Abstract

The interaction between enrofloxacin and porcine phagocytes was studied with clinically relevant concentrations of enrofloxacin. Enrofloxacin accumulated in phagocytes, with cellular concentration/extracellular concentration ratios of 9 for polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and 5 for alveolar macrophages (AMs). Cells with accumulated enrofloxacin brought into enrofloxacin-free medium released approximately 80% (AMs) to 90% (PMNs) of their enrofloxacin within the first 10 min, after which no further release was seen. Enrofloxacin affected neither the viability of PMNs and AMs nor the chemotaxis of PMNs at concentrations ranging from 0 to 10 μg/ml. Enrofloxacin (0.5 μg/ml) did not alter the capability of PMNs and AMs to phagocytize fluorescent microparticles or Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Pasteurella multocida, and Staphylococcus aureus. Significant differences in intracellular killing were seen with enrofloxacin at 5× the MIC compared with that for controls not treated with enrofloxacin. PMNs killed all S. aureus isolates in 3 h with or without enrofloxacin. Intracellular S. aureus isolates in AMs were less susceptible than extracellular S. aureus isolates to the bactericidal effect of enrofloxacin. P. multocida was not phagocytosed by PMNs. AMs did not kill P. multocida, and similar intra- and extracellular reductions of P. multocida isolates by enrofloxacin were found. Intraphagocytic killing of A. pleuropneumoniae was significantly enhanced by enrofloxacin at 5× the MIC in both PMNs and AMs. AMs are very susceptible to the A. pleuropneumoniae cytotoxin. This suggests that in serologically naive pigs the enhancing effect of enrofloxacin on the bactericidal action of PMNs may have clinical relevance.

Phagocytes are an important part of the host defense against invading microorganisms. However, some microorganisms have defense mechanisms against chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and intracellular killing by phagocytes. A number of obligate and facultative intracellular bacteria are able to survive in phagocytes, resulting in persistent infections, and antibiotic treatment is required to assist in the elimination of pathogens. Consequently, antimicrobial agents should be able to penetrate phagocytic cells and, most importantly, should maintain their activity inside the cell (34). In this context, it is important that for several antibiotics adverse effects on phagocyte function have been described (35). For this reason, it is important to study interactions between phagocytes, microorganisms, and antibiotics.

Several classes of drugs are actively accumulated in phagocytes; among these are the fluoroquinolones (10, 27, 34, 38). Fluoroquinolones used in human medicine, such as ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and levofloxacin, have been found to accumulate in phagocytic cells in vitro, achieving intracellular concentrations four to eight times higher than the extracellular concentration (5, 10). In vivo, the concentration of fluoroquinolones in alveolar macrophages (AMs) was 14 to 18 times higher than that in serum (38). Enrofloxacin is a fluoroquinolone exclusively developed for companion and farm animals including swine. Its potency against many bacteria (4, 14, 15, 37) and good pharmacokinetic properties (30, 31) suggest that it would be an excellent antimicrobial agent for the treatment of bacterial infections in pigs. A considerable number of clinical studies have been conducted with enrofloxacin. These studies revealed that enrofloxacin is effective in the treatment of porcine respiratory diseases (18, 22, 32). However, data from in vitro experiments that have evaluated the antimicrobial efficacy of enrofloxacin in pigs are scarce. Although much research was done to study the antimicrobial actions of fluoroquinolones in phagocytes of several species (16, 23, 26), no data on the effect of enrofloxacin on interactions between porcine phagocytes and microorganisms are available.

In the study described in the present paper, the interaction between enrofloxacin and phagocytes was studied with concentrations of enrofloxacin found in vivo in clinical settings. As test organisms, we used Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Pasteurella multocida, and Staphylococcus aureus for the following reasons. A. pleuropneumoniae is a pathogen that causes high rates of mortality in pigs as a result of severe infection of the respiratory tract. P. multocida type A is mainly found as a secondary respiratory infection in pigs. S. aureus is commonly used as a test organism to study interactions between phagocytes, microorganisms, and antimicrobial agents. First, the uptake and release of enrofloxacin by porcine AMs or polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) was studied. Second, the effects of enrofloxacin on chemotaxis of PMNs was measured; and third, the effect of enrofloxacin on phagocytosis and the intracellular killing of A. pleuropneumoniae, P. multocida, and S. aureus by porcine PMNs and AMs was evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

An A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 9 reference strain (25), a P. multocida type A reference strain (6), and S. aureus 42 D (20) were stored on polystyrene beads (Microbank; PCH Diagnostica, Haarlem, The Netherlands) at −70°C until they were used.

