Abstract

Background

Over the past several decades, there have been advances in diagnosis and treatment of neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) disease. There has been no recent comprehensive evaluation of the impact of these advances on the management and outcomes for neonates with HSV.

Methods

Clinical data for initial presentation, treatment, and outcomes were abstracted from medical records of neonates with HSV treated at Seattle Children’s Hospital between 1980 and 2016.

Results

One hundred thirty infants with a diagnosis of neonatal HSV were identified. Between 1980 and 2016, high-dose acyclovir treatment for neonatal HSV infection increased from 0% to close to 95%, with subsequent decrease in overall HSV-related mortality from 20.9% to 5.6%. However, even among infants treated with high-dose acyclovir, mortality was 40.9% for infants with disseminated (DIS) disease, and only 55% of infants with central nervous system (CNS) disease were without obvious neurologic abnormalities at 24 months. Over the study period, the time between initial symptoms and diagnosis decreased. Skin recurrences were more common with HSV-2 than HSV-1 (80% vs 55%; P = .02) and in infants with lesions at initial diagnosis (76% vs 47%; P = .02).

Conclusion

Changes in the standard of care for management of neonatal HSV disease have led to improvements in timeliness of diagnosis and outcome but mortality in infants with DIS disease and neurologic morbidity in infants with CNS disease remain high. Future research should focus on prevention of perinatal infection and subsequent recurrences.

Keywords: HSV, neonatal herpes, neonates

Modern era managementof neonatal HSV has improved outcomes but morbidity and mortality remain substantial. Skin recurrences are common, particularly in infants with lesions at initial presentation. There is a need for continued research focused on prevention of perinatal infection.

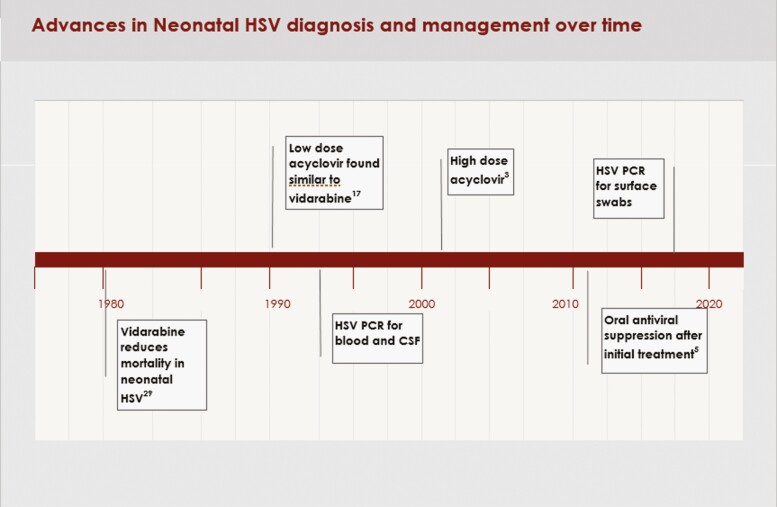

Despite advances in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection continues to result in significant mortality and long-term morbidity. The global estimate of the incidence of neonatal HSV is 10 cases/100000 live births or approximately 14000 cases/year, with 0.82 deaths/100000 births in industrialized countries [1, 2]. It has been 20 years since the Infectious Disease Collaborative Antiviral Study Group (ID-CASG) demonstrated the safety and efficacy of high-dose (HD) acyclovir for treatment of neonatal HSV [3] and published a comparison of the presentation and outcome of the infants treated through 2 ID-CASG trials (low-dose, short-duration acyclovir vs high-dose, longer-duration acyclovir) [4]. In 2011, the group also demonstrated improved neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants provided with 6 months of oral acyclovir suppression after the initial infection [5]. Subsequently, treatment with intravenous (IV) acyclovir at 60mg/kg/day (14 days for skin-eye-mouth [SEM] disease and a minimum of 21 days for disseminated [DIS] and central nervous system [CNS] disease) followed by oral acyclovir suppression has become standard of care for infants diagnosed with HSV in the neonatal period [6]. Contemporaneously with these treatment advances, the use of HSV DNA PCR to assist with diagnosis of neonatal HSV has also increased [7–9] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Advances in neonatal HSV diagnosis and management over time. Abbreviation: HSV, herpes simplex virus.

We report on 37 years of experience treating neonatal HSV disease at our center; a time that has spanned advances in the diagnosis and treatment of neonatal HSV disease. We examine changes in presentation, disease classification, viral type, mortality, and outcomes at 24 months. We also assess the impact of acyclovir suppression on skin recurrences and the need for re-admission for IV antiviral therapy.

