Abstract

Background

Asthma is characterised by chronic inflammation of the airways and recurrent exacerbations with wheezing, chest tightness and cough. Treatment with inhaled steroids and bronchodilators often results in good control of symptoms, prevention of further morbidity and mortality and improved quality of life. Several steroids and beta2‐agonists (long‐ and short‐acting) as well as combinations of these treatments are available in a single inhaler to be used once or twice a day, with a separate inhaler for relief of symptoms when needed (for patients in Step three or higher, according to Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines). Budesonide/formoterol is also licenced for use as maintenance and reliever therapy from a single inhaler (SiT; sometimes referred to as SMART therapy). SiT can be prescribed at a lower dose than other combination therapy because of the additional steroid doses being received as reliever therapy. It has been suggested that using SiT improves compliance and hence reduces symptoms and exacerbations, but it is unclear whether it increases side effects associated with the use of inhaled steroids.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler (SiT) to be used for both maintenance and reliever therapy in asthma in comparison with maintenance treatment provided through combination inhalers with a higher maintenance steroid dose (either fluticasone/salmeterol or budesonide/formoterol), along with additional fast‐acting beta2‐agonists for relief of symptoms.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials, online trial registries and drug company websites. The most recent search was conducted in November 2013.

Selection criteria

We included parallel‐group, randomised controlled trials of at least 12 weeks' duration. Studies were included if they compared single‐inhaler therapy with budesonide/formoterol (SiT) versus combination inhalers at a higher maintenance dose of steroids than was given in the SiT arm (either salmeterol/fluticasone or budesonide/formoterol).

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methods expected by The Cochrane Collaboration. Primary outcomes were exacerbations requiring hospitalisation, exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids and serious adverse events (including mortality).

Main results

Four studies randomly assigning 9130 people with asthma were included; two were six‐month double‐blind studies, and two were 12‐month open‐label studies. No trials included children younger than age 12. Trials included more women than men, with mean age ranging from 38 to 45, and mean baseline steroid dose (inhaled beclomethasone (BDP) equivalent) from 636 to 888 μg. Mean baseline forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) percentage predicted was between 70% and 73% in three of the trials, and 96% in another. All studies were funded by AstraZeneca and were generally free from methodological biases, although the two open‐label studies were rated as having high risk for blinding, and some evidence of selective outcome reporting was found. These possible sources of bias did not lead us to downgrade the quality of the evidence. The quantity of inhaled steroids, including puffs taken for relief from symptoms, was consistently lower for SiT than for the comparison groups.

Separate data for exacerbations leading to hospitalisations, to emergency room (ER) visits or to a course of oral steroids could not be obtained. Compared with higher fixed‐dose combination inhalers, fewer people using SiT had exacerbations requiring hospitalisation or a visit to the ER (odds ratio (OR) 0.72, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.57 to 0.90; I2 = 0%, P = 0.66), and fewer had exacerbations requiring a course of oral corticosteroids (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.87; I2 = 0%, P = 0.82). This translates to one less person admitted to hospital or visiting the ER (95% CI 0 to 2 fewer) and two fewer people needing oral steroids (95% CI 1 to 3 fewer) compared with fixed‐dose combination treatment with a short‐acting beta‐agonist (SABA) reliever (per 100 treated over eight months). No statistical heterogeneity was observed in either outcome, and the evidence was rated of high quality. Although issues with blinding were evident in two of the studies, and one study recruited a less severe population, sensitivity analyses did not change the main results, so quality was not downgraded.

We could not rule out the possibility that SiT increased rates of serious adverse events (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.13; I2 = 0%, P = 0.98; moderate‐quality evidence, downgraded owing to imprecision).

We were unable to say whether SiT improved results for several secondary outcomes (morning and evening peak expiratory flow (PEF), rescue medication use, symptoms scales), and in cases where results were significant, the effect sizes were not considered clinically meaningful (predose FEV1, nocturnal awakenings and quality of life).

Authors' conclusions

SiT reduces the number of people having asthma exacerbations requiring oral steroids and the number requiring hospitalisation or an ER visit compared with fixed‐dose combination inhalers. Evidence for serious adverse events was unclear. The mean daily dose of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in SiT, including the total dose administered with reliever use, was always lower than that of the other combination groups. This suggests that the flexibility in steroid administration that is possible with SiT might be more effective than a standard fixed‐dose combination by increasing the dose only when needed and keeping it low during stable stages of the disease. Data for hospitalisations alone could not be obtained, and no studies have yet addressed this question in children younger than age 12.

Keywords: Adolescent, Adult, Female, Humans, Male, Anti‐Asthmatic Agents, Anti‐Asthmatic Agents/administration & dosage, Asthma, Asthma/drug therapy, Bronchodilator Agents, Bronchodilator Agents/administration & dosage, Budesonide, Budesonide/administration & dosage, Drug Combinations, Ethanolamines, Ethanolamines/administration & dosage, Formoterol Fumarate, Maintenance Chemotherapy, Maintenance Chemotherapy/methods, Nebulizers and Vaporizers, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

For people with chronic asthma, is a single combination inhaler for both regular and "as‐needed" treatment better than two separate inhalers?

Background for the review Asthma is a chronic inflammation of the airways that causes flare‐ups of wheezing, chest tightness and coughing. Treatment with inhaled steroids and other inhaled drugs that relax the airways (bronchodilators) often gives good control of symptoms, prevents serious flare‐ups and improves quality of life. Several steroids and bronchodilators (long‐ and short‐acting) as well as combinations of these treatments are available in a single inhaler.

This review focusses on a particular inhaled therapy called 'single‐inhaler therapy' (SiT), sometimes called SMART therapy. The idea is that the SiT is taken once or twice a day and also anytime it is needed for relief of symptoms. In theory, this improves compliance, controls asthma symptoms and prevents exacerbations while allowing lower overall exposure to inhaled steroids. The drugs contained in SiT are budesonide and formoterol.

This review aimed to find out whether SiT is as safe and effective as a combination inhaler (containing a steroid and a long‐acting beta‐agonist (LABA)) plus another inhaler for relief of symptoms. The review looked at the effects of these treatments for adults and children with chronic asthma.

What did we find? Four studies including 9130 adults and adolescents were included. None of the studies included children younger than age 12. The studies lasted for six months to a year, and all were funded by one drug company. Studies included more women than men, with average age of about 40. Three studies recruited people with quite similar symptoms, but one study included people with less severe asthma. The studies were well conducted, although two did not hide which treatments were being taken (known as blinding), which might have affected the results. The amount of inhaled steroids, including puffs taken for relief from symptoms, was consistently lower for SiT than for the comparison groups using two types of inhalers. Overall, we believe that the quality of the evidence was high to moderate.

Main findings Fewer people taking SiT had flare‐ups that needed a hospital stay or a visit to the ER (one fewer per 100 treated than in the control group, 95% CI 0 to 2 fewer) or a course of oral steroids (two fewer per 100 treated, 95% CI one to three fewer). If more studies are published, it is unlikely that our opinions on these main findings will change. However, we could not tell whether one treatment caused more serious adverse events than the other.

Other findings SiT had a small benefit on one measure of lung function (predose forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)). However, for several other measures, not enough information was available to show which treatment was better (amount of medication taken on an 'as needed' basis, various symptom measures and quality of life).

In conclusion, SiT reduces the need for a hospital stay or an ER visit and for courses of oral steroids for asthma flare‐ups. SiT did not increase the quantity of inhaled steroids taken overall, and it was unclear whether it increases or decreases serious side effects. Currently no data are available for the use of SiT in children younger than age 12.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. SiT for maintenance/relief compared with higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA for chronic asthma in adults and children.

| SIT for maintenance/relief compared with ICS/LABA combination at a higher fixed dose + SABA for chronic asthma in adults and children | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Studies recruited adults and adolescents aged 12 and older with chronic asthma

Intervention: SiT for maintenance and relief

Comparison: higher‐dose ICS/LABA as maintenance + SABA as relief Setting: community | ||||||

|

Outcomes Follow‐up calculated as weighted means, with range |

Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Overall heterogeneity and subgroup differences (ICS/LABA combination in control group) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Higher‐dose ICS/LABA+ SABA | SiT for maintenance/relief | |||||

| People with exacerbations requiring hospitalisation | No data | No data | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | AstraZeneca could not provide data for hospitalisations separate to ER visits |

| Patients with exacerbations requiring oral steroids Follow‐up: eight months (six to 12) | 10 per 100 |

Eight per 100 (seven to nine) |

OR 0.75 (0.65 to 0.87) |

9096 (four studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | I2 = 0%; P value 0.82 Subgroup differences (P value 0.45) |

| Patients with serious adverse events Follow‐up: eight months (six to 12) | Four per 100 | Four per 100 (three to five) | OR 0.92 (0.74 to 1.13) | 9130 (four studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | I2 = 0%; P value 0.98 Subgroup differences (P value 0.88) |

| Patients with severe exacerbations (requiring hospitalisation or ER visit) Follow‐up: eight months (six to 12) | Five per 100 | Four per 100 (three to five) | OR 0.72 (0.57 to 0.90) | 7768 (three studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | I2 = 0%; P value 0.66 Subgroup differences (P value 0.21) |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; ICS/LABA: inhaled corticosteroid/long‐acting beta2‐agonist combination inhaler; SABA: short‐acting beta2‐agonist; SiT: single‐inhaler therapy with budesonide/formoterol inhaler. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1. Wide confidence intervals, downgraded once for imprecision.