The bacteria were cultured for 18 to 24 h on sheep blood agar with 0.05% NAD (SBV) plates, passaged to fresh SBV plates, and incubated for 6 h. Then, the bacteria were rinsed off with Eagle minimal essential medium (EMEM), and the numbers of CFU were determined by plating 10-fold dilutions on SBV plates. Bacterial suspensions were stored overnight at 4°C, and on the next day the bacterial suspensions were diluted in EMEM to a concentration of 107 CFU/ml.

Enrofloxacin.

Enrofloxacin (purity, 99.7%) was provided by Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany. For each experiment, a fresh stock solution of 10 mg/ml was prepared in 0.1 N sodium hydroxide. Next, the stock solution was diluted in EMEM or Mueller-Hinton bouillon (MHB) for use in bioassays.

Determination of MICs.

Determination of the enrofloxacin MICs for A. pleuropneumoniae, P. multocida, and S. aureus was carried out by incubating bacteria with various concentrations of enrofloxacin. Bacterial suspensions in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with an optical density at 595 nm of 0.100 (108 CFU/ml) were prepared. These bacterial suspensions were diluted 1:100 in MHB with 0.05% NAD. In microtiter plates, a twofold serial dilution of enrofloxacin was made in MHB containing 0.05% NAD, bacteria were added, and the plates were incubated for 18 to 24 h at 37°C. Final concentrations of enrofloxacin ranged from 10 to 0.0001 μg/ml. Bacteria incubated without enrofloxacin served as positive controls, and MHB without bacteria and enrofloxacin served as a negative control. After incubation, microtiter plates were read turbidimetrically at 595 nm. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of enrofloxacin that inhibited bacterial growth. Determination of the MICs was independently carried out twice for each strain.

Isolation of porcine AMs and PMNs.

Porcine PMNs were isolated from heparinized blood (10 U/ml) from 10- to 14-week-old, clinically healthy, specific-pathogen-free pigs (Dutch Landrace, Institute for Animal Science and Health [ID-DLO] breeding colony, Lelystad, The Netherlands) by the overlay method. Briefly, 1 volume of blood was layered on 1 volume of a Ficoll-Hypaque suspension, and erythrocytes were allowed to sediment for 1 to 2 h at room temperature. The resulting leukocyte-rich top layer was taken and was washed with PBS. Then, 4 volumes of cell suspension in PBS was layered on top of 3 volumes of Ficoll-Hypaque, and these were centrifuged for 30 min with 500 × g. The supernatant was discarded, the contaminating erythrocytes in the pellet were lysed with ammonium chloride, and the PMNs were washed twice in EMEM. AMs were isolated from the lungs of the same animals as described before (36). Briefly, lungs were removed aseptically from euthanized pigs. A funnel was placed in the trachea, and 200 ml of PBS was poured into the lungs. The lungs were massaged gently, and the lavage fluid was poured into sterile tubes. The procedure was repeated two more times, and the tubes were centrifuged (at 180 × g for 10 min). The cells were washed twice in EMEM (by centrifugation at 180 × g for 10 min). PMN and AM suspensions were kept on ice. The cells were counted, and their viability was determined by nigrosine dye exclusion (17) in a hemocytometer. The cells were typed morphologically on hematoxylin-eosin-stained cytospin preparations. Cells were used only if cell purity and viability exceeded 95%.

Determination of uptake and release of enrofloxacin by porcine PMNs and AMs.

