Abstract

Radiation-induced lung injury (RILI) is commonly observed in patients receiving radiotherapy, and clinical prevention and treatment remain difficult. We investigated the effect and mechanism of nicaraven for mitigating RILI. C57BL/6 N mice (12-week-old) were treated daily with 6 Gy X-ray thoracic radiation for 5 days in sequences (cumulative dose of 30 Gy), and nicaraven (50 mg/kg) or placebo was injected intraperitoneally in 10 min after each radiation exposure. Mice were sacrificed and lung tissues were collected for experimental assessments at the next day (acute phase) or 100 days (chronic phase) after the last radiation exposure. Of the acute phase, immunohistochemical analysis of lung tissues showed that radiation significantly induced DNA damage of the lung cells, increased the number of Sca-1+ stem cells, and induced the recruitment of CD11c+, F4/80+ and CD206+ inflammatory cells. However, all these changes in the irradiated lungs were effectively mitigated by nicaraven administration. Western blot analysis showed that nicaraven administration effectively attenuated the radiation-induced upregulation of NF-κB, TGF-β, and pSmad2 in lungs. Of the chronic phase, nicaraven administration effectively attenuated the radiation-induced enhancement of α-SMA expression and collagen deposition in lungs. In conclusion we find that nicaraven can effectively mitigate RILI by downregulating NF-κB and TGF-β/pSmad2 pathways to suppress the inflammatory response in the irradiated lungs.

Keywords: radiation, DNA damage, lung injury, inflammatory response

INTRODUCTION

Radiotherapy is used for cancer treatment, but exposure to high doses of ionizing radiation also damages the normal tissue cells [1, 2]. Radiation-induced lung injury (RILI), including acute pneumonitis and chronic pulmonary fibrosis, is frequently observed in patients receiving thoracic radiotherapy. It is estimated that RILI occurs in 13–37% of lung cancer patients undergoing curative radiotherapy, which may limit the dose of radiotherapy and affect the quality of life [3]. Currently, the pathogenesis of RILI has not yet been fully understood, and there is no effective drug in the clinic.

It is known that high dose ionizing radiation leads to DNA double-strand breaks [4]. DNA damage contributes to oxidative stress, vascular damage, and inflammation. Pneumonitis develops within hours or days after high dose irradiation exposure, and is accompanied by an increased capillary permeability and the accumulation of inflammatory cells in lungs [5–7]. The recruited inflammatory cells secret profibrotic cytokines to activate the resident fibroblasts, which finally leads to an excessive collagen production and deposition in the interstitial space of lungs [8–10].

NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B) is an important regulator of inflammatory response. The NF-κB signaling pathway is known to be activated following radiation exposure [11]. TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway also deeply involves in RILI [12, 13]. Thoracic irradiation causes a continuous increase of TGF-β1 in plasma, which is a predictor of radiation pneumonitis after radiotherapy [14]. The activation of TGF-β induces the conversion of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, the elevated expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and the synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen [15, 16]. Therefore, targeting these pathways can be a potential strategy for mitigating RILI.

Nicaraven, a hydroxyl free radical scavenger [17], has previously been demonstrated to protect against the radiation-induced cell death [18, 19]. We have also recently found that the administration of nicaraven to mice soon after high dose γ-ray exposure attenuates the radiation-induced injury of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, which is more likely associated with anti-inflammatory effect rather than radical scavenging [20, 21]. Moreover, nicaraven can reduce the radiation-induced recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils into lungs [22]. Therefore, we speculate that nicaraven may effectively mitigate RILI, at least partly by inhibiting inflammatory response through NF-κB and TGF-β/Smad signaling pathways [23].