Although issues with blinding were noted in two of the studies, and one study recruited a less severe population, sensitivity analyses did not change the main results, so outcomes were not downgraded.

Background

Description of the condition

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways in which many cells and cellular elements play a role (GINA 2012). An unequivocal clinical definition of asthma has not been determined, although it is postulated that in all forms of asthma, chronic inflammation is associated with bronchial hyperresponsiveness, leading to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, cough and chest tightness, especially during the night and early in the morning. Wide variations in age of onset, symptoms, triggers, association with allergic disease and type of inflammatory cell infiltrate have been seen in patients diagnosed with asthma, underlying the probable existence of more than one pathophysiological process. Patients with all forms and severity of disease typically have intermittent symptoms of cough, wheeze and/or breathlessness. Underlying these symptoms is a process of variable and at least partially reversible airway obstruction, airway hyperresponsiveness and (with the possible exception of solely exercise‐induced asthma) chronic inflammation.

Description of the intervention

Single‐inhaler therapy (SiT)

Asthma therapy is based on modulation of airways inflammation, which is the main cause of symptoms and exacerbations. This is not necessary for people with very mild and intermittent asthma, as symptoms can be well controlled with a short‐acting beta2‐agonist (SABA) as relief (Step one; GINA 2012). People with persistent asthma can use preventer therapy (usually low‐dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)) to maintain symptom control, improve lung function and reduce the need for emergency care by modulating airways inflammation (Step two; GINA 2012). Combination therapy with a long‐acting beta2‐agonist (LABA) and ICS is regularly used to maintain control in patients with persistent/chronic asthma not achieving good control of symptoms and exacerbations with low‐dose ICS alone, and it is often used with an additional short‐acting inhaler when needed (Step three; GINA 2012). Some people might need a medium to high dose of ICS combined with LABA (Step four; GINA 2012). This step‐wise approach allows practitioners to tailor the use of ICS and combinations to the severity of asthma in different patients, thereby avoiding excessive exposure to steroids and their long‐term side effects (GINA 2012). One particular combination inhaler containing budesonide (ICS) and formoterol (LABA) has the potential to be used for both maintenance and reliever therapy; this enables patients and doctors to increase the dose of both medications simultaneously, with some flexibility when asthma symptoms worsen. This is known as single‐inhaler therapy (SiT), or SMART therapy—referred to as SiT throughout this review. SiT can be prescribed at a lower dose than other ICS/LABA combination therapy because of the additional ICS being received as reliever therapy. This might allow asthma symptoms to be controlled and exacerbations to be prevented with lower overall exposure to inhaled steroids. It has been suggested that using one inhaler in this way for both maintenance and reliever therapy could also be more effective by improving compliance, but it is unclear whether it increases side effects associated with the use of inhaled steroids.

Combination therapy with separate short‐acting bronchodilator

The two commonly used combination inhalers are budesonide and formoterol, and fluticasone and salmeterol. The LABA, salmeterol, has a relatively slow onset of bronchodilation (Palmqvist 2001), and it is not licenced for use on an 'as‐needed' basis; this means that salmeterol and fluticasone can be used only for maintenance therapy, and a separate SABA is needed for additional symptom relief. Reliever medication with SABAs such as salbutamol and terbutaline, or formoterol (a fast‐acting but longer‐lasting formulation), is licenced for this purpose (BTS/SIGN 2012). Budesonide and formoterol combinations can be used alongside SABAs in this way.

How the intervention might work

The combination of ICS and LABA in a single inhaler is an effective way of delivering maintenance anti‐inflammatory and bronchodilator therapy in chronic asthma (Greenstone 2005; Ni Chroinin 2005). The anti‐inflammatory properties of the ICS and the bronchodilatory effect of the LABA play complementary roles in reducing inflammation in the airways and improving lung function with relief of symptoms related to bronchospasm (Adams 2008; Walters 2007). Both are recommended when low‐dose ICS alone is not sufficient to control asthma, which is stated at Step three in the British asthma guidelines (BTS/SIGN 2012). Concerns have been raised about the use of single‐inhaler LABA in chronic asthma, in particular when it is used without a regular ICS, in relation to the possible increased risk of severe adverse events and asthma‐related death (Cates 2008; Cates 2008a; Walters 2007). The flexibility in steroid administration that is possible with SiT might be more effective than a standard fixed‐dose combination, allowing steroid dose to be increased as a reliever when needed while keeping the maintenance dose low when the disease is stable.

Why it is important to do this review

It is recognised that many patients who are prescribed ICS do not continue to take the treatment in clinical practice, and combination inhalers can increase ICS use both as daily maintenance therapy with a SABA inhaler for relief (Delea 2008) and as single‐inhaler therapy (SiT) (Sovani 2008). Whilst trials that have investigated doubling the dose of ICS early in exacerbations have been disappointing (FitzGerald 2004; Harrison 2004), with SiT it is possible for the patient to automatically increase both LABA and ICS when asthma worsens and to cut down again as symptoms improve. This holds out the prospect of maintaining control of asthma and preventing exacerbations with lower overall exposure to ICS.

Concomitant delivery of ICS and LABA avoids the inadvertent use of LABA without prescribed ICS treatment, and although this method has been advocated as a new approach to asthma care (Barnes 2007), some have pointed out limitations in the current research evidence in children and adults with less severe asthma (Bisgaard 2003; Lipworth 2007).

Fixed‐dose budesonide and formoterol against maintenance treatment with salmeterol and fluticasone has already been reviewed (Lasserson 2011). Previous reviews have also assessed budesonide/formoterol as reliever therapy (with identical maintenance treatment) against other reliever therapy (Cates 2009), and SiT versus fixed‐dose maintenance ICS and current best practice (Cates 2009a; Cates 2013).

This review has identified and summarised clinical trials that compare single‐inhaler therapy for maintenance and relief with budesonide/formoterol (SiT) against maintenance treatment with combination inhalers (either salmeterol/fluticasone or budesonide/formoterol) and a SABA as relief. As SiT can be prescribed at a lower dose than other ICS/LABA combination therapy because of the additional ICS being received as reliever therapy, we decided that combination inhalers at a higher steroid maintenance dose would provide the most useful comparison.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler (SiT) to be used for both maintenance and reliever therapy in asthma in comparison with maintenance treatment provided through combination inhalers with a higher maintenance steroid dose (either fluticasone/salmeterol or budesonide/formoterol), along with additional fast‐acting beta2‐agonists for relief of symptoms.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised trials of parallel‐group design of at least 12 weeks' duration.

Types of participants

Adults and children with a diagnosis of chronic asthma. We accepted study‐defined asthma and recorded the definition of asthma used in the studies. We did not include studies conducted in an ER setting.

Types of interventions

Eligible treatment group intervention

Any dose of combined budesonide and formoterol delivered through a single inhaler for maintenance and reliever therapy (SiT).

Eligible control group treatment

Combination ICS/LABA inhalers (fluticasone/salmeterol or budesonide/formoterol) at a higher maintenance steroid dose than the maintenance dose in the SiT group, with additional fast‐acting beta2‐agonist inhaler for symptom relief.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Exacerbations requiring hospitalisation.

Exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids.

Serious adverse events (including mortality and life‐threatening events).

Secondary outcomes

Severe exacerbations (composite outcome of hospitalisation/ER visit).

Diary card morning and evening peak expiratory flow (PEF, L/min).

Clinic spirometry (FEV1, mL).

Number of rescue medication puffs required per day.

Days with symptoms/symptom‐free days (%).

Nocturnal awakenings (%).

Quality of life.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials from the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials (CAGR), which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and from handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (please see Appendix 1 for further details). All records in the CAGR coded as 'asthma' were searched using the following terms:

("single inhaler" or SiT or SMART or relie* or "as need*" or as‐need* or prn or flexible or titrat*) and ((combin* or symbicort or viani) or ((budesonide or BUD) AND (formoterol or eformoterol)))

We also conducted a search of ClinicalTrials.gov. The search terms are given in Appendix 2. All databases were searched from their inception to November 2013, with no restriction on language of publication.

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We searched the manufacturer's website (AstraZeneca clinical trials database) for additional study information for studies identified through the electronic searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

After electronic literature searches were completed, two review authors independently selected articles on the basis of titles and abstracts for full‐text scrutiny. The review authors agreed on a list of articles, which were retrieved, and we subsequently assessed each study to determine whether it was a secondary publication of a primary study publication and whether the study met the entry criteria of the review.