Uptake of enrofloxacin by AMs was studied by incubating 3.5 × 107 cells/ml in EMEM without phenol red with various enrofloxacin concentrations for 30 min at 37°C in a head-over-head rotor. Further uptake experiments were performed with AMs and PMNs and with enrofloxacin concentrations of 1 μg/ml (n = 3) or 10 μg/ml (n = 5) for 0, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min. After incubation the cells were centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 5 min, the supernatant was collected, and the cell pellet was resuspended in PBS and homogenized by sonication. For the release studies, PMNs or AMs preincubated with 10 μg of enrofloxacin/ml were suspended in EMEM without phenol red, and the suspension was incubated for 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, and 90 min at 37°C, followed by separation by centrifugation. The supernatants, cell homogenates, and enrofloxacin standard solutions were stored at −20°C until determination of the enrofloxacin concentration by microbiological assay (performed essentially as described by Amsterdam [2]) with Escherichia coli (E. coli 1.23 1069 [MIC, 0.008 μg/ml], a clinical isolate from ID-DLO) as the test organism. Dilutions of supernatants, cell homogenates, and enrofloxacin standard solutions in MHB were incubated with E. coli 1.23 in a final volume of 100 μl in sealed microtiter plates at 37°C for 18 to 24 h. After incubation, 10 μl of 3(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (thiazolyl blue) (MTT; 5 mg/ml in PBS; Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis Mo.) was added (24). After 5 min of incubation at room temperature the bacteria were lysed by adding 100 μl of 20% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate–50% dimethyl formamide (pH 4.7). The contents of the plates were mixed for 5 s and the absorbance at 595 nm was read. As a negative control, MHB or enrofloxacin-free cell homogenate without bacteria was used, and as a positive control, MHB or enrofloxacin-free cell homogenate with bacteria was used. Data were fit to a sigmoid curve, and the dilution that gave 50% of the maximum signal was indicated as the 50% effective concentration (EC50). The enrofloxacin concentration (in micrograms per milliliter) in the cellular compartment was calculated as (EC50 of cell homogenate × volume of the cell homogenate × micrograms of enrofloxacin in standard solution)/(EC50 of enrofloxacin in standard solution × theoretical cell volume). Theoretical cell volumes of 25 μl for 108 PMNs and 200 μl for 108 AMs were used (19). The enrofloxacin concentration (in micrograms per milliliter) in the extracellular compartment was calculated as (EC50 of the supernatant × micrograms of enrofloxacin in standard solution)/EC50 of enrofloxacin in standard solution. The results are expressed as the ratio of the cellular enrofloxacin concentration to the extracellular enrofloxacin concentration (C/E ratio). Lysates of PMNs at concentrations exceeding 3 × 108 cells/ml interfered with the bioassay, so PMN lysates were diluted to establish the enrofloxacin concentration. Lysates of AMs did not interfere with the bioassay.

Chemotaxis assay.

The effect of enrofloxacin on PMN chemotaxis was measured by the Boyden chamber technique (33). A cell culture insert containing a polyethylene terephthalate membrane with a pore size of 3 μm (Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) served as the upper chamber and was placed in a well of a 24-well cell culture plate (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.), which served as the lower chamber. A total of 800 μl of EMEM with 10, 1, or 0.1% pooled normal serum (NS) from conventionally housed pigs as the chemoattractant was added in the lower chamber; EMEM without NS was used as the negative control. Enrofloxacin was added to the lower chambers with or without chemoattractant at final concentrations of 1 or 10 μg/ml. PMNs (107/ml) were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in EMEM without phenol red containing 0, 1, or 10 μg of enrofloxacin per ml, and after incubation, 200 μl of the PMN suspension was added to the upper chamber and the PMNs were allowed to migrate for 1 to 2 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After removal of the cell culture insert, 200 μl of MTT solution was added to the lower chamber. After 4 h of MTT reduction by PMNs, the cells were lysed by adding 1 ml of 20% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate–50% dimethyl formamide (pH 4.7). The absorbance at 595 nm was read. Chemotaxis was expressed as a chemotactic index, which was obtained by dividing the value for chemoattracted PMNs by the value for randomly migrated PMNs in the negative (NS) control. Samples of migrated PMNs were taken for determination of the enrofloxacin concentration.

Serum in phagocytosis and killing assays.

In phagocytosis and killing assays, NS was used for P. multocida and S. aureus but not for A. pleuropneumoniae. A. pleuropneumoniae produces a pore-forming toxin that causes cytolysis of AMs. Therefore, killing experiments involving AMs and A. pleuropneumoniae were performed with neutralizing convalescent-phase serum (CPS). With A. pleuropneumoniae and PMNs, NS (NS serologically naive for A. pleuropneumoniae) was used, but in one killing experiment CPS was also used.

Phagocytosis assay.

The effect of enrofloxacin on phagocytosis of microorganisms by phagocytes was studied by flow cytometry (21) (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Calif.). A. pleuropneumoniae, P. multocida, and S. aureus were labelled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (9). Briefly, bacteria from overnight suspensions were incubated with EMEM containing 0.5 mg of FITC/ml for 30 min at 37°C in a head-over-head rotor. The bacteria were washed three times in EMEM. Viability was determined by counting the numbers of CFU. Yellow-green fluorescent carboxylated modified polystyrene microspheres (fluorospheres; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) with a diameter of 1 μm were used as inert-particle controls. Phagocytes were incubated with 0.0 or 0.5 μg of enrofloxacin/ml for 30 min at 37°C in silicon-coated glass tubes in a head-over-head rotor prior to phagocytosis. An equal volume of FITC-labelled bacteria (107/ml) (ratio, 2 bacteria:1 phagocyte) or fluorospheres (5 × 107/ml) (ratio, 10 fluorospheres:1 phagocyte) in EMEM containing serum at a concentration ranging from 0.001 to 10% was added to AM or PMN suspensions (5 × 106/ml). Phagocytosis was allowed to proceed for 15 min in a head-over-head rotor at 37°C and was stopped by the addition of excess of cold PBS. The phagocytes were separated from nonphagocytized bacteria or fluorospheres by centrifugation (200 × g, 5 min, 4°C). The cells were washed one time in cold PBS, fixed in 1% buffered formalin, and kept at 4°C in the dark until they were analyzed by flow cytometry. Phagocytes were gated by linear amplified forward and side scatter. Gated cells were analyzed by a log amplified green fluorescence assay. Phagocytosis was expressed as the percentage of phagocytes showing a green fluorescence that exceeded the background levels.

