Abstract

Factor XIII (FXIII) is a protein involved in blood clot stabilisation which also plays an important role in processes including trauma, wound healing, tissue repair, pregnancy, and even bone metabolism. Following surgery, low FXIII levels have been observed in patients with peri-operative blood loss and FXIII administration in those patients was associated with reduced blood transfusions. Furthermore, in patients with low FXIII levels, FXIII supplementation reduced the incidence of post-operative complications including disturbed wound healing. Increasing awareness of potentially low FXIII levels in specific patient populations could help identify patients with acquired FXIII deficiency; although opinions and protocols vary, a cut-off for FXIII activity of ~ 60–70% may be appropriate to diagnose acquired FXIII deficiency and guide supplementation. This narrative review discusses altered FXIII levels in trauma, surgery and wound healing, diagnostic approaches to detect FXIII deficiency and clinical guidance for the treatment of acquired FXIII deficiency.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13054-022-03940-2.

Keywords: Factor XIII, Wound healing, Acquired bleeding, Surgery, Factor XIII deficiency

Introduction

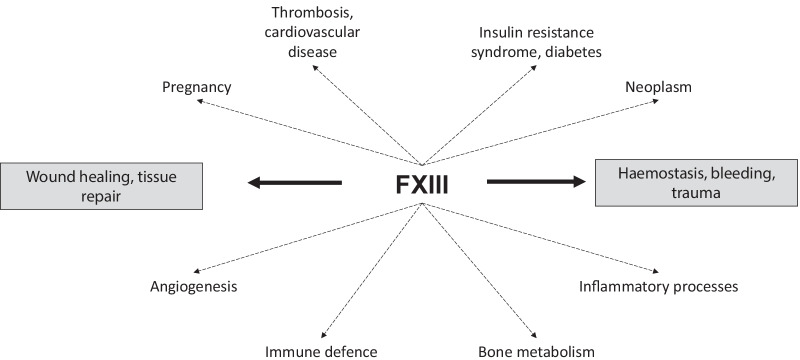

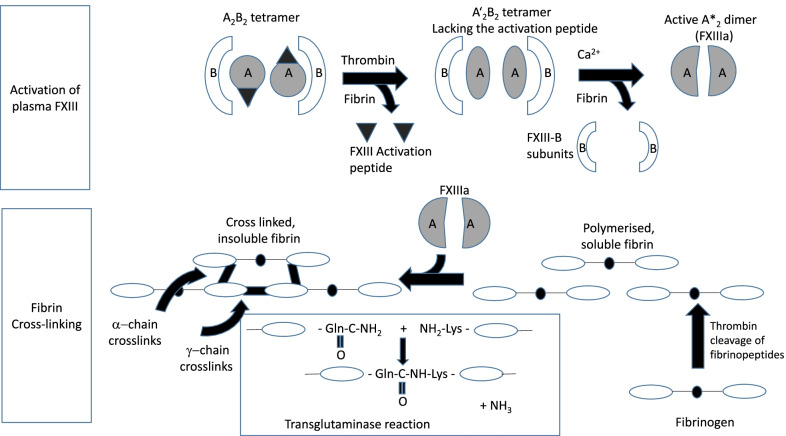

Factor XIII (FXIII) is an enzyme of the coagulation cascade which plays a key role in maintaining the functional integrity of fibrin clots [1]. Additionally, FXIII has a range of other functions, including wound healing and tissue repair (Fig. 1). FXIII circulates in plasma as a protransglutaminase comprising two catalytic A and two carrier B subunits [1–3] and intracellularly as a homodimer of constitutively active A subunits [4]. Plasma FXIII is activated by thrombin which cleaves the activation peptide from the A subunits; binding of Ca2+ ions and fibrin substrate results in a conformational change exposing the active site [1–3]. After tissue injury and fibrin clot formation, thrombin-activated FXIII catalyses covalent cross-linking of fibrin chains, stabilising the clot [1]. FXIII also exerts antifibrinolytic activity through cross-linking of α2-antiplasmin to fibrin (Fig. 2) [5–7].

Fig. 1.

Overview of FXIII functions

Fig. 2.

Activation and action of plasma FXIII (From [7], © 2012 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Reprinted with permission). FXIII circulates in plasma consisting of two catalytic A subunits and two carrier B subunits. Thrombin (Factor IIa) performs the activation step of FXIII, where thrombin cleaves the activation peptide from the A subunits before Ca2+ ions cause dissociation of the subunits. The result is a dimer of two activated FXIIIa A subunits. Presence of fibrin/fibrinogen enhances both FXIII activation steps. Following activation, FXIIIa cross-links lysine (Lys) and glutamine (Gln) residues of fibrin α- and γ-chains leading to a three-dimensional network of insoluble fibrin molecules

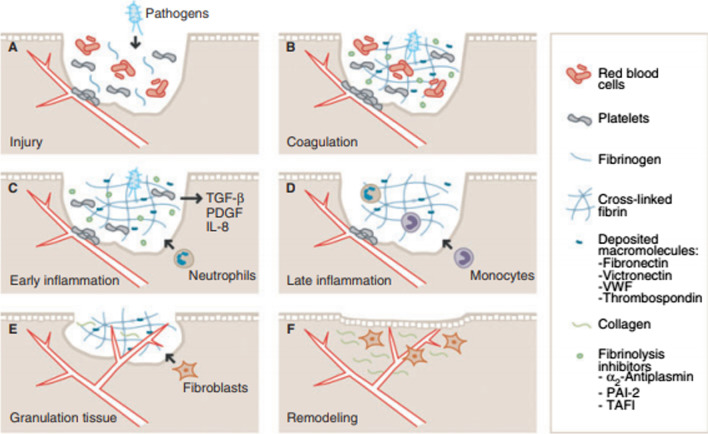

The role of FXIII in wound healing is known from preclinical studies (Fig. 3) [8, 9]. In FXIII-deficient mice, excisional wound healing was delayed compared to controls or FXIII-deficient mice receiving FXIII supplementation [10]. Moreover, FXIII cross-links fibrin to surface proteins of invading bacteria (e.g. Streptococcus [11], Staphylococcus and Escherichia [12]), trapping bacteria in the clot and reducing the risk of tissue infection [9, 11, 12]. FXIII also binds to αvβ3 integrin, resulting in VEGFR-2 activation, promotion of endothelial cell proliferation and survival, and angiogenesis [13].

Fig. 3.

The roles of plasma FXIII (pFXIII) during wound healing. a Following injury and leakage of blood constituents into the wound, pFXIII enhances aggregation of platelets to the injured endothelium, limiting exudation. b Activated pFXIII (pFXIIIa) mediates cross-linking of the deposited fibrin, structural macromolecules, fibrinolytic inhibitors, and invading pathogens. c, d Inflammatory mediators secreted by, for example, platelets and epithelium lead to recruitment of neutrophils, monocytes and additional leukocytes into the wound. FXIIIa-induced cross-linking of the provisional matrix creates the basis for their integrin-mediated interactions with the provisional matrix. This enhances cellular invasion of the wound, and stimulates leukocyte survival and proliferation. e During granulation tissue formation, fibroblasts and endothelial cells (ECs) invade the wound, facilitating collagen deposition and angiogenesis. They are guided through integrin interactions with cross-linked macromolecules in the wound, and this stimulates their migration and survival. FXIIIa stimulates angiogenesis and granulation tissue formation by mediating complex formation of endothelial αVβ3 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 on ECs. f Through the ongoing remodelling phase, the normal tissue architecture is re-established. IL, interleukin; PAI-2, plasminogen activator inhibitor-2; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TAFI, thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor; TGF-b, transforming growth factor-b; VWF, von Willebrand factor. From [9], ©2013 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Reprinted with permission)

FXIII activity varies between individuals; activities as high as 250% of the reference range have rarely been reported [14]. Inherited FXIII deficiency is graded according to FXIII activity into (1) severe: undetectable FXIII associated with spontaneous major bleeding, (2) moderate: < 30% FXIII activity associated with mild spontaneous or triggered bleeding, and (3) mild: > 30% FXIII activity, usually asymptomatic. Plasma FXIII levels in acquired FXIII deficiency are typically 30–70%, but a clear association with spontaneous bleeding complications has not been demonstrated [15]. Lower-than-reference FXIII levels prior to, or hyper-consumption during and after, trauma or surgery, may be associated with increased bleeding risk [16]. Potential causes include immune-mediated inhibition and non-immune hyper-consumption or hypo-synthesis. Acquired FXIII deficiency may likewise be idiopathic or linked to co-morbidities such as malignancies or autoimmune diseases (Table 1) [17].

