Abstract

The hippocampus interacts with the neocortical network for memory retrieval and consolidation. Here, we found the lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC) modulates learning-induced cortical long-range gamma synchrony (20–40 Hz) in a hippocampal-dependent manner. The long-range gamma synchrony, which was coupled to the theta (7–10 Hz) rhythm and enhanced upon learning and recall, was mediated by inter-cortical projections from layer 5 neurons of the LEC to layer 2 neurons of the sensory and association cortices. Artificially induced cortical gamma synchrony across cortical areas improved memory encoding in hippocampal lesioned mice for originally hippocampal-dependent tasks. Mechanistically, we found that activities of cortical c-Fos labeled neurons, which showed egocentric map properties, were modulated by LEC-mediated gamma synchrony during memory recall, implicating a role of cortical synchrony to generate an integrative memory representation from disperse features. Our findings reveal the hippocampal mediated organization of cortical memories and suggest brain-machine interface approaches to improve cognitive function.

Subject terms: Cortex, Neural circuits, Hippocampus

Hippocampal lesioned mice form new memories. Here, the authors show the lateral entorhinal cortex modulates learning-induced cortical long-range gamma synchrony in a hippocampal-dependent manner and artificially induced cortical gamma synchrony across cortical areas improved memory encoding in hippocampal lesioned mice.

Introduction

Hippocampus (HPC) is believed to retain recent memories and gradually consolidate them into remote memories by interacting with the neocortex1,2. Hippocampus (HPC) is also involved in the retrieval of memories by reinstating patterns of cortical activity3–5. Conflicting hypotheses about how the interactions between HPC and neocortex contribute to memory storage and retrieval remain. The standard memory consolidation hypothesis proposes HPC transiently stores the memorized information6, while the memory indexing theory argues that HPC only maintains the pointers to memories stored in the neocortex7,8. Decades of researches revealed that HPC and its adjacent regions, including subiculum, medial and lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC), are tightly connected brain structures. While the medial entorhinal cortex encodes spatial information9, the LEC is critical to associated memory10–12. How the information is stored or modulated by the HPC and associated structures remains an open question.

Cortical activities are critical for learning and memory. For example, immediate early gene expression marked neurons are identified as elements of the memory engrams13, which are responsive to a specific context. The reactivation of engram causally induces memory retrieval14,15. Memory engrams are also found in brain-wide cortical regions, including prefrontal cortex, retrosplenial cortex, and other cortices4,16,17. During memory formation and retrieval, a small population of neurons distributed in layer2 (L2) of neocortex showed engram-like response properties16–18. Such distributed cortical hubs may constitute a brain-wide neural network for memory storage19.

Besides engram activities, oscillatory activities in neocortex have long been implicated in mnemonic functions. Oscillatory brain waves are engaged in high-level cognitive function20–22 and may conduct communication functions across brain regions23 with unknown neural mechanisms24–26. For example, cortical theta waves are phase synchronized to hippocampal theta and are related to the cortical gamma power27,28. In humans (note the difference of frequency definition, rodent: theta, 4–12 Hz, gamma, ~25–150 Hz; human, theta, 4–8 Hz, gamma, ~30–150 Hz), theta29,30 and gamma31 oscillations show large-scale phase synchronization, which is positively correlated to the performance in memory encoding29 and retrieval31. The short firing delay between neurons during phase synchronization is proposed to strengthen their synaptic connections and to promote the interaction across various cortical regions for cognitive functions32,33. Recently, a report showed that multi-sensory stimuli at gamma frequency ameliorates cognitive function deficits in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)34. However, it was still not clear whether the oscillatory activity causally engaged memory processing in neocortex. In this study, we discovered that upon learning and memory retrieval, long-range gamma synchrony was induced across multiple regions in neocortex, mediating mnemonic functions. While HPC is critical to modulate cortical synchrony during new memory encoding and retrieval, artificially inducing long-range gamma synchrony in neocortex alone restored the capacity of new memory formation and storage in HPC-lesioned animals. These data indicate that cortical networks alone, which are coordinated by long-range gamma synchrony, are able to store and retrieve hippocampal-dependent memories, such as spatial or contextual memories. Our observations suggest that the HPC-LEC complex modulates cortical memory units by providing synchronized oscillatory potentials to coordinate memories and implicate approaches to treat memory defective diseases.

Results

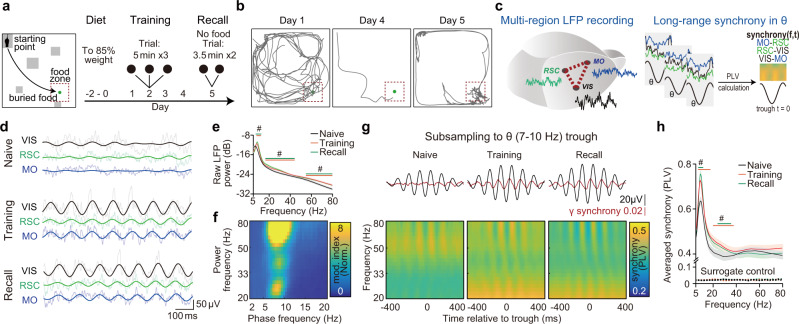

Learning-induced cortical long-range gamma synchrony is coupled to the theta rhythm

First, we surveyed the multi-regional cortical synchronization during a spatial memory task (Fig. 1). Mice were trained to forage buried food (reward) in a sandbox with glass blocks (place cues) for 4 days (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a). In recall trials (day 5), trained mice preferred to search and dig within the food zone, indicating successful memory retrieval (Fig. 1b). We recorded the local field potential (LFP) signals simultaneously from superficial layers of multiple cortices, including secondary motor cortex (MO, AP: −1 mm, ML: −0.7 mm, DV: −0.25 mm), primary visual cortex (VIS, AP: −3 mm, ML: −3 mm, DV: −0.25 mm) and retrosplenial cortex (RSC, AP: −3 mm, ML: −0.7 mm, DV: −0.25 mm, dorsal RSC) (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1b) to study the coordination between motor, visual and spatial information related regions in this task. Inter-cortical projections have been identified between those cortical regions35–37. It has been reported that spatial navigation induces a strong elevation of theta LFP power in HPC38,39. Similarly, we found that the recorded regions showed a higher level of cortical theta (7–10 Hz) and gamma (low gamma: 20–40 Hz, high gamma: 60–80 Hz) oscillation power in the maze than that in homecage (Fig. 1d, e, Supplementary Fig. 1c). While, the cortical oscillatory powers were correlated to the animals’ locomotion (Supplementary Fig. 1e), as reported in HPC40, we found that learning specifically induced the coupling of gamma power to the theta phase during encoding and recall trials (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 3), akin to the results reported in HPC41.

Fig. 1. Learning-induced cortical long-range gamma synchrony is coupled to the theta rhythm.

a A schematic of the spatial memory task. Mice were trained to find the place of hidden food (buried in sands) for 4 days. Recall trials were set on day 5 without any food reward. The arena was designed with landmarks (gray blocks) and buried food (green dot). Mice start exploring from the starting point in all trials. b Representative trajectories of one mouse during learning and recall. c Simultaneously recording of LFPs from three distinct cortices during the task (left) and calculation of phase-synchrony spectrogram by subsampling LFPs to theta trough (right). d Representative LFP raw traces (tint lines) and filtered traces (theta (θ) band, 7–10 Hz, dark lines) from three recording sites at different stages of the task. Here training shows the data from the first day of training, same as the following graphs. See results for each region for each day in the supplementary Fig. 1c. e, f Theta and gamma power increased in training/recall trials and the gamma power was coupled to cortical theta phase (78 electrodes from 28 mice, NMO = 26, NRSC = 26, NVIS = 26). e Averaged raw cortical LFP power from three regions of different trials. Encoding showed here is data from training day1. Significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA followed by false discovery rate (FDR) corrected multiple comparisons at each frequency comparing with data of homecage trail. The trial factor but not the frequency factor was repeatedly measured. Statistical significant frequency range (q < 0.05) is noted on the graph in corresponding colors. f Phase-power modulation index comodulograms of training, averaged from all regions. (See comodulograms of each region for each day and corresponding quantification in Supplementary Fig. 3). Modulation index was normalized by the element-wise division of the raw comodulogram by surrogated control. g, h Theta and gamma synchrony elevated in training/recall trials and the gamma synchrony was coupled to cortical theta phase (72 electrode pairs from 28 mice. NMO-RSC = 24, NRSC-VIS = 24, NMO-VIS = 24). g Gamma synchrony was specifically coupled to theta phase during training and memory recall. Top, averaged theta wave (black) and 30 Hz cortical synchrony (red). Bottom, averaged phase(theta)-synchrony(gamma) spectrogram from all pairs. Each pixel of the spectrograms showed averaged synchrony of all pairs. h Comparison of averaged overall synchrony in three kinds of trials (See result for each pair for each day in the supplementary Fig. 1d. q < 0.05, FDR corrected, significantly changed frequencies were noted on the graph).# q < 0.05, Shadow of line plot shows S.E.M.

By subsampling LFPs to theta trough and calculating the synchrony (indicated by phase-locking value, PLV) between each cortical area of interest (Fig. 1c, see details in method), we found low gamma synchrony between each pair of the recording electrodes (pairwise PLV between MO, RSC, and VIS) became stronger during training and recall than that in the resting state. The cortical long-range gamma synchrony was coupled to theta phase (Fig. 1g, h, Supplementary Fig. 1d). In contrast to the power of theta and low gamma oscillation, the low gamma synchrony was not modulated by the locomotion speed in all conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1f), suggesting the cross-regional synchrony at gamma band might represent a moving-independent feature of the network dynamics in memory encoding and retrieval trials.

