Abstract

Background.

Patients with chronic kidney disease have reduced cardiorespiratory fitness levels that contribute to mortality.

Objectives.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of aerobic exercise on cardiopulmonary function in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Methods.

A total of 36 patients (mean [SD] estimated glomerular filtration rate 44 [12] ml/min/1.73m2) were randomly allocated to an exercise training or a control arm over 12 weeks. The exercise training group performed aerobic exercise for 45 min 3 times/week at 65% to 80% heart rate reserve. The control group received routine care. Outcome measures were assessed at baseline and 12 weeks. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing was performed on a cycle ergometer with workload increased by 15 W/min. A battery of physical function tests were administered. Habitual physical activity levels were recorded via accelerometry. Data are mean (SD).

Results.

Exercise training improved VO2peak as compared with the control group (exercise: 17.89 [4.18] vs 19.98 [5.49]; control: 18.29 [6.49] vs 17.36 [5.99] ml/kg/min; p<0.01). Relative O2 pulse improved following exercise, suggestive of improved left ventricular function (exercise: 0.12 [0.02] vs 0.14 [0.04]; control: 0.14 [0.05] vs 0.14 [0.04] ml/beat/kg; p=0.03). Ventilation perfusion mismatching (VE/VCO2) remained evident after exercise (exercise: 32 [5] vs 33 [5]; control: 32 [7] vs 34 [5] AU; p=0.1). Exercise did not affect the ventilatory cost of oxygen uptake (VE/VO2; exercise: 40 [7] vs 42 [8]; control: 3 [7] vs 41 [8] AU; p=0.5) and had no effect on autonomic function assessed by maximal and recovery heart rates. We found no changes in physical function or habitual physical activity levels.

Conclusions.

Cardiopulmonary adaptations appeared to be attenuated in patients with chronic kidney disease and were not fully restored to levels observed in healthy individuals. Improvements in exercise capacity did not confer benefits to physical function. Interventions coupled with exercise may be required to enhance adaptations in chronic kidney disease.

Performed according to CONSORT guidelines; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02050035.

Keywords: renal insufficiency, chronic, exercise, cardiorespiratory fitness, physical function performance

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a rapidly expanding public health problem affecting 1 in 7 adults in the United States (1). Cardiorespiratory fitness levels are substantially reduced in CKD patients and decline linearly with the progression of renal dysfunction (2, 3). Subsequent reductions in physical function are consistently reported throughout the spectrum of CKD (4). These reductions in cardiorespiratory fitness and physical function are noteworthy as they independently predict quality of life, hospitalization and mortality (5–8).

Moreover, reductions in cardiorespiratory fitness exacerbate the substantially high cardiovascular disease (CVD) burden reported in this patient population. In this respect, peak oxygen consumption levels (VO2peak) are associated with arterial stiffness, left ventricular afterload and function and overall CVD risk in non-dialysis patients (9). In addition, we previously demonstrated that cardiopulmonary abnormalities revealed by cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPX) precede the development of overt CVD in stage 3 to 4 CKD (2). Therefore, interventions aimed at improving cardiorespiratory fitness are of utmost importance for quality of life, comorbidity and mortality in this patient population. Furthermore, interventions that target subclinical cardiopulmonary abnormalities may have a significant preventative impact on the development of CKD-related CVD.

Exercise training is a non-pharmacological intervention that is a powerful stimulus for improving cardiorespiratory fitness in patient populations. Improvements in VO2peak after aerobic exercise have previously been reported in numerous CKD studies (10). However, most of these investigations were implemented in the dialysis cohort, with only a handful of interventions carried out with non-dialysis patients. Furthermore, aside from VO2peak there is a lack of evidence on the effects of exercise training on additional indices of cardiopulmonary function obtained from CPX that provide valuable prognostic information (11). To date, there are no known studies that have investigated the effect of aerobic exercise on cardiopulmonary function before the development of overt CVD.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of moderate-to-vigorous intensity, supervised aerobic exercise on cardiopulmonary function and physical function in non-dialysis patients with stage 3 to 5 CKD but without overt CVD. We hypothesized that aerobic exercise would improve the subclinical cardiopulmonary abnormalities observed in these patients and that these improvements would translate to beneficial increases in physical function.

Methods

Design

The study used a randomized controlled design (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02050035). Participants were randomly allocated to an exercise training (EXT) or a control (CON) arm in a 1:1 manner according to a computer-generated blocked sequence stratified by sex (randomization.com) that was developed by a biostatistician. Group allocation was performed by DK.

Participants

Ethical approval was provided by the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board. All procedures met the guidelines set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were recruited during local nephrology outpatient clinics between 2013 and 2017 in the state of Delaware. All participants provided written informed consent. Participant eligibility was assessed based on a medical history and blood and urine analysis. Eligible patients had stage 3 to 5 CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] ≤ 60 ml/min/1.73m2). Patients were excluded if they had CVD; uncontrolled hypertension; current cancer, lung or liver disease; peripheral vascular disease; currently receiving immunosuppressant, antiretroviral, hormone replacement or renal replacement therapy; pregnancy; hemoglobin level < 11 g/dL; tobacco use; unable to walk without assistance; absolute contraindications to exercise testing or if unable to provide informed consent. Patients with CVD history were excluded as we aimed to study cardiopulmonary function as it precedes the development of overt CVD.

