Abstract

The mammalian SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (mSWI/SNF) family of ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling enzymes are established co-regulators of gene expression. mSWI/SNF complexes can be assembled into three major subfamilies: BAF (BRG1 or BRM-Associated Factor), PBAF (Polybromo containing BAF), or ncBAF (non-canonical BAF) that are distinguished by the presence of mutually exclusive subunits. The mechanisms by which each subfamily contributes to the establishment or function of specific cell lineages are poorly understood. Here, we determined the contributions of the BAF, ncBAF, and PBAF complexes to myoblast proliferation via knock down (KD) of a distinguishing subunits from each complex. KD of subunits unique to the BAF or the ncBAF complexes reduced myoblast proliferation rate, while KD of PBAF-specific subunits did not affect proliferation. RNA-seq from proliferating KD myoblasts targeting Baf250A (BAF complex), Brd9 (ncBAF complex), or Baf180 (PBAF complex) showed mis-regulation of a limited number of genes. KD of Baf250A specifically reduced the expression of Pax7, which is required for myoblast proliferation, concomitant with decreased binding of Baf250A to and impaired chromatin remodeling at the Pax7 gene promoter. Although Brd9 also bound to the Pax7 promoter, suggesting occupancy by the ncBAF complex, no changes were detected in Pax7 gene expression, Pax7 protein expression or chromatin remodeling at the Pax7 promoter upon Brd9 KD. The data indicate that the BAF subfamily of the mSWI/SNF enzymes is specifically required for myoblast proliferation via regulation of Pax7 expression.

Keywords: SWI/SNF, proliferation, Baf250A, Pax7, myoblasts

INTRODUCTION

Mammalian SWI/SNF (mSWI/SNF) enzymes are ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling enzymes [1–3]. These large, multi-protein complexes bind to chromatin and induce a conformational change in nucleosomal DNA that can result in the binding or removal of a DNA-binding factor, eviction of the histones, and/or sliding of the DNA relative to the nucleosome, resulting in new positioning of the nucleosome along the DNA [1, 4, 5]. The biological consequences of mSWI/SNF enzyme function are significant. Transcription, splicing, DNA repair and DNA recombination have all been shown to be facilitated by mSWI/SNF enzymes [6–12]. Consequently, cell cycle progression, development and differentiation, senescence, maintenance of cell identity, and most other cellular processes can be regulated, at least in part, by mSWI/SNF enzymes [13–30]. The importance of mSWI/SNF function is also reflected in evidence that up to 20% of all human cancers contain mutations in human SWI/SNF subunit genes [31].

Since the first reported purifications of mSWI/SNF enzymes, it has been known that there are chromatographically separable active complexes in mammalian cells [1–3]. The determination that the two closely related ATPases associated with mSWI/SNF enzymes, BRG1 and BRM [32–34] are mutually exclusive suggested a mechanism by which different complexes might be organized, but the presence of a particular ATPase did not correlate with chromatographic behavior [3]. Instead, subsequent identification and characterization of mSWI/SNF subunits identified “complex-specific” subunits that allowed an array of differently assembled enzyme complexes and distinction between different complexes, which have been termed BAF (Brg1- or Brm-Associated Factors), PBAF (polybromo containing BAF) and, more recently, ncBAF (non-canonical BAF) [35]. A recent study characterized the order of subunit assembly in each of these three types of enzyme subfamilies, documenting core subunits to which subfamily specific subunits were added prior to addition of the ATPase [35].

Though the ATPase and chromatin remodeling enzymatic properties of different mSWI/SNF subfamilies appear to be similar, the existence of multiple variations of the mSWI/SNF enzymes suggest functional distinctions. However, there is limited information about functional distinctions between the different enzyme subfamilies. For example, Brd9, a subunit of the ncBAF complex, is required for androgen receptor signaling and prostate cancer progression [36] and has been shown to maintain gene expression in rhabdoid cancers lacking the Snf5 (SMARCB1) subunit of the BAF and PBAF subfamilies of mSWI/SNF enzymes [37]. PBAF enzymes have been specifically linked to aspects of DNA repair [38, 39]. BAF, but not PBAF enzymes, have been identified as specific mediators of the glucocorticoid response [40].

mSWI/SNF enzymes play critical roles in the development and differentiation of most mammalian tissues [14, 17, 22–27, 29, 30, 41]. Significant efforts have been made to investigate mSWI/SNF function in muscle formation. Smooth muscle cells require core mSWI/SNF subunits as well as the ATPase subunits [42–47], but to date there is no information distinguishing between the major subfamilies of enzymes. Assessment of heart muscle development via animal modeling approaches determined that Baf180 (polybromo)- and Baf200 (ARID2)-deficient mice are embryonic lethal with multiple heart development defects, indicating a requirement for PBAF enzymes in heart morphogenesis [48, 49]. Examination of Baf250A, which is specific to the BAF complexes, at later times of embryonic development indicated a requirement during the differentiation of cardiac progenitor cells into cardiomyocytes [50]. Thus, cardiac muscle development requires both BAF and PBAF enzymes. Whole animal knockout of Baf250A in mice resulted in an absence of mesoderm [30], indicating its critical role in early germ-layer formation and a requirement for Baf250A in the initial formation of all mesoderm-derived tissues. This work consequently raised the question of whether Baf250A and BAF enzymes are required just for germ layer formation and therefore are indirectly required for subsequent tissue development and differentiation or whether mSWI/SNF enzymes are actively involved in specific tissue differentiation events.

Investigations into mSWI/SNF function in skeletal muscle differentiation has largely concentrated on the requirement and roles for the ATPase subunits. Inducible expression of ATPase-deficient Brg1 or Brm inhibited chromatin remodeling at and the expression of many myogenic genes, with direct involvement of the enzymes at early and late stages of the temporal cascade of myogenic gene expression that occurs during differentiation[19, 51–55]. Functional distinctions between the Brg1 and Brm enzymes in regulating gene expression were later reported [21]. Baf60c, a core subunit shared by BAF, PBAF and ncBAF complexes, is required for both heart and skeletal muscle development during mouse embryogenesis [56] and plays a critical role in targeting mSWI/SNF enzymes to myogenic promoters [57]. Snf5, a core subunit shared by BAF and PBAF, and Baf53a, a component of all three major subfamilies, also contribute to the activation of the myogenic differentiation program [58].

mSWI/SNF enzymes also play functional roles during myoblast proliferation. The Brg1 ATPase and the Snf5 subunits contribute to myoblast cell cycle progression, and knockdown of Brg1 in primary myoblasts induced cell death [24, 58]. Brg1 is required to maintain the expression of Pax7, a transcription factor that supports proliferation and the survival of myoblasts [24], at least in part through the action of casein kinase 2-mediated regulation of Brg1 phosphorylation [23]. To understand the specific contributions of BAF, PBAF and ncBAF enzymes to myoblast proliferation, we used short hairpin RNA (shRNA) to knock down the expression of individual mSWI/SNF enzyme subunits that are unique to each subfamily of complex. We assessed the proliferation capabilities of myoblasts upon KD of each of the subunits by cell counting and viability assays, cell cycle analyses, and western blots of marker proteins. Our data show that the BAF and the ncBAF enzymes are required for myoblast proliferation under conditions that support cell proliferation and that both contribute to successful re-entry into the cell cycle following release from a nocodazole-induced mitotic block. We identified Pax7 as a target of BAF, but not ncBAF complexes. Mechanistic assessment of the regulation of Pax7 expression determined that both Baf250A and Brd9 bound to the Pax7 promoter but confirmed that only Baf250A was required chromatin remodeling at the Pax7 promoter and for Pax7 expression. Knockdown of proteins specific to the PBAF subfamily of enzymes demonstrated that they were dispensable for myoblast proliferation. This work provides functional and mechanistic distinction between the different subfamilies of mSWI/SNF enzyme during myoblast proliferation and identifies the BAF complex as the critical contributor to Pax7 expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies -

Hybridoma supernatants against Pax7 were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa; deposited by A. Kawakami). Mouse anti-BRD7 (B-8; sc-376180) antibody and normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies. Rabbit anti-PBRM (Baf180; A0334), - ARID2 (Baf200, A8601), -Baf250A (A16648), -vinculin (A2752), -DPF2 (A13271), GAPDH (A19056) and β-tubulin (AC008) were from Abclonal Technologies. The rabbit anti-Caspase-3 antibody was from Cell Signaling Technologies (9662). The rabbit anti-Brd9 and -GLTSCR1L antibodies and the secondary HRP-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies were from Invitrogen (PA5-113488, PA5-56126, 31430, and 31460, respectively).

Cell culture –

The C2C12 cell line is a karyotypically abnormal subclone of a spontaneously immortalized mouse skeletal myoblast line that is used as a model for myoblast proliferation and differentiation. HEK293T cells are HEK293 cells transformed with the SV40 large T antigen that is highly effective at generating high titer retroviral preparations. C2C12 and HEK293T cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and were maintained at sub-confluent densities in proliferation media containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. We used proliferating myoblasts incubated with 1 μM of staurosporine for 24 h as the positive control for apoptosis [59, 60] as indicated in the figures.

Virus production for shRNA transduction of C2C12 cells -

Mission plasmids (Sigma) encoding a control sequence shRNA (scr) and two different shRNA against Brd7, Brd9, Baf180, Baf200, Baf250A, Dpf2 and GLTSCR1L (Supplementary Table 1) were isolated by using the Pure yield plasmid midiprep system (Promega) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The doxycycline-inducible lentiviral human PAX7 ORF with a FLAG-tag and neomycin resistance cassette and empty control vectors were purchased from Addgene. The pINDUCER20-FLAG-hPAX7 (#734) was a gift from Matthew Alexander & Louis Kunkel (Addgene plasmid # 78339; http://n2t.net/addgene:78339; RRID:Addgene_78339) and the empty control vector pINDUCER20 was a gift from Stephen Elledge (Addgene plasmid # 44012; http://n2t.net/addgene:44012; RRID:Addgene_44012) [61].

Lentiviral particles were produced using the corresponding shRNA or p-INDUCER vectors (15 μg) and the packing vectors pLP1 (15 μg), pLP2 (6 μg), pSVGV (3 μg) were transfected using lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher) into HEK293T cells for lentiviral production. After 24 and 48 h, the supernatants containing viral particles were collected and filtered using a 0.22 μm syringe filter (Millipore). Proliferating C2C12 myoblasts were transduced with lentivirus in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene and selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin (Invitrogen) and 3 mg/ml G418 (Gibco). Transduced myoblasts were maintained with 1 μg/ml puromycin or 1 mg/ml neomycin as needed.

Cell proliferation and trypan blue cell viability assays -

C2C12 myoblasts were seeded at 1X104 cells/cm2, and samples were collected 24, 48, and 72 h after plating. The cells were trypsinized, washed three times with PBS, and counted using a Cellometer Spectrum (Nexcelcom Biosciences). To determine cell viability, the myoblasts were collected at 48 h after plating and stained with 0.4% Trypan Blue (Sigma) diluted in PBS for 5 min at RT. Cell number and viability were determined using the Cellometer Spectrum, and data were analyzed with FCS Express 7 software (De Novo Software).

