Abstract

Community-engaged research needs involving community organisations as partners in research. Often, however, considerations regarding developing a meaningful partnership with community organisations are not highlighted. Researchers need to identify the most appropriate organisation with which to engage and their capacity to be involved. Researchers tend to involve organisations based on their connection to potential participants, which relationship often ends after achieving this objective. Further, the partner organisation may not have the capacity to contribute meaningfully to the research process. As such, it is the researchers’ responsibility to build capacity within their partner organisations to encourage more sustainable and meaningful community-engaged research. Organisations pertinent to immigrant/ethnic-minority communities fall into three sectors: public, private and non-profit. While public and private sectors play an important role in addressing issues among immigrant/ethnic-minority communities, their contribution as research partners may be limited. Involving the non-profit sector, which tends to be more accessible and utilitarian and includes both grassroots associations (GAs) and immigrant service providing organisations (ISPOs), is more likely to result in mutually beneficial research partnerships and enhanced community engagement. GAs tend to be deeply rooted within, and thus are often truly representative of, the community. As they may not fully understand their importance from a researcher’s perspective, nor have time for research, capacity-building activities are required to address these limitations. Additionally, ISPOs may have a different understanding of research and research priorities. Understanding the difference in perspectives and needs of these organisations, building trust and creating capacity building opportunities are important steps for researchers to consider towards building durable partnerships.

Keywords: health education and promotion

Summary box.

Partnering with organisations should comprise more than tokenism. They need to be involved in the entire research process.

Organisations contributing to immigrant/rethnic-minority communities generally belong to one of these sectors: public, private and non-profit.

Different types of organisations have different level of community connectivity.

Community and service provider organisations from the non-profit sector are generally more approachable and require appropriate involvement approaches, such as collective research priorities, building trust and more.

Organisations from each sector have their own strengths and limitations, and researchers need to acknowledge those and plan their approach for partnership keeping that in mind.

The approach and nature of partnering with community organisations in research needs to be customised based on their individualities.

Introduction

People-centred research employs community-engaged approaches such as Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR)1 or Integrated Knowledge Translation (IKT),2 where different levels of the community are involved in research. These collaborative approaches should be built on equitably involving community partners in all aspects of the research process and enabling them to contribute their expertise and share responsibilities and achievements.3 4 Guided by these approaches, community-engaged research can play a crucial role in improving unmet needs5 and barriers6 to the optimal health and wellness of immigrant/ethnic-minority populations through exploring the issues, identifying their root causes and configuring potential solutions.

Understanding a community’s ecosystem is an important initial step for any community-based research programme and is fundamental in guiding the community engagement process.4 A community ecosystem comprises community members, different organisations working in the community, funders and policymakers dealing with problems or solutions in the community. The concept of community also varies and can be interpreted differently, for example, by geographic area, faith, profession and so on. For our research programme, we define a community as a group of people with shared characteristics largely related to culture, religion, country of origin and immigration status. Understanding the ecosystem includes identifying and engaging community champions and influencers, partnering with organisations active in the community and being sensitive to the dynamics of community subgroups. Emerging evidence that meaningful knowledge-user engagement is a major predictor of research utilisation has increased interest in researcher/knowledge user collaboration.7

Different levels of organisations working in the community are crucial knowledge users who need to be involved in co-producing knowledge so that research is more relevant, appropriate, responsive, acceptable and effective in promoting meaningful and sustainable change. Involving community organisations in research brings a community perspective and practicality to the research, which includes identifying and prioritising issues the community encounters and designing innovative solutions that are feasible and acceptable to the community.8 To develop a community-based research programme, we sought meaningful collaboration with potential knowledge users to guide us on relevant research questions, help with knowledge mobilisation initiatives and support our community engagement activities.

As part of our community-engaged research programme on immigrant/ethnic-minority community issues, we conducted a range of studies on health and wellness issues as well as integration and resettlement, including studies on equitable access to health care9–12 and labour market integration for internationally trained health professionals.13 14 We conducted studies where we explored the challenges and unmet needs faced by Bangladeshi-Canadians when accessing healthcare.9 10 Through our community conversations, we also explored probable solutions proposed by the community about the barriers they face.11 As our programme of research progressed, we strived to obtain guidance from the community, who contributed to shaping our research policy through issue prioritisation.12 During these studies, we engaged with various community groups and organisations and recognised different perspectives, expectations, benefits and limitations across the organisations. We strategised for meaningful and active involvement of the organisations working in immigrant/ethnic-minority communities in conducting research, priority setting, co-creating knowledge products and knowledge translation or mobilisation activities.4 Engagement was embedded within a participatory approach and entailed ongoing relationships between the researchers and organisations, where the community’s benefit was at the core.

