Abstract

Background

Several chronic conditions have been associated with a higher risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), including asthma. However, there are conflicting conclusions regarding risk of severe disease in this population.

Objective

To understand the impact of asthma on COVID-19 outcomes in a cohort of hospitalized patients and whether there is any association between asthma severity and worse outcomes.

Methods

We identified hospitalized patients with COVID-19 with confirmatory polymerase chain reaction testing with (n = 183) and without asthma (n = 1319) using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes between March 1 and December 30, 2020. We determined asthma maintenance medications, pulmonary function tests, highest historical absolute eosinophil count, and immunoglobulin E. Primary outcomes included death, mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and ICU and hospital length of stay. Analysis was adjusted for demographics, comorbidities, smoking status, and timing of illness in the pandemic.

Results

In unadjusted analyses, we found no difference in our primary outcomes between patients with asthma and patients without asthma. However, in adjusted analyses, patients with asthma were more likely to have mechanical ventilation (odds ratio, 1.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-2.44; P = .04), ICU admission (odds ratio, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.09-2.29; P = .02), longer hospital length of stay (risk ratio, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.09-1.55; P < .003), and higher mortality (hazard ratio, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.01-2.33; P = .04) compared with the non-asthma cohort. Inhaled corticosteroid use and eosinophilic phenotype were not associated with considerabledifferences. Interestingly, patients with moderate asthma had worse outcomes whereas patients with severe asthma did not.

Conclusion

Asthma was associated with severe COVID-19 after controlling for other factors.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is the novel coronavirus responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a global pandemic that has to date affected 418 million people worldwide, with more than 78 million total cases in the United States as of February 2022.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified patients with several comorbidities, including chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma, to have high risk for severe COVID-19.2 Epidemiologic studies have elucidated several risk factors for severe illness, including age, diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension (HTN), pulmonary disease, and immunosuppression.3, 18 Chronic lung disease is a risk factor for illness severity in COVID-19, including need for hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and mortality.4 However, there have been conflicting reports on the role of asthma as a risk factor for more severe disease, with published studies showing lower mortality between asthma and non-asthma cohorts,5 no difference,6 , 7 or increased mortality.8 The current literature is challenging to interpret given a lack of uniform definitions of asthma outcomes and large variability of comorbidities accounted for in statistical analyses.

Over the past year, management of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients has changed substantially as data regarding use of therapeutics have evolved with ongoing research. With initial uncertainty regarding the use of corticosteroids early in the pandemic, many published guidelines discouraged the use of corticosteroids for treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 alone9 until results from the RECOVERY trial found dexamethasone use resulted in mortality benefits for those receiving supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation in July 2020.10 Corticosteroids are a cornerstone of therapy in the treatment of acute asthma exacerbations, most of which are viral mediated.11 It is unclear whether the evolution of COVID-19 care as the pandemic progressed has resulted in differential outcomes for patients with asthma.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of asthma on COVID-19–related outcomes in a cohort of hospitalized patients at a tertiary academic center. The secondary objective was to determine how COVID-19–related outcomes have changed over the past year, specifically focused on the cohorts before and after dexamethasone became widely accepted as being beneficial in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. We hypothesize that asthma will be associated with an increased risk of poor outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19; however, we anticipate that this increased risk will not be evenly distributed and that some asthma phenotypes may be more at risk than others.

Methods

Identification of Patients With Asthma and Coronavirus Disease 2019

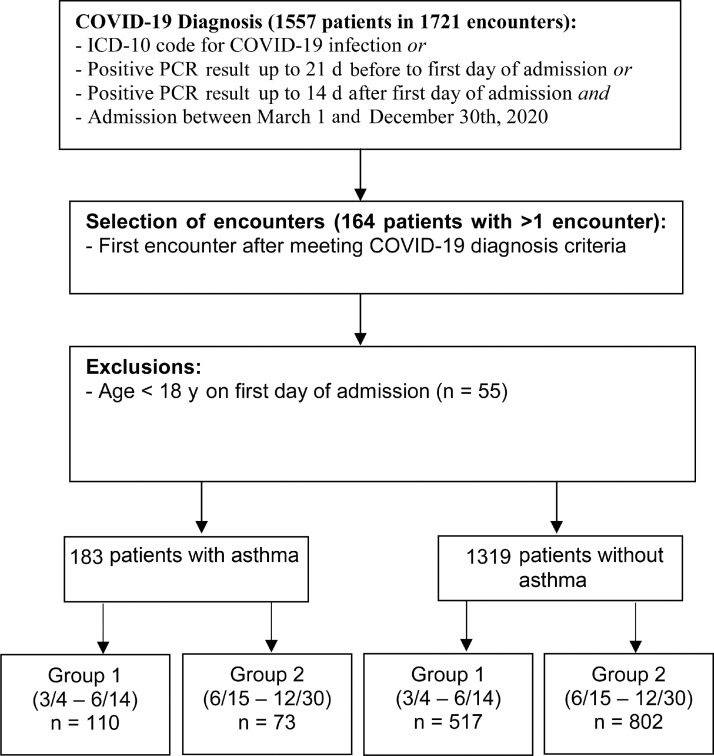

This retrospective study was conducted at a single academic institution using databases derived from the electronic health record. Patients with COVID-19 were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, code for COVID-19 with confirmatory polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing at our institution or done at an outside institution, a positive PCR test result during the admission, or a previous positive PCR test result 21 days before or 14 days after the admission. Patients admitted between March 4 and December 31, 2020, were included. This cohort included patients who were not vaccinated against COVID-19 because vaccines were not widely available at that time. The presence of asthma was identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, code of J45.xx before, during, or after the encounter, which yielded 140 encounters in the first group (March, 2020 to June 14, 2020) and 127 encounters in the second group (June 15, 2020 to December, 2020). Patients were divided based on months of the year in 2020 because treatments for COVID-19 rapidly changed in the latter part of the year and this was a potential confounder. Verification of asthma diagnosis was performed by clinicians using chart review. Patients with an incorrect history of asthma (n = 12) were reassigned to the non-asthma cohort. Exclusion criteria included pediatric patients (n = 55). For patients with multiple encounters (n = 30), the first encounter was selected. Manual chart abstraction was performed on the remaining encounters to confirm asthma status using clinician diagnosis of asthma with prescribed medications for asthma. This yielded a final asthma cohort of 183 patients, 110 patients in group 1 and 73 patients in group 2. Our non-asthma cohort consisted of 1319 adult patients (age >18 years) who met our definition of COVID-19 positivity as mentioned previously without a diagnosis of asthma (Fig 1 ).

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting patient selection for asthma and non-asthma cohorts. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Identification of Asthma Severity and Phenotype

For each patient with asthma, asthma-specific variables including maintenance medications and pulmonary function tests were abstracted after manual chart review. Asthma severity was classified based on home medications using Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) strategy 2020 classification (steps 1 to 5).12 Analyses compared GINA steps 1 and 2 (mild) vs step 3 (moderate) vs steps 4 and 5 (severe). Asthma phenotype (eosinophilic vs non-eosinophilic) was also identified using highest absolute eosinophil count (AEC) in the preceding 24 months (greater than or equal to 0.3 K/µL considered eosinophilic asthma), and highest immunoglobulin (Ig)E level (kU/L) was noted. Severity was also compared by inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) use (taking ICS vs not taking ICS).

Outcomes

Outcomes included (1) death, (2) ICU admission, (3) mechanical ventilation, (4) total hospital length of stay (LOS), and (5) ICU LOS.

Identification of Clinical Characteristics and Comorbidities

We identified the initial laboratory measurements for each patient, including white blood cell count, AECs, absolute lymphocyte counts, ferritin, D-dimer, and C-reactive protein (CRP). We utilized Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms technology to identify concepts that matched our comorbidities of interest, including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), COPD, HTN, coronary artery disease (CAD), diabetes mellitus, and obesity (based on a body mass index > 30), in both asthma and non-asthma cohorts. Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was used to assess global comorbidity burden.13 Smoking status was also assessed and classified as current, former, never smoker, or unknown. We identified whether patients were transferred from an outside facility to account for potential selection bias given the likelihood that these patients were transferred owing to more severe illness that required a tertiary care center.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive characteristics of asthma vs non-asthma were provided using medians and interquartile ranges for continuous characteristics and frequencies and percentages for categorical characteristics. Descriptions were also provided among patients with asthma by GINA step, eosinophilic asthma, and ICS use. Survival was analyzed using Cox proportional hazards models. The binary ICU admission and mechanical ventilation outcomes were modeled using logistic regression. Total hospital and ICU LOS in days was modeled using negative binomial regression with a log-link function. Separate models were fit for each asthma variable (ie, asthma vs no asthma, GINA step, eosinophilic asthma, ICS use). All models were adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, transfer status, smoking status, time of illness in the pandemic (group 1 vs 2), OSA, COPD, HTN, CAD, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and CCI. These potential confounders were selected a priori based on the literature and plausibility. Unadjusted models for each of these variables are also reported. Analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Comparison of Baseline Demographics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes in Patients With and Without Asthma With Coronavirus Disease 2019