Cell cycle analyses -

C2C12 myoblasts (1X106 cells) were arrested in mitosis with 500 nM nocodazole for 16 h and released by washing with PBS and cultured with medium with 10% FBS for an additional 20 h. To arrest C2C12 myoblasts in G1/S phase the cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma Aldrich) for 10 h [62, 63] and released by washing with PBS and cultured with medium with 10% FBS for an additional 36 h. For both experiments, timepoints were collected as indicated in the figure legends.

Cell cycle analysis was performed using a standard propidium iodide (PI)-based cell cycle assay. Briefly, cells were trypsinized, washed three times with PBS, and fixed by slowly adding 200 μl of ice-cold 70% ethanol and incubated overnight at 4°C. Cells were then washed with PBS, and the pellet was resuspended in 50 μl PBS containing 100 μg/ ml RNAse A and 0.1% Triton X-100 and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Finally, the myoblasts were incubated with 40 μg/ml PI staining solution at 37 °C for 40 min and analyzed in a Cellometer Spectrum instrument. Data were analyzed with FCS Express 7 software.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays -

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays of C2C12 myoblasts were performed in triplicate from three independent biological samples as previously described [23, 24, 64]. Briefly, crosslinked lysates of proliferating myoblasts were incubated overnight with anti-Baf250A or anti-Brd9, or normal rabbit IgG. Crosslinking was reversed, and DNA was purified using ChIP DNA Clean and Concentrator Columns (Zymo Research) following the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed using Fast SYBR green master mix on the ABI StepOne Plus Sequence Detection System. Primers used are listed in Supplemental Table 2. Quantification was done using the comparative Ct method (ΔCT) [65] to obtain the percent of total input DNA pulled down by each antibody.

RT-qPCR gene expression analysis -

RNA was purified from three independent biological replicates of proliferating C2C12 myoblasts (controls and KDs) with TRIzol (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was performed with 500 ng of RNA as template, random primers, and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with Fast SYBR green master mix on the ABI StepOne Plus Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 2, and the delta threshold cycle value (ΔCT) [65] was calculated for each gene and represented the difference between the CT value of the gene of interest and that of the control gene, Eef1A1.

Western blot analyses -

Proliferating C2C12 (controls and KDs) myoblasts were washed with PBS and solubilized with RIPA buffer (10 mM piperazine-N,N-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid), pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 10% glycerol) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein content was determined by Bradford [66]. Twenty micrograms of each sample were prepared for SDS-PAGE by boiling in Laemmli buffer. The resolved proteins were electro-transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). The proteins of interest were detected with the specific antibodies as indicated in the figure legends and above, followed by species–specific peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and Tanon chemiluminescence detection system (Abclonal Technologies).

Immunocytochemistry -

Proliferating C2C12 myoblasts (control and KDs) were fixed overnight in 10% formalin-PBS at 4 °C. Cells were washed with PBS and permeabilized for 10 min with PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100. Immunocytochemistry was performed using the Pax7 hybridoma supernatant. Samples were developed with the universal ABC kit (Vector Labs) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Images were acquired with an Echo Rebel microscope using the 20X objective (Echo).

RNA-Seq and data analysis.

Total RNA from C2C12 cells transduced with scr or shRNA-2 against Baf250A, Brd9 or Baf180 was isolated from proliferating cultures with TRIzol and frozen at −80 °C until analysis. Independent replicates for each sample were evaluated for quality and concentration at the Molecular Biology Core Lab at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School. Quality Control-approved samples were submitted to BGI Genomics for library preparation and sequencing. Libraries were sequenced using the BGISEQ-500 platform and reads were filtered to remove adaptor-polluted, low quality and high content of unknown base reads. About 99% of the raw reads were identified as clean reads (~65M). The resulting reads were mapped onto the reference mouse genome (mm10) using HISAT [67]. Transcripts were reconstructed using StringTie [68], and novel transcripts were identified using Cufflinks [69], and combined and mapped to the mm 10 reference transcriptome using Bowtie2 [70]. Gene expression levels were calculated using RSEM [71]. DEseq2 [72] and PoissonDis [73] algorithms were used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEG). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed on DEGs to cluster genes into function-based categories.

Restriction enzyme accessibility assay -

Nuclei from three independent biological replicates of proliferating myoblasts were isolated following the Rapid, Efficient And Practical (REAP) method for subcellular fractionation of primary and transformed human cells in culture, with minor modifications [74]. Briefly, the cells were resuspended in PBS buffer containing 0.1% NP-40 and cells were disrupted by pipetting with a P1000 micropipette. The nuclei were separated from cytoplasm by centrifuging the samples 10 sec at 4000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pelleted nuclei were washed with ice cold PBS containing protease inhibitors. Nuclear integrity was verified using a microscope [74]. Restriction enzyme accessibility assays (REAA) using cultured C2C12 myoblasts were performed as described [75] using the PvuII restriction enzyme and the primers described in Supplementary Table 2, as previously reported [24]. Drawings were created with BioRender.com

Statistical analysis -

Statistical analyses were performed using Kaleidagraph (Version 4.1) or Graph Pad Prism 7.0b. Multiple data point comparisons and statistical significance were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-test. Experiments where p<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

The BAF complex is the primary regulator of C2C12 myoblast proliferation

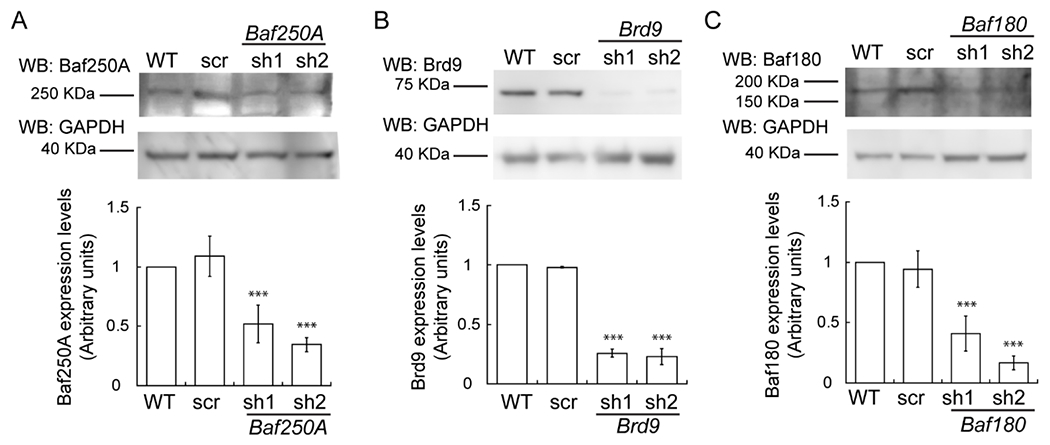

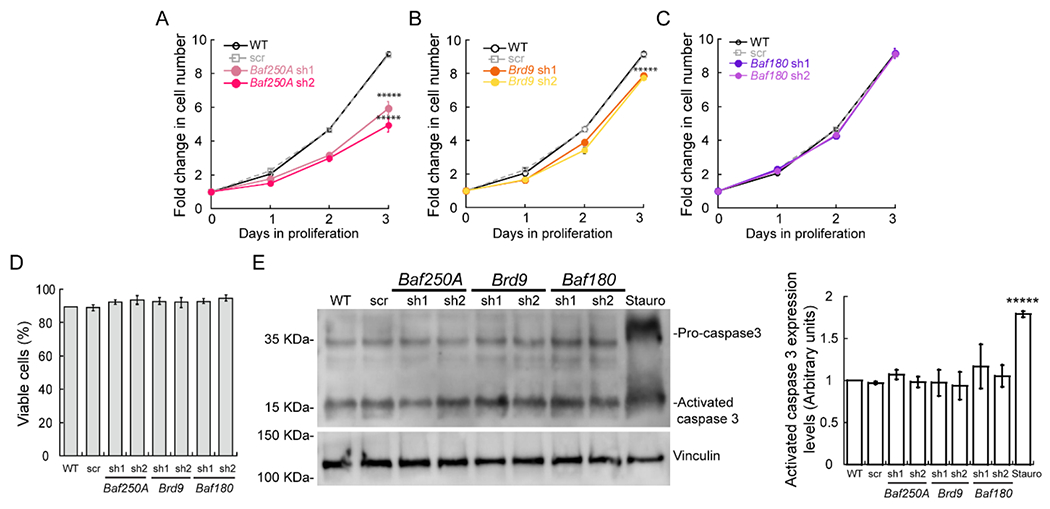

Recent studies have identified the BAF, PBAF, and the ncBAF complexes as the three major subfamilies of the mSWI/SNF enzyme [35]. While it is known that mSWI/SNF enzymes are required for myoblast proliferation [24], the roles of the enzyme subfamilies have not been determined. To address this question, we used a lentiviral system to KD distinguishing subunits for each of the complexes in proliferating C2C12 myoblasts. In all cases, the transduction of C2C12 myoblasts with specific shRNAs against Baf250A and Dpf2 (BAF), Brd9 and GLTSCR1L (ncBAF), Baf180, Baf200, and Brd7 (PBAF) resulted in a significant reduction of the expression of the targeted mSWI/SNF subunit, as shown by western blot and densitometric analyses of three independent biological replicates (Fig. 1A–C; Fig. S1A, S2A, S3A,B). To identify the contributions of each of the mSWI/SNF complexes in the proliferation of C2C12 myoblasts, the cells were cultured in growth media for three days, and the proliferation rate was determined by cell counting. We detected a significant decrease in cell numbers in the Baf250A KD myoblasts (Fig. 2A) and a small but statistically significant reduction in Brd9 KD myoblasts (Fig. 2B). No differences in cell proliferation were detected in myoblasts subjected to Baf180 KD (Fig. 2C). To confirm the results obtained with the Baf250A, Brd9 and Baf180 KDs, we repeated the experiments by knocking down Dpf2, GLTSCR1L and Brd7 or Baf200, respectively. The Dpf2 KD (Fig. S1B) and the GLTSCR1L KD (Fig. S2B) also affected cell growth, while the Brd7 or Baf200 KD had no effect on myoblast proliferation (Fig. S3C,D). Quantification of Trypan Blue staining demonstrated that the viability of myoblasts subjected to knockdown of the subunits tested was comparable to that of the non-transduced and scramble shRNA controls (Fig. 2D; Fig. S1C, S2C, S3E). Consistently, western blot analyses against pro- and activated-caspase 3 showed that there were no changes in the expression of activated caspase 3 in any of the KDs tested (Fig. 2E). Myoblasts cultured with toxic concentrations of staurosporine for 24 h were used as a positive control for the activation of caspase 3. The data indicate that the BAF and ncBAF enzymes regulate myoblast proliferation, while the PBAF complex is dispensable. Contrary to the effect of deleting Brg1 in myoblasts, which greatly reduced cell viability [24], knockdown of Baf250A or Brd9 did not result in cell death.

