Abstract

(−)-β-d-1′,3′-Dioxolane guanosine (DXG) and 2,6-diaminopurine (DAPD) dioxolanyl nucleoside analogues have been reported to be potent inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). We have recently conducted experiments to more fully characterize their in vitro anti-HIV-1 profiles. Antiviral assays performed in cell culture systems determined that DXG had 50% effective concentrations of 0.046 and 0.085 μM when evaluated against HIV-1IIIB in cord blood mononuclear cells and MT-2 cells, respectively. These values indicate that DXG is approximately equipotent to 2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine (3TC) but 5- to 10-fold less potent than 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT) in the two cell systems tested. At the same time, DAPD was approximately 5- to 20-fold less active than DXG in the anti-HIV-1 assays. When recombinant or clinical variants of HIV-1 were used to assess the efficacy of the purine nucleoside analogues against drug-resistant HIV-1, it was observed that AZT-resistant virus remained sensitive to DXG and DAPD. Virus harboring a mutation(s) which conferred decreased sensitivity to 3TC, 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine, and 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine, such as a 65R, 74V, or 184V mutation in the viral reverse transcriptase (RT), exhibited a two- to fivefold-decreased susceptibility to DXG or DAPD. When nonnucleoside RT inhibitor-resistant and protease inhibitor-resistant viruses were tested, no change in virus sensitivity to DXG or DAPD was observed. In vitro drug combination assays indicated that DXG had synergistic antiviral effects when used in combination with AZT, 3TC, or nevirapine. In cellular toxicity analyses, DXG and DAPD had 50% cytotoxic concentrations of greater than 500 μM when tested in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and a variety of human tumor and normal cell lines. The triphosphate form of DXG competed with the natural nucleotide substrates and acted as a chain terminator of the nascent DNA. These data suggest that DXG triphosphate may be the active intracellular metabolite, consistent with the mechanism by which other nucleoside analogues inhibit HIV-1 replication. Our results suggest that the use of DXG and DAPD as therapeutic agents for HIV-1 infection should be explored.

Reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors play a cornerstone role in the therapy for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Based on structure and mechanism of action, these inhibitors can be classified into two major groups, nucleoside RT inhibitors (NRTIs) and nonnucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs). NRTIs are usually 2′,3′-dideoxy derivatives of natural substrates of DNA polymerases. All NRTIs are believed to act in a similar fashion to inhibit the RT activity (9, 15, 20, 34, 39); i.e., following intracellular conversion to their 5′-triphosphate derivatives, they bind to RT in competition with natural substrates and subsequently cause chain termination through incorporation into the nascent DNA strand. Chain termination is caused by the lack of a 3′-hydroxyl motif, which is needed to form a 3′-5′ phosphodiester bond with the next nucleoside substrate in the elongating DNA strand. NNRTIs are a group of compounds which specifically inhibit HIV-1 RT by binding to a hydrophobic pocket close to the polymerase active site, which results in a direct inactivation of RT (8, 14, 18, 26, 33, 38).

Currently, the appearance of drug-resistant virus is an inevitable consequence of prolonged exposure of HIV-1 to antiretroviral agents. This is believed to be caused by both a high turnover of HIV-1 in patients (16, 37) and low fidelity of the viral RT (7). To achieve efficient inhibition of HIV-1 replication in patients, and to delay or prevent the appearance of drug-resistant virus, drug combinations have been used effectively in treating HIV-1 infection (2, 22). However, recent studies have suggested that HIV-1 can become multidrug resistant under combination therapy, albeit requiring a longer time to develop than in a single-drug regime (4, 31). Therefore, it is still necessary to develop alternate drug combinations for the long-term successful treatment of HIV-1 infection. We are focusing our efforts on developing new agents which are effective against existing drug-resistant virus and can be rationally incorporated into combination drug therapy.

In this regard, several groups have recently reported the synthesis of pyrimidine- and purine-derived nucleoside analogues containing a dioxolane sugar derivative, in which an oxygen atom is found at the 3′ position of the sugar ring (3, 6, 21). The β-d analogues of purine bases have been reported to be potent anti-HIV-1 agents (17, 32). In particular, (−)-β-d-1′,3′-dioxolane guanosine (DXG) and (−)-β-d-2,6-diaminopurine dioxolane (DAPD) have been reported to inhibit HIV-1 in vitro (17, 32). Following oral administration of DAPD to woodchucks or rhesus monkeys, plasma concentrations of DXG are significantly higher than those of DAPD (23, 24). These data suggest that DAPD is quickly converted into DXG in vivo and should be considered a prodrug of DXG. None of the currently approved anti-HIV-1 nucleoside analogues contains a dioxolane sugar motif. Therefore, DXG and its putative prodrug analogue represent a novel class of nucleosides with potential utility in anti-HIV-1 therapy. The present report describes our results in further elucidating the mechanism of action of DXG and DAPD. In addition, we have examined the effect of these compounds on wild-type (wt) and drug-resistant clinical isolates of HIV-1, alone and in combination with other NRTIs or NNRTIs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

