Abstract

Introduction:

As rates of overdose and substance use disorders (SUDs) increase, medical schools are starting to incorporate more content on SUDs and harm reduction in undergraduate medical education (UME). Initial data suggest these additions may improve medical student knowledge and attitudes toward patients with SUDs; however, there is no standard curriculum.

Methods:

This project uses a six-step approach to UME curricular development to identify needs and goals regarding SUDs and opioid overdose at a large single-campus medical school in the United States. We first developed and delivered a pilot curriculum to a small group of medical students. Pilot results and a larger survey led to implementing a one-hour Opioid Overdose Prevention and Response (OOPR) Training for first-year students. Effects of training were tracked using baseline and post-training surveys examining knowledge and attitudes toward opioid overdose and patients with SUDs.

Results:

Needs assessment indicated desire and need for training. The pilot study (N=66) resulted in significantly improved knowledge regarding opioid overdose; 100% of students enjoyed training and believed others should receive it. The larger replication study surveyed all incoming students (N=266) to gauge initial knowledge and experiences with these topics. Results prompted enhancement of the OOPR Training curriculum, which was delivered to half of the first-year class. Post-training survey results replicated the pilot study findings. The majority (95.2%) of students enjoyed training and 98.4% believed all students should receive it.

Conclusion:

Delivering a thorough curriculum on SUDs and harm reduction in UME is critical. Although many schools are implementing training, there is no standard curriculum. We outline a low-resource training intervention for OOPR. Our findings identified key features to include in these UME curricula. This approach provides a replicable template for schools seeking to develop brief educational interventions and identify essential content for curricula in SUDs and harm reduction.

Keywords: Opioid overdose, curriculum development, harm reduction, undergraduate medical education

Introduction

As the global drug crisis continues and opioid overdose remains a leading cause of accidental death in the USA1, medical schools have begun incorporating more educational content on substance use disorders (SUDs), especially opioid use disorder (OUD), into their curricula.2,3 Modifying an existing medical school curriculum to address the pathophysiology, psychology, prevention, treatment, social determinants, and stigma of SUDs requires time and resources. Thus, focusing on opioid overdose prevention and response (OOPR) offers a reasonable starting point to address a lifesaving intervention that can be taught efficiently. Across the country, medical schools have begun to take a stepwise approach to advancing SUD education by integrating specific trainings. Some have focused on expanding education around medications for OUD and preparing students to eventually prescribe medications like buprenorphine4–7; while others have focused on harm reduction and overdose prevention.8–10 Furthermore, medical students have expressed interest in learning how they can assist this vulnerable population, which helps them educate patients and contribute ideas to their clinical team.11,12

Within the USA, core medical education content requirements are primarily dictated by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) and first year medical students are expected to enter training with a baseline of knowledge and competencies.13 Students in the USA enter medical school after completing a Bachelor’s degree and required pre-medical school classes that include the basic sciences.14 Although much is changing in medical education, medical students are typically expected to complete 18–24 months of pre-clinical training (M1 and M2 years) prior to completing 24–30 months of clinical rotations (M3 and M4 years). After completing these 4-years in Undergraduate Medical Education (UME) students earn a Doctor of Medicine (MD) and enter residency training in their chosen specialty. Although each medical school has the flexibility to establish its own curriculum, this is done within the framework of general competencies required for LCME accreditation.15

The Medical Education Working Group in Massachusetts established OOPR as a core competency for medical students graduating from the state’s medical schools.16 Importantly, opioid overdose prevention and response must be considered not only as part of training related to SUDs but also as part of training related to medication management, especially for patients with chronic pain. It is vital that trainings regarding overdose prevention highlight that overdoses can occur in any patient population; therefore, all students regardless of intended specialty should be prepared to counsel patients about risk and to respond to overdose situations. One medical school program has incorporated OOPR training during mandatory basic life support training for first-year students at the New York University School of Medicine17 while another has initiated a mandatory harm reduction workshop for clerkship medical students at Yale University.9 Providing OOPR education has had positive impacts in multiple settings. Medical residents and physician assistant trainees at the University of Cincinnati demonstrated improvement in knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy in an interprofessional training session on naloxone use,18 while pharmacy students at the University of Maryland improved their knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in opioid overdose response after completing a laboratory course.19 These findings were replicated at the undergraduate and graduate training levels, demonstrating the value of these brief interventions.2,10

Despite the need for increased medical education surrounding SUDs, pain, opioid use, and harm reduction, topics covered and educational approaches used in US medical schools are highly variable. The Wayne State University School of Medicine (WSUSOM) is updating its undergraduate medical training to expand a longitudinal curriculum on SUDs throughout all four years. Various models have been used to develop medical curricula. One popular approach uses a 6-step method: (1) Problem identification and general needs assessment, (2) Targeted needs assessment, (3) Goals and objectives, (4) Educational strategies, (5) Implementation, and (6) Evaluation and feedback.20 This paper describes how we developed, implemented, evaluated, and expanded an OOPR training program at the WSUSOM that can be replicated at medical schools across the country.

Methods

Pilot phase

Approach

Based on a general needs assessment, a Curriculum Task Force for Pain and SUDs was formed in 2017. The impetus for this task force came from the Vice Dean of Medical Education who, under the direction of the Dean of the medical school, composed an interdisciplinary group of pre-clinical and clinical faculty. The goal of this task force was to expand curriculum on the diagnosis and treatment of pain and SUDs. Concurrently, medical students recognized this deficit in training and clinical experiences and formed a student-led organization—Detroit vs. Addiction, which helped develop SUD-related clinical, volunteer, educational, and research opportunities for students. Efforts by this organization and curriculum task force members led to this large-scale project and curriculum enhancement. Initial targeted needs assessment using a voluntary survey distributed to all students in Spring 2018 provided preliminary insights into student knowledge and attitudes surrounding opioid overdose and patients with SUDs. Results of this survey prompted the focus on developing an expanded curriculum aimed at improving students’ knowledge about overdose risks and prevention, ability to respond to overdose, and attitudes toward patients with SUDs.

