Key Points

Question

How do surgeons use shared decision-making when discussing high-stakes surgery with older adults?

Findings

In this secondary analysis of audio-recorded surgical consultations from a randomized clinical trial, a wide variation was found in individual performance of shared decision-making among surgeons; higher-scoring shared decision-making was associated with surgeons’ reluctance to operate.

Meaning

In this study, surgeons often used high-scoring shared decision-making efficiently but tended to use it more frequently when they were reluctant to operate.

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial examines the use of shared decision-making for major surgery among surgeons, patients, and families.

Abstract

Importance

Because major surgery carries significant risks for older adults with comorbid conditions, shared decision-making is recommended to ensure patients receive care consistent with their goals. However, it is unknown how often shared decision-making is used for these patients.

Objective

To describe the use of shared decision-making during discussions about major surgery with older adults.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study is a secondary analysis of conversations audio recorded during a randomized clinical trial of a question prompt list. Data were collected from June 1, 2016, to November 31, 2018, from 43 surgeons and 446 patients 60 years or older with at least 1 comorbidity at outpatient surgical clinics at 5 academic centers.

Interventions

Patients received a question prompt list brochure that contained questions they could ask a surgeon.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The 5-domain Observing Patient Involvement in Decision-making (OPTION5) score (range, 0-100, with higher scores indicating greater shared decision-making) was used to measure shared decision-making.

Results

A total of 378 surgical consultations were analyzed (mean [SD] patient age, 71.9 [7.2] years; 206 [55%] male; 312 [83%] White). The mean (SD) OPTION5 score was 34.7 (20.6) and was not affected by the intervention. The mean (SD) score in the group receiving the question prompt list was 36.7 (21.2); in the control group, the mean (SD) score was 32.9 (19.9) (effect estimate, 3.80; 95% CI, −0.30 to 8.00; P = .07). Individual surgeon use of shared decision-making varied greatly, with a lowest median score of 10 (IQR, 10-20) to a high of 65 (IQR, 55-80). Lower-performing surgeons had little variation in OPTION5 scores, whereas high-performing surgeons had wide variation. Use of shared decision-making increased when surgeons appeared reluctant to operate (effect estimate, 7.40; 95% CI, 2.60-12.20; P = .003). Although longer conversations were associated with slightly higher OPTION5 scores (effect estimate, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.52-0.88; P < .001), 57% of high-scoring transcripts were 26 minutes long or less. On multivariable analysis, patient age and gender, patient education, surgeon age, and surgeon gender were not significantly associated with OPTION5 scores.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that although shared decision-making is important to support the preferences of older adults considering major surgery, surgeon use of shared decision-making is highly variable. Skillful shared decision-making can be done in less than 30 minutes; however, surgeons who engage in high-scoring shared decision-making are more likely to do so when surgical intervention is less obviously beneficial for the patient.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02623335

Introduction

Although surgery has the potential to prolong life, improve function, and prevent disability, older adults face an increased risk of poor outcomes, including prolonged hospitalization, extended postacute care, and even death.1,2 Few patients desire to spend their last days in the hospital,3,4 and family members report lower-quality end-of-life care for loved ones who received intensive care or were hospitalized within 30 days of death.5 Given the possibility of adverse outcomes and the prevalence of life-limiting illness in older adults with surgical illness, shared decision-making is recommended for older adults facing the decision to undergo a major operation.6,7,8

Multiple strategies to promote shared decision-making exist,9,10,11,12,13 but there is little understanding of how shared decision-making is enacted in routine clinical practice. Contemporary models imagine a deliberative process14 in which the surgeon conveys the patient’s clinical situation and invites the patient and family member into a discussion about how the patient’s preferences relate to the available options.15 Although it is possible to measure performance of shared decision-making for research purposes,16,17 there are conflicting notions about how shared decision-making might be used as a tool to control health care expenditures.18,19,20,21 An empirical understanding of how shared decision-making is used clinically is vital to advancing the science of high-stakes decision-making. Moreover, precise accounting of performance might provide important insights for surgeons to develop skills to improve discussions of these important decisions with their patients.

Surgical consultations present an ideal setting for studying shared decision-making because of the gravity of the risks, consequential trade-offs, and the need for decision-making during outpatient visits. The objective of this study was to examine how surgeons use shared decision-making in preoperative consultation using a national cohort of older patients with comorbidities who were scheduled to discuss major surgery.

