Abstract

This study reviewed social support research with refugees in resettlement by assessing the scope of scholarship and examining methodological approaches, definitions, theoretical frameworks, domains, and sources of support. The scoping review followed a systematic approach that retained 41 articles for analysis. The findings indicate that refugee resettlement studies seldom conceptualizes social support as a central focus, defines the concept, draws from related theory, or examines multifaceted components of the construct. The review nevertheless yielded promising findings for future conceptual and empirical research. The analysis identified a wide range of relevant domains and sources of social support, laying the foundation for a socio-ecological model of social support specific to refugee experiences in resettlement. The findings also indicate an imperative to examine and theorize social support vis-à-vis diverse groups as a main outcome of interest, in connection to a range of relevant outcomes, and longitudinally in recognition of the temporal processes in resettlement.

Keywords: social support, social networks, social connections, social determinant of health, integration, ecological model

Introduction

The impact of armed conflict and political instability on individuals, families, and communities is an escalating global reality with one in seven individuals living in conflict-affected countries (UNHCR 2019). More than 75 million people are forcibly displaced from their homes worldwide, one-third of whom are registered as refugees across international borders (UNHCR 2019). A small percentage of people with refugee status resettles to a third country that provides permanent residence status and the opportunity to naturalize.

War, displacement, and resettlement contribute to systematic and sustained ruptures to interpersonal networks. In addition to causing the death of loved ones, forced migration separates families and dismantles communities. These consequences are particularly salient for people who resettle from contexts in which interpersonal relationships shape all aspects of daily life and means for getting by (Rees and Pease 2007; Miller and Rasmussen 2010). The resulting short- and long-term losses of social support compound risks for adverse health outcomes (Casimiro et al. 2007; Silove et al. 2017; Weissbecker et al. 2019).

At its essence, social support refers to the support available through interpersonal connections, which scholars have described in various ways. For example, Cobb (1976) defined social support as a function of network membership and mutual obligation that cultivates the belief that one is loved and valued, while House (1981) defined social support as an interpersonal transaction. Additionally, Cohen and Syme (1985) framed social support as resources provided by other persons, while Gottlieb (1978) defined it as informal helping behaviors. Indeed, some definitions differentiate social support as the assistance and help available through informal networks (i.e. personal connections with family, friends, neighbors, colleagues, etc.) versus from formal networks of service providers and helping professionals. Drawing on this foundation, social support is typically operationalized in research using categories of emotional, instrumental, informational, and less frequently, appraisal support.

The literature describes the construct of social support as multifaceted (Hupcey 1998a, 1998b), contextual (Williams et al. 2004), and functioning at various levels of social ecology (Barrera et al. 2006). The availability of social support depends on multiple personal and environmental factors (Gottlieb and Bergen 2010). Social support intertwines with notions of self, self-esteem, and identity (Cobb 1976; Thoits 1985), belonging and connectedness (Thoits 1985), intimacy and attachment (Berkman 2000; Sarason and Sarason 1990), as well as isolation and loneliness (Weiss 1973). Furthermore, cultural meanings, expressions, and expectations of support shape what individuals and groups consider supportive (Stewart et al. 2008).

A robust body of inter-related work spanning numerous disciplines informs the study of social support, including theories of social capital (Portes 1998), social networks (Berkman et al. 2000), stress and coping (Lazarus and Folkman 1984), and social integration (Ager and Strang 2008), among others. As a subset of a broader field concerned with human relationships and social cohesion, social support scholarship has drawn primarily from stress buffering and main effect theories that conceptualize social support as a social determinant of physical and mental health. Stress buffering theory maintains that social support functions to moderate stress and promote coping in times of adversity (Cobb 1976; Cohen and Wills 1985). The main effect model posits that social support has continuous and direct benefits to well-being by fulfilling the basic constant social needs of individuals (Thoits 1982). Yet, questions remain regarding the extent to which social support theories inform research with refugees in resettlement contexts. Indeed, most of the theories explaining social support were developed through the lived experiences of other populations, with no direct bearing on refugees in resettlement.

Empirical studies have also examined social support across populations (e.g. elderly, new mothers, caregivers) and circumstances (e.g. end of life, poverty, domestic violence, pregnancy), with limited consideration of refugees in resettlement. The research literature now highlights a predominantly positive relationship between social support and key outcomes including physical health (Holt-Lunstad et al. 2010; Uchino et al. 2012; Faw 2018), mental health (Tezci et al. 2015; Gariépy et al. 2016; Jibeen 2016), nutrition (Debnam et al. 2012), and other important outcomes related to well-being. It therefore follows that research concerned with the well-being of refugees who resettle to a third country should address cumulative losses and heightened needs for social support, by building a robust evidence base to inform policy and practice. However, the extent to which research with refugees in resettlement comprehensively conceptualizes social support remains unclear.

This scoping review seeks to advance scholarship concerned with people whose needs for social support are shaped by forced migration and resettlement. We designed this study to gain a comprehensive understanding of the current state of social support research in the context of resettlement by assessing the scope of relevant studies, examining methodological approaches, assessing definitions and theoretical frameworks, and examining contextually relevant facets of social support. By identifying gaps and opportunities presented in the literature, our ultimate aim is to advance conceptual and empirical work necessary for addressing challenges refugees face in resettlement that are fundamentally social and relational in nature.

Methods

Scoping reviews identify the nature and extent of available evidence for preliminary assessment (Turenne et al. 2019). The methodological approach to the current study drew from Arksey and O'Malley’s (2005) framework for scoping reviews, which include the following steps: (1) Articulate research questions; (2) identify relevant studies; (3) select eligible studies; (4) chart data; and (5) synthesize and analyze findings.

Two research questions guided our scoping review of the English language and peer-reviewed literature: (1) What is the current state of social support research with refugees in resettlement? (2) How do studies conceptualize or theorize social support?

To identify relevant studies for our review, we followed established guidelines in designing and conducting the literature search. We identified eight databases to target in our search: PsycINFO, Cochrane, Social Services Abstracts, PubMed, Sociological Abstracts, CINAHL, and Web of Science. We developed search term categories and expanded each category with relevant corresponding terms during an initial pilot phase to formulate our search string as follows: (‘social support’ OR ‘psychosocial support’ OR ‘support system’ OR ‘informal support’ OR ‘emotional support’ OR ‘practical support’ OR ‘informational support’ OR ‘appraisal support’ OR ‘social capital’ OR ‘social networks’ OR ‘social connection’ OR isolation) AND (refugee* OR ‘asylum seeker’ OR asylee* OR immigrant* OR migrant*) AND resettle* AND (health OR well-being OR integration OR acculturation). In order to capture the breadth and evolution of social support as a construct, we did not limit the year of publication for the search.

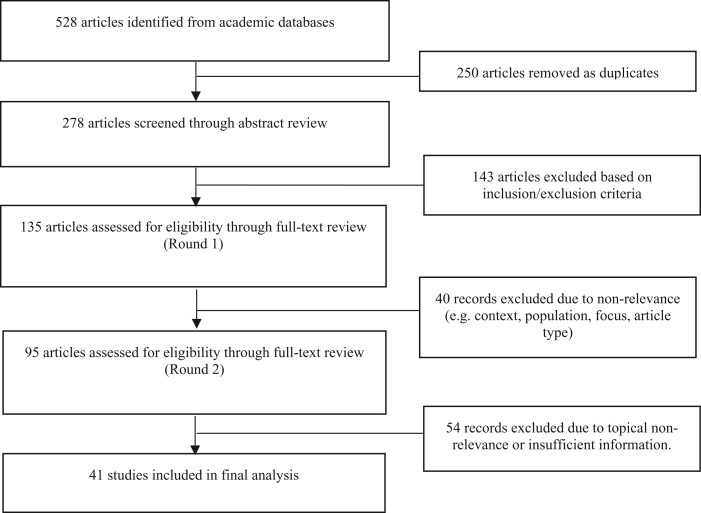

We carried out the literature search in March and April in 2019. Using the reference management software, Zotero, we downloaded all citations from each database into a group library, organized by database. This process yielded 528 articles. Then we combined all of the database folders into a master folder in which we identified and deleted 250 duplicate articles. This process resulted in a remaining 278 articles. We organized these entries alphabetically by author and divided them into four folders, which we assigned to four analysts.

Four analysts reviewed a total of 278 article abstracts to assess for inclusion and exclusion. We included original research articles (no reviews) that (1) comprised refugees in the sample, (2) took place in a resettlement context, and (3) studied social support as defined as support available through interpersonal connections. Then, another member conducted a second review of all abstracts to confirm decisions for retention based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Analysts brought any discrepancies between the two reviews to the lead author to discuss and resolve. We excluded 143 articles during the abstract review phase and moved 135 articles forward to the subsequent phase of full-text review.

