Abstract

Objective:

High rates of partial insertion have been reported for cochlear implant (CI) recipients of long lateral wall electrode arrays, presumably caused by resistance encountered during insertion due to cochlear morphology. With recent advances in long-electrode array design, we sought to investigate 1) the incidence of complete insertions among patients implanted with 31.5 mm flexible arrays and 2) whether complete insertion is limited by cochlear duct length (CDL).

Study Design:

Retrospective review.

Setting:

Tertiary referral center.

Methods:

Fifty-one adult CI recipients implanted with 31.5 mm flexible lateral wall arrays underwent postoperative computed tomography to determine the rate of complete insertion, defined as all contacts being intracochlear. CDL and angular insertion depth (AID) were compared between complete and partial insertion cohorts.

Results:

The majority of cases had a complete insertion (96.1%, n=49). Among the complete insertion cohort, the median CDL was 33.6 mm (range: 30.3–37.9 mm), and median AID was 641° (range: 533–751°). Two cases of partial insertion had relatively short CDL (31.8 mm and 32.3 mm) and shallow AID (542° and 575°). Relatively shallow AID for the two cases of partial insertion fail to support the idea that CDL alone prevents a complete insertion.

Conclusion:

Complete insertion of a 31.5 mm flexible array is feasible in most cases and does not appear to be limited by the range of CDL observed in this cohort. Future studies are needed to estimate other variations in cochlear morphology that could predict resistance and failure to achieve complete insertion with long arrays.

Keywords: Cochlear implant, FlexSOFT, cochlear morphology, cochlear duct length, angular insertion depth

INTRODUCTION

Cochlear implantation has provided an effective treatment option for patients with moderate-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss and limited benefit from appropriately fit acoustic amplification. Despite substantial advances in the field, speech recognition outcomes with a cochlear implant (CI) remain highly variable1–5. One factor that might contribute to this variability involves the spatial distribution of electrodes throughout the cochlea. More specifically, prior work has focused on elucidating the relationship between insertion depth of the electrode array and speech recognition outcomes. However, controversy still exists as some studies have demonstrated a speech recognition benefit with deeper insertions6–12, whereas others have shown either no effect or a decrement in performance1,4,13–15.

While still an active area of investigation, emerging evidence suggests that some discrepancy in the effects of insertion depth could be driven by factors related to array design (i.e., lateral wall versus pre-curved)9,16. For lateral wall arrays, longer arrays and deeper AIDs appear to confer performance benefit, presumably due to the closer tonotopic alignment when using default frequency filters17–23 and greater channel independence associated with increased contact spacing when compared to shorter lateral wall arrays22. Pre-curved arrays, which are relatively shorter than most lateral wall arrays, benefit from closer proximity to the neural substrate and shallower insertions optimize the distance between electrode contacts and the modiolus9,14,24.

With respect to lateral wall arrays, O’Connell et al.7 previously reported a positive linear correlation between AID and consonant-nucleus-consonant (CNC) word scores in quiet assessed in the CI-alone condition. Similarly, Buchman et al.8 conducted a prospective trial that randomized conventional CI recipients to receive either a MED-EL GmbH (Innsbruck, Austria) Standard (31.5 mm) or Medium (24 mm) array, and the study was discontinued based on an emerging trend for better speech recognition for the longer array cohort. The addition of data from Standard array recipients who were implanted during the study period but not enrolled in the trial resulted in significantly better speech recognition observed for recipients of the Standard array as compared to recipients of the Medium array. Subsequent examination of long-term data from this sample revealed that Medium array recipients continued to perform more poorly than Standard recipients even after several years of CI use25.

Though the results of Buchman et al.8 highlight the benefit of a deeper insertion achieved with a 31.5 mm lateral wall array in comparison to a 24 mm array, a complete insertion of a longer array may not always be possible due to substantial variability in cochlear morphology26–30. Resistance may be encountered during array insertion under two conditions: 1) a cochlear duct length (CDL) that is too short to accommodate the array, and 2) contact between the array and basilar membrane, which increases in likelihood with greater angular distance due to narrowing of the scala tympani29. Timm et al.31 estimated that 28 mm arrays may only be completely inserted in 76% of cases due to limitations in CDL, which could be expected given that CDL at the organ of Corti has been shown to range from 24 to 40.1 mm30. Similarly, some reports indicate partial insertion rates as high as 32% with the previous generation Standard 31.5 mm array32. With development of the MED-EL FlexSOFT array, a more flexible 31.5 mm array with 5 unpaired contacts allowing for a smaller apical diameter, it is possible that partial insertion rates are not as high as those observed with the previous generation Standard array. The aims of the present study were to investigate 1) the incidence of complete insertions among patients implanted with a 31.5 mm flexible lateral wall array determined by postoperative computed tomography (CT), and 2) whether a complete insertion is limited by CDL.

