Abstract

Background:

Although medications to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD) are the standard of care during pregnancy, there are many potential gaps in the cascade of care for pregnant people experiencing incarceration.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of pregnant people with opioid use disorder incarcerated in a Southeastern women’s prison from 2016–2019. The primary outcomes were access to MOUD during incarceration and continuity in the community. We used descriptive statistics to summarize aspects of our sample and logistic regression to identify predictors of MOUD receipt during incarceration.

Results:

Of the 279 pregnant people with OUD included in the analysis, only 40.1% (n=112) received MOUD during incarceration, including 67 (59.8%) who received methadone and 45 (40.1%) who received buprenorphine. Less than one-third of the participants were referred to a community MOUD provider (n=83, 30%) on return to the community. Significant predictors of MOUD receipt included medium/close custody level during incarceration, incarceration during the latter portion of the study period, pre-incarceration heroin use, and receipt of pre-incarceration MOUD.

Conclusions:

Although prisons can serve as an important site of retention in MOUD for some pregnant people, there were substantial gaps in initiation of MOUD and retention in MOUD among pregnant people with OUD imprisoned in the Southeast during the study period.

Opioid Use Disorder, Treatment, and Pregnancy

Opioid use disorder (OUD) continues to be a significant and increasing problem among reproductive age people and those who are pregnant.11–3 People who experience OUD during pregnancy face complicating factors including trauma, social stigma, discrimination and the changes in physiology during pregnancy. For pregnant people with OUD, stigma and discrimination from the legal system, their own families, and society at large, are thought to contribute to the high risk for overdose and death both during pregnancy and the postpartum period.4–6

Treatment with MOUD in pregnancy reduces fetal exposure to non-prescribed opioid use, improves adherence to prenatal care, and improves neonatal birth weights, generally outweighing the risk of medication-induced neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS).5,7,8 This risk and benefit calculation may be particularly true for people in facilities without the comprehensive medical and psychosocial supports needed for supervised, medication-assisted withdrawal.9 Medically supervised withdrawal or discontinuation of MOUD during pregnancy or the postpartum period in carefully chosen contexts with high levels of medical and social support is possible, but has also been associated with mixed safety data, higher rates of return to substance use compared with MOUD, ultimately leading to increased non-prescribed fetal opioid exposure, and increased risk of overdose.10

In the immediate postpartum period, guidelines recommend maintenance of MOUD at the pregnancy dose. Adequate pain control for postpartum people who received MOUD during pregnancy generally includes individually tailored doses of both non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications and opioid medications.11 Expert opinion regarding the duration of MOUD therapy suggest that MOUD only be stopped after the person is ready to live without the medication. Clinical recommendations for people who received MOUD during pregnancy include continuation of MOUD at least until the person endorses readiness to discontinue, lives in a drug-free home, the infant sleeps through the night, breastfeeding is completed, and there are multiple indicators of stability in the person’s life.9 Continuation of long-term MOUD after pregnancy may mitigate the heightened risk of death that persists for at least a decade for postpartum people with OUD.12

Prisons, Pregnancy, and OUD Treatment.

Women with substance use disorders are an increasingly prevalent demographic in US prisons and jails.13–16 Jails generally house people between arrest and trial or for sentences less than a year. People incarcerated in prisons have usually been sentenced to a year or more. Approximately 4–6% of women are pregnant at the time of arrest, and the population experiencing the intersection of pregnancy, OUD, and incarceration has also increased in recent years.17,18 This increase is reflected in a corresponding increase in referrals from prisons and jails for treatment of OUD in pregnancy, and a national OUD prevalence of 26% in incarcerated people.19,20 The Southeastern US has disproportionately high numbers of women incarcerated for OUD-related charges, and the rate of OUD among pregnant women imprisoned in North Carolina is approximately 50%.21–24

People with OUD who abstain from opioid use during a period of incarceration are at 40 times greater risk of death from overdose during their first two weeks in the community, compared with someone who did not experience incarceration;25 women, and particularly postpartum women may be at particularly high risk of overdose death.4,26 Initiation of MOUD for women during incarceration improves engagement and retention in community-based treatment, increases abstinence after community re-entry, and decreases overdose deaths.27–29

Despite these demonstrated benefits, some prison and jail facilities do not offer MOUD, resulting in a forced withdrawal from opioids at the time of incarceration.20 MOUD may be provided only during pregnancy, with immediate postpartum discontinuation.20,23,30,31 This postpartum withdrawal from MOUD is largely due to an administrative preference for “drug-free” treatment and security concerns about increasing the availability of opioids inside the facility, although stigma and discrimination are also important drivers of decreased access to MOUD.30–32 In our prior work with a incarcerated pregnant sample, we demonstrated unmet need for MOUD during pregnancy, postpartum withdrawal from MOUD, and a 19% rate of referral for MOUD in the community after incarceration.23 This discontinuity of treatment is inconsistent with clinical recommendations,33 and thus, descriptions of the experience of postpartum withdrawal are largely absent from the literature.