DXG, DAPD, DXG 5′-triphosphate (DXG-TP), (+)-β-d-1′,3′-dioxolane guanosine, and 2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine (3TC) were synthesized at BioChem Pharma as previously described (3, 32). All of the dioxolanyl nucleosides were enantiomerically pure. 3′-Azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT) and 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine (ddC) were purchased from Sigma (Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Ultrapure nucleoside 5′-triphosphates, 2′-deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphates (dNTPs), 2′,3′-dideoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphates (ddNTPs), and polynucleotides poly(rA) · oligo(dT)12–18 and poly(rC) · oligo(dG)12–18 were purchased from Pharmacia Biotech Inc. (Montreal, Quebec, Canada). AZT triphosphate (AZT-TP) and 3TC triphosphate (3TC-TP) were purchased from Moravek Biochemicals. [3H]dGTP, [3H]TTP, and [γ-32P]ATP were obtained from Du Pont NEN (Montreal, Quebec, Canada). [3H]thymidine was obtained from Amersham (Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Nevirapine was generously provided by Boehringer-Ingelheim Inc. (Burlington, Ontario, Canada).

Cells and viruses.

Human cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from HIV-1-negative and hepatitis B virus-negative donors (Department of Obstetrics, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) and isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia) density gradient centrifugation. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL Laboratories, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) containing 0.1% (vol/vol) (5 μg/ml) phytohemagglutinin (Boehringer Mannheim, Montreal, Quebec, Canada), 10% fetal calf serum (Flow Laboratories, Toronto, Ontario, Canada), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 15 U of interleukin 2 (Boehringer Mannheim) per ml. Cells were incubated at 37°C, in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, for 3 to 4 days prior to being used for antiviral assays (27).

The T-cell lines MT-2, MT-4, H9, and Jurkat were obtained from either the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagents (Rockville, Md.) or the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). These cells were used for antiviral and cytotoxicity studies and were maintained as suspension cultures in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Other tumor cell lines, Molt-4, HT-1080, DU145, and HepG2, were also obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. One normal cell line, human skin fibroblasts (HSF), was obtained from M. Chevrette (McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). These cells were used for cytotoxicity assays. HSF, HT-1080, DU145, and HepG-2 cells were cultured in minimal essential medium. Molt-4 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium.

HIV-1IIIB and the recombinant HIV-1 clone HXB2-D were kindly supplied by R. C. Gallo (Institute of Human Virology, Baltimore, Md.). Recombinant mutated HIV-1 variants were prepared by site-directed mutagenesis as previously described (10, 12). HIV-1 clinical isolates were obtained by coculture of peripheral blood lymphocytes from HIV-1-infected individuals with CBMCs and then propagated on CBMCs in the absence of drugs as previously described (28).

Antiviral assays.

The anti-HIV-1 activities of DXG and DAPD were assessed by employing HIV-1IIIB in a variety of cell types as previously described (10, 12, 25, 28). A number of recombinant drug-resistant variants and low-passage clinical isolates from individuals who had received long-term anti-HIV therapy were also used to evaluate the effects of these two compounds. Briefly, cells were incubated for 2 to 3 h with virus at a multiplicity of infection of 0.005 for T-cell assays or 0.5 for monocytic-cell assays. The infected cells were cultured in the presence of the test compound for 5 to 7 days. The anti-HIV-1 efficacy was determined by testing for HIV-1 RT activity in the cell culture supernatants. All assays were performed in duplicate, and at least two independent experiments were performed. AZT and/or 3TC was used as a control in each experiment. The data are expressed as the means of the 50% effective concentrations (EC50s) as calculated from the linear portion of the dose-response curve.

Effects of combining DXG and standard anti-HIV-1 agents were assessed in CBMCs by using HIV-1IIIB. The combinations were performed by using a checker board cross pattern of drug concentrations. The antiviral effects were determined by monitoring RT activity in the culture supernatants at day 7. The data were analyzed according to the method described by Chou and Talalay (5). The combination indices (CIs) of DXG with other anti-HIV-1 agents were calculated by using CalcuSyn software (Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Theoretically, a CI value of 1 indicates an additive effect, a CI value of >1 indicates antagonism, and a CI value of <1 indicates synergism.

Cytotoxicity analysis.

Cellular toxicity was assessed by [3H]thymidine uptake and WST-1 staining. In the [3H]thymidine uptake experiments, Molt-4, HT1080, DU-145, HepG2, and HSF were plated at a concentration of 1 × 103 to 2 × 103 cells per well (96-well plates). Phytohemagglutinin-stimulated PBMCs were cultured at a concentration of 4 × 104 per well. Following a 24-h preincubation period, test compounds (at 10−4 to 10−10 M concentrations) were added and the cells were incubated for an additional 72 h. [3H]thymidine was added during the final 18-h incubation period. The cells were then washed once with phosphate-buffered saline, treated with trypsin if the cells were adherent, and resuspended in water (hypotonic lysing of cells). The cellular extract was applied directly to a Tomtec Harvester 96 apparatus. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) was determined by comparing the radioactive counts per minute obtained from drug-tested samples to those obtained from the control (untreated) cells.

In the WST-1 staining experiments, cell lines were cultured in RPMI medium in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well. CBMCs were plated at a concentration of 0.5 × 106/well. Compounds (at 10−4 to 10−7 M concentrations) were added at day zero. Cell viability was assessed on day 7 by using the WST-1 reagent (Boehringer Mannheim) in accordance with the protocol provided by the supplier.

