Abstract

When a ribosome encounters the stop codon of an mRNA, it terminates translation, releases the newly made protein, and is recycled to initiate translation on a new mRNA. Termination is a highly dynamic process in which release factors (RF1 and RF2 in bacteria; eRF1 • eRF3 •·GTP in eukaryotes) coordinate peptide release with large-scale molecular rearrangements of the ribosome. Ribosomes stalled on aberrant mRNAs are rescued and recycled by diverse bacterial, mitochondrial, or cytoplasmic quality control mechanisms. These are catalyzed by rescue factors with peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase activity (bacterial ArfA • RF2 and ArfB, mitochondrial ICT1 and mtRF-R, and cytoplasmic Vms1), that are distinct from each other and from release factors. Nevertheless, recent structural studies demonstrate a remarkable similarity between translation termination and ribosome rescue mechanisms. This review describes how these pathways rely on inherent ribosome dynamics, emphasizing the active role of the ribosome in all translation steps.

Keywords: translation, termination, ribosome, rescue

INTRODUCTION

Translation of mRNA into a protein begins at a start codon — usually the AUG codon — and terminates at one of the three stop codons: UAA, UAG or UGA [1, 2], Efficient and accurate termination is required for the well-timed production of proteins, ribosome recycling, and translation initiation [3, 4], Unlike sense codons, which are recognized by aminoacyl-tRNAs, the stop codons are recognized by release factors: RF1 or RF2 in bacteria and aRF1/eRF1 in archaea/eukaryotes [5–9]. In addition, GTPase release factors — non-essential RF3 in some bacteria and essential aRF3/eRF3 in archaea/eukaryotes — take part in termination, their functions differ among these domains of life. Understanding the detailed structural mechanisms of translation termination is important because of the fundamental role of termination in protein synthesis, illustrated by the catastrophic consequences of mutations or other perturbations of mRNA that lead to aberrant protein release. For example, a major fraction of genetic disorders is caused by premature stop codons resulting in production of truncated proteins and degradation of mRNA [10].

In addition to release factors, diverse RF-like proteins have been recently identified in bacterial and eukaryotic mitochondrial and cytoplasmic translation systems that alleviate translational stress. These include ribosome-rescue and quality-control mechanisms, which enable recycling of ribosomes that stall on aberrant mRNAs. The latter include truncated mRNA and mRNA with non-optimal (rare) codons or structural features (e.g., mRNA secondary structure or protein-binding sites) that prevent ribosome elongation. Recognition, peptide release, and recycling of stalled ribosomes is accomplished by independent pathways, including ArfA and ArfB in bacteria, mtRF 1a and mtRF-R in mitochondria, and Dom34 and Vms1 in eukaryotic cytoplasm. Recent biophysical and structural studies demonstrated the critical role of ribosome dynamics in translation, termination, and ribosome rescue. The mechanics of ribosome rearrangements echo the models that Alexander Spirin proposed for ribosomal translocation along mRNA, including the large-scale rearrangements of ribosomal subunits [11, 12], These findings emphasize that the ribosome plays a major mechanistic role in all translation steps including termination and ribosome rescue.

TRANSLATION TERMINATION IN BACTERIA AND MITOCHONDRIA

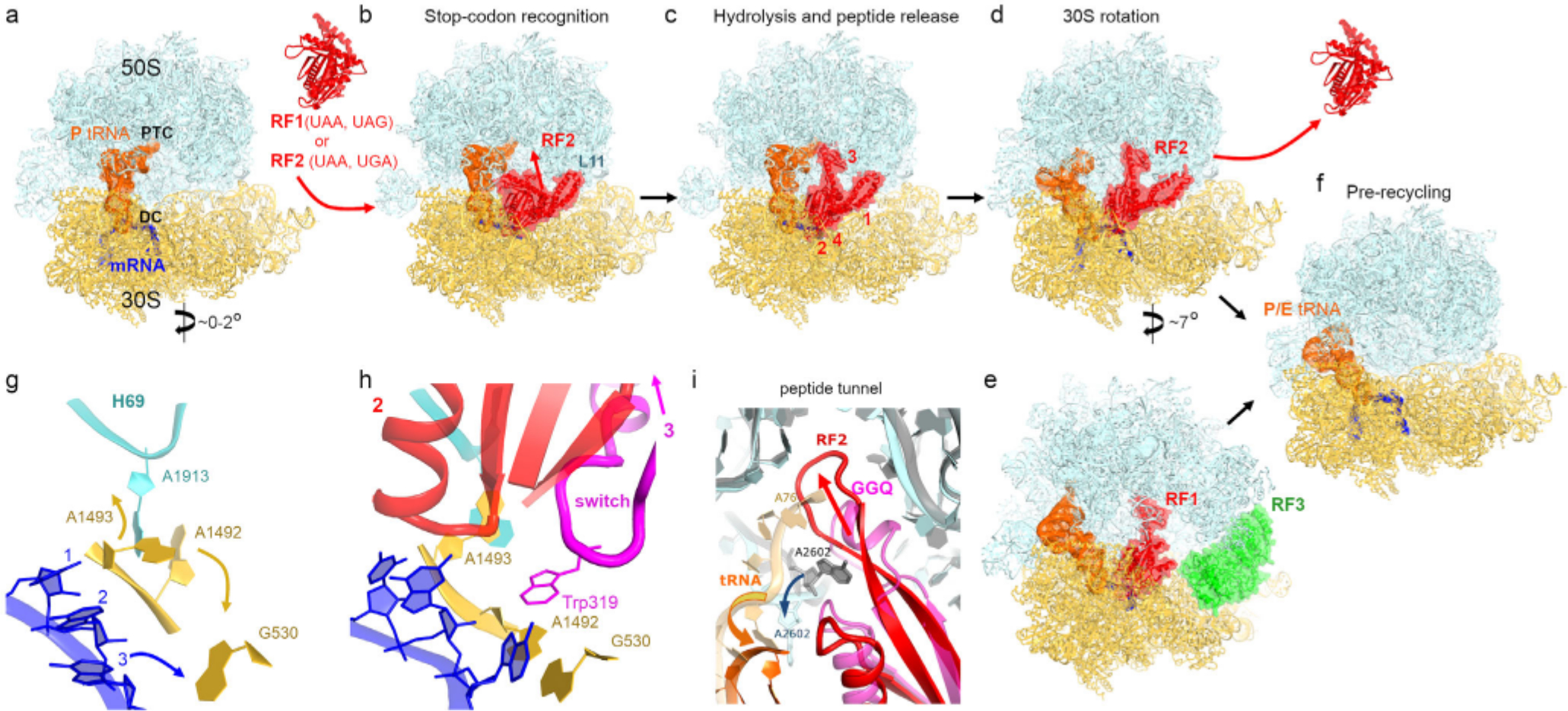

Release factors are bifunctional proteins: they recognize stop codons and catalyze the hydrolysis of the ester bond in peptidyl-tRNA. Bacterial release factors RF1/RF2 independently recognize the UAA, UAG/UAA, and UGA codons, respectively. These ~350–380 aa-long proteins comprise the codon-recognition superdomain (domains 2 and 4), which binds the small 30S ribosomal subunit, and the catalytic domain 3, which binds the large 50S ribosomal subunit (Fig. 1, a–c). The dynamic domain 1 interacts with the peripheral L11 stalk of the 50S subunit (Fig. 1, b and c) contributing to the binding of release factors to the ribosome [13, 14]. The codon-recognition superdomain carries the conserved p184XT186 (where X is often an A, V or another short amino acid) motif in RF1 or S206PF208 motif in RF2 [15, 16], which interact with stop codons (E. coli residue numbers are shown for bacterial proteins and RNA unless noted otherwise) [17–20]. Other residues of domain 2 have also been identified in mutational and biochemical studies to be critical for stop-codon specificity of release factors [21, 22].

Fig. 1.

Bacterial translation termination involves large-scale conformational changes, a-d) Cryo-EM structures demonstrating rearrangements of a release factor and intersubunit rotation of a bacterial 70S ribosome upon stop-codon recognition and peptide release. E. coli RF2 is shown: panels (b and c) [51 ]and d [61], The decoding center (DC) and peptidyl transferase center (PTC) are labeled in panel (a). Crystal structure of free RF2 is shown between panels (a) and (b) [40], Domain organization for RF1/RF2 is shown with Arabic numerals in panel (c). e) Cryo-EM structure of RF1 and RF3 on E. coli ribosome with P/E tRNA and rotated 30S subunit [58], f) Cryo-EM structure of the pre-recycling E. coli ribosome with P/E tRNA and rotated 30S subunit after dissociation of release factors [61], g and h) Rearrangement of the codon and decoding center (DC) upon binding of RF2 (Structure II in [61]). Stop codon and DC in panel g were modeled based on Structure I in ref. [54], i) Rearrangement of RF2 in the peptidyl transferase center (PTC; [61]). The catalytic conformation of RF2 with the GGQ-bearing α-helix is shown in pink and the ribosome is shown in gray. The β-hairpin conformation of RF2 (red) coincides with movement of A2602 and departure of tRNA (orange) from the PTC (cyan).

Catalytic domain 3 contains a long α-helix crowned with the universally conserved GGQ motif (Figs. 1c and 2c), shown to play a key catalytic role in early studies [23, 24], Mutations of either glycine in the bacterial and eukaryotic release factors render the release factors inactive [24–26], By contrast, the release factors with glutamine mutations retain catalytic activity [25, 27, 28], with the exception of the GGP mutant, which is inactive [18, 29]. These studies suggest that the unique conformation of the GGQ backbone is critical for the catalytic activity of release factors.