Typology of organisations

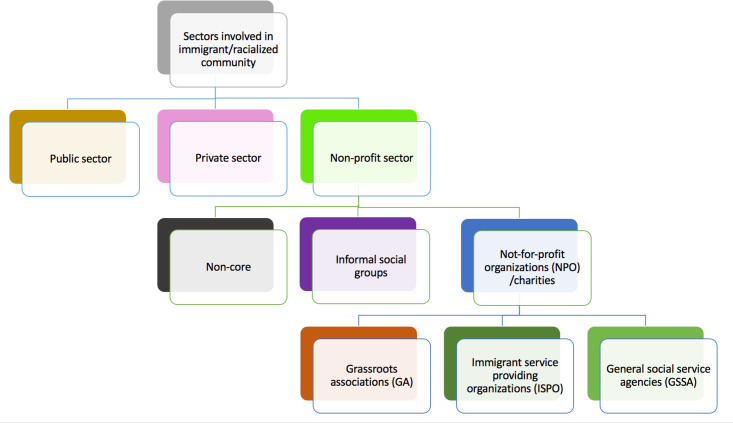

The ecosystem surrounding immigrant/ethnic-minority communities in Canada involves three main sectors: public, private and non-profit. The experiences we gained while developing our research programme related to visible minorities helped shape our understanding of the dynamics and nuances of the different types of community organisations. Figure 1 shows a basic typology of organisations active in the immigrant/ethnic-minority communities with whom we have been working. In this article, we reflect on our experience of developing collaborations with different organisations, particularly in the non-profit sector.

Figure 1.

Typology of the organisations generally active in the immigrant/ethnic-minority communities.

Understanding the public sector

We initially reached out to a number of organisations in the public sector who focus on immigrant and refugee health and wellness issues. These organisations included health service agencies, municipal-level local government networks and departments and provincial government social welfare branches. During this outreach process, we realised that public sector organisations lack strong and direct community connections. The nature of their involvement with grassroots communities tends to be more temporary and funding-based, rather than on building a working and lasting relationship with communities. This is indicated by a lack of follow-up, inconsistent communication with communities, and not actively including communities in the decision-making process.

As our community-engaged research programme has grown, our partnership with several of these organisations has developed into a policymaker/knowledge-user/researcher collaboration. We received guidance from them about their research needs and where we could contribute through our capacity and expertise. This also helped us propose research projects where they willingly contributed their expertise because the research questions fit their mandates. We believe community-engaged researchers are well positioned to continue to play a critical role in bridging the gap between the public sector and grassroots communities.

Understanding the private sector

In engaging the private sector in our research, we identified two categories of businesses based on their principal focus: businesses that predominantly focus on visible minority communities as their primary clientele (including ethnic groceries, ethnic restaurants or different types of businesses within the localities where visible minorities are dominant residents) and large corporations (such as banks, insurance companies, telecommunications and so on), whose principal focus is providing a general need to the overall community but who target ethnic minority communities to enhance their client base. Furthermore, their social commitment aims to contribute towards the development of ethnic minority communities as part of their overall community development initiatives.

Immigrant-focused businesses were a good venue for us to undertake our community outreach and dissemination efforts because of direct access to decision-makers and their position within the community, which allowed us to mobilise our efforts quickly and seamlessly. When we interacted with these organisations and explained our intentions, they were generous in letting us place posters, leaflets and survey materials in their venues. Mainstream corporations contribute indirectly to the community through funding the non-profit sector. They often have projects and funds specifically allocated for community development and research (eg, Scotiabank-Mitacs Economic Resilience Research Fund15). Aligning the contributions from the private sector with the needs of the community and academic research objectives is promising for community-engaged research.

Apart from these two groups of private-sector organisations, there are other organisations who tend to employ newly arrived immigrant/ethnic-minority people more commonly, such as meat packing plants, fast food restaurants, transport, maintenance and so on. It is likely that these employers do not seek much experience and have high turnover of staff; therefore, newly arrived immigrant/ethnic-minority people commonly use them as a starting job. In addition, there are some private sector groups who hire foreign workers in Canada. Examples include agriculture and caregiver organisations, who usually hire foreign workers on work permit who often become immigrants as their length of stay in Canada progresses. In our experience, these organisations do not have community-level interaction or influence. Their health and wellness activities are more workplace focused and occupational issues related. Despite these characteristics, there is potential that these organisations can be partnered with in innovative ways to improve community health.

Understanding the non-profit sector

The non-profit sector touches on virtually all aspects of community life in Alberta. Several terms have been used interchangeably in the extant literature to describe the non-profit sector, including independent sector, third sector, charitable sector, tax-exempt sector, civil society, social enterprise, voluntary sector or non-governmental organisations.16 17 There is an additional term in Canada—the core non-profit sector—for charities and other non-profit organisations (not including hospitals and universities).18 During our engagement process, we identified two types of active entities in the community level: informal social groups and not-for-profit organisations (NPOs).

