Abstract

Heart failure (HF) affects an increasing number of geriatric patients. The condition is classified according to whether the left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) is reduced or preserved. Many patients have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and face a shortage of effective therapeutic strategies. However, an emerging mechanical strategy for treatment is gaining momentum. Interatrial septal connection devices, i.e. V-wave device and Interatrial septal device, are new devices for patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. We review the function of these systems and the data from the recent clinical trials.

Interatrial septal connection device therapy provided favorable efficacy and safety profile applicable to a wide range of patients with HFpEF. However, the long-term effects of these devices on morbidity and mortality merits longitudinal studies and large multicenter randomized controlled trials.

Keywords: Interatrial device, IASD, V-wave, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, heart failure, device treatment for heart failure

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Heart Failure: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Morbidity

An increasing number of Americans are affected by heart failure as the patient population continues to age [1]. According to multiple studies, the estimated cost associated with heart failure hospitalizations is 34.5 billion dollars [2]. An estimated 5.1 million people are living with heart failure in the United States [3]. The mortality of heart failure is difficult to assess, and the 6 most used scoring systems for mortality in heart failure underestimated the risk in an elderly population [4]. Heart failure becomes more common with increasing age, according to the Framingham studies, which have observed multiple generations [5, 6]. The incidence of heart failure is expected to rise over the next 4 decades and approach 772,000 cases by 2040 [7].

Heart failure can be classified based on whether the left ventricular ejection fraction is “normal” or reduced, into heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The compensatory response involves neurohumoral mechanisms, including the renin-angiotensin system, sympathetic nervous system, and antidiuretic hormone release. These responses led to arterial vasoconstriction as well as an attempt to increase cardiac output via higher stroke volume and heart rate [8]. Although these compensatory responses can provide a short-term benefit, they have many negative consequences, such as elevation in the left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, rise in pulmonary arterial pressure, and eventual extravasation into the pulmonary and peripheral vascular beds [9, 10].

Regarding mortality, the ADHERE database (Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry) demonstrated high in-hospital mortality in HF patients independent of LV function. Patients who had HFpEF demonstrated lower in- hospital mortality compared to patients with HFrEF [11]. There is also a high prevalence of HFpEF patients, according to the OPTIMIZE-HF study (Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure). These patients had a post-discharge mortality risk and rehospitalization rate that were comparable to HFrEF patients. Even though the burden of HFpEF is high, there are insufficient therapeutic strategies and a lack of data for effective disease management. For example, the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers or beta-blockers did not influence the mortality or rehospitalization rates in patients with HFpEF [12]. However, HFpEF seems to have a better prognosis than HFrEF [13]. The increasing survival in HF patients contributes to a rising HF prevalence as well as a higher risk of rehospitalizations. Data have shown that in multiple white populations, the incidence of HF has remained stable [5]. The most common cause of death in HFpEF patients was non-cardiovascular (49%), whereas coronary disease (43%) accounted for the most deaths in HFrEF patients [5]. The mortality remains prevalent in HFpEF patients due to currently inadequate management strategies.

2. RISK FACTORS, CLASSIFICATION AND DIAGNOSIS

Common factors associated with HFpEF include female sex, older age, and hypertension [14]. The New York Heart Association classification system (NYHA) is used to grade the severity of heart failure and to quantify a patient’s functional capacity. The system is divided into four classes. NYHA Class I patients are asymptomatic and have adequate exercise tolerance. Class II patients have slight limitations to exercise and can have symptoms, such as chest pain or exertional dyspnea, but they are asymptomatic at rest. Class III patients have more severe symptoms with exercise and less than an ordinary activity but are comfortable at rest. Class IV patients have the highest severity of symptoms that occurs at rest and are exacerbated by any physical activity [15].

Evaluation of heart failure begins with a clinical assessment. Patients with heart failure present with signs and symptoms of dyspnea, fatigue, edema and rales most commonly. Diagnosis is based on the clinical picture aided by routine laboratory testing, chest X-ray and assessment of left ventricular function. The threshold typically used to distinguish preserved from reduced ejection fraction is 40% [16].

3. HFPEF AND HFMREF

An additional category of heart failure is called HfmrEF, defined as an ejection fraction of 40-49% [17]. This entity shares aging and hypertension as risk factors with HFpEF [18]. Additional risk factors for HFmrEF include diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and chronic kidney disease [19]. Regarding HFpEF, many clinicians use a composite score called H2FPEF to differentiate cardiac from non-cardiac etiology of dyspnea. The score is calculated by including BMI, age >60 years, atrial fibrillation, treatment with multiple antihypertensives, and echocardiographic parameters [20].