By exposing the lungs of adult mice to 30 Gy X-ray, we investigated the effect and mechanism of nicaraven for mitigating RILI. Our results showed that nicaraven administration significantly reduced the DNA damage of lung tissue (stem) cells, inhibited the radiation-induced recruitment of CD11c+, F4/80+ and CD206+ inflammatory cells in lungs at the acute phase, and also mitigated the radiation-induced enhancement of α-SMA and partly decreased the fibrotic area in the irradiated lungs at the chronic phase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male C57BL/6 N mice (12-week-old; CLEA, Japan) were used for study. Mice were housed in pathogen-free room with a controlled environment under a 12 h light–dark cycle, with free access to food and water. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nagasaki University (No.1608251335-12). All animal procedures were performed in accordance with institutional and national guidelines.

Thoracic radiation exposure and nicaraven administration

The RILI model was established as previously described [24]. Briefly, mice were treated daily with 6 Gy X-ray thoracic radiation for 5 days in sequences (cumulative dose of 30 Gy) at a dose rate of 1.0084 Gy/min (200 kV, 15 mA, 5 mm Al filtration, ISOVOLT TITAN320, General Electric Company, United States) (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Nicaraven (50 mg/kg; n = 6, IR + N group) or placebo (n = 6, IR group) was injected intraperitoneally to mice within 10 min after each radiation exposure, and we continued the daily injections for 5 additional days after the last radiation exposure (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Age-matched mice without radiation exposure were used as control (n = 6, CON group). The body weights of mice were recorded once a week. We sacrificed the mice the next day (Acute phase) or the 100th day (Chronic phase) after the last exposure (Supplementary Fig. 1A). At the end of follow-up, mice were euthanized under general anesthesia by severing the aorta to remove the blood. Lung tissues were excised and weighed, and then collected for experimental evaluations as follows.

Immunohistochemical analysis

The DNA damage in lung tissue (stem) cells was detected by immunohistochemical analysis. Briefly, lungs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and paraffin sections of 6-μm-thick were deparaffinized and rehydrated. After antigen retrieval and blocking, sections were incubated with rabbit anti-mouse γ-H2AX antibody (1:400 dilution, Abcam) and rat anti-mouse Sca-1 antibody (1:200 dilution, Abcam) overnight at 4°C, and followed by the appropriate fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies at 25°C for 60 min. The nuclei were stained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1:1000 diution, Life technologies). The positive staining was examined under fluorescence microscope (FV10CW3, OLYMPUS).

The recruitment of inflammatory cells was detected by immunostaining with mouse anti-mouse CD11c antibody (1:150 dilution, Abcam), rat anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (1:100 dilution, Abcam), goat anti-mouse CD206 antibody (1:200 dilution, R&D Systems) overnight at 4°C, and followed by the appropriate Alexa fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:400 dilution, Invitrogen), respectively. The nuclei were stained with DAPI. The positive staining was examined under fluorescence microscope (FV10CW3, OLYMPUS).

For quantitative analysis, we counted the positively stained cells in 12 images from two separated independent sections of each lung tissue sample. The number of positively stained cells in each lung tissue sample was normalized by the number of nuclei, and the average value per field (image) from each lung tissue sample was used for statistical analysis.

Masson’s trichrome staining

To detect the fibrotic change in lungs, Masson’s trichrome staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The stained sections were mounted and then imaged using a microscope (Biorevo BZ-9000; Keyence Japan, Osaka, Japan). The fibrotic area was quantified by measuring the positively stained area using the Image-Pro Plus software (version 5.1.2, Media Cybernetics Inc, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and expressed as a percentage of the total area. The average value from 12 images randomly selected from two separated slides for each lung tissue sample was used for statistical analysis.

Western blot

Western blot was performed as previously described [25]. Briefly, lung tissue sample was homogenized using Multi-beads shocker® and added to the T-PER reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) consisting of proteinase and dephosphorylation inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total tissue protein purified from lungs were separated by SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred to 0.22-μm PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). After blocking, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against NF-kB p65 (1:500 dilution, Abcam), IκBα (1:1000 dilution, CST), TGF-β (1:1000 dilution, Abcam), pSmad2 (1:1000 dilution, Abcam), α-Tubulin (1:1000 dilution, CST), or GAPDH (1:1000 dilution, Abcam), respectively; and followed by the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dako). The expression was visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Thermo Scientific). Semiquantitative analysis was done using ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Statistical analysis

All the values were presented as mean ± SD. For comparison of multiple sets of data, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test (Dr. SPSS II, Chicago, IL) was used. For comparison of two sets of data, an unpaired two-tailed t-test was used. All analysis was carried out with the SPSS19.0 statistical software (IBM SPSS Co., USA). A p-value less than 0.05 was accepted as significant.