Figure 1. Baf250A, Brd9 and Baf180 expression in proliferating wild type (WT), shRNA scrambled sequence (scr) controls, and shRNA knockdown C2C12 myoblasts.

Representative immunoblot (top) and quantification (bottom) of Baf250A (A), Brd9 (B), and Baf180 (C) levels in proliferating cells after 48 h of proliferation. For all samples, data are the mean ± SE of three independent biological replicates. Immunoblots against GAPDH were used as loading controls. Samples were compared to the corresponding wild type sample. ***P < 0.001

Figure 2. Knockdown of Baf250A impairs myoblast proliferation while Brd9 knockdown has a minor effect.

Cell counting assay of proliferating wild type (WT) myoblasts, myoblasts transduced with scrambled shRNA (shRNA scr), Baf250A (A), Brd9 (B) or Baf180 (C) shRNAs. (D) Trypan blue staining showed no changes in viability upon knockdown of Baf250A, Brd9 or Baf180. (E) Representative immunoblot of pro-caspase 3 and activated Caspase 3 in control and knockdown proliferating myoblasts after 2 days of proliferation. Vinculin was used as loading control and treatment with 1 μM staurosporine for 24 h was used as a positive control for apoptosis induction. (F) Quantification of activated caspase 3 protein expression. All quantified data are the mean ± SE for three independent experiments. *****p < 0.00001.

The BAF and ncBAF complexes regulate cell cycle progression in myoblasts

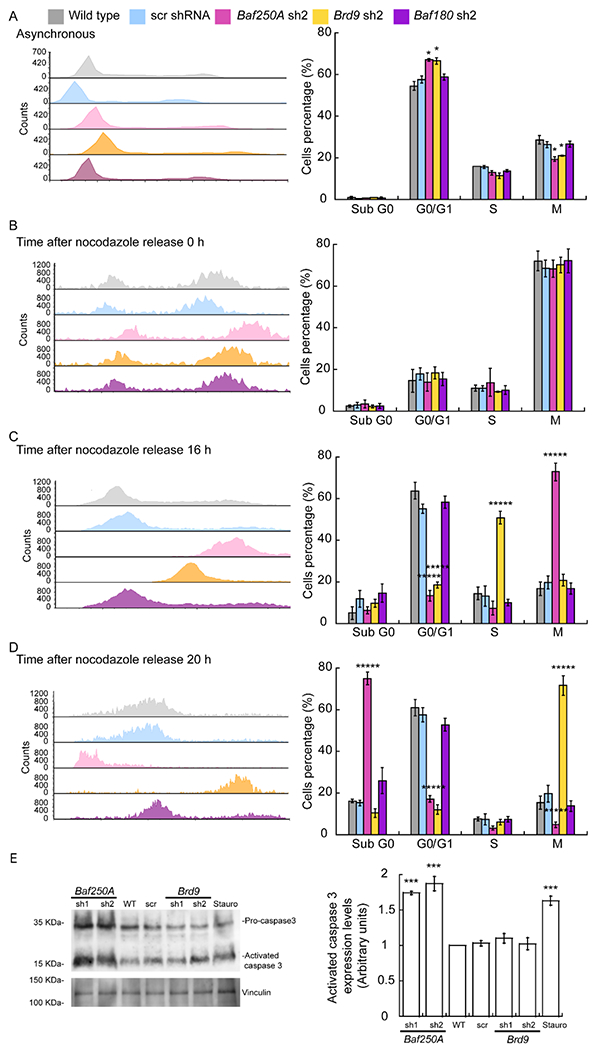

Studies in mammalian cells showed that the mSWI/SNF complexes play essential roles in cell cycle control through the transcriptional regulation of cell-cycle-specific genes [16]. Considering the reduction in proliferation rate observed in myoblasts partially depleted of the BAF subunits, Baf250A and Dpf2, and the ncBAF subunits, Brd9 and GLTSCR1L, we sought additional evidence of defects related to cell cycle progression. In asynchronous proliferating C2C12 myoblasts KD for Baf250A and Brd9, cell cycle analysis showed an increase in the population of cells in the G0/G1 phase and a corresponding decrease in the number of mitotic cells (Fig. 3A). No significant differences were detected in asynchronous Baf180 KD myoblasts when compared to wild-type and scramble controls (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Knockdown of Baf250A or Brd9 alters progression of cell cycle.

Representative histograms of cell cycle progression (left panels) and percentage of cells in each cell cycle phase (right panel) for asynchronous myoblasts (A), cells arrested in mitosis with nocodazole at the time of release (B), and after 16 h (C) and 20 h post-release (D). The data are representative of 4 independent biological experiments, *****P < 0.00001. (E) Representative immunoblot of pro-caspase 3 and activated caspase 3 in control and Baf250A or Brd9 KD cells knockdown 20 h after nocodoazole release. Vinculin was used as loading control. Treatment with 1 μM staurosporine for 24 h was used as a positive control for apoptosis induction. (F) Quantification of activated caspase 3 protein expression. Bar graphs show the mean ± SE for three independent experiments, * P < 0.05; ***** P < 0.00001.

We subsequently evaluated the ability of the myoblasts to re-enter the cell cycle after inducing mitotic arrest with nocodazole. Baf250A, Brd9, or Baf180 KD did not affect the ability of nocodazole to arrest the cells in mitosis (Fig. 3B). Baf250A, but not Brd9 KD cells largely remained in M phase at 8 h post-release (Fig. 3C). The Baf250A KD cells remained arrested in mitosis at 16h post-release and then appeared in the sub-G0 fraction at 20 h post-release, indicating cell death (Fig. 3D–E). An increase in the expression of activated caspase 3 was observed in these cells (Fig. 3F), suggesting that apoptosis had occurred. These data suggest there is a point of no return when the myoblasts containing reduced levels of the BAF complex are unable to exit mitosis and can no longer prevent cell death.

The other two KD myoblasts were able to survive after exiting mitosis. The Brd9 KD myoblasts showed an increase in the rate of cell cycle progression upon release from nocodazole block compared to the controls (Fig. 3B–D). This result suggests that Brd9 may be a repressor of some gene or process that is required to recover from nocodazole release and that is not part of the cell cycle in proliferating cells. In contrast, synchronized myoblasts knocked down for Baf180 showed a similar progression as wild-type and scramble controls (Fig. 3B–D). The data support the conclusion that the BAF and ncBAF complexes contribute to myoblast cell cycle progression, though the different complexes have different roles under different conditions. In addition, the BAF complex contributes to maintenance of the proliferating myoblast pool and cell viability under some conditions. PBAF enzymes are dispensable for these functions.

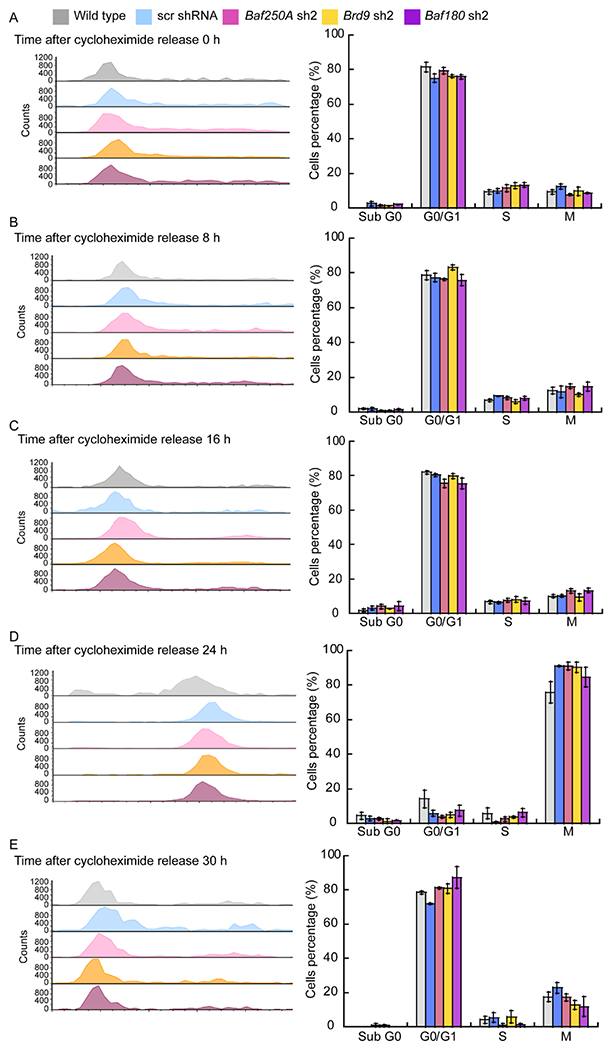

We further analyzed the effect of cell cycle arrest using cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis that has been shown to inhibit cell cycle at G1 and S [62]. Cycloheximide treatment of C2C12 myoblasts generated clear arrest in G1, even in those knocked down for Baf250A, Brd9, or Baf180 (Fig. 4A). Release from the cycloheximide block took more than 16 h (Fig. 4B–C), but analysis at 24 and 30 h post-release showed that the cells progressed to M and back to G1 without any significant difference in cell cycle progression due to KD of Baf250A, Brd9, or Baf180 (Fig. 4D–E). The results indicate that none of the mSWI/SNF complexes is required to re-enter or traverse the cell cycle following G1 arrest by cycloheximide and contrast with the inability of Baf250A or Brd9 KD myoblasts to re-enter and normally traverse the cell cycle following M phase block by nocodazole (Fig. 3).

Figure 4. Baf250A, Brd9, and Baf180 KD myoblasts re-enter the cell cycle with equivalent kinetics following a cycloheximide-induced G1 block.

Representative histograms of cell cycle progression (left panels) and the percentage of cells in each cell cycle phase (right panel) for myoblasts arrested in G1/S with cycloheximide at the time of release (A), and after 8 (B), 16 (C), 20 (D), and 30 h post-release (E). Bar graphs show the mean ± SE for three independent biological experiments.

