Abstract

Background and aims

In recent years, Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) has been recognized as a mental health problem. Although research has found that social anxiety, motives, the preference for online social interactions (POSI), and metacognitions about online gaming are independent predictors of IGD, less is known about their relative contribution to IGD. The aim of the current study was to model the relationship between social anxiety, motives, POSI, metacognitions about online gaming, and IGD.

Methods

Five hundred and forty three Italian gamers who play more than 7 h a week (mean age = 23.9 years; SD = 6.15 years; 82.5% males) were included in the study. The pattern of relationships specified by the theoretical model was examined through path analysis.

Results

Results showed that social anxiety was directly associated with four motives (escape, coping, fantasy, and recreation), POSI, and positive and negative metacognitions about online gaming, and IGD. The Sobel test showed that negative metacognitions about online gaming played the strongest mediating role in the relationship between social anxiety and IGD followed by escape, POSI, and positive metacognitions. The model accounted for 54% of the variance for IGD.

Discussion and conclusions

Overall, our findings show that, along with motives and POSI, metacognitions about online gaming may play an important role in the association between social anxiety and IGD. The clinical and preventive implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: internet gaming disorder, metacognitions about online gaming, social anxiety, preference for online social interactions (POSI), motives

Introduction

In recent years, the recognition of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) as mental health problem by two prominent diagnostic systems of mental disorders (DSM-5 and ICD-11) has facilitated the proliferation of studies attempting to understand the phenomenon and its correlates (e.g., Chen & Chang, 2019; Pontes, Stavropoulos, & Griffiths, 2020). Multiple factors have been found to contribute to the development and maintenance of IGD, including individual characteristics (e.g., age, gender, psychological vulnerability, and comorbidity) as well as contextual factors (e.g., social influence processes) and game-related features (King & Delfabbro, 2018; Przybylski, Weinstein, & Murayama, 2017). Prominent researchers in the field (King & Delfabbro, 2018) have advocated more studies to be grounded in theoretically based models and investigating a wide range of psychological aspects together. The aim of the current study was to model the relationship between social anxiety, preference for online social interaction (POSI), motives for online gaming, metacognitions about online gaming, and IGD in a community sample of gamers.

IGD has been defined as “a disorder characterized by persistent gaming and functional impairment in multiple areas of life” (King & Delfabbro, 2018, p. 17). In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, APA, 2013), IGD was included as a condition on which future research is needed. In this context, IGD is detected when five or more out of the 9 criteria are met in a 12-month period (i.e., preoccupation; withdrawal; tolerance; loss of control; loss of nongaming interests; gaming despite harms; deception of others about gaming; gaming for escape or mood relief; conflict/interference due to gaming; Przybylski et al., 2017). More recently, in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; WHO, 2018) Gaming Disorder was defined as a persistent and recurrent participation in online or offline digital- and video-gaming in a 12-month period. Gaming Disorder is characterized by: (1) impairment in controlling gaming (e.g., frequency, duration); (2) increasing salience of gaming and preference for gaming over other activities; and (3) continuation of gaming despite negative consequences (i.e., significant impairment in daily life - family, school, and work). Features of IGD appeared to be mostly in line in the two classifications, both highlighting loss of control over gaming, persistent use of videogames despite harms, and significant impairment in daily life.

It has been shown that, although only a minority of gamers (around 1% of the population) can be classified with IGD following the DSM criteria (e.g., Rehbein, Kliem, Baier, Moble, & Petry, 2015), a further number could be at-risk to develop IGD meeting less criteria but experiencing significant distress due to gaming behavior (e.g., Müller et al., 2015). For this reason, and for the purposes of the current study, a continuum approach to IGD, rather than a categorical one, was employed in order to highlight the contributing factors influencing the risk of problematic gaming (Haagsma, Caplan, Peters, & Pieterse, 2013).

Social anxiety and POSI in online gaming

According to Davis' cognitive-behavioral model (2001) of pathological Internet use, psychological problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, and social anxiety) may constitute a distal antecedent of both generalized and specific problematic Internet use, including IGD. Among the several co-occurring psychopathology conditions (e.g., Brand, Young, Laier, Wölfling, & Potenza, 2016; Burleigh, Griffiths, Sumich, Stavropoulos, & Kuss, 2019; Laconi, Pirès, & Chabrol, 2017), social anxiety appears one of plausible risk factors in developing and maintaining IGD and needs to be ascertained. A recent review on this topic (González-Bueso et al., 2018) showed mixed results with one study highlighting the lack of association between online video game addiction and social anxiety (Van Rooij, Schoenmakers, Vermulst, Van den Eijnden, & Van de Mheen, 2011) while another study demonstrated a positive bidirectional association between online gaming and social anxiety (Gentile et al., 2011). Online gamers experiencing social anxiety symptoms are more likely than others to be ‘stuck’ on games, which provide an alternative to real life social interactions and allow for the avoidance of distress linked to face-to-face social interactions (e.g., Wei, Chen, Huang, & Bai, 2012). Specifically, as many online games involve social interactions, the virtual world of online games may serve as a safe place for gaining friends and establishing relationships for socially anxious gamers who value online communication as less risky and more effective than the face-to-face one (González-Bueso et al., 2018; Haagasma, Caplan, Peters, & Pieterse, 2013). In other words, those struggling with social anxiety may exert more control over their environment online. Accordingly, an application of Caplan's cognitive-behavioral model of problematic Internet use (Caplan, 2010; Haagasma et al., 2013) demonstrated that POSI plays a role in worsening the negative consequences of problematic gaming both directly and via mood regulation (Haagasma et al., 2013). Surprisingly, however, the literature about the link between social anxiety, POSI and IGD is scarce. It could be hypothesized that online gamers experiencing any distress due to social anxiety, along with loneliness, may be motivated by social needs to engage in gaming and/or may develop the tendency to prefer online interaction instead of communicating in person with others (Lemmens, Valkenburg, & Peter, 2011; Van Rooij et al., 2011), thus increasing the probability of incurring in IGD.

The next sections explain, in more detail, the rationale for testing a single model of IGD to include motives for online gaming and metacognitions about online gaming.

