Abstract

The effect of a water-soluble malonic acid derivative of carboxyfullerence (C60) against Escherichia coli-induced meningitis was tested. C60 can protect the mice from E. coli-induced death in a dose-dependent manner. C60 administered intraperitoneally as late as 9 h after E. coli injection was still protective. The C60-treated mice had less tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1β production by staining of brain tissue compared to the levels of production for nontreated mice. The E. coli-induced increases in blood-brain barrier permeability and inflammatory neutrophilic infiltration were also inhibited. These data suggest that C60 is a potentially therapeutic agent for bacterial meningitis.

Through the years, bacterial meningitis has remained an infection with a high mortality rate, particularly in very young and elderly patients, despite the availability of effective antibiotic treatments (21, 30). The pathophysiology of bacterial meningitis involves the invasion and multiplication of bacteria in the subarachnoidal space of the central nervous system (CNS). The bacterium itself or its degraded products stimulate the production and release of proinflammatory mediators such as cytokines and prostaglandins by leukocytes, endothelial cells, astrocytes, microglial cells, and other cells in the CNS, and these subsequently lead to an increase in the permeability of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). This triggers transendothelial migration of neutrophils and leakage of plasma proteins that further damage the brain (2, 20). Proinflammatory cytokines have been shown to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of bacterial meningitis. Both tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) were detected in the cerebrospinal fluid of some patients with bacterial meningitis and in experimental animals (13, 16, 18, 19, 27). In this study, a model of experimental meningitis induced by direct injection of Escherichia coli into the brains of B6 mice was set up. As expected, TNF-α and IL-1β production was induced, followed by inflammatory neutrophil infiltration. The vasopermeability of BBB was also increased.

Buckminsterfullerene (carboxyfullerence [C60]) is characterized as a “radical sponge” due to its avid reactivity with free radicals (15). A water-soluble malonic acid derivative of C60 has been synthesized and has been found to be an effective neuroprotective antioxidant both in vitro and in vivo (7, 9, 10, 17). This study tested the effect of C60 on the E. coli-induced meningitis model, and it was found that C60 could inhibit the development of E. coli-induced meningitis. Its therapeutic application for treatment of bacterial meningitis is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Breeder mice of the strain B6 were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) or Charles River Japan, Inc. (Atsugi, Japan). They were maintained on standard laboratory chow and water ad libitum in the animal facility of the Medical College, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan. The animals were raised and cared for by following the guidelines set up by the National Science Council of the Republic of China. Eight- to 12-week-old female mice were used in all experiments.

C60.

Two regioisomers of water-soluble carboxylic acid C60 derivatives with C3 or D3 symmetry were synthesized as described previously (7). Both C60 (C3) and C60 (D3) are effective free-radical scavengers. Both compounds are potent inhibitors of neuronal apoptosis in vitro; neuronal apoptosis is associated with increased intracellular free-radical production. In this study, we used C60 (C3) dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 2 mg/ml).

Induction of bacterial meningitis.

E. coli ATCC 10536 was cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (1% NaCl, 1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract) for 12 h and was subcultured in fresh medium for another 3 h. The concentration of E. coli was determined with a spectrophotometer (Beckman Instrument, Somerset, N.J.), with an optical density at 600 nm of 1 equal to 108 CFU/ml (32). For the induction of meningitis, groups of three to four mice were given intracerebral injections directly into the temporal area of a 20-μl volume of 5 × 105 E. coli cells diluted in saline. The 100% lethal dose (LD100) by intracerebral injection in B6 mice is 5 × 105 E. coli cells. The animals were observed every 12 h for a total of 6 days. In the C60 inhibition experiments, the mice were given an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of C60 (40 mg/kg of body weight) three times every 24 h either before or after intracerebral injection of E. coli. The survival curve was presented. In some experiments, the brains were aseptically removed and were homogenized with 3% gelatin (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) in PBS. The samples were serial diluted, poured in agar plates, and incubated at 37°C overnight. The number of CFU of E. coli was quantitated and was expressed as the mean ± standard deviation per mouse. E. coli was also cultured with various concentrations of C60 in LB broth. The growth curve of E. coli was determined in LB broth to evaluate the direct antimicrobial activity of C60.

