Abstract

Background:

On May 24, 2017, the Quebec College of Family Physicians held an innovation symposium inspired by the television show Dragons’ Den, at which innovators pitched their innovations to Dragon-Facilitators (i.e., decision-makers) and academic family medicine clinical leads. We evaluated the effects of the symposium on the spread of primary health care innovations.

Methods:

We conducted a mixed-methods evaluation of the symposium. We collected data related to Rogers’ innovation-decision process using 3 quality-improvement e-surveys (distributed between May 2017 and February 2018). The first survey evaluated spread outputs (innovation discovery, intention to spread, improvements) and was sent to all participants immediately after the symposium. The second evaluated short-term spread outcomes (follow-ups, successes, barriers) and was sent to innovators 3 months after the symposium. The third evaluated medium-term spread outcomes (spread, perceived impact) and was sent to innovators and clinical leads 9 months after the symposium. We analyzed the data using descriptive statistics, content analysis and joint display.

Results:

Fifty-one innovators, 66 clinical leads (representing 42 clinics) and 37 Dragon-Facilitators attended the symposium. The response rates for the surveys were 61% (82/134) for the immediate post-symposium survey of all participants; 68% (21/31) for the 3-month survey of innovators; and 49% (48/97) for the 9-month survey of clinical leads and innovators. Immediately after the symposium, clinical leads and Dragon-Facilitators reported a high likelihood of adopting an innovation (mean ± standard deviation 8.02 ± 1.63 on a 10-point Likert scale) and 87% (53/61) agreed that they had discovered innovations at the symposium. Nearly all innovators (95%, 20/21) intended to follow up with potential adopters. After 3 months, 62% (13/21) of innovators had followed up in some way. After 9 months, 72% of clinical leads (18/25) had implemented at least 1 innovation, and 52% of innovators (12/23) had spread or were in the process of spreading innovations.

Interpretation:

The innovation symposium supported participants in achieving the early stages of spreading primary health care innovations. Replicating such symposia may help spread other health care innovations.

Although countless innovations show promise for improving health care, few are successfully spread beyond the context in which they are piloted.1–4 More than a decade after Canada was infamously described as the “land of perpetual pilot projects,”3 a lack of innovation spread remains one of the greatest challenges to improving health care.5–8 Spread is the diffusion of local improvements and innovations through knowledge translation, to increase their reach and adoption in health systems.4

A substantial amount of research has identified key factors needed to spread innovations successfully, including observability to potential adopters; compatibility with the values, contexts and needs of potential adopters; the innovation’s relative advantage; sufficient time and resources to support spread; championing of spread among innovators and early adopters; and capacity building and supportive structures. 1,2,9–13 These factors are fundamental, but they offer few tangible strategies for organizations seeking to spread an innovation (e.g., medical associations, professional colleges, governments or practice-based research networks).

In 2016 in Quebec, amid major health system reforms,14 family physicians were being encouraged to implement the patient medical home — a vision for Canada’s primary health care practices that would provide patients with most of their care in a way that is readily accessible in the community, is centred on patients’ needs, is anchored by a personal family physician who works with an interprofessional team, and is integrated with other health services.15

The Quebec College of Family Physicians organized an innovation symposium inspired by the television show Dragons’ Den to help spread promising primary health care innovations that supported the concept of the patient medical home.15 The objective of the current study was to evaluate the effects of this symposium on the spread of primary health care innovations. We hypothesized that the symposium would help participants progress through the innovation-decision process,10 which is essential to the spread of innovations.

