Abstract

An analytical methodology combining solid-phase extraction (SPE) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was developed to quantitate the intracellular active 5′-triphosphate (TP) of β-l-2′,3′-dideoxy-5-fluoro-3′-thiacytidine (emtricitabine) (FTC) in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). The FTC nucleotides, including 5′-mono-, di-, and triphosphates, were successively resolved on an anion-exchange SPE cartridge by applying a gradient of potassium chloride. The FTC-TP was subsequently digested to release the parent nucleoside that was finally analyzed by HPLC with UV detection (HPLC-UV). Validation of the methodology was performed by using PBMCs from healthy donors exposed to an isotopic solution of [3H]FTC with known specific activity, leading to the formation of intracellular FTC-TP that was quantitated by an anion-exchange HPLC method with radioactive detection. These levels of FTC-TP served as reference values and were used to validate the data obtained by HPLC-UV. The assay had a limit of quantitation of 4.0 pmol of FTC-TP (amount on column from approximately 107 cells). Intra-assay precision (coefficient of variation percentage of repeated measurement) and accuracy (percentage deviation of the nominal reference value), estimated by using quality control samples at 16.2, 60.7, and 121.5 pmol, ranged from 1.3 to 3.3% and −1.0 to 4.8%, respectively. Interassay precision and accuracy varied from 3.0 to 10.2% and from 2.5 to 6.7%, respectively. This methodology was successfully applied to the determination of FTC-TP in PBMCs of patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus after oral administration of various dosing regimens of FTC monotherapy.

Nucleoside analogs are an important class of antiviral drugs for the treatment of both human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections. HIV-1 and HBV, the causative viruses of AIDS and acute and chronic hepatitis, respectively, affect more than 100 million (HIV) and 300 million (HBV) people worldwide. Despite the availability of 14 drugs, including six nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), that have greatly increased treatment options for HIV-1 infections, there is still no cure for AIDS. Cross-resistance and tolerance issues warrant the search for new compounds with a superior antiviral activity and a better safety profile. Although a vaccine is available for HBV, treatment with alpha interferon and nucleoside analogs alone and in combination appears to be the only alternative for HBV carriers. Moreover, current treatment options are limited by toxicity issues and by the fact that not all patients respond to therapy (9, 17). Therefore, there are continuous needs for the development of novel antiviral agents.

β-l-2′,3′-Dideoxy-5-fluoro-3′-thiacytidine (emtricitabine) (FTC) is an analog of deoxycytidine that is currently under clinical development for the treatment of HIV-1 and HBV infections (1). This compound possesses an unnatural β-l structural configuration (Fig. 1) that has apparently conferred on it higher in vitro antiviral activity against both HIV-1 (50% effective concentration [EC50] = 10 to 20 nM) and HBV (EC50 = 10 to 40 nM) and lower toxicity than the natural β-d enantiomer (2, 5, 14, 20). The in vitro activity of FTC against HIV-1 is approximately 4- to 10-fold more potent than 3TC, a close analog that has been approved for the treatment of both HIV-1 and HBV infections (2). This in vitro finding was recently confirmed by the results of a phase I/II clinical trial of FTC at 25, 100, and 200 mg once a day (q.d.) compared with 3TC at 150 mg twice a day (b.i.d.) in HIV-infected patients (1). Similar to other nucleoside analogs, FTC requires multistep intracellular phosphorylation by various cellular kinases to its 5′-monophosphate (MP), diphosphate (DP), and the active triphosphate (TP) (5, 10). The FTC 5′-TP (FTC-TP) competitively inhibits HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and can also be incorporated into viral genome, causing termination in DNA chain elongation. HBV is a member of the hepadnavirus family whose replication cycle includes the reverse transcription of an RNA template (6). This reverse transcription process is the target of the anti-HBV nucleoside analogs, including FTC.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of FTC.

