Abstract

Background

The disability weight is an essential factor to estimate the healthy time that is lost due to living with a certain state of illness. A 2014 review showed a considerable variation in methods used to derive disability weights. Since then, several sets of disability weights have been developed. This systematic review aimed to provide an updated and comparative overview of the methodological design choices and surveying techniques that have been used in disability weights measurement studies and how they evolved over time.

Methods

A literature search was conducted in multiple international databases (early-1990 to mid-2021). Records were screened according to pre-defined eligibility criteria. The quality of the included disability weights measurement studies was assessed using the Checklist for Reporting Valuation Studies (CREATE) instrument. Studies were collated by characteristics and methodological design approaches. Data extraction was performed by one reviewer and discussed with a second.

Results

Forty-six unique disability weights measurement studies met our eligibility criteria. More than half (n = 27; 59%) of the identified studies assessed disability weights for multiple ill-health outcomes. Thirty studies (65%) described the health states using disease-specific descriptions or a combination of a disease-specific descriptions and generic-preference instruments. The percentage of studies obtaining health preferences from a population-based panel increased from 14% (2004–2011) to 32% (2012–2021). None of the disability weight studies published in the past 10 years used the annual profile approach. Most studies performed panel-meetings to obtain disability weights data.

Conclusions

Our review reveals that a methodological uniformity between national and GBD disability weights studies increased, especially from 2010 onwards. Over years, more studies used disease-specific health state descriptions in line with those of the GBD study, panel from general populations, and data from web-based surveys and/or household surveys. There is, however, a wide variation in valuation techniques that were used to derive disability weights at national-level and that persisted over time.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13690-022-00860-z.

Keywords: Burden of disease, Disability weight, Disability adjusted life years, Valuation of health states

Background

The Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY) is a population health metric that measures the burden of disease of a population by integrating mortality in Years of Life Lost (YLL) and morbidity in Years Lived with Disability (YLD) [1–3]. It was first used in the early 1990s, in the first iteration of the Global Burden of Disease and Injury (GBD) study; a landmark global effort to estimate fatal and non-fatal health outcomes using a health metric that allows comparisons of the impact of different diseases, injuries, and risk factors over time and between geographies [4–6]. Thus, the DALY-concept provides a comprehensive health overview and is a crucial tool in facilitating decision-making on disease prevention.

The disability weight is an essential factor to assess DALYs, and in particular to estimate the healthy time that is lost due to living with a certain state of illness [7]. A disability weight is a weighting factor that reflects the relative severity of a health state, with a value anchored from 0 to 1, with 0 implying a state that is equivalent to full health and 1, a state equivalent to death. The first set of disability weights was established for the GBD 1996 study [8]. Since then, multiple alternative sets of disability weights have been developed, each using different design choices [9]. A set of disability weights refers to a collection of disability weights that resulted from one specific disability weight study.

The disability weight is a so-called social value; it is based on preferences of a certain population [7, 10]. This population can consist of, for instance, persons of the general population or a group of health professionals [7]. The characteristics of the persons who provide the preferences have implications for the description of the health state and for the difficulty of the health state valuation tasks that are used to elicit the preferences for health states. These health state valuation tasks can consist of a relatively simple task of choosing the healthier person out of two, or much more complicated tasks that require the respondent to make a trade-off between two hypothetical scenarios of health programs that emulate health policy decisions [7, 11]. Notably, the GBD 1996 set of disability weights [8] was based on the health state valuations of a group of 10 health professionals that evaluated disease labels for 483 sequelae resulting from 131 diseases and injuries (e.g., “dislocation of shoulder: long term, with or without treatment”) without a further description of symptoms or physical impairments, whereas the GBD 2010 set of disability weights [12] was based on the health state valuations of more than 30,000 persons from the general population evaluating short disease descriptions for 220 unique health states without a disease label (e.g., “has a shoulder that is out of joint, causing pain and difficulty moving. The person has difficulty with daily activities such as dressing and cooking”).

In 2014, an overview of disability weight studies and their design choices was published [9]. However, since then several other disability weights measurement studies have been performed, either because a national burden of disease study was performed, with the researchers preferring to use disability weights that are based on the preferences of the national population [13–16] or because disability weights for certain diseases were unavailable [17–19]. Another reason may be that existing disability weights were too granular, meaning that the disability weights represent health states that are heterogeneous with respect to the severity level of functional limitations [12, 20], and may therefore hamper the mapping of disability weights to available epidemiological data.

Therefore, this systematic literature review aimed to provide an updated and comparative overview of the methodological design choices that have been used in disability weights measurement studies. The following research questions were addressed:

How many disability weights measurement studies have been conducted, and in which countries?

Which methodological design choices have been used to describe and value health states in disability weights measurement studies and how did these evolve over time?

Methods

Methodological design choices in disability weight studies

There are five methodological aspects of estimating disability weights for different states of health. The first design choice relies on the health state description. The health state can be described using a generic or a disease-specific method. A generic health state description indicates the functional health status regardless of the underlying health condition [21, 22]. Multi-attribute utility instruments can be used to generate generic health state descriptions. With multi-attribute utility instruments, generic attributes are used to classify health states; for each health state a functional level is chosen for each attribute. To classify health states, several generic instruments are available, such as the EQ-5D [23] or SF-36 [24] health questionnaires, or a combination of these attributes namely Classification and Measurement System of Functional Health (CLAMES model) [25]. Using weights for the separate attributes, the reported functional level on the attributes is then converted into a disability weight which by definition fits within the 0–1 range. A disease-specific health state description indicates the cause and/or the functional consequences and symptoms associated with the condition [21]. A health state description that combines generic and disease-specific health state is also used [26].

The second design choice involves the panel of judges. In essence, the values of disability weights are usually assigned based on the preferences of medical experts [11], health professionals [11], patients or people with disabilities [11], representative population samples [11], or a combination of these groups [11, 27].

The third design choice relates to the valuation methods for health states. Several measurements exist, of which the visual analogue scale (VAS), interpolation, time trade-off (TTO), person trade-off (PTO), standard gamble (SG), paired comparison (PC), and population health equivalence (PHE) have been widely applied to measure individual preferences [11, 22]. The VAS valuation method requires participants to score a health state of disease on a vertical, calibrated line graded from 0 (“worst imaginable health state”) to 100 (“best imaginable health state”). The interpolation technique requires the panel members to value health states by placing each health state of disease as similar to or in-between indicator health states on the calibrated disability scale [26, 28]. The TTO method elicits preferences for states of health by asking participants to choose between a certain amount of time in the presented health state or a shorter life spent in full health. The PTO method asks respondents to trade-off numbers of person-years living in good health and person-years lived in a lesser state of health. The SG method asks respondents to make choices that weigh health improvements against risk of death. With the PC technique, two alternative health states are presented and the respondents have to decide which is more desirable. The PHE technique requires participants to compare health benefits of different health programmes. Each of these tools has advantages and disadvantages. Information about the advantages and disadvantages of these valuation techniques have been described elsewhere [11, 29].

