Abstract

Introduction

Big data technologies have been talked up in the fields of science and medicine. The V-criteria (volume, variety, velocity and veracity, etc) for defining big data have been well-known and even quoted in most research articles; however, big data research into public health is often misrepresented due to certain common misconceptions. Such misrepresentations and misconceptions would mislead study designs, research findings and healthcare decision-making. This study aims to identify the V-eligibility of big data studies and their technologies applied to environmental health and health services research that explicitly claim to be big data studies.

Methods and analysis

Our protocol follows Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P). Scoping review and/or systematic review will be conducted. The results will be reported using PRISMA for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR), or PRISMA 2020 and Synthesis Without Meta-analysis guideline. Web of Science, PubMed, Medline and ProQuest Central will be searched for the articles from the database inception to 2021. Two reviewers will independently select eligible studies and extract specified data. The numeric data will be analysed with R statistical software. The text data will be analysed with NVivo wherever applicable.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will review the literature of big data research related to both environmental health and health services. Ethics approval is not required as all data are publicly available and involves confidential personal data. We will disseminate our findings in a peer-reviewed journal.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42021202306.

Keywords: public health, occupational & industrial medicine, biotechnology & bioinformatics, health services administration & management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first one to assess the V-eligibility of public health studies for big data research, particularly in environmental health and health services research.

It highlights the characteristics of V-eligible big data research and promotes the proper use of big data in environmental health and health services research.

Some research articles could be too obscure in reporting their V-eligibility.

Some researchers might not respond to our email queries and online questionnaire survey to clarify and verify information.

Introduction

Environment affects human health

The quality of the environment is a powerful determinant of human health. Environmental health refers to the influence of environmental factors on human health.1 2 The environmental factors that are attributable to diseases of high global burden have been classified into physical, chemical, biological, social and other factors.3 Recent studies reported that 23% of deaths between 2006 and 2016 were attributable to environmental causes.4 5 Environmental health once focused on the prevention of infectious diseases; however, the focus has shifted toward chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases.6 The WHO estimated that ischaemic heart disease is the biggest killer worldwide (16% of total deaths) in 2019.7 The reduction of environmental risks such as PM2.5 levels in the air was associated with decreases in cardiovascular mortality.8 Although the US Environmental Protection Agency was established in the 1970s and aimed to manage air, water and soil pollution control and remediation, air pollution continues to be the largest environmental health risk to public health in the US.9 The simple statistical learning methods to study the linkage of environmental health risk factors and potential diseases have been replaced by the big data analysis methods, which improves the accuracy of evaluation, evolves our understanding of the relationship between environmental and human health, and enhances public health policies that reduce populations at risk. For example, since previous studies demonstrated that reduction in air pollution exposure can improve respiratory health, a recent study used a deep neural network method to identify the environmental health risk factors of acute respiratory diseases.10 Additionally, a recent study launched a national long-term birth cohort study that aimed to use big data to investigate environmental influences on children’s health and address the need for public health strategies to reduce the burden of environment-related diseases.11

Health services in public health

The implementation of health services focuses on individuals, and the target of public health is the health condition of the overall population.12–15 Offering health services inside or outside the clinical stage to the population is a critical strategy for developing and maintaining public health.15 Health services need to be sufficiently available, high-quality, cost-affordable, and accessible.16–18 Both health services and public health strive to prevent and intervene against acute diseases, chronic diseases, injuries, and risks.12 Diverse health services (eg, data monitoring, primary healthcare, illness screening, injury protection, drug development, and health promotion) and professional personnel collaboratively benefit the health of the public, and the public health services system plays an irreplaceable role in the management of individual health.12 16 19

Data regarding incidence, morbidity, prevalence, mortality, and rate of recovery that are obtained from the health services system not only inform the data monitoring and surveillance in epidemiology, but also serve as references for the development of health promotion policies and strategies.14 The construction of sufficient and efficient health services is necessary for response and recovery during public health emergencies.18

What is big data?

The term big data was first used at Silicon Graphics in the mid-1990s according to Diebold,20 Cox et al21 first used big data in publications on data-intensive computing in 1997. The term big data was defined in various ways in recent publications. Laney22 highlighted three dimensions (volume, velocity, and variety) of big data in a research note in 2001. Moreover, De Mauro et al23 characterised big data as high volume, high velocity, and high variety (the 3Vs criteria). Specially designed technologies and analytics are required to transform such data into valuable information.