Table 1.

Causes of acquired FXIII deficiency.

Adapted from Yan et al. [17]

| Pathophysiology | Associated conditions | |

|---|---|---|

| Immune | Autoantibody-mediated inhibition or rapid clearance |

Autoimmune disease Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Rheumatoid arthritis Malignancy Solid tumours Haematologic malignancy Medications Isoniazid Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) |

| Non-immune | Hyper-consumption |

Surgery Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) Inflammatory bowel disease Henoch-Schoenlein purpura (HSP) Sepsis Thrombosis Pulmonary embolism, stroke |

| Hypo-synthesis |

Liver disease Leukaemia Medications Valproate Tocilizumab |

This narrative review considers the clinical evidence for the role of FXIII in wound healing and trauma in a range of settings and provides the authors’ opinion on diagnosis and treatment of acquired FXIII deficiency. The diagnosis and treatment of congenital and immune-acquired FXIII deficiency, use of FXIII supplementation to correct defective cellular FXIII function, and use in paediatric patients, are beyond the scope of this review.

Literature search

Due to limited availability of level 1 evidence and the variable nature of data reported, with differing outcome measures, a formal approach using PICO and GRADE methodology was not considered appropriate. Therefore, our aim was to summarise available clinical evidence. A literature search was conducted in PubMed on 21 January 2021. The search term factor XIII was combined with: trauma; complication; postpartum haemorrhage; cancer AND surgery; cardiac surgery; infection; sepsis; fistula; ulcer; burn; wound healing; diagnosis AND (test OR assay); (guidelines OR guidance OR recommendations OR algorithm). Exclusion criteria included: congenital FXIII deficiency; immune-mediated FXIII deficiency (with auto-antibodies); other clinical settings; fibrin glue; non-clinical studies; reviews; articles in a language other than English or German; full text not available.

Overall, 789 articles were retrieved, including 129 duplicates, leaving 660 articles. Following screening to identify relevant clinical studies with sufficient patient numbers and adequate reporting of results, 563 articles were excluded (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). The authors reviewed all 97 resulting articles to identify 18 papers (Table 2) [18–35].

Table 2.

Summary of key papers involving clinical experience with FXIII

| References | Year | Indication | Study type | Patients | Protocol | Key outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial 1 | Baer et al. [18] | 1980 | Wound healing (surgery) | Randomised controlled trial | 95 patients undergoing major abdominal or vascular surgery or patients with risk factors for development of wound healing disturbances |

15 patients had FXIII levels within reference ranges whilst 80 patients had a pre- or post-operative deficit in FXIII (< 87.5%) and were randomised to receive either FXIII supplementation or no supplementation according to the formula: FXIII units for supplementation = 0.5 × body weight x FXIII deficit (%) |

All patients showed a post-operative decrease in FXIII levels, the incidence of wound healing disturbance correlated with decreased FXIII levels, severity of FXIII decrease correlated with severity of surgical intervention and supplementation with FXIII concentrate reduced the incidence of post-operative surgical complications FXIII supplementation: 10 wound healing disorders/38 patients No supplementation: 19 wound healing disorders/42 patients |

| Trial 2 | Chaoui et al. [19] | 1999 | Wound healing (surgery) | Randomised controlled trial | 100 patients after surgery of head/neck tumours |

1250 IU FXIII on post-operative day 2, 4 and 6 or no FXIII supplementation Results are displayed for patients with high-risk for wound healing disorders (17 controls, 20 FXIII supplementation) |

FXIII plasma levels not predictive of wound healing disturbances. In FXIII group, plasma levels increased by ~ 30% (not significant) 10/20 (50%) of patients had primary wound healing compared to 7/17 (35%) controls |

| Trial 3 | Fujita et al. [20] | 2006 | Wound healing (surgery) | Single-centre, open-label study | 17 patients with anastomotic leaks (n = 16) or non-healing fistulas (n = 1) after gastrointestinal surgery who had serum protein and albumin levels within reference ranges but low FXIII activity after the resolution of post-operative acute inflammation | A 240 U dose of FXIII concentrate was administered intravenously for 5 days | Improvement following treatment was observed in 15 cases (88.2%). FXIII activity increased to > 70% of the reference range in 11 cases (64.7%) but was 40–70% of the reference range in six cases (35.3%). Levels of plasma EGF and TGF-β increased in patients with improvement but did not change in patients without improvement |

| Trial 4 | Gerlach et al. [21] | 2000 | Wound healing (surgery) | Retrospective study | 1264 patients underwent intracranial operations | FXIII testing was carried out post-operatively in 34 patients in whom coagulopathies were suspected despite platelets, fibrinogen, prothrombin and partial thromboplastin time being within the reference ranges | Of the 1264 patients, a total of 20 patients (1.6%) had a post-operative haemorrhage; of the 34 patients with suspected coagulopathies and FXIII post-operative testing, 11 suffered a major post-operative haemorrhage. Levels of FXIII were within the reference ranges (> 60%) in 26 of the 34 patients whilst FXIII deficiency (< 60%) was found in eight patients. All eight patients with FXIII deficiency had a major post-operative haemorrhage whilst of the remaining 26 patients with FXIII levels within the reference ranges only three had a post-operative haemorrhage (p < 0.00001) |

| Trial 5 | Gierhake et al. [22] | 1974 | Wound healing (surgery) | Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 300 patients undergoing abdominal surgery | Patients received one dose of FXIII or placebo, 1 day pre-operatively and on day 1 to 3 post-operatively; the first 200 patients received 500 IU FXIII or placebo at each time-point and the next 100 patients received 750 IU FXIII or placebo | 7.8% of patients in the FXIII group and 18.5% of patients in the placebo group developed wound healing disturbances (statistically significant, p < 0.01), post-operative FXIII levels fell further in the placebo group (62.3%) compared to the FXIII group (88.7%) |

| Trial 6 | Muto et al. [23] | 1997 | Wound healing (surgery) | Multi-centre, open, randomised controlled study | 310 patients: 196 with non-healing post-operative wounds and 114 with fistulae | Patients had FXIII levels < 70%, each received 1500 IU FXIII concentrate over 5 days or no treatment (controls) | In non-healing post-operative wounds and fistulae, the rate of improvement was significantly higher for patients treated with FXIII compared to controls (non-healing wounds 72% vs 32%; p < 0.01; fistulae 69% vs 38%, p < 0.01) |

| Trial 7 | Mishima et al. [24] | 1984 | Wound healing (surgery) | Controlled, randomised, open trial | 71 patients with post-operative wound healing disturbance e.g. fistulae, dehiscence of skin wounds without improvement after at least 14 days and with FXIII plasma levels < 70% at 3–5 days prior to inclusion |

5 days after inclusion subjects were randomised to three groups: Control: no factor XIII supplementation; Group 1: FXIII 750 IU/day on days 6, 7 and 8; Group 3: FXIII 1500 IU/day on days 6, 7 and 8 |