Killing assay.

Killing experiments were performed essentially as described by Cruijsen et al. (7). Briefly, in silicone-coated glass tubes 2 ml of phagocytes (107/ml) and 2 ml of microorganisms (107/ml) were mixed and preincubated in the presence of 2% serum at 37°C in a head-over-head rotor (PMNs, 5 min; AMs, 15 min), after which incubation proceeded for 3 h. For killing of A. pleuropneumoniae by AMs, CPS was added, whereas for killing of P. multocida or S. aureus by both PMNs and AMs, NS was added. Experiments with PMNs and A. pleuropneumoniae were performed with NS and were also performed once with CPS. After phagocytosis, 8 ml of cold EMEM was added, and phagocytes were separated from nonphagocytized bacteria by centrifugation (200 × g, 5 min, 4°C). The pellet was washed in cold EMEM to remove adherent bacteria. Phagocytes were resuspended in 4 ml of EMEM with 2% serum and with 0×, 1×, or 5× the MIC of enrofloxacin, and the suspension was incubated at 37°C in a head-over-head rotor. Bacteria without phagocytes and with and without enrofloxacin served as controls. Samples were taken at 0, 60, 120, and 180 min during incubation, and at each sampling 0.5 ml was taken and was added to 4.5 ml of cold EMEM. The sample was centrifuged (200 × g, 5 min, 4°C), the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was lysed by vortexing in 1 ml of PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. The viability of all bacteria except S. aureus was not affected by 0.1% Triton X-100. Lysis of S. aureus was achieved by replacing PBS–0.1% Triton X-100 with distilled water. Bacteria were counted by determination of the number of CFU by plating 50 μl of a 10-fold dilution on SBV plates. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C. Four independent killing experiments were performed. The results were expressed as the ratio of the number of CFU of enrofloxacin-treated bacteria to the number of CFU of their non-enrofloxacin-treated counterparts separately for assays with and assays without phagocytes.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed by SPSS (version 7.5). C/E ratios and data from chemotaxis and phagocytosis assays were log transformed and analyzed by means of analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data from killing experiments were natural log transformed and analyzed by ANOVA.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The phagocytic part of the host defense depends on three essential steps: migration toward the invasion, ingestion, and destruction of the microorganism. Adequate antibiotic compounds should, preferably, not interfere with any of these steps. Most antibiotics accumulate in phagocytic cells, and some were described (35) to adversely affect one or more of the phagocyte functions mentioned above. Interpretation of the results described in the literature is difficult because of the wide variation in the test protocols used. Tests are performed with different microorganisms and sometimes with high concentrations of antibiotic which could never be realized in vivo. Nevertheless, for the fluoroquinolones in general, no adverse effects on phagocyte function were described. However, in contrast to other fluoroquinolones, limited in vitro data on enrofloxacin and phagocytosis are available.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of enrofloxacin on porcine phagocytes by using clinically relevant enrofloxacin concentrations. With both AMs and PMNs, enrofloxacin was taken up to saturation immediately after the start of incubation. Cellular uptake of enrofloxacin is cell type dependent, and the C/E ratio is extracellular concentration independent (Table 1). This is in agreement with other studies (12, 13, 27–29) in which uptake of other quinolones in other species was studied by means of fluorometric and radioactivity assays. Enrofloxacin concentrations were twice as high in PMNs as in AMs. Similar observations were made for ciprofloxacin in mouse and human phagocytes (10, 11). A much higher value was reported for sparfloxacin by using guinea pig peritoneal macrophages (8). As was observed with other quinolones (8, 12, 13, 27–29), we also found that 80 to 90% of the intracellular enrofloxacin was released from phagocytes within 10 min when the phagocytes were placed in enrofloxacin-free medium.

TABLE 1.