Immunohistochemistry.

Groups of three to four mice were killed by perfusion via cardiac puncture with PBS. The brains were removed and embedded in OCT compound (Miles Inc., Elkhart, Ind.) and were then frozen in liquid nitrogen. Four-micrometer cryosections were made and were fixed with ice-cold acetone for 3 min. They were then stained with a primary rat anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody (MAb; MAb MP6-XT3; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) or a hamster anti-IL-1β MAb (Genzyme, Cambridge, Mass.). Secondary antibodies were peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-rat immunoglobulin G (IgG), goat anti-hamster IgG, or swine anti-goat IgG (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). A peroxidase stain with a reddish brown color was developed with an aminoethyl carbazole substrate kit (ZYMED Laboratories, San Francisco, Calif.) (8).

Detection of increased vasopermeability of BBB by M4 tracer with β-galactosidase activity.

An E. coli mutant (mutant M4) that constitutively expresses β-galactosidase was used as the tracer to detect alterations in the vasopermeability of the BBB. M4 was selected from E. coli K-12 that grew in an M63 culture plate [0.3% KH2PO4, 0.7% K2HPO4, 0.2% (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 mM FeSO4] containing 0.2% lactose, 0.002% vitamin B1, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.001% isoleucine-leucine-valine, and 0.002% 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal). The M4 mutant constitutively expresses β-galactosidase and has a characteristic blue colony on medium containing X-Gal without induction. Preliminary studies have demonstrated that M4 is avirulent (LD50, >2 × 109 cells) to mice and that M4 was rapidly removed from the circulation. It can be used as an inert tracer within 10 min after injection. To each mouse into which E. coli was injected, 2 × 108 cells of the M4 tracer in 0.1 ml were given intravenously 2 min before the mice were killed. The brains were removed, cyrosectioned, and fixed in 0.2% glutaldehyde (Merck GmbH, Parmstadt, Germany). The M4 in the tissues was detected by X-Gal staining (1 mg of X-Gal per ml in 20 mM potassium ferricyanide, 20 mM potassium ferrocyanide, and 2 mM magnesium chloride) at 37°C for 2 h.

RESULTS

Inhibition of experimental E. coli-induced meningitis by C60.

