Abstract

Refugees and asylum seekers often face delayed mental health diagnoses, treatment, and care. COVID-19 has exacerbated these issues. Delays in diagnosis and care can reduce the impact of resettlement services and may lead to poor long-term outcomes. This scoping review aims to characterize studies that report on mental health screening for resettling refugees and asylum seekers pre-departure and post-arrival to a resettlement state. We systematically searched six bibliographic databases for articles published between 1995 and 2020 and conducted a grey literature search. We included publications that evaluated early mental health screening approaches for refugees of all ages. Our search identified 25,862 citations and 70 met the full eligibility criteria. We included 45 publications that described mental health screening programs, 25 screening tool validation studies, and we characterized 85 mental health screening tools. Two grey literature reports described pre-departure mental health screening. Among the included publications, three reported on two programs for women, 11 reported on programs for children and adolescents, and four reported on approaches for survivors of torture. Programs most frequently screened for overall mental health, PTSD, and depression. Important considerations that emerged from the literature include cultural and psychological safety to prevent re-traumatization and digital tools to offer more private and accessible self-assessments.

Keywords: refugee, asylum seeker, mental health, resettlement, migration, screening, health assessment

1. Introduction

Approximately 79.5 million people around the world have been forced to leave their homes, and nearly 26 million are considered refugees [1]. The COVID-19 pandemic has also created unprecedented delays in resettlement [2]. In 2022, a projected 1.47 million refugees will need urgent resettlement [3]. ”Resettlement” is the selection and transfer of refugees from a state in which they have sought temporary protection to a third state that has agreed to admit them as refugees with permanent residence status [4]. This status ensures protection against refoulement and provides a resettled refugee and their family or dependents with access to civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights [1]. Conversely, an asylum seeker is someone whose claim for protection and resettlement has not yet been finally decided on by the country in which the claim is submitted [5].

Providing refugees and asylum seekers appropriate and timely mental health services is a global challenge [6]. Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically reduced programs and delayed refugee resettlement, thereby increasing uncertainty and isolation [2,7]. Early screening and care for common mental health disorders is now recognized as a priority for resettlement programs [8,9]. However, there is a risk that screening for mental health can lead to re-traumatization [10]. Therefore, screening approaches should incorporate safety, comfort, physical care, ensure access to basic needs, and use culturally appropriate tools and clinical assessments [11].

Refugees encounter many risk factors for poor mental health outcomes before, during, and after migration and resettlement [6]. Such factors include exposure to traumatic violence, genocide, and economic hardship; experience of physical harm and separation; and poor socioeconomic conditions once resettled, such as social isolation, racism, and unemployment [12,13]. Refugees are at risk of developing common mental health disorders including depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and related somatic health symptoms [6,14,15]. Epidemiological studies indicate that the age-standardized point prevalence of PTSD and major depression in conflict-affected populations is estimated to be 12.9% and 7.6%, respectively [16]. As a comparison, it has been estimated that approximately 4.4% of the world’s population suffers from major depression [17] and 3.3% from PTSD [18]. However, the true prevalence of common mental disorders among refugees could be higher since there is no systematic or consistent approach to diagnose mental disorders in this population [12].

Pre-departure overseas health assessments and screening represent a potential, but often underdeveloped, component of the migration health screening process for resettling refugees. A health assessment is a medical examination, usually conducted by a registered medical practitioner (or “panel physician”) based on criteria set by the resettlement state [19]. Health assessments are conducted as a measure to limit or prevent the transmission of diseases of public health importance to their host populations and to avert potential costs and burdens on local health systems [19]. These assessments support the health of migrating populations as well as protect domestic public health, promote collaboration with international health partners, and strengthen understanding of the health profiles of diverse arriving populations [20]. For example, health assessment results may be communicated to local resettlement agencies so that appropriate health services can be arranged for the refugees on arrival [21]. However, if refugee health assessment processors are to meaningfully contribute to the public health good, then they need to overcome exclusionary approaches, be linked to the national health systems, and be complemented by health promotion measures to enhance the health-seeking behaviour of refugees [19]. Currently, there are 24 official resettlement states (See Supplementary File S1) for whom pre-departure mental health screening approaches for refugees could be beneficial.

Current health assessments do not routinely screen for common mental health concerns. Providing early care for treatable mental health conditions could help refugees benefit from resettlement, language, cultural and employment training programs, develop positive relationships, reduce intergenerational trauma, gain access to employment, and ultimately lead to more meaningful and productive lives [8]. Developing early common mental health screening and treatment programs is therefore an important first step when integrating refugees into local primary healthcare services [22].

The majority of synthesized literature on refugee mental health to date focuses on the prevalence of mental illness (for example, [23,24,25]); access to mental health services (for example, [26,27]); and tailored programs and interventions (for example, [28,29,30]). There is limited available evidence which characterizes screening tools and procedures specific to assessing mental health among refugee and asylum-seeking populations during resettlement. One existing systematic review identified only seven screening tools for trauma and mental health assessment in refugee children [31]. Older reviews suggest that more tools have been used among adult populations; however, the authors concluded that existing tools had limited or untested validity and reliability in refugees [32,33].

2. Research Objectives

The objective of this scoping review is to identify and characterize mental health screening approaches for refugees and asylum seekers. This review aims to inform and catalyze country-level resettlement policies and practices regarding the identification of mental health conditions and linkage to care by addressing the following research question:

What are the characteristics of existing and emerging approaches to mental health screening for resettling refugees and asylum seekers? (See Box 1).

Box 1. Research sub-questions.

-

➢

In what setting(s) has refugee mental health screening been conducted?

-

➢

At what point in time during the migration pathway is screening conducted and for what purpose?

-

➢

What tools have been used in the refugee population, and what conditions do they screen for?

-

➢

In which language(s) and formats are mental health assessments delivered?

-

➢

Have any of these tools been adapted, validated, or evaluated specifically for use among refugees?

-

➢

What approaches are used to screen vulnerable subgroups?

-

➢

What are the professional characteristics and training of individuals who administer mental health assessments?

-

➢

What are the lessons learned from pilots/approaches that have been tried on the ground?

3. Methods

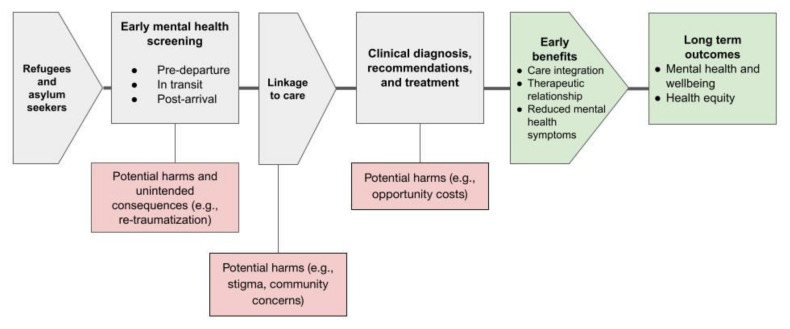

We registered the methods of this scoping review on the Open Science Framework (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/RWVBE) and published an open-access protocol [34]. We reported our review according to the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR; [35]) [Supplementary File S2]. We reported our search strategy according to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews (PRISMA-S; [36]) [Supplementary File S3]. We created a logic model to outline the conceptual framework involved in the mental health screening process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Logic model of mental health screening along the resettlement pathway.

4. Eligibility Criteria

We identified eligible studies using the SPIDER acronym (Table 1). We included publications of quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods evidence that evaluated approaches to the early screening of mental health disorders among resettling refugees and asylum seekers of all ages. We defined the resettling period as 6 months prior to travel and 12 months after arrival in the resettlement country. We excluded qualitative publications that focused on patient experiences rather than characteristics of early screening approaches. By “approach”, we mean the process from the assessment of mental health to the transfer of results to the patient, immigration officials, or healthcare providers, including the development of the assessment tool itself if it included pilot-testing and validation among refugees. We considered documents published in any language. We restricted the year of publication from 1995 to 2020 to coincide with the creation of the Annual Tripartite Consultations on Resettlement (ATCR) and subsequent UNHCR Resettlement Handbook [37].

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

| SPIDER | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Sample | Refugees and asylum seekers of all ages | All populations other than refugees and asylum seekers |

| Phenomenon of Interest | Pre-settlement overseas screening approaches or post-arrival (<12 months) approaches for mental health | Screening for other health conditions Routine screening after 1 year post-arrival |

| Design | Experimental and quasi-experimental studies Observational studies Program evaluations Resettlement handbooks and manuals Policy documents Development & validation studies Clinical assessment studies |

Systematic reviews Scoping reviews Literature reviews Commentaries/opinion Theoretical papers |

| Evaluation | Characteristics of screening approaches | Estimates of effect Experiences/views |

| Research type | Quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method documents published in peer-reviewed or grey literature | N/A |

| Other | ||

| Year of publication | 1995–2020 | Prior to 1995 |

| Language of publication | All languages eligible | N/A |

5. Search Methods

We developed our search strategies in consultation with a health sciences librarian. We searched the following databases, individually, from 1995 to 2020: EMBASE (Ovid; 1995 to 24 December 2020); Medline (Ovid; 1995 to 21 December 2020); PsycINFO (Ovid; 1995 to December Week 3 2020); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Ovid; 1995 to January Week 2 2021); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (Ebsco; January 1995 to January Week 2 2021). We used a combination of keywords and subject headings. Complete search strategies for each database are available in Supplementary File S4.