RESULTS

Nicaraven significantly reduced the radiation-induced DNA damage of lung tissue (stem) cells at the acute phase

All mice survived after treatments and during the follow-up period. The body weights of the mice were decreased temporarily soon after radiation exposure, but tended to increase approximately 10 days after radiation exposure. Although the body weights of mice between IR group and IR + N group were not significantly different, they were significantly lower than the age-matched non-irradiated mice in the CON group (p < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 1B). Moreover, the lung weights of mice were not significantly different among all groups at either the acute phase or the chronic phase (Supplementary Fig. 1C).

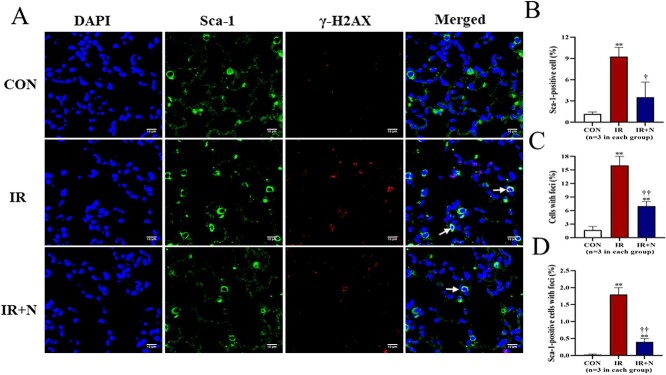

Immunohistochemistry was performed to evaluate the expression of Sca-1 and γ-H2AX in lung tissue cells at the acute phase (Fig. 1A). Compared to CON group, the number of Sca-1+ stem cells was significantly increased in the IR group (9.27 ± 1.30% vs 1.17 ± 0.29%, p < 0.01; Fig. 1B). However, the increased number of Sca-1+ stem cells in irradiated lungs was significantly attenuated by nicaraven administration (3.53 ± 2.15%, p < 0.05 vs IR group; Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

The DNA damage of lung tissue cells at the acute phase after treatments. (A) Representative confocal images show the expression of Sca-1 and γ-H2AX in lung tissue cells. Quantitative data on the number of Sca-1+ stem cells (B), the total cells with γ-H2AX foci formation (C), and the Sca-1+ stem cells with γ-H2AX foci formation (D, Arrows) are shown. Scale bars: 10 μm. The nuclei were stained with DAPI. Data are represented as means ± SD. **p < 0.01 vs CON group, †p < 0.05, ††p < 0.01 vs IR group. CON: Control, IR: Radiation, IR + N: Radiation+Nicaraven.

The formation of γ-H2AX foci in nuclei of lung tissue cells was dramatically increased in the IR group, but was mildly changed in the IR + N group (Fig. 1A). Quantitative data also indicated that the percentage of γ-H2AX-positive cells was significantly less in the IR + N group than the IR group (16.27 ± 2.05% vs 7.13 ± 0.91%, p < 0.01; Fig. 1C). Moreover, we tried to evaluate the formation of γ-H2AX foci in Sca-1+ stem cells. Interestingly, the number of Sca-1+ stem cells with γ-H2AX foci was more effectively decreased in the IR + N group compared to the IR group (1.93 ± 0.51% vs 0.35 ± 0.19%, p < 0.01; Fig. 1D). These results indicate that nicaraven administration can reduce the radiation-induced DNA damage in lung tissue cells, especially in these Sca-1+ stem cells.