Objectives.

Our primary objective was to measure access to and continuity of MOUD during pregnancy in a Southeastern prison from 2016–2019. Our secondary objective was to describe postpartum withdrawal and pain experiences for those who delivered during an episode of incarceration.

Methods

Setting.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of pregnant people with OUD at the North Carolina Correctional Institution for Women (NCCIW) from 2016–2019. NCCIW is the only state prison facility housing pregnant people and has a total capacity of 1,776.34 During the study period, a total of 12,470 women aged 18–45 entered NCCIW, an average of 3,118 per year. Of those, 28% carried sentences of 12 months or less, 41% were sentenced to 1–2 years, 17% were sentenced for 2–5 years, and 3% were sentenced to more than 5 years.35 Seven percent were people transferred to the prison from a county jail under the safekeeping policy, which provides for transfer to the prison pre-trial detention or jail incarceration for services unavailable in the jail.36 Safekeeping was used due to pregnancy for approximately 60 people each year.37 People transferred for safekeeping during pregnancy return to county jail custody postpartum. During the study period, the total daily pregnancy census ranged from 20–60 people.

The Institutional Review Board at our institution (#18–2027 and #19–3247) and the North Carolina Department of Public Safety (NCDPS) Human Subjects Research Committee (#1908–03 and #2005–01) reviewed and approved this project with waivers of informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization for this retrospective study.

Study participants.

Participants were eligible for this analysis if they were pregnant and incarcerated at NCCIW from 2016 to 2019, and were identified as having OUD. Potential participants were identified through prison prenatal clinic roster problem lists and OUD was confirmed through review of clinic records. All available weekly paper clinic rosters were reviewed. Rosters were only available for 14 weeks of 2016, 16 weeks of 2017, 44 weeks of 2018, and 49 weeks of 2019; records for the other weeks had been lost and neither digital nor paper copies could be located. Potential participants were excluded if their pregnancy and incarceration overlapped by only a very short time, including experiencing pregnancy loss and/or returning to the community within 24–72 hours. Data regarding duration of jail incarceration prior to arrival at the prison were not available. Those transferred for safekeeping were typically sent urgently due to acute withdrawal symptoms, while others had often spent more time in jail. Deliveries were identified during review of the NCDPS electronic medical record (EMR) and confirmed through review of the delivering hospital EMR.

Medication administration.

Intake procedures at NCCIW during pregnancy include assessment for non-prescribed substance use and withdrawal symptoms by nursing staff, facility primary care physicians and later by behavioral health clinicians. People who were not pregnant were not eligible for referral for MOUD. For pregnant people, oxycodone 30 mg three times daily was used to treat acute withdrawal until they could be referred for MOUD, withdrawn via gradual taper of the oxycodone dose over several weeks, or delivery of their pregnancy. Prior to midyear 2018, people without acute opioid withdrawal symptoms were not considered eligible for MOUD. Consensus among medical providers at NCCIW during this period was to recommend withdrawal from opioids during the first trimester and only to consider MOUD during the second and third trimester (personal communication, August, 2017). Women who were late in the third trimester at intake were sometimes prescribed oxycodone for management of withdrawal until delivery rather than being referred for MOUD; this practice was discontinued in mid-2018. MOUD was prescribed and administered at an off-site facility contracted with NCDPS; those referred to this facility were transported daily and directly observed receiving either methadone or buprenorphine treatment.

Measures.

The primary outcomes were abstracted from the patient profile, clinic notes, and scanned documents in the NCDPS EMR. Secondary maternal outcomes were abstracted from provider and nursing notes and medication administration records in the NCDPS EMR and flow sheets from the hospital EMR where delivery occurred. Substance use during pregnancy was abstracted from self-report via NCDPS EMR. Incarceration, sociodemographic, and obstetric variables were abstracted from the NCDPS EMR. All data were abstracted by trained research assistants (SZ, RS) and reviewed by a board-certified OB/GYN (AK). Data abstracted from the EMRs was entered into a secure REDCap database without any identifying information.

Access to and continuity of MOUD outcomes.

The two primary outcomes were measures of (1) access to and (2) continuity of MOUD. Access to MOUD during incarceration was operationalized as a binary variable defined as either MOUD (buprenorphine or methadone) or non-standard treatment (including either no treatment or oxycodone). Continuity of MOUD was measured as referral to a community MOUD provider at the time of community re-entry, coded as a binary variable (yes/no).

Postpartum outcomes.

These secondary outcomes included withdrawal experiences on return to NCCIW and postpartum pain scores prior to hospital discharge. Withdrawal was measured during the first week after hospital discharge. Symptom severity was measured using the number of withdrawal symptoms recorded in prison nursing and provider notes per day and binary variables indicating whether a participant had any withdrawal symptoms recorded per day. Withdrawal treatment was measured as the number of withdrawal medications (including ondansetron, clonidine, and oxycodone as part of a taper) taken per day and binary variables indicating whether any withdrawal medication was given each day. Hospital nurses measured postpartum pain scores using a subjective self-report scale (0–10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating the worst pain ever). Pain scores were abstracted from the record during up to four hospital days postpartum. We calculated the average and maximum pain scores per day from up to 10 pain scores abstracted from each day.

