Abstract

Aims

Neutrophil trafficking within the vasculature strongly relies on intracellular calcium signalling. Sustained Ca2+ influx into the cell requires a compensatory efflux of potassium to maintain membrane potential. Here, we aimed to investigate whether the voltage-gated potassium channel KV1.3 regulates neutrophil function during the acute inflammatory process by affecting sustained Ca2+ signalling.

Methods and results

Using in vitro assays and electrophysiological techniques, we show that KV1.3 is functionally expressed in human neutrophils regulating sustained store-operated Ca2+ entry through membrane potential stabilizing K+ efflux. Inhibition of KV1.3 on neutrophils by the specific inhibitor 5-(4-Phenoxybutoxy)psoralen (PAP-1) impaired intracellular Ca2+ signalling, thereby preventing cellular spreading, adhesion strengthening, and appropriate crawling under flow conditions in vitro. Using intravital microscopy, we show that pharmacological blockade or genetic deletion of KV1.3 in mice decreased neutrophil adhesion in a blood flow dependent fashion in inflamed cremaster muscle venules. Furthermore, we identified KV1.3 as a critical component for neutrophil extravasation into the inflamed peritoneal cavity. Finally, we also revealed impaired phagocytosis of Escherichia coli particles by neutrophils in the absence of KV1.3.

Conclusion

We show that the voltage-gated potassium channel KV1.3 is critical for Ca2+ signalling and neutrophil trafficking during acute inflammatory processes. Our findings do not only provide evidence for a role of KV1.3 for sustained calcium signalling in neutrophils affecting key functions of these cells, they also open up new therapeutic approaches to treat inflammatory disorders characterized by overwhelming neutrophil infiltration.

Keywords: KV1.3, Neutrophils, Calcium signalling, Acute inflammation

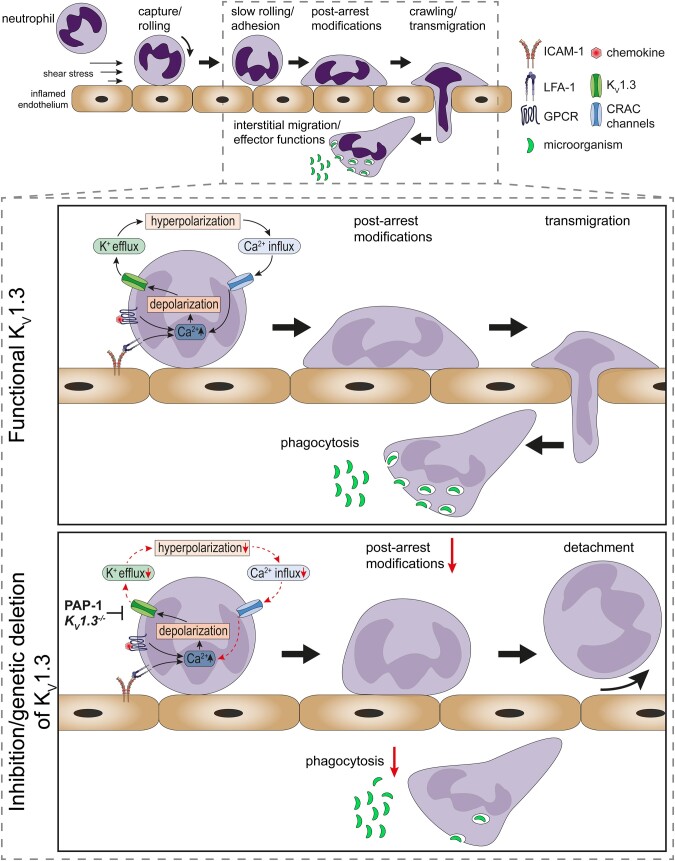

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Acute inflammatory processes involve the recruitment of innate immune cells from the intravascular compartment into affected tissues. Neutrophils constitute the ‘first line of defense’ and their recruitment follows a sequence of well-defined steps, starting with neutrophil tethering and rolling along the inflamed endothelium.1 Interactions with the inflamed endothelium activates neutrophils, leading to deceleration up to complete arrest.2 Following firm arrest, post-arrest modifications strengthen neutrophil attachment to the inflamed endothelium and guide the process of spreading, crawling, and subsequent transmigration through the endothelial lining.1 Once neutrophils arrive at the site of inflammation, they combat invading pathogens and non-self-agents by generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), release of granule contents, phagocytosis, and NETosis to immobilize and destroy microbes.2 Besides their beneficial role in the defense against invading pathogens, neutrophils also contribute to acute and chronic inflammatory disorders as well as autoimmune diseases.3

Almost all key events during neutrophil recruitment and activation depend on changes in intracellular calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]i).4 This includes transition of neutrophil slow rolling to firm adhesion,5 cytoskeletal rearrangement,6 migration,7 phagocytosis, ROS production, and degranulation.8 Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) is the predominant mechanism by which immune cells regulate changes in [Ca2+]i.9,10 Activation of G-protein coupled receptors and Fc receptors, and the engagement of β2-integrins, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1), and L-selectin (in humans) with their respective endothelial expressed ligands induce downstream signalling cascades that result in the release of Ca2+ stored in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).4 Ensuing influx of extracellular Ca2+ via Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels located in the plasma membrane further increases [Ca2+]i.10 Besides the predominant CRAC channel Orai1, leukocytes express a variety of other ion channels and receptors that contribute to changes in [Ca2+]i, among them transient receptor potential (TRP) channels and P2X receptors.11,12 Also flux of other ions through respective ion channels contribute to Ca2+ signalling in leukocytes, e.g. efflux of potassium.11 Voltage-dependent K+ currents over the plasma membrane have been described in human neutrophils,13 but could not be attributed to distinct ion channels so far.

