Abstract

Objective:

Social skills difficulties are commonly reported by parents and teachers of school age children with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Investigations of social skills of young children with NF1 are scarce. This study aimed to characterize the emergence of social skills challenges beginning in early childhood, examine social skills longitudinally into school age, and explore interrelations with ADHD symptomatology and cognitive functioning among children with NF1 cross-sectionally and longitudinally.

Method:

Three samples of children with NF1 and their parents participated: 1) early childhood (n=50; ages 3–6; M=3.96, SD=1.05), 2) school age (n=40; ages 9–13; M=10.90, SD=1.59) and 3) both early childhood and school age (n=25). Parent-reported social skills (Social Skills Rating System; Social Skills Improvement System), parent-reported ADHD symptomatology (Conners Parent Rating Scales – Revised; Conners 3rd Edition) and cognitive abilities (Differential Ability Scales-Second Edition) were evaluated.

Results:

Parental ratings of social skills were relatively stable throughout childhood. Ratings of social skills at the end of early childhood significantly predicted school age social skills. Parental ratings of ADHD symptomatology showed significant negative relations with social skills. Early childhood inattentive symptoms predicted school age social skills ratings. Cognitive functioning was not significantly related to social skills.

Conclusions:

Parent-reported social skills difficulties are evident during early childhood. This work adds to the literature by describing the frequency and stability of social skills challenges in early childhood and in the school age period in NF1. Research about interventions to support social skills when difficulties are present is needed.

Keywords: Neurofibromatosis type 1, NF1, social skills, longitudinal

Social functioning difficulties are commonly reported for school age children with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) based on parent, teacher, and peer-reports,1–5 but little is known about these difficulties in young children with NF1 or about the trajectory of social functioning across development. NF1 is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder caused by a mutation of the NF1-gene on chromosome 17q11.2 responsible for encoding the tumor suppressor protein, neurofibromin.6 About half of cases are familial and half represent de novo NF1 mutations. NF1 has a prevalence rate of 1 in 3,500 births7 and includes medical, cognitive6 and psychosocial difficulties.7 Using peer-reports, children with NF1 are more sensitive, more socially isolated and show less leadership behavior, are chosen as a best friend less often, have fewer reciprocated friendships, and are less liked in comparison to classroom peers.5 The majority of previous research about social functioning, using parent-rated questionnaire measures, demonstrates that school age children with NF1 display poorer social skills compared to normative data1 and unaffected controls,2–4 display more social problems compared to unaffected controls3,4,7–10 and normative data,10,11 and have less social competence compared to unaffected controls.10,12

Relations of social functioning with attention problems have been explored in school age children with NF1. Attention deficits are recognized as a central part of the cognitive phenotype of individuals with NF1 with a prevalence of 30–50% meeting DSM criteria for ADHD.13 Significant correlations between attention problems and social skills have been found for school age children with NF1.1 Further, children with NF1 and co-morbid ADHD show poorer social skills than children with NF1 only and children with NF1 and co-morbid learning deficits.1,13 However, attention difficulties among young children are not consistently indicated in young children with NF1;14 they may be subtle and difficult to detect.15

Investigations of associations between cognitive and social functioning in children with NF1 have yielded inconsistent findings. Most individuals with NF1 show overall intellectual functioning in the low average to average range,16 with lowering in verbal and performance IQ relative to same-aged peers.4,9,17 Some studies of social skills, social problems and social competence have not found significant correlations with intellectual functioning in children with NF1.1,8,12 Other studies, however, have provided evidence for such relations.11,18 A study of young children with NF1, whose sample overlaps with the current study, observed a trend for stronger social skills in children with stronger intellectual functioning.19

In this paper, parent-reported social skills of children with NF1 are examined in both early childhood and the school age years separately and also among a subsample of children seen at both time points. To date, there have been limited studies about social skills among young children and there has been no examination of social skills longitudinally in children with NF1. Studies of early childhood have found parental ratings of social skills to be comparable to contrast groups, but used broad behavioral screening questionnaire measures rather than measures focused specifically on social skills.14,18,19 This study primarily aims to examine the developmental trajectory of social skills in children with NF1 cross-sectionally and longitudinally. The emergence of social skills difficulties, the frequency of social skills difficulties and the persistence of these difficulties over time is investigated using a measure focused on assessment of social skills. Given that social deficits are apparent for school age children, teenagers20 and adults with NF121,22 and given the progressive nature of NF1,23 social skills difficulties in NF1 may emerge over time, highlighting the importance of a longitudinal approach. Overall, it is hypothesized that parents of young children (EC Subsample) and school age children (SA Subsample) with NF1 will report poorer social skills in comparison to normative data. Using a subset of participants who were followed longitudinally into the school age years (Longitudinal Subsample), it is expected that parent-reported school age social skills will be poorer than in early childhood, there will be higher frequency of social skills difficulties in the school age years than in early childhood, and social skills will be significantly correlated over time.

Previous research has emphasized that attention and cognitive difficulties are present during early childhood for children with NF1.14,24 Literature with children without NF1 points to links between attention25 and cognitive26 functioning with social functioning. The secondary aims of this study are to 1) replicate previous school age findings of relations between parent-reported attention difficulties and parent-reported social skills with school-age children and extend the description of social skills to younger children with NF1; 2) examine relations between cognitive functioning and parent-reported social skills in NF1 during both developmental periods given inconsistent findings in the literature; and 3) examine the predictive value of early childhood ADHD symptomatology and cognitive functioning for later parent-reported social skills. Parent-reported ADHD symptomatology and cognitive functioning are expected to be significantly correlated with parent-reported social skills cross-sectionally during early childhood (EC Subsample), school age (SA Subsample), and longitudinally across time (Longitudinal Subsample).