Methods

We conducted an exploratory secondary analysis of audio-recorded conversations between surgeons and older adults discussing major surgery. Data were collected from June 1, 2016, to November 31, 2018, as part of a multisite randomized clinical trial of a question prompt list (QPL) intervention, which had a nonsignificant effect on the number and type of questions asked by patients during the preoperative visit or on patient engagement.22 We obtained written informed consent from all participants. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Wisconsin, Madison; University of California, San Francisco; Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; and Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. The study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Study Participants

We enrolled 43 surgeons who routinely performed high-risk vascular (cardiac, neurosurgical, or peripheral) or oncologic (colorectal, hepatobiliary, urologic, gynecologic, neurosurgical, or head and neck) surgery and 446 patients who were 60 years or older with at least 1 comorbid condition who were scheduled to consult with a surgeon about a problem amenable to treatment with 1 of 227 high-risk operations.23 The primary study was designed with 40 surgeons, but we had the opportunity to evaluate 43 surgeons because 3 surgeons were enrolled to replace those who changed institutions during the study. The trial protocol24 and results22 were previously published, as was the patient allocation to intervention (eFigure in the Supplement).

We excluded patients and family members who lacked decision-making capacity or who were not fluent in English or Spanish. We also excluded 51 transcripts that did not discuss a high-risk operation, 8 transcripts in which technical errors lost a substantive part of the consultation, 6 transcripts that did not discuss an oncologic or vascular illness, 2 transcripts from overenrolled surgeons, and 1 transcript in which, post hoc, we found that the patient did not meet enrollment criteria.

Data Collection

We audio recorded 1 primary decision-making conversation between the surgeon and patient and all others present. For surgeons who typically meet with patients for consultation in more than 1 visit, we recorded the visit that the surgeon identified as the primary decision-making conversation. Recordings were transcribed verbatim. For consultations conducted in Spanish, audio recordings were translated and transcribed by a native speaker. We verified the patient’s treatment plan in the electronic medical record.

Outcomes

We used the 5-domain Observing Patient Involvement in Decision-making (OPTION5)16 scale to measure shared decision-making in each transcript. OPTION5 was developed for use in the primary care setting and was previously adapted to surgical consultations.25 This scale assesses 5 domains: (1) confirmation that there is a need for a decision and that alternative options exist, (2) support for deliberation and working together, (3) information about the pros and cons of each option, (4) preference elicitation, and (5) integration of patient preference with treatment choice. Each domain is scored independently on a scale of 0 to 4 (0, no effort; 1, minimal effort; 2, moderate effort; 3, skilled effort; and 4, exemplary effort). Domain scores are summed and rescaled so final scores range from 0 to 100.

Coders (N.D.B., A.B., C.Z., J.T., D.F., and M.L.S.) used a modified OPTION5 rubric annotated with scoring descriptions and exemplar phrases to ensure consistency (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement). We computed the intraclass correlation coefficient for a randomly selected sample of 30 transcripts and found that the intraclass correlation coefficient was lower than reported in the literature.26 As such, 2 of the blinded coders scored each transcript, and all discrepancies were adjudicated using group moderation. We used majority consensus to confirm the discussed operative treatment, the treatment decision at the end of the conversation, and instances when the surgeon expressed reluctance to operate (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the study sample and to describe intrasurgeon and intersurgeon variability in shared decision-making performance. Using a multivariable, linear mixed-effects model with a surgeon-level random effect, we explored the association between the continuous OPTION5 score and the following variables: conversation length (minutes), patient gender, patient age (years), patient educational level (college degree or higher vs some college or less), surgeon reluctance to operate, treatment plan (no surgery, may consider surgery, or surgery planned), surgical indication (vascular vs oncologic), surgeon gender, and surgeon age (years). Complete case analysis was used for the regression model. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with R statistical software, version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing),27 and figures were produced with the ggplot2 package.28

Results

We analyzed 378 surgical consultations (mean [SD] patient age, 71.9 [7.2] years; 206 [55%] male; 3 [1%] American Indian or Alaska Native, 10 [3%] Asian, 28 [7%] Black or African American, 312 [83%] White, 10 [3%] missing race or ethnicity, and 15 [4%] other race or ethnicity) (Table 1). All surgeons had at least 3 transcripts included in this study. Surgeons contributed a mean (SD) of 9 (4) transcripts, and 11 surgeons had more than 10 transcripts. Conversation length ranged from 3 to 81 minutes, with a mean (SD) length of 23.7 (12.0) minutes. On completion of the conversation, the plan was to operate for 231 patients (61%), to not operate for 40 patients (11%), and to consider operating in the future for 107 patients (28%). Surgeons expressed reluctance to operate in 91 conversations (24%). Nine surgeons, representing all subspecialities except for urology, did not express reluctance in any conversation.

