Abstract

Depression is a common and debilitating disorder in the elderly. Late-life depression (LLD) has been associated with inflammation and elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and IL-6, but often depressed individuals have comorbid medical conditions that are associated with immune dysregulation. To determine whether depression has an association with inflammation independent of medical illness, 1120 adults were screened to identify individuals who had clinically significant depression but not medical conditions associated with systemic inflammation. In total, 66 patients with LLD screened to exclude medical conditions associated with inflammation were studied in detail along with 26 age-matched controls (HC). At baseline, circulating cytokines were low and similar in LLD and HC individuals. Furthermore, cytokines did not change significantly after treatment with either an antidepressant (escitalopram 20 mg/day) or an antidepressant plus a COX-2 inhibitor or placebo, even though depression scores improved in the non-placebo treatment arms. An analysis of cerebrospinal fluid in a subset of individuals for IL-1β using an ultrasensitive digital enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay revealed low levels in both LLD and HC at baseline. Our results indicate that depression by itself does not result in systemic or intrathecal elevations in cytokines and that celecoxib does not appear to have an adjunctive antidepressant role in older patients who do not have medical reasons for having inflammation. The negative finding for increased inflammation and the lack of a treatment effect for celecoxib in this carefully screened depressed population taken together with multiple positive results for inflammation in previous studies that did not screen out physical illness support a precision medicine approach to the treatment of depression that takes the medical causes for inflammation into account.

Subject terms: Depression, Molecular neuroscience

Introduction

There is substantial literature reporting elevated inflammatory markers in depression (reviewed in Miller 2009; Beurel 2020) [1, 2]. Compared with nondepressed individuals, those with major depressive disorder (MDD) have elevations of inflammatory cytokines in peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [3, 4]. Increased cytokines include interleukin (IL)−1, C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), and IL-6 [5]. Patients with MDD, particularly those with late-life depression (LLD), also have increased oxidative stress [1, 6] and elevations in circulating acute phase reactants, including nitric oxide synthase and prostaglandins [6–8].

The association of inflammatory markers with LLD could point to a causal role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of LLD. In support of a causal association, IL-6 has been shown to interfere with the production of serotonin from tryptophan by increasing the breakdown of tryptophan, thus reducing serotonin levels (and increasing depression risk) and preferentially increasing the synthesis of kynurenine and its neurotoxic metabolites, 3-hydroxykynurenine and quinolinic acid. IL-6 drives this metabolic shunt and IL-10 partially counters it [1]. Proinflammatory factors including cytokines were reported to be associated with an increased risk of developing depressive symptoms [9, 10]. In the case of prolonged exposure to cytokines, there is an increased risk of becoming depressed, with ~25% of patients with chronic elevations of interferon (IFN)-α experiencing symptoms of MDD [11]. In addition, Maes and colleagues [1, 3] observed that depression is often accompanied by increased oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation.

An alternative explanation for the association of LLD and inflammation is that inflammation might result as a consequence of LLD or inflammatory conditions that “travel together” with LLD. IL-6, for example, has been called the “gerontologist’s cytokine” by William Ershler, who proposed that this cytokine regulates a key human aging pathway [12], given the consistent association between elevated plasma IL-6 and poor health outcomes. Increased plasma IL-6 is a risk factor for many diseases of aging, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular ischemia, and type 2 diabetes, all of which are more common in LLD [13]. Thus LLD patients with comorbid illness may represent a subset with elevated inflammation. IL-6 is also associated with sleep impairment, fatigue, and cognitive dysfunction [14]. Overall, MDD is associated with a significant reduction in lifespan, in part due to suicide and in part due to the association with comorbid major medical disorders, including cardiovascular disease and stroke, autoimmune disease, diabetes, and cancer [15–17].

Given the high rates of comorbid illness in patients with MDD, we sought to disassociate the links among depression, medical illness, and inflammation by carefully screening out patients with known inflammatory-associated illness. This approach allowed us to determine, in the absence of known comorbid illness, whether depression was associated with higher rates of inflammation. In addition to determining baseline levels of inflammation in MDD vs. controls, we sought to determine whether treatment with antidepressants had anti-inflammatory effects. Finally, we sought to determine whether antidepressants supplemented with anti-inflammatory medication, celecoxib, resulted in additional antidepressant benefits.

