Abstract

Context

The adverse skeletal effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) are partly caused by intestinal calcium absorption decline. Prebiotics, such as soluble corn fiber (SCF), augment colonic calcium absorption in healthy individuals.

Objective

We tested the effects of SCF on fractional calcium absorption (FCA), biochemical parameters, and the fecal microbiome in a post-RYGB population.

Methods

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 20 postmenopausal women with history of RYGB a mean 5 years prior; a 2-month course of 20 g/day SCF or maltodextrin placebo was taken orally. The main outcome measure was between-group difference in absolute change in FCA (primary outcome) and was measured with a gold standard dual stable isotope method. Other measures included tolerability, adherence, serum calciotropic hormones and bone turnover markers, and fecal microbial composition via 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Results

Mean FCA ± SD at baseline was low at 5.5 ± 5.1%. Comparing SCF to placebo, there was no between-group difference in mean (95% CI) change in FCA (+3.4 [–6.7, +13.6]%), nor in calciotropic hormones or bone turnover markers. The SCF group had a wider variation in FCA change than placebo (SD 13.4% vs 7.0%). Those with greater change in microbial composition following SCF treatment had greater increase in FCA (r2 = 0.72, P = 0.05). SCF adherence was high, and gastrointestinal symptoms were similar between groups.

Conclusion

No between-group differences were observed in changes in FCA or calciotropic hormones, but wide CIs suggest a variable impact of SCF that may be due to the degree of gut microbiome alteration. Daily SCF consumption was well tolerated. Larger and longer-term studies are warranted.

Keywords: prebiotic, calcium absorption, gastric bypass, obesity, bariatric surgery

Obesity now affects 42% of US adults, and 9% of US adults have severe obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥40 kg/m2) (1). Because of the escalating societal costs and higher mortality of obesity (2), there is growing interest in surgical weight loss as a part of a larger strategy for addressing this worsening public health crisis. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), one of the most common bariatric procedures performed worldwide, leads to durable weight loss and overall improvement in obesity-related comorbidities (3, 4). However, RYGB has the unintended consequence of inducing abnormalities in bone metabolism, with notable increases in bone turnover, substantial decreases in bone mineral density (BMD), and increased fracture incidence (5-14).

Contributing to the decline in skeletal integrity is the precipitous decline in intestinal calcium absorption capacity after RYGB. In a study of adults with obesity undergoing RYGB, fractional calcium absorption (FCA) dropped from 33% to 7% 6 months after surgery (P < .01) despite optimization of vitamin D status (15). Those participants with lower postoperative FCA had greater increases in bone resorption marker levels (ρ = –0.43, P = .01). As the large postoperative RYGB population increases in number and ages over time, it is critical to understand how to maintain calcium homeostasis to attenuate the negative skeletal effects of this otherwise beneficial weight loss procedure.

Calcium balance potentially could be maintained by taking vast amounts of calcium to overcome the postoperative low intestinal calcium absorption, but high pill burden and poor tolerability often render this approach impractical. Alternatively, calcium homeostasis could be improved by augmenting calcium bioavailability and absorption. One such untested strategy is the use of nondigestible fibers, termed prebiotics, to alter the gut microbiome. The human gut microbiome represents a dynamic ecosystem of microbes that are involved in essential host functions, including nutrient metabolism, vitamin synthesis, immunity, and hormone modulation (16). Increasing evidence indicates a role for the gut microbiome in bone metabolism (17-19). The gut microbiota, therefore, is a plausible potential target for manipulation to improve skeletal health.

Rodent and human research suggests that prebiotics such as soluble corn fiber (SCF) enhance calcium absorption in the lower intestine and may increase bone mass via alterations in the gut microbiome in healthy participants (20-24). In pubertal girls, a dose of 20 g/day of SCF for 4 weeks increased calcium absorption by 13% (P = .03) compared with placebo (22). In postmenopausal women, SCF improved skeletal calcium retention by 7% (P < .04) after 50 days (23). The proposed mechanism is that resident microbiota ferment prebiotic fibers to produce short-chain fatty acids in the colon, which improve the health of the intestinal epithelium and enhance mineral absorption possibly via reducing intestinal pH, increasing mucosal cell proliferation and surface area, or altering gene expression of the intracellular calcium transporters (25). A tasteless powder that readily dissolves in water and is very well tolerated in healthy populations (24, 26, 27), SCF could be a promising strategy to improve calcium homeostasis in the post-RYGB at-risk group, especially given the action of SCF in the intact lower intestine.

The aim of this study was to assess the ability of SCF to improve calcium homeostasis after RYGB in postmenopausal women, a population that is especially vulnerable to the adverse skeletal effects of RYGB (12). Our approach was to compare change in FCA after 2 months of SCF supplement vs placebo. Secondary objectives were to examine between-group differences in bone turnover markers and calciotropic hormone levels, adherence, and gastrointestinal tolerability. On an exploratory basis, we also examined changes in gut microbiome characteristics in response to SCF.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The study was a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial of a prebiotic treatment (SCF) on intestinal calcium absorption, bone metabolism, and gut microbiota in postmenopausal women who had undergone RYGB 18 months to 15 years prior. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco. The trial was registered at the US National Institutes of Health (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03272542).

Study Population

We recruited participants from 2 academic bariatric surgery centers (the University of California, San Francisco and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System) between November 2017 and October 2019. Participants were eligible if they were postmenopausal women (defined as last menstrual period or history of bilateral oophorectomy ≥3 years ago, or prior hysterectomy with serum follicle-stimulating hormone ≥30 mIU/mL), ≤75 years old, and 18 months to 15 years after RYGB. We limited our participants to postmenopausal women because this population is particularly at risk for the negative skeletal effects of RYGB (12). Exclusion criteria included 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) level <25 ng/mL, chronic kidney disease stage 4 or lower (estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2), hypercalcemia (serum calcium >10.2 mg/dL), hyperthyroidism, a history of >50% regain of weight lost after RYGB, use of medications that could impact calcium metabolism (eg, menopausal hormone therapy, osteoporosis pharmacotherapy, glucocorticoids), or use of supplements that could affect gut microbiota (eg, antibiotics, commercially available probiotics or prebiotics) in the previous 3 months.

Recruitment and Consent

We identified potential participants by screening patients of the 2 bariatric surgery centers. We mailed letters to these patients and approached them about the study during their annual follow-up clinic visits. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Randomization

Participants were randomized 1:1 to the prebiotic or placebo group using a computer-generated randomization scheme. Randomization numbers were assigned in consecutive order by the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System investigational pharmacist, who had no clinical involvement in the trial. Participants and the research team were blinded to the group assignments.

Prior to randomization, participants completed a 3-week run-in period during which they took an individualized dose of chewable calcium citrate supplement, designed to achieve a total calcium intake of approximately 1200 mg/day based on results from a validated calcium intake screener (28). This calcium supplementation replaced any usual calcium product taken prior to enrollment, and it continued during the study intervention period.

Study Intervention

The prebiotic group received 20 g of SCF (as 24 g of Promitor™ Soluble Fiber 85, Tate & Lyle Ingredients Americas LLC) orally in divided doses twice daily at least 1 hour apart for 2 months. SCF is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as a dietary fiber, and it has been used in previous clinical trials (22-24). The dose of prebiotic (20 g/day) was chosen because it had the greatest effect on FCA or bone calcium retention when tested in previous dose–response trials in pubertal girls and postmenopausal women (22, 23). This dose was well tolerated with minimal adverse effects. The 2-month duration was chosen because it exceeded the timeframe in the aforementioned trials (22-24). The placebo group received 24 g of maltodextrin (STAR-DRI™ maltodextrin, Tate & Lyle Ingredients Americas LLC). Maltodextrin is an easily digested polysaccharide, and it has a similar taste and physical appearance to the prebiotic. Maltodextrin was used as placebo control in previous SCF studies (22, 23).

Both prebiotic and maltodextrin powders were packaged into identical single-use preweighed sachets. Participants were instructed to mix the powder contents of 1 sachet into 250 mL of water and to consume 1 such beverage daily for the first week, then to increase to twice daily for the duration of 2 months. Participants were asked to substitute these drinks for a similar quantity of their usual daily water intake, but to make no other dietary changes. All participants were continued on calcium citrate supplementation throughout the intervention period.

Outcomes

Fractional calcium absorption

At baseline and treatment end, dual calcium isotopic tracers were used to determine FCA, with 1 stable calcium isotope administered orally to label dietary calcium and the other intravenously (IV) to measure calcium export via the blood (29). After an overnight fast, each participant consumed a standardized breakfast (lactose-free milk) containing a total of 300 mg of calcium along with a 10-mg dose of oral 44Ca as enriched calcium carbonate in a capsule mid-breakfast. One hour later, a 3-mg dose of 43Ca as enriched calcium carbonate was infused IV. Because orally and IV-administered calcium isotopes track identically in the blood after ~20 hours (30), a sample of serum was collected 24 hours after dual-isotope administration to calculate the FCA as the ratio of the oral to intravenous isotopes (31). Since we hypothesized that the prebiotics would work in the colon and the normal colonic transit time in healthy individuals is between 30 and 40 hours (32), participants returned for an additional blood draw 48 hours after isotope administration to more fully assess the calcium absorption profile, as performed in other prebiotic trials (22, 24, 33). Serum was frozen and sent to the University of Wisconsin-Madison State Laboratory of Hygiene for batched measurement of calcium isotope ratios (43Ca/42Ca and 44Ca/42Ca) by high-resolution, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (magnetic sector ICP-MS, Thermo-Fischer Element 2 XR). We were not able to collect serum samples from 1 participant, and instead we used sequential 24-hour composite urine samples (0-24 hours and 24-48 hours) for isotope ratio measurement and absorption determination for this participant. Each participant sample was analyzed on at least 2 occasions and the average of these data was used to calculate FCA. All ratio data were normalized to reference standards (High Purity Standards Calcium), which ran throughout the analytical sequence. Typical precision for both reference standards and participant samples was 0.2% to 0.6% for both 43Ca/42Ca and 44Ca/42Ca ratios. Using ratios of the calcium isotopes, we derived 2 FCA measurements, 1 over 24 hours and 1 over 48 hours. The change in FCA from baseline to end of treatment was the primary outcome of this study.

Biochemical markers of bone turnover and calciotropic hormones

At baseline and treatment end, fasting serum was analyzed for biochemicals including calcium, albumin, phosphate, and 25(OH)D. Samples were frozen immediately after collection at –80°C until batch analyzed for other analytes in a central laboratory (Main Medical Center Research Institute, Scarborough, ME, USA). Serum C-terminal cross-linked telopeptide (CTx; a marker of bone resorption), procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP; a marker of bone formation), parathyroid hormone (PTH), and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) were measured by chemiluminescence on an auto-analyzer (iSYS, Immunodiagnostic Systems, Scottsdale, AZ). The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation were 6.2% and 3.2% for CTx, 5.0% and 2.9% for P1NP, 5.5% and 2.7% for PTH, and 11.1% and 6.4% for 1,25(OH)2D. The 2 sequential 24-hour urine collections were sent for urinary calcium and creatinine measurements at a commercial laboratory (Quest Diagnostics, Secaucus, NJ, USA).

Tolerability, adherence, and acceptability

Using a short daily questionnaire, participants self-reported gastrointestinal symptoms including flatulence, bloating, abdominal pain, and stomach noises. As in previously published studies of SCF, symptoms were rated on a 10-point scale (0 = no symptoms, 10 = severe) (24, 26, 27). In addition to the daily assessment of gastrointestinal tolerability, adverse events were recorded at each study contact or when otherwise volunteered by the participant. Treatment adherence was self-recorded using the same short daily questionnaire of gastrointestinal symptoms, where participants were asked to darken a circle for each sachet consumed that day. At treatment period end, a self-administered questionnaire evaluated acceptance of the beverage and likelihood that a participant would be willing to consume it for 12 months.

Gut microbial profiling

Stool samples were collected at baseline and at the end of the treatment period (while still on study intervention). Participants were instructed to collect the first bowel movement of the day each time. Participants stored their samples in their home freezers (–20°C) until delivering them on ice to the study team. Samples were then stored at –80°C until processing. DNA was extracted from all stool samples using a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide buffer extraction protocol as previously described (34). DNA concentration was measured using the QuantiFluor dsDNA System on a Quantus Fluorometer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). 16S sequencing was performed by Omega Bioservices (Norcross, GA, USA) using the V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences on HiSeqX10 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

Sequence analysis was performed in R (version 4.0.3). A table of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) and assigned taxonomy were generated using the NG-Tax 2.0 pipeline (35). ASVs were discarded if determined to be chimeric, nonbacterial origin, common contaminants observed in >50% of extraction controls, or had read counts less than 0.001% of the total read count. Sample read numbers were representatively rarefied to 20 000 reads as a means of normalization, as we have previously described (36). α-Diversity, a within-sample diversity measure, was calculated using Shannon diversity index, Faith’s phylogenetic diversity index, Chao1 metrics (richness), and equitability (evenness). β-Diversity, a between-samples compositional dissimilarity measure, was calculated using weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances with the function UniFrac in the R package phyloseq (version 1.34), and by using Bray–Curtis dissimilarity and Canberra distance with the vegan package (version 2.5-7) in R.

Dietary intakes, BMD, and body composition

Habitual dietary intakes were assessed at baseline using the comprehensive Block Food Frequency Questionnaire (37). At baseline, we measured areal BMD at the lumbar spine, proximal femur, and radius using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Horizon A, Hologic). Using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, we also estimated total and regional body composition (38). At baseline and follow-up, weight and height were measured, and BMI (kg/m2) was calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size planning for this trial was based on the mean and SD for 6-month postoperative FCA (6.9 ± 3.8%) in our pre–post gastric bypass cohort study (15) and covariance parameters in a trial of SCF in adolescents (22). We calculated that a sample of 20 participants (10 in each group) would provide 80% power to estimate the effect of treatment on FCA within a margin of sampling error of 0.026 (ie, absolute between-group difference in change of 2.6%). This is smaller than the between-intervention difference in a crossover SCF trial in adolescents (24).

Analysis was based on intention-to-treat, and participants with missing data were excluded from those specific analyses. Significance level was defined as 2-sided P < .05, and confidence intervals at 95%. Baseline descriptive data for intervention and control groups were reported as means ± SD or proportions (N [%]) and compared using t-tests for continuous variables or chi-squared test for proportions. The primary outcome (mean change in FCA) and secondary outcomes (gastrointestinal symptom severity, adherence, acceptability, and the mean change in CTx, P1NP, PTH, 25OHD, 1,25(OH)2D, and urinary calcium levels) were compared between intervention and placebo groups using a 2-sided t-test or Mann–Whitney U test depending on normality of the outcomes or chi-squared test for proportions. Within-group changes in the outcomes were assessed using paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

For gut microbiota analyses, differences in α-diversity between groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA (39) using the adonis function in the R package vegan [version 2.5.7]) was performed to determine factors that significantly (P < .05) explained variation in microbial β-diversity. Linear models were used to estimate associations between microbiome characteristics (α-diversity or changes in β-diversity) and the outcome variables. Within-group changes in α-diversity pre–post intervention were tested with Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Factors that explained the variance in microbiota β-diversity pre–post intervention (repeated measures) were assessed using linear mixed effects models using the first and second principal coordinates of the distance matrices. Significant enrichment of taxon relative abundance between groups or by outcome variables was determined using DESeq2 package (version 1.30.0) (40), which employed the Wald test applied to a negative binomial distribution model and corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method (41). Differentially enriched taxa pre–post intervention was analyzed with a mixed effects model for repeated measures. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 software (StataCorp, Texas, USA) and R (version 4.0.3).

Results

Enrollment and Baseline Participant Characteristics

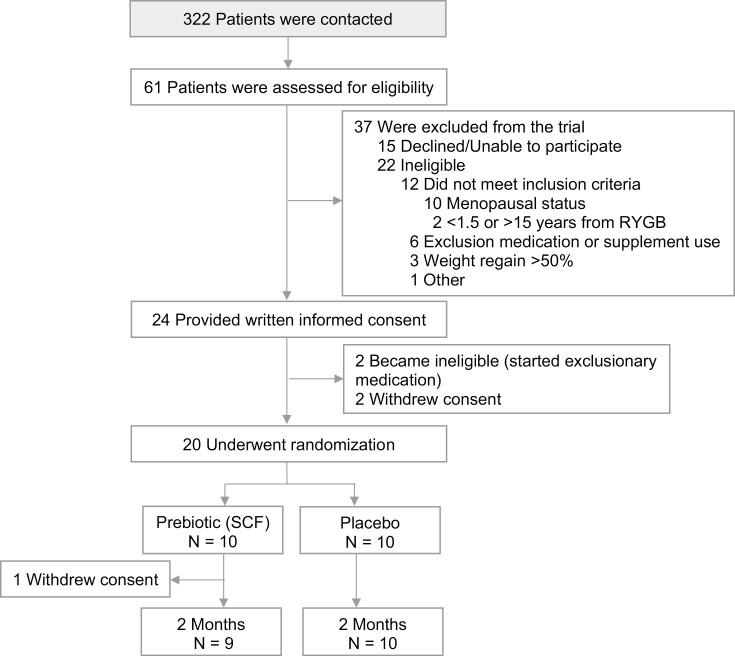

A total of 322 patients were contacted for the study, 61 assessed for eligibility, and 24 consented to participate. Twenty were randomized, 1 withdrew due to lack of time, and 19 completed the study (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

At baseline, mean age was 62 years, BMI was 32 kg/m2, and time since RYGB was 5 years (Table 1). The 2 treatment groups had similar demographics, dietary patterns, and calcium homeostasis, aside from an imbalance of self-reported race and a lower 24-hour urinary calcium in the prebiotic group. Among all participants (N = 20), mean baseline FCA ± SD was low at 5.5 ± 5.1% over 24 hours and 4.4 ± 6.7% over 48 hours. Even among the 15 participants not taking a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), the mean baseline FCA ± SD was low at 6.4 ± 6.6% over 24 hours and 6.9 ± 4.5% over 48 hours. Mean PTH ± SD was 66.6 ± 22.1 pg/mL, which was within the upper limit of the reference range (normal range 11.5–78.4 pg/mL), and 1,25(OH)2D was 104.2 ± 26.8 pg/mL, which exceeded the normal range of 15.2–90.1 pg/mL. At baseline, participants had a mean areal BMD ± SD of 1.01 ± 0.13 g/cm2 at the lumbar spine and 0.74 ± 0.12 g/cm2 at the femoral neck. The mean ± SD T-scores were –0.4 ± 1.1 at the lumbar spine and –0.9 ± 1.0 at the femoral neck, both consistent with normal bone mass.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Prebiotic (N = 10) | Placebo (N = 10) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.1 ± 5.8 | 60.9 ± 4.7 | .36 |

| Race, n (%) | .01 | ||

| White | 4 (40) | 9 (90) | |

| Black/African American | 6 (60) | 0 (0) | |

| More than 1 race | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | |

| Weight, kg | 86.1 ± 15.4 | 83.1 ± 13.3 | .64 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.9 ± 4.7 | 31.4 ± 5.7 | .82 |

| Time since RYGB, year | 5.0 ± 3.2 | 4.8 ± 2.6 | .92 |

| PPI use, n (%) | 2 (20) | 3 (30) | .61 |

| Calcium intake, mg/24 hours | 1104 ± 330 | 1231 ± 515 | .54 |

| Dietary | 724 ± 365 | 686 ± 301 | .82 |

| Supplement | 541 ± 339 | 546 ± 434 | .98 |

| Dietary fiber, g/24 hours | 10.4 ± 7.9 | 11.9 ± 3.1 | .61 |

| Soluble | 2.6 ± 2.2 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | .61 |

| Insoluble | 7.7 ± 5.8 | 8.8 ± 2.4 | .61 |

| Food energy, kcal/24 hours | 1231 ± 750 | 1264 ± 304 | .91 |

| FCA over 24 hours, % | 6.7 ± 5.2 | 4.3 ± 5.1 | .32 |

| FCA over 48 hours, % | 3.5 ± 5.4 | 5.3 ± 8.0 | .56 |

| Serum calcium, mg/dL | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | .69 |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 36.5 ± 8.2 | 39.5 ± 7.8 | .41 |

| 1,25(OH)2D, pg/mL | 108.1 ± 26.0 | 100.3 ± 28.3 | .53 |

| PTH, pg/mL | 70.8 ± 23.2 | 62.4 ± 21.2 | .41 |

| CTx, ng/mL | 0.59 ± 0.28 | 0.74 ± 0.43 | .35 |

| P1NP, ng/mL | 78.3 ± 44.5 | 79.3 ± 35.0 | .95 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.78 ± 0.14 | 0.68 ± 0.14 | .12 |

| eGFR, mL/min | 89.6 ± 14.3 | 91.5 ± 11.8 | .75 |

| Urine calcium, mg/24 hours | 76.2 ± 52.8 | 173.1 ± 113.9 | .03 |

| Areal BMD, g/cm2 | |||

| Lumbar spine | 1.02 ± 0.10 | 0.98 ± 0.16 | .56 |

| Total hip | 0.86 ± 0.12 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | .56 |

| Femoral neck | 0.76 ± 0.15 | 0.71 ± 0.08 | .43 |

Values are means ± SD.

95% reference intervals provided by the test manufacturers: PTH, 11.5-78.4 pg/mL; CTx, 0.142-1.351 ng/mL (post-menopausal women); P1NP, 27.7-127.6 ng/mL; 1,25(OH)2D, 15.2-90.1 pg/mL.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; FCA, fractional calcium absorption; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25(OH)2D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; PTH, intact parathyroid hormone; CTx, collagen type 1 C-telopeptide; P1NP, procollagen 1 intact N-terminal propeptide; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; BMD, bone mineral density.

Changes in FCA, Bone Turnover Markers, and Calciotropic Hormones

We observed no difference in the change in FCA between the 2 groups, over 24 or 48 hours (Table 2). Results did not differ between PPI users and nonusers (Pinteraction = 0.87 for change in FCA over 24 hours and Pinteraction = 0.88 for change in FCA over 48 hours). The mean between-group difference (95% CI) in absolute change in FCA over 24 hours was –1.3 (–8.6, +6.1) % in prebiotic vs placebo groups, whereas FCA over 48 hours was +3.4 (–6.7, +13.6) %. Expressed as percentage change, the mean between-group difference (95% CI) in FCA over 24 hours was +93.0 (–123.6, +309.6) %, and over 48 hours, +382.4 (–168.2, +933.0) %. Changes in FCA within each group were not statistically significant. Change in FCA showed a wide variation among participants (Fig. 2). For the absolute change in FCA over 48 hours, the SCF group had an SD of 13.4%, whereas the placebo group had an SD of 7.0%.

Table 2.

Changes in fractional calcium absorption, bone turnover markers levels, and calciotropic hormone levels with soluble corn fiber (prebiotic) vs placebo

| Within–group change Mean (95% CI) | Between group difference Mean (95% CI) | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | Prebiotic (N = 9) | P | Placebo (N = 10) | P | ||

| Absolute | ||||||

| FCA over 24 hours, % | +0.6 (–5.9, +7.2) | .83 | +1.9 (–2.9, +6.7) | .77a | –1.3 (–8.6, +6.1) | .86a |

| FCA over 48 hours, % | +3.6 (–6.7, +13.9) | .44 | +0.2 (–4.8, +5.2) | .94 | +3.4 (–6.7, +13.6) | .49 |

| Percentage | ||||||

| FCA over 24 hours, % | +104.8 (–86.5, +296.0) | .24 | +11.7 (–130.0, +153.5) | .63a | +93.0 (–123.6, +309.6) | .84a |

| FCA over 48 hours, % | +324.9 (–300.0, +949.8) | 1.00a | –57.5 (–163.3, +48.2) | .25 | +382.4 (–168.2, +933.0) | .40a |

| Serum Ca, mg/dL | +0.0 (–0.2, +0.2) | 1.00 | –0.1 (–0.2, +0.1) | .34 | +0.1 (–0.2, +0.3) | .56 |

| Serum Cr, mg/dL | +0.0 (–0.1, +1.3) | .68a | +0.0 (–0.0, +0.1) | .69 | +0.0 (–0.1, 0.1) | .81a |

| CTx, ng/mL | –0.05 (–0.14, +0.04) | .22 | –0.10 (–0.17, –0.02) | .02 | +0.04 (–0.06, +0.15) | .41 |

| P1NP, ng/mL | –8.4 (–18.4, +1.7) | .09 | –8.6 (–19.7, +2.5) | .12 | +0.2 (–13.8, +14.2) | .97 |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | –1.8 (–6.7, +3.2) | .43 | –1.0 (–5.7, +3.7) | .64 | –0.8 (–7.1, +5.5) | .80 |

| PTH, pg/mL | –3.1 (–17.6, +11.4) | .64 | –0.4 (–6.8, +6.1) | .90 | –2.7 (–17.9, +12.4) | .70 |

| 1,25(OH)2D, pg/mL | –11.2 (–24.4, +2.0) | .09 | +5.0 (–16.9, +26.9) | .62 | –16.2 (–40.6, +8.2) | .18 |

| Urine Ca, mg/24 hours | –0.5 (–42.3, +41.3) | .98 | –36.3 (–66.0, –6.7) | .02 | +35.8 (–10.7, +82.3) | .12 |

Abbreviations: FCA, fractional calcium absorption; Ca, calcium; Cr, creatinine; CTx, collagen type 1 C-telopeptide; P1NP, procollagen 1 intact N-terminal propeptide; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; PTH, intact parathyroid hormone; 1,25(OH)2D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.

a P value calculated based on Wilcoxon signed-rank or Mann–Whitney U test due to a non-normal distribution. Otherwise, paired or 2 sample t-test.

Figure 2.

Fractional calcium absorption before and at end of intervention by treatment group. (A) FCA over 24 hours (%) after dual-isotope administration. (B) FCA over 48 hours (%) after dual-isotope administration.

There were no significant between-group differences in change in bone turnover or calciotropic hormone levels (Table 2). The mean between-group difference (95% CI) in change in PTH was –2.7 (–17.9, +12.4) pg/mL in prebiotic vs placebo groups, and in 1,25(OH)2D, –16.2 (–40.6, +8.2) pg/mL. The mean between-group difference in change in 24-hour urinary calcium was an increase of +35.8 mg/24 hour, which was driven by a decrease in the placebo group with a mean within-group decrease of –36.3 mg/24 hour.

Adherence, Tolerability, and Acceptability

Overall adherence (mean ± SD) was 82.2 ± 28.1% and 94.2 ± 4.1% in the prebiotic and placebo groups, respectively (P = .20).

Real-time self-reported daily gastrointestinal symptoms were low in both groups, and not different between the 2 groups (Table 3). On a 10-point scale, the median (IQR) of the average symptom scores per participant in the prebiotic group was 0.0 (0.0, 2.6) for bloating, 1.0 (0.0, 2.9) for flatulence, 0.1 (0.0, 2.1) for abdominal pain, and 0.01 (0.0, 1.0) for gut noise. The proportions of participants who reported a symptom score >5 on any day during the intervention period were also not different between groups. Adverse events judged possibly related to the intervention occurred among 3 participants, all belonging to the prebiotic group; gastrointestinal complaints including discomfort, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were constituted 2 out of 3 of these adverse events with the other being fatigue. There were 6 unrelated adverse events (4 prebiotic, 2 placebo) reported by 3 participants.

Table 3.

Self-reported symptoms scores and adverse events

| Prebiotic (N = 10) | Placebo (N = 10) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| GI symptom scores | ||

| Bloating | 0.0 (0.0, 2.6) | 0.1 (0.03, 0.6) |

| Flatulence | 1.0 (0.0, 2.9) | 0.6 (0.0, 1.1) |

| Abdominal pain | 0.1 (0.0, 2.1) | 0.2 (0.04, 0.4) |

| Gut noise | 0.01 (0.0, 1.0) | 0.5 (0.1, 1.2) |

| Score >5 anytime during intervention | N (%) | N (%) |

| Bloating | 4 (40) | 4 (40) |

| Flatulence | 6 (60) | 3 (30) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (40) | 2 (20) |

| Noise | 3 (30) | 4 (40) |

The survey assessing acceptability was completed by 8 of 10 prebiotic and 7 of 10 placebo group participants. The majority of participants would consider taking the twice-daily powder beverage on an ongoing long-term basis (8/8 prebiotic, 5/7 placebo) and would be willing to participate in another trial lasting for 12 months (8/8 prebiotic, 6/7 placebo).

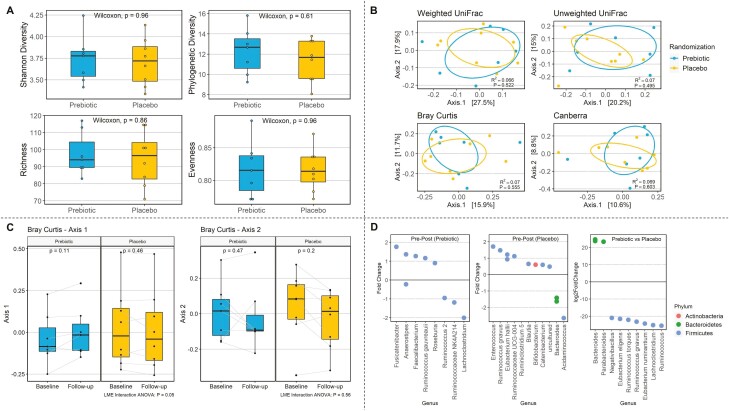

Gut Microbiota

Paired pre–post intervention fecal microbiota data were available for 15 participants, and treatment-end microbiome data for 16 participants. Neither α-diversity (within-sample diversity) or β-diversity (between-group dissimilarity) differed between prebiotic (N = 7) and placebo (N = 9) after 2 months of intervention (Fig. 3A and 3B). There was also no within-group change in either α-diversity or β-diversity over the treatment period (paired samples N = 7 prebiotic, N = 8 placebo). However, the shift in microbial community composition was more pronounced in the prebiotic group than the placebo group when compared using a Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix, which weights dominant and rare ASVs equally (P = .05; Fig. 3C). At treatment period end, the relative abundance of Bacteroides and Parabacteroides was significantly higher in the prebiotic group, whereas Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae were more abundant in the placebo group (Fig. 3D). These differences were driven by a pre–post decrease in Bacteroides and increase in Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae in the placebo group, rather than a shift in the prebiotic group (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Exploratory gut microbiome outcomes. (A) α-Diversity (within sample microbial diversity) between treatment groups at end of intervention with Shannon diversity index, phylogenetic diversity, richness, and evenness measures. (B) β-Diversity (between-sample compositional dissimilarity) with weighted UniFrac, unweighted UniFrac, Bray–Curtis, and Canberra. (C) Shift in microbial community composition pre–post intervention between treatment groups with Bray–Curtis dissimilarity measure (ordination axes 1 and 2 shown here). The P values were derived from Wilcoxon signed-rank test, indicating whether each β-diversity ordination axis differed from baseline to follow-up within each randomization group. Linear mixed-effects interaction analysis of variance P values were derived from a linear mixed-effects model and two-way analysis of variance test, indicating whether the shift in β-diversity across baseline and follow-up differed between the prebiotic and placebo groups (ie, β-diversity ordination axis as a function of randomization group and timepoints). (D) Significantly different taxa relative abundance pre–post intervention in prebiotic group, pre–post intervention in placebo group, and between treatment groups (prebiotic vs placebo) at end of intervention.

Cross-sectionally at follow-up, among all participants (N = 16), overall microbial composition (β-diversity weighted UniFrac) differed across the increment from FCA over 24 hours to FCA over 48 hours (r2 = 0.10, P = .02). Meanwhile, the association between FCA over 48 hours and microbial community composition approached statistical significance (r2 = 0.09, P = .08). This suggests that the variations in microbial community composition relate to late FCA values across these subjects. Among the paired samples from the prebiotic group (N = 7 pre–post pairs), those exhibiting a greater change in microbial composition (weighted UniFrac) following the intervention also exhibited significantly increased FCA over 24 hours (r2 = 0.72, P = .05). The point estimate strengthened with adjustment for age and BMI (r2 = 0.82).

Discussion

We report the first trial to investigate a prebiotic intervention in the post-RYGB population to improve intestinal calcium absorption. Daily SCF consumption was well tolerated in postmenopausal women with a history of RYGB, and adherence and acceptability were high. We did not find statistically significant between-group differences in FCA change (primary outcome) or in changes in bone turnover marker or calciotropic hormone levels, although confidence intervals were wide, suggesting there may be variable impact of SCF across this population.

RYGB leads to intestinal malabsorption of calcium assessed at 6 to 24 months of postoperative time points (15, 42, 43), independent of vitamin D status (15). In this trial, we determined that FCA remains low at <10% after a mean 5 years after surgery. The finding suggests that the gut’s capacity to absorb calcium does not recover after time postoperatively. Calcium is absorbed via 2 mechanisms: an active transcellular process regulated by vitamin D primarily in the duodenum and a paracellular diffusional process throughout the intestine (44, 45). A prior rat model showed a compensatory upregulation of an epithelial calcium channel, transient receptors potential vanilloid type 6, in the duodenum and jejunum 16 weeks after RYGB, with an increase in passive calcium absorption in the distal small intestine (46). However, this higher expression of transient receptors potential vanilloid type 6 may be ineffective given that the proximal intestine no longer receives nutrient flow after RYBG, and relying on passive calcium absorption may simply be insufficient to correct the problem in the face of an altered anatomy. PPI use could contribute to the low FCA in some, although in our trial, the majority of the participants were not taking PPIs and the mean baseline FCA was still <10% among nonusers. As a result of chronic low intestinal calcium absorption, secondary hyperparathyroidism may lead to bone loss and increased fracture risk. In our trial, even with optimization of serum 25OHD levels and the recommended total daily calcium intake of 1200 mg, the mean PTH level remained high-normal and 1,25(OH)2D level was frankly high, in the setting of normocalcemia. Given the finding, recommended calcium intake may need to be increased for patients after RYGB, although further research is needed to determine the specific approach.

In this population at high risk for poor bone health, an adjunctive strategy to improve intestinal calcium absorption, such as a prebiotic, could be of high significance. Potential utility is especially great in this population that often has a difficult time tolerating large or multiple pills, and poor long-term adherence to multivitamin and calcium supplementations (47, 48). In pubertal girls, the prebiotic SCF at 20 g/day for 4 weeks increased calcium absorption by 13% (22), while in postmenopausal women, SCF improved bone calcium retention by 7% at 50 days (23). In this trial, we did not find a statistically significant between-group difference in FCA change during the 2-month treatment period, even when FCA was measured out to 48 hours (instead of the more common 24 hours) to evaluate late-stage absorption. However, wide confidence intervals for these results suggest variable responses to the prebiotic. For example, our best estimate for the difference in change in FCA over 48 hours between prebiotic and placebo group was +3.4%, while the upper limit of the 95% CI was +13.6%. Given the small sample size and a larger SD of FCA than predicted, we cannot exclude a difference between groups. Our secondary outcomes showed a mean decrease in both PTH and 1,25(OH)2D levels with prebiotic compared to placebo, and while not statistically significant, the direction of these changes is consistent with the hypothesized benefit. While an increase in FCA as small as +3.4% may seem trivial, it could be clinically significant in this post-RYGB population with a very low baseline FCA. In a healthy postmenopausal woman on an average of 800 mg elemental calcium per day, the average FCA is approximately 25% (49), equivalent to a net 200 mg elemental calcium per day. In this trial, the mean baseline FCA was 5.5%, which means a daily oral intake of 3600 mg of elemental calcium would be needed to maintain the same net calcium input. An increase of 3.4% in FCA would decrease the required oral calcium intake to 2200 mg daily, roughly 3 fewer pills of 500 mg of calcium and thus easier to achieve and maintain.

In our exploratory evaluation of the gut microbiome, although the overall microbial diversity and composition did not differ between the prebiotic and placebo group, we found that those with greater change in fecal microbial composition had greater increase in FCA. Various factors can contribute to the interindividual variability in the composition and function of the gut microbiota, thereby producing a differential response to prebiotic. Factors such as diet and physical activity have been shown to impact the gut ecosystem (50-54). In addition, the colonic transit time and duration of exposure to undigested nutrients strongly influence the metabolic activities of gut microbiota (55). A recent study found that the colonic transit time in patients at least 1 year out from RYGB was on average 29.4 hours with a wide standard deviation of 17.5 hours (56). Differences in colonic transit time may be related to the use of medications such as opioids and antidepressants (57, 58), individual gut adaptation to compensate for the shorter oro-cecal transit time, and differing bowel habits. With our current study, given the small sample size, we were unable to identify specific variables that separated responders from the nonresponders. Determining microbiological features that interact with prebiotic interventions to promote treatment response would permit optimization of potential synbiotic (microbial and prebiotic) interventions that might reduce variability.

Compared with prior human studies where SCF altered the microbial diversity and community composition with shifts in several bacterial groups in healthy adolescent females (22) and healthy subjects aged 60-80 years (26), this SCF intervention was not as effective overall in altering the gut microbiome in our post-RYGB postmenopausal women. One reason may be that it is more difficult to induce a change in the gut microbiome in a postbariatric surgery population. RYGB leads to a rapid shift in the composition and functional capacity of the gut microbiota as early as 1 to 3 months, which persists long term (59-63). The changes to the gut microbiome are distinct from changes induced by medical weight loss (64). Therefore, the persistent alteration of the gut microbiome after RYGB can be attributed not only to postoperative dietary modifications but also anatomical changes leading to altered metabolism and flow of bile acids, food transit time, gastric pH, enterohepatic cycle, and modulation of gut hormones (65). We speculate that because of the anatomical and microbiological changes to the digestive tract with RYGB, a higher dose and longer duration of prebiotic, perhaps in combination with (re)introduction of bacterial species that metabolize the prebiotic (ie, a synbiotic), may be needed for this population to induce a more consistent and meaningful change to the gut microbiome.

The prebiotic group had mostly stable microbial composition but had shifts in abundances within the families of Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae. These bacteria are some of the main short-chain fatty-acid producers from the fermentation of nondigestible fibers (66, 67). Short-chain fatty acids serve as a source of energy for colonocytes, and it has been hypothesized that an enhanced production of short-chain fatty acids augments colonic calcium absorption by improving the health of enterocytes, increasing mucosal cell density, intestinal crypt depth, and blood flow, augmenting gene expression of the intracellular calcium transporters, and increasing solubility of calcium from decreased luminal pH (25, 68, 69). Interestingly, the placebo group had an overall pre–post increase in Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae. The reason the placebo group had changes in these families of bacteria is unclear and may be a random finding. However, we cannot rule out that the maltodextrin placebo may play a role in this shift. Maltodextrin, an artificial polysaccharide used as a food additive, is easily digestible and normally fully absorbed in the small intestine. After RYGB, a more rapid oro-cecal transit time may enable maltodextrin to reach the colon (56, 70) and subsequently alter the bacteria involved in carbohydrate metabolism. We also found an enrichment in the Bifidobacterium genus and a reduction in the Bacteroides genus in the placebo group, a shift described previously with intake of digestible carbohydrates in healthy participants (54, 71, 72). Therefore, maltodextrin may not be inert in this population. It is worth noting, though, that the observed compositional changes in these bacterial abundances may not reflect changes in the microbial metabolic functions. Furthermore, bacterial microbiota is one component of the entire gut microbiome, and we did not assess the viral, fungal, and archaeal microbiota. In addition, fecal microbiota data were missing in a quarter of the participants resulting in a small sample size. Future larger studies focusing on the changes in the functional status of the full microbial community with the prebiotic would be beneficial to elucidate the underlying mechanism.

At baseline, the prebiotic group had a 24-hour urinary calcium excretion that was lower than the placebo group. There was also an imbalance in self-reported race between the 2 groups, with the prebiotic group having more Black participants. Prior studies have observed that Black adults in the United States have lower daily urinary calcium excretions across all ages than White adults (73, 74). Postmenopausal Black women have been reported to excrete on average 65 mg less urinary calcium a day than White women (75). A potential racial difference has been explored (76, 77), although the use of race as a proxy for biological differences is under scrutiny (78). In our study, we found no baseline difference in daily calcium intake, FCA, or level of calciotropic hormones including PTH, 25OHD, and 1,25(OH)2D between the prebiotic and placebo group. Therefore, the difference in race and the 24-hour urinary calcium likely did not affect the outcomes. After 2 months of intervention, there was a significant decrease in 24-hour urinary calcium level in the placebo group, which further suggests the difference in 24-hour urinary calcium may simply be a random chance finding. We noted also that there was a statistically significant within-group decrease in CTx level in the placebo group of ~14% (0.1 ng/mL). Bone resorption could decrease as a result of the calcium supplement all participants were provided, but perhaps more likely, this may be a random chance finding given the higher CTx level at baseline in the placebo group (“regression to the mean”). Further, the change might be partly explained by variation in bone turnover marker measurements even in the fasting state.

Strengths of this trial include its rigorous randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design, and the use of a gold-standard, dual-stable isotope methodology to determine FCA. FCA was measured not only over 24 hours, the traditionally assessed interval, but also over 48 hours. The trial also has several limitations. Based on the findings from our previous cohort study (15) and trials of SCF in adolescents (22, 24), we estimated that our modest sample size would provide sufficient power to detect a change in FCA of a reasonable effect size. However, the variability of FCA in our participants was larger than expected, which limited our ability to draw firm conclusions about the efficacy of the prebiotic intervention. Our primary outcome was difficult to measure in this population with low FCA at baseline. One participant had a negative value for FCA over 24 hours and 6 participants over 48 hours. A negative FCA may indicate an overall net negative calcium balance in this population, but another potential explanation is that the FCA capacity in this population is so low that the amount absorbed was not able to perturb the natural abundance of the Ca44/Ca42 isotope ratio, leading to random variation that can mask a true small change in FCA. Two potential confounding factors—race and baseline urinary calcium—were imbalanced by chance due to the small sample size. Other unmeasured factors such as changes in diet and physical activity during the intervention period could potentially alter the gut microbiome and influence the results. However, participants were explicitly instructed to make no alterations in their dietary habits or lifestyle, and no participant reported major changes. In addition, we studied postmenopausal women because they are particularly affected by the negative skeletal effects of RYGB (12), and results may not be generalizable to all other post-RYGB groups.

In conclusion, the present study aimed to determine whether treatment with a prebiotic could improve FCA in postmenopausal women after RYGB, which could ultimately mitigate in part the negative skeletal effects of the procedure. Although no significant differences were seen in mean change in FCA or calciotropic hormones, the wide confidence intervals around the estimates could suggest variable impact of the prebiotic. An underlying mechanism for this differential response may be the degree of alteration of the gut microbiome, which correlated with the change in FCA. Prebiotic supplementation, specifically SCF, is a well-tolerated, acceptable, inexpensive, and low-risk strategy that may improve FCA in the post-RYGB population. Further larger-scale and longer-term trials are warranted, focusing particularly on using higher doses of prebiotic and/or a symbiotic regimen to induce a more consistent change in the gut microbiome.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dolores Shoback, MD, for her service as Medical Monitor; Lisa Spence, PhD, RD for her advice; and Sarah Palilla, PA, and Elliazar Enriquez, LVN, for their facilitation of study recruitment.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 1,25(OH)2D

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D

- 25(OH)D

25-hydroxyvitamin D

- ASV

amplicon sequence variant

- BMD

bone mineral density

- BMI

body mass index

- CTx

cross-linked telopeptide

- FCA

fractional calcium absorption

- P1NP

procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide

- PPI

proton pump inhibitor

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- RYGB

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

- SCF

soluble corn fiber

Financial Support

This study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK, R21DK112126). Additional support came from the NIDDK grant P30DK098722, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (P30AR075055), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001872), and the Northern California Institute for Research and Education. K.C.W. has received support from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the NIDDK (T32DK00741837). T.Y.K. is supported by a VA Career Development Award (1IK2CX001984). Manuscript content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Soluble corn fiber and maltodextrin were provided by Tate & Lyle; Tate & Lyle was not involved in study design, data analysis or interpretation, or manuscript writing or approval.

Clinical Trial Information

ClinicalTrials.gov no. NCT03272542 (registered September 5, 2017).

Disclosure Statement

A.L.S. has received investigator-initiated research funding from Amgen. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief 2020;(360):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Global BMI Mortality Collaboration, Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju ShN, Wormser D, et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet. 2016;388(10046):776-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang SH, Stoll CR, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003-2012. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(3):275-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakamura KM, Haglind EG, Clowes JA, et al. Fracture risk following bariatric surgery: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(1):151-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stein EM, Silverberg SJ. Bone loss after bariatric surgery: causes, consequences, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(2):165-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rousseau C, Jean S, Gamache P, et al. Change in fracture risk and fracture pattern after bariatric surgery: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2016;354:i3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yu EW, Lee MP, Landon JE, Lindeman KG, Kim SC. Fracture risk after bariatric surgery: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus adjustable gastric banding. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(6):1229-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Axelsson KF, Werling M, Eliasson B, et al. Fracture risk after gastric bypass surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(12):2122-2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gagnon C, Schafer AL. Bone health after bariatric surgery. JBMR Plus. 2018;2(3):121-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lindeman KG, Greenblatt LB, Rourke C, Bouxsein ML, Finkelstein JS, Yu EW. Longitudinal 5-year evaluation of bone density and microarchitecture after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(11):4104-4112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schafer AL, Kazakia GJ, Vittinghoff E, et al. Effects of gastric bypass surgery on bone mass and microarchitecture occur early and particularly impact postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(6):975-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang Q, Chen Y, Li J, et al. A meta-analysis of the effects of bariatric surgery on fracture risk. Obes Rev. 2018;19(5):728-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paccou J, Martignène N, Lespessailles E, et al. Gastric bypass but not sleeve gastrectomy increases risk of major osteoporotic fracture: French population-based cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35(8):1415-1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schafer AL, Weaver CM, Black DM, et al. Intestinal calcium absorption decreases dramatically after gastric bypass surgery despite optimization of vitamin D status. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(8):1377-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. 2012;489(7415):242-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen YC, Greenbaum J, Shen H, Deng HW. Association between gut microbiota and bone health: potential mechanisms and prospective. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(10):3635-3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hernandez CJ, Guss JD, Luna M, Goldring SR. Links between the microbiome and bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(9):1638-1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang Y, Ren X, Han J. The impact of the intestinal microbiome on bone health. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2018;7(3):148-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weaver CM. Diet, gut microbiome, and bone health. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13(2):125-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weaver CM, Martin BR, Nakatsu CH, et al. Galactooligosaccharides improve mineral absorption and bone properties in growing rats through gut fermentation. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(12):6501-6510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whisner CM, Martin BR, Nakatsu CH, et al. Soluble corn fiber increases calcium absorption associated with shifts in the gut microbiome: a randomized dose-response trial in free-living pubertal females. J Nutr. 2016;146(7):1298-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jakeman SA, Henry CN, Martin BR, et al. Soluble corn fiber increases bone calcium retention in postmenopausal women in a dose-dependent manner: a randomized crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(3):837-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Whisner CM, Martin BR, Nakatsu CH, et al. Soluble maize fibre affects short-term calcium absorption in adolescent boys and girls: a randomised controlled trial using dual stable isotopic tracers. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(3):446-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Whisner CM, Castillo LF. Prebiotics, bone and mineral metabolism. Calcif Tissue Int. 2018;102(4):443-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Costabile A, Bergillos-Meca T, Rasinkangas P, Korpela K, de Vos WM, Gibson GR. Effects of soluble corn fiber alone or in synbiotic combination with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and the pilus-deficient derivative GG-PB12 on fecal microbiota, metabolism, and markers of immune function: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy elderly (Saimes study). Front Immunol. 2017;8:1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stewart ML, Nikhanj SD, Timm DA, Thomas W, Slavin JL. Evaluation of the effect of four fibers on laxation, gastrointestinal tolerance and serum markers in healthy humans. Ann Nutr Metab. 2010;56(2):91-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hacker-Thompson A, Robertson TP, Sellmeyer DE. Validation of two food frequency questionnaires for dietary calcium assessment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(7):1237-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DeGrazia JA, Ivanovich P, Fellows H, Rich C. A double isotope method for measurement of intestinal absorption of calcium in man. J Lab Clin Med. 1965;66(5):822-829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith DL, Atkin C, Westenfelder C. Stable isotopes of calcium as tracers: methodology. Clin Chim Acta. 1985;146(1):97-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weaver CM. Calcium in Human Health. 1 ed. In: Weaver CM, Heaney RP, eds. Humana Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meir R, Beglinger C, Dederding JP, et al. [Age- and sex-specific standard values of colonic transit time in healthy subjects]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1992;122(24):940-943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Whisner CM, Martin BR, Schoterman MH, et al. Galacto-oligosaccharides increase calcium absorption and gut bifidobacteria in young girls: a double-blind cross-over trial. Br J Nutr. 2013;110(7):1292-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. DeAngelis KM, Brodie EL, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Lindow SE, Firestone MK. Selective progressive response of soil microbial community to wild oat roots. ISME J. 2009;3(2):168-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Poncheewin W, Hermes GDA, van Dam JCJ, Koehorst JJ, Smidt H, Schaap PJ. NG-Tax 2.0: a semantic framework for high-throughput amplicon analysis. Front Genet. 2020;10:1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fujimura KE, Sitarik AR, Havstad S, et al. Neonatal gut microbiota associates with childhood multisensitized atopy and T cell differentiation. Nat Med. 2016;22(10):1187-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Block G, Woods M, Potosky A, Clifford C. Validation of a self-administered diet history questionnaire using multiple diet records. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(12):1327-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scherzer R, Shen W, Bacchetti P, et al. ; Study of Fat Redistribution Metabolic Change in HIV Infection . Comparison of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and magnetic resonance imaging-measured adipose tissue depots in HIV-infected and control subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(4):1088-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001;26(1):32-46. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57(1):289-300. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Carrasco F, Basfi-Fer K, Rojas P, et al. Calcium absorption may be affected after either sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in premenopausal women: a 2-y prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(1):24-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Riedt CS, Brolin RE, Sherrell RM, Field MP, Shapses SA. True fractional calcium absorption is decreased after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(11):1940-1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bronner F. Mechanisms of intestinal calcium absorption. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88(2):387-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schafer AL. Vitamin D and intestinal calcium transport after bariatric surgery. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;173:202-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Abegg K, Gehring N, Wagner CA, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery reduces bone mineral density and induces metabolic acidosis in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305(9):R999-R1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. James H, Lorentz P, Collazo-Clavell ML. Patient-reported adherence to empiric vitamin/mineral supplementation and related nutrient deficiencies after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26(11):2661-2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Smelt HJM, Pouwels S, Smulders JF, Hazebroek EJ. Patient adherence to multivitamin supplementation after bariatric surgery: a narrative review. J Nutr Sci. 2020;9:e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Heaney RP, Recker RR. Distribution of calcium absorption in middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986;43(2):299-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mackie RI, Sghir A, Gaskins HR. Developmental microbial ecology of the neonatal gastrointestinal tract. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(5):1035S-1045S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Flint HJ, Scott KP, Louis P, Duncan SH. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9(10):577-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Clarke SF, Murphy EF, O’Sullivan O, et al. Exercise and associated dietary extremes impact on gut microbial diversity. Gut. 2014;63(12):1913-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Monda V, Villano I, Messina A, et al. Exercise modifies the gut microbiota with positive health effects. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:3831972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Singh RK, Chang HW, Yan D, et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tottey W, Feria-Gervasio D, Gaci N, et al. Colonic transit time is a driven force of the gut microbiota composition and metabolism: in vitro evidence. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23(1):124-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ladebo L, Pedersen PV, Pacyk GJ, et al. Gastrointestinal pH, motility patterns, and transit times after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2021;31(6):2632-2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Poulsen JL, Nilsson M, Brock C, Sandberg TH, Krogh K, Drewes AM. The impact of opioid treatment on regional gastrointestinal transit. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22(2):282-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gorard DA, Libby GW, Farthing MJ. Influence of antidepressants on whole gut and orocaecal transit times in health and irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8(2):159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ilhan ZE, DiBaise JK, Isern NG, et al. Distinctive microbiomes and metabolites linked with weight loss after gastric bypass, but not gastric banding. ISME J. 2017;11(9):2047-2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Graessler J, Qin Y, Zhong H, et al. Metagenomic sequencing of the human gut microbiome before and after bariatric surgery in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: correlation with inflammatory and metabolic parameters. Pharmacogenomics J. 2013;13(6):514-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Palleja A, Kashani A, Allin KH, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery of morbidly obese patients induces swift and persistent changes of the individual gut microbiota. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tremaroli V, Karlsson F, Werling M, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and vertical banded gastroplasty induce long-term changes on the human gut microbiome contributing to fat mass regulation. Cell Metab. 2015;22(2):228-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Aron-Wisnewsky J, Prifti E, Belda E, et al. Major microbiota dysbiosis in severe obesity: fate after bariatric surgery. Gut. 2019;68(1):70-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lee CJ, Florea L, Sears CL, et al. Changes in Gut Microbiome after bariatric surgery versus medical weight loss in a pilot randomized trial. Obes Surg. 2019;29(10):3239-3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Aron-Wisnewsky J, Doré J, Clement K. The importance of the gut microbiota after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9(10):590-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Vacca M, Celano G, Calabrese FM, Portincasa P, Gobbetti M, De Angelis M. The controversial role of human gut Lachnospiraceae. Microorganisms. 2020;8(4):573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Biddle A, Stewart L, Blanchard J, Leschine S. Untangling the genetic basis of fibrolytic specialization by Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae in diverse gut communities. Diversity. 2013;5(3):627-640. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Scholz-Ahrens KE, Schrezenmeir J. Inulin, oligofructose and mineral metabolism - experimental data and mechanism. Br J Nutr. 2002;87(Suppl 2):S179-S186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mineo H, Hara H, Tomita F. Short-chain fatty acids enhance diffusional ca transport in the epithelium of the rat cecum and colon. Life Sci. 2001;69(5):517-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Nguyen NQ, Debreceni TL, Bambrick JE, et al. Rapid gastric and intestinal transit is a major determinant of changes in blood glucose, intestinal hormones, glucose absorption and postprandial symptoms after gastric bypass. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(9):2003-2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gerasimidis K, Bryden K, Chen X, et al. The impact of food additives, artificial sweeteners and domestic hygiene products on the human gut microbiome and its fibre fermentation capacity. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59(7):3213-3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Eid N, Enani S, Walton G, et al. The impact of date palm fruits and their component polyphenols, on gut microbial ecology, bacterial metabolites and colon cancer cell proliferation. J Nutr Sci. 2014;3:e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Aloia JF, Mikhail M, Pagan CD, Arunachalam A, Yeh JK, Flaster E. Biochemical and hormonal variables in black and white women matched for age and weight. J Lab Clin Med. 1998;132(5):383-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gutiérrez OM, Isakova T, Smith K, Epstein M, Patel N, Wolf M. Racial differences in postprandial mineral ion handling in health and in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(12):3970-3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Taylor EN, Curhan GC. Differences in 24-hour urine composition between black and white women. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(2):654-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bell NH, Yergey AL, Vieira NE, Oexmann MJ, Shary JR. Demonstration of a difference in urinary calcium, not calcium absorption, in black and white adolescents. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(9):1111-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Finneran S, Rasmussen HM. Calcium absorption responses to calcitriol in black and white premenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(10):3068-3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mersha TB, Abebe T. Self-reported race/ethnicity in the age of genomic research: its potential impact on understanding health disparities. Hum Genomics. 2015;9(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.