This case-control study investigates cognitive impairment, neuropsychiatric diagnoses, and symptoms in COVID-19 survivors compared with patients hospitalized for non-COVID-19 illness.

Key Points

Question

Do neuropsychiatric and cognitive sequalae after hospitalization for COVID-19 differ from sequalae after hospitalization for non–COVID-19 illness of comparable severity?

Findings

In this case-control study of 85 COVID-19 survivors and 61 control patients with non–COVID-19 illness matched for age, sex, and intensive care unit admission status, cognitive impairment was significantly worse in COVID-19 survivors 6 months after symptom onset; however, the absolute difference in cognitive impairment was small. The overall burden of neuropsychiatric and neurologic diagnoses and symptoms appeared similar in cases and controls.

Meaning

In this study, long-term mental health complications in patients who had COVID-19 were significant but seemed not to be unique to COVID-19 because similar complications were observed among individuals hospitalized for non–COVID-19 illness of comparable severity; this highlights the importance of including well-matched control groups when investigating post–COVID-19 sequalae.

Abstract

Importance

Prolonged neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms are increasingly reported in patients after COVID-19, but studies with well-matched controls are lacking.

Objective

To investigate cognitive impairment, neuropsychiatric diagnoses, and symptoms in survivors of COVID-19 compared with patients hospitalized for non–COVID-19 illness.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective case-control study from a tertiary referral hospital in Copenhagen, Denmark, conducted between July 2020 and July 2021, followed up hospitalized COVID-19 survivors and control patients hospitalized for non-COVID-19 illness, matched for age, sex, and intensive care unit (ICU) status 6 months after symptom onset.

Exposures

Hospitalization for COVID-19.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Participants were investigated with the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), neurologic examination, and a semi-structured interview for subjective symptoms. Primary outcomes were total MoCA score and new onset of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) psychiatric diagnoses. Secondary outcomes included specific psychiatric diagnoses, subjective symptoms, and neurologic examination results. All outcomes were adjusted for age, sex, ICU admission, admission length, and days of follow-up. Secondary outcomes were adjusted for multiple testing.

Results

A total of 85 COVID-19 survivors (36 [42%] women; mean [SD] age 56.8 [14] years) after hospitalization and 61 matched control patients with non–COVID-19 illness (27 [44%] women, mean age 59.4 years [SD, 13]) were enrolled. Cognitive status measured by total geometric mean MoCA scores at 6-month follow-up was lower (P = .01) among COVID-19 survivors (26.7; 95% CI, 26.2-27.1) than control patients (27.5; 95% CI, 27.0-27.9). The cognitive status improved substantially (P = .004), from 19.2 (95% CI, 15.2-23.2) at discharge to 26.1 (95% CI, 23.1-29.1) for 15 patients with COVID-19 with MoCA evaluations from hospital discharge. A total of 16 of 85 patients with COVID-19 (19%) and 12 of 61 control patients (20%) had a new-onset psychiatric diagnosis at 6-month follow-up, which was not significantly different (odds ratio, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.39-2.27; P = .87). In fully adjusted models, secondary outcomes were not significantly different, except anosmia, which was more common after COVID-19 (odds ratio, 4.56; 95% CI, 1.52-17.42; P = .006); but no longer when adjusting for multiple testing.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this prospective case-control study, cognitive status at 6 months was worse among survivors of COVID-19, but the overall burden of neuropsychiatric and neurologic signs and symptoms among survivors of COVID-19 requiring hospitalization was comparable with the burden observed among matched survivors hospitalized for non-COVID-19 causes.

Introduction

Prolonged neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms can occur 2 to 6 months after COVID-19,1,2 including mental fatigue (39%-63%), sleep disturbances (24%-26%), and psychological distress, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression and anxiety (4%-23%).3,4,5 This has prompted the World Health Organization to introduce the term long COVID.6 Several disease mechanisms play a role in the development of neuropsychiatric illness during and after COVID-19, including infectious and immunologic causes,7,8 critical illness,9 and the social consequences of lockdown measures.10 However, it remains unknown if COVID-19 is associated with a unique pattern of cognitive and mental impairment compared with other similarly severe medical conditions.

Persistent neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms after hospitalization for severe medical conditions were already known before COVID-19, eg, the post-intensive care syndrome,11 which is associated with delirium,12 and neuropsychiatric sequelae after acute myocardial infarction (AMI).13 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous studies had linked activated immune responses with an increased risk of new-onset mental disorders and cognitive dysfunction.7,8,14,15 Electronic health record (EHR) linkage studies nonetheless indicate that COVID-19 is associated with a greater risk of brain disorders than other respiratory tract infections that require hospitalization.16,17 However, the frequency and phenomenology of new-onset neuropsychiatric and cognitive complications after hospitalization for COVID-19 compared with hospitalizations for other causes is poorly investigated, and prospective clinical studies with adequately matched controls are scarce. Of all studies on post–COVID-19 conditions published by April 2021, only 21% included control individuals and 13% had matched control individuals.18 Most studies reporting on increased neuropsychiatric and cognitive complications in patients with COVID-19 are based on internet or telephone surveys or EHRs19,20 and have historical or no control groups.21,22,23 Matched and prospectively enrolled patients hospitalized during the pandemic for non-COVID-19 illnesses are required to control for the negative societal effects of the lockdown measures on mood and cognitive function, which cannot be achieved using historical cohorts.10,18,24 Here, to our knowledge, we conducted the first study characterizing 6-month neuropsychiatric and cognitive burden in prospectively enrolled survivors of COVID-19 compared with matched patients hospitalized for non-COVID-19 causes during the same time of the pandemic.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Inclusion of Cases

We conducted a prospective study of all patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19 at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark, from March 2020 through January 2021 (covering the peaks of the first 2 waves of the pandemic in Denmark). All patients hospitalized for COVID-19 were invited for 6-month follow-up after symptom onset from June 2020 through July 2021. The Ethics Committee and the Data Protection Agency of the Capital Region of Denmark approved the study (H-20026602, P-2020-497). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines were used. Verbal and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Inclusion criteria were positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results by nasopharyngeal/tracheal testing, hospitalization for COVID-19, and age 18 years or older. Exclusion criteria were lack of Danish or English language proficiency and dementia.

Inclusion of Matched Control Patients

We recruited control patients matched for age, sex, and intensive care unit (ICU) status from the same hospital, including patients in the ICU (eTable 2 in the Supplement) who were admitted from February 2020 through January 2021, and patients who were not admitted to the ICU with ST-elevation myocardial infarction who were admitted to the coronary care unit for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (without a history of ICU admission) from July 2020 through March 2021 (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). We chose patients with AMI as additional control patients because AMI is an acute life-threatening disorder, like COVID-19, with potential psychological effect. Control patients were matched 1:1 for age (±7 years) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement) and same sex as the corresponding patient with COVID-19 with and without ICU admission.