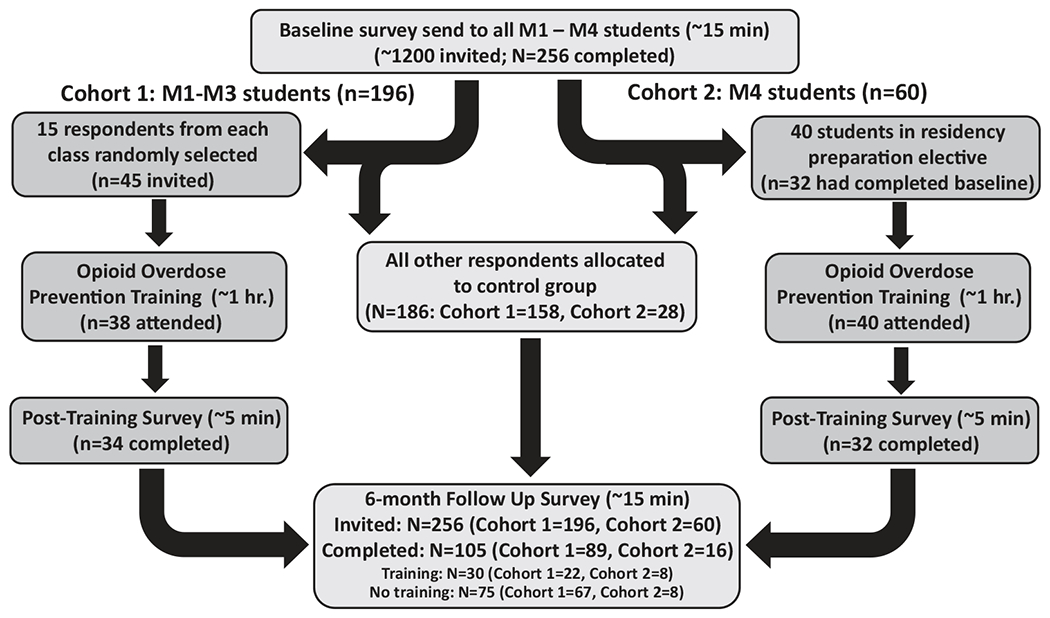

As a pilot program, we developed a one-hour interactive OOPR Training and invited students from all four years of medical school to attend. Training was divided into two cohorts constrained by scheduling requirements. Cohort 1 consisted of 34 students from years 1–3 who had expressed interest in receiving training; they completed training on April 26, 2019 and their attendance was entirely voluntary. Cohort 2 consisted of 32 fourth-year students who registered to receive the Residency Preparation Elective; they completed the training on April 23, 2019 and their attendance was required as part of their one-month elective. Figure 1 shows the overview of the pilot study and how many students were invited, attended and completed each section. For detailed pilot study methods, see Moses et al., under review.21

Figure 1.

Overview of pilot study design methods. Completion of the baseline survey was voluntary for all students. Training attendees from cohort 1 were selected randomly from students who had completed the baseline survey; attendance at the training was voluntary. Training attendees from cohort 2 were required to attend as part of a residency preparation elective. Due to expected “no-shows” at training and non-completion of surveys at each time point, the number of students included in the data analysis differs from the number invited to take part, and we indicate these differences below.

Overarching goals of delivering this lecture were to improve students’ knowledge and attitudes about OOPR, naloxone use and harm reduction for patients who use drugs, and reduce stigmatizing beliefs about patients with SUDs. We established key lecture concepts based on those commonly presented in community-based naloxone training programs22 but adapted them to provoke critical thinking in a medical student audience already familiar with fundamentals of anatomy and physiology. We targeted common myths surrounding overdose and SUDs and ensured students understood how to recognize evidence-based information regarding these topics and respond to misinformation.

Lecture structure

We provided students a one-page handout (see supplement) outlining opioid overdose signs, checking for patient responsiveness, recommendations for making a 911 call, and how to place a person in the recovery position, perform rescue breathing, and administer naloxone. Upon beginning the lecture, the facilitator asked students, “What is an opioid overdose?” and used probing questions until the group arrived at the correct pathophysiology. Next, she challenged students to list risk factors for overdose based on their new understanding of the pathophysiology. These risk factors included risks related to street substance use (e.g., purchasing drugs from a new dealer) and medical opioid use (e.g., concurrent prescriptions for sedating medications) to ensure students understood the varying populations at risk of overdose. In discussing each risk factor, she informed students of harm reduction approaches for mitigating each risk, and common misconceptions patients may have and how to address these beliefs. She distinguished between signs of opioid intoxication versus those of overdose to clarify the difference between when a person is merely intoxicated (i.e., “high”) from opioid use and therefore not in need of revival by naloxone versus when a person has overdosed and would therefore need to be given naloxone. This is an important distinction because using naloxone when a person is intoxicated but not overdosing can result in unnecessary, painful symptoms of withdrawal for that person and doing so may diminish their trust and willingness to engage with medical services.