The median age of patients with asthma was significantly lower (56 years, P < .001) vs patients without asthma (62 years) (Table 1 ). There was also a significant difference in sex representation with more patients with asthma (65%) being of female sex than patients without asthma (41%, P < .001). There was no difference in race across both cohorts. The number of outside hospital transfers was also similar between cohorts, accounting for 20% of the asthma cohort and 20% of the non-asthma cohort (Table 1). The prevalence of asthma in our cohort was 12.2%, consistent with the reported asthma prevalence between 7.4% and 17% in nationwide cohorts14 , 15 and the asthma prevalence statewide.16

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients With and Without Asthma

| Characteristic | Asthma (N = 183) |

Non-asthma (N = 1319) |

Pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 56 (43.0-66.0) | 62.0 (49.0-72.0) | <.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 119 (65) | 547 (41) | <.001 |

| Race, n (%) | .18 | ||

| American Indian/Alaskan native | 0 (0) | 6 (0) | |

| Asian | 4 (2) | 46 (3) | |

| Black | 63 (34) | 327 (25) | |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| White | 100 (55) | 810 (61) | |

| Other | 8 (4) | 67 (5) | |

| Unknown | 8 (4) | 62 (5) | |

| Hispanic | 6 (3) | 41 (3) | .90 |

| Outside hospital transfers, n (%) | 37 (20) | 270 (20) | .94 |

| Admit group, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| 1 (March 4-June 14) | 110 (60) | 518 (39) | |

| 2 (June 15-December 31) | 73 (40) | 801 (61) | |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0-5.0) | 2.0 (0.0-5.0) | .002 |

| Comorbid diseases, n (%) | |||

| OSA | 59 (32) | 200 (15) | <.001 |

| COPD | 12 (7) | 104 (8) | .53 |

| Hypertension | 86 (47) | 578 (44) | .42 |

| CAD | 23 (13) | 175 (13) | .79 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 55 (30) | 382 (29) | .76 |

| Obesity | 118 (64) | 631 (48) | <.001 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | .72 | ||

| Current | 4 (2) | 46 (3) | |

| Former | 52 (28) | 402 (30) | |

| Never | 89 (49) | 605 (46) | |

| Unknown | 38 (21) | 266 (20) | |

| Laboratory values at presentation | |||

| White blood cell count (cells/µL), median (IQR) | 7.2 (5.0-10.3) | 7.1 (5.1-10.1) | .95 |

| Ferritin (mg/L), median (IQR)b | 499.3 (192.2-1089.4) | 691.8 (303.5-1366.1) | .001 |

| D-dimer (mcg/ml), median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.6-2.6) | 1.1 (0.6-2.1) | .92 |

| CRP (mg/L), median (IQR) | 8.0 (4.0-14.7) | 7.7(3.8 – 15.7) | .98 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/µL), median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.6-1.3) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | .78 |

Abbreviations: ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; IQR, interquartile range; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

NOTE. Missing data from non-asthma cohort included 332 without ferritin, 363 without D-dimer, 357 without CRP, and 69 without ALC count.

Note- Bolded p-values are statistically significant using the cut off value of p<.05.

P value represents Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

Missing data from asthma cohort included 15 without ferritin, 22 without D-dimer, 17 without CRP, 5 without ALC.

COVID-19–positive patients with asthma were more likely to have OSA (32% as compared with 15%, P < .001) and to be obese (64% vs 48%, P < .001) (Table 1) than patients without asthma. There was no relevant difference among the prevalence of COPD, HTN, CAD, and diabetes mellitus between the 2 groups. The CCI was significantly higher in the patients with asthma with a median of 3.0 compared with 2.0 in patients without asthma (P = .002) (Table 1). There was no difference in smoking status between the asthma and non-asthma cohorts.

Baseline Laboratory Data of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Based on Asthma Status

When comparing baseline laboratory values across patient groups, we found no difference between the asthma and non-asthma cohorts in the median absolute lymphocyte count, CRP, or D-dimer; however, patients with asthma had considerably lower mean ferritin levels (499.3 [192.2-1089.4] vs 691.8 [303.5-1366.1] mg/L) as compared with those without asthma (Table 1). There was no difference between patients with eosinophilic asthma and patients with non-eosinophilic asthma in baseline laboratory values; however, when stratified by GINA step, patients with moderate asthma (GINA 3) had higher CRP and ferritin levels compared with patients with mild (GINA 1-2) or severe (GINA 4-5) asthma: median CRP 7.7 vs 15.2 vs 6.0 and median ferritin 509.9 vs 683.9 vs 330.9 for mild, moderate, and severe, respectively (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Asthma Cohort, Stratified by GINA Step Therapy

| GINA step therapy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Asthma (N = 183) |

Mild asthma (GINA steps 1 & 2)(N = 104) | Moderate asthma (GINA step 3)(N = 29) | Severe asthma (GINA steps 4 & 5)(N = 49) | P |

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 56 (43.0-66.0) | 53.0 (39.5-64.0) | 63.0 (54.0-67.0) | 59.0 (53.0-67.0) | .03 |

| Female, n (%) | 119 (65) | 67 (64) | 20 (69) | 32 (65) | .90 |

| Race, n (%) | .45 | ||||

| American Indian/Alaskan native | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Asian | 4 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | |

| Black | 63 (34) | 37 (36) | 10 (34) | 15 (31) | |

| White | 100 (55) | 54 (52) | 14 (48) | 32 (65) | |

| Other | 8 (4) | 5 (5) | 2 (7) | 1 (2) | |

| Unknown | 8 (4) | 6 (6) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | |

| Transferred from outside hospital, n (%) | 37 (20) | 29 (28) | 4 (14) | 4 (8) | .01 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0-5.0) | 2.0 (1.0-5.0) | 3.0 (1.0-5.0) | 4.0 (1.0-7.0) | .04 |

| Comorbid diseases, N (%) | |||||

| OSA | 59 (32) | 28 (27) | 6 (21) | 25 (51) | .004 |

| COPD | 12 (7) | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | 9 (18) | .001 |

| Hypertension | 86 (47) | 43 (41) | 12 (41) | 31 (63) | .03 |

| CAD | 23 (13) | 10 (10) | 4 (14) | 9 (18) | .31 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 55 (30) | 28 (27) | 17 (35) | 17 (35) | .53 |

| Obesity | 118 (64) | 64 (62) | 21 (72) | 33 (67) | .51 |

| Laboratory values at presentation | |||||

| White blood cell count (cells/µL), median (IQR) | 7.2 (5.0-10.3) | 6.9 (4.8-11.0) | 8.8 (5.0-10.5) | 7.3 (5.3-9.2) | .91 |

| Ferritin (mg/L), median (IQR) | 499.3 (192.2-1089.4) | 509.9 (213.2-1025.1) | 683.9 (425.8-1472.0) | 330.9 (154.6-762.1) | .04 |

| D-dimer (mcg/ml), median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.6-2.6) | 1.2 (0.6-2.7) | 1.4 (0.5-3.7) | 0.8 (0.5-1.5) | .16 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L), median (IQR) | 8.0 (4.0-14.7) | 7.7 (4.1-14.5) | 15.2 (7.9-21.6) | 6.0 (2.8-9.3) | <.001 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/µL), median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.6-1.3) | 1.0 (0.7-1.3) | 1.0 (0.7-1.1) | 1.0 (0.5-1.4) | .92 |

| Eosinophilic asthma, N (%) | |||||

| Historical AEC (median [IQR]) | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) | 0.3 (0.1-0.7) | .04 |

| Non-eosinophilic | 105 (58) | 66 (63) | 16 (55) | 23 (50) | |

| Eosinophilic | 59 (33) | 25 (24) | 12 (41) | 21 (46) | |

| Cannot be determined | 16 (9) | 13 (13) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) | |

| Asthma medications, N (%) | |||||

| Biologics | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (13) | <.001 |

| Leukotriene antagonist | 39 (21) | 14 (14) | 4 (14) | 20 (41) | <.001 |

| Long-acting beta agonist | 66 (36) | 3 (3) | 20 (69) | 43 (90) | <.001 |

| Long-acting muscarinic antagonist | 18 (10) | 1 (1) | 2 (7) | 15 (31) | <.001 |

| Maintenance oral corticosteroids | 7 (4) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (8) | .07 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 87 (48) | 12 (12) | 27 (93) | 47 (96) | <.001 |

| Low dose | 26 (30) | 11 (85) | 13 (48) | 1 (2) | <.001 |

| Medium dose | 44 (50) | 1 (8) | 14 (52) | 29 (62) | <.001 |

| High dose | 18 (20) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 17 (36) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary function tests n = 64 (18 mild asthma, 14 moderate asthma, 32 severe asthma) | |||||

| FEV1 (L), median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.5-2.8) | 2.7 (2.0-3.3) | 1.8 (1.1-2.5) | 1.6 (1.4-2.4) | .21 |

| FEV1 (%), median (IQR) | 76.0 (53.0-90.0) | 83.0 (78.0-96.0) | 68.5 (43.0-86.0) | 68.5 (54.0-87.0) | .60 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio, median (IQR) | 74.0 (62.0-80.0) | 79.5 (74.0-82.0) | 74.0 (69.2-83.0) | 68.0 (62.0-76.0) | .80 |

| FEF 25-75 (%), median (IQR) | 49.0 (27.0-76.0) | 69.5 (54.0-92.0) | 43.0 (25.0-64.0) | 40.0 (27.0-60.0) | .10 |

Abbreviations: AEC, absolute eosinophil count; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEF, forced expiratory flow; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

NOTE. Absolute eosinophil count, K/µL # pulmonary function tests were available for 64 asthma patients (18 mild, 14 moderate and 32 severe). All other labs < 12% missing.