Intervention

Respective EXT and CON interventions were performed as previously described. Briefly, EXT patients completed 12 weeks of supervised aerobic exercise 3 times per week at the University of Delaware. Participants commenced exercise as tolerated with the duration and intensity of each exercise session progressively increased to 45 min at 60% to 85% heart rate reserve (HRR) and/or a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) 12 to 16. CON patients received routine care, which involved no changes to their current standard care.

Outcomes

Outcome measures were assessed at baseline and after 12 weeks at the University of Delaware during a CPX testing visit and a separate physical-function testing visit. Participants were instructed to avoid caffeine, alcohol and exercise for 24 hr before testing. For safety reasons, participants were instructed to take their routine medications as normal for both visits.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing was performed as previously described (2). Body mass was assessed with an electronic scale (Total Body Composition Analyzer, Tanita, Tokyo). Symptom-limited, maximal-effort graded exercise tests were performed on an upright electro-magnetic braked cycle ergometer (Corival, Lode, the Netherlands). Cycling resistance was increased by 15 W/min while maintaining a cadence above 60 rpm until volitional fatigue. Two patients (EXT, n =1; CON, n=1) completed their exercise tests on the treadmill according to the modified Bruce protocol. Twelve-lead electrocardiography (Case, GE, USA) was performed at rest, throughout exercise and during recovery. Blood pressure (Tango M2, SunTech, NC) and RPE were recorded at rest and every 2 min throughout exercise and recovery. Oxygen uptake (VO2, standard temperature and pressure dry [STPD]), carbon dioxide production (VCO2, STPD), minute ventilation (VE, body temperature pressure saturated) and expired carbon dioxide pressure (PECO2, STPD) were acquired by breath-by-breath analysis with an automated gas analyzer (TrueOne 2400, Parvo Medics, UT) and averaged over 10-sec intervals. The ventilatory threshold was determined according to time-course plots of VE, VO2 and VCO2. The respiratory exchange ratio (RER) was calculated as the VCO2/VO2 ratio. The VE/VCO2 and VE/VO2 slopes during exercise were calculated by least-squares linear regression. Relative O2 pulse was calculated as absolute VO2 per heart beat per kg body weight. Oxygen uptake efficiency slopes (OUES) were derived from the relationship between VO2 and the log transformation of VE (VO2 = a logVE + b), where a is the OUES. Heart rate recovery was calculated as the difference between maximal heart rate achieved and heart rate 1 min into recovery and expressed as a percentage.

Physical function

Maximal grip strength of both hands was measured with a handgrip dynamometer (Jamar Plus, Patterson Medical, MN). Three, 5-sec isometric contractions were recorded and the highest value was reported. Functional aerobic capacity was assessed with the 2-min walk distance test (National Institutes of Health [NIH] Toolbox). For this test, participants were instructed to walk briskly, covering as much distance as possible over the 2-min period. Gait speed was assessed with the 4-m gait speed test (NIH Toolbox), with participants instructed to walk at their normal walking speed. The 2-min walk test and gait speed were timed manually and participants used a standing start for both tests. Lower-body physical function was assessed with the 30-sec sit-to-stand test (14).

Habitual physical activity

Habitual physical activity levels were measured over a 7-day period by accelerometry (wGT3x, Actigraph, FL). Participants were instructed to wear the accelerometer at the dominant hip continuously over 7 days and complete their routine daily activities as usual. Activity data were not collected during holidays or vacations. Participants were also asked to keep a simultaneous activity diary that included documenting if they forgot to wear the activity monitor. Daily data were excluded if the participant did not wear the activity monitor. From previous CKD literature, a minimum of 5 complete days of activity monitoring were required to be included in the analyses. The vector magnitude, a raw count that includes frequency and intensity of physical activity, was expressed as a daily average.

Statistical analysis

As this study aimed to address the efficacy of aerobic exercise training to improve cardiorespiratory fitness, data were analyzed per protocol. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS v26 (IBM, NY). Changes in outcome measures over time were compared between groups with mixed-model (group × time) ANOVAs. Subsequent post-hoc analyses were performed following a statistically significant omnibus interaction. Post-hoc analyses included independent samples t test for between-group comparisons and paired samples t test for within-group comparisons. Cohen’s d interaction effect sizes were calculated as ((EXT Follow-up - EXT Baseline / Group Baseline standard deviation) – (CON Follow-up - CON Baseline / Group Baseline standard deviation)) / 2. Participant characteristics at baseline were compared by chi-square or Student’s t test. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. All data are presented as mean (SD).