Explanatory variables.

Potential explanatory variables were based on the existing literature on MOUD receipt. Sociodemographic variables included race, age at the time of incarceration, and completion of high school (yes/no). Race was categorized according to NCDPS, and was dichotomized into White and non-White due to small subsample sizes to prevent deductive disclosure. A set of binary variables were created to assess pre-incarceration substance use, including alcohol, amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, heroin, inhalants, other non-prescribed opioids, sedatives, and tobacco. Abstraction of data from the prison EMR did not permit further categorization of the “other non-prescribed opioids.” Incarceration variables included participants’ prison-defined custody level (minimum, medium or close security), a binary variable indicating safekeeping status, a binary variable indicating delivery during their incarceration, the duration of incarceration during pregnancy (days), and the projected remaining days of incarceration after delivery. Obstetric variables included pregnancy trimester at the time of incarceration and whether delivery occurred during the episode of incarceration. Estimated delivery date (EDD), or “due date” for the pregnancy was used as a measure of calendar time.

Descriptive variables.

Additional descriptive variables were abstracted to thoroughly describe the sample and treatment characteristics but were not included in the inferential analyses. Additional descriptive obstetric data included the number of prior pregnancies, number of living children, pregnancy complications, and mode of delivery (vaginal birth or cesarean section). We assessed the type of medication (buprenorphine vs. methadone vs. oxycodone), initial dose (in milligrams), dosage at time of delivery or community re-entry (in milligrams).

Statistical Analyses.

Analyses were conducted with all non-missing data for that outcome using Stata and R statistical programs.38,39 We chose a Type I error rate of .05 for all tests of significance.

Descriptive statistics.

We calculated frequencies and percentages for all categorical variables. We described continuous variables with means and standard deviations.

Primary outcomes.

For receipt of MOUD, we estimated unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the predictor variables using logistic regression. Explanatory variables that were statistically significantly associated with receipt of MOUD were then retained in a multivariable logistic regression to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% CIs. For a referral for MOUD continuation in the community, we estimated an unadjusted OR and 95% CI using receipt of MOUD during incarceration as a predictor. Based on our prior work, we anticipated that only a small number of participants would be referred for MOUD continuation such that a multivariable regression would be underpowered.23

Secondary outcomes.

For postpartum withdrawal outcomes, analyses were conducted on the subsample who delivered during incarceration and had received MOUD. We calculated the average number of withdrawal symptoms experienced and medications received during the seven days after return to the prison. The binary outcome of any withdrawal was compared between the methadone and buprenorphine groups using logistic regression with medication group and time (in days) as covariates. The coefficients in the logistic regression were estimated using generalized estimation equations (GEE) with an exchangeable correlation matrix to account for the correlation between the participant’s seven days of measured outcomes. For postpartum pain, the analysis of pain scores was stratified by mode of delivery given well-established differences in pain following a vaginal birth and cesarean section.40 Within each mode of delivery, pain scores were compared across groups using one-way ANOVA.

Results

Study sample.

There were 359 pregnant individuals with OUD identified as potential participants based on their prenatal clinic problem lists. This represented an average of 58% of pregnant people imprisoned at NCCIW during the study period. Of this group, 5 were excluded because they returned to the community before any pregnancy-related information was entered into the medical record, 6 could not be matched with patients in the medical record, 7 were either not pregnant or had a first trimester pregnancy loss or termination shortly after arrival at the facility, and 62 women were excluded because a history of opioid use could not be confirmed in the record. The remaining 279 participants met criteria for OUD by having documented in the medical record 1) recent prior treatment with MOUD OR withdrawal or tolerance to opioids; and 2) persistent use of opioids despite health and social consequences. No potential participants had been prescribed opioids during pregnancy other than opioid agonist MOUD. There were 279 pregnant individuals with OUD included in the analysis. There were 124 pregnant people who delivered during incarceration, including 91 who had vaginal deliveries and 31 who had cesarean deliveries. Of these 124 participants, 49 had received MOUD during pregnancy.

Missing data.

Paper records were only available for 27% of weeks in 2016, 31% of 2017, 85% of 2018, and 94% of 2019. For the participants whose data was abstracted, there was no missing data on age, race, custody status, safekeeping status, pre-incarceration substance use or the MOUD variables. There were 2 (<1%) participants missing community MOUD referral data. There were 4 (1%) participants with missing data on education and 95 (34%) with missing data on the duration of incarceration. There were 7 (3%) for whom gestational age at the time of incarceration could not be determined, 8 (3%) with missing estimated date of delivery, 2 (<1%) missing the mode of delivery, 5 (2%) with missing data on the number of prior pregnancies and deliveries.