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 65 children with a confirmed clinical diagnosis of NF1 and their parents. This study has a mixed-design with cross-sectional and longitudinal approaches. The sample consists of three somewhat overlapping subsamples: 1) children with NF1 seen between 1 and 4 times yearly beginning between ages 3 and 6 (we refer to this as the “Early Childhood” timepoint, though it does extend into the early school-age years); EC; n = 50); this approach resulted in 22 participants assessed at 3-years old, 30 participants at 4-years old, 33 participants at 5-years old and 28 participants assessed at 6-years old; 2) children with NF1 seen once during school age (SA; ages 9–13; n = 40) with 14 participants age 9-years old, 10 participants age 10-years old, 4 participants age 11-years old, 6 participants age 12-years old and 6 participants age 13-years old; and 3) a subset of children with NF1 who were seen during both early childhood (T1) and during school age (T2; n = 25), referred to as the longitudinal sample. The first assessment time point during early childhood (Visit 1) was used as the T1 timepoint for longitudinal analyses. Mean time between T1 Visit 1 and T2 for the longitudinal sample was 6.28 years (SD = 0.76). Table 1 describes the participant demographic information for each subsample.

Table 1.

Participant demographic data for the early childhood sample, school age sample and a subset of longitudinal participants seen at both timepoints

| Cross-Sectional | Longitudinal Subset | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Childhood | School Age | T1 | T2 | |

| Variable | n = 50 | n = 40 | n = 25 | |

| Mean Age (SD) | 3.96 (1.05) | 10.9 (1.59) | 4.12 (1.09) | 10.40 (1.35) |

| Sex (Frequency; %) | ||||

| Females | 19 (38) | 18 (45) | 11 (44) | |

| Males | 31 (62) | 22 (55) | 14 (56) | |

| NF Etiology (Frequency; %) | Familial: 19 (38) de novo: 31 (62) |

Familial: 13 (32.5) de novo: 27 (67.5) |

Familial: 7 (28) de novo: 18 (72) |

|

| Race/Ethnicity (Frequency; %) | ||||

| Caucasian | 37 (74) | 33 (82.5) | 20 (80) | |

| African-American | 5 (10) | 4 (10) | 3 (12) | |

| Latino | 5 (10) | - | - | |

| Asian | 1 (2) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4) | |

| Mixed Ethnicity | 2 (4) | 2 (5) | 1 (4) | |

| Hollingshead SES Index Mean (SD) | 41.92 (14.86) | 46.13 (12.43) | 43.04 (14.26) | 44.99 (10.82) |

Note: Cross-sectional refers to analyses of one timepoint. Longitudinal subset refers to analyses across early childhood and school age within the same participants. T1: early childhood visit for longitudinal subset. T2: school age visit for longitudinal subset. SES = Socioeconomic status. SD: Standard Deviation.

Procedure

Recruitment took place at several midwestern Neurofibromatosis Clinics and through flier distribution through NF organizations. For the school age study, previous research participants who had consented to be informed of future studies in the lab were mailed a study flier or called. Inclusion criteria included (1) a confirmed clinical diagnosis of NF1 by a physician, (2) age 3–8 years (for early childhood study) and/or 9–13 years (school age study), and (3) first and main language spoken in the home is English. Early on in the study, enrollment of 7 and 8-year olds was discontinued; due to the small sample size at these ages, participants ages 7 and 8 years old were excluded from this investigation. Although no participants were excluded for the following reasons, exclusion criteria included (1) any comorbid conditions not commonly associated with NF1 and (2) a significant surgery within the past six months. Consent forms and questionnaire measures were mailed to participants for parental completion prior to the assessment appointment. Informed consent was obtained. Each participant was administered an age-appropriate neuropsychological battery. This study was conducted with approval by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The Social Skills Rating System (SSRS)27 and the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS)28 are parent report questionnaires used to assess social skills during early childhood and school age, respectively. The SSIS is a revised version of the SSRS and has a moderate to strong correlation with the SSRS. Both measures demonstrate adequate reliability and validity. Internal consistency estimates are as follows: SSRS Preschool α=.90; SSRS Elementary α=.87; SSIS Elementary α=.95; SSIS Secondary α=96. The SSRS Parent Elementary form Social Skills scale is moderately correlated (.58) with the Child Behavior Checklist Social Competence scale. The SSIS is moderately to strongly correlated (.85 for preschool; 52 for elementary) with the Behavior Assessment System for Children – Second Edition and moderately with the Vineland-II (.44). The SSRS Preschool form was used for children ages 3–5 years and the Elementary form for children in K-1st grades. The SSIS Elementary form was used for children grades K-6th grade and the Secondary form for children grades 7th- 8th. The Social Skills scale standard score (Mean (M) = 100, Standard Deviation (SD) = 15) on each measure was used to assess the presence of positive social behaviors. Higher scores represent more positive social behaviors. Standard scores of <85 are classified as a difficulty and ≥85 are classified as not a difficulty.

The Conners Parent Rating Scales – Revised Short Form (CPRS-R)29 and Conners 3rd Edition - Parent Short Form (Conners-3)30 are parent report questionnaire measures that were used to assess attention difficulties in early childhood and school age, respectively. Both measures have demonstrated good reliability and validity. The CPRS-R Hyperactivity and Cognitive Problems/Inattention scales T-scores (M = 50, SD = 10) were used to examine ADHD symptomatology during early childhood. The Conners-3 Hyperactivity/Impulsivity and Inattention scales T-scores were used during the school age years. Higher scores on both measures represent more ADHD symptomatology.