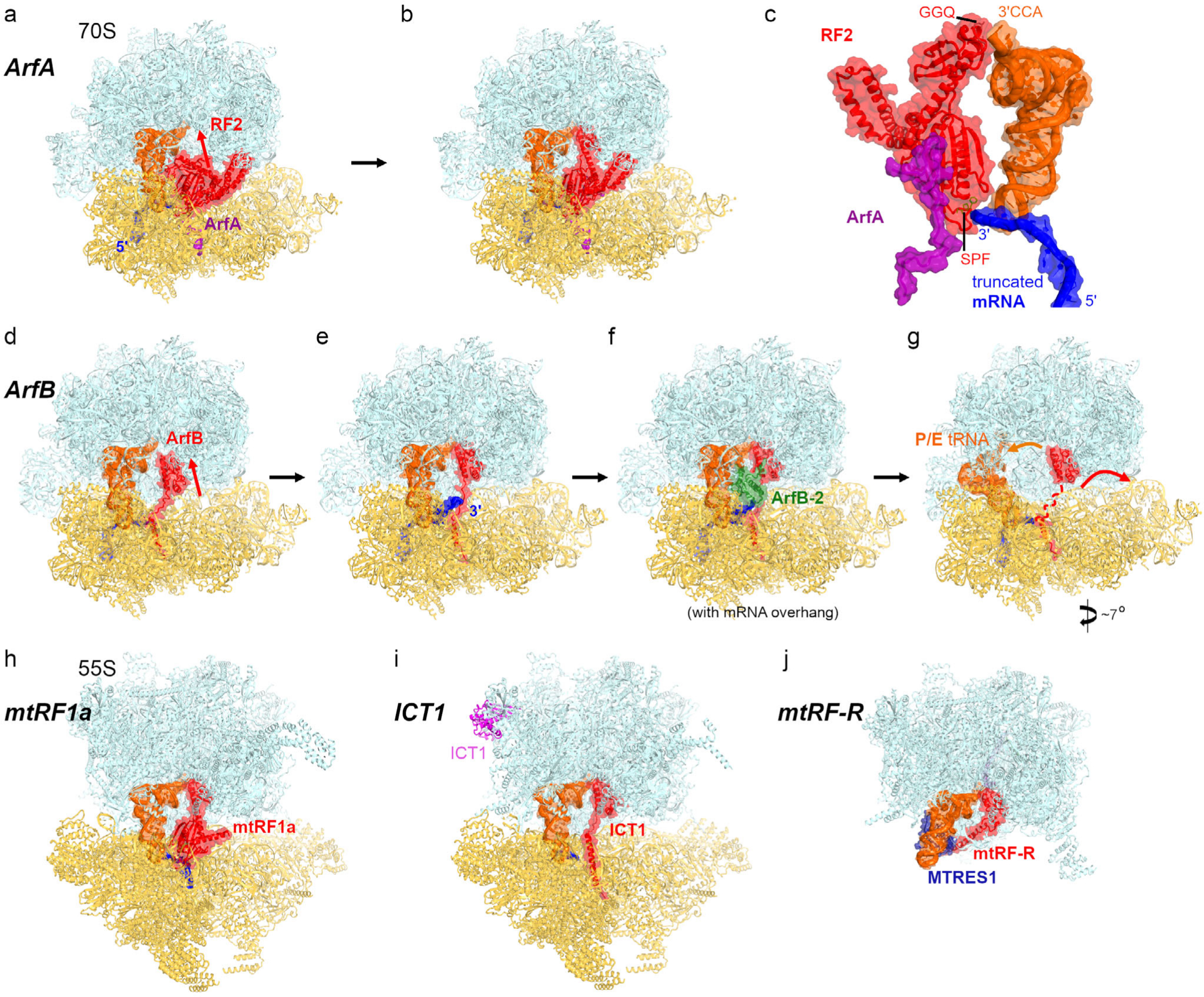

Fig. 2.

Ribosome rescue and release mechanisms involving bacterial factors ArfA and ArfB, and mitochondrial factors mtRF1a, ICT1 and mtRF-R. a and b) Cryo-EM structures of E. coli ribosomes with truncated mRNA, ArfA and compact (a) or extended (b) RF2 [49]. c) A close-up view of interactions between ArfA, RF2, mRNA and P-site tRNA. d-g) Cryo-EM structures of E. coli ribosomes with truncated mRNA (with a 0- or 9-nt-long overhang after the P site codon) and ArfB [110, 111], h) Cryo-EM structure of porcine mitochondrial 55S termination complex with mtRF1a bound to the stop codon [87] closely resembles bacterial termination complexes with RF1. i) Cryo-EM structure of mitochondrial 55S rescue complex with ICT1 [87] closely resembles bacterial 70S complex with ArfB [compare to panel (e)]. j) Cryo-EM structure of large mitochondrial subunit bound with human rescue factor mtRF-R and auxiliary factor MTRES1 [98].

High-resolution crystallographic studies provided detailed visualization of stop-codon recognition and the catalytic mechanism of release factors on all three stop codons [17–20] (see reviews [30–34]). Recent advances in cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) enable determination of previously unattainable transient states of macromolecules at near-atomic resolution. Taken together with biochemical and biophysical observations [35–38], recent structural studies allow a nearly complete reconstruction of the dynamic mechanism of termination — from initial recognition of the stop codon to hydrolysis of peptidyl-tRNA and to dissociation of the release factor.

Dynamics of the release factors are essential for accurate translation termination.

In a cell, release factors can stochastically sample the ribosomal A site carrying the sense or stop codons. To perform accurate termination, the hydrolase function should be strictly coordinated with stop codon recognition. This coordination is achieved by preventing the insertion of the catalytic domain 3 into the peptidyl transferase center (PTC) unless the codon-recognition superdomain is accommodated in the A site containing a stop codon. Crystal structures and solution studies have shown that free release factors adopt a compact conformation [39–42], in which the catalytic domain is packed on the codon recognition domain (Fig. 1, a and b). In the ribosome, however, the release factors were captured by early structural studies in an extended conformation (Fig. 1c), in which RF1 or RF2 in the ribosomal A site bridges the 30S and 50S subunits [17–20, 43, 44], These findings suggested an appealing hypothesis that release factors sample the ribosomal A site in a compact conformation, in which the GGQ motif is positioned far from the peptidyl transferase center. The “opening” of the release factor was proposed to occur upon recognition of the stop codon [17, 43, 45–47], Structural evidence for such transition has been obtained only recently. Crystallographic work with a hyper-accurate RF1 mutant and antibiotic blasticidin S (BlaS) captured the codon-recognition superdomain in the A site, while the catalytic domain was disordered in the intersubunit space, in keeping with the dynamic rearrangements of release factors on the ribosome [48], Subsequent cryo-EM studies visualized compact RF2 on the ribosome bound with an alternative release factor A (ArfA; [49]) and ArfA mutant [50], highlighting affinity of the compact release factor to the ribosome (Fig. 2a). ArfA assists RF2 in recognizing ribosomes without stop codons (discussed below), so the structural dynamics of RFs on a terminating ribosome remained unseen until a recent time-resolved cryo-EM study [51], Both RF1 and RF2 were captured in compact inactive conformations at early time points of the termination reaction (Fig. 1b). They rearranged into the catalytically active extended conformations at the later time points (Fig. 1c; [51]). The opening of release factors is coupled with local rearrangements of the ribosomal decoding center (i.e., 30S A site) and peptidyl transferase center on the 50S subunit, which together account for high accuracy of translation termination.

Local rearrangements in the decoding center and peptidyl transferase center.

The decoding center relies on universally conserved residues of small ribosomal RNA — G530, A1493 and A1493 of E. coli 16S — to accurately decode mRNA. During elongation, these nucleotides stabilize Watson—Crick base-pairing between mRNA codon and tRNA anticodon, and account for elongation fidelity [52–54], These nucleotides are also essential during termination, as they facilitate the opening of the release factor to catalyze peptide release (Fig. 1, g and h; [17]). Specifically, the “terminating” conformation of the decoding center can accommodate the flexible linker between the codon-recognition and catalytic domains of RFs (Fig. 1h), which is termed the switch loop (aa ~290–305 in RF1 and ~310–325 in RF2) and is flexible in the compact release factor [51], Recognition of a stop codon by a release factor results in stacking of the third nucleotide of the stop codon on G530, and rearranges A1492 and A1493 into a termination-specific conformation (Fig. 1, g and h). Packing of the switch loop (with Trp319 in RF2) against A1492 and A1493 directs domain 3 into the PTC, resulting in the activated extended release factor (Fig. 1h). Consistent with the key role of the switch loop, its mutations disrupt the dynamics of RF opening and change the accuracy of termination [19, 48].

In the peptidyl transferase center, the GGQ motif is positioned to catalyze the hydrolysis of the ester bond linking the nascent peptide with P-site tRNA [17], High-resolution crystal structures showed that A2602, critical for termination efficiency [55–57], assists in docking the GGQ motif into the PTC by stacking on the conserved Arg256 (RF1). The GGQ motif forms a short α-helix (Fig. 1i), which presents the backbone amide of the glutamine near the ribose of the terminal P-tRNA nucleotide A76. The NH group is positioned to stabilize a transition-state intermediate and the leaving group [17], in keeping with the essential catalytic role of the glutamine backbone [29].

After peptidyl-tRNA hydrolysis, both the peptide and the release factor must dissociate from the ribosome to allow ribosome disassembly into subunits and initiation of a new round of translation. Two cryo-EM studies have reported several structures that suggest conformational rearrangements resulting in dissociation of RF 1 and RF2. An ensemble of post-release RF1-bound ribosomes was visualized using Apil37 [58], which binds the peptide tunnel and stalls RF1 on the ribosome [59]. This complex was formed in the presence of GTPase RF3, which stimulates dissociation of RF1 [35, 60], In the other study, an ensemble of RF2-bound structures was resolved without RF3, consistent with the independence of RF2 dissociation on RF3 [35], The structures visualized retraction of the deacylated CCA 3’-end of tRNA from the PTC, coupled with rotation of A2602 from its GGQ-coordinating position (Fig. 1i). The GGQ-bearing motif of RF2 was rearranged into a long (3-hairpin that extends into the peptide tunnel, as if to plug the PTC (Fig. 1i). This suggests that the tip of the catalytic domain can rearrange to bias diffusion of the newly formed protein toward the exterior end of the tunnel, facilitating release of the protein from the ribosome.

Intersubunit rotation after peptide release is coupled with RF dissociation.