In addition to searching bibliographic databases, we conducted a focused grey literature search. We searched the government websites from the 24 countries listed in Supplementary File S1 and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). We contacted an immigration policy researcher from each country of the Immigration and Refugee Health Working Group (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, United Kingdom, United States of America) and other experts to identify any missing literature.

6. Screening and Selection

We used Covidence software [38] and a two-part study selection process: (1) a title and abstract review, and (2) full-text review. Two review authors independently assessed all potential studies and documents against a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). We resolved any disagreements through discussion, or we consulted a third review author.

7. Data Extraction and Management

We developed a standardized extraction sheet. Pairs of reviewers extracted data in duplicate and independently. They compared results and resolved disagreements by discussion or with help from a third reviewer. To ensure the validity of the data extraction form, we piloted this form with two reviewers and the accuracy of the content was confirmed with a third reviewer. Reviewers extracted all variables identified in our protocol [34].

8. Synthesis of Results

We summarized the data according to the setting, timing, and purpose of the assessment, as well as the characteristics of screening tools and administrators. We narratively described approaches for special populations and implementation lessons learned, as described by the study authors. As a scoping review, the purpose of this study is to present an overview of the research rather than to evaluate the quality of the individual studies; therefore, we did not conduct an overall assessment or appraisal of the strength of the evidence.

9. Results

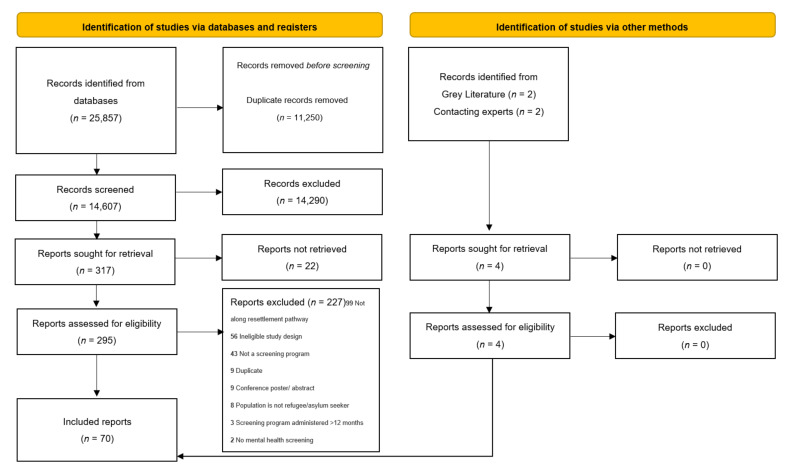

Our systematic search identified 25,857 citations. After the removal of duplicates, we screened 14,607 citations by title and abstract. We retained 315 for full text review. Of these, 66 met full eligibility criteria. Reasons for exclusion are presented in Figure 2 and Supplementary File S5. Additionally, our grey literature search identified two additional publications for inclusion. Two studies were brought forward by immigration representatives and other subject matter experts, for a total of 70 included studies.

Figure 2.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

10. Characteristics of Included Studies

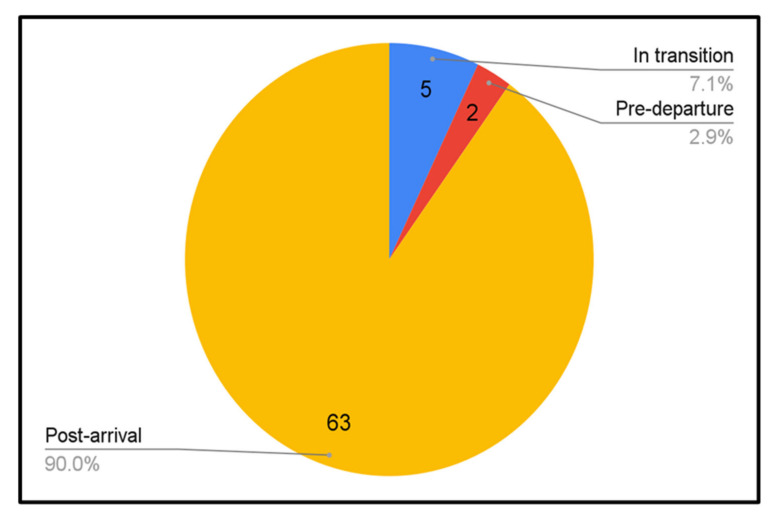

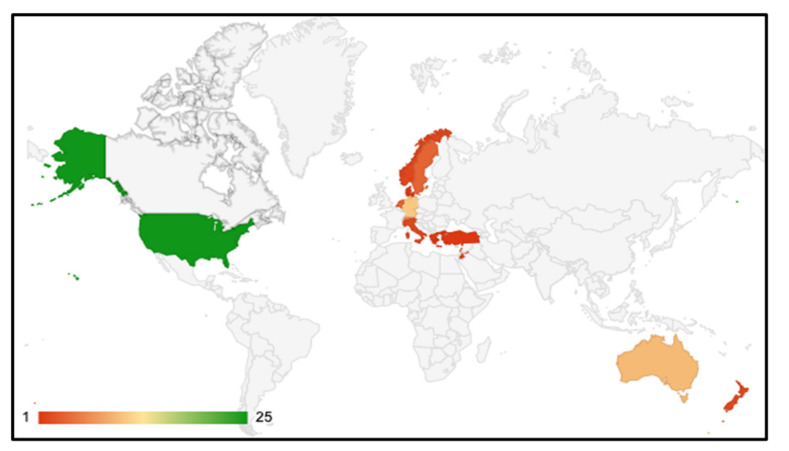

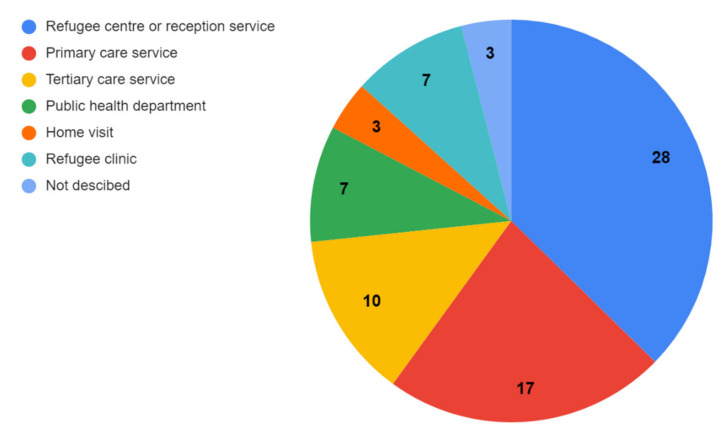

We summarized the characteristics of all included publications of refugee mental health screening approaches (see Table 2). This included 45 publications which described screening programs, and 25 validation studies conducted in 13 different resettlement countries. Most assessments (90% of included studies) occurred within the first 12 months post-arrival to the resettlement country (see Figure 3). We identified two reports of pre-departure screening prior to resettlement [4,39]. Post-arrival assessments were most common in the USA, Switzerland, and Australia (See Figure 4). While some assessments were conducted in tertiary care settings (i.e., hospitals), most refugees sought health assessments in primary care clinics or interdisciplinary refugee health clinics (see Figure 5). Assessments were also held in community or public health centres or other settings such as detention centres, national intermediary centres, independent medical examinations, and torture treatment centres. One study reported that mental health screening was most effective when completed during a home visit [40]. Among publications which included asylum seeker populations (18/70), the majority conducted screening at reception centres and asylum accommodations.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies (n = 70).

| Study | Design | Setting | Timing of Assessment | Population | Mental Health Condition Assessed and Assessment Tool | Administration Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Obaidi (2015) [41] | Screening program | Refugee health care programs USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Burma, Haiti, Sudan, Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Cuba |

Mental health assessment was not widely practiced (6/16 refugee-serving organizations). Assessment conducted by asking a few basic questions, e.g., for adults, any history of sleep problems, loss of energy, loss of appetite, feeling depressed, torture; and asking about the story of the refugee’s journey; for children, any history of seizures, learning problems, and head injuries In Denver, screening includes a DSM-based, non-validated questionnaire designed to detect major depression and PTSD The Seattle and New Mexico programs offer the Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15) [PTSD, Depression, Anxiety] |

In Denver, the mental health screening is conducted by a master’s level social worker Screening using the RHS-15 administered by health care providers. Clients themselves can complete the form if they have the appropriate level of education Interpreter not present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Arnetz (2014) [42] | Validation study | Community centees USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Age 18–69 years, M = 33.41, SD = 11.29 54% male Iraq |

Pre-immigration trauma exposure: Trauma section of Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) PTSD: Civilian version of the PTSD Checklist (PCL-C) Depression: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) |