Improvements occurred when FXIII plasma levels were > 70% whilst subjects with < 50% FXIII deteriorated; rate of relevant general improvement of wounds in blind evaluation: 61.9% (750 IU FXIII, Group 1); 76.2% (1500 IU FXIII, Group 2); 10.5% (no FXIII, control) |

| Trial 8 | Schramm et al. [25] | 1982 | Wound healing (surgery) | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study | 80 patients with cancer surgery of stomach, colon and rectum of which 55 patients were evaluable | Patients were randomised to receive either 1250 IU of FXIII immediately post-operatively and on post-operative days 2 and 4 or corresponding placebo | Overall, in the placebo group, 48.1% of patients had abdominal wall dehiscence or rupture compared to 35.7% in the FXIII group, a difference which was not statistically significant |

| Trial 9 | Takeda et al. [26] | 2018 | Wound healing (surgery) | Randomised controlled trial | 50 patients with post-operative pancreatic fistula | Patients randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive FXIII concentrate the day after randomisation or a control group that received no FXIII concentrate within 2 weeks | There was no significant difference in the duration of drain placement between groups, early administration of exogenous FXIII does not facilitate the healing of post-operative pancreatic fistula |

| Trial 10 | Herouy et al. [27] | 2000 | Wound healing (ulcers) | Randomised, double blind, age-matched study | 30 patients with venous leg ulcers that had been resistant to therapy and had existed for a mean of 1.5 years: 15 patients underwent FXIII treatment and 15 patients received placebo | Beside compression bandage therapy, wound surfaces were treated once daily with FXIII or with placebo (isotonic sodium chloride solution). Ulcers were debrided and topical treatment started 24 h later | A significant decrease in the wound surface was observed after topical treatment with FXIII compared with placebo with total closure of venous leg ulcers achieved within a mean of 6 weeks. A significant reduction in fibrinolytic activity was also observed after 96 h of FXIII treatment whilst the placebo group showed the typical activity of venous leg ulcers with no significant decrease in fibrinolytic activity |

| Trial 11 | Wozniak et al. [28] | 2001 | Wound healing (chronic leg ulcer) | Open study | 54 patients with ulcers of the lower extremity | Initial regimen was 2 × 250 IU FXIII in the first week; however, this was reduced to 1 × 250 IU FXIII in the first week, followed by 250 IU every 2 days in the second week and 250 IU every 3 days from the third week up to 6 weeks | Patients with venous ulcers due to post-thrombotic syndrome admitted after infections, pain or unsuccessful treatment required FXIII treatment in hospital for 3–15 weeks and could then continue out-of-hospital treatment |

| Trial 12 | Peschen et al. [29] | 1998 | Wound healing (chronic leg ulcer) | Placebo-controlled clinical study | 24 patients were placed into 2 groups each made up of 12 patients with leg ulcers > 1000 mm2 or < 1000 mm2 | In each group 8 of 12 patients were given additional topical treatment of FXIII twice daily for 10 days (treatment groups) | Results demonstrate that locally applied FXIII promotes wound healing of more acute, smaller venous leg ulcers (< 1000 mm2); it is suggested that FXIII is inactivated rapidly after topical application since immunohistochemical staining of FXIII showed no significant difference before and after therapy |

| Trial 13 | Erlebach et al. [30] | 1999 | Wound healing (burns) | Treatment report | 93 patients with burns between 41 and 89% of body surface area | Patients with 41–60% burn area (n = 87) received 1250–2500 IU FXIII on the day of surgery and on the first two post-operative days after each surgery; patients with 61–89% burn area (n = 6) received 1250–2500 IU FXIII on the day of surgery and 1250 IU FXIII daily until wound healing was complete | FXIII at admission 61–78%, at day of first surgery (approx. day 3): 17–37%; Perceived benefits of treatment with FXIII were reduced blood loss and a lesser need for transfusion in addition to accelerated epithelial regrowth especially of skin harvesting areas |

| Trial 14 | Godje et al. [31] | 2006 | Surgery | Double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial | 75 patients, after coronary surgery with extracorporeal circulation | 2500 U FXIII, 1250 U FXIII and a placebo given to 25 patients each | FXIII administration decreases post-operative blood loss and the level of blood transfusion after coronary surgery; however, administration is only advantageous if plasma levels are below the reference ranges |

| Trial 15 | Karkouti et al. [32] | 2013 | Surgery | Double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial | 409 cardiac surgery patients at moderate risk for transfusion | 17.5 IU/kg (n = 143), 35 IU/kg (n = 138) or placebo (n = 128) after cardiopulmonary bypass | Administration of FXIII levels after cardiac surgery restored levels in patients at moderate risk for transfusion to pre-operative levels; replenishment of FXIII levels had no effect on transfusion avoidance, transfusion requirements or need for re-operation |

| Trial 16 | Korte et al. [33] | 2009 | Surgery | Double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial | 22 patients were evaluated after elective gastrointestinal cancer surgery | FXIII (30 U/kg) or placebo | In patients at increased risk for intra-operative bleeding, clot firmness was decreased by ~ 8% in patients that received FXIII and for patients in the placebo group it was reduced by 38% (p = 0.004); patients at high risk for intra-operative blood loss demonstrated reduced loss of clot firmness when FXIII was given early during surgery |

| Trial 17 | Levy et al. [34] | 2009 | Surgery | Randomised controlled trial | 35 patients were randomised to FXIII and 8 to placebo after cardiopulmonary bypass | 11.9, 25, 35 or 50 IU/kg FXIII or placebo in a 4:1 ratio | In the FXIII group, dosing with 25–50 IU/kg restored FXIII levels to those seen pre-operatively with a tendency towards overshoot in the 50 IU/kg group and for post-operative FXIII replenishment 35 IU/kg may be the most appropriate dose |

| Trial 18 | Gerlach et al. [48] | 2002 | Surgery | Prospective study | 876 patients undergoing 910 neurosurgical procedures who developed 39 post-operative intracranial haematomas (4.3% of surgeries) | Prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, platelet count, fibrinogen, and FXIII activity were tested in each patient pre- and post-operatively | 13/39 (33.3%) patients with post-operative haematoma had post-operative FXIII < 60% vs. 61/867 (7%) without (p < 0.01). The relative risk for a post-operative haematoma was increased 6.4-fold in patients with post-operative FXIII deficiency. The risk was increased 12-fold in patients who also had post-operative decreases in fibrinogen levels (< 1.5 g/L) and 9-fold in patients with platelet count < 150 × 109/L and FXIII < 60% |

Clinical evidence

Trauma

Patients who have sustained severe trauma are at increased risk of trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC), usually triggered by acute trauma-haemorrhagic shock (THS). THS leads to reduced blood volume, resulting in tissue hypoxia and risk of organ damage. Therefore, early identification and intervention is critical to prevent widespread organ damage [7, 31]. TIC is characterised by activation and consumption of clotting factors (notably fibrinogen), dilutional coagulopathy, hyperfibrinolysis and inflammation [36, 37]. In addition, significant loss and consumption of FXIII has been reported [36, 37]. Preclinical studies in models of THS and experimental burn have suggested that FXIII supplementation may ameliorate THS-induced organ failure [38, 39]. Furthermore, in preclinical studies using an experimental haemorrhagic shock model high doses of FXIII promoted effective haemostasis for trauma-associated coagulopathy in vitro and in vivo [40, 41]. FXIII also improved clot adhesion in wounds in a standardised bleeding model [41]. In vitro, FXIII improved clot strength and increased resistance to hyperfibrinolysis (measured by rotational thromboelastometry [ROTEM]) and significantly decreased bleeding and prolonged survival in vivo [42].

Although use of FXIII concentrate has been investigated clinically in major trauma patients, no double-blind, randomised trials could be identified. FFP contains approximately 1.2 U/mL of FXIII [43], Administration of FXIII concentrate (15 U/kg body weight) to major trauma patients with ongoing bleeding and FXIII activity < 60% as part of a goal-directed transfusion algorithm, led to a reduction in the proportion of patients requiring massive transfusions and an overall reduction of red blood cell (RBC) and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfusion [44]. However, with changes to acute trauma care over time, including novel goal-directed coagulation management strategies and modified surgical approaches, the specific contribution of FXIII to improved outcomes could not be confirmed [44]. FXIII administration was also part of coagulation factor (CF)-based algorithms guided by viscoelastic tests for reversal of TIC, where use of CF concentrates was superior in reducing organ failure, reversal of TIC and transfusion requirements compared to FFP only [45, 46]. In the RETIC trial [45], 27/50 patients (54%) in the CF group had plasma FXIII < 60% and either diffuse microvascular bleeding or massive bleeding requiring transfusion of > 3 U RBCs/hour and received FXIII concentrate (20 IU/kg) with every other fibrinogen dose. In the FFP group, 11 patients (25%) received FXIII as rescue therapy. In the Swiss observational study, application of a target haematocrit range was associated with increased use of FXIII (15/172 patients [9%] vs. 6/172 [3.5%], p = 0.004), with a reduction in the proportion of patients requiring RBC transfusions (11.6% vs. 29.7% of patients, p < 0.001) and the number of transfusions [46]. In both studies, FXIII was part of an algorithmic approach and it was not possible to identify the specific contribution of individual components.