The fourth design choice relates to the time presentation. Disability weights of the health states can be subdivided into annual health profile and/or period profile disability weights. The annual profile approach describes the course of the health state over a 1-year period, whereas the period profile approach assumes that the duration of the health state remains constant over time [7, 30]. However, the annual profile approach has been previously suggested to assess disability weights for conditions with acute onset or conditions characterized by short-term duration or heterogenous recovery patterns [7, 26].

The fifth design choice relates to the surveying techniques. Disability weight data can be collected by focus panel-group discussions or panel meetings, telephone or face-to-face interviews, or web-based or mail/postal surveys using, for example, questionnaire as an instrument.

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [31], in May 2021 we systematically searched electronic databases and search engines namely PubMed (Medline Ovid), Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane, PsycINFO. We also searched for eligible grey literature via other sources (i.e., Google Scholar). Search strings can be found in the Additional file. We registered this systematic literature review protocol on PROSPERO database under ID CRD42021259156.

The inclusion criteria were disability weights measurement studies that derived disability weights for single or multiple health outcomes, published in peer-reviewed journals or grey literature between January 1990 and May 2021. We considered studies assessing disability weights for burden of disease measurements, expressed in DALY estimates. This review included studies that assessed disability weights for multiple health states, since disability weights for one single state of health cannot capture population’s preferences for health states. There were no geographical and language restrictions. We used a translation software for papers in languages we could not read. We excluded studies deriving quality-adjusted life year weights and those deriving disability weights for comparative risk factor assessments (e.g., noise-induced sleep disturbance) as they were beyond the scope of this review.

Screening and data extraction

After removing duplicates, we selected relevant disability weights measurement studies following three steps. First, we excluded studies on the basis of the title; second, we screened the abstracts of the studies selected in the first step; and third, we read the entire full-texts selected in the second step. During each step, we evaluated the titles, abstracts, or full-texts respectively, using the eligibility criteria described above.

One researcher (PC) performed the screening of data using the EndNote X9 software. PC also handsearched the reference lists of systematic reviews and studies or reports included in this review, in order to detect additional eligible disability weights measurement studies. PC then listed the articles obtained from the databases, search engines, other sources, and reference checks in an Excel spreadsheet, comparing accordingly for eligibility. Two researchers (PC and JH) critically appraised eligible disability weights measurement studies, using the data extraction grid developed for the systematic review by Haagsma et al. [9]. We extracted data relating to the following items: study characteristics and geographical location(s), cause(s) of ill-health outcomes, design choices (i.e. health state description, panel of judges, valuation methods for health states, time presentation, and surveying techniques). PC and JH discussed any disagreements arising from eligibility criteria or data extraction items.

Data synthesis

Those disability weights measurement studies that we considered for review have been quantitively classified:

as single-country or multi-country studies based on the geographical location(s) covered;

as single-cause or multi-cause studies based on the cause(s) of ill-health outcomes for which the disability weights were derived;

by the methodological design choices that have been used to assess disability weights.

Finally, we plotted the key methodological design choices identified in these studies over period.

Methodological quality

One researcher (PC) performed the methodological quality of each disability weights measurement study, using a modified version of the Checklist for Reporting Valuation Studies (CREATE) instrument [32]. The quality assessment form can be found in the Additional file. The CREATE checklist aims to promote good reporting practices of methodological design choices in valuation studies. This checklist consists of 21 items grouped in seven domains. For this systematic review, items 1–15 were applicable to all the included studies. However, for the purpose of this review, we modified the items 1, 2, 3, and 15; we also excluded items 16–21, as scoring algorithm and modelling specifications are outside the scope of this review.

Results

Literature search

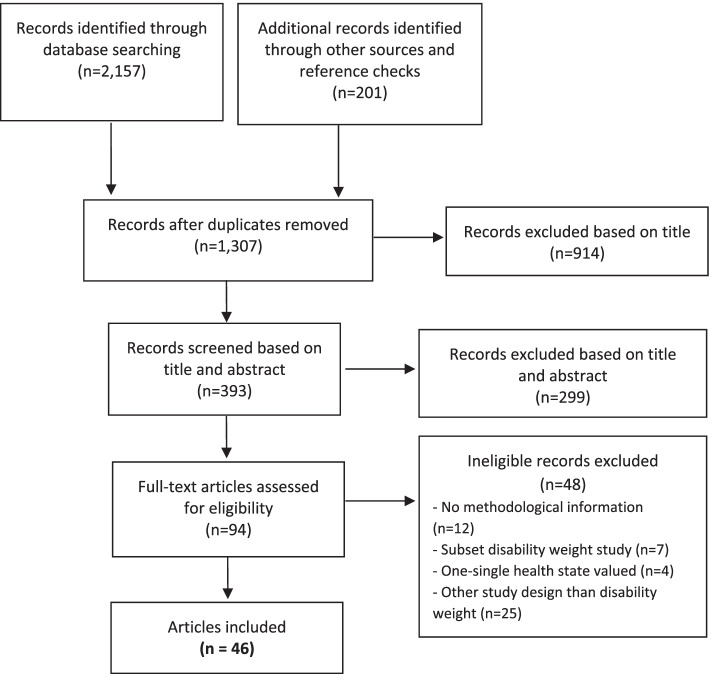

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the search for existing disability weights measurement studies and the main reasons for exclusion. Searches through the electronic databases, search engines, handsearching and the grey literature provided a total of 1307 records. The full-texts of 94 articles were systematically read, and led to the final review of 46 unique disability weights measurement studies.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of existing disability weights measurement studies

Study characteristics

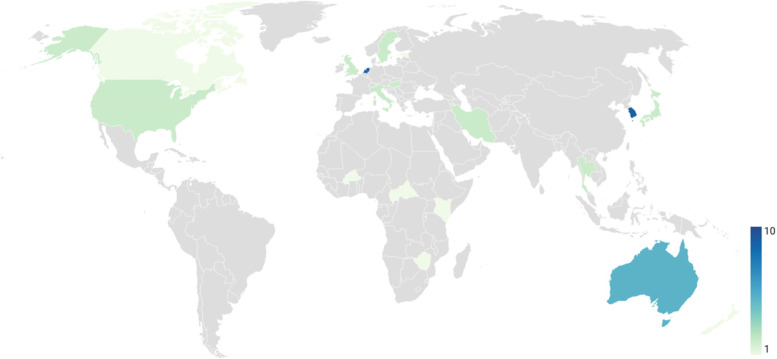

Of the 46 studies included in our systematic literature review, most (n = 35; 76%) estimated disability weights at a single-country level, while the remaining 24% (n = 11) estimated multi-country disability weights. The single-country disability weights studies were performed across 12 countries. The number of published single-country disability weight studies varied by country, with the lowest number in Estonia (n = 1) and Zimbabwe (n = 1), and the highest number in South Korea (n = 10) and the Netherlands (n = 7), (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Number of disability weights measurement studies per country

A map illustrating the number of studies that estimated disability weights for multiple heath states of disease. Countries in grey indicate that no studies met our eligibility criteria or they have not yet estimated disability weights.