Nicaraven effectively decreased the radiation-induced recruitment of inflammatory cells into lungs

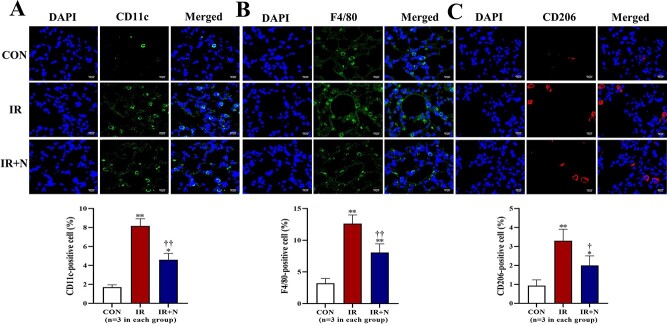

According to our previous studies [20, 21], nicaraven protects tissue (stem) cells against radiation injury by inhibiting inflammatory response. Therefore, immunohistochemical analysis was performed to detect the inflammatory cells in lungs. The number of CD11c + monocytes and F4/80+ macrophages was significantly higher in the IR group than the CON group (p < 0.01, Fig. 2A and B). However, nicaraven administration significantly reduced the recruitment of CD11c + monocytes (8.23 ± 0.75% vs 4.61 ± 0.65%, p < 0.01; Fig. 2A) and F4/80+ macrophages (12.63 ± 1.36% vs 8.07 ± 1.38%, p < 0.01; Fig. 2B) into irradiated lungs. Similarly, the number of M2 macrophages (CD206+) was also significantly higher in irradiated lungs than that of non-irradiated lungs (p < 0.01, Fig. 2C). Interestingly, nicaraven administration significantly decreased the CD206+ macrophages in irradiated lungs (3.3 ± 0.61% vs 2.1 ± 0.53%, p < 0.05; Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical detection of inflammatory cells in lungs at the acute phase after treatments. Representative confocal images (upper) and quantitative data (lower) show the CD11c+ cells (A), F4/80+ cells (B), and CD206+ cells (C) in lungs. Scale bars: 10 μm. The nuclei were stained with DAPI. Data are represented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs CON group, †p < 0.05, ††p < 0.01 vs IR group. CON: Control, IR: Radiation, IR + N: Radiation+Nicaraven.

Nicaraven significantly attenuated the radiation-induced upregulation of NF-κB and TGF-β in lungs

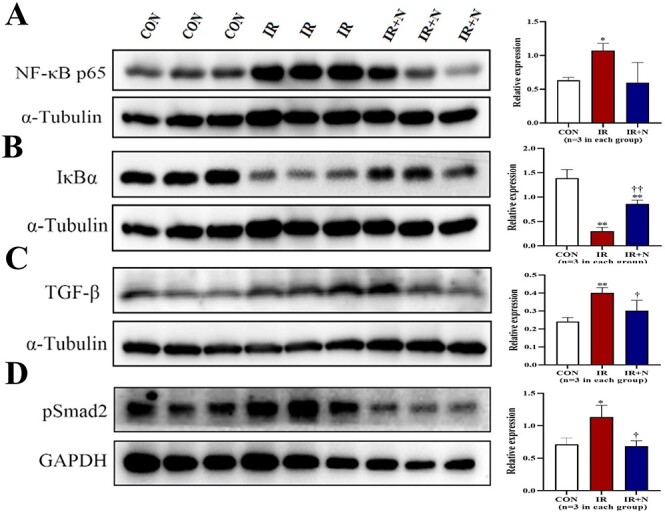

To further understand the molecular mechanism of nicaraven on mitigating RILI, we investigated the expression of NF-κB and IκBα (inhibitor of NF-κB) in lungs at the acute phase. Compared to the CON group, the IR group showed a significant enhancement on the expression of NF-κB (p < 0.05, Fig. 3A). However, the enhanced expression of NF-κB in irradiated lungs was effectively attenuated by nicaraven administration (p = 0.09, Fig. 3A). In contrast, the expression of total IκBα was significantly decreased in irradiated lungs (p < 0.01 vs CON group, Fig. 3B), which was effectively attenuated by nicaraven administration (p < 0.01 vs IR group, Fig. 3B). We also investigated the expression of TGF-β and pSmad2 in irradiated lungs at the acute phase (Fig. 3C and D). The irradiated lungs showed a significant upregulation of TGF-β and pSmad2 (p < 0.05 vs CON group, Fig. 3C and D), but was effectively attenuated by nicaraven administration (p < 0.05 vs IR group, Fig. 3C and D).