For the full-text review, we charted preliminary findings for the remaining articles in a spreadsheet. Four analysts entered data from each article assigned to them, noting when they recommended elimination based upon revelation of additional information pertaining to the inclusion or exclusion criteria. A fifth analyst thoroughly reviewed all articles to ensure systematic application of criteria, made revisions, and generated additional recommendations for inclusion or exclusion. This first round of the full-text review process excluded 40 of 135 articles. Three researchers conducted another round of full-text reviews with the 95 remaining articles and eliminated an additional 54 due to insufficient information on social support, resulting in 41 articles for the final analysis. Refer to Figure 1 for details.

Figure 1.

Systematic search and article review process.

To examine conceptualizations of social support, we drew from content analysis techniques (Hsieh and Shannon 2005), which necessitated multiple and extensive reviews of each article. First, to examine the design of social support research with refugees in resettlement, we conducted an in-depth examination of study aims and research questions stated in each article. Second, to understand how and the extent to which studies delineated and theorized social support, we searched the literature reviews and methods section of each article to identify explicit definitions and theories of social support. Third, to assess types of social support included in these studies, we analyzed domains (categories) and dimensions (range of meanings) of social support types, drawing in part from descriptions of measures. We assessed and identified domains and dimensions using an inductive approach versus drawing explicitly from theory, which opened the possibility for detecting emergent categories. The approach privileged identifying potentially distinct categories salient to resettlement experiences over combining types of social support under broad domains of support. Fourth, using a similar inductive approach, we analyzed sources of social support, from whom or where support derived, and then categorized those sources into systems of inter-related sources of support. Although a useful distinction, we elected not to label sources as formal (e.g. professional) or informal (e.g. friend) in acknowledgement that these distinctions are subjective and easily blurred in the early phases of resettlement (Wachter et al. 2021). To maximize accuracy at each step in the analytical process, the first two authors carried out these analyses independently of one another, compared results, and discussed and resolved discrepancies with other team members. All analyses were conducted in Google Sheets.

Findings

This section reports findings from the analysis as follows: (1) study descriptives, (2) social support in research design, (3) definitions and theories of social support, (4) domains and dimensions of social support, and (5) sources and systems of social support.

Study Descriptives

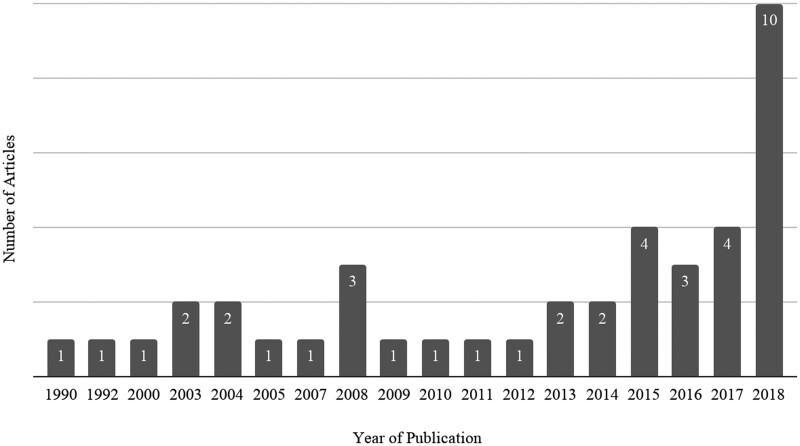

Across the 41 articles, research took place in six refugee resettlement countries. The majority of studies were conducted in the United States (56%), followed by Australia (20%), Canada (17%), Norway (2%), Sweden (2%), and New Zealand (2%). Nearly 70% included participants from a single country of origin; the rest included samples from multiple countries (range: 2 to >40). Afghanistan, Sudan or South Sudan, and Bhutan represented most frequent countries of origin, followed by Iraq, Burundi, and Burma/Myanmar. All countries of origin had experienced armed conflict and political instability in recent history. The majority of studies (80%) included only adult participants, while 15% included a mixed sample of both children/adolescents and adults and 5% focused singularly on children. Eighty-three percent of studies recruited mixed gender samples (female/male), 12% exclusively recruited female participants, and 5% included only males. Studies with mixed samples did not offer analyses based on gender or developmental phase. Although the analysis included articles published as early as 1990, the majority (78%) were published between 2008 and 2018, with an observable trend toward increased attention to this topic starting in 2017 as indicated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Year of Publication* (n = 41).

*Through April 2019.

Social Support in Research Design

Table 1 highlights the conceptualization of social support in research design per study. Of the studies included in this analysis, 46% were quantitative, 34% were qualitative, and 20% employed both quantitative and qualitative methods. The majority of studies were cross-sectional and did not appear to adjust their examinations of social support according to where refugees were in the resettlement process.

Table 1.

Key Characteristics of Studies Organized by Authors and Methodological Approach (n = 41)

| Authors | Year | Resettlement country | Countries of origin | Methoda | Social support (SS) in research design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agbenyiga et al. | 2012 | U.S. | Burma and Burundi | Qual | SS studied in relation to successful resettlement and as differing across groups. |

| Aroian | 1992 | U.S. | Poland | Qual | Shifts in SS studied longitudinally over 3 stages of resettlement |

| Barnes and Aguilar | 2007 | U.S. | Cuba | Qual | SS studied as practical, informational, and affect support from the social environment. |

| Khawaja et al. | 2008 | Australia | Sudan | Qual | SS studied inductively as a coping strategyb. |

| Liamputtong et al. 2016 | 2016 | Australia | South Sudan, Burma, Afghanistan, | Qual | SS studied as a health enhancing strategy and a form of empowerment occurring among participants in peer support groups. |

| Liamputtong and Kurban | 2018 | Australia | Iraq, Syria, Iran | Qual | SS studied inductively as contributing to health, well-being, sense of belonging, and adaptation. |

| Mitschke et al. | 2017 | U.S. | Five countries | Qual | SS studied inductively as a benefit/preference of group-based mental health interventions. |

| Rahapsari and Hill | 2019 | U.S. | Burma | Qual | SS conceptualized as promoting resilience following trauma and during adjustment and integration in resettlement. |

| Savic et al. | 2013 | Australia | Sudan | Qual | SS studied inductively in the context of separation from family and loved ones. |

| Shrestha-Ranjit et al. | 2017 | New Zealand | Bhutan | Qual | Lack of SS studied inductively as a source of mental distress. |

| Simich et al. | 2003 | Canada | >10 countries | Qual | SS studied as a determinant of refugee well-being and secondary migration patterns in resettlement. |

| Stewart et al. | 2008 | Canada | China and Somalia | Qual | SS studied as culturally specific and essential in early phases of resettlement. |

| Wachter and Gulbas | 2018 | U.S. | DRC | Qual | Changes in SS due to war, displacement, and resettlement studied as a psychosocial process affecting the health and well-being of women. |

| Weine et al. | 2014 | U.S. | Burundi, Liberia | Qual | SS studied as a protective factor against psychiatric disorders. |

| Baranik et al. | 2018 | U.S. | >10 countries | Multi | SS studied inductively as a refugee-specific coping mechanism. |

| Colic-Peisker | 2009 | Australia | Three regions | Multi | SS studied as a predictor of life satisfaction. |

| Drolet and Moorthi | 2018 | Canada | Syria | Multi | SS studied using social participation measures. |

| Gerber et al. | 2017 | U.S. | Bhutan | Multi | SS studied as an outcome of a community gardening intervention. |

| Goodkind et al. | 2014 | U.S. | Five countries | Multi | SS studied as a mediator of psychological well-being and quality of life. |

| Hagaman et al. | 2016 | U.S. | Bhutan | Multi | Lack of SS studied as a post-migration challenge that exacerbates risks of mental illness. |

| Simich et al. | 2010 | Canada | Sudan | Multi | SS studied as a quality of home missing in resettlement and important to mental health. |

| Walker et al. | 2015 | Australia | Sudan, Burma Afghanistan | Multi | SS studied as a social determinant of mental, physical, and social health. |

| Alemi et al. | 2015 | U.S. | Afghanistan | Quant | SS studied as a predictor of psychological distress. |

| Alemi et al. | 2017 | U.S. | Afghanistan | Quant | SS studied as a post-migration adjustment factor and a buffer of perceived discrimination and psychological distress. |