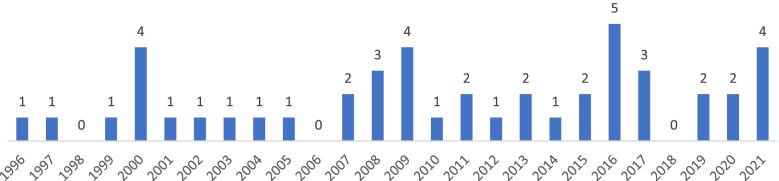

As can be seen in Fig. 3, almost every year within the early-1996 to mid-2021 period, one or more than one disability weights measurement studies were published. The earliest study was published in 1996, but none in 1998, 2006, and 2018. The highest number of disability weights measurement studies was seen in 2016 (n = 5).

Fig. 3.

Number of disability weights measurement studies published between 1996 and 2021

More than half of the identified disability weight measurement studies (n = 27; 59%) assessed disability weights for a variety of cause of ill-health outcomes. The remaining nineteen studies (n = 19; 41%) concerned disability weights for specific causes or sequelae of diseases (i.e. injuries [33–36], poisonings [37], urological disease [38], periodontal disease [39], oral disease [40], infectious diseases [41], alcohol use disorders [42], mental disorders [43], stroke [44], cardiovascular disease (CVD [45];), multiple sclerosis [46], neoplasms [47, 48], leprosy [17], paediatric congenital anomalies [18], or osteoporosis [49]).

Methodological quality

Table 1 reports detailed information of the characteristics, methodological and experimental design choices, and methodological quality for each of the 46 disability weights measurement studies. The quality of the included disability weight papers according to the CREATE criteria [32] was very good, with a mean score of 93%. Overall, the major item that did not comply with the CREATE checklist was about stating response rate (66%). All disability weights measurement studies reported on the health state descriptions and valuation techniques, panel of judges, time presentation, study sample, and transformation-modeling analyses.

Table 1.

Study characteristics, methodological design choices, surveying techniques, and quality of the included disability weights measurement studies

| Author | Year | Region or country included | Single- or Multi-cause study? | Panel of judges | Number of the panel members | Number of health states valued | Description of health states | Time Presentation | Valuation methods for health states | Surveying technique/tool | Number of tasks per panel member | CREATE score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asadi et al. [37] | 2016 | Iran | Single (Poisonings) | ME | 10 | 50 | DS | Period Profile | Interpolation | Questionnaire | NA | 93 |

| Bae et al. [49] | 2019 | Korea | Single (Osteoporosis; osteoporotic fractures) | ME | 33 | 6 | NA | Period Profile | PTO | Face-to-face interview | 6 | 87 |

| Bakhshandeh et al. [45] | 2009 | Iran | Single (Cardiovascular diseases) | HP, PT, PX, PP | 80 | 25 | DS | NA | VAS (ranking) | Face-to-face interview | 25 | 80 |

| Baltussen et al. [50] | 2002 | Burkina Faso | Multiple | HP, PP | 56 | 9 | DS (scenario analyses) | Period Profile | Adapted VAS/ Interpolation | Group discussion & Questionnaire | 9 | 93 |

| Basiri et al. [38] | 2008 | Iran | Single (Urological disease) | ME | 10 | 76 | NA | Period Profile | Interpolation | Questionnaire | 10 | 87 |

| Brennan & Spencer [40] | 2004 | Australia | Single (Oral disease) | Model | NA | 18 | EQ-5D | Period Profile | EQ-5D: NA | NA | NA | 100 |

| Brennan et al. [39] | 2007 | Australia | Single (Peridontal disease) | Model | NA | 6 | EQ-5D | Period Profile | EQ-5D: NA | NA | NA | 100 |

| Cho et al. [46] | 2014 | Korea | Single (Multiple sclerosis) | ME | 15 | 5 | DS | Period Profile | PTO | Modified Delphi method | NA | 87 |

| Choi et al. [47] | 2013 | Korea | Single (Cancer) | ME | 32 | 24 | NA | Period Profile | VAS & PTO | NA | 24 | 87 |

| Gabbe et al. [33] | 2016 | Netherlands, United States, New Zealand, Australia, United Kingdom | Single (Injury) | Model | NA | 40 | EQ-5D | Period Profile | EQ-5D: NA | NA | NA | 100 |

| Haagsma et al. [34] | 2008 | Netherlands | Single (Injury) | PP | 143 | 44 | DS & EQ-5D | Annual profile | VAS & TTO | Panel meeting & Questionnaire | 32 | 100 |

| Haagsma et al. [51] | 2008 | Netherlands | Multiple | PP | 107 | 39 | DS & EQ-5D | Annual profile | VAS & PTO | Panel meeting & Questionnaire | 27 | 100 |

| Haagsma et al. [35] | 2009 | Netherlands | Single (Injury) | Model | NA | 7 | EQ-5D | Period Profile | EQ-5D: NA | NA | NA | 100 |

| Haagsma et al. [14] | 2015 | Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Sweden | Multiple | PP | 30,660 | 255 | DS | Period Profile | PC & PHE | Web-based survey | 18 | 100 |

| Hong & Saver [44] | 2009 | United States, Southeast Asia | Single (Stroke) | ME | 9 | 5 | NA | NA | PTO | Panel meeting & Questionnaire | 5 | 80 |

| Havelaar et al. [41] | 2000 | Netherlands | Single Infectious disease | ME | 35 | NA | NA | Period Profile | Interpolation | Panel meeting | NA | 93 |

| Jelsma et al. [52] | 2000 | Zimbabwe | Multiple | ME, PP | 68 | 22 | NA | Period Profile | VAS & PR | Focus group discussion | NA | 80 |

| Kim et al. [53] | 2020 | Korea | Multiple | ME | 806 | 313 | DS | Period Profile | PR | Web-based survey | 20 | 93 |

| Kruijshaar et al. [54] | 2005 | Netherlands | Multiple | ME | 49 | 18 | DS & EQ-5D | Period Profile | Interpolation | Questionnaire | 18 | 100 |

| Kwong et al. [55] | 2010 | Canada | Multiple | Model | NA | NA | CLAMES | Period Profile | CLAMES: NA | NA | NA | 100 |

| Lai et al. [56] | 2009 | Estonia | Multiple | ME | 25 | 283 | DS | Period Profile | VAS & PTO | Panel meeting | NA | 93 |

| Lyons et al. [36] | 2011 | United Kingdom | Single (Injury) | Model | NA | 13 | EQ-5D | Period Profile | EQ-5D: NA | NA | NA | 93 |

| Mathers et al. [57] | 2000 | Australia | Multiple | Model | NA | NA | EQ-6D & DDW | Period Profile | EQ-6D: NA | NA | NA | 100 |

| Murray et al. [8] | 1996 | Global | Multiple | ME | 10 | 483 | DS | Period Profile | VAS & PTO | NA | NA | 87 |

| Nanjan Chandran et al. [17] | 2021 | Global | Single (Lepropsy) | PP | 667 | 3 | SF-36 HRQoL data | NA | SF-36 HRQoL data: NA (meta-analysis) | NA | NA | 100 |