METHODS

Patient Population

After Institutional Review Board approval, medical records of infants treated at Seattle Children’s Hospital (SCH) for virologically confirmed HSV infection during the neonatal period between 1980 and 2016 were abstracted. Infants were considered to have confirmed HSV infection if surface (nasopharynx, conjunctiva, lesions) cultures were positive for HSV or HSV DNA was detected in blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by PCR, along with symptoms consistent with neonatal HSV disease. Methods for HSV culture, PCR, and viral typing have been previously described [10–14]. At our institution, PCR for HSV in the CNS and blood was available in 1995. Case report forms were used to extract demographic characteristics, maternal history, birth history, clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes, as well as laboratory evaluations. Antiviral treatment and clinical course after hospital discharge was abstracted from clinic notes. Infant infection was classified as SEM, CNS, or DIS disease according to established criteria [15–17] (Supplementary Appendix). Infants with DIS infection were classified as DIS whether or not they had concurrent clinical CNS disease.

Developmental outcomes were determined by a review of SCH hospitalizations and clinic visits subsequent to the initial treatment of neonatal HSV infection. Follow-up visits were offered to all children upon hospital discharge. Children were classified as neurologically normal at follow-up if they were meeting age-appropriate milestones with no overt evidence of cognitive or motor impairment. Children with impairments were further classified as having mild, moderate, or severe impairment (Supplementary Appendix). Results of formal developmental testing were utilized in the assessment of impairment when available. Infants that died during the initial hospitalization for treatment of neonatal HSV were considered to have HSV-related mortality. Skin lesion recurrences were based on caregiver reports and clinic visit records.

Records were reviewed retrospectively for all infants born prior to 2011. Infants born after March 2011 were enrolled into a prospective cohort study after informed consent was obtained. Fifty-two infants had participated in ID-CASG studies [3, 5, 17]. A subset of these infants were also included in a report of outcome of CNS disease by viral type [18]. Data from 63 infants were included in a previous report on the relationship between blood and CSF PCR and outcome in infants with neonatal HSV [7]. Three infants were included in a review of outcome after primary gingivostomatitis during pregnancy [19].

Management

HD acyclovir was defined as 60mg/kg/day IV for a minimum of 21 days for CNS and DIS disease and a minimum of 14 days for SEM disease. Initial suppressive therapy was defined as oral acyclovir (300mg/m2 three times a day) started after completion of IV acyclovir and continued for at least 4 weeks. Repeat evaluation, including viral culture of the lesion, blood HSV PCR (if available), CSF analysis, and empiric IV acyclovir pending results, was conducted with the first skin recurrence within 6 months of completion of the initial treatment course [20]. Infants with negative results for blood PCR (when available) and CSF studies were usually transitioned to oral acyclovir (20mg/kg/dose 4 times daily). Subsequent recurrences were generally treated with oral acyclovir. Infants with CNS disease who subsequently presented with symptoms concerning for a CNS recurrence underwent lumbar puncture and initiated empiric IV acyclovir pending CSF results regardless of age. Infants who continued to have frequent skin recurrences were offered the option of either suppressive oral acyclovir or continued episodic treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized descriptively using counts with percentages and means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), as applicable. Continuous data were assessed for normality using histograms and QQ plots. Changes in presentation and treatment outcomes over time were assessed by decade of diagnosis (1980s-2010s). Data were also assessed by presentation category (DIS, CNS, or SEM) and virus type (HSV-1 vs HSV-2). Statistical comparisons in categorical outcomes over time were made using Cochran-Armitage tests for trend.

Treatment outcomes were analyzed descriptively and were also assessed using multivariable logistic regression. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% CIs were calculated to assess the receipt of HD acyclovir on the odds of death from HSV and of normal function at 24 months of age, adjusted for class and virus type. Only patients with CNS and DIS disease were included in logistic regression analyses, as all patients with SEM reported survival with normal function. Normal function at 24 months was based on recorded assessments between 18 and 30 months of age; a sensitivity analysis including patients with functional assessments conducted after this time window was assessed.

Rates of skin recurrence were calculated among patients with at least 30 days of follow-up by virus type, receipt of suppression therapy (yes/no), and the presence of lesions at presentation or during initial treatment (yes/no). Need for re-treatment with IV acyclovir within the first 6 months was also assessed. The proportion of patients experiencing recurrences by viral type and the presence of lesions at baseline were compared using chi-square tests.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