During translation, the ribosome undergoes a series of intersubunit rearrangements. In the elongation stage, tRNAs and mRNA translocate within the ribosome as the small subunit spontaneously rotates by ~10° and binds the GTPase translocase EF-G in bacteria or eEF2 in eukaryotes (reviewed in refs [33, 62–66]). By contrast, large-scale ribosome rearrangements were not thought to be part of the termination mechanism. Indeed, FRET studies and X-ray crystallography have shown that release factors bind and stabilize the non-rotated ribosome [35–37, 67] in both the pre-reaction-like [68] and post-reaction states [17–20], Recent biophysical observations, however, suggested that interaction of the release factors with the ribosome involves large-scale ribosome dynamics [35], Subsequent cryo-EM studies have visualized RF1 [58] and RF2 [61] bound to the ribosome in different rotational states, distinct from previously determined crystal structures. They have visualized how ribosome rearrangements facilitate dissociation of the release factors from the ribosome.

Following peptidyl-tRNA hydrolysis, the ribosome contains deacyl-tRNA in the P site and release factor in the A site (Fig. 1c). Due to reduced affinity of the deacyl-tRNA to the 50S P site (relative to that of peptidyl-tRNA), and increased affinity to the 50S E site, the tRNA can sample the hybrid P/E state, in which the acceptor arm is shifted on the large subunit. Solution FRET and cryo-EM studies have shown that the deacyl-tRNA can spontaneously fluctuate on the elongating ribosome between the classical P/P state and the hybrid P/E states, coinciding with the non-rotated and rotated ribosome conformations, respectively [37, 69–74], Similar fluctuations can occur in the presence of release factors [58, 61], Gradual rotation of the small subunit is coupled with the movement of the catalytic domain of release factor from the PTC, while the codon-recognition domain remains attached to the decoding center [61], Upon an ~7° rotation of the small subunit, an equilibrium of structures with and without RF2 is observed, suggesting that RF2 dissociates primarily from a rotated ribosome conformation (Fig. 1, d and f). Similarly, RF1 dissociates in the presence of GTPase RF3 (Fig. 1e), which stabilizes the rotated ribosome conformation [58, 75–78], It is noteworthy that RF3 is not conserved in bacteria [79] and is dispensable for the growth of Escherichia coli [80, 81], This indicates that RF1 can perform termination and dissociate without RF3, and that dissociation of both RF1 and RF2 is driven by ribosome rearrangements. Destabilization of the release factor on the small subunit is coupled with disassembly of the central intersubunit bridge formed by the 23S helix 69 (H69) and the decoding center (Fig. 1h). In the rotated ribosome without RF2, H69 is detached from the decoding center and docked at the 50S subunit near A2602, suggesting that the ribosome restructuring coincides with local PTC rearrangements after peptide release [61], In this position, H69 would clash with RF2, in keeping with the post-RF2-dissociation state. With H69 detached from the small subunit, the ribosome is a substrate for binding of the ribosome recycling factor RRF [82, 83], which splits the ribosome into subunits with the aid of EF-G.

Mitochondria encode two RF-like proteins, mtRF1a and mtRF 1, but only mtRF 1 a has been shown to catalyze translation termination (reviewed in ref. [84]). Very similar to bacterial RF1, human mtRF 1 a (HMRF1L) features a P206KT208 motif and catalyzes peptide release on the UAA and UAG stop codons ([85, 86] (human residue numbering is used for eukaryotic proteins unless noted otherwise). The recent cryo-EM work has visualized the porcine mitochondrial termination complex with mtRF1a (Fig. 2h; [87]). Interactions of the codon-recognition domain, switch loop, and domain 3 with the ribosome demonstrate that the structural mechanisms of codon recognition and termination by mtRF1a are similar to those of RF1. Although dissociation of mtRF1a remains to be visualized, conservation of intersubunit rearrangements in mitoribosomes [88, 89] suggests that mtRF1a dissociation in the absence of a mitochondrial RF3 ortholog may be similar to that of RF2.

By contrast, the function of mtRFl remains unclear [84], This bioinformatically identified ~445-aa homolog of RF1 [90] features a ~70-aa N-terminal extension of domain 1, which may affect ribosome binding. Furthermore, the codon-recognition superdomain is substantially diverged from that of RF1, and carries P264EVGLS269 and other extensions that appear incompatible with mRNA codons in the A site [91, 92], mtRF1 was hypothesized to recognize the arginine codons AGA and AGG, which were thought to be reassigned as termination codons in mitochondria [93], However, no binding or catalytic activity of mtRF1 could be detected on ribosomes programmed with mRNAs with stop or arginine codons, and the protein fails to compensate for the deletion of the functional release factor homolog in yeast [85–87], Subsequent work showed that termination at the arginine codons in human mitochondria occurs due to the absence of tRNAs that could decode these codons, leading to −1 frameshifting that positions the UAG codon in the A site for canonical termination by mtRF1a [94], Because mtRF1 carries the conserved catalytic domain with the GGQ motif, mtRF1 may participate in a quality-control mechanism that recognizes a specific conformation of the ribosomal A site [92] and/or requires additional factors that remain to be identified.

RESCUE OF STALLED RIBOSOMES BY TERMINATION-LIKE MECHANISMS IN BACTERIA AND MITOCHONDRIA

Ribosomes stall on mRNAs that are truncated, do not contain a stop codon, or that pause ribosomes by other mechanisms [95], Recent studies identified ribosome rescue systems that release peptides from stalled ribosomes. In bacteria, alternative rescue factors A (ArfA) and B (ArfB) represent independent molecular mechanisms that complement the trans-translation rescue system [95–97], Recent structural studies have visualized the structural mechanisms of these rescue factors. In mitochondria, two ribosome rescue systems involve RF-like proteins that have recently been visualized by cryo-EM: ICT1, which resembles bacterial ArfB and acts on mitoribosomes bearing truncated mRNA [87], and mtRF-R (encoded by c12orf65), which cooperates with MTRES1 (encoded by c6orf203) to recognize large mitochondrial subunits with stalled peptidyl-tRNA [98].

Bacterial alternative rescue factor A (ArfA).

ArfA (previously termed YhdL) is a small ~70-aa protein that recruits RF2 to release peptides from the ribosomes stalled on truncated mRNAs without a stop codon (Fig. 2, a–c; [99–101]). Five cryo-EM studies demonstrated that the positively charged C-terminal tail of ArfA binds the mRNA tunnel formed predominantly by the 16S ribosomal RNA, thus “sensing” the ribosomes whose tunnel is vacant due to mRNA truncation [49, 50, 102–104], The N-terminal part folds into a compact domain near the decoding center and interacts with the codon-recognition domain of RF2, although the conserved SPF motif of RF2 is not required for this interaction (Fig. 2c). In all these studies, ArfA was captured with RF2 in an extended, catalytically competent conformation resembling those of release factors on stop codons (Fig. 2b). In this conformation, the switch loop of RF2 is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions of Trp319 with ArfA. In addition, two studies captured compact RF2 (Fig. 2a), whose codon-recognition domain is ~5 Å farther from the A site [49, 50], Although interactions of RF2 with ArfA differ from those with a stop codon, the structures highlight a similar mechanism of release-factor activation by enabling RF2 opening upon recognition of the specific signal in the decoding center. The list of ArfA-like rescue factors continues to grow, revealing genus-specific peculiarities of the quality control mechanisms (reviewed in ref. [105]). For example, while BrfA in B. subtilis depends on RF2 and is similar to ArfA [106], ArfT in F. tularensis can recruit either RF1 or RF2 to release peptides from stalled ribosomes [107, 108].

Bacterial alternative rescue factor B (ArfB).

ArfB (previously termed YaeJ) is a ~140-aa release factor that contains both the mRNA-tunnel-binding C-terminal tail and an RF-like catalytic domain carrying the GGQ motif (Fig. 2, d–g). Biochemical studies suggested that ArfB could rescue not only the ribosomes with mRNA truncated immediately after the P-site codon, but also ribosomes with longer mRNA extensions [109], although the catalytic activity of ArfB decreases with the increasing length of mRNA and might depend on the sequence of mRNA overhang [110, 111], A crystallographic structure revealed that the positively charged tail of ArfB forms an α-helix in the vacant mRNA tunnel, while the catalytic N-terminal domain docks into the PTC similarly to that of canonical release factors [112], Binding of ArfB to the non-rotated ribosome resembles that of release factors, in keeping with recognition of the substrate with stalled peptidyl-tRNA. Since the mRNA tunnel cannot be occupied simultaneously by ArfB and a longer mRNA overhang, cryo-EM studies have recently visualized 70S ribosome structures with ArfB and mRNA extending 2 or 9 nucleotides beyond the P site [110, 111], The decoding center nucleotides A1492 and A1493 interact with ArfB and mRNA, allowing accommodation of different mRNA overhangs via different conformations [111]. These findings highlight the structural plasticity of the ribosomal decoding center and suggest that other rescue pathways, such as ArfA in bacteria and Dom34 in eukaryotes (discussed below) may detect ribosomes with a broader range of mRNA overhangs and/or sequences.

In complexes with mRNA extending beyond the P site codon, the α-helical tail of ArfB binds in the mRNA tunnel, whereas the +9 mRNA overhang is excluded from the tunnel and is either disordered in the intersubunit space [110] or stabilized by a second copy of ArfB (Fig. 2, e and f) [111]. These observations indicate that ArfB may sense stalled ribosomes via different pathways, depending on the mRNA sequence or structural dynamics allowing mRNA excursions outside the mRNA tunnel. Furthermore, cryo-EM data classification revealed an ensemble of structures with the catalytic N-terminal domain of ArfB inside and outside of the PTC (Fig. 2, d and e) [111]. These dynamics are consistent with biochemical observations and suggest that the substrate-recognition mechanism is reminiscent of that for canonical release factors, which first recognize the decoding center on the small subunit then rearrange to dock the catalytic domain next to the scissile peptidyl-tRNA bond.

The cryo-EM analyses have also identified ArfB on the ribosomes with different degrees of intersubunit rotation coupled with formation of the P/E hybrid state by deacylated tRNA (Fig. 2, f–g). The occupancy of dimeric ArfB decreases with the increasing rotation of the 30S subunit, and the highly rotated ribosomes exhibit an equilibrium between particles with monomeric ArfB-bound and vacant A-site (Fig. 2g) [111]. Helix 69 of the vacant ribosomes is dissociated from the decoding center and would likely interfere with ArfB binding to the large subunit. These findings suggest that ArfB, similarly to the canonical release factors, dissociates upon spontaneous intersubunit rotation and disruption of the H69-DC bridge. Although the components of the parallel rescue pathway — involving ArfA and RF2 — have only been visualized on a non-rotated ribosome, the conserved ribosomal dynamics of RF-bound and ArfB-bound complexes suggest that a similar mechanism may be employed to release ArfA and RF2 and prepare the ribosome for recycling.