C/E ratio for enrofloxacin for porcine AMs and PMNs after incubation with 10 or 1 μg of enrofloxacin and subsequent release of enrofloxacin from cells after 10 min of incubation in enrofloxacin-free medium

| Phagocyte | Enrofloxacin concn (μg/ml of medium) | C/E ratio (mean ± SD [no. of expts]) | % Release after 10 min (mean ± SD [no. of expts]) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMs | 10 | 4.03 ± 1.71 (5) | 81.1 ± 9.0 (3) |

| 1 | 4.96 ± 1.70 (3) | ||

| PMNs | 10 | 7.84 ± 2.20 (5) | 88.5 ± 2.1 (3) |

| 1 | 9.00 ± 2.41 (3) |

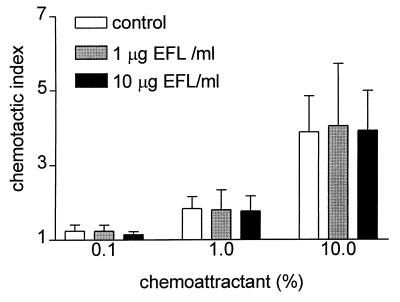

No significant differences (P = 0.426) in chemotactic indices were found between control PMNs and enrofloxacin-containing PMNs (Fig. 1), showing that chemotaxis of PMNs remained unaffected by enrofloxacin, similar to other fluoroquinolones and human PMNs in the leading-front technique (23) and the under-agarose assay (1). The Boyden chamber technique enabled us to show that migrated cells indeed contained high levels of enrofloxacin, with a C/E ratio within the range described for the uptake of enrofloxacin.

FIG. 1.

PMN chemotaxis (Boyden chamber technique) in the presence of different concentrations of enrofloxacin (EFL) and chemoattractant. Values are means + standard deviations.

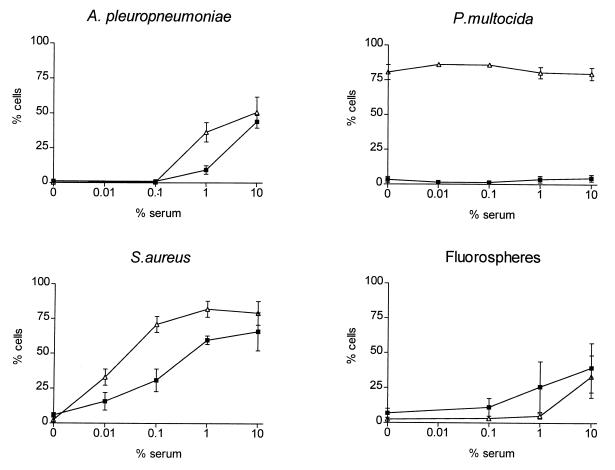

Phagocytosis was performed by flow cytometry with three different fluorescein-labelled microorganisms and with inert particles (fluorospheres) as controls. After the FITC labelling procedure the viabilities of A. pleuropneumoniae, P. multocida, and S. aureus were 80% greater than those of the unlabelled controls. Phagocytosis assays were performed uniformly with various serum concentrations, one concentration of enrofloxacin (0.5 μg/ml), and PMNs and AMs isolated from the same animal. Significant differences (P < 0.001) between PMN- and AM-phagocytizing inert particles or FITC-labelled bacteria were found. Serum increased the uptake of bacteria and particles by AMs or PMNs in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.001) for all bacteria and particles except P. multocida (P = 0.371). In the latter case, phagocytosis by AMs and PMNs was independent of the serum concentration. Under all variations of serum concentration and particle type, no significant differences in phagocytosis by PMNs or AMs were observed in the presence or absence of enrofloxacin (P > 0.570), as was described by others (8, 12, 23) for other quinolones. As is evident from Fig. 2, different mechanisms are involved in the phagocytosis of the microorganisms; e.g., S. aureus is easily taken up in the presence of NS and no serum is needed to phagocytize P. multocida. It is also clear that enrofloxacin does not interfere with either mechanism.

FIG. 2.

Effects of different serum concentrations on the phagocytosis of A. pleuropneumoniae, P. multocida, S. aureus, and fluorospheres by porcine phagocytes. Values are means ± standard deviations. ▵, AMs; ■, PMNs.