The best-studied voltage-gated potassium channel in leukocytes is KV1.3 (KCNA3), a member of the Shaker related subfamily forming tetrameric transmembrane, K+ sensitive pores. In lymphocytes for example, KV1.3 regulates gene transcription and cell proliferation.14 In recent years, KV1.3 has attracted substantial scientific interest, since it is specifically up-regulated in activated effector memory T (TEM) cells,15 where it is thought to be a promising target to treat T cell driven autoimmune diseases.16,17 Recently, KV1.3 has also been reported to play a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.18 In contrast, expression and function of KV1.3 have not been directly addressed in neutrophils. Therefore, we set out to investigate expression and potential function of KV1.3 in mouse and human neutrophils. Using an electrophysiological whole-cell patch-clamp approach and various in vivo and in vitro functional assays, we detect KV1.3 expression in neutrophils and uncover KV1.3 as a key component for sustained SOCE in neutrophils. Using KV1.3 deficient mice, we found that loss of KV1.3 translates into impairment of various neutrophil effector functions including reduced neutrophil adhesion and extravasation, as well as reduced phagocytosis.

2. Methods

2.1 Animals and study approval

Kcna3tm1Lys (KV1.3−/−) mice19 were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and backcrossed into C57BL/6 WT mice. WT mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany). All mice were housed at the Biomedical Center, LMU, Planegg-Martinsried, Germany. Male and female mice (8–25 weeks old) were used for all experiments. Animal experiments were approved by the Government of Oberbayern (AZ.: ROB-55.2-2532.Vet_02-12-122, _02-15-229 and _02-18-22) and carried out in accordance with the guidelines from Directive 2010/63/EU. For in vivo experiments, mice were anaesthetized via i.p. injections using a combination of ketamine/xylazine (125 mg kg−1 and 12.5 mg kg−1 body weight, respectively in a volume of 0.1 mL 8 g−1 body weight). Adequacy of anaesthesia was ensured by testing the metatarsal reflex, monitored throughout the experiment and refreshed every hour (0.03 mL 8 g−1 body weight). All mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation.

2.2 Human blood sampling

Blood sampling from healthy volunteers was approved by the ethic committee from the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Munich, Germany (Az. 611-15) and by the institutional review board protocol at the University of California, Davis, USA (#235586-9) in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki. All volunteers signed a statement on written consent prior to blood sampling.

2.3 Kv1.3 expression

Murine bone marrow-derived neutrophils were isolated with a neutrophil enrichment kit (STEMCELL Technologies), whereas human neutrophils were extracted from whole blood of healthy volunteer blood donors using Polymorphprep (AXIS-SHIELD PoC AS). For confocal microscopy, isolated murine and human neutrophils were seeded on poly-L-lysine (0.1%; Sigma-Aldrich) coated object slides (Ibidi), fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and blocked with 2% BSA (Capricorn Scientific) for 1 h. Cells were stained overnight (ON) at 4°C using α-KV1.3 antibody (5 µg mL−1, rabbit-α-KV1.3; Alomone labs) recognizing an extracellular domain of the potassium channel. Donkey-α-rabbit-AlexaFluor®488 secondary antibody (5 µg mL−1, Invitrogen) was then added for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Finally, cells were stained with DAPI (Invitrogen) for 5 min at RT before embedding them in ProLong Diamond Antifade mounting medium (Invitrogen). Samples were imaged by confocal microscopy at the core facility Bioimaging of the Biomedical Center with a Leica SP8X WLL microscope, equipped with a HC PL APO 40x/1.30 NA oil immersion objective. Images were processed (including removal of outliers and background subtraction in the 488 channel) using FIJI software.20

Surface expression of KV1.3 was additionally assessed by flow cytometry. Therefore, isolated human neutrophils were stained with a FITC conjugated rabbit-α-KV1.3 antibody (5 µg mL−1, Alomone labs), or respective isotype control (5 µg mL−1, eBioscience), fixed (BD lysing solution), and resuspended in 1% BSA/PBS. Cells were analysed using a CytoFlex S flow cytometer (Beckmann Coulter) and FlowJo software. Neutrophils were defined as CD66b+/CD15+ population (clone G10F5 or HI98, respectively, both mouse-α human, 5 µg µL−1, BioLegend).