Note- Bolded p values meet statistical significance using cut off of p < .05.

Stratification of Asthma Severity by Global Initiative for Asthma Step, Eosinophilia, and Inhaled Corticosteroid Use

Among COVID-19–positive patients with asthma, there were 104 patients with mild asthma (GINA steps 1 and 2), 29 patients with moderate asthma (GINA step 3), and 49 patients with severe asthma (GINA steps 4 and 5) (Table 2). When stratified by highest historical AEC, 33% of the patients were characterized with having eosinophilic asthma phenotype and 58% had non-eosinophilic asthma (Table 2). The median eosinophil count was 200 cells/µL, and the median IgE level was 177.5 kU/L, but prior IgE level was missing on 163 patients with asthma; therefore, we did not perform further analyses utilizing this variable. There were 16 patients without asthma phenotype determination given lack of AEC before index hospitalization (Table 2).

In terms of maintenance medications among patients with asthma, 48% were on ICS, 36% on long-acting β-agonists, 10% on long-acting anti-muscarinic antagonists, 21% on leukotriene receptor antagonists, 4% on maintenance oral corticosteroids, and 3% on biologics. Pre–COVID-19 pulmonary function tests were available on a third of the cohort, and the median percentage of forced expiratory volume in 1 second was 76%, median forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio 74%, and forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% 49% (Table 2). Compared with GINA step, patients with mild asthma were younger than those with moderate or severe asthma, more likely to be transferred from an outside facility, and less likely to have a eosinophilic phenotype (Table 2). There were no relevant differences in race, ethnicity across GINA steps. In terms of comorbidity burden, patients with moderate and severe asthma had a median CCI score of 3 and 4, respectively, which is higher than patients with mild asthma (CCI 2, P = .04). Patients with GINA steps 4 to 5 asthma were more likely to have OSA, COPD, and HTN compared with patients with GINA steps 1 to 3 (P = .004, P = .001, and P = .03, respectively) (Table 2).

Outcomes of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Based on Asthma Status

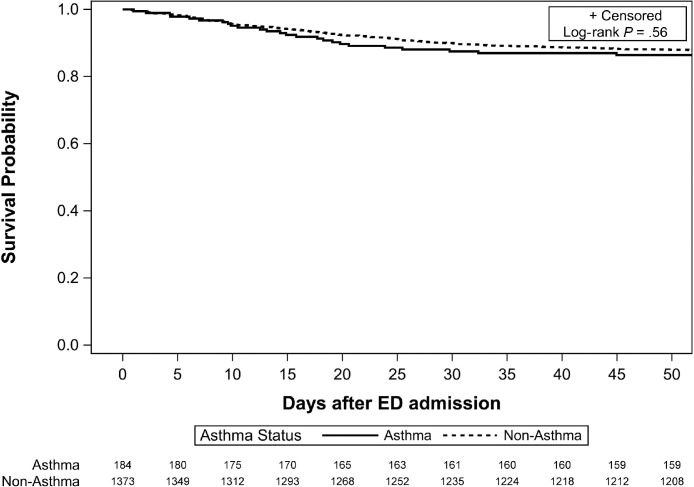

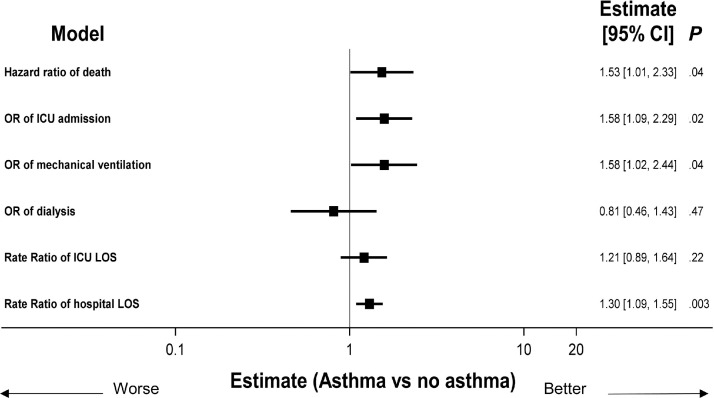

With a primary end point of survival probability, the unadjusted model did not reveal a substantial difference in survival between patients with and without asthma (Fig 2 ). In addition, there were no unadjusted differences in the other COVID-19–related outcomes of interest. However, in adjusted models, which accounted for age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, timing of illness in the pandemic, transfer status, comorbidities, and CCI score, a statistically important association between asthma and worse outcomes, such as death, mechanical ventilation, ICU admission, and hospital LOS, was found (Fig 3 ). Using multivariable regression models, the hazard ratio for death was 1.53 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01-2.33; P = .04) for patients with asthma (Fig 3). Overall, patients with asthma also had higher risk for mechanical ventilation (odds ratio [OR], 1.58; 95% CI, 1.02-2.44; P = .04), ICU admission (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.09-2.29; P = .02), and longer hospital LOS (risk ratio [RR], 1.30; 95% CI, 1.09-1.55; P < .003). There were no differences in the cohorts in terms of need for renal replacement therapy or longer ICU LOS (Fig 3).

Figure 2.

Survival by asthma status. ED, emergency department.

Figure 3.

Impact of asthma on outcomes. All models adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, transfer status, OSA, COPD, hypertension, CAD, diabetes mellitus, obesity, CCI, and smoking status. Cox proportional hazards models used for death; logistic regression used for ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and dialysis; negative binomial regression used for ICU and hospital LOS. CAD, coronary artery disease; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; OR, odds ratio; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

Differences in Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Based on Global Initiative for Asthma Step, Asthma Phenotype, and Inhaled Corticosteroid Use

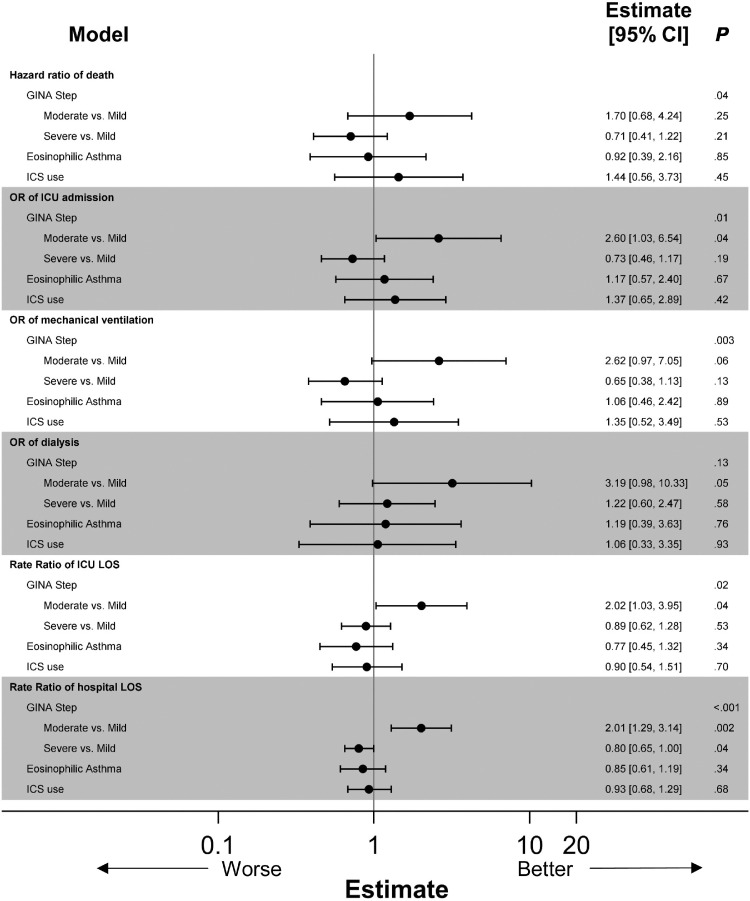

We assessed patients based on asthma severity and noted that patients with moderate asthma had a higher odds of ICU admission (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.03-6.54; P = .04), longer hospital LOS (RR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.29-3.14; P < .002), and ICU LOS (RR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.03-3.95; P < .002) compared with patients with mild asthma, although this effect was not observed with patients with severe asthma. However, it is worth noting that because the sample size for the moderate group is smaller, this could result in larger CIs, making the significance of this finding less certain. Patients with severe asthma had shorter hospital LOS (RR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.65-1.00; P < .04). There were no differences between the groups in terms of hazard ratio of time to death, need for mechanical ventilation, or need for dialysis (Fig 4 , eTables 1 –6 ).

eTable 2.