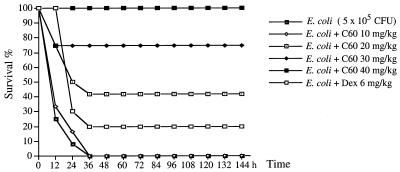

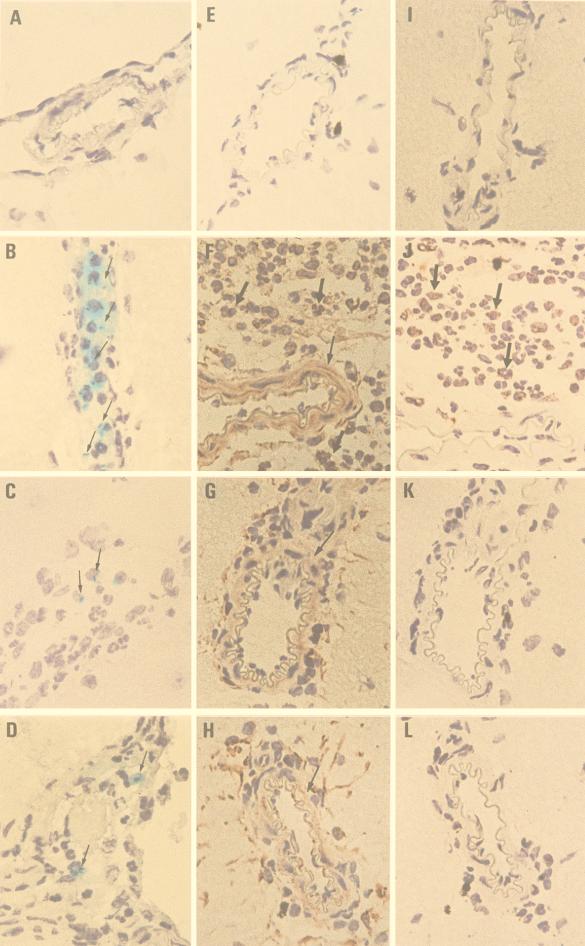

Intracerebral injection of E. coli in B6 mice induced TNF-α and IL-1β production in the brain and recruited neutrophil infiltration into the brain at 6 to 9 h postinjection. The authors were interested in the effect of C60 on the regulation of brain inflammatory responses. Without treatment the mice will die within 36 h of intracerebral injection of 5 × 105 E. coli cells (the LD100 for mice). However, pretreatment of each mouse with 40 mg of C60 per kg i.p. protects the mouse from E. coli-induced death. The inhibition is dose-dependent; 20 mg of C60 per kg protected 40% of the mice, while 30 mg/kg protected 75% of the mice (Fig. 1). This inhibitory effect was better than that of dexamethasone (6 mg/kg), which protected only 20% of the mice. The inhibitory effect of C60 was further studied. As shown in Fig. 2B, the increased vasopermeability of the BBB detected with the M4 tracer was manifested at 24 h in E. coli-treated mice. However, in the C60-pretreated mice, these increases in BBB permeability were inhibited (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the TNF-α and IL-1β staining intensities on arterioles or infiltrating neutrophils were lower in C60-treated mice than in nontreated mice (Fig. 2G and K versus 2F and J). This is consistent with the observation that less neutrophil infiltration occurs in C60-treated mice. Apparently, the C60 treatment decreases the level of cytokine production in the brain, which consequently inhibits the increase in BBB permeability and protects the mice from E. coli-induced death.

FIG. 1.

C60 pretreatment inhibited E. coli-induced death in B6 mice. Groups of 10 B6 mice were inoculated intracerebrally with 5 × 105 E. coli per mouse. Various doses of C60 were administrated i.p. before E. coli injection. Dexamethasone (6 mg/kg of body weight given i.p.) was used as a control treatment. The reagents were given again at 24 and 48 h. The mice were monitored for death every 12 h for 6 days.

FIG. 2.

C60 treatment inhibited the brain inflammation induced by E. coli in B6 mice. Groups of three B6 mice were inoculated intracerebrally with 5 × 105 E. coli cells per mouse, and the mice were killed at 24 h postinjection. (C, G, and K) C60 (40 mg/kg per mouse) was administered i.p. before E. coli injection. (D, H, and L) C60 (40 mg/kg per mouse) was administrated i.p. 6 h after E. coli injection. The M4 tracer (2 × 108 cells in 0.1 ml) was injected intravenously 2 min before the mice were killed. Four-micrometer cryosections of frozen brain tissues were stained with X-Gal (A to D) or anti-TNFα (E to H) and anti-IL-1β (I to L), as described in Materials and Methods. (A, E, and I) Mock control; (B, F, and J) E. coli; (C, G, and K); E. coli and C60 pretreatment; (D, H, and L) E. coli and C60 posttreatment. →, M4 deposition; ➞, arteriole; ➞, infiltrating neutrophil. Magnifications, ×400.

Therapeutic effect of C60 on E. coli-induced meningitis in B6 mice.