Results

Participants

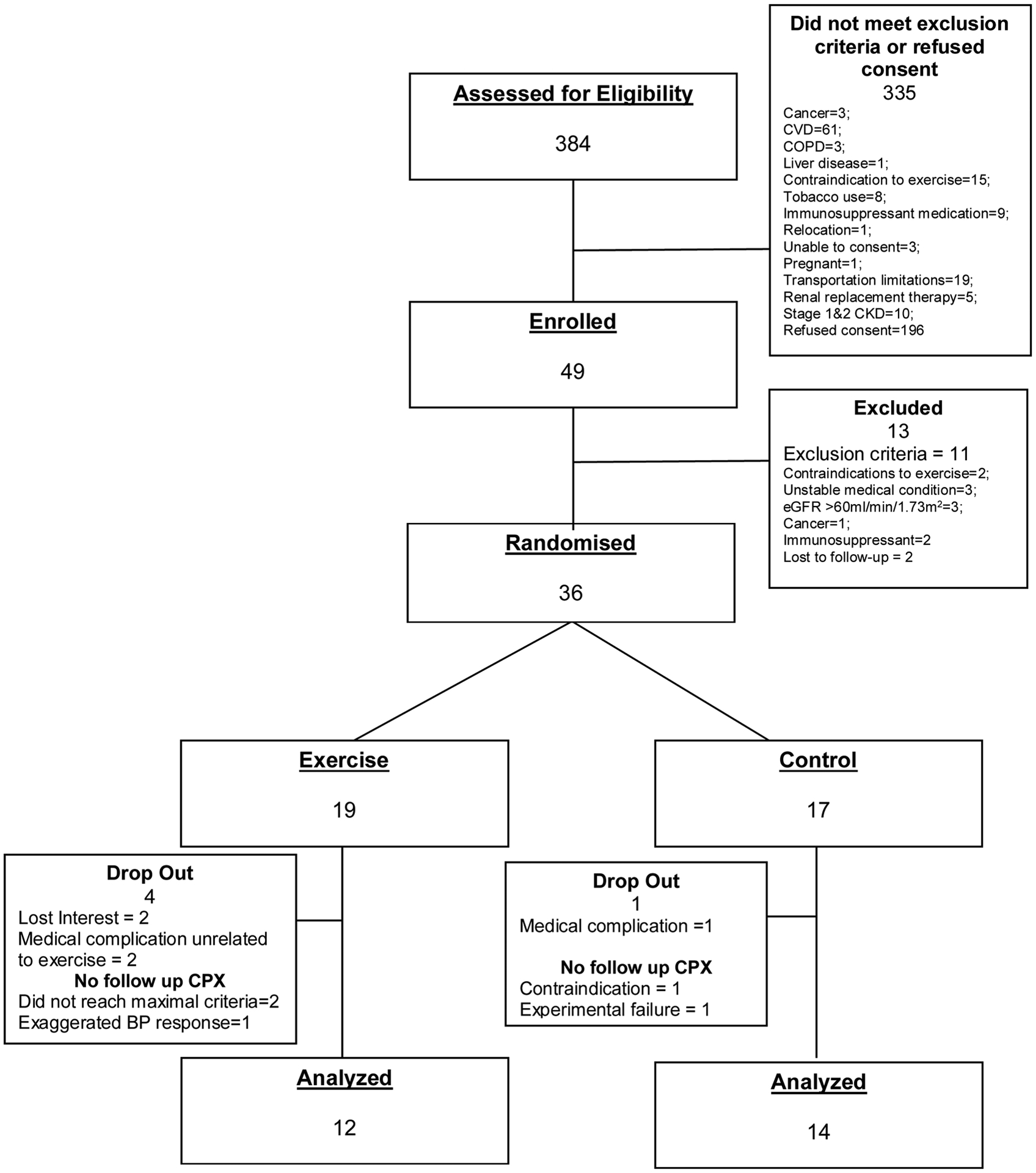

The participant flow through the study is shown in Figure 1. There were no anthropometric, hematologic or biochemical differences between the EXT and the CON group at baseline (Table 1). Because the randomization plan was not stratified by race, there was a higher number of African Americans in the EXT group compared to the CON group (p = 0.02; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPX, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; CVD, cardiovascular disease

Table 1.

Participant characteristics of per-protocol analyzed data for control (CON) and exercise training (EXT).

| CON n = 14 | EXT n = 12 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 62 (9) | 56 (9) | 0.2 |

| Sex (n) | 0.8 | ||

| Female | 3 | 3 | |

| Male | 11 | 9 | |

| Ethnicity (n) | 0.02 | ||

| African American | 2 | 7 | |

| Caucasian | 12 | 4 | |

| Hispanic | 0 | 1 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33 (6) | 30 (3) | 0.1 |

| Hemodynamics | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 130 (20) | 140 (20) | 0.2 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 81 (8) | 83 (16) | 0.6 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 97 (10) | 103 (17) | 0.3 |

| Resting heart rate (bpm) | 69 (12) | 67 (11) | 0.6 |

| Hematology and biochemistry | |||

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 42 (12) | 45 (13) | 0.5 |

| Albumin/globulin ratio | 1.5 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.3) | 0.2 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 30.1 (16.5) | 26.1 (7.7) | 0.4 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | 116 (31) | 117 (39) | 0.9 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 6.5 (1.2) | 6.8 (1.5) | 0.5 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 201 (60) | 188 (35) | 0.5 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 51 (25) | 54 (15) | 0.7 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 118 (46) | 103 (31) | 0.4 |

| Medication (n) | |||

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 6 | 3 | |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 1 | 4 | |

| Beta blocker | 5 | 3 | |

| Calcium channel blocker | 3 | 6 | |

| Diuretic | 5 | 2 | |

| Anti-diabetic | 2 | 3 | |

| Statin | 5 | 7 | |

| Benzodiazepine | 2 | 1 | |

| Erythropoietin stimulating agent | 1 | 0 | |

Data are mean (SD). BMI: body mass index; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL: high density lipoprotein; LDL: low density lipoprotein.