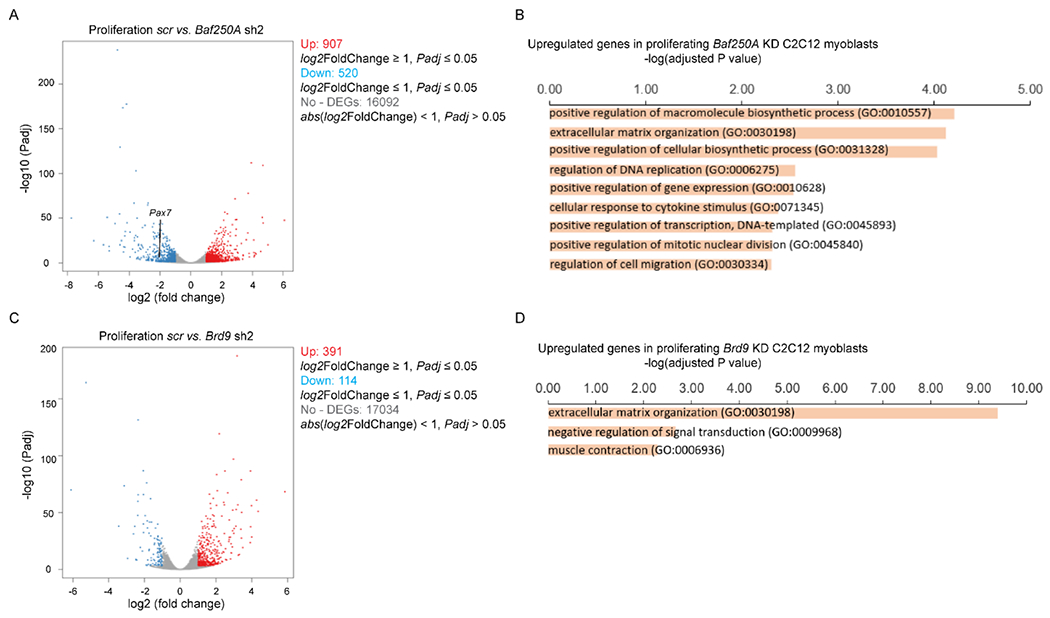

Baf250A, Brd9 or Baf180 KD modestly impacts the myoblast transcriptome

We performed RNA-seq to investigate global changes in gene expression in proliferating myoblasts transduced with either the scramble, Baf250A, Brd9 or Baf180 shRNAs. The sequenced libraries from the samples had approximately 45M total reads; unique matched reads are shown in Supp. Table 3. Reads were mapped to the mouse genome (mm10), and gene expression levels were determined. Differentially expressed genes that were significant in both replicates for each shRNA were considered for analysis (log2FoldChange <1, padj < 0.05). Replicate samples for scramble, Baf250A, Brd9 or Baf180 shRNA resulted in Pearson coefficients of >0.99 for each comparison of replicates (Supp. Table 3). Baf250A KD affected the expression of 1427 genes. Compared to gene expression in the control cells, 907 of the genes were upregulated and 520 were downregulated. (Fig. 5A, Supp. Table 4). Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed on differentially expressed genes to identify function-based categories, and the complete results are listed in Supp. Table 4. GO analyses identified no enriched categories of genes that were down-regulated, and only nine enriched categories of up-regulated genes that exceeded a cut-off of 2.0 for the -log(adjusted P value) (Fig. 5B). The top ranked categories of up-regulated genes included biosynthetic pathways and extracellular matrix organization, but regulation of DNA replication and regulation of mitotic nuclear division were also present (Fig. 5B, Supp. Table 4). Notably, the expression of the Pax7 regulator of myoblast proliferation and viability was downregulated in Baf250A KD cells compared to the controls, which is consistent with the reduced proliferation rate observed in these cells (Fig. 2A).

Figure 5. Changes in gene expression dependent on Baf250A or Brd9 knockdown.

Volcano plots displaying differentially expressed genes between scr control and Baf250A knockdown (A) or Brd9 knockdown (C) C2C12 cells. The y-axis corresponds to the mean log10 expression levels (P values). The red and blue dots represent the up- and down-regulated transcripts in Baf250A knockdown (false-discovery rate [FDR] of <0.05), respectively. The gray dots represent the expression levels of transcripts that did not reach statistical significance (FDR of >0.05). (B,D) GO term analysis of differentially expressed, up-regulated genes induced by the KD of Baf250A (B) or of Brd9 (D) in proliferating myoblasts. Cut-off was set at 2.0 of the - log(adjusted P value). No significant enrichment of downregulated GO categories were identified under these conditions. See Supp. Tables 4 and 5 for the complete list of genes.

Similar analyses of RNA-seq data for the Brd9 KD and the Baf180 KD cells were performed. A smaller number of differentially expressed genes were observed in Brd9 KD cells compared to Baf250A KD cells (Fig. 5C,D; Supp. Table 5), while there was a similar number of differentially expressed genes in the Baf180 KD cells compared to Baf250A KD cells (Supp. Fig. 3A,B; Supp. Table 6). As with the Baf250A KD cells, no enriched GO categories were identified in the down-regulated genes in Brd9 KD myoblasts. Only three enriched GO categories were identified among the Brd9 KD up-regulated genes, with genes related to extra-cellular matrix the only commonality with the Baf250A KD results. The main category identified among upregulated genes in the Baf180 KD myoblasts was related to extracellular matrix organization as well (Supp. Fig. 3B). No categories related to cell cycle were identified in either the Brd9 or Baf180 KD cells. Although the GO analyses of the RNA-seq data for Brd9 and Baf180 KD do not identify enriched gene categories related to cell cycle control as a major target for Brd9 or Baf180, we note that individual genes related to cell cycle are identified as targets of these proteins. The data also reinforce the idea that mSWI/SNF complexes play a limited, but not unimportant role in regulating the transcriptome of proliferating C2C12 myoblasts.

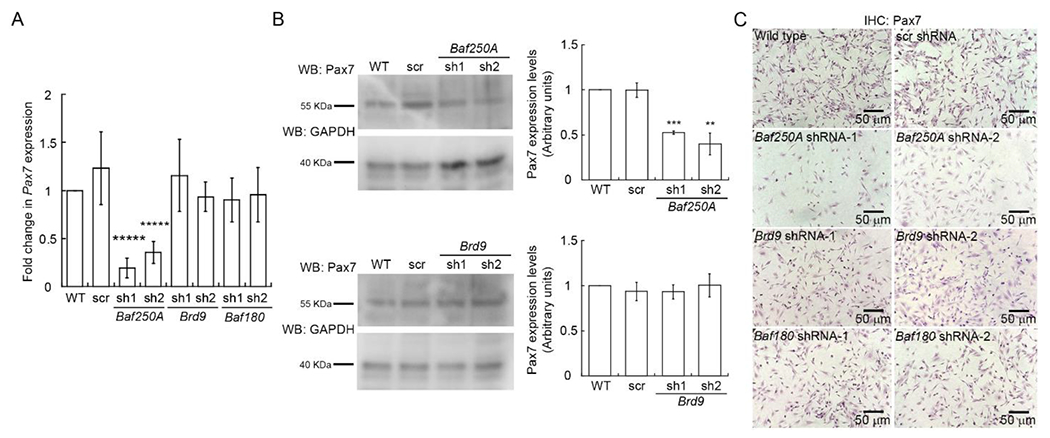

The BAF complex contributes to myoblast proliferation by regulating the expression of the Pax7 gene

Pax7 is a transcriptional regulator essential for myoblast proliferation [76–78]. Our group demonstrated that the mSWI/SNF ATPase, Brg1, regulates Pax7 expression in primary myoblasts derived from mouse satellite cells [24], and the regulation of CK2-dependent phosphorylation of Brg1 is essential to promote Pax7 expression and sustain cell proliferation [23, 24]. However, the prior work could not distinguish between subfamilies of mSWI/SNF enzyme because Brg1 can drive catalysis of all of them. Since the decrease in proliferation observed in Baf250A KD myoblasts correlated with Baf250A-dependent Pax7 expression, we investigated whether the BAF complex regulated Pax7 expression. We evaluated the expression profile of Pax7 in C2C12 cells knocked down for Baf250A, Brd9, or Baf180. We observed that Baf250A and Dpf2 KD cells showed decreased levels of Pax7 mRNA expression compared to the wild-type and scramble controls (Fig. 6A, Supp. Fig. 1). We did not detect significant changes in Pax7 expression in myoblasts knocked down for any of the ncBAF or for any of the three PBAF complex subunits tested (Fig. 6A, Supp. Fig. 2,3). In all cases, Pax7 protein expression levels correlated with the levels of mRNA expression, as shown by immunohistochemical and western blot analyses. Pax7 expression was reduced only in Baf250A KD myoblasts (Fig. 6B–C; Supp. Fig. 1D–F). The data suggest that the BAF complex specifically regulates Pax7 expression. We note that the RNA-seq data from the Brd9 KD myoblasts indicated a 3-fold increase in Pax7 mRNA expression (Supp. Table 5). We cannot explain this result. Clearly, directed analysis of Pax7 mRNA and Pax7 protein levels showed no change upon either Brd9 or GLTSCR1L KD.

Figure 6. Baf250A knockdown affects Pax7 expression.

(A) Steady state mRNA levels of Pax7 determined by qRT-PCR from proliferating C2C12 myoblasts. (B) Representative western blots showing Pax7 expression in Baf250A and Brd9 knockdown proliferating myoblasts. (C) Representative light micrographs of proliferating untreated C2C12 myoblasts (Wild type) and proliferating cells transduced with either scr, Baf250A, Brd9 or Baf180 shRNAs 48 h prior and immunostained for Pax7. Data are the mean ± SE for three independent experiments. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, *****P < 0.00001.