| Neethling et al. [16] | 2016 | South Africa | Multiple | PP | 677 | 51 | DS (no label) | Period Profile | PC & TTO | Household face-to-face interview | 15 | 100 |

| Nontarak et al. [58] | 2020 | Thailand | Multiple | PT | 450 | 9 | DS & EQ-5D | Period Profile | VAS & EQ-5D & TTO | Face-to-face interview | NA | 87 |

| Nontarak et al. [42] | 2021 | Thailand | Single (Alcohol use disorders) | PT, PP | 300 | 3 | DS & EQ-5D | Period Profile | VAS & EQ-5D & TTO | Face-to-face interview | NA | 93 |

| Nomura et al. [13] | 2021 | Japan | Multiple | PP | 37,318 | 231 | DS (no label) | Period Profile | PC & PHE | Web-based survey | 18 | 100 |

| Ock et al. [59] | 2016 | Korea | Multiple | HP | 496 | 228 | DS | Period Profile | PC & PTO | Web-based survey | 60 | 93 |

| Ock et al. [15] | 2016 | Korea | Multiple | PP | 5916 | 256 | DS | Period Profile | PC & VAS & SG & PHE | Household survey & Web-based survey | 22 | 93 |

| Ock et al. [60] | 2019 | Korea | Multiple | HP | 605 | 289 | DS (no label) | Period Profile | PR | Web-based survey | 20 | 93 |

| Park & Jung [61] | 2017 | Korea | Multiple | Model | NA | 243 | EQ-5D | NA | EQ-5D: NA | NA | 100 | |

| Piao et al. [62] | 2021 | Japan | Multiple | HP | 286 | 17 | DS | Period Profile | PC & PHE | Questionnaire | NA | 87 |

| Poenaru et al. [18] | 2017 | Kenya, Canada | Single (Paediatric conditions) | HP | 154 | 15 | DS & EQ-5D | NA | PR & VAS & PC & TTO | Focus groups | NA | 87 |

| Rehm & Frick [63] | 2013 | United States | Multiple | ME | 68 | 12 | DS + CLAMES | NA | PC & PR & PTO | NA | NA | 87 |

| Salomon et al. [12] | 2012 | Global | Multiple | PP | 30,230 | 220 | DS (no label) | Period Profile | PC & PHE | Household survey; Web-based survey | 18 | 100 |

| Salomon et al. [20] | 2015 | Global | Multiple | PP | 30,230 & 30,660 | 235 | DS (no label) | Period Profile | PC | Web-based survey (GBD 2010; European surveys; Household surveys; USA surveys) | 18 | 100 |

| Sanderson et al. [43] | 2001 | Australia | Sinlge (Mental disorders) | ME | 20 | 19 | DS | NA | PTO & Rating scale & PR | Panel meeting | 19 | 87 |

| Schwarzinger et al. [64] | 2003 | Europe | Multiple | ME, nHP | 232 | 15 | DS & EQ-5D | Period Profile | VAS & PTO & TTO | Panel meeting | 15 | 93 |

| Steckling et al. [19] | 2017 | Global | Multiple | ME | 18 | 105 | DS & EQ-5D | Period Profile | VAS & PC/ Interpolation | Web-based survey | NA | 87 |

| Stouthard et al. [65] | 1997 | Netherlands | Multiple | ME | 38 | 175 | DS & EQ-5D | Period Profile & Annual Profile | VAS & PTO | Panel meeting & Questionnaire | 47 | 93 |

| Ustün et al. [66] | 1999 | Global | Multiple | HP, PT, PX, PM | 241 | 17 | DS | Period Profile | PR | Interview | 17 | 93 |

| Van Spijker et al. [67] | 2011 | Netherlands | Multiple | ME | 16 | 12 | DS & EQ-5D | Period Profile | VAS | Questionnaire | 12 | 100 |

| Yoon et al. [48] | 2000 | Korea | Single (Cancer) | ME | 19 | 12 | NA | NA | PTO & Interpolation | Delphi method | NA | 80 |

| Yoon et al. [68] | 2007 | Korea | Multiple | ME | 30 | 123 | NA | Period Profile | PTO & Interpolation | Panel meeting | 53 | 93 |

NA Not Available, DDW Dutch Disability Weight

Panel of judges

ME Medical experts, HP Health professionals, nHP Non-health professionals, PT Patients or people with disabilities, PX Patient proxies, PM Policy-makers, PP Population

Description of health states

DS Disease-specific health state description, EQ-5D European Quality of Life instrument that consists of five dimensions/attributes (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), EQ-6D EQ-5D appended with a cognitive dimension/attribute, CLAMES Classification and Measurement System of Functional Health, SF-36 HRQoL Short form health-related quality of life survey

Valuation methods for health states

VAS Visual analog scale, TTO Time trade-off PTO Person trade-off, PC Paired comparison, PHE Population health equivalence, PR Preference ranking, SG Standard gamble

CREATE

CREATE: Checklist for Reporting Valuation Studies instrument

Methodological design choices

Description of health states

Seven disability weights measurement studies (n = 7; 15%) used validated multi-attribute utility instruments [33, 35, 36, 39, 40, 55, 61]; such health-related instruments use preferences to develop norms for health states of disease. Six of these studies (n = 6) used the EQ-5D model [33, 35, 36, 39, 40, 61], while one study (n = 1) assessed disability weights for health conditions using the CLAMES methodology [55]. Moreover, a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data obtained new estimates of leprosy disability weights based on SF-36 health-related quality of life data [17]. Thirty disability weights measurement studies (n = 30; 65%) described the health states using the disease-specific system [8, 12–16, 18–20, 34, 37, 42, 43, 45, 46, 50, 51, 53, 54, 56–60, 62–67]. In these studies, the disease-specific health states were presented in terms of brief lay descriptions (or without label), or disability weight scenario analyses or a combination of a disease-specific description of health effects and generic instrument information. Eight studies did not report on the health state description system for the diseases that were valued [38, 41, 44, 47–49, 52, 68].