Use of big data in environmental health research

Data-intensive research in environmental health has grown,24 especially over the last two decades.25 These studies require large datasets. For instance, studies on air pollution26 have processed terabytes of data to identify air pollution as the largest killer worldwide.27 Meanwhile, deaths due to chemical pollution and soil pollution have also been increasing.28 Studies on mobile health would require several gigabytes of GPS data.29 As big data became a buzzword in public health research, some researchers may not aware of or did not follow its definitions. It is not uncommon for non-trivial datasets to be called big data. As a result, non-V-eligible (zero V) big data research on environmental health exists that could mislead healthcare decision-makers. This is the first study that seeks to identify the V-eligibility of big data studies and their technologies applied to environmental health research. It is anticipated that the findings will promote V-eligible big data research on environmental health.

Use of big data in health services research

Big data and its technologies change rapidly and improve the efficiency of various data workflows, such as data collection, processing, utilisation, and management in health services; examples include electronic health records (EHR), digital health applications, research studies, and so on.30–34 Based on a preliminary search that was conducted in the Web of Science (WOS), 34% of all published big data research in public-health-related categories (ie, primary healthcare, public, environmental and occupational health, healthcare sciences and services, health policy and services) covered health services. Developing big data technologies and architectures such as Internet of Things (IoT) based patient monitoring system,35 which facilitate the continued exploration of health services such as the performance of operations, development of personalised medicine, evaluation of policies, reduction of medical expenses,36 disease prevention, enhancement of overall service capacity and communication among service providers, mediators and receivers.36 37

Recent research38–41 identified the major challenges of big data including data structure, data security, data standardisation, data storage and transfer, and training of data analysts. For example, data management in health services was hindered by difficulties in sharing EHRs due to slow standardisation, non-compliance with standards, and a lack of expertise. In addition, big data is not easy to manage using traditional database technology designed for well-structured data. Moreover, enabling artificial intelligence investigations into big data analytics would require even better technologies.30 42

Big data have outgrown traditional data technologies

Big data analytics, like that for traditional data, aims to generate information from data but with different technologies.43 Even if parts of big data were stored in traditional databases, yet multiple sources and fast growth of such data (eg, from the web, social networks, sensor networks, scientific experiments and others) in terms of types, sizes, timeliness, and complexity would require big data analytics.44 45 Integrating various forms of data, that is, structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data, would also require big data analytics,46 rather than the ordinary Structured Query Language designed for managing relational databases.43 Therefore, data-intensive computing tools, for example, Hadoop and Spark, are commonly used for dig data processing.45 There have been unstructured data management systems for healthcare data; for example, Luo et al47 developed a double-reading/entry system for extracting key-value data items (ie, structured data) from the unstructured medical records (ie, texts, drawings, laboratory test results and physicians’ notes) and for curating semi-structured EHR databases.

The V-criteria for big data

What makes big data different from ordinary data? The main differences lie in the so-called ‘V’ characteristics of big data.43 Laney originally suggested that volume, variety, and velocity are the three basic ‘Vs’ that characterise big data, as originally suggested by META Group.22 Then big data’s characteristics surpassed the 3Vs. Yin et al48 stated that volume, variety, velocity, veracity, and value are the 5Vs of big data. Andreu-Perez et al49 stated that volume, variety, velocity, veracity, value, and variability are the 6Vs that are applicable to health data research. Among these characteristics, volume, variety, velocity, and veracity constitute the most popular criteria for big data.50 51 Therefore, these 4Vs criteria (table 1) were adopted in this review.

Table 1.

V-criteria for big data, particularly data generation and processing

| Item | Details |

| Volume | Terabytes, petabytes, or above |

| Variety | In various forms (ie, structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data) and from various sources of data |

| Velocity | In real time or near real time |

| Veracity | Highly consistent, traceable, and reliable data |

Volume, or the magnitude of data generated every second, describes how big the datasets are.52 The size of big data should span terabytes and petabytes.53 54 There have already been data that exceed zettabytes, and the data sizes are expected to increase 20-fold within the next 10 years.48 Nevertheless, the size alone does not define big data.49

Variety or the structural heterogeneity of a dataset, refers to the coexistence of various types of data (ie, structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data).44–46 In contrast to tabular data and other well-structured data,52 images, audio, and videos are unstructured data that require customised analysis.55 Extensible Markup Language and JavaScript Object Notation are useful techniques for managing semi-structured data.56

Velocity refers to the speed and rate at which data are generated and analysed to create, capture, process and store data.53 Given the rapid growth of data integration, a real-time processing solution is needed. A data stream is an unbounded sequence of event processing in real time or near real time.56 In environmental health research, real-time streams are commonly used in distributed and remote sensing techniques.3 26 55