2.4 Patch-clamp of isolated human neutrophils

Human neutrophils were isolated from whole blood of five different healthy volunteer donors using EasySep neutrophil enrichment kit (STEMCELL Technologies) and resuspended in HBSS buffer [containing 0.1% of glucose, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.25% BSA, and 10 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich), pH7.4]. Purity of isolated cells was determined by flow cytometry (CD66b+/CD15+ population; clone G10F5 or HI98, respectively, both mouse-α human, clone HI98, 5 µg µL−1, BioLegend). Cells with a purity over 98±0.5% (mean±SEM) were used for experiments. Cells were seeded on poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips and subjected to patch-clamp experiments in whole-cell configuration as follows: cells were clamped at a holding potential of −80 mV intermitted by repeated 200 ms voltage steps from −80 to +40 mV using a 10 mV interval applied every 30 s. Current maxima at +40 mV were used for the calculation of Kv1.3 current amplitudes. Currents were normalized to cell size as current densities in pA/pF. Capacitance was measured using the automated capacitance cancellation function of the EPC-10 (HEKA, Harvard Bioscience). Patch pipettes were made of borosilicate glass (Science Products) and had resistance of 2–3.5 MΩ. Kv1.3 currents were inhibited with 10 nM 5-(4-Phenoxybutoxy)psoralen (PAP-1). Standard extracellular solution contained: 140 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 11 mM glucose (pH 7.2, 300mOsm). Intracellular solution contained: 134 mM KF, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 mM EGTA (pH 7.2, 300mOsm). Solutions were adjusted to 300mOsm using a Vapro 5520 osmometer (Wescor Inc.). PAP-1 (10 nM) was either added to the bath solution at least 15 min prior to electrophysiological recordings, or directly applied via an application pipette using constant pressure (Lorenz Messgerätebau).

2.5 Calcium signalling in human and murine neutrophils

Human neutrophils were isolated from whole blood of healthy volunteers using EasySep neutrophil enrichment kit. Isolated cells were suspended in HBSS with 0.1% HSA at 106 cells mL−1 and treated with macrophage-1 antigen (Mac-1) blocking antibody (clone M1/70; BioLegend) prior to perfusion. PAP-1 (10 nM) or vehicle pre-treated cells were then incubated with 1 µM Rhod-2 AM (ex/em: 552/581; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with or without Thapsigargin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min at RT in the dark. For static adhesion assays neutrophils were placed into a 48-well plate and allowed to settle for 60 s prior to addition of 1.5 mM calcium containing media for 3 min. Additionally, cells were stimulated by addition of 10 nM CXCL8 (Shenandoah) for 2 min. For investigation of cellular Ca2+ signalling under flow conditions microfluidic devices were designed to have four independent flow channels to analyse multiple conditions per coverslip (dimensions: 60 µm × 2 mm × 8 mm). Circular glass coverslips (35 mm diameter) were treated with Piranha solution (one part concentrated sulphuric acid and one part 30% hydrogen peroxide) for 20 min followed by treatment with acetone for 2 min. Coverslips were then dipped in 2% 3-aminiopropyltriethoxysilane (Fisher Scientific) in acetone for 5 min. Once dry, Protein A/G (Fischer Scientific) was covalently attached to the aminosilinated surface using a bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) substrate crosslinker (Pierce Thermo Scientific) ON. Afterwards, coverslips were coated with recombinant human (rh)ICAM-1 (Fc chimera; 5 µg mL−1; R&D Systems), CBR LFA1/2 LFA-1 antibody (20 µg mL−1; BioLegend) for 1 h, washed with PBS and blocked with 1% Casein (Pierce Thermo Scientific) for 15 min. Neutrophils pre-treated with Rhod-2 AM and Thapsigargin were perfused into the device at 0.1 dyne cm−2 and allowed to rest for 60 s prior to shear ramping up to 2 dyne cm−2 in 1.5 mM calcium containing media via a syringe pump (Cellix Ltd). Images were taken (1 fps) once neutrophils had settled in the 48 well plate or microfluidic device using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-S microscope (20× phase contrast air objective; 0.45 NA) equipped with a 16-bit digital CMOS camera (Andor ZYLA) with NIS Elements imaging software. All images were analysed using FIJI Software.

Changes in [Ca2+]i in bone marrow-derived WT and KV1.3−/− neutrophils were analysed using a single-cell imaging system of TillPhotonics and Fura-2-based ratiometric spectrometry. Cells were seeded on poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips and loaded with Fura-2 AM (5 µM) for 35 min at 37°C in HBSS. Cells were washed to remove unbound dye and transferred into Na+-Ringer solution (140 mM NaCl, 1–5 mM CaCl2, 2.8 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES NaOH, 11 mM glucose, pH 7.4). Neutrophils were identified visually by light microscopy (phase contrast) and region of interest were set using TILLvision software 4.0. After establishing a baseline, cells were stimulated with Thapsigargin (2 µM). Fura-2 ratios (F340nm/F380nm) were calculated as quotient of detected fluorescence intensities at 510 nm in response to 340/380 nm excitation.