Data extraction and management

We recorded the definition of asthma used in the studies, as well as the entry criteria. We recorded whether asthma was defined according to guidelines. We summarised baseline severity of the condition (according to international guidelines, e.g. GINA 2011; BTS/SIGN 2012), persistence of symptoms and lung function among the enrolled participants, as well as data on prestudy maintenance therapies.

We extracted the following characteristics.

Design (description of randomisation, blinding, number of study centres and locations, number of study withdrawals).

Participants (N, mean age, age range of the study, baseline lung function, % on maintenance ICS or ICS/LABA combination and average daily dose of steroid (inhaled beclomethasone (BDP) equivalent), entry criteria).

Intervention (type and dose of component ICS and LABA, control limb dosing schedule, intervention limb dose adjustment schedule, inhaler device, study duration and run‐in).

Outcomes (type of outcome analysis, outcomes analysed).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias according to recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) for the following items.

Sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and investigators.

Blinding of outcome assessors.

Loss to follow‐up.

Reporting bias.

Each potential source of bias was graded as low, high or unclear risk of bias. We also noted other sources of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed dichotomous data as odds ratios, and continuous data as mean differences or standardised mean differences.

Data for each of the outcomes considered by the review were extracted from the trial publication(s) or from correspondence with study authors or the manufacturer. Exacerbations, the primary outcome for this review, have been reported by subtype (hospitalisations, ER visits and courses of oral steroids) and as a composite outcome when the breakdowns were not given. Serious adverse events were considered together as fatal and non‐fatal events.

Unit of analysis issues

We used participants (rather than events) as the unit of analysis. Some participants suffer more than one exacerbation over the course of a study, and these events are not independent.

Dealing with missing data

The proportion of randomly assigned participants who provided data for the main outcomes has been reported and compared with the number of participants with events in each outcome category.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistical variation between combined studies was measured by the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). When this exceeded 20%, we investigated the possible causes of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to inspect funnel plots to see whether publication bias was evident if more than 10 studies had been included. When trial protocols had been published in advance, we compared the outcomes suggested in the trial protocol versus those reported for each trial.

Data synthesis

Data were combined in Review Manager 5, using a fixed‐effect mean difference (calculated as a weighted mean difference) for continuous data variables, and a fixed‐effect odds ratio for dichotomous variables. For the primary outcomes of exacerbations and serious adverse events, we have calculated absolute effects for the different levels of risk, as represented by control group event rates over a specified time period using the pooled odds ratio and its confidence interval and an online calculator (Visual Rx).

A Summary of findings table was constructed for the primary outcomes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We analysed studies that compared SiT with salmeterol/fluticasone together with those studies that compared SiT with maintenance budesonide/formoterol, and we presented both the results of each comparison group separately and the pooled result. In the case of Kuna 2007 [COMPASS], which had two intervention groups relevant to this review, we halved the number of participants in the group that served twice as the control to avoid overrepresentation. For dichotomous outcomes, we halved both the numerator and the denominator of the group that served twice, and for continuous outcomes, we halved only the number of participants. It is noted that this may have affected the power of the subgroup analyses and tests for subgroup differences, and this was considered in their interpretation.

If the search had returned data on both adult and child populations, we planned to pool the data in subgroups. Adult studies were considered as those that recruited participants from age 18 upwards, and adult and adolescent studies were considered as those that recruited participants from age 12 upwards. We considered participants in studies in which the upper age limit was 12 years as children, and in studies where the upper age limit was 18 years as children and adolescents. We aimed to perform subgroup analyses in relation to asthma severity (classified according to major international guidelines (BTS/SIGN 2012; GINA 2012) and dose equivalence of treatments used) but found that it was more appropriate to remove one study in a sensitivity analysis (see Outcomes and analysis structure in Results).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis has been conducted on the basis of risk of bias in studies and baseline severity (based on baseline use of ICS and baseline percentage predicted FEV1).

Results

Description of studies

Full details of the conduct and characteristics of each included study can be found in Characteristics of included studies, and reasons for exclusion when full texts had to be viewed are given in Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

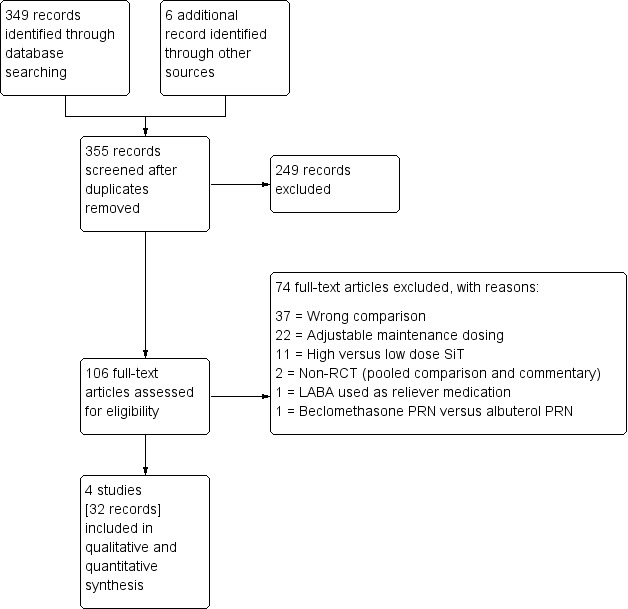

Three‐hundred fifty‐five references were identified through database searching and through additional searching of industry databases and relevant reference lists. Of these, 241 were excluded upon a sift of the titles and abstracts. One hundred six records were assessed for eligibility, of which 74 were found to not meet the review's inclusion criteria (reasons for exclusion can be found in Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Four studies (32 citations) met the inclusion criteria, randomly assigning 9130 people with a diagnosis of asthma to the comparisons of interest in this review. Kuna 2007 [COMPASS] contributed the largest sample size to the analyses, with 3335 people randomly assigned across three intervention groups. Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] included the smallest number of people, with 1343 participants randomly assigned to the two arms relevant to this review.

Design and duration

All studies were multi‐centre, randomised, parallel‐group controlled trials, taking place at between 22 and 235 centres. Two were six‐month double‐blind studies (Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD]; Kuna 2007 [COMPASS]), and two administered the medications on an open‐label basis for one year (Stallberg 2008 [SHARE]; Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]). Three studies described two‐week run‐in phases, during which participants received their usual ICS therapy (and LABA when this was part of their treatment regimen), with terbutaline as rescue medication. Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] did not describe a run‐in period.

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria

Full details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria of each trial can be found in Characteristics of included studies. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were very similar across trials. All trials included outpatients at least 12 years of age and thus were treated as adult and adolescent studies. All participants were required to have a diagnosis of persistent asthma characterised by at least one exacerbation in the 12 months before study entry. In two trials, participants' prebronchodilator FEV1 had to be greater than 50% predicted normal: One required between 40% and 90% (Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]), and the other trial did not specify (Stallberg 2008 [SHARE]). All trials recruited participants taking regular ICS therapy and in regular need of a rescue inhaler. Studies excluded participants who had recently had a respiratory infection or had recently received a course of systemic corticosteroids. Two trials stated that participants with a smoking history of greater than 10 pack‐years were excluded (Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD]; Stallberg 2008 [SHARE]). Two trials excluded participants who had been taking an ICS/LABA inhaler during the previous three (Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]) or 12 months (Stallberg 2008 [SHARE]).

Baseline characteristics of participants

Full details of the baseline characteristics of participants in each study can be found in Characteristics of included studies, and a summary in Table 2. Participants' mean age was similar across the trials, ranging from 38 to 45 years. Trials generally included more women than men (between 38% and 44% male). Participants' mean FEV1 percentage predicted was between 70% and 73% in three of the trials and was significantly higher in Stallberg 2008 [SHARE], at 96%. The mean daily dose of steroid being taken at baseline (BDP equivalent) ranged from 636 to 888 μg for individual arms within the studies.

1. Summary of study characteristics.

| Study ID | Treatment | Mean age | Age range | % Male | FEV1 % predicted | Mean baseline daily ICS (BDP) |

| Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD] | 1) SiT 2) Flut/salm |

40 39 |

12‐80 | 38 38 |

70 (range 45 to 144) 71 (range 45 to 222) |

705 (range 250 to 1600) 720 (range 200 to 2000) |

| Kuna 2007 [COMPASS] | 1) SiT 2) Flut/salm 3) Bud/form |

38 (SD 17) | 12+ | 43 43 41 |

72 73 73 |

740 (SD 240) 744 (SD 230) 750 (SD 262) |

| Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] | 1) SiT 2) Bud/form |

43 (SD 19) 45 (SD 19) |

12‐87 12‐95 |

40 44 |

95 (SD 18) 97 (SD 17) |

636 (SD 293) 650 (SD 315) |

| Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS] | 1) SiT 2) Flut/salm |

45 | 12‐80 12‐84 |

42 40 |

73 (range 39 to 115) 73 (range 28 to 100) |

888 (range 500 to 2000) 881 (range 400 to 3000) |

Where only one line of data appears in a cell, data were not available for individual trial arms but rather for the whole study population.