Inclusion criteria for control patients were hospitalization for non-COVID-19 causes, negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR result by nasopharyngeal/tracheal testing during hospitalization, age 18 years or older, and residency within the same catchment area in the Capital Region of Copenhagen. Additional inclusion criteria for the ICU sample were 4 or more days’ ICU admission and 10 or more days’ total admission length.

Exclusion criteria were lack of Danish or English language proficiency, severe central nervous system injury during admission requiring neurorehabilitation, dementia, cerebral neoplasm, active psychosis requiring psychiatric admission, congenital intellectual disability, and/or previous SARS-CoV-2 positive PCR or antibody test result.

Assessments

All patients were evaluated by the same trained physician (V.N.) with structured face-to-face interview, cognitive and neuropsychiatric evaluations, neurologic examination, and a semi-structured interview for subjective symptoms, supervised by the same senior psychiatry consultant (M.B.) and senior neurology consultant (D.K.). Routine clinical information was collected via EHR.

Neuropsychiatric Interview

The validated interviewer-administered, structured diagnostic psychiatric interview Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI version 5.0.0) was used to determine International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis.25 All cases and control patients admitted to the ICU were evaluated by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.26 Participants were interviewed about prior psychiatric and neurologic disorders, in addition to inspecting the EHR containing information on all living people in the eastern part of Denmark (half of the Danish population), ensuring that diagnoses made during the investigation were novel. We also retrieved diagnoses through the system information on hospital contacts in the remainder of Denmark to search for prior hospital contacts for mental disorders. All diagnoses were according to ICD-10 criteria.

Cognitive Assessment and Neurologic Evaluation

Cognitive status was assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).27 We assessed cranial nerve status, sensory-motor function including reflexes, coordination, gait, and modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at discharge based on the physical examination and EHR.

Self-experienced Neuropsychiatric, Cognitive, and Neurologic Symptoms

A semistructured interview was conducted to assess new-onset neuropsychiatric, cognitive, and neurologic symptoms as compared with the patients’ self-reported status before admission. Symptoms were only registered if they were present at the time of examination and consistent with a new-onset or worsening symptom compared with before admission (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Basic Clinical Information

We collected routine clinical and laboratory data including age, sex, medication, previous medical history, education, suspicion of delirium during admission based on treatment with antipsychotics (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement), laboratory findings, results from brain imaging, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, electroencephalography, nerve conductions studies, and electromyography. Hospital disease severity was registered on an ordinal scale.3

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were (1) MoCA score (total score and dichotomized in normal vs abnormal using prespecified cutoffs of MoCA26 or lower27 and 24 or lower28) and (2) any new-onset psychiatric diagnoses according to ICD-10 criteria and assessed by the MINI in survivors of COVID-19 (exposed group) compared with patients who did not have COVID-19(matched control group). Secondary outcomes included the presence of specific psychiatric diagnoses (eg, depression), self-reported symptoms of neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms at the time of examination (eTable 1 in the Supplement), and findings from the neurologic examination.

Statistical Analysis

Primary and secondary outcomes were evaluated in exposed cases vs matched controls, and results were based on a basic adjusted model (adjusted for age and sex) and a fully adjusted model (adjusted for age, sex, ICU admission, total admission days, and days to follow-up); eAppendix 1 in the Supplement shows power calculations. The cognitive primary outcome assessed by MoCA was left skewed and analyzed using linear models after logarithmic transformation of MoCA values. Results are presented as geometric means with 95% CIs. All binary outcomes, including the neuropsychiatric primary outcome, were analyzed in basic and fully adjusted logistic regression models and presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CI, and P values were calculated using the likelihood ratio statistic to account for infrequent values. Nonbinary, categorical variables were compared with Pearson χ2 test and continuous variables with linear models. Continuous variables being concentrations or ratios were log-transformed before analysis. Change in MoCA score from discharge to follow-up was analyzed with a linear model with log transformation and presented as geometric means with 95% CI. P values of secondary outcomes were adjusted for multiple testing using the Holm method29 separately for psychiatric diagnoses, subjective symptoms, and neurologic examination. A 2-tailed P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted by one of us (R.H.B.C.) using R, version 4.1.1 (The R Project).

Results

A total of 85 patients (36 [42%] women; mean [SD] age, 56.8 years) who were hospitalized for COVID-19 and 61 age-, sex-, and ICU status–matched control patients underwent neuropsychiatric and cognitive evaluations at 6-month follow-up from COVID-19 symptom onset (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Individuals who declined participation did not differ regarding age and sex but differed in admission length (shorter) and severity (less) from study participants (eTable 5 in the Supplement). However, there were no significant differences between individuals declining participation in the case group compared with individuals declining participation in the matched control group (eTable 6 in the Supplement). The mean (SD) age of the COVID-19 group compared with the matched control group was 56.8 (14) years vs 59.4 (13) years (P = .25), female sex was 42% vs 44% (P = .82), total median (IQR) days of admission was 15 ( 4-37) vs 13 ( 3-41) (P = .65), respectively, and median (IQR) follow-up time after COVID-19 symptom onset was 165 (130-192) days. Peak C-reactive protein values during admission, number of total comorbidities, education levels, and disease severity were not different. Suspected delirium was treated with haloperidol less frequently in patients with COVID-19 compared with controls (17% vs 33%; P = .02) (Table 1; eTables 3 and 4 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Demographics, Past Medical History, and Admission Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 (n = 85) | Non–COVID-19 (n = 61) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 56.8 (14) | 59.4 (13) | .25 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 36 (42) | 27 (44) | .82 |

| Male | 49 (58) | 34 (56) | NA |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.0 (6) | 25.8 (5) | .02 |

| Education | |||

| Length, mean (SD), y | 13.39 (2.66) | 13.33 (2.47) | .89 |

| Primary school | 9 (10.6) | 3 (4.9) | .61 |

| Vocational training or gymnasium | 28 (32.9) | 22 (36.1) | NA |

| Higher education | |||

| Short cycle | 14 (16.5) | 14 (23.0) | NA |

| Medium cycle | 18 (21.2) | 10 (16.4) | NA |

| Long cycle | 16 (18.8) | 12 (19.7) | NA |

| Past medical history | |||

| Any medical comorbidity | 60 (71) | 44 (72) | .84 |

| Depression | 10 (12) | 10 (16) | .42 |

| PTSD | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Anxiety | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | .94 |

| Schizophrenia | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Alcohol abuse | 0 | 5 (8) | .07 |