One hundred thirty infants with virologically documented HSV infection were included in this analysis. Four infants treated for neonatal HSV after 2011 were excluded due to lack of parental consent (3 with HSV-1 SEM and 1 with HSV-2 DIS disease who died shortly after admission). Demographics and clinical characteristics of the infants are presented in Table 1 including distribution of disease classification and viral type. Prematurity was most common among infants with CNS disease (34%). Of the infants with DIS disease who survived their initial infection, 9 (47%) also had CNS involvement. Overall HSV-related mortality was 16%, with the highest mortality of 48.7% in the infants with DIS disease. Two (4.5%) infants with HSV-2 associated CNS disease died in the neonatal period: neither was treated with HD acyclovir. Five additional infants died during the follow-up period; 2 infants (one each with CNS and DIS disease) died from presumed sudden infant death syndrome, and 3 infants died of complications related to severe developmental impairment (2 with CNS and 1 DIS disease). Of 109 infants who survived initial infection, 88 were followed for at least 6 months, 75 for ≥12 months, and 50 for ≥24 months (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| N = 130 | |

|---|---|

| Sex, male (%) | 70 (53.9%) |

| Race | |

| White | 96 (73.9%) |

| Black | 9 (6.9%) |

| Native American/Pacific Islander | 3 (2.3%) |

| Hispanic | 6 (4.6%) |

| Other | 5 (3.9%) |

| Unknown | 11 (8.5%) |

| Mean gestational age in weeks (SD) | 38.1 (3.3)

Range: 24-43 |

| Classification | |

| CNS | 44 (33.9%) |

| DIS | 39 (30.0%) |

| SEM | 47 (36.2%) |

| Viral type | |

| HSV-1 | 54 (41.5%) |

| HSV-2 | 73 (56.2%) |

| Unknown | 3 (2.3%) |

| Estimated gestational age <37 weeksa | |

| CNS | 15 (34.1%) |

| DIS | 8 (20.5%) |

| SEM | 8 (17.0%) |

| Skin lesions present at initial diagnosis | |

| By classification | |

| CNS | 29 (65.9%) |

| DIS | 14 (35.9%) |

| SEM | 40 (85.1%) |

| By viral type | |

| HSV-1 | 44 (81.5%) |

| HSV-2 | 37 (50.7%) |

| Treated with high-dose acyclovir | 69 (53.1%) |

| Mortality, overall | 26 (20.0%) |

| Mortality, HSV-relatedb | |

| Total | 21 (16.2%) |

| CNS | 2 (4.5%) |

| DIS | 19 (48.7%) |

| SEM | 0 (0%) |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; DIS, disseminated; HSV-1, herpes simplex virus 1; HSV-2, herpes simplex virus 2; SD, standard deviation; SEM, skin-eye-mouth.

One CNS patient of unknown gestational age.

Died during initial hospitalization.

Skin lesions were present at initial diagnosis in 65.9% of infants with CNS disease, 35.9% infants with DIS disease, and 85.1% of those with SEM disease (Table 1). Infants with SEM disease who did not present with lesions (n = 7) presented with fever (n = 2), history of maternal lesions at delivery (n = 4), or conjunctivitis (n = 1). An additional 7 infants developed lesions within 4 days of diagnosis and initiation of treatment (1 CNS, 2 DIS, 4 SEM). Five of these infants were treated with either vidarabine or low-dose acyclovir. Mean age at diagnosis was greater for CNS infants without skin lesions (19 days, SD 6.0) than for infants who had skin lesions at diagnosis (13.9 days, SD 7.2), whereas the opposite was true for DIS infants in whom median age at diagnosis without skin lesions was 9 days (SD 6.0) vs 10.5 days (SD 3.7) with skin lesions. Infants infected with HSV-1 were more likely to have skin lesions at diagnosis than were infants infected with HSV-2 (81.5% vs 50.7%, respectively, P < .001). There were 2 HSV-2 infected infants with in-utero infection (Supplementary Appendix).