| Alemi and Stempel | 2018 | U.S. | Afghanistan | Quant | SS studied as a post-migration adjustment factor and a buffer of perceived discrimination and psychological distress. |

| Anderson et al. | 2014 | U.S. | Sudan | Quant | SS studied as related to household food insecurity. |

| Ao et al. | 2016 | U.S. | Bhutan | Quant | Low SS studied as a risk factor associated with suicidal ideation. |

| Benson et al. | 2012 | U.S. | Bhutan | Quant | SS studied as a predictor of environmental acculturation stress. |

| Franks and Faux | 1990 | Canada | Five countries | Quant | SS studied as a social resource that mediates stress and depression. |

| Ghazinour et al. | 2004 | Sweden | Iran | Quant | SS studied as a coping behavior and closely related to quality of life and psychological well-being. |

| Hanley et al. | 2018 | Canada | Syria | Quant | SS studied in conjunction with social networks and capital to assess how social connections helped in terms of housing and employment. |

| Johnson and Stoll | 2008 | Canada | Sudan | Quant | SS studied as predicting men’s perceived emotional and financial strain associated with being a global breadwinner. |

| Kingsbury et al. | 2019 | U.S. | Bhutan | Quant | SS studied as mitigating stress related to refugee experiences, including resettlement, and as playing an important role during pregnancy. |

| Kovacev and Shute | 2004 | Australia | Former Yugoslavia | Quant | SS studied as related to global self-worth and peer social acceptance (psychosocial adjustment). |

| Lemaster et al. | 2018 | U.S. | Iraq | Quant | SS studied as a post migratory stressor and potential mediator of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. |

| Lumley et al. | 2018 | Australia | Bhutan | Quant | SS studied as inversely associated with psychological distress, and a moderator of the relationship between acculturative stress and psychological distress. |

| Oppedal and Idsoe | 2015 | Norway | Four countries | Quant | SS studied as a predictor (main effect) of acculturation, discrimination, and mental health. |

| Salo and Birman | 2015 | U.S. | Vietnam | Quant | SS studied as predicted by acculturation, a predictor of less psychological distress, and a mediator of the relationship between acculturation and distress. |

| Takeda | 2000 | U.S. | Iraq | Quant | SS studied as a predictor of psychological and economic adaptation. |

| Trickett and Birman | 2005 | U.S. | Former Soviet Union | Quant | SS studied as a predictor of school outcomes. |

| Weine et al. | 2003 | U.S. | Kosovo | Quant | SS studied as a key outcome of a family-based intervention focused on mental health. |

Qual = Qualitative, Multi = Multi-methods, Quant = Quantitative.

Inductively refers to instances in which social support was not included in the original design but arose inductively in data collection and analysis.

Of the 14 studies that qualitatively investigated social support among refugees in resettlement, half prioritized social support as a primary focus or main outcome of interest. These seven studies reflected intentional and systematic ‘deep dives’ into social support from the perspectives of refugees in resettlement (Aroian 1992; Simich et al. 2003; Barnes and Aguilar 2007; Stewart et al. 2008; Agbenyiga et al. 2012; Liamputtong et al. 2016; Wachter and Gulbas 2018). These articles highlighted the extent to which social support relates to notions of self and ways of life. These articles also drew attention to changes in social support due to shifts in geographic, cultural, and political contexts, as well as shifting meanings of social support based on cultures of origin and changes in context. They revealed important temporal considerations in the study of social support among refugees in resettlement, such as how needs shift over time and in various phases of resettlement, and expectations and values associate with social support prior to resettlement.

Our analysis indicated that 27% of qualitative and/or multi-methods studies did not include social support as an a priori concept in the study design. In these studies, social support emerged inductively from the analysis of qualitative data and yielded relevant information as part of the findings. In these studies, social support was found to be important for coping with resettlement, health, and well-being. Such studies also found that losses and shifts in social support were important for understanding problems with mental health, acculturation, and adjustment.

Multi-methods and quantitative studies examined associations between social support and other variables relevant to refugee resettlement. In studies that used quantitative measures of social support, social support was most frequently conceptualized as an independent variable (55%), followed by moderator or mediator (32%), and dependent or outcome variable (27%).

Studies that conceptualized social support as a mediator hypothesized social support as mediating associations between psychological well-being and quality of life (Goodkind et al. 2014), stress and depression (Franks and Faux 1990), acculturation and adjustment (Kovacev and Shute 2004), and acculturation and psychological distress (Salo and Birman 2015). In contrast, studies hypothesizing a moderating role conceptualized social support to moderate the relationships of perceived discrimination to psychological distress (Alemi et al. 2017; Alemi and Stempel 2018), as well as acculturative stress to psychological distress (Lumley et al. 2018).

Social support was typically studied in conjunction with more than one other construct. Frequencies of related constructs were: mental health-related outcomes (n = 15), followed by acculturation, adjustment, and adaptation (n = 8), resettlement and integration (n = 5), well-being (n = 5), health-related outcomes (n = 4), social connections and social contact (n = 4), life satisfaction and quality of life (n = 3), discrimination (n = 3), and economics and financial strain (n = 2). Other outcomes that only appeared in one article included employment, belonging, coping, family processes, food insecurity, housing, self-worth, resilience, and experiences (unspecified).

Definitions and Theory

The analysis identified definitions of social support in 39% of studies (see Table 2). We identified three categories of definitions from our analysis, although elements of some definitions spanned more than one category. In the first category, definitions described the availability of practical, emotional, and informational support available through relationships. The second group of definitions highlighted interpersonal interactions as expressions of support themselves. Definitions in this category point to interactions with members of formal and informal networks of relationships as the conduit driving social support, which is in contrast to the first category in which relationships are a means to obtain support. The third group focused on perceptions of support should needs arise. The definition used by Salo and Birman (2015) defined social support as socially mediated coping was an outlier definition. Liamputtong et al. (2016) employed a definition of peer support reflective of a related but distinct construct.

Table 2.

Definitions of Social Support Detected in Studies (n = 16)a

| Authors | Year | Definitions | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aroian | 1992 | ‘Provisions from social relationships that meet instrumental or emotional needs (Thoits 1982; Jacobson 1986)’ (p. 178). | Support available through relationships |

| Simich et al. | 2003 | ‘Informational, instrumental, and emotional help (House 1981)’ (p. 874). | |

| Agbenyiga et al. | 2012 | ‘Impact of newly formed interpersonal relationships on resource acquirement’ (p. 310). | |

| Wachter and Gulbas | 2018 | ‘Support available through functioning social networks’ (p. 108). | |

| Walker et al. | 2015 | ‘Social support (interpersonal connectedness) as the interpersonal interactions that provide practical and emotional resources’ (p. 326). | |

| Franks and Faux | 1990 | ‘Structural measures have been used to describe the existence of relationships while functional measures have been used to disclose the emotional, informational, or tangible benefits of relationships (Cohen and Willis 1985)’ (p. 285). | |

| Kingsbury et al. | 2019 | ‘Obtaining emotional support, financial assistance, advice, companionship, a sense of belonging (Stewart 2008), and the provision of tangible aid in time of need from another or a group of others (Kahn, 1979)’ (p. 837). | |

|

| |||

| Hanley et al. (2018) | 2018 | ‘The interaction with family members, friends, peers and professionals that communicate information, esteem, practical, or emotional help (Stewart and Lagille 2000: 5)’ (p. 126). | Interactions and expressions |

| Takeda | 2000 | ‘Assuring, listening, and discussing problems; emotional expressions of love, interest, concern, and anger; a safety net’ (p. 7). | |

| Kovacev and Shute | 2004 | ‘The positive regard received from others (Harter 1985)’ (p. 261). | |

| Barnes and Aguilar | 2007 | ‘The interactional approach to social support defines support as a complex transactional process between the person and his or her social environment (Pierce et al. 1997)’ (p. 226). | |

| Oppedal and Idsoe | 2015 | ‘The presence of social supportive relationships’ (p. 204). | |

| Lumley et al. | 2018 | ‘The subjective assessment that effective support will be offered from social sources at a time of need (Gurung 2013)’ (p. 1271). | Perceptions of support |

| Ghazinour et al. | 2004 | ‘The essence of social support is the conviction that somebody values and cares about a person and is ready to help when the needs come up (Sarason and Sarason 1990; Pierce et al. 1991)’ (p. 72). | |

|

| |||

| Salo and Birman | 2015 | ‘Socially mediated coping (Gottlieb, 1988)’ (p. 398). | Other |

| Liamputtong et al. | 2016 | ‘Peer support is [defined] as a subset of social support in which the relationships are formed between individuals who are similar to each other’ (p. 716). | |

Number of studies in which explicit definitions of social support were apparent.