Informal social groups

Informal social groups are formed organically in a community when individuals of similar interest or background interact with each other. For instance, we found many such groups within the Bangladeshi-Canadian community in Calgary, some of which were formed with a group of community members around a particular interest, such as a group interested in playing cricket/badminton or in religious discussion/practice or cultural groups for plays/theatres or singing. These groups do not have formal registration as organisations, rather they are formed by individuals to satisfy their social needs of affiliation.

Social network theory emphasises how social relationships drive and influence behavioural change and use of scarce resources, build trust among members and hold important social capital.19 20 While they do not have structured organisational governance, they have a high level of interaction within the community and have solidarity and the trust of community members, which makes them important allies for impactful community-engaged research.21

Not-for-profit organisations

NPOs in Canada are defined as tax-exempt registered organisations, such as an association, club or society, that operate for social welfare, recreation or pleasure, civic improvement or any other purpose aside from generating a profit for its owners.22 23 NPOs in Alberta are registered across the following subgroups based on the types of activities on which they focus: Culture and Recreation, Social Services, Religion and Others. These groups are aggregations of the 12 classifications in the International Classification of Nonprofit Organizations.22 23 There are a number of established taxonomy frameworks that classify NPOs into different subgroups. During our initial exploration of those organisations active in the Bangladeshi-Canadian community, we observed some interesting nuances across these organisations. When we interacted with the NPOs to collaborate on community-engaged research, our understanding of some field-level factors led us to classify them as grassroots associations (GAs), immigrant service providing organisations (ISPOs) and general social services agencies (GSSAs).

Grassroots associations

GAs are entirely created and run by community members, and their work predominantly is community-focused. They do not depend entirely on grant funding for their existence. Crowdsourcing or community drives for funds are their main income sources, which is predominantly used for their activities rather than administrative salaries. They also tend to be membership-based. In our experience, for taking research to the grassroots level, GAs have the largest reach. However, a more personalised engagement approach is needed that focuses on trustful relationship building. This can be achieved through being available for the community with genuineness, following through on commitments, and being transparent and accountable. This needs to be undertaken through continuous community engagement, rather than taking a parachute in and out approach.4 GAs generally are not familiar with the concepts of partnered research and thus may not feel engaged by a conventional invitation for research partnership without having been involved in prior relationship-building efforts.

Immigrant service providing organisations

ISPOs are funded by different levels of government to work across immigrant/ethnic-minority communities in a given locality. Their work focuses on providing service to people in need, including the Bangladeshi-Canadian community. These organisations are important allies while conducting research or knowledge mobilisation with subgroups of community members who need services, particularly as the services these organisations provide are predominantly accessed by the people who require them.

General social services agencies

GSSAs include organisations that provide various social services to the community within which they operate. They provide services, including, but not limited to, child and women welfare; helping people struggling with addiction, mental health or domestic abuse; serving people who are affected by food insecurity; labour market integration and so on. Further, GSSAs are funded by different government levels or private donations and their work focuses on the overall community, not only immigrant/ethnic-minority communities. Many members of immigrant/ethnic-minority communities benefit from accessing services offered by GSAAs. In our experience, involving GSSAs in immigrant/ethnic-minority grassroots community level research may not be directly advantageous, but they can play a major role in knowledge translation activities and the scale-up efforts of the research programme, thus helping with impact creation. Thus, developing collaboration with GSSAs is very important for any community-engaged programme of research.

Working towards research engagement

Our outreach efforts involved engaging different organisations active in the community in our research programme. Following traditional community-based research approaches (CBPR1 or IKT2), we requested their involvement and input in our research activities at different levels. CBPR and IKT promote the idea of involving potential knowledge users from the onset across all the aspects of research process. Thus, we not only asked them to assist with the data collection, we also initiated discussion with them to help polish the research question, plan the data collection and analysis and interpretation, and knowledge creation and translation. We also presented the opportunity to co-publish our manuscript with organisation members who wanted to be more involved in the research process as a community scholar and citizen researcher.24 We sought to develop and maintain an equitable and empowered partnership—one that recognises and respects each partner, yet clearly distinguishes roles—to minimise false expectations and potential conflicts. Given the nature of our research programme, we have placed a strong emphasis on partnership building with GAs and ISPOs, as we found them to be the most connected with the immigrant/ethnic-minority community.

