Abstract

This cross-sectional study uses data from the 2014-2018 National Health Interview Survey to examine various characteristics of US cancer survivors who experience delays in care due to transportation barriers.

In 2019, there were 16.9 million cancer survivors in the US; prevalence is projected to reach 22.1 million by 2031.1 Cancer survivors have increased health care needs, given their elevated risk of comorbid illnesses and subsequent cancers,2 and timely access to care is critical to optimize health outcomes. Transportation barriers can impede timely access and treatment adherence.3 Nevertheless, little is known about delays in care due to transportation barriers affecting survivors. To inform future interventions, this cross-sectional study assessed self-reported transportation barriers among cancer survivors and the general population and examined correlates of transportation barriers among survivors.

Methods

Adults 18 years or older with (n = 11 586) and without (n = 136 609) a cancer history were identified from the 2014-2018 National Health Interview Survey, a nationally representative, well-validated cross-sectional survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized US population.4 Race and ethnicity were self-reported. The survey includes the in-person interview question “Have you delayed getting care in the past 12 months because you did not have transportation?” Transportation barriers were compared between survivors and adults without a cancer history, stratified by age group (18-64 and ≥65 years). Separate multivariable logistic regression analyses assessed correlates of delays in care due to transportation barriers among cancer survivors by age group. Potential correlates were selected based on a priori knowledge of associations among sociodemographic factors, health and health care–related factors, and transportation barriers to care. All analyses were performed from May 1 to November 1, 2021, and used SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) to account for complex survey design and nonresponse. Statistical significance testing was 2-sided at P < .05. Institutional review board review was exempted by the Office of Research Subject Protection at the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, New York, because the study used deidentified data. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Results

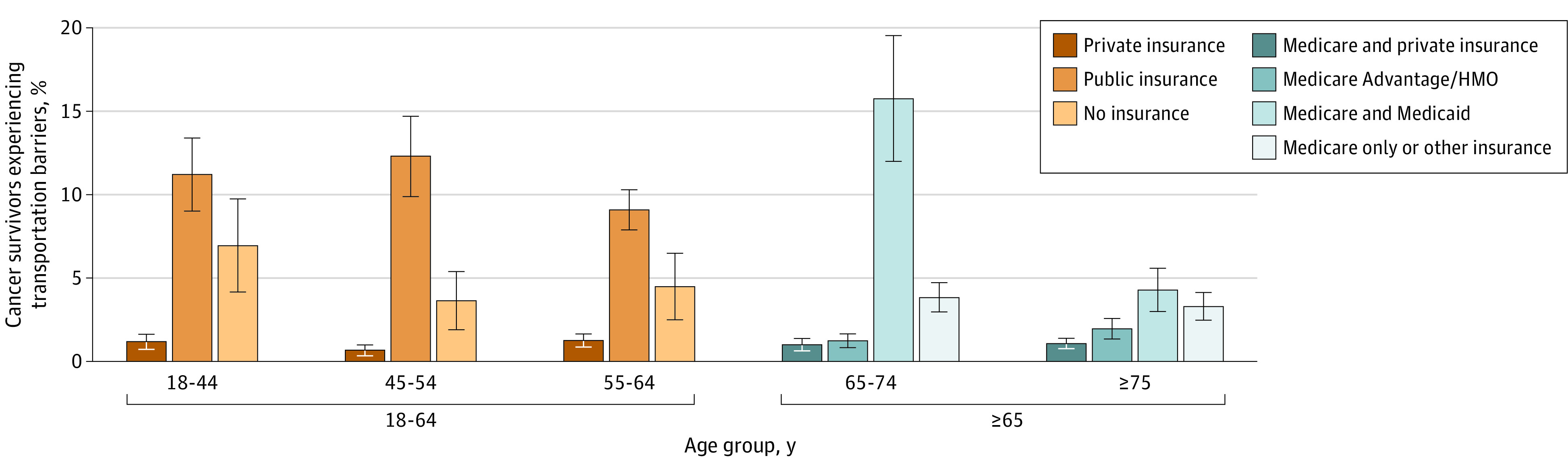

Among the 148 195 survey respondents, mean (SD) age was 49.9 (18.3) years, 81 706 (52.0%) were women, 66 489 (48.0%) were men. Cancer survivors were more likely to report delays in care due to transportation barriers in the preceding 12 months than adults without a cancer history (3.1% vs 1.8%), representing approximately 476 000 cancer survivors in 2018 based on survey weight. Younger survivors reported more transportation barriers than their cancer-free peers, whereas elderly respondents faced similar transportation burden regardless of cancer history. In adjusted analyses, cancer survivors who were younger, poor, uninsured, or publicly insured (Figure), unmarried, or with self-reported physical functional limitations were more likely to experience transportation barriers (Table).