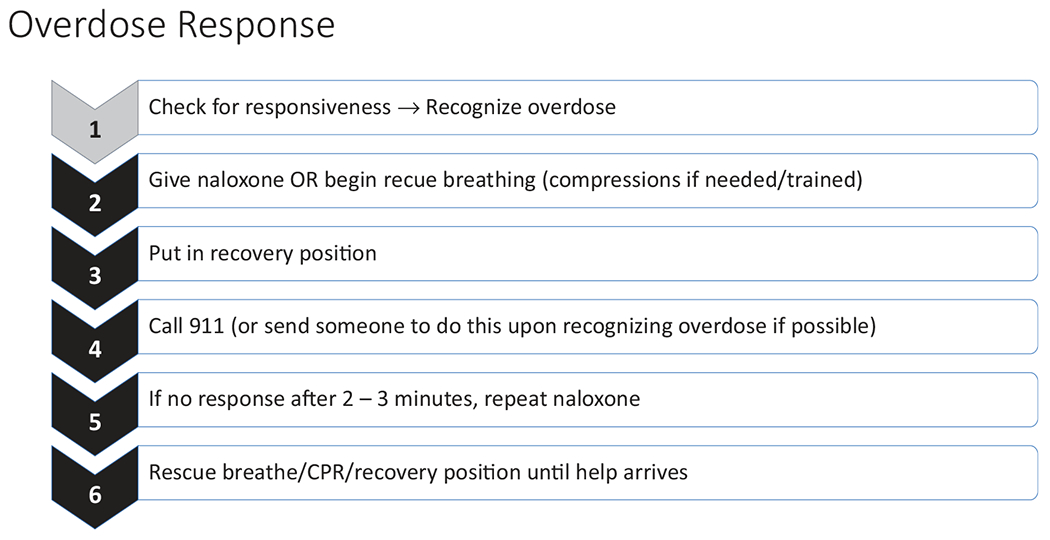

Following these introductory concepts, the lecture covered procedures to follow when responding to an opioid overdose (Figure 2). The facilitator first asked, “What is naloxone?” to gauge baseline knowledge and stimulate discussion, then described naloxone pharmacology including onset and duration of action, followed by instructions for how to use each of the four marketed naloxone formulations. Students had the opportunity to practice with demonstration devices of the Nasal Narcan™ product while the instructor facilitated a Question & Answer period. Students then discussed potential next steps after an overdose and concerns that patients may have about receiving treatment after revival from an opioid overdose.

Figure 2.

Procedure to follow when responding to an opioid overdose. The facilitator emphasized Steps 2–4 could be followed in any order depending on the number of people and materials available at the time of overdose.

During the final portion of the lecture, the facilitator asked students what they had heard about naloxone use, harm reduction, and SUDs and focused on “myth-busting” common concerns appearing in lay literature and media. Myths included potential ways to revive someone who has overdosed (e.g., cold shower, administering stimulant drugs), violence after reviving someone with naloxone, and potential harms of naloxone if used on someone not physiologically dependent on opioids. The lecture closed by briefly reviewing Good Samaritan laws around responding to opioid overdose in the State of Michigan and providing resources for how and where students could procure naloxone should they want to carry it.

Although much of this content resembles that provided in community-based trainings,22 the goal was to delve more deeply into these topics to engage with various aspects of the undergraduate medical curriculum. For example, when reviewing risk factors for opioid overdose, the facilitator discussed each risk in detail and elaborated on physiological and pharmacological factors leading to this increased risk. The fact that stimulants combined with opioids can increase risk of opioid overdose illustrates a counter-intuitive risk factor; in this example, students learn not just the risk but also how stimulants affect the cardiovascular system and how this interacts with opioid agonist effects to increase overdose risk. Unlike typical community trainings, students were taught more than just how to revive someone who has overdosed on opioids. For example, they were provided insight into medical, psychological, and social risk factors for overdose and how they, as future medical providers, could reduce these risks for their patients. We believe this multi-faceted approach helps to increase engagement and retention of content among medical trainees.

Assessments

We evaluated the training’s impact through voluntary surveys before and immediately afterward. Each survey included items about student perceptions of training and validated measures of knowledge and attitudes. We used the Opioid Overdose Knowledge Scale (OOKS) to evaluate knowledge of overdose risks and naloxone use.23 The OOKS has 4 domains: opioid overdose risk factors, signs of opioid overdose, actions to be taken in an opioid overdose, and naloxone use. We made one modification to this scale to include intranasal as a method of naloxone administration, resulting in a total possible score of 46 (rather than the original 45). We used the Opioid Overdose Attitudes Scale (OOAS) which has 3 domains that evaluate competencies to manage an opioid overdose, concerns about managing an opioid overdose, and readiness to intervene in an opioid overdose.23 Finally, we included the Medical Condition Regard Scale Modified for SUDs (MCRS), which was developed to identify attitudes toward patients with SUDs and has been used in medical education settings.10 The MCRS includes 11 statements with which participants must indicate their agreement using a 6-point Likert scale.