Administered by trained Arabic-speaking research personnel Interpreter present Self-assessment survey 120 min |

| Baird (2020) [43] | Screening program | Nurse-managed urban primary care safety-net clinic USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Mean age 32.8 years, SD = 13.6, Range = 17–72; 46% male. Country of origin not reported |

Emotional distress including anxiety, depression, and PTSD: Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15) | Administered by trained Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) family nurse practitioners Interpreter present Likert Scale, oral interview 60 min |

| Barbieri (2019) [44] | Validation study | Outpatient clinic and reception centre Italy |

Post-arrival | Refugees and asylum seekers Age 18 and older (M = 25.1 years, SD = 6.7); 86% male Participants were from 19 African countries, mainly West Africa |

PTSD: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5) CPTSD: International Trauma Questionnaire (ICD-11) |

Administered by cultural mediator, a medical doctor, and a clinical psychologist Interpreter present Oral interview 60–90 min |

| Barnes (2001) [40] | Screening program | Local health department not affiliated with a hospital, combined with home visits USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Age 18–74 46.4% male Vietnam, Cuba, Bosnia, and African countries |

Depression: DSM-IV criteria psychiatric interview | Administered by psychiatric residents with multi-national immigrant backgrounds (Africa and India) Interpretation provided by a paid interpreter (Vietnamese), administrative assistant (Bosnian), or nurse (Spanish). Family members also acted as interpreters (e.g., Farsi) Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Bertelsen (2018) [45] | Screening program | Primary care torture treatment centre USA |

Post-arrival | Asylum seekers Mean age of 36.6 years (SD10.2) 66.2% male Majority from Sub-Saharan Africa (Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Democratic Republic of Congo being the most represented). Minority from Asia (with the Nepal and Tibet accounting for the majority of these) |

PTSD: Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) Major depressive disorder: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) |

Administered by mental health professionals Interpreter present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Bjarta (2018) [46] | Validation study | Asylum accommodations and health and service centres Sweden |

Post-arrival | Refugees and asylum seekers aged 18 years and older; 72% male Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Eritrea, and Somalia |

PTSD, depression, anxiety: Refugee Health Screener (RHS-13) Depression: Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) Generalized anxiety: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) PTSD: Primary Care PTSD-4 (PC-PTSD-4) Quality of life: World Health Organization Quality of Life–Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF) |

Self-assessment facilitated by bilingual administration staff Interpreter (bilingual staff) present Tablet. Audio support was available in Arabic, Dari, Farsi, and Tigrinya for individuals with low reading proficiency Assessment time not reported |

| Boyle (2019) [47] | Screening program | Refugee antenatal clinic Australia |

Post-arrival | Refugees of childbearing age (below 35 years old) 100% female Afghanistan, Myanmar, Iraq, the Republic of South Sudan, and Sri Lanka. |

Depression and anxiety: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Perinatal mental health: Monash Psychosocial Screening Tool |

Self-assessment. Clinic staff available for assistance Interpreter present if needed Electronic via tablet 6–10 min |

| Brink (2016) [48] | Validation study | Primary care clinic USA |

Post-arrival | Karen Refugees Aged 18–80 (M = 38.09, SD 13.82) 30% male Burma |

PTSD and MDD: PTSD and MDD portions of the structured clinical interview for DSM disorders (SCID-CV for DSM-IV) | A physician with mental health training and a Karen interpreter administered the measures Oral interview and Likert-scale questionnaire Assessment time not reported |

| Buchwald (1995) [49] | Screening program | Ten refugee public health clinics USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Aged 16–85 yo (average age 31) 95% male Vietnam |

Depression: Vietnamese Depression Scale | Administered by trained community health nurse Interpreter present Self-assessment 5 min |

| Churbaji (2020) [50] | Validation study | University hospital Germany |

Post-arrival | Refugees Mean age 33.5 yo 75% male Syria, Iraq, Palestine |

Depression and PTSD: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Depression: Patient Health Questionnaire, 9 (PHQ-9) PTSD: Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) |

Not reported |

| Cook (2015) [51] | Screening program | Primary care clinic USA |

Post-arrival | Arabic-speaking Karen refugees Aged 18 yo and over (mean age: 35 (SD 14.6) 51% male |

Four semi-structured items which asked retrospectively about lifetime experiences of primary and secondary war trauma and torture | Administered by trained research assistants (social work trainees) Interpreter present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Di Pietro (2021) [52] | Validation study | Second-line reception centre Italy |

Post-arrival | Unaccompanied migrant minors Age 12–18 yo 100% male Bangladesh, Egypt, Gambia, Senegal, Benin, Tunisia, Guinea Bissau, Morocco |

Overall psychological needs: Unaccompanied Migrant Minors Questionnaire (AEGIS-Q) | Interpreter not present Self-administered with cultural mediator 20 min |

| Durieux-Paillard (2006) [53] | Validation study | Migrant health centre (University Hospital) Switzerland |

Post-arrival | Asylum seekers Age 16 years or older |

MDD and PTSD: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) | Nurses without mental health training Interpreter present Oral interview 45 min |

| El Ghaziri (2019) [54] | Screening program | Centre for primary care and public health Switzerland |

Post-arrival | Refugee families Members over age 8 yo 40–60% female Syria |

Risk behaviours: ASSIST Support: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) Parent-child relationship: Family Peer Relationship Questionnaire, Arabic version (A-FPRQ) Adults: major depressive disorder, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Children: major depressive disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Kids (MINI Kid) |

Research assistant Interpreter present (research assistant) Administration mode not reported Assessment time not reported |

| Eytan (2007) [55] | Validation study | Primary care clinic Switzerland | In transition | Refugees Mean age 30 yo 75% male 33 countries, mostly Africa and Central or Eastern Europe |

Major depressive episodes and PTSD: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) | Administered by trained nurse Interpreter present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Eytan (2002) [56] | Screening program | IME assessment Switzerland | In transition | Refugees, median age 24 yo 72% male Kosovo |

MDD and PTSD: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) | Administered by trained nurse Interpreter present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Geltman (2005) [57] | Screening program | Unaccompanied Refugee Minors Program (URMP) sites USA |

Post-arrival | Refugee minors, mean age 17.6 yo 84% male Sudan |

PTSD: Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) and Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ) | Administered by staff Interpreter not present Oral interview and self-assessment Assessment time not reported |

| Green (2021) [58] | Screening program | Primary care “office” USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees, age 4–18 yo 56% male Bhutan, Burma, Democratic Republic of Congo/Burundi, Iraq, Somalia |

PTSD, depression, trauma: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) | Administered by interpreters Interpreter present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Hanes (2017) [59] | Screening program | Hospital refugee health service Australia |

Post-arrival | Refugees Age 2–16 yo mean age 9.4 yo 49% male Top 7 countries: Burma, Afghanistan, Sudan, Ethiopia Congo, Somalia, Iran |

Adverse childhood experiences: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) | Interpreter present Self-administered Assessment time not reported |

| Hauff (1995) [60] | Screening program | n/a Norway |

Post-arrival | Refugees Age over 15 yo 79% male Vietnam |

Psychiatric disorders: Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90) and Present State Examination (PSE) | Researcher Interpreter present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Heenan (2019) [61] | Screening program | Specialist immigrant health service within a children’s hospital Australia |

Post-arrival | Refugee children Age 7 months to 16 years old 64.8% male Syria, Iraq |

Mental health (including PTSD) and development screening was conducted, but no assessment tool is described | Refugee health program nurses Primary care health assessment Assessment time not reported |

| Hirani (2018) [62] | Screening program | Tertiary refugee health service Australia |

Post-arrival | Adolescent refugees Age 12–17 years old (mean age 14; 49% male) 15 countries (Middle East, Africa, Asia) |

Psychosocial assessment: Home, Education/Eating, Activities, Drugs, Sexuality, Suicide/mental health’ (HEADSS) Questionnaire | Interviewer Interpreter present Oral interview 25–60 min |

| Hobbs (2002) [63] | Screening program | Public health hospital New Zealand |

Post-arrival | Asylum seekers Age 0–60+ years old 68.1% male Middle Eastern countries |

Symptoms, or history of symptoms, of psychological illness: Auckland Public Health Protection Asylum Seekers Screening | Clinic staff Health screening Assessment time not reported |

| Hocking (2018) [64] | Validation study | Asylum seeker welfare centre Australia |

Post-arrival | Refugees 19–82 yo, median age 33 69.8% male Mostly from countries in Africa and Asia |

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Mental Health Screening Tool for Asylum seekers and Refugees (STAR-MH) | Administered by trained non-mental health workers Interpreter present Oral interview 6 min |

| Hollifield (2013) [65] | Validation study | Public health centre USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Age over 14 yo 50% male Bhutan, Burma, and Iraq |

Anxiety, depression, PTSD: Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15) | Administered by physicians or public health clinic staff Interpreter present Oral interview 4–12 min |

| Hollifield (2016) [66] | Validation study | Public health centre USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Age over 14 yo 50% male Bhutan, Burma, and Iraq |

Anxiety and depression: Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25 (HSCL-25) PTSD: Posttraumatic Symptom Scale- Self Report (PSS-SR) Anxiety, depression, PTSD: Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15) |