One of the primary objectives of clinical pharmacologic research of antiretroviral agents is to define pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships which could allow more rational selection of therapeutic regimens that are expected to maximally suppress viral replication while preserving safety. Efforts to correlate plasma pharmacokinetics of anti-HIV nucleoside analogs to their virologic and/or immunologic outcomes have had little success, with the exception of didanosine, for which a relationship between its plasma pharmacokinetics and the suppression of HIV p24 antigen has previously been documented in patients (3). Since NRTIs require intracellular activation, it has previously been hypothesized that the intracellular level of their active 5′-TP anabolite may be an appropriate predictor of the virologic response (7, 21, 25, 26). Recent data have shown that a higher level of intracellular zidovudine 5′-TP was associated with a better suppression of plasma viral load and an increase in CD4+ cell count in HIV-infected individuals (4). Previous studies also strongly supported this hypothesis with the demonstration that intracellular concentrations of the active 5′-TP of lamivudine and stavudine, rather than levels of the parent nucleosides in plasma, correlated with virologic response in HIV-infected patients (18, 19). Intracellular pharmacokinetic analysis of antiviral nucleoside analogs in large-scale clinical trials has been made possible by recent advances in analytical techniques that allow specific and reproducible quantitation of subpicomole amounts of the nucleotides. Although nucleotide-specific enzymatic assays that directly measure the TP based on inhibition of reverse transcriptase activity are available (12), methodologies using chromatographic separation of intracellular phosphates, enzyme digestion followed by radioimmunoassay, or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with UV (HPLC-UV) or mass spectrometric detection are more appealing since TPs from different nucleosides can be simultaneously isolated (8, 11, 13, 15, 16, 22). This technique is especially suitable for samples obtained from AIDS clinical trials, where two or more NRTIs are often used in combination therapy. The separation processes of 5′-MP, DP, and TP are critical and have been initially performed by strong anion-exchange HPLC that was highly selective although time consuming (15). The separation method was recently improved by using an anion-exchange solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridge (11), which is preferred for large clinical trials since multiple samples can be simultaneously processed. This latter technique was first applied to a zidovudine TP assay (11) and was recently used to quantitate intracellular nucleotides of lamivudine in AIDS patients (13, 16).

This report describes the development and validation of an analytical methodology that combines an anion-exchange SPE procedure with an HPLC technique for the separation and quantitation of FTC-TP in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Assay performance, including purity of extracted nucleotides, extraction recovery, and intra- and interassay variability, was evaluated. This method was successfully applied to determine the level of FTC-TP in PBMCs isolated from HIV-infected patients receiving various oral regimens of FTC monotherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Nonlabeled FTC (molecular weight = 247) was provided by Triangle Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Durham, N.C.). [6-3H]FTC (5 Ci/mmol) was obtained from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, Calif.). β-l-2′,3′-Dideoxy-5-fluorocytidine (β-l-FddC; molecular weight = 229), used as an internal standard (IS), was kindly provided by J. L. Imbach and G. Gosselin (Montpellier, France). These standards were more than 98% pure as ascertained by the HPLC methods described below. Alkaline phosphatase (3.100 U/mg of protein) and phosphodiesterase I (31.0 U/mg [dry weight]) for enzyme digestion were purchased from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Freehold, N.J.). HPLC-grade potassium chloride (KCl), potassium phosphate monobasic, orthophosphoric acid (85%), acetonitrile, and methanol were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, N.J.). All other chemicals used were of analytical grade.

Preparation of FTC-TP standards.

The unavailability of nucleotide standards of FTC led us to adopt an assay validation strategy that included the exposure of PBMCs from healthy human donors to tritiated FTC with known specific activity to produce intracellular phosphates of FTC in vitro. A classical anion-exchange HPLC technique was then used to accurately determine the FTC-TP level in a fraction of the total cell extracts based on its radioactivity and the specific activity of the probe. The rest of the cell extracts with hence known levels of FTC-TP were then used to prepare calibration standards or quality controls (QCs) to validate the nonradioactive HPLC method with UV detection. Briefly, human PBMCs were isolated from fresh whole blood. Blood was diluted with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and laid onto a Ficoll-Histopaque density gradient in 50-ml conical tubes. After centrifugation at 500 × g for 30 min at room temperature, the layer containing PBMCs was carefully recovered and washed three times with PBS. Isolated PBMCs were then suspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine and stimulated for 48 h with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. All cultures were maintained at 37°C, under an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