In HFpEF, there should be consideration of co-morbidities. One important co-morbidity is diabetes mellitus. These patients tend to be younger, male, obese, with a higher prevalence of multiple systemic comorbidities compared with non-diabetics [19]. Diabetics with HFpEF were more likely to be hospitalized and have reduced exercise tolerance [19]. Outcomes in this population were worse due to chronotropic incompetence, inflammation, and left ventricular hypertrophy [19]. In addtion, obese patients with HFpEF had reduced exercise capacity compared to nonobese patients [20].

4. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The factors associated with HFpEF development lead to changes at the cellular, metabolic and molecular levels [21]. These changes include tissue inflammation, myocardial ischemia, tissue fibrosis, cellular signaling alteration, and myocardial cellular hypertrophy [22]. Consequently, the LV will undergo remodeling, and this will affect chronotropy, inotropy, and lusitropy. The increased LV end-diastolic pressure will impair left atrial function and lead to pulmonary hypertension, microvascular dysfunction, as well as right ventricular dysfunction [23]. As a result of increased pressure in the left atrium, HFpEF patients commonly have exertional dyspnea [20]. During exercise, these patients have impaired LV relaxation, which reduces their stroke volume [24]. Studies have shown that creating a left-to-right atrial shunt reduces the elevated pressure and can improve symptoms.

5. MANAGEMENT

Two strong recommendations issued by the American College of Cardiology Foundation in 2013 state that hypertension needs to be controlled and that diuretics should be used to treat symptoms [25]. Given the limited success with therapies applied broadly to patients, future therapies can be individualized according to patient phenotypes, which might be more effective in the treatment of HFpEF [26].

One meta-analysis concluded that exercise training can be used as a nonpharmacologic approach to the treatment of HFpEF in order to improve the quality of life and functional capacity [27].

For example, a randomized, controlled, trial showed that 4 months of exercise training improved exercise capacity in older HFpEF patients [28]. Peak oxygen consumption was also increased in older HFpEF patients when they restricted their caloric intake. However, quality of life was not significantly improved with either exercise or caloric restriction [29].

Hospitalization for HF was reduced via pressure-directed diuresis therapy by implantation of a wireless system for hemodynamic monitoring in patients with NYHA class III. In this trial, CHAMPION trial, The CardioMEMS Heart Sensor allows monitoring of pressure to improve outcomes in NYHA Class III Heart Failure Patients, which was a prospective, single-blinded, randomized controlled trial testing hemodynamically guided diuresis and vasodilator management via CardioMEMS, microelectromechanical pressure sensor system, decreasing the incidence of decompensation leading to hospitalization. The results after an average of 17.6 months showed a reduction of 50% in the hospitalization rate [30].

Patients with HF are in need of new therapies [31]. An analysis of randomized, double-blind trials reported that beta-blockers increased LVEF in HF patients in sinus rhythm except those with a preserved EF [33]. Patients with atrial fibrillation also had an increase in LVEF when given beta-blockers if the EF was <50% at baseline. The benefit from beta-blockers in HFrEF is derived from an increase in LVEF, and patients with mid-range ejection fraction were found to benefit as well [32]. Beta-blockers did not benefit HFpEF patients and even increased the risk of hospitalization for HF. Patients with HFmrEF did not have this increased risk. Beta-blockers did not affect the mortality rate from cardiovascular disease in HFpEF [33].

For the medications shown to improve mortality in HFrEF, trials did not report statistically significant favorable outcomes in HFpEF. In the PEP-CHF (Perindopril in Elderly People with Chronic Heart Failure), a trial that examined patients with mild LV impairment (LVEF ~40-50%), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) improved exercise capacity and symptoms in patients with diastolic dysfunction, as well as reduced HF hospitalizations while patients were on the medication for a year, however, the study lacked sufficient power to demonstrate any benefits in morbidity and mortality [34].

The CHARM-Preserved study (Candesartan Cilexetil in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity) found that the angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) candesartan had a moderate impact in reducing admissions in HF patients with EF greater than 40%. Nonetheless, cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction and non-fatal stroke did not differ between the candesartan group and placebo [35].

The I-PRESERVE trial (Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction) showed no improvement in overall mortality or cardiovascular disease-related hospitalization. Diabetes independently increased the rate of HF hospitalization and cardiovascular death. HFpEF patients with diabetes have a poorer quality of life and worse prognosis [36].

The TOPCAT trial (Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist) showed that spironolactone did not significantly improve mortality from cardiovascular disease or HF hospitalization in HFpEF patients [37]. The STRUCTURE trial (Spironolactone in Myocardial Dysfunction with Reduced Exercise Capacity) looked at the ability of spironolactone to improve functional capacity and found that it significantly improved the exercise capacity in patients with exercise-induced elevation of LV filling pressures [38].