Table 1. Patient and Surgeon Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Findingsa |

|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |

| No. of patients | 378 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 72 (7) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 206 (55) |

| Female | 172 (45) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3 (1) |

| Asian | 10 (3) |

| Black or African American | 28 (7) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0 |

| White | 312 (83) |

| Missing | 10 (3) |

| Other | 15 (4) |

| Language spoken | |

| English | 364 (96) |

| Spanish | 13 (3) |

| Receipt of QPL intervention | |

| QPL intervention | 185 (49) |

| Usual care | 193 (51) |

| Family present at initial consultation | 299 (79) |

| Educational level | |

| Some college or less | 233 (62) |

| College degree or higher | 145 (38) |

| Insurance | |

| Medicare and Medicare plus supplemental | 250 (66) |

| Any Medicaid | 28 (7) |

| Private insurance | 97 (26) |

| Surgical indication | |

| Oncologic | 306 (81) |

| Vascular | 72 (19) |

| Final treatment decision | |

| No surgery planned | 40 (11) |

| May consider surgeryb | 107 (28) |

| Surgery planned | 231 (61) |

| Surgeon reluctance to operate | |

| No reluctance | 287 (76) |

| Surgeon expressed reluctance to operate | 91 (24) |

| Audio length, mean (SD), min | 23.7 (12) |

| Surgeon characteristics | |

| No. of surgeons | 43 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46.1 (8) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 35 (81) |

| Female | 8 (19) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 18 (42) |

| Black or African American | 1 (2) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (2) |

| White | 22 (51) |

| Unknown or >1 race | 2 (5) |

| Time in practice, mean (SD), y | 20 (8) |

Abbreviation: QPL, question prompt list.

Data are presented as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

During group adjudication of the 5-domain Observing Patient Involvement in Decision-making scores, coders assessed the final treatment decision based on the content of the recorded consultation. The response “may consider surgery” was used to indicate consultations when surgery was discussed but not definitely planned (eg, awaiting additional workup or discussion with tumor board) or when surgery was being considered in the future.

OPTION5 scores ranged from 0 to 95, with a mean (SD) score of 34.7 (20.6). Domain scores were lowest for domain 2 (deliberation/team talk), with a mean (SD) score of 4.1 (5.5), and highest for domain 3 (pros and cons of treatment options), with a mean (SD) score of 12.3 (4.8) (eAppendix 3 in the Supplement). The QPL intervention had no effect on OPTION5 scores (mean [SD] score for QPL vs usual care, 36.7 [21.2] vs 32.9 [19.9]; effect estimate, 3.80; 95% CI, −0.30 to 8.00; P = .07).

