Abstract

Background: Mental illness in children and youths has become an increasing problem. School-based mental health services (SBMHS) are an attempt to increase accessibility to mental health services. The effects of these services seem positive, with some mixed results. To date, little is known about the implementation process of SBMHS. Therefore, this scoping review synthesizes the literature on factors that affect the implementation of SBMHS. Methods: A scoping review based on four stages: (a) identifying relevant studies; (b) study selection; (c) charting the data; and (d) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results was performed. From the searches (4414 citations), 360 were include in the full-text screen and 38 in the review. Results: Implementation-related factors were found in all five domains of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. However, certain subfactors were mentioned more often (e.g., the adaptability of the programs, communication, or engagement of key stakeholders). Conclusions: Even though SBMHS differed in their goals and way they were conducted, certain common implementation factors were highlighted more frequently. To minimize the challenges associated with these types of interventions, learning about the implementation of SBMHS and using this knowledge in practice when introducing SBMHS is essential to achieving the best possible effects with SMBHSs.

Keywords: implementation, school-based mental health services, mental health, scoping review

1. Background

Mental illness in children and youths has become a public health concern. Symptoms can range from mild and short-term problems, such as mild anxiety or depressive symptoms, to more severe and long-term forms of diagnosed anxiety disorders or major depression [1]. An estimated 12–30% of school-age children suffer from mental illness of sufficient intensity to adversely affect their education [2]. The vulnerability to mental illness is highest during childhood and adolescence [3]. Within the last decade, an increase in diagnoses related to mental ill-health has been noted [4]. An estimated 50% of all mental illnesses begin before the age of 14, and three-quarters of mental ill-health occurs before the age of 25 [5].

Tremendous social costs result from the consequences of leaving mental ill-health in children and youths untreated. These consequences may range from poor educational attainment, compromised physical health, substance abuse, juvenile delinquency, and unemployment to even premature mortality (e.g., suicide [6,7,8]). In line with that, cost-benefit analyses of mental health programs have found these programs result not only in economic productivity gains but also improved health [9,10].

Despite this, mental ill-health of children and youths is often not identified and treated in a timely way. Estimations show that up to 75% of students suffering from mental ill-health receive inadequate treatment or are not treated at all [11,12]. Consequently, mental ill-health often manifests in adulthood [5,13], which is unfortunate because many children and youths have originally mild or moderate symptoms [14]), and thus early identification and prevention can have beneficial effects [12,14,15]. Hence, there is an unmet need for mental health services for children and youth.

2. Mental Health Services Provided in Schools

Education and health are closely interlinked; school is important for one’s social and emotional development, and, therefore, school has an effect on health [16]. Moreover, due to compulsory school attendance, the majority of children and youths spend a considerable amount of time in schools, making schools an ideal environment to provide timely and convenient access to mental health services, including early identification, prevention, and interventions to prevent the escalation of mental ill-health [17]. In addition, providing services related to mental ill-health within the school setting has additional benefits such as cost efficiency and good accessibility to the services [18].

While school-based mental health services (SBMHS) may vary widely in focus, format, provider, and approach [19], they are all united in the fact that schools collaborate with health services to provide support for children and youths who are at risk of or have experienced mental ill-health. An SBMHS encompasses “any program, intervention, or strategy applied in a school setting that was specifically designed to influence students’ emotional, behavioral, and/or social functioning” [20](pp.224).

Even though services related to mental ill-health can be found outside the school setting, these community mental health services are often underutilized. For example, Kauffman, [21], Langer et al. [22], and Merikangas et al. [23] showed only 20% of children and youths received help to address their needs related to mental health, whereas Armbruster and Fallon [24], and McKay et al. [25] showed the help children and youths receive is often prematurely ended. Instead, SBMHS seem to resolve some of the known barriers that prevent access to mental health services for children and youths, such as lack of insurance, shortage of medical or psychological mental health professionals, mental health stigma, or the lack of transportation opportunities [26].

The effectiveness of SBMHS has been studied in several reviews and meta-analyses. In general, mental health programs through SBMHS were found to have a positive effect on emotional and behavior problems [20]. Hoagwood and Erwin [27] identified three types of services that had a clear impact (i.e., cognitive behavioral techniques, social skills training, and teacher consultation models). Other studies evaluating multifaceted and multilevel interventions showed improvements to mental health outcomes [28,29]. However, Caldwell et al. [30], focusing on SBMHS at secondary schools for youths with depression and anxiety, found limited evidence for their effectiveness. Fazel et al., [31] suggested these results might be premature and that long-term follow-ups should be applied to investigate effectiveness. Systematic reviews on the effect of SBMHS on specific target groups such as primary school children [32] or elementary school children [33] showed positive effects on their mental health. To conclude, even though these studies generally indicate positive effects of SBMHS, general conclusions are made difficult by the heterogeneity of interventions and evaluation designs used [34].

Besides the different definitions, the variety of programs included under the SBHMS umbrella, and the different designs for evaluation, these programs are complex, which also makes the implementation process potentially challenging. For example, Rones and Hoagwood [20] identified some features associated with the implementation that are important for the maintenance and sustainability of SBHMS programs (e.g., including various stakeholders, using different modalities, and integrating the intervention into the regular classroom curriculum). Without shedding more light on the implementation of SBMHS, there can be a risk of drawing false conclusions about the effectiveness of the programs. For instance, the lack of effects can be due to poor implementation instead of a failure of the theory underpinning the program [35]. In line with this reasoning, there has been a call to provide more clarity on the implementation of SBMHS [20,36].

3. Aim of the Review

This scoping review aimed at synthesizing the literature on the implementation of SBHMS. By doing so, we aim to increase the understanding of the systemic conditions and factors that affect the implementation of SBHMs.

The following research question will be addressed: Which factors are important for the implementation of school-based mental health services (SBMHS)? To systematize the findings, the factors relevant for implementing SBMHS will be structured according to Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) that differentiates between characteristics of the intervention and individuals using the intervention, the inner and outer context as well as the process of implementing.

4. Method

4.1. Study Design

To address the study aim, we performed a scoping review to identify barriers and enablers of the implementation of SBHMs. This method was chosen to provide a broad overview of implementation-related factors for SBHMs [37]. We followed the procedure outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [38]. After identifying the research question we (1) identified relevant studies, (2) selected studies, (3) charted the data, and (4) collected, summarized, and reported the results. Steps 1–3 are described in the Section 4, whereas Step 4 is presented in the Section 5.

4.2. Identify Relevant Studies

The search was conducted on 7 May 2019. The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a team of informatics experts from the university library at Karolinska Institutet. Based on several example papers focusing on SBHMs, and in discussion with representatives from the Swedish Public Health Agency and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, potential keywords were identified. The search strategy included conducting searches in four databases: Medline, Eric, PsycINFO, and Web of Science (see Appendix A). Articles published up to May 2019 were included in the search. The informatics team provided a full list of references after duplicates had been removed. Articles were also found and added through manual searches based on recommendations.

Simultaneous with developing the search strategy, eligibility criteria for relevant studies were defined [38]. To be included, studies were required to focus on SBMHS and to have been conducted through a collaboration of school staff together with staff from social services and/or health-care services. The interventions had to address children and youths’ mental health and be published in English or a Scandinavian language. In addition to peer-reviewed journals, reports, and dissertations were included. Mental health was defined broadly and based on a definition by the Swedish Committee on Child Psychiatry [39], where mental ill-health is children’s lasting symptoms that prevent them from optimal functioning and development and that cause suffering. This included internalized mental health symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depressive symptoms, psychosomatic symptoms, eating disorder symptoms, and self-harming behaviors), externalized mental health symptoms (e.g., neuropsychiatric impairment, or behavioral problems), and indicators of psychological problems (e.g., school problems, trauma, or problems at home). Two reviewers tested the eligibility criteria on 40 articles from the final search. Inconsistencies in interpretations were discussed within the research group and with representatives from the Swedish Public Health Agency and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, and thereafter modified to clarify the criteria.

