Summary

Background

Social deprivation, psychiatric and medical disorders have been associated with increased risk of infection and severe COVID-19-related health problems. We aimed to study the rates of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in these high-risk groups.

Methods

Using health, vaccination, and administrative registers, we performed a population-based cohort study including all Danish residents aged at least 15 years, December 27, 2020, to October 15, 2021. Population groups were people experiencing: (1) homelessness, (2) imprisonment, (3) substance abuse, (4) severe mental illness, (5) supported psychiatric housing, (6) psychiatric admission, and (7) chronic medical condition. The outcome was vaccine uptake of two doses against SARS-CoV-2 infection. We calculated cumulative vaccine uptake and adjusted vaccination incidence rate ratios (IRRs) relative to the general population by sex and population group.

Findings

The cohort included 4,935,344 individuals, of whom 4,277,380 (86·7%) received two doses of vaccine. Lower cumulative vaccine uptake was found for all socially deprived and psychiatrically vulnerable population groups compared with the general population. Lowest uptake was found for people below 65 years experiencing homelessness (54·6%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 53·4-55·8, p<0·0001). After adjustment for age and calendar time, homelessness was associated with markedly lower rates of vaccine uptake (IRR 0·5, 95% CI 0·5-0·6 in males and 0·4, 0·4-0·5 in females) with similar results for imprisonment. Lower vaccine uptake was also found for most of the psychiatric groups with the lower IRR for substance abuse (IRR 0·7, 0·7–0·7 in males and 0·8, 0·8-0·8 in females). Individuals with new-onset severe mental illness and, especially, those in supported psychiatric housing and with chronic medical conditions had the highest vaccine uptake among the studied population groups.

Interpretation

Especially, socially deprived population groups, but also individuals with psychiatric vulnerability need higher priority in the implementation of the vaccination strategy to increase equity in immunization uptake.

Funding

Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed for studies of social, psychiatric, and medical factors and vaccination against Covid-19. We used the terms: “homeless*”, “shelter*”, “prison*”, “psych*”, “mental*”, “substance*”, “misuse*”, “abuse*”, “socioeconomic*”, “comorbid*”, “supported housing” (combined with “OR”) “AND” “vaccin*” AND “Covid-19”, “2019-nCoV”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “coronavirus” (combined with “OR”) in Oct, 2021 without language restrictions. Since, we have received weekly alerts from the specific search of new papers. We furthermore scanned reference lists to identify important papers.

Added value of this study

Studies have reported high risk of severe health outcomes associated with homelessness, severe mental illnesses, substance abuse, and chronic medical conditions. Crowding, lower educational level and social status have been found to be associated with increased risk of infection. Also, the importance of protecting people experiencing homelessness or imprisonment as well as people with psychiatric disorders has been highlighted.

However, there is a lack of knowledge of the actual level of vaccine coverage in the most vulnerable groups in our society. A large study from England found lower vaccine uptake during the first months of mass vaccination for people with higher social deprivation and severe mental illness. A few studies from the US of selected population groups experiencing homelessness reported lower vaccine uptake. People with schizophrenia in Israel were also found to have lower vaccine uptake than the general population whereas patients from a psychiatric hospital in Belgium had a high uptake. Vaccine willingness and hesitancy have also been highlighted in several studies. Among those focusing on minority groups, study populations were mostly small and selected. A global survey showed that higher social status was linked to higher willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 in some high-income countries. However, willingness to get the vaccine was also found to be country-specific and to be associated with high adherence to governmental measures.

Implications of all the available evidence

This study is the first to present nationwide and complete information on vaccine uptake by vulnerable population groups compared with the non-exposed general population, presenting both unadjusted cumulative vaccine uptake and adjusted relative numbers by sex. We documented lower vaccine uptake during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic for people experiencing homelessness, imprisonment, and crisis shelter stay compared with non-exposed individuals. We were also able to show that people with substance abuse and severe mental illness as well as recent psychiatric admission had higher vaccine uptake than people experiencing social deprivation, but still lower uptake than in the comparison groups without the specific psychiatric disorders from the general population. Individuals in supported psychiatric housing had higher vaccine uptake than individuals not living in such facilities, which was equal to results for chronic medical conditions in adjusted analyses. As of Oct 15, 2021, socially marginalised people in Denmark as well as individuals with severe psychiatric problems are not sufficiently protected against adverse outcomes related to SARS-CoV-2 infection when compared with the general population.

Implications of all the available evidence: With the documentation of lower vaccine uptake in highly vulnerable groups compared with the non-exposed general population, we address the need for greater awareness among policymakers and health authorities that socially deprived and psychiatrically vulnerable individuals must be given higher priority in the national vaccination strategy. These individuals should be included early and with higher weight to obtain an equal and high vaccine coverage in welfare societies. The next step might be to find out how to increase the vaccine uptake in these specific populations and to replicate the findings in other countries. We also need to be aware of other potential high-risk groups which were not included in the current study. Finally, documentation of the health consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection in marginalised high-risk groups is also important as this could further support the need for improved preventive work aimed at these groups in future pandemics.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic continues to have enormous societal consequences worldwide.1 As of Feb 21, 2022, it has resulted in more than 5.87 million deaths.1 Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection have been an essential tool to obtain control of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulted in reductions of both deaths and severe morbidity.2,3 Although the vaccine effectiveness against any SARS-CoV-2 infection has been reported to be waning over time, protection seems to remain at least for six months after second dose.4