Replication phase

Approach

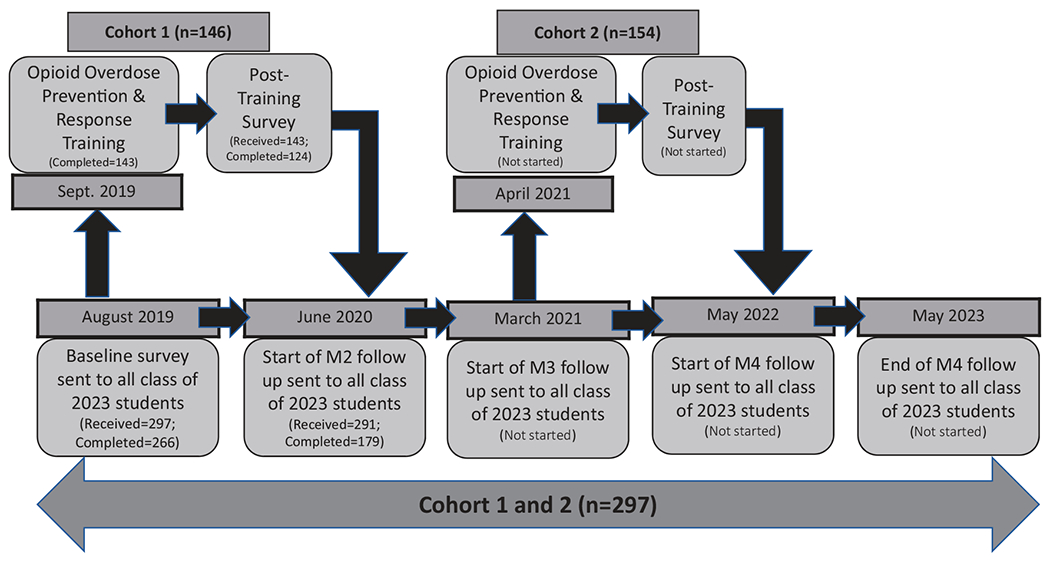

In the pilot stage, students’ self-selection to attend OOPR training and motivation to learn about these issues could have biased their responses. Therefore, in the next stage, this curriculum was introduced as a required session for 49.2% of the new first-year medical student class (randomly selected). This training was part of a larger project to examine the optimal timing of OOPR training during UME; therefore, the class was divided randomly with the goal of providing approximately half of the class with training at the start of their first year. The other half of the class will receive the same training at the start of their third year, immediately after completing the pre-clinical curriculum. Students were divided based on their assigned “learning communities”. First-year medical students are randomly assigned to one of eight learning communities to facilitate collaboration and mentorship across all four years of training. Students are assigned to these learning communities via an online confidential group sorting resource used by staff from the Office of Student Affairs to create balanced teams based on multiple criteria which include gender, in or out of state status, and college major. For this study, we used a random number generator to select four of those eight communities to become Cohort 1, the other four became Cohort 2. Training was provided as early as possible (September 24, 2019) before students had significant class time or clinical experience. We evaluated baseline knowledge, attitudes, experiences of all students in this class24 and used these results, along with findings from the pilot study, to refine the OOPR training curriculum. Figure 3 shows the overview of the study and how many students were invited versus how many actually completed each stage.

Figure 3.

Overview of replication study design methods. Completion of the baseline survey was required for all students. Students were randomly divided into 2 cohorts and cohort 1 was required to attend OOPRT during Sept. 2018. Cohort 2 will be required to attend training during April 2021. Due to expected “no-shows” at training and non-completion of surveys at each time point, the number of students included in the data analysis differs from the number invited to take part, and we indicate these differences below.

Overarching goals of delivering this lecture were identical to the pilot study. Additionally, we focused more on myths and questions about risks associated with naloxone use and distribution and discussed potential moral hazard concerns related to harm reduction efforts. Furthermore, we wanted to ensure students could understand the impact of laws surrounding naloxone access and harm reduction on themselves and their patients. We continued to address common myths surrounding overdose, opioids, harm reduction, and SUDs during these sessions.

Lecture structure

The lecture was structured similarly to the pilot study. We assigned 146 students to complete training, of whom 143 attended. To recreate the smaller group discussion setting of the pilot study, students were divided into 4 groups of ≈35 students each to receive training at one of four times on the assigned day. Students were given the same handout and the facilitator led students in discussion similar to the pilot study. Students were divided into groups of 4–6 to practice with Nasal Narcan™ demonstration devices; the facilitator visited each group to answer questions to provide an opportunity for students who might be reluctant to ask questions publicly. Once the class regrouped, the facilitator addressed those questions again to the whole audience to ensure everyone received the same level of content.

During the final portion of the lecture, the facilitator again asked students what they had heard about naloxone use, opioids, harm reduction, and SUDs and focused on “myth-busting”. Myths brought into the training curriculum by student participants were addressed and discussion focused on the potential moral hazard of naloxone distribution, concerns of naloxone immunity after multiple doses, and dangers associated with providing care to someone who has overdosed (e.g., fentanyl inhalation or violence). The lecture closed by reviewing Good Samaritan laws around OOPR in the State of Michigan and discussing concerns some people may have when considering whether to call 911 during an overdose. Students discussed how they might be able to help patients overcome those concerns and what they could do for patients who had recently overdosed.

Assessments

We evaluated the session’s impact by comparing results from baseline and post-training surveys. Surveys included the same items as the pilot about student perceptions of training and the OOKS, OOAS, and MCRS. We added the Naloxone Related Risk Compensation Beliefs (NaRRC-B) to explore views of naloxone use and distribution. The NaRRC-B is a 5-item assessment that asks respondents to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale their agreement with statements about effects of naloxone access and distribution on opioid use.25

Data analysis

Data analyses methods were consistent across both datasets. Raw data were screened for statistical outliers and normality prior to outcome analyses. Descriptive data are presented as mean ± one standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise specified. Paired t-tests (SPSS v.26) were used to evaluate changes in OOKS and OOAS domains and MCRS and NaRRC-B statements after completing training. Cohen’s D was calculated to evaluate the size of any significant effect to establish whether the outcome change might have any meaningful practical impact. Effect sizes between 0.2 and 0.5 are considered small, those between 0.5 and 0.8 are considered medium, and >0.8 large. Both evaluations were approved as exempt protocols by the WSU Institutional Review Board.