Opinion and experiences differ regarding the timing and potential effects of FXIII deficiency in major trauma. One view is that FXIII deficiency may be a late (typically 2–3 weeks) complication of major trauma due to hepatic dysfunction; another is that FXIII deficiency occurs 3–7 days post-trauma, particularly in cases of major surgery. However, ~ 30% of trauma patients exhibit FXIII activity < 60% on admission with a clear association to the degree of blood loss suggesting FXIII activity decreases shortly after trauma [45].

Consequently, evaluation of FXIII activity should be conducted following trauma. Depending on clinical risk factors, magnitude of the traumatic impact and incidence of further bleeding, FXIII measurements may be required every 5–7 days or at shorter intervals in settings with higher dynamics and turnover, e.g. major trauma or severe burns. Conversely, lower risk patients may require less frequent monitoring as plasma FXIII has a half-life of 11–14 days [47].

Surgery

An association between lower FXIII levels and peri-operative blood loss has been reported [16, 48, 49]. FXIII deficiency is associated with post-operative haemorrhagic events and requirement for post-operative transfusion [21, 35, 50]. Observational data from neurosurgical patients identified a post-operative FXIII level < 60% as an independent risk factor for post-operative intracranial bleeding [21, 35]. In a retrospective study of 34 patients with suspected coagulopathy and recorded post-operative FXIII levels, eight patients had FXIII levels < 60% and all had a major post-operative haemorrhage compared to 3/26 patients with FXIII levels within reference ranges; this difference was highly significant [21]. In a prospective study post-operative haematoma occurred in 39/910 neurosurgical procedures. Thirteen patients (33.3%) with post-operative haematoma had post-operative FXIII levels < 60% compared with 61 (7%) without haematoma, a relative risk of 6.4 [35].

A retrospective study evaluated whether FXIII along with fibrinogen or platelet count affected the probability of intra-operative RBC transfusions in patients during non-cardiac surgery. In total, 443/1023 patients received RBCs; FXIII deficiency (FXIII level < 70%) was associated with a significantly increased probability of RBC transfusion, as was platelet count but not fibrinogen depletion [51]. An observational study of CFs after coronary artery bypass graft demonstrated that pre- and post-operative FXIII activity and plasma fibrinogen levels at two hours after surgery may inversely correlate with post-operative blood loss [50]. Furthermore, in 49 post-surgical patients with suspected acquired FXIII deficiency, FXIII levels < 50% were identified in 55% of patients. FXIII deficiency was associated with decreased haematocrit, increased transfusion requirement and delayed bleeding [52]. Conversely, treatment with FXIII reduced post-operative blood loss and blood transfusion after coronary surgery in patients where post-medication levels of FXIII ≥ 70% could be achieved [31]. FXIII administration was only beneficial if plasma levels were below reference ranges and it was suggested that plasma levels should be measured prior to FXIII administration [31].

A more recent prospective case control study evaluated potential risk factors for surgical re-exploration due to bleeding after elective cardiac surgery. Multivariate analysis revealed reduced FXIII activity was independently associated with surgical re-exploration [53]. Reduced post-operative FXIII activity was also significantly associated with increased 30-day mortality in univariate, but not multivariate, analysis [53]. Finally, in a prospective, randomised, proof-of-concept study in patients undergoing surgery for gastrointestinal cancer who were at risk of increased intra-operative blood loss (preoperative fibrin monomer > 3 µg/L), reductions in the secondary endpoints of blood loss and fibrinogen consumption were observed in patients who received FXIII [33].

Data from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) using recombinant FXIII (rFXIII) suggest that peri-operative FXIII supplementation has a varying impact on transfusion requirements; however, these trials were either unsuitable to evaluate FXIII or produced non-significant results [32–34]. In a study primarily designed to assess the safety and pharmacokinetics of rFXIII, there was less chest tube drainage in patients who received rFXIII following cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) compared to placebo [34]. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial involving 409 patients undergoing CPB surgery, rFXIII administration had no effect on blood transfusion requirement or re-operation compared to placebo; however, the cohort was limited to patients with a moderate risk for transfusion and transfusion avoidance was higher than anticipated with mean FXIII levels around 80% prior to drug administration. The efficacy of rFXIII may be better demonstrated in patients with a higher transfusion risk, in those with severe FXIII deficiency, or instead of antifibrinolytic drugs [32].

In post-operative intensive care patients with low FXIII and high fibrinogen levels, in vitro supplementation of FXIII to supraphysiological levels increased clot firmness and stability, and accelerated clot formation [42].

Surgical wound healing

Prolonged reduction in plasma FXIII levels following surgery has been demonstrated [18, 23, 54, 55] and FXIII supplementation reduced the incidence of post-operative complications including disturbed wound healing [18, 23–25]. In 70% of patients with prolonged air leak following pulmonary lobectomy, air leaks resolved when FXIII was administered for five days. In patients who responded, post-operative FXIII levels were lower compared to those who did not respond to administration of FXIII indicating two potential mechanisms for prolonged air leak; one of which is related to FXIII consumption [54]. In an open-label, randomised study in 310 patients with disturbed post-operative wound healing or fistulae after surgery of the gastrointestinal tract, FXIII treatment for five days reduced wound size compared to controls [23]. Similarly, in an open-label study of 71 patients with post-operative wound healing disturbances, wound size at day 15 remained largely unchanged from baseline in controls, but decreased in the FXIII-treated groups; findings were similar for patients with fistulae [24]. In a double-blind placebo-controlled study of 55 patients undergoing laparotomy, 35.7% of patients in the FXIII group had wound healing complications compared to 48.1% of controls. This difference was not statistically significant, potentially due to the relatively small sample size [25].

Non-surgical wounds

FXIII deficiency has also been associated with impaired healing of non-surgical wounds, such as leg ulcers [27–29, 56–58], burns [30, 59], and pressure sores [60]. Topical treatment of venous leg ulcers with FXIII has shown promising results in small trials and case studies [27–29, 56, 57]. In a study of 54 patients with ulcers of the lower extremities, including a subgroup with post-thrombotic ulcus cruris venosum that had pre-existed for a mean of 11.8 months, in-hospital treatment with FXIII for a mean of 3.15 weeks permitted out-of-hospital management, and skin transplantation could be accomplished in many cases [28]. Furthermore, locally applied FXIII promoted healing of acute, small leg ulcers (< 1000 mm2) in a trial of 24 patients [29]. Similarly, a randomised, double-blind, age-matched study in patients with venous leg ulcers confirmed a faster healing rate and significantly reduced lesional fibrinolytic activity with topical FXIII treatment compared to controls [27].

Refractory wounds and fistulae

In line with the role of FXIII in limiting the spread of invading bacteria and promoting wound healing, FXIII levels were reduced in patients with post-operative non-healing fistulae or anastomotic leaks [20, 24, 61]. Furthermore, the use of FXIII concentrate has been shown to be beneficial for the treatment of post-operative wounds [20, 24, 61], as well as serious skin infections [62]. Thus, in a study evaluating FXIII treatment for post-operative, refractory wounds, improvements occurred in patients with FXIII levels > 70% while deterioration was observed in those with FXIII levels < 50% [24]. In a patient with decreased FXIII activity and multiple intractable enterocutaneous fistulae, FXIII administration after further surgery resulted in no fistula recurrence or other complications [61]. In another study, FXIII administration increased levels to > 70% in 64.7% of patients with anastomotic leaks or fistulae and low plasma FXIII activity levels; improved wound healing was associated with increased levels of plasma epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-β, and it was suggested that FXIII may accelerate wound healing through increasing circulating levels of growth factors [20].