Materials and methods

Patient recruitment and study entry criteria

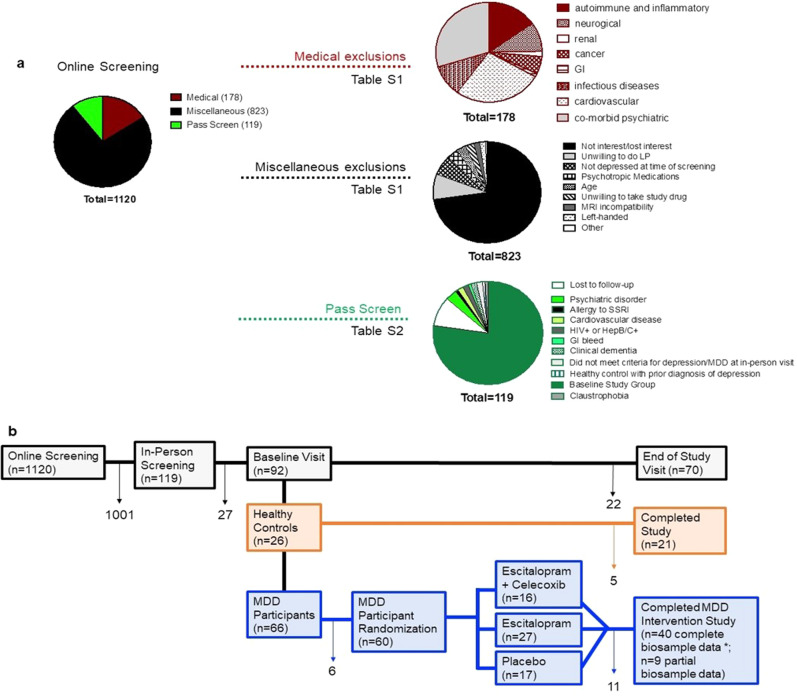

Our goal was to recruit a cohort of older individuals with MDD without comorbid conditions associated with inflammation. The study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited through University of Pennsylvania clinics and surrounding communities using IRB-approved flyers, radio and subway ads, and Facebook posts. A total of n = 1120 participants were screened remotely through a center-wide screening form, either self-report or over the phone, to identify general exclusionary factors. Medical records, where available, were screened as well to identify exclusion criteria. Miscellaneous reasons (n = 823) and disqualifying medical conditions (n = 178) determined exclusion from study participation for n = 1001 participants, Fig. 1a and Table S1.

Fig. 1. Overview of study participant groups, screening, and cohorts.

a 1120 individuals were screened online. Of those, 178 were excluded for medical reasons (red chart and see Table S1 for further details) and 823 were excluded for miscellaneous reasons (black chart and see Table S1 for further details). The remaining 119 individuals passed the screen (green). Of those, additional individuals withdrew or were excluded upon further review (see Table S2 for details). b Numbers of individuals for screening, baseline, and randomization visits as well as the final subject numbers. Arrows indicate the number of individuals who withdrew or were excluded at various stages of the study. MDD = major depressive disorder. Of the n = 49 who completed the study *n = have complete biosample data sets. Of these 40, n = 18 escitalopram, n = 12 escitalopram + celecoxib, n = 10 placebo.

Informed consent was obtained from n = 119 participants (n = 87 MDD, n = 32 HC) and diagnostic status was clarified through medical history and prescription drug intake review (Table S2). Psychiatric diagnoses (SCID-5), depressive symptomatology with the Montgomery Asberg Rating Scale (MADRS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), and Depression History form were assessed by the study physician. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (≥26/30 defined as normal) ruled out cognitive impairment. Self-report questionnaires assessed events related to stress and abuse (Perceived Stress Scale & Life Event Stress Scale, Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology of Exposure (MACE) Scale). Vital signs, EKG and biosampling for rheumatoid factor, and hepatitis screening concluded screening procedures. At the baseline visit, n = 92 (n = 63 MDD, n = 29 HC) were evaluated, and 70 (n = 49 MDD, n = 21 HC) completed all study visits (Fig. 1b). The randomization scheme and participants’ compliance produced allocation of n = 21 participants to escitalopram with n = 18 completing baseline and study end biomarker assessments, while for the escitalopram/celecoxib arm, these numbers amounted to n = 13 and n = 12, respectively, and for the placebo arm to n = 11 and n = 10, respectively. In cases where group sizes deviate from the above due to missing data, we report this where applicable in the results.

Compliance

Compliance with study medication (verum & placebo) was assessed by pill count. The study coordinator dispensed and counted the study medication provided by the Penn Investigational Drug Service to the participant during scheduled study visits at the beginning of week 1, week 2, and week 4.

Cardiovascular safety

For blood pressure and heart rate readings, all repeated values at the same visit were averaged. To compare trends in blood pressure and heart rate, differences from the baseline visit were computed. The area under the curve (AUC) is reported for each systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate across the values in weeks 1, 2, 4, and 6. Missing values were filled by linear interpolation. A t test with Welch’s correction was applied to the AUC values in the ESC group (n = 6) versus the ESC + Celecoxib groups (n = 13).

Clinical blood sample collection and processing

In all, 20 mL peripheral venous blood was collected into EDTA tubes for isolation of plasma and 4 mL of blood was collected into SST (serum separator tubes) for isolation of serum. The EDTA tubes were spun at 310 × g for 15 minutes, the SSTs were spun at 1000 × g for 15 min, and the plasma or serum was collected, aliquoted, and stored in the −80°C freezer until use.

Immunological assays

In this study, we aimed to have 80% power to detect at least one analyte (out of 29) at 1 SD difference from controls at an FDR of <0.05. Peripheral blood cytokine levels were measured using multiplex bead arrays, high-sensitivity ELISA, or Single molecular array (Simoa) assays in the Human Immunology Core at the University of Pennsylvania. Samples were assayed using a human 29-plex cytokine/chemokine magnetic bead microsphere immunoassay panel (HCYTMAG-60K-PX29, MilliporeSigma; Burlington, VT) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were run in duplicate and fluorescence data were acquired using Luminex® xPONENT® 4.2 on a FlexMAP3D Luminex instrument. IL-1β levels were also measured using an ultrasensitive digital ELISA (Simoa Cat #101605, #101622, # 101580 from Quanterix; Billereca, MS) in CSF and on selected serum/plasma samples following the manufacturer’s specifications. Samples were tested in duplicate, and data were acquired on a Simoa HD-1 analyzer [18].

Cytokine data processing and analysis

Average cytokine or chemokine mean fluorescence intensity values (MFIs) were converted to estimated concentrations (pg/mL) through interpolation on a standard curve for each cytokine using Bio-Plex Manager software (v. 6.1, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). MFI values that were negative after subtraction of the blank were listed as 0. If the measurement was negative, 0, or was otherwise below the analytical sensitivity of the assay (“out of range” low, as indicated by the data analysis software), an arbitrary value of 0.001 pg/mL was used instead of 0 pg/mL for statistical purposes (to facilitate log-scale comparisons). Baseline differences in median MFI and concentration measures between MDD and HC groups were compared for each individual analyte using two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum tests with uncorrected p values < 0.05 considered statistically significant. To evaluate the aggregate measure across cytokines in an individual sample, the mean and standard deviation (SD) for each analyte were computed using the HC baseline MFI data. Fold change by SD relative to the HC group were visualized on heat maps, using similar methods to those described previously [19] Interpolated concentration, MFI data, and fold change data were visualized using Prism software v.9.1.2, GraphPad, San Diego, CA.