Participant Characteristics.

The mean age was 28.7 (SD=4.6) and most participants were White (n=258, 92.5%). The majority of pregnant participants were assigned to minimum custody level (n=155, 56%) while 122 (44%) were assigned to medium/close custody. The safekeeping policy resulted in a relatively large number of referral admissions to the prison (n=110; 39%). Specific opioid use prior to incarceration included heroin (n=63; 22.6%) and other opioids (n=247; 88.5%). Other reported substance use prior to incarceration included tobacco (n=208, 74.5%), alcohol (n=82, 29.4%), cannabis (n=92, 33%), and amphetamines (n=94, 33.7%). Less than one-third of participants (n=85, 30.5%) were receiving MOUD prior to incarceration, and of those who were, 55.3% (n=47) were receiving buprenorphine and 44.7% (n=38) were receiving methadone. At the time of incarceration, 23.2% (n=63) of participants were in their first trimester of pregnancy, 41.2% (n=112) in their second, and 35.7% (n=97) in their third. The mean number of total pregnancies including the current pregnancy was 3.8 (SD = 1.98) and mean total number of living children was 2.0 (SD = 1.67). The most frequently reported pregnancy complication was mental health issues (21.1%, n=59). There were 30 participants (10.7%) with a noted diagnosis of Hepatitis C. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, pregnancy, and substance use characteristics among pregnant people with opioid use disorder incarcerated in a Southeastern prison between 2016–2019 who received either opioid agonist medications for opioid use disorder or non-standard treatment (n=279)

| Overall (n = 279) | MOUD (n = 112, 40.1%) | Non-Standard Treatment (n = 167, 59.9%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age — Mean ( SD ) | 28.3 (4.6) | 28.8 (4.0) | 28.1 (5.1) |

| Race — N (%) | |||

| Non-White | 21 (8%) | 8 (7%) | 13 (8%) |

| White | 258 (92%) | 104 (93%) | 152 (92%) |

| Completed High School — N (%) | |||

| No | 96 (34%) | 39 (35%) | 57 (34%) |

| Yes | 183 (66%) | 73 (65%) | 110 (66%) |

| Custody Level — N (%) | |||

| Minimum | 155 (56%) | 49 (44%) | 106 (64%) |

| Medium/Close | 122 (44%) | 63 (56%) | 59 (36%) |

| Safekeeper — N (%) | |||

| No | 169 (61%) | 62 (55%) | 107 (64%) |

| Yes | 110 (39%) | 50 (45%) | 60 (36%) |

| Pregnancy Trimester at Intake — N (%) | |||

| First | 63 (23%) | 17 (15%) | 46 (29%) |

| Second | 112 (41%) | 53 (48%) | 59 (36%) |

| Third | 97 (36%) | 40 (36%) | 57 (35%) |

| Estimated Due Date — N (%) | |||

| 2015–2018 | 145 (54%) | 45 (40%) | 100 (63%) |

| 2019–2020 | 126 (46%) | 67 (60%) | 59 (37%) |

| Duration of Incarceration During Delivery Prior to Release — N (%) | 94.7 (61.0) | 100.3 (59.7) | 89.6 (62.1) |

| No | 154 (55%) | 63 (56%) | 91 (55%) |

| Yes | 125 (45%) | 49 (44%) | 76 (45%) |

| Pre-Incarceration Substance use — N (%) | |||

| Tobacco | 208 (75%) | 83 (74%) | 125 (75%) |

| Alcohol | 82 (29%) | 32 (29%) | 50 (30%) |

| Cannabis | 92 (33%) | 34 (30%) | 58 (35%) |

| Cocaine | 82 (29%) | 27 (24%) | 55 (33%) |

| Amphetamine | 94 (34%) | 40 (36%) | 54 (32%) |

| Heroin | 63 (23%) | 34 (30%) | 29 (17%) |

| Other Opioids | 247 (88%) | 97 (87%) | 150 (90%) |

| Pre-Incarceration MOUD | |||

| No | 194 (70%) | 49 (44%) | 145 (87%) |

| Yes | 85 (30%) | 63 (56%) | 22 (13%) |

| Pre-Incarceration MOUD Medication | |||

| Buprenorphine | 48 (56%) | 32 (50%) | 16 (73%) |

| Methadone | 38 (44%) | 32 (50%) | 6 (27%) |

Notes: Where data were missing for a variable (see text for details), the reported percentage is for the non-missing data. All pre-incarceration substance use is self-reported. MOUD = Medications for Opioid Use Disorder

Primary Outcome:

Of the 279 participants, 40% (n=112) received MOUD during their incarceration. Of these 112 participants, 67 (60%) received methadone and 45 (40.1%) received buprenorphine. Of the 167 participants (60%) who received non-standard treatment, 52 (31%) received oxycodone maintenance or taper. The average initial dose of methadone was 44.5 mg (SD=27.0; Range=5–135) and average initial buprenorphine dose was 10.2 mg (SD=6.4; Range=2–24). At time of delivery or discharge, the average methadone dose was 67.9 mg (SD=29.6; Range 0–135) and average buprenorphine dose was 18.3 mg (SD=11.5; Range=2–34 mg).