The Differential Ability Scales-Second Edition (DAS-II)31 was used to assess cognitive abilities. The DAS-II demonstrates excellent reliability and validity. The DAS-II Early Years version was used during early childhood and the School Age version was used during school age. Standard scores (M = 100, SD = 15) for an overall General Conceptual Ability (GCA) as well as verbal, nonverbal and spatial reasoning were examined. The DAS-II GCA is highly correlated with the commonly administered Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence –3rd Edition (WPPSI-III) Full Scale IQ (.87) and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – 4th Edition (WISC-IV) Full Scale IQ (.84). Higher scores represent higher cognitive abilities.

The Four-Factor Index of Social Status (Hollingshead, unpublished data, 1975) was used as a measure of socioeconomic status (SES) for each participant at both time points. Education and occupational levels of parents, marital status and sex contribute to an overall SES index score. Educational levels are rated on a 7-point scale, with a score of 1 indicating less than seventh grade to a score of 7 indicating graduate or professional training. Occupational levels are rated on a 9-point scale, with a score of 1 indicating menial service workers to a score of 9 indicating higher executives and major professionals. Each educational code is multiplied by 3 and each occupational code is multiplied by 5, then summed and averaged to compute an SES index score, ranging from 8 to 66. Higher SES index scores indicate higher overall socioeconomic status. Criticisms have arisen related to this method of calculating SES,32 however, many studies have used this method and demonstrated reliability and high correlation with other methods of SES calculations.33

Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS for Windows, version 25 was used for data analysis. False discovery rate (FDR) correction was used to control for multiple comparisons (q value of < .05 indicated significance). Analyses of one timepoint are referred to as cross-sectional examinations (i.e., EC Subsample and SA Subsample). Analyses across early childhood and school age within the same participants are referred to as longitudinal examinations (i.e., Longitudinal Subsample). Spearman’s rho correlations were used where specified. Attrition analyses were conducted to compare early childhood children who returned for a visit at T2 and those who did not return for a visit at T2, to illustrate the representativeness of the longitudinal sample and the validity of the longitudinal findings, using independent samples t-tests and chi-square tests of independence Attrition within early childhood was also examined comparing early childhood participants who had a visit at age 6 years and those who did not, using independent samples t-tests and chi-square tests of independence. Group differences among the subsamples were examined using independent samples t-tests and correlations. One sample t-tests were used to compare social skills to the normative mean. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Fisher’s least significance difference (LSD) post-hoc tests were used to examine differences between ages during early childhood. Longitudinal examinations were explored using a paired samples t-test, correlations and exact McNemar’s tests.

RESULTS

Attrition

When examining attrition from early childhood to school age, no significant differences were found for sex (χ2(1, N = 50) = .76, q = .44), SES (t(48) = .53, q = .59, d = 0.15), NF classification (χ2(1, N = 50) = 2.12, q = .35) or GCA (t(48) = .92, q = .44, d = 0.26) among individuals with a visit at SA (Longitudinal Subsample; n = 25) and those who did not have a visit at SA (n = 25). Notably, social skills were significantly higher for those who did return at SA (t(48) = −3.05, q = .014, d = 0.86). CPRS-R Hyperactivity during early childhood was significantly lower for those who did return at SA compared to those who did not return at SA (t(34.4) = 3.35, q = .014, d = 0.95), suggesting those with more hyperactivity difficulties were more likely to drop out and thus, this investigation could be examining a less impaired group of individuals with NF1. There was no significant difference for CPRS-R Cognitive Problems/Inattention (t(48) = 1.14, q = .44, d = 0.32). As a note, while there were no differences in the representation of familial and de novo NF etiology classification within the EC Subsample and SA Subsample, there was a significant difference in the Longitudinal Subsample with more participants with de novo NF etiology classification.

For analysis of stability during early childhood (within EC Subsample), 18 individuals with a visit at age 3 or 4 years and a visit at age 6 years were examined. When examining attrition within early childhood, no significant differences were found for sex (χ2(1, N = 50) = 1.25, q = .38), SES (t(48) = −1.12, q = .38, d = 0.35), NF classification (χ2(1, N = 50) = 1.25, q = .38), GCA (t(48) = .29, q = .81, d = 0.11), social skills (t(48) = 0.24, q = .81, d = 0.19) or ADHD symptomatology (CPRS-R Hyperactivity: t(47.77) = 2.00, q = .20, d = 0.607; Cognitive Problems/Inattention: t(48) = 1.95, q = .20, d = 0.604) among young children included in this analysis and those who were excluded as they did not have a visit at age 6 years.

Group Differences in Social Skills

No group differences in social skills were found by sex (EC: t(48) = −1.71, q = .26, d = 0.51; SA: t(38) = −1.84, q = .26, d = 0.59; T1 SSRS: t(23) = −0.78, q = .53, d = 0.31; T2 SSIS: t(23) = −2.70, q = .13, d = 1.12). No significant differences in social skills were evident for familial compared to de novo NF etiology classification (EC: t(48) = −1.52, q = .27, d = 0.43; SA: t(15.64) = −0.86, q = .53, d = 0.32; T1 SSRS: t(23) = 0.62, q = .54, d = 0.26; T2 SSIS: t(23) = −0.93, q = .53, d = 0.37). Social skills were not significantly related to SES (EC: rho(50) = .29, q = .13; SA: rho(40) = −.03, q = .53; T1 SSRS: rho(25) = .25, q = .26; T2 SSIS: rho(25) = −.006, q = .53).

