Abstract

Objectives:

Prior studies have found that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are associated with asthma prevalence and onset, presumably related to stress and increased inflammation. We hypothesized that ACEs may be associated with asthma severity as well. We studied the 2016–2017 US National Survey of Children’s Health dataset to explore the relationship between ACEs and pediatric asthma severity.

Methods:

We analyzed children ages 0 to 17 years old who had current caregiver-reported asthma diagnosed by a healthcare provider. We reported descriptive characteristics using chi-square analysis of variance (ANOVA) and used multivariable regression analysis to assess the relationship of cumulative and individual ACEs with asthma severity. Survey sampling weights and SAS survey procedures were implemented to produce nationally representative results.

Results:

Our analysis included 3691 children, representing a population of 5,465,926. Unadjusted analysis demonstrated that ACEs – particularly household economic hardship, parent/guardian served time in jail, witnessed household violence, or victim/witness of neighborhood violence – were each associated with higher odds of moderate/severe caregiver-reported asthma. After controlling for confounders possibly associated with both exposure (ACEs) and outcome (asthma severity), children who witnessed parent/adult violence had higher adjusted odds of caregiver-reported moderate/severe asthma. (1.67, confidence interval 1.05–2.64, P = .03)

Conclusions:

Intrafamilial witnessed household violence is significantly associated with caregiver-reported moderate/severe asthma.

Keywords: asthma, pediatrics, adverse childhood experiences

Asthma is one of the most common chronic conditions of childhood1 but is not a homogeneous condition; rather, it is one with a variety of underlying inflammatory and sociodemographic risk factors.2 Thus, there is not a single, one-size-fits-all treatment approach. Current efforts have examined biopsychosocial models of contributing factors;3,4 and identifying these biopsychosocial factors, such as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and systemic inequities, is an important step toward preventing asthma and perhaps personalizing the asthma management approach.5

ACEs, particularly those affecting intrafamilial dynamics, are now recognized worldwide across many socioeconomic and cultural domains as stressors associated with adverse health outcomes.6-9 Stress is postulated as a key factor underlying detrimental health effects10-12 potentially due to maternal stress affecting perinatal lung development,13 genetic factors,14 environmental factors,15 and physiologic stress responses affecting the adrenocorticotropic hormone pathway response.16 Adverse childhood events might affect both the prevalence of asthma and the severity of asthma due to a stress response that can impact lung development, inflammation, and the immune system.10 These ACEs are important when considering asthma because they have now been associated with asthma prevalence and onset, although studies have not found an association between ACEs and the severity of asthma.7,17,18

We analyzed the 2016–2017 NSCH dataset with the goal to explore the relationship of ACEs to asthma severity. We hypothesized that ACEs, particularly intrafamilial factors, would be associated with more severe asthma.

Methods

The NSCH is a national, now yearly, survey to obtain national and state-level data on the emotional and physical health of children in the United States.18-20 Caregivers of children ages 0 to 17 complete an online or paper survey available in Spanish and English. The University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) institutional review board approved a waiver of consent for this secondary analysis of deidentified data.

Asthma Diagnosis and Severity

A child was considered to have asthma if the caregiver reported a health care provider ever told them the child had asthma. If they reported “yes,” to current asthma, they then reported if it was mild, moderate, or severe asthma. Because only 96 (4.8%) of the sample reported severe asthma, we combined the moderate and severe groups for our analysis; and asthma severity was classified as mild versus moderate/severe as a dichotomous variable.

ACEs

In the 2016–2017 dataset, nine ACEs were included: divorced or separated caregiver, caregiver died, caregiver ever in jail, ever witnessed violence between caregivers, ever witnessed or victim of neighborhood violence, lived with someone with mental illness, lived with someone with an alcohol or drug problem, difficulty living on household income, and treated unfairly due to race/ethnicity (Table 1). We adapted the classification method of Elmore and Crouch21 to categorize ACEs based on theme and relation to the home – seven internal (intrafamilial) stressors and two external (extrafamilial) stressors. We used a cut-point of 4 or more ACEs as has been used in other studies.22,23

Table 1.

The adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) included in the 2016–2017 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) labeled by category and whether internal or external to the household.

| To the Best of Your Knowledge, Has This Child EVER Experienced Any of the Following (Y/N)? |

ACE Category | Internal/External |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Parent or guardian divorced or separated? | Parental separation | Internal |

| 2. Parent or guardian died? | Parental separation | Internal |

| 3. Parent or guardian served time in jail? | Household dysfunction | Internal |

| 4. Saw or heard parents or adults slap, hit, kick, punch one another in the home? | Household dysfunction | Internal |

| 5. Lived with anyone who was mentally ill, suicidal, or severely depressed? | Household dysfunction | Internal |

| 6. Lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs? | Household dysfunction | Internal |

| 7. Somewhat or very often hard to get by on your family’s income (hard to cover the basics like food or housing)? | Household economic hardship | Internal |

| 8. Treated or judged unfairly because of his or her race or ethnic group? | Discrimination | External |

| 9. Was a victim of violence or witnessed violence in neighborhood? | Exposed to violence | External |

Potential Confounders

Potential confounders that might affect both the prevalence of ACEs and asthma severity and that were also available in the NSCH included 1) education level (what is the highest grade or year of school completed?); 2) insurance (is the child currently insured and by what type of healthcare plan?); 3) medical diagnosis – allergies (did a healthcare provider ever tell you the child had allergies?) and prematurity (was the child born more than 3 weeks before their due date?). Percent of federal poverty level was available, but was correlated to education level and insurance and was related to the household economic hardship ACE itself so was not included in the final analysis.

Analysis

Inclusion criteria were children with asthma and documentation of asthma severity status and ACE. Children were excluded if they had conditions that may affect respiratory mechanics, that may complicate respiratory conditions, that mimic symptoms of asthma (cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, heart conditions, sickle cell, trisomy 21 syndrome), or if there was missing asthma severity or response to the ACE questions.

We defined a bilevel domain variable, meeting the inclusion criteria (Y/N), to account for the variability of the sample size which meets the inclusion criteria and might be unrelated to the sample design. We used the DOMAIN statement to incorporate this variability into the variance estimation and treated the missingness as not missing completely at random (NOMCAR) in computation of variance for Taylor series variance estimation.24,25 Accounting for survey design, chi-square test of association (categorical data) and association analysis of variance (ANOVA) (continuous data) was used to report descriptive statistics by sociodemographics, potential confounders, and ACEs in relation to asthma severity.

We used multivariable logistic regression to analyze the relationship between ACEs and caregiver-reported moderate/severe asthma, controlling for demographic variables and potential confounders that are associated with both the exposure (ACEs) and outcomes (asthma severity).2,22,26 The variables we controlled for were age as a continuous variable, and sex, race, ethnicity, primary caregiver education, insurance, and medical diagnoses as categorical variables. We chose the model with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to choose the best subset of covariates to model the association between ACE and asthma severity.27

We performed statistical analysis using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) 9.4; Cary, North Carolina. To produce nationally representative results while accounting for the complex NSCH survey design (sampling weights, cluster, and stratum), SAS proc survey procedures were used. Sampling weights were provided by the NSCH.