Unadjusted and adjusted ORs for receiving MOUD during incarceration are shown in Table 2. In the unadjusted models, participants assigned medium/close custody levels were significantly more likely to receive MOUD than participants at minimum custody level. Participants in the first trimester of pregnancy were no more or less likely to receive MOUD than participants in the third trimester, but were significantly less likely to receive MOUD than participants in the second trimester. Incarceration during the latter portion of the study period, as measured by the estimated due date of pregnancy in 2019–2020 was a predictor of receipt of MOUD. Participants with a pre-incarceration history of heroin use and a pre-incarceration history of MOUD treatment were significantly more like to receive MOUD than participants without such histories. None of the pre-incarceration non-opioid substance use variables were statistically significant predictors of receipt of MOUD in prison. All the statistically significant univariate predictors as noted in Table 3 were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. Medium/close custody level, estimated due date, pre-incarceration heroin use, and pre-incarceration MOUD remained significant predictors of MOUD receipt.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for receipt of medications for opioid use disorder during pregnancy in a Southeastern prison, 2016–2019 (n = 279).

| OR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03 | (0.98, 1.08) | ||

| White Race (Reference = Non-White) | 1.10 | (0.44, 2.74) | ||

| Completed High School (Reference = No) | 0.97 | (0.59, 1.60) | ||

| Medium/Close Custody Level (Reference = Minimum) | 2.31 | (1.41, 3.77) | 2.51 | (1.32, 4.77) |

| Safekeeper (Reference = No) | 1.44 | (0.88, 2.34) | ||

| Pregnancy Trimester at Intake (Reference = First) | ||||

| Second | 2.43 | (1.24, 4.74) | 1.58 | (0.71, 3.54) |

| Third | 1.90 | (0.95, 3.78) | 1.26 | (0.53, 2.97) |

| Estimated Due Date 2019–2020 (Reference = 2015–2018) | 2.52 | (1.54, 4.14) | 3.53 | (1.83, 6.83) |

| Duration of Incarceration During Pregnancy (Days) | 1.00 | (1.00, 1.01) | ||

| Delivery Prior to Release (Reference = No) | 0.93 | (0.58, 1.51) | ||

| Pre-Incarceration Substance Use | ||||

| Tobacco (Reference = No) | 0.96 | (0.55, 1.66) | ||

| Alcohol (Reference = No) | 0.94 | (0.55, 1.58) | ||

| Cannabis (Reference = No) | 0.82 | (0.49, 1.37) | ||

| Cocaine (Reference = No) | 0.65 | (0.38, 1.11) | ||

| Amphetamine (Reference = No) | 1.16 | (0.70, 1.92) | ||

| Heroin (Reference = No) | 2.07 | (1.17, 3.66) | 3.09 | (1.49, 6.42) |

| Other Opioid (Reference = No) | 0.73 | (0.35, 1.53) | ||

| Pre-Incarceration MOUD (Reference = No) | 8.47 | (4.73, 15.19) | 16.87 | (7.99, 35.62) |

| Pre-Incarceration MOUD Medication | ||||

| Buprenorphine | Reference | |||

| Methadone | 2.67 | (0.95, 7.68) |

Notes:. OR = Odds Ratio. CI = Confidence Interval. aOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio. MOUD = Medication for Opioid Use Disorder. Significant ORs and aORs are noted in bold. Unadjusted analyses include all non-missing data on each variable (see text for details). Multivariable logistic regression model used to estimate adjusted odds ratios include all explanatory variables that were significant in the unadjusted analyses and all participants with non-missing data for all variables in the model (n = 270).

Overall, less than one-third of the participants were referred to a community MOUD provider at release from prison (n=83, 30%). Of the 112 participants who received MOUD during incarceration, the majority (n=74; 66.1%) received a referral. Referrals were similar between participants receiving methadone and buprenorphine, with 60.9% (n = 42) and 74.4% (n = 32) respectively, receiving a community referral. Of those who received non-standard treatment (n=165), only 9 (5.4%) were referred to a community MOUD provider.

Secondary Outcomes.

Postpartum Withdrawal.