METHODS

Subjects

The Biomedical Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill approved the retrospective review of adult CI recipients who were implanted with a MED-EL FlexSOFT lateral wall electrode array by one of four surgeons (protocol #09–2328). The FlexSOFT array is 31.5 mm in length and carries 12 evenly spaced contacts over 26.4 mm. In contrast to the prior generation Standard (31.5 mm) array, the 5 most apical contacts are unpaired, increasing flexibility and reducing apical diameter. All subjects underwent a standard posterior tympanotomy approach with a round window insertion and postoperative CT of the temporal bone. Exclusion criteria were evidence of cochlear malformation on review of preoperative imaging or cases of revision surgery. During the study period, preoperative measurement of CDL was not used in the electrode array selection process. The postoperative CT of each subject was reviewed to identify cases of partial insertion (e.g., at least 1 extracochlear electrode contact), and to calculate AID and CDL.

Measurement of Angular Insertion Depth

Cone-beam CT of the temporal bone (resolution 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.2 mm) was obtained at the initial postoperative visit (2–4 weeks postoperatively) and subsequently analyzed with OTOPLAN®, an imaging tool developed by CAScination AG (Bern, Switzerland) in cooperation with MED-EL. The analysis methodology was previously described33. Briefly, a user-defined cochlear view was established34, and the mid-modiolar axis, center of the round window, and most apical electrode contact were manually identified to calculate AID. In the present study, landmarks were all determined by the first author.

Measurement of Cochlear Duct Length

Cochlear duct length at the organ of Corti was estimated with CT using the elliptic-circular approximation (ECA) method35. This approach built upon previous work of Alexiades et al.36, which analyzed data from cochlear specimens reported by Hardy26, and found the relationship between basal turn length (BTL) and CDL to be described by Equation 1:

| (1) |

The ECA method determines BTL (in mm) by Equation 2:

| (2) |

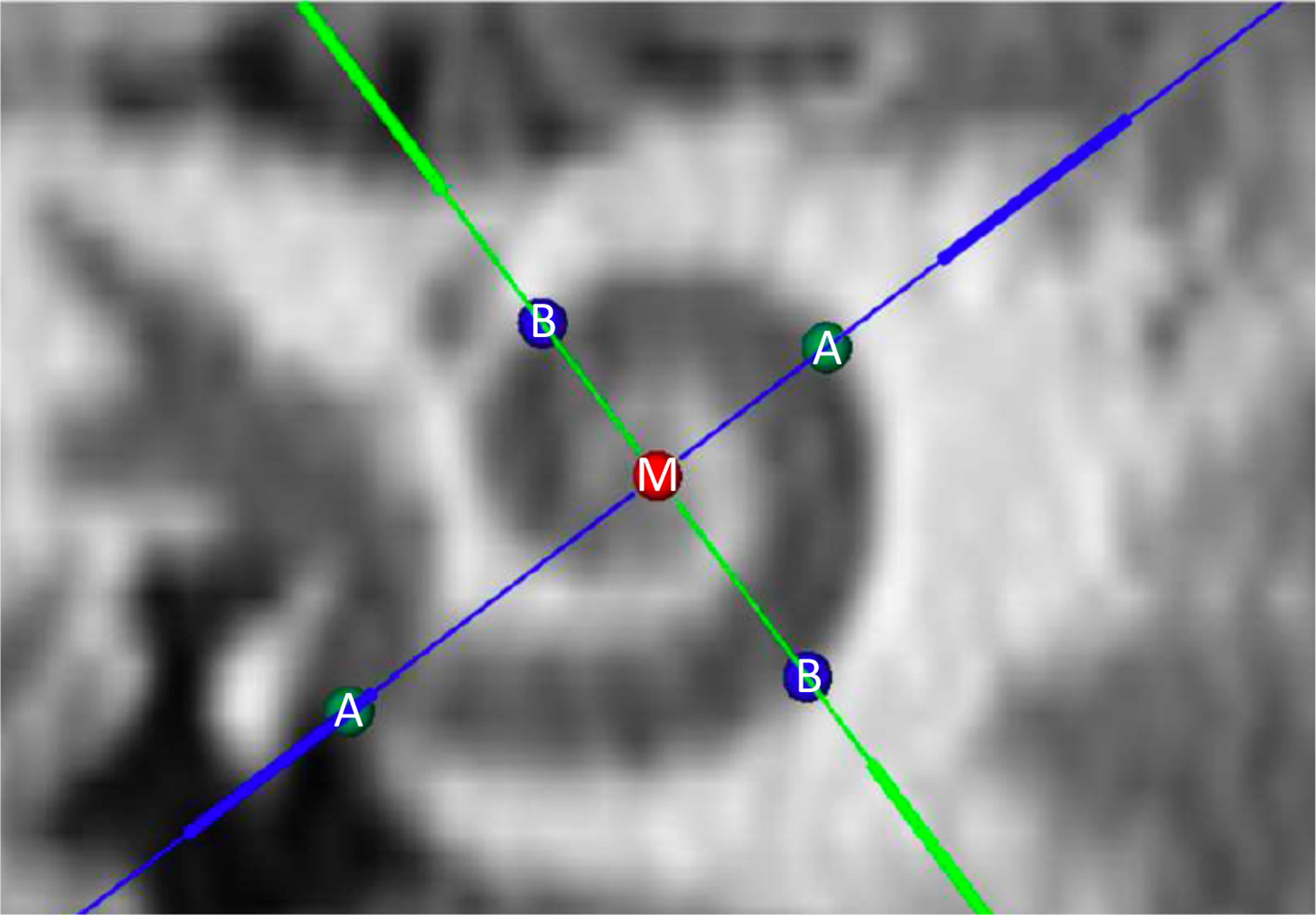

Where A = diameter of the cochlear base (in mm), defined as the linear distance between the center of the round window and opposite lateral wall through the central axis of the modiolus, and B = width of the cochlear base (in mm), defined as the linear distance between opposing lateral walls perpendicular to the A-value and through the central axis of the modiolus. In determining BTL at the organ of Corti (in mm), 1 mm is subtracted from A- and B-values to account for a 0.5 mm offset of the organ of Corti from the lateral wall on each side (0.5 mm × 2). Figure 1 shows the A-value (distance between green circles labeled A), B-value (distance between blue circles labeled B), and modiolus (red circle labeled M) depicted in cochlear view using OTOPLAN. The use of Equations 1 and 2 allows for the calculation of CDL at the organ of Corti (in mm).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography image depicting cochlear view in OTOPLAN, with identification of the mid-modiolar axis (red circle labeled M), cochlear diameter (distance between green circles labeled A), and cochlear width (distance between blue circles labeled B).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to assess demographic and anatomical variables associated with cases of partial insertion. These were performed with SPSS version 25 for Windows (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York).

RESULTS

Subject Demographics

Table 1 lists the demographic information for the 51 CI recipients implanted with a 31.5 mm flexible lateral wall array, separated into complete and partial insertion cohorts. For the complete insertion cohort, 59% of the subjects were male. The age at implantation ranged from 23 to 87 years, with a median of 61.2 years. The median preoperative low-frequency pure-tone average (LFPTA, unaided detection thresholds at 125, 250, and 500 Hz) was 73.3 dB HL (range: 30–105 dB HL). Demographics for subjects with a partial insertion are shown for comparison.

Table 1.