HPC-LEC complex mediates memory associated long-range cortical gamma synchrony

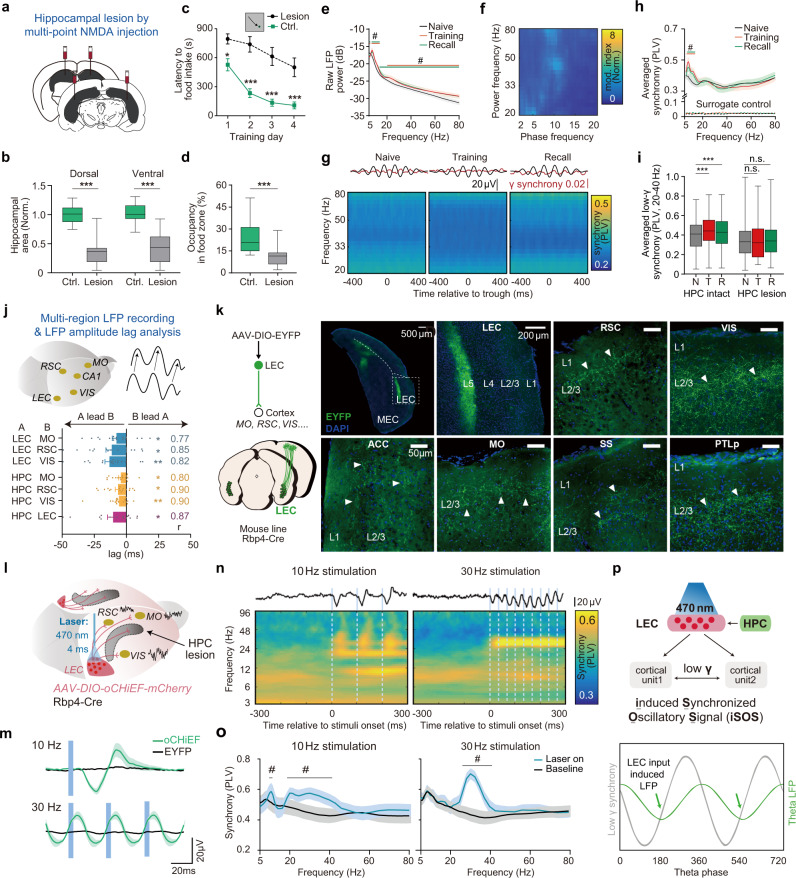

Because the HPC is closely involved in the modulation of theta waves in the brain20,27,39, we asked if the cortical gamma oscillation during memory processing is modulated by HPC. In the loss-of-function test, we examined the behavioral and oscillation changes by a neurotoxic hippocampal lesion in the spatial memory task. When both the dorsal and ventral parts of HPC were damaged (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 2a, b), HPC-lesioned mice spent significantly longer time to find the food and learned much slower than the control group to obtain the food during the learning phase of the spatial memory task (Fig. 2c). In the probe trial to test memory retrieval, compared with the control group, HPC-lesioned mice did not prefer to search within the food zone (Fig. 2d). These results indicated a strong memory deficit in these mice.

Fig. 2. HPC-dependent long-range cortical gamma synchrony is regulated by layer 5 LEC cortical projects and restored by iSOS in HPC-lesioned mice.

a, b Effective bilateral hippocampal lesion in mice by multipoint NMDA injection. a Experimental scheme. b Quantification of the hippocampal residue size. (NControl mice = 14; NHPC-lesioned = 15; Dorsal: two-sided t-test, t(27) = 7.9; P < 0.0001; Ventral, two-sided t-test, t(27) = 6.8, P < 0.0001). c Learning curves show impairment of HPC-lesioned mice in the spatial memory task (NControl mice = 24; NHPC-lesioned = 15; ANOVA, Time factor: F(3, 148) = 12.61, P < 0.0001. Group factor: F(1, 148) = 87.7, P < 0.0001; Interaction, F(3, 148) = 1.484, P = 0.2213; Bonferroni post-hoc test, PDay1 = 0.0111, PDay2 < 0.0001, PDay3 < 0.0001, PDay4 < 0.0001). d HPC-lesioned mice did not prefer the food zone in the probe trials (same mice number as (c), two-sided t-test, t(37) = 4.1, P = 0.0002). e, f Theta and gamma power increased in training and recall trials while gamma power was no longer coupled to cortical theta phase in HPC-lesioned mice (35 electrodes from 12 mice, NMO = 11, NRSC = 12, NVIS = 12). Here training shows the data from the first day of training, same as the following graphs. See results for each region for each day in the supplementary Fig. 2c. e Averaged raw cortical LFP power from three regions of different trials of HPC-lesioned mice (q < 0.05, FDR corrected, significant frequencies were noted on the graph). f Phase-power modulation index comodulograms of training of HPC-lesioned mice, averaged from all regions. g, h Neither the coupling between gamma synchrony and cortical theta phase (Fig. 1g) nor the elevation of long-range cortical synchrony (Fig. 1h) can be detected during training and memory recall in HPC-lesioned mice (34 electrode pairs from 12 mice. NMO-RSC = 11, NRSC-VIS = 12, NMO-VIS = 11). g Cortical gamma synchrony no longer coupled to the cortical theta phase in HPC lesion mice. Top, averaged theta wave (black) and 30 Hz cortical synchrony (red). Bottom, averaged phase(theta)-synchrony(gamma) spectrogram from all pairs. h Comparison of averaged overall synchrony in three kinds of trials (q < 0.05, FDR corrected, significant frequencies were noted on the graph. See raw power, synchrony, comodulograms of each regions for each day and corresponding quantification in Supplementary Figs. 2–3). i Comparison of the overall low gamma synchrony between HPC intact mice and HPC lesion mice across the training process. N, naive; T, training day1; R, recall. (same data as Fig. 1g–h and Fig. 2g–h. Two-way ANOVA, FInteraction (2,208) = 9.56, P < 0.0001, FLesion vs. Intact (1,204) = 3.406, P = 0.0678; FNaive vs. Training vs. Recall (2,208) = 5.705, P < 0.0001. Bonferroni post-hoc test, HPC intact: PTraining vs. Naive < 0.0001, PRecall vs. Naive < 0.0001). j Top, multi-region LFP recording and diagram for theta oscillation amplitude-based cross-correlation analysis. Bottom, dHPC theta lead LEC and LEC theta lead theta of cortical regions in training trials (training day1). Correlation coefficients of the max lag are noted on the right. (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, two-sided, compared to 0. NLEC-MO = 18, NLEC-RSC = 18, NLEC-VIS = 18, NdHPC-MO = 17, NdHPC-RSC = 17, NdHPC-VIS = 17, NdHPC-LEC = 16 from 19 mice). See lag summary of other learning state in Supplementary Fig. 6. k Efferent axons from L5 neurons of LEC were detected in a wide range of cortical areas in L2/3, including, MO, RSC, VIS, SS, PTLp (Posterior parietal cortex) and ACC (Anterior cingulate cortex). Axons were labeled by EYFP via virus (AAV2/9-DIO-EYFP) injection in LEC of Rbp4Cre mice. Scale bar, 50 μm. (three mice brain were sectioned and show similar results, represnetive images here are from one of them). l–m Artificial co-activation of LEC axons induced long-range cortical gamma synchrony. To detect the pure effect of optogenetic stimulation, cell body activation was done in homecage using awake HPC-lesioned mice to minimize the task-engaged cortical synchrony. l 470 nm laser-activated neurons expressing oCHiEF-mCherry in LEC (4 ms per pulse) induced synchronization oscillatory signals (iSOS) of LFP in multiple cortical areas simultaneously. m Blue light stimulation at either 10 Hz or 30 Hz in LEC could induce LFP responses simultaneously in MO, VIS and RSC in oCHiEF-expressing mice (green lines) but not EYFP expressing mice (oCHiEF group: n = 21 electrodes, including electrodes in RSC, MO, and VIS, EYFP group: n = 14 electrodes, including electrodes in RSC, MO, and VIS, lines are the averaged evoke potential of RSC, MO, and VIS). The evoked potential period (~36 ms, gamma frequency, ~30 Hz) did not change across stimuli frequencies. See surface axonal stimuli in Supplementary Fig. 9a–b. n Averaged cortical synchrony heatmap before and after stimulation. Top black lines, averaged LFP traces for each stimulation. Blue lines, laser stimuli. The spectrogram is the average of all cortical pairs including, RSC-MO, RSC-VIS, and VIS-MO. o Quantification of panel n. Baseline, averaged PLV before laser stimulation. Laser on, averaged PLV at 10–50 ms after each pulse, significant frequency ranges (lines above) lie at gamma band (q < 0.05, FDR corrected, 16 electrode pairs). p Illustration summarizes that long-range gamma synchrony is mediated by HPC-LEC and coupled to the theta-rhythm during memory encoding and retrieval (top). Endogenous synchronized LEC axonal activation may induce cortical synchronization oscillatory signals (iSOS), which is phase lock to theta phase, during memory encoding and retrieval (bottom). Shadow of lines and error bar shows lines show S.E.M. ***P < 0.001, #q < 0.05. For all box plot, whiskers show min and max, box shows 25th, median and 75th percentile.

In addition to the behavioral deficit, we observed increased theta and gamma power during memory encoding and recall, but the oscillation powers were substantially reduced compared to those in normal mice (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 2e). Prominently, learning-induced cortical theta-gamma coupling was abolished in HPC-lesioned mice (Figs. 1f vs. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 3 for all kinds of trials). Consistently, the coupling of phase synchrony was reduced significantly (Fig. 2g). The learning-induced cross-regional gamma synchrony vanished in those HPC-lesioned mice (Fig. 2h, i). Thereby, HPC is required for spatial memory and is essential for the modulation of learning-associated cortical oscillation.