Mitochondrial rescue factor ICT1 (~200 aa), a close homolog of bacterial ArfB, catalyzes peptide release from stalled ribosomes [113], ICT1 (“immature colon carcinoma transcript-1”, also termed MRPL58) is essential for cell growth [113–115], and its dysregulation is associated with tumorigenesis [116], Curiously, one molecule of ICT1 binds to the central protuberance of the mitochondrial ribosome [117], but this position is distant from the A site, indicating that this molecule does not catalyze ribosome rescue (Fig. 2i). The central protuberance of the large subunit interacts with the small subunit and with tRNAs, rendering the structure of the central protuberance critical for the proper ribosome assembly and function throughout kingdoms of life [118–122], Although the architectural function of ICT 1 may partially contribute to mitochondrial translation regulation, it is the catalytic function of a different — transiently bound — ICT 1 molecule that is essential for mitochondrial translation. The significance of the catalytic function was demonstrated by mutational studies showing abrogation of cell growth upon perturbation of the ICT1 GGQ motif [113].

In the recent cryo-EM structure of the ICT 1-bound rescue complex [87], the positively charged C-terminal helix of ICT 1 is found in the mRNA tunnel (Fig. 2i). The catalytic N-terminal domain docks at the PTC similarly to that of ArfB. Position of the GGQ motif supports the catalytic role of the glutamine backbone, similar to that in the release factors. The cryo-EM study was performed using an mRNA truncated at the P site. It remains to be visualized if/how ICT1 recognizes ribosomes with longer mRNA overhangs [123], and whether the propensity of isolated ICT1 to dimerize [124] reflects a mechanistic scenario similar to that of dimeric ArfB, which can stabilize long mRNA overhangs [111].

Mitochondrial release factor mtRF-R (~ 170 aa) is a mitochondrial peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase that is essential for cell viability [125], Mutations or dysregulation of this protein perturb mitochondrial translation and are associated with disease [126–128], A recent cryo-EM study visualized human mtRF-R with peptidyl-tRNA on the large mitochondrial ribosomal subunit [98], Binding of mtRF-R in the A site is aided by MTRES1 docked at the tRNA anticodon stem (Fig. 2j). As expected, the catalytic domain of mtRF-R docks into the PTC and presents the GGQ motif near the terminal nucleotide of the P-tRNA. Surprisingly, peptidyl-tRNA is intact, likely due to a unique conformation of the terminal lysine of the nascent peptide, which has been shown to be a signature of stalled ribosomes [129, 130], Although mtRF-R with MTRES 1 can hydrolyze peptidyl-tRNAs on model E. coli 50S complexes in vitro [98], it remains to be shown whether and how mtRF-R rescues mitochondrial subunits stalled with lysyl-tRNA. Dissociation of mtRF-R and MTRES 1 from the large subunit, required for ribosome recycling, is likely coupled with dissociation of deacyl-tRNA after peptidyl-tRNA hydrolysis. Yet it is possible that additional factors assist in disassembly of this rescue complex. Future studies will determine substrate specificity of mtRF-R and the mechanism of mtRF-R/MTRES1 dissociation.

CYTOPLASMIC TERMINATION AND RIBOSOME RESCUE IN EUKARYOTES

Translation termination by eRF1 •eRF3.

Eukaryotic eRF1 (~440 aa) is structurally diverged from bacterial release factors, and its catalytic function depends on the GTPase activity of eRF3 [23, 131–133], The codon-recognition domain of eRF 1 (N domain) is folded differently from that of bacterial release factors, and carries conserved stretches of amino acids, such as the T58ASNIKS64 motif, that is essential for recognition of all three stop codons [134–136], Furthermore, unlike bacterial release factors, eRF1 recognizes a tetranucleotide including the three nucleotides of a stop codon and a downstream nucleotide [137–139]. Ribosome-profiling and other studies have shown that the stop codons followed by a pyrimidine result in abundant readthrough of the annotated stop codons [140], in keeping with lower catalytic activity of eRF1 on tetranucleotides with a terminal pyrimidine [138], This dependence contributes to reassignment of stop codons to sense codons in ciliates, although the “fourth” nucleotide is not the exclusive determinant of the reassignment [141–143], Additional features of mRNA, such as sequence and structure around and downstream of the stop codon, play a role in the efficiency of eukaryotic termination [144–147].

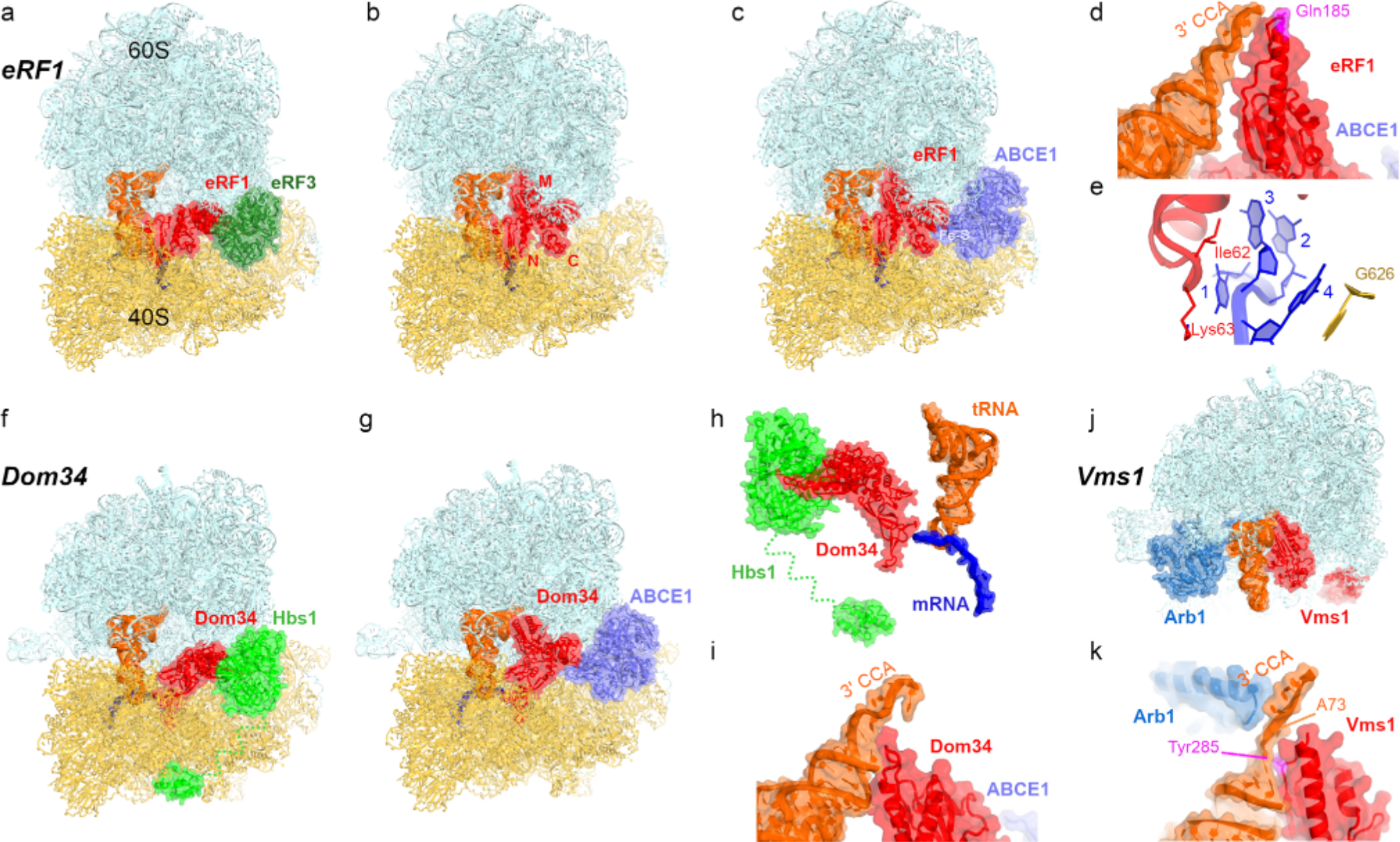

Despite differences between eukaryotic and bacterial release factors, eukaryotic termination resembles that of its bacterial counterpart in that the accuracy is controlled by a large-scale conformational change in eRF1. Cryo-EM studies captured eRF1 on the ribosome in three functional states (Fig. 3, a–c): with eRF3 (with compact eRF1 inactive for peptide release) [148–150], without eRF3 (with extended eRF1 activated for peptide release) [139, 151] and with ATP-binding cassette protein ABCE1 (Rli1 in yeast; [137, 148, 152]), a recycling factor that disassembles ribosomes into subunits [153–155], These structures, combined with biochemical and biophysical data, allow reconstruction of most steps of eukaryotic termination. Upon binding of eRF1 • eRF3 • GTP to the ribosome with a stop codon in the A site [156] (Fig. 3a), GTP hydrolysis releases eRF3 and leads to the insertion of the catalytic M domain of eRF1 with the GGQ motif into the PTC (Fig. 3, b and d). GTP hydrolysis is catalyzed by the sarcin-ricin loop of the large subunit, where eRF3 binds similarly to other translational GTPases, such as elongation factors EF-Tu and eEF1A. The codon-recognition residues of eRF1 interact with all four nucleotides of the mRNA termination signal, which adopts a U-turn conformation (Fig. 3e) resulting in mRNA compaction in the ribosomal tunnel [157], Interestingly, despite structural and sequence divergence from bacterial termination (Fig. 1c), eukaryotic and bacterial termination share similar aspects in stop-codon recognition, such as recognition of the purine at position 3 (R3) by the conserved Thr58 and Ile62 of the TASNIKS motif of eRF1 (Fig. 3e; [137] and Thr198 and lie 196 of E. coli RF1 [158], Furthermore, the last purine of the termination signal (R4 in eukaryotes or R3 in bacteria) stacks on the decoding center nucleotide G626 (G530 in E. coli) in keeping with the preference for purine over pyrimidine at this position (Figs, 1h and 3e).