Logistic Regression Models of ICU Admission

| Variable | Model |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma vs no asthma |

By asthma subtype |

|||||||

| GINA class |

Eosinophilic asthma |

ICS use |

||||||

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Asthma (yes vs no) | 1.58 (1.09-2.29) | .02 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| GINA class | .01 | |||||||

| Moderate vs mild | — | — | 2.60 (1.03-6.54) | .04 | — | — | — | — |

| Severe vs mild | — | — | 0.73 (0.46-1.17) | .19 | — | — | — | — |

| Eosinophilic asthma | .05 | |||||||

| High vs low | — | — | — | — | 1.17 (0.57-2.40) | .67 | — | — |

| Unknown vs low | — | — | — | — | 0.66 (0.41-1.05) | .08 | — | — |

| ICS use | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.37 (0.65-2.89) | .42 |

| Cohort: post vs pre 6/15 | 0.37 (0.28-0.48) | <.001 | 0.37 (0.28-0.47) | <.001 | 0.37 (0.28-0.48) | <.001 | 0.31 (0.14-0.67) | .003 |

| Age (per 1 y) | 1.01 (1.01-1.02) | .002 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | .003 | 1.01 (1.01-1.02) | .002 | 1.00 (0.98-1.03) | .86 |

| Female vs male | 0.57 (0.44-0.73) | <.001 | 0.57 (0.44-0.73) | <.001 | 0.57 (0.44-0.73) | <.001 | 0.46 (0.21-0.97) | .04 |

| Race | .85 | .84 | .85 | .70 | ||||

| Asian vs White | 1.10 (0.57-2.14) | .77 | 1.06 (0.54-2.06) | .87 | 1.09 (0.56-2.12) | .80 | — | .98 |

| Black vs White | 0.89 (0.65-1.20) | .44 | 0.88 (0.65-1.19) | .41 | 0.88 (0.65-1.20) | .43 | 1.55 (0.66-3.66) | .31 |

| Other vs White | 0.81 (0.51-1.30) | .39 | 0.80 (0.50-1.28) | .35 | 0.81 (0.51-1.29) | .37 | 2.03 (0.35-11.63) | .43 |

| Ethnicity | .26 | .27 | .23 | >.99 | ||||

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic | 1.79 (0.88-3.66) | .11 | 1.76 (0.86-3.60) | .12 | 1.83 (0.90-3.74) | .10 | 0.91 (0.10-8.27) | .94 |

| Unknown vs non-Hispanic | 1.20 (0.65-2.23) | .55 | 1.22 (0.66-2.27) | .52 | 1.21 (0.66-2.24) | .54 | 1.00 (0.08-13.11) | >.99 |

| Transfer vs ED | 5.38 (3.90-7.43) | <.001 | 5.37 (3.89-7.42) | <.001 | 5.36 (3.88-7.39) | <.001 | 8.74 (2.77-27.61) | <.001 |

| OSA | 1.40 (1.00-1.95) | .04 | 1.45 (1.04-2.02) | .03 | 1.40 (1.00-1.95) | .04 | 1.54 (0.68-3.48) | .30 |

| COPD | 1.39 (0.88-2.19) | .16 | 1.41 (0.90-2.23) | .14 | 1.38 (0.88-2.18) | .16 | 1.38 (0.33-5.80) | .66 |

| Hypertension | 1.02 (0.77-1.35) | .89 | 1.04 (0.78-1.37) | .81 | 1.02 (0.77-1.35) | .90 | 0.64 (0.27-1.51) | .31 |

| CAD | 0.94 (0.65-1.38) | .76 | 0.94 (0.65-1.38) | .76 | 0.93 (0.64-1.36) | .72 | 2.19 (0.73-6.62) | .16 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.54 (1.16-2.05) | .003 | 1.53 (1.15-2.04) | .004 | 1.54 (1.16-2.05) | .003 | 1.18 (0.48-2.90) | .71 |

| Obesity | 1.08 (0.84-1.40) | .55 | 1.07 (0.83-1.38) | .61 | 1.08 (0.83-1.39) | .58 | 1.42 (0.63-3.17) | .39 |

| Charlson score (per 1 point) | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | .16 | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | .16 | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | .18 | 0.99 (0.88-1.12) | .88 |

| Smoking status | .002 | .001 | .002 | .90 | ||||

| Current/former vs never | 1.33 (1.00-1.78) | .04 | 1.33 (1.00-1.78) | .05 | 1.33 (1.00-1.77) | .05 | 1.03 (0.44-2.44) | .94 |

| Unknown vs never | 1.80 (1.29-2.50) | <.001 | 1.82 (1.31-2.53) | <.001 | 1.79 (1.29-2.49) | .001 | 0.80 (0.28-2.32) | .68 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OR, odds ratio; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

eTable 3.

Logistic Regression Models of Mechanical Ventilation

| Variable | Model |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma vs no asthma |

By asthma subtype |

|||||||

| GINA class |

Eosinophilic asthma |

ICS use |

||||||

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Asthma (yes vs no) | 1.58 (1.02-2.44) | .04 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| GINA class | .003 | |||||||

| Moderate vs mild | — | — | 2.62 (0.97-7.05) | .06 | — | — | — | — |

| Severe vs mild | — | — | 0.65 (0.38-1.13) | .13 | — | — | — | — |

| Eosinophilic asthma | .09 | |||||||

| High vs low | — | — | — | — | 1.06 (0.46-2.42) | .89 | — | — |

| Unknown vs low | — | — | — | — | 0.61 (0.36-1.05) | .08 | — | — |

| ICS use | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.35 (0.52-3.49) | .53 |

| Cohort: post vs pre 6/15 | 0.34 (0.25-0.48) | <.001 | 0.35 (0.25-0.48) | <.001 | 0.35 (0.25-0.48) | <.001 | 0.23 (0.08-0.64) | .01 |

| Age (per 1 y) | 1.00 (0.99-1.02) | .34 | 1.00 (0.99-1.02) | .37 | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) | .34 | 1.02 (0.98-1.05) | .42 |

| Female vs male | 0.47 (0.34-0.65) | <.001 | 0.46 (0.34-0.64) | <.001 | 0.47 (0.34-0.64) | <.001 | 0.35 (0.14-0.89) | .03 |

| Race | .94 | .95 | .94 | .81 | ||||

| Asian vs White | 1.01 (0.43-2.37) | .98 | 0.96 (0.41-2.26) | .93 | 1.00 (0.43-2.35) | > .99 | — | .98 |

| Black vs White | 0.85 (0.59-1.24) | .40 | 0.85 (0.59-1.23) | .40 | 0.85 (0.59-1.23) | .39 | 1.70 (0.58-5.00) | .33 |

| Other vs White | 1.02 (0.59-1.76) | .95 | 0.99 (0.57-1.72) | .98 | 1.01 (0.58-1.74) | .97 | 1.09 (0.13-8.94) | .94 |

| Ethnicity | .34 | .37 | .31 | .81 | ||||

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic | 1.87 (0.80-4.36) | .15 | 1.84 (0.78-4.31) | .16 | 1.92 (0.82-4.48) | .13 | 0.71 (0.04-11.69) | .81 |

| Unknown vs non-Hispanic | 0.98 (0.48-1.99) | .95 | 0.99 (0.48-2.05) | .99 | 0.98 (0.48-2.01) | .96 | 0.40 (0.02-6.64) | .52 |

| Transfer vs ED | 7.86 (5.56-11.10) | <.001 | 7.94 (5.62-11.24) | <.001 | 7.85 (5.56-11.08) | <.001 | 42.85 (9.95-184.64) | <.001 |

| OSA | 1.35 (0.90-2.02) | .14 | 1.39 (0.93-2.07) | .11 | 1.34 (0.90-2.01) | .15 | 2.26 (0.80-6.35) | .12 |

| COPD | 0.80 (0.44-1.45) | .47 | 0.84 (0.46-1.52) | .56 | 0.80 (0.44-1.45) | .47 | 0.12 (0.01-1.09) | .06 |

| Hypertension | 0.99 (0.70-1.39) | .95 | 1.01 (0.72-1.42) | .96 | 0.99 (0.70-1.39) | .95 | 0.92 (0.30-2.79) | .89 |

| CAD | 0.78 (0.48-1.27) | .32 | 0.78 (0.48-1.26) | .31 | 0.78 (0.48-1.26) | .31 | 0.73 (0.18-2.99) | .66 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.71 (1.21-2.43) | .002 | 1.72 (1.21-2.43) | .002 | 1.72 (1.21-2.43) | .002 | 2.07 (0.70-6.09) | .19 |

| Obesity | 1.57 (1.15-2.15) | .005 | 1.56 (1.14-2.13) | .01 | 1.56 (1.14-2.14) | .01 | 1.23 (0.45-3.33) | .69 |

| Charlson score (per 1 point) | 0.97 (0.92-1.02) | .22 | 0.97 (0.92-1.02) | .20 | 0.97 (0.92-1.02) | .22 | 1.03 (0.88-1.20) | .72 |

| Smoking status | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .71 | ||||

| Current/former vs never | 1.49 (1.04-2.14) | .03 | 1.50 (1.05-2.15) | .03 | 1.49 (1.04-2.13) | .03 | 1.39 (0.49-3.96) | .54 |

| Unknown vs never | 2.84 (1.94-4.16) | <.001 | 2.89 (1.97-4.24) | <.001 | 2.84 (1.94-4.15) | <.001 | 0.79 (0.21-2.99) | .73 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OR, odds ratio; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

eTable 4.