WHO has highlighted that the most vulnerable individuals should have highest priority for vaccine.2 People experiencing homelessness or imprisonment and people with severe mental illnesses and substance abuse have been found to be high-risk groups of SARS-CoV-2 infection5,6 and severe COVID-19-related outcomes,6, 7, 8 but little is known about the vaccine uptake in these specific population groups. Poor social connectedness in older people has previously been linked to higher risk of non-participation in prevention health services.9 Some minor studies have suggested mistrust to the vaccines in highly vulnerable groups.10,11 However, few studies of SARS-CoV-2 infection vaccine uptake including data on marginalised groups exist.12, 13, 14 A large study from England.found individuals with higher levels of social deprivation and severe mental illness to have reduced chance of being vaccinated.12 Also, a study from Israel found individuals with schizophrenia to have lower vaccine uptake than the general population.13 Studies of disparities in vaccine uptake after the vaccines have become fully available are lacking.12,13

In Denmark, every person above the age of 15 has been personally invited to vaccination. Vaccination is free for all and primarily takes place in public vaccination centres across the country.15 In Denmark, the vaccination coverage has been in the top five among European countries during the entire autumn of 2021,16 and booster doses have been administered.17 Danish residents have high trust in the national health authorities,15 which has been found to be an important factor of vaccine acceptance.18 However, we hypothesised that even in Denmark social deprivation factors10,12 and severe psychiatric disorders,12,13 including substance abuse,11 would be associated with lower vaccination rates against COVID-19 compared to the general population.12,13 We also expected that individuals recently admitted to a psychiatric department,19 in supported psychiatric housing,19,20 and with contact to other health facilities due to severe medical disorders would have vaccination rates equal to or above those in the non-exposed groups.12

We aimed to quantify the vaccine uptake against SARS-CoV-2 infection in vulnerable population groups characterised by social, psychiatric, or medical exposures compared with the non-exposed individuals from the Danish general population.

Methods

Study participants

This register-based cohort study included all Danish residents being alive and living in Denmark on Dec 27, 2020 (i.e. first date of vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 infection in Denmark) and aged at least 15 years on the day of inclusion. The Danish Civil Registration System, containing data on death, emigration, and disappearance, was used to establish the cohort and for follow-up with updates until Oct 15, 2021.21 The personal identification number (the CPR number) ensured accurate linkage between registers.

Data

Exposures

We studied selected population groups characterised by either experiences involving social or psychiatric vulnerability during 2020 or pre-existing morbidity: (1) homelessness, (2) imprisonment, (3) substance abuse, (4) severe mental illness, (5) supported psychiatric housing, (6) psychiatric hospital admission, and (7) chronic medical condition. We also included a few supplementary predictors: (1) highest educational level, (2) crisis shelter stay, (3) new-onset severe mental illness, (4) any mental disorder, (5) medical overweight, and (6) history of any infection with hospital contact (appendix p. 1).

Information on experiences of homelessness during 2020 was obtained from the Danish Homeless Register.22 This nationwide register contains complete data on individual-level homeless shelter contacts (under the Consolidation Act of Social Services Section 110) since 1999.23 Individual-level information on most recent postal address in a homeless shelter during 2020 was included. Data on imprisonment during 2020 was obtained from the Danish Central Criminal Register, which contains information on all imprisonments since 1991.24

Data on supported psychiatric housing during 2020 was exclusively based on information of the most recent postal address during 2020. We were able to link this information to the official addresses of these supported housing facilities (the Act of Social Services Section 107 and 108), which are listed on the Danish website “Tilbudsportalen”.25 Diagnoses of severe mental illness and substance abuse were obtained from the Danish National Patient Register.26 This register contains information on psychiatric public and private admissions, outpatient contacts, and diagnoses from 1995 to 2021. Disorders diagnosed up to 1994 were retrieved from the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. All diagnoses were defined according to the international Classification of Disease 10th revision (ICD-10) with corresponding codes for ICD-8 (appendix p. 2). Severe mental illness was defined as having either a diagnosis of schizophrenia (F20), bipolar disorder (F30-31), or depressive disorder (F32-33). The Danish National Patient Register also contains information on all somatic inpatient contacts since 1977 and outpatient contacts since 1995 and was furthermore used to study chronic medical conditions as exposure.21 This covariate was defined in accordance with an algorithm used in a previous study based on 31 medical conditions categorised within nine broad groups (appendix, p. 4).27 Relevant dispensed prescriptions based on the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes from the Danish National Prescription Registry were also used, also for the definition of substance abuse.28 Furthermore, we used self-reported data on treatment for substance abuse (1996-2018) from The Registry of Drug Abusers Undergoing Treatment (SIB) and The National Registry of Alcohol Treatment (NAB) in the definition of substance abuse (appendix p. 2–4).

Information on sociodemographic factors used for adjustments, i.e. age, sex, and country of origin, was obtained from the Civil Registration System.21 The national Danish Microbiology Database (MiBa)29 contains information on all SARS-CoV-2-PCR-tests based on throat swabs in Denmark which were conducted at clinical laboratories or in any of the free-of-charge test stations.15

Legal permission was obtained from the Danish Data Protection Agency (P-2020-439), Statistics Denmark, and the Danish Health Data Authority. Ethical permission is not required for register-based studies according to Danish regulations.

Outcomes

Our outcome was vaccine uptake, defined as second dose of any vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection which was offered as part of the vaccine rollout in Denmark: BNT162b2 (Pfizer BioNTech), mRNA-1273 (Moderna), Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson), or ChAdOx1 (AstraZeneca). For the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, only one dose was required and, thus, the first dose was used as outcome in these cases. The rollout of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination was targeted according to the Danish Health Authority's specification of 12 target groups.15

The vaccine data were retrieved from the Danish Vaccination Register30 containing individual-level information on the dates for and type of vaccines given. These data were provided through the Danish Health Data Authority.