Fig. 3.

Eukaryotic translation termination and cytoplasmic ribosome rescue mechanisms, a-c) Rearrangements of release factor eRF1 on the 80S ribosome with a stop codon upon GTP hydrolysis on eRF3 (a-b) and interaction with recycling factor ABCE1 (c; Rli1 in yeast), d) Interaction of the catalytic conformation of eRF1 with the P-site tRNA [137], e) Recognition of the 4-nucleotide stop signal by eRF1 involves residues of the TASNIKS motif (Ile62 and Fys63 are shown) and G626 of 18S rRNA [137], f and g) Rearrangements of Pelota (Dom34 in yeast) on the 80S ribosome with truncated mRNA upon GTP hydrolysis on Hbs1 [163] and binding of ABCE1 [164], h) Recognition of truncated mRNA by Dom34 [163], i) Interaction of the extended conformation of Dom34 with the P-site tRNA [164], j) 60S rescue complex with peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase Vms1 and Arb1 [165], k) Interaction of Vms1 and Arb1 with the tRNA.

In the extended catalytic conformation, the C domain of eRF1, which bridges the N and M domains, can interact with the Fe-S domain of ABCE1 to initiate ribosome recycling (Fig. 3c; [148, 152]). ABCE1, whose conformational dynamics are controlled by two ATP-binding sites [159] and which has affinity to both the 80S ribosome and the 40S subunit [160–162], assists in splitting the post-termination ribosome via intermediate eRF 1 -dissociation states that remain to be visualized.

Rescue of stalled ribosomes by Dom34•Hbs1 and Vms1.

Although no eukaryotic analogs of ArfA or ArfB have been reported, several quality-control mechanisms have been discovered that resemble the eukaryotic termination system [166], Dom34 (Pelota in mammals) and GTPase Hbs1 form a heterodimer, which rescues ribosomes stalled on truncated mRNAs, structured mRNAs, or the mRNA 3’-UTRs [167–170], Dom34 and Hbs1 are remarkably similar to eRF1 and eRF3, respectively (Fig. 3, f and g). Dom34, however, lacks the catalytic GGQ motif, and therefore does not hydrolyze peptidyl-tRNA, but instead promotes subunit dissociation [170]. Cryo-EM structures showed that the binding of Dom34 and Hbs 1 to the ribosome is similar to that of eRF 1 and eRF3 [148, 163, 171], The GTPase domain of Hbs1 docks at the sarcin ricin loop, whereas the long N-terminal tail of Hbs1 reaches toward the mRNA entry tunnel (Fig. 3, f and h), implicating a role in recognition of stalled mRNA substrates [163, 171], Dom34 (β-hairpin reaches into the decoding center, distantly resembling bacterial rescue factors that sample the vacant mRNA tunnel (Fig. 3h). Comparison of tRNA-, eRF1-, and Dom34-bound ribosome structures revealed different conformations of the decoding center [148], highlighting the plasticity of the eukaryotic decoding center echoing that of bacterial ribosomes [111]. Moreover, Dom34 can be accommodated in the presence of longer mRNAs, including the poly-A tail, due to redirection of the mRNA overhang into intersubunit space [148], This is reminiscent of bacterial rescue complexes with ArfB [110, 111] and rationalizes how Dom34 can recognize a range of substrates not limited to mRNAs truncated after the P-site codon. Upon opening of Dom34 (Fig. 3g), the M domain binds the stem of the acceptor arm of tRNA to assist in displacement of tRNA from the ribosome (Fig. 3i). Similarly to canonical termination, disassembly of Dom34-bound ribosomes involves ABCE1 [172], which interacts with Dom34 after Hbs1 departure (Fig. 3g; [148, 164]). Future studies will provide insights into the detailed mechanics of ribosome disassembly following canonical termination and Dom34 binding, which likely include similar inter- and intra-subunit rearrangements.

The peptidyl-tRNA bound to the large 60S subunit as a result of ribosome quality control mechanisms, is resolved by such mechanisms as addition of C-terminal alanyl-threonyl repeats (CAT-tailing) to the peptide by Rqc2 and its ubiquitination by Ltnl (Listerin in mammals: [173]), and cleavage of the peptidyl-tRNA. Vms1 (ANKZF1 in mammals) is a large ~600–750 aa peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase that dissociates 60S • peptidyl-tRNA complexes [174, 175], The sequence of its catalytic domain resembles that of eRF1 and features a GXQ (X=Ser294 in S. cerevisiae) motif with a functionally important glutamine [165, 174, 175], Despite this resemblance and some similarity to mitochondrial mtRF-R [98], Vms1 does not hydrolyze the ester bond of the peptidyl-tRNA. Instead, Vms1 cleaves the phosphodiester bond between nucleotides 73 and 74 of tRNA, separating CCA-peptide from the rest of tRNA [176, 177], The tRNA fragment gets repaired by ELAC1 and the CCA-adding enzyme TRNT1 [176, 178], Cryo-EM visualized Vms1 bound to the 60S subunit with an ABCF-type ATPase Arb1 next to tRNA (Fig. 3j) [165], Arb1 likely contributes to the positioning of peptidyl-tRNA substrate, thus enhancing the reaction efficiency [165], The catalytic domain of Vms1 is placed next to the tRNA (Fig. 3k) similarly to the M domain of Dom34 (Fig. 3i). The GSQ loop is disordered in the vicinity of the tRNA CCA end. The conserved neighboring Tyr285 stacks on the tRNA nucleotide 72, displacing nucleotide 73 and exposing the scissile phosphodiester bond for hydrolysis (Fig. 3k). Vms 1 spans over a large area on the intersubunit interface of the 60S subunit, in keeping with the role of Vms1 in coordinating peptidyl-tRNA hydrolysis with degradation of the aberrant peptide. The ankyrin-repeat and coiled-coil domains are directed toward the peptide exit tunnel, where the VIM domain likely contributes to Cdc48-mediated extraction and clearance of the peptide by proteasome [179–181], Future studies will provide details on how Vms1 cooperates with other proteins to dissociate the CCA-peptide and tRNA fragment from the 60S subunit, allowing to recycle the latter for translation of a new mRNA.

CONCLUSIONS

Recent studies uncovered many details of the termination and ribosome rescue mechanisms throughout the kingdoms of life. They demonstrate the diversity of peptide release scenarios catalyzed by proteins with different architectures. Some aspects of these scenarios remain to be visualized, but it is clear that the recognition and resolution of termination and stalled ribosome complexes strongly depends on the ribosome conformations and rearrangements, rendering the ribosome an active participant in all translation and quality control steps.

Acknowledgments.

I thank Anna Loveland and Darryl Conte Jr. for comments on the manuscript.

Funding.

This work was financially supported by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF; grant 670773) and by the National Institutes of Health (grant R35 GM127094).