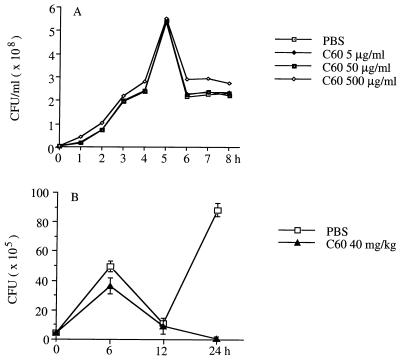

The therapeutic effect of C60 on E. coli-induced meningitis was examined next. As shown in Fig. 3A, the mice died within 36 h after the injection of 5 × 105 E. coli cells. In contrast, intraperitoneal administration of 40 mg of C60 per kg as late as 6 h after E. coli injection protected 80% of the mice from E. coli-induced death. There was still a 50% survival rate if C60 was given at 9 h postinfection. Its protective effect was better than that of dexamethasone, which had only a preventive effect (Fig. 3B). The cytokine expression, increase in BBB permeability, and neutrophil infiltration were also inhibited in the groups treated with C60 postinfection (Fig. 2D, H, and L).

FIG. 3.

Therapeutic effect of C60 on E. coli-induced death in B6 mice. Groups of six B6 mice were inoculated intracerebrally with 5 × 105 E. coli cells per mouse. (A) C60 (40 mg/kg per mouse) was administered i.p. at various times after E. coli injection. (B) Dexamethasone (5 mg/kg of body weight given i.p.) was used as a control treatment. The reagents were given again at 24 and 48 h. The mice were monitored for death every 12 h for 6 days.

Immunomodulatory effect of C60 in the brain.

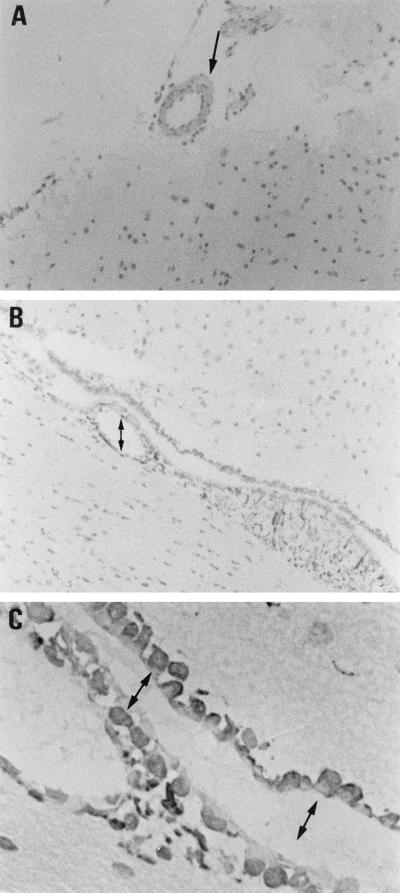

The inhibition of E. coli-induced meningitis by C60 is not due to its direct antimicrobial activity. C60 did not inhibit the growth of E. coli in an in vitro LB broth culture (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the growth of E. coli in the brain after intracerebral injection was determined after C60 treatment. As shown in Fig. 4B, the number of E. coli cells in the brain was not lower in C60-treated mice than in nontreated mice 12 h after intracerebral injection of E. coli. The E. coli cells were cleared from the brain after 24 h in C60-treated mice, while they replicated significantly in nontreated mice, suggesting that C60 might have enhanced the natural antibacterial defenses in the brain. This was supported by the observation that TNF-α expression was found in brain endothelial cells or ependymal cells from naive mice treated with C60 alone (Fig. 5). On the basis of the information presented above, we conclude that C60 may be a therapeutic agent for bacterial meningitis.

FIG. 4.

Effect of C60 on the in vitro and in vivo growth of E. coli. (A) In vitro, E. coli (4 × 106/ml cells) was cultured with various concentrations of C60 in LB broth, and the growth curve was determined with a spectrophotometer. (B) In vivo, groups of three mice were given intracerebral injections of 5 × 105 E. coli cells. C60 (40 mg/kg per mouse) was administered i.p. before E. coli injection. At various times postinjection, the brains were aseptically removed and homogenized, and the numbers of CFU of E. coli were quantitated in an agar plate and are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation per mouse.