Longitudinal changes in MADRS scores

MADRS scores were assessed at baseline and final visits. Subjects within each treatment group had baseline and final MADRS scores compared by a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to assess improvement in depression levels within each treatment group. The healthy controls were not examined as all MADRS scores were very low (4 or less). To assess the effect of escitalopram, all subjects receiving escitalopram (regardless of celecoxib treatment) were compared to those receiving placebo. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model of the final MADRS scores by treatment (escitalopram or not) with baseline score as a covariate was performed.

Results

Study participants

We assembled a carefully controlled group of MDD and HC individuals. Stringent inclusion criteria compiled an MDD cohort without comorbid conditions associated with systemic inflammation (Fig. 1a, b; Table 1). MDD and HC individuals did not differ significantly with respect to the average age, race, sex, and other covariates (Table 2).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Visit | Assessments |

|---|---|---|

| Age 50–80, right-handed male or female, any race | Screening survey | Screening survey |

| Absence of clinical dementia | In-person visit | Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDRS) |

| English speaking | Screening Survey | Screening survey |

| Blood pressure not exceeding 150/90 mmHg, treated, or untreated | In-person visit | Vitals and electrocardiogram (EKG) |

| Normal result on liver function test | In-person visit | Blood draw |

| No history of ulcer disease or GI bleeding | Both |

Screening survey Medical history |

| Weight >110 pounds | Both | Screening survey vitals |

| Willing to take antidepressant medication/willing to switch antidepressant medication | Screening survey | Screening survey |

| DSM-IV criteria for MDD§ | In-person visit |

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-V (SCID) Overview Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) Depression History |

| Exclusion criteria | ||

| Known history of relevant severe drug allergy or hypersensitivity | In-person visit | Medical history |

| Does not speak English | Screening survey | Screening survey |

| Cannot give informed consent | In-person visit | Informed consent process |

| MRI contraindications (e.g., foreign metallic implants, pacemaker, claustrophobia) | Screening Survey | Screening survey |

| BMI > 30 | Screening Survey | Screening survey |

| Known primary neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury, cognitive impairment, or dementia | Screening Survey | CDRS medical history |

| Known inflammatory disease (such as systemic lupus erythematosis, known autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s disease; Screen + for rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibody, HIV, Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C) | Both |

Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) Medical History Blood Draw |

| Clinical Dementia Rating Scale score >0 | In-person visit | CDRS |

| Diagnosis of a chronic psychiatric illness other than MDD | In-person visit | SCID overview |

| Significant handicaps (e.g., uncorrected hearing or visual impairment, mental retardation) that would interfere with testing | In-person visit |

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey SF (36) Disability Scale |

| Bleeding diathesis | In-person visit |

Medical history blood draw CIRS |

| Severe Medical problem, which in the opinion of the investigator would pose a safety risk to the subject | In-person visit |

Medical history CIRS |

| Clinically significant cardiovascular disease within the last 6 months (see methods) | In-person visit |

Blood draw vitals Framingham Scale EKG |

| Clinically significant abnormalities on EKG. Primary AV block or right bundle branch block were not necessarily exclusionary | In-person visit | EKG |

| Current diagnosis of cancer | Both |

Screening survey Medical history |

| Use of an investigational medicine within the past 30 days | In-person visit | Medical history |

| Use of Coumadin, Warfarin within the past 2 months | In-person visit | Medical history |

| Current treatment with psychotropic drugs or drugs that affect the CNS such as beta-blockers, mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, steroids, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. No subjects were included in the study unless they had been off all psychotropics for at least 3 weeks, except in the case of fluoxetine, where 5 weeks off treatment was required | In-person visit | Medical history |

| Current alcohol or substance abuse disorder, schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, or current OCD | Both |

SCID overview DIGS summary |

| History of ulcer disease, Crohn’s disease, GI bleed, or anemia | Both |

Screening survey Medical history |

| Renal insufficiency | In-person visit | Blood draw |

| Any other factor that in the investigator’s judgment may affect patient safety or compliance (e.g., travel distance >100 miles from this facility) | Both | |

| Active suicidality or current suicidal risk as determined by the investigator§ | In-person visit |

SCID overview MADRS HDRS |

§Indicates criteria unique to depressed participants.

Table 2.

Demographics of study cohorts.

| Variables | Healthy controls | Participants with MDD | P value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 24) | Escitalopram + celecoxib (n = 14) | Escitalopram (n = 24) | Placebo (n = 15) | ||

| Mean age (years) | 65.2 | 57.4 | 62.1 | 61.6 | 0.86 |

| SD age | 10.3 | 6.4 | 9.8 | 8.0 | |

| Gender (male/female) | (13/11) | (6/8) | (13/11) | (8/7) | 0.95 |

| Race (white/black) | (16/8) | (8/6) | (13/11) | (8/7) | 0.38 |

| BMI | 25.3 ± 2.8 | 26.64 ± 3.8 | 0.14 | ||

| Relationship | 0.62 | ||||

| Married/long-term relationship | 48% | 29% | 27% | 21% | |

| Divorced/separated | 30% | 38% | 53% | 36% | |

| Never married | 22% | 33% | 20% | 43% | |

| Education | 0.69 | ||||

| Post-graduate & professional degree | 48% | 21% | 37% | 20% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 23% | 29% | 8% | 20% | |

| Associate degree | 0% | 14% | 17% | 47% | |

| Some college & high school | 29% | 35% | 38% | 13% | |

| Employment | 0.79 | ||||

| Full time | 43% | 43% | 18% | 13% | |

| Part time | 14% | 29% | 32% | 47% | |

| Retired | 29% | 7% | 18% | 20% | |

| Unemployed | 9% | 7% | 14% | 13% | |

| Disability | 5% | 14% | 18% | 21% | |

| Salary | 0.95 | ||||

| $50,000 and above | 66% | 36% | 20% | 21% | |

| $30–50,000 | 10% | 14% | 25% | 7% | |

| $0–30,000 | 24% | 60% | 55% | 72% | |

*Significance of differences between MDD and HC cohorts were compared using t-tests for age and BMI and using the Freeman-Halton method for the others.