Intervention

Participants allocated to EXT completed the intervention according to the proposed prescription parameters (Figure 2). For individuals included in the analysis, compliance with the intervention was 94% (7). Harms were reported elsewhere (12). No serious or unexpected adverse events were reported (12).

Figure 2.

Participants allocated to the exercise training (EXT) group completed the 12-week intervention according to the prescribed intensity (%HRR, p = 0.03; rating of perceived exertion [RPE], p < 0.01) and duration (p < 0.01) parameters. The supervised exercise prescription was for moderate-to-vigorous–intensity aerobic exercise (60–85% HRR; 12–16 RPE), with participants working up to a duration of 45 min per session. Data are mean (SD). Post-hoc analysis p < 0.05 *, vs week 1; #, vs week 2; ⍦, vs week 3; ⍬, vs week 4; ᴪ, vs week 6; ●, vs week 7; ○, vs week 8 HRR, heart rate reserve; RPE, rating of perceived exertion

Outcomes

Cardiopulmonary Outcomes

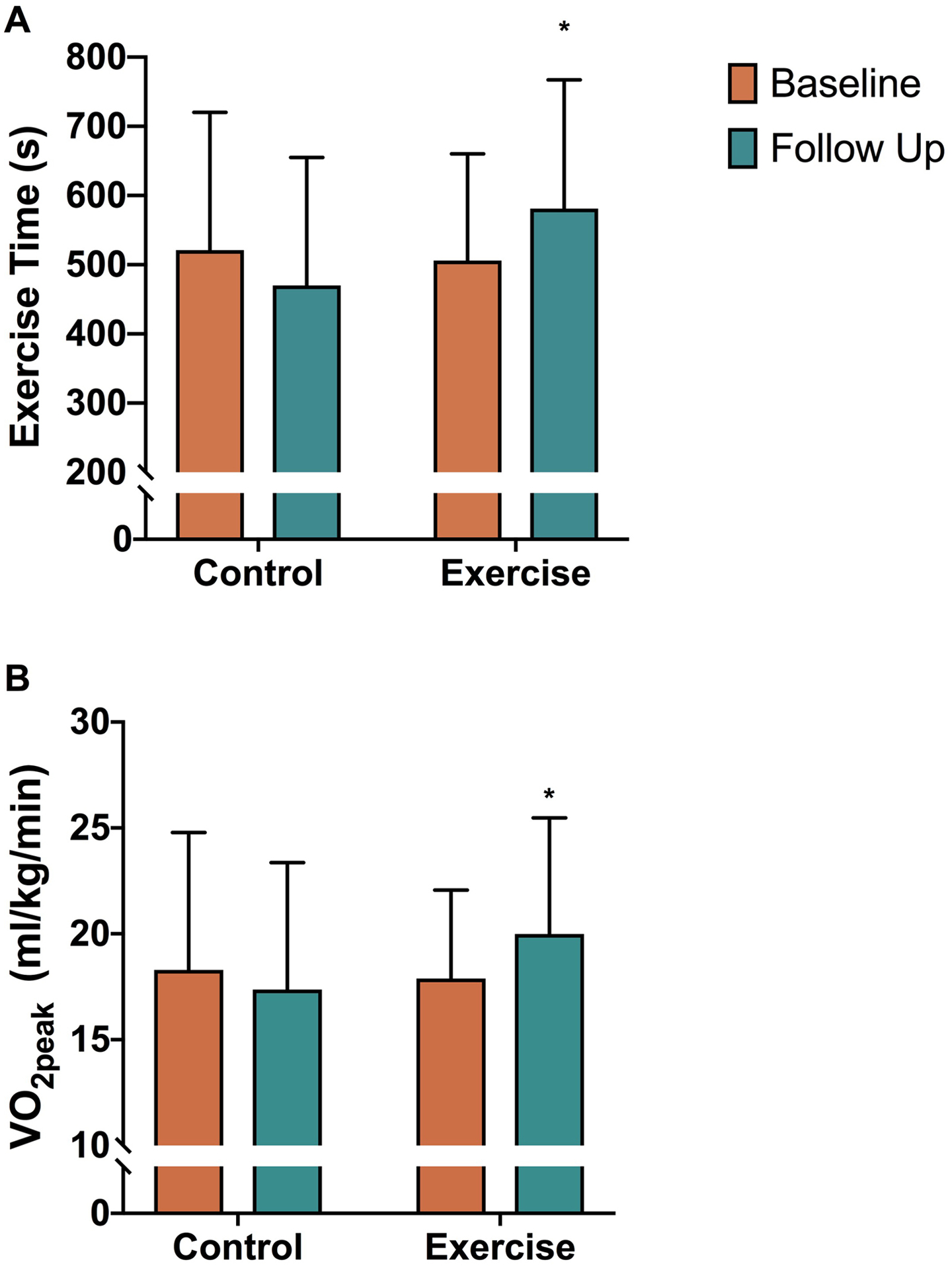

There were no significant differences in body mass between groups over time (baseline vs follow-up, CON: 94.55 [22.47] vs 96.74 [20.74] kg; EXT: 88.23 [13.67] vs 88.30 [14.08] kg; p = 0.3). There was no significant difference in RER (p = 0.3) indicative of equal effort at peak exercise between groups at baseline and follow-up. There was a significant group × time interaction for CPX exercise time p <0.01; d = 0.04) with post-hoc analyses showing an increase in CPX exercise time with EXT (Figure 3; baseline vs follow-up: 506 [154] vs 581 [186] sec, p = 0.01) compared to no change in the CON group (521 [199] vs 470 [185] sec, p=0.06). Likewise, we found a significant group × time interaction for VO2peak (p = 0.01; d = 0.3; Figure 3) with post-hoc analyses showing increased VO2peak with EXT (17.89 [4.18] vs 19.98 [5.49] ml/kg/min, p = 0.04) and no change in the CON group (18.29 [6.49] vs 17.36 [5.99] ml/kg/min, p=0.10). Carbon dioxide production at peak exercise was significantly higher following EXT compared to CON (Table 2), likely owing to the greater amount of work performed during the graded exercise test at follow-up in the former group. A trend towards an improvement in OUES following EXT failed to reach statistical significance (p = 0.08; d = 0.2; Table 2).

Figure 3.

Comparison of control and exercise training groups for VO2peak (p = 0.01) and total exercise time (p < 0.01). Data are mean (SD). *, Post-hoc analysis p < 0.05 vs exercise baseline.

Table 2.

Cardiopulmonary and physical function outcomes for the control (CON) and exercise training (EXT) groups.

| Outcome | CON | EXT | Omnibus ANOVA (interaction) | Effect size (interaction) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | P-value | (d) | |

| CPXHemodynamics | ||||||

| Maximal heart rate (bpm) | 131 (19) | 129 (19) | 149 (27) | 143 (27) | 0.4 | −0.1 |