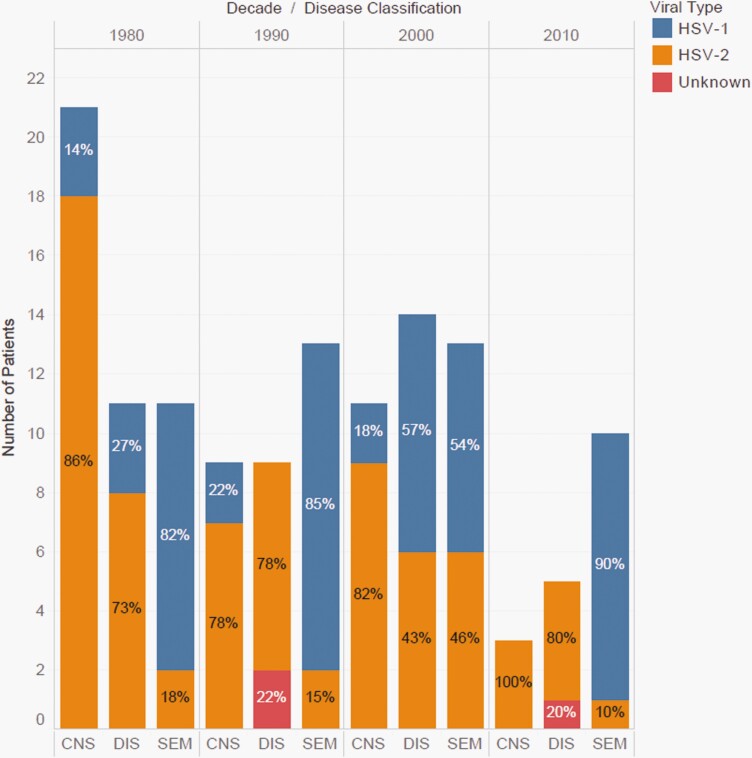

Clinical Presentation and Management by Decade

Infants with SEM disease were more likely to be infected with HSV-1 (76.6%), while infants with DIS and CNS disease were infected more frequently with HSV-2 (64% and 84%, respectively). This remained fairly consistent throughout the decades (Figure 2). Table 2 describes changes in infection characteristics over time by decade. There was a trend toward a greater proportion of infections due to HSV-1 over time (P = .19). The proportion of patients with CNS infections decreased over time, while SEM infections increased, relatively. The time between symptoms and diagnosis decreased. The age at diagnosis decreased for infants with DIS but increased for infants with CNS disease. Overall, 69 (53%) infants were treated with HD acyclovir, 39 (30%) received acyclovir doses of less than 60mg/kg/day (15, 30, or 45mg/kg/day), 16 (12%) were treated with vidarabine, 3 (2%) DIS infants died prior to starting antivirals, and for 3 (2%) the acyclovir dosage was unknown. In accordance with guidelines, the percentage of infants receiving treatment with HD and suppressive acyclovir increased over the 4 decades. There was a trend toward lower HSV-related mortality over time, from 20.9% (9 of 43) in the 1980s to 5.6% (1 of 18) in the most recent period (P = .11). Twelve of the surviving 17 infants born between 2010 and 2016 received initial suppressive therapy. Of the remaining, 1 initiated suppression but was lost to follow-up, 3 received antiviral suppression but not immediately after discontinuing initial IV acyclovir. One family declined suppressive therapy.

Figure 2.

Patterns in viral type (HSV-1 vs HSV-2) and disease classification (CNS, DIS, SEM) by decade. Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; DIS, disseminated; HSV-1, herpes simplex virus 1; HSV-2, herpes simplex virus 2; SEM, skin-eye-mouth.

Table 2.

Clinical and Virologic Characteristics by Decade

| 1980-1989

N = 43 |

1990-1999

N = 31 |

2000-2009

N = 38 |

2010-2016

N = 18 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral type | ||||

| HSV-1 | 15 (34.9%) | 13 (41.9%) | 17 (44.7%) | 9 (50.0%) |

| HSV-2 | 28 (65.1%) | 16 (51.6%) | 21 (55.3%) | 8 (44.4%) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Disease classification | ||||

| CNS | 21 (48.8%) | 9 (29.0%) | 11 (29.0%) | 3 (16.7%) |

| DIS | 11 (25.6%) | 9 (29.0%) | 14 (36.8%) | 5 (27.8%) |

| SEM | 11 (25.6%) | 13 (41.9%) | 13 (34.2%) | 10 (55.6%) |

| Length of time from symptoms to diagnosis, in days, mean (SD) | ||||

| CNS | 6.3 (5.1) | 5.7 (4.8) | 7.9 (9.3) | 3.7 (4.0) |

| DIS | 6.5 (4.7) | 8.6 (9.4) | 2.5 (2.0) | 2.6 (2.9) |

| SEM | 6.5 (7.0) | 4.2 (6.8) | 3.7 (2.7) | 3.8 (1.9) |

| Age at diagnosis, in days, mean (SD) | ||||

| CNS | 13.4 (7.2) | 15.0 (7.6) | 19.3 (6.2) | 20.3 (3.1) |

| DIS | 11.6 (3.7) | 11.4 (8.9) | 7.6 (2.7) | 7.0 (1.9) |

| SEM | 12.3 (5.6) | 10.8 (8.0) | 8.5 (4.3) | 10.3 (4.3) |

| Received high-dose acyclovir | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (51.6%) | 36 (94.7%) | 17 (94.4%) |

| Initiated immediate suppression therapy | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.5%) | 1 (2.6%) | 14 (77.8%) |

| Suppression therapy for ≥4 weeksa | – | 1 (50%) | 0 (0.0% | 12 (85.7%) |

| Mortality from HSV | ||||

| CNS | 2 (9.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| DIS | 7 (63.6%) | 6 (66.7%) | 5 (35.7%) | 1 (20%) |

| SEM | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 9 (20.9%) | 6 (19.4%) | 5 (13.2%) | 1 (5.6%) |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; DIS, disseminated; HSV-1, herpes simplex virus 1; HSV-2, herpes simplex virus 2; SD, standard deviation; SEM, skin-eye-mouth.