| Stroke | 0 | 8 (13) | .03 |

| Epilepsy | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Hypertension | 22 (26) | 23 (38) | .13 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 10 (12) | 19 (31) | .004 |

| Malignancy | 5 (6) | 8 (13) | .11 |

| Asthma | 14 (16) | 3 (5) | .03 |

| COPD | 3 (4) | 4 (7) | .40 |

| Autoimmune disease | 4 (5) | 6 (10) | .23 |

| Admission characteristics | |||

| Duration of total admission, median (IQR), d | 15 (4-37) | 13 (3-41) | .65 |

| Haloperidol treatment for suspected delirium | 14 (17) | 20 (33) | .02 |

| Highest severity scale during hospitalizationb | |||

| 3: Admitted, not requiring oxygen | 20 (23.5) | 19 (31.1) | .63 |

| 4: Admitted, requiring oxygen | 17 (20.0) | 8 (13.1) | |

| 5: Admitted, requiring HFNC or NIV | 14 (16.5) | 1 (1.6) | |

| 6: Admitted, requiring IMV or ECMO | 34 (40.0) | 33 (54.1) | |

| Dexamethasone treatment | 35 (41) | NA | NA |

| Remdesivir treatment | 32 (38) | NA | NA |

| Peak | |||

| CRP values, mg/L | 190 (73-328) | 204 (36-330) | .74 |

| Leukocytes values, E9/L | 12.8 (7-18) | 16.3 (11-21) | .02 |

| ALT values, U/L | 89 (38-157) | 118 (56-324) | .006 |

| ICU characteristicsc | |||

| Admission | 43 (51) | 34 (56) | .54 |

| Duration of admission, median (IQR), d | 16 (9-26) | 11 (6-29) | .28 |

| Dialysis treatment | 8 (19) | 9 (26) | .32 |

| Requiring inotropic agents | 31 (72) | 27 (79) | .46 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 34 (79) | 33 (97) | .02 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, median (IQR), d | 16 (10-27) | 6 (3-17) | .002 |

| Propofol sedation | 34 (79) | 33 (97) | .02 |

| Midazolam sedation | 19 (44) | 7 (21) | .03 |

| ARDS | 32 (74) | 2 (6) | <.001 |

| Prone ventilation | 24 (55) | 1 (3) | <.001 |

| ECMO | 9 (21) | 0 | .005 |

| Time from discharge to follow-up, median (IQR), d | 130 (90-165) | 103 (87-135) | .10 |

| Time from COVID-19 symptom debut to follow-up, median (IQR), d | 165 (130-192) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula for oxygen therapy; ICU, intensive care unit; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Pearson χ2 test was used for categorical values, Wilcoxon rank sum test for comparison of medians, Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test for ordinal variables, and t test for comparison of means.

Severity scale used from previous study3 characterizing post–COVID-19 conditions. Ordinal scale 1 to 7: 1 and 2 represents patients not hospitalized and 7 represent patients who died during hospitalization, therefore 1, 2, and 7 are not included in the Table.

Percentage in ICU characteristics is for total ICU admitted patients.

Primary Outcomes

Cognition

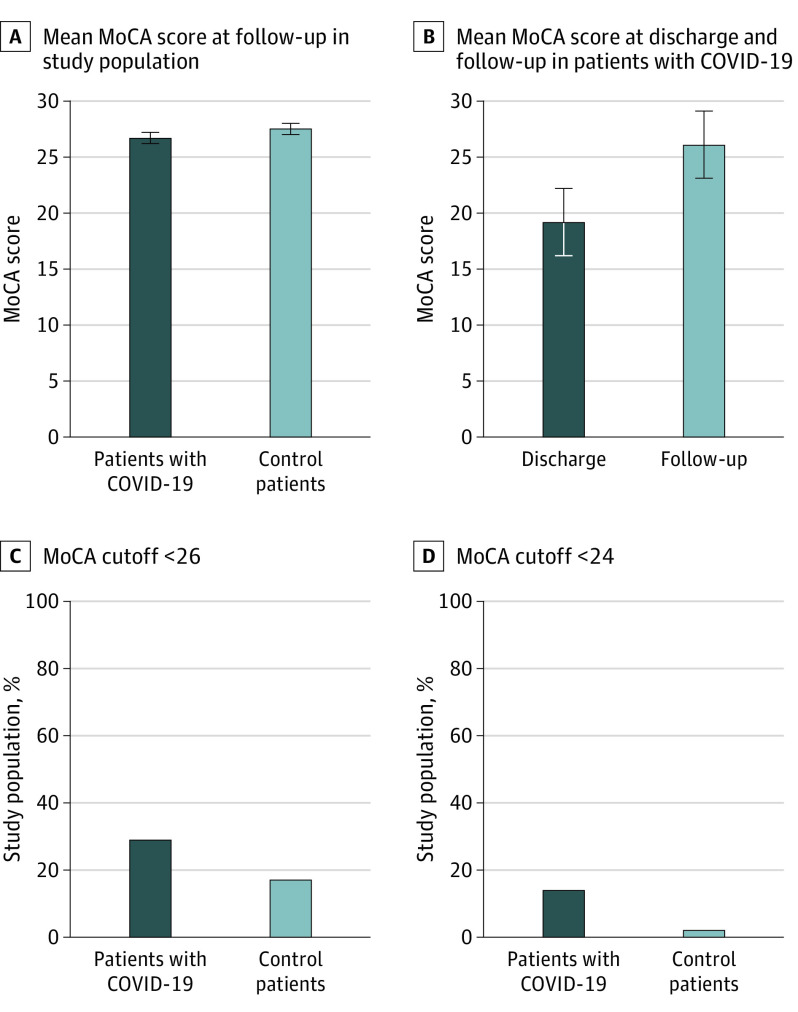

Total geometric mean MoCA score at 6-month follow-up was lower for the COVID-19 group with a geometric mean of 26.7 (95% CI, 26.2-27.1; P = .01) compared with the matched control group with a geometric mean of 27.5 (95% CI, 27.0-27.9) (Figure 1A). Using the cutoff of MoCA scores of 26 or less, the frequency of a positive test result among COVID-19 survivors was 29% compared with 17% among the matched controls, where COVID-19 survivors were more cognitively affected (P = .03) also by this cutoff (OR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.10-6.40). Using MoCA cutoff of 24 or less, abnormal test was similarly more frequent (P = .003) among COVID-19 survivors compared with control patients (14% vs 2%), with an OR of 10.72 (95% CI, 1.96-200.75) (Figure 1C and 1D). The only different MoCA subscore was attention, which was lower in the COVID-19 group (OR, 5.40; 95% CI, 5.25-5.55; P = .009) compared with the matched control patients (OR, 5.70; 95% CI, 5.52-5.88; P = .009) (eTable 7 in the Supplement). Overall, MoCA differences remained lower in patients with COVID-19 after adjusting for education level, disease severity, intubation, comorbidities, and delirium in sensitivity analyses (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Cognitive Assessment With Montreal Cognitive Assessment in COVID-19 Survivors and Matched Control Patients.