Footnotes

Ethics declarations. The author declares no conflict of interest in financial or any other sphere. This article does not contain description of studies with humans participants or animals performed by the author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brenner S, Barnett L, Katz ER, and Crick FH (1967) UGA: a third nonsense triplet in the genetic code. Nature, 213, 449–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner S, Stretton AO, and Kaplan S (1965) Genetic code: the “nonsense” triplets for chain termination and their suppression, Nature, 206, 994–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spirin AS (1999) Termination of translation, in Ribosomes. Cellular Organelles, Springer, Boston, MA, pp. 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sogorin EA, Agalarov S, and Spirin AS (2016) Interpolysomal coupling of termination and initiation during translation in eukaryotic cell-free system, Sci. Rep, 6, 24518, doi: 10.1038/srep24518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tompkins RK, Scolnick EM, and Caskey CT (1970) Peptide chain termination. VII. The ribosomal and release factor requirements for peptide release, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 65, 702–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scolnick E, Tompkins R, Caskey T, and Nirenberg M (1968) Release factors differing in specificity for terminator codons, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 61, 768–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capecchi MR (1967) Polypeptide chain termination in vitro: isolation of a release factor, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 58, 1144–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capecchi MR (1967) A rapid assay for polypeptide chain termination, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 28, 773–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura Y, Ito K, Matsumura K, Kawazu Y, and Ebihara K (1995) Regulation of translation termination: conserved stmctural motifs in bacterial and eukaryotic polypeptide release factors, Biochem. Cell. Biol, 73, 1113–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frischmeyer PA, and Dietz HC (1999) Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in health and disease, Hum. MoL Genet, 8, 1893–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spirin AS (1969) A model of the functioning ribosome: locking and unlocking of the ribosome subparticles, Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol, 34, 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gavrilova LP, and Spirin AS (1972) Mechanism of translocation in ribosomes. II. Activation of spontaneous (nonenzymic) translocation in ribosomes of Escherichia coli by p-chloromercuribenzoate, MoL Biol, 6, 248–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Dyke N, and Murgola EJ (2003) Site of functional interaction of release factor 1 with the ribosome, J. MoL Biol, 330, 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouakaz L, Bouakaz E, Murgola EJ, Ehrenberg M, and Sanyal S (2006) The role of ribosomal protein L1 1 in class I release factor-mediated translation termination and translational accuracy, J. Biol. Chem, 281, 4548–4556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito K, Uno M, and Nakamura Y (2000) A tripeptide “anticodon” deciphers stop codons in messenger RNA, Nature, 403, 680–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oparina NJ, Kalinina OV, Gelfand MS, and Kisselev LL (2005) Common and specific amino acid residues in the prokaryotic polypeptide release factors RF1 and RF2: possible functional implications, Nucleic Acids Res, 33, 5226–5234, doi: 10.1093/nar/gki841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laurberg M, Asahara H, Korostelev A, Zhu J, Trakhanov S, and Noller HF (2008) Structural basis for translation termination on the 70S ribosome. Nature, 454, 852–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korostelev A, Asahara H, Lancaster L, Laurberg M, Hirschi A, et al. (2008) Crystal structure of a translation termination complex formed with release factor RF2, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105, 19684–19689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korostelev A, Zhu J, Asahara H, and Noller HF (2010) Recognition of the amber UAG stop codon by release factor RF1, EMBO J. 29, 2577–2585, doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weixlbaumer A, Jin H, Neubauer C, Voorhees RM, Petry S, et al. (2008) Insights into translational termination from the structure of RF2 bound to the ribosome, Science. 322, 953–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korkmaz G, and Sanyal S (2017) R213I mutation in release factor 2 (RF2) is one step forward for engineering an omnipotent release factor in bacteria Escherichia coli., J. Biol. Chem, 292, 15134–15142, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.785238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Field A, Hetrick B, Mathew M, and Joseph S (2010) Histidine 197 in release factor 1 is essential for a site binding and peptide release, Biochemistry, 49, 9385–9390, doi: 10.1021/bi1012047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frolova L, Le Goff X, Rasmussen HH, Cheperegin S, Drugeon G, et al. (1994) A highly conserved eukaryotic protein family possessing properties of polypeptide chain release factor, Nature, 372, 701–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frolova LY, Tsivkovskii RY, Sivolobova GF, Oparina NY, Serpinsky OI, et al. (1999) Mutations in the highly conserved GGQ motif of class 1 polypeptide release factors abolish ability of human eRF1 to trigger peptidyl-tRNA hydrolysis, RNA, 5, 1014–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw JJ, and Green R (2007) Two distinct components of release factor function uncovered by nucleophile partitioning analysis, Mol. Cell, 28, 458–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zavialov AV, Mora L, Buckingham RH, and Ehrenberg M (2002) Release of peptide promoted by the GGQ motif of class 1 release factors regulates the GTPase activity of RF3, Mol. Cell, 10, 789–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seit Nebi A, Frolova L, Ivanova N, Poltaraus A, and Kiselev L (2000) Mutation of a glutamine residue in the universal tripeptide GGQ in human eRF1 termination factor does not cause complete loss of its activity, Mol. Biol. (Mosk.), 34, 899–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seit-Nebi A, Frolova L, Justesen J, and Kisselev L (2001) Class-1 translation termination factors: invariant GGQ minidomain is essential for release activity and ribosome binding but not for stop codon recognition, Nucleic Acids Res, 29, 3982–3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santos N, Zhu J, Donohue JP, Korostelev AA, and Noller HF (2013) Crystal structure of the 70S ribosome bound with the Q253P mutant form of release factor RF2, Structure, 21, 1258–1263, doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korostelev AA (2011) Structural aspects of translation termination on the ribosome, RNA, 17, 1409–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunkle JA, and Cate JH (2010) Ribosome structure and dynamics during translocation and termination, Annu. Rev. Biophys, 39, 227–244, doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramakrishnan V (2011) Structural studies on decoding, termination and translocation in the bacterial ribosome, in Ribosomes: Structure, Function, and Dynamics (Rodnina M, Wintermeyer W, and Green R, eds.) Springer, pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodnina MV (2018) Translation in prokaryotes, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol, 10, doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a032664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Youngman EM, McDonald ME, and Green R (2008) Peptide release on the ribosome: mechanism and implications for translational control, Annu. Rev. Microbiol, 62, 353–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adio S, Sharma H, Senyushkina T, Karki P, Maracci C, et al. (2018) Dynamics of ribosomes and release factors during translation termination in E. coli, Elife, 7, doi: 10.7554/eLife.34252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prabhakar A, Capece MC, Petrov A, Choi J, and Puglisi JD (2017) Post-termination ribosome intermediate acts as the gateway to ribosome recycling, Cell Rep, 20, 161–172, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sternberg SH, Fei J, Prywes N, McGrath KA, and Gonzalez RL Jr. (2009) Translation factors direct intrinsic ribosome dynamics during translation termination and ribosome recycling, Nat. Struct. MoL Biol, 16, 861–868, doi: 10.1038/nsmb.l622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Indrisiunaite G, Pavlov MY, Heurgue-Hamard V, and Ehrenberg M (2015) On the pH dependence of class-1 RF-dependent termination of mRNA translation, J. MoL Biol, 427, 1848–1860, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin DH, Brandsen J, Jancarik J, Yokota H, Kim R, and Kim SH (2004) Structural analyses of peptide release factor 1 from Thermotoga maritima reveal domain flexibility required for its interaction with the ribosome, J. Mol. Biol, 341, 227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vestergaard B, Van LB, Andersen GR, Nyborg J, Buckingham RH, and Kjeldgaard M (2001) Bacterial polypeptide release factor RF2 is structurally distinct from eukaryotic eRF1, Mol. Cell, 8, 1375–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zoldak G, Redecke L, Svergun DI, Konarev PV, Voertler CS, et al. (2007) Release factors 2 from Escherichia coli and Thermits thermophilus: structural, spectroscopic and microcalorimetric studies. Nucleic Acids Res, 35, 1343–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.JCSG (2005) Crystal structure of Peptide chain release factor 1 (RF-1) (SMU.1085) from Streptococcus mutans at 2.34 A resolution, Protein Data Bank. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rawat UB, Zavialov AV, Sengupta J, Valle M, Grassucci RA, et al. (2003) A cryo-electron microscopic study of ribosome-bound termination factor RF2, Nature, 421, 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petry S, Brodersen DE, Murphy FV, Dunham CM, Selmer M, et al. (2005) Crystal structures of the ribosome in complex with release factors RF1 and RF2 bound to a cognate stop codon, Cell, 123, 1255–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He SL, and Green R (2010) Visualization of codon-dependent conformational rearrangements during translation termination, Nat. Struct. MoL Biol, 17, 465–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hetrick B, Lee K, and Joseph S (2009) Kinetics of stop codon recognition by release factor 1, Biochemistry, 48, 11178–11184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trappl K, and Joseph S (2016) Ribosome induces a closed to open conformational change in release factor 1, J. MoL Biol, 428, 1333–1344, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Svidritskiy E, and Korostelev AA (2018) Conformational control of translation termination on the 70S ribosome, Structure, 26, 821–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Demo G, Svidritskiy E, Madireddy R, Diaz-Avalos R, Grant T, et al. (2017) Mechanism of ribosome rescue by ArtAand RF2, Elife, 6, doi: 10.7554/eLife.23687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.James NR, Brown A, Gordiyenko Y, and Ramakrishnan V (2016) Translational termination without a stop codon, Science, 354, 1437–1440, doi: 10.1126/science.aai9127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fu Z, Indrisiunaite G, Kaledhonkar S, Shah B, Sun M,et al. (2019) The structural basis for release-factor activation during translation termination revealed by time-resolved cryogenic electron microscopy, Nat. Commun, 10, 2579, doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10608-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fislage M, Zhang J, Brown ZR, Mandava CS, Sanyal S, et al. (2018) Cryo-EM shows stages of initial codon selection on the ribosome by aa-tRNA in ternary complex with GTP and the GTPase-deficient EF-TuH84A, Nucleic Acids Res, 46, 5861–5874, doi: 10.1093/nar/gky346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ogle JM, Brodersen DE, Clemons WM Jr., Tarry MJ, Carter AR, and Ramakrishnan V (2001) Recognition of cognate transfer RNA by the 30S ribosomal subunit, Science, 292, 897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loveland AB, Demo G, Grigorieff N, and Korostelev AA (2017) Ensemble cryo-EM elucidates the mechanism of translation fidelity, Nature, 546, 113–117, doi: 10.1038/nature22397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amort M, Wotzel B, Bakowska-Zywicka K, Erlacher MD, Micura R, and Polacek N (2007) An intact ribose moiety at A2602 of 23 S rRNA is key to trigger peptidyl-tRNA hydrolysis during translation termination, Nucleic Acids Res, 35, 5130–5140, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Polacek N, Gomez MJ, Ito K, Xiong L, Nakamura Y, and Mankin A (2003) The critical role of the universally conserved A2602 of 23S ribosomal RNA in the release of the nascent peptide during translation termination, Mol. Cell, 11, 