| Peak systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 192 (39) | 194 (39) | 202 (33) | 199 (33) | 0.6 | −0.1 |

| Peak mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 118 (20) | 120 (20) | 128 (18) | 121 (20) | 0.08 | −0.1 |

| 1-min heart rate recovery (%) | 14 (5) | 12 (6) | 15 (4) | 16 (6) | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| CPXMetabolicOutcomes | ||||||

| Rest | ||||||

| VO2 (ml/kg/min) | 2.72 (0.43) | 3.00 (0.61) | 2.70 (0.40) | 2.92 (0.46) | 0.7 | −0.1 |

| VCO2 (L/min) | 0.21 (0.04) | 0.24 (0.04) | 0.20 (0.03) | 0.22 (0.03) | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| VE | 9.11 (1.67) | 9.73 (2.04) | 8.82 (1.63) | 10.10 (1.66) | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| PECO2 | 21 (1) | 23 (2) | 21 (2) | 20 (2) | 0.01 | −1.5 |

| VentilatoryThreshold | ||||||

| VO2 (ml/kg/min) | 9.70 (3.70) | 10.67 (3.60) | 10.86 (2.89) | 12.46 (2.90) | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| VCO2 (L/min) | 0.81 (0.34) | 0.93 (0.31) | 0.93 (0.39) | 1.16 (0.45) | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| VE | 25.76 (10.75) | 29.60 (8.53) | 27.90 (9.78) | 35.12 (13.39) | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| PECO2 | 27 (2) | 28 (2) | 28 (4) | 27 ± (4) | 0.3 | −0.3 |

| Peak | ||||||

| RER (ratio) | 1.1 (0.08) | 1.1 (0.09) | 1.2 (0.08) | 1.2 (0.09) | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| VO2 (ml/kg/min) | 18.29 (6.49) | 17.36 (5.99) | 17.89 (4.18) | 19.98 (5.49)* | 0.01 | 0.3 |

| VCO2 (L/min) | 1.98 (0.72) | 1.98 (0.64) | 1.90 (0.55) | 2.28 (0.70) | 0.007 | 0.3 |

| VE | 63.12 (26.10) | 65.25 (21.59) | 61.05 (14.34) | 74.41 (24.51) | 0.04 | 0.3 |

| PECO2 | 28 (3) | 27 (2) | 27 (3) | 25 (3) | 0.4 | −0.2 |

| OUES | 1.76 (0.51) | 1.72 (0.53) | 1.67 (0.43) | 1.84 (0.49) | 0.08 | 0.2 |

| VE/VCO2 slope | 32 (7) | 32 (5) | 32 (5) | 33 (5) | 0.09 | 0.1 |

| VE/VO2 slope | 37 (7) | 41 (8) | 40 (7) | 43 ± (8) | 0.9 | −0.1 |

| PhysicalFunction andActivity | ||||||

| 4-m gait speed (s) | 3.07 (0.39) | 3.14 (0.62) | 3.18 (0.68) | 2.98 (0.55) | 0.4 | −0.3 |

| 2-min walk distance (ft) | 530 (100) | 576 (134) | 597 (95) | 635 (70) | 0.8 | 0.0 |

| 30-sec sit to stand (n) | 12 (1) | 13 (2) | 12 (2) | 14 (2) | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Hand grip strength (kg) | ||||||

| Right hand | 37.32 (11.35) | 37.49 (10.51) | 40.74 (10.71) | 39.92 (12.17) | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| Left hand | 36.22 (11.62) | 35.61 (10.05) | 37.22 (9.42) | 37.47 (9.45) | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Physical activity vector magnitude (AU) | 321388 (76073) | 289152 (75430) | 499152 (328126) | 389245 (166950) | 0.3 | −0.3 |

Data are mean (SD). CKD: chronic kidney disease; CPX: cardiopulmonary exercise testing: OUES: oxygen uptake efficiency slope; RER: respiratory exchange ratio; PECO2, partial pressure of mean expired CO2; VE: minute ventilation; VCO2: carbon dioxide production: VO2: oxygen consumption.