2.6 Neutrophil spreading and detachment

To study neutrophil spreading, rectangular borosilicate glass capillaries (0.2×2.0 mm; CM Scientific) were coated with rhE-selectin (CD62E Fc chimera; 5 µg mL−1; R&D Systems), rhICAM-1 (4 µg mL−1; R&D Systems), and rhCXCL-8 (10 µg mL−1; Peprotech) for 3 h at RT and blocked with 5% casein ON at 4°C. Isolated human neutrophils (Polymorphprep) were incubated with PAP-1 (10 nM) or vehicle and applied into the flow chamber with a shear stress level of 1 dyne cm−2 using a high-precision syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus). To avoid interaction of the cells with the Fc part of the recombinant proteins, cells were incubated with hFc-block (human TruStain FcX; BioLegend) for 5 min at RT before being introduced into the chambers. Spreading behaviour of the cells was observed and recorded with a Zeiss Axioskop2 (equipped with a 20× water objective, 0.5 NA and a Hitachi KP-M1AP camera) and VirtualDub. Cell shape changes were quantified using FIJI software, analysing cell perimeters, circularity () and solidity ().

To investigate the resistance of neutrophils against increasing shear forces, µ-slides VI0.1 (Ibidi) were coated with rhE-selectin, rhICAM-1, and rhCXCL8, as described above. Isolated human neutrophils were resuspended in HBSS, blocked with hFc-block for 5 min at RT and incubated with PAP-1 (10 nM) or vehicle. A total of 106 cells mL−1 were introduced into the chamber and allowed to settle for 3 min before flow was started. First, 1 dyne cm−2 was applied for 1 min to remove non-attached cells and debris using HBSS and a high-precision syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus). The number of adherent cells FOV−1 was counted and set to 100%. Flow rates were then increased every 30 s and the fraction of remaining cells was counted at the end of each time interval. Experiments were conducted on a ZEISS, AXIOVERT 200 microscope, equipped with a ZEISS 10x objective [NA: 0.25] and a SPOT RT ST Camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc.). MetaMorph software was used to generate time laps movies for later analysis.

2.7 β2 Integrin activation

β2 Integrin activation assay was performed as previously described.21 Briefly, PAP-1 (10 nM) or vehicle pre-incubated isolated human neutrophils were stimulated with CXCL8 (10 nM) in the presence of either mouse-α-human KIM127 (InVivo, 10 µg µL−1) or mouse α-human mAB24 (Hycult Biotech, 10 µg µL−1) antibody for 5 min at 37°C in HBSS. Stimulation was stopped by adding ice-cold FACS lysing solution (BD BioScience). Cells were analysed by flow cytometry (CytoFlex S) and FlowJo software. Neutrophils were defined as CD15+/CD66b+ population. To assess overall surface expression of β2 integrins, cells were additionally stained with mouse α-human CD11a (clone HI111, 5 µg µL−1, BioLegend) and mouse α-human CD11b antibody (clone ICRF44, 5 µg µL−1, BioLegend).

2.8 Phagocytosis

Heparinized human whole blood pre-treated with PAP-1 (10 nM) or vehicle and murine whole blood from WT and KV1.3−/− mice was incubated with Escherichia coli bio particles (pHrodo Green E. coli BioParticle Phagocytosis Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at 37°C. Phagocytosis was stopped and cells were fixed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. As control, whole blood was incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Samples were analysed using a Beckman Coulter Gallios flow cytometer and Kaluza Flow analysis Software (Beckman Coulter). Ly6G+ and CD15+/CD66b+ positive populations were defined as neutrophils, respectively.

For confocal microscopy, phagocytosis was stopped by putting E. coli particles-treated whole blood on ice. Neutrophils were isolated (on ice) using EasySep neutrophil enrichment kit. Cells were then seeded on poly-L-lysine (0.1%; Sigma-Aldrich) coated object slides (Ibidi), fixed with 2% PFA washed and stained with DAPI (Invitrogen) for 5 min at RT before embedding them in ProLong Diamond Antifade mounting medium (Invitrogen). Samples were imaged by confocal microscopy at the core facility Bioimaging of the Biomedical Center with a Leica SP8X WLL microscope, equipped with a HC PL APO 40×/1.30 NA oil immersion objective. Images were processed (including removal of outliers and background subtraction) using FIJI software.

2.9 Neutrophil crawling in vitro

µ-Slides VI0.1 (Ibidi) were coated with a combination of rmE-selectin (CD62E Fc chimera; 20 µg mL−1; R&D Systems), rmICAM-1 (ICAM-1 Fc chimera; 15 µg mL−1; R&D Systems), and rmCXCL1 (15 µg mL−1; Peprotech) for 3 h at RT and blocked with 5% casein (Sigma-Aldrich) ON at 4°C. Bone marrow-derived neutrophils from KV1.3−/− and WT mice were isolated (EasySep neutrophil enrichment kit) and matured in RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 20% WEHI-3B-conditioned medium ON at 37°C. Cells were resuspended in HBSS, introduced into the chambers and allowed to settle and adhere for 3 min until flow was applied (2 dyne cm−2) using a high-precision syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus). Experiments were conducted on a ZEISS, AXIOVERT 200 microscope, provided with a ZEISS 10× objective [NA: 0.25], and a SPOT RT ST Camera. MetaMorph software was used to generate time laps movies for later analysis. 20 min of neutrophil crawling under flow were analysed using FIJI software [MTrackJ22 and Chemotaxis tool plugins (Ibidi)].