Studies that included quantitative measures of social support provided insights into the operationalization of social support for measurement (e.g. satisfaction with support, perceived social support) but not how the construct was defined. Details regarding measurement varied considerably across studies; some studies revealed disconnects between constructs (e.g. social support) and measurement (e.g. social participation measures). Moreover, some studies leaned toward structural elements of social support (e.g. living with family, having at least one friend, size, closeness, and frequency of contacts) versus measures of perceived or received support. Other studies sought to measure adequacy, satisfaction, and/or quantity (frequency) of support, and still others emphasized the reliability of (perceived) support and the importance of source proximity (i.e. having people close by). These examples reflected social network approaches concerned with size, closeness, and frequency of contacts.

Almost half (47%) of studies stated drawing from specific theories or extant theoretical frameworks. Twelve studies referenced social support theory or frameworks, half of which related to stress buffering theory of social support; others drew from broad frameworks of social support steeped in the literature, including social comparison theory, and two articles referenced the main effect theory of social support. Stewart et al. (2008) situated their study in a theoretical framework highlighting dimensions of social support, impacts on health, and support seeking as a coping strategy. A grounded theory study produced an explanatory model to theorize systematic losses of social support among women due to forced migration and resettlement, contributing to theory development specific to the experience of refugees (Wachter and Gulbas 2018). Over half of the studies included in this analysis did not state a theoretical foundation, social support or otherwise.

Domains and Dimensions of Social Support

As indicated in Table 3, we identified 10 different domains of support with multiple dimensions per most domains. Most studies (66%) addressed an average of two domains per study (range: 0–7). Across studies, practical support (also referred to as instrumental, physical, tangible, material, financial, and resource support or aid) was the most frequently studied domain of social support and frequently studied in conjunction with other types of social support. The analysis identified emotional support (also referred to as psychological support) in over half of all studies; the dimensions of which highlighted variations in meanings specific to resettlement. Attachment support (also referred to as affective support) appeared in roughly 30% of studies and referred to social support needs relative to forced migration and resettlement, which upend social relationships and leave people feeling untethered and disconnected, as reflected in dimensions such as connectedness, mutuality, and trust. Advice and guidance appeared as important dimensions of informational support, detected in 27% of studies, which may reflect needs shaped by cultural expectations (i.e. asking elders for advice) and context (i.e. heightened needs for guidance in resettlement contexts). Affirmational support (also referred to as self-esteem, esteem, appraisal support), amplified by resettlement, in which usual systems for affirming identity and self-worth may be absent.

Table 3.

Domains and Dimensions of Social Support (n = 41)

| Domains | Frequencya (%)b | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|

| Practical support | 25 (60%) | Material goods, translation, transportation, assistance with paperwork, credit backing, childcare, mutual aid, employment, language, literacy training, access to care, transportation, loaning money and tools, accommodation, and household repairs, help with public programs, jobs, money, health care, good, borrowing or lending items |

| Emotional support | 19 (54%) | Expressions of empathy and caring, having someone to talk to about one’s problems, parents listening to children’s problems and caring about their feeling, help with personal problems and private matters, understanding, having a confidante with whom to share private thoughts, friends with whom to talk about important things, encouragement. |

| Attachment support | 13 (30%) | Feeling connected, closeness, intimacy, attachments, strong co-ethnic bonds, mutuality, feelings of closeness, trust |

| Informational support | 9 (27%) |

Information regarding finding places and consumer goods, driving a car, securing jobs, basic English; advice about financial and social matters, subtle cultural differences, complex English, other immigrants’ adjustment, information, advice, guidance |

| Affirmational support | 9 (22%) | Information for self-appraisal, identity, comparisons of self with others, reassurance of worth (positive evaluation), reaffirmation of heritage, feeling respected |

| Companionship support | 8 (20%) | Gathering together, positive interactions, talking and sharing, getting together outside one’s home, exchanging ideas, participating in sports, physical and educational activities, doing activities together, not feeling alone, lonely, or isolated, having friends, making friends, having friends in reach, seeing and talking to friends from co-ethnic community. |

| Sense of belonging | 2 (5%) | Feeling accepted, belonging to a group of similar others |

| Affection | 1 (2%) | Expressions of love, feeling cared for |

| Adjustment support | 1 (2%) | Help with feeling settled |

| Sense of safety/refuge | 1 (2%) | None provided |

Number of articles in which domains were apparent. Dimensions varied for each domain in different articles.

Percentage of articles in which the domain was apparent.

The analysis identified the domain of companionship support in 17% of studies. The dimensions that arose from the articles highlight enriched descriptions of companionship and social interactions especially significant for people adjusting to life in resettlement, such as getting together outside one’s home and doing activities together. Other types of social support, described in the articles as sense of belonging, affection, adjustment support, and sense of safety and refuge, were infrequent but no less relevant to people undergoing dramatic changes in all aspects of life and separated from loved ones.

Sources and Systems of Social Support

The analysis revealed 37 distinct sources of support (see Table 4). Most studies examined several different sources of support (range: 1–6) with an average of approximately three different sources of support per study. Sources comprised individuals (e.g. friend, peer, teacher), groups (e.g. family, co-ethnic community, peer network), and organizations (e.g. ethnic organizations, resettlement agencies, churches). The three most frequent sources of support were family, friends, and co-ethnic community and all remaining sources of support were examined in four or less studies. We grouped the sources into eight systems of support: community, family, social service, refugee resettlement, faith/religious, school, neighborhood, and government systems. Fifteen per cent of studies examined sources of support that corresponded with only one system, while 85% examined sources of support in two or more systems. Community and family systems were studied in combination in 51% of studies. Both informal and formal (professionalized) sources of support appeared in most systems (e.g. neighbors and libraries in the neighborhood system). The religious/faith system was only included in studies of Christian refugee populations, despite the fact that study populations in this review were diverse in terms of religious orientation. The analysis of systems and sources of support indicated that potential sources of support in resettlement contexts are diverse and cut across multiple systems.

Table 4.

Sources of Social Support by Frequency and System (n = 41)

| Sources of social support | Frequencya | Systemb |

|---|---|---|

| Friends (unspecified) | 19 | Community (n = 33, 80%) |

| Co-ethnic community | 9 | |

| Community (unspecified) | 4 | |

| Co-ethnic friends | 2 | |

| Peers (unspecified) | 2 | |

| Host friends | 2 | |

| Host community | 2 | |

| Refugee community | 2 | |

| Other immigrants | 1 | |

| Refugee peers | 1 | |

| Co-ethnic peers | 1 | |

| Host community peers | 1 | |

| Community groups | 1 | |

| Ethnic organizations | 1 | |

|

| ||

| Family (unspecified) | 23 | Family (n = 26, 63%) |

| Spouse/intimate partner | 2 | |

| Out of household family/extended family | 2 | |

| Foster/Surrogate family | 1 | |

| Transnational family | 2 | |

| Parents | 1 | |

| Local family | 1 | |

|

| ||

| Professionals/service provider | 4 | Social services (n = 7, 17%) |

| Social services | 2 | |

|

| ||

| Resettlement agency | 3 | Refugee resettlement (n = 6, 15%) |

| Resettlement staff | 2 | |

| Sponsors | 1 | |

| Refugee-serving agency | 1 | |

| Faith-based organizations | 1 | |

|

| ||

| Church | 3 | Faith/religious (n = 5, 12%) |

| Church staff | 1 | |

| Church congregants | 1 | |

| Religious leaders | 1 | |

| Students/classmates | 2 | |

| Teachers | 1 | |

|

| ||

| Students/classmates | 2 | School (n = 3, 7%) |

| Teachers | 1 | |

|

| ||

| Neighbors | 1 | Neighborhood (n = 2, 5%) |

| Neighborhood resources (i.e. groups, libraries, community centers) | 1 | |

| Government programs | 1 | Government (n = 1, 2%) |

Number of articles in which specific sources of support were apparent.

Number of articles in which specific systems of support were apparent based on analysis of sources.

Discussion

This review scoped the refugee resettlement literature to assess the breadth and depth of social support-related scholarship. This section discusses emergent issues detected by the current analysis and then presents specific implications for conceptual and empirical work moving forward.

Emergent Issues

The findings suggest that social support is a relatively untapped concept in refugee resettlement research. The analysis detected an overarching tendency in individual studies to simplify a multidimensional construct and relegate social support to a minor role, suggesting dissonance between the significance of social support in the lives of people who resettle as refugees and the research designed to deepen understanding of their experiences. While the aims of any one study may lend themselves to specific aspects of social support, conceptualizations in this analysis appeared to favor parsimony over complexity, potentially at the expense of meaning and relevance. Historically, the oversimplification in operationalizing social support for the purposes of data collection and analysis has been an issue in the broader literature as well (Barrera 2000).