LEC is the gateway from the HPC to the cortex42 and is also essential for memory encoding. To dissect the relationship between HPC, LEC and other cortical areas, we recorded electrical signals and calculated their synchronies in RSC, VIS, MO, LEC (AP: −4.35 mm, ML: −4.0 mm, DV: −4.0) and dorsal HPC (dHPC-CA1, AP, −2 mm; ML, −1.5 mm; DV, −1.3 mm) simultaneously during the spatial memory task (Supplementary Fig. 2j). While the theta power of LEC and dHPC (CA1 region) was significantly increased during learning, the cross-regional synchronies between LEC/dHPC and CTX (MO, RSC, and VIS) were detected at theta band (Supplementary Fig. 4). We found that the power of cortical oscillation (in MO, RSC, and VIS) at gamma band were coupled to the theta rhythm in LEC. However, gamma power in LEC did not couple to the cortical theta oscillation (Supplementary Fig. 5). Thus, the theta rhythm in LEC modulates gamma oscillation across multi-sensory cortices, but not in the reverse order. Moreover, the cross-correlation analysis43 showed that theta rhythm in dHPC/LEC occurred earlier than that in cortical regions during learning (Fig. 2j). While HPC-LEC communicated via theta oscillation44–46, we found that dHPC theta wave led theta waves in LEC (Fig. 2j, Supplementary Fig. 6).

To rule out the possible influence of volume conduction in our synchrony analysis, we directly induced a current sink in one of five brain regions (CA1, LEC, RSC, VIS, MO) and quantified the evoked amplitude (volume conduction) of potentials in other brain regions (Supplementary Fig. 7), we found that <1% of the source LFP could be detected in distant regions, so the volume conduction has a negligible effect on the observed cortical synchrony phenomenon. These data suggest the learning-associated cortical long-range gamma synchrony is regulated by HPC.

LEC layer 5 neurons project to widely distributed neuron ensembles in layer 2 of visual cortex and association cortices to induce synchronized gamma oscillations

Next, we found that LEC projects to L2/3 of multiple cortical areas. We used virus approaches to drive the expression of EYFP in L5 Rbp4Cre-derived neurons (Rbp4 is specifically expressed in L5 neurons) in LEC to trace their efferent fibers and found that LEC connected to many cortices including PTLp (posterior parietal cortex), ACC (Anterior cingulate cortex), SS (Somatosensory cortex), RSC, MO and VIS (Fig. 2k). Moreover, besides cortical axonal sprouting in L2/3, the anterograde trans-synaptic tagging in LEC also confirmed the projections from LEC L5 neurons to cortical L2/3 neurons. After injecting anterograde tracer virus (AAV2/1: hSyn-Cre) to trans-synaptically express Cre protein in the direct downstream neurons47 of LEC in the reporter mouse line (Ai9 strain), we observed sparsely labeled neurons mainly located in L2/3 of the VIS, SS, MO and many other cortical regions (Supplementary Fig. 8). Hippocampus (HPC) does not have widespread projections to cortices. Both dorsal CA1 and ventral CA1 project to LEC deep layers46,48,49. Therefore, those observed LEC projections in numerous cortical areas, which are originated from deep LEC neurons to L2/3 neurons, are fundamental for the signals from the HPC complex to reach cortical areas simultaneously. This anatomical structure implicates the role of LEC in mediating the HPC-modulated cortical synchronization.

To further test if the LEC L5 inter-cortical axons play a role in the long-range cortical synchrony for memory encoding and retrieval, we used virus approaches to drive the LEC expression of oCHiEF, which allows fast optogenetic control of neural activity50. We stimulated the LEC efferent fibers from the cortical surface to directly control the LEC targeted cortical neurons or stimulated the LEC cell bodies to test if it was able to affect cortical synchrony indirectly in HPC lesioned mice (Fig. 2l, Supplementary Fig. 9a). While HPC-lesioned mice were recorded in the homecage, LFP signals were collected simultaneously from MO, VIS, and RSC. Activating the cell bodies of L5 LEC neurons or their efferent fibers induced reliable cortical LFP signals in recorded cortices (Fig. 2m, Supplementary Fig. 9b). Upon optogenetic activation in LEC (470 nm, 4 ms), LFP response latencies were similar across cortical regions (MO: 25.50 ± 1.87 ms, RSC: 25.25 ± 1.46 ms, VIS: 25.40 ± 2.11 ms, Supplementary Fig. 9d, e). The engaged actives showed significant bursts on low gamma band, no matter the frequency of the optic stimuli (Fig. 2n). Such LEC-mediated cortical oscillation in the low gamma band is an intrinsic property of each cortical unit, as each activation-induced LFP response lasted for ~36 ms (corresponding to low gamma frequency). Such phenomenon was observed by either activation of LEC-axons or activation of the L5 cell bodies in LEC (Fig. 2o). As a result of the simultaneous activation for each cortex, long-range cortical synchrony was induced, especially at the low gamma band.

Consistent with this view, LEC stimuli at 25 Hz and 30 Hz induced a much stronger cross-regional cortical synchrony at the gamma band than that under the stimulus at 10 Hz (Fig. 2n, o; Supplementary Fig. 9f–i). The enhanced signal was probably due to the resonance. The LEC-stimuli-induced synchrony on the low gamma band reached the peak at ~30 ms, the time of which is similar to the delay time occurred in the learning period between theta trough and the peak of gamma synchrony (Supplementary Fig. 9j, k). These data suggested the stimuli-induced PLV rhythmicity was similar to endogenous PLV rhythmicity from theta modulation during memory encoding and retrieval. While HPC damage abolished the theta-coupled gamma synchrony in the neocortex, applying optogenetic stimuli on L5 LEC axon terminals was able to generate the induced-Synchronized-Oscillatory Signal (iSOS) to reestablish the long-range cortical synchrony in HPC-lesioned mice (Fig. 2p).

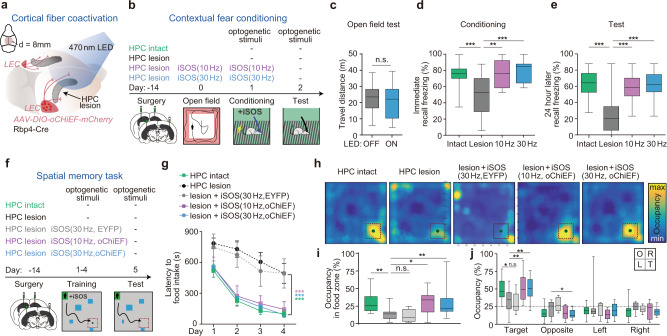

Long-range cortical iSOS rescued memory deficits in HPC-lesioned mice for the contextual fear memory task

Next, we asked if the LEC-mediated gamma synchrony in neocortex is functionally critical for the HPC-mediated contextual fear memory. In mice with bilateral hippocampal lesions, we applied artificial iSOS (470 nm, LED) through a cranial window (d = 6 mm) by activating the oCHiEF-expressing LEC axons in the upper layers of MO, VIS, SS, PTLp, and RSC (Fig. 3a) to simultaneously activate the circuits from LEC to the target cortices. After applying iSOS during learning trials to restore the long-range gamma synchrony (Fig. 2n, o), we tested the behavioral performance of mice in the contextual fear memory task (Fig. 3b). Activating LEC axons with iSOS did not affect locomotor activities, freezing, or exploring levels in those mice in the open field box (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). In the contextual fear conditioning task after a weak foot-shock, while HPC-lesioned mice showed significantly reduced freezing, the iSOS groups of HPC-lesioned mice (10 Hz or 30 Hz, only in training trials) showed no impairment both in the immediate recall trial and in the 24 h recall trial (Fig. 3d, e). In the control experiment, rescued mice showed the same freezing level in a unfamiliar context as HPC intact mice, indicating rescued mice have the same memory fidelity as normal mice (Supplementary Fig. 10c–f). These data indicated that the iSOS application induced a full rescue of encoding and storage of long-term contextual fear memory in mice with hippocampal lesion.

Fig. 3. Cortical application of iSOS rescued memory deficits in HPC-lesioned mice.

a–e Artificial iSOS in neocortex during training can rescue fear memory deficits in HPC-lesioned mice. a Scheme of the co-activation LEC fiber during encoding. The iSOS were induced by LED on cortical surface to activate oCHiEF-expressing widespread axons from LEC L5. Activation of cortical fibers but not LEC cell bodies is to avoid the unspecific activation of circuits from LEC to other brain regions. b Flow of the behavioral experiment. All four groups of mice received contextual fear conditioning (CFC) training. Two groups of HPC-lesioned mice were given iSOS during training trials. Long-term memory was tested 24 h later without iSOS. HPC intact group means no HPC lesion, no iSOS applied and no virus infected. c Travel distance of open field test upon given iSOS or not. (HPC-lesioned mice, N = 13, two-sided paired t-test, t(12) = 1.6, P = 0.1449). d Immediate freezing after foot shock (NHPC intact = 15, NHPC lesion = 19, NiSOS-10Hz = 8; NiSOS-30Hz = 8; ANOVA, F(3, 46) = 9.1, P < 0.0001; Bonferroni post-hoc test, PControl vs. HPC-lesion = 0.0005, PiSOS-10Hz vs. HPC-lesion = 0.0035, PiSOS-30Hz vs. HPC-lesion = 0.0005). e Memory test in the conditioned context (same mice as d, ANOVA, F (3, 46) = 13.5, P < 0.0001; Bonferroni post-hoc test, PControl vs. HPC-lesion < 0.0001, PiSOS-10Hz vs. HPC-lesion < 0.0001, PiSOS-30Hz vs. HPC-lesion < 0.0001). f–j Artificial iSOS rescued spatial memory deficit in HPC-lesioned mice. f Flow of the behavioral experiment. g Learning curves for the spatial memory task (mice number: NHPC-intact = 24, NHPC-lesion = 15, NiSOS (30Hz,EYFP) = 6, NiSOS (10Hz,oCHiEF) = 11; NiSOS (30Hz,oCHiEF) = 22; ANOVA, Time factor: F(3, 219) = 52.5, P < 0.0001; Group factor: F(4, 73) = 10.6, P < 0.0001; Interaction, F(12, 219) = 1.4, P = 0.1453; Bonferroni post-hoc test, PHPC-intact vs. HPC-lesion < 0.0001, P iSOS (30Hz,EYFP) vs. HPC-lesion > 0.9999, P iSOS (10Hz,oCHiEF) vs. HPC-lesion < 0.0001, P iSOS (30Hz,oCHiEF) vs. HPC-lesion < 0.0001). h Averaged occupancy maps for memory recall in day5. i Quantification of occupancy in food zone (same mice as g. ANOVA, F(4, 73) = 5.0, P = 0.0012; Bonferroni post-hoc test, PHPC-intact vs. HPC-lesion = 0.0048, P iSOS (30Hz,EYFP) vs. HPC-lesion > 0.9999, P iSOS (10Hz,oCHiEF) vs. HPC-lesion = 0.0243, P iSOS (30Hz,oCHiEF) vs. HPC-lesion = 0.0098). j Quantification of occupancy in four quadrants (same mice as g ANOVA for each quadrant, Target quadrant: F(4, 73) = 5.0, P = 0.0013; Bonferroni post-hoc test, PHPC-intact vs. HPC-lesion = 0.0159, P iSOS (30Hz,EYFP) vs. HPC-lesion = 0.9803, P iSOS (10Hz,oCHiEF) vs. HPC-lesion = 0.0102, P iSOS (30Hz,oCHiEF) vs. HPC-lesion = 0.0070, Opposite quadrant: F(4, 73) = 4.3, P = 0.0038, Bonferroni post-hoc test, P iSOS (30Hz,oCHiEF) vs. HPC-lesion = 0.0190; Left quadrant: F(4, 73) = 1.4, P = 0.2529; Right quadrant: F(4, 73) = 1.0, P = 0.4043). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Each dot represents one mouse. Error bar shows lines shows S.E.M. For all box plot, whiskers show min and max, box shows 25th, median and 75th percentile.

