The purpose of this “Technical Article” is to highlight the potential importance of tissue embedding methods for neuropathologic studies. Common preparation methods used for neuropathologic evaluation often involve the study of formalin fixed and paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue, cut and mounted onto glass slides. This basic tissue preparation technique has been used for over a century, but there are differing specific methods, reagents, and machines that are used.

The importance of technical quality for architectural and cytopathologic examination has only increased in recent years. The University of Kentucky Alzheimer’s Disease Center (UK-ADC) Neuropathology Core has decades of experience with brain histopathology and has emphasized the importance of quantitative assessments of histopathologic hallmarks. Recently, at the UK-ADC and elsewhere, a strong focus has been on digital neuropathology [1–8]. Whole slide digital pathologic methods provide rigorous and quantitative histopathologic measurements, but these investigations require high-quality, standardized tissue preparations. Technical artifacts and nonuniform samples are challenging for high-throughput digital analyses after the slides have been scanned, so that methodological optimization may be helpful.

Within the University of Kentucky, both the UK-ADC and the University of Kentucky Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine (UK-DP) perform work involving histopathological preparation of human brain tissue. However, the UK-ADC and the UK-DP are in separate locations and use different biosample processing workflow. Whereas the UK-ADC processes exclusively human brain samples, the UK-DP also processes a heavy clinical load with many other tissue types. While both facilities utilize FFPE, the preparation methods differ.

We recently had the opportunity to assess the processing of the same tissue specimens in parallel, in both facilities. The UK-ADC protocol differs from the UK-PD protocol in several ways. For example, the UK-ADC protocol used Richard-Allan Scientific paraffin Type 9, whereas the UK-PD used Leica EM-400 Embedding Medium paraffin. (Notably, both of these have low melting points in the 55-57°C range.) In the UK-ADC protocol, the tissue is placed into 50/50 Alcoholic formalin before pure alcohol, while in the UK-DP protocol it is not. Also, the UK-ADC uses Xylol 50/50 before emerging the tissue in Xylene, whereas the UK-DP does not. The times spent in each chemical throughout each protocol differs as well. For embedding, the UK-DP uses Thermo Shandon Excelsior ES Processor while the UK-ADC uses the Sakura Tissue-Tek Vscuum Infiltration Processo. Full protocols from both the UK-ADC and UK-DP are attached as supplementary materials.

To evaluate the results of the different embedding protocols, we processed formalin-fixed brain portions (mid-frontal gyrus, Brodmann area 9) from the same two brains, on the same day, using the two different embedding protocols. The specimens’ processing differed in only the embedding methods, because the goal was to elucidate the impact of embedding methods on final slide quality. Thus, after being embedded in FFPE blocks at the different locations, the tissues were cut and stained with H & E in the same batch by the same histotechnologist who was blinded to the study design and the derivation of the the tissue blocks.