Methods

Design and setting

The Quebec College of Family Physicians hosted an innovation symposium in May 2017 in Montréal. We conducted a mixed-methods study using quality improvement surveys to evaluate the effects of the symposium on the spread of innovations. We sent the surveys to symposium participants between May 2017 and February 2018. Our methods were informed by Rogers’ innovation-decision process,10 which describes the adoption of innovations at the individual level and is central to the diffusion of innovation theory (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/1/E247/suppl/DC1). This study was reported according to the SQUIRE 2.0 reporting guideline16 and the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES).17

Participants

To recruit innovators, calls went out in October and November 2016 via newsletters and listservs in departments of family medicine, practice-based research networks and medical associations, mainly in Quebec but also through a few national organizations. Calls went out in French, but the Quebec College of Family Physicians offered assistance filling out the call form for English speakers, if needed. Innovators included anyone involved in piloting a primary health care innovation who could present the innovation at the symposium (e.g., family physicians, researchers, decision-makers, allied health professionals, patients, community organizations or companies).

Clinical leads (family physicians designated as the medical directors of university family medicine groups) were contacted by email. Their email addresses were available from a list of university family medicine group directors from the Quebec College of Family Physicians. These clinical leads were invited to attend the symposium and asked to bring a team member (e.g., a clinic administrator). University family medicine groups are academically affiliated, interprofessional primary health care teams with a teaching mission; they are intended to expose family medicine residents and other trainees to best practices.18

Stakeholders with the resources to support innovation spread were invited to the symposium as Dragon-Facilitators, including representatives from the Ministry of Health and Social Services, practice-based research networks, the College of Family Physicians of Canada, the Canadian Medical Association, Réseau-1 Québec (Primary and Integrated Healthcare Innovation Network), the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Support unit, departments of family medicine, the Fédération des médecins omnipraticiens du Québec and the Institut national d’excellence en santé et services sociaux.

Intervention

The symposium was inspired by Dragons’ Den, a reality television show in which entrepreneurs pitch their business ideas to potential investors in the hope of securing funding, mentoring and support.19 The goals of the symposium were as follows: to spread innovations relevant to the concept of the patient medical home, to foster networking and to celebrate the contributions of primary health care teams to their communities. Given the breadth of innovations, which varied in terms of stakeholders needed to support spread, we invited a wide range of Dragon-Facilitators. Innovations were submitted to the symposium in French or English; they were reviewed and selected (M.J.P., M.D.P.) based on the criteria detailed in Table 1.

Table 1:

Selection criteria for innovations presented at the innovation symposium

| Criterion | Reason |

|---|---|

| Pilot-tested in a similar context and had undergone some form of evaluation | The symposium was intended to showcase real-world, tested innovations as realistic and achievable examples of what could be implemented by participants. |

| Related to service delivery in university family medicine groups | The symposium targeted these team-based academic primary health care teams because quality improvement is part of their mission and they train residents who will then practise in other teams, with the potential for further innovation spread. |

| Aligned with the vision of the patient medical home | The features of the patient medical home have been associated with better quality, access, efficiency, equity of health systems and better health outcomes for patients, and they were a major priority in Quebec and in Canada.15 |

The symposium was held on May 24, 2017. The innovators set up booths at the symposium. At the start of the symposium, 2 plenaries (in French) provided an overview and examples of the patient medical home concept. Next, the 12 innovations deemed to be best aligned with the criteria in Table 1 (i.e., most relevant and mature) were pitched to clinical leads and Dragon-Facilitators in 6-minute, rapid-fire presentations (2 sessions of 6 innovations). Each session was followed by “blitz networking,” in which clinical leads and Dragon-Facilitators visited the booths of the presented innovations to obtain more information and express interest in adopting or supporting an innovation.

An “innovation café” allowed participants to connect with innovators from the 12 rapid-fire presentations, and to see 19 additional innovations. Each innovation booth had a visitor card on which interested parties could leave a sticker with their contact information — a simple way for innovators to capture overall interest in their innovation and generate contact lists for follow-up after the symposium. Clinical leads, innovators and Dragon-Facilitators then participated in separate workshops on implementing the patient medical home and spreading innovations. The symposium concluded with closing remarks and a networking cocktail party.