Logistic Regression Models of Dialysis

| Variable | Model |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma vs no asthma |

By asthma subtype |

|||||||

| GINA class |

Eosinophilic asthma |

ICS use |

||||||

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Asthma (yes vs no) | 0.81 (0.46-1.43) | .47 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| GINA class | .13 | |||||||

| Moderate vs mild | — | — | 3.19 (0.98-10.33) | .05 | — | — | — | — |

| Severe vs mild | — | — | 1.22 (0.60-2.47) | .58 | — | — | — | — |

| Eosinophilic asthma | .88 | |||||||

| High vs low | — | — | — | — | 1.19 (0.39-3.63) | .76 | — | — |

| Unknown vs low | — | — | — | — | 1.19 (0.60-2.35) | .62 | — | — |

| ICS use | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.06 (0.33-3.35) | .93 |

| Cohort: post vs pre 6/15 | 0.58 (0.39-0.87) | .01 | 0.61 (0.41-0.90) | .01 | 0.59 (0.39-0.88) | .01 | 0.65 (0.18-2.31) | .51 |

| Age (per 1 y) | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | .44 | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | .47 | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | .47 | 1.00 (0.95-1.04) | .85 |

| Female vs male | 0.46 (0.31-0.68) | <.001 | 0.44 (0.30-0.65) | <.001 | 0.46 (0.31-0.67) | <.001 | 0.36 (0.11-1.21) | .10 |

| Race | .004 | .004 | .004 | .83 | ||||

| Asian vs White | 0.91 (0.26-3.19) | .89 | 0.91 (0.26-3.18) | .88 | 0.91 (0.26-3.20) | .89 | — | .98 |

| Black vs White | 2.09 (1.36-3.21) | .001 | 2.11 (1.37-3.24) | .001 | 2.09 (1.36-3.22) | .001 | 0.91 (0.24-3.41) | .89 |

| Other vs White | 2.37 (1.29-4.37) | .01 | 2.37 (1.28-4.38) | .01 | 2.36 (1.28-4.36) | .01 | 2.92 (0.25-34.59) | .40 |

| Ethnicity | .29 | .30 | .30 | .30 | ||||

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic | 1.19 (0.42-3.33) | .74 | 1.20 (0.43-3.38) | .72 | 1.20 (0.43-3.37) | .73 | — | .98 |

| Unknown vs non-Hispanic | 0.53 (0.22-1.25) | .15 | 0.53 (0.22-1.26) | .15 | 0.53 (0.22-1.27) | .15 | 0.07 (0.00-1.98) | .12 |

| Transfer vs ED | 4.57 (3.02-6.92) | <.001 | 4.72 (3.11-7.17) | <.001 | 4.60 (3.03-6.96) | <.001 | 4.51 (0.89-22.72) | .07 |

| OSA | 0.80 (0.48-1.34) | .40 | 0.80 (0.48-1.33) | .38 | 0.79 (0.47-1.32) | .36 | 0.39 (0.10-1.55) | .18 |

| COPD | 0.57 (0.27-1.24) | .16 | 0.59 (0.27-1.27) | .18 | 0.57 (0.26-1.23) | .15 | 0.62 (0.05-7.42) | .70 |

| Hypertension | 1.24 (0.82-1.87) | .31 | 1.26 (0.83-1.90) | .28 | 1.23 (0.82-1.86) | .32 | 0.55 (0.14-2.20) | .39 |

| CAD | 0.62 (0.34-1.12) | .11 | 0.61 (0.33-1.11) | .10 | 0.62 (0.34-1.12) | .11 | 0.36 (0.03-3.88) | .40 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.68 (1.12-2.52) | .01 | 1.66 (1.11-2.50) | .01 | 1.68 (1.12-2.52) | .01 | 5.76 (1.44-22.97) | .01 |

| Obesity | 1.40 (0.96-2.04) | .08 | 1.37 (0.94-1.99) | .10 | 1.40 (0.96-2.03) | .08 | 2.80 (0.73-10.84) | .13 |

| Charlson score (per 1 point) | 1.15 (1.09-1.22) | <.001 | 1.15 (1.09-1.22) | <.001 | 1.15 (1.09-1.22) | <.001 | 1.21 (1.00-1.47) | .05 |

| Smoking status | .43 | .41 | .44 | .82 | ||||

| Current/former vs Never | 0.97 (0.62-1.51) | .89 | 0.94 (0.60-1.48) | .80 | 0.97 (0.62-1.51) | .89 | 1.28 (0.32-5.04) | .72 |

| Unknown vs never | 1.30 (0.82-2.07) | .26 | 1.30 (0.82-2.06) | .27 | 1.30 (0.82-2.06) | .27 | 0.73 (0.15-3.51) | .70 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OR, odds ratio; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

eTable 5.

Negative Binomial Models of ICU Length of Stay

| Variable | Model |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma vs no asthma |

By asthma subtype |

|||||||

| GINA class |

Eosinophilic asthma |

ICS use |

||||||

| RR (95% CI) | P | RR (95% CI) | P | RR (95% CI) | P | RR (95% CI) | P | |

| Asthma (yes vs no) | 1.21 (0.89-1.64) | .22 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| GINA class | .02 | |||||||

| Moderate vs mild | — | — | 2.02 (1.03-3.95) | .04 | — | — | — | — |

| Severe vs mild | — | — | 0.89 (0.62-1.28) | .53 | — | — | — | — |

| Eosinophilic asthma | .24 | |||||||

| High vs low | — | — | — | — | 0.77 (0.45-1.32) | .34 | — | — |

| Unknown vs low | — | — | — | — | 0.73 (0.51-1.06) | .10 | — | — |

| ICS use | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.90 (0.54-1.51) | .70 |

| Cohort: post vs pre 6/15 | 0.82 (0.66-1.02) | .08 | 0.85 (0.68-1.06) | .14 | 0.82 (0.66-1.03) | .09 | 0.97 (0.52-1.79) | .92 |

| Age (per 1 y) | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | .09 | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | .08 | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | .12 | 1.01 (0.99-1.04) | .21 |

| Female vs male | 0.81 (0.65-1.02) | .08 | 0.79 (0.63-0.99) | .04 | 0.81 (0.65-1.02) | .07 | 1.26 (0.70-2.27) | .44 |

| Race | .83 | .87 | .83 | .41 | ||||

| Asian vs White | 1.00 (0.59-1.70) | >.99 | 1.00 (0.59-1.69) | >.99 | 1.00 (0.59-1.70) | >.99 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | . |

| Black vs White | 0.85 (0.66-1.11) | .23 | 0.87 (0.67-1.12) | .28 | 0.85 (0.66-1.11) | .24 | 0.84 (0.40-1.78) | .66 |

| Other vs White | 0.95 (0.63-1.44) | .82 | 0.94 (0.63-1.42) | .77 | 0.95 (0.63-1.44) | .82 | 0.29 (0.07-1.29) | .11 |

| Ethnicity | .17 | .16 | .18 | .36 | ||||

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic | 1.53 (0.86-2.73) | .15 | 1.55 (0.87-2.74) | .13 | 1.50 (0.84-2.68) | .17 | 2.36 (0.60-9.17) | .22 |

| Unknown vs non-Hispanic | 0.80 (0.51-1.25) | .33 | 0.81 (0.52-1.26) | .35 | 0.79 (0.51-1.24) | .30 | 1.09 (0.17-6.86) | .93 |

| Transfer vs ED | 2.04 (1.58-2.65) | <.001 | 2.06 (1.60-2.66) | <.001 | 2.03 (1.57-2.63) | <.001 | 5.50 (2.79-10.87) | <.001 |