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis on the expression of NF-κB, IκBα, TGF-β, and pSmad2 in lungs. Representative blots (left) and quantitative data (right) on the expression of NF-κB p65 (A), IκBα (B), TGF-β (C), pSmad2 (D) in lungs are shown. Data are normalized to α-Tubulin or GAPDH, and represented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs CON group, †p < 0.05, ††p < 0.01 vs IR group. CON: Control, IR: Radiation, IR + N: Radiation+Nicaraven.

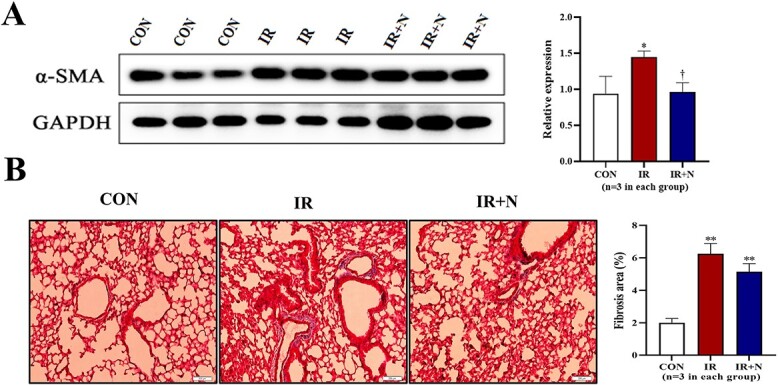

Nicaraven clearly attenuated the radiation-induced enhancement of α-SMA and partially reduced the fibrotic area in irradiated lungs at the chronic phase

We further investigated the expression of α-SMA and collagen deposition in irradiated lungs at the chronic phase. Western blot indicated an enhanced expression of α-SMA in the irradiated lungs (p < 0.05 vs CON group, Fig. 4A), but the enhanced expression of α-SMA in irradiated lungs was completely attenuated by nicaraven administration (Fig. 4A). Similarly, Masson’s trichrome staining showed that the fibrotic area in lungs was significantly higher in the IR group than the CON group (p < 0.05, Fig. 4B). However, nicaraven administration tended to only partially reduce the fibrotic area in irradiated lungs (6.24 ± 0.64% vs 5.14 ± 0.51%, p = 0.08; Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

The fibrotic changes in lungs at the chronic phase after treatments. (A) Representative blots (left) and quantitative data (right) on the expression of α-SMA in lungs are shown. (B) Representative images (left) and quantitative data (right) of Masson‘s trichrome staining on the fibrotic area in lungs are shown. Scale bars: 200 μm. Data are represented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs CON group, †p < 0.05 vs IR group. CON: Control, IR: Radiation, IR + N: Radiation+Nicaraven.

DISCUSSION

This study was proposed to investigate the potential effect and underlying mechanism of nicaraven on mitigating RILI. Our experimental data revealed that nicaraven administration not only reduced the DNA damage (γ-H2AX foci formation) of lung tissue (stem) cells, but also inhibited the recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils into irradiated lungs at the acute phase. Nicaraven administration also significantly attenuated the radiation-induced enhancement of TGF-β and NF-κB, and partially reduced the fibrotic area in irradiated lungs at the chronic phase.

Nicaraven is known as a powerful radical scavenger that effectively protects various tissues and organs against injuries, particularly for ischemia–reperfusion injury in the brain [26–28]. Considering the well-recognized antioxidative property and the potential anti-inflammatory effect of nicaraven, we evaluated the probable role of nicaraven on mitigating RILI.