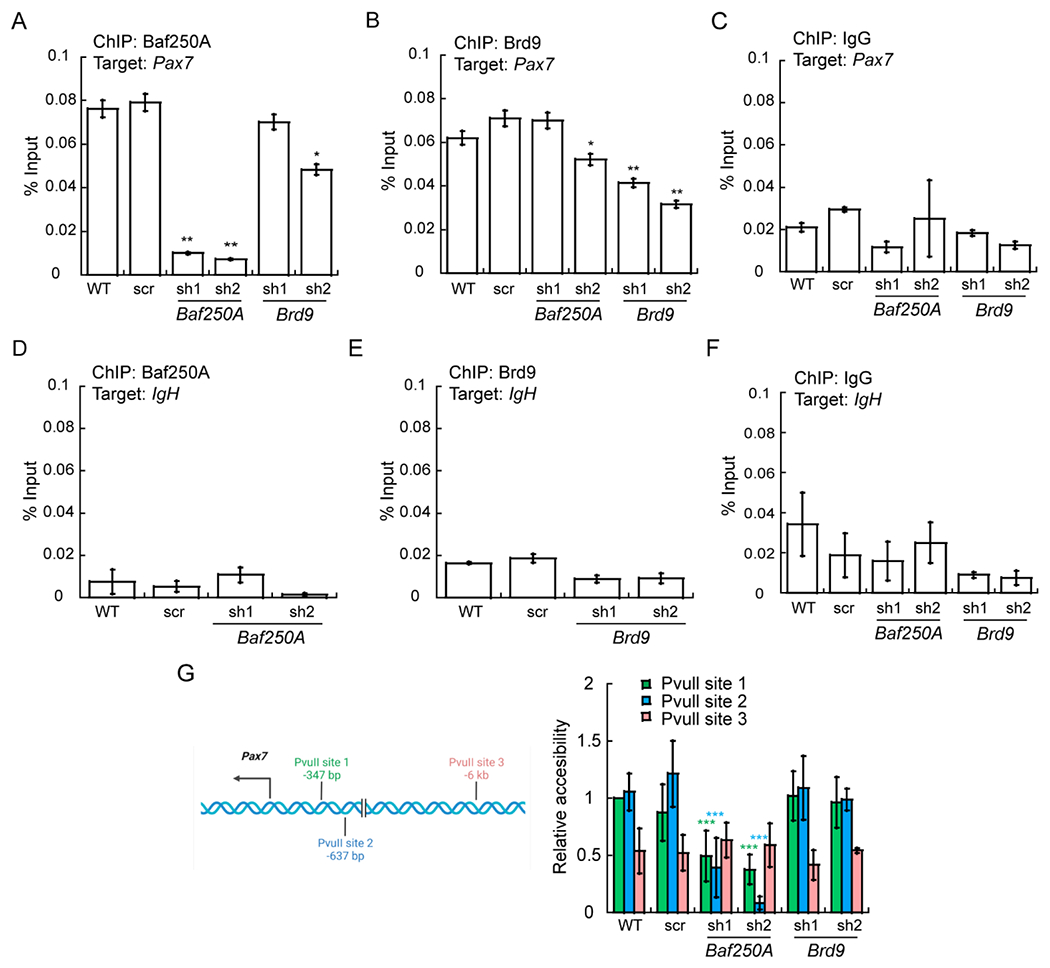

The reduction in Pax7 expression in Baf250A KD myoblasts correlated with a decrease in the binding of Baf250A to the Pax7 promoter determined by ChIP in cells knocked down for Baf250A compared to controls (Fig. 7A). IgG control pulldown is shown separately (Fig. 7C), and amplification of the IgH enhancer sequence was used as a negative sequence control (Fig. 7D–F). These data are consistent with the requirement of BAF chromatin remodeling enzyme to promote Pax7 expression and to sustain myoblast proliferation. Baf250A binding in the presence of Brd9 KD was largely unaffected (Fig. 7A). ChIP for Brd9 demonstrated that it also was localized specifically to the Pax7 promoter (Fig. 7B,C,E), despite not being required for Pax7 expression. A modest reduction in Baf250A binding to the Pax7 promoter was also detected in Brd9 KD cells that was statistically significant for one of the two shRNAs tested (Fig. 7B). However, these changes did not affect the expression of the Pax7 gene (Fig. 6), potentially due to the remaining Baf250A protein in Brd9 KD myoblasts.

Fig 7. Baf250A and Brd9 bind to the Pax7 promoter, but only Baf250A contributes to chromatin remodeling at the Pax7 promoter.

ChIP-qPCR showing binding of Baf250A (A) and Brd9 (B) binding to the Pax7 promoter. (C) The IgG control for the Pax7 promoter. (D-F) Amplification of the IgH enhancer as negative sequence control for Baf250A, Brd9, and IgG pulldowns. (G) Left panel: Schematic representation of the location of PvuII restriction enzyme sites used for restriction enzyme accessibility assays (REAA) relative to the Pax7 mRNA start site. Right panel: The accessibility of PvuII sites near the Pax7 promoter was measured by REAA relative to the accessibility of the the PvuII site proximal to the Pax7 mRNA start site in wildtype (WT) cells, which was normalized to 1. The data represent 3 independent biological experiments. *P ≤ 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We examined the function of the Baf250A and Brd9 bound to the Pax7 promoter by a restriction enzyme accessibility assay to assess local chromatin accessibility. Two Pvu II sites exist in close proximity to the Pax7 mRNA transcription start site while a third is located more than 5 kb upstream (Fig. 7G). We plotted accessibility at each of the sites and observed that chromatin accessibility at the proximal sites was compromised by Baf250A but not Brd9 KD, whereas the accessibility of the distal site was largely unchanged under all conditions (Fig. 7G). The data indicate that chromatin remodeling at the Pax7 promoter is dependent on Baf250A, and by extension, the BAF complex. These results suggest that the BAF complex enzyme contributes to the regulation of Pax7 expression by binding to and remodeling promoter sequences as a mechanism to regulate cell proliferation and maintenance in myoblasts.

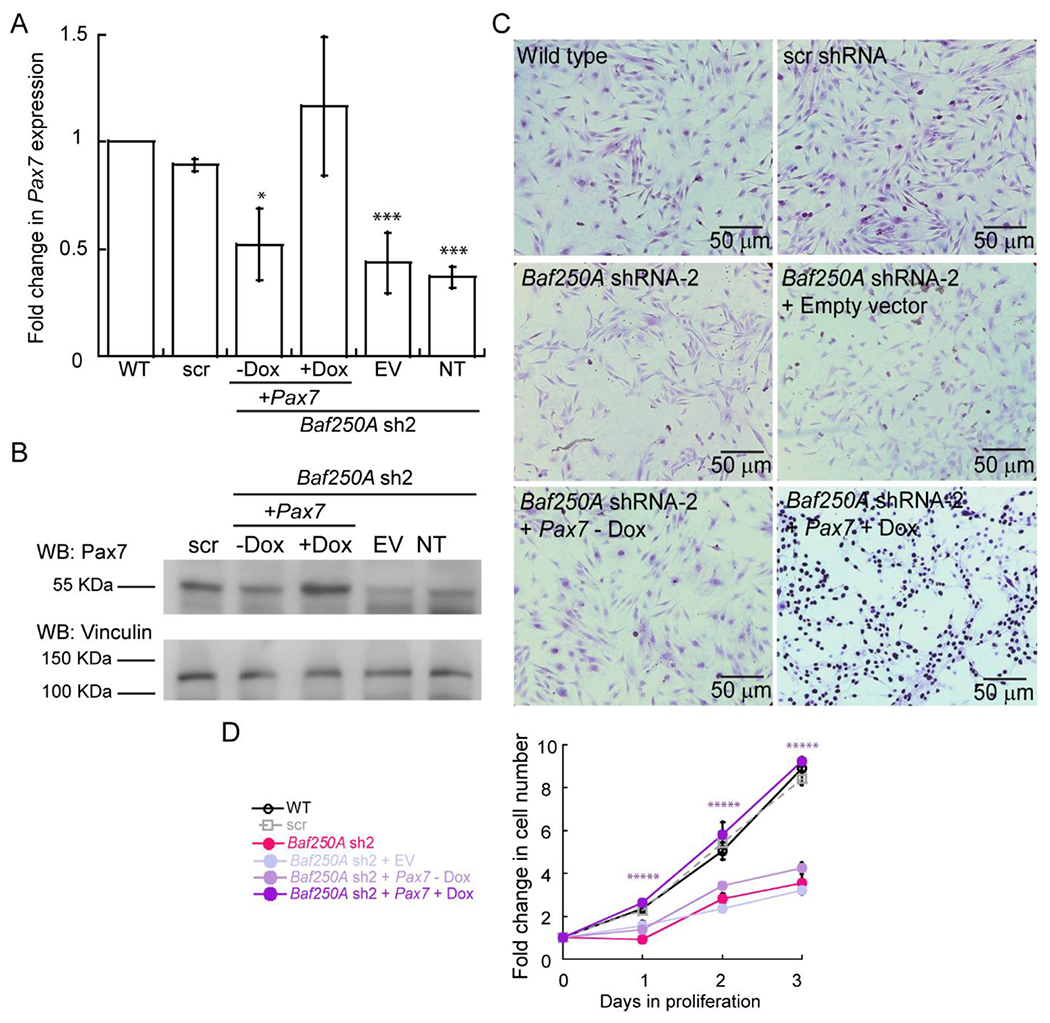

To further demonstrate that the BAF complex is required for Pax7 expression and myoblast proliferation, we asked whether expression of Pax7 in Baf250A KD cells would rescue the proliferation deficiency. A doxycycline-inducible Pax7 expression vector was introduced into Baf250A KD cells. Evaluation of Pax7 mRNA shows that the vector restored Pax7 expression in the Baf250A KD cells to the level observed in the scr shRNA control cells when doxycycline was added, but not in the absence of doxycycline and not when cells were transduced with an empty vector (EV) or not transduced (NT) (Fig. 8A). Western blots detecting Pax7 protein similarly supported the conclusion that Pax7 expression was restored (Fig. 8B). Immunocytochemistry staining for Pax7 also demonstrated restoration of Pax7 expression in cell nuclei upon transduction with the Pax7 vector in the presence of doxycycline by not in the absence of doxycycline or in the other control cells (Fig. 8C). Cell proliferation assays revealed that the expression of Pax7 in Baf250A KD cells rescued the reduction in proliferation caused by Baf250A KD (Fig. 8D). This experiment is consistent with earlier work showing that restoration of Pax7 expression in Brg1-deficient myoblasts rescued the proliferation defect caused by Brg1 deletion [24]. Altogether, the work demonstrates the requirement for mSWI/SNF enzymes and specifically the BAF complex, in driving Pax7 expression and promoting myoblast proliferation.

Figure 8. Reduced proliferation in Baf250A KD cells is rescued by re-introduction of Pax7.

(A) Relative Pax7 mRNA levels determined by qRT-PCR from the indicated proliferating myoblasts. Values are relative to the amount in the wild-type (WT) control cells, which were set at 1. (B) Representative western blots showing Pax7 protein levels in the indicated proliferating myoblasts. (C) Representative light micrographs of the indicated proliferating myoblasts stained for Pax7. (D) Cell counting assay results for the indicated myoblasts. Data are the mean ± SE for three independent experiments. * P, 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, *****P < 0.00001. NT, non-transduced, EV, empty vector, Dox, doxycycline.

DISCUSSION

BAF complex contributions to myoblast proliferation

Transcriptional regulatory proteins and chromatin remodelers such as the mSWI/SNF enzymes alter nucleosome structure in an ATP-dependent manner and regulate the accessibility of genomic DNA to the transcriptional machinery to modulate gene expression. Recently, the interactions between different mSWI/SNF enzyme subunits and the order of subunit assembly were characterized, leading to the identification of three major subfamilies of mSWI/SNF enzymes [35]. The complexity of assembly has long been proposed to be a mechanism by which diverse biological functions are mediated [79]. Here, we investigated the specific roles for the BAF, ncBAF, and PBAF complexes during myoblast proliferation by knocking down the expression of subunits that are unique to each subfamily. We report that both the BAF and the ncBAF complexes contribute to myoblast proliferation. The PBAF complex was dispensable for this function. Both the BAF and ncBAF complexes contribute to cell cycle progression, but only the BAF complex contributes to chromatin remodeling at and driving expression from the Pax7 promoter, which is required for myoblast proliferation.