Motives for online gaming

Online gamers have different motives for gaming. Demetrovics and colleagues (2011) have classified individuals' online gaming motives into seven dimensions comprising escape, coping, skill development, social, competition, fantasy, and recreation motives. Escape motivation concerns the need of gaming in order to avoid real life problems and difficulties. Coping concerns the need to reduce stress, tension or aggression through gaming. Skill development involves improving the player's own coordination, concentration, and other skills. Social involves the need of gaming together with others and making friends. Competition concerns the defeating of others, and fantasy involves trying our new activities/identities in virtual game words which are not possible in everyday life. Finally, recreation refers to the need of gaming in order to have fun. Specific motives for gaming have frequently been related to IGD, especially escape, competition, and coping motives (Billieux et al., 2013; Demetrovics et al., 2011; Kuss, Louws, & Wiers, 2012; Laconi et al., 2017). For instance, escapism has been shown to have a strong association with IGD through the avoidance of real-life difficulties (e.g., Dauriat et al., 2011; Kuss et al., 2012; Kwon, Chung, & Lee, 2011). Other motives associated with IGD include fantasy and immersion into video game worlds (Ballabio et al., 2017; Kneer & Rieger, 2015), and achievement, advancement, and skill enhancement (Dauriat et al., 2011; Yee, 2006). Consistent with the theoretical backgrounds reviewed, we hypothesized that specific motives for gaming (especially escape) should predict IGD. Moreover, a broad and growing body of literature suggests that motives for gaming have been found to mediate the relationships between psychiatric impairments and IGD (Ballabio et al., 2017; Kiràly et al., 2015), loneliness and stress (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014; Laconi et al., 2017). However, there is a lack of studies exploring, in a single model, the association between social anxiety, motives and IGD.

Metacognitions in online gaming

Metacognitions refer to beliefs we hold about our thinking and how to control it (Wells, 2000). These beliefs are thought to drive and maintain forms of coping (e.g. rumination, worry, desire thinking, thought suppression) in response to negative cognitive-affective states which are likely to maintain distress. In the metacognitive model of psychopathology developed by Wells and Matthews (1994, 1996) psychological disturbance is purported to be principally linked to the appraisal of negative cognitive experiences (metacognitions) rather than their content. In this model positive metacognitions (“If I worry I will be prepared” or “If I use alcohol I will achieve clarity of mind”) drive the activation of forms of coping that inadvertently lead to the persistence and strengthening of negative cognitive experiences (Wells, 2000). Over time, individuals develop negative metacognitions “e.g. “My worry is uncontrollable” or “My thoughts about using alcohol control my mind”) which perpetuate distress and lock them into self-referent thinking, further escalating psychological distress. Over time, negative metacognitions become the key marker of psychological dysfunction.

In the first study investigating the presence of metacognitions about online gaming, Spada and Caselli (2017) identified two sub-type of problematic metacognitions in Study 1: (i) positive metacognitions about online gaming; and (ii) negative metacognitions about online gaming. The first sub-type refers to beliefs that online gaming is helpful in controlling negative thoughts and feelings. That is, online gaming may be perceived as a self-regulatory activity aimed at achieving a degree of mental control and driven by beliefs such as “online gaming distracts my mind from my problems” (Spada & Caselli, 2017). Negative metacognitions refer to the uncontrollability of cognitive-affective experiences associated with online gaming such as “once I start online gaming it is difficult to stop” and the dangers of online gaming such as “thoughts about gaming interfere with my functioning”. In Study 2, authors also proposed the further sub-type distinction between negative metacognitions (i) about uncontrollability of thoughts related to online gaming and (ii) the dangers of online gaming on cognitive functioning. These metacognitions are considered the most problematic as they are likely to be, at least partially, responsible for the perpetuation of gaming behavior along with the perception of losing control over thinking and behaving in the online world (Marino & Spada, 2017; Spada, Caselli, Nikčević, & Wells, 2015). Both positive and negative metacognitions about online gaming have been found to correlate with weekly online gaming hours, with negative metacognitions an independent predictor of online gaming beyond negative affect and problematic Internet use. In line with the above research, we hypothesized that that metacognitions about online gaming should be associated with IGD. Moreover, different types of metacognitive processes have been found to be associated with social anxiety (for a review see Gkika, Wittkowski, & Wells, 2018). Thus, it is hypothesized that social anxiety should be associated with metacognitions about online gaming.

Aims

In this study we aimed to examine the relationships between social anxiety, POSI, motives, metacognitions about online gaming, and IGD by testing the hypothesized model in a community sample of online gamers (see Figure 1). Davis' model proposed that psychological vulnerability (such as social anxiety) may lead users to develop and activate a range of maladaptive cognitions about the (offline vs. online) self and the world, as well as dysfunctional thinking styles, thus incurring in problematic behaviors such as online gaming (Davis, 2001; Marino & Spada, 2017). Therefore, drawing from the cognitive-behavioral model (Caplan, 2010; Davis, 2001; Haagasma et al., 2013), POSI is included in the proposed conceptual model as a dysfunctional cognition about the online world that can be activated by symptoms of social anxiety and can, thus, worsen the levels of IGD (e.g., Lemmens et al., 2011). Similarly, in line with previous studies (e.g., Ballabio et al., 2017; Kiràly et al., 2015), gamers experiencing any distress (such as distress due to social anxiety) might be motivated to engage in online gaming by a range of other specific motives, thus being at higher risk to incurring in IGD. Finally, drawing from the metacognitive tenet (Spada & Caselli, 2017; Spada et al., 2015; Wells, 2000), it is expected that beliefs about gaming-related thoughts and online gaming as cognitive control strategy (i.e. positive metacognitions about the usefulness of online gaming and negative metacognitions about uncontrollability and dangers of online gaming) may serve as a further cognitive self-regulating factor in explaining the association between social anxiety and IGD.

Fig. 1.

Proposed theoretical model

To summarize, it was hypothesized that social anxiety may serve as an emotional trigger linked to IGD, both directly (e.g., González-Bueso et al., 2018) and via the activation of different types of dysfunctional cognitions and beliefs (i.e., POSI, metacognitions; Davis, 2001) and motives (Király et al., 2015) which would be in turn associated with IGD (see above). Therefore, considering these variables together may allow for a better understanding of how certain psychological factors (e.g., social anxiety) put individuals at risk for gaming disorder (Brand et al., 2016).