Statistical analyses

Cohort participants were followed from Dec 27, 2020, or from the study participants’ 15th birthday, whichever came last, and until they received their second dose of vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection, disappeared or left the country, died, or until the end of study on Oct 15, 2021. We used Poisson regression analysis with risk time as offset to calculate incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with Wald 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Poisson regression analysis approximates Cox regression.31 The statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4.). We studied each of our selected population groups in an independent analysis (i.e. conducting eight regression analyses including all individuals qualifying for analysis, but without adjusting for the other population groups).

All our survival analyses were adjusted for age (5-years groups) and calendar time (months), and either adjusted for or stratified by sex (male, female). In a second model, we additionally adjusted for country of birth (Denmark, other Western countries, or Non-Western countries) as this factor was expected to be a potential confounder.12

To study the unadjusted cumulative vaccine uptake by each exposed population group compared with non-exposed (i.e., without the specific exposed population group) individuals from the general population, we used the Aalen-Johansson estimator to calculate cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) considering competing risks from death and a PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. For these analyses, all covariates were fixed, and individuals were required to be 15 years of age on the start date, i.e. Dec 27, 2020. The curves were smoothed to ensure anonymity of all individuals. Gray's test was used to study whether there was evidence of difference between the groups at a type I error rate (alpha) of 5%.32

Homelessness, imprisonment, supported psychiatric housing, and recent psychiatric admission were defined as any experience of the specific exposure during 2020 versus no such experience. Severe mental illness and substance abuse were defined as any history prior to Dec 27, 2020 versus no history prior to that date. Chronic medical condition was defined as any diagnosis since Jan 1, 2016 and until Dec 27, 2020 (for further details see appendix p. 1).

The supplementary exposures were defined as binary covariates with exposure status being: primary school as highest completed educational level per September 2019, any crisis shelter stay during 2020, new-onset severe mental illness during 2020, pre-existing mental disorder, pre-existing medical overweight, and history of infection with hospital contact (appendix p. 1–4).

We did supplementary analyses of first dose of vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection by population groups to see if results were different from our main analysis using the data of the second dose given.

We also did sensitivity analyses of second dose of vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection using a few other categorisations of some of the exposure covariates to see whether these definitions resulted in comparable results (appendix p. 1).

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript. SFN, MO, and CH had full access to all the data in the study, and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Results

From Dec 27, 2020, to Oct 15, 2021, 4,935,344 individuals aged 15 years or above (2,495,229 females and 2,440,115 males) were included in the study cohort accounting for 2,560,981 person-years under observation for two doses of vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection. In all, 4,277,380 (86·7%) individuals completed their vaccination schedules by receiving: the Pfizer BioNTech vaccine (3,641,583; 85·1%), Moderna (587,976;13.8%), Johnson & Johnson (46,271; 1·1%), or AstraZeneca (1550; 0·04%). During the study period, 286,521 (5·8%) individuals had a PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. The mean age of participants was 48 years (SD 20) on Dec 27, 2020.

Study characteristics including total numbers of individuals with vaccine uptake of second dose, person-years, and unadjusted incidence rates (IRs) were presented for the general population and by population groups (Table 1). The unadjusted vaccine uptake in the general population was higher among females than males. People born in Denmark had higher rates than those born in other countries, and individuals without SARS-CoV-2 infection had higher vaccine uptake than those with a history of infection.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics by population groups and in the entire Danish general population, Dec 27, 2020 to Oct 15, 2021.

| Entire general population |

Homelessness during 2020 |

Imprisonment during 2020 |

Substance abuse† |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd vaccine (n) | Person-years | IR per 100 person-years | (95% CI) | 2nd vaccine (n) | Person-years | IR per 100 person-years | (95% CI) | 2nd vaccine (n) | Person-years | IR per 100 person-years | (95% CI) | 2nd vaccine (n) | Person-years | IR per 100 person-years | (95% CI) | |

| Total | 4,277,380 | 2,560,981 | 167 | (167-167) | 3829 | 4084 | 94 | (91-97) | 25,764 | 27,728 | 93 | (92-94) | 225,667 | 152,688 | 148 | (147-148) |

| Age, years mean (SD)* | 48 (20) | 41 (14) | 45 (13) | 50 (17) | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 2,095,180 | 1,302,020 | 161 | (161-161) | 2929 | 3050 | 96 | (93-100) | 24,110 | 26,204 | 92 | (91-93) | 131,249 | 91,251 | 144 | (143-145) |

| Female | 2,182,200 | 1,258,961 | 173 | (173-174) | 900 | 1034 | 87 | (82-93) | 1654 | 1524 | 109 | (103-114) | 94,418 | 61,436 | 154 | (153-155) |

| Country of origin | ||||||||||||||||

| Denmark | 3,828,313 | 2,138,682 | 179 | (179-179) | 3082 | 3020 | 102 | (99-106) | 22,174 | 21,287 | 104 | (103-106) | 210,597 | 137,973 | 153 | (152-153) |

| Other Western countries | 167,992 | 155,010 | 108 | (108-109) | 129 | 157 | 82 | (69-98) | 394 | 503 | 78 | (71-86) | 5479 | 4353 | 126 | (123-129) |

| Non-Western countries | 281,075 | 267,289 | 105 | (105-106) | 618 | 908 | 68 | (63-74) | 3196 | 5939 | 54 | (52-56) | 9591 | 10,362 | 93 | (91-94) |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 197,724 | 126,526 | 156 | (156-160) | 113 | 136 | 83 | (69-100) | 805 | 1077 | 75 | (70-80) | 6993 | 4885 | 143 | (140-147) |