Veracity, or the trustworthiness of the data, refers to the reliability and provenance of the data.50 For obvious reasons such as the sheer volume of data, big data must be cleaned and harmonised in an automated manner.53

Kitchin et al57 found that few environmental health datasets fulfilled the 3Vs (ie, very large volume, fast and continuous velocity, and wide variety). Some datasets, such as sensors for pollution and sound, only produce gigabytes of data per year. In addition, insufficient data quality, precision, and timeliness of the IoT-generated big IoT data presented challenges to the processing of big data.58 Although social sensing has widespread usage in mobile devices, its reliability (ie, veracity) still requires slow human verification.59

Big data research in medicine is often misrepresented

Traditional IT approaches to data management are no longer suitable for managing large unstructured data and processing data-intensive tasks.60 For example, Excel and SPSS were not designed for handling big data61 but are often used in non-V-eligible big data research as the main (if not only) data management and processing tools. Common visualisation software (eg, Pajek and Cytoscape for visualisation of the social/biological networks of above-average sizes) was not designed for big data, but were often mislabelled in non-V-eligible research as big data tools. Genuine big data research requires special data engineering to facilitate the acquisition, access, processing, analysis, mining, modelling, and so on.62 In particular, ensemble analysis, association analysis, high-dimensional analysis, deep analysis, precision analysis, and divide-and-conquer analysis have been proposed as the six major strategies and technologies that enable big data research.63

Objectives

This study aims to identify the V-eligibility of big data studies on and their technologies applied to environmental health and health services research that explicitly claimed to be big data studies.

Methods

This protocol follows Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P)64 and was registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, dated 4 January 2021. Based on the actual extractable data types from the included studies, scoping review and/or systematic review will be compared in their V- eligibility. Wherever applicable, the reporting of results will follow PRISMA for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR),65 PRISMA 202066 and Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) guideline.67 The PRISMA-P checklist for this protocol is available as a separate supplementary document (online supplemental appendix 1). The actual start date of this review was 1 December 2020. The anticipated completion date is 31 March 2022.

bmjopen-2021-053447supp001.pdf (43.5KB, pdf)

Study selection criteria

Human research articles that explicitly claimed to be big data research on environmental health or health services will be included. The selected studies will cover all types of research, including exploratory research, descriptive research, and experimental research. Non-human studies (eg, animal or plants studies) will be excluded. Non-original research articles including reviews articles (eg, literature reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses), book reviews, editorials, commentaries, expert opinions, monographs, case reports, case series, protocols, debates, meeting reports, guidelines, subject indexes, round table reports, and forum reports will be excluded. No restrictions will be imposed on the participants, interventions, or comparators. Besides, the eligible article must be written in English and accessible online with full text.

Data sources and search strategy

The search for environmental health research

Literature databases, including the WOS, PubMed, Medline (EBSCOhost interface), and ProQuest Central, will be searched, through the application of a search strategy specified in previous reviews that covered the same field of environmental health research.68 69 Search terms will include “environmental health”, “environmental exposure”, “environmental illness” and “environmental epidemiology”, and the term “big data”. No restrictions will be imposed to study type, language, and timespan. The full search strategies for different databases are available (online supplemental appendix 2).

bmjopen-2021-053447supp002.pdf (46.8KB, pdf)

The search for health services research

There are two major keywords: (1) “big data” and (2) “health services”. All conceptual categories will be formulated from keywords with the Boolean operators supported by the databases. All articles will be searched from same databases of the part of environmental health. Details of the search strategy are provided in online supplemental appendix 3.

bmjopen-2021-053447supp003.pdf (122KB, pdf)

Study selection

The studies initially identified through literature databases will be imported into EndNote V.20 citation manager software.70 EndNote V.20 software will remove duplicates and the no-original research articles including reviews, book reviews, editorials, commentaries, expert opinions, monographs, case reports, case series, protocols, debates, meeting reports, guidelines, subject indexes, round table reports, and forum reports. Two reviewers (TPP, TIL) will independently screen the titles and abstracts of all retrieved studies according to study selection criteria. The full text of the relevant articles will be downloaded for further evaluation of eligibility. The studies which full-text is not retrievable from databases nor obtainable from the author(s) will be excluded. Studies about data security, equipment or machine health, and product or electronic system health will be excluded. Articles that did not mention the use of big data curation, management, analysis, nor applications will be excluded.

