Abstract

Cancer is predominantly a disease of aging, and older adults represent the majority of cancer diagnoses and deaths. Older adults with cancer differ significantly from younger patients, leading to important distinctions in cancer treatment planning and decision-making. As a consequence, the field of geriatric oncology has blossomed and evolved over recent decades, as the need to bring personalized cancer care to older adults has been increasingly recognized and a focus of study. The geriatric assessment (GA) has become the cornerstone of geriatric oncology research, and the past year has yielded promising results regarding the implementation of GA into routine cancer treatment decisions and outcomes for older adults. In this article, we provide an overview of the field of geriatric oncology and highlight recent breakthroughs with the use of GA in cancer care. Further work is needed to continue to provide personalized, evidence-based care for each older adult with cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Aging is one of the strongest and most predictable, yet completely unmodifiable, risk factors for the development of cancer. As such, cancer is predominantly a disease of aging, and older adults represent the majority of cancer diagnoses and deaths. The median age of cancer diagnosis is greater than 65 years in the United States, and the median age of cancer-related death is greater than 70 years.1,2 Additionally, as older adults represent an increasing proportion of the general population, as manifested over the past decade and as projected over upcoming years, this burden of cancer shared by older adults is expected to continue to grow.1,2

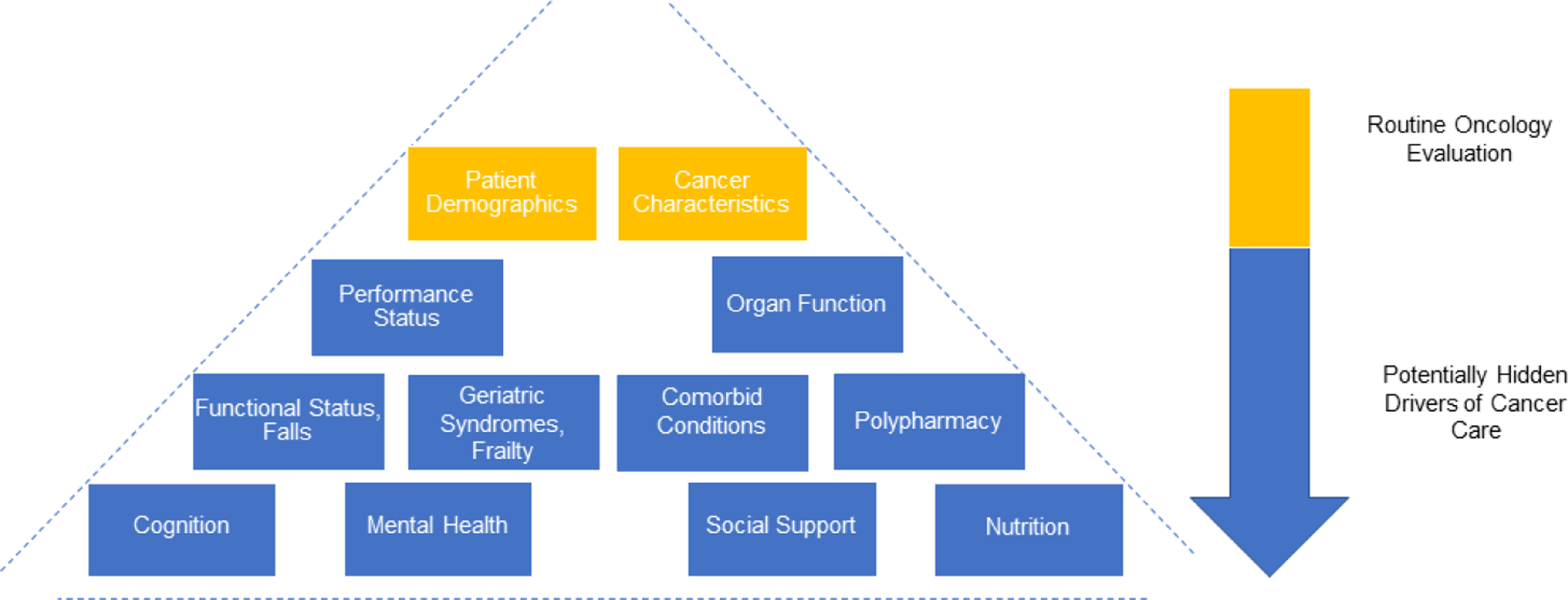

Older adults with cancer are heterogeneous and have wide variability in their health status and social support,3,4 thus necessitating a personalized approach to cancer therapy. Unfortunately, for decades, older adults, as well as patients who are frail, have comorbid medical conditions, or have reduced access to resources, have often been excluded from cancer clinical trials.5 As a result, the majority of the evidence in oncology is derived from younger, fit patients and critical challenges exist in how to extrapolate this data to older adults with cancer, often leading to over-treatment, under-treatment, or suboptimal outcomes.6 The development of comorbid conditions, presence of polypharmacy, increased rates of sarcopenia, malnutrition, and cognitive impairment, unpredictable changes in social support and resources, and alterations in pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics that accompany aging all must be considered in the care of older adults with cancer.6 Unfortunately, these factors may not be outwardly apparent to the oncology team (see Figure 1); therefore, a systematic and comprehensive patient evaluation with a multidisciplinary approach to older adults with cancer is essential.