Previous studies from our lab showed that the Brg1 ATPase that is common to all three subfamilies of the mSWI/SNF enzymes contributed to Pax7 expression by binding to and remodeling chromatin at the Pax7 promoter [24]. The requirement and specificity for this Brg1 function was demonstrated by the observation that re-expression of Pax7 in a Brg1 KD myoblast rescued the proliferation and viability defects caused by Brg1 KD [24]. Moreover, regulation of CK2-dependent phosphorylation of Brg1 is essential to sustain myoblast proliferation and viability [24]. Pax7 is the primary regulator of proliferation in the skeletal muscle lineage that maintains the satellite cell pools [80]. The work presented here confirms the requirement of mSWI/SNF enzymes in mediating Pax7 expression and promoting myoblast proliferation and defines BAF as the biologically relevant configuration of chromatin remodeling enzyme.

mSWI/SNF enzymes have long been linked to proliferation and cell cycle progression through regulation of genes such as p16, p21, c-Myc, cyclin D, and cyclin E [81–85]. The RNA-seq results from Baf250A KD cells identified a limited number of cell known cycle regulatory genes as significantly downregulated. In addition, review of genes mis-regulated by Baf250A knockdown identified some genes related to cytoskeleton structure and organization that enable cell cycle progression. For example, a decrease in the expression of the sodium/hydrogen exchanger, Slc9A3r1, also known as EBP50, were detected. Although its role in skeletal muscle growth is unknown, studies using siRNA-mediated deletion of this gene in primary cultured vascular smooth muscle cells suggests that EBP50 promotes proliferation via maintenance of cell architecture and cytokinesis [86, 87]. The tubulin-β 2b (Tubb2b) gene that encodes tubulin is also down-regulated, as is the Vash1 gene that encodes vasohibin-1, which regulates microtubule dynamics [88]. These data suggest that the BAF complex’s contributions to cell cycle progression may not be exclusive to activation of Pax7 and may involve the regulation of genes that are or that govern structural components of cells that are required for cell division.

ncBAF contributions to myoblast proliferation in a manner independent of Pax7 expression

A curious result was the observation that the Brd9 subunit of the ncBAF complex could bind to the Pax7 promoter. Binding was specifically reduced when Brd9 was knocked down, but Brd9 knockdown had no effect on Pax7 expression at either the mRNA or protein level (Figs. 5,6). Brd9 binding was modestly reduced in one of the two Baf250A knockdowns. Thus, there is no evidence that such binding could be compensating for Baf250A function at the Pax7 promoter. However, the presence of Brd9 and ncBAF suggests that they may have a contributing role for Pax7 expression, but if so, it is clear that there is no requirement.

The small but statistically significant decrease in proliferation rate that was observed in the Brd9 knockdown myoblasts, along with a decrease in proliferation due to GLTSCR1L KD that matched the proliferation decrease observed in the two BAF subunits KDs, suggests that the ncBAF complex contributes to myoblast proliferation via a function that is independent of Pax7. Although GO analysis of the mRNA-seq data did not identify any enriched category of Brd9-regulated genes related to cell cycle, some specific cell cycle-related genes were mis-regulated. Additionally, the mis-regulated genes in Brd9 knockdown myoblasts included the putative tumor suppressors Txnip, and Gas1 [89–91] and the Rtel1 gene that functions in telomere maintenance [92]. The exact contributions of the ncBAF complex to cell proliferation remain to be determined, but they may occur via a combination of regulation of genes of poorly understood function as well as of more classic cell cycle regulators.

PBAF does not contribute to myoblast proliferation

We generated no evidence that supports a role for PBAF in myoblast proliferation. Knockdown of three different PBAF-specific proteins, Baf180, Brd7, and Baf200, had no effect on myoblast proliferation while knockdown of Baf180 had no effect on the resumption of cell cycle following a mitotic block. These results are consistent with findings that a mouse conditionally deficient for Baf180 in adipose and skeletal muscle were born and survived to adulthood without alterations in adipose or skeletal muscle tissue development or maturation [93]. Baf180 knockdown also had no impact on myoblast differentiation in cell culture [14]. Baf180 and the PBAF complex may therefore have no role in normal skeletal muscle formation or function.

The role of mSWI/SNF enzymes in regulating transcription in proliferating myoblasts

It has been evident since the earliest characterizations that mSWI/SNF enzymes can regulate transcription by altering nucleosome structure to facilitate the interaction of transcriptional regulatory machinery [1, 2, 32, 33]. Similarly, it was soon recognized that genes that encode cell cycle regulatory proteins were among the targets of mSWI/SNF enzymes in proliferating cells of many different origins [85]. While this in many cases indicated an essential role for mSWI/SNF enzymes, it was nevertheless revealing that the first comprehensive analysis of the effects of mSWI/SNF enzymes genome-wide, where a tumor cell line deficient for the Brg1 ATPase was compare to the same cells reconstituted with Brg1, identified only ~80 target genes [94]. While this is likely an underestimate due to the use of microarrays, the technology available at the time, it nevertheless suggested that mSWI/SNF enzymes are not widely utilized for gene expression in proliferating cells. Our mRNA-seq results for different mSWI/SNF subunits seem consistent with this prior finding. Baf250A and Baf180 KD myoblasts showed ~1400 differentially expressed genes while the Brd9 KD showed only ~500, though it must be noted that our experiments were performed with stable KD cell lines; additional genes may have been identified if an acute KD had been used. Efforts to identify categories of genes or pathways among the mis-regulated genes were largely ineffective. These data by no means point to a lack of importance or requirement for mSWI/SNF enzymes in proliferating cells, and indeed in cancer cells, mSWI/SNF genes are frequently deleted, mutated, or mis-regulated and are being actively pursued as potential therapeutic targets [95].

One commonality in the limited amount of information obtained by GO analyses was the finding that KD of Baf250A, Brd9 and Baf180 in proliferating myoblasts resulted in an upregulation of genes associated with the extracellular matrix (ECM). The data indicate that all three mSWI/SNF subfamilies negatively regulate genes encoding ECM proteins, likely suggesting that the different subfamilies are functionally redundant for regulating this class of genes. Prior work has linked mSWI/SNF enzymes to regulation of ECM genes in multiple cell types [46, 96–102], though in some cases the mSWI/SNF enzymes were reported as positive regulators of ECM genes. Positive or negative modulation of ECM gene expression by mSWI/SNF enzymes may be dictated by cell-type specific ECM requirements.

CONCLUSIONS

This work highlights different roles for subfamilies of the mSWI/SNF chromatin remodeling enzymes in myoblast proliferation. The BAF and ncBAF subfamilies of mSWI/SNF enzymes contribute to myoblast proliferation but the PBAF subfamily does not. The BAF subfamily is required for myoblast proliferation due to its role in binding to and remodeling the Pax7 promoter and activating the expression of the Pax7 gene, which encodes a transcription factor that is essential for myoblast proliferation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights – Padilla-Benavides et al.

The mammalian SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (mSWI/SNF) family of ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling enzymes are co-regulators of gene expression that can be assembled into three major subfamilies: BAF (BRG1 or BRM-Associated Factor), PBAF (Polybromo containing BAF), or ncBAF (non-canonical BAF) distinguished by the presence of mutually exclusive subunits.

We determined the specific contributions of the BAF, ncBAF, and PBAF complexes to myoblast proliferation. The data indicate that the BAF subfamily of the mSWI/SNF enzymes is specifically required for myoblast proliferation via regulation of Pax7 expression.

The Baf250A subunit from the BAF complex binds to the Pax7 gene promoter and enables chromatin remodeling and the expression of the gene, which is essential for myoblast proliferation.

The Brd9 subunit, constituent of ncBAF complex also binds to the Pax7 promoter, suggesting occupancy by the ncBAF complex, but it is not required for chromatin remodeling at the Pax7 promoter, or gene or protein.

The Baf180 subunit from the PBAF complex is dispensable for the proliferation of myoblasts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by NIH grants R35GM136393 to ANI, R01AR077578 to TP-B and F32DK118846 to SAS. We thank Dr. Andreas Bergmann and members of the Imbalzano and the Padilla-Benavides labs for suggestions and comments on the manuscript.

Teresita Padilla-Benavides reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health. Anthony N. Imbalzano reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health. Sabriya A. Syed reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