Characteristics of the interventions

Table 3 shows the planned daily treatment schedules and total ICS received with SiT and with the comparison interventions in each of the four studies. Kuna 2007 [COMPASS] and Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] used a daily SiT dose of 320/9 μg, and Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] also allowed the lower dose of 160/9 to be given, depending on baseline ICS use. Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD] and Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS] used the higher SiT dose of 640/18 μg per day. All studies used 160/4.5‐μg inhalations as the reliever dose in SiT. Three studies used fluticasone/salmeterol in the comparison group—two at a daily dose of 500/100 μg (ICS/LABA) (Kuna 2007 [COMPASS]; Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]), and the third at 1000/100 (Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD]). Two studies used budesonide/formoterol in the control group—Kuna 2007 [COMPASS] at a dose of 640/18 μg, and Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] at 320/18 μg or 640/18 μg, depending on baseline ICS dose. Three of the studies used terbutaline as the SABA in the control group, and Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS] used salbutamol. Although some variation between studies was noted, the planned and total received ICS doses (presented as BDP equivalents) were consistently lower in SiT.

2. Characteristics of the interventions.

| Study ID | Single‐inhaler therapy (budesonide/formoterol) | Comparison ICS/LABA total planned daily dose | ||

| Planned daily maintenance schedule (with reliever dose) | Total ICS received per day (mean, BDP μg) | Planned daily maintenance schedule (with reliever) | Total ICS received per day (mean, BDP μg) | |

| Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD] | 640/18 μg (160/4.5 as needed) | 1238 | Flut/salm 1000/100 μg (terbutaline) | 2000 |

| Kuna 2007 [COMPASS] | 320/9 μg (160/4.5 as needed) | 755 | Flut/salm 500/100 μg (terbutaline) | 1000 |

| Bud/form 640/18 μg (terbutaline) | 1000 | |||

| Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] | 320/9 or 160/9 μg based on previous ICS use (160/4.5 or 80/4.5 as needed) |

454 | Bud/form 640/18 or 320/18 μg (terbutaline) | 574 |

| Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS] | 640/18 μg (160/4.5 as needed) | 1019 | Flut/salm 500/100 μg (salbutamol) | 1166 |

Outcomes and analysis structure

All but one of the studies reported the number of people with exacerbations requiring hospitalisation or an ER visit, but these data could not be used for the primary hospitalisation outcome, as there was no way of knowing how many people had experienced hospitalisation and how many had been to the ER (or both). AstraZeneca, the drug company that funded all of the included studies, was unable to provide data for hospitalisations alone, so no data could be analysed for this primary outcome. All studies reported serious adverse events that could be meta‐analysed. Exacerbations and adverse events were coded by study investigators, who were aware of allocation in Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] and Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]. Studies did not routinely report as a separate outcome the number of people requiring a course of oral steroids , but these data were sought from the pharmaceutical company sponsoring the studies and owning the data (AstraZeneca) and are presented in Analysis 1.1. The data for hospitalisations and ER visits combined are reported under the heading 'Severe exacerbations' in Analysis 1.3.

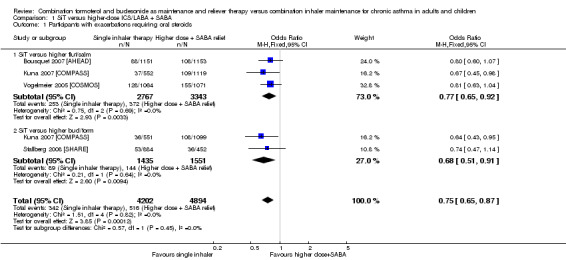

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA, Outcome 1 Participants with exacerbations requiring oral steroids.

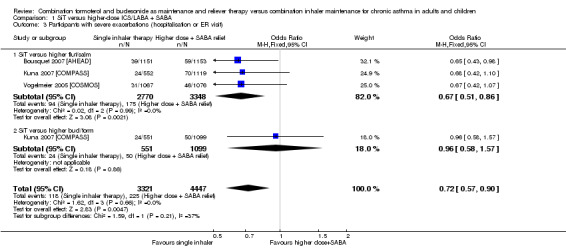

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA, Outcome 3 Participants with severe exacerbations (hospitalisation or ER visit).

Secondary outcomes were generally poorly reported. Morning and evening PEF, symptom‐free days and nocturnal awakenings were reported by only two studies (Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD]; Kuna 2007 [COMPASS]), representing three comparisons in each outcome. The same two studies also reported rescue medication use, and additional data were provided upon request by AstraZeneca for Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]. Two studies reported predose FEV1 (Kuna 2007 [COMPASS]; Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]), and these data for Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] were provided by AstraZeneca. Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD] and Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS] reported symptoms as measured by the Asthma Control Questionnnaire (ACQ)‐5, meaning that no data were available on the use of budesonide/formoterol by the control group. Only Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS] reported a measure of quality of life that could be analysed.

Meta‐analyses compared SiT versus combination inhalers of a higher fixed maintenance dose and additional fast‐acting beta2‐agonists for relief. Results were subgrouped according to the ICS/LABA combination in the comparison group (i.e. fluticasone/salmeterol or budesonide/formoterol).

Although we planned to carry out subgroup analyses according to symptom severity, we decided that a sensitivity analysis excluding Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] was more appropriate. Participants in Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD], Kuna 2007 [COMPASS] and Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS] had mean baseline lung function between 70% and 75% predicted and baseline ICS use towards the top of the medium range. Participants were generally also required to have used ICS/LABA for one to three months, to have had one or more exacerbations over the last year and to have the need for reliever medication on three to five days out of seven. Conversely, although participants in Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] had comparable mean baseline ICS doses of around 650 μg budesonide in both groups, percent predicted FEV1 was much higher, at 95% and 97%,respectively.

Excluded studies

Reasons for study exclusion can be found in Characteristics of excluded studies, and associated references are provided in Excluded studies. Three studies (D589LC00001 2011 [SAKURA]; O'Byrne 2005 [STAY]; Rabe 2006 [SMILE]) were excluded at a late stage, when it became clear that the maintenance ICS dose in the control group was not higher than the maintenance dose prescribed for the intervention group, and hence they did not meet the inclusion criteria.

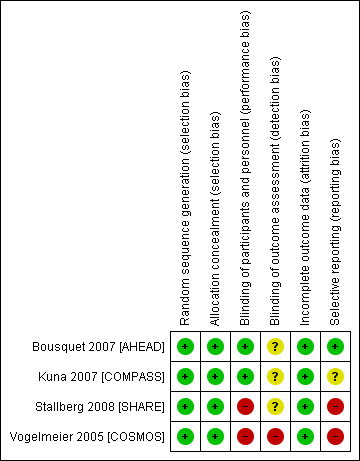

Risk of bias in included studies

For details of the risk of bias rating for each study and the reasons for each rating, see Characteristics of included studies. A summary of the risk of bias judgements by study and domain (allocation generation, allocation concealment, blinding and incomplete data) can be found in Figure 2. All studies were funded by only one pharmaceutical company (AstraZeneca) and were mostly free from methodological biases, although two studies were rated at high risk for blinding because the inhalers were delivered in an open‐label design. Evidence of selective outcome reporting was found in two of the trials, and this is reflected in the grade ratings of the affected outcomes.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

It is unlikely that selection bias compromised the validity of this review. All studies used adequate methods to allocate participants to groups and were rated as low risk of bias for sequence generation. All studies stated that randomisation codes were sequentially assigned from a list that was computer generated, and this was confirmed through communication with AstraZeneca. Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] stated that allocation was stratified according to ICS dose at baseline, and Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD] stated that randomisation occurred in balanced blocks.

All studies used adequate methods to conceal the allocation sequence until assignment and were rated as low risk of bias in this domain. Three studies (Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD]; Kuna 2007 [COMPASS]; Stallberg 2008 [SHARE]) provided individual treatment codes in sealed envelopes, and one provided allocation by means of an interactive voice response system (Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]).

Blinding

Ineffective blinding procedures may have introduced bias into the analyses in this review. Two studies used adequate double‐dummy procedures and labelling to conceal the medications from participants and providers and were rated as low risk of bias (Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD]; Kuna 2007 [COMPASS]). The other two studies used an open‐label design and therefore were at high risk of performance and detection bias by participants and investigators (Stallberg 2008 [SHARE]; Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]).

Three studies did not state whether outcome assessors were blind to treatment allocation (Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD]; Kuna 2007 [COMPASS]; Stallberg 2008 [SHARE]), so were rated as unclear. The remaining study described dose titration by investigators, who appeared to be those who rated outcomes, and hence was rated at high risk of bias (Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]).