Figure 1:

“Iceberg” concept of cancer care for older adults: factors may be hidden; based upon the work of Jolly et al., 2016.81

As a direct result of the overarching goal of providing evidence-based care for older adults with cancer, the distinct field of geriatric oncology has emerged, grown, and blossomed.7 Leaders from across the globe have dedicated their careers to improving the lives of older adults with cancer. In this review, we will highlight the history of the field of geriatric oncology, the development and implementation of geriatric assessment (GA), and future directions as the need for precision cancer care for older adults continues to evolve. In particular, we will focus our attention on breakthroughs in the field over recent years.

EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF THE FIELD OF GERIATRIC ONCOLOGY

The concept of geriatric oncology has grown exponentially over the past few decades to become an integral part of oncology care throughout the world. It is important to reflect on the pioneers who recognized this major gap in evidence and research and acted to form the esteemed organizations and international collegiate networks that underpin the specialty today (see Figure 2). Monfardini et al. provided an outstanding review of the history of geriatric oncology in the ASCO Post in 2020.8–10 In this article, we will highlight key events in the history of geriatric oncology, as shared below and in Figure 2. For a more comprehensive review of the history of the field, please see the ASCO Post series from Dr. Monfardini.

Figure 2.

Timeline of milestones in the field of geriatric oncology; based upon the work of Monfardini et al., 2020 and 2021.8–11

Since 1988, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has championed the field of geriatric oncology, in their annual meetings, training, and fellowship opportunities. Since 2004, ASCO also offers multiple courses related to geriatric oncology, including the assessment of older adults with cancer.11 The ASCO-Hartford geriatric oncology fellowships, established in 2001, are the largest and most well-known educational initiative to date to address the training of oncologists in caring for older adults.12 The ASCO annual conference remains a critical way for geriatric oncology research to be presented on an international stage; for example, the ASCO 2020 Annual Meeting provided a landmark platform for the presentation of four randomized controlled trials demonstrating the benefit of various models of GA driven care for older adults with cancer.13

Founded in 2000, the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) focuses on the three strategic directions of education, clinical practice, and research. SIOG has published over 40 guidelines, countless articles, and book contributions all related to older adults with cancer, as well as fostered interest groups such as Young SIOG and the Nursing and Allied Health interest group.11,14 SIOG develops educational opportunities, from modules to preceptorships and fellowships, and has a prominent advocacy role for older adults with cancer (https://www.siog.org). The SIOG Annual Conference annual general meeting has become an essential educational and networking opportunity in the geriatric oncology community. SIOG is instrumental in setting priorities for the geriatric oncology community and actively works to bridge organizations together from around the globe to advance the field.15

A noteworthy luminary of the field of geriatric oncology was Dr. Arti Hurria, the director of City of Hope’s Center for Cancer and Aging and founder of the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG). Dr. Arti Hurria dedicated her career to investigating and implementing GA as an improvement over traditional methods to appropriately assess vulnerability in older patients with cancer. As a National Institute on Aging Beeson Scholar, Board Member of ASCO, Co-Chair for the Alliance Cancer in the Elderly Committee, President of SIOG, and Chair of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Older Adult Oncology Committee, Dr. Hurria achieved the highest professional recognitions in both geriatrics and oncology while bridging the two fields.16 Although her life tragically ended in 2018, her legacy continues in the field, particularly in championing GA in oncology, and her exceptional mentorship has made an enduring impact to countless mentees and leaders in geriatric oncology.17

EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF THE GERIATRIC ASSESSMENT

Chronological age alone has traditionally been used for patient stratification in oncology, as well as a criterion in randomized clinical trials.18 However, older adults with cancer constitute a heterogeneous population, in which biological age and functional status often poorly correlate with chronological age alone.19,20 Applying objective criteria to assess physical function in addition to a provider’s clinical judgement and clinical performance scores - such as the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) and Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) - are widely used in oncology. However, these tools have limited utility to evaluate detailed health status or vulnerabilities in older adults.21

In contrast to the simple performance scores which provide a superficial description of physical performance, the appropriate assessment of older adults should include several domains to reveal potential vulnerabilities, including physical function, cognition, comorbidities, polypharmacy, nutrition, psychological status, social support, life expectancy, fatigue, and geriatric syndromes.22–24 This complex evaluation - termed GA - was first applied in the field of geriatric medicine. GA is a multidimensional interdisciplinary diagnostic process with a focus on medical, physiological, and functional capability in older vulnerable or frail patients, which also includes a coordinated and integrated plan for treatment and follow-up.25 The comprehensive and multidisciplinary management of older adults with cancer involves a broad spectrum of healthcare providers and caregivers from different professions, including, but not limited to, oncologists, geriatricians, nurses, dietitians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, psychologists, pharmacists, social workers, and audiologists.