ETHICS DECLARATIONS

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

DATA AVAILABILITY

RNA-seq datasets are available at GEO. The accession number is: GSE182421 (Reviewer token: ifkpasemtdqfvkd). Source data underlying figures are presented in Supplementary Tables 4–6. All other data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- [1].Kwon H, Imbalzano AN, Khavari PA, Kingston RE, Green MR, Nucleosome disruption and enhancement of activator binding by a human SW1/SNF complex, Nature, 370 (1994) 477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Imbalzano AN, Kwon H, Green MR, Kingston RE, Facilitated binding of TATA-binding protein to nucleosomal DNA, Nature, 370 (1994) 481–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang W, Cote J, Xue Y, Zhou S, Khavari PA, Biggar SR, Muchardt C, Kalpana GV, Goff SP, Yaniv M, Workman JL, Crabtree GR, Purification and biochemical heterogeneity of the mammalian SWI-SNF complex, EMBO J, 15 (1996) 5370–5382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cote J, Quinn J, Workman JL, Peterson CL, Stimulation of GAL4 derivative binding to nucleosomal DNA by the yeast SWI/SNF complex, Science, 265 (1994) 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Logie C, Peterson CL, Catalytic activity of the yeast SWI/SNF complex on reconstituted nucleosome arrays, EMBO J, 16 (1997) 6772–6782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fryer CJ, Archer TK, Chromatin remodelling by the glucocorticoid receptor requires the BRG1 complex, Nature, 393 (1998) 88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lee D, Sohn H, Kalpana GV, Choe J, Interaction of E1 and hSNF5 proteins stimulates replication of human papillomavirus DNA, Nature, 399 (1999) 487–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Murphy DJ, Hardy S, Engel DA, Human SWI-SNF component BRG1 represses transcription of the c-fos gene, Mol Cell Biol, 19 (1999) 2724–2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cai S, Lee CC, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, SATB1 packages densely looped, transcriptionally active chromatin for coordinated expression of cytokine genes, Nat Genet, 38 (2006) 1278–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Morshead KB, Ciccone DN, Taverna SD, Allis CD, Oettinger MA, Antigen receptor loci poised for V(D)J rearrangement are broadly associated with BRG1 and flanked by peaks of histone H3 dimethylated at lysine 4, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 100 (2003) 11577–11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhao Q, Wang QE, Ray A, Wani G, Han C, Milum K, Wani AA, Modulation of nucleotide excision repair by mammalian SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex, J Biol Chem, 284 (2009) 30424–30432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhang L, Zhang Q, Jones K, Patel M, Gong F, The chromatin remodeling factor BRG1 stimulates nucleotide excision repair by facilitating recruitment of XPC to sites of DNA damage, Cell Cycle, 8 (2009) 3953–3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sif S, Stukenberg PT, Kirschner MW, Kingston RE, Mitotic inactivation of a human SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, Genes Dev, 12 (1998) 2842–2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sharma T, Robinson DCL, Witwicka H, Dilworth FJ, Imbalzano AN, The Bromodomains of the mammalian SWI/SNF (mSWI/SNF) ATPases Brahma (BRM) and Brahma Related Gene 1 (BRG1) promote chromatin interaction and are critical for skeletal muscle differentiation, Nucleic acids research, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shanahan F, Seghezzi W, Parry D, Mahony D, Lees E, Cyclin E associates with BAF155 and BRG1, components of the mammalian SWI-SNF complex, and alters the ability of BRG1 to induce growth arrest, Mol Cell Biol, 19 (1999) 1460–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nagl NG Jr., Wang X, Patsialou A, Van Scoy M, Moran E, Distinct mammalian SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes with opposing roles in cell-cycle control, EMBO J, 26 (2007) 752–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lessard J, Wu JI, Ranish JA, Wan M, Winslow MM, Staahl BT, Wu H, Aebersold R, Graef IA, Crabtree GR, An essential switch in subunit composition of a chromatin remodeling complex during neural development, Neuron, 55 (2007) 201–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Klochendler-Yeivin A, Picarsky E, Yaniv M, Increased DNA damage sensitivity and apoptosis in cells lacking the Snf5/Ini1 subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, Mol Cell Biol, 26 (2006) 2661–2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].de la Serna IL, Carlson KA, Imbalzano AN, Mammalian SWI/SNF complexes promote MyoD-mediated muscle differentiation, Nat Genet, 27 (2001) 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bourachot B, Yaniv M, Muchardt C, Growth inhibition by the mammalian SWI-SNF subunit Brm is regulated by acetylation, EMBO J, 22 (2003) 6505–6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Albini S, Coutinho Toto P, Dall’Agnese A, Malecova B, Cenciarelli C, Felsani A, Caruso M, Bultman SJ, Puri PL, Brahma is required for cell cycle arrest and late muscle gene expression during skeletal myogenesis, EMBO Rep, 16 (2015) 1037–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Witwicka H, Nogami J, Syed SA, Maehara K, Padilla-Benavides T, Ohkawa Y, Imbalzano AN, Calcineurin broadly regulates the initiation of skeletal muscle-specific gene expression by binding target promoters and facilitating the interaction of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling enzyme, Mol Cell Biol, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Padilla-Benavides T, Nasipak BT, Paskavitz AL, Haokip DT, Schnabl JM, Nickerson JA, Imbalzano AN, Casein kinase 2-mediated phosphorylation of Brahma-related gene 1 controls myoblast proliferation and contributes to SWI/SNF complex composition, J Biol Chem, 292 (2017) 18592–18607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Padilla-Benavides T, Nasipak BT, Imbalzano AN, Brg1 Controls the Expression of Pax7 to Promote Viability and Proliferation of Mouse Primary Myoblasts, Journal of cellular physiology, 230 (2015) 2990–2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Padilla-Benavides T, Haokip DT, Yoon Y, Reyes-Gutierrez P, Rivera-Perez JA, Imbalzano AN, CK2-Dependent Phosphorylation of the Brg1 Chromatin Remodeling Enzyme Occurs during Mitosis, International journal of molecular sciences, 21 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nasipak BT, Padilla-Benavides T, Green KM, Leszyk JD, Mao W, Konda S, Sif S, Shaffer SA, Ohkawa Y, Imbalzano AN, Opposing calcium-dependent signalling pathways control skeletal muscle differentiation by regulating a chromatin remodelling enzyme, Nat Commun, 6 (2015) 7441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tuoc TC, Boretius S, Sansom SN, Pitulescu ME, Frahm J, Livesey FJ, Stoykova A, Chromatin regulation by BAF170 controls cerebral cortical size and thickness, Developmental cell, 25 (2013) 256–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Staahl BT, Tang J, Wu W, Sun A, Gitler AD, Yoo AS, Crabtree GR, Kinetic analysis of npBAF to nBAF switching reveals exchange of SS18 with CREST and integration with neural developmental pathways, The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 33 (2013) 10348–10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Olave I, Wang W, Xue Y, Kuo A, Crabtree GR, Identification of a polymorphic, neuron-specific chromatin remodeling complex, Genes Dev, 16 (2002) 2509–2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gao X, Tate P, Hu P, Tjian R, Skarnes WC, Wang Z, ES cell pluripotency and germ-layer formation require the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling component BAF250a, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 105 (2008) 6656–6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cyrta J, Augspach A, De Filippo MR, Prandi D, Thienger P, Benelli M, Cooley V, Bareja R, Wilkes D, Chae SS, Cavaliere P, Dephoure N, Uldry AC, Lagache SB, Roma L, Cohen S, Jaquet M, Brandt LP, Alshalalfa M, Puca L, Sboner A, Feng F, Wang S, Beltran H, Lotan T, Spahn M, Kruithof-de Julio M, Chen Y, Ballman KV, Demichelis F, Piscuoglio S, Rubin MA, Role of specialized composition of SWI/SNF complexes in prostate cancer lineage plasticity, Nat Commun, 11 (2020) 5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Khavari PA, Peterson CL, Tamkun JW, Mendel DB, Crabtree GR, BRG1 contains a conserved domain of the SWI2/SNF2 family necessary for normal mitotic growth and transcription, Nature, 366 (1993) 170–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Muchardt C, Yaniv M, A human homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SNF2/SWI2 and Drosophila brm genes potentiates transcriptional activation by the glucocorticoid receptor, EMBO J, 12 (1993) 4279–4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Muchardt C, Sardet C, Bourachot B, Onufryk C, Yaniv M, A human protein with homology to Saccharomyces cerevisiae SNF5 interacts with the potential helicase hbrm, Nucleic acids research, 23 (1995) 1127–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mashtalir N, D’Avino AR, Michel BC, Luo J, Pan J, Otto JE, Zullow HJ, McKenzie ZM, Kubiak RL, St Pierre R, Valencia AM, Poynter SJ, Cassel SH, Ranish JA, Kadoch C, Modular Organization and Assembly of SWI/SNF Family Chromatin Remodeling Complexes, Cell, 175 (2018) 1272–1288 e1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Alpsoy A, Utturkar SM, Carter BC, Dhiman A, Torregrosa-Allen SE, Currie MP, Elzey BD, Dykhuizen EC, BRD9 Is a Critical Regulator of Androgen Receptor Signaling and Prostate Cancer Progression, Cancer Res, 81 (2021) 820–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Michel BC, D’Avino AR, Cassel SH, Mashtalir N, McKenzie ZM, McBride MJ, Valencia AM, Zhou Q, Bocker M, Soares LMM, Pan J, Remillard DI, Lareau CA, Zullow HJ, Fortoul N, Gray NS, Bradner JE, Chan HM, Kadoch C, A non-canonical SWI/SNF complex is a synthetic lethal target in cancers driven by BAF complex perturbation, Nature cell biology, 20 (2018) 1410–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kakarougkas A, Ismail A, Chambers AL, Riballo E, Herbert AD, Kunzel J, Lobrich M, Jeggo PA, Downs JA, Requirement for PBAF in transcriptional repression and repair at DNA breaks in actively transcribed regions of chromatin, Molecular cell, 55 (2014) 723–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Niimi A, Hopkins SR, Downs JA, Masutani C, The BAH domain of BAF180 is required for PCNA ubiquitination, Mutation research, 779 (2015) 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Trotter KW, Archer TK, Reconstitution of glucocorticoid receptor-dependent transcription in vivo, Mol Cell Biol, 24 (2004) 3347–3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Vogel-Ciernia A, Matheos DP, Barrett RM, Kramar EA, Azzawi S, Chen Y, Magnan CN, Zeller M, Sylvain A, Haettig J, Jia Y, Tran A, Dang R, Post RJ, Chabrier M, Babayan AH, Wu JI, Crabtree GR, Baldi P, Baram TZ, Lynch G, Wood MA, The neuron-specific chromatin regulatory subunit BAF53b is necessary for synaptic plasticity and memory, Nature neuroscience, 16 (2013) 552–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zhang M, Chen M, Kim JR, Zhou J, Jones RE, Tune JD, Kassab GS, Metzger D, Ahlfeld S, Conway SJ, Herring BP, SWI/SNF complexes containing Brahma or Brahma-related gene 1 play distinct roles in smooth muscle development, Mol Cell Biol, 31 (2011) 2618–2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhou J, Zhang M, Fang H, El-Mounayri O, Rodenberg JM, Imbalzano AN, Herring BP, The SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex regulates myocardin-induced smooth muscle-specific gene expression, Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 29 (2009) 921–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sohni A, Mulas F, Ferrazzi F, Luttun A, Bellazzi R, Huylebroeck D, Ekker SC, Verfaillie CM, TGFbeta1-induced Baf60c regulates both smooth muscle cell commitment and quiescence, PLoS One, 7 (2012) e47629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Vieira JM, Howard S, Villa Del Campo C, Bollini S, Dube KN, Masters M, Barnette DN, Rohling M, Sun X, Hankins LE, Gavriouchkina D, Williams R, Metzger D, Chambon P, Sauka-Spengler T, Davies B, Riley PR, BRG1-SWI/SNF-dependent regulation of the Wt1 transcriptional landscape mediates epicardial activity during heart development and disease, Nat Commun, 8 (2017) 16034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chang Z, Zhao G, Zhao Y, Lu H, Xiong W, Liang W, Sun J, Wang H, Zhu T, Rom O, Guo Y, Fan Y, Chang L, Yang B, Garcia-Barrio MT, Lin JD, Chen YE, Zhang J, BAF60a Deficiency in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Prevents Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm by Reducing Inflammation and Extracellular Matrix Degradation, Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 40 (2020) 2494–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bi-Lin KW, Seshachalam PV, Tuoc T, Stoykova A, Ghosh S, Singh MK, Critical role of the BAF chromatin remodeling complex during murine neural crest development, PLoS genetics, 17 (2021) e1009446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].He L, Tian X, Zhang H, Hu T, Huang X, Zhang L, Wang Z, Zhou B, BAF200 is required for heart morphogenesis and coronary artery development, PLoS