Long-range cortical iSOS rescued memory deficits in HPC-lesioned mice in the spatial memory task

In the task to retrieve the food in a maze (Fig. 3f), HPC-lesioned mice showed significant learning impairment both in the initial phase of training and in the progressive learning days. The iSOS-induced groups of the HPC-lesioned mice (restoring the long-range gamma synchrony during the learning phase) showed a full capacity to retrieve food in term of learning speed and the short latency to reach the spot, similar to those in the HPC-intact group (Fig. 3g). In contrast, in a control experiment, no rescue effect was observed when applying iSOS to the HPC-lesion mice expressing EYFP (Fig. 3g). In the memory retrieval trials, when iSOS was not applied, the HPC-lesioned mice trained under iSOS application showed a strong preference to the food zone (Fig. 3h), similar to the HPC-intact group. While, HPC-lesioned mice showed a significant reduction of occupation time in the food zone (Fig. 3i), indicating long-range gamma synchrony during learning was critical for memory encoding and storage. HPC-lesioned mice after iSOS treatment spent more time in the target quadrant of the maze (Fig. 3j), suggesting they were able to form and retrieve the spatial information of the hidden food.

These results showed a complete recovery of HPC-lesioned mice to acquire and retrieve new spatial memories after engaging cortical long-range gamma synchrony during learning. Taken together, both the artificial iSOS and LEC axon-mediated long-range gamma synchrony are able to coordinate cortical units to store the contextual and spatial information in mouse neocortex, allowing a successful memory recall during the test trial.

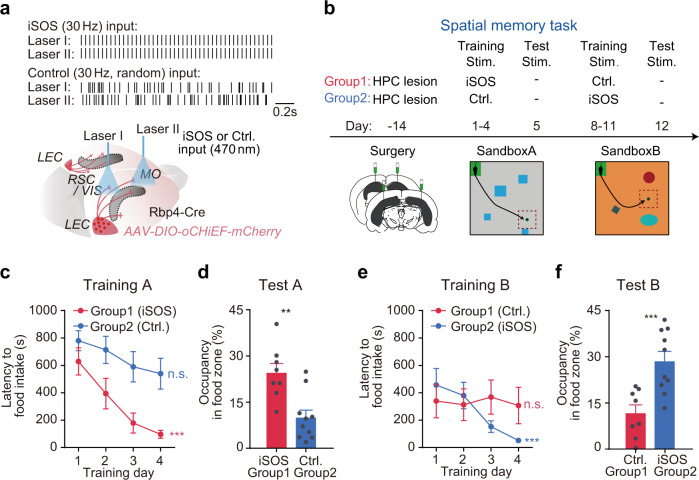

The cortical iSOS, but not asynchronous LEC axonal activation rescued spatial memory deficits in HPC-lesioned mice

To ask whether the synchronization of cortical units or the activation of LEC axons is essential for the hippocampal-dependent cortical memory storage, we performed a double dissociation test. To this end, two groups of HPC-lesioned mice were trained sequentially either with the iSOS (30 Hz pulses by two synchronized laser beams) or asynchronous LEC axonal activation (two laser beams with asynchronous stimuli on distinct areas). We used virus approaches to express oCHiEF in LEC L5 Rbp4Cre-derived neurons (Fig. 4a) and stimulated LEC-to-L2 axons on the cortical surface of MO and VIS (or RSC) during sequential learning for two place memory tasks in two distinct boxes (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 1a). In great contrast to the synchronized signal (iSOS), applying asynchronous laser stimuli on neocortex increased cortical LFP power (Supplementary Fig. 11a, b) and reduced the cross-regional synchrony (~10–100 Hz, Supplementary Fig. 11c, d).

Fig. 4. Application of iSOS, but not asynchronous cortical axonal activation rescued spatial memory deficits in HPC-lesioned mice.

a, b Scheme of the double dissociation experiment. a During training, LEC-axons in two cortical areas in HPC lesioned mice were activated by two independent fibers with either synchronized signal (iSOS30Hz) or asynchronous signal (Ctrl. random pulses of each, same total pulse number). b HPC-lesioned mice were divided into two groups, both of which underwent the sequential maze tasks in two boxes in the same order. Group 1 mice were only applied with cortical iSOS during learning in the first maze and group 2 mice were only applied iSOS in the second maze. c Learning curves for two groups in CtxA. (NGroup1 = 8; NGroup2 = 10; ANOVA, Time factor: F(3, 48) = 11.3, P < 0.0001; Group factor: F(1, 16) = 8.2, P = 0.0113; Interaction, F(3, 48) = 1.3, P = 0.2976; Bonferroni post-hoc test, PGroup1:Day4 vs. Day1 < 0.0001, PGroup2: Day4 vs. Day1 = 0.0689). d Probe trials of the two groups in CtxA (two-sided t-test, t(16) = 3.8, P = 0.0017). e Learning curves for two groups in CtxB (ANOVA, Time factor: F(3, 48) = 4.7, P = 0.0056; Group factor: F(1, 16) = 0.36, P = 0.5582; Interaction, F(3, 48) = 4.7, P = 0.0062; Bonferroni post-hoc test, P Group1:Day4 vs. Day1 > 0.9999, PGroup2: Day4 vs. Day1 < 0.0001). f Probe trials of the two groups in CtxB (two-sided t-test, t(16) = 3.9, P = 0.0013). Each dot represents one mouse. Error bar shows lines shows S.E.M.

In box A, when group 1 mice were given iSOS and group 2 were applied with the asynchronous signal, group 1 mice showed a quick reduction of the latency to retrieve the food during 4 days’ training. In contrast, group 2 mice learnt much slower than group 1 (Fig. 4c). In the test trial of memory recall in box A, the group 1 mice spent significantly longer time searching in the food zone than that of the group 2 mice (Fig. 4d). Later on, in box B, group 2 mice, which now received the iSOS stimuli, improved their performance and significantly reduced their searching time (Fig. 4e). In contrast, group 1 mice, which received the asynchronous signal, did not show improvement in performance during the training period (Fig. 4e). In the probe trial in box B, group 2 mice spent significantly longer time in the food zone than that of the group 1 mice (Fig. 4f). Thus, the long-range cortical synchronization, rather than the LEC axonal activation per se, is essential for spatial memory storage.

Consistent to these observations, in the HPC-intact mice, we found that applying asynchronized signals in multiple cortical regions largely reduced the learning ability in the same task (Supplementary Fig. 11e–g) and mice showed impaired performance on the test trial of memory retrieval (Supplementary Fig. 11h). However, when the asynchronized signals were not given in the same group of mice in a second spatial memory task, their performance appeared normal in learning and memory retrieval, indicating that cortical synchrony is required for the formation of spatial memory in the brain.

Furthermore, as the artificially applied iSOS definitely did not contain any information about the context and the place clue in the task, the fact that those HPC-lesioned mice were still able to encode and retrieve memories about the spot of food location strongly implicates the fact that spatial information was stored and retrieved within the coordinated cortical network, at least in those HPC-lesioned mice. Thereby, given the fact that HPC was critical for memory-engaged cortical synchronies (Fig. 2), one of the essential roles of the HPC and associated structures in memory could be acting as the coordinator to allocate the memory storage in the distributed cortical networks.

Long-range cortical gamma synchrony was tightly coupled to the activation of cortical memory-related neurons during memory retrieval

How does the long-range cortical synchrony modulate memory formation and retrieval? We simultaneously recorded calcium activities in cortical memory-related neurons (engram) in RSC and the LFP synchrony between RSC and VIS in the contextual fear conditioning task. We used virus approaches to express GCaMP6f, a calcium indicator, in cFos-CreER derived memory-related neurons in RSC by TRAP technology51 and used optrode to simultaneously record the LFP and photometry of labeled neurons located in the superficial layer of cortex in free-moving mice (Supplementary Fig. 14a–d). Our previous in vivo imaging study suggest the superficial layer 2 neurons expressing immediate early gene encode context-dependent memories during learning trials16. Mice were injected with tamoxifen 24 h before learning to specifically induce the expression of GCaMP6f in neurons activated during training in context A (CtxA, Supplementary Fig. 12a, b).