A, Fully adjusted geometric mean MoCA score in 85 patients with COVID-19 and 60 control patients after hospitalization. Error bars indicate 95% CI. B, Geometric mean MoCA score of 15 patients with COVID-19 evaluated at discharge and follow-up. In total, 12 patients improved (8 with ≥5 points), 2 patients had no change and only 1 worsened, possibly owing to a minor left hemispheric stroke occurring a few weeks after discharge. C and D, Patients with and without COVID-19 stratified according to normal and abnormal findings of the MoCA based on a cutoff score of 26 or lower, respectively, and a MoCA cutoff score of 24 or less. The 2 groups were compared using Pearson χ2test.

Differences in MoCA From Discharge to Follow-up

A subset of patients with COVID-19 (n = 15) underwent cognitive evaluation at the time of hospital discharge and at follow-up.30 At hospital discharge, the geometric mean MoCA score was 19.2 (95% CI, 15.2-23.2), which improved (P = .004) by a mean change from discharge by 6.9 (95% CI, 2.7-11.2) to a geometric mean MoCA score of 26.1 (95% CI, 23.1-29.1) at follow-up (Figure 1B; eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

New-Onset Psychiatric Diagnoses

Sixteen of 85 COVID-19 survivors (19%) and 12 of 61 control patients (20%) developed a new-onset psychiatric diagnosis at 6-month follow-up, which was not significantly different (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.39-2.27; P = .87) (Figure 2; Table 2). Further adjustments for intubation, disease severity, and comorbidities did not significantly influence the results (eTable 9 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. New-Onset Psychiatric International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) Diagnoses and Neuropsychiatric and Cognitive Symptoms in Survivors of COVID-19 and Matched Control Patients.

Eighty-five patients with COVID-19 and 61 patients that did not have COVID-19 (control patients) were seen at approximately 6 months after COVID-19 symptom debut, for a face-to-face interview including the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). A, The frequencies of new-onset psychiatric diagnoses according to ICD-10, investigated via the MINI. “Psychiatric, any” and “anxiety, any” represent any new-onset psychiatric diagnosis and any new-onset anxiety diagnosis (panic attacks with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without panic attacks, and/or generalized anxiety), respectively. B, The frequencies of subjective neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms. After correction for multiple testing, the differences in new-onset generalized anxiety and altered sense of smell were no longer significant (P = .30 and P = .07, respectively).

a Statistically significant difference (fully adjusted odds ratio [95% CI] = 0.13 [0.01-0.94]; P = .04). Adjusted P values for age, sex, intensive care unit admission, admission days, and days to follow-up.

b Statistically significant difference (fully adjusted odds ratio [95% CI] = 4.56 [1.52-17.42]; P = .006). Adjusted P values for age, sex, intensive care unit admission, admission days, and days to follow-up.

Table 2. New-Onset Psychiatric Diagnoses, MoCA Score, and Self-reported Neuropsychiatric and Cognitive Symptoms in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 and Patients Without COVID-19 Seen After Discharge From Hospital.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Adjusted model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basica | Fullya | |||||

| COVID-19 (n = 85) | Non–COVID-19 (n = 61) | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| ICD-10 psychiatric disorders | ||||||

| New-onset psychiatric disorder, any | 16 (19) | 12 (20) | 0.87 (0.37- 2.07) | .74 | 0.93 (0.39- 2.27) | .87 |

| Current depression | 9 (11) | 4 (7) | 1.62 (0.48- 6.42) | .44 | 1.71 (0.50- 6.89) | .41 |

| Previous depressive episode | 10 (12) | 10 (17) | 0.61 (0.22- 1.68) | .34 | 0.55 (0.19- 1.59) | .27 |

| Severe depression | 0 | 1 (2) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Dysthymia | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Anxiety disorder in total | 10 (12) | 10 (17) | 0.61 (0.23- 1.62) | .32 | 0.65 (0.24- 1.77) | .39 |

| Panic anxiety without agoraphobia | 5 (6) | 3 (5) | 0.99 (0.21- 5.44) | .99 | 1.01 (0.20- 5.79) | >.99 |

| Panic anxiety with agoraphobia | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 0.79 (0.09- 7.17) | .82 | 0.90 (0.09- 9.01) | .92 |

| Generalized anxiety | 1 (1) | 5 (8) | 0.13 (0.01- 0.87) | .03 | 0.13 (0.01- 0.94) | .04b |

| Agoraphobia without panic attacks | 2 (2) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Hypomanic episode | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Manic episode | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Social phobia | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0.59 (0.02- 15.77) | .72 | 0.56 (0.02- 15.80) | .70 |

| OCD | 1 (1) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| PTSD | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 2.35 (0.18- 66.26) | .52 | 6.11 (0.26- 632.11) | .28 |

| Psychotic episode | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cognitive testing, MoCA score | ||||||

| Geometric, mean (95% CI)c | 26.7 (26.2-27.1) | 27.5 (27.0-27.9) | NA | .02 | NA | .01 |

| <26 | 25 (29) | 10 (17) | 2.34 (1.02- 5.70) | .04 | 2.56 (1.10- 6.40) | .03 |

| <24 | 12 (14) | 1 (2) | 10.75 (1.98- 200.47) | .003 | 10.72 (1.96- 200.75) | .003 |

| Symptom questionnaire in ICU patients | ||||||

| HADS, median (IQR)d | ||||||

| Anxiety | 5 (3-12) | 6 (3-9) | 1.02 (−1.14 to 3.18) | .35 | 1.05 (−1.16 to 3.25) | .35 |

| HADS | 5 (2-9) | 5 (2-9) | 0.18 (−1.77 to 2.12) | .86 | 0.65 (−1.26 to 2.55) | .50 |

| Neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms | ||||||

| Increased irritability | 26 (31) | 20 (33) | 0.81 (0.39- 1.69) | .57 | 0.82 (0.39- 1.73) | .60 |

| Feeling depressed/loss of pleasure in activity | 15 (18) | 16 (26) | 0.57 (0.25- 1.32) | .19 | 0.59 (0.25- 1.36) | .21 |

| Social isolation owing to phobia/anxiety/discomfort | 5 (6) | 6 (10) | 0.51 (0.14 to 1.83) | .30 | 0.48 (0.13- 1.75) | .27 |