Emergence and Stability of Social Skills Challenges During Early Childhood

Young children with NF1 had significantly lower social skills compared to the normative mean (Table 2; M = 100, SD = 15; t(49) = −4.41, q = .002, d = 0.67) and children ages 3, 4 and 5 years had significantly lower social skills compared to the normative mean (M = 100, SD = 15; Age 3: M = 81.73, SD = 13.46, t(21) = −6.37, q = .002, d = 1.28; Age 4: M = 89.97, SD = 18.23, t(29) = −3.01, q = .007, d = 0.60; Age 5: M = 90.67, SD = 18.22, t(32) = −2.94, q = .007; d = 0.56). Children age 6 years did not significantly differ from the normative mean (M = 96.96, SD = 17.42, t(27) = −0.92, q = .37, d = 0.19). Early childhood social skills were significantly correlated with age (rho = .44, q = .002). There was a statistically significant difference between age groups (F(3, 109) = 3.23, q = .028). Post hoc tests revealed that the children with NF1 age 3 years had statistically significantly more impaired social skills compared to children with NF1 age 6 years (q = .004, d = 0.98). Social skills at ages 3 or 4 years were strongly significantly correlated with social skills at age 6 years (rho(18) = .71, q = .002).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of study measures for children in early childhood (n=50), school age (n = 40) and longitudinal participants (n=25)

| Early Childhood | School Age | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Sectional | Longitudinal (T1) | Cross-Sectional | Longitudinal (T2) | ||||||

| (n = 50) | (n = 25) | (n = 40) | (n = 25) | ||||||

| Scale | M | SD | M | SD | Scale | M | SD | M | SD |

| Social Functioning | Social Functioning | ||||||||

| SSRS | 89.24 | 17.26 | 96.24 | 16.58 | SSIS | 91.85 | 15.25 | 92.76 | 13.51 |

| ADHD Symptomatology | ADHD Symptomatology | ||||||||

| CPRS-R | Conners-3 | ||||||||

| Hyperactivity | 54.04 | 10.94 | 49.32 | 6.05 | Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | 61.33 | 13.98 | 59.00 | 11.81 |

| Cognitive Problems/Inattention | 56.84 | 12.16 | 54.88 | 10.91 | Inattention | 67.23 | 13.04 | 66.08 | 12.75 |

| Cognitive Functioning | Cognitive Functioning | ||||||||

| DAS-II | DAS-II | ||||||||

| GCA | 93.02 | 11.87 | 94.56 | 9.87 | GCA | 93.90 | 13.24 | 94.60 | 15.09 |

| Verbal | 96.00 | 12.8 | 98.76 | 11.22 | Verbal | 98.65 | 13.20 | 99.72 | 14.74 |

| Nonverbal | 93.54 | 12.59 | 93.88 | 11.99 | Nonverbal | 94.08 | 15.56 | 93.80 | 17.95 |

| Spatial | 92.5 | 12.59 | 94.10 | 9.91 | Spatial | 91.82 | 11.36 | 92.76 | 10.89 |

Note: Cross-sectional refers to analyses of one timepoint. Longitudinal refers to analyses of the subset of participants seen both in early childhood and school age. T1: early childhood visit for longitudinal subset. T2: school age visit for longitudinal subset. M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation; SSRS: Social Skills Rating System; SSIS: Social Skills Improvement System; CPRS-R: Conners Parent Rating Scales – Revised; DAS-II; Differential Ability Scales-Second Edition; GCA: General Conceptual Ability.

Emergence and Stability of Social Skills Challenges During School Age and Longitudinally Across Time

School age children with NF1 had significantly lower social skills compared to the normative mean (Table 2; M = 100, SD = 15; t(39) = −3.38, q = .004, d = 0.54). School age social skills were not significantly correlated with age (rho = .049, q = .38).

EC social skills (M = 96.24, SD = 16.58) did not differ significantly from SA social skills for children with NF1 (M = 92.76, SD = 13.51, Z(24) = −1.09, q = .35, d = 0.23) and were not significantly correlated across time (using visit one data; rho = .29, q = .17), with a small to medium effect size. To further explore longitudinal relations, early childhood was grouped into two age groups using any visit number rather than visit one only: (1) 3- and 4-year-olds and (2) 5- and 6-year-olds. 16 participants were represented in both age groups. EC social skills for the 3- and 4-year-olds were not significantly correlated with SA social skills (rho(17) = .32, q = .17), with a small to medium effect size. EC social skills of the 5- and 6-year-olds were significantly correlated with SA social skills (rho(24) = .56, q = .01). Social skills difficulties were observed for 32% of young children and 24% of school age children with NF1. Exact McNemar’s test indicated no significant difference in the proportion of social skills difficulties over time (q = .69). Further examination of social skills difficulties revealed that 4% of young children and 8% of school age children had social skills difficulties greater than 2 standard deviations below the mean.

Relations of ADHD symptomatology and cognitive functioning with social skills

Table 3 includes the correlations of social skills with ADHD symptomatology and cognitive functioning during early childhood, school age and across time. ADHD symptomatology within the longitudinal sample increased from early childhood to school age (Inattention: Z(24) = −2.89, q = .008, d = 0.94; Hyperactivity: Z(24) = −3.37, q = .004, d = 1.03). EC CPRS-R Hyperactivity and Cognitive Problems/Inattention had significant negative correlations, ranging from weak to moderate strength, with EC SSRS social skills. T1 CPRS-R Cognitive Problems/Inattention was significantly negatively correlated with T2 SSIS social skills with a medium effect size. SA Conners-3 Hyperactivity/Impulsivity and Inattention were significantly negatively correlated with SA SSIS social skills, with strength in the moderate range. Cognitive functioning was not significantly correlated with social skills.

Table 3.