Outcomes

Informed by Rogers’ innovation-decision process,10 we conceptualized our study outcomes as a process, along which spread outputs and short- and medium-term outcomes would occur after the symposium. We evaluated the effects of the symposium as a communication channel and its outcomes related to knowledge of innovations; persuasion and decision to adopt innovations; and implementation of innovations (Appendix 1).

The time required to achieve spread outcomes is difficult to anticipate, and it varies based on the context, the adopter and the characteristics of the innovation.10 However, we hypothesized that certain spread outputs (e.g., discovery of new innovations, intention to follow up) could be measured immediately after the symposium, because they could be produced during the symposium. Based on previous experience in primary health care, we estimated that 3 months after the symposium was the minimum time interval for short-term spread outcomes to occur (e.g., follow-ups, spread successes and barriers), and 9 months might allow participants to achieve certain medium-term spread outcomes (e.g., decision to adopt an innovation, new ideas).

Data sources

We collected data using e-surveys, sent out to symposium participants in 3 phases: immediately after the symposium, and 3 and 9 months later. The surveys were in French only, but participants could respond in English. We used the platform Simple Survey (www.simplesurvey.com) for the first and third surveys; the second survey was a set of open-ended questions sent by email. Survey participation was voluntary and anonymous. For each survey, participants had 4 weeks to respond, and 2 reminders were sent.

Surveys were developed by M.J.C. (continuing professional development and practice support manager, Quebec College of Family Physicians) and M.D.P. (president, Quebec College of Family Physicians, at the time), inspired by the innovation-decision process, their experience in primary health care and the need for information to improve future spread efforts. M.J.C. and M.D.P. pretested the surveys for usability, and M.J.C. managed the surveys, emails and reminders. Translations of the surveys are available in Appendix 1.

Survey immediately after the symposium

The day after the symposium, we sent an email containing a link to a 17-question survey on spread outputs to the clinical leads and Dragon-Facilitators. We sent a similar 19-question survey to the innovators. The surveys included multiple-choice, Likert-scale and open-ended questions asking people about their experience at the symposium, their discovery of innovations, their intent to follow up on or adopt innovations, and their suggestions for improving the symposium.

Survey at 3 months

Three months after the symposium, we contacted the innovators by email and asked 3 open-ended questions about short-term spread outcomes (i.e., follow-up with potential adopters, spread successes and barriers).

Survey at 9 months

Nine months after the symposium, we sent a link to a 4-question survey on medium-term spread outcomes to clinical leads and innovators. We did not survey the Dragon-Facilitators. The survey included multiple-choice, Likert-scale and open-ended questions and asked about innovation spread, the perceived impact of adopted innovations, other ideas for innovations sparked by the symposium and suggestions for further support.

Data analysis

We exported all survey responses to Excel and included them in our analysis. For responses to closed-ended questions, we calculated descriptive statistics (i.e., means, standard deviations, percentages).

We conducted qualitative content analysis20 to summarize participants’ responses to the open-ended questions. The qualitative data were coded inductively and summarized by a doctoral candidate in health services research who was trained in mixed-methods approaches (M.A.S.). To enhance trustworthiness, M.B. (a qualitative researcher with expertise in primary health care innovations), M.J.C. and M.D.P. (both with expert-knowledge of the symposium, patient medical home and family medicine related context) reviewed the content summaries, and all authors discussed them.

We used joint displays to present related quantitative and qualitative results side by side and to facilitate mixed-methods integration.21

Ethics approval

An ethics exemption was granted by St. Mary’s Hospital Center Research Ethics Committee.

Results

In total, 154 participants attended the symposium: 51 innovators (some innovations were represented by more than 1 innovator), 66 clinical leads and 37 Dragon-Facilitators. Of the 47 directors of university family medicine groups invited, 42 were represented at the symposium (89%). Based on our selection criteria (Table 1), 31 innovations were presented at the symposium (summaries in Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/1/E247/suppl/DC1).