Results

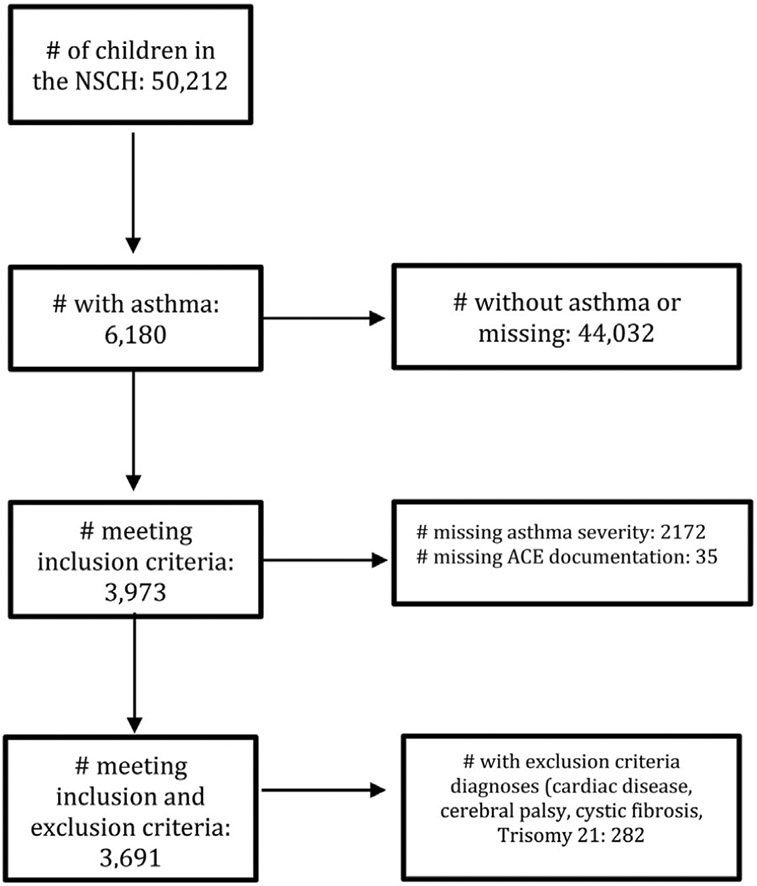

In total, 3691 (7.5%) children in the NSCH 2016-2017 dataset met our inclusion criteria for analysis out of the 50,212 children interviewed in the 2016–2017 National Survey of Children’s Health (Table 2, Figure).

Table 2.

Demographic descriptive statistics by asthma severity (mild versus moderate/severe).

| Variable | Mildn = 2651 (68%) | Moderate/Severen = 1040 (32%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 10.4 (0.17) | 9.8 (0.29) | 0.109 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.021 | ||

| Female | 1124 (39.4) | 475 (48.4) | |

| Male | 1527 (60.6) | 565 (51.6) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.014 | ||

| Asian, non Hispanic/Latino | 105 (2.9) | 32 (2.5) | |

| Black, non Hispanic/Latino | 268 (19.4) | 132 (23.5) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 278 (22.8) | 104 (7.2) | |

| Multi-racial/Other, non-Hispanic | 235 (8.8) | 104 (7.2) | |

| White | 1765 (46) | 624 (37.3) | |

| Other | 889 (54) | 416 (62.7) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.107 | ||

| Hispanic | 278 (22.8) | 148 (29.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 2373 (77.2) | 829 (70.5) | |

| Allergies | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1636 (60.3) | 836 (75.5) | |

| No | 1011 (39.7) | 199 (24.5) | |

| Premature (>3 weeks) | 0.742 | ||

| Yes | 418 (19.9) | 190 (18.9) | |

| No | 2204 (80.1) | 832 (81.1) | |

| Federal Poverty Level <100 | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 319 (24.8) | 204 (37) | |

| No | 2332 (75.2) | 836 (63) | |

| Highest level of education among reported adult | 0.033 | ||

| Less than high school | 69 (10.4) | 43 (14.7) | |

| High school degree or GED | 352 (20.1) | 193 (24.4) | |

| Some college or technical school | 640 (24.5) | 286 (29.4) | |

| College degree or higher | 1561 (44) | 497 (31.4) | |

| Type of health insurance at time | <0.001 | ||

| Public only | 592 (37.5) | 348 (47.7) | |

| Private only | 1822 (51.6) | 559 (34) | |

| Public and private | 111 (4.1) | 61 (7.3) | |

| Unspecified | 35 (1.4) | 17 (2.2) | |

| Not insured | 83 (5.3) | 51 (8.8) |

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included children from the 2016-2017 National Survey of Children’s Health.

ACEs and Asthma

Children with ACEs related to household dysfunction and economic hardship had more moderate/severe asthma overall (Table 3). Significant relationships between intra- and extrafamilial ACEs and asthma were present in the unadjusted models (Table 4). After removing the effect of potential confounding variables, children who witnessed or heard parents or adults slap, hit, kick, or punch one another in the home had higher adjusted odds of caregiver reported moderate/severe asthma (1.67, confidence interval 1.05–2.64, P = .03) at the time of this NSCH survey (Table 4).