Outreach to GAs for buy-in

We started reaching out to the Bangladeshi-Canadian community’s grassroots organisations to get their buy-in for our research programme. For example, within the Bangladeshi-Canadian community in Calgary, there are sociocultural groups based on professional identity (eg, agriculturalist association), educational institute attended (eg, University of Dhaka alumni), current profession (eg, geologist association), religious attachment (eg, Islamic study group) and cultural group (eg, Bangla cultural group). We met with these organisations’ leaders in coffee shops and community meeting spaces to express our interest in involving them in the research process meaningfully and discussed how to move forward together on research topics that matter to the community. We also reached out to the main social organisation of the Bangladeshi-Canadian community in Calgary, the Bangladesh Canada Association of Calgary, whose Health & Wellness Secretary agreed to support our efforts. We took the approach of a listening campaign, which is a focused effort to connect and identify concerns and priorities of organisations and communities. This listening campaign helped us shape our vision for a community-informed research programme through community-engaged inquiry of community members’ lived experiences and articulations on access to healthcare issues they face. Realisations and learnings from outreach with GAs are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Realisations and learnings from outreach with grassroots associations (GAs)

| Realisation | Learnings |

| Grassroots associations | |

| GAs generally focus on very specific event-based activities |

|

| Research engagement has been a distant idea for GAs |

|

| Initiating research awareness was needed |

|

Joining forces with ISPOs

As previously noted, a number of different organisations are actively involved in immigrant/ethnic-minority communities in such areas as cultural, educational, religious, developmental, charity, social care and serving vulnerable members. We reached out to those organisations active in Calgary to build connections and develop trust. In this phase, we have been using our previous knowledge synthesis results5 6 25 and the summaries of the community listening campaign for discussions. Realisations and learnings from outreach with ISPOs are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Realisations and learnings from outreach with immigrant service provider organisations (ISPOs)

| Realisation | Learnings |

| Immigrant service provider organisations | |

| ISPOs appreciate the importance of research |

|

| There is a lack of understanding of working styles and deliverables between academics and ISPOs |

|

| ISPOs are overburdened by requests to collaborate |

|

| Academics fail to maintain post-project follow-up |

|

From engagement to partnership

Research partnerships between researchers and diverse stakeholders for research and knowledge mobilisation activities are becoming widely accepted and sometimes are being mandated by funding authorities.26 27 There needs to be a paradigm shift in the way community-level research is done from one in which the researcher is the sole authority to one in which researchers and stakeholders co-lead research activities by collectively applying their knowledge, expertise and skills. In our process of community-engaged research, it was enlightening for us to explore and recognise the dynamics of the different types of organisations active in the communities in which we focus our research. During our collaboration development efforts, a number of aspects helped us achieve a more meaningful approach. Details of those learnings are set out below.

Understanding the organisations’ perspectives

It was important to understand the organisations’ perspectives on getting involved in research. Different types of organisations had different perspectives that influenced their motivations. GAs were not keen on becoming involved in active research activities, but rather were more interested in being the end-users or supporters of KT activities. Alternatively, ISPOs were more inclined to participate in both research and KT activities.

Building a reciprocal trusting relationship

Our most important realisation was that trust building is an important component for partnering with any type or level of organisation. Academics need to be prepared to engage in conversations with community members. Engagement should not only involve conversing with the organisation, rather the plan should involve working together. Concurrently, it is important for organisations to be proactive towards building trusting relationship through exploring ideas on how academics’ involvement can benefit the organisation. Working together has the potential to yield a tangible benefit for both organisations and academics.

Striving for mutually agreeable tasks to achieve common goals

It is important that academics and organisations establish goal consensus and work on mutually agreeable tasks to achieve those goals. With those organisations with whom we had a more successful partnership, a common goal and mutually developed working plan were very effective. We had clear conversations so that both parties were aware of each other’s working style, capabilities and individual accountabilities (eg, funding authorities or institutional objectives). Most effective for us was that the partner organisations recognised that achieving the common goal meant the working plan needed to accommodate the working process of the researchers to ensure the methodological rigour of the work, which impacts the pace (ie, getting ethics approval, ensuring adequate sample size and so on). We also understood the need to support or produce items that were time sensitive for the partner organisation. Our working plan was developed collaboratively and accommodated the needs of both parties, keeping the common goal at the forefront. GAs had less issues around the working plan, given the nature of their organisation, goals and activities. It was more important for developing partnerships with ISPOs due to their externally funded mandated activities.

Being open to conducting research the organisations identified as important

In general, academics conceive of research ideas and reach out to those organisations they feel are important stakeholders. To develop a meaningful partnership, it is good practice that academics be open to discussing research ideas relevant to organisations. From our experience, organisations, particularly ISPOs, appreciate this approach. Organisations often recognise research areas of interest to them while working in the field. However, they may need to reach out to researchers to see if anyone has an interest in the topic. Often due to unavailability of interested researchers or lack of funds and resources to conduct the research, the research needs of these organisations remain unaddressed. Through innovative approaches, organisations and researchers need to find ways to meet these research needs. Sometime some grants are available for research projects that meet the needs of an organisation, which allows and motivates researchers to engage in research projects based on community/organisation needs. From our experience, organisations, particularly ISPOs, appreciate this approach. However, to date, this approach has not been requested to us by GAs.