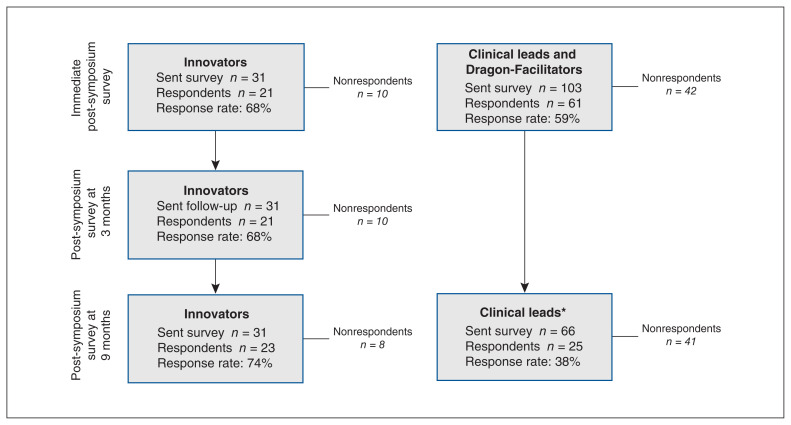

Figure 1 presents response rates for each survey. For innovators, response rates were 68% immediately after the symposium, 68% at 3 months and 74% at 9 months. Immediately after the symposium, 59% of the clinical leads and Dragon-Facilitators responded (surveyed together). At 9 months, the response rate for clinical leads was 38%.

Figure 1:

Data collection flow chart. *Dragon-Facilitators were not surveyed at 9 months.

Survey immediately after the symposium

Spread outputs are presented in Table 2. Immediately after the symposium, clinical leads and Dragon-Facilitators reported a high likelihood of adopting an innovation in the next year (mean score of 8.02 on a 10-point Likert scale) and most (87%, 53/61) agreed that the symposium had allowed them to discover innovations. Nearly all innovators (95%, 20/21) intended to follow up with potential adopters. More than 90% of participants said that they would recommend the symposium to a colleague and that they would like to be invited to a second edition.

Table 2:

Immediate post-symposium survey: spread outputs

| Quantitative survey items (closed-ended questions) | Qualitative survey items (open-ended questions) | |

|---|---|---|

| Item | n (%)* | Summary of responses and comments |

| Innovators (n = 21 respondents) | ||

| Intend to follow up with interested clinical leads and Dragon-Facilitators | No intention of following up (n = 1): not applicable | |

| Yes | 20 (95) | |

| No | 1 (5) | |

| Expected method of follow-up with interested parties (could select multiple answers) | Follow-up method to be determined with teams based on mutual interests | |

| Individually (email or phone) | 17 (85) | |

| Follow-up meeting | 6 (30) | |

| Create a committee | 4 (20) | |

| Would recommend the symposium to a colleague | Would not recommend symposium (n = 1): did not meet current needs | |

| Yes | 19 (90) | |

| No | 1 (5) | |

| Missing | 1 (5) | |

| Would like to be invited to a second edition | Symposium highlights:

|

|

| Yes | 20 (95) | |

| No | 1 (5) | |

| Clinical leads and Dragon-Facilitators (n = 61 respondents) | ||

| Symposium format met the objective of discovering new innovations | Innovation discovered:

|

|

| Agree | 53 (86) | |

| Disagree | 4 (7) | |

| Missing | 4 (7) | |

| Likelihood of adopting or supporting an innovation in the next year, mean ± SD† | 8.02 ± 1.63 | – |

| Would recommend the symposium to a colleague | Would not recommend symposium (n = 1): good intentions, but did not meet needs | |

| Yes | 59 (96) | |

| No | 1 (2) | |

| Missing | 1 (2) | |

| Would like to be invited to a second edition | Symposium highlights:

|

|

| Yes | 59 (96) | |

| No | 1 (2) | |

| Missing | 1 (2) | |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

Unless indicated otherwise.