| Auditory/visual hallucinations | 2 (2) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Episodes of anxiety | 13 (15) | 13 (21) | 0.60 (0.25- 1.45) | .26 | 0.61 (0.25- 1.49) | .28 |

| Flashback/nightmare of admission | 7 (8) | 6 (10) | 0.68 (0.20- 2.30) | .53 | 0.70 (0.20- 2.44) | .57 |

| Emotional lability | 24 (28) | 26 (43) | 0.53 (0.26- 1.07) | .08 | 0.52 (0.25- 1.05) | .07 |

| Short-term/long-term memory problems | 37 (44) | 19 (31) | 1.82 (0.91- 3.77) | .09 | 1.83 (0.90- 3.83) | .10 |

| Reduced concentration | 35 (41) | 21 (34) | 1.33 (0.66- 2.71) | .42 | 1.33 (0.66- 2.71) | .43 |

| Speech difficulties | 6 (7) | 2 (3) | 2.46 (0.51- 17.98) | .27 | 2.60 (0.53- 20.03) | .25 |

| Mental and physical fatigue | 46 (54) | 30 (49) | 1.14 (0.57- 2.28) | .70 | 1.17 (0.59- 2.36) | .65 |

| Sleep disturbance | 17 (20) | 15 (25) | 0.72 (0.32- 1.61) | .42 | 0.70 (0.31- 1.59) | .39 |

| New-onset pain reducing quality of life | 24 (28) | 14 (23) | 1.18 (0.53- 2.60) | .69 | 1.27 (0.55- 2.93) | .57 |

| Memories of ICU admission | ||||||

| Factual memories | .48e | .36 | ||||

| Remembers fully | 16 (37) | 9 (26) | 1.37 (0.57- 3.27) | 1.53 (0.62- 3.85) | ||

| Remembers partly | 16 (37) | 13 (38) | NA | NA | ||

| No factual memories | 11 (26) | 12 (35) | NA | NA | ||

| Delusional and distressing memories | 30 (70) | 28 (82) | 0.50 (0.15- 1.50) | .21 | 0.49 (0.14- 1.58) | .24 |

| Resumption of work | ||||||

| Back to work | .44f | |||||

| Full-time | 30 (35) | 18 (30) | NA | NA | NA | |

| Part-time | 20 (24) | 10 (16) | NA | NA | NA | |

| Still on sick leave | 9 (11) | 7 (11) | NA | NA | NA | |

| Currently unemployed/retired | 26 (31) | 26 (43) | NA | NA | NA | |

Abbreviations: HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICU, intensive care unit; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NA, not applicable; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; OR, odds ratio; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

OR presented with 95% CI and P values based on the likelihood ratio test and adjusted for age and sex (basic model) and for age, sex, ICU admission, duration of admission, and time to follow-up full model).

Corrections were applied for multiple comparisons of the secondary outcomes of specific psychiatric disorders and neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms, and the frequency of generalized anxiety was no longer significantly different, P = .30.

Total MoCA score presented as geometric means with estimated 95% CI. P values shown as basic and fully adjusted. One patient who had COVID-19 did not complete the full MoCA test owing to headache when concentrating; thus, data are on 84 patients with COVID-19.

HADS questionnaires were completed in the subgroup of ICU-admitted patients with a response rate of 37/43 (86%) in COVID-19 and 33/34 (97%) in non-COVID ICU patients and adjusted OR calculated as linear models for HADS outcome.

Cumulative OR with 95% CI was calculated for the ordinal variable of “memories of ICU.”

Pearson χ2 test was used for nonbinary values with a single P value calculated for a multiple contingency table and single P value is calculated for a multiple contingency table without any adjustments.

Secondary Outcomes

New-Onset Specific Psychiatric Diagnoses

We observed a similar frequency of specific new-onset psychiatric diagnoses in patients with COVID-19 and matched control patients. Only new-onset generalized anxiety was less frequent in the COVID-19 group compared with the control group, 8% vs 1% (fully adjusted OR, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.01-0.94; P = .04); however, after adjusting for multiple testing, this difference was nonsignificant (P = .30) (Table 2 and Figure 2A).

Subjective Symptoms

Semistructured interview to assess new-onset symptoms at follow-up revealed that 69 of 85 of survivors of COVID-19 (81%) and 57 of 61 matched control patients (93%) complained of at least 1 symptom (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The frequencies of specific neuropsychiatric, cognitive, and neurologic symptoms were similar between cases and controls, including cognitive impairment of concentration or memory complaints in 44 of 85 (52%) and 30 of 61 (49%) patients with COVID-19 and control patients, respectively (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.58-2.30; P = .68). Only anosmia/hyposmia was more often reported by survivors of COVID-19 than control patients, 19 of 85 (22%) vs 4 of 61 (7%) (fully adjusted OR, 4.56; 95% CI, 1.52-17.42; P = .006); however, after adjusting for multiple testing, this was nonsignificant (P = .07) (Table 2, Table 3, and Figure 1B).

Table 3. Neurologic Examination Findings and Complications in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 and Patients Without COVID-19 Seen After Discharge From Hospital.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Adjusted model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 (n = 85) | Non-COVID (n = 61) | Basica | Fullb | |||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Neurologic symptoms | ||||||

| Disturbance | ||||||

| Smell | 19 (22) | 4 (7) | 4.41 (1.51-16.32) | .006 | 4.56 (1.52-17.42) | .006b |

| Taste | 22 (26) | 8 (13) | 2.68 (1.10-7.14) | .03 | 3.38 (1.26-9.60) | .01b |

| New-onset unexplained paresthesia | 4 (5) | 2 (3) | 1.15 (0.20-8.62) | .88 | 1.39 (0.22-11.68) | .73 |

| Worsening of known paresthesia | 0 | 1 (2) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment-related paresthesia/neuropathic pain | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 0.41 (0.02-4.64) | .47 | 0.41 (0.01-5.29) | .50 |

| New-onset persistent headache (>3 headache d/wk) | 5 (6) | 4 (7) | 0.85 (0.21-3.70) | .83 | 0.82 (0.19-3.64) | .78 |

| Worsening of headache disorder (migraine/tension type) | 2 (2) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Neurologic examination findings | ||||||

| Luria’s 3-step test, abnormal | 7 (8) | 4 (7) | 1.84 (0.48-8.15) | .38 | 2.18 (0.53-11.11) | .29 |

| Gait | ||||||

| Normal | 80 (94) | 50 (82) | 0.25 (0.06-0.84) | .02 | 0.31 (0.07-1.25) | .10c |

| Assisted with walking device | 4 (5) | 10 (16) | NA | NA | ||

| Wheelchair | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | NA | NA | ||