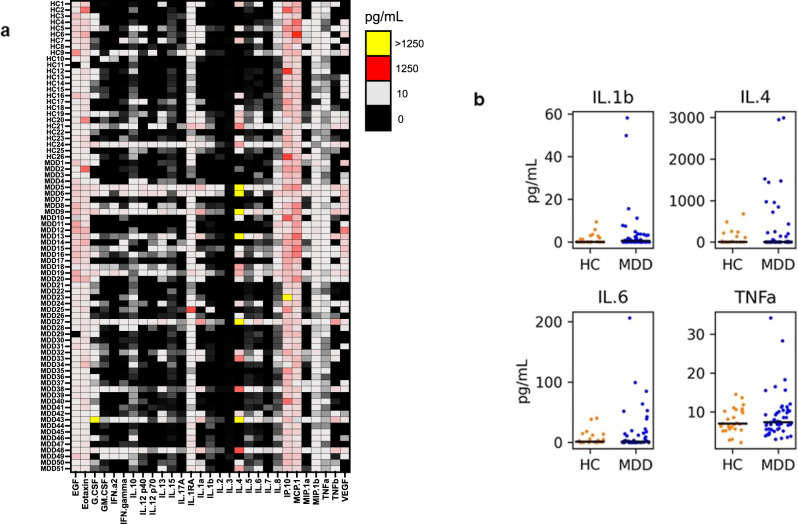

Comparison of inflammatory peripheral blood biomarkers at baseline

To determine if individuals with MDD had higher levels of systemic inflammation than HC prior to any intervention, we used a multiplex bead array assay to measure circulating levels of 29 different cytokines and chemokines at the baseline time point (see Methods and Fig. 2a shows a heat map of the data for each individual at baseline). Average analyte concentrations were computed from replicate measures and the levels of each analyte were compared between the two groups of individuals by rank-sum test (Fig. 2b shows selected cytokines, Fig. S1 shows all of the analytes, and Table S3 shows the rank-sum test results). For comparisons of all blood luminex biomarker levels at baseline between MDD and HC groups, our test (with n = 51 cases and 26 controls) had 86% power to detect a single analyte with a 1 SD difference from controls at an FDR < 0.05 level (with all other analytes equal between groups), correcting for the 29 analytes tested. If five of the analytes have a 0.6 SD difference from control, then power is 82% (i.e., power increases if multiple analytes differ between the groups).

Fig. 2. Baseline circulating cytokine profiles in individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) vs. healthy controls (HC).

a Heat map of cytokine profiles. Rows show the data for each individual (subject number, disease grouping), columns show each analyte. Interpolated assay values (picogram/milliliter; pg/mL) are heat mapped, with black denoting the lowest values. EGF epidermal growth factor, G-CSF granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, GM-CSF granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IFN interferon, IL interleukin, IP-10 interferon-gamma induced protein 10 (CXCL10); MCP1 monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, MIP-1α macrophage inflammatory protein 1a (CCL3), MIP-1β macrophage inflammatory protein 1b (CCL4), TNF tumor necrosis factor, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor. MDD major depressive disorder, HC healthy control. b Comparison of selected cytokine levels in MDD (blue) vs. HC (orange). The black horizontal line denotes median values for each analyte and cohort. The sample size is n = 51 MDD and n = 26 HC. No differences were significant by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test in any of the 29 analytes (all comparisons are shown in Fig. S1, p > 0.1).

No cytokines or chemokines differed significantly between MDD and HC (p < 0.05 by two-tailed rank-sum test), even before correction for multiple comparisons. Because there were a large number of individuals with very low levels of inflammatory markers, we also compared MDD and HC marker levels in only individuals who had non-zero levels. Here, again, none of the analytes was significantly different between the groups.

Because some individuals had mild elevations in multiple markers, we next turned to the exploratory evaluation of aggregate measures. We generated heat maps of the multiplex bead array data by MFI (Fig. S2). Using the MFI values of the HC group to compute a mean and SD, we weighted the values of each individual measurement based on its distance in SD away from the HC mean. When the binned SD distances were displayed on a heat map (Fig. S3) and scores were ranked from high to low, 17 of the top 20 aggregate scores were found in patients with MDD (Fig. S3a) but the difference in median score between MDD and HC was not statistically significant (Fig. S3b).