0 = not at all likely, 10 = extremely likely.

Participants suggested some improvements to the symposium format, such as workshops that focused on spread implementation and change management. Innovators advocated for more structured interactions with Dragon-Facilitators to obtain better feedback and potential buy-in as a way of supporting spread. Participants also suggested that Dragon-Facilitators provide closing remarks at the end of the symposium to reflect on promising innovations, trends and next steps. Some participants recommended that Dragon-Facilitators include regional-level decision-makers and more patient partners. Some proposed the symposium could be an opportunity to brainstorm innovative solutions to unaddressed primary health care issues via facilitated discussions between stakeholders. Some expressed their interest in receiving further mentoring from Dragon-Facilitators after the symposium and participating in a follow-up session that would feature the spread progress of popular innovations, lessons learned and workshops to support spread.

Survey at 3 months

Table 3 presents results related to short-term spread outcomes. Three months after the symposium, more than half of the innovator responders (62%, 13/21) had followed up with potential adopters (e.g., made email contact, set up committees, formed partnerships). Some innovators reported that they had engaged stakeholders, established partnerships, applied for funding or initiated innovation implementation. Barriers described by innovators included lack of time, lack of dedicated resources, change fatigue and competing priorities.

Table 3:

Three-month post-symposium survey: short-term spread outcomes

| Question | Response |

|---|---|

| Innovators (n = 21 respondents) | |

| How have your post-symposium follow-ups been going? | Followed up (62%, 13/21)

|

| What have your successes been to date? | Resources and partners

|

| What barriers have you faced? | Barriers related to the innovation

|

Survey at 9 months

Results related to medium-term spread outcomes are presented in Table 4. Reported results are among survey respondents (38% of clinical leads and 74% of innovators).

Table 4:

Nine-month post-symposium survey: medium-term spread outcomes*

| Quantitative survey items (closed-ended questions) | Qualitative survey items (open-ended questions) | |

|---|---|---|

| Item | n (%)† | Summary of responses and comments |

| Innovators (n = 23 respondents) | ||

| Innovation has been spread to new context(s) | Innovation spread:

|

|

| Yes | 9 (39) | |

| Not yet, but in progress | 3 (13) | |

| No | 7 (30) | |

| Don’t know | 2 (9) | |

| Missing or not applicable | 2 (9) | |

| Symposium sparked other new ideas, opportunities or projects | New ideas sparked by symposium:

|

|

| Yes | 11 (48) | |

| No | 12 (52) | |

| Clinical leads (n = 25 respondents) | ||

| Adopted 1 or more symposium innovations | Reason for not having adopted an innovation:

|

|

| Yes | 18 (72) | |

| If yes, degree to which it is perceived to have improved the primary health care team’s experience, mean ± SD‡ | 6.89 ± 2.00 | |

| If yes, degree to which it is perceived to have improved the patient experience, mean ± SD‡ | 6.32 ± 2.8 | |

| No | 7 (28) | |

| Symposium sparked other new ideas, opportunities or projects | New ideas sparked by symposium:

|

|

| Yes | 15 (60) | |

| No | 10 (40) | |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

Dragon-Facilitators were not surveyed at 9 months.

Unless indicated otherwise.

0 = not at all likely, 10 = extremely likely.

Nine months after the symposium, 18 clinical lead survey respondents (72%) had implemented at least 1 innovation, and 12 innovators had spread (39%, 9/23) or were in the process of spreading (13%, 3/23) their innovation to at least 1 new context. As well, 48% of innovators and 60% of clinical leads reported that the symposium had sparked other new ideas.

To support further spread of innovation, innovators and clinical leads encouraged the Quebec College of Family Physicians to find more channels to feature promising innovations: video clips, newsletters, a searchable Web platform or blog posts. Several innovators mentioned the need for additional human resources or coaching to support spread after the symposium. Clinical leads expressed interest in another symposium with innovations in specific areas (e.g., interprofessional collaboration, resident training, advanced access).