| No | 4,079,656 | 2,434,455 | 168 | (167-168) | 3716 | 3948 | 94 | (91-97) | 24,959 | 26,651 | 94 | (94-95) | 218,674 | 147,803 | 148 | (147-149) |

| Severe mental illness† | Supported psychiatric housing during 2020 | Psychiatric admission during 2020 | Chronic medical condition‡ | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 227,813 | 142,193 | 160 | (160-161) | 7443 | 4702 | 158 | (155-162) | 10,853 | 6457 | 168 | (165-171) | 1,973,249 | 961,452 | 205 | (205-206) |

| Age, years mean (SD)* | 51 (18) | 35 (18) | 51 (25) | 59 (19) | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 85,495 | 55,794 | 153 | (152-154) | 4617 | 3005 | 154 | (149-158) | 5122 | 3172 | 161 | (157-166) | 896,652 | 442,430 | 203 | (202-203) |

| Female | 142,318 | 86,399 | 165 | (164-166) | 2826 | 1697 | 167 | (167-173) | 5731 | 3285 | 174 | (170-179) | 1,076,597 | 519,022 | 207 | (207-208) |

| Country of origin | ||||||||||||||||

| Denmark | 203,889 | 122,308 | 167 | (166-167) | 6653 | 3925 | 170 | (165-174) | 9818 | 5455 | 180 | (176-184) | 1,812,627 | 849,360 | 213 | (213-214) |

| Other Western countries | 6062 | 4291 | 145 | (141-148) | 195 | 209 | 93 | (81-107) | 408 | 329 | 124 | (113-137) | 54,606 | 31,903 | 171 | (170-173) |

| Non-Western countries | 17,862 | 15,694 | 114 | (112-116) | 595 | 568 | 105 | (97-114) | 627 | 672 | 93 | (86-101) | 106,016 | 80,189 | 132 | (131-133) |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 8370 | 5291 | 158 | (155-162) | 265 | 180 | 147 | (130-166) | 533 | 299 | 178 | (164-194) | 74,336 | 39,444 | 188 | (187-190) |

| No | 219,443 | 136,902 | 160 | (160-161) | 7178 | 4522 | 159 | (155-162) | 10,320 | 6158 | 168 | (164-171) | 1,898,913 | 922,008 | 206 | (206-206) |

IR=incidence rate. Data are numbers unless otherwise specified. Person-years are rounded. *Mean age at the time of study start, Dec 27, 2020. †Any diagnosis prior to study start. ‡Defined as any diagnosis from Jan 1, 2016 to study start.

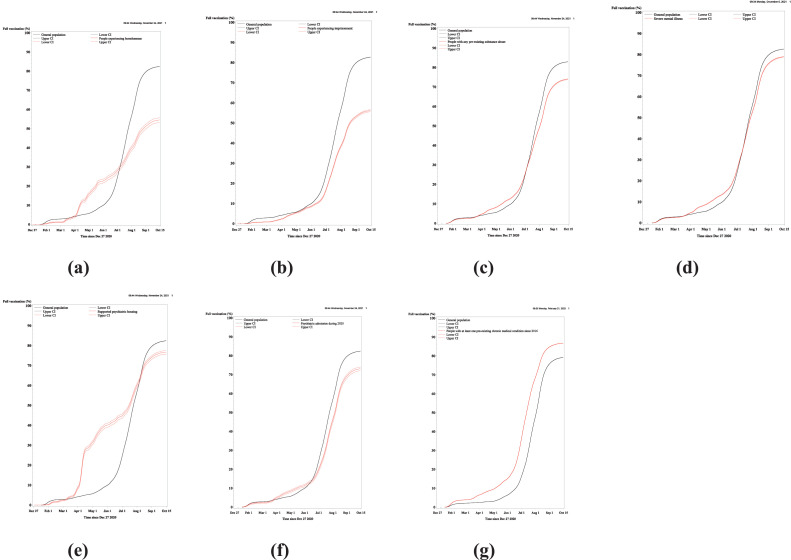

Unadjusted vaccine coverage

The cumulative vaccine uptake by population groups aged 15–64 years (Figure 1) showed markedly lower vaccine uptake for socially deprived populations, including people experiencing homelessness (CIF=54·6%, 95% CI 53·4–55·8, p < 0·0001) and imprisonment (CIF=56·2%, 95% CI 55·7–56·7, p < 0·0001), compared with individuals not exposed to homelessness and imprisonment, respectively (CIF estimates by population groups, overall and sex-specific vaccine coverage, and vaccine coverage by target groups during roll out of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination are presented in the appendix p. 6–10). The vaccine uptake for people with psychiatric exposures, especially substance abuse and psychiatric admission, but also severe mental illness and supported psychiatric housing, was also lower than in the non-exposed individuals (p < 0·0001). Among the psychiatric groups, highest cumulative vaccine uptake was found for severe mental illness (CIF=79·0%, 78·8-79·2) and lowest uptake for substance abuse (CIF=74·1%, 73·9–74·2). People with chronic medical conditions had the highest vaccine uptake (CIF=86·8%, 86·8–86·9), which was higher than in people without chronic medical conditions (p < 0·0001).

Figure 1.