Commitment to creating research capacity

We also were committed to creating research capacity within the organisations when requested. Despite extreme interest from both sides, it is often difficult to engage organisations in the entire research process due to their lack of understanding and skills required for contributing to research design, analysis and interpretation. Our approach involved designing workshops and learning sessions and making those available for the organisation members, which helped improve research capacity. In our experience, our approaches and activities not only increased relationship building, but also helped organisations realise the importance of partnerships and contributing towards a sustainable engagement. It is important for organisations to understand what the win is for them, as only a win–win scenario can move everyone forward.

Planning for shared resource mobilisation

In partnering with organisations, it is important to plan for and discuss resource allocation based on the budget for the specific project. Research funding is structured differently from service delivery or community event funding, and each party needs to be cognizant of the unique aspects of their funding allocation. Academics and organisations need to have a mutual understanding of all aspects of funding and resource allocation throughout their partnership.

Community organisations, particularly ISPOs, have a full workload. To contribute actively to research, they need to allocate staff time, which competes with other deliverables. Generally, the salaries they receive from their funders do not cover research-related activities. Our partners expressed that they would be able to contribute more meaningfully if they could be compensated for their time and resources investing in the research partnership. This could be through honorarium or time buy-out for the organisation members. This is even more difficult for GAs, whose organisational work is volunteer-based and taking up research-related activities is often not feasible. We appreciate the importance of and have strived and strategised to allocate resources for the time contributed by partner members based on their level of contribution by incorporating their roles in our funding applications. Unfortunately, we have had mixed success in these regards. We have, however, been able to appoint community members as citizen researchers in some research projects.

Equitably involving organisations

Strategic, open discussions leading to role clarity, consensus on objectives and deliverables and a mutually agreeable work plan is conducive to creating an equitably empowered environment for research partners. The mutual learning curve for us and the organisations with whom we have worked has been steep, but these steps are critical to the process. During conversations, the need to have a memorandum of understanding (MOU) in place between the parties was raised. MOUs are a means of documenting and formalising the intentions and general expectations of all parties. Our research programme is strongly involved with and contributes to the Newcomer Research Network (NRN) at the University of Calgary.28 The NRN has signed an MOU with several organisations with whom we have been doing research, specifically ISPOs, which has been deemed useful both by the organisations and academics. However, to date, we have not engaged with GAs similarly, as most of the GAs with whom we have interacted have been less interested in this process.

Some ISPOs suggested that having a project charter for all partnered research projects would benefit sustainable partnerships. A project charter is a collectively crafted planning document that outlines the goals, objectives, partnership roles, research activities and timeline of a specific project, which helps keep the activities organised and ongoing, facilitate clear communication and minimise misunderstandings. It also helps keep project objectives and activities aligned and easy to follow-up on when there are changes in the executive and other staff positions of partner organisations or where multiple partners are involved.

Partnership learnings

Researchers often partner with organisations on research with immigrant/ethnic-minority communities; however, often the organisation’s role remains limited to providing access to community members for data collection through their community contacts or the partnership tends to be more confined for knowledge translation. While a truly community-engaged approach involving mutual connection, understanding and engagement among researchers and the community is ideal, most research does not involve this level of partnership.28 The belief is that researchers tend to commodify and capitalise research on immigrant/ethnic-minority populations rather than channel it towards actually improving or empowering communities. Unless there is a solid and sustained partnership between researchers and community organisations that exceeds a particular project, ethical data collection and effective and meaningful mobilisation of research outcomes into practice is not possible. Researchers should take the first step towards building this relationship with grassroots communities and community-based organisations and ensure that organisations are not only a bridge for researchers to collect data but that these communities are an integral part of the research.