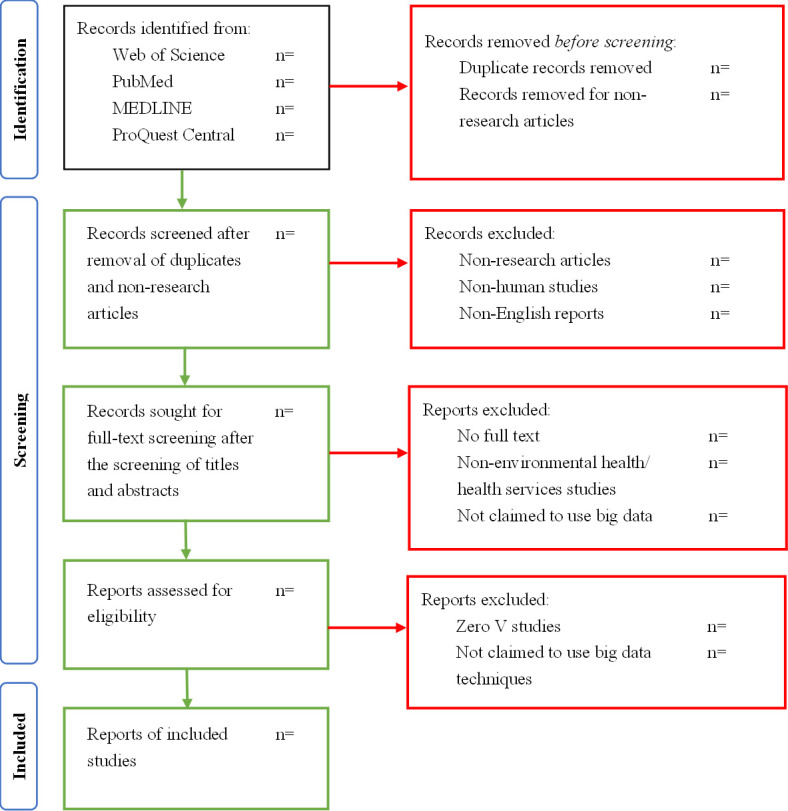

The records screened by both reviewers will be compared by cross-tabulation. Any disagreements between two reviewers during study selection will be resolved through discussion with the third reviewer for consensus. The included reports after full-text screening will be assessed for their V-eligibility. Zero V studies and the studies which do not claim to use big data will be excluded. A flow diagram for study search and selection is provided in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart diagram for study selection.

For the studies that are: (1) not clearly indicated in terms of volume or less than a terabyte in volume; (2) used very simple formats (eg, 2-D tables) of data, or only one data source; (3) not real-time or near real-time in data generation; (4) not trackable or trustworthy in data provenance, questionnaires will be sent to the authors for confirmation. The authors will have one month to reply email and/or return questionnaires.

Information extraction

The studies which meet at least one V (volume, variety, velocity, or veracity) will be included for information extraction and analysis. The text of the following six categories will be extracted from the included studies:

Publication information: authors(s) names, article titles, publication years, countries of the first author’s research centre or organisation, and journal titles;

Types of articles: full research articles, short research reports, and methodology papers;

Vs criteria for big data: data characteristics, data collection and processing details (sample sizes, data processing speeds, accuracy measures etc.), and analysis methodologies;

Categories of big data applications (examples): environmental health (major topics as covered by environmental health literature, eg, environmental pollution, environmental health hazards, environmental exposures, environmental diseases, work environment and health, vulnerable groups, and environmental health risk assessment);25 health services (genomics, elderly care, mental health, personalised healthcare, drug discovery, clinical research, financial benefits, etc);

Claimed big data techniques (examples): cluster analysis, data mining, graph analytics, machine learning, natural language processing, neural network, pattern recognition, and spatial analysis, etc;71 and

Data sources (examples): electronic health records (EHR), biomarkers, health insurance claims, clinical trials, social media, wearables, sensors, and so on.

Subgroup analyses will be performed if sufficient data are available. Possible subgroups include, for example, big data applications, big data techniques, and big data sources.

Any disagreements in the information extraction process between two reviewers will be resolved through discussion with the third reviewer. Examples of the information to be analysed by cross-tabulation are as shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Information extraction form (example)

| Title | Author(s) | Year | Country | Journal | Type of study | Subgroup | V(s) | Volume (number of records) | Volume per record | Volume (total sample size) | Variety (type(s) of data) | Velocity (frequency of generation) | Velocity (frequency of handling, recording, publishing) | Veracity | Data analysis |

| … | … | 2020 | … | … | Original research article | Big data application: environmental pollution | 3Vs | … | … | … | Structured/ unstructured | Real time | Daily | N/A | … |

| … | … | 2013 | … | … | Original research article | Big data application: work environment and health | 4Vs | … | … | … | Unstructured | Near real time | At time | … | … |

| … | … | 2017 | … | … | Methodology /method | Big data techniques | 2Vs | … | … | … | Structured | N/A | N/A | N/A | … |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

N/A, not available from the papers.