Cumulative vaccine uptake by population groups in individuals aged 15-64 years, Dec 27, 2020 to Oct 15, 2021. The figures show the cumulative incidence functions of second dose of vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection by homelessness, imprisonment, substance abuse, severe mental illness, supported psychiatric housing, psychiatric admission, and chronic medical conditions compared with the non-exposed individuals from the general population (each comparison group excludes the specific exposed population group). The vaccines were offered at different points of time to different target populations. Older age-groups were prioritized in the vaccine rollout. The curves show the pattern of vaccine rollout for the specific population groups. Estimates at the end of follow-up, Oct 15, 2021, were used for comparison of the probability of second vaccine dose between groups, because all individuals aged 15 years and above had been invited for their second shot at that point. Competing risk from death and SARS-CoV-2 infection was considered in the analysis. The curves were smoothed to ensure anonymity of all individual cases.

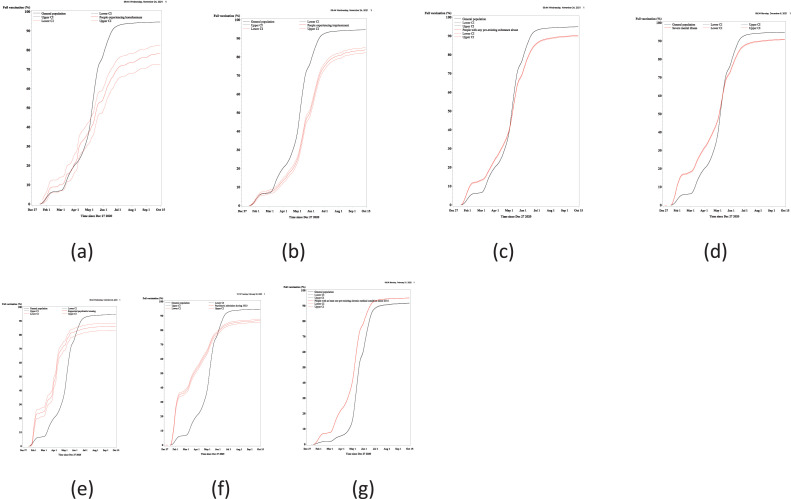

The cumulative vaccine uptake by population group in individuals 65 years old and above is presented in Figure 2. Also, in the older age-group, the vaccine uptake was lower for both social and psychiatric exposures and higher for chronic medical conditions compared with individuals without these specific exposures (p < 0·0001, except supported psychiatric housing: p=0·024). The lowest cumulative vaccine uptake was found for people experiencing homelessness (CIF=78·0%, 95% CI 72·7–82·4) (appendix p. 10).

Figure 2.

Cumulative vaccine uptake by population groups in individuals aged 65+ years, Dec 27, 2020 to Oct 15, 2021. The figures show the cumulative incidence functions of second dose of vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection by homelessness, imprisonment, substance abuse, severe mental illness, supported psychiatric housing, psychiatric admission, and chronic medical conditions compared with the non-exposed individuals from the general population (each comparison group excludes the specific exposed population group). The vaccines were offered at different points of time to different target populations. Older age-groups were prioritized in the vaccine rollout. The curves show the pattern of vaccine rollout for the specific population groups. Estimates at the end of follow-up, Oct 15, 2021, were used for comparison of the probability of second vaccine dose between groups, because all individuals aged 15 years and above had been invited for their second shot at that point. Competing risk from death and SARS-CoV-2 infection was considered in the analysis. The curves were smoothed to ensure anonymity of all individual cases.

Among individuals aged < 65 years experiencing homelessness and in supported psychiatric housing, higher cumulative probability was identified early in follow-up period (i.e., from April 2021) compared with the non-exposed comparison groups (for illustration of the vaccine target groups in Denmark see appendix p. 8). This reflects that these groups were prioritised for the vaccine at that time, but the curves also show how this higher cumulative vaccine uptake in these vulnerable groups were overtaken by the general population after a few months. In the older population, individuals in supported psychiatric housing and those with severe mental illness and substance abuse had higher cumulative vaccine uptake from February to around May 2021 compared with the general population without such psychiatric morbidity, but hereafter this pattern was turned around (Figures. 1 and 2). The number of days between first and second dose of vaccine differed only with few days between the subgroups. The 99th percentile was 86 days in the general population, 90 days in people experiencing homelessness, and 81 days in people experiencing imprisonment (appendix p. 11).

Adjusted analyses of vaccine uptake

Table 2 shows the adjusted IRRs of vaccine uptake by population group. In both males and females, lower vaccine uptake was found for homelessness (IRR 0·5, 95% CI 0·5–0·6 in males and 0·4, 0·4-0·5 in females) compared with the individuals not experiencing homelessness. Similarly reduced rates were found for people experiencing imprisonment. For the groups with psychiatric morbidity, the lowest IRR was found for males with substance abuse (IRR 0·7, 0·7-0·7). The highest IRR was found for females with psychiatric admission (0·9, 0·9–0·9). Severe mental illness was associated with similar rates of vaccine uptake. In contrast, supported psychiatric housing was associated with increased IRRs of vaccine uptake in males and females (IRR 1·2, 1·1-1·2) as well as chronic medical condition (Table 2). Additional adjustment for country of origin did not change the results (appendix p. 12).

Table 2.