Spearman’s rho correlations between social functioning standard scores and ADHD symptomatology and cognitive functioning by sample

| Social Functioning | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Childhood | School Age | ||||

| SSRS | SSIS | ||||

| Scale | rho | q | rho | q | |

| n = 50 | n = 25 | ||||

| Early Childhood | ADHD Symptomatology (CPRS-R) | ||||

| Hyperactivity | −.46 | .004** | −.05 | .42 | |

| Cognitive Problems/Inattention | −.25 | .046* | −.39 | .034* | |

| Cognitive Functioning (DAS-II) | |||||

| General Conceptual Ability (GCA) | .26 | .03* | −.06 | .39 | |

| Verbal | .15 | .14 | −.19 | .18 | |

| Nonverbal | .21 | .07 | .15 | .24 | |

| Spatial | .22 | .097 | .15 | .26 | |

| n = 40 | |||||

| School Age | ADHD Symptomatology (Conners-3) | ||||

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | - | −.35 | .021* | ||

| Inattention | - | −.42 | .008* | ||

| Cognitive Functioning (DAS-II) | |||||

| General Conceptual Ability (GCA) | - | .025 | .44 | ||

| Verbal | - | −.05 | .37 | ||

| Nonverbal | - | .01 | .48 | ||

| Spatial | - | .09 | .29 | ||

Note: Significant Spearman’s rho correlations with False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction:

q < .05;

q < .01.

SSRS: Social Skills Rating System; SSIS: Social Skills Improvement System; CPRS-R: Conners Parent Rating Scales – Revised; Conners-3: Conners 3rd Edition - Parent Short Form. DAS-II: Differential Ability Scales-Second Edition. GCA: General Conceptual Ability.

DISCUSSION

The emergence and stability of parent-reported social skills challenges in children with NF1 were characterized in the early childhood and school age periods in this investigation. As hypothesized, parents of young and school age children with NF1 reported poorer social skills compared to the normative mean. Rates of social skills difficulty were relatively stable throughout early childhood and school age. Approximately 1/3 of young children and 1/4 of school age children with NF1 displayed social skills difficulties with no significant difference in the proportion of social skills difficulties at each timepoint. Children with NF1 ages 3, 4 and 5 years (but not age 6) had significantly lower social skills compared to the normative mean, which provides partial support for our hypothesis. Longitudinally, social skills ratings did not differ from early childhood to school age, though they were not significantly correlated. However, when multiple time points within early childhood were considered as predictors of social skills in school age, social skills at the end of early childhood (5 and 6 years old, which could also be termed early school age) were indeed predictive of social skills during school age.

The current study, together with available literature, provides evidence that social skills difficulties in children with NF1 are variable. In fact, the BASC and BASC-2 have been used as a measure of social skills and have generally indicated that young children with NF1 do not have poorer social skills compared to normative data19 or unaffected controls,14,19 which is distinct from the current findings with a more comprehensive measure of social skills. There is a need for continued research to determine which social functioning measure is most sensitive to identifying social deficits in children with NF1. Here, parent reported social skills difficulties occurred in 24–32% of the sample of children with NF1 (rates that are comparable to another study1), which illustrates that many children with NF1 (at least 2/3) do not have significant social skills difficulties. Distinctions between terminology used to describe social skills and functions have been made and suggest social functioning measures likely tap different social constructs and these constructs should be evaluated independently.34 An exploratory examination of the social skills items most frequently endorsed by parents during early childhood and school age years for children with NF1 was conducted and revealed that the specific social skills that were problematic varied across children. Few social skills evaluated on the SSRS and SSIS emerged as consistent weaknesses – compromising in conflict situations and introducing themselves to other people are the only items to emerge as problematic for a substantial subset of the children with NF1 across time. However, it should be noted that without a control group in the current investigation, areas of strengths and weaknesses identified are strictly relative, for children with NF1, rather than normative.

There has been suggestion within the NF1 literature of an increased vulnerability for autism spectrum disorders (ASD) with 13–33% of children with NF1 meeting criteria for ASD and frequently reported subthreshold ASD symptoms (social communication impairment as well as restricted and repetitive behaviors).35,36 A recent multisite study identified a strong correlation between a measure often used to examine ASD symptomatology (Social Responsiveness Scale-2) and the central social skills measure used in this investigation (SSIS).37 Overlap with the autism spectrum remains somewhat controversial. There is evidence to suggest that associations with ASD may be confounded by ADHD symptomatology, emotional functioning and communication challenges.38,39 At least one study has found that children with NF1 had significantly milder social deficits compared to individuals with ASD.40 The majority of studies that have examined social skills using the SSRS and SSIS in children and adolescents with ASD have reported social skills in the below average range41 while the current investigation found mean social skills in the average range for children with NF1. Some children with NF1 may indeed also show sociocommunicative and repetitive behaviors that are consistent with comorbid ASD diagnosis. ASD symptomatology was not addressed in the current investigation and may warrant additional attention in future social skills investigations. Further, studies of the relatively new diagnostic category of Social Communication Disorder among children with NF1 are needed.

As hypothesized and consistent with prior research with older children,1,8 ADHD symptomatology was negatively correlated with social skills cross-sectionally, with weak to moderate strength depending on the scale, for young children and school age children with NF1. Additionally, inattention in early childhood predicted school age social skills, while hyperactivity/impulsivity did not show such relations over time. In contrast, social skills were not related to cognitive functioning, consistent with some previous investigations.1,8,12 It is evident that children with NF1 who present with attention problems are at-risk for social difficulties1,42 and that this relation is seen even when attention problems are assessed in young children. Providers should supply social skills training resources and recommendations to aid in supporting social skills for children with NF1 who present with ADHD symptomatology in early childhood.