Figure. Proportion of Cancer Survivors With Transportation Barriers, Grouped by Age and Insurance Status.

Public insurance included Medicare, Medicaid, State Children's Health Insurance Program, and other public hospital or physician coverage. Public insurance comprised people younger than 65 years who had at least 1 type of public coverage and did not have private coverage; Medicare and private insurance, those 65 years or older who had Medicare and private insurance coverage and did not have Medicare Advantage or any health maintenance organization (HMO) insurance; Medicare Advantage/HMO, those 65 years or older who had Medicare Advantage or any HMO insurance and did not have Medicaid coverage; Medicare and Medicaid, those 65 years or older who had both Medicare and Medicaid coverage; and Medicare only or other, those 65 years or older who had Medicare only or at least 1 other type of public coverage except for Medicaid or no coverage. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Table. Adjusted ORs of Transportation Barriers for Strata of Clinical and Sociodemographic Characteristics Among Cancer Survivors, 2014-2018 National Health Interview Survey.

| Characteristic | Aged 18-64 y (n = 4754) | Aged ≥65 y (n = 6832) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted % | OR (95%CI)a | Weighted % | OR (95%CI)a | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18-44 | 24.7 | 1.85 (1.05-3.26) | ||

| 45-54 | 26.3 | 1.12 (0.69-1.81) | ||

| 55-64 | 49.1 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 65-74 | 50.7 | 1.83 (1.22-2.75) | ||

| ≥75 | 49.3 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 65.6 | 1.77 (1.06-2.96) | 54.3 | 1.49 (0.76-2.94) |

| Male | 34.4 | 1 [Reference] | 45.7 | 1 [Reference] |

| Race and ethnicityb | ||||

| Asian and other | 4.3 | 0.94 (0.27-3.28) | 3.6 | 0.67 (0.26-1.70) |

| Hispanic | 9.4 | 1.49 (0.82-2.70) | 5.5 | 0.65 (0.28-1.52) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 8.8 | 1.22 (0.66-2.24) | 8.1 | 1.55 (0.84-2.87) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 77.5 | 1 [Reference] | 82.8 | 1 [Reference] |

| Educational level | ||||

| <High school | 10.6 | 1 [Reference] | 14.0 | 1 [Reference] |

| High school graduate | 23.9 | 0.92 (0.54-1.57) | 28.2 | 1.02 (0.58-1.82) |

| >High school | 65.6 | 1.17 (0.72-1.88) | 57.7 | 1.03 (0.59-1.80) |

| Married | ||||

| Yes | 59.2 | 1 [Reference] | 57.2 | 1 [Reference] |

| No | 40.8 | 2.55 (1.61-4.04) | 42.8 | 1.99 (1.19-3.31) |

| Employed | ||||

| Yes | 54.6 | 1 [Reference] | 12.1 | 1 [Reference] |

| No | 45.4 | 2.17 (1.24-3.81) | 87.9 | 3.31 (1.00-10.96) |

| Insurancec | ||||

| Aged ≤64 y | ||||

| Private insurance | 67.7 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Public insurance | 24.9 | 2.38 (1.30-4.36) | ||

| Uninsured | 7.4 | 1.90 (0.91-3.98) | ||

| Aged ≥65 y | ||||

| Medicare and private (except private HMOs) | 45.6 | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Medicare Advantage/HMO | 23.5 | 1.31 (0.73-2.35) | ||

| Medicare and Medicaid | 6.7 | 2.77 (1.44-5.32) | ||

| Medicare only or other | 24.2 | 2.63 (1.53-4.53) | ||

| Household income as a percentage of the FPL, % | ||||

| <100 | 12.8 | 3.76 (1.54-9.18) | 6.1 | 4.94 (2.22-10.98) |

| 100-199 | 14.4 | 2.67 (1.11-6.39) | 17.2 | 2.51 (1.21-5.19) |

| 200-399 | 24.6 | 1.60 (0.65-3.96) | 30.8 | 2.50 (1.16-5.36) |

| ≥400 | 42.5 | 1 [Reference] | 35.5 | 1 [Reference] |

| Unknown | 5.7 | 0.46 (0.10-2.04) | 10.3 | 1.23 (0.42-3.60) |

| Any functional limitationd | ||||

| No | 42.5 | 1 [Reference] | 27.5 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 57.5 | 3.00 (1.45-6.20) | 72.5 | 5.23 (2.20-12.41) |