Incidence rate ratios for second dose of vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection by population group, Dec 27, 2020 to Oct 15, 2021.

| Males |

Females |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd vaccine | Person-years† | IRR* | 95% CI | 2nd vaccine | Person-years† | IRR* | 95% CI | |

| Overall | 2,095,180 | 1,302,020 | 2,182,200 | 1,258,961 | ||||

| Homelessness during 2020 | ||||||||

| Any | 2929 | 3050 | 0·5 | (0·5-0·6) | 900 | 1034 | 0·4 | (0·4-0·5) |

| No | 2,092,251 | 1,298,970 | 1 | 2,181,300 | 1,257,927 | 1 | ||

| Imprisonment during 2020 | ||||||||

| Any | 24,110 | 26,204 | 0·5 | (0·5-0·5) | 1654 | 1524 | 0·5 | (0·5-0·5) |

| No | 2,071,070 | 1,275,815 | 1 | 2,180,546 | 1,257,438 | 1 | ||

| Substance abuse§ | ||||||||

| Any | 131,249 | 91,251 | 0·7 | (0·7-0·7) | 94,418 | 61,436 | 0·8 | (0·8-0·8) |

| No | 1,963,931 | 1,210,768 | 1 | 2,087,782 | 1,197,525 | 1 | ||

| Severe mental illness§ | ||||||||

| Any | 85,495 | 55,794 | 0·8 | (0·8-0·8) | 142,318 | 86,399 | 0·8 | (0·8-0·8) |

| No | 2,009,685 | 1,246,226 | 1 | 2,039,882 | 1,172,562 | 1 | ||

| Supported psychiatric housing during 2020 | ||||||||

| Any | 4617 | 3005 | 1·2 | (1·1-1·2) | 2826 | 1697 | 1·2 | (1·1-1·2) |

| No | 2,090,563 | 1,299,015 | 1 | 2,179,374 | 1,257,264 | 1 | ||

| Psychiatric hospital admission during 2020 | ||||||||

| Any | 5122 | 3172 | 0·8 | (0·8-0·8) | 5731 | 3285 | 0·9 | (0·9-0·9) |

| No | 2,090,058 | 1,298,848 | 1 | 2,176,469 | 1,255,677 | 1 | ||

| Chronic medical condition¶ | ||||||||

| Any | 896,652 | 442,430 | 1·3 | (1·3-1·3) | 1,076,597 | 519,022 | 1·2 | (1·2-1·2) |

| 0 | 1,198,528 | 859,590 | 1 | 1,105,603 | 739,940 | 1 | ||

IRR=incidence rate ratio

*Adjusted for age (5-years groups) and calendar time (months). All p-values are <0·0001. †Person-years are rounded. §Any diagnosis prior to study start. Severe mental illness is defined as at least one of the following diagnoses: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depressive disorders. ¶Defined as any diagnosis from Jan 1, 2016 to study start.

Supplementary population groups

Results for the supplementary groups are presented in the appendix p. 13-17. A lower educational level (i.e. primary school as the highest completed education) was associated with 20% reduced risk of vaccine uptake (IRR 0·8, 0·8-0·8) compared with a higher educational level, after adjustment (appendix p. 13, 18). New-onset severe mental illness during 2020 compared to absence was associated with only slightly lower vaccine uptake (adjusted IRRs were: 0·9, 0·9-1·0 in males and 1·0, 0·9-1·0 in females, appendix p. 18).

Sensitivity analyses

Overall, the patterns of results with vaccine uptake of first dose as outcome were similar to those using the second dose, as shown in the sensitivity analyses (appendix p. 19-24).

When defining homelessness and imprisonment as any history of these experiences prior to 2021 rather than only during 2020, the main results remained unchanged. An increasing IRR of vaccine uptake was associated with increasing numbers of different medical conditions (i.e. having three or more chronic medical conditions was associated with the higher IRR: (1·5, 1·5-1·5 in males and 1·3, 1·3-1·3 in females) compared with those without such conditions (appendix p. 25).

Discussion

In this Danish nationwide, register-based cohort study based on 4.9 million individuals above 15 years of age, studied from Dec 27, 2020 to Oct 15, 2021, we were able to document that especially socially deprived population groups, including homelessness and imprisonment, had lower vaccine uptake compared with the general population, even after adjustments, but it also applied to individuals with a low educational level. Albeit with a higher vaccine uptake than the socially deprived population groups, psychiatrically vulnerable individuals had reduced uptake compared with the general population. However, new-onset severe mental illness and, especially, supported psychiatric housing and chronic medical conditions were associated with highest vaccine uptake among the studied high-risk groups.

This is a large and representative cohort study addressing differences in uptake of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection in social, psychiatric, and medical high-risk groups in comparison with the general population. Access to complete data on homelessness, imprisonment, crisis shelter, and supported psychiatric housing is unique for Denmark, and we believe this contributes with new knowledge about a small and understudied segment of society. We present absolute and relative adjusted estimates of the vaccine uptake during more than nine months of follow-up using complete data and were able to stratify by sex.

Patients with severe mental illness and people who were currently experiencing homelessness were in principle targeted in the Danish vaccine strategy. They were included in a priority group five following, (1) persons living in nursing homes, (2) persons aged >65 years who receive home care, (3) persons aged >85 years, and (4) frontline staff in the healthcare sector with an increased risk of infection, or who carry out critical functions.15 However, the prioritisation of these groups was not made from the launch of the vaccination programme.20 Besides, only those who also had severe medical diagnoses qualified for being at high-risk targeted in group five. As of March 2021, the socially deprived groups, including people experiencing homelessnes, people with substance abuse, and individuals staying in prisons were included in target groups prior to the general population, but still with adherence to the age-criteria.15 According to the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) a few other EU countries have officially included homelessness as high-priority in their national vaccination strategy,33 and people experiencing imprisonment were included as a priority group in a third of the EU countries.33

Although marginalised people to some degree were included in the vaccine plans in Denmark, people without close contact to the health system13,34 or who were not staying in a homeless shelter at the exact point in time when the vaccination rollout took place would probably not easily receive the vaccine. Besides, the lower vaccine uptake in our high-risk population groups might not only be a result of difficulties in terms of access to vaccines, but also of a lack of awareness, and lower trust in authorities as well as of the benefit of being vaccinated than in the general population.10,11 All in all, these challenges might relate to implementation failures rather than a lack of knowledge or a lack of policy targeting vulnerable populations. Thus, improved collaboration with the trusted social workers and organisations and psychiatric outreach teams could be important contributions to the vaccination strategy. Mobile vaccine units and vaccination in homeless shelters and night shelters may also be among the important tools for increasing the immunisation in the most socially and psychiatrically vulnerable groups.

Our results are not easily compared to previous studies. However, the lower vaccine uptake among socially deprived population groups as well as people with a low educational level supports results showing lower vaccine coverage in individuals from socioeconomically deprived areas.12 In the US, people experiencing homelessness were found to have vaccination rates of 11-37 fewer percentage points relative to the general population.14 However, WHO Europe reported high vaccine uptake in prisons in some countries.35

As regards psychiatric exposures, we were able to include sub-groups not hitherto studied, including recent psychiatric admission, supported psychiatric housing, substance abuse, and new-onset severe mental illness. Our results of lower vaccine uptake in people with severe mental illness were in line with a few previous studies.12,13 However, a Belgian study of patients admitted to a university psychiatric hospital found a vaccine uptake of 92%, which was comparable to that of the general population.19 In our study, people in supported psychiatric housing and people with new-onset severe mental illness had, as expected, the higher vaccination rates after adjustment as compared with other psychiatric exposures (i.e. any severe mental illness, mental disorder, and substance abuse). This suggests that special attention as regards vaccination should be given to people with psychiatric disorders not recently diagnosed. These individuals might have poorer social connectedness, which has been found to be associated with non-participation in preventive health care.9 Furthermore, vaccination of individuals with the primary series will prevent hospitalisation to a higher degree than booster doses to the already vaccinated.17 Our findings of high vaccine uptake in people with medical conditions support previous findings.12

Our study had limitations. First, we cannot say whether the lower vaccine uptake among people with social and psychiatric exposures could be explained by vaccine hesitancy, lack of availability or accessibility, lack of trust, or lack of information. People experiencing homelessness or imprisonment, but also people with psychiatric disorders, often have limited contact with the health system, complex personal problems, less use of primary care, and undiagnosed as well as untreated disorders.9,36,37 Such factors might contribute to the lower vaccine uptake.9 Second, misclassification of exposure covariates might exist. Some of the people experiencing homelessness early in 2020 may not have remained in a homeless situation during the entire follow-up period. These individuals count as homeless even though the homelessness might be restricted to a short period of time. Also, we cannot say whether people were exposed at the time of receiving or being offered the vaccine. As regard the cumulative probabilities, deaths in the vulnerable groups occur more frequently than in the general population. This might artificially have lowered the CIFs in these groups, but only to a small degree. Thus, it is not expected to have influenced the results. Because of few deaths in the follow-up period, we did not include death as a competing risk in the regression model. Although it could have a slight tendency to overestimation, it has limited influence on the results.

We expect that the vaccination uptake in vulnerable groups in Denmark is high compared with most other high-income countries. Differences in the political handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, trust in the authorities, the health system capacity, and the national vaccine coverage are likely contributors to the vaccine uptake in vulnerable groups.33 The differences between vaccine uptake in high-risk groups and the general population could be even more pronounced in countries with a less accessible health service system. However, it might be that the relative differences can be generalised to other high-income countries in which universal and free access to vaccination has been implemented.

Studies of vaccine uptake in high-risk groups from other countries as well as studies of other high-risk groups will be relevant to further support our findings. Also, studies identifying the contributing factors explaining the lower vaccine uptake in vulnerable groups are important. Besides, future studies documenting the SARS-CoV-2 infection-related morbidity and mortality in these and other high-risk groups might support the importance of vaccine prioritisation of these individuals in future.

Conclusions

Even in a country like Denmark with universal and free access to health services and with health authorities doing a tremendous job to ensure that all individuals are informed about and get access to vaccination, marked differences in vaccine uptake exist between some of the most vulnerable population groups characterised by social, but also psychiatric exposures, and the general population. Thus, the work with implementation of vaccination in high-risk groups (i.e. people experiencing homelessness and imprisonment, having substance abuse and severe mental illness) should be given higher priority to obtain a more equal and high vaccine coverage. While several individuals are receiving their third dose of vaccine, we need to consider how to help the socially deprived and psychiatric minority groups to receive their first and second dose. There is a need for higher attention from policymakers and health authorities to address this issue during the current and future pandemics and epidemics.

Contributors

MN obtained funding for the study. MN, SFN, TML, MO, CH, SE, MB, and KM designed the study. SFN, CH, and MO had full access to all data in the study and verify the underlying data. SFN takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. SFN analysed the data with supervision from TML. All authors interpreted the data. SFN drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

We declare no competing interests. As a governmental institution, Statens Serum Institut is involved in the national vaccine distribution chain; receiving, storing and distributing vaccines to doctors and vaccine centres within Denmark.

Acknowledgments

Data statement

According to Danish regulations, we are not allowed to share our data.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation to MN (grant number NFF20SA0063142).

The Danish Departments of Clinical Microbiology (KMA) and Statens Serum Institut carried out laboratory analyses, registration, and release of the national SARS-CoV-2 surveillance data for the present study.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100355.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2021. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 22 February 2021.

- 2.World Health Organization. COVID-19 vaccines. 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines. Accessed 22 December 2021.