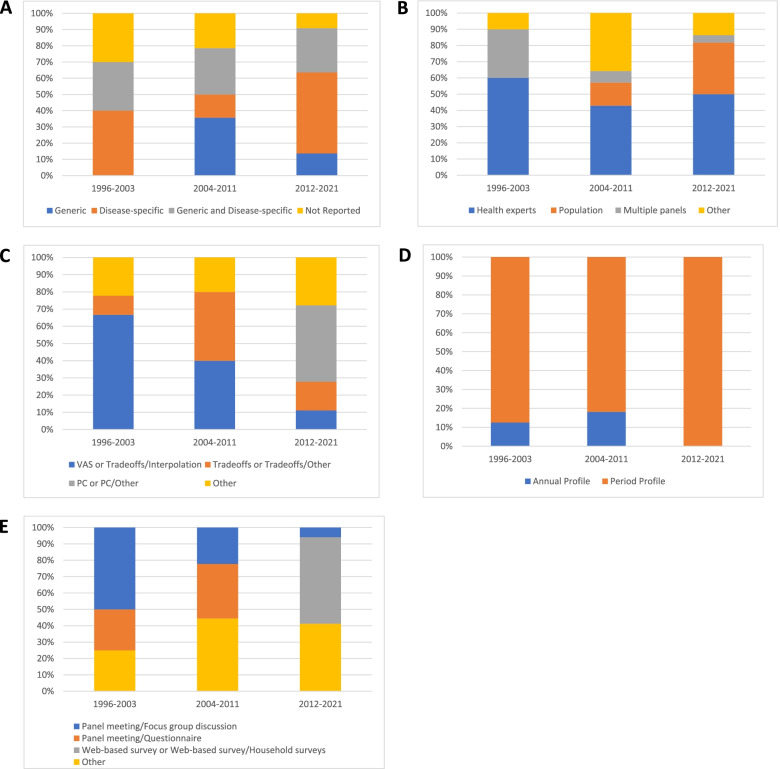

Around 30% of the disability weights measurement studies that were published during each period (i.e. 1996–2003, 2004–2011, and 2012–2021) used a combination of generic and disease-specific health descriptions to assess disability weights (Fig. 4 A). However, over the 2012–2021 period, half (50%) of the identified studies used disease-specific methods to depict health states of disease, a similar percentage to that of the 1996–2003 period (Fig. 4 A).

Fig. 4.

Evolution of methodological design choices in disability weights measurement studies: (A) Description of health states, (B) Panel of judges, (C) Valuation methods for health states, (D) Time Presentation, and (E) Surveying technique

The majority of the studies (53%) did not report on the process of evaluating the validity of health state descriptions. Some studies, however, reported that lay descriptions of health states were circulated to disease experts or health professionals for face validation purposes [12–14, 18, 20, 46, 50, 64, 65].

Notably, the number of health states valued in the included disability weights measurement studies varied from three [17] to 483 [8].

Panel of judges

Among the studies that did not estimate disability weights using multi-attribute utility instruments, 59% (n = 22) included panels of medical or clinical experts or health professionals [8, 18, 19, 37, 38, 41, 43, 44, 46–49, 53, 54, 56, 59, 60, 62, 63, 65, 67, 68]. Nine studies obtained health state preferences from a general population panel [12–17, 20, 34, 51], whereas six studies included more than one panel of judges [42, 45, 50, 52, 58, 66]. Specifically, Baltussen et al. [50] obtained disability weights based on general population and health professionals’ preferences and found that health professionals rated seven out of nine states of health as slightly to moderately less severe compared to lay people from the general population. A study conducted by Jelsma et al. [52] included medical experts’ and population preferences for multiple health states and showed strong differences among lay people and medical experts. Bakhshandeh et al. [45] showed differences between CVD disability weights obtained from patients, patients’ families, health professionals, and health professionals. Schwarzinger et al. [64] reported on the agreement level of disability weights among five Western European countries based on health professionals’ and non-health professionals’ preferences and showed a lower level of agreement in the cases of PTO disability weights and higher level of agreement in the cases of VAS and TTO disability weights. Nontarak et al. [42] found differences in disability weight estimates between patient and non-patient population preferences. Ustün et al. [66] showed significant differences in ranking of health conditions across 14 countries. Notably, Nontarak et al. [58] derived patients’ self-reported disability weights.

Additionally, the percentage of disability weight studies obtaining health preferences from a population-based panel increased from 14% (2004–2011) to 32% (2012–2021). In general, the percentage of studies that derived disability weights from a panel of health experts slightly decreased (Fig. 4 B).

The lowest number of judges identified in disability weight studies was nine [44]. The largest number of judges was seen in the Salomon et al. [20] study, a combined sample size consisting of 30,230 respondents from the GBD 2010 household surveys and 30,660 from the European disability weights measurement study.

Valuation methods for health states

Of the disability weight studies that did not use a multi-attribute utility instrument, 32% (n = 12) obtained health state preferences using trade-off or VAS methods (first step) and interpolation tasks (second step) [8, 19, 37, 38, 41, 48, 50, 54, 56, 64, 65, 68]. However, some studies combined a PC approach with other valuation techniques for health states [12–16, 20, 59, 62], whereas other studies used only trade-off [34, 44, 46, 49, 51] or rank [45, 52, 53, 60, 66] or VAS approach [67] to value the health states of disease.

The percentage of studies that followed a two-step approach to value health state preferences was higher during the 1996–2003 period, rather than the 2004–2011 and 2012–2021 periods (Fig. 4 C). After the 2004–2011 period, more and more disability weight studies used PC techniques to assess disability weights rather than trade-off tasks.

Time presentation

All disability weights measurement studies used the period profile approach. Three Dutch disability weights (DDW) studies [34, 51, 65] used the annual profile approach.

None of the disability weight studies published in the past 10 years used the annual profile approach (Fig. 4 D).

Surveying techniques

We identified several surveying techniques in disability weights measurement studies (Table 1). Most studies performed meetings or focus-group discussions with the panel of judges [18, 41, 43, 52, 56, 64, 68] or a combination of group discussions and individual questionnaires [34, 44, 50, 51, 65]. Six studies used web-based surveys to collect the data [13, 14, 19, 53, 59, 60]. Other studies performed interviews [42, 45, 58, 66]. Two studies obtained disability weights data using the Delphi method [46, 48]. Mixed surveying techniques were used in the GBD 2010 disability weights study (face-to-face or telephone survey and a web-based survey [12]) and in the South Korean disability weights study (household survey involving computer-assisted face-to-face interviews and a web-based survey [15]).

Between 1996 and 2013, half (50%) of the identified studies collected disability weight data by performing panel meetings of focus-group discussions (Fig. 4 E). Over the years, however, these surveying techniques have been eliminated, with web-based surveys or both web-based and household surveys (53%) appearing during the 2012–2021 period.

Discussion

Summary of findings and interpretation of results

This systematic literature review has provided insights into the methodological design choices that have been made to describe and value health states in disability weights measurement studies. We aimed to provide an update on studies estimating disability weights between the early-1996 and mid-2021 period. We gathered methodological approaches and surveying techniques from 46 unique disability weights measurement studies and we studied how these key design choices evolved over time.

Health state descriptions are an important matter in disability weights measurement studies. We found that half of the included studies published between 2012 and 2021 had used disease-specific descriptions in line with those of the GBD study. In general, from early-1996 to mid-2021, we observed an increased number of national disability weights studies using the GBD lay descriptions to depict each cause of the health states. This corresponds to validity, consistency, and therefore similar patterns of disability weights between national and GBD disability weights measurement studies. Additionally, a variety of disability weights studies (2012–2021) had used a combination of disease-specific and generic-preference instruments to describe and value states of health, compared to those published during the 1996–2003 and 2004–2011 periods. Although there are differences between those design choices, both can be applied to quantify the severity of a particular health state. However, describing health using generic instruments may result in information loss as the disease-specific symptoms are not described. Thus, generic health state descriptions are recommended to be used in combination with disease-specific descriptions to strengthen the standardization of the health state description system.