Results

Pilot phase

Of the 85 students invited to attend the initial training, 78 attended the lecture and 66 completed pre- and post-training surveys (see Figure 1 for breakdown). Students were distributed across medical school years (22.7% M1s, 15.2% M2s, 13.6% M3s, and 48.5% M4s). See Table 1 for detailed student demographics and relevant clinical experiences.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical experience characteristics at baseline of the pilot and replication study groups (mean ± SD).

| Pilot study (n = 66) |

Replication study (n = 124) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 26.2 ± 2.6 | 23.3 ± 2.2 |

| First year medical student (M1) | 15 (22.7%) | 124 (100.0%) |

| Gender (female) | 34 (51.5%) | 62 (50.0%) |

| Race (white) | 50 (75.8%) | 77 (62.1%) |

| Spanish, Hispanic, or Latino? | 0 (0.0%) | 14 (11.3%) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Worked in healthcare prior to medical school | 29 (43.9%) | 76 (61.3%) |

| Seen a patient with OUD in clinics or while volunteering (yes or maybe) | 51 (42.9%) | 45 (59.2%) |

| Previously attended a naloxone training | 2 (3.0%) | 11 (7.9%) |

| Experience with SUDs | ||

| Know someone with a SUD | 44 (66.7%) | 60 (48.4%) |

| Seen someone overdose | 24 (36.4%) | 15 (12.1%) |

| Know someone who overdosed | 25 (37.9%) | 33 (26.6%) |

| Desire to receive OOPRT | 63 (95.5%) | 117 (94.4%) |

At baseline 95.5% of students indicated they were interested in receiving OOPR training. In the post-training survey, 100% reported enjoying training and 100% reported believing future medical school classes should receive the same training. Students could write additional comments; although only 10 students did so, all responses were positive and indicated enjoyment of training and desire for additional similar trainings throughout their education.

Table 2 presents results for changes in OOKS and OOAS scores. Students demonstrated a significant increase in 3 of 4 OOKS domains and all 3 OOAS domains. We only found significant changes in 3 of 11 MCRS statements (Patients with Substance Use Disorders are particularly difficult for me to work with; I can usually find something that helps patients with Substance Use Disorders feel better; There is little I can do to help patients with Substance Use Disorders); on all three items we found improved attitudes toward patients with SUDs post-training.

Table 2.

Effects of opioid overdose prevention and response training on mean ± 1 SD Opioid Overdose Knowledge Scale (OOKS) and Opioid Overdose Attitude Scale (OOAS) scores in initial pilot study group (N = 66).

| Pre-training | Post-training | Test statistic (t) | p-Value | Cohen’s D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OOKS | |||||

| Risks | 8.02 ± 1.68 | 8.15 ± 1.30 | 0.80 | 0.425 | 0.09 |

| Signs | 7.77 ± 1.62 | 9.27 ± 0.94 | 7.61 | <0.001 | 1.13 |

| Actions | 9.67 ± 0.79 | 10.59 ± 1.02 | 8.35 | <0.001 | 1.01 |

| Naloxone | 11.98 ± 2.28 | 13.59 ± 1.55 | 5.47 | <0.001 | 0.83 |

| Total | 37.44 ± 4.68 | 41.61 ± 3.41 | 8.94 | <0.001 | 1.02 |

| OOAS | |||||

| Competencies | 3.07 ± 0.62 | 4.14 ± 0.43 | 15.88 | <0.001 | 2.01 |

| Concerns | 3.81 ± 0.45 | 4.04 ± 0.49 | 3.87 | <0.001 | 0.49 |

| Readiness | 4.25 ± 0.49 | 4.40 ± 0.41 | 3.65 | 0.001 | 0.33 |

| Total | 3.70 ± 0.38 | 4.20 ± 0.34 | 15.15 | <0.001 | 1.38 |

Bold values indicate all significant pre- to post-training differences where p < .05.

Replication phase

Of the 143 students who completed training, 124 (86.7%) completed pre- and post-training surveys (see Figure 3 for breakdown). See Table 1 for detailed student demographics and relevant clinical experiences. Table 3 shows results for the OOKS, OOAS, and NaRRC-B. Using paired t-tests, we found significant pre- to post-training increases in knowledge in 3 of 4 OOKS domains and 2 of 3 OOAS domains. There was no significant change in readiness to intervene in an opioid overdose; however, this score was already relatively high at baseline. Training significantly impacted all 5 NaRRC-B statements, indicating increased positive attitudes toward use and distribution of naloxone to people at risk for opioid overdose. Like the pilot study, the MCRS showed post-training improvements only in the same 3 statements (Patients with Substance Use Disorders are particularly difficult for me to work with, I can usually find something that helps patients with Substance Use Disorders feel better, There is little I can do to help patients with Substance Use Disorders), with no other significant changes.

Table 3.

Effects of opioid overdose prevention and response training on mean ± 1 SD Opioid Overdose Knowledge Scale (OOKS), Opioid Overdose Attitude Scale (OOAS), and Naloxone Related Risk Compensation Beliefs (NaRRC-B) scores in the Class of 2023 cohort (N = 124).

| Pre-training | Post-training | Test statistic (t) | p-Value | Cohen’s D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OOKS | |||||