Incomplete outcome data

Little evidence of attrition bias was found in the included studies. Withdrawal rates were low (highest 14% in the fluticasone/salmeterol group of Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]) and even between groups in all studies.

Selective reporting

Varied evidence of reporting bias was found in the four included studies, and this may have affected the robustness of some analyses. Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD] was rated as low risk of bias, as we were able to locate the trial registration and check it against the study report. Although it appeared that Kuna 2007 [COMPASS] reported all relevant outcomes, we could not locate the study protocol and hence could not confirm that all predefined outcomes were included in the published report. Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] and Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS] were rated as high risk of bias because they omitted data or did not provide it in a reasonable format for one or more of the outcomes. Although additional outcome data and information about study methodology were provided by AstraZeneca, several outcomes still did not include data from all four studies.

Other potential sources of bias

No other sources of bias were identified.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Single‐inhaler therapy (SiT) versus ICS/LABA combination inhalers at a higher ICS dose with separate SABA relief

Full details of the analyses and their GRADE ratings can be found in Data and analyses and Table 1.

Primary outcomes

Subgroup analyses based on the ICS/LABA combination in the comparison group were performed for all of the primary outcomes. No evidence of subgroup differences was found for exacerbations requiring oral steroids or serious adverse events, although splitting the SiT group in Kuna 2007 [COMPASS] may have resulted in an underestimation of subgroup differences. For full details of the individual subgroup effects, see Analysis 1.1 and Analysis 1.2. Although two of the studies were open‐label, one of which recruited a less severe population, we chose not to downgrade the evidence for these reasons based on the sensitivity analyses presented.

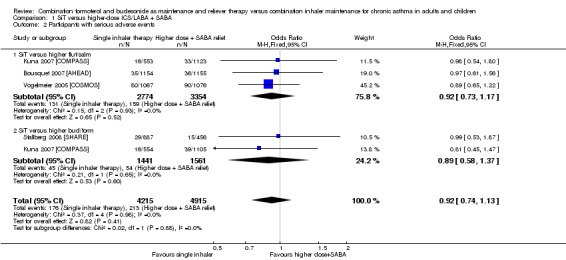

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA, Outcome 2 Participants with serious adverse events.

Exacerbations requiring hospitalisation

All but one of the studies reported the number of people with exacerbations requiring hospitalisation or an ER visit, but these data could not be used, as there was no way of knowing how many people had been admitted to hospital for an exacerbation and how many had been to the ER. AstraZeneca, the drug company that funded all of the included studies, was unable to provide data related purely to hospitalisations. Available data (composite of exacerbations requiring hospitalisation or an ER visit) are shown in the secondary outcome labelled 'Severe exacerbations'.

Exacerbations requiring a course of oral corticosteroids

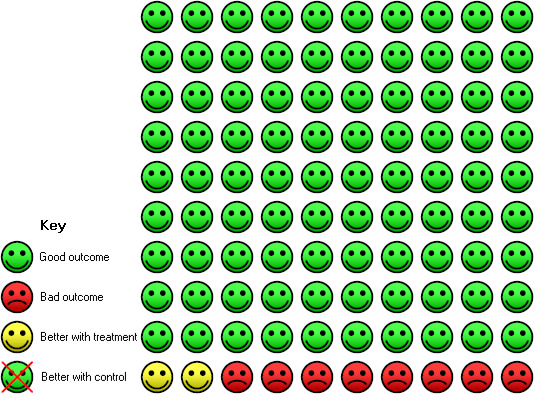

SiT reduced the number of people who had an exacerbation requiring a course of oral corticosteroids (odds ratio (OR) 0.75, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.65 to 0.87; I2 = 0%, P = 0.82). AstraZeneca provided data for 9096 people across all four studies, and the evidence was rated as high quality (no serious imprecision, inconsistency, risk of bias or indirectness). Figure 3 shows the absolute effect in a Cates plot.

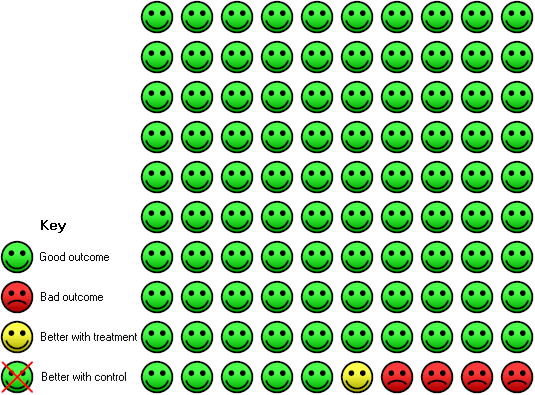

3.

Cates plot: In the control group, 10 of 100 people had an exacerbation requiring oral steroids over eight months compared with eight (95% CI seven to nine) of 100 in the SiT group.

Number of people with serious adverse events (including mortality)

We could not rule out a possible increase or decrease in serious adverse events with SiT (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.13; I² = 0%, P = 0.98), based on 9130 participants from all four trials, and no statistical heterogeneity was observed between study results. The evidence was downgraded once for imprecision and was rated as moderate quality, as the confidence intervals were wide.

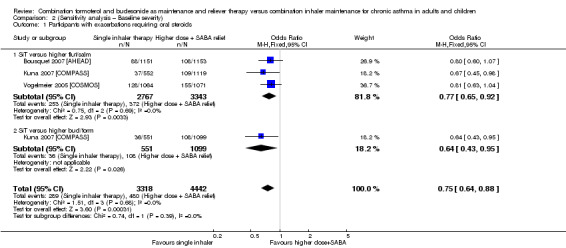

Sensitivity analysis—baseline severity

Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] was removed from the three primary outcomes in a sensitivity analysis because the population had much higher baseline percentage predicted FEV1 than that in the other studies. The study did not report exacerbations requiring hospitalisation, so this outcome was not affected. Conclusions for exacerbations requiring oral steroids (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 2.1) and serious adverse events (Analysis 1.2; Analysis 2.2) were unaffected by removing the study.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (Sensitivity analysis – Baseline severity), Outcome 1 Participants with exacerbations requiring oral steroids.

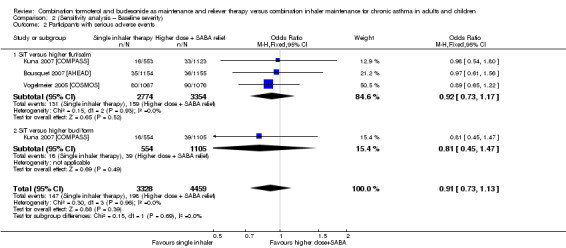

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (Sensitivity analysis – Baseline severity), Outcome 2 Participants with serious adverse events.

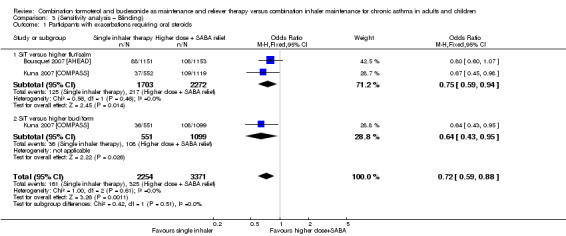

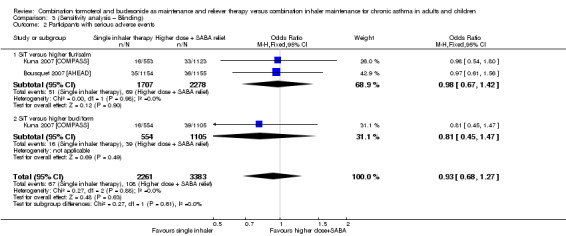

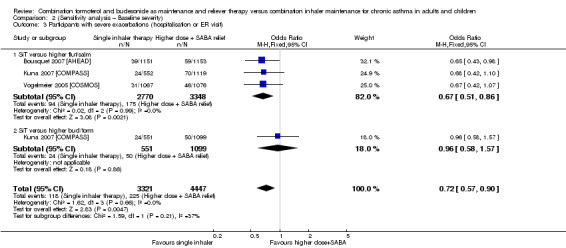

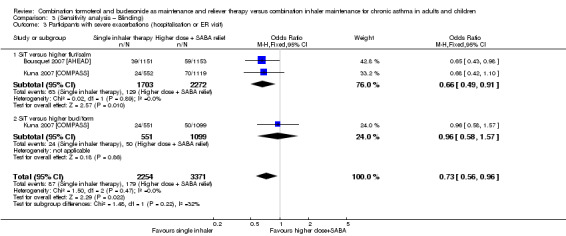

Sensitivity analysis—blinding

Stallberg 2008 [SHARE] and Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS] were removed from the primary analyses for a sensitivity analysis on the basis of performance and detection bias (Figure 2). Results were very similar with and without the studies for exacerbations requiring oral steroids (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 3.1), serious adverse events (Analysis 1.2; Analysis 3.2) and exacerbations requiring hospitalisation or an ER visit (Analysis 2.3; Analysis 3.3),

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (Sensitivity analysis – Blinding), Outcome 1 Participants with exacerbations requiring oral steroids.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (Sensitivity analysis – Blinding), Outcome 2 Participants with serious adverse events.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (Sensitivity analysis – Baseline severity), Outcome 3 Participants with severe exacerbations (hospitalisation or ER visit).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (Sensitivity analysis – Blinding), Outcome 3 Participants with severe exacerbations (hospitalisation or ER visit).