A noteworthy observation of this review is that, after 2010, the percentage of disability weights measurement studies deriving preferences from general population panels had more than doubled. Disability weights may be affected by the choice of the panel composition [69, 70]. Individual preferences obtained from patients differ from those of the population. It has also been shown that disability weight values differ between medical or health experts and the general population [45, 50, 52, 64, 66]. However, population-based panels can yield valid disability weight estimates as opposed to preferences obtained from patients or health professionals [71]. Driven by the fact that burden of disease studies is an important tool for decision-making processes and setting health priorities for populations, it is important to incorporate general populations’ perceptions [12, 71]. However, when the panel of judges consists of members of the general public, this may also mean that valid health state valuation data are more difficult to obtain. Since the general population often has no knowledge of or experience with the presented disease or health state itself, it is paramount to develop health descriptions that are valid and understandable to lay persons. Our study showed that the process of evaluating the validity of health state descriptions in disability weights measurement studies was often not reported.

Moreover, we identified a large variation in the size of the panel of judges. Based on the performed methodological quality assessment, we found a gap in the reporting of the calculation of the size of the panel. The size of the panel depends on the number of health states included for valuation and on the minimum number of observations per health state that is set by the researchers. However, the minimum number of observations per health state was often not reported. This might call for improvements in the reporting of future disability weights measurement studies.

Apart from the minimum number of observations per health state, the size of the panel also depends on the number of valuation tasks that each individual panel member performs. Our findings showed that the number of tasks per individual range from five [44] to 60 [59]. However, is highly important to take into account the aforementioned choice, as the vast majority of panel members will not be familiar with the health state valuation tasks, particularly in case of panels that consist of members of the general public. If the number of tasks per person is too small, the panel members will not be able to familiarize themselves with the task and gain an understanding of the tasks. On the other hand, if the number of tasks per person is too high, response fatigue may increase. Both may impact the quality of the health state valuations considerably.

Another finding of this review is that the majority of disability weights measurement studies used one or more than one valuation method to elicit preferences. However, most multi-country but also some single-country studies, conducted after 2012, estimated disability weights using the PC in combination with the PHE and/or the VAS techniques. However, two disability weights studies that used PHE to assess preferences from a general population sample showed that the quality of the PHE data was low and could not be used for the calculations of the disability weights [13, 14]. This indicates that the use of the PHE is most likely too complex to be used in a general population setting and more simplified valuation methods should be used in future disability weight studies in a similar setting and with similar surveying techniques. Other methodological applications have been developed, such as the DELPHI processes applied in two Korean disability weights studies [46, 48]; DELPHI technique allows for structured panel-group communication in order to deal with complex issues where knowledge is uncertain or incomplete [72]. An essential step in disability weights measurement studies is to transform health state valuation data into a disability weight that is anchored between 0 and 1. For cardinal methods, such as the VAS and TTO, this step is easier compared to ordinal methods, such as the PC. A review of mathematical methods that were used to transform health state valuation data into disability weights is out of the scope of our study. However, it is highly important that disability weights studies clearly describe the procedure that is followed to calculate disability weights from health state valuation data to improve reproducibility and comparability of disability weights measurement studies. Development of more detailed reporting guidelines for the transformation of health state valuation data into disability weights or health state utilities may facilitate reproducibility and comparability.

Additionally, the results of our systematic review showed that very few studies assessed annual profile disability weights and that over years the period health profile approach has been adopted more often. Several reasons can be discussed regarding the limited application of the annual health profile approach. First, it might not be feasible for panellists to imagine living a short-term condition over a period of 1 year as the annual profile approach assumes constant health over one full year. Second, it has been argued that the use of annual profile disability weights in burden of disease assessments would give undue weight to conditions with a mild and rapid course [73].

Moreover, most disability weights measurement studies (1996–2003) performed panel meetings or focus group discussions as surveying techniques, whereas from 2012 onwards household surveys and/or web-based surveys have frequently been used. The latter technique, may elicit selection bias, since internet users are over-represented among the study-participants. Another reason for this bias may be that individuals with a higher level of education use the internet more frequently than individuals with a lower level of education [74]. To overcome this bias, we recommend the selection of panels with certain characteristics (i.e. age, sex, socio-demographic information, or cultural background). Notably, a study conducted by Jelsma et al. suggests that cultural differences on valuations may have a strong effect among lay people compared to health experts [52].

Coverage of causes of disease and injury in different health states differs markedly among the multi-cause disability weights measurement studies. The GBD 1996 [8], the Estonian [56] and the updated Korean [60] set of disability weights cover a variety of health conditions compared to the DDW study [65]; however, the DDW study, on the other hand, provides a more detailed differentiation between disease stages, severities, treatment, and prognosis [65]. This allows more consistent modelling approaches when quantifying the burden of disease. Among the single-cause disability weights studies, we observed that more specific stages of disease are included. These studies were conducted either to develop disability weights that are not yet available from the GBD study effort (e.g., wrist osteoporotic fractures [49], chronic metallic mercury vapor intoxication [19] etc) or to estimate disability weights that were not available from the GBD study and have been applied in its latest iterations (e.g., harmful alcohol disorders [42], concussion [34], irritable bowel syndrome [51] etc).

Assessing the validity of disability weights is not an easy task as there is no gold standard for disability weights [9]. However, various methodological approaches have been suggested to evaluate the validity of disability weights. First, comparing the ranking of disability weights between similar studies and/or detecting if the disability weights of diseases or injuries increase according to their severity level (i.e., mild, moderate, severe) [9, 53, 60]. The latter approach tallies with the assessment of face validity and is therefore recommended to be used in future disability weights measurement studies. Second, Maertens de Noordhout et al. [75] suggested to compare EQ-5D’s DWs with utility weights; hence, utilization of EQ-5D health states in order to evaluate the validity of the disability weights has been previously applied [15].

Strengths and limitations of the study

An important limitation associated with this systematic literature review is that only one source was considered for grey literature searches. There is also a risk for publication bias because we did not search other languages than English. Moreover, it is possible that other disability weights measurement studies have been conducted but not published. Despite these limitations, we emphasize that this systematic literature review provides an extensive overview for understanding the methodological design choices and surveying techniques that were used in disability weights measurement studies. This review showed that from 1996 to 2021, the national disability weight applications have led to substantial changes in design choices and surveying techniques, allowing for comparability of the disability weight values. Finally, we sought to provide recommendations that may help to design and develop future disability weights measurement studies but also to evaluate the validity of disability weights.

Conclusions

Our systematic literature review reveals that a methodological uniformity between national and GBD disability weights measurement studies increased, especially from 2010 onwards. This uniformity relies on the health state descriptions, the choice of the panel composition, the time presentation, and the surveying techniques. However, in terms of valuation techniques that have been used to describe and value disability weights, there is a wide variation in national disability weights studies that persisted over time.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Umweltbundesamt (Projekt 154725, Az 60 430/0018). The authors wish to thank Sabrina Meertens-Gunput from the Erasmus MC Medical Library for developing the search strategy.