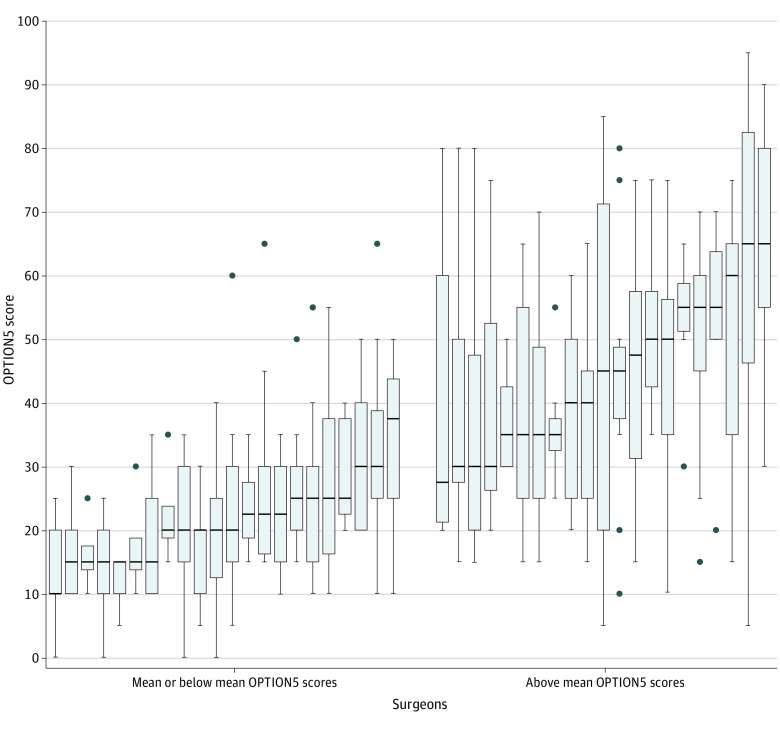

Between-surgeon OPTION5 scores were highly variable, ranging from a median of 10 (IQR, 10-20) to 65 (IQR, 55-80). Twenty-three surgeons used little shared decision-making, with mean OPTION5 scores at or below the overall mean, and 20 surgeons had mean OPTION5 scores above the overall mean (Figure 1). Lower-performing surgeons showed modest variation in OPTION5 scores across their consultations (median IQR, 13.13). In contrast, higher-performing surgeons exhibited wider variation in the use of shared decision-making, with most high-performing surgeons having at least 1 consultation with an OPTION5 score below the mean (median IQR, 23.75).

Figure 1. Observing Patient Involvement in Decision-making (OPTION5) Scale Scores of 43 Surgeons Ranked by Individual Median OPTION5 Distribution and Grouped by Mean and Below and Above Mean Performance.

The mean OPTION5 score was 34.7. The median IQR for the 23 low-performing surgeons was 13.13 compared with 23.75 for the 20 higher-performing surgeons. Error bars indicate IQRs; horizonal lines in the rectangles, means; and closed circles, outliers.

On bivariate analysis, higher OPTION5 scores were significantly associated with a nonoperative treatment plan or a plan to consider operating in the future compared with consultations in which the plan was to proceed with surgery (mean [SD] scores, 42.9 [22.4] vs 41.3 [20.4] vs 30.4 [19.2], respectively; P < .001) (Table 2). Higher OPTION5 scores were significantly associated with surgeons’ expressions of reluctance to operate vs no reluctance (mean [SD] scores, 40.4 [21.7] vs 33.0 [19.9]; P = .005). Length of consultation was also significantly associated with higher OPTION5 scores (effect estimate, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.53-0.89; P < .001). Increasing surgeon age was significantly associated with lower OPTION5 scores (effect estimate, −0.36; CI, −0.642 to −0.079; P = .01). No significant difference was found in OPTION5 scores for consultations in which the indication for treatment was a vascular vs oncologic problem (mean [SD] score, 37.9 [20.6] vs 34.1 [20.5]; P = .16). Higher OPTION5 scores were not significantly associated with patient age or gender, surgeon gender, or patient educational level.

Table 2. Bivariate Analysis of Patients, Surgeons, and Conversation Characteristics Associated With Shared Decision-making as Described by OPTION5 Scores.

| Characteristic | OPTION5 score, mean (SD) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Patient gender | ||

| Male | 35.2 (21.4) | .65 |

| Female | 34.3 (19.6) | |

| Patient educational level | ||

| Some college or less | 35.9 (20.7) | .18 |

| College degree or higher | 33.0 (20.4) | |

| Surgeon gender | ||

| Male | 34.7 (19.4) | .90 |

| Female | 35.2 (26.2) | |

| Intervention | ||

| QPL intervention | 36.7 (21.2) | .07 |

| Usual care | 32.9 (19.9) | |

| Surgical indication | ||

| Vascular | 37.9 (20.6) | .16 |

| Oncologic | 34.1 (20.5) | |

| Final treatment decision | ||

| No surgery planned | 42.9 (22.4) | <.001 |

| May consider surgerya | 41.3 (20.4) | |

| Surgery planned | 30.4 (19.2) | |

| Reluctance to operate | ||

| No reluctance | 33.0 (19.9) | .005 |

| Surgeon expressed reluctance to operate | 40.4 (21.7) |

Abbreviations: OPTION5, 5-domain Observing Patient Involvement in Decision-making scale; QPL, question prompt list.

During group adjudication of OPTION5 scores, coders assessed the final treatment decision based on the content of the recorded consultation. The response “may consider surgery” was used to indicate consultations when surgery was discussed but not definitely planned (eg, awaiting additional workup or discussion with tumor board) or when surgery was being considered in the future.