The activity of labeled neurons in the same region increased robustly and repeatably in the recall trials when back to the learned context (CtxA), compared to that in the unfamiliar context (CtxB) and in homecage (Supplementary Fig. 12c). in the test trial of memory retrieval, while neurons remained at low activities in the NO-freezing period, the frequency of the calcium events (CEs) in the labeled neuronal ensemble increased significantly at 2 s before the onset of the freezing behavior. The activities of engram neurons in VIS and RSC cortices in the pre-freezing period was significantly higher than those in the freezing period or in the post-freezing period (Supplementary Fig. 12d). We found that during this pre-freezing period, the rising time of calcium signals of labeled neurons of RSC was strongly correlated with the increase of gamma synchrony (Supplementary Fig. 12e, f). In contrast to c-Fos labeled engram neurons, activities of randomly labeled neurons of RSC did not show preference to the memorized context and were not coupled to the LFP synchrony between VIS and RSC (Supplementary Fig. 12g–i).

In another group of mice, we tested the correlation between activity of memory-related cells (labeled on the 4th day of training) and long-range synchrony in the spatial memory task. Similar to the pre-freezing period in the contextual fear task, a pre-exploring phase was set in the spatial memory task: mice were placed in the start region and constrained by a non-transparent door for 1 min before the door was open and mice were then allowed to explore and search for the hidden food (Fig. 5a). Consistent with the results of the contextual fear conditioning task, labeled cells in RSC and VIS showed a higher level of activities, especially during the pre-exploring period in the learned context than those in the unfamiliar context or the homecage conditions (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 13a). Only labeled neurons in the superficial layer (L2, within 200 μm to pia surface), but not deep-layer neurons (L4/5), showed context-specific activation during recall trials (Supplementary Fig. 14e–g). By cross-correlation analysis, comparing the whole time-series of low gamma synchrony with the activities of labeled neurons in RSC or VIS (Fig. 5c, d, Supplementary Fig. 13b, c), we found that such cross-correlation strongly occurred during the pre-exploring phase in recall trails, but not in the homecage trial. Those data indicate the activities of engrams were induced by memory retrieval, particularly in the free recall time when the sensory information of the learned context was not presented yet.

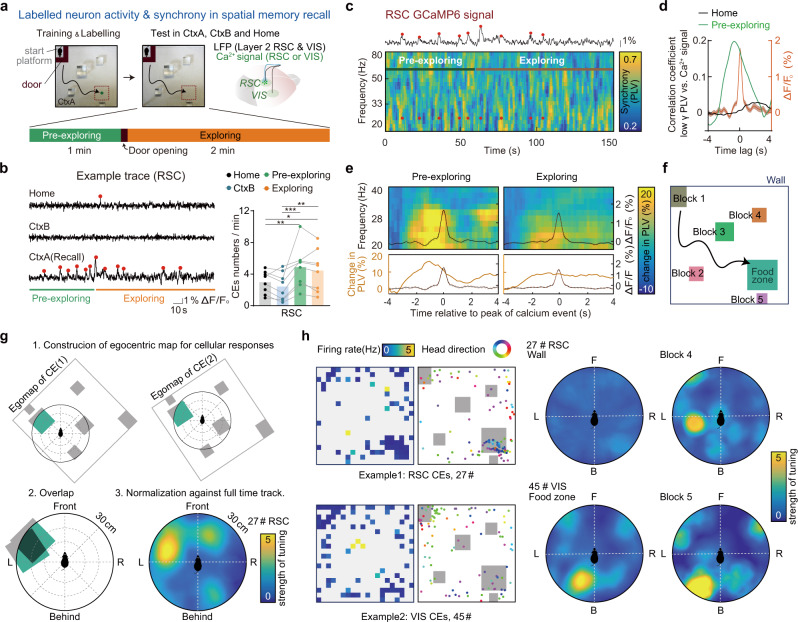

Fig. 5. Activation of the cortical memory-related population was tightly coupled to the long-range cortical gamma synchrony and show egocentric coding to objects in the learned context during memory retrieval.

a–e Cortical gamma synchrony is associated with spatial memory-related neurons activation. a Experiment scheme to monitor the activity of cortical spatial memory-related neurons and the long-range gamma synchrony simultaneously. Activities of memory-related neurons were monitored by calcium signal (GCaMP6f labeled by TRAP using c-Fos-CreER mice during spatial memory task training day4) in RSC or VIS, while LFPs were recorded both in RSC and in VIS. In recall trials (day11), mice were confined on the start platform for 1 min by an L shape door (pre-exploring) before freely exploring in the sandbox (exploring). See other recording details in Supplementary Fig. 14a–d. b Left, examples of RSC calcium signals of labeled neurons. Right, labeled RSC neurons showed context selectivity. Red dots indicate the peaks of the detected RSC calcium events (N = 8 mice, ANOVA, F(3, 15) = 7.1, P = 0.0034, Tukery post-hoc test, PPre-exploring vs. CtxB = 0.007, PPre-exploring vs. Home = 0.0308, PExploring vs. CtxB = 0.0257). c An example of synchrony spectrogram (RSC-VIS) plotted together with calcium signal from labeled RSC neurons, showing the correspondence between engram activity and synchrony. d Cross-correlation analysis. Averaged correlation coefficient between low gamma synchrony and engram activity of RSC (n = 6) in pre-exploring phase (green) and in homecage (black). Orange line, averaged calcium events (n = 263 RSC CEs). e Averaged low gamma synchrony (RSC-VIS) spectrogram. Spectrograms are aligned to each peak (t = 0) of RSC calcium event during the pre-exploring phase or exploring phase. Synchrony was normalized to baseline synchrony of each calcium event (mean PLV from −4s to −3s). The black curve inside the graph shows the averaged curve of all calcium events within pre-freezing or freezing. Bottom, change in synchrony (averaged across low gamma band) and same averaged curve of CEs are plotted for clarity of peak time of the change in synchrony. 133 CEs of RSC within the pre-exploring phase and 263 CEs of RSC within exploring from 6 animals. (VIS calcium signal owns similar properties as RSC, both RSC and VIS signals showed most frequent firing in the pre-exploring phase and coupled to long-range low gamma synchrony. See VIS data in Supplementary Fig. 13). Dash lines plot around the CEs curve show S.D. f–h Labeled neurons in RSC and VIS show egocentric coding to objects in the learned context. f Diagram for definitions of objects in the spatial training context, including entity (walls, block 1–5) and virtual regions (food zone). g Schematic for construction of egocentric object ratemap (EOR) for a specific object, for example, the food zone. h 2D ratemaps of CEs, location of CEs plotted together with head directions (left), and EORs for two examples (right). Firing rate was calculated by total CEs numbers in each bin divided by total time spent in that bin. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

These observations were further confirmed by averaging synchrony near each calcium event. For the CEs in the pre-exploring and the exploring period, gamma synchrony showed peak events ahead of the peak of the CEs in all recorded cortical regions (RSC, Fig. 5e, VIS, Supplementary Fig. 13d). These data indicated that while cortical activities of labeled neurons were context-specific and distributed in different brain regions, long-range gamma synchrony was strongly coupled to the activation of the activities of memory-related neurons, especially during the retrieval of those memories.

Cortical memory-related neurons in RSC and VIS exhibit egocentric coding to objects in the learned context

In fact, to successfully retrieve the food, mice need to refer to a map. Studies have revealed neurons coding place information for allocentric maps in hippocampal formation, i.e., the place cells in HPC and grid cells in the medial part of EC52. Besides, recent discoveries showed neurons coding egocentric information in neocortex during spatial navigation. Such egocentric coding neurons have been detected in LEC53, RSC46, sensory and motor cortices54,55. We speculated that mice navigate in the context also with their egocentric map which may encoded in those c-fos labeled neurons (cortical engram). To this end, we re-analyzed the behavioral data together with the online activity of cortical engram to explore whether the activities encoded the spatial information in an egocentric way. For each recorded memory-related population, we constructed the egocentric object ratemaps (EORs) for each object in the context (see details in methods, supplemental movie 1). Here objects included both real entities and virtual ones, such as the food zone region (Fig. 5f). Particularly, taking the food zone as an example, for each of the detected CEs in the exploring phase of recall, the position of food zone relative to mouse head within 30.0 cm at the rising time point of the CE was built as the egocentric map for this CE. Superposition of egocentric maps for all CEs constructed a raw EOR, then EOR was normalized by dividing the raw EOR in each bin by the ‘EOR’ constructed using all time points during traveling (Fig. 5g). In over half of the labeled ensembles in RSC and VIS, we detected significant egocentric object sensitivity to at least for one object in the context (Fig. 5h, Supplementary Fig. 15a, RSC, n = 4/8; VIS, n = 4/5; in total, 61.5%), called egocentric object ensembles (EOEs). The most frequently responsive object of EOEs was the biggest glass block (block3, probably as the spatial cue in the context, n = 4/13) and the block close to the foodzone (block5, Supplementary Fig. 15a, b). We determined 15 significant EORs in the labeled population from eight mice. Most of the preferred distances were over 15 cm and the tuning angles fell on the contralateral side of the recorded region (Supplementary Fig. 15c, d), implicating they were generated via a sensory input-associated process.

In contrast to objects, the CEs did not show significant egocentric tuning to non-object regions (Supplementary Fig. 15e, f, see details in Method: “Egocentric Tuning to Non-object Regions”), suggesting the egocentric map were encoded via a sensory-driven process. Furthermore, relocation of the landmark objects in the spatial memory task impaired memory retrieval (Supplementary Fig. 16, see details in Method: “Memory Test of Landmark Relocation”), implicating that mice rely on the stored egocentric information to perform this spatial task.