| OSA | 0.84 (0.64-1.09) | .19 | 0.87 (0.67-1.14) | .32 | 0.85 (0.65-1.12) | .25 | 1.04 (0.61-1.75) | .89 |

| COPD | 0.69 (0.46-1.01) | .06 | 0.71 (0.48-1.04) | .08 | 0.69 (0.47-1.02) | .06 | 0.49 (0.18-1.37) | .17 |

| Hypertension | 0.82 (0.65-1.03) | .09 | 0.84 (0.67-1.07) | .16 | 0.82 (0.65-1.04) | .10 | 0.47 (0.24-0.94) | .03 |

| CAD | 0.92 (0.66-1.27) | .61 | 0.94 (0.68-1.30) | .70 | 0.93 (0.67-1.28) | .65 | 0.84 (0.33-2.14) | .71 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.04 (0.83-1.31) | .74 | 1.06 (0.84-1.33) | .63 | 1.04 (0.82-1.30) | .76 | 1.35 (0.69-2.64) | .37 |

| Obesity | 1.29 (1.01-1.65) | .04 | 1.23 (0.97-1.57) | .09 | 1.29 (1.01-1.64) | .04 | 1.45 (0.72-2.93) | .30 |

| Charlson score (per 1 point) | 1.05 (1.01-1.09) | .02 | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) | .08 | 1.05 (1.00-1.09) | .03 | 1.15 (1.04-1.27) | .01 |

| Smoking status | .19 | .19 | .21 | .59 | ||||

| Current/former vs never | 1.21 (0.94-1.56) | .15 | 1.20 (0.93-1.54) | .16 | 1.20 (0.93-1.55) | .15 | 1.44 (0.72-2.86) | .30 |

| Unknown vs never | 1.24 (0.92-1.66) | .15 | 1.25 (0.93-1.67) | .14 | 1.23 (0.92-1.65) | .17 | 1.13 (0.48-2.64) | .78 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; ICU, intensive care unit; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; RR, risk ratio.

Figure 4.

Impact of GINA step, asthma phenotype, and ICS use on outcomes. All models adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, transfer status, OSA, COPD, hypertension, CAD, diabetes mellitus, obesity, CCI, and smoking status. Cox proportional hazards models used for death; logistic regression used for ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and dialysis; negative binomial regression used for ICU and hospital LOS. CAD, coronary artery disease; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

eTable 1.

Cox Proportional Hazards Models of Time to Death

| Variable | Model |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma vs no asthma |

By asthma subtype |

|||||||

| GINA class |

Eosinophilic asthma |

ICS use |

||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Asthma (yes vs no) | 1.53 (1.01-2.33) | .04 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| GINA class | .04 | |||||||

| Moderate vs mild | — | — | 1.70 (0.68-4.24) | .25 | — | — | — | — |

| Severe vs mild | — | — | 0.71 (0.41-1.22) | .21 | — | — | — | — |

| Eosinophilic asthma | .19 | |||||||

| High vs low | — | — | — | — | 0.92 (0.39-2.16) | .85 | — | — |

| Unknown vs low | — | — | — | — | 0.65 (0.39-1.08) | .09 | — | — |

| ICS use | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.44 (0.56-3.73) | .45 |

| Cohort: post vs pre 6/15 | 0.66 (0.49-0.90) | .01 | 0.67 (0.49-0.90) | .01 | 0.66 (0.49-0.90) | .01 | 0.37 (0.12-1.13) | .08 |

| Age (per 1 y) | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | <.001 | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | <.001 | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | <.001 | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | .14 |

| Female vs male | 0.67 (0.50-0.90) | .01 | 0.68 (0.51-0.90) | .01 | 0.68 (0.51-0.90) | .01 | 0.33 (0.14-0.79) | .01 |

| Race | .07 | .07 | .07 | .02 | ||||

| Asian vs White | 0.44 (0.14-1.41) | .17 | 0.43 (0.14-1.38) | .16 | 0.44 (0.14-1.41) | .17 | — | >.99 |

| Black vs White | 0.85 (0.59-1.23) | .39 | 0.86 (0.60-1.23) | .41 | 0.85 (0.59-1.22) | .38 | 1.43 (0.46-4.48) | .54 |

| Other vs White | 1.63 (1.05-2.55) | .03 | 1.63 (1.04-2.55) | .03 | 1.63 (1.04-2.54) | .03 | 18.34 (2.83-118.93) | .002 |

| Ethnicity | .12 | .11 | .12 | .08 | ||||

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic | 1.32 (0.55-3.12) | .53 | 1.31 (0.55-3.10) | .55 | 1.31 (0.55-3.12) | .54 | — | .99 |

| Unknown vs non-Hispanic | 0.54 (0.28-1.04) | .06 | 0.53 (0.27-1.03) | .06 | 0.53 (0.28-1.03) | .06 | 0.06 (0.01-0.70) | .02 |

| Transfer vs ED | 2.22 (1.59-3.11) | <.001 | 2.22 (1.58-3.11) | <.001 | 2.21 (1.58-3.09) | <.001 | 18.72 (4.08-85.94) | <.001 |

| OSA | 0.73 (0.48-1.11) | .14 | 0.76 (0.50-1.16) | .21 | 0.74 (0.49-1.13) | .16 | 0.58 (0.21-1.58) | .28 |

| COPD | 1.16 (0.76-1.77) | .49 | 1.19 (0.78-1.82) | .43 | 1.17 (0.76-1.79) | .47 | 0.68 (0.16-2.80) | .59 |

| Hypertension | 0.72 (0.53-0.96) | .03 | 0.73 (0.54-0.98) | .04 | 0.72 (0.53-0.97) | .03 | 0.76 (0.26-2.18) | .60 |

| CAD | 0.84 (0.57-1.25) | .39 | 0.84 (0.56-1.24) | .38 | 0.84 (0.56-1.24) | .38 | 1.77 (0.36-8.65) | .48 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.02 (0.74-1.40) | .92 | 1.01 (0.74-1.39) | .93 | 1.01 (0.74-1.39) | .95 | 4.43 (1.45-13.54) | .01 |

| Obesity | 1.06 (0.80-1.41) | .68 | 1.06 (0.79-1.41) | .70 | 1.06 (0.80-1.41) | .69 | 0.24 (0.08-0.71) | .01 |

| Charlson score (per 1 point) | 1.12 (1.07-1.16) | <.001 | 1.12 (1.07-1.16) | <.001 | 1.12 (1.07-1.16) | <.001 | 1.37 (1.18-1.60) | <.001 |

| Smoking status | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .53 | ||||

| Current/former vs never | 1.63 (1.12-2.38) | .01 | 1.63 (1.12-2.37) | .01 | 1.63 (1.12-2.36) | .01 | 1.89 (0.62-5.74) | .26 |

| Unknown vs never | 2.98 (2.06-4.30) | <.001 | 3.03 (2.09-4.39) | <.001 | 2.97 (2.05-4.29) | <.001 | 1.35 (0.45-4.01) | .59 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; HR, hazard ratio; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

eTable 6.

Negative Binomial Models of Hospital Length of Stay

| Variable | Model |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma vs no asthma |

By asthma subtype |

|||||||

| GINA class |

Eosinophilic asthma |

ICS use |

||||||

| RR (95% CI) | P | RR (95% CI) | P | RR (95% CI) | P | RR (95% CI) | P | |

| Asthma (yes vs no) | 1.30 (1.09-1.55) | .003 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| GINA class | <.001 | |||||||

| Moderate vs mild | — | — | 2.01 (1.29-3.14) | .002 | — | — | — | — |

| Severe vs mild | — | — | 0.80 (0.65-1.00) | .04 | — | — | — | — |

| Eosinophilic asthma | .001 | |||||||

| High vs low | — | — | — | — | 0.85 (0.61-1.19) | .34 | — | — |

| Unknown vs low | — | — | — | — | 0.69 (0.55-0.86) | .001 | — | — |

| ICS use | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.93 (0.68-1.29) | .68 |

| Cohort: post vs pre 6/15 | 0.57 (0.50-0.64) | <.001 | 0.58 (0.52-0.65) | <.001 | 0.57 (0.51-0.64) | <.001 | 0.52 (0.37-0.74) | <.001 |

| Age (per 1 y) | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | .07 | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | .09 | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | .05 | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | .83 |

| Female vs male | 0.77 (0.69-0.86) | <.001 | 0.76 (0.68-0.85) | <.001 | 0.77 (0.68-0.86) | <.001 | 1.15 (0.82-1.62) | .41 |

| Race | .17 | .17 | .17 | .55 | ||||

| Asian vs White | 0.97 (0.72-1.30) | .85 | 0.96 (0.71-1.28) | .76 | 0.97 (0.73-1.30) | .85 | 0.49 (0.17-1.44) | .20 |