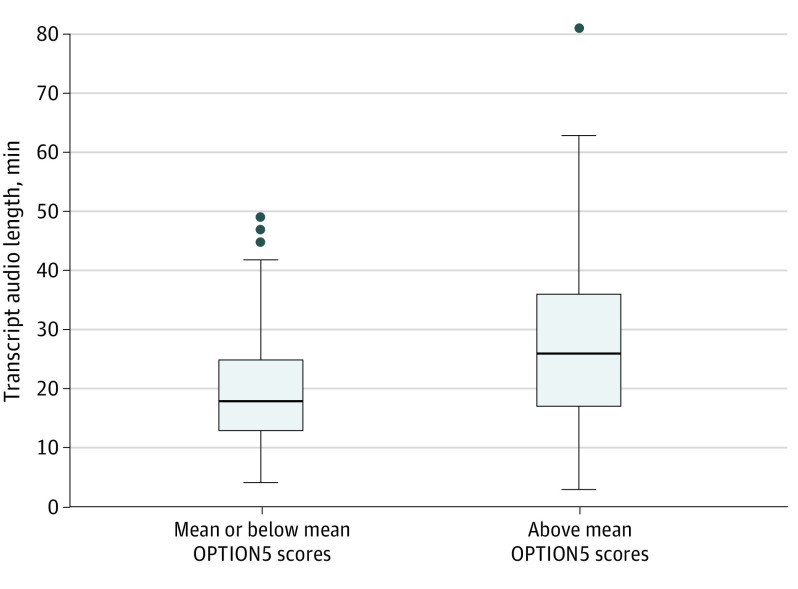

On multivariable analysis, a statistically significant association persisted between higher OPTION5 scores and surgeon expression of reluctance to operate (effect estimate, 5.8; 95% CI, 1.1-10.5; P = .02) (Table 3). After controlling for other factors, only future consideration of surgery had a significant association with OPTION5 scores (effect estimate, 6.97; CI, 0.34-13.45; P = .04). We also observed a significant association between OPTION5 scores and length of consultation (effect estimate, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.52-0.88; P < .001). Although this association is significant, it is clinically less meaningful. The median consultation length for OPTION5 scores above the mean was only 8 minutes more than conversations with OPTION5 scores below the mean (Figure 2). Moreover, 57% of OPTION5 scores above the mean were achieved in consultations of 26 minutes or less, and 31% were completed in 20 minutes or less.

Table 3. Multivariable Analysis of Patient and Surgeon Factors and Conversation Characteristics Related to OPTION5 Scores.

| Characteristic | Effect estimate (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Patient age, y | 0.22 (−0.04 to 0.46) | .009 |

| Patient gender | ||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Female | −0.06 (−3.68 to 3.45) | .97 |

| Patient educational level | ||

| Some college or less | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| College degree or higher | −2.67 (−6.16 to 0.71) | .13 |

| Surgeon age, y | −0.25 (−0.70 to 0.20) | .30 |

| Surgeon gender | ||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Female | −2.28 (−11.16 to 6.60) | .63 |

| Surgical indication | ||

| Vascular | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Oncologic | 0.16 (−8.46 to 8.81) | .97 |

| Final treatment decision | ||

| No surgery planned | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| May consider surgerya | 6.97 (0.34 to 13.45) | .04b |

| Surgery planned | −1.40 (−8.22 to 5.16) | .68 |

| Transcript audio length, min | 0.69 (0.52 to 0.88) | <.001b |

| Reluctance to operate | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Yes | 5.80 (1.09-10.52) | .02b |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OPTION5, 5-domain Observing Patient Involvement in Decision-making scale.

During group adjudication of OPTION5 scores, coders assessed the final treatment decision based on the content of the recorded consultation. The response “may consider surgery” was used to indicate consultations when surgery was discussed but not definitely planned (eg, awaiting additional workup or discussion with tumor board) or when surgery was being considered in the future.

Statistically significant at P < .05.

Figure 2. Comparison of Conversation Length for Transcripts Based on Observing Patient Involvement in Decision-making (OPTION5) Scale Score.

The mean conversation length for transcripts with mean or below vs above mean OPTION5 scores (20.2 vs 28.1 minutes, P < .001). Error bars indicate IQRs; horizonal lines in the rectangles, means; and closed circles, outliers.