After stimulation, cells were resuspended in PHA-free medium at a cytocrit of 2 × 106 cells/ml. An isotopic solution of [3H]FTC (specific activity, 74.6 dpm/pmol) was added to the culture at a final concentration of 10 μM and incubated for 24 h with a final incubation volume of 50 ml in a 100-ml culture flask. Practically, 8 to 10 flasks were processed simultaneously. Following incubation, cells (around 100 × 106 cells/flask) were pelleted by centrifugation and rinsed three times with cold PBS. Cell pellets from all flasks were pooled and extracted twice with 4 ml of 60% methanol at −70°C overnight. Cellular debris was then removed by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 min. The resulting supernatant containing FTC nucleotides was collected and stored as 500-μl aliquots at −70°C until analysis. These aliquots were to serve as standards of the calibrating curve or as QC samples. Standards and QCs were from independent incubations using separate sources of isotopic dilution of [3H]FTC. The quantity of FTC-TP was determined in triplicate for aliquots of both standards and QCs by the anion-exchange HPLC method described below. This classical anion-exchange HPLC method is able to separate all FTC nucleotides. Prior to analysis, methanol was evaporated under a gentle nitrogen flow and the volume of the remaining aqueous phase was adjusted to 200 μl with deionized water. A portion of this phase (20 μl) was accurately pipetted. This portion underwent liquid scintillation counting to assess the total radioactivity. All of the remaining phase (around 180 μl) was to be analyzed by anion-exchange HPLC to directly quantitate intracellular levels of FTC-TP based on the radioactivity of the nucleotide and the specific activity (74.6 dpm/pmol). The mean level of FTC-TP from the triplicate aliquots therefore served as a reference value for the preparation of standards or QCs using the remaining authentic aliquots (13 500-μl aliquots for standards and QCs) for the validation of the HPLC-UV method. A five-point calibration curve at 8.1 (2.0), 20.2 (5.0), 40.5 (10.0), 81.0 (20.0), and 202.4 (50.0) pmol (equivalent amount of FTC in nanograms) of FTC-TP on column and three QCs at 16.2 (4.0), 60.7 (15.0), and 121.5 (30.0) pmol (ng) on column were prepared. The calibration standards and QCs were simultaneously processed by anion-exchange SPE followed by enzyme digestion to hydrolyze FTC phosphates. Fractions containing FTC were subsequently quantitated by reverse-phase HPLC with UV detection as described later in this report.

FTC-TP in PBMCs from HIV-infected patients.

This methodology was applied to measure levels of FTC-TP in PBMCs from HIV-infected patients enrolled in a phase I/II clinical trial of FTC. Five groups of patients received, over 2 weeks, escalating doses of FTC at 25 mg b.i.d., 100 mg q.d., 100 mg b.i.d., 200 mg q.d., and 200 mg b.i.d. (23, 24). This study was approved by each of the six Institutional Review Boards of the six participating sites. Forty HIV-infected patients were enrolled after giving written informed consent and were sequentially assigned to receive one of the regimens. At least 15 ml of blood was drawn into two Vacutainer CPT cell preparation tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) prior to and at 1, 3, 9, and 12 h after the first dose of FTC. The tubes were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 20 min at room temperature. The upper layer, containing plasma and PBMCs, was recovered. A 500-μl aliquot was used to count PBMCs and the remaining portion was centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min to pellet the cells. Plasma was removed and 200 μl of 60% methanol was added to the cell pellet. Patient samples were shipped on dry ice and stored under −70°C until analyzed.

Anion-exchange SPE.

SPE was performed using anion-exchange cartridges (Sep-Pack VAC, 100-mg phase; Waters, Milford, Mass.). Cartridges were preconditioned with 500 μl of deionized water. Cell extracts (calibration standards, QCs, and patient samples) were loaded onto the cartridge and eluted under reduced pressure. The cartridge was then washed with 500 μl of water. This fraction combined with that obtained from the initial step represents the unchanged FTC nucleoside, and the cartridge was rinsed with 500 μl of water and 200 μl of 20 mM KCl. The nucleotides of FTC, including its 5′-MP, DP, and TP, were successively resolved and eluted by using a KCl gradient. Briefly, FTC-DP-choline was eluted with 400 μl of 60 mM KCl and the cartridge was rinsed with 100 μl of the buffer. The 3TC-MP, -DP, and -TP were eluted with 300 μl of 100 mM KCl, 400 μl of 120 mM KCl, and 500 μl of 400 mM KCl, respectively. The cartridge was rinsed with 100 μl of the corresponding buffers between each step. Following SPE, purity of the unchanged drug and each nucleotide was checked by the anion-exchange HPLC analysis as described below. The identity of these nucleotides was assessed based on their relative retention time and enzyme digestion using alkaline phosphatase and/or phosphodiesterase.

Enzyme digestion.