FIG. 5.

C60 treatment induced TNF-α expression in the brain. Groups of three B6 mice were inoculated i.p. with C60 (40 mg/kg per mouse) and were killed at 24 h postinjection. Four-micrometer cryosections of frozen brain tissues were stained with anti-TNF-α as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Arteriole (magnification, ×100); (B) ependymal cells (magnification, ×100); (C) ependymal cells (magnification, ×400). ➞, arteriole; ↔, ependymal cells.

DISCUSSION

The pathogenesis of bacterial meningitis is determined by several factors including bacterial load, production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, increased permeability of BBB, and infiltration of inflammatory neutrophils. The pathophysiologic sequelae of meningitis that result from the interaction between the bacteria and the host constitutes a complex cascade. A single intervention is insufficient to halt the disease process, especially from the therapeutic point of view. Studies with adjunctive therapies, including anticytokine drugs, antiinflammatory modulators, and glucocorticosteroids, have shown promising results (21, 30). In this study, it was found that a water-soluble malonic acid derivative of C60 (C3) could interfere with the inflammatory response in experimental E. coli-induced meningitis. C60 not only suppressed cytokine production as well as increased permeability of the BBB, but it also inhibited neutrophil infiltration into the brain. C60 can also modulate the natural antibacterial defense in the brain. Furthermore, C60 is still effective 9 h after E. coli injection, indicating that it can interfere with neutrophil activation.

Fullerenes have attracted much attention since their discovery and large-scale synthesis. Fullerenes have an unique cage structure that allows them to interact with biomolecules and to have avid reactivity with free radicals. These properties of fullerenes have generated great interest in their use in biomedical research (14, 15). It is necessary to convert hydrophobic C60 into water-soluble derivatives before using it as free-radical scavenger or an antioxidant in medical or therapeutic applications. Several strategies have been used to enhance its water solubility and were reported to have protective effects in various systems (4–6, 23, 25, 28). A newly synthesized trimalonic acid derivative of C60, C63[(COOH)2]3, is one of the compounds that not only protected cultured cortical neurons from excitotoxic injury in vitro but that also delayed the neuronal deterioration in a transgenic model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (7, 9, 10, 17). In this study, the authors have demonstrated for the first time that C60 has a protective effect against bacterial meningitis. The C3 regioisomer of C60 can be used as late as 9 h postinjection. The dosage used in this study (40 mg/kg of body weight three times by i.p. injection every 24 h) was far below the toxic dose. The LD50s by i.p. injection in rats and mice are approximately 600 and 1,000 mg/kg of body weight, respectively (3, 29).

The CNSs of mammals are considered to be immunologically privileged sites because of a lack of lymphatic drainage and separation from the blood compartment by the BBB. The BBB, by virtue of its selective permeability, plays an important role in mediating the migration of inflammatory cells into the brain microenvironment (1, 12, 20). Inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 are known to be produced in the cerebrospinal fluid during bacterial meningitis. Their mutual stimulation might be responsible for the alteration of the BBB permeability (11, 22, 24, 26, 27, 31). The increase in BBB permeability also precedes leukocyte migration. It was found that neutralization of the proinflammatory cytokines inhibited the increase in BBB permeability, as well as neutrophil infiltration (unpublished observation). The hydrophobic nature of C60 and its ability to intercalate into biological membranes were found to allow it to penetrate the BBB when it is administered intravenously (33). This unique property of C60 would help to suppress local cytokine production and inhibit the BBB opening, as well as brain inflammation.