Most studies included in this review did not critically engage with or theorize social support as a concept integral to research concerned with refugee well-being. In line with stress buffering and main effects theories that conceptualize social support as an independent or moderating variable (Lakey and Orehek 2011), the majority of quantitative studies in this analysis examined social support in relation to mental health and did not center social support as the primary research focus or outcome variable. It is important to note that most of these articles included help-seeking samples, whose needs are likely distinct from broader (non-clinical) samples. Certainly, research in this vein addresses vital functions of social support as a social determinant of health (Green et al. 2019; Umberson and Karas Montez 2010) and an integral concept in intervention work (Bunn and Marsh 2019). Yet, conceptualizing social support in a supporting role in relation to other outcomes contributes to lags in theoretical and empirical work necessary for advancing research and practice with refugees in resettlement. Indeed, the analysis brings into question the usefulness of dominant social support theories developed in the Global North, wholly disconnected from issues of forced migration, in understanding resettlement experiences.

The analysis detected additional gaps in conceptualizations of social support. While the definitions of social support identified in the analysis drew from well-established literature, few studies accounted for specific contextual considerations, as well as social, cultural, and linguistic factors that may be important in operationalizing social support for the purposes of research. It is important to note that understandings of social support developed in the academic literature and applied in an area of scholarship dominated by the U.S., as indicated in the current analysis, may inadvertently privilege perspectives and values (i.e. individualism and self-sufficiency) that may not align with viewpoints and values of people resettling from diverse contexts. Conceptualizing the construct of social support in context (Williams et al. 2004) requires meaningful engagement with those from affected groups—in research design, implementation, analysis, and co-authorship—to overcome inherent biases.

Nevertheless, the analysis produced a rich compendium of domains and dimensions of support important to consider in refugee resettlement scholarship moving forward. Forms of social support detected in the analysis reflect well-established domains (e.g. practical, emotional, and informational support, companionship), related concepts not commonly operationalized in social support research (e.g. attachment and affirmational support), and emergent domains specific to resettlement that deserve further exploration (e.g. adjustment support). While we recognize that domains such as emotional, affirmational, and companionship support are inter-related and often grouped together in dominant social support theories (Cobb 1976; Norbeck 1988), we separate them here because they highlight nuanced aspects of support for refugees important to highlight given the nascent state of the literature. In this analysis, emotional support includes expressions of empathy and caring, and having someone to talk to about problems. Affirmational support (included in seminal work but not typically studied) emerged as interactions that confer a sense of self, particularly important for new arrivals to resettlement contexts that may not offer ample opportunities for self-affirmation. Companionship, here, refers to feelings of support gleaned from what should be common interactions and regular participation in social activites, but may not be due to resettlement processes. Belonging, while a significant theme in the immigrant and refugee literature (Bhabha 2009; Strang and Ager 2010; Kılıç and Menjívar 2013) may deserve further consideration in operationalizing social support in future research.

The findings also highlight the importance of considering multi-level systems of support across the social ecology. It makes sense that the studies in the current analysis gravitated toward pivotal and proximate sources of support embedded in family and community systems. Surprisingly few studies, however, examined transnational sources of support, historically important for refugees (Baldassar 2007) and increasingly available through low-cost information and communication technologies (Navarrete and Huerta 2006). While family and community members are critical sources of support, the diversification and expansion of social networks is important for broader and longer-term integration goals (Ager and Strang 2008; Johnson-Agbakwu et al. 2014). The findings also highlighted the importance of considering faith and religious, school, and neighborhood systems in social support research in resettlement. Indeed, research consistently finds that spirituality, faith, and religion is particularly important for coping with hardship and chronic adversity (Snyder 2012; Walker et al. 2012; Hasan et al. 2018). Similarly, educational systems are important sources of support for children and their families, as well as adult learners, and represent settings critical to acculturation and adaptation through interactions with peers and teachers (Trickett and Birman 2005). The small number of studies in the current analysis found that neighbors who lived in close proximity were particularly important in times of crisis (Anderson et al. 2014) and may have significance for refugees who view relationships with neighbors as an important indicator of integration (Drolet and Moorthi 2018).

Implications for Conceptual and Empirical Research

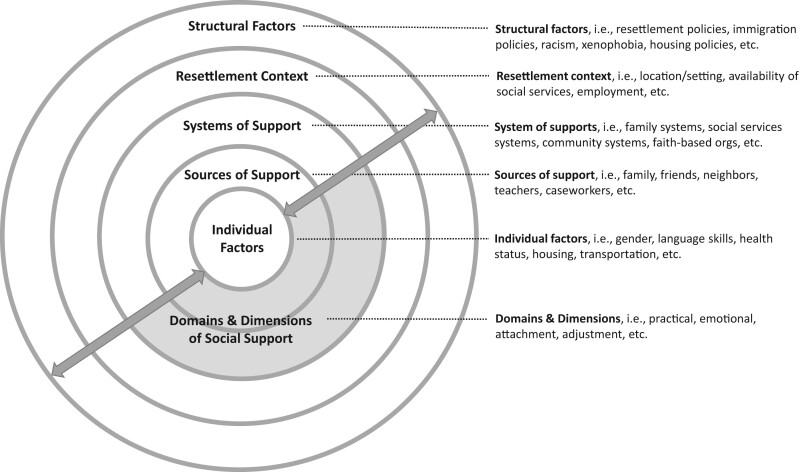

Grounded in this analysis and in concert with additional considerations discussed below, we propose a variation of the ecological model (Bronfenbrenner 1977) as a starting point to advance necessary conceptual and empirical work moving forward. Our proposed social support in resettlement ecological model, visualized in Figure 3, depicts multi-level systems of diverse forms of potential support available through interpersonal networks, and highlights the interplay between structural, contextual, interpersonal, and individual factors, which shape and influence access to and utilization of social support.

Figure 3.

Ecological model of social support in resettlement.

Individual factors influence needs for and access to social support among individuals, such as age, gender, language proficiency, housing, access to technology, transportation, time since resettlement, employment status, family composition, and health and mental health. As described earlier in this paper, sources of support refer to people from whom support is derived, examples of which may include family members and friends spanning local, national, and transnational contexts, peers, church congregants, social service providers, and neighbors embedded in systems of support. Systems of support refer to inter-related networks of potential support made up of diverse institutions, government agencies, and organizations. This level includes, for example, family and school systems, faith-based organizations, refugee-resettlement agencies, and community-based organizations (see Table 4). Cutting across sources and systems, and similarly shaped by individual, resettlement, and structural factors, are domains and dimensions of support, which refer to the types and varied expressions of support people value, need, and seek. Domains that emerged from this analysis, specific to refugees in resettlement contexts, included practical, emotional, attachment, informational, companionship, affirmational, and adjustment support, among others (see Table 3).

Moving toward the outer levels of the model, the resettlement context refers to resettlement-related factors that influence social support such as location (e.g. rural/urban/peri-urban/suburban), initial housing placement, availability of social services, and employment. Finally, structural factors capture resettlement policies (e.g. resettlement of women as single mothers), immigration policies of receiving countries, xenophobia, racism, patriarchy, global pandemics, housing policies, and other structural factors influencing all aspects of people’s experiences in resettlement, including social support. These findings are by no means exhaustive; subsequent studies that center social support in resettlement will serve to expand upon and refine our proposed model.

In addition, the current analysis underscores the need to prioritize social support in research concerned with the short- and long-term well-being of refugees in resettlement. Resettlement-specific conceptualizations of social support must reflect the scope and nature of losses and needs among refugees in resettlement, including ambiguous losses that are inherently relational and indeterminate in nature (Utržan and Northwood 2017). These perspectives challenge us to consider subtle and nuanced losses of resources embedded in relationships ruptured by forced migration (Bunn 2019; Bunn and Samuels in progress). Conceptualizations of social support must reflect, as well, the heteogeniety among diverse people and groups. Needs for social support are amplified by forced migration and resettlement, experiences of which results in uprooting, disconnecting, and disrupting systems of support essential to daily life with varying implications for individuals and groups. People resettle from diverse countries of origin and aslyum, and socio-cultural backgrounds, shaping what support they need, value, and expect from familial, social, and professional relationships. Therefore, the study of social support must account for past (pre-resettlement) and present meanings, expectations of, and needs for social support.