2.10 Paxillin phosphorylation

Paxillin phosphorylation was investigated as previously described.23 Briefly, bone marrow-derived murine neutrophils (2×106 cells) were seeded on rmICAM-1 (15 µg mL−1) coated wells for 10 min. Cells were stimulated with rmCXCL1 (10 nM) for 20 min at 37°C, lysed with lysis buffer [containing 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 (Applichem), 0.5% Sodium deoxycholate (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.3 (Merck), 2 mM EDTA (Merck) supplemented with protease (Roche), phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1xLaemmli sample buffer] and boiled (95°C, 5 min). Cell lysates were resolved by SDS–PAGE and electrophoretically transferred onto PVDF membranes. After subsequent blocking (LI-COR blocking solution), membranes were incubated with the following antibodies for later detection and analysis using the Odyssey® CLx Imaging System and Image Studio software: rabbit α-mouse p-Paxillin (Tyr118) rabbit α-mouse Paxillin (both CellSignaling), goat-α-mouse IRDye 680RD, and goat-α-rabbit IRDye800CW-coupled secondary antibodies.

2.11 Murine cremaster muscle experiments

Intravital microscopy of the mouse cremaster muscle was performed as previously described.24 Briefly, WT or KV1.3−/− mice received an intrascrotal (i.s.) injection of rmTNF-α (500 ng R&D Systems) to induce an acute inflammation in the cremaster muscle. 2 h after induction of inflammation, the carotid artery of anaesthetized mice was cannulated for later blood sampling (ProCyte Dx; IDEXX Laboratories) and the cremaster was muscle dissected. Intravital microscopy was conducted on an OlympusBX51 WI microscope, equipped with a 40× objective (Olympus, 0.8 NA, water immersion objective) and a CCD camera (Kappa CF 8 HS). Post-capillary venules were recorded using VirtualDub software for later analysis. Rolling flux fraction, number of adherent cells mm−2 was counted and vessel diameter and vessel length were determined off-line using FIJI software. During the entire observation period, the muscle was superfused with thermo-controlled bicarbonate buffer as described earlier.25 Centreline blood flow velocity in each venule was measured with a dual photodiode (Circusoft Instrumentation). One group of WT mice received an i.s. injection of PAP-1 (90 µg/mouse; Sigma-Aldrich), or vehicle (Ctrl) 1 h prior to TNF-α treatment. After microscopy, cremaster muscles were removed, fixed in 4% PFA solution, and stained with Giemsa (Merck) to calculate the number of perivascular neutrophils. Neutrophils were discriminated from other leukocyte subpopulations on the basis of the shape of cell nuclei and granularity of the cytosol. The analysis of transmigrated leukocytes was carried out at the core facility Bioimaging of the Biomedical Center with a Leica DM2500 microscope, equipped with a 100× objective (Leica, 1.4 NA, oil immersion) and a Leica DMC2900 CMOS camera.

2.12 Neutrophil adhesion in vitro

Flow chamber assays were carried out as previously described.24 Shortly, rectangular borosilicate glass capillaries (0.04×0.4 mm; VitroCom) were coated as mentioned above. Whole blood was collected from anaesthetized KV1.3−/− and WT mice via the heparinized carotid artery catheter and perfused through flow chambers at a shear stress level of 2.7 dyne cm−2 using a high-precision syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus). Movies were recorded with an OlympusBX51 WI microscope, equipped with a 20× objective (Olympus, 0.95 NA, water immersion objective) and a CCD camera (Kappa CF 8 HS) and VirtualDub software. Number of adherent leukocytes/field of view (FOV) was quantified after 6 min of blood perfusion. Whole blood of some KV1.3−/− and WT mice was additionally incubated with PAP-1 (10 nM) for 5 min at RT before flow chamber perfusion.

2.13 TNF-α induced peritonitis

Analysis of neutrophil extravasation into TNF-α stimulated peritoneum was carried out as previously described.26 WT or KV1.3−/− mice were stimulated with an i.p. injection of rmTNF-α (500 ng) for 6 h. Mice were sacrificed and a peritoneal lavage performed using 7 mL of ice-cold PBS. Cells were collected, stained, and analysed by flow cytometry (CytoFlex S) and FlowJo software. CD45+/CD11b+/GR-1+/CD115− cells were defined as neutrophils (all rat α-mouse 5 µg µL−1, BioLegend, clones: CD45: 30-F11, CD11b: M1/70, CD115: AFS98, Gr-1: RB6-8C5).

2.14 Statistics

Data are presented as mean±SEM, as cumulative distribution, or representative images/traces, as depicted in the figure legends. Group sizes were selected based on previous experiments. Data were analysed and illustrated using GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software). Statistical tests were performed according to the number of groups being compared. For pairwise comparison of experimental groups, an unpaired Student’s t-test and for more than two groups, a one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with either Tukey’s (one-way ANOVA) or Sidak’s (two-way ANOVA) post-hoc test were carried out, respectively. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant and indicated as follows: ∗P<0.05; ∗∗P<0.01; ∗∗∗P<0.001.