Secondary outcomes

Subgroup analyses based on the ICS/LABA combination in the comparison group were performed for all of the secondary outcomes. In all cases, no heterogeneity (I² = 0%) between subgroups was noted, so only the pooled effect is reported to increase precision. Individual subgroup effects for each outcome can be found in Data and analyses.

Severe exacerbations (those requiring hospitalisation or an ER visit)

The number of people who had at least one exacerbation meeting these criteria was lower in the SiT group (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.90; I2 = 0%, P = 0.66), based on 7768 participants from three of the studies. No heterogeneity was observed, and the evidence was rated as high quality. Figure 4 shows the absolute effect in a Cates plot.

4.

Cates plot: In the control group, five of 100 people had an exacerbation requiring hospitalisation or an ER visit over eight months, compared with four (95% CI three to five) of 100 in the SiT group.

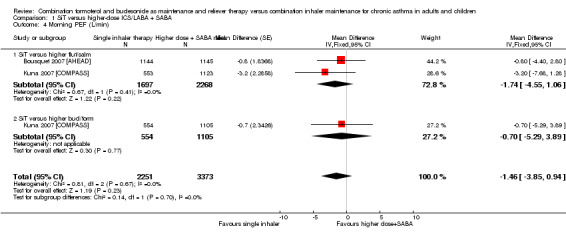

Morning peak expiratory flow (PEF, L/min)

SiT was not significantly different from higher‐dose ICS/LABA for morning PEF (mean difference (MD) ‐1.46, 95% CI ‐3.85 to 0.94; I² = 0%, P = 0.67), based on 5624 participants in two studies (three comparisons). No heterogeneity was observed between studies, and imprecision was judged to be not severe enough to warrant downgrading. However, given that two studies could not be included in the analysis, the outcome was downgraded for publication bias. The quality of this evidence was therefore rated as moderate.

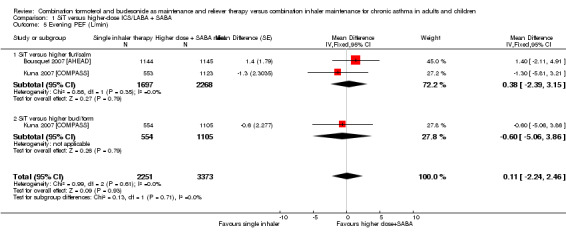

Evening peak expiratory flow (PEF, L/min)

No significant difference between SiT and the control intervention was seen for evening PEF, and the magnitude of the mean difference was smaller (MD 0.11, 95% CI ‐2.24 to 2.46; I² = 0%, P = 0.61). Again, this was based on 5624 participants in two trials, and no heterogeneity was noted between studies. The quality of evidence was rated as moderate for the same reasons as in the morning PEF analysis.

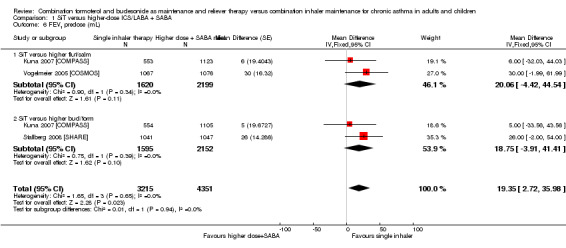

Predose forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1, mL)

SiT was associated with slightly better predose FEV1 compared with the control intervention (MD 19.35, 95% CI 2.72 to 35.98; I² = 0%, P = 0.65) with no heterogeneity. The analysis was based on 7566 participants in three trials (representing four comparisons), and the evidence was rated as moderate quality, as downgraded for imprecision because the confidence intervals included almost no benefit.

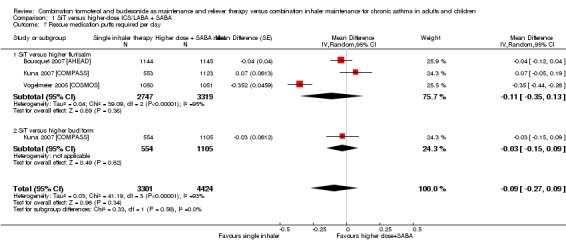

Rescue medication puffs required per day

Because of the nature of the comparison, rescue medication referred to different treatments in the intervention and control arms: In the SiT group, rescue medication is the number of additional puffs of budesonide/formoterol combination inhaler taken per day, and in the control arm, it is the number of puffs of the SABA inhaler provided as reliever medication. In each case, it captures the need for additional medication on top of regular twice‐daily maintenance treatment.

The need for rescue mediation was not statistically different between SiT and controls (MD ‐0.09, 95% CI ‐0.27 to 0.09; I² = 93%, P > 0.00001), based on 7725 participants in three trials (representing four comparisons), but considerable heterogeneity was observed between the two studies. As such, a random‐effects model was used, and the outcome was downgraded for inconsistency. The outcome was also downgraded for imprecision, and the evidence was rated as low quality.

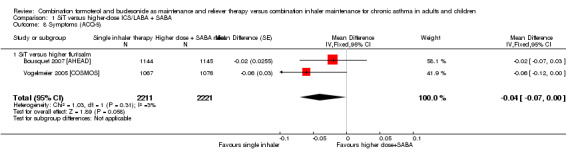

Symptoms rating—Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ‐5)

Moderate‐quality evidence suggested a small but significant improvement with SiT on the ACQ‐5 (MD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.00; I² = 3%, P = 0.31), based on 4432 participants in two studies, and very little heterogeneity was noted between studies. Both studies used fluticasone/salmeterol in the control intervention. The evidence was downgraded for publication bias, as two studies (representing three comparisons) did not report the outcome.

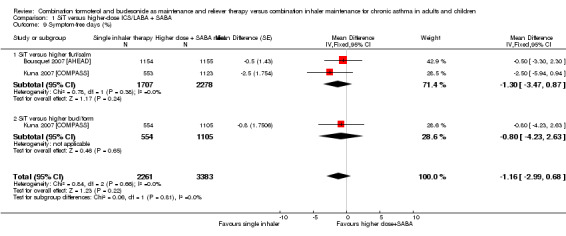

Symptom‐free days (%)

SiT was not significantly different from higher‐dose combination therapy in terms of symptom‐free days (MD ‐1.16, 95% CI ‐2.99 to 0.68; I² = 0%, P = 0.66), based on 5644 participants in two trials (representing three comparisons), and no heterogeneity was seen between the studies. The evidence was downgraded for publication bias only and was rated as moderate quality.

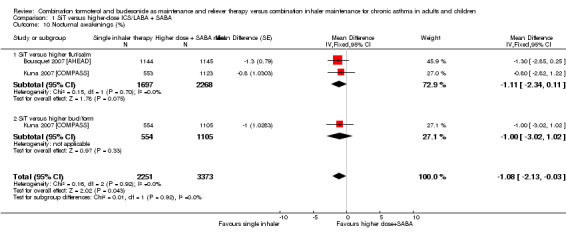

Nocturnal awakenings (%)

Nocturnal awakenings were reduced with SiT (MD ‐1.08, 95% CI ‐2.13 to ‐0.03; I² = 0%, P = 0.92), based on 5624 participants in two studies (in three comparisons). No heterogeneity was observed between the studies, although again, two studies were missing from the analysis. As such, the outcome was downgraded for publication bias and was rated as moderate quality.

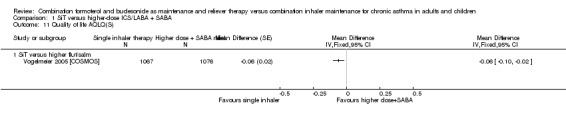

Quality of life—Asthma Quality of Life Questinnaire (AQLQ)

Evidence of very low quality suggested a small benefit of SiT compared with a higher‐dose fluticasone/salmeterol combination (MD ‐0.06, 95% CI ‐0.10 to ‐0.02). This was based on one study with 2143 participants (Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]). The outcome was downgraded for the methodological risk of bias in Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS]. As none of the other three studies reported a quality of life measure that could be included in the meta‐analysis, the evidence was downgraded twice for publication bias.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Four studies were included, randomly assigning 9130 participants with a diagnosis of persistent/chronic asthma (Step three and above; GINA 2012) to the comparisons of interest in this review. None of the studies included children younger than age 12, so we were unable to draw conclusions for this group of participants.