Twelve infants received 6 months.

Management and Outcomes

No infants presenting with SEM disease died and all with follow-up were without obvious neurological abnormalities at 24 months of age (Table 3). Outcomes were improved for infants treated with HD acyclovir for both HSV-related mortality (adjusted OR: 0.55; 95% CI: 0.15-2.03) and for normal function at 24 months (adjusted OR: 4.33; 95% CI: 0.94-20.06). However, mortality for DIS infants was still 40.9% and only 55% of CNS infants were without obvious neurologic abnormalities at 24 months. The sensitivity analysis including infants with functional assessments conducted after 24 months revealed similar outcomes (not shown). HSV-2-infected infants with CNS disease had worse neurologic outcome than those with HSV-1 infection; 14 of 22 (63%) HSV-2-infected infants had neurologic abnormalities compared with 1 of 4 (25%) infants with HSV-1 infection. Of the 23 infants with neurologic impairment documented at or after 24 months, 14 (61%), 6 (26%), and 3 (13%) had severe, moderate, and mild impairment, respectively. There did not appear to be an association between degree of impairment and type or dose of initial antiviral treatment, however, the study was underpowered to assess this.

Table 3.

Mortality and Neurologic Outcome by Disease Classification and Treatment Type

| CNSa | DISa | SEM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Through 6 Months Available | High-Dose Acyclovir

N = 16 |

Other Treatmentb N = 24 |

High-Dose Acyclovir

N = 20 |

Other Treatmentb N = 16 |

High-Dose Acyclovir

N = 20 |

Other Treatmentb N = 13 |

| Survival to at least 6 months | 15c (93.8%)d | 22 (91.7%) | 11e (55.0%) | 6 (37.5%)d | 20f (100.0%) | 13 (100.0%) |

| Assessed at 24 months | 11 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 |

| Normal 24-month assessment | 6 (54.6%) | 5 (33.3%) | 5 (100.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 7 (100.0%) | 7 (100.0%) |

Abbreviations: ACV, acyclovir; CNS, central nervous system; DIS, disseminated; HD, high-dose; IV, intravenous; SEM, skin-eye-mouth.

Odds ratios (OR) (95% CI) of mortality and normal neurologic outcome at 24 months with exposure to HD ACV vs not (CNS and disseminated patients only): ORs mortality from HSV, unadjusted 0.97 (0.34-2.74); adjusted 0.55 (0.15-2.03): ORs normal function at 24 months, unadjusted 4.09 (1.01-16.58); adjusted 4.33 (0.94-20.06)—adjusted for classification (disseminated vs CNS) and virus type (HSV-1 vs HSV-2).

Low-dose acyclovir, vidarabine, or no treatment.

Two infants received oral suppressive acyclovir immediately after initial IV acyclovir treatment.

One CNS and 1 DIS infant died prior to 6 months due to non-HSV-related causes.

One infant received oral suppressive acyclovir immediately after initial IV acyclovir treatment.

Ten infants received oral suppressive acyclovir immediately after initial IV acyclovir treatment.

Skin Recurrences

Data on rate of skin lesion recurrences subsequent to initial antiviral treatment are available for 82 (63%) infants (median follow-up of 2 years, range 0.12-13.4 years). Skin recurrences were significantly more common in infants infected with HSV-2 than HSV-1 (80% vs 54.5%, P = .02). Infants who had skin lesions at the time of initial presentation were more likely to have skin recurrences than those who did not: 76.2% vs 47.4%, P < .02 (Table 4). Almost all HSV-2-infected infants with skin lesions at presentation had subsequent skin recurrences (93.8%) while 52.9% of those without skin lesions at initial presentation developed skin recurrences during follow-up. Neither initial antiviral treatment type nor use of oral suppressive acyclovir post-diagnosis (including initial and subsequent suppression) affected the subsequent recurrence rate after suppressive acyclovir was stopped (data not shown). The median time after stopping initial acyclovir treatment and first skin recurrence was 14 days (range 4-120 days) for infants not started immediately on oral acyclovir suppression. Three of the infants on initial suppressive therapy had recurrences upon discontinuation of oral acyclovir at 14, 40, and 40 days.

Table 4.

Yearly Skin Recurrence Rates by Viral Type and the Presence of Lesions at Presentationa

| All | HSV-1 | HSV-2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Lesion at Presentation | Total | Lesion at Presentation | Total | Lesion at Presentation | ||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||

| Recurrence rate availableb | 82 | 63 | 19 | 33 | 31 | 2 | 49 | 32 | 17 |

| Any recurrence during follow-up | 57 (70%) | 48 (76.2%) | 9 (47.4%) | 18 (54.5%) | 18 (58.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 39 (80%) | 30 (93.8%) | 9 (52.9.0%) |

| Recurrence ratec | 5.6 (2.4-8.3)

0.1-20.8 |

5.3 (2.2-8.1)

0.2-20.8 |

5.6 (2.4-10.2)

0.1-18.3 |

2.5 (0.6-6.3)

0.2-8.3 |

2.5 (0.6-6.3)

0.2-8.3 |

– | 6.2 (2.9-11.8)

0.1-20.8 |

6.5 (3.3-11.8)

0.8-20.8 |

5.6 (2.4-10.2)

0.1-18.3 |

Abbreviations: HSV-1, herpes simplex virus 1; HSV-2, herpes simplex virus 2; IQR, interquartile range.

At the time of initial diagnosis or during initial therapy.

At least 30 days of follow-up data available, excluding time on suppressive therapy.

Median (IQR) and range, among those with at least 1 recurrence, annualized.

Follow-up data for at least 4 weeks are available for 13 infants who received oral acyclovir suppression immediately following initial IV treatment (12 were followed for 6 months). Seventeen additional infants received oral acyclovir suppression later at some point after hospital discharge after they experienced several skin recurrences. Need for repeat evaluation and treatment after hospital discharge was lower, though not significantly (P = .13), among patients on initial suppressive therapy: only 2 infants (15.4%) underwent repeat workup and IV acyclovir within the first 6 months of life, one due to a breakthrough lesion and the other due to parental concern of possible seizure activity. Of the 96 infants who survived their initial hospitalization and did not receive initial suppressive acyclovir, 37 (38.5%) were readmitted at least once for repeat evaluation and preemptive IV acyclovir within the first 6 months of life due to concerns for recurrence. One infant with HSV-2 CNS disease who appeared neurologically normal after his initial infection had 2 early skin recurrences after which he was placed on suppressive acyclovir until 6 months of age. He subsequently had a skin and CNS recurrence shortly after stopping suppression resulting in severe neurologic morbidity.

DISCUSSION

Our study summarizes the characteristics of neonatal HSV infection over 4 decades and, importantly, documents improvements in outcomes with the introductions of initial HD acyclovir and subsequent oral antiviral suppressive therapy for the prevention of recurrences. In this time period, we noted a trend toward fewer infants with CNS disease and more with SEM disease. This may be an artifact of the small numbers but could also be related to a relative increase in the percentage of infections due to HSV-1, which is more likely to be associated with SEM disease. This shift is also consistent with the epidemiology in our region as there had been a significant decrease in first-episode genital infections due to HSV-2 between 1993 and 2014 in the Seattle/King County area while HSV-1 infections have remained stable [21]. Unlike what was noted in the ID-CASG review [4], there has been an overall decrease in time between initial symptoms and diagnosis, most noticeable in the infants with DIS. This may reflect greater awareness of HSV as a cause of neonatal sepsis and availability of PCR (CSF and blood) for diagnosis, resulting in more rapid workup and empiric treatment with IV acyclovir [7–9]. The age at diagnosis decreased for infants with DIS, was stable in infants with SEM, but increased in infants with CNS disease. The reason for the latter is unclear but was also noted in the 2 decades reviewed by Kimberlin et al [4].

As expected, more infants were treated with HD acyclovir in the last 2 decades, subsequent to the results of the ID-CASG HD acyclovir study [3]. Consistent with the findings in this trial, mortality for infants with DIS disease and developmental outcome for infants with both CNS and DIS disease were improved with the use of HD acyclovir compared to those receiving lower doses or alternative antiviral regimens. As only 2 infants in our cohort who received initial suppression had CNS disease, it was not possible to assess the additional benefit of early oral suppression on neurologic outcome with this dataset. Overall mortality decreased over time and in the most recent decade was similar to that reported in 2 recent epidemiologic studies of neonatal HSV in the United States [22, 23]. Nevertheless, there was still significant morbidity and mortality in the CNS and DIS infants, respectively. HSV PCR for testing of surface samples was not available during most of the period of our review. Availability of rapid PCR results from surface swabs [9, 24] may result in earlier diagnosis and improved outcomes, but we were unable to assess this with this dataset.