Chen et al. analyzed 14 randomized controlled clinical trials, including 6,428 patients with HFpEF or myocardial infarction with preserved ejection fraction on mineralocorticoid therapy and reported a 17% reduction in HF-related hospitalization, but with no significant improvement in mortality [39]. However, a larger meta-analysis conducted by Berbenetz et al., including 16,321 patients from 15 randomized controlled trials with HFpEF on mineralocorticoid therapy, demonstrated no evidence of reduction of adverse cardiac events and an increased risk of hyperkalemia and gynecomastia [40]. The difference in the outcomes of these studies is likely due to the heterogenicity of the populations included in these studies in risk factors.

The PARAGON-HF trial (Efficacy and Safety of LCZ696 Compared to Valsartan, on Morbidity and Mortality in Heart Failure Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction) reported that compared to valsartan, sacubitril/valsartan did not significantly reduce HF hospitalizations or death from cardiovascular causes in heart failure patients with an EF 45% or higher [41].

The NEAT-HFpEF trial (Nitrate's effect on Activity Tolerance in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction) demonstrated that isosorbide mononitrate did not improve exercise capacity or the quality of life of HFpEF patients compared to those who received placebo [42].

HFpEF patients who took the phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitor sildenafil improved biventricular function and pulmonary arterial pressure [43]. However, the RELAX trial (Effect of Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibition on Exercise Capacity and Clinical Status in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction) showed a two-year administration of sildenafil did not significantly improve the clinical condition or exercise capacity [44]. In addition, digoxin did not improve mortality or cardiovascular hospitalizations in ambulatory patients with diastolic dysfunction who received an ACE inhibitor and diuretics [45].

The current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) have no class 1 recommendations for treatment. Aldosterone antagonists have a class IIa recommendation for patients with LVEF >45% and stable basic metabolic panel to reduce hospitalizations. The use of nitrates, PDE-5 inhibitors, and nutritional supplementation has a Class III recommendation [46].

6. DEVICES

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is essentially characterized by elevated left ventricular filling pressures. The rationale for using an artificially created interatrial shunt is based on the hypothesis that this shunt would relieve left-sided pressures and alleviate some of the symptoms from HFpEF. This is exemplified by the evidence that on patients with mitral stenosis, an incidental atrial septal defect affords protection against left atrial pressure overload and the development of pulmonary venous hypertension. This condition, known as Lutembacher syndrome, appears to have no significant increase in the incidence of paradoxical embolism due to the left to right nature of the interatrial shunting [47, 48].

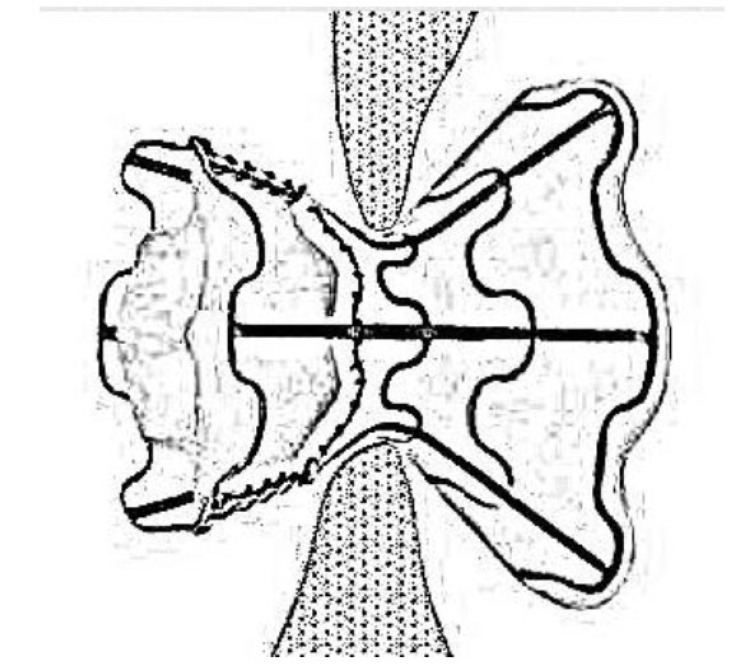

Two major devices have been tested in HFpEF, which are the interatrial shunt device (IASD) and the V-Wave device. The goal of these devices was to see whether left atrial pressure could be reduced by creating communication between the left and right atria. The IASD created by Corvia Medical (Previously DC Devices Inc., Tewksbury, MA) has two sides; a curved side that adapts with septal wall thicknesses and a flat side faces the wall of the left atrium. It has multiple legs with radiopaque markers to guide the procedure of implantation. The implantation procedure is minimally invasive through the venous puncture to the right atrium; then through a trans-septal puncture technique, the device is deployed via the delivery catheter system (Fig. 1) [49].

Fig. (1).

A sketch of the interatrial shunt device.