Abbreviations

- CLAMES

Classification and Measurement System of Functional Health

- CREATE

Checklist for Reporting Valuation Studies

- CVD

Cardiovascular Disease

- DALY

Disability-Adjusted Life Year

- DDW

Dutch Disability Weights

- DS

Disease-specific

- EQ-5D

European Quality of Life instrument – 5 Dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression)

- EQ-6D

EQ-5D appended with a cognitive dimension

- GBD

Global Burden of Disease

- HRQoL

Health-Related Quality of Life

- HP

Health Professionals

- ME

Medical Expert

- NA

Not Available

- nHP

Non-Health Professionals

- PC

Paired Comparison

- PHE

Population Health Equivalence

- PM

Policymakers

- PP

Population

- PR

Preference Ranking

- PT

Patients or people with disabilities

- PX

Patient proxies

- PTO

Person Trade-Off

- SF-36

Short form health-related quality of life survey

- SG

Standard Gamble

- TTO

Time Trade-Off

- VAS

Visual Analogue Scale

- YLD

Years Lived with Disability

- YLL

Years of Life Lost

Authors’ contributions

PC, JH, and SP developed the study design; PC: performed the screening, data extraction, and quality assessment; PC, JH, and SP analyzed and interpreted the data; PC and JH drafted the manuscript; SP, JW, EvdL, PC, and JH critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None declared.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Murray CJ. Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72:429–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Acharya AK. Understanding DALYs (disability-adjusted life years) J Health Econ. 1997;16:703–730. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(97)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Salomon JA, Mathers C. A critical examination of summary measures of population health. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:981–994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LA MCJL, CDE M. Ethics, measurement and applications. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. Summary measures of population health: concepts. [Google Scholar]

- 5.GBD Diseases and injuries collaborators: global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2019;2020(396):1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Evidence-based health policy--lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science. 1996;274:740–743. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Essink-Bot ML, Bonsel GJ. In: How to derive disability weights? In Summary Measures of Population Health: Concepts, Ethics, Measurement and Applications. CJL M, Lopez AD, Salomon JA, editors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haagsma JA, Polinder S, Cassini A, Colzani E, Havelaar AH. Review of disability weight studies: comparison of methodological choices and values. Popul Health Metrics. 2014;12:20. doi: 10.1186/s12963-014-0020-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang P, Woodward M, Shen J, Wu Y. Individual disability-adjusted life year: a summary health outcome Indicator used for prospective studies. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brazier J, Deverill M, Green C. A review of the use of health status measures in economic evaluation. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1999;4:174–184. doi: 10.1177/135581969900400310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salomon JA, Vos T, Hogan DR, Gagnon M, Naghavi M, Mokdad A, Begum N, Shah R, Karyana M, Kosen S, et al. Common values in assessing health outcomes from disease and injury: disability weights measurement study for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2129–2143. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61680-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nomura S, Yamamoto Y, Yoneoka D, Haagsma JA, Salomon JA, Ueda P, Mori R, Santomauro D, Vos T, Shibuya K. How do Japanese rate the severity of different diseases and injuries?-an assessment of disability weights for 231 health states by 37,318 Japanese respondents. Popul Health Metrics. 2021;19:21. doi: 10.1186/s12963-021-00253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haagsma JA, Maertens de Noordhout C, Polinder S, Vos T, Havelaar AH, Cassini A, Devleesschauwer B, Kretzschmar ME, Speybroeck N, Salomon JA. assessing disability weights based on the responses of 30,660 people from four European countries. Popul Health Metrics. 2015;13:10. doi: 10.1186/s12963-015-0042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ock M, Ahn J, Yoon SJ, Jo MW. Estimation of disability weights in the general population of South Korea using a paired comparison. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neethling I, Jelsma J, Ramma L, Schneider H, Bradshaw D. Disability weights from a household survey in a low socio-economic setting: how does it compare to the global burden of disease 2010 study? Glob Health Action. 2016;9:31754. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.31754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nanjan Chandran SL, Tiwari A, Lustosa AA, Demir B, Bowers B, Albuquerque RGR, Prado RBR, Lambert S, Watanabe H, Haagsma J, Richardus JH. Revised estimates of leprosy disability weights for assessing the global burden of disease: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poenaru D, Pemberton J, Frankfurter C, Cameron BH, Stolk E. Establishing disability weights for congenital pediatric surgical conditions: a multi-modal approach. Popul Health Metrics. 2017;15:8. doi: 10.1186/s12963-017-0125-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steckling N, Devleesschauwer B, Winkelnkemper J, Fischer F, Ericson B, Kramer A, et al. Disability weights for chronic mercury intoxication resulting from Gold mining activities: results from an online pairwise comparisons survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Salomon JA, Haagsma JA, Davis A, de Noordhout CM, Polinder S, Havelaar AH, Cassini A, Devleesschauwer B, Kretzschmar M, Speybroeck N, et al. Disability weights for the global burden of disease 2013 study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e712–e723. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuchiya A, Dolan P. The QALY model and individual preferences for health states and health profiles over time: a systematic review of the literature. Med Decis Mak. 2005;25:460–467. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05276854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Froberg D, Kane RL. Methodology for measuring health-state preferences--I: Measurement strategies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:345–354. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devlin NJ, Brooks R. EQ-5D and the EuroQol group: past, present and future. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15:127–137. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feeny D, Furlong W, Boyle M, Torrance GW. Multi-attribute health status classification systems. Health Utilities Index. Pharmacoeconomics. 1995;7:490–502. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199507060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stouthard M. Disability weights for diseases: a modified protocol and results for a Western European region. Eur J Public Health. 2000;10:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolan P, Olsen JA, Menzel P, Richardson J. An inquiry into the different perspectives that can be used when eliciting preferences in health. Health Econ. 2003;12:545–551. doi: 10.1002/hec.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care. 1997;35:1095–1108. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiedermann W, Frick U. Using surveys to calculate disability-adjusted life-year. Alcohol Res. 2013;35:128–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janssen MF, Birnie E, Bonsel G. Feasibility and reliability of the annual profile method for deriving QALYs for short-term health conditions. Med Decis Mak. 2008;28:500–510. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07312711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie F, Pickard AS, Krabbe PF, Revicki D, Viney R, Devlin N, Feeny D. A checklist for reporting valuation studies of multi-attribute utility-based instruments (CREATE) Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:867–877. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0292-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gabbe BJ, Lyons RA, Simpson PM, Rivara FP, Ameratunga S, Polinder S, Derrett S, Harrison JE. Disability weights based on patient-reported data from a multinational injury cohort. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94:806–816C. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.172155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haagsma JA, van Beeck EF, Polinder S, Hoeymans N, Mulder S, Bonsel GJ. Novel empirical disability weights to assess the burden of non-fatal injury. Inj Prev. 2008;14:5–10. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.017178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haagsma JA, Polinder S, van Beeck EF, Mulder S, Bonsel GJ. Alternative approaches to derive disability weights in injuries: do they make a difference? Qual Life Res. 2009;18:657–665. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9484-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyons RA, Kendrick D, Towner EM, Christie N, Macey S, Coupland C, Gabbe BJ, Group UKBoIS Measuring the population burden of injuries--implications for global and national estimates: a multi-centre prospective UK longitudinal study. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asadi R, Afshari R, Dadpour B. The measurement of disability weights for 18 prevalent acute poisoning conditions. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2016;35:1033–1040. doi: 10.1177/0960327115617229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basiri A, Mousavi SM, Naghavi M, Araghi IA, Namini SA. Urologic diseases in the Islamic Republic of Iran: what are the public health priorities? East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:1338–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brennan DS, Spencer AJ, Roberts-Thomson KF. Quality of life and disability weights associated with periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 2007;86:713–717. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brennan DS, Spencer AJ. Disability weights for the burden of oral disease in South Australia. Popul Health Metrics. 2004;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Havelaar AH, de Wit MA, van Koningsveld R, van Kempen E. Health burden in the Netherlands due to infection with thermophilic Campylobacter spp. Epidemiol Infect. 2000;125:505–522. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800004933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nontarak JAS, Callinan S. A comparison of disability weights for alcohol use disorders. J Health Sci Med Res. 2021;39.