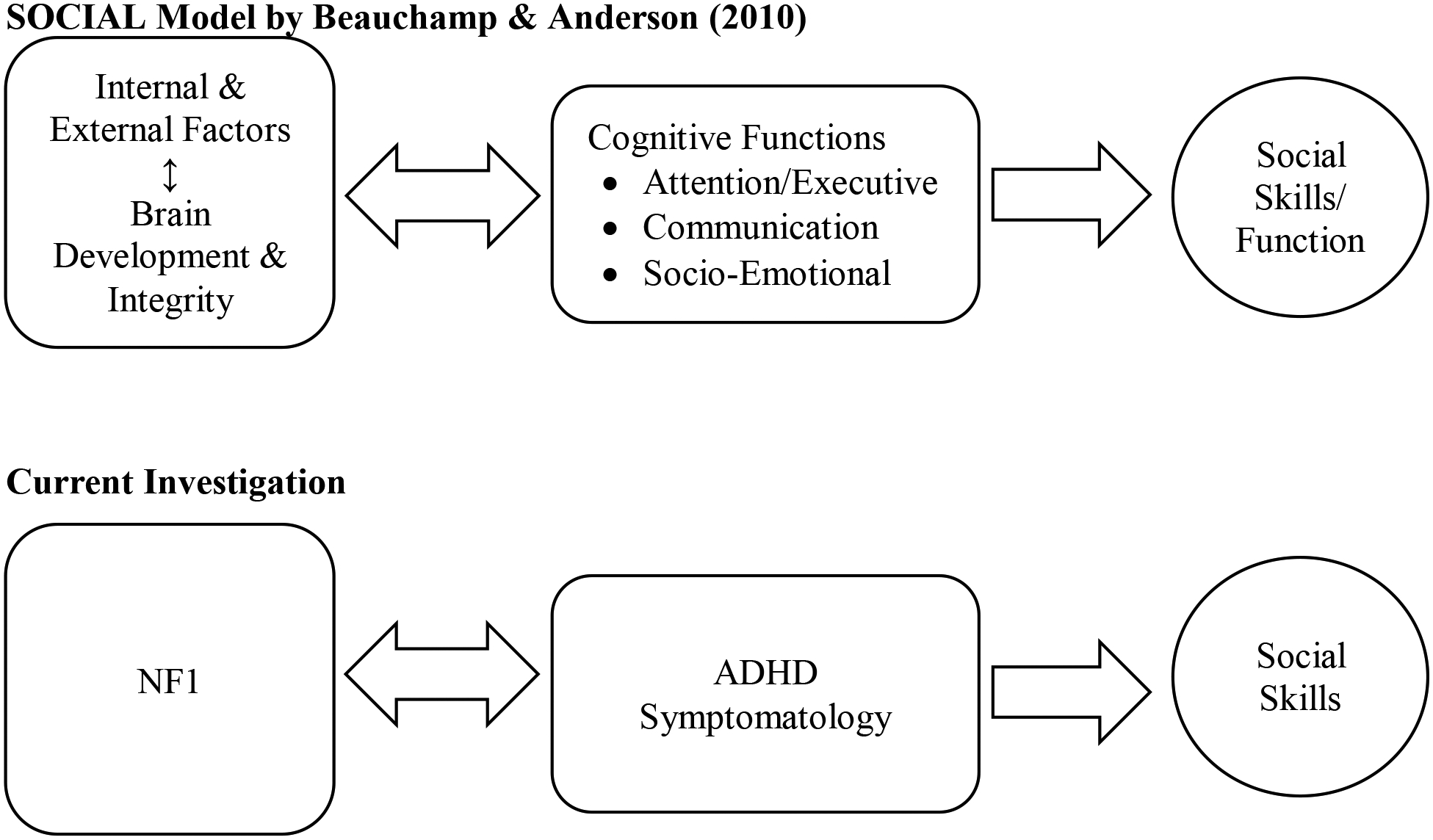

The findings of this investigation correspond to the socio-cognitive integrations of abilities (SOCIAL) model (Figure 1).34 This model suggests multiple dimensions, such as biological functioning, cognitive functions, and internal and external factors, interact to determine an individual’s social function. Any component of this model could be altered during development to influence social function directly or indirectly as well as positively and negatively. Consistent with the SOCIAL model, this study shows that internal factors such as NF1, have the capacity to shape the emergence of social function. Additionally, ADHD symptomatology is directly influencing the social skills of children with NF1. The SOCIAL model also includes physical attributes as a mediator of social function which have been discussed in relation to the physical manifestations of NF1 as important for future research. For example, impairments in social functioning have been found to be associated with physical manifestations of NF1 for adults,22 however, studies in children have not found relations with appearance5 but rather clinical severity broadly.1 Previous research in older children has also indicated that greater NF1 neurological severity (which includes headaches, brain tumors, seizures, vision impairments as well as cognitive, learning, attention, and behavior difficulties) has been found to be associated with poorer social, emotional, and behavioral functioning.5 It is important to note that research describes the progressive nature of NF1 physical symptomatology23; relations of social functioning with NF1 physical manifestations and visibility may become more pronounced within adolescence and adulthood when visible symptoms of NF1 are more likely to be present.

Figure 1. Graphic representation of SOCIAL Model (Beauchamp & Anderson, 2010) and a comparison with the current investigation.

Note. A unidirectional arrow illustrates the factor’s impact on an outcome. The bidirectional arrows represent factors that influence each other. NF1: neurofibromatosis type 1; ADHD Symptomatology: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder symptoms including inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity.