Administered by trained public health nurses Interpreter not present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Hough (2019) [39] | Screening program | Refugee clinic Lebanon |

Pre-departure | Refugees 18 years and above 50% male Syria |

General mental health: Global Mental Health Assessment Tool (GMHAT) | Administered by healthcare professionals (psychiatrist, general physician, pediatrician, and two nurses) Administrators served as translators Computerized tool 15–20 min |

| International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2020) [4] |

Screening program | IOM migration health assessment clinics Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan |

Pre-departure | Refugees: majority younger than 30 (67.1%), with the highest number in the under-10 age group 51.2% male |

Not described | Not described |

| Jakobsen (2017) [67] | Validation study | Setting not reported Norway |

Post-arrival | Unaccompanied adolescent asylum seekers Age 15–18 years old (mean: 16.2) 100% male Afghanistan, Somalia |

PTSD, anxiety, and depression: combined Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) and Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ- IV) | Interpreter present Self-administered via laptop computer Assessment duration not reported |

| Javanbakht (2019) [68] | Screening program | Primary care clinic USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Age 18–65 yo 52.9% male Syria |

PTSD: PTSD Checklist Civilian version (PCL-C) Anxiety and depression: Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25 items (HSCL-25) |

Research assistant Interpreter present (research assistant) Self-assessment 20 min (5–10 min per tool) |

| Johnson-Agbakwu (2014) [69] | Screening program | Refugee women’s health clinic with a behavioural health partnership USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Age 18 years and older 100% female Iraq, Burma, Somalia |

Anxiety, depression, PTSD: Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15) | Cultural health navigator (served as interpreter) Oral interview 5–10 min |

| Kaltenbach (2017) [70] | Validation study | Refugee accommodation Germany |

In transition | Refugees Age over 12 yo, median age 28.79 yo Majority from Syria, minority from Afghanistan, Albania, Kosovo, Serbia, Iraq, Macedonia, Somalia, Georgia |

PTSD, depression, anxiety: Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15) Semi-structured interview: PTSD: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5 (PCL-5) Depression: Refugee Health Screener (RHS-15)—only the first 13 questions Trauma exposure: Life Events Checklist (LEC-5) Psychological distress: semi-structured interview via Brief Symptom Inventory -18 |

RHS Self-administered Interpreter present if needed 10–30 min Semi-structured interview by a clinical psychologist Interpreter present Oral interview 90 min |

| Kennedy (1999) [71] | Screening program | Primary care clinic (University Hospital) USA |

Post-arrival | Adult refugees and their children | Depression, anxiety, and PTSD: A set of questions about history of imprisonment, trauma, or torture + a 25-item, self-administered symptom checklist that surveys for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. The checklist was developed by Dawn Noggle, PhD, of the International Rescue Committee in Arizona. In addition, parents are asked standard questions about their children’s adjustment and symptoms of stress or depression |

Administered by nurse or physician Interpreter present Self-assessment symptom checklist Assessment time not reported |

| Kleijn (2001) [72] | Validation study | Psychiatric clinic Netherlands |

Post-arrival | Refugees 81% male Arabic, Farsi, or Serbo-Croatian speaking regions |

PTSD: The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) Depression and Anxiety: Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-25(HSCL-25) |

Administered by psychologist or psychiatrist Interpreter present Self-assessment Assessment time not reported |

| Kleinert (2019) [73] | Screening program | Primary care centre within a reception centre Germany |

Post-arrival | Refugee and asylum seekers median age of all patients was 26 years, SD 18.529 51% of asylum-seeker patients and 49% of resettlement-refugee patients were female Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Georgia, Iran |

Mental and behavioural disorders classified by ICD 10: Digital Communication Assistance Tool (DCAT) | General practitioners and nurses Digital Communication Assistance Tool (DCAT) via tablet No interpreter present Self-assessment Assessment time not reported |

| Kroger (2016) [74] | Screening Program | Reception centre Germany |

Post-arrival | Refugees and asylum seekers Average age 30.5 88.2% male Balkan States, Middle East, Northern Africa, rest of Africa |

PTSD: Post-traumatic Diagnostic Scale-8 (PDS-8) Depression: Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) |

Administered by psychological psychotherapist, medical assistant, or psychology undergraduate students Interpreter present Oral interview 15–90 min |

| LeMaster (2018) [75] | Screening program | Local resettlement agencies USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Mean age 33.4 Iraq |

PTSD: civilian version of the PTSD Checklist (PCL-C) and Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) Depression: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

Administered by a trained Arabic-speaking interviewer Interpreter present Oral interview 120 min |

| Lillee (2015) [76] | Screening program | Humanitarian entrant health service Australia |

Post-arrival | Refugees Age 18–70 48.7% male Africa, South-Eastern and South-Western Asia |

Non-specific psychological distress: The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) PTSD: PTSD treatment screener |

Administered by physicians Interpreter present Oral interview or self-assessment 10–15 min |

| Loutan (1999) [77] | Screening program | University Hospital Switzerland |

Post-arrival | Refugees Median age 27 67% male Yugoslavia, Somalia, Angola, Sri-Lanka |

Physical and psychological symptoms and previous exposure to traumatic events: No name; short questionnaire developed and tested at the Policlinic | Administered by trained nurses (who were multilingual) Interpreter not present Oral interview 15 min |

| Masmas (2008) [78] | Screening program | Reception centre Denmark |

Post-arrival | Asylum seekers, average age 32 years (16–73 years) 71% male Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Chechnya |

PTSD: International Classification of Disease Codes (ICD-10) Overall psychological health: WHO’s General Health Questionnaire |

Administered by trained health care professionals Translator available if needed Oral interview 60 min |

| McLeod (2005) [79] | Screening program | Refugee resettlement centre medical clinic New Zealand |

Post-arrival | Refugees: majority 20–34 years old 53.2% male, 34 different nationalities, majority Iraqi, Somali, Ethiopian |

Psychosocial assessment—screening tool not reported | Administered by trained health care professionals Administration details not reported |

| Mewes 2018 [80] | Validation study | Asylum accommodation or at meeting points for asylum seekers Germany |

Post-arrival | Asylum seekers Aged 18 years and older (M = 31.9 years SD 7.8), 67% male Most participants came from Iran, Afghanistan, Syria, or African countries |

PTSD and depression: Process of Recognition and Orientation of Torture Victims in European Countries to Facilitate Care and Treatment (PROTECT) Questionnaire PTSD: Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) Depression: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9) |

Self-assessment The software ‘MultiCasi’ was used via a laptop with touchscreen Interpreter present Assessment time not reported |

| Morina (2017) [81] | Screening program | Clinical setting outpatient clinic Switzerland |

Post-arrival | Refugees Aged 28–64 (mean 50.07, SD 8.65) 77% male Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Iraq, Turkey, Sudan |

PTSD: Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale based on DSM-5 (PDS) Depression: Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) Quality of Life: EUROHIS-QoL Questionnaire |

Interview with therapist Interpreter present Oral interview Assessed in 24 min or Computer assisted self-interviews using multi-adaptive psychological screening software (MAPSS) Tablet Assessed in 9 min |

| Nehring (2021) [82] | Validation study | Reception camp Germany |

Post-arrival | Refugee children Age 4–14 years (mean: 8.9 years (SD: 2.8)) tijana59.0% male Syria |

PTSD: Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) | Child and adolescent psychiatrists Interpreter and native speaking doctors were present Oral interview with parents and children The duration of all examinations lasted 1–2 days for one family |

| Nikendei (2019) [83] | Screening program | Outpatient clinic Germany |

Post-arrival | Asylum seekers Age over 18 yo Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe |

PTSD: Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5) Depression: Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) General anxiety: Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2) Panic symptoms: PHQ-PD Social well-being: World Health Organization- Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5) Alcohol and drug addiction: three screening questions derived from the screening questions from the SCID (Structured Clinical Interview) |

Research assistant Interpreter available Self-assessment Assessment time not reported |

| Ovitt (2003) [84] | Screening program | Resettlement office or at participants’ homes USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Ages 29–72 yo 50% male Bosnia |

Anxiety and depression: The Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) and a client questionnaire | Psychiatrist or medical doctor Interpreter not present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Polcher (2016) [85] | Screening program | Community health centre USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Ages 18 yo or older tijana41% male Bhutan, Iraq, Somalia, Congo, Sudan, Burma, Iran, and Eritrea |

Anxiety, depression and PTSD: Refugee Health Screener–15 (RHS-15) | Administered by trained interpreters and medical assistants Interpreter present Oral interview 10–15 min |

| Poole (2020) [86] | Validation study | Refugee camp Greece |

In transition | Refugees Mean age 30 years, range 18–61. 59% male Syria |

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): Patient Health Questionnaires (PHQ-2 and PHQ-8) | Administered by research personnel Arabic-English interpreter present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Rasmussen (2015) [87] | Validation study | Primary care clinic USA |

Post-arrival | Asylum seekers Mean age 34.9 yo 59% male West Africa, Himalayan Asia, and Central Africa |

PTSD: Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) | Administered by trained interpreters Interpreter present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Richter (2015) [88] | Screening program | Central reception facilities Germany |

Post-arrival | Asylum seekers Mean age 31.9 years old, SD 10.6 66.8% male Iran, Russia, Afghanistan, and Iraq |