Meta‐analyses compared SiT versus combination inhalers at a higher dose alongside fast‐acting beta2‐agonists for relief. Results were subgrouped according to the ICS/LABA combination used in the comparison group (i.e. fluticasone/salmeterol or budesonide/formoterol), but because no significant differences were noted for the primary outcomes, we have summarised the pooled estimates. Trials included more women than men, with mean age ranging from 38 to 45 and mean baseline steroid dose (BDP equivalent) from 636 to 888 μg. Mean baseline FEV1 percentage predicted was between 70% and 73% in three of the trials, and 96% in another.

Fewer people taking SiT had an exacerbation requiring a course of oral steroids (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.87) or requiring hospitalisation or a visit to the ER (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.90). Data for hospitalisations independent from the other exacerbation criteria were not available. We could not rule out the possibility of SiT increasing or decreasing serious adverse events (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.13). No important variation was seen in the main findings, and they were mostly rated high quality (i.e. further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect).

Inconsistent reporting of secondary outcomes reduced our confidence in these findings. No significant difference was observed between SiT and higher‐dose combinations for morning PEF, evening PEF, rescue medication use or number of symptom‐free days. On three secondary outcomes for which SiT showed a statistically significant benefit, the magnitude of effect was not deemed clinically meaningful (FEV1, nocturnal awakenings and quality of life).

Sensitivity analyses to explore two potential moderators of effect (baseline severity and blinding) did not change conclusions, but differences in dose regimens and in participant characteristics are likely to have introduced some inconsistency in the findings. In addition, although all studies were funded by AstraZeneca, which provided additional data for several outcomes, methodological differences such as blinding and inclusion criteria may reduce our confidence in the results.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

None of the studies included participants younger than age 12, so the evidence can be applied only to adults and adolescents. Single‐inhaler therapy is not currently licenced for children younger than age 18, and the only study that included children did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review (O'Byrne 2005 [STAY]). In addition, no data were available for one of the primary outcomes—exacerbations leading to hospitalisation—representing an important gap in the evidence. Although exacerbations were reported in several other ways, hospitalisation is distinct from the other classifications because of the extent of associated healthcare costs and disruption for the participant.

Participants in Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD], Kuna 2007 [COMPASS] and Vogelmeier 2005 [COSMOS] had mean baseline lung function between 70% and 75% predicted and baseline ICS use towards the top of the medium range. Participants in these studies generally were required to have used LABA/ICS for one to three months, to have had one or more exacerbations in the past year and to have needed reliever medication on at least three days a week. On the basis of the sensitivity analysis to investigate changes in primary outcomes after exclusion of the one remaining study (Stallberg 2008 [SHARE]) recruiting a less severe population, it seems likely that the results of this review are applicable to patients of somewhat different severities. A degree of variation between studies was seen in the amount of ICS received, and this may be an important source of heterogeneity; in the SiT groups, the actual received steroid dose ranged from 454 to 1238 BDP equivalent, and from 574 to 2000 in the comparison groups. In the individual studies, people in the comparison group always received more ICS than those in the SiT group (using the amount of ICS from the maintenance SiT dose alone, or the amount from both maintenance and relief inhalations), but the absolute levels were highly variable among studies. The variability in doses may reflect the design of the studies and differences in baseline severity, although the sensitivity analysis excluding one study with very different inclusion criteria did not change the results. The dose differences might also reflect a certain variability in guidelines for the treatment of asthma associated with the fact that the studies were performed in different years and in different countries. For this reason, we were unable to draw conclusions about dose.

A potential issue is the generalisability of the SiT approach and results to clinical practice: All studies were conducted in a controlled manner, with regular follow‐up and specific training in the use of inhalers, and this might be difficult to reproduce in the day‐by‐day clinical work of general practitioners and even specialists. Adherence to treatment is one of the main factors limiting clinical efficacy of interventions in asthma; this is recognised and addressed in current guidelines (BTS/SIGN 2012; GINA 2012).

Another potential issue regards patients who tend to overuse their relief medications and whether the intensive instruction and management of participants in trials are representative of clinical practice. Overuse of inhalers is certainly something to consider in the clinical management of all patients with asthma, regardless of the type of device or beta2‐agonist prescribed as relief, but this is something that occurs relatively seldom nowadays, especially in patients reaching good control of their symptoms with the addition of inhaled steroids. An associated concern is the potential for overconsumption of inhaled steroids associated with single‐inhaler therapy. However, the current meta‐analysis shows in a good sample size that participants treated in the SiT arm had in fact received lower doses of inhaled steroids during and at the end of the trials, and this was associated with a reduced need for systemic steroids. The review did not look at specific adverse events related to steroid use to limit the number of outcomes; instead the review authors looked generally at the rate of more serious events. Analysing the data in this way could have masked potential differences in the rates of overall adverse events of any severity or of particular adverse events associated with ICS use.

In the light of the raised safety concerns associated with ICS+LABA therapy, critical evaluation of safety outcomes becomes very important. The title included evaluation of the safety of the combination; however, certain important issues including withdrawal overall and withdrawal due to specific reasons, adverse effects overall and specific adverse effects have not been addressed in the review. It would be great to address the issues of withdrawal as an indirect support for the primary outcome.

Quality of the evidence

Some of the results may be subject to detection and performance bias because two of the studies did not blind study medication from participants and investigators. Of these two studies, it was clear that in one, outcome assessors were also unblinded, and in the other, insufficient information was provided for review authors to judge. Similarly, use of different inhalers and techniques for the intervention and control arms in some ways precluded true blinding, and inhaler type may have introduced heterogeneity into some of the outcomes.

In addition, several of the secondary outcomes contain only one or two studies; this prevented any strong conclusions from being drawn, despite the fact that AstraZeneca provided additional data for several of the outcomes. As only four included studies were identified, missing data from even one study could have a serious affect on the analysis. For this reason, unless all four studies could be included in the analysis, the evidence was downgraded for publication bias and was rated as moderate quality at best. We did not contact individual authors for extra data but liaised directly with AstraZeneca to make every effort to include all studies in as many of the outcomes as possible.

Potential biases in the review process

We are confident that all identifiable studies were found by using additional methods to catch anything that might not have been found in the main electronic search (e.g. searching drug company databases and clinical trial registration sites, checking reference lists). However, although every effort was made to find and include unpublished data, unpublished studies (industry funded or otherwise) may exist that might change our confidence in the conclusions (Song 2010). We adhered to best practice guidelines throughout the review process in terms of study selection, resolution of disagreements, data extraction and analysis.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Several previous reviews have meta‐analysed single‐inhaler maintenance and reliever therapy versus other recommended treatment strategies (Agarwal 2009; Bateman 2011; Cates 2013; Edwards 2010). As in this review, all found that exacerbation rates were reduced with SiT compared with usual care (Cates 2013), ICS alone at equivalent or higher doses (Agarwal 2009; Cates 2013) and fixed‐dose ICS/LABA combinations (Agarwal 2009; Bateman 2011; Edwards 2010). This reinforces the validity of our findings and suggests that SiT might induce better control of inflammation in asthma, thanks to low additional doses of inhaled steroids in combination with formoterol only when really needed because of the participant's clinical condition.

Evidence regarding the benefits of SiT for hospitalisation has been mixed. This review obtained evidence that is in line with evidence reported by Agarwal 2009 and Edwards 2010, which used similar comparators. Cates 2013 did not find that SiT reduced hospitalisations, but in this review, SiT was compared with ICS alone or with current best practice. Our review demonstrates a reduction in exacerbations requiring hospitalisation or an ER visit, although we were able to analyse data for the two definitions only separately.

Czarnecka 2012 concluded that although single‐inhaler therapy reduces exacerbations, it is associated with 'poor symptom control of asthma'. This is not in line with the findings of this review or with the conclusions of other reviews, which tend to report no evidence of statistical differences in various symptom measures or spirometry compared with other treatment strategies. Although this should not be interpreted as evidence of equivalent efficacy, it suggests that evidence is insufficient to permit review authors to state the superiority of SiT or the fixed‐dose comparison for these outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This review provides evidence of high and moderate quality showing that SiT reduces exacerbations requiring hospitalisation or an ER visit and courses of oral steroids. Current evidence is insufficient to show whether SiT is associated with more or fewer serious adverse events compared with higher fixed‐dose ICS/LABA combinations, and no data were available for exacerbations leading to hospitalisation. The mean daily dose of ICS in SiT, including the total dose administered with reliever use, was always lower than that of the other combination groups. This suggests that the flexibility in steroid administration that is possible with SiT might be more effective than a standard fixed‐dose combination by increasing the dose only when needed and keeping it low during stable stages of the disease.

Implications for research.

Research into this comparison should be aimed at children and adolescents with persistent asthma, particularly children younger than age 12, for whom no evidence is currently available. Researchers should report the number of people with the most severe exacerbations—those requiring admission to hospital—as distinct from the number with exacerbations leading to systemic medications and ER visits. Future studies might consider better characterising participants who are likely to benefit from SiT using different fixed doses of ICS combined with the LABA, to optimise the approach for participants with different severities of asthma.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 December 2013 | Amended | Typo in search date in abstract and main text corrected |

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Göran Eriksson and Roberta Karlström from AstraZeneca for providing additional data.