| Risks | 7.90 ± 1.64 | 8.19 ± 1.10 | 1.92 | 0.057 | 1.38 |

| Signs | 6.15 ± 1.71 | 8.67 ± 0.95 | 15.97 | <0.001 | 1.82 |

| Actions | 9.52 ± 0.85 | 10.79 ± 0.57 | 13.98 | <0.001 | 1.76 |

| Naloxone | 9.61 ± 2.72 | 13.83 ± 1.13 | 16.53 | <0.001 | 2.03 |

| TOTAL | 33.17 ± 4.21 | 41.48 ± 2.22 | 23.26 | <0.001 | 2.47 |

| OOAS | |||||

| Competencies | 2.60 ± 0.66 | 4.05 ± 0.42 | 23.28 | <0.001 | 2.62 |

| Concerns | 3.50 ± 0.49 | 3.94 ± 0.44 | 9.87 | <0.001 | 0.95 |

| Readiness | 4.27 ± 0.43 | 4.34 ± 0.39 | 1.79 | 0.076 | 0.17 |

| Total | 3.46 ± 0.40 | 4.11 ± 0.35 | 17.39 | <0.001 | 0.93 |

| NaRRC-B | |||||

| 1 | 2.68 ± 0.92 | 2.03 ± 0.92 | 7.14 | <0.001 | 0.71 |

| 2 | 2.91 ± 0.95 | 2.36 ± 1.03 | 6.38 | <0.001 | 0.56 |

| 3 | 2.01 ± 0.83 | 1.69 ± 0.67 | 3.76 | <0.001 | 0.42 |

| 4 | 2.10 ± 1.02 | 1.76 ± 0.80 | 3.92 | <0.001 | 0.37 |

| 5 | 2.35 ± 0.91 | 1.97 ± 0.84 | 4.65 | <0.001 | 0.43 |

Bold values indicate all significant pre- to post-training differences where p < .05.

At baseline, 94.4% of students were interested in receiving OOPRT and 8.9% stated they had already attended a naloxone training session. After training, 95.2% of students stated they enjoyed OOPRT and 98.4% believed future classes should receive training. Only 14 students commented in the open-ended question requesting feedback about training. There were 8 comments (57.1%) that were completely positive without any negative comments or criticisms, praising training and affirming it would be efficacious for all students. Approximately one-quarter (21.4%) of comments addressed naloxone and a desire to be provided with naloxone during training. Two negative comments expressed displeasure in the timing of training (during an exam week); however, even these comments suggested training should still be provided, just at an alternative time.

Discussion

Pilot phase evaluation

Response to training was overwhelmingly positive. All students who received training enjoyed the experience and believed all medical students should receive the training. Results indicate training significantly improved knowledge about opioid overdose and attitudes toward responding to opioid overdoses; however, there was minimal improvement in general attitudes toward patients with SUDs. There could be two reasons for this finding: either training did not affect these attitudes or students already had positive attitudes that limited improvement (i.e., ceiling effect). Many students noted the discussion-based training format was an effective and engaging environment for learning and asking questions. This was likely strengthened by the relatively small class size and classroom (rather than lecture hall) setting. Students’ questions ranged from pharmacokinetics of opioids and naloxone to social impacts of SUDs. Expertise of the facilitator, a pharmacist with SUD specialty training and knowledge, was vital in the success of training. We believe that, although this training is generalizable to any medical education setting, the session facilitator must have experience and be trained in this subject matter.

Post-training surveys and general student feedback indicated that students were interested in training but sought more information on certain topics. Students were still uncomfortable about naloxone use and concerned about potential unintended consequences of naloxone distribution and other harm reduction efforts. Furthermore, they were uncertain about laws surrounding naloxone access and use and how these laws would affect physicians or patients.

A limitation of this pilot study is the self-selecting nature of the group. Over half of students attending training had explicitly sought out training and were eager to work with patients at risk of overdose. This bias could improve attention to lecture content and yield more positive attitudes toward this patient population. A second limitation involves including students from all years; previous educational and clinical experiences may impact response to training; by including a small sample from each year we cannot identify whether these factors played a role. This limitation underlies another question regarding optimal timing of this training to produce the greatest benefit to students, a question that we hope to answer with our larger, longitudinal study. Finally, this pilot study’s small sample size reduces statistical power. We aimed to address many of these limitations in the larger programmatic study.

Replication phase evaluation

One goal of the larger, longitudinal study was to replicate and validate findings from the pilot study that showed this intervention led to increased knowledge and attitudes regarding opioid overdose and was generally enjoyed and appreciated by students. The results of this larger training appear to replicate and validate the pilot study findings. Despite including a random sample of first-year medical students (rather than the self-selecting group considered in the pilot study), some of whom were not initially interested in receiving training, again we identified significant post-training improvements in knowledge and attitudes toward opioid overdose. Unfortunately, despite changes in the training curriculum geared to increase empathy and understanding toward patients with SUDs, we still did not identify a major impact of training on attitudes toward patients with SUDs. The addition of focused naloxone content and naloxone attitude-specific questions led to significant improvements in understanding the role of naloxone and harm reduction in helping patients at risk of opioid overdose. Furthermore, despite this sample not being a self-selected group with interest in receiving training, almost all enjoyed training and believed other students should receive it. Students who stated they did not enjoy training were primarily upset about its scheduling because it was only provided during an exam week.

Although almost all students enjoyed the discussion-driven format, a few reported concerns that questions asked about opioid overdose and pathophysiology were too high-level for students early in their training. Some students expressed anxiety about whether they were supposed to have known this information and were concerned about being embarrassed in front of their peers. In the future, at the start of training we recommend explaining to students they are not expected to know all these answers. The discussion format plays an important role in student engagement with training, enabling the facilitator to identify misinformation that she can gently clarify and correct. Importantly, the facilitator never called on a student who had not raised his/her hand, which should allow students concerned about embarrassment to feel more comfortable. We believe the discussion format is integral to training, thus, in the future it will be important to clarify at the start of training that students will only be called upon if they raise their hand.

Curriculum development

The goal of this training was not to meet all needs regarding SUD and opioid education but rather to take initial steps to address educational deficiencies and identify low-barrier interventions to meet student educational needs. This OOPR training curriculum offers a model for enhancing a specific aspect of SUD and harm reduction training for undergraduate medical students, without being resource- or time-intensive. Findings from the pilot and replication studies demonstrate robust improvements in knowledge and attitudes toward opioid overdose response after this one-hour training.