General psychiatric assessment: Structured diagnostic interview MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI-Plus) Essen Trauma Inventory (ETI) Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale (MADRS) WHO-5 Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) |

Administered by a physician Interpreter present Oral interview 3 h (two 1.5 h sessions) |

| Salari (2017) [89] | Validation study | Primary care clinic Sweden |

Post-arrival | Refugees Ages 9–18 97.6% male Majority from Afghanistan. Others from Iran, Syria, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya, and Lebanon |

PTSD: Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-8) | Clinicians and nurses Interpreter present if needed Self-assessment Assessment time not reported |

| Savin (2005) [90] | Screening program | Primary care clinic USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Ages 18 years old and over (mean age 27.4) 51.5% male 24 countries of origin: most frequently Bosnia, Russia, Ukraine, Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Burma, Vietnam, Iran, and Iraq |

PTSD, anxiety, depression: 25-item psychiatric symptom checklist derived from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) |

Administered by a team composed of a case manager from a publicly funded resettlement agency, a primary care nurse experienced with culturally diverse populations, a primary care physician, and if needed, a psychologist or psychiatrist. Nurses primarily administered the screening tool Interpreter present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Schweitzer (2011) [91] | Screening program | Settlement service Australia |

Post-arrival | Refugees Mean age 34.13 yo (range 18–80 yo) 43.9% male Burma |

Pre-migration trauma: HTQ Depression, anxiety, somatization: Hopkins Symptom Checklist-37 (HSCL-37) Post-migration stressors: Post-migration Living Difficulties Checklist |

Researchers and counsellors Interpreter present Oral interview 2–3 h |

| Seagle (2019) [92] | Screening program | Outpatient clinics USA |

Post-arrival | Administrative sample, 64% refugees Age 14 years and older 42.6% male Cuba, Burma, Afghanistan, Bhutan, Iraq, Somalia, Iran, Ethiopia, Syria |

Not reported; however, the authors state that clinicians may consider the use of the Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15), Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ), Vietnamese Depression Scale (VDS), New Mexico Refugee Symptom Checklist 121 (NMRSCL-121), and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25 (HSCL-25) Georgia public health officials recommend use of the RHS-15 |

Administered by clinicians Interpreter present Self-assessment and oral interview Time of assessment was variable |

| Shannon (2015) [93] | Screening program | Primary care clinic USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Mean age 35.27 51.4% male Burma |

PTSD, distress, somatic complaints, depression: unspecified 32-item questionnaire | Administered by trained research staff Interpreter present Self-assessment 45 min |

| Sondergaard (2001) [94] | Screening program | Reception centre Sweden |

Post-arrival | Refugees Ages 18–48, mean age 35 yo 63% male Iraq |

PTSD: Questionnaire developed uniquely for this study, based on the Holmes-Rahe Life Event Questionnaire | Assessor background not reported Interpreter not present Self-assessment Assessment duration not reported |

| Sondergaard (2003) [95] | Validation study | Reception centre Sweden |

Post-arrival | Refugees Ages 18–48, mean age 35 yo 63% male Iraq |

Mental health screen using Health Leaflet: Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ), Impact of Event Scale (IES-22), General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28), Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL-25) PTSD: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID) or Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS) Depression: Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL-25) |

Administered by case manager Interpreter not present Self-assessment Assessment time not reported |

| Stingl (2019) [96] | Screening program | Reception centre (RC) & communal accommodation (CU) Germany |

Post-arrival | Refugees Mean age 25.6 (RC), 28.9 (CU) 92.9% (RC), 69.8% (CU) male Afghanistan, Algeria, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Iraq, Iran, Somalia, Syria |

Depression, anxiety, and PTSD: Refugee Health Screener (RHS-15) | Administered by doctorate students and a linguist Interpreter present Written Likert-scale 4–12 min |

| Sukale (2017) [97] | Screening program | Clearing and pre-clearing institution Germany |

Post-arrival | Refugee minors Age 16.24 years, SD 1.03 100% male Syria, Afghanistan, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Iraq |

Providing Online Resource and Trauma Assessment (PORTA) screening tool, which comprises of disorder-specific questionnaires: Trauma: CATS Depression and Anxiety: Refugee Health Screener (RHS-15) + Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) Behavioural problems: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire Self harm and suicidality: SITBI |

Self-administered Interpreter present if needed Online questionnaire via computer (PORTA) 30–90 min |

| Tay (2013) [98] | Screening program | Reception centre Australia |

In transition | Asylum seekers Mean age 39 65% male 18 countries- majority from Iran, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Afghanistan, and China |

PTSD and depression: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) PTSD: Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) Depression: Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL-25) |

Assessment by psychologists Interpreter present Oral interview 120 min |

| Thulesius (1999) [99] | Validation study | Asylum centre (refugees) and Healthcare clinic (Swedish comparison group) Netherlands |

Post-arrival | Refugees Mean age 33.7 58% male Bosnia-Herzegovina |

PTSD and depression: Modified Posttraumatic Symptom Scale (PTSS-10-70) | Assessor background not reported Interpreter not present Self-assessment Assessment time not reported |

| van Os (2018) [100] | Screening program | National intermediary organizations Netherlands |

Post-arrival | Refugees and asylum seekers—16 unaccompanied children (15–18 years) and 11 accompanied children (4–16 years) 63% male 44% from Afghanistan |

Well-being and child development: Best Interests of the Child (BIC-Q), Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) Stressful life events: Stressful Life Events (SLE) PTSD: Reactions of Adolescents on Traumatic Stress (RATS) |

Assessment by trained professionals Interpreter present Self-assessment and oral interview 180–240 min |

| Van Dijk (1999) [101] | Validation study | Psychiatric hospital Netherlands |

Post-arrival | Refugees Mean age 35.7 years, range 17–70 67% male Diverse nationalities (country not specified) |

PTSD: Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ), Hopkins Symptom Check List-90 (HSCL-90), DSM-IV |

Administered by psychiatrists and psychological assistants Interpreter present Oral interview Assessment time not reported |

| Vergara (2003) [102] | Screening program | Refugee health program USA |

Post-arrival | 26,374 refugees, or 38.1% of all refugees, resettling in the United States during fiscal year 1997 No additional characteristics reported |

3/9 sites offered mental status examinations during the domestic refugee health assessment. Specific mental health conditions and assessment tools not reported | Not reported |

| Weine (1998) [103] | Screening program | Primary care clinic USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Ages 13–59 yo 50% male Bosnia |

PTSD: PTSD Symptoms Scale, the Communal Traumatic Experiences Inventory, the Global Assessment of Functioning (DSM-IV), and the Symptoms Checklist 90 (SCL-90-R) |

Administered by mental health professionals Interpreter present Oral interview 60–120 min |

| Willey (2020) [104] | Screening program | Refugee antenatal clinic Australia |

Post-arrival | Women from a refugee background or considered refugee-like, i.e., arrived in Australia on a spousal visa from a refugee-source country such as Afghanistan | Depression and anxiety: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Perinatal mental health: Monash Psychosocial Screening Tool |

Administered by maternal care staff (midwives, bi-cultural workers) Interpreter present Electronic tablet 10 min |

| Wulfes (2019) [105] | Validation study | Refugee accommodations Germany |

Post-arrival | Refugee and asylum seekers Ages 17–90 yo, average age 32.9 64.4% male Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, Sudan |

1. Posttraumatic stress screening: PQ 2. Traumatic events: a list of events that was modified from those included in the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) 3. Posttraumatic stress symptoms: PDS-8 4. Depression: Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) 5. Axis I disorders: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID) |

Administered by staff without medical or psychological health training I nterpreter not present Self-assessment Assessment time not reported |

| Yalim (2021) [106] | Screening program | Refugee resettlement agency/home visit USA |

Post-arrival | Refugees Aged 18 years and older (mean age 36.38 years, SD 12.5) Majority from Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Syria, and Eritrea |

PTSD, depression, anxiety: Refugee Health Screener (RHS-15) | Administered by research personnel Interpreter present Oral interview or self-assessment, depending on the literacy level of the participant 20–30 min |

| Young (2016) [107] | Screening program | Detention centres Australia |

Post-arrival | Asylum seekers and refugees (detainees) All ages 73% male |

Depression, anxiety, and PTSD: Self-rated Kessler 10 (K-10) The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) The Clinician-rated Health of the Nation Outcome Scores (HoNOS) The Clinician-rated Health of the Nation Child and Adolescent Outcome Scores (HoNOSCA) |

Administered by mental health professionals (nurse or psychologist) Interpreter present Self-assessment Assessment time not reported |

Figure 3.

Timing of mental health assessments.

Figure 4.

Global distribution of mental health assessments for refugees and asylum seekers according to setting of screening. To note: we identified one publication on pre-departure screening conducted in Lebanon prior to departure to the UK.

Figure 5.

Setting of mental health assessments.