Interpretation

We hypothesized that the symposium would help participants progress through the stages of Rogers’ innovation-decision process,10 essential to the spread of innovation. Our results supported this hypothesis: the innovation symposium seems to have helped achieve spread outputs and short- and medium-term outcomes involved in the process of spreading innovations. Our findings suggest that the symposium led to discovery of innovations, intentions to adopt innovations, follow-up between potential adopters and innovators, and the spread of innovations to new contexts.

Although very little research has evaluated the effectiveness of strategies to support the spread of primary health care innovations in high-income settings,4 it has been estimated that less than 40% of innovations and quality-improvement initiatives spread to other contexts.22,23 In comparison, the innovation symposium seems to have supported a higher rate of innovation spread by 9 months after the symposium.

Our findings suggest the symposium played an important role in engaging participants in communication channels and achieving spread outputs and outcomes related to the first stages of the innovation-decision process.10 These stages are essential to spreading innovation, according to Rogers’ seminal diffusion of innovations theory10 and Berwick’s recommendations from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.1 The symposium became a venue for potential adopters to discover innovations they did not know about1 and to engage in exchange with innovators. Screening and selecting promising, relevant and feasible innovations helped to target those compatible with the values, needs and contexts of potential adopters (e.g., those aligned with the patient medical home concept).10 Showcasing innovations in an innovation café, rapid-fire presentations and blitz networking created new communication channels.10

By convening innovators, potential adopters (clinical leads) and supporters (Dragon-Facilitators) in a single venue, the symposium implemented several of Berwick’s recommendations for successfully spreading innovations:1 it made innovators and early adopters observable and approachable; it ensured that potential adopters heard about innovations directly from credible peers (e.g., physicians speaking to other physicians about an innovation); and it helped promote a culture of innovation.

Participants identified important remaining barriers to spread, including insufficient time, lack of dedicated resources, change fatigue and competing priorities. Avenues suggested for further supporting spread included involving regional-level decision-makers, having Dragon-Facilitators play a more substantial role during and after the symposium (e.g., coaching teams on finding resources and managing spread), and providing workshops on how to implement innovation spread. Participants also suggested that the symposium could be used to brainstorm innovations that could address current issues in primary health care. These suggestions should be addressed in future iterations of the symposium and when adapting the symposium to other contexts.

Limitations

The call for innovations and the 3 surveys were sent out in French only. Although response rates were fairly high among innovators, they were lower for clinical leads and Dragon-Facilitators; this may have introduced a nonresponse bias. However, survey response rates among clinical leads were comparable to average rates for health care providers.24 Clinical leads were representatives from university family medicine groups, which are academically affiliated primary health care teams, and this may limit the generalizability of our findings. As well, immediately after the symposium, we surveyed clinical leads and Dragon-Facilitators together, although their experiences may have differed.

Although we conducted a follow-up survey 9 months after the symposium, this period may have been insufficient for observing the sustained spread of innovations. We did not survey Dragon-Facilitators at 9 months, and this limited our insights into their role. As with all longitudinal evaluations, there is a chance that respondents’ answers may have been affected by recall bias, although we attempted to mitigate this in part by surveying participants immediately after the symposium, and at 3 and 9 months. Qualitative results were based on short responses to open-ended questions, which may have limited their richness. Nonetheless, triangulating quantitative results with qualitative responses and integrating them in joint displays helped us to validate our findings.

Future evaluations of similar activities should collect more data on respondents’ characteristics, implement strategies to increase response rates, collect more in-depth data on barriers, identify strategies to target stakeholders better and add follow-ups at 12 and 18 months to evaluate sustained effects on spread. Conducting qualitative case studies would provide valuable insights into how the spread of innovation could be better supported.