Post-hoc analysis P < 0.05 vs exercise baseline.

Although ventilatory rates throughout exercise appeared higher at rest and throughout exercise after EXT, there were no statistically significant changes observed between the groups from baseline to follow up (Table 2). A significant group × time interaction for resting PECO2 p = 0.01; d = −1.5) indicated decreased or attenuated values for the EXT than CON group, suggestive of lower alveoli CO2 levels at rest (Table 2). However, the post-hoc analyses failed to reach statistical significance. Following EXT, the PECO2 profile throughout exercise resembled a pattern similar to that in a healthy population, showing a decline in values from the ventilatory threshold to peak exercise that is attributable to acidosis-induced hyperventilation. This pattern was not observed at baseline in the EXT or CON group. However, this change in PECO2 pattern throughout the graded exercise test from baseline to follow-up in the EXT group was not statistically significant (p = 0.4). The VE/VCO2 slope did not change between groups across time (Table 2). In addition, ventilatory cost of oxygen uptake, reflected by the VE/VO2 slope, did not change significantly. Taken together, the non-significant observations pertaining to ventilation, PECO2 and VE/VCO2 and VE/VO2 slopes suggest no exercise-related improvements in ventilation perfusion (V/Q) mismatching in these patients.

The hemodynamic responses to exercise are displayed in Table 2. Exercise training did not affect autonomic function, as shown by no significant changes in maximal heart rate and heart rate recovery. Similarly, exercise training had no effect on the maximal blood pressure response to exercise. A significant group × time interaction suggested improvements in mean relative oxygen pulse (p = 0.04; d = 0.3), an index of stroke volume in association with oxygen extraction, in the EXT versus CON group (0.12 [0.02] vs 0.14 [0.04]; post-hoc analysis p = 0.07; and 0.14 [0.05] vs 0.14 [0.04]; post-hoc analysis p = 0.3).

The observed exercise-related improvements in VO2peak did not translate to improvements in physical function. The groups did not significantly differ in grip strength, gait speed, lower body functional strength and functional endurance across time (Table 2). In addition, there were no changes in habitual physical activity levels.

Power analysis

A post-hoc power analysis based on the primary outcome measure of VO2peak determined that the sample size had a power of 90% to detect a significant interaction (G-Power 3.1, Dusseldorf, Germany).

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of moderate-to-vigorous intensity, supervised aerobic exercise on cardiopulmonary and physical function in non-dialysis patients with CKD without overt CVD. The findings showed improvements in cardiopulmonary reserve following exercise training as evidenced by small but significant improvements in VO2peak and exercise time. However, exercise training did not improve the autonomic response to exercise or ventilatory perfusion mismatch in these patients. Furthermore, exercise-related improvements in VO2peak did not translate to beneficial changes in physical function and habitual physical activity.

Cardiorespiratory fitness, represented by oxygen consumption at peak exercise (VO2peak), is associated with intermediate markers of CVD and is an independent predictor of mortality in CKD patients (6, 9). The findings of this study showed that 12 weeks of supervised, moderate-to-vigorous intensity aerobic exercise significantly improved VO2peak. Despite these significant increases in VO2peak, the increase is cardiorespiratory fitness was blunted as compared with the general aging population who typically report around a 2-fold greater increase in VO2peak after exercise training compared to the changes observed herein (16). Furthermore, despite significant improvements in the VO2peak following EXT, the values still remain below sedentary, age-matched normative values for the general population (2). Moreover, the mean 2.09-ml/kg/min increase in VO2peak in this study falls just short of the minimal clinically important change of 2.8 ml/kg/min that has previously been reported for CKD patients (17). Although improvements in VO2peak following exercise training are more consistently reported in the dialysis population (10), the changes in aerobic exercise capacity after exercise training are less established and more disparate in non-dialysis patients, with increases in VO2peak ranging from 2% to 15%. Many of these aerobic interventions in the non-dialysis CKD population prescribed exercise of a moderate intensity, similar to our study, which implemented moderate-to-vigorous intensity exercise. In comparison to our trial, interventions of longer duration (~ 1 year) seem to confer larger increases in VO2peak after aerobic exercise. In line with our findings, Stray-Gunderson et al. showed significant increases in VO2peak in hemodialysis after exercise training; however, the documented improvements were only modest in comparison to age-matched healthy individuals. Several other studies reported no significant changes in VO2peak in non-dialysis CKD patients after a similar exercise intervention as prescribed in this study (21, 24). Taken together with our findings, these data suggest a blunted cardiorespiratory adaptation to exercise training in this patient population.