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial of 378 surgical consultations with 43 surgeons and their patients, we found high variation in the use of shared decision-making during discussions of major surgery for older adults with comorbid conditions. Some surgeons did not routinely use shared decision-making, but even high-scoring surgeons used shared decision-making selectively. Use of shared decision-making varied with the treatment decision and the surgeon’s enthusiasm for surgery, whereby shared decision-making was used more frequently when surgeons expressed reluctance to operate. Although longer consultations were associated with higher levels of shared decision-making, most high-scoring conversations occurred in less than 30 minutes. In this cohort of older adults with comorbid conditions considering high-risk surgery, we theorized that choosing nonoperative management was a reasonable choice based on the patient’s goals and preferences. Although shared decision-making has been proposed as a tool to reduce overtreatment and unnecessary surgery,20 our results suggest that surgeons have harnessed it for different purposes—a strategy to guide patients when the surgeon is unlikely to take them to the operating room. These results are important for surgeons, policy makers, and patients.

For surgeons, shared decision-making is used regularly and often performed at high levels with relative efficiency during discussions about major surgery. Other studies26,29,30,31,32,33 of shared decision-making show that physicians other than surgeons often have lower OPTION5 scores during consultations with patients, with mean scores ranging from 9.78 to 26.5. We suspect surgeons’ superior scores are related to the requirements of informed consent for surgery, specifically disclosure of risks and alternatives, because the mandates of consent are procedurally enforced through requisite documentation to proceed to the operating room and legally enforced via malpractice jurisprudence. Although surgeons often raise concerns about limited time to engage patients in the decision-making process, our results show that even with short conversations, surgeons were able to achieve high levels of shared decision-making (eg, an OPTION5 score of 80 for a 13-minute conversation). Because patients may assume that surgical referral suggests that surgery is appropriate treatment, it is worth reconsidering whether shared decision-making (conceived as offering choices) or deliberate exposure of the surgeon’s well-considered opinion is the best way to address patients’ prior assumptions.

The question of why surgeons used higher-scoring shared decision-making when they appeared reluctant to operate is perplexing. Surgeons expressed reluctance when they believed their patient was not a surgical candidate because of comorbidities, risks, or advanced age or because their disease was not amenable to surgical treatment. Although surgeons explained that surgery was not in the patient’s best interest, consistently high scores in domain 3 suggest that, despite their reluctance, surgeons discussed the pros and cons of surgery and other treatments. It is possible that surgeons were using shared decision-making to honestly deliberate about what to do based on patient preferences because they were undecided, yet this seems unlikely given the cause of their reluctance (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement). Given expressions of concern about the utility of surgery, presenting surgery as if it were a reasonable option is akin to presenting a false choice34 or a “nonchoice” choice.35 Like discussions of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in actively dying patients, surgeons offered patients an operative option and proceeded to talk the patient out of that choice. A more transparent strategy with explicit expressions of reluctance might be preferred to hiding these concerns within a discussion of options and choices.

For policy makers, our data suggest that requirements to use decision aids are unlikely to improve aspects of shared decision-making that are commonly neglected. Decision aids facilitate knowledge transfer during decision-making conversations36 and reduce decisional conflict.37,38 In our cohort of surgeons, none of whom were using a decision aid conforming to the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration criteria, we found that surgeons achieved the highest mean scores on the OPTION5 domain measuring presentation of information about the pros and cons of each treatment option. Informing patients about risk is an important element of shared decision-making, and surgeons in our cohort did this well. Our data show that surgeons struggled with other aspects, including offering support for the patient’s role in the decision-making process (domain 2) and making a preference-concordant recommendation (domain 5). To effectively increase shared decision-making, policy makers should focus on strategies to improve elicitation of patient preferences and incorporate patients’ priorities within treatment recommendations rather than knowledge transfer.

For patients, these data suggest that participating in decision-making may be difficult when the surgeon has a strong conception that surgery is in the patient’s best interest. Surgeons might have feared presenting an opportunity for patients to make the “wrong” decision by presenting options and choices that appeared to them as unreasonable, believing the stakes were too high to consider anything other than surgery. This tendency mirrors previous work that showed that surgeons struggled to discuss nonoperative treatment choices in the absence of a stronger framework (eg, best case/worst case36) for shared decision-making.25 Because most patients in this study had an oncologic diagnosis, the goal of surgery was presumably to prolong life. However, some older adults with comorbid conditions might prefer to forgo life prolongation to maintain quality of life3,39 through pursuit of conservative treatment or comfort-focused care. Although we suspect most patients would find the nonoperative approach in these scenarios unreasonable, it is critical that surgeons explore patients’ priorities to confirm this is the case. Surgeons are often apprehensive to provide a direct response to the question, “What would you do?”40,41 given concerns about paternalism. Nonetheless, our data show that surgeons are not neutral about treatment decisions. We recommend patients ask, “What is the goal of surgery?” and “Are there other options?” and encourage surgeons to provide details about whether and how surgery might achieve the patient’s goals.