- 3.Haas E.J., Angulo F.J., McLaughlin J.M., et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. 2021;397:1819–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chemaitelly H., Tang P., Hasan M.R., et al. Waning of BNT162b2 vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in Qatar. N Engl J Mede. 2021;385:e83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2114114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaudry G., Zhong S., Whiting D., Javid B., Frater J., Fazel S. Managing outbreaks of highly contagious diseases in prisons: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richard L., Booth R., Rayner J., Clemens K.K., Forchuk C., Shariff S.Z. Testing, infection and complication rates of COVID-19 among people with a recent history of homelessness in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2021;9:E1–E9. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vai B., Mazza M.G., Delli Colli C., et al. Mental disorders and risk of COVID-19-related mortality, hospitalisation, and intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:797–812. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00232-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Q.Q., Kaelber D.C., Xu R., Volkow N.D. COVID-19 risk and outcomes in patients with substance use disorders: analyses from electronic health records in the United States. Mol Psychiatry. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-00880-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stafford M., von Wagner C., Perman S., Taylor J., Kuh D., Sheringham J. Social connectedness and engagement in preventive health services: an analysis of data from a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3:e438–e446. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30141-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker J.S., D'Amico E.J., Pedersen E.R., Garvey R., Rodriguez A., Klein D.J. COVID-19 vaccination rates and attitudes among young adults with recent experiences of homelessness. J Adolesc Health. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masson C.L., McCuistian C., Straus E., et al. COVID-19 vaccine trust among clients in a sample of California residential substance use treatment programs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;225 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis H.J., Inglesby P., Morton C.E., et al. Trends and clinical characteristics of 57.9 million COVID-19 vaccine recipients: a federated analysis of patients' primary care records in situ using OpenSAFELY. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;72:e51–e62. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0376. the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tzur Bitan D., Kridin K., Cohen A.D., Weinstein O. COVID-19 hospitalisation, mortality, vaccination, and postvaccination trends among people with schizophrenia in Israel: a longitudinal cohort study. lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:901–908. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00256-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montgomery M.P., Meehan A.A., Cooper A., et al. Notes from the field: COVID-19 vaccination coverage among persons experiencing homelessness - Six U.S. Jurisdictions, December 2020-August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1676–1678. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7048a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danish Health Authority. The Danish Vaccination Programme Against COVID-19. 2021. https://www.sst.dk/-/media/English/Publications/2021/Corona/Vaccination/The-Danish-Vaccination-Programme-Against-COVID-19.ashx?la=en&hash=C5AC701C8D17 412ABA3B1871CF2BF2B90B1353E4. Accessed 19 December 2021.

- 16.Our World in Data. Statistics and Research Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations. 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations?country=OWID_WRL. Accessed 15 November 2021.

- 17.Patel M.K. Booster doses and prioritizing lives saved. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2476–2477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2117592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindholt M.F., Jørgensen F., Bor A., Petersen M.B. Public acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines: cross-national evidence on levels and individual-level predictors using observational data. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazereel V., Vanbrabant T., Desplenter F., et al. COVID-19 vaccination rates in a cohort study of patients with mental illness in residential and community care. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.805528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Picker L.J., Dias M.C., Benros M.E., et al. Severe mental illness and European COVID-19 vaccination strategies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mors O., Perto G.P., Mortensen P.B., et al. The danish psychiatric central research register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:54–57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen S.F., Hjorthøj C.R., Erlangsen A., Nordentoft M. Psychiatric disorders and mortality among people in homeless shelters in Denmark: a nationwide register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377:2205–2214. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60747-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Statistics Denmark, Shelters, 2020. https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/dokumentation/documentationofstatistics/shelters

- 24.Statistics Denmark. Imprisonments 2020. https://www.dst.dk/Site/Dst/SingleFiles/GetArchiveFile.aspx?fi=2221784977&fo=0&ext=kvaldel. Accessed 20 November 2020.

- 25.Ministry of the Interior and Housing. Tilbudsportalen. 2021. https://tilbudsportalen.dk/tilbudssoegning/landing/index. Accessed 8 August 2021.

- 26.Schmidtl M., Schmidt S.A., Sandegaard J.L., Ehrenstein V., Pedersen L., Sørensen H.T. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–490. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Momen N.C., Plana-Ripoll O., Agerbo E., et al. Association between mental disorders and subsequent medical conditions. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1721–1731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pottegård A., Schmidt S.A.J., Wallach-Kildemoes H., Sørensen H.T., Hallas J., Schmidt M. Data resource profile: the danish national prescription registry. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw213. 798-f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voldstedlund M., Haarh M., Mølbak K. The Danish Microbiology Database (MiBa) 2010 to 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014;19 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.1.20667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grove Krause T., Jakobsen S., Haarh M., Mølbak K. The Danish vaccination register. Euro Surveill. 2012;17 doi: 10.2807/ese.17.17.20155-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothman J.K., Greenland S., Lash LT. 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, USA: 2008. Modern Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 33.FRA: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Coronavirus pandemic in the EU - Fundamental rights implications: Vaccine rollout and equality of access in the EU. 2021. https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2021-coronavirus-pandemic-eu-bulletin-vaccines_en.pdf. Accessed 2 January 2022.

- 34.Mazereel V, Vanbrabant T, Desplenter F, De Hert M. COVID-19 vaccine uptake in patients with psychiatric disorders admitted to or residing in a university psychiatric hospital. The Lancet Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.World Health Organization. WHO/Europe shows high rates of COVID-19 vaccination in prisons. 2021. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/prisons-and-health/news/news/2021/7/whoeurope-shows-high-rates-of-covid-19-vaccination-in-prisons. Accessed 4 January 2022.

- 36.Fazel S., Geddes J.R., Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529–1540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fazel S., Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet. 2011;377:956–965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.