Subject demographics.

| Complete Insertions | Partial Insertions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n = 49 | Case 1 | Case 2 | |

| Sex, number (%) | ||||

| Female | 20 (40.8) | - | - | |

| Male | 29 (59.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| Age, years | 62.2 (23–87) | 68 | 58 | |

| Preoperative LFPTAa, dB HL | 73.3 (30–105) | 67 | 85 | |

| Cochlear morphology | ||||

| A-value, mm | 9.3 (8.4–10.2) | 9.1 | 9.2 | |

| B-value, mm | 6.8 (6.0–7.8) | 6.4 | 6.5 | |

| CDLb, mm | 33.6 (30.3–37.9) | 31.8 | 32.3 | |

| Angular Insertion Depth (degrees) | 641 (533–751) | 542 | 575 | |

LFPTA = low-frequency pure-tone average at 125, 250, and 500 Hz

CDL = cochlear duct length

Values are presented as median (range) unless otherwise indicated

Partial Insertion Rate, Angular Insertion Depth, and Cochlear Duct Length

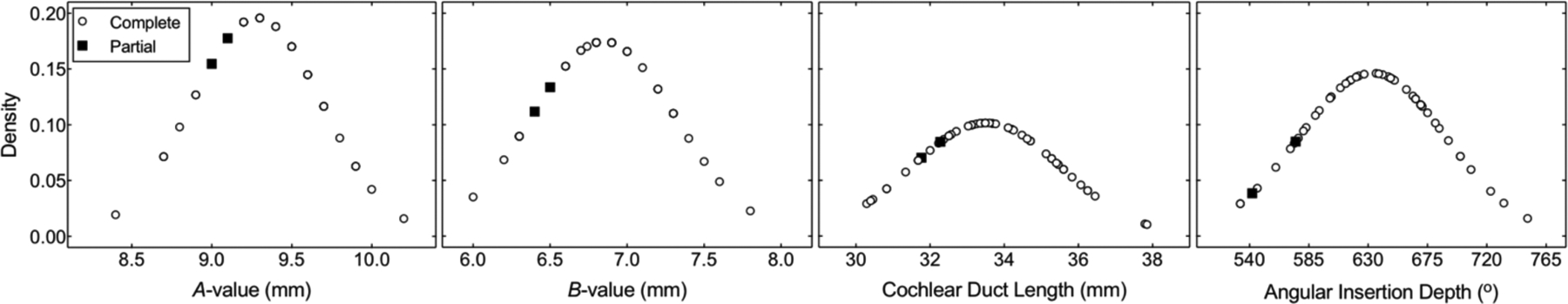

On review of postoperative CT, all 12 electrode contacts were noted to be intracochlear in the majority of cases (96.1%, n=49). The summary statistics characterizing cochlear morphology and electrode position for all subjects with a complete insertion and 2 with a partial insertion are shown in Table 1. Within the complete insertion cohort, the median CDL was 33.6 mm (range: 30.3–37.9 mm), and median AID was 641° (range: 533–751°). Figure 2 demonstrates the normal probability density functions for each of these values for complete (open circles) and partial insertions (black squares). The two cases of partial insertion (each with 1 extracochlear electrode contact) had relatively short CDL (31.8 mm [17th percentile] and 32.3 mm [23rd percentile]) and shallow AID (542° [6th percentile] and 575° [15th percentile]). The insertion depth for subjects with similar CDL that underwent a complete insertion extended beyond ~650°. Relatively shallow AID for the two cases of partial insertion fail to support the idea that CDL alone prevents a complete insertion.

Figure 2.

Normal probability density functions for measurements of the cochlear diameter (A-value), cochlear width (B-value), cochlear duct length, and angular insertion depth for FlexSOFT recipients with complete (n=49, open circles) or partial (n=2, black squares) insertions.

DISCUSSION

Previous investigations have reported variable incidence of partial insertion with long arrays, which may negatively influence speech recognition outcomes due to a reduction in the number of effective intracochlear channels37–40. Understanding morphological features associated with partial insertions may help to identify CI candidates who would benefit from complete insertion of a shorter array. The aims of the present study were to describe the rate of complete insertion among patients implanted with a 31.5 mm flexible lateral wall array and to identify morphological features associated with cases of partial insertion. In contrast to prior studies32,41, our results suggest that a complete insertion of a 31.5 mm flexible lateral wall array is feasible in the majority (96%) of cases and does not appear to be limited by CDL.