RT inhibition assay.

wt recombinant HIV-1 RT was expressed as a histidine-tagged protein in Escherichia coli and purified to 95% homogeneity as previously described (11, 13). Inhibition of HIV-1 RT RNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity by DXG-TP was assessed by employing both homopolymeric and heteropolymeric RNA templates/DNA primers (T/P). The heteropolymeric RNA template (HIV-PBS)/18-mer oligodeoxynucleotide primer (dPR) was prepared as described previously (11). The reverse transcription reaction mixture contained final concentrations of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 60 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 U of homopolymeric T/P per ml, 5 μM dNTP substrate or 25 nM HIV-PBS/dPR, and 5 μM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP in 100 μl. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the presence or absence of ddNTP inhibitors as described previously (11).

The effect of DXG-TP on RT activity was also assessed by using a chain termination/dNTP incorporation assay in which inhibition of nascent DNA synthesis (chain termination) was monitored based on cDNA synthesis as previously described (1, 13).

Determination of HIV-1 RT genotype.

To determine the RT genotypes of the HIV-1 clinical isolates, proviral DNA of each isolate was extracted from infected CD4+ T cells or CBMCs and the complete RT coding regions were amplified by PCR as previously reported (10). The PCR product was purified and then directly sequenced by using primer RTS (5′-CCAAAAGTTAAACAATGGC-3′), which corresponds to the 5′ portion of the RT coding region (nucleotides 2603 to 2621 of HXB2-D coordinates).

RESULTS

Inhibition of HIV-1 RT polymerase activity by DXG-TP.

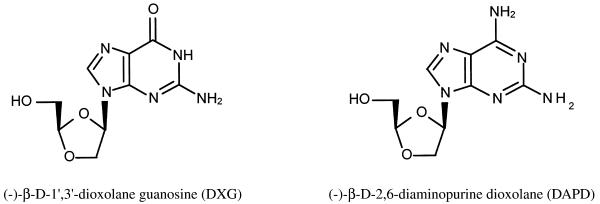

The chemical structures of 1′,3′-dioxolanylpurine nucleosides DXG and DAPD are shown in Fig. 1. DXG-TP is the active antiviral form of DAPD in vivo (23, 24). To better define the molecular mechanism by which these nucleoside analogues inhibit HIV-1, DXG was chemically converted to its triphosphate derivative (DXG-TP) and tested for its direct effect on HIV-1 RT. The inhibitory effect of DXG-TP on HIV-1 RT activity was assessed by using various homopolymeric and heteropolymeric T/P (Table 1). DXG-TP was a potent HIV-1 RT inhibitor, with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.012 μM, when using wt HIV-1 RT, complementary T/P poly(rC) · oligo(dG), and substrate dGTP (Table 1). This value is similar to that obtained for ddGTP. Similarly, DXG-TP and ddGTP were observed to have the same inhibitory effect on HIV-1 RT when the heteropolymeric T/P (HIV-PBS/dPR) was used (Table 1). The inhibition of HIV-1 RT by DXG-TP was observed to occur via competition with the natural substrate; i.e., the higher the concentration of dGTP, the lower the inhibitory effect of DXG-TP (data not shown). In addition, as expected, DXG-TP did not show any inhibition of HIV-1 RT activity at concentrations up to 10 μM when the noncomplementary T/P poly(rA) · oligo(dT) was used along with dTTP as the substrate (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Molecular structures of dioxolanylpurines.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of HIV-1 RT by DXG-TP and other ddNTPs

| Template · primer | Substrate | IC50 (μM) of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DXG-TP | ddGTP | ddTTP | ||

| poly(rC) · oligo(dG)12–18 | dGTP | 0.012 ± 0.002 | 0.011 ± 0.0007 | NDa |

| poly(rA) · oligo(dT)12–18 | dTTP | >10b | ND | 0.024 ± 0.003 |

| HIV-PBS/dPR | dNTPsc | 0.062 ± 0.007 | 0.074 ± 0.008 | ND |

ND, not determined.

The highest concentration of inhibitor used in the inhibition study was 10 μM.

Each dNTP (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP) was at 5 μM.

We also analyzed the effect of DXG-TP on HIV-1 RT activity by a chain elongation/termination assay which provides a method to directly visualize the incorporation of dideoxynucleotide monophosphates into nascent DNA by monitoring the reaction products through polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. It was showed that DXG monophosphate was incorporated into the nascent DNA strands and resulted in chain termination (results not shown). The pattern of chain termination generated by incorporation of DXG-TP into elongating DNA strands was exactly the same as that for ddGMP. In general, the inhibitory effect of DXG-TP on RT activity in this cell-free assay was approximately equivalent to those observed for ddGTP and AZT-TP but stronger than the chain termination observed for 3TC-TP (results not shown).

Cellular toxicity.