The exposure to high levels of ionizing radiation leads to DNA double-strand breaks, which elicit cell death or stochastic change [4]. Stem cells are known to play critical role in tissue homeostasis, while ionizing radiation exposure can disrupt the tissue homeostasis. Alveolar epithelium is composed of two cell types: Type I cells account for 95% of the gas exchange surface area, and type II cells can transform into type I cells and have the ability to repair alveoli. Sca-1-positive cells are identified as a population of alveolar type II cells with progenitor cell properties [29]. It has also been demonstrated that the proliferation of Sca-1-positive cells increases during the alveolar epithelial repair phase [29, 30]. In this study, the number of Sca-1-positive cells were exactly increased in irradiated lungs at the acute phase, suggesting the probable role of Sca-1-positive cells for repairing the injured lungs after high dose irradiation. Nicaraven administration showed to reduce the DNA damage of lung tissue cells, especially in these Sca-1-positive cells at the acute phase, which indirectly indicates the protective effect of nicaraven on RILI.

Various chemokines/cytokines are known to be increased in organs/tissues exposed to high dose irradiation, which in turn induces the recruitment of inflammatory cells at the acute phase. The recruited inflammatory cells play a key role in the pathogenesis of RILI [31, 32], because inflammatory cascade is known to promote fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition [33]. In responding to high dose radiation exposure, the recruitment of monocytes/immune cells (CD11c+) into lung tissue plays critical pathophysiological role on RILI. Among the recruited monocytes/immune cells, macrophages (F4/80+) represent an important profibrogenic initiator/mediator, but M2 macrophages (CD206+) are thought to be an anti-inflammatory phenotype of macrophages. In this study, we found that the recruitment of monocytes/immune cells, including the M2 macrophages was significantly increased in the irradiated lungs. Consistent with previous reports [22, 34], the administration of nicaraven inhibited significantly the recruitment of monocytes into the irradiated lungs. It will be better to understand the precise role of especial subpopulation of inflammatory cells, such as the M2 macrophages in lungs using genetically modified animals. However, the purpose of this study was designed to examine the potency of nicaraven for attenuating RILI through an anti-inflammatory mechanism, we used a wild-type mice rather than the genetically modified mice for experiments.

TGF-β is one of the most critical master regulators on promoting acute inflammation and chronic fibrosis in lungs [12–16]. Previous studies have demonstrated that radiation exposure activates TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway to initiate the inflammatory response, induce the proliferation and activation of fibroblasts, and enhance the synthesis of matrix proteins [35, 36]. Therefore, the inhibition of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway may effectively mitigate RILI. In this study, nicaraven administration exactly downregulated the expression of TGF-β and pSmad2 in irradiated lungs at the acute phase.

NF-κB has emerged as a ubiquitous factor involved in the regulation of numerous critical processes, including immune [37], inflammation response [38], cell apoptosis [39], and cell proliferation [40]. While in an inactivated state, NF-κB is located in the cytosol complexed with the inhibitory protein IκBα. Radiation exposure can activate NF-κB signaling pathway. Radiation exposure activates the kinase IKK, which in turn phosphorylates IκBα and results in ubiquitin-dependent degradation [11, 38, 40]. Dysregulation of NF-κB signaling can lead to inflammation, autoimmune disease and cancer [41]. In this study, nicaraven administration effectively downregulated the expression of NF-κB, suggesting the involvement of NF-κB pathway in the protective effect of nicaraven to RILI.

Generally, although nicaraven administration only tended to partially reduce the fibrotic area in the irradiated lungs, many other parameters, such as the expression of α-SMA was more sensitively and clearly changed. As the activated fibroblasts (α-SMA+) are generally thought to be the predominant source of collagen-producing cells, the inhibition on α-SMA expression in irradiated lungs by nicaraven administration suggested the probable benefit of nicaraven for attenuating the development of fibrotic change in irradiated lungs at the chronic phase. In summary, nicaraven administration effectively protected the RILI, likely by suppressing inflammatory response through the NF-κB and TGF-β/Smad signaling pathways. Nicaraven could be a potential drug for mitigating RILI.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Agency for Medical Research and Development under Grant Number JP20lm0203081. The funder played no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Contributor Information

Yong Xu, Department of Stem Cell Biology, Atomic Bomb Disease Institute, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan; Department of Stem Cell Biology, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, 1-12-4 Sakamoto, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan.