Because serum cytokine levels overall tended to be very low, we wondered if our failure to observe a consistent difference between individuals with and without MDD could be due to limitations in the analytical sensitivity of the multiplex bead assay. To address this issue, we evaluated IL-1β levels in MDD and controls at baseline using a digital ELISA (dELISA), an assay that is 10–100x more sensitive than the multiplex bead assay [18]. We chose IL-1β because it has previously been associated with depression [20–23] yet exhibited several values in our current assays that were out of range low. The dELISA was able to detect cytokine levels in samples that were out of range low by luminex (Fig. S4a), but no statistically significant increase in IL-1β levels was observed in MDD compared with control at baseline (Fig. S4b). For comparisons of the CSF IL-1β levels (with n = 5 HC and n = 19 MDD) power was 42% to detect a 1 SD difference between the groups. Power was determined using Monte-Carlo simulation, assuming normal distributions and performing a Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

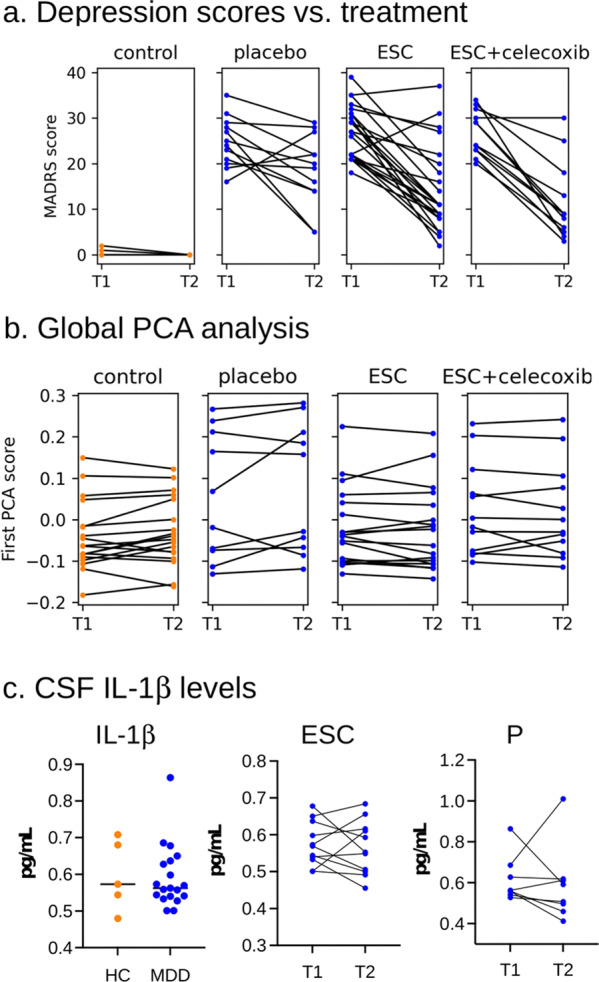

Improvements in MADRS scores

To verify the effectiveness of the treatments, MADRS scores were assessed at baseline and at the final visit (Fig. 3a, Table S4). MDD and HC participants who completed the study visits did not differ significantly with respect to their underlying medical conditions (Table S5). Among the MDD participants who were stratified to different treatment groups, scores were comparable between escitalopram (27.1 ± 5.6 mean ± SD), escitalopram/celecoxib (26.2 ± 4.8) and placebo (25.5 ± 5.4). MDD patients in all groups experienced significant improvement in their MADRS scores (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, escitalopram, 14.0 ± 9.1, p < 0.001, n = 23; escitalopram/celecoxib, 13.2 ± 9.9, p = 0.003, n = 12: placebo, 19.1 ± 7.9, p = 0.034, n = 12). In addition, the patients receiving escitalopram (either with or without celecoxib) saw a significant improvement over patients receiving placebo (ANCOVA p = 0.030, effect size = −6.34 (SE = 2.8) points, n = 35 on escitalopram, n = 12 on placebo). The lower mean MADRS score in escitalopram/celecoxib compared with escitalopram did not attain statistical significance (ANCOVA p = 0.42, celecoxib effect size = −2.46 (SE = 3.0) points, n = 12 escitalopram+celcecoxib, n = 23 escitalopram).

Fig. 3. Temporal analysis of depression scores, CSF IL-1β levels, and integrated biomarkers.

a MADRS scores at baseline and final visit. MDD patients in all groups saw significant improvement to MADRS scores (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, escitalopram p < 0.001 in n = 23, escitalopram and celecoxib p = 0.003 in n = 12, and placebo p = 0.034 in n = 12, healthy controls n = 23). In addition, the patients receiving escitalopram (either with or without celecoxib) saw a significant improvement over patients receiving placebo (ANCOVA p = 0.030, effect size = −6.34 (SE = 2.8) points, n = 35 with escitalopram, n = 12 placebo). b Integrated inflammatory biomarker signature at baseline compared with a final visit in the treatment and control cohorts. The scores for the top principal component were computed from inflammatory biomarker concentrations measured at T1, and then scores from T2 measurements were computed by projection according to T1 loadings. No significant changes were observed in any groups (Wilcoxon signed-rank test p > 0.1 for all treatments; n = 18 control, n = 10 placebo, n = 18 escitalopram (ESC), n = 12 ESC + celecoxib) and individuals’ scores were highly consistent. T1 = start of therapy; T2 = after 8 weeks of therapy. c IL-1β levels are low in CSF and do not change with treatment for depression. IL-1β levels in the CSF were measured by dELISA in 5 HC (orange) and 19 individuals with MDD (blue). The median level is N.S. (p = 0.688, Wilcoxon rank-sum test); CSF IL-1β levels do not change following treatment with ESC (20 mg/day × 8 weeks, p = 0.638, Wilcoxon signed-rank test); Lines interconnect samples from the same patient drawn at T1 and T2. CSF IL-1β levels do not change following treatment with placebo (P, p = 0.461, Wilcoxon signed-rank test); CSF cerebrospinal fluid, HC healthy control, MDD major depressive disorder, ESC escitalopram, P = placebo.