| Black vs White | 0.91 (0.79-1.05) | .19 | 0.92 (0.80-1.05) | .22 | 0.91 (0.79-1.04) | .18 | 1.04 (0.69-1.57) | .85 |

| Other vs White | 0.84 (0.67-1.04) | .10 | 0.83 (0.67-1.03) | .09 | 0.83 (0.67-1.03) | .10 | 0.76 (0.33-1.77) | .52 |

| Ethnicity | .22 | .23 | .23 | .53 | ||||

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic | 1.32 (0.96-1.81) | .09 | 1.30 (0.95-1.78) | .10 | 1.31 (0.95-1.79) | .10 | 1.10 (0.44-2.75) | .83 |

| Unknown vs non-Hispanic | 1.05 (0.80-1.38) | .72 | 1.07 (0.81-1.40) | .64 | 1.05 (0.80-1.38) | .73 | 0.57 (0.19-1.72) | .32 |

| Transfer vs ED | 2.58 (2.22-3.00) | <.001 | 2.56 (2.21-2.98) | <.001 | 2.57 (2.21-2.99) | <.001 | 4.05 (2.48-6.62) | <.001 |

| OSA | 1.02 (0.88-1.19) | .78 | 1.05 (0.91-1.22) | .50 | 1.03 (0.88-1.19) | .74 | 1.05 (0.74-1.49) | .79 |

| COPD | 0.96 (0.77-1.21) | .75 | 0.99 (0.79-1.23) | .91 | 0.97 (0.77-1.21) | .76 | 0.74 (0.36-1.50) | .40 |

| Hypertension | 0.98 (0.86-1.11) | .77 | 1.00 (0.88-1.14) | >.99 | 0.99 (0.87-1.12) | .85 | 0.70 (0.47-1.03) | .07 |

| CAD | 0.91 (0.76-1.08) | .27 | 0.92 (0.77-1.09) | .33 | 0.90 (0.76-1.08) | .26 | 0.92 (0.53-1.58) | .75 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.36 (1.19-1.56) | <.001 | 1.37 (1.20-1.56) | <.001 | 1.36 (1.19-1.55) | <.001 | 1.44 (0.95-2.18) | .09 |

| Obesity | 0.96 (0.85-1.08) | .49 | 0.93 (0.83-1.05) | .25 | 0.95 (0.85-1.07) | .43 | 1.20 (0.83-1.73) | .34 |

| Charlson score (per 1 point) | 1.02 (1.00-1.04) | .09 | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | .26 | 1.02 (1.00-1.04) | .11 | 1.08 (1.02-1.15) | .01 |

| Smoking status | .005 | .01 | .01 | .09 | ||||

| Current/former vs never | 1.24 (1.09-1.41) | .001 | 1.23 (1.08-1.40) | .002 | 1.23 (1.08-1.39) | .002 | 1.39 (0.95-2.02) | .09 |

| Unknown vs never | 1.02 (0.87-1.20) | .77 | 1.03 (0.88-1.21) | .71 | 1.02 (0.87-1.20) | .80 | 0.77 (0.46-1.26) | .29 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; ICU, intensive care unit; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; RR, risk ratio.

Grouping patients with asthma with COVID-19 by eosinophilic vs non-eosinophilic asthma, there were no differences between the 2 groups in terms of mechanical ventilation, ICU admission, need for dialysis, and hospital or ICU LOS. ICS use did not have a favorable impact on hospital LOS, ICU LOS, death rate, ICU admission, need for mechanical ventilation, or dialysis (Fig 4, eTables 1–6).

Differences in Outcomes of Patients With Asthma With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Based on Timing of Illness

When further stratified by timing of illness in the pandemic (group 2 vs group 1), those admitted in the second half of the year had substantially improved outcomes compared with those in group 1, including need for ICU admission (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.2-0.9; P = .02) and need for mechanical ventilation (OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.10-0.76; P = .01), hospital LOS (RR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.50-0.57; P < .001), and ICU LOS (RR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.77-0.92; P < .001). There were no differences between the 2 groups in terms of hazard ratio of death or need for dialysis. Dexamethasone use was considered for both groups given the impact of this treatment on COVID-19–related outcomes. Patients in group 1 rarely received dexamethasone, and its use did not differ between patients with asthma and patients without asthma (2% of patients with asthma vs 3% of patients without asthma, P = .48). However, in group 2, dexamethasone use was much higher with increased use in the patients with asthma (55% vs 41%, P = .02).

Discussion

In a single-center cohort study, we evaluated the impact of asthma on outcomes for patients requiring admission for COVID-19 in the first year of the pandemic. Asthma is a disease characterized by airway hyperresponsiveness in the setting of inflammatory mediators and cytokines which, when coupled with a clinical syndrome of systemic inflammation as in COVID-19, is thought to lead to marked epithelial barrier dysfunction, pulmonary injury, and exacerbation of underlying disease.1 Interestingly, after adjusting for risk factors, our data found that patients with asthma had a higher likelihood of severe COVID-19–related outcomes, including ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, longer hospital LOS, and death, though effect sizes were relatively small. There are sex disparities in asthma outcomes with female patients having a higher risk of poor outcomes from asthma, including a higher risk of asthma-related mortality, and thus adjusting for sex is critical.19 Our data indicated an important effect of female sex and older age on COVID-19–related outcomes, which is the opposite of what has been found in COVID-19 infection alone where age and male sex have been shown repeatedly to be significant risk factors for poor outcomes in COVID-19.2 Our study highlights the important finding that patients with asthma are at a modestly increased risk of more severe COVID-19 after adjusting for known risk factors. Literature on this topic is inconsistent, some of which suggests no increased risk of severe outcomes in admitted patients with asthma.2 , 5 , 7 , 19 , 20 The inconsistencies may stem from a variety of causes such as smaller sample sizes of patients with asthma from single-center institutional data (n = 53, n = 23) or as a result of the low prevalence of asthma in the population of patients infected with COVID-19 in some countries.5 , 21 Furthermore, primary end points were not uniform between the studies with the utilization of a variety of outcomes, including intubation,2 transfer to ICU,22 time to discharge (with pooling of discharge home or death as a singular outcome),20 and LOS or a combination of these outcomes as surrogates for severe COVID-19. Moreover, results of univariate analysis do not consider the confounding effects of comorbidities that are established risk factors associated with more severe disease. Our results are consistent with prior reports of prolonged duration of intubation23 and worse clinical outcomes in large nationwide cohort studies.8 , 24 However, a meta-analysis of asthma outcomes in 57 studies, which ranged from large retrospective studies to small case series with a wide sample size range (from n = 8 to n = 119,528), did not show higher risks of ICU admission, requiring mechanical ventilation, and death from COVID-19 in those with asthma compared with those without asthma.25

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease with a broad spectrum of different clinical phenotypes owing to distinct differences in pathophysiology. Several mechanisms have been postulated to explain how allergic asthma and TH2 asthma can be protective in COVID-19 compared with non-allergic or obesity-related asthma. At the cellular level, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 expression is down-regulated in nasal epithelial cells in the presence of allergic sensitization and inversely correlated with type 2 biomarkers.26 As such, TH2-high asthma and low interleukin-6 levels are postulated as being associated with reduced risk whereas TH2-low asthma and high interleukin-6 levels are thought to be associated with increased risk.4 , 17, 27 Eosinophilic asthma is associated with allergic sensitization and TH2-dominant inflammatory response,26 and similar mechanisms of receptor down-regulation may explain the decrease in risk observed in these patients.28 Conversely, patients with non-allergic asthma demonstrate different cytokine profiles, including a predominance of TH1-mediated neutrophil and mast cell response,29 which may help explain more severe COVID-19 outcomes in non-allergic asthma patients. In fact, an analysis using UK Biobank data showed that severe COVID-19 was driven by non-allergic asthma patients, whereas allergic asthma had no statistically relevant association with severe COVID-19.24 Although patients with eosinophilic asthma in our cohort (based on historical AEC > 300 cells/μL) did not have substantially different risk of outcomes, a recent study using a lower threshold of AEC more than 150 cells/μL found that preexisting eosinophilia protects against hospital admission in patients with asthma who develop COVID-19.30 Even more interesting is their finding that development of peripheral eosinophilia while hospitalized for COVID-19 was protective against mortality.30 This suggests that in the future the heterogeneity of asthma phenotypes must be taken into consideration when assessing risk of severe disease with COVID-19.