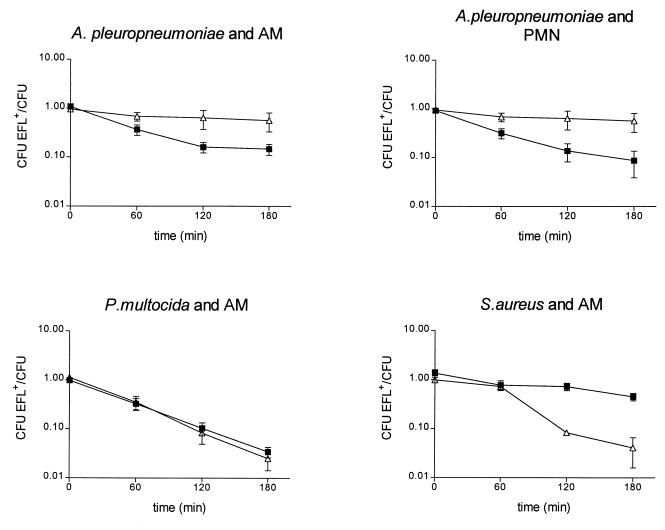

Reduction of bacterial numbers by enrofloxacin alone was dose dependent. By using 1× the MIC of enrofloxacin and phagocytes, the reduction of bacterial numbers in the presence of enrofloxacin was not significantly different compared with the reduction for controls without enrofloxacin. The following results were obtained with 5× the MIC of enrofloxacin. The MIC of enrofloxacin for A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 9 and P. multocida type A was 0.015 μg/ml, and that for S. aureus 42 D was 0.125 μg/ml. No significant differences in phagocyte viability (established by nigrosine dye exclusion) between treated and control preparations were found when phagocytes were incubated with bacteria at any time except at 3 h when phagocytes were incubated with A. pleuropneumoniae. As a result of A. pleuropneumoniae toxin (7), PMN viability decreased to 60% and AM viability decreased to 30%. In controls without bacteria or with P. multocida and S. aureus, phagocyte viability decreased significantly only for AMs (to an average of 80% at 3 h). The effect of phagocyte death is compensated for by expression of the results as the ratio of the number of CFU of enrofloxacin-treated bacteria to the number of CFU of the non-enrofloxacin-treated counterpart separately for incubation with and without phagocytes (Fig. 3) and is given below as a percentage at 3 h.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the effect of enrofloxacin at 5× the MIC on bacterial growth extracellularly (▵) and in porcine phagocytes (■). Values are means ± standard deviations. The significances of the differences (as determined by ANOVA) between the lines of the extracellular and intracellular activities of enrofloxacin were P < 0.006 for A. pleuropneumoniae and AMs, P < 0.001 for A. pleuropneumoniae and PMNs, P > 0.4 for P. multocida and AMs, and P < 0.002 for S. aureus and AMs.

S. aureus was reduced to 4.1% ± 4.3% of the original number of bacteria in the presence of enrofloxacin alone. No S. aureus cells were recovered from PMNs (NS) because this bacterium was killed very rapidly by these phagocytes. This shows that porcine PMNs are very efficient in killing S. aureus, unlike human PMNs, which in the presence of ciprofloxacin (11, 13, 26) or sparfloxacin (12) are bacteriostatic rather than bactericidal (3). Porcine AMs are not capable of intracellular antimicrobial activity against S. aureus, with enrofloxacin (at 5× the MIC, NS), AMs reduced the proportion of S. aureus cells to 44.8% ± 15.7% of the original number. Similar results were described for S. aureus and mouse and guinea pig peritoneal macrophages both without fluoroquinolones and with ciprofloxacin (10) and sparfloxacin (8).

Surprisingly, intracellular S. aureus in AMs appeared to be less susceptible to the bactericidal effect of enrofloxacin than extracellular S. aureus. In previous studies (8, 10) with S. aureus, peritoneal macrophages from different species, and different fluoroquinolones, no direct comparison between intra- and extracellular bactericidal effects was made. How intracellular S. aureus is able to attenuate the intracellular activity of enrofloxacin is not clear since fluoroquinolones are suggested to have an even distribution in the cytoplasm (27).

In contrast to S. aureus, porcine PMNs are not able to phagocytize P. multocida (with NS). Porcine AMs do phagocytize P. multocida, but intracellular bacterial numbers remained constant. In the presence of enrofloxacin, intracellular bacteria were reduced to 3.4% ± 1.7% of their original number. P. multocida was reduced to 2.5% ± 2.2% of the original number by enrofloxacin alone (without AM), confirming the inability of AMs to kill P. multocida and the excellent intracellular penetration of enrofloxacin activity.