DXG and DAPD, along with 3TC and AZT, were also tested for their effect on cell proliferation by measuring [3H]thymidine uptake and cell toxicity by WST-1 cell viability assays. DXG and DAPD did not inhibit cell proliferation at concentrations up to 500 μM in various cells (Table 2). In the same experiments, CC50s for AZT and ddC were found to be less than 10 μM. DXG was not toxic to human CBMCs (Table 2), MT-2, H9, or Jurkat cell lines (data not shown) at concentrations up to 100 μM by a WST-1 cell viability assay. In contrast, the CC50s obtained for AZT and ddC in CBMCs were 74 and 29 μM, respectively (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effect of nucleoside analogues on cell proliferation

| Cells | [3H]thymidine uptake [CC50 (μM)]ac

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DXG | DAPD | 3TC | AZT | ddC | |

| PBMC | >500 | >500 | >500 | 9 | 35.5 |

| Molt-4 | >500 | >500 | NDb | 3 | 2 |

| HT-1080 | >500 | >500 | >500 | 5 | 2 |

| HepG2 | >500 | ≥500 | 350 | 3 | 7 |

| DU145 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >10 | 5 |

| HSF | ≥500 | >500 | 400 | >10 | 2 |

| CBMCc | >100 | >100 | ND | 74 | 29 |

The highest concentrations of DXG and DAPD used in these studies were 500 μM in [3H]thymidine uptake and 100 μM in WST-1 staining.

ND, not determined.

CC50s for CBMC were obtained by WST-1 staining.

Anti-HIV-1 efficacy in different cell types.

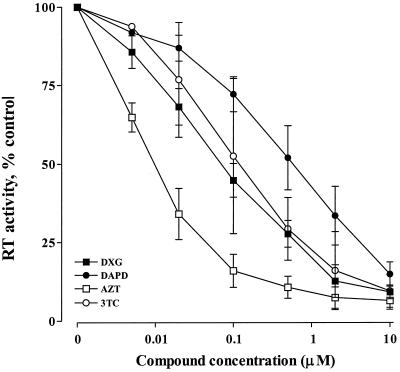

The anabolism of nucleoside analogues can be greatly influenced by cell type. Therefore, we assessed the anti-HIV-1 activity of DXG and DAPD in human CBMCs and a variety of human T-cell lines. A dose-response curve showing the inhibition of HIV-1IIIB in MT-2 cells is presented in Fig. 2. The results indicate that the activity of DXG is approximately equivalent to that of 3TC but is 5- to 10-fold lower than that of AZT. DAPD was approximately 10-fold less active than DXG. The EC50s obtained for the test compounds in primary cells and cell lines are compiled in Table 3.

FIG. 2.

Dose-response curve of inhibition of HIV-1 replication. MT-2 cells were infected with HIV-1IIIB at a multiplicity of infection of 0.005. The infected cells were cultured in the presence of various concentrations of antiviral compounds as indicated. Viral susceptibility to the compounds was assayed by measurement of HIV-1 RT activity in the culture supernatants as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations of data from at least five separate experiments, each performed in duplicate.

TABLE 3.

Inhibitory effects of nucleoside analogues on HIV-1 replicationa

| Cells | EC50 (μM)b of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DXG | DAPD | 3TC | AZT | |

| CBMC | 0.046 ± 0.017 | 0.97 ± 0.092 | 0.023 ± 0.011 | 0.0051 ± 0.003 |

| MT-2 | 0.085 ± 0.026 | 0.54 ± 0.29 | 0.091 ± 0.08 | 0.0076 ± 0.0044 |

| MT-4 | 0.051 | 0.94 | 0.056 | 0.008 |

| Jurkat | 0.34 | 1.37 | 0.53 | 0.011 |

| H9 | 0.06 | 0.075 | NDc | 0.041 |

All assays were performed with laboratory strain HIV-1IIIB.

The values presented are the means ± standard deviations of data from at least three experiments performed in duplicate. Values without standard deviations are the averages of data from two independent experiments conducted in duplicate.

ND, not determined.

We also compared the antiviral activities of DXG and (+)-β-d-1′,3′-dioxolane guanosine. Our results show that the (+) enantiomer (EC50, 0.7 μM) has less activity against HIV-1IIIB in MT-2 cells than the (−) enantiomer (EC50, 0.085 μM).

Susceptibility of recombinant drug-resistant HIV-1 variants.

Recombinant HIV-1 variants carrying a drug resistance mutation(s) were employed to test the cross-resistance phenotypes of DXG and DAPD in CBMCs and MT-2 cells. All of the recombinant viral strains were derived from HXB2-D. A summary of the genetic backgrounds of the variants and their sensitivities to the dioxolanylpurine compounds, 3TC and AZT, in CBMCs is shown in Table 4. These viruses contain mutations seen for the most common RT inhibitor- and protease inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 variants (summarized in reference 29). The variants of HIV-1 carrying 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine (ddI), ddC, or 3TC resistance mutations (i.e., 65K, 74V, and 184V substitutions, respectively) in the RT gene had minimally (two- to fivefold) decreased sensitivity to DXG and DAPD compared to the wt HXB2-D in CBMCs (Table 4). Similar results were obtained when the recombinant viruses were tested in MT-2 cells (data not shown). In addition, the variant bearing mutations 41L, 215Y, and 184V had approximately a twofold-decreased sensitivity to DXG, which was similar to that of the 184V single-mutant recombinant. This variant had high-level resistance to 3TC but increased sensitivity to AZT (36).

TABLE 4.