CRG Funding Acknowledgement: The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Airways Group.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the review authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health.

John White was the Editor for this review and commented critically on the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Sources and search methods for the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register (CAGR)

Electronic searches: core databases

| Database | Frequency of search |

| CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library) | Monthly |

| MEDLINE (Ovid) | Weekly |

| Embase (Ovid) | Weekly |

| PsycINFO (Ovid) | Monthly |

| CINAHL (EBSCO) | Monthly |

| AMED (EBSCO) | Monthly |

Handsearches: core respiratory conference abstracts

| Conference | Years searched |

| American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) | 2001 onwards |

| American Thoracic Society (ATS) | 2001 onwards |

| Asia Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR) | 2004 onwards |

| British Thoracic Society Winter Meeting (BTS) | 2000 onwards |

| Chest Meeting | 2003 onwards |

| European Respiratory Society (ERS) | 1992, 1994, 2000 onwards |

| International Primary Care Respiratory Group Congress (IPCRG) | 2002 onwards |

| Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) | 1999 onwards |

MEDLINE search strategy used to identify trials for the CAGR

Asthma search

1. exp Asthma/

2. asthma$.mp.

3. (antiasthma$ or anti‐asthma$).mp.

4. Respiratory Sounds/

5. wheez$.mp.

6. Bronchial Spasm/

7. bronchospas$.mp.

8. (bronch$ adj3 spasm$).mp.

9. bronchoconstrict$.mp.

10. exp Bronchoconstriction/

11. (bronch$ adj3 constrict$).mp.

12. Bronchial Hyperreactivity/

13. Respiratory Hypersensitivity/

14. ((bronchial$ or respiratory or airway$ or lung$) adj3 (hypersensitiv$ or hyperreactiv$ or allerg$ or insufficiency)).mp.

15. ((dust or mite$) adj3 (allerg$ or hypersensitiv$)).mp.

16. or/1‐15

Filter to identify RCTs

1. exp "clinical trial [publication type]"/

2. (randomised or randomised).ab,ti.

3. placebo.ab,ti.

4. dt.fs.

5. randomly.ab,ti.

6. trial.ab,ti.

7. groups.ab,ti.

8. or/1‐7

9. Animals/

10. Humans/

11. 9 not (9 and 10)

12. 8 not 11

The MEDLINE strategy and RCT filter are adapted to identify trials in other electronic databases.

Appendix 2. Search terms ClinicalTrials.com

search terms: (budesonide AND formoterol) OR SMART OR Symbicort OR single inhaler therapy OR SiT

condition: asthma

study type: interventional studies

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with exacerbations requiring oral steroids | 4 | 9096 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.65, 0.87] |

| 1.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 3 | 6110 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.65, 0.92] |

| 1.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 2 | 2986 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.51, 0.91] |

| 2 Participants with serious adverse events | 4 | 9130 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.74, 1.13] |

| 2.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 3 | 6128 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.73, 1.17] |

| 2.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 2 | 3002 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.58, 1.37] |

| 3 Participants with severe exacerbations (hospitalisation or ER visit) | 3 | 7768 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.57, 0.90] |

| 3.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 3 | 6118 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.51, 0.86] |

| 3.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1650 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.58, 1.57] |

| 4 Morning PEF (L/min) | 2 | 5624 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.46 [‐3.85, 0.94] |

| 4.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 2 | 3965 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.74 [‐4.55, 1.06] |

| 4.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1659 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.7 [‐5.29, 3.89] |

| 5 Evening PEF (L/min) | 2 | 5624 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [‐2.24, 2.46] |

| 5.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 2 | 3965 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [‐2.39, 3.15] |

| 5.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1659 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.6 [‐5.06, 3.86] |

| 6 FEV1 predose (mL) | 3 | 7566 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 19.35 [2.72, 35.98] |

| 6.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 2 | 3819 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 20.06 [‐4.42, 44.54] |

| 6.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 2 | 3747 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 18.75 [‐3.91, 41.41] |

| 7 Rescue medication puffs required per day | 3 | 7725 | Mean Difference (Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.09 [‐0.27, 0.09] |

| 7.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 3 | 6066 | Mean Difference (Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 [‐0.35, 0.13] |

| 7.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1659 | Mean Difference (Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.15, 0.09] |

| 8 Symptoms (ACQ‐5) | 2 | 4432 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.07, 0.00] |

| 8.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 2 | 4432 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.07, 0.00] |

| 9 Symptom‐free days (%) | 2 | 5644 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.16 [‐2.99, 0.68] |

| 9.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 2 | 3985 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.30 [‐3.47, 0.87] |

| 9.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1659 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.80 [‐4.23, 2.63] |

| 10 Nocturnal awakenings (%) | 2 | 5624 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.08 [‐2.13, ‐0.03] |

| 10.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 2 | 3965 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.11 [‐2.34, 0.11] |

| 10.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1659 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.0 [‐3.02, 1.02] |

| 11 Quality of life AQLQ(S) | 1 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 11.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 1 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA, Outcome 4 Morning PEF (L/min).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA, Outcome 5 Evening PEF (L/min).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA, Outcome 6 FEV1 predose (mL).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA, Outcome 7 Rescue medication puffs required per day.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA, Outcome 8 Symptoms (ACQ‐5).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA, Outcome 9 Symptom‐free days (%).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA, Outcome 10 Nocturnal awakenings (%).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 SiT versus higher‐dose ICS/LABA + SABA, Outcome 11 Quality of life AQLQ(S).

Comparison 2. (Sensitivity analysis – Baseline severity).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with exacerbations requiring oral steroids | 3 | 7760 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.64, 0.88] |

| 1.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 3 | 6110 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.65, 0.92] |

| 1.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1650 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.43, 0.95] |

| 2 Participants with serious adverse events | 3 | 7787 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.73, 1.13] |

| 2.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 3 | 6128 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.73, 1.17] |

| 2.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1659 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.45, 1.47] |

| 3 Participants with severe exacerbations (hospitalisation or ER visit) | 3 | 7768 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.57, 0.90] |

| 3.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 3 | 6118 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.51, 0.86] |

| 3.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1650 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.58, 1.57] |

Comparison 3. (Sensitivity analysis – Blinding).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with exacerbations requiring oral steroids | 2 | 5625 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.59, 0.88] |

| 1.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 2 | 3975 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.59, 0.94] |

| 1.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1650 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.43, 0.95] |

| 2 Participants with serious adverse events | 2 | 5644 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.68, 1.27] |

| 2.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 2 | 3985 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.67, 1.42] |

| 2.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1659 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.45, 1.47] |

| 3 Participants with severe exacerbations (hospitalisation or ER visit) | 2 | 5625 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.56, 0.96] |

| 3.1 SiT versus higher flut/salm | 2 | 3975 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.49, 0.91] |

| 3.2 SiT versus higher bud/form | 1 | 1650 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.58, 1.57] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bousquet 2007 [AHEAD].

| Methods | Design: randomised, double‐blind, parallel‐group, multi‐national study. The first participant was enrolled on 2 May 2005, and the last participant completed the study on 29 May 2006. The trial included 184 centres in 17 countries. Duration of treatment was six months | |

| Participants |

Population: 2309 participants with asthma were randomly assigned to SiT (1154) and fluticasone/salmeterol (1155) Inclusion criteria: outpatients aged 12 years or older, with persistent asthma, who had been treated with ICS alone (800 to 1600 μg/d) or ICS (400 to 1000 μg/d) in combination with LABA for at least three months before study entry. All eligible participants had a prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) ≥ 50% of predicted normal value, with ≥ 12% reversibility following 1.0 mg terbutaline, and had experienced one or more clinically important asthma exacerbations (as judged by the clinician) in the previous 12 months (but none in the month before enrolment). To be eligible for randomisation at the end of run‐in, participants had to have used as‐needed terbutaline on five or more of the previous seven days, with no more than eight inhalations in any single day Exclusion criteria: recent respiratory infection, use of systemic corticosteroids within 30 days of study entry, use of any β‐blocking agent (including eye drops) and a smoking history of ≥ 10 pack‐years |

|

| Interventions |

Run‐in: During the two‐week run‐in period, participants used their regular maintenance dose of ICS (in combination with a LABA if used as maintenance before study entry) plus terbutaline (Bricanyls Turbuhalers, AstraZeneca, Sweden) as needed SiT: budesonide/formoterol 2*160/4.5 μg twice daily plus as needed (budesonide/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy) Inhaler: Symbicorts Turbuhalers, AstraZeneca, Sweden Control: fluticasone/salmeterol 50/500 μg twice daily plus terbutaline 0.4 mg/inhalation for symptom relief Inhaler: SeretideTM DiskusTM, GlaxoSmithKline, UK |

|

| Outcomes |