Our experiences identify central features to include in training medical students on those topics. Table 4 identifies key competency areas and objectives for all students after receiving training. In summary, students should not only be able to identify and respond to an opioid overdose, but also understand risk factors for overdose and recommend harm reduction methods to reduce risk, know optimal next steps to help a patient who has overdosed, recognize misbeliefs and stigma that impact patients, and appreciate relevant legal decisions that affect them and their patients. Presently, many medical school curricula lack this content. While this brief training cannot provide in-depth analysis of all these issues, it affords essential knowledge and insight that students can use with their patients and to educate their peers. Medical students volunteer and rotate in clinical settings from their first year of training and spend considerable time with patients. As such, they provide a crucial touchpoint for people at risk of opioid overdose and with SUDs, so it is imperative that students acquire knowledge and tools to help these patients as early as possible in their career.

Table 4.

Major competencies targeted by the finalized Opioid Overdose Prevention and Response curriculum.

| Competency Based Goal | By the end of the training the learner should be able to: |

|---|---|

| Opioid Overdose Identification | Identify physical signs of an opioid overdose and know how to distinguish between a person who is intoxicated vs. someone who is actively overdosing |

| Opioid Overdose Risk Factors | Recognize the risk factors associated with opioid overdose and identify any potential opportunities to intervene or reduce risk (e.g., not using alone) |

| Opioid Overdose Response | Respond in the event of an opioid overdose, help the patient in a variety of situations, and follow a standard response protocol after a patient has been revived with naloxone |

| Naloxone Use Methods | Use all available types of naloxone formulations and recall the mechanism and duration of action of naloxone as well as any potential side effects |

| Harm Reduction | Discuss the role of harm reduction in medicine and recognize that harm reduction efforts do not increase substance use |

| Naloxone Access Laws | Recall local and federal laws surrounding naloxone access and distribution both for physicians and patients |

| Good Samaritan Laws | Recall the role of Good Samaritan Laws in responding to overdose for physicians, bystanders, and people who use drugs and acknowledge that these laws differ by state |

| Myth Busting | Identify common myths surrounding SUDs and opioid overdose and provide factual corrections to this misinformation |

| Stigma | Recognize stigma in healthcare and identify common biases toward people who use drugs |

Within OOPR training, certain concepts will not change (e.g., opioid overdose pathophysiology); however, many topics need to be updated regularly. Thus, competency goals listed in Table 4 do not specify exactly what content needs to be taught to meet these standards. For example, a decade ago myths surrounding the ability of small amounts of fentanyl to be absorbed in the skin and cause overdose had not even begun, whereas this is now a pertinent piece of misinformation to address. One potential perceived weakness of this training is that it requires a skilled facilitator. It will not be satisfactory for a facilitator with minimal knowledge of the topic to lead a presentation. The facilitator must have contemporary knowledge of these issues to lead discussion. In non-healthcare settings, this may be a significant hurdle; however, we believe that in medical school settings it should not be difficult to find a clinician with relevant expertise. Our future studies will explore how in-person format differs from remote instruction. If remote format produces similar outcomes, it would expand possibilities for instruction in settings without a clinician trained in this topic.

One gap in training outcomes involves attitudes toward patients with SUDs and a broader understanding of risks for these patients. Findings from our prior analysis24 indicate that our medical students enter with some stigmatizing views toward patients with SUDs, suggesting that lack of significant change is not due to a ceiling effect wherein students already have the least-biased view of patients with SUDs. Further work is needed to evaluate how to improve these attitudes. Some students stated that they would like to see patients with lived experience of SUDs and those who had overdosed on opioids and been revived by naloxone. Including a patient panel of this type in addition to OOPR training might improve attitudes toward patients; however, institutions must be careful to implement these sessions in ways that do not further stigmatize or take advantage of these vulnerable groups. Importantly, a brief training will not remove deeply-entrenched structural stigma toward people with SUDs within medicine; however, creating change in attitudes of the next generation of physicians is a key step forward.

Although following the 6-step method for curricular development and using a pilot and replication study approach helped minimize limitations related to these findings, other limitations remain. First, these data were gathered at one medical school in the USA so our findings may not represent the curricular impact on all medical students; however, response rate was high, the medical school class is large and diverse, and WSUSOM student demographics are comparable to national averages reported by the AAMC.26 Second, all data were self-reported and could be biased toward social desirability. Although this limitation cannot be removed using these survey tools, we believe these anonymous surveys mitigate this bias. Third, the discussion-based lecture format promotes student engagement, but results in training that cannot be identically replicated. The facilitator made significant efforts to ensure trainings contained the same content, following the content outline described here; nonetheless, no two trainings can be identical as students ask different questions each time.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this curricular development project identified a way to significantly improve medical student knowledge and understanding surrounding opioid overdose and harm reduction through a one-hour training. We believe this brief curriculum can be easily integrated into any medical school schedule and will increase students’ preparedness in this subset of SUD-related competencies. A next step is to evaluate long-term impact of this curriculum. It is vital to identify whether these changes are maintained over time or whether students need regular education on this topic to ensure improvements are not lost. Furthermore, although changes in these validated assessments point to efficacy of the curriculum, it will be essential to examine whether integration of this curriculum produces real-world behavioral changes such as improved communication with at-risk patients, advocacy for patients in clinical settings, initiation of discussion about naloxone with their clinical team, and increased engagement in the community (e.g., increased rates of volunteering in free clinics). It is also critical to consider what additional relevant trainings and curricular interventions will be necessary to ensure medical students meet all key competencies for this topic. Finally, it will be important to explore whether there is an ideal time during training or method to provide this training. There is a clear need and desire for increased education in this area. This brief training curriculum fills a critical gap in current UME and provides a strong foundation for developing more significant curricular changes focused on pain, substance use, and harm reduction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staff and students at Wayne State University School of Medicine for supporting the development and distribution of this survey.