Longitudinal changes in inflammatory peripheral blood biomarkers

Baseline and final visits of cytokine and chemokine levels were compared and were remarkably similar over time in most individuals (Fig. S5). No analyte showed significant changes from baseline after adjustment for multiple comparisons (Table S6, p > 0.05, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). To determine whether there were changes in aggregate inflammation levels, the top PCA component was computed in both baseline and final visit, using loadings determined by baseline alone. No treatment group had a significant change in PCA score (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p > 0.1 for all treatments), and individuals’ scores were highly consistent across the two time points (Fig. 3b).

CSF levels of IL-1β were low and did not change following treatment with escitalopram or placebo

To determine if there were elevations in intrathecal cytokines in our carefully screened cohort of MDD patients, CSF was obtained and analyzed using the dELISA assay for IL-1β from 19 cases and 5 controls. Levels of IL-1β were uniformly low in the CSF and did not differ significantly between MDD and controls at baseline (Fig. 3c, p = 0.688, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). Furthermore, no significant change in IL-1β levels was observed in MDD individuals after treatment with escitalopram (Fig. 3c, p = 0.638, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Treatment with a placebo also did not significantly alter CSF IL-1β levels (Fig. 3c, p = 0.461, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Cardiovascular safety

Because celecoxib has been associated with cardiovascular toxicity, we evaluated blood pressure and heart rate responses in individuals on escitalopram + celecoxib as a safety signal. Averaged blood pressure responses in individuals on escitalopram/celecoxib were higher compared to escitalopram only, but this trend was not statistically significant (p = 0.23 for SBP, p = 0.32 for DBP). The heart rate response was lower in individuals on escitalopram/celecoxib (p = 0.002) (Fig. S6). However, the degree of variability between screen and baseline measurements was comparable in magnitude to the effect size following treatment. Taken together, these data suggest that there is no significant cardiovascular signal using these read-outs.

Discussion

In this study, we observed very low levels of circulating cytokines and inflammatory mediators in individuals with MDD and in controls, when study participants in both groups were carefully screened to exclude medical causes of inflammation. At baseline, MDD patients and controls both exhibited very low levels of 29 different circulating cytokines and chemokines. In many cases the levels of cytokines fell below the analytical sensitivity of the luminex assays, a finding that has also been reported in the literature when individuals with low levels of inflammation are included among the comparison groups (for example, see: [24–26]) The lack of difference between MDD and control groups was not due to poor sensitivity of the assays as high-sensitivity analysis of IL-1β levels in serum using a digital ELISA also did not reveal any difference between MDD patients and controls.

We also did not observe a significant difference in inflammatory markers between patients with MDD and controls. When MDD patients were treated with an antidepressant (escitalopram), their depression scores improved compared to placebo. However, when MDD patients were treated with escitalopram and an anti-inflammatory (celecoxib), depression scores and cytokine levels following treatment were not lower than in MDD patients who were treated with escitalopram alone. Finally, to get “closer to the source” of the inflammation, IL-1β levels were also measured in the CSF for a subset of MDD patients treated with escitalopram or placebo. Intrathecal CSF IL-1β levels were low and remained low irrespective of treatment. Taken together, these results indicate that depression in and of itself does not cause inflammation in this carefully selected patient population and that anti-inflammatory treatment of patients with MDD who do not have inflammation has no additional antidepressant benefit.

Our results contrast with many previous studies of MDD in which cytokine elevations have been reported. In multiple meta-analyses [20, 27–29] increased proinflammatory cytokines and acute-phase proteins were reported in MDD patients, with a fairly unanimous consensus of increases in IL-6, TNFα, and CRP in the blood of MDD patients compared to healthy controls [1, 30, 31]. Further, with advances in the measurement of cytokines by multiplexing [32], many additional cytokines are now evaluated [33, 34]. A recent meta-analysis of 82 studies including 3212 MDD patients and 2798 healthy controls revealed increased levels of IL-6, TNF, IL- 10, sIL-2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL)2, IL-13, IL-18, IL-12, IL-1RA, and soluble TNF receptor (sTNFR) in MDD patients [29]. However, patients in those studies were not excluded on the basis of physical illness associated with inflammation.

In this study, all participants were screened to exclude illnesses with known associations [35, 36] with inflammation, including inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, among an extensive list. The participants included in the study, including those who completed the final study visit had medical illnesses requiring ongoing medical treatment, but these illnesses did not differ in prevalence between the HC and MDD groups. The large number of patients excluded is notable in that it points to the high rates of physical illness in most patients with depression. It has been estimated that more than half of MDD patients have associated comorbidities [37, 38] including hypertension, metabolic disorders, and chronic lower respiratory diseases [39]. Also consistent with the hypothesis that inflammatory conditions are associated with depression, a meta-analysis across 22,000 patients reported in 40 studies found a pooled prevalence of mental disorders of 36.6% in patients with chronic physical diseases [40]. Finally, an elegant study demonstrated a marked risk of becoming depressed following cytokine exposure, with ~25% of initially euthymic patients exposed to IFN-α experiencing symptoms of MDD [11].

With respect to therapy, there was no significant effect of escitalopram on inflammation levels in the current study. Further, unlike some previous studies, the addition of celecoxib to escitalopram did not change the outcome of depression response. A number of studies have supported fairly large effect sizes [41] for trials of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors as antidepressants, especially as antidepressant augmenting agents, although other studies have found no antidepressant benefit for these agents [42, 43]. Further, some studies have shown that the effect of anti-inflammatory drugs on depression is dependent on the patient’s baseline inflammatory levels. This was first suggested by Raison and collaborators [44], replicated by Nettis and collaborators [45], and reviewed by Branchi and collaborators [46]. Given the low baseline levels of inflammation in our MDD cohort, it is perhaps not surprising that there was no benefit of augmenting antidepressant treatment with celecoxib.