The V-wave device (V-Wave Ltd., Or Akiva, Israel) is shaped like an hourglass, spanning both left and right atria, and has a three-leaflet valve. It is also inserted percutaneously via the femoral vein, creating a 5mm shunt in the interatrial septum, and visualized with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). The device prevents shunting from the left to right atrium when the right atrial pressure (RAP) is greater than 2mm. Upon its placement, polytetrafluoroethylene expands to prevent biofilm formation over the device. Even though the biofilm is protective against thrombus formation, patients should receive anticoagulation with a Vitamin K antagonist or a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC) for 3 months as well as life-long aspirin. Hence, compared to anticoagulation with IASD, the duration of anticoagulation with V-wave is shorter [51, 52].

A study by Søndergaard et al. found that IASD created an 8mm interatrial shunt, which reduced left atrial pressure. The device was implanted percutaneously through the femoral vein, and 30-day outcomes were assessed. LV filling pressures were reduced, and NYHA class was improved in all but one patient. Pulmonary hypertension did not occur in any patient. The adverse events included implant displacement and HF rehospitalization [50].

The REDUCE LAP-HF trial (Reduce Elevated Left Atrial Pressure in Patients With Heart Failure), a phase 1 trial, evaluated the effect of IASD, which resulted in a statistically significant reduction of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) in 71% of patients from the time of insertion to 6 months, with persistent reduction at 12 months. Exertional PCWP was reduced at 6 months and 12 months. The NYHA class also improved during these time intervals. There were no major adverse events 6 months after device placement. After IASD placement, patients received dual antiplatelet therapy for 1 year. Additionally, IASD is on the same level as atrial tissue, which helps prevent thrombus development [52].

A subsequent study, the REDUCE LAP-HF I clinical trial, looked at one-year outcomes after IASD implantation. The outcomes were statistically significant for improvement in NYHA class, 6-minute walk distance, and quality of life as measured by the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure score. The left ventricular end-diastolic volume decreased, and the right ventricular end-diastolic volume increased. PCWP also improved in a subset of patients during exertion. The 1-year survival rate was 95%, and no complications occurred in relation to the device. The benefit of IASD implantation outweighed the risk, and confirmation of these findings are needed via further studies [53].

A single-center Canadian trial evaluated the IASD in 11 patients and reported 30-day outcomes. The mean PCWP decreased by 28% after 30 days. One of the patients was hospitalized within 30 days for HF exacerbation. The NYHA class improved after 30 days but did not show statistically significant improvement after 1 year. There were no major adverse events [54].

The MIRACLE EF (Multicenter InSync Randomized Clinical Evaluation) trial assessed patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy-pacemaker (CRT-P), NYHA II-III HF, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 36%-50%, left bundle branch block (LBBB), and no prior pacing therapy. The study was terminated prior to completion due to recruitment difficulty and other limiting factors. This trial demonstrated the challenges of constructing a large-scale, feasible study to determine new uses for implantable devices, necessitating smaller studies [55].

Kaye et al. studied the impact of an IASD in patient with HFpEF on survival and heart failure-related hospitalization for a median duration of 739 days and reported a 33% reduction in mortality rate based on score-predicted mortality. However, poorer exercise tolerance and a higher workload- corrected exercise pulmonary capillary wedge pressure were found in the IASD group [55].

The RESET study (Restoration of Chronotropic CompEtence in Heart Failure Patients with Normal Ejection Fraction) looked at rate-adaptive pacing (RAP) in HFpEF patients. However, it was also terminated early due to difficulty with recruitment Table 1 [24].

Table 1.

Summary of the interatrial septal device therapy trials.

| Name of the Study | Device | Number of Participants | Follow Up | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Søndergaard et al. | IASD | 11 | 30 days | LV filling pressures were reduced, and NYHA class was improved |

| REDUCE LAP-HF | IASD | 64 | 6-12 months | Reduction in both rest and exertional PCWP and NYHA class was improved |

| REDUCE LAP-HF I | IASD | 64 | >1 year | Confirmed >1-year safety of IASD |

| Del Trigo et al. | IASD | 11 | 30 days to 1 year | Reduction of NYHA in 30 days not at 1 year |

| Kaye et al. | IASD | - | 739 days | 33% reduction in mortality, with higher PCWP |

7. FUTURE

Although pharmacologic therapy has been suboptimal for HFpEF, there are trials in the pipeline that are evaluating sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors in HFpEF patients. These trials include DELIVER (Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the LIVEs of Patients with Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure) and EMPEROR-Preserved (Empagliflozin outcome trial in Patients With chronic heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction). See in ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03619213 and NCT03057951.