The phosphates of FTC resolved from the SPE step were then subjected to enzyme digestion to release the nucleoside. Fractions containing the phosphates were incubated with alkaline phosphatase (50 U/fraction) at 37°C overnight. Following digestion, acetonitrile (3 volumes) was added to precipitate proteins. Supernatant was recovered after centrifugation and dried under nitrogen. The residue was then dissolved in 150 μl of water containing 50 ng (218 pmol) of β-l-FddC as an IS and analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC as described later in this section.

Anion-exchange HPLC with radioactive detection.

Aliquots of cell extracts, serving to prepare calibration standards, and QCs were analyzed by HPLC on an HP model 1090M chromatograph (Hewlett-Packard Company, Palo Alto, Calif.) equipped with an automatic injector and a diode array detector. Anion-exchange HPLC was performed on a 4.6-mm (inner diameter) by 250-mm Partisil, 10-μm SAX column (Jones Chromatography, Lakewood, Colo.) with a 65-min linear gradient of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 3.5) at a constant flow of 1 ml/min from 8 mM to 1 M starting at 10 min. Eluent from the column was fractionated at 1-min intervals by using a RediFrac fraction collector (Pharmacia LKB, Uppsala, Sweden). After the addition of 5 ml of scintillation fluid, the vials were counted on an LS 5000 TA scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments Inc., Fullerton, Calif.). Intracellular levels of FTC-TP were calculated based on radioactivity of the peak and the specific activity. These levels served as the reference values to prepare calibration standards and QCs.

Reverse-phase HPLC-UV.

Fractions representing FTC-TP obtained after SPE and enzyme digestion were analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC using the HP 1090M liquid chromatography system. Briefly, an aliquot (150 μl) of the reconstituted dry residue was injected. FTC was isocratically chromatographed on a reverse-phase C18 column (Columbus, 5-μm particle size, 4.6 mm [inner diameter] by 250 mm; Phenomenex, Inc., Torrance, Calif.) using a mixture of phosphate buffer (43 mM, pH 7.0)–acetonitrile (93:7 [vol/vol]) at a constant flow of 1 ml/min and monitored at 280 nm. Standard curve parameters were obtained from an unweighted least-squares linear regression analysis of the nominal amount of each standard as a function of peak area ratio of analyte over internal standard. Unknown levels were calculated by interpolation using each observed peak area ratio and standard curve parameters.

Assay performance evaluation.

The performance of this methodology for the quantitation of intracellular levels of FTC-TP in human PBMCs was characterized by purity of the resolved FTC phosphates, FTC-TP recovery of the overall process, specificity and lower limit of detection and quantitation of HPLC-UV, and intra- and interassay precision and accuracy.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

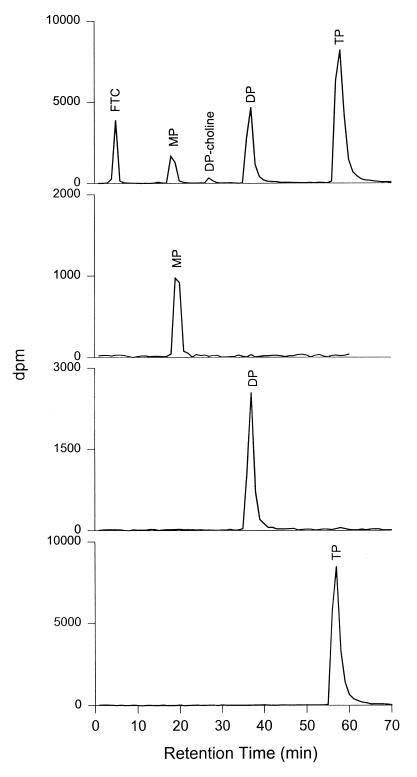

Due to the unavailability of FTC-TP standards, we developed an assay validation strategy that included the use of PBMCs from healthy human donors to produce intracellular FTC nucleotides in vitro. A concentration of 10 μM FTC was physiologically relevant and expected to lead to formation of intracellular FTC phosphates comparable to that obtained in FTC-treated patients. A similar strategy to validate an assay quantitating 3TC phosphates in human PBMCs has been previously applied (16). The levels of the intracellular TP of FTC were then measured by anion-exchange HPLC with radioactive detection and served as references to prepare calibration standards and QCs. These standards and QCs were then used to validate the nonradioactive method by an HPLC assay with UV detection for the measurement of intracellular FTC-TP in human PBMCs. Figure 2 depicts a typical phosphorylation profile of FTC in human PBMCs, illustrating the formation of its 5′-MP, DP, TP, and DP-choline derivatives. The identity of FTC derivatives was assessed by their relative retention times and was further ascertained by enzyme digestion using alkaline phosphatase and alkaline phosphatase plus phosphodiesterase for the DP-choline derivative. Unlike 3TC, which had a substantial formation of intracellular DP-choline derivative (16), FTC-DP-choline constituted a rather low percentage (<3%) of total phosphate in PBMCs from all donors (n = 7) and therefore this metabolite was not further analyzed.