A limitation of our study is that levels of cytokines were not measured in the medically excluded patients with inflammation to demonstrate elevations, which would have provided a more direct test of the hypothesis that physical illness rather than depression was associated with inflammation in our patient population. However, as discussed, previous studies provide ample demonstration of cytokine elevations in patients with identified inflammatory conditions. Another challenge was that patients dropped out of the study. The dropout rate in our study (24%) is consistent with dropout rates for depression studies reported in the literature (10–32%) [47–49]. Further, those who dropped out did not differ demographically from those who remained in the study and we have no evidence to suggest that individuals who dropped out differed with respect to their inflammatory profiles, because all of the individuals at baseline had low levels of inflammatory markers.

Our results add to others who argue that depression should be considered a heterogeneous disorder [46]. Our study identifies depressed individuals who do not have evidence of systemic inflammation, while other studies have focused on depressed patients with inflammation. In support of this concept of heterogeneity in MDD, a recent study [50] found distinct immunologic profiles for inflamed and non-inflamed depression, with the inflamed group characterized by increased levels of circulating neutrophils, monocytes, CD4+ T cells along with elevated IL-6 and CRP. In addition, when data-driven techniques were used to agnostically define different immunologic variants of MDD, four distinct subgroups were identified: two with increased IL-6 and CRP and more severe depression, one with predominant increases in neutrophils, and monocytes, and one with increased lymphoid cells. Together with these studies, our study supports mechanistically distinct groups of inflamed depression and an immunological distinction between inflamed and non-inflamed depression. Our findings in MDD patients with non-inflamed depression make the important point that inflammation is not an intrinsic component of depression and prompt further consideration of personalized therapeutic approaches for MDD in which both inflammation and depression are addressed.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants for their participation and Ms. Maria Prociuk for her excellent assistance with manuscript preparation. This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, R01 MH098260-02, PI Dr. Yvette Sheline). The authors would like to acknowledge the Human Immunology Core (P30-CA016520, P30-AI0450080) at the University of Pennsylvania for their help with the Luminex and Digital ELISA assays performed in this study. Dr. Thomas Brooks received funding from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant (5UL1TR000003) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) T32 Training grant (5T32MH106442-04). Dr. Skarke is the Robert L. McNeil Jr. Fellow in Translational Medicine and Therapeutics and obtained funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, R01 MH098260-02). The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT02389465.

Author contributions

E.L.P.: study design, data analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the article, manuscript revision, and final approval. T.B.: data analysis, interpretation of data, and manuscript revision. WM: acquisition of data, data analysis. J.C.B.: data analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript revision. L.Z.: data analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript revision. T.G.: acquisition of data. C.S.: data analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the article, manuscript revision, and final approval. Y.I.S.: conceptualization of the study, study design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, drafting manuscript, manuscript revision, and final approval.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-022-01883-4.