Moreover, Nvivo, a qualitative data analysis software, will be used to manage and analyse the text data. Relevant and distinctive text excerpts will be coded as themes (nodes) for comparison among studies. Synonyms with varied morphology will be automatically handled in identifying common themes. Then, the software will perform proper text analysis72 according to the identified themes.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes will be categorised into types of study design, subgroups, and the V-eligibility of the included studies. The secondary outcomes will be the types of big data analytics used in the included studies. A specification of our data analysis plan is given below.

Data synthesis and analysis

Categories regarding the outcomes above will be collected and analysed by basic descriptive statistics with R software.73 The results will be summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the articles on big data in environmental health or health services

| Environmental heath/health services | |

| Publication information | |

| Years of publication | …(…) (…) |

| JCR quartiles (Q1—Q4) | |

| Countries of corresponding authors | |

| Institutions | |

| Departments (medical and IT, etc) | |

| Funders (universities, governments, companies, etc) | |

| Volume | |

| Number of records | …(…) (…) |

| Sample size/number of participants | …(…) (…) |

| Number of variables | …(…) (…) |

| Time points for longitudinal studies | |

| Data size (terabytes) | |

| Variety (type(s) of data), N (%) | |

| Structured | … (…%) |

| Semi-structured | … (…%) |

| Non-structured | … (…%) |

| … | … |

JCR, Journal Citation Reports.

The text data (ie, characteristics and analysis technologies of big data) will be qualitatively analysed with Nvivo. The eligibility for big data studies will be evaluated by their identities and number of Vs (0–4) in terms of the V criteria.

All the above-mentioned synthesis and analysis processes will be undertaken by two reviewers and any disagreement will be discussed with the third reviewer for consensus. The results will be visualised with tables and graphic charts. The body of evidence will not be assessed in this study. The examples of the result table will be performed in tables 4–10.

Table 4.

Examples of data synthesis

| Type of study | Title | Authors | Year | Categories | V(s) | Volume (number of records) | Volume per record | Volume (total sample size) | Variety (type(s) of data) | Velocity (frequency of generation) | Velocity (frequency of handling, recording, publishing) | Veracity | Data analysis |

| Original research article | … | … | 2020 | Big data application: environmental pollution | 3Vs | Positive | Unclear | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative | N/A | Negative |

| … | … | 2013 | Big data application: work environment and health | 4Vs | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative | |

| Methodology/method | … | … | 2017 | Big data techniques | 2Vs | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | N/A | N/A | N/A | Negative |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

Table 5.

Application of big data analytics techniques for environmental health

| Analytics techniques | Area | Environmental health | Sources |

| Machine learning | Water | … | … |

| Air | … | … | |

| Graph analytics | Food | … | … |

| Soil | … | … | |

| Wastes | … | … | |

| … | … | … | … |

Table 6.

Application of big data analytics techniques for health services

| Analytics techniques | Area | Healthcare services | Sources |

| ML (Machine learning) | Neurology | … | … |

| Neural network | Epidemiology | … | … |

| … | … | … | … |

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics of the characteristics of the included studies

| Field of techniques | Number of papers |

| General description | |

| AI only, N (%) | …(…%) |

| Traditional statistics only N (%) | …(…%) |

| Both AI and traditional methods N (%) | …(…%) |

| AI methods, N (%) | …(…%) |

| Deep learning, N | … |

| Classic ML, N | … |

| Linear regression | … |

| Logistic regression | … |

| Naïve Bayes | … |

| … | … |

| Traditional methods, N (%) | …(…%) |

| Regression methods, N | … |

| … | … |

Classic ML: linear regression, logistic regression, naïve Bayes, decision tree, k-nearest neighbour, random forest, discriminant analysis, support vector machine and neural network.

ML, machine learning.

Table 8.

Summary statistics of the included studies on different fields of application for environmental health

| Field of application | Number of papers, N (%) |

| Environmental pollution, N (%) | …(…%) |

| Water | …(…%) |

| Air | …(…%) |

| Food | …(…%) |

| Soil | …(…%) |

| Wastes | …(…%) |

| Environmental health hazards, N (%) | …(…%) |

| Chemical | …(…%) |

| Climate | …(…%) |

| Biological | …(…%) |

| Environmental exposure, N (%) | …(…%) |

| Monitoring | …(…%) |

| Exposure assessment | …(…%) |

| Environmental illness, N (%) | …(…%) |

| Cancer | …(…%) |

| Respiratory | …(…%) |

| Birth defects and developmental diseases | …(…%) |

| Work environment and health, N (%) | …(…%) |

| Occupational exposure | …(…%) |

| Occupational disease | …(…%) |

| … | … |

| … | … |

Table 9.