Conversely, other studies have not demonstrated benefits from FXIII administration. In a single-centre study of 43 patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy, post-operative morbidity, including pancreatic fistulae, were comparable between patients with < 70% or ≥ 70% FXIII activity [48]. Similarly, in an RCT in 50 patients with post-operative pancreatic fistulae and FXIII levels ≤ 70%, early administration of FXIII concentrate did not facilitate fistulae healing [26].

Burns

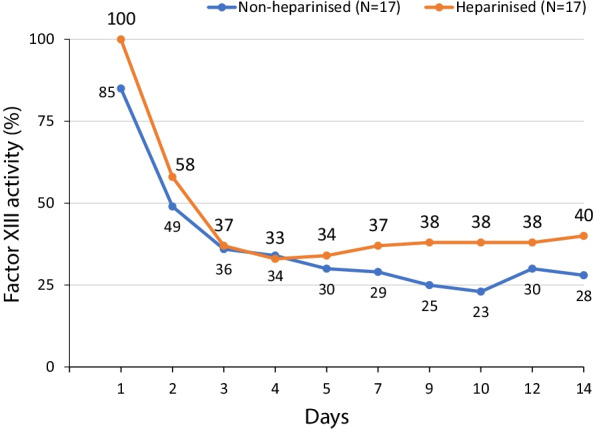

In 34 patients with severe burns (20–64% total body surface), there was a rapid fall of FXIII activity to ~ 35% during the first three days and this level remained < 50% until day 14 [59] (Fig. 4), suggesting that bleeding episodes, disturbed re-epithelialisation of mesh-graft harvesting areas and other clinical problems may be likely under these circumstances. Two studies have reported reduced transfusion requirements with FXIII supplementation in burn patients [30, 63]; the earlier study also reported reduced blood loss and accelerated epithelial growth, particularly around skin harvesting areas [30].

Fig. 4.

Factor XIII activity in non-heparinised and heparinised patients with severe burns. From [59] (©1977 Der Chirurg, adapted with permission). FXIII activity was measured daily from admission to general ward transfer in patients with severe burns (20–64% of body surface, N = 34). A rapid fall in FXIII activity was observed in the first three days in both heparinised and non-heparinised patients, where activity remained below 50% during 14-day follow-up for all patients

Diagnosis

Abnormal bleeding may imply FXIII deficiency, but diagnosis requires specific laboratory tests [64]. Importantly, in cases of FXIII deficiency, routine coagulation tests such as prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and thrombin time remain within their reference ranges, so it is essential to apply specific tests to assess FXIII levels [64, 65].

In 2011, the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) recommended an algorithm for diagnostic testing to classify and grade congenital and acquired FXIII deficiencies [64]. In clinical practice standard activity tests based on transglutaminase activity (ammonia release and amine incorporation assays), isopeptidase activity or direct quantitative antigen assays are most commonly available [65]. Clot solubility tests may also be used, despite a lack of standardisation and inability to measure less prominent FXIII deficiency. Autoantibody assays may be performed if FXIII activity is below the reference range [65–67].

Clot strength and resistance to hyperfibrinolysis in vitro can be measured by ROTEM [36, 42] but direct measurement of FXIII by ROTEM has not, to-date, been possible [68, 69]. A study in cardiac surgery patients reported a close correlation between fibrinogen levels and FXIII and further suggested FXIII levels could be estimated using MCF-FIBTEM measured by ROTEM [70]. In addition, an unpublished study combined in vitro observation and FXIII measurement by ROTEM (EXTEM and INTEM) with a prospective evaluation in patients with severe trauma (personal communication C. Kleber). This approach requires confirmation and has not yet reached widespread clinical application.

Clinical guidelines

Clinical guidelines for the management of acquired FXIII deficiency are limited. However, recommendations for the use of FXIII concentrate are covered in guidelines for the management of bleeding during surgery [71–73], postpartum haemorrhage [74], and following trauma [75]. Blood conservation guidelines from the US Society of Thoracic Surgeons state that FXIII concentrate may be considered after CPB in bleeding patients when other routine blood conservation measures prove unsatisfactory [71]. The European Society of Anaesthesiology recommends administration of FXIII concentrate (30 IU/kg) in cases of peri-operative bleeding and FXIII activity < 30% [72]. In contrast, the ISTH recommends against the use of FXIII concentrate for management of peri-operative bleeding, on the basis that the benefits remain unproven in the context of acquired FXIII deficiency [73]. The European guideline for the management of major bleeding following trauma suggests including FXIII monitoring in coagulation support algorithms and supplementation in bleeding patients with a functional FXIII deficiency [75]. However, there is no consensus on what level of FXIII indicates FXIII deficiency or when FXIII concentrate should be prescribed in these settings.

Discussion

The limited inclusion of FXIII therapy into critical care guidelines suggests low awareness of potential FXIII deficiency in acquired bleeding and wound healing. Although data from RCTs remain limited, a considerable body of clinical evidence and expert knowledge has been accumulated over recent years on the use of FXIII in acquired bleeding and wound healing that could guide current treatment approaches. Due to the limitations of the published literature, we were unable to apply full systematic methodologies to evaluate the literature. However, every effort was made to accurately represent the data and the limitations therein. A supplementary search of clinicaltrials.gov and EU Clinical Trials register (conducted November 2021) found no ongoing clinical trials or substantive studies not already identified by our literature review.

It is the authors’ opinion that diagnostic measures concerning FXIII levels in the peri-operative setting are underrepresented and that there is less FXIII supplementation than current evidence would support. Increasing awareness of FXIII testing could help identify patients with acquired FXIII deficiency. Current recommendations for the management of FXIII deficiency are largely based on data from patients with congenital FXIII deficiency, which may not be transferable to patients with acquired FXIII deficiency in bleeding and wound healing. It is also not clear whether differences in the pathophysiological response to acute soft tissue trauma compared to elective surgery could affect the response to FXIII therapy. Therefore, tests should always be interpreted in the context of the clinical course of the disorder, concomitant diseases, operative/surgical trauma and bleeding characteristics and phenotype. In cases of ongoing bleeding with global test results and platelet counts within reference ranges, FXIII deficiency should be considered and a quantitative functional FXIII activity test performed. Although opinions and protocols may vary, a cut-off for FXIII activity of < 50–70% may be appropriate to diagnose acquired FXIII deficiency.

Current international treatment guidelines offer limited and seemingly contradictory recommendations regarding the use of FXIII in acquired bleeding and intensive care and some focus only on its use when congenital deficiency is present. Prices of FXIII products vary across Europe according to the source (plasma derived/recombinant) and licensed indications. However, costs are similar to other coagulation factor concentrates. Despite lack of consensus in clinical guidelines, the studies summarised in this narrative review indicate it may be beneficial to administer FXIII to patients with low FXIII levels. In the setting of active bleeding, prolonged wound healing, substantial soft tissue injury, or persistent infection/bacteraemia treatment with FXIII should be considered only if reduced activity is detected.

Regarding safety, FXIII is widely used to treat FXIII deficiency with few adverse events reported. The most common adverse events reported during use of Factor XIII Concentrate (Fibrogammin/Corifact; CSL Behring GmbH, Marburg, Germany) are allergoid-anaphylactoid reactions (e.g. generalised urticaria, rash, fall in blood pressure, dyspnoea) and rise in temperature, reported at an incidence of between 1/10,000 and 1/1000 [76]. The safety of Factor XIII Concentrate has also been confirmed through > 20 years of pharmacovigilance data, with a low risk of thromboembolic events reported over this period [77]. Although formal controlled trials in trauma are limited, studies in patients with acquired FXIII deficiency due to traumatic injury or post-operatively have indicated a good safety profile [21, 23, 24, 26, 28, 31, 32, 34]. Further information on the safety of FXIII in patients with severe trauma would be useful, although challenging to obtain due to the devastating nature of trauma and the multi-modal treatment employed.