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Youngman EM, Brunelle JL, Kochaniak AB, and Green R (2004) The active site of the ribosome is composed of two layers of conserved nucleotides with distinct roles in peptide bond formation and peptide release. Cell, 117, 589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Graf M, Huter R, Maracci C, Peterek M, Rodnina MV, and Wilson DN (2018) Visualization of translation termination intermediates trapped by the Apidaecin 137 peptide during RF3-mediated recycling of RF1, Nat. Commun, 9, 3053, doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05465-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Florin T, Maracci C, Graf M, Karki R, Klepacki D, et al. (2017) An antimicrobial peptide that inhibits translation by trapping release factors on the ribosome, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol, 24, 752–757, doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Freistroffer DV, Pavlov MY, MacDougall J, Buckingham RH, and Ehrenberg M (1997) Release factor RF3 in E.coli accelerates the dissociation of release factors RF1 and RF2 from the ribosome in a GTP-dependent manner, EMBOJ, 16, 4126–4133, doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Svidritskiy E, Demo G, Loveland AB, Xu C, and Korostelev AA (2019) Extensive ribosome and RF2 rearrangements during translation termination, Elife, 8, e46850, doi: 10.7554/eLife.46850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ling C, and Ermolenko DN (2016) Structural insights into ribosome translocation, WIREs RNA, 7, 620–636, doi: 10.1002/wrna.l354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Noller HF, Lancaster L, Zhou J, and Mohan S (2017) The ribosome moves: RNA mechanics and translocation, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol, 24, 1021–1027, doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Voorhees RM, and Ramakrishnan V (2013) Structural basis of the translational elongation cycle, Annu. Rev. Biochem, 82, 203–236, doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-113009-092313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen J, Tsai A, O’Leary SE, Petrov A, and Puglisi JD (2012) Unraveling the dynamics of ribosome translocation, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol, 22, 804–814, doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frank J, and Gonzalez RL Jr. (2010) Structure and dynamics of a processive Brownian motor: the translating ribosome, Annu. Rev. Biochem, 79, 381–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Casy W, Prater AR, and Cornish PV (2018) Operative binding of Class I release factors and YaeJ stabilizes the ribosome in the nonrotated state, Biochemistry, 57, 1954–1966, doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jin H, Kelley AC, Loakes D, and Ramakrishnan V (2010) Structure of the 70S ribosome bound to release factor 2 and a substrate analog provides insights into catalysis of peptide release, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 8593–8598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wasserman MR, Alejo JL, Altman RB, and Blanchard SC (2016) Multiperspective smFRET reveals rate-determining late intermediates of ribosomal translocation, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol, 23, 333–341, doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cornish PV, Ermolenko DN, Noller HF, and Ha T (2008) Spontaneous intersubunit rotation in single ribosomes, Mol. Cell, 30, 578–588, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sharma H, Adio S, Senyushkina T, Belardinelli R, Peske F, and Rodnina MV (2016) Kinetics of spontaneous and EF-G-accelerated rotation of ribosomal subunits, Cell Rep, 16, 2187–2196, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blanchard SC, Kim HD, Gonzalez RL Jr., Puglisi JD, and Chu S (2004) tRNA dynamics on the ribosome during translation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 12893–12898, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403884101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Agirrezabala X, Lei J, Brunelle JL, Ortiz-Meoz RF, Green R, and Frank J (2008) Visualization of the hybrid state of tRNA binding promoted by spontaneous ratcheting of the ribosome, Mol. Cell, 32, 190–197, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Julian R, Konevega AL, Scheres SH, Lazaro M, Gil D, et al. (2008) Structure of ratcheted ribosomes with tRNAs in hybrid states, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 16924–16927, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809587105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou J, Lancaster L, Trakhanov S, and Noller HF (2012) Crystal structure of release factor RF3 trapped in the GTP state on a rotated conformation of the ribosome, RNA, 18, 230–240, doi: 10.126l/rna.031187.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ermolenko DN, Majumdar ZK, Hickerson RR, Spiegel PC, Clegg RM, and Noller HF (2007) Observation of intersubunit movement of the ribosome in solution using FRET, J. Mol. Biol, 370, 530–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gao H, Zhou Z, Rawat U, Huang C, Bouakaz L, et al. (2007) RF3 induces ribosomal conformational changes responsible for dissociation of class I release factors, Cell, 129, 929–941, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jin H, Kelley AC, and Ramakrishnan V (2011) Crystal structure of the hybrid state of ribosome in complex with the guanosine triphosphatase release factor 3, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 15798–15803, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112185108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leipe DD, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, and Aravind L (2002) Classification and evolution of P-loop GTPases and related ATPases, J. Mol. Biol, 317, 41–72, doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mikuni O, Ito K, Moffat J, Matsumura K, McCaughan K, et al. (1994) Identification of the prfC gene, which encodes peptide-chain-release factor 3 of Escherichia coli, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 5798–5802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grentzmann G, Brechemier-Baey D, Heurgue V, Mora L, and Buckingham RH (1994) Localization and characterization of the gene encoding release factor RF3 in Escherichia coli, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 5848–5852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pai RD, Zhang W, Schuwirth BS, Hirokawa G, Kaji H, et al. (2008) Structural insights into ribosome recycling factor interactions with the 70S ribosome, J. Mol. Biol,376, 1334–1347, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Borovinskaya MA, Pai RD, Zhang W, Schuwirth BS, Holton JM, et al. (2007) Structural basis for aminoglycoside inhibition of bacterial ribosome recycling, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol, 14, 727–732, doi: 10.1038/nsmbl271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ayyub SA, Gao F, Lightowlers RN, and Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM (2020) Rescuing stalled mammalian mitoribosomes — what can we learn from bacteria? J. Cell Sci, 133, doi: 10.1242/jcs.231811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Soleimanpour-Lichaei HR, Kuhl I, Gaisne M, Passos JF, Wydro M, et al. (2007) mtRFla is a human mitochondrial translation release factor decoding the major termination codons UAAand UAG, Mol. Cell, 27, 745–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nozaki Y, Matsunaga N, Ishizawa T, Ueda T, and Takeuchi N (2008) HMRF1L is a human mitochondrial translation release factor involved in the decoding of the termination codons UAA and UAG, Genes Cells, 13, 429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kummer E, Schubert KN, Schoenhut T, Scaiola A, and Ban N (2021) Structural basis of translation termination, rescue, and recycling in mammalian mitochondria, Mol. Cell, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Aibara S, Singh V, Modelska A, and Amunts A (2020) Structural basis of mitochondrial translation, Elife, 9, doi: 10.7554/eLife.58362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kummer E, and Ban N (2020) Structural insights into mammalian mitochondrial translation elongation catalyzed by mtEFG1, EMBO J, 39, e104820, doi: 10.15252/embj.2020104820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang Y, and Spremulli LL (1998) Identification and cloning of human mitochondrial translational release factor 1 and the ribosome recycling factor, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1443, 245–250, doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00223-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lind C, Sund J, and Aqvist J (2013) Codon-reading specificities of mitochondrial release factors and translation termination at non-standard stop codons, Nat. Commun, 4, 2940, doi: 10.1038/ncomms3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huynen MA, Duarte I, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM, and Nabuurs SB (2012) Structure based hypothesis of a mitochondrial ribosome rescue mechanism, Biol. Direct, 7, 14, doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Young DJ, Edgar CD, Murphy J, Fredebohm J, Poole ES, and Tate WP (2010) Bioinformatic, structural, and functional analyses support release factor-like MTRF1 as a protein able to decode nonstandard stop codons beginning with adenine in vertebrate mitochondria, RNA, 16, 1146–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Temperley R, Richter R, Dennerlein S, Lightowlers RN, and Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM (2010) Hungry codons promote frameshifting in human mitochondrial ribosomes, Science, 327, 301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ito K, Chadani Y, Nakamori K, Chiba S, Akiyama Y, and Abo T (2011) Nascentome analysis uncovers futile protein synthesis in Escherichia coli, PLoS One, 6, e28413, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hayes CS, and Keiler KC (2010) Beyond ribosome rescue: tmRNA and co-translational processes, FEBS Lett, 584, 413–419, doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Keiler KC (2015) Mechanisms of ribosome rescue in bacteria, Nat. Rev. Microbiol, 13, 285–297, doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Desai N, Yang H, Chandrasekaran V, Kazi R, Minczuk M, and Ramakrishnan V (2020) Elongational stalling activates mitoribosome-associated quality control, Science, 370, 1105–1110, doi: 10.1126/science.abc7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chadani Y, Ito K, Kutsukake K, and Abo T (2012) ArfA recruits release factor 2 to rescue stalled ribosomes by peptidyl-tRNA hydrolysis in Escherichia coli, MoL Microbiol, 86, 37–50, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shimizu Y (2012) ArtA recruits RF2 into stalled ribosomes, J. Mol. Biol, 423, 624–631, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zeng F, and Jin H (2016) Peptide release promoted by methylated RF2 and ArfA in nonstop translation is achieved by an induced-fit mechanism, RNA, 22, 49–60, doi: 10.1261/rna.053082.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Huter P, Muller C, Beckert B, Arenz S, Berninghausen O, et al. (2017) Structural basis for ArfA - RF2-mediated translation termination on mRNAs lacking stop codons, Nature, 541, 546–549, doi: 10.1038/nature20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ma C, Kurita D, Li N, Chen Y, Himeno H, and Gao N (2017) Mechanistic insights into the alternative translation termination by ArfA and RF2, Nature, 541, 550–553, doi: 10.1038/nature20822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zeng F, Chen Y, Remis J, Shekhar M, Phillips JC, et al. (2017) Structural basis of co-translational quality control by ArfA and RF2 bound to ribosome, Nature, 541, 554–557, doi: 10.1038/nature21053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Muller C, Crowe-McAuliffe C, and Wilson DN (2021) Ribosome rescue pathways in bacteria. Front. Microbiol, 12, 652980, doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.652980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shimokawa-Chiba N, Muller C, Fujiwara K, Beckert B, Ito K, et al. (2019) Release factor-dependent ribosome rescue by BrfA in the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus sub tilis, Nat. Commun, 10, 5397, doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13408-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Goralski TDP, Kirimanjeswara GS, and Keiler KC (2018) A new mechanism for ribosome rescue can recruit RF1 or RF2 to nonstop ribosomes, mBio, 9, doi: 10.1128/mBio.02436-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Burroughs AM, and Aravind L (2019) The origin and evolution of release factors: implications for translation termination, ribosome rescue, and quality control pathways, Int. J. Mol. Sci, 20, doi: 10.3390/ijms20081981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Handa Y, Inaho N, and Nameki N (2011) YaeJ is a novel ribosome-associated protein in Escherichia coli that can hydrolyze peptidyl-tRNA on stalled ribosomes, Nucleic Acids Res, 39, 1739–1748, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkql097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chan