FIG. 2.

Intracellular phosphorylation profile of FTC in human PBMCs and purity check by anion-exchange HPLC with radioactivity detection of the FTC nucleotides resolved by anion-exchange SPE.

Purity of FTC nucleotides following anion-exchange SPE.

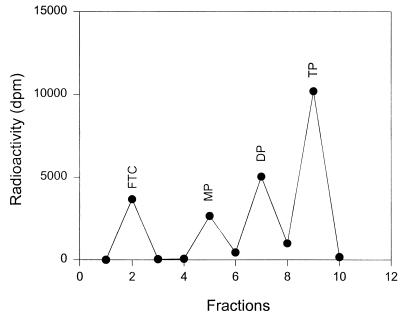

Following SPE, the four fractions representing unchanged FTC and its 5′-MP, DP, and TP derivatives were separately injected onto the anion-exchange HPLC for a purity check. As shown in Fig. 2, only a single peak was obtained in each case and was identified as the expected phosphate by comparing peak retention time, indicating that the SPE procedure led to the resolution of pure FTC nucleotides. Figure 3 shows a representative SPE profile of FTC phosphates.

FIG. 3.

Separation by anion-exchange SPE of the FTC phosphates from human PBMCs, as determined by liquid scintillation counting.

Recovery of FTC-TP.

The overall recovery of FTC-TP was assessed by comparing its amount as measured by reverse-phase HPLC with UV detection using a standard curve prepared from FTC in water to the nominal amount of the calibration standards and QCs. Authentic replicates (three for QCs at 16.2, 60.7, and 121.5 pmol of FTC-TP and five for calibration standards at 8.1, 20.2, 40.5, 81.0, and 202.4 pmol) of the aliquots of cell extracts obtained after exposure of human PBMCs to 10 μM FTC were analyzed by HPLC-UV following SPE and enzyme digestion. The standard curve was obtained by directly injecting 8.1, 20.2, 40.5, 81.0, and 202.4 pmol of FTC in water onto the chromatograph. The amount of FTC-TP in the calibration standards and QCs prepared from cell extracts was calculated by using this standard curve. The overall recovery of FTC-TP was high, ranging from 95.0 to 108.1% (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Overall recovery of FTC-TP after anion-exchange SPE and enzyme digestion

| Nominal amount (pmol on column) | n | Measured amount (pmol on column)a | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| QCs | |||

| 16.2 | 5 | 17.4 ± 0.8 | 107.2 |

| 60.7 | 5 | 57.9 ± 8.9 | 95.0 |

| 121.5 | 5 | 116.2 ± 8.1 | 95.6 |

| Calibration standards | |||

| 8.1 | 3 | 8.1 ± 0.8 | 101.4 |

| 20.2 | 3 | 21.9 ± 2.4 | 108.1 |

| 40.5 | 3 | 40.5 ± 4.5 | 99.7 |

| 81.0 | 3 | 78.9 ± 5.7 | 97.5 |

| 202.4 | 3 | 195.1 ± 16.2 | 96.4 |

Means ± standard deviations.

Selectivity of HPLC-UV.