Methods

Participants and procedure

An online questionnaire was used to collect data from June 1 to October 15, 2017. The link to the questionnaire was promoted by means of advertisements shared in thematic social network groups and gaming forums. All participants received information about the study and gave their online consent before starting the survey. Anonymity of the participants was guaranteed (no personal data or Internet Protocol address was collected). No compensation was given for participating in the study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) being over 18 years; and (ii) being able to complete the questionnaire in Italian. A total of 699 participants responded to the questionnaire and they were aged between 18 and 61 years (mean age = 23.97 years, SD = 6.14 years; 82.5% males). Questionnaires including more than 80% of missing data (n = 94) were excluded. Moreover, for the purpose of the current study, those reporting to game less than 1 hour per day (n = 62) were also excluded. Therefore, the analyses were run on a final sample of 543 online gamers (mean age = 23.89 years, SD = 6.15 years; 84.7% males). Participants reported to play online for a mean of 25.09 hours per week (SD = 16.43 hours). With regard to game genre, 32.8% of the participants preferred role playing games (MMO-RPG, e.g. World of Warcraft, Star Wars: Ultima Online, Guild Wars); 27.6% indicated massively multiplayer online games (MOBA, e.g., League of Legends, Dota 2, Heroes of Newerth); 15.8% preferred first person shooting games (MMO-FPS, e.g., PlanetSide 2, Dust 514); whereas the remaining indicated real-time strategy games (MMO-RTS, es. Age Of Empires Online, Clash of Clans, Legend World, Dawn of Gods) and social games (MMO-SG, e.g., World War II Online, The Sims online, War Thunder, Second Life). This study was part of a larger research project on online gaming, and other data not related to the current study are presented elsewhere (see Canale et al., 2019 for other details).

Measures

Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD)

The Italian version of the IGD Scale – Short Form (IGDS9-SF; Monacis, Palo, Griffiths, & Sinatra, 2016; original English version by Pontes & Griffiths, 2015) was used to assess the severity of IGD and its detrimental effects over a 12-month period. The scale comprises nine IGD symptoms as described in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). The 9 items are rated on a 5-point scale (1= “never” to 5 = “very often”). The Cronbach's alpha for the scale in the present study was 0.84 (95% CI 0.81–0.86). Responses were averaged to obtain a synthetic measure, where higher scores representing higher IGD levels.

Social anxiety

The Italian version of the Social Phobia Inventory (I-SPIN; Gori et al., 2013; original English version of the SPIN by Connor et al. 2000; further validation by Carleton et al., 2010) was used to assess social anxiety in terms of fear (e.g., fear of criticism, of talking to strangers), avoidance (e.g., avoidance of parties, of being the centre of attention, etc.), and authority problems (e.g., avoidance of talking to authority, etc.). The scale consists of 17 items rated on a 5-point scale (1 = “not at all” to 5 = “always”). Participants were asked to rate the extent to which each item reflected their experience over the last 12 months. The Cronbach's alpha for the scale in the present study was 0.91 (95% CI 0.90–0.92). Items were averaged to obtain a total score with higher scores representing higher levels of social anxiety.

Preference for Online Social Interactions (POSI)

The POSI subscale of the Italian version of the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 (GPIUS2; Fioravanti, Primi, & Casale, 2013; original English version by Caplan, 2010) was used to assess the POSIs. The subscale comprises 3 items (e.g., “Online social interaction is more comfortable for me than face-to-face interaction”). Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed with each of item on a 8-point scale (from 1 = “definitely disagree” to 8 = “definitely agree”). The Cronbach's alpha for the scale in the present study was 0.91 (95% CI 0.89–0.92). Items were averaged to obtain a total score with higher scores representing higher levels of POSI.

Motives

The Motives for Online Gaming Questionnaire (MOGQ; Demetrovics et al., 2011) was used to assess a range of motives for online gaming. Items were translated from English to Italian by three independent psychologists and back translated in English by one bilingual researcher expert in the field. Participants were asked to rate the frequency of each of the 27 items over the last 12 months on a 5-point scale (from 1 = “never” to 5 = “almost always/always”). The scale comprised seven motivational dimensions: (i) social (4 items; e.g., “…because gaming gives me company”; α = 0.71 (95% CI 0.83–0.87)), (ii) escape (4 items; e.g., “…because gaming helps me escape reality”; α = 0.88 (95% CI 0.86–0.89)), (iii) competition (4 items; e.g., “…because it is good to feel that I am better than others”; α = 0.83 (95% CI 0.81–0.85)), (iv) skill development (4 items; e.g., “…because it improves my coordination skills”; α = 0.89 (95% CI 0.88–0.91)), (v) coping (4 items; e.g., “…because gaming helps me get into a better mood”; α = 0.70 (95% CI 0.65–0.74)), (vi) fantasy (4 items; e.g., “…because I can do things that I am unable to do or I am not allowed to do in real life”; α = 0.86 (95% CI 0.84–0.88)), and (vii) recreation (3 items; e.g., “…because it is entertaining”; α = 0.79 (95% CI 0.76–0.82)). Items were averaged to obtain seven separate scores for each motivational dimension with higher scores representing higher levels of each motive. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using DWLS estimator (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996) to test for the construct validity of the measure. The CFA confirmed an adequate fit between the seven-factor model and the data: χ2(27) = 713.14, P < 0.001; CFI = 0.97; NNFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.051, 90% CI [0.046, 0.056]. All the standardized loadings were significant at the P < 0.001 level (mean loading for each dimension: social = 0.60; escape = 0.81; competition = 0.74; skill development = 0.83; coping = 0.60; fantasy = 0.78; recreation = 0.75) thus showing item convergent validity (Anderson & Gerbin, 1988). The Italian version of the scale has been already validated by Ballabio and colleagues (2017) but it was not yet available at the time of data collection.