These results expose a deeper concern about the conceptualization of patient autonomy in medical decision-making. Presenting patients with choices for treatment decisions may seem an essential element of respecting patient autonomy, but as others have noted, “telling clinicians to ‘offer patients more choice’ may not achieve its objective.”42(p319) Clinicians, with their own conception of how best to care for patients, have a strong influence on the eventual treatment plan. Given surgeons’ expertise and experience, which patients and families value and desire, this is not surprising. What seems problematic is the use of choice-offering and choice-making to obfuscate the surgeon’s underlying assessment that surgery may not be the right strategy for the patient. Rather than conceiving of patient autonomy as an obligation to present a choice (and subsequently talk the patient out of that choice), surgeons may better show respect for patients by disclosing their reluctance and describing the source of this reluctance as it relates to the patient’s goals. This approach might provide a stronger strategy for deliberation about whether the surgeon’s reluctance is overly judgmental or failed to consider additional important outcomes for the patient.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has both strengths and limitations. The main strength is that data were collected in a multisite study that enrolled a large cohort of older adults facing a diverse array of major surgical decisions at academic centers where such operations are routinely performed. However, the study also has several limitations. Although we attempted to capture the primary decision-making conversation as identified by the enrolled surgeon, treatment decisions spanning multiple visits were not fully represented in our data. We were also limited by our ability to account for differences in case mix among surgeons, although we used a list of high-risk surgical procedures to ensure all enrolled patients faced the possibility of serious postoperative complications, which would necessitate use of preoperative shared decision-making. Despite our efforts to recruit a diverse cohort of participants, with input from underrepresented stakeholders on patient and family recruitment and enrollment, we had less diversity in our sample than desired. Language and cultural barriers likely present obstacles to shared decision-making, but we cannot fully describe and analyze these factors given the demographic characteristics of our cohort. For this analysis, surgeon reluctance was determined by coders with backgrounds in surgery and public health who likely identified reluctance that went unnoticed by patients and family. Finally, our measurement of shared decision-making relied on audio-recorded transcriptions that did not evaluate nonverbal communication.

Conclusions

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial found that surgeons often performed high-scoring shared decision-making but used it inconsistently when discussing major surgery with older adults with comorbid conditions. Because surgeons are more likely to engage in shared decision-making when surgical intervention is not clearly beneficial for the patient, it is unclear whether current conceptualizations of shared decision-making are adequate to support patients in deliberation about major surgery.

eFigure. CONSORT Diagram for Patients Enrolled in the Study

eAppendix 1. OPTION5 Rubric With Descriptions and Exemplar Phrases for Subdomain Scores Adapted for Surgical Consultations

eAppendix 2. Coding Taxonomy for Surgeon Reluctance (n = 91)