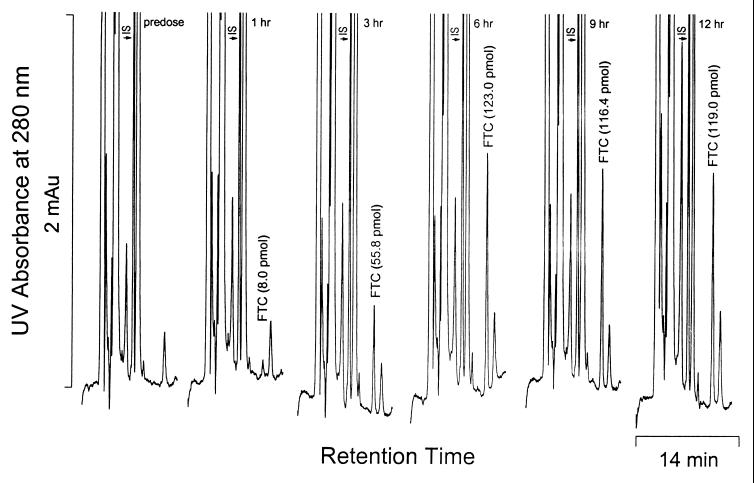

Triple or quadruple combination therapy, often involving two nucleoside analogs, is becoming a standard regimen for the treatment of HIV infections. It therefore appeared necessary to evaluate potential chromatographic interference by nucleoside antiretroviral agents and natural analogs. Under the specified chromatographic conditions (see Materials and Methods), FTC exhibited a retention time of 10.4 ± 0.2 min, while retention times for β-l-FddC (IS), ddI, d4T, 3TC, and ddA were 7.0, 4.0, 11.5, 7.9, and 5.7 min, respectively. The retention times for zidovudine, abacavir, and carbovir were greater than 13 min. Analysis of a predose PBMC sample (blank) showed no interference, demonstrating a high specificity of the HPLC-UV method (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Chromatographic profiles of FTC-TP present in all PBMC samples from a patient after oral administration of the drug. The HPLC chromatograms were obtained with UV detection following anion-exchange SPE and enzyme digestion.

LOD and LOQ.

Limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantitation (LOQ) of the HPLC-UV methodology were determined by using cell extracts for QCs. Assays were performed in triplicate with three levels of FTC-TP at 2.0, 4.0, and 6.1 pmol on column. The LOD as defined by a signal-to-noise ratio of 3 was 2.0 pmol of FTC on column with an accuracy (percent deviation from nominal amount) of 7.0% and a precision (coefficient of variation of repeated measurements [CV]) of 3.4%. The LOQ was 4.0 pmol of FTC on column associated with an accuracy of −2.0% and a precision of 3.2%. For this assay, it is more appropriate to express LOD and LOQ as amounts of the TP on column instead of as quantity normalized to cell number since cell number varies greatly across different samples within and between individuals. Furthermore, the same number of cells does not lead to the formation of the same amount of phosphates.

Intra- and interassay accuracy and precision.

Intra-assay precision (expressed as CV) and accuracy (represented by deviation from nominal values) were determined by simultaneously assessing, in replicate, five of the QCs with FTC-TP at 16.2, 60.7, and 121.5 pmol on column. Results summarized in Table 2 show excellent intra-assay performance, with an accuracy ranging from −1.0 to 4.8% and a precision ranging from 1.3 to 3.3%. Interassay accuracy and precision were assessed over a period of 2 months using both FTC-TP QCs (six independent experiments) and calibration standards (four separate experiments). As shown in Table 3, interassay performance was characterized by an accuracy of 0.4 to 6.7% and a precision of 0.9 to 10.2%.

TABLE 2.

Intra-assay accuracy and precision

| Nominal amount (pmol) | n | Measured amount (pmol)a | Accuracy (% deviation) | Precision (% CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16.2 | 5 | 16.2 ± 1.2 | −1.0 | 3.3 |

| 60.7 | 5 | 62.8 ± 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.4 |

| 121.5 | 5 | 127.1 ± 3.6 | 4.8 | 1.3 |

Means ± standard deviations.

TABLE 3.

Interassay accuracy and precision

| Nominal amount (pmol) | n | Measured amount (pmol)a | Accuracy (% deviation) | Precision (% CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QCs | ||||

| 16.2 | 6 | 15.8 ± 2.4 | 2.5 | 10.2 |

| 60.7 | 6 | 58.7 ± 5.3 | 3.3 | 5.1 |

| 121.5 | 6 | 113.4 ± 10.5 | 6.7 | 3.0 |

| Calibration standards | ||||

| 8.1 | 4 | 8.5 ± 0.8 | 5.0 | 3.7 |

| 20.2 | 4 | 19.8 ± 2.8 | 2.0 | 7.7 |

| 40.5 | 4 | 41.7 ± 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| 81.0 | 4 | 83.8 ± 1.2 | 3.5 | 0.9 |

| 202.4 | 4 | 199.6 ± 10.5 | 0.4 | 2.6 |

Means ± standard deviations.