AMs with CPS did phagocytize A. pleuropneumoniae, reducing its intracellular numbers to 51.1% ± 17.1% of the original number. The addition of enrofloxacin further reduced the number of A. pleuropneumoniae to 14.7% ± 0.1% of the original number. Since in the absence of AMs enrofloxacin reduced the number of A. pleuropneumoniae to 57% ± 41.3% of the original number, this shows that enrofloxacin has a potentiating effect on AM-associated killing of A. pleuropneumoniae in the presence of CPS. PMNs with NS phagocytized A. pleuropneumoniae but acted bacteriostatically (120.0% ± 58.1% of the original number). Enrofloxacin-laden PMNs, however, reduced the number of A. pleuropneumoniae to 8.7% ± 9.6% of the original number, and in the presence of CPS the number was reduced to 0.02% (data not shown). As we found for AMs with CPS, in PMNs with NS, enrofloxacin had a large additional effect on intracellular killing of A. pleuropneumoniae. By using PMNs with CPS, this effect of enrofloxacin became even more pronounced. Thus, enrofloxacin showed excellent intracellular activity against A. pleuropneumoniae in both AMs and PMNs. However, AMs are bactericidal for A. pleuropneumoniae only in the presence of neutralizing antibodies. Clinically, this means that in serologically naive pigs the enhancing effect of enrofloxacin on the bactericidal action of PMNs will be the most relevant.