Disclosure statement

Faculty effort was supported by the Gertrude Levin Endowed Chair in Addiction and Pain Biology (MKG), Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (Helene Lycaki/Joe Young, Sr. Funds), and Detroit Wayne Integrated Health Network.

Footnotes

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2021.1941515.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval has been waived for this study. For the pilot study the investigators received IRB exemption status (IRB#: 041919B3X, Protocol#: 1904002169) 04/0/2019. For the replication study, the investigators received IRB exemption status (IRB#: 082419B3X, Protocol#: 1908002442) 08/08/2019.

Data availability statement

Raw data were generated at Wayne State University School of Medicine. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author MKG on request.

References

- [1].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Opioid overdose: data analysis and resources. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/analysis.html. Published 2020. Accessed June 24, 2020.

- [2].Jack HE, Warren KE, Sundaram S, et al. Making naloxone rescue part of basic life support training for medical students. Santen S, ed. AEM Educ Train. 2018;2(2):174–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cox BM, Cote TE, Lucki I. Addressing the opioid crisis: medical student instruction in opioid drug pharmacology, pain management, and substance use disorders. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019;371(2):500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zerbo E, Traba C, Matthew P, et al. DATA 2000 waiver training for medical students: lessons learned from a medical school experience. Subst Abus. 2020;41(4):463–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thomas J, Slat S, Woods G, Cross K, Macleod C, Lagisetty P. Assessing medical student interest in training about medications for opioid use disorder: a pilot intervention. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520923994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Stokes DC, Perrone J. Increasing short- and long-term buprenorphine treatment capacity: providing waiver training for medical student. Acad Med Epub. 2021. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003968. Online ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lien IC, Seaton R, Szpytman A, et al. Eight-hour medication-assisted treatment waiver training for opioid use disorder: integration into medical school curriculum. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1847755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tookes H, Bartholomew TS, St. Onge JE, Ford H. The University of Miami Infectious Disease Elimination Act (IDEA) Syringe Services Program. Acad Med. 2021;96(2):213–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Oldfield BJ, Tetrault JM, Wilkins KM, Edelman EJ, Capurso NA. Opioid overdose prevention education for medical students: adopting harm reduction into mandatory clerkship curricula. Subst Abus. 2020;41(1):29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Berland N, Fox A, Tofighi B, Hanley K. Opioid overdose prevention training with naloxone, an adjunct to basic life support training for first-year medical students. Subst Abus. 2017;38(2):123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Waskel EN, Antonio SC, Irio G, Campbell JL, Kramer J. The impact of medical school education on the opioid overdose crisis with concurrent training in naloxone administration and MAT. J Addict Dis. 2020;38(3):380–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Freise JE, McCarthy EE, Guy M, Steiger S, Sheu L. Increasing naloxone co-prescription for patients on chronic opioids: a student-led initiative. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):797–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Core competencies for entering medical students. https://www.aamc.org/services/admissions-lifecycle/competencies-entering-medical-students. Accessed February 20, 2021.

- [14].Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Required premedical coursework and competencies. Medical school admission requirements. https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-medical-school/article/required-premedical-course-work-and-competencies/. Published 2020. Accessed February 20, 2021.

- [15].Liason Committee on Medical Education (LCME). Functions and structure of a medical school: standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the MD Degree. https://lcme.org/publications/#Standards. Published 2019.

- [16].Antman KH, Berman HA, Flotte TR, Flier J, Dimitri DM, Bharel M. Developing core competencies for the prevention and management of prescription drug misuse: a medical education collaboration in Massachusetts. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1348–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Berland N, Lugassy D, Fox A, et al. Use of online opioid overdose prevention training for first-year medical students: a comparative analysis of online versus in-person training. Subst Abus. 2019;0(0):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hargraves D, White CC, Mauger MR, et al. Evaluation of an interprofessional naloxone didactic and skills session with medical residents and physician assistant learners. Pharm Pract. 2019;17(3):1591–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kwon M, Moody AE, Thigpen J, Gauld A. Implementation of an opioid overdose and naloxone distribution training in a pharmacist laboratory course. AJPE. 2020;84(2):7179–7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Chen BY. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. Johns Hopkins University Press. https://jhu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/curriculum-development-for-medical-education-a-six-step-approach. Published 2015. Accessed September 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Moses TE, Chou JS, Moreno JL, Lundahl LH, Waineo E, Greenwald MK. Long-Term effects of opioid overdose prevention and response training on medical student knowledge and attitudes toward opioid overdose: a pilot study. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [22].Clark AK, Wilder CM, Winstanley EL. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. J Addict Med. 2014;8(3):153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Williams AV, Strang J, Marsden J. Development of Opioid Overdose Knowledge (OOKS) and Attitudes (OOAS) Scales for take-home naloxone training evaluation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(1-2):383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Moses TE, Chammaa M, Ramos R, Waineo E, Greenwald MK. Incoming medical students’ knowledge of and attitudes toward people with substance use disorders: implications for curricular training. Subst Abus. 2020;0(0):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Winograd RP, Werner KB, Green L, Phillips S, Armbruster J, Paul R. Concerns that an opioid antidote could “make things worse”: profiles of risk compensation beliefs using the Naloxone-Related Risk Compensation Beliefs (NaRRC-B) Scale. Subst Abus. 2020;41(2):245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Association of American Medical Colleges. Matriculating Student Questionnaire. www.aamc.org/data/msq. Published 2019. Accessed September 18, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data were generated at Wayne State University School of Medicine. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author MKG on request.