One, 9 (2014) e109493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wang Z, Zhai W, Richardson JA, Olson EN, Meneses JJ, Firpo MT, Kang C, Skarnes WC, Tjian R, Polybromo protein BAF180 functions in mammalian cardiac chamber maturation, Genes Dev, 18 (2004) 3106–3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lei I, Gao X, Sham MH, Wang Z, SWI/SNF protein component BAF250a regulates cardiac progenitor cell differentiation by modulating chromatin accessibility during second heart field development, J Biol Chem, 287 (2012) 24255–24262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].de la Serna IL, Ohkawa Y, Berkes CA, Bergstrom DA, Dacwag CS, Tapscott SJ, Imbalzano AN, MyoD targets chromatin remodeling complexes to the myogenin locus prior to forming a stable DNA-bound complex, Mol Cell Biol, 25 (2005) 3997–4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ohkawa Y, Yoshimura S, Higashi C, Marfella CG, Dacwag CS, Tachibana T, Imbalzano AN, Myogenin and the SWI/SNF ATPase Brg1 maintain myogenic gene expression at different stages of skeletal myogenesis, J Biol Chem, 282 (2007) 6564–6570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ohkawa Y, Marfella CG, Imbalzano AN, Skeletal muscle specification by myogenin and Mef2D via the SWI/SNF ATPase Brg1, EMBO J, 25 (2006) 490–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Simone C, Forcales SV, Hill DA, Imbalzano AN, Latella L, Puri PL, p38 pathway targets SWI-SNF chromatin-remodeling complex to muscle-specific loci, Nat Genet, 36 (2004) 738–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Mallappa C, Nasipak BT, Etheridge L, Androphy EJ, Jones SN, Sagerstrom CG, Ohkawa Y, Imbalzano AN, Myogenic microRNA expression requires ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling enzyme function, Mol Cell Biol, 30 (2010) 3176–3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lickert H, Takeuchi JK, Von Both I, Walls JR, McAuliffe F, Adamson SL, Henkelman RM, Wrana JL, Rossant J, Bruneau BG, Baf60c is essential for function of BAF chromatin remodelling complexes in heart development, Nature, 432 (2004) 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Forcales SV, Albini S, Giordani L, Malecova B, Cignolo L, Chernov A, Coutinho P, Saccone V, Consalvi S, Williams R, Wang K, Wu Z, Baranovskaya S, Miller A, Dilworth FJ, Puri PL, Signal-dependent incorporation of MyoD-BAF60c into Brg1-based SWI/SNF chromatin-remodelling complex, EMBO J, 31 (2012) 301–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Joliot V, Ait-Mohamed O, Battisti V, Pontis J, Philipot O, Robin P, Ito H, Ait-Si-Ali S, The SWI/SNF subunit/tumor suppressor BAF47/INI1 is essential in cell cycle arrest upon skeletal muscle terminal differentiation, PLoS One, 9 (2014) e108858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Szewczyk A, Saczko J, Kulbacka J, Apoptosis as the main type of cell death induced by calcium electroporation in rhabdomyosarcoma cells, Bioelectrochemistry, 136 (2020) 107592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Salucci S, Battistelli M, Burattini S, Squillace C, Canonico B, Gobbi P, Papa S, Falcieri E, C2C12 myoblast sensitivity to different apoptotic chemical triggers, Micron, 41 (2010) 966–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Meerbrey KL, Hu G, Kessler JD, Roarty K, Li MZ, Fang JE, Herschkowitz JI, Burrows AE, Ciccia A, Sun T, Schmitt EM, Bernardi RJ, Fu X, Bland CS, Cooper TA, Schiff R, Rosen JM, Westbrook TF, Elledge SJ, The pINDUCER lentiviral toolkit for inducible RNA interference in vitro and in vivo, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108 (2011) 3665–3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Liu X, Yang JM, Zhang SS, Liu XY, Liu DX, Induction of cell cycle arrest at G1 and S phases and cAMP-dependent differentiation in C6 glioma by low concentration of cycloheximide, BMC Cancer, 10 (2010) 684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Lockhead S, Moskaleva A, Kamenz J, Chen Y, Kang M, Reddy AR, Santos SDM, Ferrell JE Jr., The Apparent Requirement for Protein Synthesis during G2 Phase Is due to Checkpoint Activation, Cell reports, 32 (2020) 107901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Hernandez-Hernandez JM, Mallappa C, Nasipak BT, Oesterreich S, Imbalzano AN, The Scaffold attachment factor b1 (Safb1) regulates myogenic differentiation by facilitating the transition of myogenic gene chromatin from a repressed to an activated state, Nucleic acids research, 41 (2013) 5704–5716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD, Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative pCr and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method, Methods, 25 (2001) 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Bradford MM, A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding, Analytical biochemistry, 72 (1976) 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL, HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements, Nature methods, 12 (2015) 357–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL, StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads, Nature biotechnology, 33 (2015) 290–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L, Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation, Nature biotechnology, 28 (2010) 511–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Langmead B, Salzberg SL, Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2, Nature methods, 9 (2012) 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Li B, Dewey CN, RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome, BMC bioinformatics, 12 (2011) 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Love MI, Huber W, Anders S, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2, Genome biology, 15 (2014) 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Audic S, Claverie JM, The significance of digital gene expression profiles, Genome research, 7 (1997) 986–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Suzuki K, Bose P, Leong-Quong RY, Fujita DJ, Riabowol K, REAP: A two minute cell fractionation method, BMC Res Notes, 3 (2010) 294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Ohkawa Y, Mallappa C, Vallaster CS, Imbalzano AN, An improved restriction enzyme accessibility assay for analyzing changes in chromatin structure in samples of limited cell number, Methods Mol Biol, 798 (2012) 531–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Zammit PS, Relaix F, Nagata Y, Ruiz AP, Collins CA, Partridge TA, Beauchamp JR, Pax7 and myogenic progression in skeletal muscle satellite cells, Journal of cell science, 119 (2006) 1824–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Oustanina S, Hause G, Braun T, Pax7 directs postnatal renewal and propagation of myogenic satellite cells but not their specification, EMBO J, 23 (2004) 3430–3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Seale P, Sabourin LA, Girgis-Gabardo A, Mansouri A, Gruss P, Rudnicki MA, Pax7 is required for the specification of myogenic satellite cells, Cell, 102 (2000) 777–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Wu JI, Lessard J, Crabtree GR, Understanding the words of chromatin regulation, Cell, 136 (2009) 200–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Buckingham M, Bajard L, Daubas P, Esner M, Lagha M, Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Myogenic progenitor cells in the mouse embryo are marked by the expression of Pax3/7 genes that regulate their survival and myogenic potential, Anatomy and embryology, 211 Suppl 1 (2006) 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Betz BL, Strobeck MW, Reisman DN, Knudsen ES, Weissman BE, Re-expression of hSNF5/INI1/BAF47 in pediatric tumor cells leads to G1 arrest associated with induction of p16ink4a and activation of RB, Oncogene, 21 (2002) 5193–5203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Oruetxebarria I, Venturini F, Kekarainen T, Houweling A, Zuijderduijn LM, Mohd-Sarip A, Vries RG, Hoeben RC, Verrijzer CP, P16INK4a is required for hSNF5 chromatin remodeler-induced cellular senescence in malignant rhabdoid tumor cells, J Biol Chem, 279 (2004) 3807–3816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].He L, Chen Y, Feng J, Sun W, Li S, Ou M, Tang L, Cellular senescence regulated by SWI/SNF complex subunits through p53/p21 and p16/pRB pathway, The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology, 90 (2017) 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Nagl NG Jr., Zweitzig DR, Thimmapaya B, Beck GR Jr., Moran E, The c-myc gene is a direct target of mammalian SWI/SNF-related complexes during differentiation-associated cell cycle arrest, Cancer Res, 66 (2006) 1289–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Muchardt C, Yaniv M, When the SWI/SNF complex remodels…the cell cycle, Oncogene, 20 (2001) 3067–3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Baeyens N, de Meester C, Yerna X, Morel N, EBP50 is involved in the regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell migration and cytokinesis, J Cell Biochem, 112 (2011) 2574–2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Song GJ, Barrick S, Leslie KL, Bauer PM, Alonso V, Friedman PA, Fiaschi-Taesch NM, Bisello A, The scaffolding protein EBP50 promotes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointima formation by regulating Skp2 and p21(cip1), Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 32 (2012) 33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Nieuwenhuis J, Brummelkamp TR, The Tubulin Detyrosination Cycle: Function and Enzymes, Trends Cell Biol, 29 (2019) 80–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Stolearenco V, Levring TB, Nielsen HM, Lindahl L, Fredholm S, Kongsbak-Wismann M, Willerslev-Olsen A, Buus TB, Nastasi C, Hu T, Gluud M, Come CRM, Krejsgaard T, Iversen L, Bonefeld CM, Gronbaek K, Met O, Woetmann A, Odum N, Geisler C, The Thioredoxin-Interacting Protein TXNIP Is a Putative Tumour Suppressor in Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma, Dermatology, 237 (2021) 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Sarkar S, Poon CC, Mirzaei R, Rawji KS, Hader W, Bose P, Kelly J, Dunn JF, Yong VW, Microglia induces Gas1 expression in human brain tumor-initiating cells to reduce tumorigenecity, Sci Rep, 8 (2018) 15286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Li Q, Qin Y, Wei P, Lian P, Li Y, Xu Y, Li X, Li D, Cai S, Gas1 Inhibits Metastatic and Metabolic Phenotypes in Colorectal Carcinoma, Mol Cancer Res, 14 (2016) 830–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Uringa EJ, Youds JL, Lisaingo K, Lansdorp PM, Boulton SJ, RTEL1: an essential helicase for telomere maintenance and the regulation of homologous recombination, Nucleic acids research, 39 (2011) 1647–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Park YK, Lee JE, Yan Z, McKernan K, O’Haren T, Wang W, Peng W, Ge K, Interplay of BAF and MLL4 promotes cell type-specific enhancer activation, Nat Commun, 12 (2021) 1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Liu R, Liu H, Chen X, Kirby M, Brown PO, Zhao K, Regulation of CSF1 promoter by the SWI/SNF-like BAF complex, Cell, 106 (2001) 309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Wanior M, Kramer A, Knapp S, Joerger AC, Exploiting vulnerabilities of SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complexes for cancer therapy, Oncogene, 40 (2021) 3637–3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Xu R, Spencer VA, Bissell MJ, Extracellular matrix-regulated gene expression requires cooperation of SWI/SNF and transcription factors, J Biol Chem, 282 (2007) 14992–14999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Saladi SV, Keenen B, Marathe HG, Qi H, Chin KV, de la Serna IL, Modulation of extracellular matrix/adhesion molecule expression by BRG1 is associated with increased melanoma invasiveness, Mol Cancer, 9 (2010) 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Barutcu AR, Lajoie BR, Fritz AJ, McCord RP, Nickerson JA, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Stein JL, Dekker J, Stein GS, Imbalzano AN, SMARCA4 regulates gene expression and higher-order chromatin structure in proliferating mammary epithelial cells, Genome research, 26 (2016) 1188–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Carmel-Gross I, Levy E, Armon L, Yaron O, Waldman Ben-Asher H, Urbach A, Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Fate Regulation by SMARCB1, Stem Cell Reports, 15 (2020) 1037–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Sokol ES, Feng YX, Jin DX, Tizabi MD, Miller DH, Cohen MA, Sanduja S, Reinhardt F, Pandey J, Superville DA, Jaenisch R, Gupta PB, SMARCE1 is required for the invasive progression of in situ cancers, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 114 (2017) 4153–4158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Yan H, Xu F, Xu J, Song MA, Wang K, Wang L, Activation of Akt-dependent Nrf2/ARE pathway by restoration of Brg-1 remits high glucose-induced oxidative stress and ECM accumulation in podocytes, J Biochem Mol Toxicol, 35 (2021) e22672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Farrants AK, Chromatin remodelling and actin organisation, FEBS letters, 582 (2008) 2041–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq datasets are available at GEO. The accession number is: GSE182421 (Reviewer token: ifkpasemtdqfvkd). Source data underlying figures are presented in Supplementary Tables 4–6. All other data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.