As the current analysis indicated (with some exceptions), the refugee resettlement literature does not sufficiently explain cumulative losses of and shifting needs for social support in resettlement, nuances of support needs across groups and social locations, or how people rebuild social support networks in the aftermath of forced migration. To build this body of knowledge, it is vital that research moving forward conceptualize social support as an outcome of interest in its own right, as well as a social determinant of health and other outcomes relevant to refugees undergoing resettlement, such as markers of integration (Ager and Strang 2008). The findings from this analysis alone point to a range of relevant outcomes including adaptation, well-being, and racial injustice as salient to refugee experiences in resettlement; however, these areas in relation to social support are emergent and need to be developed further. Attention to the directionality of support is important in the context of resettlement whereby people frequently provide practical support through remittances and other resources to family members and communities in countries of origin and asylum.

Additional advancements in this area of scholarship require integrating temporal perspectives and methodological approaches, given the phased nature of rebuilding life in a new country. Studies that employed temporal perspectives in this review offered important insights regarding heightened needs for social support at various times in the resettlement process. Longitudinal approaches are also critical to examining and establishing causal associations between social support and other key outcomes in resettlement.

Finally, while measurement was not the focus of the current study, it is worth noting that the ‘under-conceptualization’ of social support apparent in this analysis may be partly due to the use of measures that do not adequately reflect the experiences of people whose support systems were dismantled by war, forced migration, and resettlement. A review of existing social support scales used in refugees’ resettlement research (Boateng et al. in press), a companion to this study, suggests this is the case. An important step forward would be the development, and subsequent adaptations, of a context-specific scale to assess social support in resettlement for the purposes of research and practice.

Limitations

We followed a rigorous and systematic approach to our scoping review of the literature. However, our study faced limitations related to the availability of published literature and the information detailed in the articles; indeed, the process excluded many articles due to insufficient information on social support. The reality of the state of social support conceptualization in refugee resettlement research is likely considerably direr than presented in this analysis. Notably, we were unable to conduct a rich analysis of theories underpinning the research due to lack of information reported in the articles. In addition, the majority (56%) of the studies included took place in the U.S., which may skew our findings to this specific resettlement and research contexts. It is important to highlight the analysis did not include conceptualizations of social support described in other languages (i.e. Spanish, French, or Arabic) and beyond the peer-reviewed literature. Finally, the domains and dimensions analysis may not be exhaustive due to a lack of information on measurement provided in some articles. In spite of these limitations, our systematic approach to this review provides an in-depth and unique analysis of social support research with refugees in resettlement.

Conclusion

This review of the refugee resettlement literature highlights the importance of conceptual and contextual nuance of social support. The analysis identified directions for research with the aim of shaping innovations in research, and ultimately in practice. Advances in research must account for social support losses and needs due to forced migration and resettlement, and ground the construct in lived experiences of resettlement over time. Research efforts moving forward must robustly examine and theorize social support in its own right and in connection to a wide range of relevant outcomes, including health and well-being. Paying deserved attention to social support in resettlement will engender innovations in research and practice that track complexities associated with the social-relational needs of refugees and their well-being over the long-term.

Acknowledgements

We thank the students at Arizona State University who assisted with the project, especially Ciera Babbrah, Alyssa Lindsey, Amy Tjhia, and Willard Wilkerson. We would also like to express our appreciation for the insights and guidance provided by the JRS reviewers.

Contributor Information

Karin Wachter, School of Social Work, Arizona State University, 411 N Central Avenue, Suite 800, Phoenix, AZ 85004, USA.

Mary Bunn, Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1601 W. Taylor Street, SPHPI MC 912, Chicago, IL 60612, USA.

Roseanne C Schuster, Center for Global Health, School of Human Evolution & Social Change, Arizona State University, SHESC 262, 900 Cady Mall, Tempe, AZ 85281, USA.

Godfred O Boateng, College of Nursing and Health Innovation, The University of Texas at Arlington, MAC 155, 500 W Nedderman Drive, Arlington, TX 76019, USA.

Kaila Cameli, School of Social Work, Arizona State University, 411 N Central Avenue #800, Phoenix, AZ 85004, USA.

Crista E Johnson-Agbakwu, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Valleywise Health, 2525 E. Roosevelt Street, Phoenix, AZ 85008, USA; Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, Office of Refugee Health, Arizona State University, 201 N. Central Ave, Phoenix, AZ 85004, USA.

Funding Information

National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD/NIH), award 5U54 MD002316.

References

- AGBENYIGA D. L., BARRIE S., DJELAJ V., NAWYN S. J. (2012) ‘Expanding Our Community: Independent and Interdependent Factors Impacting Refugees’ Successful Community Resettlement’. Advances in Social Work 13(2): 306–324. [Google Scholar]

- AGER A., STRANG A. (2008) ‘Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework’. Journal of Refugee Studies 21(2): 166–191. [Google Scholar]

- ALEMI Q., JAMES S., SIDDIQ H., MONTGOMERY S. (2015) ‘Correlates and Predictors of Psychological Distress among Afghan Refugees in San Diego County’. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health 8(3): 274–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALEMI Q., SIDDIQ H., BAEK K., SANA H., STEMPEL C., AZIZ N., MONTGOMERY S. (2017) ‘Effect of Perceived Discrimination on Depressive Symptoms in 1st- and 2nd-Generation Afghan-Americans’. The Journal of Primary Prevention 38(6): 613–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALEMI Q., STEMPEL C. (2018) ‘Discrimination and Distress among Afghan Refugees in Northern California: The Moderating Role of Pre- and Post-Migration Factors’. Plos One 13(5): e0196822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSON L., HADZIBEGOVIC D. S., MOSELEY J. M., SELLEN D. W. (2014) ‘Household Food Insecurity Shows Associations with Food Intake, Social Support Utilization and Dietary Change among Refugee Adult Caregivers Resettled in the United States’. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 53(3): 312–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AO T., SHETTY S., SIVILLI T., BLANTON C., ELLIS H., GELTMAN P. L. et al. (2016) ‘Suicidal Ideation and Mental Health of Bhutanese Refugees in the United States’. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 18(4): 828–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARKSEY H., O'Malley L. (2005) ‘Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework’. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1): 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- AROIAN K. J. (1992) ‘Sources of Social Support and Conflict for Polish Immigrants’. Qualitative Health Research 2(2): 178–207. [Google Scholar]

- BALDASSAR L. (2007) ‘Transnational Families and the Provision of Moral and Emotional Support: The Relationship between Truth and Distance’. Identities 14(4): 385–409. [Google Scholar]

- BARANIK L. E., HURST C. S., EBY L. T. (2018) ‘The Stigma of Being a Refugee: A Mixed-Method Study of Refugees’ Experiences of Vocational Stress’. Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 116–130. [Google Scholar]

- BARNES D. M., AGUILAR R. (2007) ‘Community Social Support for Cuban Refugees in Texas’. Qualitative Health Research 17(2): 225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRERA M. Jr. (2000) ‘Social Support Research in Community Psychology’, In Rappaport J., Seidman E. (eds), Handbook of Community Psychology. Boston, MA: Springer, pp. 215–245. [Google Scholar]

- BARRERA M., TOOBERT D. J., ANGELL K. L., GLASGOW R. E., MACKINNON D. P. (2006) ‘Social Support and Social-Ecological Resources as Mediators of Lifestyle Intervention Effects for Type 2 Diabetes’. Journal of Health Psychology 11(3): 483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENSON G. O., SUN F., HODGE D. R., ANDROFF D. K. (2012) ‘Religious Coping and Acculturation Stress among Hindu Bhutanese: A Study of Newly-Resettled Refugees in the United States’. International Social Work 55(4): 538–553. [Google Scholar]

- BERKMAN L. F. (2000) ‘Social Support, Social Networks, Social Cohesion and Health’. Social Work in Health Care 31(2): 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERKMAN L. F., GLASS T., BRISSETTE I., SEEMAN T. E. (2000) ‘From Social Integration to Health: Durkheim in the New Millennium’. Social Science & Medicine 51(6): 843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHABHA J. (2009) ‘The “Mere Fortuity” of Birth? Children, Mothers, Borders, and the Meaning of Citizenship’. In Benhabib S., Resncik J. (eds), Migration and Mobilities: Citizenship, Borders, and Gender. New York City, NY: New York University Press, pp. 187–227. [Google Scholar]

- BOATENG G. O., WACHTER K., SCHUSTER R. C. (in progress). ‘Analysis of social support measurement among refugees in resettlement contexts.’