Summary statistics of the included studies on different fields of application for health services

| Field of application | Number of papers, N (%) |

| Medical specialties, N (%) | …(…%) |

| Imaging | …(…%) |

| Neurology | …(…%) |

| Public health, N (%) | …(…%) |

| Public health | …(…%) |

| Epidemiology | …(…%) |

| … | … |

| … | … |

Table 10.

Environmental health or health services data sources

| Data sources | Data types | Sources |

| Clinical data | EHRs, clinical trial data, etc | … |

| Wearable and sensors data | Personal vital signs, ECG, etc | … |

| … | … | … |

EHRs, electronic health records.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Discussion

The present study provides the first comprehensive review of big data articles with respect to both environmental health and health services. It used the 4Vs—volume, variety, velocity, and veracity—as criteria to identify whether these studies actually worked with big data and big data analytics techniques.

This study seeks to improve the quality of future big data studies in the field of environmental health and health services. The results from the present review will enable researchers to understand how big data studies should be conducted and improve the study quality. This review is the first study to determine which big data technologies have been properly applied to environmental health research.

In reviewing the field of health services, we do not impose restrictions on diseases, conditions, or healthcare domains. This review is the first study to determine how V-eligible big data studies can make a difference to the healthcare service domains.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, research papers could be too obscure in reporting their V-eligibility. Email queries with online questionnaires will be sent to the authors for confirmation of information. Secondly, the present study mainly involves descriptive statistics of the extracted information to outline how big data are used in environmental health and health services research. Advanced statistics and further hypothesis-based studies will be designed after the present study. Lastly, this study does not reflect a representational picture of how big data are used in the broad field of medicine, but only that in environmental health and health services research.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval

All data reviewed by the present study have been published and are publicly available; thus, ethics approval is not required for this study.

Publication plan

This protocol has been registered with the PROSPERO. The conduct and reporting of the review will follow PRISMA-ScR, PRISMA 2020, and SWiM. The results of this study will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed journal.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: S-wL conceived the study. All authors designed the protocol. The initial protocol of the BDRC study was drafted by PPT and ILT, and revised by YJ and S-wL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Part of the work of YJ was financially supported by the Henan Institute of Medical and Pharmacological Sciences (Grant No. 2021BP0113), the Zhengzhou University (Grant No. 32212456). Part of the work of S-wL was financially supported by the University of Edinburgh and the Shenzhen Institute of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics for Society (Grant No. 2021- ICP001).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Harper S. Environmental health. Encyclopedia of toxicology, 2014: 375–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowlton K. Globalization and environmental health. Encyclopedia of environmental health, 2019: 325–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhargava A, Pathak N, Sharma RS, et al. Environmental impact on reproductive health: can biomarkers offer any help? J Reprod Infertil 2017;18:336–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prüss-Ustün A, Wolf J, Corvalán C, et al. Diseases due to unhealthy environments: an updated estimate of the global burden of disease attributable to environmental determinants of health. J Public Health 2017;39:464–75. 10.1093/pubmed/fdw085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neira M, Prüss-Ustün A. Preventing disease through healthy environments: a global assessment of the environmental burden of disease. Toxicol Lett 2016;259:S1. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.07.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koehler K, Latshaw M, Matte T, et al. Building healthy community environments: a public health approach. Public Health Rep 2018;133:35S:35S–43. 10.1177/0033354918798809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . The top 10 causes of death, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death [Accessed 23 Mar 2021].