In conclusion, this study showed that enrofloxacin accumulated in porcine PMNs and AMs and had no effect on chemotaxic action of porcine PMNs. Furthermore, enrofloxacin did not inhibit the phagocytosis of A. pleuropneumoniae, P. multocida, S. aureus, or fluorospheres by porcine PMNs or AMs. It was also observed that this antimicrobial agent is active intracellularly against A. pleuropneumoniae and P. multocida. Intracellular S. aureus in AMs was less susceptible than extracellular S. aureus to the bactericidal effect of enrofloxacin. Enrofloxacin did not interfere with the intracellular killing of A. pleuropneumoniae by PMNs and AMs; moreover, an additive effect of enrofloxacin was seen. A. pleuropneumoniae is an important pathogen of swine and is not killed efficiently by phagocytic action alone. The present results suggest that enrofloxacin is particularly well suited for use in the treatment of A. pleuropneumoniae infections in pigs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Bayer AG, Business Group Animal Health, Leverkusen, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akamatsu H, Sasaki H, Kurokawa I, Nishijima S, Asada Y, Niwa Y. Effect of nadifloxacin on neutrophil functions. J Int Med Res. 1995;23:19–26. doi: 10.1177/030006059502300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amsterdam D. Susceptibility testing of antimicrobials in liquid media. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1991. pp. 53–105. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson R, Jooné G K. In vitro investigation of the intraphagocytic bioactivities of ciprofloxacin and the new fluoroquinolone agents, clinafloxacin (CI-960) and PD 121628. Chemotherapy (Basel) 1993;39:424–431. doi: 10.1159/000238988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown S A. Fluoroquinolones in animal health. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 1996;19:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.1996.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlier M B, Scorneaux B, Zenebergh A, Desnottes J F, Tulkens P M. Cellular uptake, localization and activity of fluoroquinolones in uninfected and infected macrophages. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;26(Suppl. B):27–39. doi: 10.1093/jac/26.suppl_b.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter G R. Improved hemagglutination test for identifying type A strains of Pasteurella multocida. Appl Microbiol. 1972;24:162–163. doi: 10.1128/am.24.1.162-163.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruijsen A L M, Van Leengoed L A M G, Dekker-Nooren T C E M, Schoevers E J, Verheijden J H M. Phagocytosis and killing of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae by alveolar macrophages and polymorphonuclear leukocytes isolated from pigs. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4867–4871. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4867-4871.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desnottes J F, Diallo N. Effect of sparfloxacin on Staphylococcus aureus adhesiveness and phagocytosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33:737–746. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.4.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drevets D A, Elliott A M. Fluorescence labelling of bacteria for studies of intracellular pathogenesis. J Immunol Methods. 1995;187:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00168-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Easmon C S F, Crane J P. Uptake of ciprofloxacin by macrophages. J Clin Pathol. 1985;38:442–444. doi: 10.1136/jcp.38.4.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Easmon C S F, Crane J P. Uptake of ciprofloxacin by human neutrophils. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;16:67–73. doi: 10.1093/jac/16.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia I, Pascual A, Guzman M C, Perea E J. Uptake and intracellular activity of sparfloxacin in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes and tissue culture cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1053–1056. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.5.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia I, Pascual A, Perea E J. Intracellular penetration and activity of BAY Y 3118 in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2426–2429. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.10.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene C E, Budsberg S C. Veterinary use of quinolones. In: Hooper D C, Wolfson J S, editors. Quinolone antimicrobial agents. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 473–488. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannan P C T, Windsor G D, de Jong A, Schmeer N, Stegemann M. Comparative susceptibilities of various animal-pathogenic mycoplasmas to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2037–2040. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoeben D, Burvenich C, Heyneman R. Influence of antimicrobial agents on bactericidal activity of bovine milk polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;56:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(96)05759-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hudson L, Hay F C. Practical immunology. 2nd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd.; 1980. pp. 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikoma H. Comparative field trial with enrofloxacin and danofloxacin in treatment of swine pleuropneumonia. Bangkok, Thailand: Proceedings of the 13th International Pig Veterinary Society Congress; 1994. p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koga H. High-performance liquid chromatography measurement of antimicrobial concentrations in polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1904–1908. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.12.1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leijh P C J, Van den Barselaar M T, Dubbeldeman-Rempt I, Van Furth R. Kinetics of intracellular killing of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli by human granulocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1980;10:750–757. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830101005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leijh P C J, Van Furth R, Zwet T L. In vitro determination of phagocytosis and intracellular killing of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear phagocytes. In: Weir D M, Blackwell C, Herzenberg L A, editors. Handbook of experimental immunology. 2. Cellular Immunology. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd.; 1986. pp. 46.1–46.21. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madsen K S, Larsen K. Attempt to eradicate Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae from a sow herd; using a strategy with feed medication with Baytril, IER (enrofloxacin) powder 2.5%. Bologna, Italy: Proceedings of the 14th International Pig Veterinary Society Congress; 1996. p. 227. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matera G, Berlinghieri M C, Foti F, Barreca G S, Foca A. Effect of RO 23-9424, cefotaxime, and fleroxacin on functions of human polymorphonuclear cells and cytokine production by human monocytes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:799–807. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.5.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mshana R N, Tadesse G, Abate G, Miorner H. Use of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide for rapid detection of rifampin resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1214–1219. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1214-1219.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen R. Serological characterization of Haemophilus pleuropneumoniae (Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae) strains and proposal of a new serotype: serotype 9. Acta Vet Scand. 1985;26:501–512. doi: 10.1186/BF03546522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen S L, Obel N, Storgaard M, Andersen P L. The effect of quinolones on the intracellular killing of Staphylococcus aureus in neutrophil granulocytes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:617–622. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pascual A. Uptake and intracellular activity of antimicrobial agents in phagocytic cells. Rev Med Microbiol. 1995;6:228–235. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pascual A, Garcia I, Perea E J. Fluorometric measurement of ofloxacin uptake by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:653–656. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.5.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pascual A, Garcia I, Ballesta S, Perea E J. Uptake and intracellular activity of trovafloxacin in human phagocytes and tissue-cultured epithelial cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:274–277. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pijpers A, Heinen E, de Jong A, Verheijden J H M. Enrofloxacin pharmacokinetics after intravenous and intramuscular administration in pigs. J Vet Pharmacol Therap. 1997;20(Suppl. 1):42–43. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richez P, Pedersen Mörner A, de Jong A, Monlouis J D. Plasma pharmacokinetics of parenterally administered danofloxacin and enrofloxacin in pigs. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 1997;20(Suppl. 1):499. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith I M, Mackie A, Lida J. Effect of giving enrofloxacin in the diet to pigs experimentally infected with Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Vet Rec. 1991;129:25–29. doi: 10.1136/vr.129.2.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sunder-Plasmann G, Hofbauer R, Sengoelge G, Horl W H. Quantification of leukocyte migration: improvement of a method. Immunol Invest. 1996;25:49–63. doi: 10.3109/08820139609059290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tulkens P M. Accumulation and subcellular distribution of antibiotics in macrophages in relation to activity against intracellular bacteria. In: Fass R J, editor. Ciprofloxacin in pulmonology. San Francisco, Calif: W. Zuckschwerdt Verlag; 1990. pp. 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van de Broek P J. Antimicrobial drugs, microorganisms, and phagocytes. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:213–245. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Leengoed L A M G, Kamp E M, Pol J M A. Toxicity of Haemophilus pleuropneumoniae for lung macrophages. Vet Microbiol. 1989;19:337–349. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(89)90099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watts J L, Salmon S A, Sanchez M S, Yancey R J. In vitro activity of premafloxacin, a new extended-spectrum fluoroquinolone, against pathogens of veterinary importance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1190–1192. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wise R, Baldwin D R, Andrews J M, Honeybourne D. Comparative pharmacokinetic disposition of fluoroquinolones in the lung. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;28(Suppl. C):65–71. doi: 10.1093/jac/28.suppl_c.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]