| No. of comorbid illnessese | ||||

| 0 | 37.3 | 1 [Reference] | 14.1 | 1 [Reference] |

| 1-2 | 44.5 | 3.29 (1.67-6.47) | 56.6 | 2.68 (1.16-6.19) |

| ≥3 | 18.2 | 3.90 (1.91-7.96) | 29.3 | 4.23 (1.83-9.75) |

| Time since cancer diagnosis, y | ||||

| <2 | 23.3 | 1 [Reference] | 17.2 | 1 [Reference] |

| 2-5 | 26.5 | 0.61 (0.33-1.14) | 20.5 | 0.62 (0.34-1.13) |

| 6-10 | 20.1 | 0.70 (0.34-1.45) | 20.4 | 0.66 (0.32-1.35) |

| 11-15 | 12.1 | 1.14 (0.54-2.40) | 14.2 | 1.10 (0.54-2.27) |

| ≥16 | 18.1 | 1.13 (0.59-2.16) | 27.8 | 1.11 (0.59-2.11) |

Abbreviations: FPL, federal poverty level; HMO, Health Maintenance Organization; OR, odds ratio.

Adjusted ORs were derived using 2 separate multivariable logistic regression models for cancer survivors aged 18 to 64 years and 65 years or older, after adjustment for survey year, age, sex, race and ethnicity, educational level, marital status, employment status, insurance, household income level, region, functional limitation, comorbid illness, any routine primary care physician, time since cancer diagnosis, and cancer type.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported. Options included Asian, Black, Hispanic, White, and Other (Alaska Native, American Indian, Non-Hispanic Pacific Islander, primary race not releasable [confidentiality reason], and multiple race [no primary race identified]).

The various categories of insurance coverage are described in the Figure legend.

Functional limitations included any self-reported limitation in walking a quarter of a mile, walking up 10 steps without resting, standing or sitting for 2 hours, stooping, reaching up overhead, carrying 10 pounds (4.5 kg), pushing large objects such as a living room chair, shopping, or visiting friends.

Comorbid illnesses included hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery diseases, stroke, chronic obstructive lung diseases, kidney disease, liver diseases, arthritis, and morbid obesity.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, transportation barriers to care were disproportionately reported by cancer survivors, especially working-age survivors (generally <65 years). Delays in care due to transportation barriers were more prevalent among survivors who were poor, underinsured, unmarried, or with self-reported physical functional limitations. Evaluation of the associations of transportation barriers and health outcomes will be important in future research.

A recent study5 found use of ride-sharing as nonemergency medical transportation (NEMT) significantly decreased wait times and average per-ride costs but failed to decrease missed primary care appointments. More comprehensive approaches are needed for early identification and mitigation of transportation barriers to care, with involvement of all potential stakeholders (eg, patients and their families, physicians, nurses, social workers, payers) and consideration of related systemic barriers (eg, financial hardships, food or housing insecurity). Telemedicine may also alleviate some transportation burdens.

Despite Medicaid’s mandated NEMT coverage, cancer survivors younger than 65 years with public insurance (primarily Medicaid) were as likely, if not more likely, to report transportation barriers than uninsured survivors. This may reflect lack of awareness of the Medicaid NEMT program or accessibility issues (eg, preauthorization requirements, limited trip mileage)6 and higher prevalence of other social needs among Medicaid beneficiaries. Study limitations include potential recall error of self-reported data, survival bias from a selected group of cancer survivors, the small number of short-term cancer survivors (ie, those who survived <2 years after diagnosis), and lack of information on details of delayed care or if cancer survivors forgo care altogether. Efforts to study, screen for, and reduce transportation barriers are warranted for these vulnerable cancer survivors.

Reference

- 1.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363-385. doi: 10.3322/caac.21565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang C, Deng L, Karr MA, et al. Chronic comorbid conditions among adult cancer survivors in the United States: Results from the National Health Interview Survey, 2002-2018. Cancer. 2022;128(4):828-838. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Samet JM. Determinants of cancer therapy in elderly patients. Cancer. 1993;72(2):594-601. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Center for Health Statistics . National Health Interview Survey, 2018: public-use data file and documentation. 2019 ed. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

- 5.Chaiyachati KH, Hubbard RA, Yeager A, et al. Association of rideshare-based transportation services and missed primary care appointments: a clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):383-389. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buderi K, Pervin A. Mandated Report on Non-emergency Medical Transportation. Medicaid & CHIP Payment & Access Commission (MACPAC); 2021. Accessed October 1, 2021. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Mandated-Report-on-Non-Emergency-Medical-Transportation-Further-Findings.pdf