3. Results

3.1 Kv1.3 regulates sustained calcium entry in human neutrophils

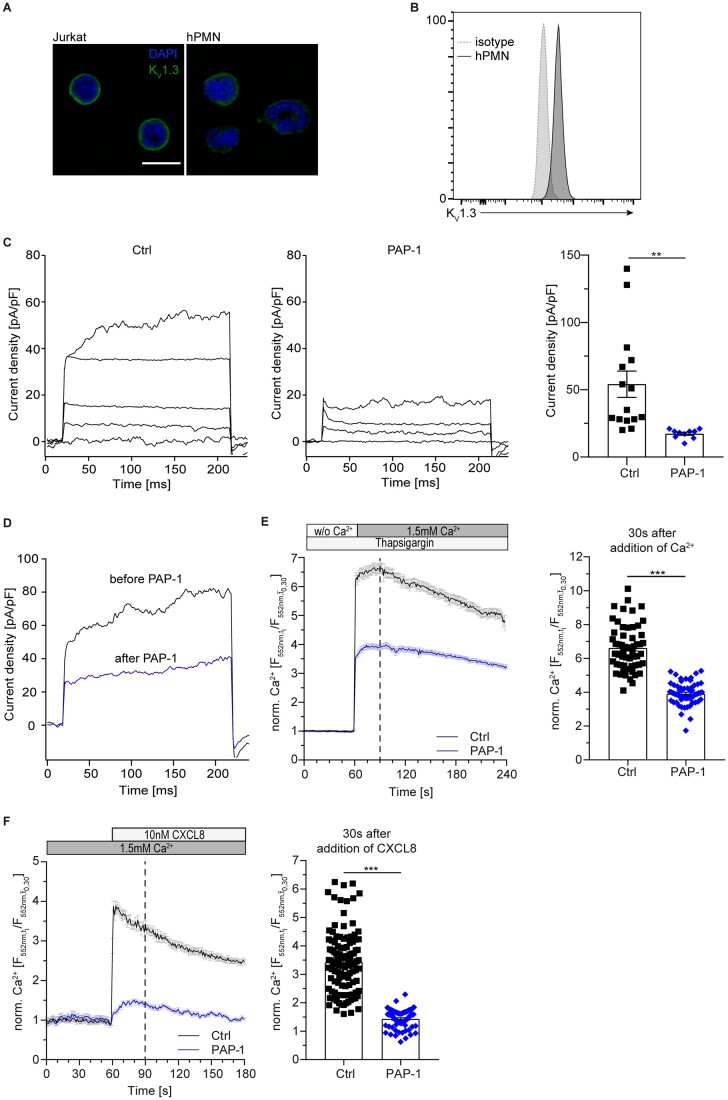

To test for expression of KV1.3 on neutrophils, confocal microscopy and flow cytometry were carried out with human neutrophils isolated from healthy donors. Both approaches revealed expression and localization of KV1.3 on the plasma membrane of neutrophils (Figure 1A and B). To assess functionality of KV1.3 on neutrophils, we performed electrophysiological experiments using a whole-cell patch-clamp approach. KV1.3 channels on isolated human neutrophils were activated with a 10 mV step protocol from −80 to +40 mV with 30 s intervals.27 Activated neutrophils developed typical voltage-activated potassium currents, which were significantly reduced by the addition of the KV1.3-specific inhibitor PAP-128 (Figure 1C). In turn, local application of PAP-1 after current activation with a single voltage-step up to +40 mV further confirmed that the observed K+ currents in neutrophils were sensitive to PAP-1-inhibition (Figure 1D), demonstrating the expression of functional KV1.3 channels in primary human neutrophils. Application of TRAM-34, a specific inhibitor of the calcium-gated potassium channel KCa3.1, which has previously been described in neutrophils29,30 did not significantly reduce currents over the plasma membrane, suggesting that KCa3.1 does not contribute to the observed currents in the applied step protocol (Supplementary material online, Figure S1).

Figure 1.

KV1.3 regulates sustained calcium entry in human neutrophils. Surface localization of KV1.3 was determined by (A) confocal microscopy (representative images from n=3 independent experiments, scale bar =10 m) and (B) flow cytometry (representative histogram of n=5 independent experiments). (C) Patch-clamp was used to investigate functionality of KV1.3 in primary human neutrophils in absence and presence of KV1.3 inhibitor PAP-1 (10 nM) and quantified. Application of 13 consecutive 10 mV steps from −80 to +40 mV induced the development of voltage-activated potassium currents in control cells (representative traces no. 1, 4, 8, 13 of n=10–15 cells for each treatment). (D) K+ currents measured in primary human neutrophils in absence (black) and after direct application of PAP-1 (blue; 10 nM) after current activation with a single voltage-step to +40 mV (representative traces of n=4 cells). Isolated human neutrophils were loaded with Rhod-2 AM and subsequently pre-treated with PAP-1 (10 nM) or vehicle (Ctrl). Changes in [Ca2+]i were observed in Ca2+ free buffer and after the addition of 1.5 mM Ca2+. (E) CRAC channel dependent Ca2+ influx relative to baseline [mean(t0,t30)] in human neutrophils pre-treated with Thapsigargin was determined under static conditions and [Ca2+]i was quantified 30 s after addition of Ca2+ to the medium [n=57 (Ctrl) and 60 (PAP-1) cells from 3 independent experiments, unpaired Student’s t-test]. (F) Total Ca2+ flux was investigated after stimulation with CXCL8 (10 nM) under static conditions and total [Ca2+]i relative to baseline [mean(t0,t30)] was quantified 30 s after stimulation with CXCL8 [n=118 (Ctrl) and 69 (PAP-1) cells from 3 independent experiments, unpaired Student’s t-test]. ***P≤0.001, data in (A)–(D) are given as representative plots/images/traces, data in (C), (E), and (F) are shown as mean±SEM. Dotted lines in (E) and (F) represent the time points of quantification.