Calcium activities of labeled neurons could show significant egocentric object sensitivity to more than one object, which leads to disperse allocation of spatial specificity, applying reported criteria (Mean Resultant Length, MRL was greater than the 99th percentile of the random distribution of resultants computed following repeated shifted CEs randomizations)54 could result in a lower detection rate. Therefore, to compromise, we applied a loose significance threshold (MRL was greater than the 95th percentile of the random distribution). More than 60% of recorded ensembles were determined to be EOEs. When applying the reported criteria (99th percentile), still 30.7% of recorded ensembles were determined to be EOEs. The significance of egocentric tunings has been further validated by random simulation of the CE events in the moving density space (Supplementary Fig. 15g, h, see details in Method: “Egocentric Significance of Random CE Simulation”). According to the statistical analysis, cortical activities of memory-related neurons reflected the egocentric map-like coding for each landmark within the context. Furthermore, coordination of those representations constituted the entire view about the context, forming an egocentric view of the path to the food pellet.

LEC is critical for memory engram formation and its mediated long-range gamma synchrony is essential for cortical engram reactivation and memory retrieval

Finally, we dissected the role of LEC in mediating the memory-retrieval associated with long-range gamma synchrony and retrieval-induced reactivation of memory-related neurons. We found that optogenetic inhibition of LEC-cortical axons impaired memory retrieval. Optogenetic stimulating (589 nm LED) LEC-cortical axons expressing NpHR-EYFP on the surface of VIS, RSC, and SS induced less freezing in the light-on trials than that in the light-off trials in the conditioned context (Supplementary Fig. 17a–d). Inhibiting LEC axons in a single functional region (~0.5 mm2) did not alter the retrieval behavior (Supplementary Fig. 17e), implicating that loss of LEC-mediated synchrony in individual units of the cortex did not block the retrieval of contextual fear memory. Similarly, in the spatial memory task, when the LEC-L2 axons activities were inhibited during test trial, mice showed a significant reduction of their time spent in the target area in probe trials (Supplementary Fig. 17f–h), indicating LEC-mediated cortical synchrony is essential for the spatial memory retrieval.

Furthermore, in the spatial memory task, we expressed hM4D(Gi), a modified human M4 muscarinic receptor, to inhibit activities in LEC under the control of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO)56, to inhibit activities in LEC under the CNO. Similar to the NpHR mediated inhibition in axon terminals, inhibiting LEC activities by hM4D(Gi) during memory retrieval impaired the preference of mice to the food zone in the recall trial and increased the latency for the mice to reach the food in the retraining trials (Fig. 6a–c). Consistent with the behavioral deficits, inhibition of LEC activity also reduced the frequency of cortical activities of labeled neurons in the pre-exploring phase of recall trials (Fig. 6d, e). Moreover, in the pre-exploring phase, LEC-inhibition induced reduction of reactivation of labeled neurons (Fig. 6e). Consistently, LEC-inhibition induced reduction of VIS-RSC long-range gamma synchrony and triggered a complete abolishment of the coupling between each of the CEs and cortical synchrony (Fig. 6f–h), when aligning the LFP signals to each of the engram calcium event. By correlation analysis, comparing the whole time-series of gamma synchrony with the calcium activities of labeled neurons in RSC and VIS, we found that LEC-inhibition totally abolished the correlation between engram activity and long-range gamma synchrony in the pre-exploring phase (Fig. 6i).

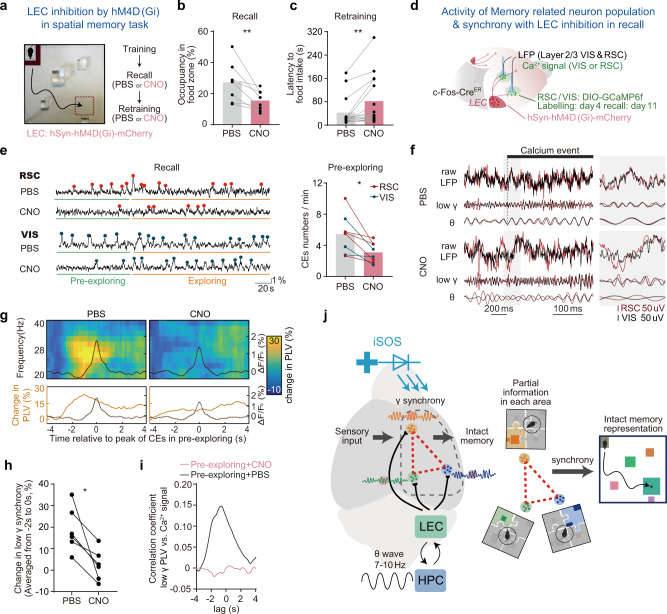

Fig. 6. LEC-mediated long-range gamma synchrony is essential for cortical memory-related neurons reactivation and memory retrieval in HPC-intact mice.

a Experimental scheme for LEC inhibition by hM4D(Gi) in spatial memory recall and retraining to test if LEC is essential for successful memory recall. b–c Inhibition of LEC activity impair memory recall. b Occupancy in the food zone significantly decreased in recall trail (N = 15 mice, two-sided paired t-test, t(14) = 3.5, P = 0.0036). c Latency to the reward in the following retraining trail increased (N = 15 mice, two-sided paired t-test, t(14) = 3.2, P = 0.0067), CNO dosage: 2 mg/kg. d Similar to Fig. 5a, experimental scheme shows calcium signals from labeled neurons (labeled in training day4) and LFPs were recorded simultaneously during memory recall with or without LEC inhibition. e Left, calcium signal examples of labeled neurons in RSC and VIS with or without LEC inhibition. Right, quantification of CEs frequency in pre-exploring phase of memory recall (N total = 8 mice with three recorded in VIS and 5 in RSC, two-sided paired t-test, t(7) = 3.5, P = 0.0105). Red and blue dots indicate the peaks of the detected RSC and VIS calcium events, respectively. f Examples of LFPs around calcium events from the pre-exploring phase of recall trials with PBS and with CNO, the black bar above LFPs indicate the time range from rising time to the peak of the calcium event, illustrating theta (θ) and gamma (γ) LFPs transiently synchronized with zero-phase lag at the rising time of the calcium event while it is not the case in CNO administration recall trial. g Averaged synchrony (RSC-VIS) spectrogram, spectrograms were aligned to each peak of RSC or VIS calcium events in the pre-exploring phase during memory recall with or without LEC inhibition. (NPBS = 90 CEs, NCNO = 75 CEs, from six animals). h Change in low gamma synchrony in panel g (averaged PLV from −2s to 0 s) was quantified for each mouse. LEC inhibition impaired the coupling between engram activity and cortical low gamma synchronization (N total = 6 mice, paired two-sided t-test, t(5) = 3.541, P = 0.0165). i Cross-correlation analysis. Averaged correlation coefficient between low gamma synchrony and RSC or VIS engram activity in pre-exploring phase with CNO administration (red, N = 6 mice) or not (black, N = 6 mice). *P < 0.05. j Model for the mechanism in which long-range cortical gamma synchrony mediates memory encoding and retrieval by HPC/LEC. The illustration shows that the cortical long-range gamma synchrony is coupled to the theta wave and engram activities. Such a process might underlie hippocampus-mediated memory encoding and recall in the neocortex in a highly coordinated way. Engram coding partial context information in each cortical region was integrated by gamma synchronization and this integration contribute to intact memory representations.

Moreover, we investigated whether the egocentric cortical representation is influenced by LEC during retrieval. We found that the number of objects which were encoded in an egocentric manner was decreased after LEC inhibition (Supplementary Fig. 18a, b), and egocentric maps of those labeled cortical neurons were more dispersive when LEC was inhibited by CNO (Supplementary Fig. 18c). This data suggests that the LEC-mediated cortical gamma synchrony is required during memory retrieval for the precision coding of the egocentric map.

We found LEC activity is essential to the formation of spatial memory. We inhibited part of the LEC activity (as the hM4Di were not detected in all the LEC neurons) throughout all the training days of the spatial memory task, and mice showed significantly reduced performance in recall trials (Supplementary Fig. 19, see details in Method: “LEC Inhibition During Spatial Memory Encoding”). We also labeled the learning activated cortical neurons on day 4 and found that they were not activated much in the recall trial, indicating the LEC activity was essential for the formation of context-selective cortical neurons (Supplementary Fig. 19d). Our data indicated that LEC-mediated gamma synchrony is critical for both memory encoding and engram reactivation during memory retrieval. While engram activities were representing the “egocentric” map of each landmark in individual cortical regions, LEC (HPC complex)-mediated cortical long-range synchrony integrated them to form an intact egocentric representation of the behavioral context. Thereby, HPC-LEC activities are serving as a coordinator to allocated individual cortical memory units for contextual and spatial memory storage (Fig. 6j).

Discussion

The gamma synchrony is associated with cognitive function in neocortex, especially for sensory processing and associative learning34,45,57,58. Our data revealed the long-range gamma synchrony is mediated by axons from LEC neurons, which project to layer 2 of cortical regions, including RSC, VIS, SS, and MO, and synchronize activities between each region for memory storage. While memory engrams in individual cortical regions encode egocentric maps of dispersed features, successful encoding and retrieval of memories require the LEC-mediated gamma synchrony between multiple cortical regions to generate an integrative memory representation. Thereby, the long-range gamma synchrony, which is modulated by hippocampal theta rhythm could serve as the coordinator to organize the collective memory representation in neocortex (Fig. 6j). Our studies implicate distinct roles of two brain structures in memory processing: the cortical networks embed memorized information, while hippocampal-associated structures engage the coordination of the cortical networks to access or modify specific memories.

Long-range phase synchronization has been identified in human31. Such a conserved phenomenon might play critical roles in the brain. The synchronization coordinates the timing of neuronal firing in functional distinct areas59,60, thus refining the long-range connections between cortical areas23,61,62. Alternatively, oscillation activities might directly affect engram activities via modulation on oscillatory frequencies63. Dominant frequencies of cortical LFP are related to the brain states and found to be essential for state-dependent memory retrieval64. Such LFP events might also contribute to system consolidation of the long-term memory65. Consistent with these reports, our observations indicated a strong linkage between the cortical oscillations and the memory processes, especially with the L2 engram activities.