Following the results of the CASG oral suppression study in 2011 [5], most infants were offered antiviral suppression for 6 months after their initial IV treatment. Based on the ID-CASG protocol [20], infants with their first recurrence within the first 6 months of life were evaluated and hospitalized for IV acyclovir pending results of their CSF analysis. The decrease in early skin recurrences and need for subsequent evaluation and re-admission for IV acyclovir in the first 6 months among those infants on initial suppression was striking. As the cost of a short hospital stay due to infection evaluation in an infant is approximately $6000 at our institution, oral acyclovir suppression results in considerable cost savings and thus supports the recommendation that it be offered even for infants with SEM disease. Interestingly, having skin lesions at initial presentation was predictive for future skin lesion recurrences. As has been shown previously [15, 25], infants with HSV-2 disease were more likely to have frequent skin recurrences. It is possible that initial acyclovir suppression may impact development of subsequent skin recurrences; we were underpowered to assess this. A prospective study would be necessary to further elucidate this effect.

Consistent with what has been found in other studies, HSV-2 was more likely to cause CNS disease and lead to neurologic morbidity than HSV-1 [3, 15, 16, 18, 26]. Ongoing diligence in infants with HSV-2 CNS infection, in particular, is warranted as late recurrences can result in additional CNS morbidity as demonstrated by 1 infant in our cohort who experienced a devastating CNS recurrence after discontinuing oral acyclovir. Similar reports have been described in the literature [27, 28].

This study has several important limitations. Significantly, most of the data were collected via retrospective chart review, and most infants were not followed beyond infancy per a specific schedule. While data on presentation, initial antiviral therapy, and follow-up admissions for IV acyclovir were largely complete, there was a variable length of follow-up after initial hospitalization. Not surprisingly, infants that had fewer complications had less follow-up, as families likely preferred to obtain further follow-up locally rather than at a referral center. Thus our cohort may be skewed toward infants with more severe outcomes.

Information on HSV skin recurrences was based on parental recall and those infants with frequent recurrences were more likely to seek follow-up in infectious disease clinic. Although many infants had follow-up information available beyond 24 months, these infants tended to be those with more significant HSV-related morbidity. Therefore, we used a cutoff of 24 months (±6 months) follow-up for determination of neurologic outcome. A few infants had formal developmental testing, but for most the determination of neurologic outcome was based on physician assessment, physical examination, and parental report; thus, mild neurologic abnormalities may have been missed.

There were relatively fewer infants in the dataset from the last decade, even when considering this was not a full decade. This is due in part to the switch to prospectively collected data, which necessitated excluding infants whose parents did not consent to participation. It also could reflect fewer referrals to our institution due to a greater comfort level with neonatal HSV diagnosis and management at community hospitals. Unfortunately, the smaller numbers in the most recent decade coincided with the introduction of routine initial suppressive therapy, precluding analysis of its contribution to improved neurologic outcome. Finally, while this is a relatively large cohort for neonatal HSV, the number of patients in subgroups is still small, particularly when trying to parse outcomes by classification and viral type. Thus, many of the trends noted in this analysis did not meet statistical significance, likely due to lack of power.

CONCLUSION

Over the course of 4 decades, changes in the standard of care for diagnosis and management of neonatal HSV disease have led to improvements in timeliness of diagnosis and in outcomes. HSV-2 continues to cause more CNS disease and morbidity than HSV-1 infection. Oral antiviral suppression has led to decreases in early recurrences and need for re-hospitalization in the first 6 months of life. These data particularly support the use of acyclovir suppression in infants with skin lesions at initial presentation. However, despite more rapid diagnosis and improved management, neonatal HSV infection continues to result in unacceptably high morbidity and mortality. Future research should focus on prevention of perinatal infection in order to prevent the tragic outcomes of this infection for newborns and their families.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Financial support. This study was supported by NIH grant P01 AI030731 and a Seattle Children’s Research Institute Faculty Research Fund grant.

Role of funder/sponsor. The NIH grant P01 AI030731 and the Seattle Children’s Research Institute Faculty Research Fund grant had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed..

Contributor Information

Ann J Melvin, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Infectious Disease, University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Kathleen M Mohan, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Infectious Disease, University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Surabhi B Vora, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Infectious Disease, University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Stacy Selke, Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Erin Sullivan, Biostatistics Epidemiology and Analytics for Research Core, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Anna Wald, Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA; Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA; Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA; Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