- BRONFENBRENNER U. (1977) ‘Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development’. American Psychologist 32(7): 513–531. [Google Scholar]

- BUNN M. (2019) ‘Restoring Social Bonds: Group-based Treatment the Social Resources of Syrian Refugees in Jordan.’ Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Chicago. 10.6082/uchicago.2021.

- BUNN M., MARSH J. (2019) ‘Science and Social Work Practice: Client-Provider Relationships as an Active Ingredient Promoting Client Change’. In Brekke J., Anastas J. (eds) Social Work Science: Towards a New Identity. Oxford University Press, pp. 149–175. [Google Scholar]

- BUNN M., SAMUELS G. (in progress) ‘Ambiguous Loss of Home: The Social-Relational and Place-Based Consequences of War and Forced Migration.’

- CASIMIRO S., HANCOCK P., NORTHCOTE J. (2007) ‘Isolation and Insecurity: Resettlement Issues among Muslim Refugee Women in Perth, Western Australia’. Australian Journal of Social Issues 42(1): 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- COBB S. (1976) ‘Social Support as a Moderator of Life Stress’. Psychosomatic Medicine 38(5): 300–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHEN S. E., SYME S. L. (1985) Social Support and Health. Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- COHEN S. E., WILLS T. A. (1985) ‘Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis’. Psychological Bulletin 98(2): 310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLIC-PEISKER V. (2009) ‘Visibility, Settlement Success and Life Satisfaction in Three Refugee Communities in Australia’. Ethnicities 9(2): 175–199. [Google Scholar]

- DEBNAM K., HOLT C. L., CLARK E. M., ROTH D. L., SOUTHWARD P. (2012) ‘Relationship between Religious Social Support and General Social Support with Health Behaviors in a National Sample of African Americans’. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 35(2): 179–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DROLET J., MOORTHI G. (2018) ‘The Settlement Experiences of Syrian Newcomers in Alberta: Social Connections and Interactions’. Canadian Ethnic Studies 50(2): 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- FAW M. H. (2018) ‘Supporting the Supporter: Social Support and Physiological Stress among Caregivers of Children with Severe Disabilities’. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 35(2): 202–223. [Google Scholar]

- FRANKS F., FAUX S. A. (1990) ‘Depression, Stress, Mastery, and Social Resources in Four Ethnocultural Women’s Groups’. Research in Nursing & Health 13(5): 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARIÉPY G., HONKANIEMI H., QUESNEL-VALLÉE A. (2016) ‘Social Support and Protection from Depression: Systematic Review of Current Findings in Western Countries’. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science 209(4): 284–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERBER M. M., CALLAHAN J. L., MOYER D. N., CONNALLY M. L., HOLTZ P. M., JANIS B. M. (2017) ‘Nepali Bhutanese Refugees Reap Support through Community Gardening’. International Perspectives in Psychology 6(1): 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- GHAZINOUR M., RICHTER J., EISEMANN M. (2004) ‘Quality of Life among Iranian Refugees Resettled in Sweden’. Journal of Immigrant Health 6(2): 71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOODKIND J. R., HESS J. M., ISAKSON B., LANOUE M., GITHINJI A., ROCHE N. et al. (2014) ‘Reducing Refugee Mental Health Disparities: A Community-Based Intervention to Address Postmigration Stressors with African Adults’. Psychological Services 11(3): 333–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOTTLIEB B. H. (1988) Marshaling Social Support: Formats Processes and Effects. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- GOTTLIEB B. H. (1978) ‘Development and Application of a Classification Scheme of Informal Helping Behavior’. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences du Comportement 10(2): 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- GOTTLIEB B. H., BERGEN A. E. (2010) ‘Social Support Concepts and Measures’. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 69(5): 511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN M., KING E., FISCHER F. (2019) ‘Acculturation, Social Support and Mental Health Outcomes among Syrian Refugees in Germany’. Journal of Refugee Studies fez095. [Google Scholar]

- GURUNG R. A. (2013) Health Psychology: A Cultural Approach. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Centage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- HAGAMAN A., SIVILLI T., AO T., BLANTON C., ELLIS H., LOPES CARDOZO B., SHETTY S. (2016) ‘An Investigation into Suicides among Bhutanese Refugees Resettled in the United States between 2008 and 2011’. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 18(4): 819–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANLEY J., MHAMIED A. L., CLEVELAND A., HAJJAR J., HASSAN O., IVES G. et al. (2018) ‘The Social Networks, Social Support and Social Capital of Syrian Refugees Privately Sponsored to Settle in Montreal: Indications for Employment and Housing during Their Early Experiences of Integration’. Canadian Ethnic Studies 50(2): 123–149. [Google Scholar]

- HASAN N., MITSCHKE D. B., RAVI K. E. (2018) ‘Exploring the Role of Faith in Resettlement among Muslim Syrian Refugees’. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 37(3): 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- HARTER S. (1985) Manual for the social support scale for children. Denver, CO: University of Denver. [Google Scholar]

- HOLT-LUNSTAD J., SMITH T. B., LAYTON J. B. (2010) ‘Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-Analytic Review’. PLoS Medicine 7(7): e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOUSE J. S. (1981) Work Stress and Social Support. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- HSIEH H. F., SHANNON S. E. (2005) ‘Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis’. Qualitative Health Research 15(9): 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUPCEY J. E. (1998a) ‘Clarifying the Social Support Theory-Research Linkage’. Journal of Advanced Nursing 27(6): 1231–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUPCEY J. E. (1998b) ‘Social Support: Assessing Conceptual Coherence’. Qualitative Health Research 8(3): 304–318. [Google Scholar]

- JACOBSON D. E. (1986) ‘Types and Timing of Social Support’. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 27(3): 250–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIBEEN T. (2016) ‘Perceived Social Support and Mental Health Problems among Pakistani University Students’. Community Mental Health Journal 52(8): 1004–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON P. J., STOLL K. (2008) ‘Remittance Patterns of Southern Sudanese Refugee Men: Enacting the Global Breadwinner Role’. Family Relations 57(4): 431–443. [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON-AGBAKWU C. E., HELM T., KILLAWI A., PADELA A. I. (2014) ‘Perceptions of Obstetrical Interventions and Female Genital Cutting: Insights of Men in a Somali Refugee Community’. Ethnicity & Health 19(4): 440–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAHN R. L. (1979) Aging from Birth to Death: interdisciplinary Perspectives. Colorado: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- KHAWAJA N. G., WHITE K. M., SCHWEITZER R., GREENSLADE J. (2008) ‘Difficulties and Coping Strategies of Sudanese Refugees: A Qualitative Approach’. Transcultural Psychiatry 45(3): 489–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KILIÇ Z., MENJÍVAR C. (2013) ‘Fluid Adaptation of Contested Citizenship: Second-Generation Migrant Turks in Germany and the United States’. Social Identities 19(2): 204–220. [Google Scholar]

- KINGSBURY D. M., BHATTA M. P., CASTELLANI B., KHANAL A., JEFFERIS E., HALLAM J. S. (2019) ‘Factors Associated with the Presence of Strong Social Supports in Bhutanese Refugee Women during Pregnancy’. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 21(4): 837–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOVACEV L., SHUTE R. (2004) ‘Acculturation and Social Support in Relation to Psychosocial Adjustment of Adolescent Refugees Resettled in Australia’. International Journal of Behavioral Development 28(3): 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- LAKEY B., OREHEK E. (2011) ‘Relational Regulation Theory: A New Approach to Explain the Link between Perceived Social Support and Mental Health’. Psychological Review 118(3): 482–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZARUS R. S., FOLKMAN S. (1984) ‘Stress, Appraisal, and Coping’. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Laura S., David E., Hayley F. (2010) ‘Meanings of home and mental well-being among Sudanese refugees in Canada’. Ethnicity & Health, 15(2): 199–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEMASTER J. W., BROADBRIDGE C. L., LUMLEY M. A., ARNETZ J. E., ARFKEN C., FETTERS M. D. et al. (2018) ‘Acculturation and Post-Migration Psychological Symptoms among Iraqi Refugees: A Path Analysis’. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 88(1): 38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIAMPUTTONG P., KOH L., WOLLERSHEIM D., WALKER R. (2016) ‘Peer Support Groups, Mobile Phones and Refugee Women in Melbourne’. Health Promotion International 31(3): 715–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIAMPUTTONG P., KURBAN H. (2018) ‘Health, Social Integration and Social Support: The Lived Experiences of Young Middle-Eastern Refugees Living in Melbourne, Australia’. Children and Youth Services Review 85: 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- LUMLEY M., KATSIKITIS M., STATHAM D. (2018) ‘Depression, Anxiety, and Acculturative Stress among Resettled Bhutanese Refugees in Australia’. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 49(8): 1269–1282. [Google Scholar]

- MILLER K. E., RASMUSSEN A. (2010) ‘War Exposure, Daily Stressors, and Mental Health in Conflict and Post-Conflict Settings: Bridging the Divide between Trauma-Focused and Psychosocial Frameworks’. Social Science & Medicine 70(1): 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITSCHKE D. B., PRAETORIUS R. T., KELLY D. R., SMALL E., KIM Y. K. (2017) ‘Listening to Refugees: How Traditional Mental Health Interventions May Miss the Mark’. International Social Work 60(3): 588–600. [Google Scholar]

- NAVARRETE C., HUERTA E. (2006) ‘Building Virtual Bridges to Home: The Use of the Internet by Transnational Communities of Immigrants’. International Journal of Communications, Law and Policy (special issue). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=949626.