Identifying impairments through GA allows the implementation of personalized interventions resulting in several substantial benefits and improved outcomes. The GA can identify deficits and abnormalities not revealed by medical history or physical examination, assist with decision-making, and provide estimates of survival.21,26–30 In addition, GA helps to reduce under-treatment and over-treatment, predict treatment-related toxicities, and improve physical and mental well-being in older adults with cancer.31–35

Within the past decade, GA has moved to the forefront of geriatric oncology, supported by professional organizations, as well as geriatric oncology pioneers and their mentees. The long-acknowledged benefits within geriatric medicine of establishing functional age rather than chronological age to guide holistic management has led to years of work of designing, modifying, and validating the GA for routine oncologic care for older adults.16,22,23,36,37

Integration of GA into routine oncology care and development of a cancer-specific GA has been long desired, though the widespread implementation faces several barriers.36 GA is considered complex and resource demanding. Thus, the implementation is a challenge, especially in areas and practices with limited time, training, and resources.38 In addition, relatively few geriatric specialty care providers exist in community oncology settings to facilitate such assessments.39 Therefore, several efforts have been made to develop brief, simple, cost-effective, and widely applicable GA tools for the oncology provider, as first pioneered by Dr. Hurria.36 Table 1 provides an overview of the key components of GA for oncology care, as well as screening tools for older adults with cancer. These tools can help identify the patients who will benefit from a GA and a more comprehensive approach to oncology care. SIOG and ASCO have also provided evidence-based recommendations to assist the oncology team with the use of geriatric screening and GA tools.22–24

Table 1.

Overview of geriatric screening and geriatric assessment – recommendations and common tools for measurement provided by the International Society of Geriatric Oncology and the American Society of Clinical Oncology

| RECOMMENDATIONS – Geriatric Screening | |

|---|---|

International Society of Geriatric Oncology:

| |

| Common Geriatric Screening Tools | |

| RECOMMENDATIONS – Geriatric Assessment | |

International Society of Geriatric Oncology:

| |

| Domains of Geriatric Assessment | Common tools for assessment |

|

Functional Status (Physical function, fall-tendency, sensory impairments, and performance status) |

|

| Objective Physical Performance |

|

| Cognition | |

| Social Support |

|

| Psychological Status |

|

| Nutrition | |

| Comorbidity |

|

| Geriatric-syndromes |

|

| Medication management & Polypharmacy |

|

| Fatigue |

|

| Chemotherapy toxicity prediction |

|

| Life expectancy |

|

Recommended tools by American Society of Clinical Oncology *

(Abbreviations: ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, ADL: Activities of Daily Living, IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, CARG: Cancer and Aging Research Group, CRASH: Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients, MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination, MOCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Mini-COG: mini-cognitive test)

To reduce the barriers in implementation of the GA, the development of self-reported and online versions of geriatric screening tools also played an important role in increasing the utility of GA in the clinical setting.40,41 Due to the limited time, resources, and availability of healthcare professionals, an essential first step is to identify and prioritize the most important concerns older adults with cancer are facing during the initial evaluation.42 The second step should be an in-depth analysis of the patient’s vulnerability or GA impairment, which can subsequently allow for multidisciplinary recommendations and interventions.42 There is an increasing availability of screening tools, such as Geriatric 8 (G8) and Vulnerable Elderly Survey-13, which can assist in identifying those that may benefit from a more comprehensive GA.43,44 Additionally, there is an increasing availability of tools that can be accessed online or in the form of mobile device application.45

GERIATRIC ASSESSMENT AS A PREDICTION TOOL

Development of chemotherapy risk assessment tools

A key role of GA is to help predict treatment outcomes and facilitate decision making. The role of GA in predicting chemotherapy toxicity has been of particular interest given the potential implications in treatment decisions and planning for older adults with cancer. The CARG Chemo-Toxicity Calculator and Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) toxicity tools were specifically developed as modifications of the GA to fill this need.16,33,34

Both the CARG and CRASH models incorporate key components of the GA, along with demographic and clinical characteristics, to compute a toxicity risk score. The CARG score was developed in a cohort of 500 older adults aged ≥65 years prior to systemic therapy initiation. Most patients had stage IV cancer (61%) and the most common cancer types included were lung (29%) and gastrointestinal (27%).34 Risk factors predictive of chemotherapy toxicity included age ≥72 years, tumor type (gastrointestinal/genitourinary), polychemotherapy, and standard treatment intensity, as well as GA variables such as hearing loss, falls, requiring help with medications, walking limitations, and reduced social activity; low hemoglobin and decreased creatinine clearance were also included. The CARG toxicity risk score outperformed physician-rated performance status in predicting severe chemotherapy toxicity.34 This model has undergone external validation46, has been translated into multiple languages and is available online.16

The CRASH toxicity tool is another risk score which predicts severe chemotherapy toxicity (overall, hematologic, and non-hematologic).33 The study included 518 older adults, aged ≥70 years, with predominantly lung (22%) and breast (22%) cancer, with the majority having stage IV disease (56%). Predictors of hematologic toxicity included diastolic blood pressure, dependence in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and a “chemotox” score, which refers to a risk of toxicity from different chemotherapy regimens (based on a previously developed and validated tool, the MAX2 index47). ECOG performance status, malnutrition as per Mini-Nutritional Assessment score, cognitive impairment using the Mini-Mental Status score, and chemotox score were predictors of non-hematologic toxicity.

The ability of both the CARG and CRASH tools to predict for chemotherapy toxicity has been confirmed in other studies.48,49 However, there are potential limitations. Both were developed in the United States at tertiary cancer centers and included a heterogeneous population of patients with a variety of cancer types, stages, and treatments. Some studies suggest that these tools may not be as predictive in other contexts, such as in other countries50,51, or in community settings.52 As such, ongoing work to test and validate these tools for use in in more homogeneous populations of adults with specific cancer types is necessary. For example, among older adults with lung cancer, the CARG tool was able to distinguish those at low, moderate, and high risk of chemotherapy toxicity.53 In a study of older women with early-stage breast cancer, modification of the CARG tool improved its ability to predict for chemotherapy toxicity.54 Several factors were modified in the CARG-breast cancer (CARG-BC) tool including cancer stage, use of anthracycline systemic therapy, planned chemotherapy duration, laboratory parameters, and select GA-variables. These disease-specific predictors likely contributed to the better predictive value CARG-BC demonstrated in this cohort, compared to the original CARG tool.