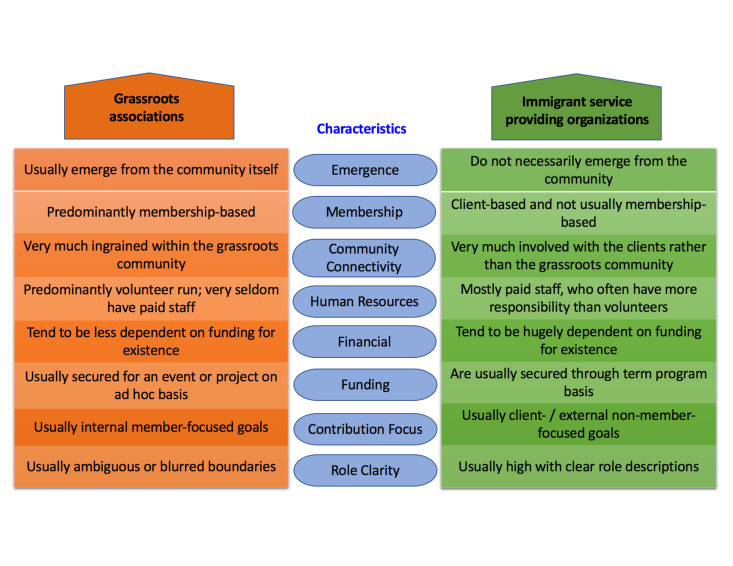

The degree to which different types of organisations are representative and trusted in the community is a key element. An important insight from our work is how distinct different types of organisations are. A variety of organisations are often the partners in various research projects, but they are not differentiated in most research reports. The differences in characteristics across these organisations were important to our understanding of engagement and was crucial to how we approached, developed and maintained our relationship with an organisation. These understandings also provided important clues on executing our research-related activities, such as surveying the community and recruiting for focus groups/interviews, across different research projects. In fact, in terms of community connectivity, we found that GAs are the most extensively community-connected organisations, followed by ISPOs. In our community-engaged research process, we extensively interacted with the GAs and ISPOs, and thus we opted to focus on these types of NPOs for this reflection paper. Figure 2 describes some fundamental characteristics across GAs and ISPOs.

Figure 2.

Fundamental differences between the grassroots associations and immigrant service providing organisations. GA, grassroots association; ISPO, immigrant service provider organisations.

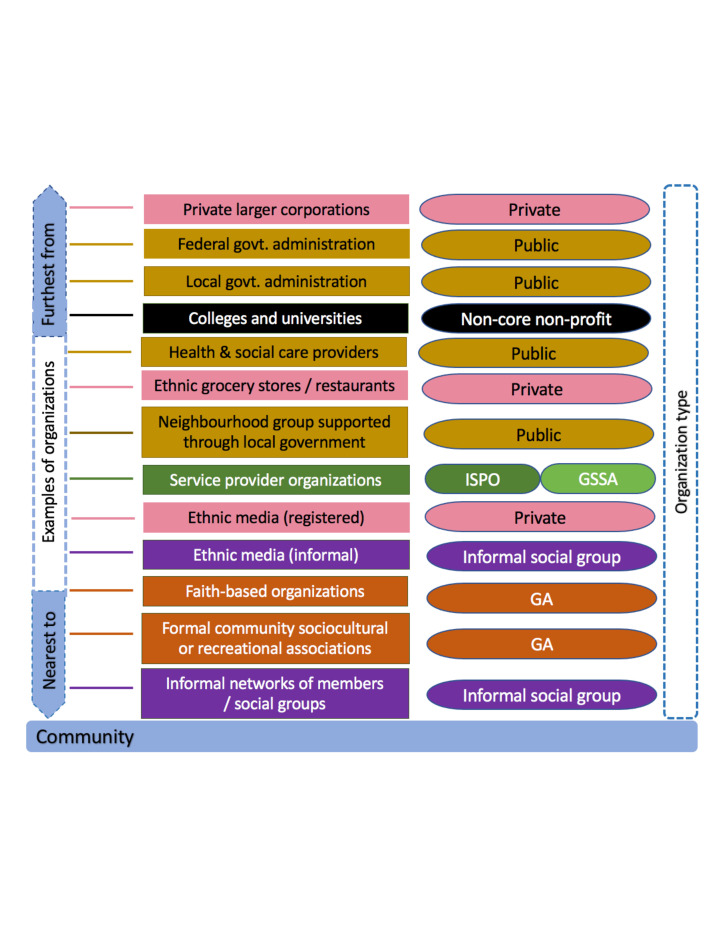

We also observed a difference in community connectivity and reach across different organisations. GAs are more ingrained within communities. ISPOs serve community members but are not as rooted in the general community. They do, however, have strong ties with those they serve. Figure 3 presents a schematic of the connectivity of different organisations with immigrant/wthnic-minority community we observed while interacting with a range of organisations. Different service providing organisations are less connected with the general community but strongly connected with the members they serve and are quite detached from immigrant/ethnic-minority grassroots communities in that respect. As expected, the private sector was largely separated from the community in terms of connectivity.

Figure 3.

Level of connectivity or degree of separation of different organisations to the immigrant/ethnic-minority communities. GA, grassroots association; GSSA, general social service agency; ISPO, immigrant service providing organisation.

Not every outreach initiative we have undertaken has been successful. We learnt much from our initial outreach for presenting our research programme to those organisations we identified as potential partners. We also learnt a lot during the process of working together. We realised that it is one thing to talk and plan about community-engaged research, but ‘walking the walk’ is a totally different ball game. We started conducting research with those we convinced to actively engage in our work, and we proactively kept others informed about the work being undertaken. Also, it is important that the organisations also understand the working environment the academics perform in. This will help them to contemplate towards a meaningful partnership. We believe that we, the academics, need to be proactive to initiate discussions on these aspects. We learnt from our oversights (box 1), and we capitalised on new opportunities for collaboration as they emerged. We were open to learning and put forward our recommendations to develop win–win partnerships. Box 1 summarises the approaches we felt worked and did not work in our efforts to making community-engaged research through partnership happen.