eAppendix 3. Mean and Median OPTION5 Subdomain Scores

References

- 1.Finlayson E, Fan Z, Birkmeyer JD. Outcomes in octogenarians undergoing high-risk cancer operation: a national study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(6):729-734. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwok AC, Semel ME, Lipsitz SR, et al. The intensity and variation of surgical care at the end of life: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378(9800):1408-1413. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61268-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, et al. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences? a study of the US Medicare population. Med Care. 2007;45(5):386-393. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000255248.79308.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, Gallagher PM, Fisher ES. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):695-701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0952-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315(3):284-292. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper Z, Courtwright A, Karlage A, Gawande A, Block S. Pitfalls in communication that lead to nonbeneficial emergency surgery in elderly patients with serious illness: description of the problem and elements of a solution. Ann Surg. 2014;260(6):949-957. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper Z, Koritsanszky LA, Cauley CE, et al. Recommendations for best communication practices to facilitate goal-concordant care for seriously ill older patients with emergency surgical conditions. Ann Surg. 2016;263(1):1-6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sokas C, Yeh IM, Coogan K, et al. Older adult perspectives on medical decision making and emergency general surgery: “it had to be done.” J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(5):948-954. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braddock CH III, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA. 1999;282(24):2313-2320. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681-692. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00221-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(5):651-661. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00145-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301-312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361-1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hargraves IG, Montori VM, Brito JP, et al. Purposeful SDM: a problem-based approach to caring for patients with shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(10):1786-1792. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992;267(16):2221-2226. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03480160079038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elwyn G, Tsulukidze M, Edwards A, Légaré F, Newcombe R. Using a ‘talk’ model of shared decision making to propose an observation-based measure: Observer OPTION 5 Item. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(2):265-271. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunneman M, Branda ME, Hargraves IG, et al. ; Shared Decision Making for Atrial Fibrillation (SDM4AFib) Trial Investigators . Assessment of shared decision-making for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(9):1215-1224. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elwyn G, Tilburt J, Montori V. The ethical imperative for shared decision-making. Eur J Pers Cent Healthc. 2013;1(1):129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumenthal-Barby J, Opel DJ, Dickert NW, et al. Potential unintended consequences of recent shared decision making policy initiatives. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(11):1876-1881. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.13978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weeks WB, Weinstein JN. Cost and outcomes information should be part of shared decision making. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(5):465-466. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarze ML, Buffington A, Tucholka JL, et al. Effectiveness of a question prompt list intervention for older patients considering major surgery: a multisite randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(1):6-13. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.3778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarze ML, Barnato AE, Rathouz PJ, et al. Development of a list of high-risk operations for patients 65 years and older. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(4):325-331. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor LJ, Rathouz PJ, Berlin A, et al. Navigating high-risk surgery: protocol for a multisite, stepped wedge, cluster-randomised trial of a question prompt list intervention to empower older adults to ask questions that inform treatment decisions. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e014002. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor LJ, Nabozny MJ, Steffens NM, et al. A framework to improve surgeon communication in high-stakes surgical decisions: best case/worst case. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):531-538. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barr PJ, O’Malley AJ, Tsulukidze M, Gionfriddo MR, Montori V, Elwyn G. The psychometric properties of Observer OPTION(5), an observer measure of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(8):970-976. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. Accessed December 30, 2021. http://www.R-project.org/

- 28.Wickham H. Ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag; 2016. Accessed December 30, 2021. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org

- 29.Goossens B, Sevenants A, Declercq A, Van Audenhove C. Shared decision-making in advance care planning for persons with dementia in nursing homes: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):381. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01797-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kölker M, Topp J, Elwyn G, Härter M, Scholl I. Psychometric properties of the German version of Observer OPTION5. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2891-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCabe R, Pavlickova H, Xanthopoulou P, Bass NJ, Livingston G, Dooley J. Patient and companion shared decision making and satisfaction with decisions about starting cholinesterase medication at dementia diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(5):711-718. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson JL, Storch D, Jackson W, Becher D, O’Malley PG. Direct-observation cohort study of shared decision making in a primary care clinic. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(6):756-765. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20936272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dillon EC, Stults CD, Wilson C, et al. An evaluation of two interventions to enhance patient-physician communication using the observer OPTION5 measure of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(10):1910-1917. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drought TS, Koenig BA. “Choice” in end-of-life decision making: researching fact or fiction? Gerontologist. 2002;42(spec No. 3):114-128. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nabozny MJ, Steffens NM, Schwarze ML. When do not resuscitate is a nonchoice choice: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1444-1445. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Connor AM, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Flood AB. Modifying unwarranted variations in health care: shared decision making using patient decision aids. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;(suppl variation):VAR63-72. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4(4):CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leinweber KA, Columbo JA, Kang R, Trooboff SW, Goodney PP. A review of decision aids for patients considering more than one type of invasive treatment. J Surg Res. 2019;235:350-366. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1061-1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minkoff H, Lyerly AD. “Doctor, what would you do?” Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(5):1137-1139. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a11bbb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caplan AL. Why autonomy needs help. J Med Ethics. 2014;40(5):301-302. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-100492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toerien M, Shaw R, Duncan R, Reuber M. Offering patients choices: a pilot study of interactions in the seizure clinic. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;20(2):312-320. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. CONSORT Diagram for Patients Enrolled in the Study

eAppendix 1. OPTION5 Rubric With Descriptions and Exemplar Phrases for Subdomain Scores Adapted for Surgical Consultations

eAppendix 2. Coding Taxonomy for Surgeon Reluctance (n = 91)

eAppendix 3. Mean and Median OPTION5 Subdomain Scores