- 43.Sanderson K, Andrews G. Mental disorders and burden of disease: how was disability estimated and is it valid? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35:668–676. doi: 10.1080/0004867010060517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong KS, Saver JL. Quantifying the value of stroke disability outcomes: WHO global burden of disease project disability weights for each level of the modified Rankin scale. Stroke. 2009;40:3828–3833. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.561365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bakhshandeh HNK, Zeraati H, Forouzanfar MH, Noohi F, Sadeghpour A, et al. Health state valuation in Iran: An exercise on cardiovascular diseases using visual analogue scale method. Iran J Public Health. 2009;1;38(4):46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cho JY, Hong KS, Kim HJ, Kim SH, Min JH, Kim NH, Ahn SW, Park MS, An JY, Kim BJ, Kim W. Disability weight for each level of the expanded disability status scale in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2014;20:1217–1223. doi: 10.1177/1352458513518259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi KS, Park JH, Lee KS. Disability weights for cancers in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:808–813. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.6.808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoon SJYS, Yong Ik K, Chang Yup K, Hyejung C. Estimate the disability weight of major cancers in Korea using Delphi methods. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;17.

- 49.Bae G, Kim E, Kwon HY, An J, Park J, Yang H. Disability weights for osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures in South Korea. J Bone Metab. 2019;26:83–88. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2019.26.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baltussen RM, Sanon M, Sommerfeld J, Wurthwein R. Obtaining disability weights in rural Burkina Faso using a culturally adapted visual analogue scale. Health Econ. 2002;11:155–163. doi: 10.1002/hec.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haagsma JA, Havelaar AH, Janssen BM, Bonsel GJ. Disability adjusted life years and minimal disease: application of a preference-based relevance criterion to rank enteric pathogens. Popul Health Metrics. 2008;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jelsma J, Chivaura VG, Mhundwa K, De Weerdt W, de Cock P. The global burden of disease disability weights. Lancet. 2000;355:2079–2080. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)73538-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim YE, Jo MW, Park H, Oh IH, Yoon SJ, Pyo J, Ock M. Updating disability weights for measurement of healthy life expectancy and disability-adjusted life year in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e219. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kruijshaar ME, Hoeymans N, Spijker J, Stouthard ME, Essink-Bot ML. Has the burden of depression been overestimated? Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:443–448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kwong JCCN, Campitelli MA, Ratnasingham S, Daneman N, Deeks SL, Manuel DG. Ontario burden of infectious disease study. Toronto: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lai T, Habicht J, Kiivet RA. Measuring burden of disease in Estonia to support public health policy. Eur J Pub Health. 2009;19:541–547. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mathers CD, Vos ET, Stevenson CE, Begg SJ. The Australian burden of disease study: measuring the loss of health from diseases, injuries and risk factors. Med J Aust. 2000;172:592–596. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb124125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nontarak J, Assanangkornchai S, Callinan S. Patients' self-reported disability weights of top-ranking diseases in Thailand: do they differ by socio-demographic and illness characteristics? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Ock M, Lee JY, Oh IH, Park H, Yoon SJ, Jo MW. Disability weights measurement for 228 causes of disease in the Korean burden of disease study 2012. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(Suppl 2):S129–S138. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.S2.S129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ock M, Park B, Park H, Oh IH, Yoon SJ, Cho B, Jo MW. Disability weights measurement for 289 causes of disease considering disease severity in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2019;34:e60. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Park JI, Jung HH. Estimation of years lived with disability due to noncommunicable diseases and injuries using a population-representative survey. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Piao XTS, Takemura Y, Ichikawa N, Kida R, Kunie K, et al. Disability weights measurement for 17 diseases in Japan: a survey based on medical professionals. Economic Analysis and Policy. 2021;70:238–248. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rehm J, Frick U. Establishing disability weights from pairwise comparisons for a US burden of disease study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2013;22:144–154. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schwarzinger M, Stouthard ME, Burstrom K, Nord E. Cross-national agreement on disability weights: the European disability weights project. Popul Health Metrics. 2003;1:9. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stouthard MEA E-BM. Bonsel GJ, Barendregt JJ, PGN K, de Water HPA V, Gunning-Schepers LJ. Van der Maas PJ: Disability Weights for Diseases in the Netherlands. The Netherlands Amsterdam: Inst. Sociale Geneeskunde; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ustun TB, Rehm J, Chatterji S, Saxena S, Trotter R, Room R, Bickenbach J. Multiple-informant ranking of the disabling effects of different health conditions in 14 countries. WHO/NIH joint project CAR study group. Lancet. 1999;354:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Spijker BA, van Straten A, Kerkhof AJ, Hoeymans N, Smit F. Disability weights for suicidal thoughts and non-fatal suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2011;134:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoon SJ, Bae SC, Lee SI, Chang H, Jo HS, Sung JH, Park JH, Lee JY, Shin Y. Measuring the burden of disease in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:518–523. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.3.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dolan P. The effect of experience of illness on health state valuations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:551–564. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00532-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schwappach DL. Are preferences for equality a matter of perspective? Med Decis Mak. 2005;25:449–459. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05276861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Field MJ, Gold MR. Summarizing population health: directions for the development and application of population metrics. In. Washington D.C.: Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Summary Measures of Population Health; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.MacLennan S, Kirkham J, Lam TBL, Williamson PR. A randomized trial comparing three Delphi feedback strategies found no evidence of a difference in a setting with high initial agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;93:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vos T. In: The case against annual profiles for the valuation of disability weights. In Summary Measures of Population Health: Concepts, Ethics, Measurement and Application. CJL M, Salomon JA, Mathers CD, Lopez AD, editors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bethlehem J. Selection Bias in web surveys. Int Stat Rev. 2010;78:161–188. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maertens de Noordhout C, Devleesschauwer B, Gielens L, Plasmans MHD, Haagsma JA, Speybroeck N. Mapping EQ-5D utilities to GBD 2010 and GBD 2013 disability weights: results of two pilot studies in Belgium. Arch Public Health. 2017;75(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.