The present findings offer interesting insight as CDL at the organ of Corti, measured with histology or in-vivo CT, has been shown to vary from 24 to 40.1 mm (see Koch et al.30). Considering this broad range, partial insertion rates of a 31.5 mm array would be expected to be higher than observed herein. While the range of CDL values in the present study coincide with several previous reports42–46, we did not observe cases with a CDL <30 mm as described in others26,47,48. Nonetheless, as preoperative estimation of CDL was not considered in the array selection process at the time of the study, these data should be reflective of the general adult CI population with otherwise normal temporal bone anatomy. Furthermore, the range of CDL in the present sample was similar to those reported in a larger cohort using the ECA method22. It should be noted that all insertions herein were performed through the round window, which maximizes the accessible CDL to accommodate a given electrode array. Relative to a round window insertion, cochleostomy approaches reduce the available CDL given that the insertion begins distal to the round window membrane.

With limited literature specifically focusing on factors related to a partial insertion of long lateral wall arrays, it is difficult to make direct comparisons to prior work. In a cadaveric study, Adunka and Keifer49 demonstrated that the insertion force for FlexSOFT arrays doubled between insertion depths of 24 and 27 mm, although less force was required for the FlexSOFT than for the prior generation Standard array. Similarly, other cadaveric studies have shown partial insertion rates as high as 57% for 31.5 mm arrays50, as compared to 4% described herein. In our anecdotal experience, complete insertion of MED-EL lateral wall electrode arrays in cadaveric specimens are very difficult to achieve irrespective of array length. The authors urge caution in translating these cadaveric findings into clinical practice as increased frictional forces related to postmortem changes in temporal bone specimens in combination with a highly flexible electrode array likely confound the data49.

In the clinical setting, a broad range of partial insertion rates have been reported with long lateral wall arrays. For example, Johnston et al.41 noted that 25% of patients implanted with a FlexSOFT array had at least one basal electrode contact deactivated, although postoperative CT was not available in that study. Similarly, De Seta et al.32 reported a 32% partial insertion rate with the Standard array on review of postoperative CT. In contrast, others have suggested that a full insertion can be achieved in up to 95% of cases with these arrays, with the caveat that slightly lower rates of complete insertion are observed among surgeons with relatively less experience using a long lateral wall array51. This discrepancy in complete insertion rates may not only be related to cochlear morphology, but also a learning curve associated with insertion mechanics of a long, flexible array. Anecdotally, insertion may require additional finesse to avoid array bend, and if bend does occur, the array should be straightened by either 1) moving the dominant hand to change the overall angle of insertion or 2) using an instrument in the non-dominant hand to support the array at the site of the bend. Notwithstanding, the current results are consistent with the aforementioned high rate of complete insertion51, and further show that CDL alone cannot fully predict a partial insertion of 31.5 mm arrays. However, given that CDL in the two partial insertion cases was below the 25th percentile across all cases, preoperative measurement may help identify patients at increased risk for a partial insertion, who could benefit from an increased number of intracochlear electrode contacts and sufficient cochlear coverage with a shorter array.

The precise definition of sufficient cochlear coverage continues to be elusive, and the relationship between AID and speech recognition with a CI-alone device remains an active area of investigation. Though prior work has demonstrated better performance for recipients of 31.5 mm arrays when compared to those implanted with a 24 mm array8, it is likely that a tradeoff exists between the benefits of a deeper insertion achieved with a long array (e.g., reduced frequency-to-place mismatch and greater separation between neighboring electrode contacts22) and the potential for deleterious effects related to apical trauma49 or reduced spatial selectivity in the apex52–54. For this reason, linear modeling used in prior studies to assess the relationship between AID and speech recognition may be inappropriate, as performance could improve and then either plateau or even decline with increasing insertion depth. For example, in the present cohort, several subjects with a relatively short CDL have electrode insertions that extend beyond the length of the spiral ganglion (approximately 630–720°42,55,56). Given these considerations, though a complete insertion of a 31.5 mm array is feasible in the majority of cases, it is possible that speech recognition benefit is reduced beyond a given insertion depth, and in future studies it will be important to assess whether implantation with a shorter (e.g., 28 mm) array would be more advantageous for patients with a short CDL.