The impact of asthma severity on COVID-19 outcomes is also unclear. In a large UK study that utilized an approach similar to ours by stratifying asthma severity by prescribed medications before admission, outcomes including hazard ratio of death were worse among patients with severe asthma.31 In our cohort, patients with moderate asthma had worse outcomes whereas patients with severe asthma did not, despite having a higher prevalence of comorbidities. One possible explanation for this is that a higher proportion of patients with severe asthma were characterized with having eosinophilic asthma phenotypes (44% compared with 25% in mild asthma), which may be a contributing factor. We postulate that the severe asthma cohort was receiving more intensive asthma treatment, which may have contributed to improvements in COVID-19–related outcomes. This cohort was receiving biologics and higher doses of ICSs that would have resulted in decreased baseline inflammation, and this may have had protective effects. Given the small sample size of our patients with moderate (n = 29) and severe (n = 49) asthma, more research is needed to fully elucidate the impact of asthma severity and baseline treatment on COVID-19 outcomes. ICS use has been thought to cause a reduction in angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in a dose-response manner,4 , 32 and previous studies have shown that ICS use was not associated with increased risk of hospitalization or mortality owing to COVID-19.33 ICS use was not associated with longer LOS in our cohort and did not change outcomes or mortality. Patients with asthma should be encouraged to adhere to ICS-based therapies.33, 34, 35

Our study has potential limitations, including a single-center cohort; however, our health system is a referral center for tertiary care, and thus, we received a large number of transfers from hospitals around the state of Michigan, which resulted in enrichment of the cohort with more socially and racially diverse populations. Patients were transferred at different points in their course of illness; however, there was equal representation of these patients in the asthma and non-asthma cohorts. Furthermore, we adjusted for transfer status in each multivariate model, which also accounts for level of care at presentation because most patients arrived mechanically ventilated. Another key limitation are the missing data needed to accurately phenotype our asthma cohort. Prior quantitative IgE and fraction of exhaled nitric oxide levels were missing on most of the cohort of patients with asthma which precluded our ability to fully characterize asthma endotypes. In addition, many patients with asthma were missing lung function measurements before admission, and therefore, baseline lung function impairments and the impact of lung function on COVID-19–related outcomes could not be determined in our cohort. We also were not able to address the impact of poor asthma control on outcomes for hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Future studies looking at the impact of poor asthma control, including asthma control test scores, symptom control, and exacerbation frequency, will be important to address this question. Our study focused on the outcomes of patients with asthma already hospitalized with COVID-19, leaving unanswered questions about whether asthma is a risk factor for acquiring COVID-19 in the community and whether these patients are more likely to be hospitalized than the general population. Although our data prove useful for prognostication for hospitalized patients, many patients with COVID-19 are not admitted to the hospital, and selecting only hospitalized patient can induce bias, exaggerating the effect of risk factors on poor outcomes, such as ICU admission or death.

The finding that outcomes from COVID-19 improved over the course of the year is indicative of advances in our knowledge regarding the disease and improvements in care. The improvement in these outcomes likely reflects improvements in COVID-19 treatments over time. For example, dexamethasone was used more often in group 2 than group 1 (42% vs 3%; P < .01). Our data indicate that patients with asthma were more likely to receive dexamethasone in the hospital despite the fact that COVID-19 is known to cause parenchymal disease and generally does not cause asthma exacerbations.36 Use of systemic corticosteroids is common in the management of hospitalized patients with asthma, and thus, the use of dexamethasone may be more liberal in this population and not follow the strict recommendations guiding the use of dexamethasone for COVID-19 pneumonia.

Our study reveals the importance of accounting for sex, age, and disease heterogeneity when determining the impact of COVID-19 on asthma outcomes. The lack of consensus on this topic would be resolved by harmonization of definitions of disease characteristics and outcomes. In general, the data that are available indicate that currently available asthma therapies do not result in negative consequences in the presence of COVID-19 infection, and therefore, patients should be reassured that adhering with asthma therapies is the most appropriate course of action at this time. Further research is required to parse out the specific asthma features that are associated with increased risk, and our data suggest that it is premature to conclude that asthma is not associated with an increased risk of poor outcomes with COVID-19.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2022.03.017.

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors report no conflict of interest with the submitted work.

Funding: Dr Troost was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences for the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (UL1TR002240).

References

- 1.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broadhurst R, Peterson R, Wisnivesky JP, Federman A, Zimmer SM, Sharma S, et al. Asthma in COVID-19 hospitalizations: an overestimated risk factor? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(12):1645–1648. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-613RL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aveyard P, Gao M, Lindson N, Hartmann-Boyce J, Watkinson P, Young D, et al. Association between pre-existing respiratory disease and its treatment, and severe COVID-19: a population cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(8):909–923. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00095-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lombardi C, Roca E, Bigni B, Cottini M, Passalacqua G. Clinical course and outcomes of patients with asthma hospitalized for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2pneumonia: a single-center, retrospective study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125(6):707–709. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chhiba KD, Patel GB, Vu THT, Chen MM, Guo A, Kudlaty E, et al. Prevalence and characterization of asthma in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(2):307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.010. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, Yuan YD, Yang YB, Yan YQ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020;75(7):1730–1741. doi: 10.1111/all.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang JM, Koh HY, Moon SY, Yoo IK, Ha EK, You S, et al. Allergic disorders and susceptibility to and severity of COVID-19: a nationwide cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(4):790–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dagens A, Sigfrid L, Cai E, Lipworth S, Cheng V, Harris E, et al. Scope, quality, and inclusivity of clinical guidelines produced early in the covid-19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ. 2020;369:m1936. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collaborative Group RECOVERY, Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castillo JR, Peters SP, Busse WW. Asthma exacerbations: pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(4):918–927. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2020. Available at: https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/. Accessed October 12, 2021

- 13.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, O'Halloran A, Cummings C, Holstein R, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 - COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barth O, Anderson B. Vol. 11. Lifecourse Epidemiology and Genomics Division; 2018. Michigan BRFSS Surveillance Brief: Asthma among Michigan Adults Prevalence, Health Conditions, & Health Behaviors; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh S, Das S, Mondal R, Abdullah S, Sultana S, Singh S, et al. A review on the effect of COVID-19 in type 2 asthma and its management. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;91 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, Chan L, Matthews KS, Melamed ML, et al. Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1436–1447. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pennington E, Yaqoob ZJ, Al-Kindi SG, Zein J. Trends in asthma mortality in the United States: 1999-2015. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(12):1575–1577. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1844LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovinsky-Desir S, Deshpande DR, De A, Murray L, Stingone JA, Chan A, et al. Asthma among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and related outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(5):1027–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.026. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Xu S, Yu M, Wang K, Tao Y, Zhou Y, et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(1):110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grandbastien M, Piotin A, Godet J, Abessolo-Amougou I, Ederlé C, Enache I, et al. SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in hospitalized asthmatic patients did not induce severe exacerbation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(8):2600–2607. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahdavinia M, Foster KJ, Jauregui E, Moore D, Adnan D, Andy-Nweye AB, et al. Asthma prolongs intubation in COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(7):2388–2391. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu Z, Hasegawa K, Ma B, Fujiogi M, Camargo CA, Liang L. Association of asthma and its genetic predisposition with the risk of severe COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(2):327–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.001. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sunjaya AP, Allida SM, Di Tanna GL, Jenkins C. Asthma and risk of infection, hospitalisation, ICU admission and mortality from COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis [e-pub ahead of print]. J Asthma. 10.1080/02770903.2021. Accessed October 10, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Walford HH, Doherty TA. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic asthma: a US perspective. J Asthma Allergy. 2014;7:53–65. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S39119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maes T, Bracke K, Brusselle GG. Reply to Lipworth. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(6):900–902. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2129LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho KS, Howell D, Rogers L, Narasimhan B, Verma H, Steiger D. The relationship between asthma, eosinophilia, and outcomes in coronavirus disease 2019 infection. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;127(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amin K, Lúdvíksdóttir D, Janson C, Nettelbladt O, Björnsson E, Roomans GM, et al. Inflammation and structural changes in the airways of patients with atopic and nonatopic asthma. BHR Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(6):2295–2301. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.9912001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferastraoaru D, Hudes G, Jerschow E, Jariwala S, Karagic M, de Vos G, et al. Eosinophilia in asthma patients is protective against severe COVID-19 illness. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(3):1152–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.12.045. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bloom CI, Drake TM, Docherty AB, Lipworth BJ, Johnston SL, Nguyen-Van-Tan JS, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes in patients with underlying respiratory conditions admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a national, multicentre prospective cohort study using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol UK. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(7):699–711. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00013-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters MC, Sajuthi S, Deford P, Christenson S, Rios CL, Montgomery MT, et al. COVID-19-related genes in sputum cells in asthma. Relationship to demographic features and corticosteroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):83–90. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0821OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halpin DMG, Singh D, Hadfield RM. Inhaled corticosteroids and COVID-19: a systematic review and clinical perspective. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01009-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipworth B, Kuo CR, Lipworth S, Chan R. Inhaled corticosteroids and COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(6):899–900. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-2000LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipworth B, Chan R, Kuo CR. Use of inhaled corticosteroids in asthma and coronavirus disease 2019: keep calm and carry on. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125(5):503–504. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramakrishnan RK, Al Heialy S, Hamid Q. Implications of preexisting asthma on COVID-19 pathogenesis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2021;320(5):L880–L891. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00547.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]