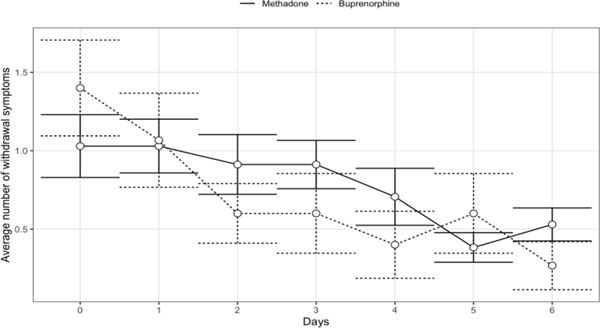

There were 49 participants who received MOUD during pregnancy and delivered during incarceration, including 34 (69%) who received methadone and 15 (31%) who received buprenorphine. The average number of symptoms documented each day is shown in Figure 1; since the average was approximately one symptom throughout the time period, we used the dichotomized outcome with any symptom in the model. The logistic regression analysis showed a significant linear time trend with a reduction in the odds of any withdrawal symptoms each day by 19% (95% CI: 8%, 28%). The odds of any withdrawal symptom for the buprenorphine group were 36% (95% CI: −34%, 69%) lower than the odds for the methadone group, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. Participants received an average of one medication for withdrawal each day, including opioid medications (oxycodone, Percocet), medications for nausea (ondansetron, promethazine), and other symptomatic therapy (clonidine, diphenhydramine, gabapentin).

Figure 1.

The mean number of withdrawal symptoms documented each day with 95% confidence intervals, by methadone or buprenorphine receipt during pregnancy, following hospital discharge to a Southeastern women’s prison after vaginal and cesarean deliveries, 2016–201

Postpartum Pain.

Table S1 reports a summary of our examination of post-partum pain scores. There were no significant differences in postpartum pain across medication groups following either vaginal delivery or cesarean section. There were no statistically significant differences in the amount of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or oxycodone on any postpartum or postoperative day between the groups (data not shown).

Discussion

The cascade of care for individuals with OUD begins with diagnosis and continues through engagement in care, initiation of MOUD, retention in MOUD for more than six months, and then ongoing management of OUD in remission.41 We found a significant gap in initiation of MOUD among pregnant people imprisoned in North Carolina between 2016 and 2019. It is important to note that receipt of MOUD was significantly more likely during the second half of the study period. This improvement reflects policy changes at NCCIW that were implemented in 2018 and 2019, including permitting the initiation of MOUD without signs or symptoms of active opioid withdrawal and involving obstetric providers in screening for OUD and referring for MOUD initiation during incarceration.23 Despite these progressive changes, a majority of pregnant people with OUD were not treated with MOUD during the study period. Of those people who did not initiate treatment during incarceration, only a very small proportion was referred for MOUD in the community. Although pre-incarceration receipt of MOUD was a significant predictor of MOUD receipt during incarceration, suggesting that the prison can serve as an important site of retention in MOUD, we also identified substantial gaps in MOUD retention. Referral for MOUD in the community was not universal for those who had received MOUD during pregnancy and participants who delivered while they remained incarcerated were withdrawn from MOUD at the time of hospital discharge. These policies reverse progress along the OUD treatment cascade by requiring that individuals re-engage with care in the community and re-initiate MOUD after leaving the prison.

Of all of the pre-incarceration substance use measures, only pre-incarceration heroin use was a significant predictor of MOUD receipt. We speculate that this association may be driven in part by differences in the severity of acute withdrawal by pre-incarceration opioid dose and route of administration, with heroin users potentially more likely to be injection users and to have used higher opioid doses.42 Active withdrawal symptoms were a prerequisite of MOUD initiation during the first half of the study period, and our clinical experience supports that even once eligibility for MOUD was expanded, those experiencing withdrawal symptoms on arrival to the prison facility were more likely to be referred for MOUD. We also identified that participants assigned to higher custody levels (i.e., medium or close custody) were more likely to receive MOUD compared with participants assigned to the minimum custody level. There is not an obvious policy corollary to this finding, as all participants were in the same facility and assessed by the same providers, although it may be that some of the same factors that are associated with heightened withdrawal symptoms are also associated with the measures used by the prison administration to assess security risks and assign custody levels.

Because withdrawal of MOUD postpartum in the community is not an evidence-based practice, our description of postpartum MOUD withdrawal experiences is novel. The somewhat more severe withdrawal experiences in the methadone group compared with participants who received buprenorphine is an expected finding consistent with the mechanisms of action and pharmacokinetics of the two medications. In the only randomized trial to date comparing methadone continuation versus withdrawal during incarceration, those who experienced withdrawal were significantly less likely to engage in care after returning to the community, were more likely to experience non-fatal overdoses, and were more likely to use heroin and inject drugs compared with those who had continued access to methadone.43,44 While administration of MOUD during incarceration has been shown to be highly beneficial, withdrawal during incarceration results in disruption in care and a decreased opioid tolerance that leads to the increased risk of overdose in the community and may contribute to the elevated risk of death for postpartum people with OUD that persists for a decade or more.12,25 The potential harms of withdrawal during incarceration are also supported by qualitative work showing that individuals who experience high levels of withdrawal symptoms from methadone during incarceration experience subsequent aversion to MOUD in the community.45

Our finding of a predominance of methadone use during incarceration despite more buprenorphine use prior to incarceration raises additional questions regarding withdrawal experiences and continuity of MOUD access. A substantial number of participants who received buprenorphine prior to incarceration received non-standard care once they were incarcerated. This may be due to a shorter duration of withdrawal symptoms compared with methadone leading to resolution of symptoms in jail prior to transfer to NCCIW. Given the relatively wide availability of buprenorphine for OUD in North Carolina, incarceration may be a substantial source of discontinuity in buprenorphine treatment.46 The statistically non-significant trend toward increased continuation of methadone compared with buprenorphine in our data may also point to disparate MOUD withdrawal experiences by medication type with unknown, but likely negative, consequences for ongoing treatment.