Effect of DXG and DAPD on recombinant drug-resistant strains of HIV-1

| Recombinant varianta | Resistant to: | EC50 (μM) in CBMCsb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DXG | DAPD | 3TC | AZT | ||

| HXB2-D (wt) | 0.21 | 1.1 | 0.041 | 0.0041 | |

| 65R | ddI, ddC, 3TC, PMEAg | 1.2 | 6.5 | 0.36 | 0.003 |

| 74V | ddI | 1.3 | 6.6 | 0.12 | 0.006 |

| 184V | 3TC, ddI, ddC | 0.44 | 2.1 | >50c | 0.0027 |

| 41L 70R 215Y 219Q | AZT | 0.24 | 1.25 | 0.062 | 0.082 |

| 41L 215Y 184V | 3TC | 0.41 | 2.3 | >50c | 0.006 |

| 106A 181Cd | NNRTIs | 0.05 | NDe | ND | 0.03 |

| 10R 46I 63P 82T 84Vf | Protease inhibitors | 0.12 | 1.37 | ND | 0.0032 |

The recombinant viruses were wt and mutants harboring the indicated substitution(s) in the RT.

Values are the averages of data from two independent experiments performed in duplicate.

The highest concentration of 3TC used in these assays was 50 μM.

The EC50 for nevirapine was >10 μM.

ND, not determined.

Protease genotype; the EC50 for saquinavir was 0.075 μM.

PMEA, 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine.

In contrast, AZT-resistant virus, carrying multiple substitutions (41L, 70R, 215Y, and 219Q) in its RT gene, remained completely sensitive to DXG and DAPD in CBMCs (Table 4) and MT-2 cells (data not shown). In addition, the dioxolanyl nucleoside analogues were effective against NNRTI-resistant (EC50 = 0.05 μM) and protease inhibitor-resistant (EC50 = 0.12 to 1.37 μM) variants (Table 4).

Susceptibility of HIV-1 clinical isolates.

The sensitivity of viruses found in clinical isolates to antiviral chemotherapy might be quite variable due to the presence of quasispecies. In addition, HIV-1 isolates obtained from patients receiving long-term antiretroviral therapy might behave differently from cloned viruses containing genetically engineered mutations in the RT gene. For these reasons, clinical isolates of HIV-1 from antiviral-agent-naive and drug-treated patients were assayed in CBMCs for their sensitivity to DXG and DAPD. A summary of the recent therapy histories of the patients from which the HIV-1 isolates were obtained, the RT genotypes of the isolates, and their sensitivities to the various anti-HIV agents is presented in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Susceptibility of HIV-1 isolates from patients treated with nucleoside analogues to DXG and DAPD

| Viral isolate | Antiviral therapy (wk) | RT genotype | EC50 (μM) in CBMCsa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DXG | DAPD | 3TC | AZT | |||

| 3887 | 3TC (24) | 184M/V | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.0007 |

| 4246 | AZT (104) | wt | 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.023 | 0.023 |

| 4526b | None | NDc | 0.055 | 0.85 | ND | 0.0043 |

| 4877d | None | 41L | 0.045 | 0.26 | ND | 0.015 |

| 3350 | 3TC (12) | 184V | 0.65 | 3.3 | >100 | 0.014 |

| 4205 | 3TC (52) | 184V | 1.1 | 4.1 | >100 | 0.022 |

| 4242 | AZT | 41L 70R 215Y | 0.21 | 0.88 | 0.009 | 0.15 |

| 4833b | Saquinavir (48) | ND | 0.17 | 0.63 | ND | 0.062 |

| 4924d | AZT and nevirapine (26) | 41L 103N | 0.02 | 0.17 | ND | 0.001 |

Values are the averages of data from two independent experiments conducted in duplicate.

Neither RT nor protease genotypes were not determined. EC50s for saquinavir were 0.0063 μM against isolate 4526 (baseline isolate) and 0.11 μM against isolate 4833.

ND, not determined.

EC50s were obtained from a single experiment in duplicate. EC50s for nevirapine were 0.065 μM against isolate 4877 (baseline isolate) and >10 μM against isolate 4924.

Four isolates (no. 3887, 4246, 4877, and 4526) were sensitive to AZT and/or 3TC or had marginally decreased sensitivity to one of these two drugs compared with recombinant variants (Table 4). Using these four isolates, the EC50s obtained for both DXG and DAPD (Table 5) were comparable to those observed with the wt strains HIV-1IIIB and HXB2-D assessed in CBMCs (Tables 3 and 4).

Isolates 3350 and 4205, obtained from patients who had received 3TC therapy and carried the 184V mutation, were 3TC resistant and AZT sensitive. These 184V mutant isolates had an approximately fivefold-decreased susceptibility to DXG compared to the 3TC- and AZT-sensitive isolates (Table 5). This was consistent with the results obtained with the recombinant variants (Table 4).

Clinical isolate 4242, obtained from a patient treated with AZT, exhibited decreased sensitivity to AZT but remained sensitive to DXG, DAPD, and 3TC. The NNRTI-resistant strain 4924, isolated from an individual undergoing AZT therapy, had an EC50 for nevirapine of >10 μM but was sensitive to the dioxolane nucleoside analogues (Table 5). The protease inhibitor-resistant isolate 4833 was obtained from an individual who had received 48 weeks of saquinavir therapy. This isolate exhibited a 20-fold-decreased sensitivity (EC50 = 0.11 μM) to the protease inhibitor compared with the baseline isolate, 4526 (EC50 = 0.0063 μM). The 4833 isolate remained sensitive to the dioxolanyl compounds (EC50 = 0.17 μM for DXG and 0.63 μM for DAPD) (Table 5).