KH, Petrychenko V, Mueller C, Maracci C, Holtkamp W, et al. (2020) Mechanism of ribosome rescue by alternative ribosome-rescue factor B, Nat. Commun, 11, 4106, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17853-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Carbone CE, Demo G, Madireddy R, Svidritskiy E, and Korostelev AA (2020) ArfB can displace mRNA to rescue stalled ribosomes, Nat. Commun, 11, 5552, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19370-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gagnon MG, Seetharaman SV, Bulkley D, and Steitz TA (2012) Structural basis for the rescue of stalled ribosomes: structure of YaeJ bound to the ribosome, Science, 335, 1370–1372, doi: 10.1126/science.1217443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Richter R, Rorbach J, Pajak A, Smith PM, Wessels HJ, et al. (2010) Afunctional peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase, ICT1, has been recruited into the human mitochondrial ribosome, EMBOJ, 29, 1116–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Handa Y, Hikawa Y, Tochio N, Kogure H, Inoue M, et al. (2010) Solution structure of the catalytic domain of the mitochondrial protein ICT1 that is essential for cell vitality, J. Mol. Biol, 404, 260–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Feaga HA, Quickel MD, Hankey-Giblin PA, and Keiler KC (2016) Human cells require non-stop ribosome rescue activity in mitochondria, PLoS Genet, 12, e1005964, doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pan X, Tan J, Weng X, Du R, Jiang Y, et al. (2021) ICT1 Promotes osteosarcoma cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis via STAT3/BCL-2 pathway, Biomed. Res. Int, 2021, 8971728, doi: 10.1155/2021/8971728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Greber BJ, Boehringer D, Leitner A, Bieri R, Voigts-Hoffmann F, et al. (2014) Architecture of the large subunit of the mammalian mitochondrial ribosome, Nature, 505, 515–519, doi: 10.1038/naturel2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kater L, Mitterer V, Thoms M, Cheng J, Berninghausen O, et al. (2020) Construction of the central protuberance and LI stalk during 60S subunit biogenesis, Mol. Cell, 79, 615–628.e615, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nikolay R, Hilal T, Qin B, Mielke T, Burger J, et al. (2018) Structural visualization of the formation and activation of the 50S ribosomal subunit during in vitro reconstitution, Mol. Cell, 70, 881–893.e883, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.201805.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Davis JH, Tan YZ, Carragher B, Potter CS, Lyumkis D, and Williamson JR (2016) Modular assembly of the bacterial large ribosomal subunit, Cell, 167, 1610–1622.1615, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Huang S, Aleksashin NA, Loveland AB, Klepacki D, Reier K, et al. (2020) Ribosome engineering reveals the importance of 5S rRNA autonomy for ribosome assembly, Nat. Commun, 11, 2900, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16694-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Waltz F, Soufari H, Bochler A, Giege P, and Hashem Y (2020) Cryo-EM structure of the RNA-rich plant mitochondrial ribosome, Nat. Plants, 6, 377–383, doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0631-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Akabane S, Ueda T, Nierhaus KH, and Takeuchi N (2014) Ribosome rescue and translation termination at non-standard stop codons by ICT1 in mammalian mitochondria, PLoS Genet, 10, e 1004616, doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Vaishya S, Kumar V, Gupta A, Siddiqi MI, and Habib S (2016) Polypeptide release factors and stop codon recognition in the apicoplast and mitochondrion of Plasmodium falciparum, Mol. Microbiol, 100, 1080–1095, doi: 10.1111/mmi.13369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kogure H, Hikawa Y, Hagihara M, Tochio N, Koshiba S, et al. (2012) Solution structure and siRNA-mediated knockdown analysis of the mitochondrial disease-related protein C12orf65, Proteins, 80, 2629–2642, doi: 10.1002/prot.24152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Antonicka H, Ostergaard E, Sasarman F, Weraarpachai W, Wibrand F, et al. (2010) Mutations in C12orf65 in patients with encephalomyopathy and a mitochondrial translation defect, Am. J. Hum. Genet, 87, 115–122, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wesolowska M, Gorman GS, Alston CL, Pajak A, Pyle A, et al. (2015) Adult onset leigh syndrome in the intensive care setting: a novel presentation of a C12orf65 related mitochondrial disease, J. Neuromuscul. Dis, 2, 409–419, doi: 10.3233/JND-150121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zorkau M, Albus CA, Berlinguer-Palmini R, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZMA, and Lightowlers RN (2021) High-resolution imaging reveals compartmentalization of mitochondrial protein synthesis in cultured human cells, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 118, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2008778118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Chandrasekaran V, Juszkiewicz S, Choi J, Puglisi JD, Brown A, et al. (2019) Mechanism of ribosome stalling during translation of a poly(A) tail, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol, 26, 1132–1140, doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0331-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tesina P, Lessen LN, Buschauer R, Cheng J, Wu CC, et al. (2020) Molecular mechanism of translational stalling by inhibitory codon combinations and poly(A) tracts, EMBO J, 39, e103365, doi: 10.15252/embj.2019103365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Frolova L, Le Goff X, Zhouravleva G, Davydova E, Philippe M, and Kisselev L (1996) Eukaryotic polypeptide chain release factor eRF3 is an eRF1- and ribosome-dependent guanosine triphosphatase, RNA, 2, 334–341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Alkalaeva EZ, Pisarev AV, Frolova LY, Kisselev LL, and Pestova TV (2006) In vitro reconstitution of eukaryotic translation reveals cooperativity between release factors eRF1 andeRF3, Cell, 125, 1125–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Salas-Marco J, and Bedwell DM (2004) GTP hydrolysis by eRF3 facilitates stop codon decoding during eukaryotic translation termination, MoL Cell Biol, 24, 7769–7778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Frolova L, Seit-Nebi A, and Kisselev L (2002) Highly conserved NIKS tetrapeptide is functionally essential in eukaryotic translation termination factor eRF1, RNA, 8, 129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Muramatsu T, Heckmann K, Kitanaka C, and Kuchino Y (2001) Molecular mechanism of stop codon recognition by eRF1: a wobble hypothesis for peptide anti-codons, FEBS Lett, 488, 105–109, doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Bulygin KN, Popugaeva EA, Repkova MN, Meschaninova MI, Ven’yaminova AG, et al. (2007) The C domain of translation termination factor eRF1 is close to the stop codon in the A site of the 80S ribosome. Mol. Biol, 41, 781–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Brown A, Shao S, Murray J, Hegde RS, and Ramakrishnan V (2015) Structural basis for stop codon recognition in eukaryotes, Nature, 524, 493–496, doi: 10.1038/naturel4896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Brown CM, Stockwell PA, Trotman CN, and Tate WP (1990) Sequence analysis suggests that tetranucleotides signal the termination of protein synthesis in eukaryotes, Nucleic Acids Res, 18, 6339–6345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Matheisl S, Berninghausen O, Becker T, and Beckmann R (2015) Structure of a human translation termination complex, Nucleic Acids Res, 43, 8615–8626, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Jungreis I, Lin MF, Spokony R, Chan CS, Negre N, et al. (2011) Evidence of abundant stop codon readthrough in Drosophila and other metazoa, Genome Res, 21, 2096–2113, doi: 10.1101/gr.119974.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Swart EC, Serra V, Petroni G, and Nowacki M (2016) Genetic codes with no dedicated stop codon: context-dependent translation termination, Cell, 166, 691–702, doi: 10.1016/j.cell,2016.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Heaphy SM, Mariotti M, Gladyshev VN, Atkins JF, and Baranov PV (2016) Novel ciliate genetic code variants including the reassignment of all three stop codons to sense codons in Condylostoma magnum, MoL Biol. Evol, 33, 2885–2889, doi: 10.1093/molbev/mswl66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zahonova K, Kostygov AY, Sevcikova T, Yurchenko V, and Elias M (2016) An unprecedented non-canonical nuclear genetic code with all three termination codons reassigned as sense codons, Curr. Biol, 26, 2364–2369, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Anzalone AV, Zairis S, Lin AJ, Rabadan R, and Cornish VW (2019) Interrogation of eukaryotic stop codon readthrough signals by in vitro RNA selection, Biochemistry, 58, 1167–1178, doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b01280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Firth AE, Wills NM, Gesteland RF, and Atkins JF (2011) Stimulation of stop codon readthrough: frequent presence of an extended 3’ RNA structural element, Nucleic Acids Res, 39, 6679–6691, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Bonetti B, Fu L, Moon J, and Bedwell DM (1995) The efficiency of translation termination is determined by a synergistic interplay between upstream and downstream sequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, J. MoL Biol, 251, 334–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Harrell L, Melcher U, and Atkins JF (2002) Predominance of six different hexanucleotide recoding signals 3’ of read-through stop codons, Nucleic Acids Res, 30, 2011–2017, doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Shao S, Murray J, Brown A, Taunton J, Ramakrishnan V, and Hegde RS (2016) Decoding mammalian ribosome-mRNA states by translational GTPase complexes, Cell, 167, 1229–1240.e1215, doi: 10.1016/j.cell,2016.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Muhs M, Hilal T, Mielke T, Skabkin MA, Sanbonmatsu KY, et al. (2015) Cryo-EM of ribosomal 80S complexes with termination factors reveals the translocated cricket paralysis virus IRES, MoL Cell, 57, 422–432, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Des Georges A, Hashem Y, Unbehaun A, Grassucci RA, Taylor D, et al. (2014) Structure of the mammalian ribosomal pre-termination complex associated with eRF1.eRF3.GDPNP, Nucleic Acids Res, 42, 3409–3418, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Li W, Chang ST, Ward FR, and Cate JHD (2020) Selective inhibition of human translation termination by a drug-like compound, Nat. Commun, 11, 4941, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18765-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Preis A, Heuer A, Barrio-Garcia C, Hauser A, Eyler DE, et al. (2014) Cryoelectron microscopic structures of eukaryotic translation termination complexes containing eRF1-eRF3 or eRF1-ABCE1, Cell Rep, 8, 59–65, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep,2014.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Pisarev AV, Skabkin MA, Pisareva VR, Skabkina OV, Rakotondrafara AM, et al. (2010) The role of ABC E1 in eukaryotic posttermination ribosomal recycling, MoL Cell, 37, 196–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Annibaldis G, Domanski M, Dreos R, Contu L, Carl S, et al. (2020) Readthrough of stop codons under limiting ABCE1 concentration involves frameshifting and inhibits nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, Nucleic Acids Res, 48, 10259–10279, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Young DJ, Guydosh NR, Zhang F, Hinnebusch AG, and Green R (2015) Rli1/ABCE1 recycles terminating ribosomes and controls translation reinitiation in 3’-UTRs in vivo. Cell, 162, 872–884, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Lawson MR, Lessen LN, Wang J, Prabhakar A, Corsepius NC, et al. (2021) Mechanisms that ensure speed and fidelity in eukaryotic translation termination, bioRxiv, doi: 10.1101/2021.04.01.438116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Kryuchkova R, Grishin A, Eliseev B, Karyagina A, Frolova L, and Alkalaeva E (2013) Two-step model of stop codon recognition by eukaryotic release factor eRF 1, Nucleic Acids Res, 41, 4573–4586, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Svidritskiy E, Demo G, and Korostelev AA (2018) Mechanism of premature translation termination on a sense codon, J. Biol. Chem, 293, 12472–12479, doi: 10.1074/jbc.AW118.003232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Gouridis G, Hetzert B, Kiosze-Becker K, de Boer M, Heinemann H, et al. (2019) ABCE1 controls ribosome recycling by an asymmetric dynamic conformational equilibrium, Cell Rep, 28, 723–734.e726, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Heuer A, Gerovac M, Schmidt C, Trowitzsch S, Preis A, et al. (2017) Structure of the 40S-ABCE1 post-splitting complex in ribosome recycling and translation initiation, Nat. Struct. MoL Biol, 24, 453–460, doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]