The findings of this study are limited by its retrospective nature and available prison records. Participants were identified for the study using paper records available for portions of each year during the study period. While the missing records are not expected to differ significantly, there are certainly some missed pregnant people with OUD identified only in the inaccessible records. In addition, abstraction of sensitive data from all medical records is dependent on information disclosed to health care providers. Additionally, our postpartum data analysis is particularly limited by small sample size and the relatively short duration of data collection for withdrawal symptoms.

Taken together, these findings are powerful despite the limitations. There are significant gaps in the OUD cascade of care for pregnant people who are incarcerated in North Carolina, both in access to MOUD initiation and retention in treatment. Those who do receive MOUD during incarceration experience meaningful withdrawal symptoms when medications are discontinued after delivery. These are important implementation concerns for an intervention that has demonstrated effectiveness at improving maternal outcomes, engagement in treatment, and abstinence from non-prescribed opioids, and decreasing overdose deaths during the community re-entry period both in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Future work must prioritize creating and adapting interventions to improve access to and retention in MOUD.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Only 40% of eligible pregnant people with opioid use disorder received either buprenorphine or methadone during incarceration

Fewer than one-third were referred for medications for opioid use disorder when they returned to the community after incarceration

Withdrawal symptoms are common among people whose buprenorphine or methadone are discontinued immediately postpartum during incarceration

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by a Cefalo Bowes Young Researcher Award from the Center for Maternal and Infant Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Knittel, Zarnick), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (Knittel, K12HD103085), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Lin, Moraes Tsujimoto, UL1TR002489).

Role of funding source: The funder had no role in the conception, analysis, or publication of the study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

We recognize the range of gender identities held by individuals who are pregnant. In particular, we strive to use the gender inclusive terms “pregnant person” or “pregnant people” to affirm that some people who have the physiologic ability to become pregnant and give birth do not identify as women. When previously published research has used the terminology “females” or “women,” we use those terms here for consistency. North Carolina Department of Public Safety (NCDPS) public and medical records do not include gender identity but report only sex-assigned-at-birth.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kerridge BT, Saha TD, Chou SP, et al. Gender and nonmedical prescription opioid use and DSM-5 nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:47–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krans EE, Patrick SW. Opioid use disorder in pregnancy: health policy and practice in the midst of an epidemic. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;128(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, Bohm MK, Callaghan WM. Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization—United States, 1999–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2018;67(31):845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Terplan M, et al. Fatal and Nonfatal Overdose Among Pregnant and Postpartum Women in Massachusetts. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018;132(2):466474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, Greene MF. Opioid Use in Pregnancy, Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, and Childhood Outcomes: Executive Summary of a Joint Workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Pediatrics, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the March of Dimes Foundation. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017;130(1):10–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen S, Flaherty C, Ely G. Throwaway Moms: Maternal Incarceration and the Criminalization of Female Poverty. Affilia. 2010;25(2):160–172. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 63. In. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones HE, Martin PR, Heil SH, et al. Treatment of opioid-dependent pregnant women: clinical and research issues. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35(3):245–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones HE, Deppen K, Hudak ML, et al. Clinical care for opioid-using pregnant and postpartum women: the role of obstetric providers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(4):302–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terplan M, Laird HJ, Hand DJ, et al. Opioid detoxification during pregnancy: a systematic review. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018;131(5):803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones HE, O’Grady K, Dahne J, et al. Management of acute postpartum pain in patients maintained on methadone or buprenorphine during pregnancy. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2009;35(3):151–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guttmann A, Blackburn R, Amartey A, et al. Long-term mortality in mothers of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome: A population-based parallel-cohort study in England and Ontario, Canada. PLoS medicine. 2019;16(11):e1002974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferszt GG, Clarke JG. Health care of pregnant women in U.S. state prisons. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(2):557–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bronson J, Stroop J, Zimmer S, Berzofsky M. Drug use, dependence, and abuse among state prisoners and jail inmates, 2007–2009. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carson EA. Prisoners in 2016. BJS Bull. 2018. (NCJ 251149). [Google Scholar]