Anti-HIV drug combination effects.

The antiviral efficacy of DXG against HIV-1IIIB was assessed in combination with AZT, 3TC, or nevirapine in CBMCs. The CIs of DXG in combination with the approved anti-HIV-1 agents are summarized in Table 6. The CIs were calculated at several different effective concentrations (EC50, EC75, and EC90) and in different molar ratios of the combined drugs. The CIs obtained were between 0.4 and 0.9 in the case of DXG combined with either 3TC or nevirapine, which suggests that DXG had moderate synergy with these two agents. However, DXG demonstrated greater synergy with the thymidine analogue AZT, with CIs between 0.3 to 0.8 at the EC50 and less than 0.3 at higher effective concentrations, which indicates a strong synergy.

TABLE 6.

Effects of combination of DXG with antiretroviral agents

| Drug combination and molar ratio | CIa in CBMCs at inhibition level of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 | EC75 | EC90 | |

| DXG and AZT | |||

| 10:1 | 0.61 | 0.27 | 0.12 |

| 20:1 | 0.57 | 0.29 | 0.15 |

| 40:1 | 0.67 | 0.30 | 0.14 |

| DXG and 3TC | |||

| 1:1.6 | 0.79 | 0.59 | 0.47 |

| 1.25:1 | 0.82 | 0.58 | 0.46 |

| 2.5:1 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 0.42 |

| DXG and nevirapine | |||

| 1.25:1 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.52 |

| 2.5:1 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 0.52 |

| 5:1 | 0.87 | 0.54 | 0.38 |

CIs were analyzed by the method described by Chou and Talalay (5) and calculated by using CalcuSyn software (Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom). CI values of 1, <1, and >1 indicate additive, synergistic, and antagonistic effects, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The dioxolanyl guanosine analogues DXG and DAPD were previously reported to possess anti-HIV and anti-hepatitis B virus activities (17, 30, 32). In this article, we present an expanded and detailed evaluation of antiviral and biochemical characteristics of DXG and DAPD.

In vitro antiviral assays demonstrated that both DXG and DAPD had very promising anti-HIV-1 activity in the various types of cells tested. Comparison of the (−) and (+) enantiomers of β-1′,3′-dioxolane guanosine showed that both were effective inhibitors of HIV-1, but the (−) enantiomer, DXG, displayed approximately 10-fold higher activity. Generally, the anti-HIV-1 activity of DXG was at the same level as that observed for 3TC in our assays but was 5- to 10-fold less than that of AZT. In vivo, DAPD is quickly and efficiently converted into DXG after either oral or intravenous administration to woodchucks or rhesus monkeys (23, 24). This biotransformation is believed to be a deamination process catalyzed by a ubiquitous enzyme, adenosine deaminase. In our experiments, DAPD had consistently lower anti-HIV activity than DXG. These results were consistent with previous reports for the antiretroviral effects of these two dioxolanylpurine nucleoside analogues (17, 32). The relatively low anti-HIV-1 activity of the putative prodrug, DAPD, in cell culture may reflect less-efficient metabolic conversion into the active form, DXG. This does not necessarily indicate that this compound has less anti-HIV-1 activity in vivo. From a pharmaceutical point of view, DAPD might be equipotent to DXG in vivo. The ultimate choice of compound to advance into human therapy would be dependent on other parameters, such as oral bioavailability (23, 24).

The appearance of drug-resistant virus following prolonged administration of antiviral agents is a major obstacle for the therapy of HIV-1 infection. Therefore, we conducted antiviral assays to elucidate the cross-resistance profiles of the novel dioxolanylpurine analogues. Using recombinant and clinical drug-resistant HIV-1 variants carrying the most common RT inhibitor resistance-related mutations, it was demonstrated that DXG and DAPD possess marginal cross-resistance with 3TC (Tables 4 and 5). Our results show that HIV-1 strains carrying 65R and 74V substitutions in their RT genes had approximately fivefold-reduced sensitivity to the dioxolane compounds, which is consistent with previously reported values (19). However, both DXG and the DAPD retained their potency to AZT-resistant, NNRTI-resistant, and protease inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 variants. These data suggest that DXG or DAPD could be used as an alternative drug for the treatment of HIV-1-infected individuals who have developed tolerance to currently approved drug regimens.

Combination therapy has proven to be an exciting approach to combat HIV-1 infection. Combination therapy increases the therapeutic efficiency of anti-HIV agents and delays or prevents selection of drug-resistant virus. Combination profiles with approved anti-HIV-1 agents have become an essential prerequisite for new drug candidates. DXG showed synergy with the NRTIs AZT and 3TC and the NNRTI nevirapine (Table 6). These data suggest that the combination of DXG with approved anti-HIV agents in the treatment of HIV-1 infection could have increased clinical benefits. Previous reports have demonstrated that the mutations 65R, 74V, and 184V in HIV-1 RT, which confer minimal cross-resistance to DXG and DAPD, can revert AZT-resistant virus to AZT sensitivity (19, 35, 36). The strong in vitro synergy of DXG and AZT, combined with the increased sensitivity of the AZT drug resistance phenotype, indicates a potential benefit for a DXG and AZT combination.