References

- 1.Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:732–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beurel E, Toups M, Nemeroff CB. The bidirectional relationship of depression and inflammation: double trouble. Neuron. 2020;107:234–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maes M, Mihaylova I, Kubera M, Uytterhoeven M, Vrydags N, Bosmans E. Increased plasma peroxides and serum oxidized low density lipoprotein antibodies in major depression: markers that further explain the higher incidence of neurodegeneration and coronary artery disease. J Affect Disord. 2010;125:287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosano C, Marsland AL, Gianaros PJ. Maintaining brain health by monitoring inflammatory processes: a mechanism to promote successful aging. Aging Dis. 2012;3:16–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mossner R, Mikova O, Koutsilieri E, Saoud M, Ehlis AC, Muller N, et al. Consensus paper of the WFSBP Task Force on Biological Markers: biological markers in depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007;8:141–74. doi: 10.1080/15622970701263303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zorrilla EP, Luborsky L, McKay JR, Rosenthal R, Houldin A, Tax A, et al. The relationship of depression and stressors to immunological assays: a meta-analytic review. Brain Behav Immun. 2001;15:199–226. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2000.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maes M, Ruckoanich P, Chang YS, Mahanonda N, Berk M. Multiple aberrations in shared inflammatory and oxidative & nitrosative stress (IO&NS) pathways explain the co-association of depression and cardiovascular disorder (CVD), and the increased risk for CVD and due mortality in depressed patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:769–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reichenberg A, Yirmiya R, Schuld A, Kraus T, Haack M, Morag A, et al. Cytokine-associated emotional and cognitive disturbances in humans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:445–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brydon L, Walker C, Wawrzyniak A, Whitehead D, Okamura H, Yajima J, et al. Synergistic effects of psychological and immune stressors on inflammatory cytokine and sickness responses in humans. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:217–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musselman DL, Lawson DH, Gumnick JF, Manatunga AK, Penna S, Goodkin RS, et al. Paroxetine for the prevention of depression induced by high-dose interferon alfa. N. Engl J Med. 2001;344:961–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103293441303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ershler WB. Interleukin-6: a cytokine for gerontologists. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:176–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb02054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Veronese N, Kahl KG, Mitchell AJ, Lin PY, et al. Depression and physical health multimorbidity: primary data and country-wide meta-analysis of population data from 190 593 people across 43 low- and middle-income countries. Psychol Med. 2017;47:2107–17. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motivala SJ, Sarfatti A, Olmos L, Irwin MR. Inflammatory markers and sleep disturbance in major depression. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:187–94. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000149259.72488.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benros ME, Waltoft BL, Nordentoft M, Ostergaard SD, Eaton WW, Krogh J, et al. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for mood disorders: a nationwide study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:812–20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bortolato B, Hyphantis TN, Valpione S, Perini G, Maes M, Morris G, et al. Depression in cancer: the many biobehavioral pathways driving tumor progression. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;52:58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Windle M, Windle RC. Recurrent depression, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes among middle-aged and older adult women. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson DH, Rissin DM, Kan CW, Fournier DR, Piech T, Campbell TG, et al. The Simoa HD-1 analyzer: a novel fully automated digital immunoassay analyzer with single-molecule sensitivity and multiplexing. J Lab Autom. 2016;21:533–47. doi: 10.1177/2211068215589580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang SE, Feng A, Meng W, Apostolidis SA, Mack E, Artandi M, et al. New-onset IgG autoantibodies in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5417. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25509-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:171–86. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maes M, Song C, Yirmiya R. Targeting IL-1 in depression. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16:1097–112. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.718331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milenkovic VM, Stanton EH, Nothdurfter C, Rupprecht R, Wetzel CH. The role of chemokines in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Mukhara D, Oh U, Neigh GN. Neuroinflammation. Handb Clin Neurol. 2020;175:235–59. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-64123-6.00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Hao Y, Ou W, Ming F, Liang G, Qian Y, et al. Serum interleukin-6 is an indicator for severity in 901 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a cohort study. J Transl Med. 2020;18:406. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02571-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Neill CM, Lu C, Corbin KL, Sharma PR, Dula SB, Carter JD, et al. Circulating levels of IL-1B+IL-6 cause ER stress and dysfunction in islets from prediabetic male mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3077–88. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li G, Wu W, Zhang X, Huang Y, Wen Y, Li X, et al. Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha in patients with IgA nephropathy are closely associated with disease severity. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:326. doi: 10.1186/s12882-018-1069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:446–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Ho RC, Mak A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Affect Disord. 2012;139:230–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohler CA, Freitas TH, Maes M, de Andrade NQ, Liu CS, Fernandes BS, et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135:373–87. doi: 10.1111/acps.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maes M, Yirmyia R, Noraberg J, Brene S, Hibbeln J, Perini G, et al. The inflammatory & neurodegenerative (I&ND) hypothesis of depression: leads for future research and new drug developments in depression. Metab Brain Dis. 2009;24:27–53. doi: 10.1007/s11011-008-9118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart JC, Rand KL, Muldoon MF, Kamarck TW. A prospective evaluation of the directionality of the depression-inflammation relationship. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:936–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Kinrys G, Henry ME, Bakow BR, Lipkin SH, et al. Assessment of a multi-assay, serum-based biological diagnostic test for major depressive disorder: a pilot and replication study. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:332–9. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiraly DD, Horn SR, Van Dam NT, Costi S, Schwartz J, Kim-Schulze S, et al. Altered peripheral immune profiles in treatment-resistant depression: response to ketamine and prediction of treatment outcome. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1065. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Syed SA, Beurel E, Loewenstein DA, Lowell JA, Craighead WE, Dunlop BW, et al. Defective inflammatory pathways in never-treated depressed patients are associated with poor treatment response. Neuron. 2018;99:914–924 e913. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller AH, Raison CL. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:22–34. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E, Carrera-Bastos P, Targ S, Franceschi C, et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat Med. 2019;25:1822–32. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0675-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Liu J, Swartz M, Blazer DG. Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996;17–30. [PubMed]

- 38.Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Stohl M, et al. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:336–46. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steffen A, Nubel J, Jacobi F, Batzing J, Holstiege J. Mental and somatic comorbidity of depression: a comprehensive cross-sectional analysis of 202 diagnosis groups using German nationwide ambulatory claims data. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:142. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02546-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dare LO, Bruand PE, Gerard D, Marin B, Lameyre V, Boumediene F, et al. Co-morbidities of mental disorders and chronic physical diseases in developing and emerging countries: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:304. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6623-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bai S, Guo W, Feng Y, Deng H, Li G, Nie H, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-inflammatory agents for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91:21–32. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2019-320912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berk A, Yilmaz I, Abacioglu N, Kaymaz MB, Karaaslan MG, Kuyumcu Savan E. Antidepressant effect of Gentiana olivieri Griseb. in male rats exposed to chronic mild stress. Libyan J Med. 2020;15:1725991. doi: 10.1080/19932820.2020.1725991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baune BT, Sampson E, Louise J, Hori H, Schubert KO, Clark SR, et al. No evidence for clinical efficacy of adjunctive celecoxib with vortioxetine in the treatment of depression: a 6-week double-blind placebo controlled randomized trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;53:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.07.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raison CL, Rutherford RE, Woolwine BJ, Shuo C, Schettler P, Drake DF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the tumor necrosis factor antagonist infliximab for treatment-resistant depression: the role of baseline inflammatory biomarkers. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:31–41. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nettis MA, Lombardo G, Hastings C, Zajkowska Z, Mariani N, Nikkheslat N, et al. Augmentation therapy with minocycline in treatment-resistant depression patients with low-grade peripheral inflammation: results from a double-blind randomised clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46:939–48. doi: 10.1038/s41386-020-00948-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Branchi I, Poggini S, Capuron L, Benedetti F, Poletti S, Tamouza R, et al. Brain-immune crosstalk in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;45:89–107. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fornaro M, Novello S, Fusco A, Anastasia A, De Prisco M, Mondin AM, et al. Clinical features associated with early drop-out among outpatients with unipolar and bipolar depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:522–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sonawalla SB, Farabaugh AH, Leslie VM, Pava JA, Matthews JD, Fava M. Early drop-outs, late drop-outs and completers: differences in the continuation phase of a clinical trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:1415–9. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swift JK, Greenberg RP, Tompkins KA, Parkin SR. Treatment refusal and premature termination in psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and their combination: a meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2017;54:47–57. doi: 10.1037/pst0000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lynall ME, Turner L, Bhatti J, Cavanagh J, de Boer P, Mondelli V, et al. Peripheral blood cell-stratified subgroups of inflamed depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;88:185–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.