Application to biological samples.

Using this new combined HPLC and SPE methodology, levels of FTC-TP were determined in PBMCs of HIV-infected patients receiving oral doses of either 25 mg b.i.d., 100 mg q.d., 100 mg b.i.d., 200 mg q.d., or 200 mg b.i.d. as part of a phase I/II study of FTC monotherapy (23, 24). Six blood samples were obtained prior to and up to 12 h after the first dose of FTC, and PBMCs were isolated and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Results from this study demonstrated that high intracellular levels of FTC-TP were associated with a better suppression of plasma HIV-1 RNA levels (24). Representative chromatograms of FTC-TP, reduced to FTC after enzyme digestion, in all PBMC samples from a patient are depicted in Fig. 4. Quantities of FTC-TP in the 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h PBMC samples in this patient were 8.0, 55.8, 123.0, 116.4, and 119.0 pmol, respectively. When normalized to the number of PBMCs of the samples used in the assay, the levels were 0.20, 1.48, 2.02, 2.26, and 1.52 pmol/106 cells, respectively.

In summary, an analytical methodology combining anion-exchange SPE and HPLC with UV detection was developed and validated for the quantitation of intracellular 5′-TP of FTC in human PBMCs. Although the validation was performed only on the TP, this methodology can easily be applied to measure the other phosphates of the compound, as was recently reported for 3TC-MP and DP (16), since, as demonstrated in Fig. 2, purely resolved 5′-MP and DP of FTC can be obtained. Analysis of these intermediate anabolites should lead to a better understanding of the different steps and the kinetics involved in the activation of NRTIs and to an evaluation of the contribution of these nucleotides to antiviral effects and/or toxicity. In conclusion, despite its complexity, this methodology has successfully been applied to quantitate intracellular FTC-TP in HIV-infected patients enrolled in a phase I/II clinical trial. Evaluation of intracellular pharmacokinetics of the active TP of the drug in conjunction with virologic and immunologic response should allow the establishment of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships in antiviral therapy with the drug.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grants and by Triangle Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Delehanty J, Wakeford C, Hulett L, Quinn J, McCreedy B, Almond M, Miralles D, Rousseau F. Program and abstracts of the 6th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Alexandria, Va: Foundation for Retrovirology and Human Health; 1999. A phase I/II randomized controlled study of FTC versus 3TC in HIV-infected patients, abstr. 16; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doong S L, Tsai C H, Schinazi R F, Liotta D C, Cheng Y C. Inhibition of the replication of hepatitis B virus in vitro by 2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine and related analogues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8495–8499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drusano G L, Yuen G L, Lambert J S, Seidlin M, Dolin R, Valentine F T. Relationship between dideoxyinosine exposure, CD4 counts, and p24 antigen levels in human immunodeficiency virus infection. A phase I trial. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:562–566. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-7-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher C V, Kawle S P, Page L M, Remmel R P, Acosta E P, Henry K, Erice A, Balfour H H. Program and abstracts of the 4th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Alexandria, Va: Foundation for Retrovirology and Human Health; 1997. Intracellular triphosphate concentrations of antiretroviral nucleosides as a determinant of clinical response in HIV-infected patients, abstr. 13; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furman P A, Davis M, Liotta D C, Paff M, Frick L W, Nelson D J, Dornsife R E, Wurster J A, Wilson L J, Fyfe J A, Tuttle J V, Miller W H, Condreay L, Averett D R, Schinazi R F, Painter G R. The anti-hepatitis B virus activities, cytotoxicities, and anabolic profiles of the (−) and (+) enantiomers of cis-5-fluoro-1-[2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-oxathiolan-5-yl]cytosine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2686–2692. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.12.2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganem D, Varmus H E. The molecular biology of hepatitis B virus. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:651–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao W Y, Shirasaka T, Johns D G, Broder S, Mitsuya H. Differential phosphorylation of azidothymidine, dideoxycytidine, and dideoxyinosine in resting and activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Clin Investig. 1993;91:2326–2333. doi: 10.1172/JCI116463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuster H, Vogt M, Joos B, Nadai V, Luthy R. A method for the quantification of intracellular zidovudine nucleotides. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:773–776. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.4.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee W M. Medical progress: hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;334:1733–1745. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paff M A, Averett D R, Prus K L, Miller W H, Nelson D J. Intracellular metabolism of (−)- and (+)-cis-5-fluoro-1-[2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-oxathiolan-5-yl]cytosine in HepG2 derivative 2.2.15 (subclone P5A) cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1230–1238. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.6.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robbins B L, Waibel B H, Fridland A. Quantitation of intracellular zidovudine phosphates by use of combined cartridge-radioimmunoassay methodology. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2651–2654. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robbins B L, Rodman J, McDonald C, Srinivas R V, Flynn P M, Fridland A. Enzymatic assay for measurement of zidovudine triphosphate in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:115–121. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robbins B L, Tran T T, Pinkerton F H, Jr, Akeb F, Guedj R, Grassi J, Lancaster D, Fridland A. Development of a new cartridge radioimmunoassay for determination of intracellular levels of lamivudine triphosphate in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2656–2660. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.10.2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schinazi R F, McMillan A, Cannon D, Mathis R, Lloyd R M, Peck A, Sommadossi J P, St. Clair M, Wilson J, Furman P A, Painter G R, Choi W B, Liotta D C. Selective inhibition of human immunodeficiency viruses by racemates and enantiomers of cis-5-fluoro-1-[2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-oxathiolan-5-yl]cytosine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2423–2431. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.11.2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slusher J T, Kuwahara S K, Hamzeh F M, Lewis L D, Kornhauser D M, Lietman P S. Intracellular zidovudine (ZDV) and ZDV phosphates as measured by a validated combined high-pressure liquid chromatography-radioimmunoassay procedure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2473–2477. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.11.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solas C, Li Y-F, Xie M-Y, Sommadossi J-P, Zhou X-J. Intracellular nucleotides of (−)-2′,3′-deoxy-3′-thiacytidine in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2989–2995. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.11.2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommadossi J P. Treatment of hepatitis B by nucleoside analogs: still a reality. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1994;7:678–682. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sommadossi J P, Valentin M A, Zhou X J, Xie M Y, Moore J, Calvez V, Desa M, Katlama C. Program and abstracts of the 5th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Alexandria, Va: Foundation for Retrovirology and Human Health; 1998. Intracellular phosphorylation of stavudine (d4T) and 3TC correlates with their antiviral activity in naïve and zidovudine (ZDV)-experienced HIV-infected patients, abstr. 262; p. 146. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sommadossi J P, Zhou X J, Moore J, Havlir D V, Friedland G, Tierney C, Smeaton L, Fox L, Richman D, Pollard R the NIAID ACTG 290 Investigators. Program and abstracts of the 5th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Alexandria, Va: Foundation for Retrovirology and Human Health; 1998. Impairment of stavudine (d4T) phosphorylation in patients receiving a combination of zidovudine and d4T (ACTG 290), abstr. 3; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tisdale M, Kemp S D, Parry N R, Larder B A. Rapid in vitro selection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistant to 3′-thiacytidine inhibitors due to a mutation in the YMDD region of reverse transcriptase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5653–5656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tornevik Y, Jacobsson B, Britton S, Eriksson S. Intracellular metabolism of 3′-azidothymidine in isolated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1991;7:751–759. doi: 10.1089/aid.1991.7.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toyoshima T, Kimura S, Muramatsu S, Takahagi H, Shimada K. A sensitive nonisotopic method for the determination of intracellular azidothymidine 5′-mono-, 5′-di-, and 5′-triphosphate. Anal Biochem. 1991;196:302–307. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90470-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L H, Delehanty J, Blum M R, Hulett L, Sommadossi B J P, Rousseau F. Program and abstracts of the 36th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Disease Society of America. 1998. FTC (Emtricitabine): a potent and selective anti-HIV and anti-HBV agent demonstrating desirable pharmacokinetic characteristics, abstr. 415. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L H, Delehanty J, Hulett L, McCreedy B, Sommadossi J P, Rousseau F. Program and Abstracts of the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. High levels of intracellular FTC-triphosphate correlate with the potent antiviral activity of FTC in vivo, abstr. LB-2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H, Thomas R V, Pluda J M, Hartman N R, Perno C F, Marczyk K S, Allain J P, Johns D G, Broder S. In vivo activity against HIV and favorable toxicity profile of 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine. Science. 1989;245:412–415. doi: 10.1126/science.2502840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu Z, Ho H T, Hitchcock M J, Sommadossi J P. Cellular pharmacology of 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (D4T) in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;39:R15–R19. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90418-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]