| Motor examination | ||||||

| Normal | 75 (88) | 51 (84) | 0.80 (0.29-2.26) | .67 | 1.07 (0.33-3.58) | .91c |

| Hemiparesis | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | NA | NA | ||

| Paraparesis inferior | 2 (2) | 3 (5) | NA | NA | ||

| Tetraparesis | 1 (1) | 4 (7) | NA | NA | ||

| Single extremity paresis | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | ||

| Facial palsy | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | NA | NA | ||

| Coordination | ||||||

| Normal | 83 (98) | 58 (95) | 0.45 (0.06-2.84) | .39 | 0.38 (0.03-4.08) | .42c |

| Ataxia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | ||

| Terminal tremor | 2 (2) | 3 (5) | NA | NA | ||

| Reflexes | ||||||

| Normal | 80 (94) | 53 (87) | 0.50 (0.13-1.74) | .28 | 0.84 (0.20-3.55) | .81c |

| Hyperreflexia | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | NA | NA | ||

| Hyporeflexia | 4 (5) | 6 (10) | NA | NA | ||

| mRS at follow-up, median (IQR) | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | NA | .45d | NA | NA |

| Neurologic complications | ||||||

| Ischemic stroke between admission and follow-up | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 0.68 (0.07-6.43) | .72 | 1.22 (0.12-13.26) | .86 |

| Transitory ischemic attack | 1 (1) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Epilepsy | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0.53 (0.02-14.45) | .67 | 0.18 (0-8.62) | .38 |

| Encephalitis/meningitis | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bell facial palsy | 1 (1) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Meralgia paresthetica | 5 (6) | 2 (3) | 2.05 (0.40-15.36) | .40 | 2.37 (0.42-19.86) | .39 |

| Restless legs syndrome | 0 | 1 (2) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

OR presented with 95% CI and P values based on the likelihood ratio test and adjusted for age and sex (basic model) (a) and for age, sex, ICU admission, duration of admission, and time to follow-up (full model) (b).

Corrections were applied for multiple comparisons of the secondary outcomes of subjective symptoms and differences in smell (P = .07) and taste (P = .17) disturbance were no longer significant.

OR and a single P value was calculated for the odds of a normal vs abnormal finding in the otherwise multiple categorical variables of gait, motor examination, coordination, and reflexes.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test for comparison of median mRS at follow-up without adjustment.

Neurologic Examination

There were no major differences in neurologic deficits except that survivors of COVID-19 were less frequently dependent on walking aids (6%) compared with control patients (18%) in the basic adjusted (OR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.06-0.84; P = .02) but not in the fully adjusted model (OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.07-1.25; P = .10). Similarly, we did not observe any group differences in the frequency of neurologic complications between discharge and follow-up. Frequency of meralgia paresthetica owing to ventilation in the prone position was noted in 5 of 85 survivors of COVID-19 (6%) vs 2 of 61 control patients (3%) (fully adjusted OR, 2.37; 95% CI, 0.42-19.86; P = .39) (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first neuropsychiatric and cognitive follow-up study of survivors of COVID-19 6 months after symptom onset, compared with prospectively evaluated control patients with similar disease severity and matched for age, sex, and ICU admission who were hospitalized for non-COVID-19 illness at the same hospital during the same time period. As to our cognitive primary outcome, we found lower total MoCA scores in survivors of COVID-19 compared with control patients, and we showed in a subgroup of survivors of COVID-19 that cognitive deficits from the time of hospital discharge were significantly associated with improvement 6 months later. As to our neuropsychiatric primary outcome, we found a comparable burden of neuropsychiatric diagnoses between cases and controls. Secondary exploratory outcomes of neuropsychiatric, cognitive, and neurologic symptoms, and diagnoses were similar between cases and controls, except for an association with increased frequency anosmia in COVID-19 in the fully adjusted model (although no longer significant after correcting for multiple testing).

Neuropsychiatric Complications

Overall, 20% of this COVID-19 population developed a new-onset psychiatric disorder, including depression in 11%, anxiety in 12%, and PTSD in 2%. More patients had depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms, such as low mood (18%), anxiety (15%), and distressing flashback memories from the admission (8%) than a definite ICD-10 diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or PTSD. This highlights the importance of distinguishing between reported symptoms and validated clusters of symptoms that define mental disorders. Previous studies have shown differing frequencies of psychiatric complications after COVID-19. Prospective follow-up questionnaire studies revealed depressive and/or anxiety symptoms in between 4% to 47% of patients,3,4,5,31,32 probably owing to variations in methods and case definitions. Prior prospective clinical studies without control groups investigating neuropsychiatric outcomes identified PTSD in 30%23 (30-120 days after COVID-19 onset) and depressive and anxiety symptoms in 30% to 33%21 of survivors of COVID-19 (although prevalence and not incidence). However, in survey-based studies with control groups, the burden of mental health complications among cases and controls was not significantly different,33,34,35 in agreement with our results. A recent study using EHR to investigate neuropsychiatric symptoms in hospitalized patients with and without COVID-19 found that mood and anxiety symptoms were even less common in patients with COVID-19,36 highlighting the need for matched controls.

Cognitive Deficits and Neurologic Complications

Cognitive deficits following COVID-19 improved markedly in patients who were tested at discharge30 and follow-up, and the cognitive status at follow-up was significantly different between cases and controls. Although the absolute difference in MoCA scores of 0.8 points between cases and controls at 6 months may seem small, a recent population sample showed this difference equals the cognitive effects of aging by 8 years for people in their 60s.37 Given the pandemic, this might translate to considerable cognitive impairment on a global scale.

Follow-up studies without control groups have revealed impaired cognition in 38% to 44%38,39 of COVID-19 survivors, based on a MOCA cutoff 26 or lower. A study31 with matched controls found a significantly higher prevalence of MoCA scores 26 or lower in survivors of COVID-19 compared with control patients, 16 of 58 (28%) vs 5 of 30 (17%), which is in line with our findings (29% vs 17%). Interestingly, 1 longitudinal cohort study with data before and after the beginning of the pandemic found a statistically significant decline in overall MoCA values in a population tested before and after mild COVID-19 compared with SARS-CoV-2–negative individuals.40