Besides the learning-associated long-range synchrony, our data revealed neural mechanisms that memory retrieval is closely associated with the reactivation of cortical memory engrams in layer 2. While studies indicated the artificial reactivation of those memory engrams induces the retrieval of specific memories17,65, we further demonstrated that activities of the cFos-labeled neurons, which were recruited during the learning phase, encode egocentric place information in the behavioral context. In contrast to those detected in the single-unit recording, the photometry recording revealed a populational egocentric coding specific in the labeled population (15–20 neurons under the tip). Remarkably, activation of those neurons was detected during the pre-exploring period, when no landmark cues were presented. It is likely reflecting the active memory retrieval of the spatial information as inhibition of LEC/HPC complex, which impairs memory retrieval, significantly reduced cortical engram activities before the door opening.

Our discovery on the HPC-regulated distributive cortical engrams shines a light on the memory index theory, which proposes that memory is stored in distributed cortical and subcortical modules, while HPC registers extrahippocampal network connectivity patterns66–68. We found HPC/LEC do regulate activities of engrams in multiple cortices via providing gamma synchrony, suggesting the traveling waves in the brain and their synchrony could take a role as the index to register cortical memory units. These observations are also consistent with a recent report that Tanaka and colleagues15 found the hippocampal CA1 engrams encode the behavior context rather than the specific place information and were coupled to theta rhythm. It is interesting to speculate that allocentric spatial map in place cells and egocentric information coupling to the hippocampal engrams might interact in CA1 to provide integrative information for spatial memory retrieval. In addition, the memory index theory suggests the HPC might not retain and deliver memorized information, but keep the internal index to access that information. This theory is consistent with our finding that artificially imposed iSOS signal is able to encode and retrieve memory, probably via providing indexing role to the cortical memory units.

Our study suggests that brain machine interface (BMI) devices could improve cognitive function in health.. Studies have demonstrated memory enhancement through deep brain stimulation69 or transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS)70. However, the stimulation settings are highly variable with electrode placements, stimulation waveforms, and spatial-temporal scales71. Our biological insight into the memory process might inspire BMI designs targeting LEC and proposed specific stimulation protocols with the gamma synchrony. On the other hand, while decoding neural oscillation signals usually employ power or single units72, instantaneous large-scale multi-pair cortical phase synchrony could be used to decode neural information via BMI equipment. We propose that the revealed biological mechanism of memory encoding and retrieval could improve the efficiency of BMI for future technologies.

Methods

Mouse subjects

The Laboratory Animal Facility at the Tsinghua University and ShanghaiTech University are accredited by Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. Wild type (C57BL/6), Rbp4-Cre (Tg-KL100Gsat), Ai9 (007909, The Jackson Laboratory), and cFos-CreER mice (021882, The Jackson Laboratory) were utilized in experiments. All animals were socially housed in a 14 h/10 h (7 a.m.–9 p.m.) light/dark cycle, with food and water ad libitum. All experimental animals were 3–5 months old (22–35 g) and male. After surgery, they were housed individually in homecage in a humidity- and temperature-controlled environment. The mice recovered from surgery for at least 1 week before all behavioral tasks. All animal protocols and experiments and were evaluated and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tsinghua University (license 15-GJS1) or ShanghaiTech University (license 20201218002) based on Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Eighth Edition), and conducted in agreement with Chinese law (Laboratory animal -Guideline for ethical review of animal welfare, GB/T 35892). This study complies with all relevant ethical regulations animal testing and research, and received ethical approval from Laboratory Animal Resources Center at Tsinghua university and from Scientific Research Ethics Committee at ShanghaiTech University.

Electrode implantation and stereotaxic injection

Recording electrodes were custom made by platinum-iridium (90–10%) wires (coat: PTFE diameter, 33.020 μm, A-M system, 775003) and tungsten (coat: PTFE diameter, 105 μm, A-M system, 795500). Only electrodes with an impedance lower than 2 MΩ were employed. During the implantation surgery, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane. The speed of airflow was kept at 1.2 L/min with 1.5% (v/v) isoflurane. Local sterilizing (75% alcohol) was applied to the skin before making the incision. Holes were drilled and optrodes were implanted in the retrosplenial cortex (RSC, AP: −3 mm, ML: −0.7 mm, DV: −0.25 mm), secondary motor cortex (M2, AP: −1 mm, ML: −0.7 mm, DV: −0.25 mm), primary visual cortex (V1, AP: −3 mm, ML: −3 mm, DV: −0.25 mm), CA1(AP, −2.0 mm; ML, −1.5 mm; DV, −1.3 mm) and LEC (AP: −4.35 mm, ML: −4.0 mm, DV: −4.0 mm relative to the bregma). Four screws were inserted above the cerebellum, two of them were used as reference and the other two ground electrodes were used as ground. Two references were interconnected and isopotential, two ground screws were also interconnected and isopotential. The implantation was secured by black dental cement. In activation/inhibition of LEC neuron fiber/cell body experiment, AAV2/9-DIO-NpHR-EYFP, AAV2/9-DIO-oChiEF-mCherry or AAV2/9-hSyn-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry was injected into LEC region (1 μL, 0.1 μL/min, AP: −4.35 mm, ML: −4 mm, DV: −3.85 mm relative to the bregma). Optical fiber (d = 200 μm, N.A. = 0.48) was implanted in LEC (AP: −4.35 mm, ML: −4 mm, DV: −3.65 mm relative to the bregma).

Cranial window opening

Cranial windows were opened for shining 470 nm excitation light by LED, mice were immobilized in custom-built stage-mounted ear bars and a nosepiece. Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane. A 1.5 cm incision was made between the ears, and the scalp was removed to expose the skull. One circular craniotomy (6–7 mm in diameter) was made using a high-speed drill and a dissecting microscope for visualization. A glass-made coverslip was attached to the skull. A 3D printed headset (for LED holding during the experiment) was attached on top of the coverslip.

Hippocampal lesion

Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane and placed into a stereotaxic frame. A midline incision was made on the scalp, the skin was removed and the skull overlying the targeted region was removed. Injections of NMDA (10 mg/ml, dissolved in PBS) were injected to induce hyperactivity for killing cells in the target region (Dorsal: AP, −1.5 mm; ML, −2 mm; DV, −2 mm; Ventral: AP, −3 mm; ML, −2.5 mm; DV, −3 mm). Injection of 0.25 μl was given in 2 min at each site. Mice show seizure behavior and abnormal mobility after NMDA injection, as the evaluation whether the NMDA was injected successfully. Once the mouse show seizure behavior, it was put back under anesthesia for 3 h and then recover in the homecage for 2 weeks. The learning and memory behavioral experiment was performed after recovery.

Open field test

To test whether the activation or inhibition of LEC cortical fiber will cause some side effects in mice, the open field test was performed upon 470 nm or 589 nm LED stimulation. Mice were placed in the center of an open-field apparatus (46 cm wide × 46 cm long × 40 cm high) and were allowed to move freely for 12 min (LED: OFF → ON → OFF → ON, 3 min each section) after a 5 min habituation. Mice activities were video recorded. Total travel distance and other parameters were analyzed by a computerized mouse tracking system (MATLAB).

Spatial memory task

Before training, mice were put on a food deprivation regimen that kept them at ~85% of their free-feeding body weight. Mice were put into the box to forage for sunflower seeds as food reward in the TSE system (Multi-conditioning system, TSE system). The sandboxes A and B were the same sizes as the mentioned open-field context (46 cm × 46 cm × 40 cm) but with different objects and foodzone locations. There were no cues on the surrounding walls (A: identical pure white; B identical pure black) to provide allocentric information so that mice have to position the food by objects in the context (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Mice were trained three trials per day and underwent four days of training followed by two recall trials on day5. The trial interval was 2 min. In training trials, once the mouse finished the food or the mice cannot find the food in five minutes, we ended the trial. In recall trials, there was no food reward and mice were allowed to freely explore in the context for 3.5 min. The food zone was defined as a 10 cm × 10 cm rectangle with the center located at the food reward. The spatial memory task in Figs. 5 and 6 and Supplementary Fig. 19 was slightly different, training mice were confined on the start-region 1 min by an L-shape door (Pre-exploring,1 min) before freely exploring in the context (Exploring phase, 2 min). L-shape door was non-transparent, mice recall in the pre-exploring phase is indicating a recall without major sensory input from the context.

The y-axis range from 0 to 900 s in Fig. 2c is because the ‘latency to food intake’ means the accumulation time spent to reach the first food throughout three trials in a training day. For example, if a mouse cannot obtain the food in all three trials in a training day (300 s at most in one trail), the latency here would be 300 s + 300 s + 300 s = 900 s, and if the mouse obtains the food in the first trail by 50 s, that the latency would be 50 s. The food pellets were air-drying to reduce the odor and buried under the sand. These operations made it harder to reach the food, thus mice needed a longer time to recognize landmarks and dig in the right place to reach the food.

Memory test of landmark relocation

If mice are using an egocentric map during the spatial memory task, changed object locations will impair their performance. To verify this, a group of mice trained with the same spatial task paradigm (learn to find food in sandbox A for 4 days, Supplementary Fig. 16) followed by a performance test in the same box with altered object location (A’). The result showed that altering the object location largely decreased the foodzone occupancy in test trials (Supplementary Fig. 16b). This indicated that locations of objects are critical for mice to locate the food reward. Noted that the context has little allocentric information (unlike water maze with signs on the wall) so that mice have to rely on their relative position (egocentric information) to objects to locate the food.