4.3. Select Studies

All studies were screened to eliminate those that were not in line with the research question [38]. Rayyan, a software program that facilitates the screening process, was used [40]. Two authors (A.R. and M.R.S.) reviewed articles in addition to two research assistants. First, study titles and abstracts were evaluated based on the eligibility criteria in duplicate by two independent reviewers. Throughout the process, the reviewers met to discuss the eligibility criteria to confirm consensus, and modifications of the criteria were made to increase clarity (see Appendix B for eligibility criteria). The evaluation of titles and abstracts was finished in July 2019. The reviewers’ conflicting decisions were compared after completion. In the cases of inconsistencies in the decisions, the titles and abstracts were re-read and discussed in the reviewers’ group to reach a consensus. In addition, searches of the reference lists from relevant articles were also conducted to find potentially relevant articles (i.e., snowball search). These additional articles were screened in the same way as the original articles.

In the next step, the full texts of the included studies from the title and abstract evaluation were accessed for final inclusion. Three authors (A.R., M.R.S., and M.S.) and two research assistants reviewed articles in full text. As in the first step, the studies were assessed by two independent reviewers, and conflicting decisions were discussed to reach a consensus about the inclusion or exclusion of the study. The full-text evaluation was finished in November 2020.

4.4. Chart Data

In the next stage, key information from the included studies where charted [38]. The following information was collected from all included studies: (a) authors, (b) year of publication, (c) journal, (d) country of origin, (e) aim of the study, (f) study design, (g) method of data collection, (h) setting, (i) name of the intervention, (j) description of the intervention, (k) target groups for the intervention, (l) collaboration partners involved in conducting the intervention, (m) mental health challenge of the intervention target group, and (n) information about the implementation of the intervention. To test the chart template, all reviewers (A.R., M.R.S., M.S., and two research assistants) charted data from the same five included articles and compared the extracted data. Any inconsistencies were discussed, and the template was modified to increase clarity. Based on the information about the focus of the interventions and their target groups, these interventions were then categorized as universal, selective, or indicated. Universal interventions targeted all children, whereas selective interventions focused on risk groups and indicated interventions were provided to children and youths who were already struggling with their mental health.

To organize and categorize the information related to implementation, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR, [41]) (for more information, see https://cfirguide.org, accessed on 10 February 2022) was used as a conceptual framework to structure the extracted information. CFIR clusters factors related to the implementation into five categories (intervention characteristics, inner setting, outer setting, characteristics of the individual, and implementation process).

The intervention characteristics describe the source of the intervention (i.e., perceptions of the source of the intervention), the evidence strength and quality that the intervention will have desired outcomes, the perceived advantage of implementing this intervention compared to other interventions (i.e., relative advantage), how complex and adaptable the intervention is as well as if the intervention can be tested small-scale first. The costs associated with the intervention as well as the perception about how the intervention is design, packaged, and presented also describe important intervention characteristics. The outer setting of the organization where the intervention is implemented is described by the prioritization of patient needs and the resources allocated to patient needs by the organization, in how fare the organization is part of a larger network (i.e., cosmopolitanism), if other organizations have implemented the intervention hence, there is peer pressure to also implement the intervention and if there are external policies and incentives that may affect the implementation of the intervention. The organization’s inner setting is described by structural characteristics (e.g., age, maturity or size of the organization), the nature and quality of networks as well as (in)formal communication within the organization as well as the culture (i.e., existing norms, values, or assumptions made by employees). Moreover, implementation climate (i.e., the capacity to implement change) is an important characteristic that is further differentiated in the tension for change (i.e., the perception that the current situation is intolerable and requires change), the compatibility of the intervention with existing workflows and norms, the relative priority the intervention is perceived to have, existing incentives and rewards that exist in the organization that affect the implementation process as well as the existence of a learning climate and clear goals and feedback related to the intervention. Another important factor of the inner context is the organization’s readiness for implementation (i.e., the commitment to the decision of implementing the intervention). Here the involvement and commitment of leaders (i.e., leadership engagement), the amount of dedicated resources for the intervention, as well as access to knowledge and information about the intervention and its implementation are important. Characteristics of individuals is another important factor according to CFIR. It is defined by individuals’ knowledge and beliefs about the intervention (e.g., attitudes towards the intervention), individuals’ belief in their own capacity to execute the intervention (i.e., self-efficacy), the phase of change individuals are in, but also individuals’ identification with the organization as well as personal characteristics such as motivation, value, or learning style (i.e., other personal attributes). The implementation process according to CFIR is categorized in a planning phase (e.g., schemes or methods that are developed in advance), engaging, executing, and reflecting and evaluating phase. Engaging, that is the involvement of appropriate individuals is further differentiated in the engagement of opinion leaders, (in)formally appointed implementation leaders, champions as well as external change agents.

Information from included studies that related to the implementation of SBMHS was extracted, and, in the next step, categorized based on the CFIR domains and their more specific subtopics.

5. Results

5.1. Included Studies

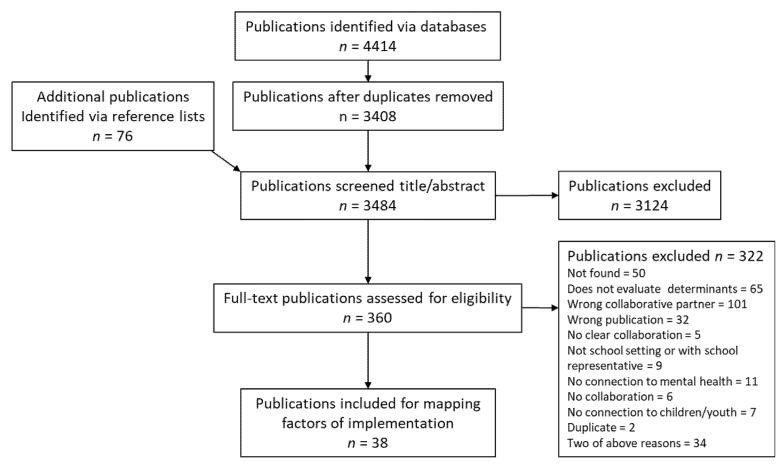

The data search resulted in 4414 studies that were potentially relevant to the research question of this scoping review. After 1006 duplicates were removed, 3408 studies remained and were included in the screening of titles and abstracts, resulting in 360 potentially eligible studies. Of these, 38 studies were included in the review after full-text screening. The PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1) summarizes the screening steps and the numbers of included and excluded studies in each step of the screening.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for this review. Note: Eligibility criteria are presented in Appendix B.

5.2. Study Characteristics

The 38 studies were published between 1996 and 2018 (see Table 1). The majority of studies were conducted in the United States (n = 22), followed by Great Britain (n = 7), Australia (n = 5), and Canada (n = 2). One study was conducted in Finland and one in Sweden. The SBMHS included universal (n = 16), selective (n = 7), and indicated interventions (n = 14). For two SBMHS, the interventions seemed a mixture of selective and indicated interventions. Examples of universal interventions included providing mental health support services to all students or promoting school readiness by creating emotionally supportive classrooms. Examples of selective interventions were introducing a stress-reducing early intervention team to student cases with a risk of mental ill health or establishing collaborations between schools and mental health services to improve psychosocial functioning of students with learning disabilities at risk of mental ill health. Examples of indicated interventions were improving communications between caretakers of children with ADHD or implementing a social skills program to promote children’s cooperative skills and anger management. The majority of SBMHS (n = 12) focused on improving mental health in general, whereas others focused on more specific issues (e.g., ADHD n = 5, emotional and behavioral problems n = 4, or depression n = 3). Most studies described programs where schools collaborated with mental health services (n = 19), whereas seven programs included collaboration between schools and health-care services. Social services were involved in six programs.