The guanosine analogue dideoxyguanosine displays excellent anti-HIV activity in vitro. However, it was never developed into an antiretroviral agent because of its high cellular toxicity. DXG and DAPD had relatively low cellular toxicity to human primary cells and a variety of established normal and tumor cell lines. Neither compound showed significant inhibition of cellular DNA synthesis or cell proliferation, and both were found to be much less toxic than AZT or ddC (Table 2).

Our RT enzymatic analysis elucidated that DXG-TP, the putative active intracellular metabolite of DXG and DAPD, is a competitor of the natural substrate deoxyguanosine (Table 1) and a DNA synthesis chain terminator (data not shown). Similar to other nucleoside analogues (9, 11, 13), DXG-TP inhibits HIV-1 in vivo by competitively inhibiting the binding of the natural substrate dGTP to the HIV-1 RT. DXG-TP is incorporated into the nascent DNA strand, resulting in chain termination.

In summary, the dioxolanylpurine analogues DXG and DAPD are distinct from the related nucleoside analogue dideoxyguanosine in that they are selective inhibitors of the viral polymerase and have relatively low cellular toxicity, yielding a large selective index. These novel guanosine analogues have potent antiretroviral activity against both wild-type and drug-resistant HIV-1 variants, as well as synergistic activity when tested in combination with approved anti-HIV-1 agents. Thus, these observations suggest that the heterosubstituted guanosine analogues have potential as anti-HIV-1 drug candidates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maureen Olivera and Stephanie Brunette for excellent technical help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arts E J, Li X, Gu Z, Kleiman L, Parniak M A, Wainberg M A. Comparison of deoxynucleotide and tRNA3lys as primers in an endogenous human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in vitro reverse transcription/template-switching reaction. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14672–14680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Autran B, Li G, Blanc T S, Matthez D, Tubiana R, Katlama C, Debre P, Leibowitch J. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science. 1997;277:112–116. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belleau, B., D. Dixit, N. Nguyen-Ba, and J. Krause. 1989. Design and activity of a novel class of nucleoside analogs effective against HIV-1. Presented at the 5th International Conference on AIDS, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 4 to 9 June 1989.