Video recognition for occupancy and head direction

We identify the location of the mice by video recognition and then calculated the total time the mice spend in the foodzone to quantify the occupancy. Here is the entire video recognition process: 1. Frames were extracted every 0.2 s from the video file and then resize to 1/4 size and changed to grayscale. Each frame was subtracted by a frame without mice (usually it is an average of all frames) to produce frame difference for the determination of the location of the mice. One recall trail in total is 210 s (1050 frame) and starts when mice get off from the start block. 2. Each frame difference was binarized, the average of all points of x or y was determined as the mice body location. Head direction was determined by Skeleton algorithm 3. The context was divided into 46 × 46 grid, the foodzone was defined as a 10 × 10 region around the food position. Each bin of occupancy map was calculated as the proportion of body positions in that bin. For the occupancy of the foodzone, the total number of frames in which the mouse is located in the foodzone is Tfoodzone, and the total frame number of the trail is Tall = 1050. Therefore [Eq. 1]:

| 1 |

Contextual fear memory task

Contextual fear conditioning was performed in a fear box (square chamber, 20 × 20 × 39.5 cm) with a metal-gridded floor and yellow environment illumination. Experiments were performed in the TSE system. Training trials consist of a 3 min’ exposure of mice to the conditioning box followed by a foot shock (2 s, 0.8 mA, constant current). The memory test in Fig. 3a–e was performed 24 h later by re-exposing the mice for 3 min into the conditioning context. In Supplementary Fig. 12 memory tests were in 7 days after TRAP labeling (day8), 1st recall and the 2nd recall were performed on the same day, the second one was performed 10 mins after the first one. Freezing, defined as a lack of movement except for heartbeat and respiration associated with a crouching posture, was recorded by video and rated every 10 s by two blinded observers (unaware of the experimental conditions) for 3 min (a total of 18 sampling intervals). The number of observations indicating freezing obtained as a mean from both observers was expressed as a percentage of the total number of observations. The results were cross-validated by the automatic freezing counting in TSE.

LEC neurons and their cortical fibers stimulation or inhibition by optogenetics

We utilized the Arduino module to control the laser. During the electrophysiology coupled with optogenetics experiment, we activated LEC neurons by 470 nm laser (12.45 mW/mm2, Aurora-300-470, Newdoon technologies) and activated LEC cortical fiber by the same laser and irradiance. In the behavior experiment, we activated LEC cortical fiber by 470 nm LED (5.4 mW/mm2, model: 5050-470), inhibition of LEC fiber by 589 nm LED (6.8 mW/mm2, 5050–589).

iSOS rescue experiments

For rescue experiment of contextual fear conditioning (Fig. 3a–e). The experiment procedure is basically the same as described above (Method section: Contextual fear memory task), the distinct point of the rescue experiment is that mice were trained with or without iSOS (5.4 mW/mm2, 10 Hz or 30 Hz, 4 s on, 6 s off, 4 ms), depends on each group design. For rescue experiment of spatial memory task (Fig. 3f–j). The experiment procedure is in principle the same as described above (Method section: Spatial memory task). In each training trial, mice were delivered iSOS (5.4 mW/mm2, 10 Hz or 30 Hz, 4 s on, 6 s off, 4 ms pulse) or not, depending on each group design. In the experiment of reverse training of random signal (‘30 Hz’, pulses are randomly distributed but maintain 120 pulses in 4 s) and iSOS (30 Hz, 12.45 mW/mm2, 4 s on, 6 s off, 4 ms), two groups of mice underwent the opposite training order (Fig. 4). One group first trained with iSOS in sandboxA followed by random signal training in sandboxB, the other group underwent random signal in A, and then iSOS trained in B. After training in sandboxA, mice were back to homecage to recuperate with food and water ad libitum for 3 days before training in sandboxB. To ensure we can activate LEC cortical fibers separately, two optical fibers (diameter = 200 μm) with a low numerical aperture (N.A. = 0.37) were placed right on the surface of the cortex to confine the emission light to the local region.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were overdosed with 400 μl 2% phenobarbital sodium and perfused transcardially with cold PBS, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Brains were extracted from the skulls and kept in 4% PFA at 4 °C overnight, then transferred to 20% sucrose in PBS. 50 µm thick coronal slices were taken using a vibratome and were collected in cold PBS. For DAPI staining, each slice was placed DAPI in PBS (1:10000 dilution) for 40 min at 37 °C. Slices then underwent three times of washing for 5 min each in PBS, followed by adding the Anti-fade Mounting Medium (P0126, Beyotime) and coverslip on microscope slides.

Microscopy and cell counting

Sections (50 μm) were imaged using a ZEISS (LSM710META) confocal microscope. All imagings were done using standardized laser settings held constant for samples from the same experimental dataset. LEC downstream neurons were quantified in four cortical regions (RSC, MO, VIS, SS), all slices were quantified including cell amount and cell depth, for cell depth quantification, all tdTomato positive cells were imaged and calculated shortest distance from the cell body to the cortex edge by ImageJ (v1.52p) measure tool.

Memory-related neurons labeling and photometry

Activated neuron labeling. The TRAP system51 was adopted to label the activated neurons in a specific time window (task-related neuron labeling). First, AAV-DIO-GCaMP6f virus was injected into the superficial layer of retrosplenial cortex or visual cortex and optrodes (200 or 300 μm core diameter, 1.2 mm length, N.A. = 0.48, Newdoon Inc., hand-made by gluing the electrode to the optical fiber) were implanted above the virus injection sites and sealed by black dental cement. Noted that the tip of optical fiber was placed on the surface of the cortex (DV = −0.0 mm) and the protruding electrode was implanted into the cortex with the depth of 0.25 mm (DV = −0.25 mm, see schematic diagram in Supplementary Fig. 14a), mice could recover for 2 weeks before all subsequent experiments. Second, c-Fos-CreER mice were injected with tamoxifen for labeling memory engram (dosage: 100 mg/kg) 24 h before training day 4 (labeling day), released Cre protein enables the GCaM6f expressed in activated neurons. Third, 7 days after labeling (PBS: day11/13; CNO: day12/14, CNO was injected intraperitoneally 1 h before the behavioral experiment), engram activities were recorded by fiber photometry system in homecage (Home), unfamiliar context (CtxB), and learning context (Recall x2) followed by a retraining trial to avoid memory extinction. All fiber placements and virus injection sites were histologically verified post experiments. In practice, the surface of the optical fiber and electrode vary across cases, only those cases with optical fiber and electrode located in target place were included (fiber surface, depth <200 μm; electrode, depth <350 μm). Images in Supplementary Fig. 14e show cases with optical fiber located on the surface of the cortex. In addition, we also quantified the CEs from cases with optical fiber depth more than 200 μm (Supplementary Fig. 14f), we found neuronal activity from these cases shows no context specificity (Supplementary Fig. 14g).

The fiber photometry system. The fiber photometry system was bought from Thinker Tech Nanjing Biotech Limited Co. Excitation light from a 488 nm semiconductor laser (Coherent, Inc. OBIS 488 LS, tunable power up to 60 mW) was reflected by a dichroic mirror with a 452–490 nm reflection band and a 505–800 nm transmission band (Thorlabs, Inc. MD498), and then coupled to a fiber (Thorlabs, Inc., 200 μm in diameter and 0.48 in N.A.) by an objective (JiangNan, Inc. 20×, N.A. 0.4). The emission fluorescence was collected with the same optical fiber and then detected by a highly sensitive photomultiplier tube (PMT, Hamamatsu, Inc. H10720-210) after being filtered by a GFP bandpass emission filter (Thorlabs, Inc. MF525-39). The laser intensity at the interface between the fiber tip and the animal was adjusted to around 30 μW to minimize bleaching. Signals were collected at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz and further filtered through a 10 Hz IIR low pass filter. The analog voltage signals were digitalized and collected using FiberPhotometry software (Thinker Tech Nanjing Biotech Limited Co.) and were further analyzed in MATLAB.

Signal analysis. At the beginning of our experiment, we set the cutoff of ΔF/F0 according to a set of control experiments. We tested the noise of our recording system by measuring the signal from unchanged EGFP signals (data not shown). This control signal (EGFP) was detected as small variations only (<1% ΔF/F0), far smaller than the GCaMP6f signal. According to this control experiment, we set the threshold of calcium event identification to 1.25% ΔF/F0 for 470 nm signals (GCaMP6f). Thus, we perform our subsequent GCaMP6f recording by the system. Here ΔF/F0 = (F − F0)/F0, where F is the fluorescence intensity at any time point, and F0 is the averaged F in five seconds time window with a center on the corresponding time point. To further verify the specificity of recorded signal, we recorded the signals from tissue simultaneously with 405 nm and 470 nm light, we found the signals are specific to GCaMP and only 470 nm light can detect obvious fluorescence changes in different tasks (Supplementary Fig. 14d). Therefore, our recorded signals represent the activities of labeled neurons.

LEC inhibition during spatial memory encoding

cFos-CreER Mice were trained with inhibited LEC by hM4D(Gi) (AAV2/9-hSyn-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry with CNO, which was injected intraperitoneally 1 h before the behavioral experiment) during every training day in the spatial memory task and memory-related neurons were labeled on day4 (Supplementary Fig. 19a). Same as the behavioral protocol of spatial memory task before. Behavioral tests and recoding of calcium activities were set on day 11 (also with CNO injection for LEC inhibition). Although these mice could find the food during training, they showed poor memory recall in recall trials (Supplementary Fig. 19b, c), indicating the LEC is essential for the storage of long-term memory. In the cortical neurons labeled with GCaMP6f during training, CEs were detected in homecages and untrained unfamiliar context and reduced in the trained context (Supplementary Fig. 19d). This result is in great contrast to the LEC activated condition.

LFPs data collection and analysis

The raw data was amplified during the behavioral experiment with a 1000 Hz sampling rate (Apollo Neural Data Acquisition (DAQ) Systems, v1.0.0, Bio-Signal Technologies, USA), LFP signals were bandpassed at 1–200 Hz. Notch filters were not applied. Unless indicated otherwise, analyses were performed using chronux toolbox (2.12v03) and MATLAB code written by the authors. Channels with a low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) were identified and deleted. Reasons for low SNR included 50 Hz line interference, electromagnetic noise from surrounding equipment, and poor connection between screws and cortical tissue. Mice with large moving artifacts or 50 Hz line noise were excluded from the final dataset.