References

- 1. Looker KJ, Magaret AS, May MT, et al. First estimates of the global and regional incidence of neonatal herpes infection. Lancet Glob Health 2017; 5:e300–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sampath A, Maduro G, Schillinger JA. Infant deaths due to herpes simplex virus, congenital syphilis, and HIV in New York City. Pediatrics 2016; 137:e20152387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kimberlin DW, Lin CY, Jacobs RF, et al. ; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. Safety and efficacy of high-dose intravenous acyclovir in the management of neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. Pediatrics 2001; 108:230–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kimberlin DW, Lin CY, Jacobs RF, et al. ; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. Natural history of neonatal herpes simplex virus infections in the acyclovir era. Pediatrics 2001; 108:223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kimberlin DW, Whitley RJ, Wan W, et al. Oral acyclovir suppression and neurodevelopment after neonatal herpes. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1284–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Melvin AJ, Mohan KM, Schiffer JT, et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid herpes simplex virus levels at diagnosis and outcome of neonatal infection. J Pediatr 2015; 166:827–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cantey JB, Mejías A, Wallihan R, et al. Use of blood polymerase chain reaction testing for diagnosis of herpes simplex virus infection. J Pediatr 2012; 161:357–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Samies N, Jariwala R, Boppana S, Pinninti S. Utility of surface and blood polymerase chain reaction assays in identifying infants with neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2019; 38:1138–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lafferty WE, Krofft S, Remington M, et al. Diagnosis of herpes simplex virus by direct immunofluorescence and viral isolation from samples of external genital lesions in a high-prevalence population. J Clin Microbiol 1987; 25:323–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Langenberg A, Zbanyszek R, Dragavon J, et al. Comparison of diploid fibroblast and rabbit kidney tissue cultures and a diploid fibroblast microtiter plate system for the isolation of herpes simplex virus. J Clin Microbiol 1988; 26:1772–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jerome KR, Huang ML, Wald A, et al. Quantitative stability of DNA after extended storage of clinical specimens as determined by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40:2609–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Magaret AS, Wald A, Huang ML, et al. Optimizing PCR positivity criterion for detection of herpes simplex virus DNA on skin and mucosa. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:1618–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Corey L, Huang ML, Selke S, Wald A. Differentiation of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in clinical samples by a real-time Taqman PCR assay. J Med Virol 2005; 76:350–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whitley R, Arvin A, Prober C, et al. Predictors of morbidity and mortality in neonates with herpes simplex virus infections. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. N Engl J Med 1991; 324:450–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kimberlin DW, Lakeman FD, Arvin AM, et al. Application of the polymerase chain reaction to the diagnosis and management of neonatal herpes simplex virus disease. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. J Infect Dis 1996; 174:1162–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Whitley R, Arvin A, Prober C, et al. A controlled trial comparing vidarabine with acyclovir in neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. N Engl J Med 1991; 324:444–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Corey L, Whitley RJ, Stone EF, Mohan K. Difference between herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 neonatal encephalitis in neurological outcome. Lancet 1988; 1:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Healy SA, Mohan KM, Melvin AJ, Wald A. Primary maternal herpes simplex virus-1 gingivostomatitis during pregnancy and neonatal herpes: case series and literature review. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2012; 1:299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. A placebo-controlled phase III evaluation of suppressive therapy with oral acyclovir suspension following neonatal herpes simplex virus infections involving the central nervous system. Accessed September 19, 2020. https://www.nejm.org/doi/suppl/10.1056/NEJMoa1003509/suppl_file/nejmoa1003509_protocol.pdf

- 21. Dabestani N, Katz DA, Dombrowski J, Magaret A, Wald A, Johnston C. Time trends in first-episode genital herpes simplex virus infections in an urban sexually transmitted disease clinic. Sex Transm Dis 2019; 46:795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Donda K, Sharma M, Amponsah JK, et al. Trends in the incidence, mortality, and cost of neonatal herpes simplex virus hospitalizations in the United States from 2003 to 2014. J Perinatol 2019; 39:697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mahant S, Hall M, Schondelmeyer AC, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection among Medicaid-enrolled children: 2009-2015. Pediatrics 2019; 143:e20183233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dominguez SR, Pretty K, Hengartner R, Robinson CC. Comparison of herpes simplex virus PCR with culture for virus detection in multisource surface swab specimens from neonates. J Clin Microbiol 2018; 56:e00632-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kimura H, Futamura M, Ito Y, et al. Relapse of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2003; 88(6):F483–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kimura H, Ito Y, Futamura M, et al. Quantitation of viral load in neonatal herpes simplex virus infection and comparison between type 1 and type 2. J Med Virol 2002; 67:349–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kato K, Hara S, Kawada J, Ito Y. Recurrent neonatal herpes simplex virus infection with central nervous system disease after completion of a 6-month course of suppressive therapy: case report. J Infect Chemother 2015; 21:879–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Henderson B, Kimberlin DW, Forgie SE. Delayed recurrence of herpes simplex virus infection in the central nervous system after neonatal infection and completion of six months of suppressive therapy. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2017; 6:e177–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.