Development of GA and risk assessment tools for other cancer treatment modalities

Given the increasing use of non-chemotherapeutic systemic therapy agents (such as immunotherapy, targeted agents, and endocrine therapy), there is a growing interest in whether the CARG and CRASH tools are still applicable. One study of adults aged ≥65 years with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer found that the CARG tool was able to predict grade 3–5 toxicities in patients receiving abiraterone or enzalutamide.55 This remains an ongoing area of unmet need, particularly as cancer therapies continue to rapidly evolve in multiple areas of non-chemotherapeutic modalities.

In addition to non-chemotherapeutic systemic therapy, there is also an ongoing need to assess the role of GA for older adults with cancer who are receiving radiation therapy.56 A recent review by Shinde et al. highlighted the relative lack of data and the clear necessity for ongoing assessment and modification of the GA for older adults receiving radiation therapy.56 Many of the previous studies evaluating the GA as a predictive tool for older adults receiving radiation therapy have been limited by size and scope. Additionally, similar to the field of medical oncology, the widespread use of GA in radiation oncology has been relatively limited. For example, in a survey of radiation-oncologists who treat prostate cancer in older adults, approximately two-thirds of providers reported that they did not use any GA screening tools when assessing older adults.57 However, some studies have shown promising results for the use of GA for older adults receiving multimodality cancer care, including radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and surgery. For example, in a study by Neve et al. of 35 older adults with head and neck cancers, the G8 screening tool identified approximately half of the adults as “vulnerable” (defined by a G8 score ≤14).58 Vulnerable older adults were then referred for a more thorough GA, which included multidisciplinary evaluation, recommendations, and interventions during cancer therapy, although not all adults completed the GA. Vulnerable older adults who underwent GA trended towards improved length of hospital stay after surgery compared to those who did not undergo GA (6.2 days vs. 17.3 days, respectively; p-value not statistically significant).58 There is an ongoing need to continue this work, with modification of the GA and screening tools, as well as the development of randomized GA intervention trials, for older adults receiving radiation therapy and multimodality cancer therapy.56

Role of geriatric assessment in predicting mortality and adverse outcomes

In addition to chemotherapy toxicity, GA has been shown to be predictive of additional clinical outcomes important to older adults with cancer. Several studies have examined the association between GA impairments and survival. The 36-item Carolina Frailty Index, which was developed using the principle of deficit accumulation based on components of a cancer-specific GA, distinguished 5-year overall survival for adults categorized as frail (34%), pre-frail (58%) and robust (72%), with similar findings noted for cancer-specific mortality.59 In another study of over 6,000 older adults, a geriatric risk profile with the G8 screening tool was predictive of early mortality within three months (Odds Ratio 1.95, p=0.014) among older adults with cancer undergoing chemotherapy in addition to traditional clinical variables.60 Slow gait (defined by a “timed-up-and-go” test > 20 seconds) and poor nutrition (measured by the Mini Nutritional Assessment) were found to be predictive of early death within six months of commencement of chemotherapy in adults aged ≥70.61 Meanwhile, GA has also been shown to predict long-term health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in older women with breast cancer and frequency of hospitalizations and long-term care placement among older adults with cancer.62,63

The presence of functional decline is particularly important to older patients with cancer when making treatment decisions.64 Several studies have shown that baseline dependence in activities of daily living (ADLs and IADLs), depression, and poor nutrition are predictive of functional decline in older adults receiving chemotherapy.65,66 However, another study found that no GA domains were predictive of functional decline in older adults with lung cancer.67 Clearly, further work is needed to assess the relationship between GA and functional impairments for individual patient populations and treatment plans.

GERIATRIC ASSESSMENT GUIDED INTERVENTIONS

Recent evidence for the geriatric assessment

Given the gap between the established impact of the GA on cancer care and outcomes and its limited broad implementation into clinical practice, there is an ongoing need to develop structured frameworks to guide the integration of the GA into routine oncologic care.68,69 A Delphi study of geriatric oncology experts sought to gain a consensus on the use of GA in oncology, as well as to develop algorithms of GA-guided care processes for implementation into clinical practice.23 The consensus panel recognized the value of each domain of the GA, particularly given that management may center on non-pharmacologic interventions such as engagement of physical therapy and nutritional support. However, while previous studies established the GA as an assessment to identify patients at risk for adverse outcomes, more recent studies have explored targeted interventions based upon the findings of impairment from the GA.

Over the past year, multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) unequivocally demonstrated the benefits of GA and GA-guided interventions in reducing the toxicity of systemic cancer treatments and improving HRQOL for older adults.70–74 (see Table 2) The GAP-70 study evaluated whether providing a summary of the GA with GA-guided interventions to the oncology provider could reduce treatment-related toxicities.70 This study included 718 adults aged ≥70 years, with advanced malignancy and impairment in at least one GA domain. All patients had a GA at baseline, but the GA results and a set of GA-guided recommendations were provided to oncology providers only in the intervention arm. The primary endpoint was met with a 21% absolute risk reduction in grade 3–5 toxicities in the intervention arm (50% vs. 71%, p<0.01). These patients were more likely to receive dose reductions at cycle 1 (49% vs. 35%, p=0.016), without adversely affecting overall survival.