Table 1.

Information about the studies.

| Authors, Year |

Country | Data Collection |

Target Intervention Group |

Participating Actors | Type of Issue |

Intervention Name/Goal | Intervention Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson-Butcher et al. [42] | USA | Quantitative | Students in 3rd, 6th, 8th, and 12th grades |

School, health-care providers, social service | Students at risk for poor academic and developmental outcomes |

Ohio Community Collaboration Model for School Improvement (OCCMSI). Help schools and districts expand improvement efforts for at-risk children. |

Selective |

| Atkins et al. [43] | USA | Quantitative | School teachers in urban, deprived areas |

School and mental health services | ADHD | Increase the use of practices for children with ADHD. | Selective |

| Axberg et al. [44] | Sweden | Quantitative | Youth with externalizing problems |

School, mental health services |

Externalizing behavior | Marte Meo (MM) and Coordination Meeting (CM). Help children with externalizing problems and help their families. |

Indicated |

| Baxendale et al. [45] | USA | Qualitative | Youth with communication needs |

School, health care | Communication disorder | The Social Communication Intervention Project (SCIP). Enhance communication skills. |

Indicated |

| Bellinger et al. [46] | USA | Quantitative | Children (ages 3–8) who experienced frequent noncompliance at home and school |

School, mental health services |

Behavioral and emotional problems | Conjoint Behavioral Consulting (CBC). Address student needs via evidence-based interventions, involve and engage families in their child’s education, and facilitate partnerships and build relationships between schools and families. |

Indicated |

| Bhatara et al. [47] | USA | Qualitative | Teachers | School, mental health services, social services | ADHD | Swanson, Kotkin, Agler, M-Flynn and Pelham Scale-Teacher Version (T-SKAMP). Promote grading efficacy for children with ADHD. | Universal |

| Bruns et al. [48] | USA | Quantitative | All students at a public elementary school |

School, mental health services |

Emotional and behavioral problems | Expanded School Mental Health (ESMH). Provide school-based mental health services. |

Universal |

| Capp [49] | USA | Qualitative | School students and staff and parents | School, mental health services |

Diagnosable mental health disorders | Our Community, Our Schools (OCOS). Provide easy access to mental health promotion and treatment for students and their families, including access for those without insurance. |

Universal |

| Clarke et al. [50] | UK | Mixed | School nurses and elementary school students, aged 10–11, in deprived areas | School, mental health services, and social services |

General mental health issues | Facilitate accessible mental health support for young people, provide a problem- solving model for adolescents who have mental health issues, and support the role of school nurses by enhancing of their skills in mental health. |

Universal |

| Fazel et al. [51] | UK | Quantitative | Refugee children and school staff | Schools and mental health services | Risk of emotional and behavioral problems |

Provide a mental health service for refugees. |

Selective |

| Fiester and Nathanson [52] | USA | Qualitative | School students | Schools and health-care providers | General mental health issues | Provide violence prevention and mental health services. |

Universal |

| Foy and Earls [53] | USA | Qualitative | Community stakeholders, teachers, and parents | Schools and health-care providers | ADHD | Increase practice efficiency and improve practice standards for children with ADHD. |

Indicated |

| Goodwin et al. [54] | USA | Quantitative | Children older than 5 years in child-care centers, preschools, or in a child-care provider’s home care |

Schools, mental health services, and health-care providers | Emotional or behavioral problems |

The Childreach program. Decrease violent and aggressive behavior in preschool-age children. |

Selective |

| Hunter et al. [55] | UK | Qualitative | Students in secondary education |

Schools and mental health services | General mental health issues |

Enhance the effectiveness of the interface between primary care and specialist CAMHS services. |

Universal |

| Jaatinen et al. [56] | Finland | No info | Children and adolescence |

Schools, mental health services, health-care providers, and social services | Mental health and psychosocial problems |

Provide psychosocial support for schoolchildren via networking family counselling services. |

Universal |

| Jennings et al. [57] | USA | Mixed | Youth in an urban school district and their families |

Schools and mental-health services |

General mental health issues |

Dallas (Texas) public school initiative. Provide physical health, mental health, and other support services for students and their families. |

Universal |

| Juszczak et al. [58] | USA | Quantitative | All children who visited a clinic or school mental-health service |

Schools and health-care providers | General mental health issues |

School-Based Health Centers. Facilitate access to care. |

Universal |

| Khan et al. [59] | Australia | Qualitative | Secondary- school students |

Schools, mental health services, and health-care providers | General mental health |

MindMatters. Improve health, well-being, and education outcomes in secondary schools in south-west Sydney. |

Selective |

| Kutcher and Wei [60] | Canada | Mixed | School students | Schools, mental-health services, health-care providers, and social services |

General mental health services |

The School-Based Pathway to Care Model. Enhance the collaboration between schools, health-care providers, and community stakeholders to meet the need for mental-health support for adolescents. |

Universal |

| Li-Grining et al. [61] | USA | Quantitative | All caregiving adults (e.g., teachers) and children from a preschool |

Schools, mental-health services, and social services |

General emotional and behavioral issues |

Chicago School Readiness Project (CSRP). Promote low-income young children’s school readiness by creating emotionally supportive classrooms and by fostering preschoolers’ self-regulatory competence. |

Universal |

| Maddern et al. [62] | UK | Mixed | Children with severe emotional and behavioral problems and their parents |

Schools and mental-health services |

Severe emotional and behavioral problems | Promote children’s cooperative skills and anger management. |

Indicated |

| Mcallister et al. [63] | Australia | Quantitative | 13-year-old children in rural areas | Schools and mental-health services |

Psychological distress | Icare-R. Promote mental health. |

Universal |

| Mckenzie et al. [64] | UK | Quantitative | Students in a rural area and guidance staff | Schools and mental-health services |

General mental health issues |

Provide community-based school counselling services. | Universal |

| Mellin and Weist [65] | USA | Qualitative | Elementary/middle (combined in this district) and high school students |

Schools and mental-health services |

General mental health |

Enhance collaboration between schools and mental health services. |

Universal |

| Mishna and Muskat [66] | Canada | Mixed | Students with various social, emotional, and behavioral problems; their families; school peers; school personnel; and social workers | Schools, mental-health services, and social services |

Learning disabilities and psychosocial problems |

Improve the psychosocial functioning of high-risk students with learning disabilities and psychosocial problems and increase the understanding of their learning disability. |

Selective |

| Moilanen and Med [67] | USA | Mixed | Students in grades 8 through 12, school personnel, and parents |

Schools and mental-health services |

Depression and suicide |

Prevent depression and suicide within high schools and local communities |

Universal/Indicated |

| Mufson et al. [68] | USA | Quantitative | Depressed youth | Schools, mental-health services, health-care providers, and social services |

Depression | IPT-A. Reduce depressive symptoms and improve interpersonal functions. |

Indicated |

| Munns et al. [69] | Australia | Qualitative | Primary school-aged children who experienced loss (such as a death in the family, parental divorce, or other painful transitions) |