Although we report modest improvements in VO2peak after exercise training, aerobic exercise did not alter other important cardiopulmonary outcomes, particularly those pertaining to V/Q mismatch. The lack of findings related to these outcomes is noteworthy because measures of V/Q mismatch such as VE/VCO2 are broadly indicative of disease severity and strongly predict prognosis (11). A number of potential causes are speculated to contribute to V/Q mismatch in mild-to-moderate CKD, ranging from pulmonary hypertension secondary to a combination of left ventricular dysfunction and vascular endothelial dysfunction to obstructive and restrictive pulmonary dysfunction (2). More detailed studies investigating the effect of exercise training on these pathophysiological domains are warranted.

Contrary to our hypothesis, the changes in cardiorespiratory fitness after exercise training did not confer benefits in physical function. Of note, this is consistently reported in both people with non-dialysis and hemodialysis CKD after both aerobic (10) and resistance exercise interventions (25, 26). The discouraging lack of a physical function effect is surprising considering that similar interventions carried out in other disease conditions resulted in significant increases in the same measures of functional capacity (27). A potential explanation for our findings may be a learning effect associated with our functional testing battery. Variation in this learning effect may have masked any potential interaction effects. In addition, it is also possible that the functional testing battery utilized in this study is not valid in CKD patients. In this respect, the 2-min walk distance test has not yet been validated as a predictor of VO2peak in this patient population, and a longer test, such as the 6-min walk test, would potentially elicit changes in functional endurance. To accurately investigate the effects of exercise in the CKD population, researchers should establish a valid and reliable battery of physical function tests that are both specific and sensitive enough to detect changes in functional capacity. The universal use of such a testing battery will help determine whether the discouraging lack of findings pertaining to physical function in these patients are due to the “noise” associated with the currently utilized tests or actual physiological limitations to improving function. The lack of changes in habitual physical activity provides support that physical activity was controlled for as a potential confounding variable and that our findings resulted from the exercise intervention as opposed to changes in habitual physical activity.

The overall findings of this study suggest that both cardiopulmonary and physical function adaptations to aerobic exercise training appear to be blunted or limited in CKD patients. Indeed, exercise intolerance is characteristic of this disease state, and the physiological mechanisms underlying these limitations to exercise capacity may be unresponsive to exercise training and may therefore limit training adaptations. In this respect, left ventricular dysfunction is thought to be a central limitation to exercise capacity in these patients, even before the development of overt CVD. Although the findings of this study showed a trend toward an increase in stroke volume in association with oxygen uptake (O2pulse), this improvement was not likely large enough to substantially increase exercise capacity. Furthermore, peripheral limitations such as impaired vascular function (that hampers oxygen delivery to the working muscle) (30) and abnormal skeletal muscle function (that reduces oxygen utilization), including insulin resistance, have also been suggested as contributing to CKD-related exercise intolerance. In this regard, our group recently reported blunted conduit-artery vascular endothelial function and arterial hemodynamic adaptations to exercise training in these patients (12). Furthermore, the findings of this study showed no improvement in the ventilatory cost of oxygen uptake (VE/VO2), which suggests a lack of exercise-related adaptations pertaining to oxygen utilization at the level of the working muscle (11). Future studies investigating the effects of exercise on oxygen tissue diffusing capacity and skeletal muscle mitochondria function will better inform our findings.

A limitation of this study is that a large number of patients were on antihypertensive medications such as beta-blockers that affect the autonomic response to exercise. The patients were required to take their medications as usual for the exercise tests for safety reasons and to allow them to reach peak exercise without an exaggerated blood pressure response that would require early test termination. As a result, accurately interpreting the effects of exercise training on autonomic function is difficult. Future studies that investigate this outcome more comprehensively are warranted. An additional limitation is that we did not stratify our randomization strategy by race. As such, there were more African Americans in the EXT than CON group. Whether there are racial differences in exercise training in both the general and CKD populations is unclear. Finally, we did not study the effects of exercise training on systemic outcomes such as inflammation and the renin angiotensin aldosterone system and how they pertain to exercise intolerance, which warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, in non-dialysis patients with CKD and without overt CVD, a 12-week course of moderate-to-high–intensity aerobic exercise improved cardiorespiratory fitness and exercise time, but the observed improvements appear to be blunted. Improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness did not translate into improved physical function. Future interventions that target the physiological mechanisms of CKD-related exercise intolerance, coupled with exercise training, may result in superior cardiopulmonary adaptations to exercise training.

Acknowledgements.

The authors thank the participants of the study.

Funding.

US National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (no. HL113514).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest. None declared.