The present study is the first to report on social skills longitudinally in children with NF1 as well as the first to report on relations with social skills over time. However, the study design has several limitations that point to future directions. First, while previous longitudinal research in NF1 has utilized samples sizes smaller than or similar to the current longitudinal sample size,43,44 the sample size is nevertheless relatively small and there is a higher than expected frequency of de novo cases in the longitudinal sample, which detracts from its representativeness of the NF1 population. Second, the current investigation relies on parent report of social skills and attention difficulties which introduce a possible response bias and common methods bias. These measures might not capture the full range of skills necessary to engage socially or the extent of ADHD symptomatology that occurs in a variety of contexts including real-world behavior. Parent-report of children’s social functioning may not correspond to a child’s acceptance and status among peers such that peer nominations and peer-report of social abilities may be a more useful measure of social functioning.45, 46 Although concerns about low correspondence between parent-report on the SSRS and peer-report of social abilities have been raised,45 studies examining the effectiveness of the Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS) intervention on social functioning in children with ASD and ADHD have found improvements both in real-world behavior, such as increased social knowledge and increased frequency of hosted and invited get-togethers, as well as increased parent ratings on the SSIS48–50. No such studies are available in the early childhood period. There has been only one published study of social functioning using peer-reports in children with NF1,5 suggesting that such an approach may be less feasible in a rare population than are parental questionnaires. While behavior rating scales do have limitations, they have a number of advantages including quantifiable information with strong reliability, assessment of a broad range of social behaviors, and available normative data to compare individual performance to a representative sample.47 Indeed, the REiNS group, a collective of experts about neurocognitive functioning in NF1, has developed expert consensus about the measurement of social functioning in NF1 as an endpoint in clinical trials, and has pointed to the SSIS as a core recommended measure (Janusz et al., under review). Nevertheless, future research examining relations between parental ratings of social functioning and real-world social behavior is needed. Third, the current study is limited by a lack of a comparison group, which would have been useful in determining the presence of social skills difficulties, the persistence of difficulties over time and social strengths and weaknesses in comparison to unaffected controls.

Future research should include a multi-site approach to help to ensure a large sample that has adequate representation of all ages and NF etiologies, greater power to detect significant findings and the opportunity for a comparison group. A multi-situational and multi-informant approach45 would be beneficial including exploration of relations among informants and with observational or peer-report approaches. Additionally, research about early indicators and trajectories of these challenges may help identify areas of support at key developmental periods for optimal social development. Lastly, research should focus on identification and implementation of evidence-based social skills interventions for children with NF1 who experience social difficulties as there is no currently available literature of the efficacy of such interventions with children with NF1. In addition to social skills group interventions (e.g., PEERS48–50), peer-based interventions may also be a promising avenue to improve status among peers.51