Currently, there is a prospective, single-arm, multicenter, nonrandomized, nonblinded trial called Reducing Lung Congestion Symptoms in Advanced Heart Failure (RELIEVE-HF), which enrolled 60 patients for V-Wave device placement. The inclusion criteria were NYHA class III or IV, medical optimization, and an LVEF ≥ 15%. The exclusion criteria included right ventricular systolic dysfunction, a right atrial pressure greater than left atrial pressure, congenital heart disease, severe pulmonary hypertension, and severe restrictive or obstructive lung disease. The primary endpoints of the trial included any major device-related adverse cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events within 6 months and 12 months of implantation, as well as the measurement of changes in the 6-minute walk test after 6 months. See in ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02511912.

The REDUCE LAP-HF TRIAL II is underway, which is a phase 3 trial with the IASD System II implant (Corvia Medical). It is a multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled, blinded trial, with a non-implant Control group with an estimated enrollment of 608 participants and a pre-specified 12-month composite primary endpoint of (a) incidence of and time-to-cardiovascular mortality or first non-fatal, ischemic stroke through 12 months; (b) total rate (first plus recurrent) per patient-year of heart failure (HF) admissions or healthcare facility visits for IV diuresis for HF through 12 months and time-to-first HF event; and (c) change in baseline KCCQ total summary score at 12 months which will hopefully provide high-quality data as to the effectiveness of this treatment modality. See in ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03088033.

CONCLUSION

The current pharmacologic options for HFpEF are limited and do not consistently demonstrate long-term favorable outcomes. Currently, the natural history of HFpEF is not reversible with pharmacological interventions. Since elevated LAP is crucial to the pathophysiology of HFpEF, it is reasonable to mechanically decrease the LAP via interatrial device placement, with both IASD and V-wave devices.

Accumulating evidence from several trials have reported that device implantation reduced HF hospitalization rates as well as improved symptoms, quality of life, and functional capacity with excellent safety. It is important to keep in mind that the primary objectives of these trials have been proof-of-concept and safety, and larger randomized studies assessing the benefit of these therapies are underway. Until the results from these studies are published, this modality of treatment is unlikely to become widespread. At the time of this article, there are no societal recommendations regarding specific indications to implant these devices, and the selection of patients for this therapy should likely only be performed within a clinical trial protocol.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To Dr. Inna Bukharovich, MD, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kings County Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY 11203, United States.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Díez-Villanueva P., Alfonso F. Heart failure in the elderly. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2016;13(2):115–117. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Heart Association. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: 2005 Update. Dallas, Tex: American Heart Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go A.S., Mozaffarian D., Roger V.L., Benjamin E.J., Berry J.D., Borden W.B., Bravata D.M., Dai S., Ford E.S., Fox C.S., Franco S., Fullerton H.J., Gillespie C., Hailpern S.M., Heit J.A., Howard V.J., Huffman M.D., Kissela B.M., Kittner S.J., Lackland D.T., Lichtman J.H., Lisabeth L.D., Magid D., Marcus G.M., Marelli A., Matchar D.B., McGuire D.K., Mohler E.R., Moy C.S., Mussolino M.E., Nichol G., Paynter N.P., Schreiner P.J., Sorlie P.D., Stein J., Turan T.N., Virani S.S., Wong N.D., Woo D., Turner M.B. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127(1):e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nutter A.L., Tanawuttiwat T., Silver M.A. Evaluation of 6 prognostic models used to calculate mortality rates in elderly heart failure patients with a fatal heart failure admission. Congest. Heart Fail. 2010;16(5):196–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roger V.L. The heart failure epidemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2010;7(4):1807–1830. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7041807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strömberg A., Mårtensson J. Gender differences in patients with heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2003;2(1):7–18. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owan T.E., Redfield M.M. Epidemiology of diastolic heart failure. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2005;47(5):320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inamdar A.A., Inamdar A.C. Heart Failure: Diagnosis, management and utilization. J. Clin. Med. 2016;5(7):62. doi: 10.3390/jcm5070062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benedict C.R., Johnstone D.E., Weiner D.H., Bourassa M.G., Bittner V., Kay R., Kirlin P., Greenberg B., Kohn R.M., Nicklas J.M. Relation of neurohumoral activation to clinical variables and degree of ventricular dysfunction: A report from the Registry of Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1994;23(6):1410–1420. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gheorghiade M., Zannad F., Sopko G., Klein L., Piña I.L., Konstam M.A., Massie B.M., Roland E., Targum S., Collins S.P., Filippatos G., Tavazzi L. International Working Group on Acute Heart Failure Syndromes. Acute heart failure syndromes: Current state and framework for future research. Circulation. 2005;112(25):3958–3968. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yancy C.W., Lopatin M., Stevenson L.W., De Marco T., Fonarow G.C. ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators. Clinical presentation, management, and in-hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function: A report from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Database. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006;47(1):76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fonarow G.C., Stough W.G., Abraham W.T., Albert N.M., Gheorghiade M., Greenberg B.H., O’Connor C.M., Sun J.L., Yancy C.W., Young J.B. OPTIMIZE-HF Investigators and Hospitals. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: A report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007;50(8):768–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerber Y., Weston S.A., Redfield M.M., Chamberlain A.M., Manemann S.M., Jiang R., Killian J.M., Roger V.L. A contemporary appraisal of the heart failure epidemic in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000 to 2010. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015;175(6):996–1004. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doughty R.N., Cubbon R., Ezekowitz J., et al. The survival of patients with heart failure with preserved or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: An individual patient data meta-analysis: Meta-analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure (MAGGIC). Eur. Heart J. 2013;33(14):1750–1757. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickstein K., Cohen-Solal A., Filippatos G., McMurray J.J., Ponikowski P., Poole-Wilson P.A., Strömberg A., van Veldhuisen D.J., Atar D., Hoes A.W., Keren A., Mebazaa A., Nieminen M., Priori S.G., Swedberg K. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2008;10(10):933–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu J.J., Ziaeian B., Fonarow G.C., Folsom A.R., Chambless L.E. Heart failure with mid-range (borderline) ejection fraction: Clinical implications and future directions. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(11):763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy Y.N.V., Carter R.E., Obokata M., Redfield M.M., Borlaug B.A. A simple, evidence-based approach to help guide diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2018;138(9):861–870. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindman B.R., Dávila-Román V.G., Mann D.L., McNulty S., Semigran M.J., Lewis G.D., de las Fuentes L., Joseph S.M., Vader J., Hernandez A.F., Redfield M.M. Cardiovascular phenotype in HFpEF patients with or without diabetes: A RELAX trial ancillary study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;64(6):541–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obokata M., Reddy Y.N.V., Pislaru S.V., Melenovsky V., Borlaug B.A. Evidence supporting the existence of a distinct obese phenotype of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2017;136(1):6–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borlaug B.A. The pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2014;11(9):507–515. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma C., Luo H., Fan L., Liu X., Gao C. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: An update on pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2020;53(7):e9646. doi: 10.1590/1414-431x20209646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali D., Callan N., Ennis S., Powell R., McGuire S., McGregor G., Weickert M.O., Miller M.A., Cappuccio F.P., Banerjee P. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) pathophysiology study (IDENTIFY-HF): Does increased arterial stiffness associate with HFpEF, in addition to ageing and vascular effects of comorbidities? Rationale and design. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e027984. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kass D.A., Kitzman D.W., Alvarez G.E. The restoration of chronotropic competence in heart failure patients with normal ejection fraction (RESET) study: Rationale and design. J. Card. Fail. 2010;16(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yancy C.W., Jessup M., Bozkurt B., Butler J., Casey D.E., Jr, Drazner M.H., Fonarow G.C., Geraci S.A., Horwich T., Januzzi J.L., Johnson M.R., Kasper E.K., Levy W.C., Masoudi F.A., McBride P.E., McMurray J.J., Mitchell J.E., Peterson P.N., Riegel B., Sam F., Stevenson L.W., Tang W.H., Tsai E.J., Wilkoff B.L. WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16):e240–e327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Senni M., Paulus W.J., Gavazzi A., Fraser A.G., Díez J., Solomon S.D., Smiseth O.A., Guazzi M., Lam C.S., Maggioni A.P., Tschöpe C., Metra M., Hummel S.L., Edelmann F., Ambrosio G., Stewart Coats A.J., Filippatos G.S., Gheorghiade M., Anker S.D., Levy D., Pfeffer M.A., Stough W.G., Pieske B.M. New strategies for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: The importance of targeted therapies for heart failure phenotypes. Eur. Heart J. 2014;35(40):2797–2815. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukuta H., Goto T., Wakami K., Ohte N. Effects of drug and exercise intervention on functional capacity and quality of life in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2016;23(1):78–85. doi: 10.1177/2047487314564729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitzman D.W., Brubaker P.H., Morgan T.M., Stewart K.P., Little W.C. Exercise training in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: A randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3(6):659–667. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.958785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitzman D.W., Brubaker P., Morgan T., Haykowsky M., Hundley G., Kraus W.E., Eggebeen J., Nicklas B.J. Effect of caloric restriction or aerobic exercise training on peak oxygen consumption and quality of life in obese older patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(1):36–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.17346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abraham W.T., Adamson P.B., Bourge R.C., Aaron M.F., Costanzo M.R., Stevenson L.W., Strickland W., Neelagaru S., Raval N., Krueger S., Weiner S., Shavelle D., Jeffries B., Yadav J.S. CHAMPION Trial Study Group. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9766):658–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng R.K., Cox M., Neely M.L., Heidenreich P.A., Bhatt D.L., Eapen Z.J., Hernandez A.F., Butler J., Yancy C.W., Fonarow G.C. Outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction in the Medicare population. Am. Heart J. 2014;168(5):721–730. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleland J.G.F., Bunting K.V., Flather M.D., Altman D.G., Holmes J., Coats A.J.S., Manzano L., McMurray J.J.V., Ruschitzka F., van Veldhuisen D.J., von Lueder T.G., Böhm M., Andersson B., Kjekshus J., Packer M., Rigby A.S., Rosano G., Wedel H., Hjalmarson Å., Wikstrand J., Kotecha D. Beta-blockers in Heart Failure Collaborative Group. Beta-blockers for heart failure with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction: An individual patient-level analysis of double-blind randomized trials. Eur. Heart J. 2018;39(1):26–35. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silverman D.N., Plante T.B., Infeld M., Callas P.W., Juraschek S.P., Dougherty G.B., Meyer M. Association of β-Blocker use with heart failure hospitalizations and cardiovascular disease mortality among patients with heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction: A secondary analysis of the TOPCAT trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019;2(12):e1916598. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleland J.G.F., Tendera M., Adamus J., Freemantle N., Polonski L., Taylor J. PEP-CHF Investigators. The perindopril in elderly people with chronic heart failure (PEP-CHF) study. Eur. Heart J. 2006;27(19):2338–2345. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yusuf S., Pfeffer M.A., Swedberg K., Granger C.B., Held P., McMurray J.J., Michelson E.L., Olofsson B., Ostergren J. CHARM Investigators and Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: The CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet. 2003;362(9386):777–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kristensen S.L., Mogensen U.M., Jhund P.S., Petrie M.C., Preiss D., Win S., Køber L., McKelvie R.S., Zile M.R., Anand I.S., Komajda M., Gottdiener J.S., Carson P.E., McMurray J.J. Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics and cardiovascular outcomes according to diabetes status in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: A report from the I-Preserve Trial (Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction). Circulation. 2017;135(8):724–735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pitt B., Pfeffer M.A., Assmann S.F., Boineau R., Anand I.S., Claggett B., Clausell N., Desai A.S., Diaz R., Fleg J.L., Gordeev I., Harty B., Heitner J.F., Kenwood C.T., Lewis E.F., O’Meara E., Probstfield J.L., Shaburishvili T., Shah S.J., Solomon S.D., Sweitzer N.K., Yang S., McKinlay S.M. TOPCAT Investigators. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370(15):1383–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kosmala W., Rojek A., Przewlocka-Kosmala M., Wright L., Mysiak A., Marwick T.H. Effect of aldosterone antagonism on exercise tolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016;68(17):1823–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.07.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Y., Wang H., Lu Y., Huang X., Liao Y., Bin J. Effects of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in patients with preserved ejection fraction: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Med. 2015;13:10. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0261-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berbenetz N.M., Mrkobrada M. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists for heart failure: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2016;16(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s12872-016-0425-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solomon S.D., McMurray J.J.V., Anand I.S., Ge J., Lam C.S.P., Maggioni A.P., Martinez F., Packer M., Pfeffer M.A., Pieske B., Redfield M.M., Rouleau J.L., van Veldhuisen D.J., Zannad F., Zile M.R., Desai A.S., Claggett B., Jhund P.S., Boytsov S.A., Comin-Colet J., Cleland J., Düngen H.D., Goncalvesova E., Katova T., Kerr Saraiva J.F., Lelonek M., Merkely B., Senni M., Shah S.J., Zhou J., Rizkala A.R., Gong J., Shi V.C., Lefkowitz M.P. PARAGON-HF Investigators and Committees. PARAGON-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin–neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381(17):1609–1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Redfield M.M., Anstrom K.J., Levine J.A., Koepp G.A., Borlaug B.A., Chen H.H., LeWinter M.M., Joseph S.M., Shah S.J., Semigran M.J., Felker G.M., Cole R.T., Reeves G.R., Tedford R.J., Tang W.H., McNulty S.E., Velazquez E.J., Shah M.R., Braunwald E. NHLBI Heart Failure Clinical Research Network. NHLBI Heart Failure Clinical Research Network. Isosorbide mononitrate in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373(24):2314–2324. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guazzi M., Vicenzi M., Arena R., Guazzi M.D. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A target of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition in a 1-year study. Circulation. 2011;124(2):164–174. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.983866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Redfield M.M., Chen H.H., Borlaug B.A., Semigran M.J., Lee K.L., Lewis G., LeWinter M.M., Rouleau J.L., Bull D.A., Mann D.L., Deswal A., Stevenson L.W., Givertz M.M., Ofili E.O., O’Connor C.M., Felker G.M., Goldsmith S.R., Bart B.A., McNulty S.E., Ibarra J.C., Lin G., Oh J.K., Patel M.R., Kim R.J., Tracy R.P., Velazquez E.J., Anstrom K.J., Hernandez A.F., Mascette A.M., Braunwald E. RELAX Trial. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309(12):1268–1277. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahmed A., Rich M.W., Fleg J.L., Zile M.R., Young J.B., Kitzman D.W., Love T.E., Aronow W.S., Adams K.F., Jr, Gheorghiade M. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: The ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation. 2006;114(5):397–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yancy C.W., Jessup M., Bozkurt B., Butler J., Casey D.E., Jr, Colvin M.M., Drazner M.H., Filippatos G.S., Fonarow G.C., Givertz M.M., Hollenberg S.M., Lindenfeld J., Masoudi F.A., McBride P.E., Peterson P.N., Stevenson L.W., Westlake C. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;70(6):776–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahajan K., Oliver T.I. Lutembacher Syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470307/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aminde L.N., Dzudie A., Takah N.F., Ngu K.B., Sliwa K., Kengne A.P. Current diagnostic and treatment strategies for Lutembacher syndrome: The pivotal role of echocardiography. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2015;5(2):122–132. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2015.03.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feldman T., Komtebedde J., Burkhoff D., Massaro J., Maurer M.S., Leon M.B., Kaye D., Silvestry F.E., Cleland J.G., Kitzman D., Kubo S.H., Van Veldhuisen D.J., Kleber F., Trochu J.N., Auricchio A., Gustafsson F., Hasenfuβ G., Ponikowski P., Filippatos G., Mauri L., Shah S.J. Transcatheter interatrial shunt device for the treatment of heart failure: Rationale and design of the randomized trial to REDUCE Elevated Left Atrial Pressure in Heart Failure (REDUCE LAP-HF I). Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9(7):e003025. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Søndergaard L., Reddy V., Kaye D., Malek F., Walton A., Mates M., Franzen O., Neuzil P., Ihlemann N., Gustafsson F. Transcatheter treatment of heart failure with preserved or mildly reduced ejection fraction using a novel interatrial implant to lower left atrial pressure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014;16(7):796–801. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amat-Santos I.J., Bergeron S., Bernier M., Allende R., Barbosa Ribeiro H., Urena M., Pibarot P., Verheye S., Keren G., Yaacoby M., Nitzan Y., Abraham W.T., Rodés-Cabau J. Left atrial decompression through unidirectional left- to-right interatrial shunt for the treatment of left heart failure: First-in-man experience with the V-Wave device. EuroIntervention. 2015;10(9):1127–1131. doi: 10.4244/EIJY14M05_07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hasenfuß G., Hayward C., Burkhoff D., Silvestry F.E., McKenzie S., Gustafsson F., Malek F., Van der Heyden J., Lang I., Petrie M.C., Cleland J.G., Leon M., Kaye D.M. REDUCE LAP-HF study investigators. A transcatheter intracardiac shunt device for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (REDUCE LAP-HF): A multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10025):1298–1304. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00704-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaye D.M., Hasenfuß G., Neuzil P., Post M.C., Doughty R., Trochu J.N., Kolodziej A., Westenfeld R., Penicka M., Rosenberg M., Walton A., Muller D., Walters D., Hausleiter J., Raake P., Petrie M.C., Bergmann M., Jondeau G., Feldman T., Veldhuisen D.J., Ponikowski P., Silvestry F.E., Burkhoff D., Hayward C. One-year outcomes after transcatheter insertion of an interatrial shunt device for the management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9(12):e003662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Del Trigo M., Bergeron S., Bernier M., Amat-Santos I.J., Puri R., Campelo-Parada F., Altisent O.A., Regueiro A., Eigler N., Rozenfeld E., Pibarot P., Abraham W.T., Rodés-Cabau J. Unidirectional left-to-right interatrial shunting for treatment of patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A safety and proof-of-principle cohort study. Lancet. 2016;387(10025):1290–1297. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00585-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Linde C., Curtis A.B., Fonarow G.C., Lee K., Little W., Tang A., Levya F., Momomura S., Manrodt C., Bergemann T., Cowie M.R. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in chronic heart failure with moderately reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: Lessons from the Multicenter InSync Randomized Clinical Evaluation MIRACLE EF study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016;202:349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaye D.M., Petrie M.C., McKenzie S., Hasenfuβ G., Malek F., Post M., Doughty R.N., Trochu J.N., Gustafsson F., Lang I., Kolodziej A., Westenfeld R., Penicka M., Rosenberg M., Hausleiter J., Raake P., Jondeau G., Bergmann M.W., Spelman T., Aytug H., Ponikowski P., Hayward C. REDUCE LAP-HF study investigators. Impact of an interatrial shunt device on survival and heart failure hospitalization in patients with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2019;6(1):62–69. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]