- 8.Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 2010;121:2331–78. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Burden of Disease Collaborators, Mokdad AH, Ballestros K, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA 2018;319:1444–72. 10.1001/jama.2018.0158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S, Wu S. Deep learning for identifying environmental risk factors of acute respiratory diseases in Beijing, China: implications for population with different age and gender. Int J Environ Health Res 2020;30:435–46. 10.1080/09603123.2019.1597836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong KS, Kim S, Kim WJ, et al. Cohort profile: beyond birth cohort study - the Korean CHildren's ENvironmental health Study (Ko-CHENS). Environ Res 2019;172:358–66. 10.1016/j.envres.2018.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(US) NRCUIoM Woolf SH, Aron L, eds. 4, public health and medical care systems. US: National Academies Press, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lurie N, Fremont A. Building bridges between medical care and public health. JAMA 2009;302:84. 10.1001/jama.2009.959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fineberg HV. Public health and medicine. Am J Prev Med 2011;41:S149–51. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeSalvo KB, Wang YC, Harris A, et al. Public health 3.0: a call to action for public health to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis 2017;14:E78. 10.5888/pcd14.170017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun X, Palm D, Grimm B, et al. Strengthening linkages between public health and health care in Nebraska. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:E100–E00. 10.5888/pcd16.180600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valaitis R, Meagher-Stewart D, Martin-Misener R, et al. Organizational factors influencing successful primary care and public health collaboration. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:420. 10.1186/s12913-018-3194-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghebreyesus TA. How could health care be anything other than high quality? Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1140–1. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30394-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valaitis RK, O'Mara L, Wong ST, et al. Strengthening primary health care through primary care and public health collaboration: the influence of intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2018;19:378–91. 10.1017/S1463423617000895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diebold FX. On the origin(s) and development of the term "big data". PIER Work Pap 2012:12–37. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Application-controlled demand paging for out-of-core visualization. Proceedings Visualization '97 1997;1997:24. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laney D. 3D data management: controlling data volume, velocity, and variety. Application Delivery Strategies by METAGroup Inc, 2001. Available: http://blogs.gartner.com/doug-laney/files/2012/01/ad949-3D-Data-Management-Controlling-Data-Volume-Velocity-and-Variety.pdf [Accessed 23 Mar 2021].