Future directions

FXIII is a haemostatic protein that stabilises blood clots and has a range of functions in wound healing, tissue repair, haemostasis, bleeding and trauma. A recent review has described three pools of FXIII within the circulation, in plasma, and within the cellular compartments of platelets and monocytes/macrophages, providing additional insights into the complex roles of FXIII in these physiological processes [78]. Although beyond the scope of this review, studies have indicated that FXIII levels/activity are impaired before and during extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation [79–81]. Moreover, acquired coagulopathy and reduced FXIII levels have been reported in patients with COVID-19 [82–84].

There is also increasing evidence that FXIII may be of use in areas beyond the scope of this narrative review, e.g. bone healing. Preclinical experimental models have demonstrated a positive effect during early stages of bone healing, with increased FXIII levels correlating with an increase in tensile strength and number of newly formed osteons [85, 86]. Studies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease suggest FXIII activity may vary according to disease activity [87–91] with initial clinical data suggesting a potential role for FXIII therapy – although results are conflicting [92–97].

There remain substantial research gaps and opportunities to further explore the role and use of FXIII in acquired bleeding and wound healing. Topical treatment as well as systemic application of FXIII in the impaired healing of non-surgical wounds merits further research and an RCT in this field would be of great interest. Further clinical studies are also vital in major abdominal surgery, septic infection and burn care to clarify the function of FXIII. Additionally, case series to identify risk factors for acquired FXIII deficiency would be of value, as would a prospective, multi-centre study with FXIII substitution dependent on activity cut-off, in patients that have bacteraemia and in trauma patients to leverage the knowledge on anti-infective properties. If such trials were conducted, a formal meta-analytical approach would be useful to confirm the utility of FXIII in specific clinical settings.

Conclusions

In patients with low plasma FXIII levels, FXIII supplementation reduced the incidence of post-operative complications including delayed haemorrhage and disturbed wound healing. Several studies with positive outcomes have used ~ 60–70% activity as a trigger for FXIII supplementation. Increasing the awareness of FXIII testing could help identify patients with acquired FXIII deficiency in cases of acquired bleeding and delayed wound healing. Creating in-house standard operating procedures for the diagnosis and treatment of acquired FXIII deficiency could be highly beneficial.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Literature search summary.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CF

Coagulation factor

- CPB

Cardiopulmonary bypass

- FFP

Fresh frozen plasma

- FXIII

Factor XIII

- rFXIII

Recombinant FXIII

- RBC

Red blood cell

- RCT

Randomised controlled trial

- ROTEM

Rotational thromboelastometry

- THS

Trauma-haemorrhagic shock

- TIC

Trauma-induced coagulopathy

Authors' contributions

CK, AS, SC, MO, K-MT, JH, FCFS, IB, DF, MM, HS, and MW were involved in the conception and design of the literature search. CK and AS reviewed the literature and provided recommendations of studies to include; SC, MO, K-MT, JH, FCFS, IB, DF, MM, HS, and MW reviewed and agreed the final selection of relevant literature. All authors agreed manuscript content and provided critical review and revisions to the manuscript during its development. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Medical writing assistance was provided by Meridian HealthComms Ltd in accordance with good publication practice (GPP3), funded by CSL Behring.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Muszbek L, Bereczky Z, Bagoly Z, Komáromi I, Katona É. Factor XIII: a coagulation factor with multiple plasmatic and cellular functions. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(3):931–972. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yee VC, Pedersen LC, Le Trong I, Bishop PD, Stenkamp RE, Teller DC. Three-dimensional structure of a transglutaminase: human blood coagulation factor XIII. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(15):7296–7300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souri M, Osaki T, Ichinose A. The non-catalytic B subunit of coagulation factor XIII accelerates fibrin cross-linking. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(19):12027–12039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.608570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell JL, Mutch NJ. Let's cross-link: diverse functions of the promiscuous cellular transglutaminase factor XIII-A. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(1):19–30. doi: 10.1111/jth.14348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraser SR, Booth NA, Mutch NJ. The antifibrinolytic function of factor XIII is exclusively expressed through α2-antiplasmin cross-linking. Blood. 2011;117(23):6371–6374. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-333203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rijken DC, Abdul S, Malfliet JJ, Leebeek FW, Uitte de Willige S. Compaction of fibrin clots reveals the antifibrinolytic effect of factor XIII. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(7):1453–1461. doi: 10.1111/jth.13354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroeder V, Kohler HP. New developments in the area of factor XIII. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(2):234–244. doi: 10.1111/jth.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inbal A, Dardik R. Role of coagulation factor XIII (FXIII) in angiogenesis and tissue repair. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2006;35(1–2):162–165. doi: 10.1159/000093562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soendergaard C, Kvist PH, Seidelin JB, Nielsen OH. Tissue-regenerating functions of coagulation factor XIII. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(5):806–816. doi: 10.1111/jth.12169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inbal A, Lubetsky A, Krapp T, Castel D, Shaish A, Dickneitte G, et al. Impaired wound healing in factor XIII deficient mice. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94(2):432–437. doi: 10.1160/TH05-04-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loof TG, Mörgelin M, Johansson L, Oehmcke S, Olin AI, Dickneite G, et al. Coagulation, an ancestral serine protease cascade, exerts a novel function in early immune defense. Blood. 2011;118(9):2589–2598. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z, Wilhelmsson C, Hyrsl P, Loof TG, Dobes P, Klupp M, et al. Pathogen entrapment by transglutaminase—a conserved early innate immune mechanism. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(2):e1000763. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dardik R, Loscalzo J, Eskaraev R, Inbal A. Molecular mechanisms underlying the proangiogenic effect of factor XIII. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(3):526–532. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000154137.21230.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ariens RA, Kohler HP, Mansfield MW, Grant PJ. Subunit antigen and activity levels of blood coagulation factor XIII in healthy individuals. Relation to sex, age, smoking, and hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2012–2016. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.8.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswas A, Ivaskevicius V, Thomas A, Oldenburg J. Coagulation factor XIII deficiency. Diagnosis, prevalence and management of inherited and acquired forms. Hamostaseologie. 2014;34(2):160–166. doi: 10.5482/HAMO-13-08-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korte W. XIII in perioperative coagulation management. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2010;24(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan MTS, Rydz N, Goodyear D, Sholzberg M. Acquired factor XIII deficiency: a review. Transfus Apher Sci. 2018;57(6):724–730. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uea B. Reduction in wound healing disturbances by pre- and postoperative quantitative F XIII supplementation. Zentralblatt der Chirurgie. 1980;105:642–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaoui K, Ziemer S, Lammert H, Lammert I. Faktor-XIII-Prophylaxe und deren Einfluss auf Wundheilungsstörungen nach Tumorresektionen im Kopf-Hals-Bereich. Klinische Aspekte des Faktor-XIII-Mangels Diagnostik, klinische Relevanz, klinische Forschung Karger, Basel. 1997:158–65.

- 20.Fujita I, Kiyama T, Mizutani T, Okuda T, Yoshiyuki T, Tokunaga A, et al. Factor XIII therapy of anastomotic leak, and circulating growth factors. J Nippon Med Sch. 2006;73(1):18–23. doi: 10.1272/jnms.73.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerlach R, Raabe A, Zimmermann M, Siegemund A, Seifert V. Factor XIII deficiency and postoperative hemorrhage after neurosurgical procedures. Surg Neurol. 2000;54(3):260–264. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(00)00308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gierhake FW, Papastavrou N, Zimmermann K, Bohn H, Schwick HG. Prophylaxis of post-operative disturbances of wound healing with factor XIII substitution (author's transl) Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1974;99(19):1004–1009. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1107880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muto T, Ishibiki K, Nakamura N, Matsuda M, Shirai Y, Ogawa N. Post-operative F XIII deficiency and wound healing disturbances. Die Gelben Hefte. 1997;37:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishima Y, Nagao F, Ishibiki K, Matsuda M, Nakamura N. Factor XIII in the treatment of postoperative refractory wound-healing disorders. Results of a controlled study. Chirurg. 1984;55(12):803–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schramm W. FXIII and wound healing, prospective investigations and double-blind study. In: Proceedings from ‘coagulation factor XIII, symposium' (1982). p. 117–28.

- 26.Takeda Y, Mise Y, Ishizuka N, Harada S, Hayama B, Inoue Y, et al. Effect of early administration of coagulation factor XIII on fistula after pancreatic surgery: the FIPS randomized controlled trial. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2018;403(8):933–940. doi: 10.1007/s00423-018-1736-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herouy Y, Hellstern MO, Vanscheidt W, Schöpf E, Norgauer J. Factor XIII-mediated inhibition of fibrinolysis and venous leg ulcers. Lancet. 2000;355(9219):1970–1971. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wozniak G, Lutz H, Noll T, Alemany J. Treatment of chronic wounds with distinct secretion, by means of F XIII. III. Clinical modalities and results. Z Wundheilung 2001;6(20):11–14 (in German).

- 29.Peschen M, Thimm C, Weyl A, Weiss JM, Kurz H, Augustin M, et al. Possible role of coagulation factor XIII in the pathogenesis of venous leg ulcers. Vasa. 1998;27(2):89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erlebach R, Hartung H. Einsatz von Faktor XIII bei Schwerstbrandverletzten. Klinische Aspekte des Faktor-XIII-Mangels, Diagnostik, klinische Relevanz, klinische Forschung Karger: Basel. 1999:89–92.

- 31.Godje O, Gallmeier U, Schelian M, Grunewald M, Mair H. Coagulation factor XIII reduces postoperative bleeding after coronary surgery with extracorporeal circulation. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;54(1):26–33. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-872853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karkouti K, von Heymann C, Jespersen CM, Korte W, Levy JH, Ranucci M, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant factor XIII on reducing blood transfusions in cardiac surgery: a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146(4):927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korte WC, Szadkowski C, Gahler A, Gabi K, Kownacki E, Eder M, et al. Factor XIII substitution in surgical cancer patients at high risk for intraoperative bleeding. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(2):239–245. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318194b21e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy JH, Gill R, Nussmeier NA, Olsen PS, Andersen HF, Booth FV, et al. Repletion of factor XIII following cardiopulmonary bypass using a recombinant A-subunit homodimer. A preliminary report. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102(4):765–771. doi: 10.1160/TH08-12-0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerlach R, Tölle F, Raabe A, Zimmermann M, Siegemund A, Seifert V. Increased risk for postoperative hemorrhage after intracranial surgery in patients with decreased factor XIII activity: implications of a prospective study. Stroke. 2002;33(6):1618–1623. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000017219.83330.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theusinger OM, Baulig W, Seifert B, Muller SM, Mariotti S, Spahn DR. Changes in coagulation in standard laboratory tests and ROTEM in trauma patients between on-scene and arrival in the emergency department. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(3):627–635. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johansson PI, Sørensen AM, Perner A, Welling KL, Wanscher M, Larsen CF, et al. Disseminated intravascular coagulation or acute coagulopathy of trauma shock early after trauma? An observational study. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R272. doi: 10.1186/cc10553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaets SB, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Feketova E, Berezina TL, Malinina IV, et al. Recombinant factor XIII mitigates hemorrhagic shock-induced organ dysfunction. J Surg Res. 2011;166(2):e135–e142. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaets SB, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Feketova E, Berezina TL, Malinina IV, et al. Does recombinant factor XIII eliminate early manifestations of multiple-organ injury after experimental burn similarly to gut ischemia-reperfusion injury or trauma-hemorrhagic shock? J Burn Care Res. 2014;35(4):328–336. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182a228ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagashima F, Inoue S, Koami H, Miike T, Sakamoto Y, Kai K. High-dose Factor XIII administration induces effective hemostasis for trauma-associated coagulopathy (TAC) both in vitro and in rat hemorrhagic shock in vivo models. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;85(3):588–597. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan KYT, Yong ASM, Wang X, Ringgold KM, St John AE, Baylis JR, et al. The adhesion of clots in wounds contributes to hemostasis and can be enhanced by coagulation factor XIII. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):20116. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76782-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Theusinger OM, Baulig W, Asmis LM, Seifert B, Spahn DR. In vitro factor XIII supplementation increases clot firmness in rotation thromboelastometry (ROTEM) Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(2):385–391. doi: 10.1160/TH09-12-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caudill JS, Nichols WL, Plumhoff EA, Schulte SL, Winters JL, Gastineau DA, et al. Comparison of coagulation factor XIII content and concentration in cryoprecipitate and fresh-frozen plasma. Transfusion. 2009;49(4):765–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.02021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stein P, Kaserer A, Sprengel K, Wanner GA, Seifert B, Theusinger OM, et al. Change of transfusion and treatment paradigm in major trauma patients. Anaesthesia. 2017;72(11):1317–1326. doi: 10.1111/anae.13920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Innerhofer P, Fries D, Mittermayr M, Innerhofer N, von Langen D, Hell T, et al. Reversal of trauma-induced coagulopathy using first-line coagulation factor concentrates or fresh frozen plasma (RETIC): a single-centre, parallel-group, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(6):e258–e271. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaserer A, Casutt M, Sprengel K, Seifert B, Spahn DR, Stein P. Comparison of two different coagulation algorithms on the use of allogenic blood products and coagulation factors in severely injured trauma patients: a retrospective, multicentre, observational study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2018;26(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13049-017-0463-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tahlan A, Ahluwalia J. Factor XIII: congenital deficiency factor XIII, acquired deficiency, factor XIII A-subunit, and factor XIII B-subunit. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(2):278–281. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0639-RS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watanabe N, Yokoyama Y, Ebata T, Sugawara G, Igami T, Mizuno T, et al. Clinical influence of preoperative factor XIII activity in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2017;19(11):972–977. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wettstein P, Haeberli A, Stutz M, Rohner M, Corbetta C, Gabi K, et al. Decreased factor XIII availability for thrombin and early loss of clot firmness in patients with unexplained intraoperative bleeding. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(5):1564–1569. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000134800.46276.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ternstrom L, Radulovic V, Karlsson M, Baghaei F, Hyllner M, Bylock A, et al. Plasma activity of individual coagulation factors, hemodilution and blood loss after cardiac surgery: a prospective observational study. Thromb Res. 2010;126(2):e128–e133. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Listyo S, Forrest E, Graf L, Korte W. The need for red cell support during non-cardiac surgery is associated to pre-transfusion levels of FXIII and the platelet count. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2456. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chuliber FA, Schutz NP, Viñuales ES, Penchasky DL, Otero V, Villagra Iturre MJ, et al. Nonimmune-acquired factor XIII deficiency: a cause of high volume and delayed postoperative hemorrhage. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2020;31(8):511–516. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adam EH, Meier J, Klee B, Zacharowski K, Meybohm P, Weber CF, et al. Factor XIII activity in patients requiring surgical re-exploration for bleeding after elective cardiac surgery—a prospective case control study. J Crit Care. 2020;56:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Inoue H, Nishiyama N, Mizuguchi S, Nagano K, Izumi N, Komatsu H, et al. Clinical value of exogenous factor XIII for prolonged air leak following pulmonary lobectomy: a case control study. BMC Surg. 2014;14:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-14-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saito H, Fukushima R, Kobori O, Kawano N, Muto T, Morioka Y. Marked and prolonged depression of factor XIII after esophageal resection. Surg Today. 1992;22(3):201–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00308823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hildenbrand T, Idzko M, Panther E, Norgauer J, Herouy Y. Treatment of nonhealing leg ulcers with fibrin-stabilizing factor XIII: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(11):1098–1099. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wozniak G, Dapper F, Alemany J. Factor XIII in ulcerative leg disease: background and preliminary clinical results. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1996;22(5):445–450. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vanscheidt W, Hasler K, Wokalek H, Niedner R, Schöpf E. Factor XIII-deficiency in the blood of venous leg ulcer patients. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 1991;71(1):55–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burkhardt H, Zellner PR, Möller I. Factor XIII deficiency in burns. Chirurg. 1977;48(8):520–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Becker SWJ, Weidt F, Röhl K. The role of plasma transglutaminase (F XIII) in wound healing of complicated pressure sores after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:114–117. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saigusa S, Yamamura T, Tanaka K, Ohi M, Kawamoto A, Kobayashi M, et al. Efficacy of administration of coagulation factor XIII with definitive surgery for multiple intractable enterocutaneous fistulae in a patient with decreased factor XIII activity. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.09.2010.3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knab J, Dissemond J. Successful therapy of gram-negative foot infection by extension of systemic therapy by F XIII. ZfW 04/05;165–8 (in German).