References

- 1.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LYC, Bhave N, Bragg-Gresham J, et al. US Renal Data System 2017 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71 (3s1):A7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkman DL, Muth BJ, Stock JM, Townsend RR, Edwards DG. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing reveals subclinical abnormalities in chronic kidney disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25 (16):1717–24. doi: 10.1177/2047487318777777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansen KL, Painter P. Exercise in individuals with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59 (1):126–34. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odden MC, Chertow GM, Fried LF, Newman AB, Connelly S, Angleman S, et al. Cystatin C and measures of physical function in elderly adults: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition (HABC) Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164 (12):1180–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roshanravan B, Robinson-Cohen C, Patel KV, Ayers E, Littman AJ, de Boer IH, et al. Association between physical performance and all-cause mortality in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24 (5):822–30. doi: 10.1681/asn.2012070702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sietsema KE, Amato A, Adler SG, Brass EP. Exercise capacity as a predictor of survival among ambulatory patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2004;65 (2):719–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenwood SA, Castle E, Lindup H, Mayes J, Waite I, Grant D, et al. Mortality and morbidity following exercise-based renal rehabilitation in patients with chronic kidney disease: the effect of programme completion and change in exercise capacity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34 (4):618–25. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagels AA, Soderkvist BK, Medin C, Hylander B, Heiwe S. Health-related quality of life in different stages of chronic kidney disease and at initiation of dialysis treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:71. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howden EJ, Weston K, Leano R, Sharman JE, Marwick TH, Isbel NM, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiovascular burden in chronic kidney disease. J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18 (4):492–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise training for adults with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011. (10):Cd003236. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003236.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT, Chaitman BR, Fletcher GF, Froelicher VF, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40 (8):1531–40. doi/ 10.1161/01.CIR.0000034670.06526.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkman DL, Ramick MG, Muth BJ, Stock JM, Pohlig RT, Townsend RT, et al. The Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Vascular Function in Non-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00539.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baba R, Nagashima M, Goto M, Nagano Y, Yokota M, Tauchi N, et al. Oxygen uptake efficiency slope: a new index of cardiorespiratory functional reserve derived from the relation between oxygen uptake and minute ventilation during incremental exercise. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28 (6):1567–72. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones J, Rikli R. Senior Fitness Testing Manual. Second Edition ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Ng AV, Mulligan K, Carey S, Schoenfeld PY, et al. Physical activity levels in patients on hemodialysis and healthy sedentary controls. Kidney Int. 2000;57 (6):2564–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurst C, Weston KL, McLaren SJ, Weston M. The effects of same-session combined exercise training on cardiorespiratory and functional fitness in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson T, Xenophontos S, Gould D, et al. Test-retest reliability, validation, and ‘minimal detectable change’ scores for a range of common physical function and strength tests in non- dialysis CKD. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019; 35 (6):565–76. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1455249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mustata S, Groeneveld S, Davidson W, Ford G, Kiland K, Manns B. Effects of exercise training on physical impairment, arterial stiffness and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease: a pilot study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2011;43 (4):1133–41. doi: 10.1007/s11255-010-9823-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pechter U, Ots M, Mesikepp S, Zilmer K, Kullissaar T, Vihalemm T, et al. Beneficial effects of water-based exercise in patients with chronic kidney disease. Int J Rehabil Res. 2003;26 (2):153–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mrr.0000070755.63544.5a. P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Headley S, Germain M, Milch C, Pescatello L, Coughlin MA, Nindl BC, et al. Exercise training improves HR responses and V˙O2peak in predialysis kidney patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44 (12):2392–9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318268c70c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leehey DJ, Moinuddin I, Bast JP, Qureshi S, Jelinek CS, Cooper C, et al. Aerobic exercise in obese diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: a randomized and controlled pilot study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8:62. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyce ML, Robergs RA, Avasthi PS, Roldan C, Foster A, Montner P, et al. Exercise training by individuals with predialysis renal failure: cardiorespiratory endurance, hypertension, and renal function. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30 (2):180–92. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stray-Gundersen J, Howden EJ, Parsons DB, Thompson JR. Neither Hematocrit Normalization nor Exercise Training Restores Oxygen Consumption to Normal Levels in Hemodialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27 (12):3769–79. doi: 10.1681/asn.2015091034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson EL, Gould DW, Wilkinson TJ, Xenophontos S, Clarke AL, Vogt BP, et al. Twelve-week combined resistance and aerobic training confers greater benefits than aerobic training alone in nondialysis CKD. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018;314 (6):F1188–f96. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00012.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkman DL, Mullins P, Junglee NA, Kumwenda M, Jibani MM, Macdonald JH. Anabolic exercise in haemodialysis patients: a randomised controlled pilot study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2014;5 (3):199–207. doi: 10.1007/s13539-014-0140-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheema B, Abas H, Smith B, O’Sullivan A, Chan M, Patwardhan A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of intradialytic resistance training to target muscle wasting in ESRD: the Progressive Exercise for Anabolism in Kidney Disease (PEAK) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50 (4):574–84. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buford TW, Hsu FC, Brinkley TE, Carter CS, Church TS, Dodson JA, et al. Genetic influence on exercise-induced changes in physical function among mobility-limited older adults. Physiol Genomics. 2014;46 (5):149–58. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00169.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnasamy R, Hawley CM, Stanton T, Howden EJ, Beetham KS, Strand H, et al. Association between left ventricular global longitudinal strain, health-related quality of life and functional capacity in chronic kidney disease patients with preserved ejection fraction. Nephrology (Carlton). 2016;21 (2):108–15. doi: 10.1111/nep.12557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macdonald JH, Fearn L, Jibani M, Marcora SM. Exertional fatigue in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60 (6):930–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Craenenbroeck AH, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Van Ackeren K, Hoymans VY, Verpooten GA, Vrints CJ, et al. Impaired vascular function contributes to exercise intolerance in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31 (12):2064–72. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]