Box 1. Approaches that worked/did not work in partnering with community-based organisations.

Approaches that worked

Understanding the type, objective, interest and capacities of the community organisation to be engaged.

Working towards a long-term relationship.

Accepting community organisations as an equal partner with shared decision-making capacity in the research partnership.

Flexible timeline and schedule for engagement.

Offering/creating a win–win situation, where the community partner gains something from the research programme.

Arranging compensation/honorarium for time and resources wherever possible; also, being fair and open about the possibility for compensation.

Valuing each organisation’s agenda and aligning the research partnership goal accordingly.

Continuing to communicate and maintaining the relationship with the organisation, even if there is no specific project being undertaken, which builds trust that we will engage beyond the need for data collection or our own career goals.

Responding or offering support to the research need of an organisation even if it is beyond the scope of the research programme being undertaken, which predominantly occurred for us by providing methodology-related consultations or providing training for capacity building.

Approaches that did not work

Taking a parachute in and parachute out approach.

Not continuing to communicate once the project was completed.

Partnering with the organisations in the form of tokenism.

Researchers acting as a superior in the partnership.

Not being supportive towards benefits for the partner organisations.

Not following up with the organisations with the results and next steps of the research project.

Not respecting organisational goals and limitations while proposing a research partnership.

Although we reflect on our immigrant/ethnic-minority community-engaged research experience in an urban centre in Canada, the lessons learnt can be applied to other multicultural communities in Canada and other countries that welcome immigrant/racialised migrants, such as the USA, the UK, Australia, New Zealand and a number of Western European countries. However, our learnings will need to be contextualised within the local settings, as there will be differing sociocultural scenarios and immigrant/ethnic-minority community characteristics across these countries that will impact the engagement needs and approaches for partnering with the immigrant/ethnic-minority communities across the various locales.

Conclusion

The learnings from our community organisation-engaged research highlights the need to mobilise strategic and meaningful partnerships across academia and community organisations. Changing from the conventional one-time research project approach to a more sustainable and mutually beneficial collaborative programme of research approach will be valuable. Now more than ever this paradigm shift needs to happen. The goal is to facilitate the co-production and implementation of knowledge and include actors from all levels of the community to ensure equitable and empowered involvement. Without understanding the organisational diversity and degrees of representativeness and trust they have in the community and why they are hesitant to exert time and effort towards enhancing the research capacity of their community members, we may simply be maintaining the status quo instead of establishing critical and meaningful partnerships to conduct research in the communities to which we all belong.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the wholehearted engagement and gracious support we have received from the community members in Calgary. Also, we appreciate the compassionate encouragement and assistances we have received from all the socio-cultural organizations working in the grassroots community. We would also like to acknowledge the support from our academic peers and institutional leaderships towards this community-engaged program of research and our knwoledge engagement efforts.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: TCT, NR, and MQ conceived of the paper. TCT, MQ and NC coordinated drafting of different components of the paper. All authors provided critical input to multiple drafts. NC, NR and MAAL critically reviewed the manuscript. MQ, NR and MAAL provided important perspectives as community member researchers. TCT and MQ act as guarantor to this article.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the authors and are based on their working expeirence, positionality, and reflections.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement statement: While preparing this manuscript, we have partnered actively with community scholar and citizen researchers at the community level from the very beginning. We had regular interactions with them to get their valuable and insightful inputs in shaping our reflections. Their involvement in this paper also provided a learning opportunity for them and facilitated them to gain insight on knowledge engagement. All authors support the greater community / citizen / public involvement in research in an equitable manner.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

There are no data in this work.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was not required because this is a reflection piece by researchers on the lessons from equity, diversity, inclusion (EDI) and social accountability driven program of research which focuses on cross-sectorial and transdisciplinary scholarship where meaningful community engagement is at the core. It does not include any data analysis on any primary or secondary data.

References

- 1.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-Based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health 2010;100 Suppl 1:S40–6. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Institutes of Health Research . Guide to knowledge translation planning at CIHR: integrated and end-of-grant approaches, 2015. Available: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45321.html [Accessed 15 Jul 2020].