Table 3.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in Relation to Asthma Severity (Mild Versus Moderate/Severe)

| ACE Variable | Asthma Severity |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mildn = 2651 (68%)* |

Moderate/ Severen = 1040 (32%)* |

P Value | |

| At least one ACE | 0.026 | ||

| No | 1302 (39.7) | 418 (31.6) | |

| Yes | 1349 (60.3) | 622 (68.4) | |

| Four or more ACEs | 0.039 | ||

| No | 2451 (90.4) | 911 (84.7) | |

| Yes | 200 (9.6) | 129 (15.3) | |

| Internal ACEs | |||

| Parental separation | 0.16 | ||

| No | 1800 (63.5) | 663 (57.9) | |

| Yes | 816 (36.5) | 356 (42.1) | |

| Household dysfunction | 0.017 | ||

| No | 1948 (72.2) | 694 (62.4) | |

| Yes | 628 (27.8) | 313 (37.6) | |

| Household economic hardship | 0.001 | ||

| No | 1985 (65.7) | 643 (52.8) | |

| Yes | 660 (34.3) | 390 (47.2) | |

| External ACEs | |||

| Discrimination | 0.69 | ||

| No | 2498 (93.3) | 971 (92.4) | |

| Yes | 115 (6.7) | 55 (7.6) | |

| Exposed to violence | 0.029 | ||

| No | 2457 (94.3) | 953 (90) | |

| Yes | 149 (5.7) | 71 (10) | |

Note 1: chi-square test is used to compare categorical variable.

Note 2: Sum of all categories might not add to column’s total due to item nonresponse (missing values).

Note 3: ACE Categories are as described in Table 1. Parental separation: divorced/separated or died. Household dysfunction: caregiver served time in jail; or saw or heard caregiver violence in the home; or lived with anyone mentally ill, suicidal or severely depressed; or lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol/drugs.

Weighted percentages to account for survey design.

Table 4.

Results of multivariable logistic regression measuring the association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and asthma severity, showing unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted odds ratios (aORs).

| Variable | Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | aOR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Four or more ACEs (Y vs N) | 1.70 (1.03-2.83) | 0.039 | 1.12 (0.64-1.96) | 0.252 |

| Internal ACEs (Y vs N) | ||||

| • Hard to cover basics on family’s income | 1.71 (1.23-2.38) | 0.001 | 1.19 (0.82-1.75) | 0.364 |

| • Parent or guardian served time in jail | 1.83 (1.08-3.12) | 0.026 | 1.45 (0.81-2.62) | 0.215 |

| • Saw or heard parents or adults slap, hit, kick punch one another in the home | 2.25 (1.46-3.49) | <0.001 | 1.67 (1.05-2.64) | 0.03 |

| • Lived with anyone who was mentally ill, suicidal, or severely depressed | 1.06 (0.6-1.85) | 0.843 | 0.97 (0.51-1.83) | 0.92 |

| • Lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs | 1.14 (0.73-1.79) | 0.559 | 1.08 (0.66-1.77) | 0.759 |

| • Parent or guardian, divorced or separated | 1.25 (0.89-1.75) | 0.201 | 0.94 (0.64-1.37) | 0.745 |

| • Parent or guardian died | 1.35 (0.73-2.52) | 0.337 | 1.00 (0.53-1.91) | 0.991 |

| External ACEs (Y vs N) | ||||

| • Victim of or witnessed neighborhood violence | 1.86 (1.07-3.24) | 0.029 | 1.44 (0.82-2.55) | 0.207 |

| • Treated or judged unfairly due to race/ethnicity | 1.13 (0.61-2.11) | 0.689 | 1.14 (0.57-2.3) | 0.704 |

Adjusted for sex, age, race, ethnicity, caregiver education, insurance, allergy and prematurity

Bold indicates statistically significant.