- 4.Carpenter C C J, Fishl M A, Hammer S M, Hirsch M S, Jacobson D M, Katzenstein D A, Montaner J S G, Richman D D, Saag M S, Schooley R T, Thompson M A, Valla S, Yani P G, Volberding P A. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in 1997. Update recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA. 1997;277:1962–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou T-C, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu C, Ahn S, Kim H, Alves A J, Beach J W, Jeong L S, Islam Q, Schinazi R F. Asymmetric synthesis of enantiomerically pure (−)-(1′R, 4′R-dioxolane-thymidine) and its anti-HIV activity. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:3791–3794. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffin J M. HIV population dynamics in vivo: implications for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science. 1995;267:483–489. doi: 10.1126/science.7824947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding J, Das K, Moereels H, Koymans L, Andries K, Janssen P A L, Hughes S H, Arnold E. Structure of HIV-1 RT/TIBO R 86183 complex reveals similarity in the binding of diverse nonnucleoside inhibitors. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:407–415. doi: 10.1038/nsb0595-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furman P A, Fyfe J A, St. Clair M H, Weinhold K, Rideout J L, Freeman G A, Lehrman S N, Bolognesi D P, Broder S, Mitsuya H, Barry D W. Phosphorylation of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine and selective interaction of the 5′-triphosphate with human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8333–8337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu Z, Gao Q, Parniak M A, Wainberg M A. Novel mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase gene that encodes cross-resistance to 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine and 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine. J Virol. 1992;66:12–19. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7128-7135.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu Z, Flether R S, Arts E J, Wainberg M A, Parniak M A. The K65R mutant reverse transcriptase of HIV-1 cross-resistance to 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine, 2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine, and 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine shows reduced sensitivity to specific dideoxynucleoside triphosphate inhibitors in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28118–28122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu Z, Gao Q, Fang H, Salomon H, Parniak M A, Goldberg E, Cameron J, Wainberg M A. Identification of a mutation at codon 65 in the IKKK motif of reverse transcriptase that encode human immunodeficiency virus resistance to 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine and 2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:275–281. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.2.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu Z, Arts E J, Parniak M A, Wainberg M A. Mutated K65R recombinant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase shows diminished chain termination in the presence of 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine-5′-triphosphate and other drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2760–2764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu Z, Quan Y, Li Z, Wainberg M A. Effects of non-nucleoside inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in cell-free recombinant reverse transcriptase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31046–31051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart G J, Orr D C, Penn C R, Figueiredo H T, Gray N M, Boehme R E, Cameron J M. Effects of (−)-2′-deoxy-3′-thiacytidine (3TC) 5′-triphosphate on human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase and mammalian DNA polymerases alpha, beta, and gamma. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1688–1694. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.8.1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho D, Neumann A U, Perelson A S, Chen W, Leonard J M, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Science. 1995;273:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim H O, Schinazi R F, Nampalli S, Shanmuganathan K, Cannon D L, Alves A J, Jeong L S, Beach J W, Chu C K. 1,3-Dioxolanylpurine nucleosides (2R, 4R) and (2R, 4S) with selective anti-HIV-1 activity in human lymphocytes. J Med Chem. 1993;36:30–37. doi: 10.1021/jm00053a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolstaedt L A, Wang J, Friedman J M, Rice P A, Steitz T A. The structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. In: Skalka A M, Goff S P, editors. Reverse transcriptase. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 223–249. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mellors J W, Bazmi H, Chu C K, Schinazi R F. Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on HIV Drug Resistance, Whistler, Canada, 3 to 6 July 1996. 1996. K65R mutation in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase causes resistance to (−)-β-d-dioxolane-guanosine and reverses AZT resistance, abstr. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitsuya H, Broder S. Inhibition of the in vitro infectivity and cytopathic effect of human T-lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus (HTLV-III/LAV) by 2′,3′-dideoxynucleoside. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1911–1915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norbeck D W, Spanton S, Broder S, Mitsuya H. (±)-Dioxolane-T ((±)-1-[(2β,4)-2-(hydroxymethyl)-4-dioxolanyl]thymine): a new 2′,3′-dideoxynucleoside prototype with in vitro activity against HIV. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:6263–6266. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perelson A S, Essunger P, Cao Y, Vesanen M, Hurley A, Saksela K, Markowitz M, Ho D. Decay characteristics of HIV-1 infected compartments during combination therapy. Nature. 1997;387:188–191. doi: 10.1038/387188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajagopalan P, Boudinot F D, Chu C K, McClure H M, Schinazi R F. Pharmacokinetics of (−)-β-d-2,6-diaminopurine dioxolane and its metabolite guanosine in rhesus monkeys. Pharm Res. 1994;11(Suppl.):381–386. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajagopalan P, Boudinot F D, Chu C K, Tennant B C, Baldwin B H, Schinazi R F. Pharmacokinetics of (−)-β-d-2,6-diaminopurine dioxolane and its metabolite, dioxolane guanosine, in woodchucks (Marmota monax) Antivir Chem Chemother. 1996;7:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rando R, Ojwang J, Elbaggari A, Reyes G R, Tinder R, McGrath M S, Hogan M E. Suppression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity in vivo by oligonucleotide which form intramolecular tetrads. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1754–1760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rittinger K, Divita G, Goody R S. Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase substrate-induced conformational changes and the mechanism of inhibition by nonnucleoside inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8046–8049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.8046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rooke R, Tremblay M, Wainberg M A. AZT (zidovudine) may act postintegrationally to inhibit generation of HIV-1 progeny virus in chronically infected cells. Virology. 1990;176:205–215. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90245-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salomon H, Belmonte A, Nguyen K, Gu Z, Gelfand M, Wainberg M A. Comparison of cord blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cells as targets for viral isolation and drug sensitivity studies involving human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2000–2002. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.2000-2002.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schinazi R F, Larder B A, Mellors J W. Mutations in retroviral genes associated with drug resistance. Int Antivir News. 1997;4:95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schinazi R F, McClure H M, Boudinot F D, Jiang Y, Chu C K. Development of (−)-β-d-2,6-diaminopurine dioxolane as a potential antiviral agent. Antivir Res. 1994;23:81. . (Abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shirasaka T, Kavlick M F, Ueno T, Gao W-Y, Kojima E, Alcaide M L, Chokekijchai S, Roy B M, Arnold E, Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H. Emergence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with resistance to multiple dideoxynucleosides in patients receiving therapy with dideoxynucleosides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2398–2402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddiqui M A, Brown W L, Nguyen-Ba N, Dixit D M, Mansour T S. Antiviral optically pure dioxolane purine nucleoside analogs. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1993;3:1543–1546. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spence J C, Kati W M, Anderson K S, Johnson K A. Mechanism of inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by nonnucleoside inhibitors. Science. 1995;276:988–992. doi: 10.1126/science.7532321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.St. Clair M H, Richards C A, Spector T, Weinhold K J, Miller W H, Langlois A J, Furman P A. 3′-Azido-3′-deoxythymidine triphosphate as an inhibitor and substrate of purified human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1972–1977. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.12.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.St. Clair M H, Martin J L, Tudor-Williams G, Bach M C, Vavro C L, King D M, Kellam P, Kemp S D, Laeder B A. Resistance to ddI and sensitivity to AZT induced by a mutation in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science. 1991;153:1557–1559. doi: 10.1126/science.1716788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tisdale M, Kemp S D, Parry N R, Larder B A. Rapid in vitro selection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to 3′-thiacytidine inhibitors due to a mutation in the YMDD region of reverse transcriptase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5653–5656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei X, Ghosh S K, Taylor M E, Johnson V A, Emini E A, Deutsch P, Lifson J D, Bonhoeffer S, Nowak M A, Hahn B H, Saag M S, Shaw G M. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Science. 1995;273:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu J C, Warren T C, Adams J, Proudfoot J, Skiles J, Raghavan P, Perry C, Potocki I, Farina P R, Grob P M. A novel dipyridodiazepinone inhibitor of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase acts through a nonsubstrate binding site. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2022–2026. doi: 10.1021/bi00222a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H, Myers C E, Broder S. Clinical pharmacology of 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (zidovudine) and related dideoxynucleosides. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:726–738. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909143211106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]