Schools and health-care providers | Traumatic events | The Rainbow program. Support children who have experienced traumatic events |

Indicated |

| O’Callaghan and Cunningham [70] | UK | Mixed | Primary-age children, 8- to 11-year-old pupils | Schools and mental-health services |

Anxiety, depression, or low self-esteem |

Cool Connections. Decrease depression and the risk of suicide and improve self-perception. |

Indicated |

| Owens et al. [71] | USA | Mixed | Students in kindergarten through 6th grade |

Schools and mental-health services |

ADHD | Youth Experiencing Success in School (YESS). Enhance the use of EBTs in schools, improve the academic and behavioral functioning of children, enhance home–school collaboration and support services for parents, and provide ongoing collaborative consultation for teachers. |

Indicated |

| Panayiotopoulos and Kerfoot [72] | UK | Mixed | Pupils, their family, and school staff |

Schools, mental-health services, and social services |

School exclusion |

A home and school support project (HASSP). Prevent school exclusions. |

Indicated |

| Powell et al. [73] | USA | Quantitative | Students in grades 7 to 12 | Schools and mental health services | Emotional and behavioral disorders and educational disabilities | Help students return to public-school settings as quickly as possible. |

Indicated |

| Rosenblatt et al. [74] | USA | Quantitative | Special education students/students with SED | Schools and mental-health services |

Severe emotional disturbance (SED) |

Provide collaborative mental health and education services. |

Indicated |

| Stanzel [75] | Australia | Qualitative | High school students in rural areas |

Schools and health-care providers | General mental health |

Outreach youth clinic (OYC). Promote better health for young people by ensuring coordination between schools and community health and support s ervices. |

Universal |

| Vander Stoep et al. [76] | USA | Quantitative | 6th-grade students, the majority in special-needs groups | Schools and mental-health services |

Emotional distress |

Developmental Pathways Screening Program (DPSP). Identify youth experiencing significant emotional distress who need support services. |

Universal |

| White et al. [77] | USA | Quantitative | Students returning to school after a psychiatric hospitalization or other prolonged absence due to mental-health reasons and their families |

Schools and mental-health services |

General mental-health issues |

Bridge for Resilient Youth in Transition. Support academic and clinical outcomes for high school students returning to school after a mental-health crisis. |

Selective and indicated |

| Winther et al. [78] | Australia | Quantitative | All children from preparatory to grade 3 (ages 4–10 years), teachers, and parents |

School, health care and mental-health services |

Oppositional defiance disorder/conduct disorder (ODD/CD) |

Royal Children’s Hospital, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service and Schools’ Early Action Program. Address emerging ODD/CD. |

Indicated |

| Wolraich et al. [79] | USA | Mixed | ADHD children and their caregivers, medical services, and teachers |

Schools and health-care providers | ADHD | Improve communication between individuals who care for children with ADHD. | Indicated |

Notes: Universal interventions targeted all children, whereas selective interventions focused on risk groups and indicated interventions were provided to children and youths who were already struggling with their mental health.

5.3. Implementation Factors

A summary of factors related to the implementation of an SBMHS is presented in Table 2. More specific information about the factors influencing implementation in each of the included studies can be found in Table 3.

Table 2.

Implementation factors related to SBMHS.

| CFIR Domains | All Studies n = 38 |

Universal Interventions n = 17 |

Selective Interventions n = 7 |

Indicated Interventions n = 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

47 | 17 | 8 | 22 |

| Intervention Source | - | - | - | - |

| Evidence Strength and Quality | 3 | - | 2 | 1 |

| Relative Advantage | 2 | 1 | - | 1 |

| Adaptability | 11 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Trialability | 3 | 1 | - | 2 |

| Complexity | 2 | 2 | - | - |

| Design Quality and Packaging | 19 | 9 | 2 | 8 |

| Cost | 7 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

|

19 | 9 | 2 | 8 |

| Patient Needs and Resources | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Cosmopolitanism | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Peer Pressure | 2 | - | 1 | 1 |

| External Policy and Incentives | 10 | 6 | - | 4 |

|

62 | 30 | 12 | 20 |

| Structural Characteristics | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Networks and Communications | 17 | 9 | 3 | 5 |

| Culture | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Implementation Climate | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - |

|

2 | 1 | - | 1 |

|

4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

|

- | - | - | - |

|

9 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

|

- | - | - | - |

| Readiness for Implementation | - | - | - | - |

|

2 | 2 | - | - |

|

16 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

|

2 | 2 | - | - |

|

11 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Knowledge and Beliefs About the Innovation |

9 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Self-Efficacy | - | - | - | - |

| Individual Stage of Change | - | - | - | - |

| Individual Identification with Organization |

- | - | - | - |

| Other Personal Attributes | 2 | - | 1 | 1 |

|

40 | 20 | 9 | 11 |

| Planning | 5 | 5 | - | - |

| Engaging | - | - | - | - |

|

3 | - | 2 | 1 |

|

2 | 1 | 1 | - |

|

- | - | - | - |

|

1 | - | 1 | - |

|

17 | 10 | 3 | 4 |

|

9 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Executing | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Reflecting and Evaluating | 2 | 1 | - | 1 |

Table 3.

Implementation-related information per study.

| Reference | Process | Inner Setting |

Outer Setting |

Intervention Characteristics |

Individuals’ Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson-Butcher et al. [42] | Implementation Climate—Relative Priority Implementation Climate—Goals and Feedback |

Adaptability | |||

| Atkins et al. [43] | Engaging Opinion Leaders | ||||

| Axberg et al. [44] | Networks and Communications | Trialability Design Quality and Packaging Adaptability |

|||

| Baxendale et al. [45] | Reflecting and Evaluating Planning Engaging Innovation Participants |

Implementation Climate— Compatibility Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources |

External Policy and Incentives |

Design Quality and Packaging Adaptability Evidence Strength and Quality |

Knowledge and Beliefs |

| Bellinger et al. [46] | Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources |

External Policy and Incentives |

Cost Design Quality and Packaging |

||

| Bhatara et al. [47] | Engaging Key Stakeholders | Cosmopolitanism | Design Quality and Packaging | ||

| Bruns et al. [48] | Design Quality and Packaging | ||||

| Capp [49] | Engaging Key Stakeholders Engaging Innovation Participants |

Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources |

Design Quality and Packaging Cost |

||

| Clarke et al. [50] | Engaging Key Stakeholders | ||||

| Fazel et al. [51] | Engaging Innovation Participants | Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources Networks and Communications |

Peer Pressure | Evidence Strength and Quality | |

| Fiester and Nathanson [52] | Planning Engaging Key Stakeholders |

Implementation Climate—Relative Priority Readiness for Implementation—Leadership Engagement Implementation Climate—Goals and Feedback Culture Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources |

External Policy and Incentives Cosmopolitanism |

Complexity | |

| Foy and Earls [53] | Engaging Key Stakeholders | External Policy and Incentives Cosmopolitanism |

|||

| Goodwin et al. [54] | Cosmopolitanism | Cost | Other Personal Attributes |

||

| Hunter et al. [55] | Engaging Key Stakeholders | Implementation Climate— Compatibility Readiness for Implementation—Access to Information Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources Implementation Climate—Goals and Feedback Culture Networks and Communications |

External Policy and Incentives |

Relative Advantage Trialability |

|

| Jaatinen et al. [56] | Engaging Key Stakeholders | Networks and Communications | |||

| Jennings et al. [57] | Engaging Innovation Participants Engaging Key Stakeholders |

Networks and Communications | External Policy and Incentives |

Knowledge and Beliefs |

|

| Juszczak et al. [58] | External Policy and Incentives |

||||

| Khan et al. [59] | Engaging Key Stakeholders Engaging Innovation Participants Engaging External Change Agent Engaging Formally Appointed Internal Implementation Leaders |

Structural Characteristics Networks and Communications Culture Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources |

Design Quality and Packaging Cost |

Knowledge and Beliefs |

|

| Kutcher and Wei [60] | Reflecting and Evaluating Engaging Key Stakeholders |

Networks and Communications Implementation Climate—Goals and Feedback |

External Policy and Incentives |

Adaptability Design Quality and Packaging |

Knowledge and Beliefs |

| Li-Grining et al. [61] | Planning | Networks and Communications Culture |

Complexity Design Quality and Packaging |

||

| Maddern et al. [62] | Engaging Innovation Participants Engaging Key Stakeholders |

Implementation Climate Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources Implementation Climate—Goals and Feedback Networks and Communications Structural Characteristics |

Patient Needs and Resources Peer Pressure |

Adaptability Design Quality and Packaging |

|

| Mcallister et al. [63] | Implementation Climate—Relative Priority Networks and Communications |

Design Quality and Packaging |

|||

| Mckenzie et al. [64] | Engaging Innovation Participants | Readiness for Implementation—Leadership Engagement Networks and Communications |

Design Quality and Packaging |

||

| Mellin and Weist [65] | Planning Engaging Key Stakeholders |

Networks and Communications Structural Characteristics Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources Culture Implementation Climate—Goals and Feedback |

External Policy and Incentives |

Knowledge and Beliefs |

|

| Mishna and Muskat [66] | Engaging Opinion Leaders Engaging Key Stakeholders |

Implementation Climate—Goals and Feedback Networks and Communications Structural Characteristics |

Design Quality and Packaging Evidence Strength and Quality Adaptability |

Knowledge and Beliefs |

|

| Moilanen and Med [67] | Engaging Key Stakeholders | Design Quality and Packaging |

|||

| Mufson et al. [68] | Engaging Innovation Participants | Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources |

Adaptability Design Quality and Packaging |

||

| Munns et al. [69] | Engaging Key Stakeholders | Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources Networks and Communications |

Cosmopolitanism | Design Quality and Packaging Cost Adaptability |

|

| O’Callaghan and Cunningham [70] | Networks and Communications | Design Quality and Packaging |

|||

| Owens et al. [71] | Planning Engaging Opinion Leaders Executing |

Networks and Communications Implementation Climate—Goals and Feedback Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources |

External Policy and Incentives |

Trialability | Other Personal Attributes Knowledge and Beliefs |

| Panayiotopoulos and Kerfoot [72] | Engaging Key Stakeholders | Implementation Climate—Goals and Feedback |

Adaptability | Knowledge and Beliefs |

|

| Powell et al. [73] | Adaptability | ||||

| Rosenblatt et al. [74] | Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources Culture |

Knowledge and Beliefs |

|||

| Stanzel [75] | Engaging Formally Appointed Internal Implementation Leaders | Networks and Communications Readiness for Implementation—Access to Knowledge and Information |

Design Quality and Packaging Adaptability |

||

| Vander Stoep et al. [76] | Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources |

Cosmopolitanism | Cost | ||

| White et al. [77] | Engaging Key Stakeholders | Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources Implementation Climate—Relative Priority |

|||

| Winther et al. [78] | Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources |

Cost Design Quality and Packaging |

|||

| Wolraich et al. [79] | Engaging Innovation Participants | Relative Advantage |

Generally, implementation-related information could be found for all five CFIR domains, but some of the subfactors in CFIR seemed to be particularly relevant to implementing SBMHS. Frequently named intervention characteristics were the adaptability of the intervention, the design quality and packaging of the intervention, and the costs associated with the intervention. For example, programs were often adapted to the content of the staff training, the way the treatment within the program was conducted, and the evaluation of the treatment compliance to fit to the local context [68]. Moreover, adaptation of the program to the local conditions and the target group was crucial [66]. One example of a concrete adaptation was to change the language used in the program so that students with diverse backgrounds could be reached [66]. Language and the way the program was packaged didactically was also identified in another study as culturally inappropriate and a hindrance to implementation of the program for certain minority groups [69]. Furthermore, the service range of the program as well as the facilities (e.g., rooms used for the programs) needed to be adapted based on the needs of the children and youths in that school [75]. Adaptability was more often mentioned when indicated programs were implemented compared to universal or selective programs.

Information related to the outer setting was mainly captured by the subfactors of cosmopolitanism and external policies and incentives. One reoccurring example related to external policies was the different compensation systems among cooperating actors [45,46]. Similarly, the different actors involved in the programs needed to gather consent from individual legal guardians of children and youths, as well as applying different principles of confidentiality, which also provided a challenge [60,65]. Having an established network with other organizations was also important for implementation. For example, when one needed to hire staff who could carry out the program, recruiting from organizations where established contacts existed facilitated the process (e.g., [52]).

Inner-setting factors that primarily were mentioned were the networks and communication, goals, and feedback, as well as the available resources that contributed to a readiness for the implementation. In particular, the need for an open dialogue between actors within the SBHMS was perceived as a cornerstone for developing trust and respect between actors [71]. A supportive administration department was highlighted as important for these multi-actor programs [80]. Dysfunctional communication could result in the loss of important information about students who participated in the program, which could affect the program and its outcomes negatively [55]. Clear goals and feedback as part of the implementation climate were also frequently mentioned. Particularly, different goals by various actors was highlighted as a potential challenge with SBMHS (e.g., [52]). Moreover, having sufficient resources such as suitable premises [51], the right technical aids [71], or adequate funding for the new initiative [81] was also important. In particular, studies on indicated interventions mentioned the availability of resources.

Regarding individuals’ characteristics is important for the implementation of SBHMs; in particular, actors’ knowledge of and belief in the program were mentioned. For example, when the actors involved strongly believed that the program would improve children’s mental health, staff’s motivation to work with the program increased [57].

When it comes to the process related to the program, engagement of key stakeholders and the participants in the interventions was frequently mentioned. For example, in Panayiotopoulos and Kerfoot [72], creating engagement with relevant actors was central to the implementation. These actors primarily included teachers and coordinators for nurses [69] and school management, as well as other staff at the school [59]. In another study, where a program for ADHD primarily focused on increasing the competence of physicians and teachers, the program did not achieve engagement of the targeted group, which affected the program’s effectiveness [79].

6. Discussion

Due to the increasing number of children and youths who are at risk of, and have experienced, mental ill-health, the efficient implementation of countermeasures such as SBMHS is essential. Therefore, this scoping review synthesized the available research on factors that influence the implementation of SBMHS. From 38 studies, information related to the implementation of SBMHS was gathered and structured. SBMHS have incorporated a variety of programs spanning from universal programs that target all students and aim at improving children and youths’ general mental well-being to programs that target specific individuals, either who were at risk for mental ill-health or who experienced mental ill-health. In addition, the SBMHS also varied in their focuses (i.e., the issues they primarily addressed). Whereas the universal programs focused on increasing general mental health or more specific facets of it (e.g., emotional or behavioral problems), the selective and particularly the indicated programs often addressed narrower topics (e.g., ADHD or depression). Most studies were conducted in English-speaking countries. Implementation-related factors of SBMHS for all five CFIR domains (i.e., intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of the individual, and process) were identified. However, information was primarily found around three of the five domains (i.e., intervention characteristics, inner setting, and process), and certain subfactors were mentioned more frequently than others were (i.e., design quality and packaging, adaptability, networks and communication, readiness for the implementation through available resources, engaging key stakeholders, and innovation participants).

6.1. Adapting of the Interventions

The design and packaging of the intervention was an often-mentioned factor and was often related to the adaptability of the intervention to the local context. Hence, for SBMHS implementation, being able to tailor a specific intervention to the needs and circumstances of the school and other actors involved was perceived important. Generally, adaptations have been discussed in relation to the fidelity of interventions, which presents the degree to which an intervention is carried out based on how it was described and originally tested when developed [82,83]. Fidelity has been an important factor in intervention implementation and is often studied as an implementation outcome [84]. However, real-world practice has shown that adaptations to interventions such as evidence-based interventions (EBIs) are in the majority of cases the rule rather than the expectation [85,86,87]. In recent years, adaptation has been discussed more frequently, but not as the opposite of fidelity as done before (e.g., [88]). Rather, adaptation is discussed in terms of how fidelity and adaptation can coexist when the core components of the intervention are preserved [89,90,91] and are necessary so that EBIs can result in value for all stakeholders when, for example, EBIs are implemented [92,93,94]. Examples of reasons for adaptation include increasing the fit between the intervention and context and being able to address multiple diagnoses or balance different outcomes [94]. Intervention strategies that aim at increasing this intervention–context fit could include community–academic partnerships, so that intervention developers and practitioners who shall work with the interventions collaboratively design the process [95]. Central is the transparency of adaptations, hence the conscious decisions and documentation about what is adapted, as well as how and for what reason, to avoid adaptation neglect, which may lead to the removal of the intervention’s central components, thereby threatening the intervention’s effectiveness [94]. In the case of SBMHS, where adaptations and the fit of existing design and packaging of programs seemed central, adaptations regarding the target groups or local conditions at schools were most relevant. However, another potential adaptation may concern implementing programs from other countries and hence other cultural settings [96].

6.2. Internal Collaboration and between Actors

SBMHS are essentially the collaboration of various actors who are relevant to children and youths’ mental health; that is, health-care providers, social-care providers, and schools. These three actors ultimately represent different organizations, which also means different primary goals, different ways of working, different cultures, and, potentially, different laws to which they relate. These organization-specific factors may represent challenges to smooth communication between actors when it comes to SBMHS, and they ultimately might make it harder to implement SBMHS successful. Organizational factors have been found to be critical for the successful implementation of evidence-based practices [97,98]. However, studies predominantly focus on one organization [99]; hence, the interorganizational alignment that may be of relevance for initiatives such as SBMHS has not received much research attention [99]. In line with the scarce empirical findings, theoretical frameworks also tend to focus on the one organizational setting. For example, in CFIR [41], organizational factors are categorized under the inner-setting domain. However, for SBMHS, the inner setting that may affect implementation is essentially several organizations’ inner settings. An exception is the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment framework, which in addition to the interorganizational context, also includes only a few details. Our results indicate that communication, which might be an essential part of interorganizational collaboration, is important for SBMHS implementation. In the future, the interorganizational alignment of organizational constructs [99] should be studied more closely. Closely related to the communication aspect, resource availability for the implementation of SBMHS was often named. Resource availability could be a sign of the overall prioritization of the intervention. However, schools have limited financial resources, and often staff already experience high demands [100] This might indicate that schools that introduce SBMHS might need to conduct a thorough analysis beforehand to understand what is required for the intervention to be feasible in this context.

Stakeholder engagement is central to successful implementation in general [101,102], and, of course, relevant to specific programs that are provided within SBMHS, e.g., school-based intervention for trauma [103]. Potential stakeholders relevant for SBMHS are district and school administrators, mental-health service providers, and educators, as well as students and their families. A particular focus should be placed on gaining their buy-in [104] to make an implementation successful. Continuous stakeholder engagement could also increase communication and facilitate making decisions related to adaptations and their documentation and evaluation.

6.3. Implications for Implementing SBMHS

Taken together, this scoping review can be used as a resource and starting point for schools and their collaboration partners that aim at implementing SBMHS in the future. Relevant factors for implementation are highlighted here that can be incorporated and covered when planning the implementation process. One suggestion for successful implementation is the use of multifaceted implementation strategies [105]. Schools could use the findings of this scoping review as guidance when planning SBMHS implementation strategies, which may increase the chances that an SBMHS results in the intended effects (i.e., an improvement in children and youths’ mental health). In addition, this study may also contribute to scholars placing more emphasis on the implementation process (i.e., its planning, execution, and evaluation). Process evaluation might be particularly important to increase our understanding of which implementation factors are essential for certain interventions [106]. Ultimately, increased focus on implementation sheds more light on the dilemma of theory failure versus implementation failure when it comes to understanding results from SBMHS evaluations.

7. Limitations

The limitations of this scoping review should be acknowledged. This scoping review includes studies that were published until May 2019. Later studies were not included as the pandemic most likely affected the educational system differently in different countries due to the measures and contract restriction that were introduced. Hence, implementation factors that can be found in studies conducted during the pandemic might therefore primary be a representation of the pandemic measure each country has introduced and might therefore not be comparable to a non-pandemic situation. Future studies should investigate SBMHS and mental health of children and youth in future studies further. In addition, most studies included did not have an explicit focus on studying the implementation of SBMHS. Therefore, we might only have captured the most relevant factors that affected SBMHS implementation that therefore often were mentioned in the Section 6. We also chose to define SBMHS in this paper as the collaboration of at least two actors, with schools being one and health care or social services the other one. This might have led to the exclusion of programs that have other constellations of collaboration partners. Based on program aims (i.e., improving mental health), we chose schools, health care, and social services as the central actors to be considered. The majority of the included studies were conducted in English-speaking countries, predominantly the United States, and only two were conducted in Nordic countries. However, schools, health-care services, and social services have major organizational differences compared to their respective counterparts in different countries. Hence, generalizability of results might be limited. However, certain implementation-relevant factors have been named in a variety of studies, which indicates that those seem to be important beyond the national specificities of the school, health care, and social service system.

8. Conclusions

This scoping review demonstrated that specific implementation factors seem to be more important in the implementation of SBMHS. Besides the need to study the implementation process explicitly, valuable practical guidance can extracted from this scoping review when new SBMHS are planned or existing services optimized.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank librarians Emma-Lotta Säätelä and Sabina Gillsund at the Karolinska Institutet University Library for helping with the development of search strategies and literature searches. We would also like to thank research assistants Irene Muli, Andreas Ekvall, and Paul Bengtsson for their work in the initial parts of the scoping review process. Furthermore, we would like to express our gratitude to the staffs of the Public Health Agency of Sweden and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, who provided valuable input during the different stages of this project.

Appendix A. Search Strategy

Documentation of search strategies

University Library search consultation group

Databases:

Medline (Ovid)

Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate)

PsycInfo (Ovid)

ERIC (ProQuest)

Total number of hits:

Before deduplication: 12,000

After deduplication: 8000

Comments:

Appendix A.1. Medline

| Interface: Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily Date of Search: 5 May 2019 Number of hits: 1095 Comment: In Ovid, two or more words are automatically searched as phrases; i.e., no quotation marks are needed |

Field labels exp/= exploded MeSH term /= non exploded MeSH term .ti,ab,kf. = title, abstract and author keywords adjx = within x words, regardless of order * = truncation of word for alternate endings |

| |

Appendix A.2. Web of Science Core Collection

| Interface: Clarivate Analytics Date of Search: 3 May 2019 Number of hits: 850 |

Field labels TS/TOPIC = title, abstract, author keywords and Keywords Plus NEAR/x = within x words, regardless of order * = truncation of word for alternate endings |

| |

Appendix A.3. Psycinfo

| Interface: Ovid Date of Search: 3 May 2019 Number of hits: 1238 Comment: In Ovid, two or more words are automatically searched as phrases; i.e., no quotation marks are needed |

Field labels exp/= exploded controlled term /= non exploded controlled term .ti,ab,id. = title, abstract and author keywords adjx = within x words, regardless of order * = truncation of word for alternate endings |

| |

Appendix A.4. ERIC

| Interface: ProQuest Date of Search: 3 May 2019 Number of hits: 1231 |

Field labels MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE = exploded subject heading MAINSUBJECT.EXACT non exploded subject heading TI,AB = title, abstract N/x = within x words, regardless of order * = truncation of word for alternate endings |

| (MAINSUBJECT.EXACT(“Mental Health” OR “Mental Disorders” OR “Psychopathology” OR “Adjustment (to Environment)” OR “Affective Behavior” OR “Depression (Psychology)” OR “Anxiety” OR “Fear” OR “Eating Disorders” OR “Aggression” OR “Sleep” OR “Pain” OR “Hyperactivity” OR “Social Problems” OR “Delinquency” OR “Antisocial Behavior” OR “Quality of Life” OR “Well Being” OR “Wellness” OR “Life Satisfaction” OR “Psychological Patterns” OR “Resilience (Psychology)”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT. EXPLODE(“Anxiety Disorders” OR “Self Destructive Behavior” OR “Emotional Disturbances” OR “Attention Deficit Disorders” OR “Behavior Disorders” OR “Substance Abuse” OR “Self Concept”) OR TI,AB((mental OR emotional OR psychiatric OR psychologic*) N/3 (disease* OR disorder* OR distress OR health OR illness* OR “ill health” OR illhealth OR instabilit* OR problem* OR symptom*))) AND (TI,AB((classroom* OR highschool* OR pupil* OR school* OR teacher*) N/3 (based OR environment* OR intervent* OR implement* OR setting* OR elementary or high or middle or primary or secondary)) OR (MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE (“Students” OR “Schools”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT(“Educational Environment” OR “Classroom Environment” OR “School Health Services” OR “School Nurses” OR “Ancillary School Services”) )) AND ((MAINSUBJECT.EXACT(“Interprofessional Relationship” OR “Interdisciplinary Approach”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Cooperation”)) OR TI,AB(collaborat* OR coordinat* OR cooperat* OR partnership* OR teamwork) OR TI,AB((“cross-disciplinar*” OR interagency* OR interdisciplinar* OR intersectoral* OR interinstitutional* OR interprofessional* OR multidisciplinar*) N/6 (care OR communicat* OR “health care” OR intervention* OR “mental health” OR program* OR relation* OR team* OR strateg*))) AND (MAINSUBJECT.EXACT(“Child Welfare” OR “Health Services” OR “Community Health Services” OR “Clinics” OR “Psychoeducational Clinics” OR “Psychiatric Services” OR “Psychological Services” OR “Social Work” OR “Primary Health Care”) OR TI,AB((emergenc* OR health OR psychiat* OR psycholog*) N/3 (care OR nursing OR practice* OR service*)) OR TI,AB(healthcare OR “mental health center*” OR “mental health clinic*” OR “mental health rehabilitation” OR “primary care” OR “psycho* rehabilitation” OR “social service*” OR “social work*” OR support* OR treat*)) AND (MAINSUBJECT.EXACT(“Program Evaluation” OR “Program Effectiveness” OR “Program Development” OR “Program Implementation” OR “Mental Health Programs”) OR TI,AB(barrier* OR determinant* OR effect* OR evaluat* OR facilitat* OR factor* OR implement* OR intervent* OR predict* OR program*)) Applied filters: Scholarly Journals OR Reports OR Dissertations and Theses | |

Appendix B. Eligibility Criteria

| Study Focus/Content | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|

Implementationof the

intervention |

Studies that describe:

|

Studies that describe:

|

| The Interventions |

|

|

| Collaborative partners |

|

|

| Arena of the intervention |

|

|

| Target group |

|

|

| Problem |

|

|

| Language |

|

|

| Type of publication |

|

|

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R., and H.H.; data extraction M.S., and M.R.S.; formal analysis, A.R., M.R.S., and H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.; review and editing: A.R., H.H., M.S., and M.R.S.; funding acquisition, A.R., and H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a research grant from the Public Health Agency of Sweden (Registration No. 4-1782/2019).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Public Health Agency of Sweden . Skolans Betydelse för Inåtvända Psykiska Problem Bland Skolbarn. Public Health Agency of Sweden; Solna, Sweden: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker B.E., Luthar S.S. Social-Emotional Factors Affecting Achievement Outcomes Among Disadvantaged Students: Closing the Achievement Gap. Educ. Psychol. 2002;37:197–214. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3704_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Caring for Children and Adolescents with Mental Disorders: Setting WHO Directions. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olfson M., Blanco C., Wang S., Laje G., Correll C.U. National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:81–90. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutter M., Moffitt T.E., Caspi A. Gene-environment interplay and psychopathology: Multiple varieties but real effects. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2006;47:226–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks T.L., Harris S.K., Thrall J.S., Woods E.R. Association of adolescent risk behaviors with mental health symptoms in high school students. J. Adolesc. Health. 2002;31:240–246. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cicchetti D., Rogosch F.A. A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002;70:6–20. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halfon N., Newacheck P.W. Prevalence and impact of parent-reported disabling mental health conditions among U.S. children. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1999;38:600–603. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199905000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chisholm D., Sweeny K., Sheehan P., Rasmussen B., Smit F., Cuijpers P., Saxena S. Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: A global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:415–424. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sallee C.M., Agemy E.M. Costs and Benefits of Investing in Mental Health Services in Michigan. Volume 11. Anderson Economic Group; East Lansing, MI, USA: 2011. pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lean D.S., Colucci V.A. Barriers to Learning: The Case for Integrated Mental Health Services in Schools. Rowman Littlefield Education; Washington, WA, USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stallard P. Promoting Children’s Well-Being. In: Skuse D., Bruce H., Dowdney L., Mrazek D., editors. Child Psychology and Psychiatry: Frameworks for Practice. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2011. pp. 72–77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim-Cohen J., Caspi A., Moffitt T.E., Harrington H., Milne B.J., Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler R.C., Avenevoli S., Costello J., Green J.G., Gruber M.J., McLaughlin K.A., Petukhova M., Sampson N.A., Zaslavsky A.M., Merikangas K.R. Severity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2012;69:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Research Council . In: Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. O’Connell M.E., Boat T., Warner K.E., editors. National Research Council; Washington, WA, USA: 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalsgaard S., McGrath J., Østergaard S.D., Wray N.R., Pedersen C.B., Mortensen P.B., Petersen L. Association of Mental Disorder in Childhood and Adolescence with Subsequent Educational Achievement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:797–805. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durlak J., Weissberg R., Dymnicki A.B., Taylor R.D., Schellinger K. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 2011;82:405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weist M.D., Evans S.W. Expanded School Mental Health: Challenges and Opportunities in an Emerging Field. J. Youth Adolesc. 2005;34:3–4. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-1330-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doll B., Nastasi B.K., Cornell L., Song S.Y. School-Based Mental Health Services: Definitions and Models of Effective Practice. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2017;33:179–194. doi: 10.1080/15377903.2017.1317143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rones M., Hoagwood K. School-Based Mental Health Services: A Research Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2000;3:223–241. doi: 10.1023/A:1026425104386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kauffman J.M. Characteristics of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders of Children and Youth. 7th ed. Merrill/Prentice Hall; New Jersey, NJ, UAS: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langer D.A., Wood J.J., Wood P.A., Garland A.F., Landsverk J., Hough R.L. Mental Health Service Use in Schools and Non-school-Based Outpatient Settings: Comparing Predictors of Service Use. Sch. Ment. Health. 2015;7:161–173. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9146-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merikangas K.R., He J., Burstein M., Swendsen J., Avenevoli S., Case B., Georgiades K., Heaton L., Swanson S., Olfson M. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2011;50:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armbruster P., Fallon T. Clinical, sociodemographic, and systems risk factors for attrition in a children’s mental health clinic. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 1994;64:577–585. doi: 10.1037/h0079571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKay M.M., Pennington J., Lynn C.J., McCadam K. Understanding urban child mental health service use: Two studies of child, family, and environmental correlates. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2001;28:475–483. doi: 10.1007/BF02287777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Committee on School Health School-Based Mental Health Services. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1839–1845. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoagwood K., Erwin H.D. Effectiveness of School-Based Mental Health Services for Children: A 10-Year Research Review. J. Child Fam. Stud. 1997;6:435–451. doi: 10.1023/A:1025045412689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonell C., Allen E., Warren E., McGowan J., Bevilacqua L., Jamal F., Legood R., Wiggins M., Opondo C., Mathiot A., et al. Effects of the Learning Together intervention on bullying and aggression in English secondary schools (INCLUSIVE): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:2452–2464. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31782-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shinde S., Weiss H.A., Varghese B., Khandeparkar P., Pereira B., Sharma A., Gupta R., Ross D.A., Patton G., Patel V. Promoting school climate and health outcomes with the SEHER multi-component secondary school intervention in Bihar, India: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:2465–2477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31615-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caldwell D.M., Davies S.R., Hetrick S.E., Palmer J.C., Caro P., López-López J.A., Gunnell D., Kidger J., Thomas J., French C., et al. School-based interventions to prevent anxiety and depression in children and young people: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fazel M., Kohrt B.A. Prevention versus intervention in school mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:969–971. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohamed N.E., Sutan R., Abd Rahim M.A., Mokhtar D., Rahman R., Johani F., Abd Majid M.S., Mohd Fauzi M.F., Azme M., Mat Saruan N., et al. Systematic Review of School-Based Mental Health Intervention among Primary School Children. J. Community Med. Health Educ. 2018;8:1–6. doi: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchez A.L., Cornacchio D., Poznanski B., Golik A.M., Chou T., Comer J.S. The Effectiveness of School-Based Mental Health Services for Elementary-Aged Children: A Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2018;57:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arenson M., Hudson P.J., Lee N., Lai B. The Evidence on School-Based Health Centers: A Review. Glob. Pediatric Health. 2019;6:2333794X19828745. doi: 10.1177/2333794X19828745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipsey M., Crosse S., Dunkle J., Pollard J., Stobart G. Evaluation: The state of the art and the sorry state of the science. New Dir. Program Eval. 1985;1985:7–28. doi: 10.1002/ev.1398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kern L., Mathur S.R., Albrecht S.F., Poland S., Rozalski M., Skiba R.J. The Need for School-Based Mental Health Services and Recommendations for Implementation. Sch. Ment. Health. 2017;9:205–217. doi: 10.1007/s12310-017-9216-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Brien K.K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., Baxter L., Tricco A.C., Straus S., Wickerson L., Nayar A., Moher D., O’Malley L. Advancing scoping study methodology: A web-based survey and consultation of perceptions on terminology, definition and methodological steps. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016;16:305. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.It Focuses on Life: Supporting and Caring for Children and Adolescents with Mental Health Problems. Final Report of the Committee on Child Psychiatry. National Public Inquiry 31. Ministry of Cities; Stockholm, Sweden: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Damschroder L.J., Aron D.C., Keith R.E., Kirsh S.R., Alexander J.A., Lowery J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson-Butcher D., Iachini A.L., Ball A., Barke S., Martin L.D. A University-School Partnership to Examine the Adoption and Implementation of the Ohio Community Collaboration Model in One Urban School District: A Mixed-Method Case Study. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk JESPAR. 2016;21:190–204. doi: 10.1080/10824669.2016.1183429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atkins M.S., Frazier S.L., Leathers S.J., Graczyk P.A., Talbott E., Jakobsons L., Adil J.A., Marinez-Lora A., Demirtas H., Gibbons R.B., et al. Teacher Key Opinion Leaders and Mental Health Consultation in Low-Income Urban Schools. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008;76:905–908. doi: 10.1037/a0013036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Axberg U., Hansson K., Broberg A.G., Wirtberg I. The Development of a Systemic School-Based Intervention: Marte Meo and Coordination Meetings. Fam. Process. 2006;45:375–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baxendale J., Lockton E., Adams C., Gaile J. Parent and Teacher Perceptions of Participation and Outcomes in an Intensive Communication Intervention for Children with Pragmatic Language Impairment. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2013;48:41–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bellinger S.A., Lee S.W., Jamison T.R., Reese R.M., Bellinger S.A., Lee S.W., Jamison T.R., Reese R.M., Bellinger S.A., Lee S.W., et al. Conjoint Behavioral Consultation: Community-School Collaboration and Behavioral Outcomes Using Multiple Baseline Conjoint Behavioral Consultation: Community-School Baseline. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2016;26:139–165. doi: 10.1080/10474412.2015.1089405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhatara V.S., Vogt H.B., Patrick S. Acceptability of a Web-based Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Scale (T-SKAMP) by Teachers: A Pilot Study. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2006;19:195–200. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bruns E.J., Walrath C., Glass-Siegel M., Weist M.D. School-based mental health services in Baltimore: Association with school climate and special education referrals. Behav. Modif. 2004;28:491–512. doi: 10.1177/0145445503259524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Capp G. Our Community, Our Schools: A Case Study of Program Design for School-Based Mental Health Services. Child. Sch. 2015;37:241–248. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdv030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clarke M., Coombs C., Walton L. School Based Early Identi¢cation and Intervention Service for Adolescents: A Psychology and School Nurse Partnership Model. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health. 2003;8:34–39. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fazel M., Doll H., Stein A. A school-based mental health intervention for refugee children: An exploratory study. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2009;14:297–309. doi: 10.1177/1359104508100128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fiester L., Nathanson S. Healing Fractured Lives: How Three School-Based Projects Approach Violence Prevention and Mental Health Care. [(accessed on 10 February 2022)];1996 Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED408542.pdf.

- 53.Foy J.M., Earls M.F. A Process for Developing Community Consensus Regarding the Diagnosis and Management of Attention- Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Pediatrics. 2005;17:84–97. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goodwin T., Pacey K., Grace M. Childreach: Violence Prevention in Preschool Settings. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2003;16:55–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2003.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hunter A., Playle J., Sanchez P., Cahill J. Introduction of a child and adolescent mental health link worker: Education and health staff focus. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2008;15:670–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jaatinen P.T., Erkolahti R., Asikainen P. Networking family counselling services. Developing psychosocial support for school children. J. Interprof. Care. 2005;19:294–295. doi: 10.1080/13561820500138644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jennings J., Pearson G., Harris M. Implementing and Maintaining School-Based Mental Health Services in a large, Urban School District. J. Sch. Health. 2000;70:201–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb06473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Juszczak L., Melinkovich P., Kaplan D. Use of health and mental health services by adolescents across multiple delivery sites. J. Adolesc. Health. 2003;32:108–118. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]