Discussion

We found that, adjusted for confounders, witnessing household adult violence was associated with a significantly higher odds of caregiver-reported moderate/severe asthma. While prior studies have demonstrated a relationship between adverse childhood experiences and the prevalence and/or onset of asthma,17,23,28 our study extends this association by finding that one particular ACE – witnessing household violence – appears to be independently related to the presence of moderate/severe asthma.29,30

Previous work suggests that intrafamilial ACEs can shape a variety of health care outcomes.6 In our study, intrafamilial ACEs such as parental divorce/separation, mental health problems or substance abuse were not associated with asthma severity (ie, caregiver-reported moderate/severe asthma), but witnessing interpartner violence was independently associated with asthma severity. This suggests that not all ACEs are equal in their possible impact on children.31 Future studies are needed to parse out the relationship between specific ACEs and child outcomes. For example, some have argued to remove parental separation or divorce as an ACE because it has become a normative phenomenon, and in many families, parents can buffer the negative impact of separation on children.32

Our finding supports other studies which documented increased odds of asthma diagnosis in children who witnessed interpartner violence. Perhaps interpersonal violence triggers a particularly strong, or a different type of stress response in children.33 It is also possible that witnessing violence between family members in the home may also be a proxy for being the victim of child abuse, but this ACE was not directly ascertained by the NSCH’s34 due presumably to issues of confidentiality.

A previous study analyzing the 2011–2012 NSCH with a similar asthma prevalence found that exposure to any ACE was associated with higher odds of having asthma and the strength of the association increased with the number of ACEs.23 That study did not find an association with ACEs and asthma severity in their analysis and this may be due to various differences in our study analysis as well as the 2016 survey redesign of ACE question administration.

Strength of the NSCH is that it reflects the composition of the United States. Shortcomings of the survey include that it is a cross-sectional study and thus cannot prove causality. The outcome measure was also based on self-reported caregiver input potentially affected by recall bias, reliance on correct diagnoses by health care providers, and potential inaccurate estimation by caregivers of asthma severity and inaccurate ACE reporting.35,36 Asthma is a heterogeneous condition with many psychosocial factors affecting outcome, including stress, lack of adherence to medications (for various reasons), and suboptimal understanding of the underlying condition; not all of these factors were captured in the NSCH questions or our study. Asthma status was based upon current symptoms due to composition of the survey that inquired about asthma severity only for those who reported current asthma symptoms. Allergy status was only available based on lifetime diagnosis. We may have inadvertently missed including variables that are potential confounders for both ACEs and asthma severity and we were unable to accurately account for obesity because it was only available for children over nine years and only parent-reported. In addition, not all key ACEs were included in the NSCH (specifically, physical, and sexual abuse). Finally, the 2016 survey sampling technique and question structure was changed significantly, making it challenging to compare results to previous years of data collection.

Our findings have implications for both clinicians and researchers. Recognizing social determinants of health and identifying the social needs of individual children and families is one of the many approaches to work toward mitigation of stress on asthma and asthma severity. Asthma is a complex condition that requires a multifaceted treatment approach from medication to addressing psychosocial needs.37 If appropriate resources are available to address them, practitioners could consider identifying children with ACEs to connect families with specific resources that will meet their needs. Clinicians may also wish to monitor children who have both asthma and ACEs more closely, and measure asthma severity periodically. Researchers may consider further investigation of intrafamilial ACEs.

We conclude that from this nationally representative survey, one intrafamilial ACE—witnessing violence among parents – was significantly associated with higher odds of caregiver-reported moderate/severe asthma in children.

What’s New.

Based on results of a national survey, an intrafamilial adverse childhood experience is associated with caregiver-reported moderate/severe asthma.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the UCLA Department of Medicine Statistical Core.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Mindy K. Ross, University of California Los Angeles, Department of Pediatrics, Pediatric Pulmonology and Sleep Medicine, Los Angeles, Calif.

Tahmineh Romero, University of California Los Angeles, Department of Medicine, Statistical Core, Los Angeles, Calif.

Peter G Szilagyi, University of California Los Angeles, Department of Pediatrics, General Pediatrics, Los Angeles, Calif.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics: Asthma. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm.