Table 2.

Recent geriatric assessment intervention trials

| STUDY | STUDY DESIGN | STUDY POPULATION | OVERALL OUTCOMES |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAP‐70 MOHILE et al. 70 | Intervention group: Oncology physician provided with a GA summary and GA‐guided recommendations. Usual care group: No summary provided to treating oncologists, patients treated according to standard of care. Community sites across U.S with geriatricians unavailable at the practice sites. |

n=718 patients (41 centers) Inclusion criteria: age >70, ≥1 impaired GA domain, solid tumors or lymphoma, starting a new line of cancer treatment. | Primary endpoint: Decreased incidence of G3-G5 chemotherapy toxicity at 3 months (50% vs. 71%, p<0.01). Secondary endpoints: No differences in 6‐month OS (OS 71% vs. 74%, p=0.33) |

| GAIN LI et al. 71 | Intervention group: multidisciplinary GA-driven interventions (physical therapy, nutrition, advanced care planning, occupational therapy, medication reconciliation, referrals for comorbidity care). Usual care group: GA provided to treating oncologist but no interventions offered. Academic center in the U.S. with availability of multidisciplinary team with a geriatric oncologist. |

n=600 patients Inclusion criteria: age ≥65, any functional status, solid tumors, all stages (71% stage IV), starting a new line of cancer treatment. |

Primary endpoint: Decreased incidence of G3-G5 chemotherapy toxicity (50.5% vs. 60.4%, p=0.02). Secondary endpoints: Increased advance directive completion (24% vs. 10%, p<0.01). No significant differences in healthcare utilization (emergency room visits, hospitalizations, length of stay). |

| INTEGERATE SOO et al. 72 | Intervention group: geriatrician-led GA and management integrated with oncogeriatric care. Usual care group: managed by oncologist alone. Three Australian centers with geriatricians available. |

n=154 patients Inclusion criteria: age ≥70, solid tumors and lymphoma, candidates for systemic therapy (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy). |

Primary endpoint: HRQOL better in the intervention group at week 18 (mean ELFI score 72.0 vs 58.7, p=0.001). Secondary endpoints: Reduced hospitalizations (41% less) and emergency room visits (39% less). Lower early treatment discontinuation due to adverse events (33% vs 53%, p=0.01). |

| QIAN et al. 73 | Intervention group: perioperative GA and GA-based recommendations available to the surgical/oncology teams. Usual care group: usual oncology care (do not meet a geriatrician). Single center in the U.S. with availability of geriatricians. |

n=160 patients Inclusion criteria: age ≥65, undergoing surgery for GI cancer, any functional status, all stages of malignancy. |

Primary endpoint: Post-operative length of stay - No differences in ITT analysis. Per‐protocol analysis: decreased hospital stay (8.2 vs. 5.9 days, p=0.02); decreased ICU admissions (32% vs. 13%, p=0.05). |

| GERICO LUND et al. 74 | Intervention group: GA in patients with G8 score ≤14, with GA-guided interventions. Usual care group: usual oncology care. Single center in Denmark. Geriatric assessments were performed by a geriatrician. |

n=142 patients Inclusion criteria: age ≥70, colorectal cancer, candidates for adjuvant or first-line palliative chemotherapy. |

Primary endpoint: more patients in the intervention arm completed scheduled chemotherapy without dose reductions or delays (45% vs. 28%, p=0.037). The beneficial effect of GA was mainly found in patients with G8 score ≤11 (OR 3.76, 95% CI: 1.19–13.45). Secondary endpoints: HRQOL improved in interventional arm with the decreased burden of illness (p=0.048) and improved mobility (p=0.008). |

Abbreviations: OS – overall survival; GA – geriatric assessment ; CGA – comprehensive geriatric assessment; ELFI - Elderly Functional Index; ITT – intent to treat; ICU – intensive care unit; OR – odds ratio; CI – confidence interval; health-related quality of life – HRQOL.

The second RCT, the GAIN trial, assessed the effect of GA-guided interventions by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) on treatment toxicities.71 This study included 600 adults aged ≥65 years, with all stages of malignancy. Patients underwent GA at baseline. In the intervention arm, the MDT reviewed the GA results and proposed an intervention plan. The study showed a 10% reduction in grade 3–5 toxicities in the intervention arm (50% vs. 60%). There was also an increase in advance directive completion.

The INTEGERATE study examined the effect of a geriatrician-led comprehensive GA on HRQOL in adults aged ≥70 years with cancer.72 The primary endpoint was assessed using the Elderly Functional Index (ELFI) score. There was an improvement in ELFI scores in the intervention arm at 18 weeks (72 vs. 59, p=0.001). A 41% reduction in hospital admissions and less treatment discontinuation due to adverse events were also observed.

A study on the role of GA in the perioperative period for older adults aged ≥65 years with gastrointestinal malignancy (n=160) was also presented at the ASCO Annual Meeting in 2020.73 Patients were randomized to usual care or to a geriatrician-based evaluation in the pre- and post-operative period. GA-guided recommendations were provided to the surgical and oncology teams. Lower depressive symptoms and lower burden of symptoms post-operatively were reported. Although the primary endpoint of hospital length of stay (LOS) was not met in the intention-to-treat analysis, in the per-protocol analysis, a shorter LOS (5.9 vs. 8.2 days, p=0.02) and lower post-operative intensive care unit use (13% vs. 32%, p=0.05) were observed.