- 16.James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. BJS Bull. 2006. (NCJ 213600). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sufrin C, Jones RK, Mosher WD, Beal L. Pregnancy Prevalence and Outcomes in US Jails. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(5):1177–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sufrin C, Beal L, Clarke J, Jones R, Mosher WD. Pregnancy Outcomes in US Prisons, 2016–2017. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(5):799–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin CE, Longinaker N, Terplan M. Recent trends in treatment admissions for prescription opioid abuse during pregnancy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sufrin C, Sutherland L, Beal L, Terplan M, Latkin C, Clarke JG. Opioid Use Disorder Incidence and Treatment Among Incarcerated Pregnant People in the US: Results from a National Surveillance Study. Addiction. 2020;115(11):2057–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staton M, Ciciurkaite G, Oser C, et al. Drug use and incarceration among rural Appalachian women: Findings from a jail sample. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(6):931941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staton M, Ciciurkaite G, Havens J, et al. Correlates of injection drug use among rural Appalachian women. J Rural Health. 2018;34(1):31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knittel AK, Zarnick S, Thorp JM, Amos E, Jones HE. Medications for opioid use disorder in pregnancy in a state women’s prison facility. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;214:108159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Handel MM, Rose CE, Hallisey EJ, et al. County-Level Vulnerability Assessment for Rapid Dissemination of HIV or HCV Infections Among Persons Who Inject Drugs, United States. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2016;73(3):323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ranapurwala SI, Shanahan ME, Alexandridis AA, et al. Opioid Overdose Mortality Among Former North Carolina Inmates: 2000–2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(9):1207–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, Stern MF. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):592–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cropsey KL, Lane PS, Hale GJ, et al. Results of a pilot randomized controlled trial of buprenorphine for opioid dependent women in the criminal justice system. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119(3):172–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaller N, McKenzie M, Friedmann PD, Green TC, McGowan S, Rich JD. Initiation of buprenorphine during incarceration and retention in treatment upon release. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;45(2):222–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT. Developing and Implementing a New Prison-Based Buprenorphine Treatment Program. J Offender Rehabil. 2010;49(2):91–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nunn A, Zaller N, Dickman S, Trimbur C, Nijhawan A, Rich JD. Methadone and buprenorphine prescribing and referral practices in US prison systems: results from a nationwide survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105(1–2):83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedmann PD, Hoskinson R, Gordon M, et al. Medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice agencies affiliated with the criminal justice-drug abuse treatment studies (CJDATS): availability, barriers, and intentions. Subst Abus. 2012;33(1):9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King Z, Kramer C, Latkin C, Sufrin C. Access to treatment for pregnant incarcerated people with opioid use disorder: Perspectives from community opioid treatment providers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;126:108338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Committee on Obstetric Practice, American Society of Addiction Medicine. Committee Opinion 711: Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34.North Carolina Department of Public Safety. N.C. Correctional Institution for Women. North Carolina Department of Public Safety Web site. https://www.ncdps.gov/adultcorrections/prisons/prison-facilities/nc-correctional-institution-for-women. Updated October 2020. Accessed May 14, 2021.

- 35.North Carolina Department of Public Safety, Office of Research and Planning. Automated System Query Custom Offender Reports. http://webapps6.doc.state.nc.us/apps/asqExt/ASQ. Accessed 4/29/2021.

- 36.Transfer of prisoners when necessary for safety and security; application of section to municipalities., General Statute of North Carolina §162–39 (Enacted 1957, last amended 2019).

- 37.North Carolina Correctional Institution for Women. 2015–2018 Statistical Report for Pregnant Admissions at NCCIW. In: North Carolina Department of Public Safety Freedom of Information Act Response, ed. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina American Civil Liberties Union; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stata Statistical Software (Version 13.1) [computer program]. College Station, TX: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [computer program]. Vienna, Austria: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Declercq E, Cunningham DK, Johnson C, Sakala C. Mothers’ reports of postpartum pain associated with vaginal and cesarean deliveries: results of a national survey. Birth. 2008;35(1):16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams AR, Nunes EV, Bisaga A, Levin FR, Olfson M. Development of a Cascade of Care for responding to the opioid epidemic. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smolka M, Schmidt LG. The influence of heroin dose and route of administration on the severity of the opiate withdrawal syndrome. Addiction. 1999;94(8):1191–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rich JD, McKenzie M, Larney S, et al. Methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal on incarceration in a combined US prison and jail: a randomised, open-label trial. The Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brinkley-Rubinstein L, McKenzie M, Macmadu A, et al. A randomized, open label trial of methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal in a combined US prison and jail: Findings at 12 months post-release. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;184:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maradiaga JA, Nahvi S, Cunningham CO, Sanchez J, Fox AD. ―I Kicked the Hard Way. I Got Incarcerated.‖ Withdrawal from Methadone During Incarceration and Subsequent Aversion to Medication Assisted Treatments. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;62:49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.North Carolina Pregnancy and Opioid Exposure Project. Services for Women with Opioid Exposed Pregnancies in North Carolina. https://ncpoep.org/services/. Published 2018. Accessed December 2, 2021, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.