Berberoglu Z, Guvener N, Cangoz B, et al. Effects of achieving an LDL-cholesterol level of <70 mg/dL compared with the goal of <100 mg/dL using simvastatin or atorvastatin on cognitive processes in high-risk diabetic patients. Endocrinologist 2009;19:271-9. 10.1097/TEN.0b013e3181c052fa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ferrer-García JC, Sanchez-Ballester E, Albalat-Galera R, Berzosa-Sanchez M, Herrera-Ballester A. Efficacy of atorvastatin for achieving cholesterol targets after LDL-cholesterol based dose selection in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2008;13:183-8. 10.1177/1074248408321461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gentile S, Turco S, Guarino G, et al. Comparative efficacy study of atorvastatin vs simvastatin, pravastatin, lovastatin and placebo in type 2 diabetic patients with hypercholesterolaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab 2000;2:355-62. 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2000.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jialal I, Devaraj S. Statin therapy in acute cardiovascular syndromes. Curr Opin Lipidol 2007;18:610-2. 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282efa566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Dalla Nora E, Passaro A, Zamboni PF, Calzoni F, Fellin R, Solini A. Atorvastatin improves metabolic control and endothelial function in type 2 diabetic patients: a placebo-controlled study. J Endocrinol Invest 2003;26:73-8. 10.1007/BF03345126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Paolisso G, Sgambato S, De Riu S, et al. Simvastatin reduces plasma lipid levels and improves insulin action in elderly, non-insulin dependent diabetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1991;40:27-31. 10.1007/BF00315135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Winkler K, Abletshauser C, Hoffmann MM, et al. Effect of fluvastatin slow-release on low density lipoprotein (LDL) subfractions in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: baseline LDL profile determines specific mode of action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:5485-90. 10.1210/jc.2002-020370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wolffenbuttel BH, Franken AA, Vincent HH, Dutch Corall Study Group . Cholesterol-lowering effects of rosuvastatin compared with atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes -- CORALL study. J Intern Med 2005;257:531-9. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhang A, Vertommen J, Van Gaal L, De Leeuw I. Effects of pravastatin on lipid levels, in vitro oxidizability of non-HDL lipoproteins and microalbuminuria in IDDM patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1995;29:189-94. 10.1016/0168-8227(95)01138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tekin A, Sezgin N, Katircibaşi MT, et al. Short-term effects of fluvastatin therapy on plasma interleukin-10 levels in patients with chronic heart failure. Coron Artery Dis 2008;19:513-9. 10.1097/MCA.0b013e32830d27d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Naci H, Brugts J, Ades T. Comparative tolerability and harms of individual statins: a study-level network meta-analysis of 246 955 participants from 135 randomized, controlled trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:390-9. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hodkinson A, Kontopantelis E. Applications of simple and accessible methods for meta-analysis involving rare events: A simulation study. Stat Methods Med Res 2021;30:1589-608. 10.1177/09622802211022385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Jia P, Lin L, Kwong JSW, Xu C. Many meta-analyses of rare events in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were underpowered. J Clin Epidemiol 2021;131:113-22. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Günhan BK, Röver C, Friede T. Random-effects meta-analysis of few studies involving rare events. Res Synth Methods 2020;11:74-90. 10.1002/jrsm.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gøtzsche PC, et al. CONSORT Group . Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:781-8. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Campbell RT, Willox GP, Jhund PS, et al. Reporting of lost to follow-up and treatment discontinuation in pharmacotherapy and device trials in chronic heart failure: a systematic review. Circ Heart Fail 2016;9:e002842. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Cai T, Abel L, Langford O, et al. Associations between statins and adverse events in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: systematic review with pairwise, network, and dose-response meta-analyses. BMJ 2021;374:n1537. 10.1136/bmj.n1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Di Angelantonio E, Gao P, Pennells L, et al. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration . Lipid-related markers and cardiovascular disease prediction. JAMA 2012;307:2499-506. 10.1001/jama.2012.6571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Mora S, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Discordance of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol with alternative LDL-related measures and future coronary events. Circulation 2014;129:553-61. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Eliasson B, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Zethelius B, Eeg-Olofsson K, Cederholm J, National Diabetes Register (NDR) . LDL-cholesterol versus non-HDL-to-HDL-cholesterol ratio and risk for coronary heart disease in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014;21:1420-8. 10.1177/2047487313494292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Buckley J. Joint British Society Guidelines (JBS3). Heart 2014;100:ii1-67. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Wright AK, Welsh P, Gill JMR, et al. Age-, sex- and ethnicity-related differences in body weight, blood pressure, HbA1c and lipid levels at the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes relative to people without diabetes. Diabetologia 2020;63:1542-53. 10.1007/s00125-020-05169-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Thorlund K, Mills EJ. Sample size and power considerations in network meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2012;1:41. 10.1186/2046-4053-1-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Higgins JPT, Li T, Deeks JJ, eds. Chapter 6: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. 2021. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary appendix

Data Availability Statement

AH had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All data are publicly available.