Da Zhai, Department of Stem Cell Biology, Atomic Bomb Disease Institute, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan; Department of Stem Cell Biology, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, 1-12-4 Sakamoto, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan.

Shinji Goto, Department of Stem Cell Biology, Atomic Bomb Disease Institute, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan; Department of Stem Cell Biology, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, 1-12-4 Sakamoto, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan.

Xu Zhang, Department of Stem Cell Biology, Atomic Bomb Disease Institute, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan; Department of Stem Cell Biology, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, 1-12-4 Sakamoto, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan.

Keiichi Jingu, Department of Radiation Oncology, Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University, Sendai 980-8574, Japan.

Tao-Sheng Li, Department of Stem Cell Biology, Atomic Bomb Disease Institute, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan; Department of Stem Cell Biology, Nagasaki University Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, 1-12-4 Sakamoto, Nagasaki 852-8523, Japan.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Bentzen SM. Preventing or reducing late side effects of radiation therapy: radiobiology meets molecular pathology. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:702–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McBride WH, Schaue D. Radiation-induced tissue damage and response. J Pathol 2020;250:647–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rodrigues G, Lock M, D'Souza D et al. Prediction of radiation pneumonitis by dose volume histogram parameters in lung cancer--a systematic review. Radiother Oncol 2004;71:127–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang L, Snyder AR, Morgan WF. Radiation-induced genomic instability and its implications for radiation carcinogenesis. Oncogene 2003;22:5848–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hanania AN, Mainwaring W, Ghebre YT et al. Radiation-induced lung injury: assessment and management. Chest 2019;156:150–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giuranno L, Ient J, De Ruysscher D et al. Radiation-induced lung injury (RILI). Front Oncol 2019;9:877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim H, Park SH, Han SY et al. LXA4-FPR2 signaling regulates radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis via crosstalk with TGF-β/Smad signaling. Cell Death Dis 2020;11:653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jin H, Yoo Y, Kim Y et al. Radiation-induced lung fibrosis: preclinical animal models and therapeutic strategies. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kainthola A, Haritwal T, Tiwari M et al. Immunological aspect of radiation-induced pneumonitis, current treatment strategies, and future prospects. Front Immunol 2017;8:506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Im J, Lawrence J, Seelig D et al. FoxM1-dependent RAD51 and BRCA2 signaling protects idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis fibroblasts from radiation-induced cell death. Cell Death Dis 2018;9:584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Devary Y, Rosette C, DiDonato JA et al. NF-kappa B activation by ultraviolet light not dependent on a nuclear signal. Science 1993;261:1442–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Madani I, De Ruyck K, Goeminne H et al. Predicting risk of radiation-induced lung injury. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:864–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fleckenstein K, Gauter-Fleckenstein B, Jackson IL et al. Using biological markers to predict risk of radiation injury. Semin Radiat Oncol 2007;17:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anscher MS, Kong FM, Andrews K et al. Plasma transforming growth factor beta1 as a predictor of radiation pneumonitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998;41:1029–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singh V, Torricelli AA, Nayeb-Hashemi N et al. Mouse strain variation in SMA(+) myofibroblast development after corneal injury. Exp Eye Res 2013;115:27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tatler AL, Jenkins G. TGF-β activation and lung fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2012;9:130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akimoto T. Quantitative analysis of the kinetic constant of the reaction of N,N'-propylenedini-cotinamide with the hydroxyl radical using dimethyl sulfoxide and deduction of its structure in chloroform. Chem Pharm Bull(Tokyo) 2000;48:467–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mori Y, Takashima H, Seo H et al. Experimental studies on Nicaraven as radioprotector--free radical scavenging effect and the inhibition of the cellular injury. Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi 1993;53:704–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Watanabe M, Akiyama N, Sekine H et al. Inhibition of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase as a protective effect of nicaraven in ionizing radiation- and ara-C-induced cell death. Anticancer Res 2006;26:3421–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zingarelli B, Scott GS, Hake P et al. Effects of nicaraven on nitric oxide-related pathways and in shock and inflammation. Shock 2000;13:126–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Masana Y, Yoshimine T, Fujita T et al. Reaction of microglial cells and macrophages after cortical incision in rats: effect of a synthesized free radical scavenger, (+/−)-N,N'-propylenedinicotinamide (AVS). Neurosci Res 1995;23:217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yan C, Luo L, Urata Y et al. Nicaraven reduces cancer metastasis to irradiated lungs by decreasing CCL8 and macrophage recruitment. Cancer Lett 2018;418:204–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lin H, Wu X, Yang Y et al. Nicaraven inhibits TNFα-induced endothelial activation and infla-mmation through suppressing NF-κB signaling pathway. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2021;99:803–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Citrin DE, Shankavaram U, Horton JA et al. Role of type II pneumocyte senescence in radiation-induced lung fibrosis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:1474–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Doi H, Kitajima Y, Luo L et al. Potency of umbilical cord blood- and Wharton's jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells for scarless wound healing. Sci Rep 2016;6:18844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Asano T, Johshita H, Koide T et al. Amelioration of ischaemic cerebral oedema by a free radical scavenger, AVS: 1,2-bis(nicotinamido)-propane. An experimental study using a regional ischaemia model in cats. Neurol Res 1984;6:163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Asano T, Takakura K, Sano K et al. Effects of a hydroxyl radical scavenger on delayed ischemic neurological deficits following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: results of a multicenter, placebo-controlled double-blind trial. J Neurosurg 1996;84:792–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Imperatore C, Germanò A, d'Avella D et al. Effects of the radical scavenger AVS on behavioral and BBB changes after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Life Sci 2000;66:779–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu Y, Kumar VS, Zhang W et al. Activation of type II cells into regenerative stem cell antigen-1(+) cells during alveolar repair. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2015;53:113–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu Y, Sadikot RT, Adami GR et al. FoxM1 mediates the progenitor function of type II epithelial cells in repairing alveolar injury induced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Exp Med 2011;208:1473–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnston CJ, Williams JP, Elder A et al. Inflammatory cell recruitment following thoracic irradiation. Exp Lung Res 2004;30:369–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meziani L, Deutsch E, Mondini M. Macrophages in radiation injury: a new therapeutic target. Onco Targets Ther 2018;7:e1494488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boothe DL, Coplowitz S, Greenwood E et al. Transforming growth factor β-1 (TGF-β1) is a serum biomarker of radiation induced fibrosis in patients treated with intracavitary accelerated partial breast irradiation: preliminary results of a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013;87:1030–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang X, Moriwaki T, Kawabata T et al. Nicaraven attenuates postoperative systemic Inflam-matory responses-induced tumor metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol 2020;27:1068–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meng XM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. TGF-β: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2016;12:325–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Samarakoon R, Overstreet JM, Higgins PJ. TGF-β signaling in tissue fibrosis: redox controls, target genes and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Signal 2013;25:264–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baeuerle PA, Henkel T. Function and activation of NF-kappa B in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol 1994;12:141–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1066–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bours V, Bonizzi G, Bentires-Alj M et al. NF-kappaB activation in response to toxical and therapeutical agents: role in inflammation and cancer treatment. Toxicology 2000;153:27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Karin M, Cao Y, Greten FR et al. NF-kappaB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat Rev Cancer 2002;2:301–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu H, Lin L, Zhang Z et al. Targeting NF-κB pathway for the therapy of diseases: mechanism and clinical study. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020;5:209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.