Metacognitions

The Italian Metacognitions about Online Gaming Scale (MOGS; Spada & Caselli, 2017) was used to assess (i) “positive metacognitions about online gaming” (P-MOG; 6 items; e.g., “Online gaming helps me to control my negative thoughts”), and (ii) “negative metacognitions about online gaming” (N-MOG; 6 items; e.g., “I have no control over how much time I play”). This two-factor structure of the scale was preferred to the three-factor structure to seek parsimony. Indeed, the two negative dimensions of the scale (“Negative metacognitions about uncontrollability of online gaming” and “Negative metacognitions about the dangers of online gaming”) are often collapsed because, taken together, they tap the same construct of negative metacognitions (e.g., Dragan, 2015). Participants were asked to rate their agreement to each item on a 4-point scale (from 1 = “do not agree” to 4 = “agree very much”). The Cronbach's alpha for the positive and negative subscales in the present study were 0.85 (95% CI 0.83–0.87) and 0.82 (95% CI 0.79–0.84), respectively. Items were averaged to obtain two separate scores for positive and negative metacognitions. Higher scores represent higher levels of metacognitions about online gaming.

Weekly online gaming hours

Participants were asked to indicate how many hours per week they usually spend gaming on computers, consoles, and/or other gaming platforms (e.g., handheld devices). Weekly hours have been assessed in several previous studies (e.g., Beard & Wickham, 2016; Canale et al., 2019).

Statistical analyses

First, bivariate correlation analyses were conducted in order to test the associations between the variables included in the study. Second, the pattern of relationships specified by our proposed theoretical model (Figure 1) was examined through path analysis. The package Lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) of the software R (R Development Core Team 2013) and a single observed score for each construct included in the model were used. Specifically, the covariance matrix of the observed variable was analyzed with robust maximum likelihood method estimator (MLR; Satorra & Bentler, 1994) and the Sobel test (also known as the product of coefficients approach; Baron & Kenny, 1986; Hayes, 2009) was used to test for mediation. R2 of each endogenous variable and the Total Coefficient of Determination (TCD; Bollen, 1989; Jӧreskog & Sӧ;rbom, 1996) were considered in order to evaluate the goodness of fit of the model. In the tested model, IGD was the dependent variable, social anxiety was the independent variable, whereas POSI, seven motives, and two metacognitions about online gaming were the mediators, and weekly online gaming hours, age and gender were included as control variables (Figure 1).

Ethics

The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Padova approved the study. All subjects were informed about the study and all provided informed consent prior to the online survey, which took approximately 25 min to complete. This study did not involve human and/or animal experimentation.

Results

Means, standard deviations are presented in Table 1, along with range, skewness and kurtosis; whereas bivariate correlations between the variables included in the study are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, range, for the study variables

| M (SD) | Range (Min–Max) | Skewness (SE) | Kurtosis (SE) | |

| Social Anxiety | 2.03 (0.76) | 1–5 | 0.99 (0.105) | 0.61 (209) |

| IGDa | 1.94 (0.73) | 1–5 | 1.10 (0.105) | 0.92 (209) |

| POSIb | 3.22 (1.93) | 1–8 | 0.74 (0.105) | −0.26 (209) |

| Socialc | 2.69 (0.91) | 1–5 | 0.24 (0.105) | −0.50 (209) |

| Escapec | 2.45 (1.16) | 1–5 | 0.57 (0.105) | −0.79 (209) |

| Competitionc | 2.73 (1.06) | 1–5 | 0.38 (0.105) | −0.74 (209) |

| Copingc | 2.97 (0.93) | 1–5 | −0.02 (0.105) | −0.62 (209) |

| Skillc | 2.97 (1.14) | 1–5 | −0.04 (0.105) | −1.07 (209) |

| Fantasyc | 2.41 (1.21) | 1–5 | 0.61 (0.105) | −0.71 (209) |

| Recreationc | 4.51 (0.66) | 1–5 | −0.67 (0.105) | 3.01 (209) |

| Positive /Metacognitions | 2.78 (0.70) | 1–4 | −0.20 (0.105) | −0.57 (209) |

| Negative Metacognitions | 1.52 (0.57) | 1–4 | 1.56 (0.105) | 2.48 (209) |

| Weekly hours | 25.09 (16.43) | 7–112 | 1.77 (0.105) | 4.15 (209) |

Notes: N = 543.

aInternet Gaming Disorder.

bPreference for Online Social Interactions.

cMotives for online gaming.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among the study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| 1. Social Anxiety | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2. IGDa | 0.36*** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 3. POSIb | 0.52*** | 0.33*** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 4. Socialc | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.14** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 5. Escapec | 0.30*** | 0.41*** | 0.29*** | 0.32*** | 1 | |||||||||

| 6. Competitionc | 0.04 | 0.23*** | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 1 | ||||||||

| 7. Copingc | 0.15*** | 0.23*** | 0.19*** | 0.33*** | 0.53*** | 0.22*** | 1 | |||||||

| 8. Skillc | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.13** | 0.34*** | 0.23*** | 0.28*** | 0.38*** | 1 | ||||||

| 9. Fantasyc | 0.20*** | 0.20*** | 0.20*** | 0.33*** | 0.50*** | 0.10* | 0.41*** | 0.35*** | 1 | |||||

| 10. Recreationc | −0.09* | −0.21*** | −0.06 | 0.23*** | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.20*** | 0.14** | 0.16*** | 1 | ||||

| 11. Positive Metacognitions | 0.14*** | 0.26*** | 0.18*** | 0.31*** | 0.49*** | 0.05 | 0.52*** | 0.25*** | 0.39*** | 0.12** | 1 | |||

| 12. Negative Metacognitions | 0.24*** | 0.64*** | 0.17*** | 0.02 | 0.18*** | 0.21*** | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.12** | −0.21*** | 0.08 | 1 | ||

| 13. Weekly hours | 0.18*** | 0.27*** | 0.30*** | 0.14*** | 0.16*** | 0.10* | 0.08 | 0.14** | 0.13** | −0.09** | 0.09* | 0.19*** | 1 | |

| 14. Gender | 0.14*** | −0.03 | 0.09* | 0.09* | 0.10* | −0.23*** | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.002 | −0.03 | 1 |

| 15. Age | −0.20*** | −0.14** | −0.15*** | −0.05 | −0.15*** | −0.16*** | −0.08 | −0.21*** | −0.10* | 0.09* | −0.11* | 0.001 | −0.14*** | 0.05 |

Notes: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; N = 543; Gender= 1: M, 2: F.

aInternet Gaming Disorder.

bPreference for Online Social Interactions.

cMotives for online gaming.

As expected, most of the study variables were associated with each other. In particular, social anxiety was positively associated with IGD and POSI. Moreover, the strongest positive correlations were found between negative metacognitions about online gaming, escape motive, and IGD.

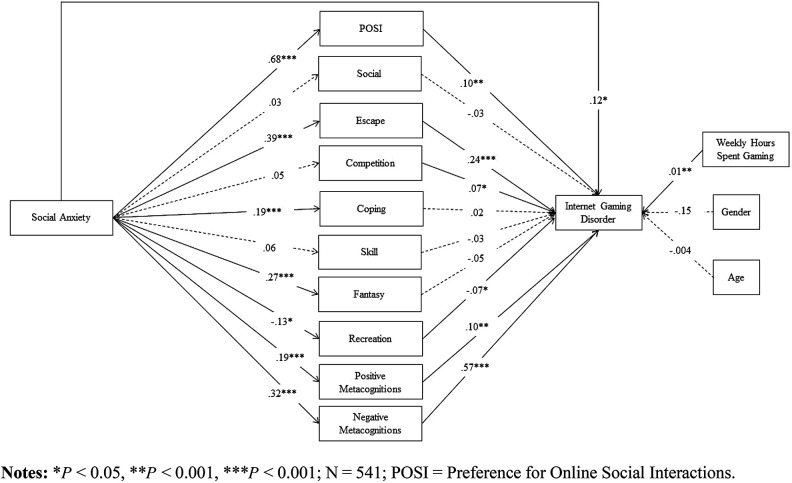

The theoretical model was tested including all the variables of interest. In this model, several path coefficients were significant at least at the P <0.05 level, as shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Results of the path analytical model

Specifically, social anxiety was directly associated with IGD (though weakly), whereas it was strongly and positively associated with POSI. With regard to motives, social anxiety positively correlated with escape, coping and fantasy and negatively with recreation. Moreover, positive and direct associations were found between social anxiety and both positive and negative metacognitions about online gaming. Furthermore, negative metacognitions about online gaming were strongly associated with IGD, along with escape. Weekly online gaming hours appeared to be weakly associated with IGD, whereas age and gender were not significantly associated with the outcome.

With regard to indirect relationships, results of the Sobel test supported the mediating role of four mediators between social anxiety and IGD, namely POSI (β = 0.046, SE =0.016, z = 2.833, P =0.005), escape (β = 0.064, SE =0.012, z = 5.276, P <0.001), positive metacognitions (β = 0.013, SE =0.006, z = 2.417, P = 0.016), and negative metacognitions (β = 0.127, SE =0.023, z = 5.565, P <0.001) about online gaming.

With regard to model fit, the model accounted for 54% of the variance for the outcome variable (IGD), and 26% of the variance for one mediator (i.e. POSI) variable. Substantial lower variance was observed for the other mediators (e.g., 9% for escape and 6% for negative metacognitions, 2% for coping and positive metacognitions). Finally, the total amount of variance explained by the model (Total Coefficient of Determination, TCD = 0.40) indicated a good fit to the observed data. Indeed, this TCD corresponds to a correlation of r = 0.63, which can be considered a medium to large effect size (Cohen, 1988).

Discussion

This study explored the role of social anxiety in predicting levels of IGD in a community sample of gamers, both directly and indirectly via different types of dysfunctional beliefs and cognitions (i.e., POSI, motives and metacognitions).

Though relatively small, the significant direct association between social anxiety and IGD suggests that symptoms of social anxiety (like fear of talking to strangers and avoidance of social situations) may represent a risk factor for IGD. In line with this view, it has been shown that gamers may tend to avoid the inadequacy felt in the offline world by creating a different and more confident online social self (Allison, von Wahlde, Shockley, & Gabbard, 2006; Carlisle, Neukrug, Pribesh, & Krahwinkel, 2019). However, as the virtual world is progressively perceived as safer, the devotion to the online world and activities increases and may result in the escalation of some IGD symptoms, such as loss of nongaming interest and/or jeopardized daily life activities (school, job, family), especially for gamers holding a poor offline self-concept (e.g., Dieter et al., 2015). These arguments have been also supported by researchers who described the “social experience” of gaming as unique and crucial in the explanation of IGD (Carlisle et al., 2019, p. 108).

With regard to indirect social-related paths, results from the path analysis showed that POSI is a significant mediator in the relation between social anxiety and IGD; whereas the social motive (for example, gaming because it provides company or because gamers can get to know new people) is not significantly associated with social anxiety or IGD. From this view, the present findings add to the extant literature suggesting that gamers are often driven by the satisfaction of social needs (e.g., Graham & Gosling, 2013; Trepte, Reinecke, & Juechems, 2012), and by highlighting that the problematic aspect of the social motive to play games may lie in maladaptive cognitions about the POSIs rather than on a general compensation for offline loneliness and companion seeking in the context of social anxiety among gamers (Haagasma et al., 2013; Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). In addition, past researchers have found that social motives do not generally predict IGD, but that social motives are predictive of more positive outcomes of online gaming (e.g., Cole & Griffiths, 2007; Yang & Liu, 2017). The second mediator variable in the present study was escape motive. This has also been reported in the gaming literature to mediate the relationship between psychiatric symptoms and problematic gaming (Király et al., 2015). According to the self-medication theory (Khantzian, 1987), it is possible that playing games to escape everyday difficulties is a coping strategy through which online gamers try to compensate for their social anxiety and reach emotional stability. However, the present finding did find an association between social anxiety and coping and fantasy motives, and these motives have not emerged as significant risk factors for IGD. Conversely, the negative association between social anxiety and recreation motive might suggest that the more gamers show symptoms of social anxiety the less they are motivated to play for recreational purposes, which, in turn, is commonly considered among the less risky motives to play games (Király et al., 2015).

With regards to metacognitions about online gaming, both positive (β = 0.013) and negative (β = 0.127) metacognitions played a significant mediating role between social anxiety and IGD but a difference in the effect sizes of the two mediations emerged showing a substantial weaker indirect effect via positive metacognitions. It could be that anxious feelings and thoughts related to deficient social skills may activate positive metacognitions that gaming is helpful to distract the gamer's mind from distress or to control such disturbing thoughts, thus bringing to play as a means of cognitive-affective self-regulation (Billieux et al., 2020; Marino & Spada, 2017). The effects in relation to negative metacognitions about online gaming were greater in magnitude relative to the effects in relation to the positive ones. It might be that common beliefs in social anxiety about the self as ‘inadequate’ and ‘powerless’ may be proximal to the activation of metacognitions such as not being able to control involvement in gaming which, in turn, may lead individuals to be stuck in gaming as a means of controlling the detrimental effects of gaming itself despite its negative consequences (e.g., King & Delfabbro, 2014; Spada & Caselli, 2017). Spada and Caselli (2017) have argued that negative metacognitions exacerbate negative internal states to the point of compelling gamers to remain engaged in gaming as a form of coping. From this viewpoint, holding metacognitions about online gaming appears to play a key role in developing and maintaining the perception of impaired control and the negative consequences of IGD-related symptoms. Taken together, the role of negative metacognitions and escape motive might suggest that the association between social anxiety and IGD is, at least partially, based on attempts to control and avoid negative internal states of social anxiety (e.g., Perales et al., 2020). In other words, it could be that a thought (responsible for social anxiety and its persistence) such as the fear to appear inadequate is uncontrollable and is avoided by escaping from reality through gaming. At the same time, metacognitions about the uncontrollability of thoughts hamper the possibility of monitoring thinking, thus limited efforts are made to regulate thoughts about gaming and social inadequacy (e.g., Gkika et al., 2018). Finally, the immersive and rewarding nature of online games contributes in increasing the perseveration of (problematic) gaming.

As a note, it should be acknowledged that there is a partial overlap between the definitions of coping and escape motives and positive metacognitions (especially items related to mood modification) in that both capture what drive people to engage in gaming. However, positive metacognitions mainly refer to beliefs about the usefulness of online gaming to control thinking, that is as a cognitive self-regulation tool (e.g., to manage negative thoughts or stop worry), whereas, slightly differently, coping motive refer to general stress reduction and escape motive focuses on a broader concept of escaping from reality. In other words, motives may be essentially considered cognitions about gaming whereas positive metacognitions about online gaming are beliefs about gaming-related thoughts. Therefore, being cognitions about cognitions, they are part of the metacognitive domain. As an example, the partial overlap and the differences between expectancies and metacognitions have already been shown in previous studies on drinking and smoking behaviors (Nikčević et al., 2017; Spada, Moneta, & Wells, 2007) in which it is shown that positive metacognitions differ from alcohol and smoking expectancies in that positive metacognitions clearly identify the “usefulness of alcohol as a cognitive self-regulation tool” (Spada et al., 2007, p. 572).

Moreover, some items of the negative metacognitions subscale may resemble IGD criteria, especially regarding the failing to reduce or stop gaming. However, negative metacognitions measure the beliefs about the uncontrollability and danger of gaming-related thoughts with an emphasis on mental control (i.e., lack of executive control over gaming) and mental impairments (i.e. impact on cognitive functioning) rather than loss of control per se and general negative consequences for daily life. In other words, negative metacognitions specifically tap into beliefs about the uncontrollability of thoughts about gaming and beliefs about the danger for gamer's mind in terms of loss of control over mind, and impaired cognitive functioning.

From this viewpoint, it should be acknowledged that positive metacognitions are strictly linked to other types of motives and expectations while being separate concepts, as well as that negative metacognitions constitute, to a certain extent, a symptom of addictive behaviors, like IGD. However, deriving from the metacognitive tenet, metacognitions about online gaming provide a conceptual framework for IGD which can be immediately translated into practice. Indeed, metacognitive therapy for addictive behaviors has been found effective for a wide range of problematic behaviors (for a recent review see Normann & Morina, 2018).

Limitations

Several limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. The sample was a convenient self-selected sample of gamers recruited online. Moreover, this is a non-clinical sample. Future studies should replicate these findings using randomly selected participants with a clinical diagnosis of social anxiety. Importantly, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow to draw causal inference. However, the tested model is theoretically-based on cognitive-behavioral (Davis, 2001) and metacognitive models (Spada et al., 2015; Wells, 2000); and it has been suggested that path analyses might be suggestive of the directions of the associations (e.g., Bullock, Harlow, & Mulaik, 1994). Future experimental research is needed to examine the possible mediating effect of different types of beliefs in worsening the levels of IGD. Moreover, it has been shown that IGD may worsen the levels of social anxiety due to progressive gamers' isolation and deprivation of social contacts (González-Bueso et al., 2018). From this viewpoint, further longitudinal studies are warranted. Moreover, a short review of the literature about cognitions and metacognitions about gaming (Marino & Spada, 2017) proposed a classification of cognitions and metacognitions based on the crucial theoretical difference between cognitive and metacognitive frameworks confirming that there are a number of other relevant cognitions related to IGD (King & Delfabbro, 2014). Thus, it should be noted that this study is solely focused on the relative contribution of few maladaptive cognitions (i.e. POSI and certain motives) and metacognitions and future studies including a wider range of cognitions are needed. Lastly, although motives for online gaming have already received attention in the field, including gaming motives in the model allowed to control the effects of other possible predictors of IGD (namely POSI and metacognitions about online gaming), for well-established predictors of IGD (such as motives). Indeed, POSI and metacognitions have been highlighted over and beyond the known role of motives. This could be relevant from a theoretical and practical perspective.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, findings from this study have important implications in that a wide range of maladaptive cognitions (POSI, escape) and metacognitions emerged as potential mediators in the relationship between social anxiety and IGD. This study adds to the literature as it includes a “wider range of psychological concepts and health-related variables in connection to IGD” (King & Delfabbro, 2018, p. 13) and suggests possible theoretically-based mechanisms linking psychological vulnerabilities (i.e. social anxiety) to problematic online behaviors (i.e. IGD). Specifically, taken together in a single model different types of beliefs and psychological characteristics may help in isolating the most relevant variables involved in IGD. It follows that the elucidated dysfunctional cognitions (POSI) and control-related mechanisms (escape and metacognitions) may become part of the focus of clinical interventions and preventive programs targeting gamers with symptoms of social anxiety and IGD (e.g., Perales et al., 2020). From this viewpoint, cognitive-behavioral therapy (e.g., King et al., 2017) and metacognitive therapy (Spada et al., 2015) appear as tenable approaches in tackling IGD.

Funding sources

No financial support was received for this study.

Authors' contribution

CM, NC, AV and MMS are responsible for the study concept and design. CM performed analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NC and LS supervised the statistical analysis and contribute to the interpretation of data. GC and MS performed study supervision. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Claudia Marino, Email: claudia.marino@unipd.it.

Natale Canale, Email: natale.canale@unipd.it.

Alessio Vieno, Email: alessio.vieno@unipd.it.

Gabriele Caselli, Email: gabriele.caselli@gmail.com.

Luca Scacchi, Email: l.scacchi@univda.it.

Marcantonio M. Spada, Email: spadam@lsbu.ac.uk.

References

- Allison, S. E., von Wahlde, L., Shockley, T., & Gabbard, G. O. (2006). The development of the self in the era of the internet and role-playing fantasy games. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 381–385. 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (fifth ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two – Step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Ballabio, M., Griffiths, M. D., Urbán, R., Quartiroli, A., Demetrovics, Z., & Király, O. (2017). Do gaming motives mediate between psychiatric symptoms and problematic gaming? An empirical survey study. Addiction Research and Theory, 25, 397–408. 10.1080/16066359.2017.1305360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard, C. L., & Wickham, R. E. (2016). Gaming-contingent self-worth, gaming motivation, and internet gaming disorder. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 507–515. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux, J., Potenza, M. N., Maurage, P., Brevers, D., Brand, M., & King, D. L. (2020). Cognitive factors associated with gaming disorder. In Cognition and addiction (pp. 221–230). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Billieux, J., Van der Linden, M., Achab, S., Khazaal, Y., Paraskevopoulos, L., Zullino, D., et al. (2013). Why do you play World of Warcraft? An in-depth exploration of self-reported motivations to play online and in-game behaviours in the virtual world of Azeroth. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 103–109. 10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252–266. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, H. E., Harlow, L. L., & Mulaik, S. A. (1994). Causation issues in structural equation modeling research. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 1(3), 253–267. 10.1080/10705519409539977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh, T. L., Griffiths, M. D., Sumich, A., Stavropoulos, V., & Kuss, D. J. (2019). A systematic review of the co-occurrence of Gaming Disorder and other potentially addictive behaviors. Current Addiction Reports, 6(4), 383–401. 10.1007/s40429-019-00279-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canale, N., Marino, C., Griffiths, M. D., Scacchi, L., Monaci, M. G., & Vieno, A. (2019). The association between problematic online gaming and perceived stress: The moderating effect of psychological resilience. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(1), 174–180. 10.1556/2006.8.2019.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, S. E. (2010). Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 1089–1097. 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, R. N., Collimore, K. C., Asmundson, G. J., McCabe, R. E., Rowa, K., & Antony, M. M. (2010). SPINning factors: Factor analytic evaluation of the Social Phobia Inventory in clinical and nonclinical undergraduate samples. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(1), 94–101. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle, K. L., Neukrug, E., Pribesh, S., & Krahwinkel, J. (2019). Personality, motivation, and Internet gaming disorder: Conceptualizing the gamer. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 40(2), 107–122. 10.1002/jaoc.12069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Y., & Chang, S. L. (2019). Moderating effects of information-oriented versus escapism-oriented motivations on the relationship between psychological well-being and problematic use of video game live-streaming services. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(3), 564–573. 10.1556/2006.8.2019.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for behavioral science (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2007). Social interactions in massively multiplayer online role-playing gamers. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 10(4), 575–583. 10.1089/cpb.2007.9988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor, K. M., Davidson, J. R., Churchill, L. E., Sherwood, A., Weisler, R. H., & Foa, E. (2000). Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN): New self-rating scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 176(4), 379–386. 10.1192/bjp.176.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauriat, F. Z., Zermatten, A., Billieux, J., Thorens, G., Bondolfi, G., Zullino, D., et al. (2011). Motivations to play specifically predict excessive involvement in massively multiplayer online role-playing games: Evidence from an online survey. European Addiction Research, 17(4), 185–189. 10.1159/000326070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R. A. (2001). A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 17(2), 187–195. 10.1016/S0747-5632(00. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demetrovics, Z., Urbán, R., Nagygyörgy, K., Farkas, J., Zilahy, D., Mervó, B., et al. (2011). Why do you play? The development of the motives for online gaming questionnaire (MOGQ). Behavior Research Methods, 43, 814–825. 10.3758/s13428-011-0091-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieter, J., Hill, H., Sell, M., Reinhard, I., Vollstädt-Klein, S., Kiefer, F., et al. (2015). Avatar’s neurobiological traces in the self-concept of massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) addicts. Behavioral Neuroscience, 129(1), 8. 10.1002/jaoc.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragan, M. (2015). Difficulties in emotion regulation and problem drinking in young women: The mediating effect of metacognitions about alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors, 48, 30-35. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioravanti, G., Primi, C., & Casale, S. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the generalized problematic internet use scale 2 in an Italian sample. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16, 761–766. 10.1089/cyber.2012.0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, D. A., Choo, H., Liau, A., Sim, T., Li, D., Fung, D., et al. (2011). Pathological video game use among youths: A two-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics, 127(2), e319–e329. 10.1542/peds.2010-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkika, S., Wittkowski, A., & Wells, A. (2018). Social cognition and metacognition in social anxiety: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(1), 10–30. 10.1002/cpp.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Bueso, V., Santamaría, J. J., Fernández, D., Merino, L., Montero, E., & Ribas, J. (2018). Association between internet gaming disorder or pathological video-game use and comorbid psychopathology: A comprehensive review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(4), 668. 10.3390/ijerph15040668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori, A., Giannini, M., Socci, S., Luca, M., Dewey, D. E., Schuldberg, D., et al. (2013). Assessing social anxiety disorder: Psychometric properties of the Italian social phobia inventory (I-SPIN). Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 10(1), 37. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, L. T., & Gosling, S. D. (2013). Personality profiles associated with different motivations for playing World of Warcraft. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16, 189–193. 10.1089/cyber.2012.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haagsma, M. C., Caplan, S. E., Peters, O., & Pieterse, M. E. (2013). A cognitive-behavioral model of problematic online gaming in adolescents aged 12–22 years. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 202–209. 10.1016/j.chb.2012.