The action mechanism of C60 is intriguing. C60 is a potent free-radical scavenger. C60 at the range of 5 to 500 μg/ml tested in the present study did not inhibit the in vitro growth of E. coli. Although the E. coli cells in the C60-treated mouse brain were almost cleared at 24 h after injection, direct inhibition of E. coli growth at early times (12 h before) was not found (Fig. 4B). When C60 was coinjected with E. coli intracerebrally, C60 directly inhibited the local inflammation (unpublished observation). Since the BBB was open during the development of meningitis (Fig. 2), it is possible that C60 would enter the brain via the bloodstream circulation after i.p. administration. C60 was also found to intercalate into the brain lipid membrane (7). This suggests that C60 may suppress cytokine production, inhibit opening of the BBB, and interfere with the neutrophil-mediated inflammatory reaction in the brain. Furthermore, i.p. injection of C60 into naive mice induced increased expression of TNF-α in brain arterioles and ependymal cells (Fig. 5). It seems that C60 can also modulate the natural antibacterial defense to clear the bacteria from the brain. Since the proinflammatory cytokines induced in meningitis interact in a complex cascade, no single intervention is effective. Dexamethasone is used clinically, and it primarily inhibits cytokine production. However, it can only delay or partially inhibit the experimental E. coli-induced death (Fig. 3). C60 is more effective than dexamethasone, probably because of its multiple effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by grant DOH88-HR-717 from the National Health Research Institute of the Department of Health of the Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott N J, Romero I A. Transporting therapeutics across the blood-brain barrier. Mol Med Today. 1996;2:106–113. doi: 10.1016/1357-4310(96)88720-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benveniste E N. Inflammatory cytokines within the central nervous system: sources, function, and mechanism of action. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:C1–C16. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen H H C, Yu C, Ueng T H, Chen S, Chen B J, Huang K J, Chiang L Y. Acute and subacute toxicity study of water-soluble polyalkylsulfonated C60 in rats. Toxicol Pathol. 1998;26:143–151. doi: 10.1177/019262339802600117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiang L Y, Swirczewski J W, Hsu C S, Chowdhury S K, Cameron S, Creegan K. Multi-hydroxy additions onto C60 fullerene molecules. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1992;24:1791–1793. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiang L Y, Upasani R B, Swirczewski J W. Versatile nitronium chemistry for C60 fullerene functionalization. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10154–10157. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dugan L L, Gabrielsen J K, Yu S P, Lin T S, Choi D W. Buckminsterfullerenol free radical scavengers reduce excitotoxic and apoptotic death of cultured cortical neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 1996;3:129–135. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dugan L L, Turetsky D M, Du C, Lobner D, Wheeler M, Almli C R, Shen C K F, Luh T Y, Choi D W, Lin T S. Carboxyfullerences as neuroprotective agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9434–9439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho T S, Tsai C Y, Tsao N, Chow N H, Lei H Y. Infiltrated cells in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by additional intracerebral injection in myelin-basic-protein-sensitized B6 mice. J Biomed Sci. 1997;4:300–307. doi: 10.1007/BF02258354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu S C, Wu C C, Luh T Y, Chou C K, Han S H, Lai M-Z. Apoptotic signal of Fas is not mediated by ceramide. Blood. 1998;91:2658–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Y L, Shen C K F, Luh T Y, Yang H C, Hwang K C, Chou C K. Blockage of apoptotic signaling of transforming growth factor-β in human hepatoma cells by carboxyfullerene. Eur J Biochem. 1998;254:38–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaeschke H, Smith C W. Mechanism of neutrophil-induced parenchymal cell injury. J Leukocyte Biol. 1997;61:647–653. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janzer R C, Raff M C. Astrocytes induce blood-brain barrier properties in endothelial cells. Nature. 1987;325:253–257. doi: 10.1038/325253a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim K S, Wass C A, Cross A S. Blood-brain barrier permeability during the development of experimental bacterial meningitis in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1997;145:253–257. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kratshmer W, Lamb L D, Fostiropoulos K, Huffman D R. Solid C60: a new form of carbon. Nature. 1990;347:354–358. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krusic P J, Wasserman E, Keizer P N, Morton J R, Preston K F. Radical reaction of C60. Science. 1991;254:1183–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5035.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leist T P, Frei K, Kam-Hansen S, Zinkernagel R M, Fontana A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha in cerebrospinal fluid during bacterial, but not viral, meningitis. Evaluation in murine model infections and in patients. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1743–1748. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.5.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin A M Y, Chyi B Y, Wang S D, Yu H H, Kanakamma P P, Luh T Y, Chou C K, Ho L T. Carboxyfullerenes prevent the iron-induced oxidative injury in the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system in rat brain. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1634–1640. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez-Cortes L F, Cruz-Ruiz M, Gomez-Mateos J, Jimenez-Hernandez D, Palomino J, Jimenez E. Measurement of levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 beta in the CSF of patients with meningitis of different etiologies: utility in the differential diagnosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:534–539. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mustafa M M, Ramilo O, Saez-Llorens X, Mertsola J, McCracken G H., Jr Role of tumor necrosis factor alpha (cachectin) in experimental and clinical bacterial meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8:907–908. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198912000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry V H, Anthony D C, Bolton S J, Brown H C. The blood-brain barrier and the inflammatory response. Mol Med Today. 1997;3:335–341. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(97)01077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quagliarello V J, Scheld W M. Treatment of bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:708–716. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703063361007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quagliarello V J, Wispelwey B, Long W J, Jr, Scheld W M. Recombinant human interleukin-1 induces meningitis and blood-brain barrier injury in the rat. Characterization and comparison with tumor necrosis factor. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1360–1366. doi: 10.1172/JCI115140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajagopalan P, Wudl F, Schinazi R F, Boudinot F D. Pharmacokinetics of a water-soluble fullerene in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2262–2265. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramilo O, Saez-Llorens X, Mertsola J, Jafari H, Olsen K D, Hansen E J, Yoshinaga M, Ohkawara S, Nariuchi H, McCracken G H., Jr Tumor necrosis factor α/cachectin and interleukin 1β initiate meningeal inflammation. J Exp Med. 1990;172:497–507. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.2.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satoh M, Matsuo K, Kiriya H, Mashino T, Hirobe M, Takayanagi I. Inhibitory effect of a fullerene derivative, monomalonic acid C60, on nitric oxide-dependent relaxation of aortic smooth muscle. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;29:345–351. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00516-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saukkoneu, K., S. Sande, C. Cioffe, S. Wolpe, B. Sherry, A. Cerami, and E. Tuomanen. The role of cytokines in the generation of inflammation and tissue damage in experimental gram-positive meningitis. J. Exp. Med. 171:439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Sharief M K, Ciardi M, Thompson E J. Blood-brain barrier damage in patients with bacterial meningitis: association with tumor necrosis factor-α but not interleukin-1β. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:350–358. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuchiya T, Oguri I, Yamakoshi Y N, Miyata N. Novel harmful effects of [60]fullerenes on mouse embryos in vitro and in vivo. FEBS Lett. 1996;393:139–145. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00812-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Useng T H, Kang J J, Wang H W, Cheng Y W, Chiang L Y. Suppression of microsomal cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenases and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by fullerenol, a polyhydroxylated fullerene C60. Toxicol Lett. 1997;93:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(97)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Furth A M, Roord J J, Van Furth R. Roles of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in pathophysiology of bacterial meningitis and effect of adjunctive therapy. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4883–4890. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.4883-4890.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waage A, Halstensen A, Shalaby R, Brandtzaeg P, Kierulf P, Espevik T. Local production of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1, and interleukin 6 in meningococcal meningitis. Relation to the inflammatory response. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1859–1867. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang S D, Huang K J, Lin Y S, Lei H Y. Sepsis-induced apoptosis of the thymocytes in mice. J Immunol. 1994;152:5014–5021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamago S, Tokuyama H, Nakamura E, Kikuchi K, Kananishi S, Sueki K, Nakahara H, Enomoto S, Ambe F. In vivo biological behavior of a water-miscible fullerene: 14C labeling, absorption, distribution, excretion and acute toxicity. Chem Biol. 1995;2:385–389. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]