Overall, this research contributes to a better understanding of when social skills difficulties emerge, the frequency at which social skills challenges occur for young children and school age children and the persistence of social skills difficulties over time in NF1 using parent report. It is important given the reduction in quality of life related to social functioning reported for children with NF18,52 and the variety of negative outcomes associated with social difficulties.53 This research highlights the need for increased awareness regarding possible social skills difficulties among parents and teachers of children with NF1 and supports the importance of identification and implementation of early and effective intervention related to social skills challenges.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants and their families. We are grateful to James Tonsgard, Scott Hunter, Pamela Trapane, Donald Basel, Robert Listernick, Dawn Siegel, and Heather Radtke for assistance with participant identification and recruitment. We also acknowledge our research lab team for their work and collaboration. This work was supported by grants from NFMidwest, NFMidAtlantic, NFNortheast, University of Chicago Clinical and Translational Science Award [Grant Number UL1 RR024999], and the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Research Growth Initiative. The funding sources were not involved in the conduct of the study or writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: For all authors, none were declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barton B, North K. Social skills of children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46:553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huijbregts SCJ, de Sonneville LMJ. Does Cognitive Impairment Explain Behavioral and Social Problems of Children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1? Behav Genet. 2011;41(3):430–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huijbregts SC, Loitfelder M, Rombouts SA, et al. Cerebral volumetric abnormalities in Neurofibromatosis type 1: associations with parent ratings of social and attention problems, executive dysfunction, and autistic mannerisms. J Neurodevelop Disord. 2015;7(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loitfelder M, Huijbregts SCJ, Veer IM, et al. Functional Connectivity Changes and Executive and Social Problems in Neurofibromatosis Type I. Brain Connecty. 2015;5(5):312–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noll RB, Reiter-Purtill J, Moore BD, et al. Social, emotional, and behavioral functioning of children with NF1. Am J Med Genet. 2007;143A(19):2261–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller DT, Freedenberg D, Schorry E, et al. Health Supervision for Children With Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Pediatr. 2019;143(5):e20190660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cipolletta S, Spina G, Spoto A. Psychosocial functioning, self-image, and quality of life in children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. Child Care Health Dev. 2018;44(2):260–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen T, Willard VW, Anderson LM, et al. Social functioning and facial expression recognition in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2016;60(3):282–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dilts C, Carey J, Kirchner J. Children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis 1: a behavioral phenotype. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1996;17:229–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson N, Saal H, Lovell A, et al. Social and emotional problems in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: evidence and proposed interventions. J Pediatr. 1999;134(6):767–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Vaart T, Rietman AB, Plasschaert E, et al. Behavioral and cognitive outcomes for clinical trials in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology. 2016;86(2):154–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.K Lewis A, A Porter M. Social Competence in Children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Relationships with Psychopathology and Cognitive Ability. J Child Dev Disord. 2016;2:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mautner V-F, Kluwe L, Thakker SD, et al. Treatment of ADHD in neurofibromatosis type 1. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;44(3):164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sangster J, Shores EA, Watt S, et al. The Cognitive Profile of Preschool-Aged Children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Child Neuropsychol. 2010;17(1):1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahone EM. Measurement of attention and related functions in the preschool child. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2005;11(3):216–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cutting L, Clements A, Lightman A, et al. Cognitive profile of neurofibromatosis type 1: rethinking nonverbal learning disabilities. Learn Disabil Res Pract. 2004;19(3):155–165. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyman S, Shores A, North K. The nature and frequency of cognitive deficits in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology. 2005;65:1037–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin S, Wolters P, Baldwin A, et al. Social-emotional Functioning of Children and Adolescents With Neurofibromatosis Type 1 and Plexiform Neurofibromas: Relationships With Cognitive, Disease, and Environmental Variables. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37(7):713–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein-Tasman BP, Janke KM, Luo W, et al. Cognitive and psychosocial phenotype of young children with neurofibromatosis-1. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20:88–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ejerskov C, Lasgaard M, Østergaard JR. Teenagers and young adults with neurofibromatosis type 1 are more likely to experience loneliness than siblings without the illness. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(6):604–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pride NA, Crawford H, Payne JM, et al. Social functioning in adults with neurofibromatosis type 1. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34(10):3393–3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hummelvoll G, Antonsen KM. Young Adults’ Experience of Living with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J Genet Counsel. 2013;22(2):188–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeBella K, Szudek J, Friedman JM. Use of the National Institutes of Health Criteria for Diagnosis of Neurofibromatosis 1 in Children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3):608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casnar CL & Klein-Tasman BP. Parent and teacher perspectives on emerging executive functioning in preschoolers with neurofibromatosis type 1: comparison to unaffected children and lab-based measures. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42:198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nijmeijer JS, Minderaa RB, Buitelaar JK, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and social dysfunctioning. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(4):692–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tipton LA, Christensen L, Blacher J. Friendship Quality in Adolescents with and without an Intellectual Disability. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. Published online April 2013:n/a–n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gresham FM & Elliott SN. Manual for Social Skills Rating System. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gresham FM & Elliott SN. Manual for Social Skills Improvement System. Bloomington, MN: NCS Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conners CK. Conners Parent Rating Scale Revised. Toronto, Ontario: Multi-Health Systems; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conners CK. Conners. 3rd ed. Toronto, Ontario: Multi-Health Systems; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elliott CD Manual for the Differential Abilities Scales. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duncan GJ & Magnuson KA. Off with Hollingshead: Socioeconomic resources, parenting, and child development. In: Bornstein MH, Bradley RH, ed. Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, and Child Development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003: 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cirino PT, Chin CE, Sevcik RA, et al. Measuring socioeconomic status. Assessment. 2002;9:145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beauchamp MH, Anderson V. SOCIAL: An integrative framework for the development of social skills. Psychol Bulletin. 2010;136(1):39–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garg S, Lehtonen A, Huson SM, et al. Autism and other psychiatric comorbidity in neurofibromatosis type 1: evidence from a population-based study: Autism and Other Psychiatric Comorbidity in NF1. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(2):139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh KS, Vélez JI, Kardel PG, et al. Symptomatology of autism spectrum disorder in a population with neurofibromatosis type 1: ASD in neurofibromatosis type 1. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(2):131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Payne JM, Walsh KS, Pride NA, et al. Social skills and autism spectrum disorder symptoms in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: evidence for clinical trial outcomes. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62(7):813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klein‐Tasman BP. Are the autism symptoms in neurofibromatosis type 1 actually autism? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020: 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morotti H, Mastel S, Keller K, et al. The Association of Neurofibromatosis and Autism Symptomatology Is Confounded by Behavioral Problems. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adviento B, Corbin IL, Widjaja F, et al. Autism traits in the RASopathies. J Med Genet. 2014;51(1):10–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laugeson EA, Gantman A, Kapp SK, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Improve Social Skills in Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: The UCLA PEERS® Program. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(12):3978–3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lidzba K, Granström S, Lindenau J, et al. The adverse influence of attention-deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity on cognition in neurofibromatosis type 1: Neurofibromatosis Type 1 and AD(H)D. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(10):892–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cutting L, Huang G, Zeger S, et al. Growth curve analyses of neuropsychological profiles in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: specific cognitive tests remain “spared” and “impaired” over time. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8(6):838–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Payne JM, Pickering T, Porter M, et al. Longitudinal assessment of cognition and T2-hyperintensities in NF1: An 18-year study. Am J Med Genet. 2014;164(3):661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoza B, Gerdes A, Mrug S, et al. Peer-assessed outcomes in the multimodal treatment study of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Adol Psychol. 2005; 34: 74–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noll RB, Bukowski WM. Commentary: Social competence in children with chronic illness: The devil is in the details. J Pediatr Psychol, 37:959–966, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gresham FM, Elliott SN, Cook CR, et al. Cross-informant agreement for ratings for social skill and problem behavior ratings: An investigation of the Social Skills Improvement System—Rating Scales. Psychol Assess. 2010;22(1):157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laugeson EA, Frankel F, Gantman A, et al. Evidence-Based Social Skills Training for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders: The UCLA PEERS Program. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(6):1025–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gardner DM, Gerdes AC, Weinberger K. Examination of a Parent-Assisted, Friendship-Building Program for Adolescents With ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2015;23(4):363–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schohl KA, Van Hecke AV, Carson AM, et al. A Replication and Extension of the PEERS Intervention: Examining Effects on Social Skills and Social Anxiety in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(3):532–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Locke J, et al. Making the connection: randomized controlled trial of social skills at school for children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012; 53:431–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Graf A, Landolt MA, Mori AC, et al. Quality of life and psychological adjustment in children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Pediatr. 2006;149(3):348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM. Childhood Peer Relationship Problems and Later Risks of Educational Under-achievement and Unemployment. J Child Psychol & Psychiat. 2000;41(2):191–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]