- NORBECK J. S. (1988) ‘Social Support’. In Fitzpatrick J. J., Taunton R. L., Benoliel J. Q. (eds) Annual Review of Nursing Research. New York: Springer, pp. 613–620. [Google Scholar]

- OPPEDAL B., IDSOE T. (2015) ‘The Role of Social Support in the Acculturation and Mental Health of Unaccompanied Minor Asylum Seekers’. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 56(2): 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIERCE G. R., LAKEY B., SARASON I. G., SARASON B. R., JOSEPH H. J. (1997) ‘Personality and Social Support Processes’. In Pierce, G. R., Lakey, B., Sarason, I. G. and Sarason, B. R. (eds) Sourcebook of social support and personality. New York: Plenum, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- PIERCE G. R., SARASON I. G., SARASON B. R. (1991) ‘General and Relationship—Based Perception of Social Support: Are Two Constructs Better Than One?’. J Pers Soc Psychol 61: 1028–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORTES A. (1998) ‘Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology’. Annual Review of Sociology 24(1): 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- RAHAPSARI S., HILL E. S. (2019) ‘The Body Against the Tides: A Pilot Study of Movement-Based Exploration for Examining Burmese Refugees’ Resilience’. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 15(1): 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- REES S., PEASE B. (2007) ‘Domestic Violence in Refugee Families in Australia’. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 5(2): 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- SALO C. D., BIRMAN D. (2015) ‘Acculturation and Psychological Adjustment of Vietnamese Refugees: An Ecological Acculturation Framework’. American Journal of Community Psychology 56(3–4): 395–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARASON I. G., SARASON B. R. (1990) ‘Test Anxiety’. In Leitenberg H. (ed.) Handbook of Social and Evaluation Anxiety. Boston, MA: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- SAVIC M., CHUR-HANSEN A., MAHMOOD M. A., MOORE V. (2013) ‘Separation from Family and Its Impact on the Mental Health of Sudanese Refugees in Australia: A Qualitative Study’. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 37(4): 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHRESTHA-RANJIT J., PATTERSON E., MANIAS E., PAYNE D., KOZIOL-MCLAIN J. (2017) ‘Effectiveness of Primary Health Care Services in Addressing Mental Health Needs of Minority Refugee Population in New Zealand’. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 38(4): 290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SILOVE D., VENTEVOGEL P., REES S. (2017) ‘The Contemporary Refugee Crisis: An Overview of Mental Health Challenges’. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association 16(2): 130–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMICH L., BEISER M., MAWANI F. N. (2003) ‘Social Support and the Significance of Shared Experience in Refugee Migration and Resettlement’. Western Journal of Nursing Research 25(7): 872–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNYDER S. (2012) Asylum-Seeking, Migration and Church . Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- STEWART M., ANDERSON J., BEISER M., MWAKARIMBA E., NEUFELD A., SIMICH L., SPITZER D. (2008) ‘Multicultural Meanings of Social Support among Immigrants and Refugees’. International Migration 46(3): 123–159. [Google Scholar]

- STEWART M. J., LAGILLE L. (2000) ‘A Framework for Social Support Assessment and Intervention in the Context of Chronic Conditions and Caregiving’. In Stewart M. J. (ed.) Chronic Conditions and Caregiving in Canada: Social Support Strategies. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- STRANG A., AGER A. (2010) ‘Refugee Integration: Emerging Trends and Remaining Agendas’. Journal of Refugee Studies 23(4): 589–607. [Google Scholar]

- TAKEDA J. (2000) ‘Psychological and Economic Adaptation of Iraqi Adult Male Refugees: Implications for Social Work Practice’. Journal of Social Service Research 26(3): 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- TEZCI E., SEZER F., GURGAN U., AKTAN S. (2015) ‘A Study on Social Support and Motivation’. The Anthropologist 22(2): 284–292. [Google Scholar]

- THOITS P. A. (1982) ‘Conceptual, Methodological, and Theoretical Problems in Studying Social Support as a Buffer against Life Stress’. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 23(2): 145–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOITS P. A. (1985) ‘Social Support and Psychological Well-Being: Theoretical Possibilities’. In Sarason I. G. (ed.), Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications. Dordrecht, NL: Springer, pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- TRICKETT E. J., BIRMAN D. (2005) ‘Acculturation, School Context, and School Outcomes: Adaptation of Refugee Adolescents from the Former Soviet Union’. Psychology in the Schools 42(1): 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- TURENNE C., GAUTIER L., DEGROOTE S., GUILLARD E., CHABROL F., RIDDE V. (2019) ‘Conceptual Analysis of Health Systems Resilience: A Scoping Review’. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 232: 168–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UCHINO B. N., BOWEN K., CARLISLE M., BIRMINGHAM W. (2012) ‘Psychological Pathways Linking Social Support to Health Outcomes: A Visit with the “Ghosts” of Research past, Present, and Future’. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 74(7): 949–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UMBERSON D., KARAS MONTEZ J. (2010) ‘Social Relationships and Health: A Flashpoint for Health Policy’. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51(1_suppl): S54–S66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES [UNHCR]. (2019) ‘Worldwide Displacement Tops 70 Million, UN Refugee Chief Urges Greater Solidarity in Response’. [online], https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/press/2019/6/5d03b22b4/worldwide-displacement-tops-70-million-un-refugee-chief-urges-greater-solidarity.html

- UTRŽAN D. S., NORTHWOOD A. K. (2017) ‘Broken Promises and Lost Dreams: Navigating Asylum in the United States’. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 43(1): 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WACHTER K., GULBAS L. E. (2018) ‘Social Support under Siege: An Analysis of Forced Migration among Women from the Democratic Republic of Congo’. Social Science & Medicine 208: 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WACHTER K., GULBAS L. E., SNYDER S. (2021). ‘Connecting in resettlement: An examination of social support among Congolese women in the United States.’ Qualitative Social Work 0(0), p. 1–18. DOI: 10.1177/14733250211008495.

- WALKER R., KOH L., WOLLERSHEIM D., LIAMPUTTONG P. (2015) ‘Social Connectedness and Mobile Phone Use among Refugee Women in Australia’. Health & Social Care in the Community 23(3): 325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER P., MAZURANA D., WARREN A., SCARLETT G., LOUIS H. (2012) ‘The Role of Spirituality in Humanitarian Crisis Survival and Recovery’. In Barnett M., Stein J. (eds) Sacred Aid: Faith and Humanitarianism. Oxford University Press, pp. 115–139. [Google Scholar]

- WEINE S. M., RAINA D., ZHUBI M., DELESI M., HUSENI D., FEETHAM S. et al. (2003) ‘The TAFES Multi-Family Group Intervention for Kosovar Refugees: A Feasibility Study’. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191(2): 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEINE S. M., WARE N., HAKIZIMANA L., TUGENBERG T., CURRIE M., DAHNWEIH G. et al. (2014) ‘Fostering Resilience: Protective Agents, Resources, and Mechanisms for Adolescent Refugees’ Psychosocial Well-Being’. Adolescent Psychiatry (Hilversum, Netherlands) 4(4): 164–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEISS R. (1973) Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- WEISSBECKER I., HANNA F., EL SHAZLY M., GAO J., VENTEVOGEL P. (2019) ‘Integrative Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Interventions for Refugees in Humanitarian Crisis settings’ In Wenzel T., Drožđek B. (eds) An Uncertain Safety. Cham: Springer, pp. 117–153. [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS P., BARCLAY L., SCHMIED V. (2004) ‘Defining Social Support in Context: A Necessary Step in Improving Research, Intervention, and Practice’. Qualitative Health Research 14(7): 942–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]