In lymphocytes, KV1.3 regulates Ca2+ signalling by sustaining Ca2+ influx via SOCE.11 K+ efflux via KV1.3 affects the membrane potential, maintaining a high driving-force for continuous Ca2+ influx. To determine the contribution of KV1.3 on SOCE in neutrophils, we loaded isolated human neutrophils with the fluorometric Ca2+-indicator Rhod-2 AM under Ca2+-free conditions and pre-treated the cells with Thapsigargin to deplete Ca2+ stores in the ER. Subsequent addition of Ca2+ to the medium increased [Ca2+]i via SOCE in vehicle treated neutrophils (Ctrl), while presence of PAP-1 significantly reduced Ca2+ entry (Figure 1E). To study whether inhibition of KV1.3 alters the overall Ca2+ flux in neutrophils, we measured changes in [Ca2+]i upon chemokine activation without prior ER Ca2+ store depletion. To this end, neutrophils were loaded with Rhod-2 AM, seeded and exposed to Ca2+, which induced a slight increase in [Ca2+]i. Subsequent application of CXCL8 resulted in a characteristic Ca2+ spike (Figure 1F). In strong contrast, PAP-1 treated neutrophils failed to respond to Ca2+ and to CXCL8 stimulation. These findings reveal that KV1.3 substantially contributes to sustain SOCE in human neutrophils under static conditions.