- 3.Jull J, Giles A, Graham ID. Community-Based participatory research and integrated knowledge translation: advancing the co-creation of knowledge. Implement Sci 2017;12:1–9. 10.1186/s13012-017-0696-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turin TC, Chowdhury N, Haque S, et al. Meaningful and deep community engagement efforts for pragmatic research and beyond: engaging with an immigrant/racialised community on equitable access to care. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006370. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowdhury N, Naeem I, Ferdous M, et al. Unmet healthcare needs among migrant populations in Canada: exploring the research landscape through a systematic integrative review. J Immigr Minor Health 2021;23:353–72. 10.1007/s10903-020-01086-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed S, Shommu NS, Rumana N, et al. Barriers to access of primary healthcare by immigrant populations in Canada: a literature review. J Immigr Minor Health 2016;18:1522–40. 10.1007/s10903-015-0276-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanney S, Boaz A, Jones T. Health services and delivery research. in: engagement in research: an innovative three-stage review of the benefits for health-care performance. Southampton, UK: NIHR Journals Library, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health 1998;19:173–202. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turin TC, Rashid R, Ferdous M, et al. Perceived challenges and unmet primary care access needs among Bangladeshi immigrant women in Canada. J Prim Care Community Health 2020;11:215013272095261. 10.1177/2150132720952618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turin TC, Rashid R, Ferdous M, et al. Perceived barriers and primary care access experiences among immigrant Bangladeshi men in Canada. Fam Med Community Health 2020;8:e000453. 10.1136/fmch-2020-000453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turin TC, Haque S, Chowdhury N, et al. Overcoming the challenges faced by immigrant populations while accessing primary care: potential solution-oriented actions advocated by the Bangladeshi-Canadian community. J Prim Care Community Health 2021;12:215013272110101. 10.1177/21501327211010165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turin TC, Haque S, Chowdhury N, et al. Community-Driven prioritization of primary health care access issues by Bangladeshi-Canadians to guide program of research and practice. Fam Community Health 2021;44:292–8. 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turin TC, Chowdhury N, Ekpekurede M, et al. Professional integration of immigrant medical professionals through alternative career pathways: an Internet scan to synthesize the current landscape. Hum Resour Health 2021;19:51. 10.1186/s12960-021-00599-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turin TC, Chowdhury N, Ekpekurede M, et al. Alternative career pathways for international medical graduates towards job market integration: a literature review. Int J Med Educ 2021;12:45–63. 10.5116/ijme.606a.e83d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scotiabank economic resilience research fund. Mitacs Canada. Available: https://www.mitacs.ca/en/scotiabank-economic-resilience-research-fund [Accessed 11 Nov 2021].

- 16.Shier ML, Handy F. Research trends in nonprofit graduate studies: a growing interdisciplinary field. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 2014;43:812–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Worth MJ. Nonprofit management: principles and practice. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistics Canada . Canada’s non-profit sector in macro-economic terms. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/13-015-x/2009000/sect05-eng.htm#note3 [Accessed 11 Nov 2021].

- 19.Liu W, Sidhu A, Beacom AM. Social network theory. in: the International encyclopedia of media effects. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kavanaugh AL. Community networks and civic engagement: a social network approach. The Good Society 2002;11:10.1353/gso.2003.0005:17–24. 10.1353/gso.2003.0005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valtonen K. Social work with immigrants and refugees: developing a Participation-based framework for Anti-Oppressive practice. Br J Soc Work 2001;31:955–60. 10.1093/bjsw/31.6.955 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations . Handbook on non-profit institutions in the system of national accounts. New York, NY: United Nations, 2003. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/seriesf/seriesf_91e.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alberta Ministry of Labour . Alberta wage and salary survey. Nonprofit sector summary report, 2019. Available: https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/fe9dab7c-a3cd-4a88-af30-9d2d89b70672/resource/afab4090-716f-4e99-b9d8-3961ea0ee89d/download/lbr-alberta-wage-salary-survey-nonprofit-sector-summary-report-2019.pdf [Accessed 24 Aug 2021].

- 25.Shommu NS, Ahmed S, Rumana N, et al. What is the scope of improving immigrant and ethnic minority healthcare using community navigators: a systematic scoping review. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:6. 10.1186/s12939-016-0298-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camden C, Shikako-Thomas K, Nguyen T, et al. Engaging stakeholders in rehabilitation research: a scoping review of strategies used in partnerships and evaluation of impacts. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37:1390–400. 10.3109/09638288.2014.963705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoekstra F, Mrklas KJ, Khan M, et al. A review of reviews on principles, strategies, outcomes and impacts of research partnerships approaches: a first step in synthesising the research partnership literature. Health Res Policy Syst 2020;18:10.1186/s12961-020-0544-9:1–23. 10.1186/s12961-020-0544-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien M, Cancino B, Apasu F, et al. Mobilising knowledge on newcomers: engaging key stakeholders to establish a research hub for Alberta. Gateways 2020;13:7208. 10.5130/ijcre.v13i1.7208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han H-R, Xu A, Mendez KJW, et al. Exploring community engaged research experiences and preferences: a multi-level qualitative investigation. Res Involv Engagem 2021;7:10.1186/s40900-021-00261-6:1–9. 10.1186/s40900-021-00261-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no data in this work.