There are several limitations of the current study that deserve mention. First, the CT was obtained at the initial postoperative visit (approximately 2–4 weeks postoperatively). Anecdotally, one subject (AID=693° and CDL=30.4 mm) presented at the 3-month interval with high impedance on the basal channels and underwent repeat imaging. The CT demonstrated approximately 2 mm of array migration with the most basal electrode contact residing just outside the round window. Further studies are needed to characterize the incidence of array migration over time. Given the retrospective design, we were unable to assess the amount of resistance being met during insertion. At our institution, though a complete insertion is the goal in all cases, partial insertion is preferable in cases where resistance is encountered, particularly in patients with residual acoustic hearing. Given that the LFPTA of the partial insertion cases was similar to the median for those with complete insertions (Table 1), it is unlikely that these two cases were partially inserted with the sole intention of hearing preservation. Another consideration is that although a complete insertion with a flexible 31.5 mm array is feasible in the majority of cases, the risk of apical trauma remains incompletely understood. As recent efforts have shown feasibility of hearing preservation with 31.5 mm arrays57–59, intracochlear trauma may be less than previously thought when using soft surgical techniques. Nonetheless, future histological studies are needed to assess this variable. As the current study was also not designed to specify a cutoff CDL value to use in the electrode array selection process, it should be noted that equations used to provide CDL estimates with clinical CT are continually evolving35,36,60; the values reported herein are representative of the ECA method35. Lastly, though partial insertions were not predicted by CDL alone, the two cases of partial insertion had small A- and B-values and short CDLs compared to the rest of the cohort. Other features of cochlear morphology, such as the dimensions of the scala tympani, might help explain the inability to achieve a complete insertion in these cases.

CONCLUSIONS

Complete insertion of a 31.5 mm flexible array is feasible in most (96%) adult CI recipients without evidence of cochlear malformation and does not appear to be limited by CDL. Future studies are needed to estimate other variations in cochlear morphology, that are feasibly obtained with current in-vivo imaging, which could predict resistance and failure to achieve a complete insertion of a long array.

Funding source:

This work was funded in part by the NIH through NIDCD (T32 DC005360).

Conflicts of interest:

Margaret T. Dillon is supported by a research grant from MED-EL Corporation provided to the university. Kevin D. Brown is on the surgical advisory board for MED-EL Corporation. Harold C. Pillsbury is a consultant for MED-EL Corporation. Brendan P. O’Connell is on the surgical advisory board for MED-EL Corporation and a consultant for Advanced Bionics