Survivors of COVID-19 commonly report cognitive impairment.41 In this COVID-19 population, 37 of 85 (44%) reported memory problems after 6 months, and self-reported memory problems still persisted in more than 10% by 8 months even after a mild infection.42 This raises concerns about longterm consequences, as subjective memory problems even without objective deficits is a risk factor for future cognitive impairment.43 This is further substantiated by a neuroimaging study that showed cortical brain atrophy after COVID-19 on magnetic resonance imaging before and after the beginning of the pandemic,44 indicating that parenchymal atrophy of entorhinal areas may be owed to direct viral central nervous system invasion. However, brain atrophy in frontal, temporal, and parietal regions is also observed following ICU admission for several causes45,46 and cognitive impairment is reported in more than 80% of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome at discharge from ICU, persisting in 36% at 6-month follow-up.47 Therefore, a more plausible explanation for cognitive impairment following ICU admission is hypoxic brain injury following respiratory failure47 and systemic inflammation,48 because most neurologic complications in patients with COVID-19 do not seem to be caused by central nervous system viral invasion.49,50 Furthermore, the overall neurologic complications in the studied population of survivors of COVID-19 were comparable with matched control patients and most frequently involved ICU-acquired gait difficulties.51

Strengths and Limitations

The strength is the prospective design and inclusion of a prospectively matched control group, with a similar disease severity, admitted to the same hospital, and experiencing the same degree of societal lockdown measures during the pandemic, thus affecting mental well-being of cases and control patients equally. Furthermore, all participants were examined by the same investigator, eliminating interobservational bias. As to the limitations, first, the case-control design of the study explores associations but not causality, and survivorship bias is a potential confounding effect owing to different rates of in-hospital mortality between cases and controls. Second, although we had a sufficient sample size to show significant contrast for the primary outcome of cognition, the study sample size was likely not sufficient to detect smaller differences for the neuropsychiatric outcome as differences in incidence were lower than expected (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement). Third, many patients experienced subjective cognitive difficulties after admission, which was not reflected by MoCA, possibly indicating that MoCA has a low sensitivity for minor cognitive deficits in nonneurodegenerative conditions, although MoCA did detect improvement of cognitive deficits from discharge to follow-up (Figure 1B), and between-group differences. Fourth, regarding the non-ICU sample, the patients with COVID-19 likely were more isolated on the ward than patients who did not have COVID-19 owing to infection control measures, which might have affected their mood; however, we believe this effect on 6-month outcome is likely minor. Additionally, different rates of haloperidol treatment for suspected delirium (33% in controls vs 17% in cases) during admission might have influenced mental health and cognition, but no change in outcome was observed in sensitivity analysis when adjusting for delirium (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Conclusions

In this 6-month prospective case-control follow-up study, cognitive impairment was more severe in survivors of COVID-19 who required hospitalization compared with matched survivors hospitalized for non–COVID-19 causes; however, the overall burden of neuropsychiatric and neurologic symptoms and diagnosis appeared similar. Further studies with larger samples are needed to investigate if smaller differences in neuropsychiatric profiles exist.

eAppendix 1. Power calculations for cognitive and neuropsychiatric primary outcomes

eAppendix 2. Assessment of delirium.

eTable 1. Items on structured interview on self-experienced neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms.

eTable 2. Overview of Intensive care unit admission-causes of the age- and sex-matched control group.

eTable 3. Extended demographics, past medical history, and admission characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 and non-COVID patients.

eTable 4. Laboratory, imaging, cerebrospinal fluid, and electrophysiological findings of hospitalized COVID-19 and non-COVID patients.

eTable 5. Age, sex, admission length and severity comparisons of included COVID-19 cases and matched controls in the study together with eligible cases and controls who declined participation.

eTable 6. Age, sex, admission length and severity comparisons of eligible COVID-19 cases and controls who declined participation.

eTable 7. MoCA sub scores for comparison of specific cognitive domains

eTable 8. Sensitivity analyses for cognitive primary outcome adjusted for education, delirium, disease severity, mechanical ventilation and comorbidities.

eTable 9. Sensitivity analyses for neuropsychiatric primary outcome adjusted for disease severity, mechanical ventilation and comorbidities.

eFigure 1. Flow of inclusion of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients hospitalized for COVID-19 (cases) and selection of non-COVID patients (controls), included for cognitive and neuropsychiatric evaluation after discharge. Controls were selected to match COVID-19 patients’ admission to the intensive-care-unit (ICU) and subsequently sex- and age (±7 years) matched 1:1.

eFigure 2. Age distribution by group showing that age is well balanced with perfect overlap in distribution.

eFigure 3. Visual examples of the evolution of the Clock Drawing Test (CDT) from 6 COVID-19 patients who were tested with the Montreal Cognitive

eReferences.

References

- 1.Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547-560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;8(2):130-140. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-Month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397(10270):220-232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spinicci M, Vellere I, Graziani L, et al. ; Careggi Post-acute COVID-19 Study Group . Clinical and laboratory follow-up after hospitalization for COVID-19 at an Italian tertiary care center. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(3):ofab049. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Borst B, Peters JB, Brink M, et al. Comprehensive health assessment 3 months after recovery from acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(5):e1089. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization; Regional office for Europe . Understanding and managing long COVID requires a patient-led approach. Accessed August 18, 2021. https://www.euro.who.int/en/media-centre/events/events/2021/02/virtual-press-briefing-on-covid-19-understanding-long-covid-post-covid-conditions/understanding-and-managing-long-covid-requires-a-patient-led-approach

- 7.Benros ME, Waltoft BL, Nordentoft M, et al. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for mood disorders: a nationwide study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(8):812-820. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benros ME, Nielsen PR, Nordentoft M, Eaton WW, Dalton SO, Mortensen PB. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for schizophrenia: a 30-year population-based register study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1303-1310. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith S, Rahman O. Post Intensive Care Syndrome. StatPearls; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883-892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rawal G, Yadav S, Kumar R. Post-intensive care syndrome: an overview. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5(2):90-92. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2016-0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. ; BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators . Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1306-1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Melle JP, de Jonge P, Spijkerman TA, et al. Prognostic association of depression following myocardial infarction with mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(6):814-822. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146294.82810.9c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan N, Chen Y, Xia Y, Dai J, Liu C. Inflammation-related biomarkers in major psychiatric disorders: a cross-disorder assessment of reproducibility and specificity in 43 meta-analyses. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):233. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0570-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girard TD, Self WH, Edwards KM, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):929-935. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4301-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. 6-Month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):416-427. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nersesjan V, Amiri M, Christensen HK, Benros ME, Kondziella D. Thirty-day mortality and morbidity in COVID-19 positive vs COVID-19 negative individuals and vs individuals tested for influenza A/B: a population-based study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:598272. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.598272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amin-Chowdhury Z, Ladhani SN. Causation or confounding: why controls are critical for characterizing long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27(7):1129-1130. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01402-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perlis RH, Ognyanova K, Santillana M, et al. Association of acute symptoms of COVID-19 and symptoms of depression in adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e213223. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol. 2021;93(2):1013-1022. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gramaglia C, Gambaro E, Bellan M, et al. ; NO-MORE COVID Group . Mid-term psychiatric outcomes of patients recovered from COVID-19 from an Italian cohort of hospitalized patients. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:667385. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.667385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miskowiak KW, Johnsen S, Sattler SM, et al. Cognitive impairments four months after COVID-19 hospital discharge: pattern, severity and association with illness variables. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;46:39-48. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janiri D, Carfì A, Kotzalidis GD, Bernabei R, Landi F, Sani G; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group . Posttraumatic stress disorder in patients after severe COVID-19 infection. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):567-569. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winkler P, Mohrova Z, Mlada K, et al. Prevalence of current mental disorders before and during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of repeated nationwide cross-sectional surveys. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;139:167-171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomann AE, Berres M, Goettel N, Steiner LA, Monsch AU. Enhanced diagnostic accuracy for neurocognitive disorders: a revised cut-off approach for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13195-020-00603-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6(2):65-70. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4615733 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nersesjan V, Amiri M, Lebech AM, et al. Central and peripheral nervous system complications of COVID-19: a prospective tertiary center cohort with 3-month follow-up. J Neurol. 2021;268(9):3086-3104. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10380-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raman B, Cassar MP, Tunnicliffe EM, et al. Medium-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on multiple vital organs, exercise capacity, cognition, quality of life and mental health, post-hospital discharge. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;31:100683. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sykes DL, Holdsworth L, Jawad N, Gunasekera P, Morice AH, Crooks MG. Post-COVID-19 symptom burden: what is long-COVID and how should we manage it? Lung. 2021;199(2):113-119. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00423-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Havervall S, Rosell A, Phillipson M, et al. Symptoms and functional impairment assessed 8 months after mild COVID-19 among health care workers. JAMA. 2021;325(19):2015-2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.5612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amin-Chowdhury Z, Harris RJ, Aiano F, et al. Characterising post-COVID syndrome more than 6 months after acute infection in adults; prospective longitudinal cohort study, England. medRxiv. Published online April 16, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.03.18.21253633 [DOI]

- 36.Castro VM, Rosand J, Giacino JT, McCoy TH, Perlis RH. Case-control study of neuropsychiatric symptoms following COVID-19 hospitalization in 2 academic health systems. medRxiv. Published online July 14, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.07.09.21252353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Borland E, Nägga K, Nilsson PM, Minthon L, Nilsson ED, Palmqvist S. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: normative data from a large Swedish population-based cohort. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;59(3):893-901. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morin L, Savale L, Pham T, et al. ; Writing Committee for the COMEBAC Study Group . Four-month clinical status of a cohort of patients after hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(15):1525-1534. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rousseau A-F, Minguet P, Colson C, et al. Post-intensive care syndrome after a critical COVID-19: cohort study from a Belgian follow-up clinic. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00910-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Del Brutto OH, Wu S, Mera RM, Costa AF, Recalde BY, Issa NP. Cognitive decline among individuals with history of mild symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a longitudinal prospective study nested to a population cohort. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(10):3245-3253. doi: 10.1111/ene.14775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oh ES, Vannorsdall TD, Parker AM. Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection and subjective memory problems. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2119335. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.19335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Søraas A, Bø R, Kalleberg KT, Støer NC, Ellingjord-Dale M, Landrø NI. Self-reported memory problems 8 months after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2118717. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.18717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitchell AJ, Beaumont H, Ferguson D, Yadegarfar M, Stubbs B. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(6):439-451. doi: 10.1111/acps.12336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Douaud G, Lee S, Alfaro-Almagro F, et al. Brain imaging before and after COVID-19 in UK Biobank. medRxiv. Published online August 18, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.06.11.21258690 [DOI]

- 45.Sprung J, Warner DO, Knopman DS, et al. Brain MRI after critical care admission: a longitudinal imaging study. J Crit Care. 2021;62:117-123. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hopkins RO, Gale SD, Weaver LK. Brain atrophy and cognitive impairment in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Brain Inj. 2006;20(3):263-271. doi: 10.1080/02699050500488199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang M, Gedansky A, Hassett CE, et al. Pathophysiology of brain injury and neurological outcome in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a scoping review of preclinical to clinical studies. Neurocrit Care. 2021;35(2):518-527. doi: 10.1007/s12028-021-01309-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parker AM, Sinha P, Needham DM. Biological mechanisms of cognitive and physical impairments after critical care: rethinking the inflammatory model? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(6):665-667. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202010-3896ED [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solomon T. Neurological infection with SARS-CoV-2—the story so far. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(2):65-66. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-00453-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bodro M, Compta Y, Sánchez-Valle R. Presentations and mechanisms of CNS disorders related to COVID-19. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation. 2021;8(1):1-9. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bellinghausen AL, LaBuzetta JN, Chu F, Novelli F, Rodelo AR, Owens RL. Lessons from an ICU recovery clinic: two cases of meralgia paresthetica after prone positioning to treat COVID-19-associated ARDS and modification of unit practices. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):580. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03289-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Power calculations for cognitive and neuropsychiatric primary outcomes

eAppendix 2. Assessment of delirium.

eTable 1. Items on structured interview on self-experienced neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms.

eTable 2. Overview of Intensive care unit admission-causes of the age- and sex-matched control group.

eTable 3. Extended demographics, past medical history, and admission characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 and non-COVID patients.

eTable 4. Laboratory, imaging, cerebrospinal fluid, and electrophysiological findings of hospitalized COVID-19 and non-COVID patients.

eTable 5. Age, sex, admission length and severity comparisons of included COVID-19 cases and matched controls in the study together with eligible cases and controls who declined participation.

eTable 6. Age, sex, admission length and severity comparisons of eligible COVID-19 cases and controls who declined participation.

eTable 7. MoCA sub scores for comparison of specific cognitive domains

eTable 8. Sensitivity analyses for cognitive primary outcome adjusted for education, delirium, disease severity, mechanical ventilation and comorbidities.

eTable 9. Sensitivity analyses for neuropsychiatric primary outcome adjusted for disease severity, mechanical ventilation and comorbidities.

eFigure 1. Flow of inclusion of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients hospitalized for COVID-19 (cases) and selection of non-COVID patients (controls), included for cognitive and neuropsychiatric evaluation after discharge. Controls were selected to match COVID-19 patients’ admission to the intensive-care-unit (ICU) and subsequently sex- and age (±7 years) matched 1:1.

eFigure 2. Age distribution by group showing that age is well balanced with perfect overlap in distribution.

eFigure 3. Visual examples of the evolution of the Clock Drawing Test (CDT) from 6 COVID-19 patients who were tested with the Montreal Cognitive

eReferences.