Recently, the GERICO randomized phase 3 trial investigated whether GA-based interventions in vulnerable older adults with colorectal cancer could increase the number of patients completing scheduled chemotherapy.74 This study included 142 adults aged ≥70 years, who were planned to receive adjuvant or first-line palliative chemotherapy. Vulnerable patients (defined as having a G8 questionnaire score ≤ 14) were randomized to GA-based interventions or usual care. In the intervention arm, more patients completed scheduled chemotherapy without dose reductions or delays compared with the control arm (45% vs. 28%, p=0.037). This benefit was more prominent in patients in the adjuvant setting and for those with G8 scores < 11. An improvement in HRQOL was also noted.

Modification to cancer treatments and decision-making

Decision-making for older adults with cancer can be complex and multi-layered, involving patient and family values, changes in physiology and fitness of aging, and cancer diagnostic and therapeutic concerns. This process can be potentially improved by incorporating the GA into routine oncology care, with the goal of improving the precision of cancer therapy.75

Several studies have examined the impact of GA on cancer treatment decisions. For example, in a small study of adults aged ≥70 years with lung or gastrointestinal cancer, GA prior to treatment decisions impacted the cancer care plan in 83% of patients.76 The GA results more commonly led to a decrease in the aggressiveness of treatments, especially systemic therapies. In a thoracic oncology study, almost half of treatment (45%) decisions were modified by geriatric multimodal assessment.77 In addition, using the GA to allocate appropriate cancer treatments to older adults is an area of ongoing interest with mixed results to date.78,79 Additional work is needed to assess the optimal timing and implementation of GA to more fully assess its impact on cancer treatment decisions.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

As the global population continues to age and as older adults share an increasing burden of cancer morbidity and mortality, there is significant need to adapt all aspects of cancer care to the older adult population. This is particularly true in the age of precision oncology, as new cancer trials and therapeutics must be specifically designed, modified, studied, and validated for older adults.

The recognition of this ever-growing necessity to provide optimal care for older adults with cancer, in an area that has traditionally lacked clear and objective medical evidence, led to the development of field of geriatric oncology. Over previous decades and recent years, the field has flourished, based upon the work of pioneering patients and leaders, dedicated clinicians and researchers, and evolving multidisciplinary teams. Currently, the field has produced widely available evidence-based recommendations, screening tools, and GA interventions for the oncology team. In addition, multiple studies presented over the past year have highlighted promising benefits of the incorporation of GA into routine oncologic care for older adults. We must continue to move past the traditional use of chronologic age and performance status when assessing patients, developing cancer treatment plans, and designing clinical trials, as aging is a truly heterogeneous process. All aspects of care, including patient preferences, quality of life, and all geriatric domains must be taken into consideration in order to provide individualized and patient-centered care. The GA now stands out as the opportunity to create truly personalized care for older adults with cancer.

In response to the evolving evidence clearly demonstrating the utility of the GA in making cancer treatment decisions for older adults, the GA is now recommended for ALL older adults with a new cancer diagnosis, per recommendations from ASCO24, NCCN80, and SIOG.22 Further work is needed to understand and overcome barriers to the broad implementation and utilization of the GA, as evidence of the potential benefits of GA in routine oncologic care continues to advance. As the number of older adults with cancer continues to grow, and as the complexity of cancer treatment continues to progress, we must focus on providing efficient and effective, personalized, precise, evidence-based care to every older adult.

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K08CA234225). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflict to disclose relevant to this submitted article.

References:

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016/ , based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. In. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(17):2758–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balducci L, Beghe C. The application of the principles of geriatrics to the management of the older person with cancer. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2000;35(3):147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams GR, Pisu M, Rocque GB, et al. Unmet social support needs among older adults with cancer. Cancer. 2019;125(3):473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocque GB, Williams GR. Bridging the Data-Free Zone: Decision Making for Older Adults With Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37(36):3469–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurria A, Levit LA, Dale W, et al. Improving the Evidence Base for Treating Older Adults With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(32):3826–3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klepin HD, Wildes TM. Geriatric Oncology: Getting Even Better with Age. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2019;67(5):871–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monfardini SBL, Overcash J, Aapro M. Cancer in Older Adults: The History of Geriatric Oncology, Part 3. Geriatric Oncology Nurses in the Care of Elderly Patients With Cancer. The ASCO Post. 2020. Nov 10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monfardini SBL, Overcash J, Aapro M. Cancer in Older Adults: The History of Geriatric Oncology, 1980–2015, Part 1. The ASCO Post. 2020. Oct 10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monfardini SBL, Overcash J, Aapro M. Cancer in Older Adults: The History of Geriatric Oncology, Part 2: 1990–2020. The ASCO Post. 2020. Oct 25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monfardini S, Balducci L, Overcash J, Aapro M. Landmarks in geriatric oncology. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu T Educational initiatives in geriatric oncology - Who, why, and how? J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(5):390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giri S, Chakiba C, Shih YY, et al. Integration of geriatric assessment into routine oncologic care and advances in geriatric oncology: A young International Society of Geriatric Oncology Report of the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(8):1324–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.About us. International Society of Geriatric Oncology. https://www.siog.org/content/about-us. In:2015.