Footnotes

This article was presented as a scientific oral presentation at the 2020 AAO-HNSF Virtual Annual Meeting & OTO Experience; September 13–15, 2020.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blamey P, Arndt P, Bergeron F, et al. Factors affecting auditory performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants. Audiol Neurootol. 1996;1(5):293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blamey P, Artieres F, Baskent D, et al. Factors affecting auditory performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: an update with 2251 patients. Audiol Neurootol. 2013;18(1):36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gantz BJ, Woodworth GG, Knutson JF, Abbas PJ, Tyler RS. Multivariate predictors of audiological success with multichannel cochlear implants. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102(12):909–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazard DS, Vincent C, Venail F, et al. Pre-, per- and postoperative factors affecting performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: a new conceptual model over time. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green KM, Bhatt Y, Mawman DJ, et al. Predictors of audiological outcome following cochlear implantation in adults. Cochlear Implants Int. 2007;8(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connell BP, Cakir A, Hunter JB, et al. Electrode Location and Angular Insertion Depth Are Predictors of Audiologic Outcomes in Cochlear Implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(8):1016–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connell BP, Hunter JB, Haynes DS, et al. Insertion depth impacts speech perception and hearing preservation for lateral wall electrodes. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(10):2352–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchman CA, Dillon MT, King ER, Adunka MC, Adunka OF, Pillsbury HC. Influence of cochlear implant insertion depth on performance: a prospective randomized trial. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35(10):1773–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakravorti S, Noble JH, Gifford RH, et al. Further Evidence of the Relationship Between Cochlear Implant Electrode Positioning and Hearing Outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochmair I, Arnold W, Nopp P, Jolly C, Muller J, Roland P. Deep electrode insertion in cochlear implants: apical morphology, electrodes and speech perception results. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123(5):612–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchner A, Illg A, Majdani O, Lenarz T. Investigation of the effect of cochlear implant electrode length on speech comprehension in quiet and noise compared with the results with users of electro-acoustic-stimulation, a retrospective analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0174900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yukawa K, Cohen L, Blamey P, Pyman B, Tungvachirakul V, O’Leary S. Effects of insertion depth of cochlear implant electrodes upon speech perception. Audiol Neurootol. 2004;9(3):163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finley CC, Holden TA, Holden LK, et al. Role of electrode placement as a contributor to variability in cochlear implant outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 2008;29(7):920–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holden LK, Finley CC, Firszt JB, et al. Factors affecting open-set word recognition in adults with cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2013;34(3):342–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gani M, Valentini G, Sigrist A, Kos MI, Boex C. Implications of deep electrode insertion on cochlear implant fitting. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2007;8(1):69–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canfarotta MW, O’Connell BP, Giardina CK, et al. Relationship Between Electrocochleography, Angular Insertion Depth, and Cochlear Implant Speech Perception Outcomes. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorman MF, Loizou PC, Rainey D. Simulating the effect of cochlear-implant electrode insertion depth on speech understanding. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;102(5 Pt 1):2993–2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu QJ, Shannon RV. Effects of electrode location and spacing on phoneme recognition with the Nucleus-22 cochlear implant. Ear Hear. 1999;20(4):321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li T, Fu QJ. Effects of spectral shifting on speech perception in noise. Hear Res. 2010;270(1–2):81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baskent D, Shannon RV. Speech recognition under conditions of frequency-place compression and expansion. J Acoust Soc Am. 2003;113(4 Pt 1):2064–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baskent D, Shannon RV. Interactions between cochlear implant electrode insertion depth and frequency-place mapping. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;117(3 Pt 1):1405–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canfarotta MW, Dillon MT, Buss E, Pillsbury HC, Brown KD, O’Connell BP. Frequency-to-Place Mismatch: Characterizing Variability and the Influence on Speech Perception Outcomes in Cochlear Implant Recipients. Ear Hear. 2020; 41(5):1349–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canfarotta MW, O’Connell BP, Buss E, Pillsbury HC, Brown KD, Dillon MT. Influence of Age at Cochlear Implantation and Frequency-to-Place Mismatch on Early Speech Recognition in Adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020:194599820911707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Dawant BM, Labadie RF, Noble JH. Retrospective Evaluation of a Technique for Patient-Customized Placement of Precurved Cochlear Implant Electrode Arrays. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157(1):107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canfarotta MW, Dillon MT, Buchman CA, et al. Long-Term Influence of ElectrodeArray Length on Speech Recognition in Cochlear Implant Users. Laryngoscope. 2020; doi: 10.1002/lary.28949. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardy M The length of the organ of corti in man. Am J Anat. 1938;63:291–311. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wurfel W, Lanfermann H, Lenarz T, Majdani O. Cochlear length determination using Cone Beam Computed Tomography in a clinical setting. Hear Res. 2014;316:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng J, Li S, Zhang F, Li Q, Qin Z. Cochlear Size and Shape Variability and Implications in Cochlear Implantation Surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(9):1307–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Avci E, Nauwelaers T, Lenarz T, Hamacher V, Kral A. Variations in microanatomy of the human cochlea. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522(14):3245–3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch RW, Ladak HM, Elfarnawany M, Agrawal SK. Measuring Cochlear Duct Length - a historical analysis of methods and results. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;46(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timm ME, Majdani O, Weller T, et al. Patient specific selection of lateral wall cochlear implant electrodes based on anatomical indication ranges. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0206435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Seta D, Nguyen Y, Bonnard D, et al. The Role of Electrode Placement in Bilateral Simultaneously Cochlear-Implanted Adult Patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155(3):485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Canfarotta MW, Dillon MT, Buss E, Pillsbury HC, Brown KD, O’Connell BP. Validating a New Tablet-Based Tool in the Determination of Cochlear Implant Angular Insertion Depth. Otol Neurotol. 2019;40(8):1006–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verbist BM, Skinner MW, Cohen LT, et al. Consensus panel on a cochlear coordinate system applicable in histologic, physiologic, and radiologic studies of the human cochlea. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31(5):722–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schurzig D, Timm ME, Batsoulis C, et al. A Novel Method for Clincial Cochlear Duct Length Estimation toward Patient-Specific Cochlear Implant Selection. OTO Open. 2018:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexiades G, Dhanasingh A, Jolly C. Method to estimate the complete and two-turn cochlear duct length. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36(5):904–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fishman KE, Shannon RV, Slattery WH. Speech recognition as a function of the number of electrodes used in the SPEAK cochlear implant speech processor. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1997;40(5):1201–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friesen LM, Shannon RV, Baskent D, Wang X. Speech recognition in noise as a function of the number of spectral channels: comparison of acoustic hearing and cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Am. 2001;110(2):1150–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shannon RV, Cruz RJ, Galvin JJ 3rd. Effect of stimulation rate on cochlear implant users’ phoneme, word and sentence recognition in quiet and in noise. Audiol Neurootol. 2011;16(2):113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berg KA, Noble JH, Dawant BM, Dwyer RT, Labadie RF, Gifford RH. Speech recognition with cochlear implants as a function of the number of channels: Effects of electrode placement. J Acoust Soc Am. 2020;147(5):3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnston JD, Scoffings D, Chung M, et al. Computed Tomography Estimation of Cochlear Duct Length Can Predict Full Insertion in Cochlear Implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(3):223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stakhovskaya O, Sridhar D, Bonham BH, Leake PA. Frequency map for the human cochlear spiral ganglion: implications for cochlear implants. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2007;8(2):220–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ketten DR, Skinner MW, Wang G, Vannier MW, Gates GA, Neely JG. In vivo measures of cochlear length and insertion depth of nucleus cochlear implant electrode arrays. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1998;175:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skinner MW, Ketten DR, Holden LK, et al. CT-derived estimation of cochlear morphology and electrode array position in relation to word recognition in Nucleus-22 recipients. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2002;3(3):332–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bredberg G Cellular pattern and nerve supply of the human organ of Corti. Acta Otolaryngol. 1968:Suppl 236:231+. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato H, Sando I, Takahashi H. Sexual dimorphism and development of the human cochlea. Computer 3-D measurement. Acta Otolaryngol. 1991;111(6):1037–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pollak A, Felix H, Schrott A. Methodological aspects of quantitative study of spiral ganglion cells. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1987;436:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee J, Nadol JB Jr., Eddington DK. Depth of electrode insertion and postoperative performance in humans with cochlear implants: a histopathologic study. Audiol Neurootol. 2010;15(5):323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adunka O, Kiefer J. Impact of electrode insertion depth on intracochlear trauma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(3):374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radeloff A, Mack M, Baghi M, Gstoettner WK, Adunka OF. Variance of angular insertion depths in free-fitting and perimodiolar cochlear implant electrodes. Otol Neurotol. 2008;29(2):131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyd PJ. Potential benefits from deeply inserted cochlear implant electrodes. Ear Hear. 2011;32(4):411–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Landsberger DM, Mertens G, Punte AK, Van De Heyning P. Perceptual changes in place of stimulation with long cochlear implant electrode arrays. J Acoust Soc Am. 2014;135(2):EL75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kalkman RK, Briaire JJ, Dekker DM, Frijns JH. Place pitch versus electrode location in a realistic computational model of the implanted human cochlea. Hear Res. 2014;315:10–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arnoldner C, Riss D, Baumgartner WD, Kaider A, Hamzavi JS. Cochlear implant channel separation and its influence on speech perception--implications for a new electrode design. Audiol Neurootol. 2007;12(5):313–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li H, Schart-Moren N, Rohani SA, Ladak HM, Rask-Andersen H, Agrawal S. Synchrotron Radiation-Based Reconstruction of the Human Spiral Ganglion: Implications for Cochlear Implantation. Ear Hear. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dhanasingh AE, Rajan G, van de Heyning P. Presence of the spiral ganglion cell bodies beyond the basal turn of the human cochlea. Cochlear Implants Int. 2020;21(3):145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Helbig S, Van de Heyning P, Kiefer J, et al. Combined electric acoustic stimulation with the PULSARCI(100) implant system using the FLEX(EAS) electrode array. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131(6):585–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mick P, Amoodi H, Shipp D, et al. Hearing preservation with full insertion of the FLEXsoft electrode. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35(1):e40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hollis ES, Canfarotta MW, Dillon MT, et al. Initial Hearing Preservation is Correlated with Cochlear Duct Length in Fully-Inserted long Flexible Lateral Wall Arrays. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Escude B, James C, Deguine O, Cochard N, Eter E, Fraysse B. The size of the cochlea and predictions of insertion depth angles for cochlear implant electrodes. Audiol Neurootol. 2006;11 Suppl 1:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]