11. Conditions and Mental Health Screening Tools

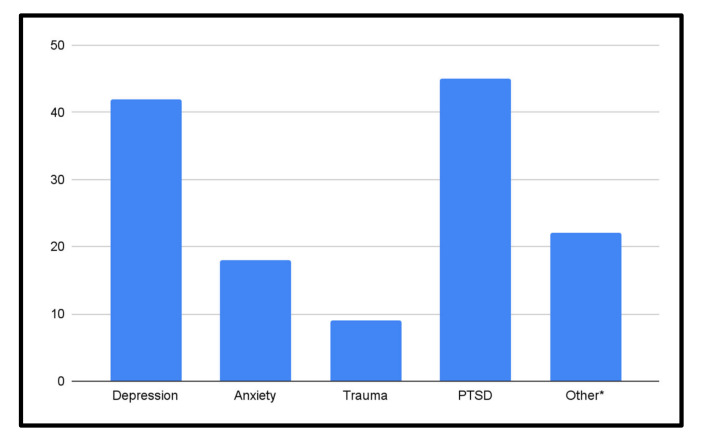

A total of 85 mental health screening tools were identified (Table 3). Several of these tools are available in multiple languages and are either self-administered or administered by various trained professionals such as primary care providers (PCPs), mental health specialists (MHSs), or community health workers (CHWs). Several tools could also be administered by a lay person without clinical training [46,64,80]. The most common tools were the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ), the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25), the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), and the Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15). The most common screened mental health conditions were overall mental health, PTSD, depression, and anxiety (see Figure 6).

Table 3.

Mental Health Screening Tool Characteristics.

| Screening Tool | Studies | Mental Health Conditions Assessed | Administrator | Languages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Family Peer Relationship Questionnaire, Arabic version (A-FPRQ) | El Ghaziri 2019 | OTHER | unspecified | unspecified |

| 2 | Unaccompanied Migrant Minors Questionnaire (AEGIS-Q) | Di Pietro 2020 | OTHER | unspecified | unspecified |

| 3 | Al-Obaidi et al. DSM-based non-validated questionnaire | Al-Obaidi 2015 | Depression, PTSD | Master’s level social worker | unspecified |

| 4 | Arab Acculturation Scale | LeMaster 2018 | PTSD, Depression, OTHER | unspecified | unspecified |

| 5 | Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) | El Ghaziri 2019 | Substance Use Disorder | unspecified | unspecified |

| 6 | Best Interests of the Child (BIC-Q) | van Os 2018 | Disruptive Behaviour Disorders, Depression | unspecified | Arabic, Dari, Farsi, Somali |

| 7 | Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) | Kaltenbach 2017 Richter 2015 |

Depression, PTSD, Somatoform Disorders | unspecified | Albanian, Arabic, Farsi, Kurdish, Russian, Serbian, Somali |

| 8 | Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) | Nehring 2021 | PTSD | MHS | German |

| 9 | Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ) | Geltman 2005 | OTHER | Community health worker (CHW) | English |

| 10 | Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-8) | Salari 2017 | PTSD | Primary care provider (PCP) | Arabic, Dari, Farsi, Kurdish/Sorani, Swedish |

| 11 | Communal Traumatic Experiences Inventory (CTEI) | Weine 1998 | PTSD, Depression | Mental health specialist (MHS), PCP, lay person (LAY) | Croatian |

| 12 | Cook et al. author-developed interview | Cook 2015 | OTHER | Research assistants trained Master’s or Ph.D. level social work students | unspecified |

| 13 | Digital Communication Assistance Tool (DCAT) | Kleinert 2019 | PTSD, Depression, Anxiety, Substance Use Disorder, Disruptive Behaviour Disorders, Somatoform Disorders, OTHER | Self-assessment, PCP | Modern Standard Arabic, Arabic Syrian, Arabic Egyptian, Arabic Tunisian, Arabic Moroccan, Turkish, Persian, Kurdish Sorani, Kurdish Kurmanji, Kurdish Feyli, Pashto Kandahari, Pashto Mazurka |

| 14 | Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) | Boyle 2019 Willey 2020 |

Depression | MHS, PCP, CHW, LAY | unspecified |

| 15 | Essen Trauma Inventory (ETI) | Richter 2015 | Trauma | MHS | German |

| 16 | Eytan et al. (2002) author-developed interview | Eytan 2002 | Health Conditions, Presence of Symptoms and Previous Exposure to Trauma | Nurses | French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, English |

| 17 | Family Assessment Device (FAD) | El Ghaziri 2019 | OTHER | unspecified | unspecified |

| 18 | Geltman et al. author-developed ad-hoc assessment | Geltman 2005 | Emotionally Traumatic Exposures | Staff from local URMO agencies | English |

| 19 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) | Bjarta 2018 | Anxiety | MHS, PCP, CHW | Arabic, Dari |

| 20 | GB | El Ghaziri 2019 | OTHER | unspecified | unspecified |

| 21 | General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) | Sondergaard 2003 | Depression | Self-rating | unspecified |

| 22 | Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (DSM-IV) |

Weine 1998 | OTHER | MHS, PCP, CHW | Croatian |

| 23 | Global Mental Health Assessment Tool (GMHAT) | Hough 2019 | Anxiety, Depression, Substance Use Disorders, Disruptive Behaviour Disorders | PCP, MHS | English, Arabic |

| 24 | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Arnetz 2014 LeMaster 2018 |

Anxiety, Depression | CHW | Arabic |

| 25 | Hassles Scale | LeMaster 2018 | OTHER | CHW | unspecified |

| 26 | Home, Education/Eating, Activities, Drugs, Sexuality, Suicide/mental health (HEADSS) Questionnaire | Hirani 2016 | OTHER | unspecified | English |

| 27 | Health Leaflet (HL) | Sondergaard 2003 | PTSD | Self-assessment | unspecified |

| 28 | Kennedy et al. author-developed tool | Kennedy 1999 | Depression, Anxiety, PTSD | Self-assessment | unspecified |

| 29 | Clinician-rated Health of the Nation Outcome Scores (HoNOS) | Young 2016 | Depression, Substance Use Disorders, Disruptive Behaviour Disorders | MHS, PCP | unspecified |

| 30 | Clinician-rated Health of the Nation Child and Adolescent Outcome Scores (HoNOSCA) | Young 2016 | Depression, Substance Use Disorders, Disruptive Behaviour Disorders | MHS, PCP | unspecified |

| 31 | Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) | Jakobsen 2017 Javanbakht 2019 Kleijn 2001 Ovitt 2003 Schweitzer 2011 Sondergaard 2003 Tay 2013 Van Dijk 1999 |

Anxiety, Depression | MHS, PCP, CHW | Arabic, Farsi, Russian, Bosnian-Serbo-Croatian |

| 32 | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) | Arnetz 2014 Bertelsen 2018 Churbaji 2020 Geltman 2005 Jakobsen 2017 Kleijn 2001 LeMaster 2018 Rasmussen 2015 Schweitzer 2011 Sondergaard 2003 Tay 2013 Young 2016 Van Dijk 1999 |

PTSD | MHS, PCP, CHW | Arabic, Cambodian, Dutch, English, Farsi, French, Laotian, Russian, Serbo-Croatian, Vietnamese |

| 33 | Impact of Event Scale (IES-22) | Sondergaard 2003 | Trauma | Self-rating | unspecified |

| 34 | Interpersonal Support Evaluation Checklist (ISEL) | LeMaster 2018 | OTHER | CHW | unspecified |

| 35 | ICD-11 International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) | Barbieri 2019 | PTSD | MHS, PCP, CHW | Arabic, English, French |

| 36 | Kaltenbach et al. author-developed questionnaire | Kaltenbach 2017 | Daily Functioning | Clinical psychologists | unspecified |

| 37 | Karen Mental Health Screener | Brink 2016 | PTSD, Depression | PCP | Karenic |

| 38 | Self-rated Kessler 10 (K-10) | Lillee 2015 Young 2016 |

OTHER | Self-administered (SA) | English, Kurdish, Pashto |

| 39 | Life Events Checklist (LEC-5) | Kaltenbach 2017 | OTHER | unspecified | Arabic, Albanian, Farsi, Kurdish, Russian, Serbian, Somali |

| 39 | Loutan et al. author-developed questionnaire | Loutan 1999 | Anxiety, Depression, PTSD, and Traumatic Events | Nurse | French, English, Italian, Spanish and German |

| 40 | Multi-Adaptive Psychological Screening Software (MAPSS) | Morina 2017 | Depression, PTSD | MHS, PCP | Arabic, Farsi, Tamil, Turkish |

| 41 | Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) | Churbaji 2020 Durieux-Paillard 2006 El Ghaziri 2019 Eytan 2007 Kaltenbach 2017 Richter 2015 |

Depression, Anxiety, Substance Use Disorders, Disruptive Behaviour Disorders, PTSD, Somatoform Disorders | MHS, PCP | 70+ languages |

| 42 | Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID) | El Ghaziri 2019 | Depression, Anxiety, Substance Use Disorders, Disruptive Behaviour Disorders, PTSD, Somatoform Disorders | MHS, PCP | 70+ languages |

| 43 | Monash Health Psychosocial Needs Assessment (Psychosocial Screening Tool) | Boyle 2019 Willey 2020 |

OTHER | MHS, PCP, CHW, LAY, Self-administered | unspecified |

| 44 | Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale (MADRS) | Richter 2015 | Depression | MHS, PCP | unspecified |

| 45 | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | El Ghaziri 2019 | OTHER | MHS, PCP, CHW | unspecified |

| 46 | Nikendei et al. author-developed interviews | Nikendei 2019 | Substance Use | Research personnel | English, German, French, Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish), Urdu, Hausa, Russian, Serbian, Albanian, Macedonian, Georgian, Mandinka, Tigrinya |

| 47 | Ovitt et al. author-developed client questionnaire | Ovitt 2003 | OTHER | ||

| 48 | Primary Care PTSD-4 (PC-PTSD-4) | Bjarta 2018 | PTSD | MHS, PCP, CHW, LAY, SA | Arabic, Dari |

| 49 | PC-PTSD-5 | Nikendei 2019 | PTSD | Trained research assistants | English, German, French, Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish), Urdu, Hausa, Russian, Serbian, Albanian, Macedonian, Georgian, Mandinka, Tigrinya |

| 50 | PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) | Barbieri 2019 Kaltenbach 2017 |

PTSD | MHS, PCP | Arabic, Albanian, Farsi, Kurdish, Russian, Serbian, Somali |

| 51 | Civilian version of the PTSD Checklist (PCL-C) | Arnetz 2014 Javanbakht 2019 LeMaster 2018 |

PTSD | CHW | Arabic |

| 52 | Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) | Kroger 2016 Mewes 2018 Wulfes 2019 |

PTSD | MHS, Self-assessment | German, Arabic, Persian, Kurdish, Turkish, English |

| 53 | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) | Kroger 2016 Nikendei 2019 Poole 2020 |

Depression | Trained research assistants | English, German, French, Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish), Urdu, Hausa, Russian, Serbian, Albanian, Macedonian, Georgian, Mandinka, Tigrinya |

| 54 | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) | Poole 2020 | Depression | Research personnel | |

| 55 | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) | Bertelsen 2018 Bjarta 2018 Churbaji 2020 Mewes 2018 Wulfes 2019 |

Depression | MHS, PCP, Self-assessment | Arabic, Dari, Farsi, English, Kurdish |

| 56 | Patient Health Questionnaire—Panic Disorders (PHQ-PD) | Nikendei 2019 | Panic Symptoms | Trained research assistants | English, German, French, Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish), Urdu, Hausa, Russian, Serbian, Albanian, Macedonian, Georgian, Mandinka, Tigrinya |

| 57 | Parentification Inventory (PI) | El Ghaziri 2019 | OTHER | MHS, PCP, CHW | unspecified |

| 58 | Post-Migration Living Difficulties Checklist (PMLDC) | Schweitzer 2011 | OTHER | CHW | unspecified |

| 59 | Process of Recognition and Orientation of Torture Victims in European Countries to Facilitate Care and Treatment (PROTECT) Questionnaire | Mewes 2018 Wulfes 2019 |

PTSD, Depression | MHS, PCP, LAY | English, German, Farsi, French, Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Kurdish, Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish), Urdu, Hausa, Russian, Serbian, Albanian, Macedonian, Georgian, Mandinka, Tigrinya |

| 60 | Present State Examination (PSE) | Hauff 1995 | PTSD, psychiatric disorders | The first author | unspecified |

| 61 | Providing Online Resource and Trauma Assessment’ (PORTA) | Sukale 2017 | Trauma, Depression, Anxiety, Behavioural Problems, Self- Harm/Suicidality | Self-administered | German, English, French, Arabic, Dari/Farsi, Pashto, Tigrinja, Somali |

| 62 | PTSD Symptoms Scale (PSS) | Weine 1998 | PTSD | MHS, CHW, LAY | Croatian |

| 63 | Posttraumatic Symptom Scale (PTSS-10-70) | Thulesius 1999 | PTSD | unspecified | English, Serbo-Croatian |

| 64 | Reactions of Adolescents on Traumatic Stress (RATS) | van Os 2018 | PTSD | unspecified | Arabic, Dari, Farsi, Somali |

| 65 | Resilience Scale | LeMaster 2018 | OTHER | CHW | unspecified |

| 66 | Refugee Health Screener-13 (RHS-13) | Bjarta 2018 Kaltenbach 2017 |

Depression, Anxiety, SOM, PTSD, OTHER | MHS | Amharic, Arabic, Albanian, Burmese, Cuban Spanish, Farsi, French, Haitian Creole, Karen, Kurdish, Mexican Spanish, Nepali, Russian, Spanish, Serbian, Somali, Swahili, Tigrinya |

| 67 | Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15) | Al-Obaidi 2015 Baird 2020 Hollifield 2013 Hollifield 2016 Johnson-Agbakwu 2014 Kaltenbach 2017 Polcher 2016 Stingl 2019 Yalim 2020 |

Depression, Anxiety, Somatoform Disorders, PTSD, OTHER | MHS, PCP, CHW | Amharic, Arabic, Albanian, Burmese, Cuban, English, Farsi, French, Haitian Creole, Karen, Kurdish, Mexican Spanish, Nepali, Russian, Spanish, Serbian, Somali, Swahili, Tigrinya |

| 68 | Refugee Trauma History Checklist (RTHC) | Sigvardsdotter 2017 | OTHER | MHS, PCP | English, Arabic |

| 69 | Savin et al. author-developed checklist derived from the DSM-IV | Savin 2005 | Depression, Anxiety, PTSD | PCP, MHS | English |

| 70 | S-DAS | El Ghaziri 2019 | Disruptive Behaviour Disorders, OTHER | MHS, PCP, CHW | unspecified |

| 71 | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) | Brink 2016 Tay 2013 Wulfes 2019 |

Depression, Anxiety, PTSD, Substance Use Disorders, Disruptive Behaviour Disorders, Somatoform Disorders | MHS, PCP | Danish, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Karen, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, Zulu |

| 72 | SCL-90-R | Hauff 1995 Weine 1998 |

Depression, Anxiety, Somatoform Disorders, Disruptive Behaviour Disorders, OTHER | MHS, PCP, CHW | Croatian |

| 73 | Strength and Difficulty Questionnaire (SDQ) | Green 2021 Hanes 2017 van Os 2018 |

OTHER | CHW, LAY | 75+ languages |

| 74 | SF-10 | El Ghaziri 2019 | Depression, Anxiety, Disruptive Behaviour Disorders | MHS, PCP, CHW | unspecified |

| 75 | SF-12 | El Ghaziri 2019 | Depression, Anxiety, Disruptive Behaviour Disorders | MHW, PCP, CHW | unspecified |

| 76 | Shannon et al. author-developed questionnaire | Shannon 2015 | Depression, PTSD, OTHER | Master’s-level and doctoral-level research assistant, professional Karen interpreters | English and Karen |

| 77 | Stressful Life Events (SLE) | van Os 2018 | OTHER | unspecified | Arabic, Dari, Farsi, Somali |

| 78 | Sondergaard et al. (2001) author-developed questionnaire | Sondergaard 2001 | PTSD, Anxiety, Depression, OTHER | Professionals working with refugees | Arabic and Sorani |

| 79 | STAR-MH | Hocking 2018 | Depression, PTSD | CHW | English |

| 80 | Trauma Exposure Questionnaire by Nickerson et al. | Barbieri 2019 | PTSD | PCP | Arabic, English, French |

| 81 | Vietnamese Depression Scale (VDS) | Buchwald 1995 | Depression | PCP | Vietnamese |

| 82 | WHO-5 | Nikendei 2019 Richter 2015 |

Social Well-Being | LAY, MHS, PCP | English, German, French, Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish), Urdu, Hausa, Russian, Serbian, Albanian, Macedonian, Georgian, Mandinka, Tigrinya |

| 83 | WHO General Health Questionnaire | Masmas 2008 | Psychological Health Status | PCP, MHS | unspecified |

| 84 | World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version (WHOQOL-Bref) | Bjarta 2018 | OTHER | MHS, PCP, CHW, LAY, SA | 28 languages (who.int) |

| 85 | World Health Organization PTSD screener | Lillee 2015 | PTSD | unspecified | English, Kurdish, Pashto |

Legend: PCP: Primary care provider. MHS: Mental health specialist. CHW: Community health worker. LAY: Layperson. SA: Self-administration.

Figure 6.

Overview of mental health conditions assessed among refugees and asylum seekers. * NB: Any mental health assessments that did not include depression, anxiety, trauma, or PTSD were categorized as ‘Other’ (e.g., general mental health, panic disorders, adverse childhood events, etc.)

12. Pre-Departure Mental Health Screening

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) conducts several pre-migration health activities at the request of receiving country governments to identify health conditions of public health importance and to provide continuity of care linking the pre-departure, travel, and post-arrival phases. These assessments include radiology services, laboratory services, treatment of communicable diseases, vaccinations, and detection of non-communicable diseases, including mental health assessments. We identified two grey literature reports which evaluated pre-departure screening programs for refugees [4,39].

In 2019, IOM conducted a total of 110,992 pre-departure health assessments for refugees [4]. Most assessments among refugees were conducted in Lebanon (11.7%), Turkey (11.1%), and Jordan (8.8%). The top destination countries were the United States (39.7%), Canada (27.9%), and Australia (14.6%). In total, 48.8 percent of assessments were conducted among females and 51.2 percent among males. The majority of health assessments were among refugees younger than 30 (67.1%), with the highest number in the under-10 age group. During 2019, mental health conditions were identified in 2249 pre-departure health assessments conducted among refugees (2.0%). Where indicated, refugees were referred to a specialist for further evaluation (1%). The report does not provide any further details on the specific conditions assessed or other administration details [4].

In 2016–2017, IOM collaborated with Public Health England (UK) to evaluate the pre-departure administration of the Global Mental Health Assessment Tool (GMHAT) among 200 Syrian refugees in a refugee camp in Lebanon [39]. These refugees had already been accepted for resettlement to the UK. This clinically validated, computerized assessment tool was administered by a range of healthcare staff and was designed to detect common psychiatric disorders and serious mental health conditions within the time span of 15–20 min [39].

Findings suggested that a pre-departure mental health assessment could be a useful tool to assist in the preparation for refugee arrivals to overseas resettlement facilities and serve as a valuable resource for general practitioners. Other potential benefits included overcoming barriers such as trust and language, expediting referral and treatment, increasing awareness of mental health issues, and improving support and integration of refugees by proactively addressing concerns [39].

Several considerations were identified to improve the impact and roll out of pre-departure mental health assessments [39]. Firstly, the GMHAT identified 9% of participants with a likely diagnosis of mental illness and an additional 1.5% of participants were referred post-arrival based on clinical judgment; as such, it was noted that the pre-arrival assessment should not be used in isolation or as a replacement for routine psychological assessments post-arrival, and that practitioners should use their clinical expertise to pick up on any missed diagnoses. Secondly, the use of the tool was deemed appropriate, but it was noted that participants’ cases took longer to process than those who had not undergone an assessment. Though it was not possible to distinguish whether the GMHAT was the cause of the delay, this is an important consideration. An evaluation of the program indicated that additional information is needed to estimate the impacts on costs and case processing times. Further, the authors concluded it is important to ensure that the information obtained from the pre-assessment will not lead to the rejection of vulnerable refugees based on their mental health status nor based on the resettlement country’s service availability. Clear parameters should be defined to determine the flow of information sharing, and usage should be defined a priori, as it was noted that some healthcare workers in this pilot study were unsure on how the information was intended to be used and whom it could be shared with, ultimately devaluing the purpose of this tool. Lastly, it is important to ensure adequate post-arrival mental health service delivery, since pre-departure assessments can also pose a risk of raising expectations of the care that refugees hope to receive upon resettlement. Although not unique to pre-departure screening procedures, several other concerns were raised including the risk of re-traumatization during assessments, the increased need for mental health services upon arrival, additional guidance and training for healthcare workers, and an increase in the provision of culturally appropriate services. This pilot study acknowledges concerns regarding the acceptability of screening for refugees but recommends that the GHMAT tool requires further modifications to be appropriate for use in the resettlement context [39].

13. Mental Health Screening for Survivors of Torture

We identified four studies which described screening approaches and tools for survivors of torture [45,78,80,105]. Masmas and colleagues identified a high prevalence of torture survivors among an unselected population of asylum seekers using the WHO’s General Health Questionnaire and a clinical interview conducted by physicians [78]. Mewes and colleagues conducted a validation study among adult asylum seekers in Germany. They used the Process of Recognition and Orientation of Torture Victims in European Countries to Facilitate Care and Treatment (PROTECT) Questionnaire, which identifies symptoms of PTSD and depression and categorizes asylum seekers into risk categories, supporting a two-stage approach to mental health screening [80]. The questionnaire was specially developed to be administered by nonmedical/psychological staff for the early identification of asylum seekers who suffered traumatic experiences (e.g., experiences of torture). The tool was administered directly in refugee reception centres and refugee accommodations. The validity of the PROTECT Questionnaire was confirmed by Wulfes and colleagues, who concluded that the use of the PROTECT Questionnaire could be more efficient than other brief screening tools (eight-item short-form Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS-8) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)) because it detects two conditions at once [105].

Among included studies, most community-based programs were not offered specifically for victims of torture. In New York, USA, a hospital-based Program for Survivors of Torture (PSOT) exists to offer services to clients who experienced torture [45]. Referrals to this program typically came from asylum lawyers, other health care professionals when they learned about these clients’ trauma histories, and word-of-mouth in the communities. At PSOT, asylum seekers were screened for PTSD with the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) screening was conducted with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). If a client screened positive for MDD or PTSD at intake, they were referred for a mental health evaluation and management through PSOT. Severe cases were evaluated urgently by a PSOT psychologist or psychiatrist. Of those clients diagnosed with depression and PTSD, 94% received follow-up, defined as either referral to a psychiatrist, psychologist, or support group, or pharmacologic management by a primary care provider [45]. The high follow-up rate was attributed to the unique multidisciplinary medical home structure of the program, which has significantly more allied health professionals, live interpreters, and support staff than an average primary care clinic in the area [45].

14. Mental Health Screening Approaches for Refugee Women

Three publications described two mental health screening programs specifically for refugee women of reproductive age [47,69,104]. The report by Boyle and colleagues is a protocol for a screening program [47] whose acceptability and feasibility has been evaluated [104], but whose effectiveness (outcome) data are not yet available. Boyle et al. conducted their study in a Refugee Antenatal Clinic in Australia [47], while Johnson-Agbakwu et al. conducted their study in a Refugee Women’s Health Clinic in the United States [69]. Both studies screened for mental health conditions post-arrival in a clinic specifically aimed at assessing and treating refugee women. Boyle et al. screened pregnant women in the perinatal and postnatal period at their first appointment, with screening repeated in the third trimester [47]. Johnson-Agbakwu et al. recruited women seeking obstetric and/or gynaecological care, not differentiating between pregnant and non-pregnant women [69]. The purpose of the screening programs was to improve resettlement and integration outcomes [69], and to identify the urgent needs of refugee women for referral to ensure continuity of care [47].

In the USA, Johnson-Agbakwu et al. administered the Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15) with a cultural health navigator to screen women for PTSD, depression, and anxiety [69]. The aim was for women to complete the screening independently and confidentially without the presence of spouses, family members, or friends, as this may influence patient responses. However, this was difficult to enforce. In contrast, Boyle et al. have planned to use the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to assess depression and anxiety in the perinatal period [47]. In addition, Boyle et al. will use the Monash Health psychosocial needs assessment tool to assess perinatal mental health disorders, such as past birthing experiences, violence and safety, and social factors (finances and housing). Women will complete both assessments on a tablet in their chosen language and interpreters or bicultural workers are available to assist.

The Refugee Women’s Health Clinic where Johnson-Agbakwi et al. conducted their study employed multilingual cultural health navigators; program managers skilled in social work who reflected the ethnic and cultural diversity of the patient population and helped with the administration of the screening tool [69]. They were all female, which helped to build strong rapport and trusting relationships for refugee women to feel more comfortable discussing sensitive concerns in their native language. The implementation of their program was dependent on a community-partnered approach and a sustainable interdisciplinary model of care, which was necessary to build trust, empower refugees towards greater receptivity to mental health services, and provide bi-directional learning. Johnson-Agbakwu et al. reported that interdisciplinary models of care, gender-matched multi-disciplinary health care providers, and patient health navigators and interpreters are necessary for integrated approaches and community empowerment [69].

Prior to the implementation of a screening program in Australia, little support was offered to refugee women as midwives were unsure of what services were available [104]. Following the implementation, midwives expressed they were now making more referrals using a co-designed referral pathway than before the screening program, and more information was available at the point of referral because of screening [104]. Finally, it was reported in the USA that while screening for mental health disorders amongst refugee women provides greater awareness and identifies those who need treatment, many women still do not enroll in mental health care [69]. This was either due to women declining care or a lack of health insurance [69]. It was speculated that one reason women may decline care is due to the social stigma of mental health which could be introduced via social desirability bias and may be heightened through the verbal administration of questionnaires [69].

15. Mental Health Screening Approaches for Refugee Children and Adolescents

Eleven studies were identified that investigated mental health screening approaches specific to refugee children and adolescents [52,57,58,59,61,62,67,82,89,97,100]. Children and adolescents between the ages of 6 months to 18 years old were included and all identified screening programs were completed post-arrival to the resettlement country. All studies included adolescent populations (ages 10–18) and fewer studies included children below the age of 10 [58,59,82,89,100]. The programs reported that there is variability in the timing of presentations of mental health disorders; thus, an early assessment of the psychological needs of children and families allows for timely targeted support [58,59].

Children and adolescent screening programs focused on a wider range of conditions which consider critical developmental stages. The psychological factors screened for included: emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems and prosocial behavior, stressful life events, PTSD [82,100], anxiety, depression [58,59,67,97], and somatization disorder [58]. Health risk behaviours, health-related quality of life, and physical and psychosocial well-being, including physical functioning, body pain, emotional problems, self-esteem, and family cohesion were also screened for [57,62]. The most common mental health condition screened for was PTSD, as 10/11 identified studies included a questionnaire which screened for it.