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. 10.1080/03637750903310360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jӧreskog, K. G. & Sӧrbom, D. (1996). LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian, E. J. (1987). The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: Focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. In The cocaine crisis (pp. 65–74). Boston, MA: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2014). The cognitive psychology of Internet gaming disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(4), 298–308. 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, D., & Delfabbro, P. (2018). Internet gaming disorder: Theory, assessment, treatment, and prevention. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Wu, A. M., Doh, Y. Y., Kuss, D. J., & Pallesen, S., et al. (2017). Treatment of Internet gaming disorder: An international systematic review and CONSORT evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 54, 123–133. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Király, O., Urbán, R., Griffiths, M. D., Ágoston, C., Nagygyörgy, K., Kökönyei, G., et al. (2015). The mediating effect of gaming motivation between psychiatric symptoms and problematic online gaming: An online survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(4), e88. 10.2196/jmir.3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneer, J., & Rieger, D. (2015). Problematic game play: The diagnostic value of playing motives, passion, and playing time in men. Behavioral Sciences, 5(2), 203–213. 10.3390/bs5020203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss, D. J., Louws, J., & Wiers, R. W. (2012). Online gaming addiction? Motives predict addictive play behaviorin massively multiplayer online role-playing games. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(9), 480–485. 10.1089/cyber.2012.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, J. H., Chung, C. S., & Lee, J. (2011). The effects of escape from self and interpersonal relationship on the pathological use of Internet games. Community Mental Health Journal, 47(1), 113–121. 10.1007/s10597-009-9236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laconi, S., Pirès, S., & Chabrol, H. (2017). Internet gaming disorder, motives, game genres and psychopathology. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 652–659. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens, J. S., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2011). Psychosocial causes and consequences of pathological gaming. Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 144–152. 10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marino, C. & Spada, M. M. (2017). Dysfunctional cognitions in online gaming and internet gaming disorder: A narrative review and new classification. Current Addiction Reports, 4(3), 308–316. 10.1007/s40429-017-0160-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monacis, L., Palo, V. D., Griffiths, M. D., & Sinatra, M. (2016). Validation of the internet gaming disorder scale–short-form (IGDS9-SF) in an Italian-speaking sample. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(4), 683–690. 10.1556/2006.5.2016.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, K. W., Janikian, M., Dreier, M., Wölfling, K., Beutel, M. E., Tzavara, C., et al. (2015). Regular gaming behavior and internet gaming disorder in European adolescents: Results from a cross-national representative survey of prevalence, predictors, and psychopathological correlates. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(5), 565–574. 10.1007/s00787-014-0611-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikčević, A. V., Alma, L., Marino, C., Kolubinski, D., Yılmaz-Samancı, A. E., Caselli, G., et al. (2017). Modelling the contribution of negative affect, outcome expectancies and metacognitions to cigarette use and nicotine dependence. Addictive Behaviors, 74, 82–89. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normann, N., & Morina, N. (2018). The efficacy of metacognitive therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2211. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perales, J. C., King, D. L., Navas, J. F., Schimmenti, A., Sescousse, G., Starcevic, V., et al. (2020). Learning to lose control: A process-based account of behavioral addiction. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 108, 771–780. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Measuring DSM-5 Internet gaming disorder: Development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 137–143. 10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pontes, H. M., Stavropoulos, V., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Emerging insights on internet gaming disorder: Conceptual and measurement issues. Addictive Behaviors Reports (in press). 10.1016/j.abrep.2019.100242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybylski, A. K., Weinstein, N., & Murayama, K. (2017). Internet gaming disorder: Investigating the clinical relevance of a new phenomenon. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(3), 230–236. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16020224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [computer software manual]. Vienna, Austria Available from http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Rehbein, F., Kliem, S., Baier, D., Mößle, T., & Petry, N. M. (2015). Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in German adolescents: Diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM-5 criteria in a state-wide representative sample. Addiction, 110(5), 842–851. 10.1111/add.12849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In Von Eye A. & Clogg C. C. (Eds.), Latent variable analysis. Applications for developmental research (pp. 399–419). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Spada, M. M. & Caselli, G. (2017). The metacognitions about online gaming scale: Development and psychometric properties. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 281–286. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada, M. M., Caselli, G., Nikčević, A. V. & Wells, A. (2015). Metacognition in addictive behaviors. Addictive Behaviors, 44, 9–15. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada, M. M., Moneta, G. B., & Wells, A. (2007). The relative contribution of metacognitive beliefs and expectancies to drinking behaviour. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 42(6), 567–574. 10.1093/alcalc/agm055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepte, S., Reinecke, L., & Juechems, K. (2012). The social side of gaming: How playing online computer games creates online and offline social support. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 832–839. 10.1016/j.chb.2011.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooij, A. J., Schoenmakers, T. M., Vermulst, A. A., Van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., & Van de Mheen, D. (2011). Online video game addiction: Identification of addicted adolescent gamers. Addiction, 106, 205–212. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H. T., Chen, M. H., Huang, P. C., & Bai, Y. M. (2012). The association between online gaming, social phobia, and depression: An internet survey. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 92. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells, A. (2000). Emotional disorders and metacognition: Innovative cognitive therapy. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, A., and Matthews, G. (1994). Attention and emotion: A Clinical Perspective. Hove: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, A., and Matthews, G. (1996). Modelling cognition in emotional disorder: The S-REF model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 881–888. 10.1016/S0005-7967(96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. C., & Liu, D. (2017). Motives matter: Motives for playing Pokémon Go and implications for well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(1), 52–57. 10.1089/cyber.2016.0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee, N. (2006). Motivations for play in online games. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 9(6), 772–775. 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]