- 2.NAEPP. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:S94–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsui EC, Adamson AS, Peng RD. Time’s up to adopt a biopsychosocial model to address racial and ethnic disparities in asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:2024–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzpatrick AM, Gillespie SE, Mauger DT, et al. Racial disparities in asthma-related health care use in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:2052–2061. PMC6556425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stokes JR, Casale TB. Characterization of asthma endotypes: implications for therapy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:121–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bethell CD, Solloway MR, Guinosso S, et al. Prioritizing possibilities for child and family health: an agenda to address adverse childhood experiences and foster the social and emotional roots of well-being in pediatrics. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:S36–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bethell CD, Simpson LA, Solloway MR. Child Well-being and Adverse Childhood Experiences in the United States. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:S1–S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butchart A. Addressing adverse childhood experiences to improve public health: Expert consultation, 4–5 May 2009: Meeting report. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenberg SL, Miller GE, Brehm JM, et al. Stress and asthma: novel insights on genetic, epigenetic, and immunologic mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1009–1015. PMC4252392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright RJ, Cohen RT, Cohen S. The impact of stress on the development and expression of atopy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yonas MA, Lange NE, Celedon JC. Psychosocial stress and asthma morbidity. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:202–210. PMC3320729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trump S, Bieg M, Gu Z, et al. Prenatal maternal stress and wheeze in children: novel insights into epigenetic regulation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28616.. PMC4923849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen W, Boutaoui N, Brehm JM, et al. ADCYAP1R1 and asthma in Puerto Rican children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:584–588. PMC3733434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lietzen R, Virtanen P, Kivimaki M, et al. Stressful life events and the onset of asthma. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:1360–1365. PMC3319299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Priftis KN, Papadimitriou A, Nicolaidou P, et al. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in asthmatic children. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19:32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Exley D, Norman A, Hyland M. Adverse childhood experience and asthma onset: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24:299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Dyck P, Kogan MD, Heppel D, et al. The National Survey of Children’s Health: a new data resource. Matern Child Health J. 2004;8:183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghandour RM, Jones JR, Lebrun-Harris LA, et al. The design and implementation of the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22:1093–1102. PMC6372340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The 2016-2017 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) Combined Data Set. 2016. Available at: https://www.childhealthdata.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/2016-17-nsch_fast-facts_final6fba3af3c0266255aab2ff00001023b1.pdf?sfvrsn=569c5817_0. Accessed April 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elmore AL, Crouch E. The Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences With Anxiety and Depression for Children and Youth, 8 to 17 Years of Age. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20:600–608. PMC7340577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crouch E, Probst JC, Radcliff E, et al. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among US children. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;92:209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wing R, Gjelsvik A, Nocera M, et al. Association between adverse childhood experiences in the home and pediatric asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;114:379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brick JM, Kalton G. Handling missing data in survey research. Stat Methods Med Res. 1996;5:215–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques. John Wiley & Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, et al. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011-2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 States. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:1038–1044. PMC6248156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagenmakers E-J, Farrell S AIC model selection using Akaike weights. Psychonomic Bull Rev. 2004;11:192–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhan N, Glymour MM, Kawachi I, et al. Childhood adversity and asthma prevalence: evidence from 10 US states (2009-2011). BMJ Open Respir Res. 2014;1: e000016. PMC4212798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Penman-Aguilar A, Talih M, Huang D, et al. Measurement of health disparities, health inequities, and social determinants of health to support the advancement of health equity. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(Suppl 1):S33–S42. PMC5845853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marmot MG, Bell R. Action on health disparities in the United States Commission on social determinants of health. Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2009;301:1169–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conn AM, Szilagyi M, Forkey H. Adverse childhood experience and social risk: pediatric practice and potential. Acad Pediatr. 2020; 20:573–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner H, et al. Improving the adverse childhood experiences study scale. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167: 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suglia SF, Duarte CS, Sandel MT, et al. Social and environmental stressors in the home and childhood asthma. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:636–642. PMC3094102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cronholm PF, Forke CM, Wade R, et al. Adverse childhood experiences: expanding the concept of adversity. Am J Prev Med. 2015; 49:354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoos HL, Kitzman H, McMullen A, et al. Symptom perception in childhood asthma: how accurate are children and their parents? J Asthma. 2003;40:27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva CM, Barros L. Asthma knowledge, subjective assessment of severity and symptom perception in parents of children with asthma. J Asthma. 2013;50:1002–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:343–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]