- 63.Carneiro J, Alves J, Conde P, Xambre F, Almeida E, Marques C, et al. Factor XIII-guided treatment algorithm reduces blood transfusion in burn surgery. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2018;68(3):238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kohler HP, Ichinose A, Seitz R, Ariens RA, Muszbek L. Diagnosis and classification of factor XIII deficiencies. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(7):1404–1406. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Michael A, Durda ASW, Kerlin BA. State of the art in factor XIII laboratory assessment. Transfus Apher Sci. 2018;57:700–704. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dorgalaleh A, Tabibian S, Hosseini MS, Farshi Y, Roshanzamir F, Naderi M, et al. Diagnosis of factor XIII deficiency. Hematology. 2016;21(7):430–439. doi: 10.1080/10245332.2015.1101975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dorgalaleh A, Tabibian S, Hosseini S, Shamsizadeh M. Guidelines for laboratory diagnosis of factor XIII deficiency. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2016;27(4):361–364. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grossmann E, Akyol D, Eder L, Hofmann B, Haneya A, Graf BM, et al. Thromboelastometric detection of clotting factor XIII deficiency in cardiac surgery patients. Transfus Med. 2013;23(6):407–415. doi: 10.1111/tme.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weber CF, Sanders JO, Friedrich K, Gerlach R, Platz J, Miesbach W, et al. Role of thrombelastometry for the monitoring of factor XIII. A prospective observational study in neurosurgical patients. Hamostaseologie. 2011;31(2):111–117. doi: 10.5482/ha-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Raspe C, Besch M, Charitos EI, Flother L, Bucher M, Ruckert F, et al. Rotational thromboelastometry for assessing bleeding complications and factor XIII deficiency in cardiac surgery patients. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2018;24(9_suppl):136S–S144. doi: 10.1177/1076029618797472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferraris VA, Brown JR, Despotis GJ, Hammon JW, Reece TB, Saha SP, et al. 2011 update to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists blood conservation clinical practice guidelines. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91(3):944–982. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kozek-Langenecker SA, Ahmed AB, Afshari A, Albaladejo P, Aldecoa C, Barauskas G, et al. Management of severe perioperative bleeding: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology: first update 2016. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2017;34(6):332–395. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Godier A, Greinacher A, Faraoni D, Levy JH, Samama CM. Use of factor concentrates for the management of perioperative bleeding: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(1):170–174. doi: 10.1111/jth.13893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lier H, von Heymann C, Korte W, Schlembach D. Peripartum haemorrhage: haemostatic aspects of the new German PPH guideline. Transfus Med Hemother. 2018;45(2):127–135. doi: 10.1159/000478106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Spahn DR, Bouillon B, Cerny V, Duranteau J, Filipescu D, Hunt BJ, et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: fifth edition. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):984. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2347-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.CSL Behring. Corifact prescribing information. 2019.

- 77.Solomon C, Korte W, Fries D, Pendrak I, Joch C, Gröner A, et al. Safety of factor XIII concentrate: analysis of more than 20 years of pharmacovigilance data. Transfus Med Hemother. 2016;43(5):365–373. doi: 10.1159/000446813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alshehri FSM, Whyte CS, Mutch NJ. Factor XIII-A: an indispensable "factor" in haemostasis and wound healing. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):3055. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kalbhenn J, Wittau N, Schmutz A, Zieger B, Schmidt R. Identification of acquired coagulation disorders and effects of target-controlled coagulation factor substitution on the incidence and severity of spontaneous intracranial bleeding during veno-venous ECMO therapy. Perfusion. 2015;30(8):675–682. doi: 10.1177/0267659115579714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Granja T, Hohenstein K, Schussel P, Fischer C, Prufer T, Schibilsky D, et al. Multi-modal characterization of the coagulopathy associated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(5):e400–e408. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moerer O, Huber-Petersen JF, Schaeper J, Binder C, Wand S. Factor XIII activity might already be impaired before veno-venous ECMO in ARDS patients: a prospective, observational single-center cohort study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(6):1203. doi: 10.3390/jcm10061203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kalbhenn J, Glonnegger H, Wilke M, Bansbach J, Zieger B. Hypercoagulopathy, acquired coagulation disorders and anticoagulation before, during and after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in COVID-19: a case series. Perfusion. 2021;36(6):592–602. doi: 10.1177/02676591211001791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.von Meijenfeldt FA, Havervall S, Adelmeijer J, Lundstrom A, Magnusson M, Mackman N, et al. COVID-19 is associated with an acquired factor XIII deficiency. Thromb Haemost. 2021;121(12):1668–1669. doi: 10.1055/a-1450-8414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lichter Y, Badelbayov T, Shalev I, Schvartz R, Szekely Y, Benisty D, et al. Low FXIII activity levels in intensive care unit hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Thromb J. 2021;19(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s12959-021-00333-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Benfer J, Struck H. Factor XIII and fracture healing. An experimental study. Eur Surg Res. 1977;9(3):217–223. doi: 10.1159/000127940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Claes L, Burri C, Gerngross H, Mutschler W. Bone healing stimulated by plasma factor XIII. Osteotomy experiments in sheep. Acta Orthop Scand. 1985;56(1):57–62. doi: 10.3109/17453678508992981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Seitz R, Leugner F, Katschinski M, Immel A, Kraus M, Egbring R, et al. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: factor XIII, inflammation and haemostasis. Digestion. 1994;55(6):361–367. doi: 10.1159/000201166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Van Bodegraven AA, Tuynman HA, Schoorl M, Kruishoop AM, Bartels PC. Fibrinolytic split products, fibrinolysis, and factor XIII activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30(6):580–585. doi: 10.3109/00365529509089793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chiarantini E, Valanzano R, Liotta AA, Cellai AP, Fedi S, Ilari I, et al. Hemostatic abnormalities in inflammatory bowel disease. Thromb Res. 1996;82(2):137–146. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(96)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hayat M, Ariëns RA, Moayyedi P, Grant PJ, O'Mahony S. Coagulation factor XIII and markers of thrombin generation and fibrinolysis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14(3):249–256. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vrij AA, Rijken J, van Wersch JW, Stockbrügger RW. Differential behavior of coagulation factor XIII in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and in patients with giant cell arteritis. Haemostasis. 1999;29(6):326–335. doi: 10.1159/000022520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lorenz R, Olbert P, Born P. Factor XIII in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1996;22(5):451–455. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lorenz R, Heinmüller M, Classen M, Tornieporth N, Gain T. Substitution of factor XIII: a therapeutic approach to ulcerative colitis. Haemostasis. 1991;21(1):5–9. doi: 10.1159/000216195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Suzuki R, Toda H, Takamura Y. Dynamics of blood coagulation factor XIII in ulcerative colitis and preliminary study of the factor XIII concentrate. Blut. 1989;59(2):162–164. doi: 10.1007/BF00320061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lorenz R, Born P, Olbert P, Classen M. Factor XIII substitution in ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1995;345(8947):449–450. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bregenzer N, Caesar I, Andus T, Hämling J, Malchow H, Schreiber S, et al. Lack of clinical efficacy of additional factor XIII treatment in patients with steroid refractory colitis. The Factor XIII Study Group. Z Gastroenterol. 1999;37(10):999–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kruis W, Malchow H, Behnke M, Emmrich J, Hämling J, Lorenz R. Additive factor XIII treatment for severe ulcerative colitis. A double blind placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:A1014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Literature search summary.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.