Conclusion

Spreading innovation is a potential lever for large-scale health care improvement. This innovation symposium helped achieve the first stages of the individual-level spread of primary health care innovations. In light of these promising results, the Quebec College of Family Physicians has decided to hold similar symposia every 2 years (one was held in 2019, and another has been planned for 2022, delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic). Replicating such symposia in other settings may help further spread health care innovations.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: Maxine Dumas Pilon and Marie-Josée Campbell were part of the symposium organizing committee. However, the results presented in this article are based on data independently analyzed by Mélanie Ann Smithman, who was not involved in the organization of the symposium and is not affiliated with the Quebec College of Family Physicians. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Mélanie Ann Smithman drafted the manuscript. Mylaine Breton, Maxine Dumas-Pilon and Marie-Josée Campbell provided critical feedback and reviewed the final manuscript. Maxine Dumas-Pilon and Marie-Josée Campbell designed the quality improvement project. Maxine Dumas-Pilon and Marie-Josée Campbell designed data collection. Mélanie Ann Smithman analyzed the data, overseen by Mylaine Breton. Mylaine Breton, Maxine Dumas-Pilon and Marie-Josée Campbell reviewed summaries and joint displays. All of the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The symposium and data collection were funded by the Quebec College of Family Physicians.

Data sharing: All data available to other researchers are presented in this paper.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/1/E247/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. 2003;289:1969–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Côté-Boileau É, Denis J-L, Callery B, et al. The unpredictable journeys of spreading, sustaining and scaling healthcare innovations: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17:84. doi: 10.1186/s12961-019-0482-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bégin M, Eggertson L, Macdonald N. A country of perpetual pilot projects. CMAJ. 2009;180:1185, E88–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben Charif A, Zomahoun HTV, LeBlanc A, et al. Effective strategies for scaling up evidence-based practices in primary care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2017;12:139. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0672-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zelmer J. Beyond pilots: scaling and spreading innovation in healthcare. Healthc Policy. 2015;11:8–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hutchison B, Abelson J, Lavis J. Primary care in Canada: so much innovation, so little change. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:116–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naylor D, Girard F, Mintz JM, et al. Unleashing innovation: excellent healthcare for Canada. Report of the advisory panel on healthcare innovation. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collier R. Author urges scale-up of health care innovation. CMAJ. 2017;189:E253–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1095385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82:581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perla RJ, Bradbury E, Gunther-Murphy C. Large-scale improvement initiatives in healthcare: a scan of the literature. J Healthc Qual. 2013;35:30–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchanan DA, Fitzgerald L, Ketley D, editors. The sustainability and spread of organizational change: modernizing healthcare. London and New York: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw J, Tepper J, Martin D. From pilot project to system solution: innovation, spread and scale for health system leaders. BMJ Leader. 2018;2:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee GE, Quesnel-Vallée A. Improving access to family medicine in Quebec through quotas and numerical targets. Health Reform Observer. 2019;7 doi: 10.13162/hro-ors.v7i4.3886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.A vision for Canada family practice—the patient’s medical home. Mississauga (ON): College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, et al. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24:466–73. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cadre de gestion des groupes de médecine de famille universitaires (GMF-U) [in French] Québec: Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dragons’ Den. Internet Movie Database. 2021. [accessed 2022 Jan. 18]. Available: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0443370/

- 20.Given LM. The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guetterman TC, Fetters MD, Creswell JW. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:554–61. doi: 10.1370/afm.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Counte MA, Meurer S. Issues in the assessment of continuous quality improvement implementation in health care organizations. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13:197–207. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/13.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quality improvement primers: spread primer. Toronto: Health Quality Ontario; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho YI, Johnson TP, VanGeest JB. Enhancing surveys of health care professionals: a meta-analysis of techniques to improve response. Eval Health Prof. 2013;36:382–407. doi: 10.1177/0163278713496425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.