Abstract

The conventional method for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Chlamydia trachomatis is subjective and potentially misleading. We have developed a reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR)-based method which is more sensitive and less subjective than the conventional method. Using 16 strains of C. trachomatis in triplicate assays, we found the RT-PCR method consistently more sensitive than the conventional technique for all eight antimicrobials tested, with resultant MICs determined by RT-PCR ranging from 1.6-fold higher (erythromycin) to ≥195-fold higher (amoxicillin).

Chlamydia trachomatis infections are responsible for a large proportion of involuntary infertility, pelvic inflammatory disease, and ectopic pregnancies in women, as well as urethritis and epididymitis in men and neonatal conjunctivitis and pneumonia in infants born to infected women (1, 6, 7, 9, 20). The more serious consequences are thought to be the result of persistent or chronic infections, which in many cases may be subclinical, even after apparently effective therapy (3, 4, 15).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of C. trachomatis is problematic, largely due to the organism’s unique life cycle (16). The current method of antimicrobial susceptibility testing by cell culture and immunofluorescence (IF) has many disadvantages, mainly due to subjective interpretation of results and limitations of sensitivity, and, as yet, there is no universally accepted technique (11, 18). Recently, a novel reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR)-based method of antimicrobial susceptibility testing was proposed for C. pneumoniae by amplification of the C. pneumoniae-specific DnaK (hsp70) transcript (13). However, only one strain was tested against six antibiotics. We have subsequently developed a similar but more reproducible method of antimicrobial susceptibility testing for C. trachomatis. The method of RT-PCR is an alternative approach to antimicrobial susceptibility testing, whereby amplification of C. trachomatis DnaK (Blastn search at NCBI; GenBank accession no. 27580) allows the presence of viable chlamydiae to be detected in cultures which may be considered negative by IF staining (13). The aim of this study was, therefore, to compare a novel RT-PCR-based method with a conventional technique in assessing the activities of eight antimicrobials against 16 C. trachomatis isolates when performed in triplicate.

A total of 16 C. trachomatis strains were obtained as fresh isolates from endocervical swabs from women presenting with a diagnosis of suspected chlamydial infection (n = 15) at the Department of Genitourinary Medicine, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, United Kingdom, between April and August 1997; an LGV1 (lymphogranuloma venereum serovar 1) isolate was kindly donated by M. Ward of the University of Southampton. The serovars of the isolates were determined by genotyping by the method of Lan et al. (14); they consisted of D (n = 2), E (n = 5), F (n = 1), G (n = 2), J (n = 1), K (n = 3), LGV1 (n = 1), and a mixed E and D (n = 1).

Tetracycline, amoxicillin, and erythromycin were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. Ltd. (Poole, Dorset, United Kingdom). Ofloxacin (Hoechst, Marion Roussel Ltd., Uxbridge, Middlesex, United Kingdom), ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin (Bay 12-8039; Bayer, Newbury, Berkshire, United Kingdom), clarithromycin (Abbott Laboratories, Maidenhead, Berkshire, United Kingdom), and azithromycin (Pfizer, Sandwich, Kent, United Kingdom) were all kindly donated as pure powders and were solubilized in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Chlamydiae were grown in a McCoy cell culture in RPMI medium, containing 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mg of glucose per ml, and 2 μg of cycloheximide per ml, that had been prepared in 24-well Nunclon tissue culture plates (Life Technologies, Paisley, United Kingdom). The inoculum was adjusted to yield approximately 5 to 10 inclusions per field at a magnification of ×400 and centrifuged onto confluent McCoy cells at 3,000 × g for 1 h at room temperature. After 1 h at 37°C, serial twofold dilutions of the antimicrobial agent being tested were added. Two tissue culture wells were used for each concentration of the antimicrobial agent, in addition to a positive control (no antimicrobial) and a negative control (McCoy cells with no inoculum). After incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 h, cells from one of the wells for each concentration of antimicrobial and from the positive and negative control wells were harvested for RNA extraction and subsequent RT-PCR, while the duplicate set of cells were incubated at 37°C for a further 24 h and stained with a species-specific fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated monoclonal antibody stain (Syva, Behring Diagnostics, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom). The MICs derived by the monoclonal antibody stain method were determined by counting the number of inclusions, the MIC being the lowest concentration with no inclusions visible.

Total RNA was extracted from a single inoculated well by using the Totally RNA kit (Ambion, AMS Biotechnology Ltd., Oxon, United Kingdom) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. To eliminate any contaminating DNA, 10 U of RNase-free DNase I (Life Technologies) was added to each RNA sample, followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 min.

The RT-PCR was carried out by using Tth DNA polymerase (Bioline, London, United Kingdom). To an RNase-free PCR tube, 10 μl of 5× Dual Perform reaction buffer (Bioline), 2 μl of 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 1.5 μl of 12.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 50 pmol of each oligonucleotide primer (forward primer, 5′CCTGCAAAACGTCAAGCAGT3′; reverse primer, 5′AATGCGTCCAGCATCTTTTG3′), 1 μg (35 U) of RNAguard (Pharmacia, St. Albans, Hertsfordshire, United Kingdom), 5 U of Tth DNA polymerase, 1 μg of RNA, and ultrapure water were added to a final volume of 50 μl. A negative PCR control contained the contents described above but with 5 μl of ultrapure water instead of RNA. The reaction mixtures were overlaid with 50 μl of mineral oil and subjected to 65°C for 5 min, 50°C for 5 min, and 70°C for 30 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94, 60, and 72°C for 1 min at each temperature. This was followed by a final elongation step of 72°C for 6 min. To detect the presence of contaminating DNA, a duplicate of the above reactions was performed, omitting the 65, 50, and 70°C steps for reverse transcription. PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized by UV transillumination. The lowest concentration of antibiotic which inhibited the appearance of a PCR product showing as a band on a gel determined the MIC.

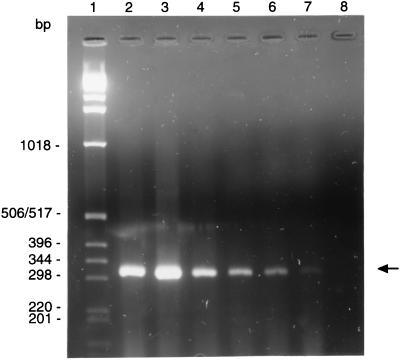

The RT-PCR resulted in the production of a 318-bp product (Fig. 1), which when analyzed by sequencing was as predicted from the nucleic acid sequence. No DNA amplification or McCoy cell RNA was observed. Moreover, no amplification of sample RNA was seen when it was treated with RNase.

FIG. 1.

RT-PCR amplification of DnaK transcripts from C. trachomatis LGV1 cultured in the presence and absence of amoxicillin with the MIC determined as ≥512 μg/ml. Lane 1, 1-kb ladder; lane 2, positive control; lanes 3 to 7; amoxicillin at 32 to 512 μg/ml; lane 8, PCR-negative control.

The MICs at which 50 and 90% of the isolates are inhibited and the ranges of MICs are summarized in Table 1. The MICs determined by IF were consistently lower than those determined by RT-PCR. Clarithromycin and moxifloxacin, followed by tetracycline, azithromycin, erythromycin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and amoxicillin, were the most active agents as determined by IF. As determined by RT-PCR, again, clarithromycin and moxifloxacin were the most active, followed by azithromycin, tetracycline, erythromycin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and amoxicillin. There was no difference in susceptibility between the LGV1 serovar and the other serovars tested, which meant that all data could be presented in a composite table.

TABLE 1.

In vitro susceptibilities to selected antimicrobial agents of 16 C. trachomatis strains as determined by IF and RT-PCR

| Antimicrobial | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IF

|

RT-PCR

|

|||||

| 50% | 90% | Range | 50% | 90% | Range | |

| Tetracycline | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.015–0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.03–1.0 |

| Amoxicillin | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1.0–8.0 | 512 | ≥1,024 | 128–≥1,024 |

| Erythromycin | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12–1.0 |

| Azithromycin | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.015–0.5 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.06–0.5 |

| Clarithromycin | 0.015 | 0.06 | 0.008–0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.008–0.25 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.015–0.12 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.015–0.25 |

| Ofloxacin | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.12–2.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 0.25–8.0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.25–2.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 0.5–8.0 |

The results obtained in this study fall within the range previously observed by IF staining (12, 19, 22, 23), and the MICs obtained by RT-PCR were consistently higher than those obtained by IF, as was demonstrated by previous work on Chlamydia pneumoniae (13). Also, of the 16 strains used in this study, no acquired resistance was seen. However, this is not surprising since antibiotic resistance appears to be a rare phenomenon in C. trachomatis and even though clinical isolates are seen very occasionally, few are well characterized or are generally made available for further study.

For all antimicrobials tested, the RT-PCR technique consistently resulted in observations of MICs that were higher than those resulting from IF staining. Since all tests were performed in triplicate, the reproducibility of these findings was confirmed. This increase in MIC ranged from a 1.6-fold increase (erythromycin) to a ≥195-fold increase (amoxicillin). The increase in MICs observed with RT-PCR illustrates the increase in sensitivity of the RT-PCR technique over IF staining (13). At concentrations at or above the MIC observed with IF staining, it is likely that chlamydial growth is suppressed sufficiently to inhibit detectable inclusion formation, resulting in a chlamydia-negative culture as determined by IF but allowing low-level replication that is detectable by RT-PCR (10, 13). An advantage of the RT-PCR technique over ordinary PCR methods is that only viable organisms will produce RNA which it alone can detect, in contrast to nonviable organisms which may release DNA and be detected by conventional PCR. In our experiments, we attempted to confirm this belief by passaging material from IF-negative but RT-PCR-positive wells at antibiotic concentrations close to the MIC. Not surprisingly, this proved to be successful in several cases. However, a major limitation of this approach is that culture followed by IF staining is inherently less sensitive than RT-PCR. Also, at concentrations at or above the MIC, inclusions which are very small or aberrant, bearing no morphological resemblance to classic inclusions, may be seen with certain antimicrobials (11, 21). These aberrant inclusions are not usually included in assessing antimicrobial susceptibilities but produce readily detectable levels of mRNA and are therefore potentially viable (13).

Amoxicillin has a poor effect on chlamydia, presumably due to the organism’s unusual cell wall, which contains no peptidoglycan (2, 17). The mean MIC of amoxicillin as determined by RT-PCR was ≥195-fold higher than the mean MIC determined by IF staining, with several strains producing mRNA at antibiotic concentrations of at least 512 μg/ml. This is to be expected when the mechanism of action of amoxicillin on chlamydia is taken into account and is consistent with previous studies showing limited growth of chlamydia in β-lactam antimicrobials at high levels (11). Penicillins allow conversion of elementary bodies to reticulate bodies but inhibit the multiplication of reticulate bodies and the differentiation of reticulate bodies into infectious elementary bodies, without necessarily exerting a lethal effect on the organism (2, 15).

It is known that the use of amoxicillin in the treatment of chlamydial infection is controversial. Our findings could provide a possible explanation of reports where amoxicillin has been judged to be an inadequate treatment for chlamydial infection (5, 8).

A potential problem with bacteriostatic antimicrobials in the therapy of C. trachomatis infections is the induction of latent or persistent forms of chlamydiae which result in an apparent eradication but which may allow subclinical progression of persistent infections (3). These aberrant forms, which are often not considered in IF antimicrobial susceptibility testing but which are detected by RT-PCR, may remain viable after antimicrobial therapy. Persistent chlamydia infections have been implicated in the pathogenesis of tubal factor infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and pelvic inflammatory disease, as well as scarring trachoma, and so warrant consideration in assessing antimicrobial therapy (3, 4, 10). We believe therefore that the RT-PCR method may be used as an alternative for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of C. trachomatis but that further clinical work is required to assess its potential usefulness.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant G9508430 from the Medical Research Council. We are grateful to SmithKline Beecham and Bayer for further financial support.

We thank M. W. Ward for providing the LGV1 isolate used in this study and G. L. Ridgway for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander E R, Harrison H R. Role of Chlamydia trachomatis in perinatal infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:713–719. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.4.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbour A G, Aman K, Hackstadt T, Perry L, Caldwell H D. Chlamydia trachomatis has penicillin-binding proteins but not detectable muramic acid. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:420–428. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.420-428.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beatty W L, Byrne G I, Morrison R P. Repeated and persistent infection with Chlamydia and the development of chronic inflammation and disease. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:94–98. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beatty W L, Morrison R P, Byrne G I. Reactivation of persistent Chlamydia trachomatis infection in cell culture. Infect Immun. 1995;63:199–205. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.199-205.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell T A, Sandstrom I K, Eschenbach D A, Hummel D, Kuo C-C, Wang S-P, Grayston J T, Foy H M, Stamm W E, Holmes K K. Treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis in pregnancy with amoxycillin. In: Mardh P-A, Holmes K K, Oriel J D, Piot P, Schachter J, editors. Chlamydial infections. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1982. pp. 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunham R C, MacLean I W, Binns B, Peeling R W. Chlamydia trachomatis: its role in tubal infertility. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:1275–1282. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.6.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cates W, Rolfs R T, Aral S O. Sexually transmitted diseases, pelvic inflammatory disease, and infertility: an epidemiologic update. Epidemiol Rev. 1990;12:199–219. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Csango P A, Gundersen T, Martinsen I M. Effect of amoxycillin on simultaneous Chlamydia trachomatis infection in men with gonococcal urethritis: comparison with three dosage regimens. Sex Trans Dis. 1985;12:93–96. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198504000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grayston J T, Wang S. New knowledge of chlamydiae and the disease they cause. J Infect Dis. 1975;132:87–106. doi: 10.1093/infdis/132.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holland S M, Hudson A P, Bobo L, Whittum-Hudson J A, Viscidi R P, Quinn T C, Taylor H R. Demonstration of chlamydial RNA and DNA during a culture-negative state. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2040–2047. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.2040-2047.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.How S J, Hobson D, Hart C A, Quayle E. A comparison of the in vitro activity of antimicrobials against Chlamydia trachomatis examined by Giemsa and a fluorescent antibody stain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;15:399–404. doi: 10.1093/jac/15.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones B R, Van der Pol B, Johnson R B. Susceptibility of Chlamydia trachomatis to trovafloxacin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39(Suppl. B):63–65. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.suppl_2.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan M A, Potter C W, Sharrard R M. A reverse transcriptase-PCR based assay for in vitro antibiotic susceptibility testing of Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:677–685. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lan J, Melgers I, Meijer C J L M, Walboomers J M M, Roorendaal R, Burger C, Bleker O P, Brule A J C V-D. Prevalence and serovar distribution of asymptomatic cervical Chlamydia trachomatis infections as determined by highly sensitive PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3194–3197. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3194-3197.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto A, Manire G P. Electron microscopic observations on the effects of penicillin on the morphology of Chlamydia psittaci. J Bacteriol. 1970;101:278–285. doi: 10.1128/jb.101.1.278-285.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moulder J W. Interaction of chlamydiae and the host cells in vitro. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:143–190. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.143-190.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moulder J W. Why is Chlamydia susceptible to penicillin in the absence of peptidoglycan? Infect Agents Dis. 1993;2:87–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peeling R W, Bowie W R, Dillon J R, Johnson R, Jones R B, Van der Pol B, Low D T, Martin D H, Newhall J, Orfila J, Rice R, Schachter J, Moncada J. Standardization of antimicrobial susceptibility testing for Chlamydia trachomatis. In: Orfila J, Byrne G I, Chernesky M A, Grayston J T, Jones R B, Ridgway G L, Saikku P, Schachter J, Stamm W E, Stephens R S, editors. Chlamydial infections. Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infections. Chantilly, France: Societa Editrice Esculapio; 1994. pp. 346–349. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice R J, Bhullar V, Mitchell S H, Bullard J, Knapp J S. Susceptibilities of Chlamydia trachomatis isolates causing uncomplicated female genital tract infections and pelvic inflammatory disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:760–762. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simms I, Catchpole M, Brugha R, Rogers P, Mallinson H, Nicoll A. Epidemiology of genital Chlamydia trachomatis in England and Wales. Genitourin Med. 1997;73:122–126. doi: 10.1136/sti.73.2.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanami Y, Yamada Y. Miniature cell formation in Chlamydia psittaci. J Bacteriol. 1973;114:408–412. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.1.408-412.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webberley J M, Matthews R S, Andrews J M, Wise R. Commercially available fluorescein-conjugated monoclonal antibody for determining the in vitro activity of antimicrobial agents against Chlamydia trachomatis. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1987;6:587–589. doi: 10.1007/BF02014256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodcock J M, Andrews J M, Boswell R J, Brenwald N N, Wise R. In vitro activity of BAY 12-8039, a new fluoroquinolone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:101–106. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]