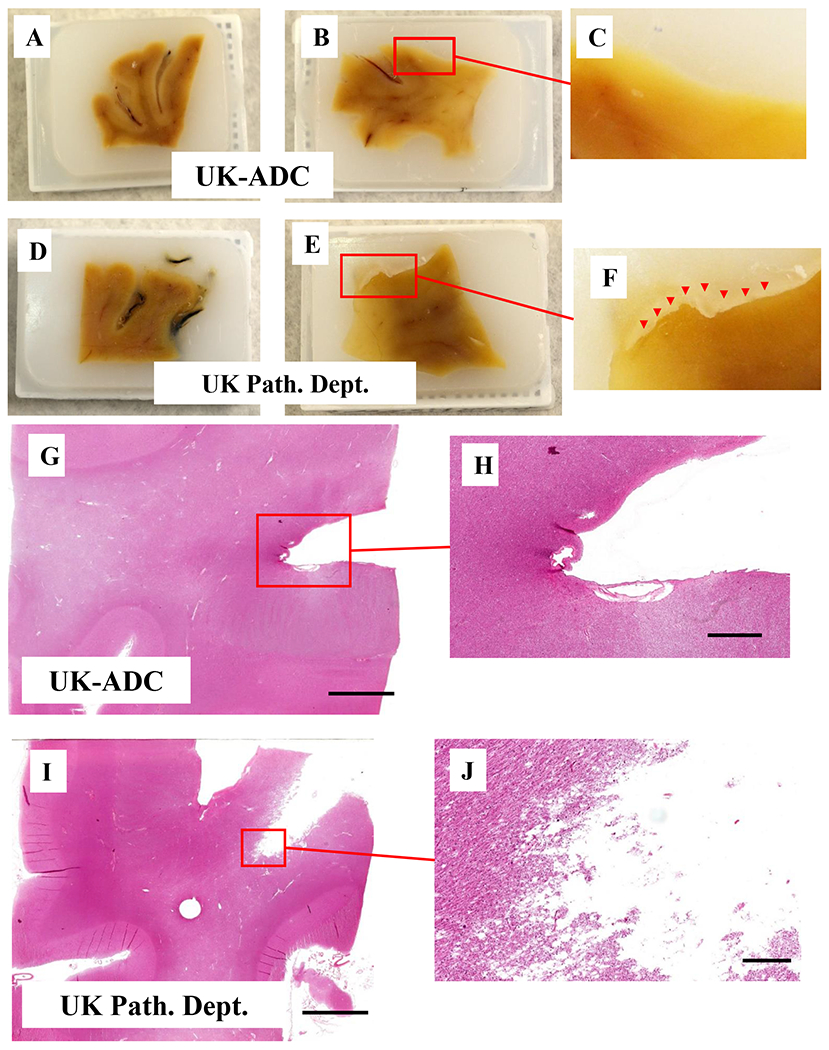

When the tissues were embedded using the routine UK-DP work flow, the edges of the tissue in several of the FFPE blocks showed cracks with clear separation between the tissue and the paraffin. By contrast, the FFPE blocks processed using the UK-ADC protocol showed no gaps where the tissue ended. We hypothesize that such cracking and drying could increase over time if the blocks were archived for future work. The surface of the UK-ADC paraffin block was overall smoother with fewer air bubbles. This appeared to affect the tissue after it was stained. The UK-DP prepared slides had more air bubbles and small tears in the tissue. The tissue on the slide appeared more ragged in comparison to the UK-ADC samples.

We are not implying that all tissue processed through the UK-ADC show near perfect results, nor that the UK-DP blocks are always marred by artifacts. However, we have noticed a consistently high quality in the UK-ADC preparations. We do not know of a published literature that systematically reviews how different procedures at the various stages of tissue processing can impact the quality of the histopathologic preparations in human brain samples. The process used at the UK-ADC has been successful for us, but results may vary in relation to each embedding machine and with other factors. We want to pass along our experience in the hope that it will help others to improve their results.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1. Human neocortical brain tissue embedded in paraffin blocks using different methods.

(A,B,D,E) are at the same magnification (1x). (A, B) Human frontal cortex tissue processed at the U. Kentucky Alzheimer’s Disease Center (UK-ADC). (D) Human frontal cortex tissue; the same brain sample as A, but processed at the U. Kentucky Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine (UK-DP). (B) Human frontal cortex tissue; the same brain sample as B but processed at the UK-DP (F) Higher Magnification of tissue E shows the crack between the tissue and the surrounding paraffin (red triangles). (G-J) Photomicrographs of frontal cortex tissue from the same specimen, stained for H & E. (G,I) are at the same magnification. (G) H & E stained brain tissue that was embedded at the UK-ADC. (H) Higher Magnification of tissue in panel G. (I) H & E stained brain tissue that was embedded at the UK-DP. (J) Higher Magnification of tissue in panel G. Scale bars:G, I: 6mm; H: 2mm; I: 1mm.

References

- [1].Abner EL, Neltner JH, Jicha GA, et al. (2018) Diffuse Amyloid-beta Plaques, Neurofibrillary Tangles, and the Impact of APOE in Elderly Persons’ Brains Lacking Neuritic Amyloid Plaques. J Alzheimers Dis 64: 1307–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bachstetter AD, Ighodaro ET, Hassoun Y, et al. (2017) Rod-shaped microglia morphology is associated with aging in 2 human autopsy series. Neurobiol Aging 52: 98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bachstetter AD, Van Eldik LJ, Schmitt FA, et al. (2015) Disease-related microglia heterogeneity in the hippocampus of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and hippocampal sclerosis of aging. Acta Neuropathol Commun 3: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Nelson PT, Gal Z, Wang WX, et al. (2019) TDP-43 proteinopathy in aging: Associations with risk-associated gene variants and with brain parenchymal thyroid hormone levels. Neurobiol Dis 125: 67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Neltner JH, Abner EL, Baker S, et al. (2014) Arteriolosclerosis that affects multiple brain regions is linked to hippocampal sclerosis of ageing. Brain 137: 255–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Neltner JH, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, et al. (2012) Digital pathology and image analysis for robust high-throughput quantitative assessment of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 71: 1075–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Signaevsky M, Prastawa M, Farrell K, et al. (2019) Artificial intelligence in neuropathology: deep learning-based assessment of tauopathy. Lab Invest. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tang Z, Chuang KV, DeCarli C, et al. (2019) Interpretable classification of Alzheimer’s disease pathologies with a convolutional neural network pipeline. Nat Commun 10: 2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.