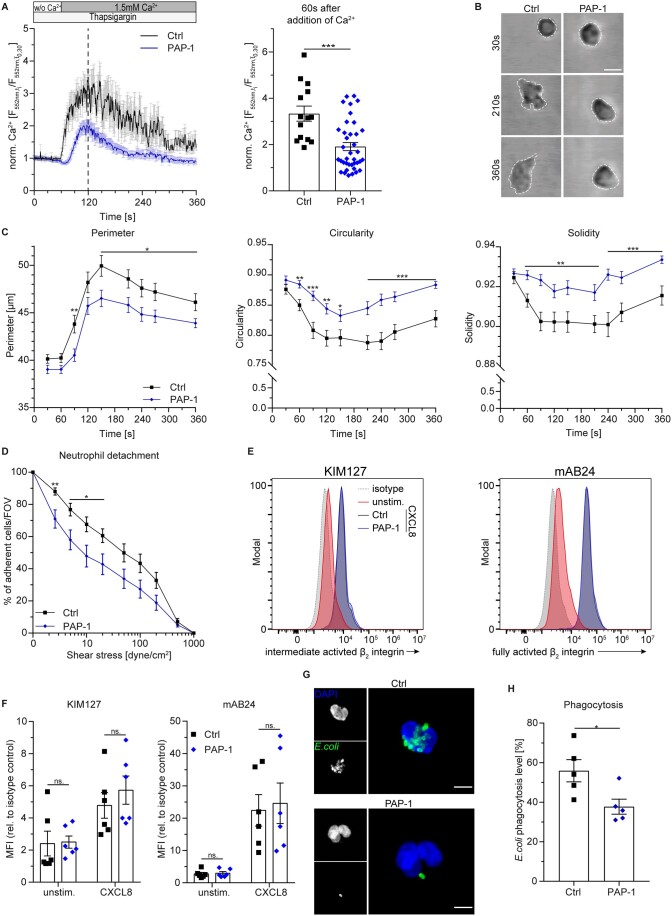

3.2 Kv1.3 regulates post-arrest modifications under flow and phagocytosis in human neutrophils

During firm adhesion, leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1)/intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) bonds induce post-arrest modifications that help to resist shear stress and facilitate neutrophil mobility (integrin outside-in signalling).5,31 During this process, CRAC channels co-cluster with LFA-1 and generate local Ca2+ influx enabling cellular shape changes.32 To examine the role of KV1.3 on LFA-1 mechano-signalling via SOCE, microfluidic devices were coated with high-affinity LFA-1-inducing antibody along with its endothelial ligand ICAM-133 and perfused with isolated, Rhod-2 AM-loaded human neutrophils. Adherent cells were exposed to shear flow and extracellular Ca2+, and subsequent changes in [Ca2+]i were measured (Figure 2A). Significant inhibition of Ca2+ influx was observed in the presence of PAP-1 compared to control, revealing a key role of KV1.3 in LFA-1 dependent regulation of SOCE during post-arrest modification steps. To further delineate how inhibition of KV1.3 and ensuing reduced [Ca2+]i might exert functional defects on neutrophil post-arrest modification steps, we performed spreading assays under flow. To this end, isolated human neutrophils were incubated with PAP-1 or vehicle control (Ctrl) and introduced into microflow chambers coated with E-selectin, ICAM-1, and CXCL8. This combination of recombinant proteins mimics the inflamed endothelium of post-capillary venules. After a short period of interaction with the substrate, flow was started and control neutrophils began to spread as indicated by flattening of the cells and the appearance of a migratory phenotype with membrane protrusions in the form of pseudopod formation (Figure 2B). Notably, the cellular shape of neutrophils incubated with PAP-1 remained smaller and rounder over time, displaying fewer protrusions as reflected by reduced perimeter and increased circularity and solidity, respectively (Figure 2C). To investigate whether reduced intracellular Ca2+ levels and impairment of spreading are accompanied by reduced leukocyte adhesion strengthening, we performed in vitro detachment assays by gradually increasing fluid shear forces. Isolated human neutrophils were again incubated with PAP-1 or vehicle and introduced into E-selectin, ICAM-1, and CXCL8-coated flow chambers. The cells were then allowed to settle and adhere for 3 min before flow rates were stepwise increased within the chamber. Neutrophils pre-incubated with PAP-1 were significantly more susceptible to detachment at physiological shear stress levels (2–20 dyne cm−2) compared to control cells (Figure 2D). To exclude that KV1.3 inhibition prevents β2 integrin activation (inside-out signalling), thereby affecting neutrophil adhesion, we analysed CXCL8 mediated β2 integrin activation in isolated human neutrophils using the activation-specific antibodies KIM127 (recognizing β2 integrin intermediate and high-affinity state) and mAB24 (recognizing the high-affinity state only).34 Flow cytometry revealed no differences in binding capacity of both antibodies between PAP-1 and vehicle pre-treated neutrophils (Figure 2E and F), demonstrating that KV1.3 is not involved in chemokine mediated β2 integrin activation. In addition, overall surface expression of the two β2 integrins LFA-1 and macrophage-1 antigen was not affected by KV1.3 blockade either (Supplementary material online, Figure S2).

Figure 2.

KV1.3 regulates post-arrest modifications under flow and phagocytosis in human neutrophils. (A) Ca2+ flux in human neutrophils pre-treated with Thapsigargin and perfused over a substrate of ICAM-1 and CBR LFA1/2 LFA-1 antibody using microfluidic devices was measured relative to baseline [mean(t0,t30)] and quantified 60 s after addition of Ca2+ under shear conditions [n=14 (Ctrl) and 38 (PAP-1) cells from 3 independent experiments, unpaired Student’s t-test]. (B) Human neutrophils were pre-treated with PAP-1 (10 nM) or vehicle (Ctrl), introduced into E-selectin, ICAM-1, and CXCL8-coated flow chambers and monitored over time (representative micrographs of neutrophils 30, 210, and 360 s after attachment; scale bar =10 µm). (C) Cell perimeter, cell circularity, and cell solidity were quantified over time [n = 49 (Ctrl) and 60 (PAP-1) cells from 5 independent experiments, repeated unpaired Student’s t-tests]. (D) Human neutrophils were exposed to stepwise increasing shear stress levels in E-selectin, ICAM-1, and CXCL8-coated flow chambers and percentage of remaining neutrophils FOV−1 was quantified after each step [n=13 (Ctrl) and 12 (PAP-1) flow chambers of 9–10 independent experiments, repeated unpaired Student’s t-tests]. (E) β2 Integrin intermediate and fully activation state (KIM127) and full activation state (mAB24) in PAP-1 (10 nM) and vehicle (Ctrl) treated human neutrophils were analysed by flow cytometry upon CXCL8 stimulation (representative flow cytometry plots) and (F) quantified (unstim.=unstimulated, MFI=median fluorescence intensity, n=6 independent experiments, two-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparison). (G) Phagocytic activity of neutrophils was measured using fluorescent E. coli particles in human whole blood pre-incubated with PAP-1 (10 nM) or vehicle (Ctrl) (representative micrographs, scale bar =5 µm) and (H) analysed by flow cytometry (n=5 independent experiments, paired Student’s t-test). ns, not significant; *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001, data in (A), (C), (D), (F), and (H) are given as mean±SEM and in (B), (E), and (G) as representative images/plots. Dotted lines in (A) represent time point of quantification.

Another function of neutrophils that is highly dependent on changes in [Ca2+]i is phagocytosis.4 Therefore, we speculated that KV1.3 might be involved in this process. Hence, pharmacological inhibition of KV1.3 may reduce the phagocytic activity of neutrophils. To test this, we incubated human whole blood from healthy donors with fluorescent E. coli particles and analysed phagocytosis using confocal microscopy and flow cytometry (Figure 2G and H and Supplementary material online, Figure S3). