Abstract

Few studies have compared knowledge of the specific health risks of cannabis across jurisdictions. This study aimed to examine perceptions of the health risks of cannabis in Canada and US states with and without legal non-medical cannabis. Cross-sectional data were collected from the 2018 and 2019 International Cannabis Policy Study online surveys. Respondents aged 16–65 (n = 72 459) were recruited from Nielsen panels using non-probability methods. Respondents completed questions on nine health effects of cannabis (including two ‘false’ control items). Socio-demographic data were collected. Regression models tested differences in outcomes between jurisdictions and by frequency of cannabis use, adjusting for socio-demographic factors. Across jurisdictions, agreement with statements on the health risks of cannabis was highest for questions on driving after cannabis use (66–80%), use during pregnancy/breastfeeding (61–71%) and addiction (51–62%) and lowest for risk of psychosis and schizophrenia (23–37%). Additionally, 12–18% and 6–7% of respondents agreed with the ‘false’ assertions that cannabis could cure/prevent cancer and cause diabetes, respectively. Health knowledge was highest among Canadian respondents, followed by US states that had legalized non-medical cannabis and lowest in states that had not legalized non-medical cannabis (P < 0.001). Overall, the findings demonstrate a substantial deficit in knowledge of the health risks of cannabis, particularly among frequent consumers.

Introduction

Cannabis use is among the most commonly used substances in the United States and Canada [1, 2]. In addition to potential therapeutic effects, there is substantial evidence that frequent cannabis use can cause health effects, including worsened respiratory symptoms, increased risk of motor vehicle crash, pregnancy complications and lower infant birth weight, impairment to learning, memory and attention and increased risk of schizophrenia and psychosis among frequent consumers [3]. The likelihood of problematic cannabis use and long-term health effects is also associated with early initiation and frequent cannabis use in adolescence [3].

The perceived risk of cannabis among young people is inversely associated with future cannabis use: young people who perceive cannabis as less harmful are more likely to subsequently consume cannabis [4, 5]. Several studies also indicate that cannabis consumers have lower perceptions of risk and addiction than non-consumers [1, 5–10]. Lower perceived risk among consumers may reflect optimism bias, the belief that one’s health risk is lower than that of others [11–13], and an effort to minimize cognitive dissonance, in which consumers alter their health beliefs when it conflicts with their behaviour [14, 15].

US studies indicate decreasing cannabis risk perceptions over time among adolescents and adults [6, 7, 16–19]. The extent to which cannabis legalization has contributed to declining risk perceptions—particularly among young people—represents an important question, for which the evidence is mixed. A school-based study found that perceptions of harm increased among eighth-graders in states with medical cannabis laws [20], whereas another found no difference in perceptions of risk among youth in states without non-medical cannabis markets versus those with new or established markets [21]. In contrast, several other studies have found lower perceptions of risk from cannabis use in jurisdictions that have legalized cannabis [22–24]. However, these trends appear to predate legalization [24] and may reflect pre-existing differences between states that subsequently legalized non-medical cannabis (herein US ‘legal’ states). Overall, the impact of legalization on cannabis risk perceptions remains unclear.

Perceived risk of cannabis use has typically been assessed using a general question about ‘overall’ risk or risk compared to alcohol or other substances [4–8]. General indicators of risk can provide a useful overall measure of risk perception; however, perceptions of overall harm can obscure important deficits in health knowledge and beliefs [25]. For example, beginning in the 1950s, the majority of Americans agreed that smoking was harmful to health, while fewer than 10% could recall cancer as a health effect from smoking and less than half agreed that smoking caused lung cancer [26]. To date, few studies have assessed cannabis health risk using measures that test knowledge of specific health effects [10, 27]. A national Canadian monitoring survey found that most Canadians agreed that cannabis can be harmful to use during pregnancy or breastfeeding (87%), adolescents are at increased risk of harm from cannabis (84%), cannabis smoke is harmful (76%) and cannabis can harm mental health (75%) [27]. Studies also show higher risk perceptions of impaired driving in ‘legal’ versus ‘illegal’ US states [28], lower perceived risk of cannabis-impaired driving among frequent versus infrequent/non-cannabis consumers, as well as lower perceived risk of cannabis compared to alcohol-impaired driving [29, 30]. Knowledge of specific health effects may be particularly important in assessing the impact of public education campaigns and health warning labels, which often target specific outcomes or risks.

Abuse liability and dependence are central factors in substance use, with important implications for risk perceptions [31]. Although the risk of dependence is lower for cannabis than other legal drugs such as nicotine and alcohol, it is estimated that approximately 9% of cannabis consumers will become dependent on cannabis in their lifetime [27, 32]. Frequent cannabis use and higher consumption levels are important indicators of dependence, as well as more general measures of problematic cannabis use [33–35]. In addition, recent research suggests that the risk of dependence may increase with the use of high-potency cannabis, which has increased over time [36, 37].

Consumers may also hold false beliefs about the therapeutic effects of cannabis use. There is evidence for certain therapeutic effects of cannabis, including treating chronic pain, reducing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and multiple sclerosis spasticity [3, 38]. However, increased marketing and social media presence regarding cannabis and cannabidiol (CBD) products have the potential to promote false or exaggerated beliefs about the potential therapeutic use of these products [39]. A US survey found that respondents who considered social media or the internet, the cannabis industry, or family/friends as the most influential source of information about cannabis were most likely to believe misinformation about cannabis [40]. Another study among high-school students found that those who had previously consumed cannabis were more likely than never consumers to believe false assertions about cannabis, including that it cures mental illness [10].

To increase public awareness of specific health risks of cannabis, Canada mandated health warning labels on cannabis packages when non-medical cannabis legalization came into effect on 17 October 2018. The warnings described six different health risks, and were revised in 2019 [41]. Similarly, all US ‘legal’ states have mandated warning labels on cannabis packages, as have some states with legal medical cannabis [42]. Health warning labels vary by state and often summarize multiple health risks in one paragraph.

The current study had two primary objectives. First, the study sought to examine whether knowledge of the health risks of cannabis differed in Canada pre- versus post-legalization, compared to respondents in US ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ states. Second, the study examined potential differences in health knowledge by frequency of cannabis use and socio-demographics. It was hypothesized that due to exposure to mandatory health warnings on cannabis packaging, respondents in Canada would demonstrate greater knowledge of the tested health risks compared to US ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ states. It was further hypothesized that frequent cannabis consumers would be less likely to endorse items relating to the health risks of cannabis, due to a combination of optimistic bias and personal positive experiences using cannabis.

Method

Cross-sectional findings from Waves 1 and 2 of the International Cannabis Policy Study (ICPS), conducted in Canada and the United States, are presented [43]. Data were collected via self-completed web-based surveys conducted in fall 2018 (immediately pre-cannabis legalization in Canada) and fall 2019 (1-year post-legalization). Respondents aged 16–65 were recruited through the Nielsen Consumer Insights Global Panel and their partners’ panels. Email invitations (with a unique link) were sent to a random sample of panellists (after targeting for age and country criteria); panellists known to be ineligible were not invited. Surveys were conducted in English in the United States and in English or French in Canada. Median survey times were 20 and 25 min in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Respondents provided consent prior to completing the survey. Respondents received remuneration in accordance with their panel’s usual incentive structure (e.g. points-based or monetary rewards, chances to win prizes). The study was reviewed by and received ethics clearance through a University of Waterloo Research Ethics Committee (ORE#31330). A full description of the study methods can be found in the ICPS methodology paper [43] and technical reports (http://cannabisproject.ca/methods/).

Measures

Full question wording is available in the ICPS surveys (http://cannabisproject.ca/methods/).

Socio-demographic factors included sex, age group, ethnicity, highest education level and perceived income adequacy (categorical). The suspected device type used to complete the survey was also collected by Nielsen. See Table I for response options.

Table I.

Sample characteristics (n = 72 459)

| Canada | US ‘illegal’ States | US ‘legal’ states | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 (pre-legalization) (n = 9999) | 2019 (post-legalization) (n = 15 134) | 2018 (n = 9682) | 2019 (n = 10 217) | 2018 (n = 7351) | 2019 (n = 20 076) | |||||||

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 50.0% | 4998 | 49.8% | 7540 | 50.4% | 4879 | 50.3% | 5142 | 49.9% | 3665 | 49.9% | 10 012 |

| Male | 50.0% | 5001 | 50.2% | 7594 | 49.6% | 4802 | 49.7% | 5075 | 50.1% | 3686 | 50.1% | 10 064 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 16–25 | 18.9% | 1894 | 18.6% | 2818 | 19.9% | 1932 | 19.9% | 2029 | 19.4% | 1429 | 19.7% | 3952 |

| 26–35 | 20.6% | 2062 | 20.8% | 3153 | 21.4% | 2069 | 21.5% | 2196 | 22.9% | 1679 | 22.6% | 4537 |

| 36–45 | 19.5% | 1948 | 19.8% | 2997 | 18.9% | 1827 | 19.0% | 1943 | 17.4% | 1279 | 19.3% | 3883 |

| 46–55 | 20.9% | 2087 | 20.0% | 3022 | 20.2% | 1954 | 19.8% | 2027 | 21.8% | 1605 | 19.5% | 3911 |

| 56–65 | 20.1% | 2007 | 20.8% | 3143 | 19.6% | 1899 | 19.8% | 2022 | 18.5% | 1360 | 18.9% | 3792 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| White | 77.4% | 7744 | 73.4% | 11 106 | 76.5% | 7402 | 76.2% | 7781 | 76.4% | 5615 | 76.3% | 15 318 |

| Other/Mixed/Unstated | 22.6% | 2256 | 26.6% | 4028 | 23.6% | 2280 | 23.9% | 2437 | 23.6% | 1736 | 23.7% | 4758 |

| Highest education level | ||||||||||||

| Unstated | 0.7% | 73 | 1.0% | 150 | 0.3% | 27 | 0.4% | 36 | 0.4% | 32 | 0.4% | 78 |

| Less than high school | 15.5% | 1546 | 15.4% | 2333 | 15.2% | 1473 | 12.1% | 1235 | 11.8% | 865 | 5.0% | 1015 |

| High school diploma | 26.6% | 2655 | 26.5% | 4017 | 19.4% | 1880 | 22.5% | 2300 | 15.8% | 1164 | 20.2% | 4056 |

| Some college/technical training | 32.4% | 3239 | 32.4% | 4911 | 38.3% | 3712 | 36.4% | 3718 | 42.0% | 3084 | 41.7% | 8380 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 24.9% | 2488 | 24.7% | 3740 | 26.8% | 2591 | 28.7% | 2928 | 30.0% | 2206 | 32.6% | 6550 |

| Income adequacy (difficulty making ends meet) | ||||||||||||

| Unstated | 3.4% | 336 | 3.8% | 568 | 2.0% | 196 | 2.5% | 256 | 2.9% | 216 | 3.1% | 612 |

| Very difficult | 8.2% | 822 | 9.7% | 1461 | 9.3% | 901 | 10.6% | 1084 | 8.9% | 655 | 10.0% | 2017 |

| Difficult | 20.0% | 2002 | 22.2% | 3365 | 22.2% | 2153 | 23.3% | 2376 | 19.5% | 1438 | 22.7% | 4549 |

| Neither easy nor difficult | 36.0% | 3600 | 35.1% | 5305 | 31.5% | 3051 | 33.0% | 3376 | 32.2% | 2370 | 33.2% | 6668 |

| Easy | 21.1% | 2114 | 19.7% | 2984 | 22.0% | 2131 | 19.0% | 1946 | 22.9% | 1682 | 19.9% | 4002 |

| Very easy | 11.3% | 1125 | 9.6% | 1451 | 12.9% | 1249 | 11.5% | 1180 | 13.6% | 996 | 11.1% | 2228 |

| Suspected survey device type | ||||||||||||

| Smartphonea | 0% | 0 | 42.7% | 6478 | 0% | 0 | 51.9% | 5299 | 0% | 0 | 52.8% | 10 593 |

| Tablet | 10.7% | 1071 | 9.5% | 1440 | 7.5% | 730 | 6.2% | 638 | 10.9% | 801 | 5.9% | 1182 |

| Computer | 89.3% | 8929 | 47.8% | 7226 | 92.5% | 8951 | 41.9% | 4280 | 89.1% | 6550 | 41.4% | 8301 |

| Frequency of cannabis use | ||||||||||||

| Never user | 43.5% | 4349 | 38.1% | 5765 | 45.3% | 4384 | 37.7% | 31.9% | 38.6% | 2835 | 30.8% | 6177 |

| Used >12 months ago | 29.1% | 2910 | 26.9% | 4067 | 31.0% | 3000 | 3847 | 3254 | 27.4% | 2016 | 30.4% | 6105 |

| Less than once per month | 31.4% | 862 | 32.4% | 1715 | 29.2% | 672 | 26.6% | 830 | 27.4% | 685 | 25.9% | 2020 |

| 1+ times per month | 17.7% | 485 | 19.8% | 1049 | 22.1% | 507 | 20.0% | 624 | 20.0% | 499 | 16.3% | 1272 |

| 1+ times per week | 18.4% | 505 | 16.0% | 849 | 17.3% | 397 | 15.5% | 482 | 19.4% | 484 | 16.1% | 1252 |

| Daily or almost daily | 32.4% | 889 | 31.9% | 1688 | 31.4% | 721 | 37.9% | 1180 | 33.3% | 833 | 41.7% | 3251 |

Use of smartphones to complete survey was prohibited in 2018 (Wave 1) survey.

Cannabis use frequency was derived from questions on ever, most recent and current frequency of cannabis use. Consumers were then classified in to the following exclusive categories: Never user; Used more than 12 months ago; Past 12 months (but not more recent) user; Monthly user; Weekly user; or Daily/almost daily user.

Knowledge of the health risks of cannabis was assessed using measures of agreement with a list of health effects, for which respondents could select ‘Yes’, ‘Maybe’, ‘No’ or ‘Don’t know’. A total of seven health effects were assessed, with two additional items added in the 2019 survey (see Table II). Two ‘false’ effects were included for which there is no clear evidence: ‘Can using marijuana cause diabetes?’ (2018 and 2019 surveys) and ‘Can marijuana or CBD help cure or prevent cancer?’ (2019 survey only). An index was created by summing the number of correct responses across the seven items included in both years (range 0–7); the two items added in 2019 were excluded from the index score for consistency. Responses to ‘true’ health statements were coded as ‘Correct’ if respondents selected ‘Yes’; responses to ‘false’ statements were coded as ‘Correct’ if respondents selected ‘No’. Health statements were selected based on those featured in the health warnings mandated to appear on legal non-medical cannabis products in Canada [41, 44].

Table II.

Mean number and frequency of correct responses to cannabis health risk questions by time, jurisdiction and frequency of cannabis use (n = 72 459)

| Canada | US ‘illegal’ states | US ‘legal’ states | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 (pre-legalization) | 2019 (post-legalization) | 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | ||

| Mean (SD) number correct (range = 0–7)a | 4.1 (1.9) | 4.0 (2.0) | 3.4 (1.9) | 3.2 (1.9) | 3.5 (1.9) | 3.4 (1.9) | |

| Prevalence of correct responses % (n) | |||||||

| 1. Can it be dangerous to drive or operate machinery after using marijuana? | 81.1% (8104) | 79.1% (11 951) | 68.4% (6618) | 64.2% (6540) | 73.3% (5387) | 70.3% (14 105) | |

| Never user | 85.4% (3712) | 82.4% (4746) | 76.3% (3341) | 71.9% (2757) | 79.2% (2244) | 76.1% (4693) | |

| Used >12 months ago | 86.8% (2524) | 86.1% (3498) | 72.0% (2157) | 69.8% (2269) | 80.0% (1609) | 78.5% (4786) | |

| Past 12 months userb | 74.0% (1364) | 75.5% (2725) | 55.2% (869) | 54.9% (1063) | 67.0% (1116) | 67.2% (3049) | |

| Daily/almost daily user | 56.6% (504) | 58.2% (983) | 34.9% (252) | 38.4% (451) | 50.2% (418) | 48.5% (1576) | |

| 2. Can it be harmful to use marijuana when pregnant or breastfeeding? | 72.8% (7275) | 70.4% (10 646) | 64.0% (6191) | 58.9% (6009) | 63.4% (4654) | 59.7% (11 964) | |

| Never user | 77.6% (3372) | 75.3% (4338) | 71.9% (3148) | 69.2% (2658) | 72.9% (2059) | 68.5% (4232) | |

| Used >12 months ago | 77.4% (2251) | 76.1% (3092) | 65.6% (1969) | 62.8% (2043) | 63.9% (1289) | 66.6% (4059) | |

| Past 12 months user | 65.7% (1216) | 64.2% (2315) | 51.8% (815) | 48.1% (932) | 57.8% (964) | 52.0% (2358) | |

| Daily/almost daily user | 49.3% (436) | 53.5% (901) | 36.0% (259) | 32.0% (376) | 41.0% (341) | 40.6% (1316) | |

| 3. Can marijuana be addictive? | 62.5% (6242) | 61.6% (9297) | 51.4% (4975) | 49.6% (5065) | 52.3% (3839) | 49.9% (10 003) | |

| Never user | 72.9% (3170) | 70.8% (4081) | 64.6% (2826) | 62.3% (2392) | 66.1% (1870) | 63.4% (3906) | |

| Used >12 months ago | 65.0% (1891) | 66.1% (2683) | 46.8% (1402) | 49.4% (1608) | 53.8% (1085) | 54.7% (3332) | |

| Past 12 months user | 48.0% (886) | 49.9% (1799) | 35.6% (560) | 35.6% (690) | 37.0% (617) | 38.2% (1731) | |

| Daily/almost daily user | 33.2% (295) | 43.9% (734) | 25.9% (187) | 31.9% (375) | 32.0% (266) | 31.8% (1034) | |

| 4. Are teenagers at greater risk of harm from using marijuana than adults? | 59.9% (5986) | 59.7% (9025) | 42.4% (4105) | 42.2% (4300) | 48.3% (3541) | 49.2% (9863) | |

| Never user | 66.2% (2878) | 64.6% (3717) | 49.1% (2152) | 48.5% (1857) | 56.9% (1606) | 56.8% (3504) | |

| Used >12 months ago | 60.7% (1765) | 62.2% (2525) | 41.4% (1239) | 46.0% (1495) | 48.7% (981) | 52.4% (3189) | |

| Past 12 months user | 50.9% (940) | 54.0% (1949) | 34.3% (539) | 32.0% (620) | 40.5% (675) | 43.6% (1980) | |

| Daily/almost daily user | 45.3% (403) | 49.6% (834) | 24.3% (175) | 27.9% (327) | 33.5% (279) | 36.7% (1190) | |

| 5. Can marijuana smoke be harmful? | 58.1% (5804) | 56.2% (8500) | 46.8% (4525) | 41.1% (4189) | 49.6% (3637) | 44.3% (8883) | |

| Never user | 66.9% (2911) | 64.5% (3716) | 57.7% (2530) | 53.8% (2064) | 61.2% (1732) | 57.7% (3563) | |

| Used >12 months ago | 61.3% (1781) | 60.8% (2474) | 46.0% (1379) | 42.5% (1382) | 52.0% (1044) | 49.2% (2995) | |

| Past 12 months user | 44.1% (814) | 47.4% (1711) | 29.4% (460) | 27.0% (523) | 37.0% (615) | 34.0% (1545) | |

| Daily/almost daily user | 33.4% (297) | 35.5% (599) | 21.7% (156) | 18.7% (220) | 29.5% (245) | 24.1% (782) | |

| 6. Can regular use of marijuana increase the risk of psychosis and schizophrenia? | 38.0% (3798) | 36.7% (5550) | 24.8% (2395) | 22.3% (2272) | 26.4% (1936) | 21.5% (4311) | |

| Never user | 47.9% (2081) | 44.3% (2552) | 34.9% (1530) | 30.7% (1178) | 39.3% (1110) | 30.8% (1898) | |

| Used >12 months ago | 37.1% (1079) | 38.5% (1565) | 19.0% (569) | 20.6% (669) | 23.8% (478) | 21.9% (1333) | |

| Past 12 months user | 27.0% (499) | 29.9% (1076) | 14.9% (235) | 13.8% (267) | 15.2% (254) | 15.2% (690) | |

| Daily/almost daily user | 15.7% (139) | 21.2% (357) | 8.5% (61) | 13.3% (157) | 11.4% (95) | 12.0% (390) | |

| 7. Can using marijuana cause diabetes?c | 36.1% (3608) | 38.4% (5806) | 39.9% (3863) | 45.2% (4609) | 38.3% (2805) | 44.6% (8937) | |

| Never user | 24.8% (1080) | 26.2% (1509) | 26.2% (1147) | 29.0% (1112) | 23.3% (657) | 29.0% (1787) | |

| Used >12 months ago | 35.0% (1016) | 38.9% (1580) | 45.3% (1358) | 49.3% (1602) | 39.2% (788) | 42.5% (2583) | |

| Past 12 months user | 49.7% (918) | 47.9% (1726) | 55.7% (876) | 57.3% (1107) | 47.1% (785) | 54.2% (2458) | |

| Daily/almost daily user | 66.9% (594) | 58.9% (991) | 66.8% (481) | 67.0% (788) | 69.7% (575) | 65.0% (2110) | |

| 8. Can high-THC marijuana products negatively affect memory and concentration? (not included in index) | n/a | 53.9% (8148) | n/a | 43.6% (4449) | n/a | 44.6% (8930) | |

| Never user | – | 60.2% (3469) | – | 51.0% (1958) | – | 52.6% (3242) | |

| Used >12 months ago | – | 58.6% (2379) | – | 47.7% (1549) | – | 50.6% (3084) | |

| Past 12 months user | – | 46.1% (1663) | – | 33.1% (640) | – | 37.4% (1698) | |

| Daily/almost daily user | 37.9% (638) | 25.8% (303) | 27.9% (906) | ||||

| 9. Can marijuana or CBD help cure or prevent cancer?c (not included in index) | n/a | 33.6% (5082) | n/a | 26.8% (2737) | n/a | 28.5% (5702) | |

| Never user | – | 37.5% (2161) | – | 28.8% (1106) | – | 33.2% (2047) | |

| Used >12 months ago | – | 37.3% (1516) | – | 29.4% (955) | – | 32.0% (1952) | |

| Past 12 months user | – | 30.4% (1094) | – | 23.2% (448) | – | 25.7% (1164) | |

| Daily/almost daily user | 18.5% (310) | 19.4% (228) | 16.7% (540) | ||||

Items 1–7 were summed to calculate mean score (items 8–9 were added in 2019 and therefore not included in knowledge score).

In all models, past 12 months consumers include less than once per month, monthly and weekly consumers.

Correct response to all items was ‘Yes’ (incorrect = No/Maybe/Don’t know) with the exception of the items on diabetes and curing/preventing cancer (Correct =‘No’; Incorrect = Yes/Maybe/Don’t know).

Noticing health warning messages was assessed using the question ‘In the past 12 months, have you seen health warnings on marijuana products or packages?’ (Yes, No, Not applicable—I have not seen any marijuana products or packages, Don’t know, Refuse). These questions were asked later in the survey in order to discourage respondents from drawing associations with health risks questions.

Data analysis

The final 2018 and 2019 repeat cross-sectional samples comprised 27 169 and 45 735 respondents, respectively. The current analysis comprised a sub-sample of 72 459 after excluding respondents who refused the question on noticing cannabis health warning labels and all health risks questions. Post-stratification sample weights based on sex, age, region, education, race and smoking status (in 2019) were constructed based on the Canadian and US Census estimates and a raking algorithm applied to the original samples; see the Technical Reports for details (http://cannabisproject.ca/methods/). Weights were rescaled to the sample size for Canada and US ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ states. Estimates are weighted.

Linear regression was used to test for differences between jurisdictions and frequency of cannabis use in knowledge of the health risks of cannabis asked in both survey years (range = 0–7; higher scores indicate more correct responses), adjusted for survey year, noticing health warnings, age, sex, education, ethnicity, income adequacy and device type. A sensitivity analysis indicated that a secondary model among past 12 months cannabis consumers only had the same general pattern of significance as the main model, except that the main effect of survey year and survey device became non-significant (data not shown).

Nine binary logistic models were used to test for differences in the odds of correctly responding to each health risk question (1 = Correct; 0 = Incorrect, including Maybe/Don’t know) by jurisdiction and frequency of cannabis use (recoded for models as: Never user; Used >12 months ago; Past 12 months user [including less than once per month, monthly and weekly consumers]; and Daily/almost daily user), adjusted for the same covariates as above. Two-way interactions between jurisdiction and survey year were tested in subsequent models. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals are shown. Analyses were conducted using survey procedures in SAS 9.4.

Results

Sample characteristics are shown in Table I. Approximately half of respondents were female, and the majority had at least some college or university education.

Knowledge of specific health risks

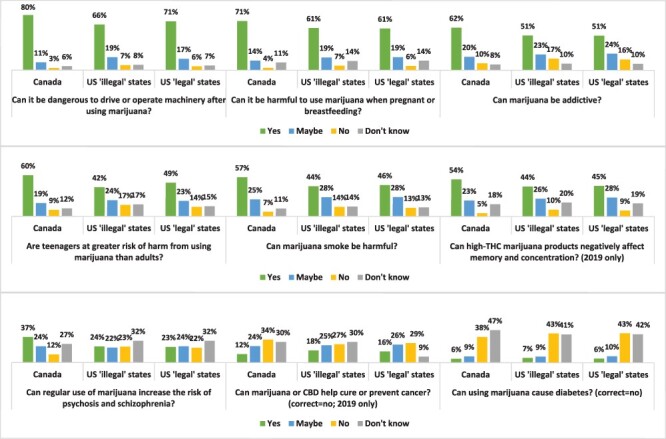

Figure 1 shows the frequency of responses to each health risk question in the two survey years combined. Table II shows the prevalence of correct responses to each health risk question by survey year, jurisdiction and frequency of cannabis use. Across jurisdictions, the highest prevalence of correct responses was observed for driving or operating machinery after cannabis use (66–80%), use during pregnancy/breastfeeding (61–71%) and risk of addiction (51–62%). Approximately half of the respondents (44–54%) agreed that high-THC products could affect memory and concentration. Of the ‘true’ items, the agreement was lowest for risk of developing schizophrenia and psychosis with regular use (23–37%). Of the two ‘false’ items, the agreement was higher for the question on curing/preventing cancer (12–18%) than causing diabetes (6–7%).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of responses to questions on the health risks of cannabis by jurisdiction, 2018 and 2019 data (n = 72 459).

Knowledge index

Table II shows the mean number of correct responses to the seven questions included in both survey waves, and Table III shows the results of the linear regression model. Scores on the knowledge index were significantly higher among respondents in Canada versus US jurisdictions, as well as respondents in US ‘legal’ versus ‘illegal’ states (Table III). Knowledge scores were significantly higher in 2018 compared to 2019. Scores on the knowledge index were significantly higher among those who never consumed cannabis or consumed cannabis less recently compared to daily/almost daily consumers, as well as those who reported noticing health warning labels versus those who did not. There were significant main effects of all socio-demographic covariates. Briefly, knowledge scores were higher among the following groups: 16–25-year-olds versus 26–35 and 36–45-year-olds; females versus males; White versus other/mixed/unstated ethnicity; all education levels versus unstated education and all levels of income adequacy versus unstated. There was no interaction between survey year and jurisdiction in the subsequent model (P = 0.469).

Table III.

Main effects model regressing jurisdiction, cannabis use status and socio-demographic variables on health knowledge index a (n = 72 459)

| Characteristic | Beta (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | F(272 588) = 713.00 | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘legal’ states | 0.61 (0.56, 0.66) | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘illegal’ states | 0.81 (0.76, 0.85) | <0.001 |

| US ‘legal’ states versus US ‘illegal’ states | 0.20 (0.15, 0.24) | <0.001 |

| Survey year | F(172 588) = 14.06 | <0.001 |

| 2018 | —ref— | —ref— |

| 2019 | −0.09 (−0.14, −0.04) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of cannabis use | F(372 588) = 745.71 | <0.001 |

| Daily or almost daily user | —ref— | —ref— |

| Past 12 months user | 0.45 (0.39, 0.52) | <0.001 |

| Used >12 months ago | 1.07 (1.00, 1.13) | <0.001 |

| Never user | 1.32 (1.25, 1.38) | <0.001 |

| Noticing health warnings | F(172 588) = 212.67 | <0.001 |

| No | —ref— | —ref— |

| Yes | 0.44 (0.38, 0.50) | <0.001 |

| Sex | F(172 588) = 92.11 | <0.001 |

| Female | —ref— | —ref— |

| Male | −0.18 (−0.22, −0.14) | <0.001 |

| Age | F(472 588) = 56.62 | <0.001 |

| 16–25 | —ref— | —ref— |

| 26–35 | −0.35 (−0.42, −0.29) | <0.001 |

| 36–45 | −0.18 (−0.25, −0.12) | <0.001 |

| 46–55 | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.12) | 0.132 |

| 56–65 | −0.03 (−0.09, 0.03) | 0.391 |

| Ethnicity | F(172 588) = 39.82 | <0.001 |

| White | —ref— | —ref— |

| Other/Mixed/Unstated | −0.15 (−0.20, −0.10) | <0.001 |

| Highest education level | F(472 588) = 55.27 | <0.001 |

| Unstated | —ref— | —ref— |

| Less than high school | 0.72 (0.39, 1.05) | <0.001 |

| High school diploma | 0.57 (0.25, 0.90) | <0.001 |

| Some college/technical training | 0.78 (0.46, 1.11) | <0.001 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 0.96 (0.63, 1.28) | <0.001 |

| Income adequacy (difficulty making ends meet) | F(572 588) = 44.15 | <0.001 |

| Unstated | —ref— | —ref— |

| Very difficult | 0.81 (0.66, 0.95) | <0.001 |

| Difficult | 0.87 (0.73, 1.00) | <0.001 |

| Neither easy nor difficult | 0.72 (0.58, 0.86) | <0.001 |

| Easy | 0.92 (0.78, 1.06) | <0.001 |

| Very easy | 0.89 (0.75, 1.04) | <0.001 |

| Suspected survey device type | F(272 588) = 7.81 | <0.001 |

| Computer | —ref— | —ref— |

| Smartphone | 0.09 (0.05, 0.14) | <0.001 |

| Tablet | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.12) | 0.145 |

Items were summed to calculate index score (the two items added in 2019 were excluded).

Finally, sensitivity analyses in the form of separate binary regression models were conducted for each health effect. This revealed a similar pattern of results in terms of the effect of jurisdiction and frequency of cannabis use. As shown in Table IV, those living in Canada were significantly more likely to respond correctly than those in both US ‘illegal’ and ‘legal’ states for all except the ‘false’ diabetes item, as were those in US ‘legal’ states compared to ‘illegal’ states (with the exception of the item on psychosis/schizophrenia).

Table IV.

Odds of responding correctly to each cannabis health risk question, by jurisdiction and frequency of cannabis use (72 459)

| Health risk | AOR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Can it be dangerous to drive or operate machinery after using marijuana? (n = 72 515) | ||

| Jurisdiction | F(272 513) = 412.84 | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘illegal’ states | 2.33 (2.20, 2.47) | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘legal’ states | 1.62 (1.53, 1.72) | <0.001 |

| US ‘legal’ versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.44 (1.36, 1.52) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of cannabis use | F(372 512) = 503.72 | <0.001 |

| Never user | 3.90 (3.62, 4.22) | <0.001 |

| Used >12 months ago | 3.76 (3.48, 4.06) | <0.001 |

| Past 12 months user | 2.07 (1.91, 2.23) | <0.001 |

| Daily/almost daily user (ref) | —ref— | —ref— |

| 2. Can it be harmful to use marijuana when pregnant or breastfeeding? (n = 72 516) | ||

| Jurisdiction | F(2, 72 514) = 235.57 | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.70 (1.62, 1.79) | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘legal’ states | 1.57 (1.49, 166) | <0.001 |

| US ‘legal’ versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.08 (1.03, 1.14) | 0.003 |

| Frequency of cannabis use | F(372 513) = 470.11 | <0.001 |

| Never user | 3.55 (3.29, 3.82) | <0.001 |

| Used >12 months ago | 2.90 (2.69, 3.12) | <0.001 |

| Past 12 months user | 1.73 (1.61, 1.87) | <0.001 |

| Daily/almost daily user (ref) | —ref— | —ref— |

| 3. Can marijuana be addictive? (n = 72 522) | ||

| Jurisdiction | F(2, 72 520) = 271.00 | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.73 (1.64, 1.81) | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘legal’ states | 1.55 (1.48, 1.63) | <0.001 |

| US ‘legal’ versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.11 (1.06, 1.17) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of cannabis use | F(2, 72 519) = 731.44 | <0.001 |

| Never user | 4.22 (3.91, 4.55) | <0.001 |

| Used >12 months ago | 2.72 (2.53, 2.93) | <0.001 |

| Past 12 months user | 1.39 (1.29, 1.51) | <0.001 |

| Daily/almost daily user (ref) | —ref— | —ref— |

| 4. Are teenagers at greater risk of harm from using marijuana than adults? (n = 72 508) | ||

| Jurisdiction | F(272 506) = 509.60 | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘illegal’ states | 2.17 (2.07, 2.28) | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘legal’ states | 1.64 (1.56, 1.72) | <0.001 |

| US ‘legal’ versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.32 (1.26, 1.39) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of cannabis use | F(372 505) = 268.13 | <0.001 |

| Never user | 2.41 (2.24, 2.60) | <0.001 |

| Used >12 months ago | 1.91 (1.77, 2.05) | <0.001 |

| Past 12 months user | 1.29 (1.20, 1.40) | <0.001 |

| Daily/almost daily user (ref) | —ref— | —ref— |

| 5. Can marijuana smoke be harmful? (n = 72 524) | ||

| Jurisdiction | F(272 522) = 353.55 | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.89 (1.80, 1.99) | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘legal’ states | 1.58 (1.50, 1.66) | <0.001 |

| US ‘legal’ versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.20 (1.14, 1.26) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of cannabis use | F(342 521) = 650.53 | <0.001 |

| Never user | 4.26 (3.93, 4.61) | <0.001 |

| Used >12 months ago | 2.92 (2.70, 3.16) | <0.001 |

| Past 12 months user | 1.56 (1.43, 1.69) | <0.001 |

| Daily/almost daily user (ref) | —ref— | —ref— |

| 6. Can regular use of marijuana increase the risk of psychosis and schizophrenia? (n = 72 495) | ||

| Jurisdiction | F(272 493) = 497.15 | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘illegal’ states | 2.09 (1.98, 2.20) | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘legal’ states | 2.02 (1.91, 2.13) | <0.001 |

| US ‘legal’ versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.03 (0.97, 1.10) | 0.301 |

| Frequency of cannabis use | F(372 492) = 467.45 | <0.001 |

| Never user | 4.14 (3.75, 4.57) | <0.001 |

| Used >12 months ago | 2.53 (2.29, 2.80) | <0.001 |

| Past 12 months user | 1.51 (1.36, 1.67) | <0.001 |

| Daily/almost daily user (ref) | —ref— | —ref— |

| 7. Can using marijuana cause diabetes? (n = 72 487) | ||

| Jurisdiction | F(272 485) = 47.29 | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘illegal’ states | 0.78 (0.74, 0.82) | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘legal’ states | 0.89 (0.85, 0.94) | <0.001 |

| US ‘legal’ versus US ‘illegal’ states | 0.88 (0.84, 0.93) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of cannabis use | F(372 484) = 797.57 | <0.001 |

| Never user | 0.20 (0.18, 0.21) | <0.001 |

| Used >12 months ago | 0.38 (0.35, 0.41) | <0.001 |

| Past 12 months user | 0.58 (0.54, 0.63) | <0.001 |

| Daily/almost daily user (ref) | —ref— | —ref— |

| 8. Can high-THC marijuana products negatively affect memory and concentration? (n = 45 440) | ||

| Jurisdiction | F(245 438) = 140.66 | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.59 (1.50, 1.69) | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘legal’ states | 1.48 (1.40, 1.56) | 0.018 |

| US ‘legal’ versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.08 (1.01, 1.14) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of cannabis use | F(345 437) = 281.79 | <0.001 |

| Never user | 2.89 (2.65, 3.15) | <0.001 |

| Used >12 months ago | 2.57 (2.35, 2.79) | <0.001 |

| Past 12 months user | 1.47 (1.34, 1.60) | <0.001 |

| Daily/almost daily user (ref) | —ref— | —ref— |

| 9. Can marijuana or CBD help cure or prevent cancer? (n = 45 437) | ||

| Jurisdiction | F(245 435) = 70.55 | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.46 (1.37, 1.56) | <0.001 |

| Canada versus US ‘legal’ states | 1.29 (1.22, 1.37) | <0.001 |

| US ‘legal’ versus US ‘illegal’ states | 1.13 (1.06, 1.21) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of cannabis use | F(345 434) = 68.30 | <0.001 |

| Never user | 1.96 (1.78, 2.16) | <0.001 |

| Used >12 months ago | 1.84 (1.67, 2.03) | <0.001 |

| Past 12 months user | 1.52 (1.37, 1.68) | <0.001 |

| Daily/almost daily user (ref) | —ref— | —ref— |

Models were adjusted for age group, sex, education, ethnicity, income adequacy, device type, noticing of health warnings and survey year (except for items 8 and 9, which were asked only in 2019). Sample sizes vary between health risk questions because models exclude those who selected ‘Refuse to answer’. F-test refers to type III analysis of fixed effects.

Discussion

Results of the current study suggest varying levels of knowledge of the various health risks of cannabis. With the exception of the risk of psychosis and schizophrenia, approximately half or more respondents agreed which each ‘true’ health risk, with the highest level of agreement observed among Canadian respondents for the item on driving after cannabis use (81%). In the United States, agreement with the risk of driving impaired was lower, at approximately two-thirds to 70%. Agreement with this item decreased with the frequency of cannabis consumption; across jurisdictions, approximately one-third to one-half of daily cannabis consumers recognized the dangers of cannabis-impaired driving. This is problematic given that motor vehicle crashes are a leading cause of mortality attributable to cannabis [3, 45]. Cannabis use is also known to worsen respiratory symptoms [3], yet agreement with the harms of cannabis smoke was even lower, with only one-fifth to one-third of daily consumers and approximately half of the general population in each jurisdiction endorsing this item.

The agreement was notably lower overall for the risk of psychosis and schizophrenia, at approximately 22–38% of the general population, and only 9–22% of daily cannabis consumers. A 2017 survey found higher agreement among Canadian young adults, with 49% believing that people had a moderate or great risk of ‘harming their mental health’ with regular cannabis use [9]. This lower agreement is perhaps unsurprising given that psychosis and schizophrenia suggest greater disease severity compared to ‘harming mental health’. Indeed, when a national Canadian survey asked whether frequent cannabis can ‘increase the risk of mental health problems’, 75% of all respondents and 65% of past 12-month cannabis consumers agreed—much higher than the agreement observed among Canadians in the current study [27]. Lower awareness of the risk of schizophrenia and psychosis from cannabis use also may reflect the lower prevalence of these conditions in the general population relative to other health effects. Therefore, even meaningful increases in risk may not be apparent or particularly salient to the general population, including cannabis consumers with no experience with schizophrenia or psychosis.

It is also concerning that the proportion of correct responses to the psychosis and schizophrenia item was lower than the item on diabetes, with approximately one-third to one-half of respondents across jurisdictions correctly recognizing this item as false. (Interestingly, non-consumers were more likely than consumers to incorrectly believe that cannabis use can cause diabetes, which suggests a non-specific effect towards greater agreement in general). Although many cannabis consumers self-report using cannabis for mental health concerns [46], there is continued evidence that regular consumers are at heightened risk of psychiatric disorders [47]. Enhanced public health messaging regarding this health risk of cannabis is needed.

Overall, agreement with the health effects of cannabis was somewhat lower than a Canadian national survey, possibly due to lower social desirability bias associated with online versus in-person or telephone-based surveys [47, 48]. However, the ordering of perceived risk of health effects was the same, with a higher agreement for the item on pregnancy and breastfeeding, followed by harm to adolescents and harms of cannabis smoke [27].

In addition, a non-negligible proportion of respondents (12–18%) responded ‘yes’ to whether cannabis can prevent or cure cancer, suggesting that a reasonable number of people believe this to be true. Cannabis has demonstrated therapeutic effects, including as an anti-emetic that is commonly used to address the side effects of chemotherapy. However, there is insufficient evidence to date suggesting that it can cure or prevent cancer, and the research regarding its anti-tumour activity is in its infancy [3, 38]. The findings suggest that false beliefs about the medical benefits of cannabis are common and reflect widespread marketing of cannabis and CBD as natural health products, often based on dubious or incorrect claims [48]. Future research should examine potentially false beliefs about the health benefits of cannabis use, particularly if cannabis use supplants effective health care practices.

Across jurisdictions, agreement with health effects was generally highest in Canada, followed by US jurisdictions. Levels of agreement were moderately higher in US states that had legalized recreational cannabis compared to states that had not; however, the magnitude of difference was modest. Given that higher health knowledge was associated with noticing health warnings, the mandated warnings on cannabis products in ‘legal’ states are one potential explanation for the higher levels of health knowledge compared to ‘illegal’ states. Undoubtedly, some consumers in US ‘illegal’ states would have seen legal cannabis products with health warnings out of state, and some US ‘illegal’ states mandate health warnings on medical cannabis [42]. However, the reach of medical warnings would be lower compared to those on legal recreational cannabis products, which are designed to communicate risks to the general population. Overall, findings do not suggest lower levels of the perceived risk of cannabis in US states that had legalized compared to those that had not, as per some previous studies [22–24]. This contrasting finding may be attributable to several factors, including that this was a general population rather than a school-based survey [22, 24].

There are several possible explanations for the higher level of health knowledge in Canada versus the United States. First, US jurisdictions had greater proportions of daily/almost daily cannabis consumers in 2019 compared to Canada (see Table I). Given that frequent consumers had lower risk perceptions overall, the different distribution of cannabis consumers may have been partially responsible for the lower risk perceptions observed in the United States. Second, survey questions were designed to test knowledge of the risks listed on mandated Canadian warning labels, and may therefore have been more familiar to Canadians [44]. This is consistent with the finding that noticing warnings were associated with greater health knowledge, as is the case for other consumer products, such as tobacco. In addition, previous experimental research demonstrated that the design of the Canadian warnings produces greater recall than the mandated warnings in US ‘legal’ states [49]. However, if the Canadian warnings were responsible for the higher levels of knowledge compared to the United States, one would expect greater knowledge post-legalization, after the warnings began appearing on products. This was not the case: levels of knowledge in Canada were modestly higher before legalization in 2018 compared to 2019. Lower overall levels of health knowledge in 2019 were largely driven by non-consumers, who account for a much greater proportion of the population than consumers; in contrast, levels of knowledge among daily/almost daily consumers in Canada increased between 2018 and 2019. Given that consumers are far more likely than non-consumers to be exposed to packaged-based warnings, this pattern of findings could be consistent with an effect of the new warnings. Nevertheless, a more plausible explanation for the higher levels of health knowledge in Canada compared to the United States in both 2018 and 2019 may be the public education campaigns implemented in Canada during the lead-up to legalization. In the year prior to legalization, several national mass media campaigns were conducted, along with extensive news coverage and discussion of the health effects of cannabis [50, 51]. These public education initiatives may account for both the higher levels of perceived risk in Canada versus the United States, as well as the moderately higher knowledge levels in 2018 and 2019 among Canadian respondents. Further research will be needed to examine the potential impact of health warnings on population-level health knowledge. This research will need to account for the complex association between frequency of use, exposure to product warnings and pre-existing differences between consumers and non-consumers. Future studies should also account for the gradual transition from illegal to legal retail sources, which directly affects exposure to mandated warnings. Shortly after legalization in Canada, exposure to warnings would have been attenuated by continuing use of products from illicit sources, none of which would display mandated warnings [52]. Legalization in Canada occurred in two phases, and product types other than dried herb and some oils did not become available for legal sale in Canada until 2020 [53]. Therefore, most consumers would still have been accessing the illegal market with little exposure to health warnings in the first year or two following legalization [54].

Finally, findings suggest individual-level differences in cannabis risk perceptions. Notably, higher risk perceptions were found among infrequent or never cannabis consumers, and lower risk perceptions were found among frequent consumers. This is consistent with hypotheses, research on optimistic bias [11–13] and previous studies showing lower risk perceptions—including lower risk of addiction—among those who have consumed cannabis compared to those who have not consumed cannabis [1, 5–9, 27]. This is also consistent with the concept of cognitive dissonance: frequent consumers may avoid regret over their cannabis use by adjusting their belief system (i.e. downplaying cannabis health risks). This phenomenon has been demonstrated in studies among tobacco smokers [15]. Future studies are needed to determine whether there are consistent socio-demographic differences in knowledge of cannabis-related health effects and whether they are different than for tobacco.

Limitations

This study is subject to limitations common to survey research. Respondents were recruited using non-probability-based sampling; therefore, the findings do not provide nationally representative estimates. The data were weighted by age group, sex, region, education and smoking status in both countries and region-by-race in the United States. However, compared to the national population, the US sample had fewer respondents with low education levels and Hispanic ethnicity. Cannabis use estimates were within the range of national estimates for young adults, whereas estimates among the full ICPS sample were generally higher than national surveys in the United States and Canada. This is likely due to the fact that the ICPS-sampled individuals aged 16–65, whereas the national surveys included older adults, who are known to have lower rates of cannabis use. In both countries, the ICPS sample also had poorer self-reported general health compared to the national population, which is a feature of many non-probability samples [55], and may be partly due to the use of web surveys, which provide greater perceived anonymity than in-person or telephone-assisted interviews often used in national surveys [56]. In addition, health risk questions were designed to test the risks listed on Canadian warning labels. Although many of these concepts are communicated by the mandatory labels in US ‘legal’ states [42], the labels use different wordings, and any supplementary information included on US warnings was not tested. Additionally, the measures of health knowledge used agreement questions and conditional causal wording such as ‘can’ when asking about health effects; both practices lead to higher estimates of health knowledge compared to open-ended or unprompted measures and statements featuring more definite causal wording such as ‘causes’ [57]. Finally, the index was not previously validated as a measure of cannabis health knowledge. However, sensitivity analyses indicated a similar pattern of findings with respect to jurisdiction and cannabis use frequency when each risk item was modelled separately as opposed to as a linear measure (Table IV).

Conclusions

The current study suggests that population-level knowledge of the health effects of cannabis is relatively low, especially for specific health effects related to mental health. Frequent cannabis consumers had lower perceptions of the risks of cannabis use compared to infrequent consumers, likely due to optimistic bias and the desire to diminish cognitive dissonance. Given that more frequent consumption is associated with higher levels of risk to physical and mental health [3, 47], frequent consumers may benefit from education campaigns aiming to increase knowledge of the health risks of cannabis. As more consumers transition to the legal market in Canada and US ‘legal’ states, regular consumers will be frequently exposed to mandatory warning labels. Further research is required to determine whether this exposure increases knowledge of the health risks of cannabis in the same manner as has been established for tobacco products. Higher perceptions of health risk were also observed among respondents in Canada compared to those in US jurisdictions, which is consistent with increasing and decreasing risk perceptions of cannabis in Canada and the United States, respectively. US state health authorities should consider these findings when designing educational campaigns and health warning labels.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Christian Boudreau, Vicki Rynard and Robin Burkhalter for their help in creating the weights for the ICPS.

Contributor Information

Samantha Goodman, School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, 200 University Ave West, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada.

David Hammond, School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, 200 University Ave West, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada.

Funding

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Project Bridge Grant (PJT-153342); CIHR Project Grant; Public Health Agency of Canada-CIHR Chair in Applied Public Health; Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction through the Partnerships for Cannabis Policy Evaluation Team Grant administered by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Government of Canada . Canadian Cannabis Survey 2019 - Summary. 2019. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/drugs-health-products/canadian-cannabis-survey-2019-summary.html. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). 2019. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 3. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine . The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. 2017. Available at: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24625/the-health-effects-of-cannabis-and-cannabinoids-the-current-state. Accessed: 15 March 2022. [PubMed]

- 4. Parker MA, Anthony JC. A prospective study of newly incident cannabis use and cannabis risk perceptions: results from the United States Monitoring the Future study, 1976–2013. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018; 187: 351–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Salloum NC, Krauss MJ, Agrawal A et al. A reciprocal effects analysis of cannabis use and perceptions of risk. Addiction 2018; 113: 1077–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pacek LR, Mauro PM, Martins SS. Perceived risk of regular cannabis use in the United States from 2002 to 2012: differences by sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015; 149: 232–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM. Prevalence and attitudes regarding marijuana use among adolescents over the past decade. Pediatrics 2017; 140: e20170982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Spackman E, Haines-Saah R, Danthurebandara VM et al. Marijuana use and perceptions of risk and harm: a survey among Canadians in 2016. Healthc Policy 2017; 13: 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leos-Toro C, Fong G, Meyer S et al. Cannabis health knowledge and risk perceptions among Canadian youth and young adults. Harm Reduct J 2020; 17: 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Galván G, Guerrero-Martelo M, Vásquez De la Hoz F. Cannabis: a cognitive illusion. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr 2017; 46: 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weinstein ND. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J Pers Soc Psychol 1980; 39: 806–20. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arnett JJ. Optimistic bias in adolescent and adult smokers and nonsmokers. Addict Behav 2000; 25: 625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kabwama SN, Kadobera D, Ndyanabangi S. Perceptions about the harmfulness of tobacco among adults in Uganda: findings from the 2013 Global Adult Tobacco Survey. Tob Induc Dis 2018; 16. doi: 10.18332/tid/99574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Festinger L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance Evanston. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson & Company, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fotuhi O, Fong GT, Zanna MP et al. Patterns of cognitive dissonance-reducing beliefs among smokers: a longitudinal analysis from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2013; 22: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM et al. Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002–14: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3: 954–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Keyes KM et al. Recent rapid decrease in adolescents’ perception that marijuana is harmful, but no concurrent increase in use. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018; 186: 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brooks-Russell A, Ma M, Levinson AH et al. Adolescent marijuana use, marijuana-related perceptions, and use of other substances before and after initiation of retail marijuana sales in Colorado (2013–2015). Prev Sci 2019; 20: 185–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carliner H, Brown QL, Sarvet AL et al. Cannabis use, attitudes, and legal status in the U.S.: a review. Prev Med 2017; 104: 13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Keyes KM, Wall M, Cerdá M et al. How does state marijuana policy affect US youth? Medical marijuana laws, marijuana use and perceived harmfulness: 1991–2014. Addiction 2016; 111: 2187–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wadsworth E, Hammond D. Differences in patterns of cannabis use among youth: prevalence, perceptions of harm and driving under the influence in the United States where non-medical cannabis markets have been established, proposed and prohibited. Drug Alcohol Rev 2018; 37: 903–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cerda M, Wall M, Feng T et al. Association of state recreational marijuana laws with adolescent marijuana use. JAMA Pediatr 2017; 171: 142–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schuermeyer J, Salomonsen-Sautel S, Price RK et al. Temporal trends in marijuana attitudes, availability and use in Colorado compared to non-medical marijuana states: 2003–11. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014; 140: 145–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wall MM, Poh E, Cerdá M et al. Adolescent marijuana use from 2002 to 2008: higher in states with medical marijuana laws, cause still unclear. Ann Epidemiol 2011; 21: 714–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weinstein ND. What does it mean to understand a risk? Evaluating risk comprehension. JNCI Monogr 1999; 1999: 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saad L. Tobacco and Smoking. 2002. Available at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/9910/tobacco-smoking.aspx-risks. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 27. Health Canada . Canadian Cannabis Survey 2019 Detailed Data Tables. 2019. Available at: http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/200/301/pwgsc-tpsgc/por-ef/health/2019/130-18-e/index.html. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 28. Lensch T, Sloan K, Ausmus J et al. Cannabis use and driving under the influence: behaviors and attitudes by state-level legal sale of recreational cannabis. Prev Med 2020; 141: 106320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goodman S, Leos-Toro C, Hammond D. Risk perceptions of cannabis- vs. alcohol-impaired driving among Canadian young people. Drugs: Educ Prev Policy 2020; 27: 205–12. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Terry P, Wright KA. Self-reported driving behaviour and attitudes towards driving under the influence of cannabis among three different user groups in England. Addict Behav 2005; 30: 619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Slovic P. Smoking: Risk, Perception, and Policy. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lopez-Quintero C, de Los Cobos JP, Hasin DS et al. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend 2011; 115: 120–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi H-Y. Measures of substance consumption among substance users, DSM-IV abusers, and those with DSM-IV dependence disorders in a nationally representative sample. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2012; 73: 820–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fischer B, Russell C, Sabioni P et al. Lower-risk cannabis use guidelines: a comprehensive update of evidence and recommendations. Am J Public Health 2017; 107: e1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goodman S, Fischer B, Hammond D. Lower-risk cannabis use guidelines: adherence in Canada and the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2020; 59: E211–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Freeman TP, Winstock AR. Examining the profile of high-potency cannabis and its association with severity of cannabis dependence. Psychol Med 2015; 45: 3181–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van der Pol P, Liebregts N, Brunt T et al. Cross-sectional and prospective relation of cannabis potency, dosing and smoking behaviour with cannabis dependence: an ecological study. Addiction 2014; 109: 1101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Faim J, Balteiro J. Cannabis therapeutic applications - review. Eur J Public Health 2020; 30. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckaa040.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Allem J-P, Escobedo P, Dharmapuri L. Cannabis surveillance with twitter data: emerging topics and social bots. Am J Public Health 2020; 110: 357–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ishida JH, Zhang AJ, Steigerwald S et al. Sources of information and beliefs about the health effects of marijuana. J Gen Intern Med 2020; 35: 153–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Government of Canada . Cannabis Health Warning Messages. 2019. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/laws-regulations/regulations-support-cannabis-act/health-warning-messages.html. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 42. Leafly . A State-by-State Guide to Cannabis Packaging and Labeling Laws. 2015. Available at: https://www.leafly.ca/news/industry/a-state-by-state-guide-to-cannabis-packaging-and-labeling-laws. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 43. Hammond D, Goodman S, Wadsworth E et al. Evaluating the impacts of cannabis legalization: the International Cannabis Policy Study. Int J Drug Policy 2020; 77: 102698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Government of Canada . Packaging and Labelling Guide for Cannabis Products. 2019. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/cannabis-regulations-licensed-producers/packaging-labelling-guide-cannabis-products/guide.html. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 45. Fischer B, Imtiaz S, Rudzinski K et al. Crude estimates of cannabis-attributable mortality and morbidity in Canada–implications for public health focused intervention priorities. J Public Health 2016; 38: 183–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Goodman S, Wadsworth E, Schauer G et al. Use and perceptions of cannabidiol (CBD) products in Canada and the USA. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 2020; 20: 1–10. doi: 10.1089/can.2020.0093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cohen K, Weizman A, Weinstein A. Positive and negative effects of cannabis and cannabinoids on health. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2019; 105: 1139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. White CM. A review of human studies assessing cannabidiol’s (CBD) therapeutic actions and potential. J Clin Pharmacol 2019; 59: 923–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Goodman S, Rynard VL, Iraniparast M et al. Influence of package colour, branding and health warnings on appeal and perceived harm of cannabis products among respondents in Canada and the US. Prev Med 2021; 153: 106788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Drug Free Kids Canada . The Call that Comes After. 2020. Available at: https://www.drugfreekidscanada.org/prevention/drug-info/drugs-and-driving/. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 51. Government of Canada . Don’t Drive High. 2020. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/campaign/don-t-drive-high.html. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 52. Goodman S, Hammond D. Noticing of cannabis health warning labels in Canada and the US. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2021; 41: 201–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Government of Canada . Health Canada Finalizes Regulations for the Production and Sale of Edible Cannabis, Cannabis Extracts and Cannabis Topicals. 2019. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2019/06/health-canada-finalizes-regulations-for-the-production-and-sale-of-edible-cannabis-cannabis-extracts-and-cannabis-topicals.html. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 54. Statistics Canada . National Cannabis Survey, Third Quarter 2019. 2019. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/191030/dq191030a-eng.htm. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 55. Fahimi M, Barlas F, Thomas R. A Practical Guide for Surveys Based on Nonprobability Samples. 2018. Available at: https://www.aapor.org/Education-Resources/Online-Education/Webinar-Details.aspx?webinar=WEB0218. Accessed: 15 March 2022.

- 56. Hays RD, Liu H, Kapteyn A. Use of internet panels to conduct surveys. Behav Res Methods 2015; 47: 685–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Weinstein N, Slovic P, Waters E et al. Public understanding of the illnesses caused by cigarette smoking. Nicotine Tob Res 2004; 6: 349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.