- 23.De Mauro A, Greco M, Grimaldi M. A formal definition of big data based on its essential features. Libr Rev 2016;65:122–35. 10.1108/LR-06-2015-0061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleming L, Tempini N, Gordon-Brown H. Big data in environment and human health. Oxf Res Encycl Environ Sci 2017. 10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao G, Liu X, Du H, et al. An expanding and shifting focus in recent environmental health literature: a quantitative bibliometric study. J Environ Health 2016;78:54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stieb DM, Boot CR, Turner MC. Promise and pitfalls in the application of big data to occupational and environmental health. BMC Public Health 2017;17:372. 10.1186/s12889-017-4286-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piel FB, Cockings S. Using large and complex datasets for small-area environment-health studies: from theory to practice. Int J Epidemiol 2020;49 Suppl 1:i1–3. 10.1093/ije/dyaa018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landrigan PJ, Fuller R, Acosta NJR, et al. The lancet commission on pollution and health. Lancet 2018;391:462–512. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32345-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choirat C, Braun D, Kioumourtzoglou M-A. Data science in environmental health research. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2019;6:291–9. 10.1007/s40471-019-00205-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alonso SG, de la Torre Díez I, Rodrigues JJPC, et al. A systematic review of techniques and sources of big data in the healthcare sector. J Med Syst 2017;41:183. 10.1007/s10916-017-0832-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furht B, Villanustre F. Big data technologies and applications. Springer, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Car J, Sheikh A, Wicks P, et al. Beyond the hype of big data and artificial intelligence: building foundations for knowledge and wisdom. BMC Med 2019;17:143. 10.1186/s12916-019-1382-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu P-Y, Cheng C-W, Kaddi CD, et al. -Omic and electronic health record big data analytics for precision medicine. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2017;64:263–73. 10.1109/TBME.2016.2573285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bello-Orgaz G, Jung JJ, Camacho D. Social big data: recent achievements and new challenges. Inf Fusion 2016;28:45–59. 10.1016/j.inffus.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chui KT, Liu RW, Lytras MD, et al. Big data and IoT solution for patient behaviour monitoring. Behav Inf Technol 2019;38:940–9. 10.1080/0144929X.2019.1584245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mancini M. Exploiting big data for improving healthcare services. Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society 2014;10. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dash S, Shakyawar SK, Sharma M, et al. Big data in healthcare: management, analysis and future prospects. Journal of Big Data 2019;6:54. 10.1186/s40537-019-0217-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ristevski B, Chen M. Big data analytics in medicine and healthcare. J Integr Bioinform 2018;15. 10.1515/jib-2017-0030. [Epub ahead of print: 10 May 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kruse CS, Goswamy R, Raval Y, et al. Challenges and opportunities of big data in health care: a systematic review. JMIR Med Inform 2016;4:e38. 10.2196/medinform.5359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oussous A, Benjelloun F-Z, Ait Lahcen A, et al. Big data technologies: a survey. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 2018;30:431–48. 10.1016/j.jksuci.2017.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng C-Y, Soh ZD, Majithia S, et al. Big data in ophthalmology. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol 2020;9:291–8. 10.1097/APO.0000000000000304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benke K, Benke G. Artificial intelligence and big data in public health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2796. 10.3390/ijerph15122796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kune R, Konugurthi PK, Agarwal A, et al. The anatomy of big data computing. Softw Pract Exp 2016;46:79–105. 10.1002/spe.2374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leung CK, Zhang H. Management of distributed big data for social networks. 16th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing (CCGrid), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vitolo C, Elkhatib Y, Reusser D, et al. Web technologies for environmental big data. Environ Model Softw 2015;63:185–98. 10.1016/j.envsoft.2014.10.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodríguez-Mazahua L, Rodríguez-Enríquez C-A, Sánchez-Cervantes JL, et al. A general perspective of big data: applications, tools, challenges and trends. J Supercomput 2016;72:3073–113. 10.1007/s11227-015-1501-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luo L, Li L, Hu J, et al. A hybrid solution for extracting structured medical information from unstructured data in medical records via a double-reading/entry system. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016;16:114. 10.1186/s12911-016-0357-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin S, Kaynak O. Big data for modern industry: challenges and trends [point of view]. Proc IEEE Inst Electr Electron Eng 2015;103:143–6. 10.1109/JPROC.2015.2388958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andreu-Perez J, Poon CCY, Merrifield RD, et al. Big data for health. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2015;19:1193–208. 10.1109/JBHI.2015.2450362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.L'Heureux A, Grolinger K, Elyamany HF, et al. Machine learning with big data: challenges and approaches. IEEE Access 2017;5:7776–97. 10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2696365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LaA T, Mehmood R, Benkhlifa E. Mobile cloud computing model and big data analysis for healthcare applications. IEEE Access 2016;4:6171–80. 10.1109/ACCESS.2016.2613278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hariri RH, Fredericks EM, Bowers KM. Uncertainty in big data analytics: survey, opportunities, and challenges. J Big Data 2019;6. 10.1186/s40537-019-0206-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Storey VC, Song I-Y. Big data technologies and management: what conceptual modeling can do. Data Knowl Eng 2017;108:50–67. 10.1016/j.datak.2017.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gandomi A, Haider M. Beyond the hype: big data concepts, methods, and analytics. Int J Inf Manage 2015;35:137–44. 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2014.10.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun AY, Scanlon BR. How can big data and machine learning benefit environment and water management: a survey of methods, applications, and future directions. Environ Res Lett 2019;14:073001. 10.1088/1748-9326/ab1b7d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Helland P. XML and JSON are like cardboard. Commun ACM 2017;60:46–7. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kitchin R, McArdle G. What makes big data, big data? exploring the ontological characteristics of 26 datasets. Big Data Soc 2016;3:205395171663113. 10.1177/2053951716631130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu X, Tamminen S, Su X, et al. Enhancing veracity of IoT generated big data in decision making. 2018 Ieee International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramachandramurthy S, Subramaniam S, Ramasamy C. Distilling big data: refining quality information in the era of yottabytes. ScientificWorldJournal 2015;2015:453597. 10.1155/2015/453597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Almeida F. Big data: concept, potentialities and vulnerabilities. ESJ 2018;2. 10.28991/esj-2018-01123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ozgur C, Dou M, Li Y, et al. Selection of statistical software for data scientists and teachers. J. Mod. App. Stat. Meth. 2017;16:753–74. 10.22237/jmasm/1493599200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Study of data analysis model based on big data technology. Proceedings of 2016 Ieee International Conference on Big Data Analysis 2016. 10.1109/ICBDA.2016.7509810 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shu H. Big data analytics: six techniques. Geo Spat Inf Sci 2016;19:119–28. 10.1080/10095020.2016.1182307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ 2020;368:l6890. 10.1136/bmj.l6890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tarkowski SM. Environmental health research in Europe: bibliometric analysis. Eur J Public Health 2007;17 Suppl 1:14–18. 10.1093/eurpub/ckm065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gowland A, Cook A, Heyworth J. The current status of environmental health research in Australia. Int J Environ Health Res 2012;22:362–9. 10.1080/09603123.2011.643231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clarivate Analytics . Endnote (version 20), 2020. Available: https://www.endnote.com/ [Accessed 23 Mar 2021].

- 71.Mehta N, Pandit A. Concurrence of big data analytics and healthcare: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform 2018;114:57–65. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jackson K, Bazeley P. Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. SAGE Publications Limited, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Team RDC . R: a language and environment for statistical computing, 2013. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-053447supp001.pdf (43.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-053447supp002.pdf (46.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-053447supp003.pdf (122KB, pdf)