- 15.Extermann M, Brain E, Canin B, et al. Priorities for the global advancement of care for older adults with cancer: an update of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology Priorities Initiative. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(1):e29–e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DuMontier C, Sedrak MS, Soo WK, et al. Arti Hurria and the progress in integrating the geriatric assessment into oncology: Young International Society of Geriatric Oncology review paper. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(2):203–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnuson A, Li D, Hsu T, et al. Mentoring pearls of wisdom: Lessons learned by mentees of Arti Hurria, MD. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2020;11(2):335–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sedrak MS, Freedman RA, Cohen HJ, et al. Older adult participation in cancer clinical trials: A systematic review of barriers and interventions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):78–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Li D, Yuan Y, Lau YM, Hurria A. Functional versus chronological age: geriatric assessments to guide decision making in older patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(6):e305–e316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giri S, Al-Obaidi M, Weaver A, et al. Association Between Chronologic Age and Geriatric Assessment-Identified Impairments: Findings From the CARE Registry. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2021:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jolly TA, Deal AM, Nyrop KA, et al. Geriatric assessment-identified deficits in older cancer patients with normal performance status. Oncologist. 2015;20(4):379–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(24):2595–2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohile SG, Velarde C, Hurria A, et al. Geriatric Assessment-Guided Care Processes for Older Adults: A Delphi Consensus of Geriatric Oncology Experts. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(9):1120–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(22):2326–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubenstein LZ, Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland D. Impacts of geriatric evaluation and management programs on defined outcomes: overview of the evidence. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1991;39(9 Pt 2):8S–16S; discussion 17S-18S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Repetto L, Fratino L, Audisio RA, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment adds information to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status in elderly cancer patients: an Italian Group for Geriatric Oncology Study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(2):494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirkhus L, Saltyte Benth J, Rostoft S, et al. Geriatric assessment is superior to oncologists’ clinical judgement in identifying frailty. British journal of cancer. 2017;117(4):470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamaker ME, Vos AG, Smorenburg CH, de Rooij SE, van Munster BC. The value of geriatric assessments in predicting treatment tolerance and all-cause mortality in older patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2012;17(11):1439–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamaker ME, Schiphorst AH, ten Bokkel Huinink D, Schaar C, van Munster BC. The effect of a geriatric evaluation on treatment decisions for older cancer patients--a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(3):289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giantin V, Valentini E, Iasevoli M, et al. Does the Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI), based on a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), predict mortality in cancer patients? Results of a prospective observational trial. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(3):208–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DuMontier C, Loh KP, Bain PA, et al. Defining Undertreatment and Overtreatment in Older Adults With Cancer: A Scoping Literature Review. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(22):2558–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Decoster L, Kenis C, Van Puyvelde K, et al. The influence of clinical assessment (including age) and geriatric assessment on treatment decisions in older patients with cancer. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2013;4(3):235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, et al. Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. Cancer. 2012;118(13):3377–3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3457–3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magnuson A, Allore H, Cohen HJ, et al. Geriatric assessment with management in cancer care: Current evidence and potential mechanisms for future research. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2016;7(4):242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, et al. Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: a feasibility study. Cancer. 2005;104(9):1998–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurria A, Levit LA, Dale W, et al. Improving the Evidence Base for Treating Older Adults With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3826–3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dale W, Williams GR, A RM, et al. How Is Geriatric Assessment Used in Clinical Practice for Older Adults With Cancer? A Survey of Cancer Providers by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020:OP2000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams GR, Weaver KE, Lesser GJ, et al. Capacity to Provide Geriatric Specialty Care for Older Adults in Community Oncology Practices. The oncologist. 2020;25(12):1032–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guerard E, Dodge AB, Le-Rademacher JG, et al. Electronic Geriatric Assessment: Is It Feasible in a Multi-Institutional Study That Included a Notable Proportion of Older African American Patients? (Alliance A171603). JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2021;5:435–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams GR, Kenzik KM, Parman M, et al. Integrating geriatric assessment into routine gastrointestinal (GI) consultation: The Cancer and Aging Resilience Evaluation (CARE). Journal of geriatric oncology. 2020;11(2):270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sattar S, Alibhai SM, Wildiers H, Puts MT. How to implement a geriatric assessment in your clinical practice. Oncologist. 2014;19(10):1056–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Walree IC, Vondeling AM, Vink GR, et al. Development of a self-reported version of the G8 screening tool. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(6):926–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Decoster L, Van Puyvelde K, Mohile S, et al. Screening tools for multidimensional health problems warranting a geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: an update on SIOG recommendationsdagger. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2015;26(2):288–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hurria A, Akiba C, Kim J, et al. Reliability, Validity, and Feasibility of a Computer-Based Geriatric Assessment for Older Adults With Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(12):e1025–e1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hurria A, Mohile S, Gajra A, et al. Validation of a Prediction Tool for Chemotherapy Toxicity in Older Adults With Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20):2366–2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Extermann M, Bonetti M, Sledge GW, O’Dwyer PJ, Bonomi P, Benson AB. MAX2--a convenient index to estimate the average per patient risk for chemotherapy toxicity; validation in ECOG trials. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(8):1193–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ortland I, Mendel Ott M, Kowar M, et al. Comparing the performance of the CARG and the CRASH score for predicting toxicity in older patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(6):997–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J, Liao X, Feng J, Yin T, Liang Y. Prospective comparison of the value of CRASH and CARG toxicity scores in predicting chemotherapy toxicity in geriatric oncology. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(5):4947–4955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan WL, Ma T, Cheung KL, et al. The predictive value of G8 and the Cancer and aging research group chemotherapy toxicity tool in treatment-related toxicity in older Chinese patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(4):557–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moth EB, Kiely BE, Martin A, et al. Older adults’ preferred and perceived roles in decision-making about palliative chemotherapy, decision priorities and information preferences. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(4):626–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mariano C, Jamal R, Bains P, et al. Utility of a chemotherapy toxicity prediction tool for older patients in a community setting. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(4):234–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nie X, Liu D, Li Q, Bai C. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with lung cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(4):334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Magnuson A, Sedrak MS, Gross CP, et al. Development and Validation of a Risk Tool for Predicting Severe Toxicity in Older Adults Receiving Chemotherapy for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(6):608–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alibhai SMH, Breunis H, Hansen AR, et al. Examining the ability of the Cancer and Aging Research Group tool to predict toxicity in older men receiving chemotherapy or androgen-receptor-targeted therapy for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shinde A, Vazquez J, Novak J, Sedrak MS, Amini A. The role of comprehensive geriatric assessment in radiation oncology. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(2):194–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zereshkian A, Cao X, Puts M, et al. Do Canadian Radiation Oncologists Consider Geriatric Assessment in the Decision-Making Process for Treatment of Patients 80 years and Older with Non-Metastatic Prostate Cancer? - National Survey. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(4):659–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neve M, Jameson MB, Govender S, Hartopeanu C. Impact of geriatric assessment on the management of older adults with head and neck cancer: A pilot study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(6):457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guerard EJ, Deal AM, Chang Y, et al. Frailty Index Developed From a Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment and the Association With Mortality Among Older Adults With Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(7):894–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quinten C, Kenis C, Decoster L, et al. The prognostic value of patient-reported Health-Related Quality of Life and Geriatric Assessment in predicting early death in 6769 older (≥70 years) patients with different cancer tumors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(6):926–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soubeyran P, Fonck M, Blanc-Bisson C, et al. Predictors of early death risk in older patients treated with first-line chemotherapy for cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1829–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams GR, Deal AM, Sanoff HK, et al. Frailty and health-related quality of life in older women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(7):2693–2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Williams GR, Dunham L, Chang Y, et al. Geriatric Assessment Predicts Hospitalization Frequency and Long-Term Care Use in Older Adult Cancer Survivors. Journal of oncology practice / American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2019:JOP1800368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nightingale G, Battisti NML, Loh KP, et al. Perspectives on functional status in older adults with cancer: An interprofessional report from the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) nursing and allied health interest group and young SIOG. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(4):658–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoppe S, Rainfray M, Fonck M, et al. Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(31):3877–3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kenis C, Decoster L, Bastin J, et al. Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy: A multicenter prospective study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8(3):196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Decoster L, Kenis C, Schallier D, et al. Geriatric Assessment and Functional Decline in Older Patients with Lung Cancer. Lung. 2017;195(5):619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McKenzie GAG, Bullock AF, Greenley SL, Lind MJ, Johnson MJ, Pearson M. Implementation of geriatric assessment in oncology settings: A systematic realist review. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2021;12(1):22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Conroy SP, Bardsley M, Smith P, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for frail older people in acute hospitals: the HoW-CGA mixed-methods study. 2019. [PubMed]

- 70.Mohile SG, Mohamed MR, Culakova E, et al. A geriatric assessment (GA) intervention to reduce treatment toxicity in older patients with advanced cancer: A University of Rochester Cancer Center NCI community oncology research program cluster randomized clinical trial (CRCT). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38(15_suppl):12009–12009. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li D, Sun C-L, Kim H, et al. Geriatric assessment-driven intervention (GAIN) on chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38(15_suppl):12010–12010. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soo W-K, King M, Pope A, Parente P, Darzins P, Davis ID. Integrated geriatric assessment and treatment (INTEGERATE) in older people with cancer planned for systemic anticancer therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38(15_suppl):12011–12011. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qian CL, Knight HP, Ferrone CR, et al. Randomized trial of a perioperative geriatric intervention for older adults with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38(15_suppl):12012–12012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lund CM, Vistisen KK, Olsen AP, et al. The effect of geriatric intervention in frail older patients receiving chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: a randomised trial (GERICO). Br J Cancer. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Glatzer M, Panje CM, Siren C, Cihoric N, Putora PM. Decision Making Criteria in Oncology. Oncology. 2020;98(6):370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Horgan AM, Leighl NB, Coate L, et al. Impact and feasibility of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in the oncology setting: a pilot study. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35(4):322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aliamus V, Adam C, Druet-Cabanac M, Dantoine T, Vergnenegre A. [Geriatric assessment contribution to treatment decision-making in thoracic oncology]. Rev Mal Respir. 2011;28(9):1124–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gajra A, Loh KP, Hurria A, et al. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment-Guided Therapy Does Improve Outcomes of Older Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(33):4047–4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Corre R, Greillier L, Le Caer H, et al. Use of a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment for the Management of Elderly Patients With Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: The Phase III Randomized ESOGIA-GFPC-GECP 08–02 Study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(13):1476–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Older Adult Oncology (Version 1.2020). Published 2020. Accessed. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Jolly TA, Williams GR, Bushan S, et al. Adjuvant treatment for older women with invasive breast cancer. Womens Health (Lond). 2016;12(1):129–145; quiz 145–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]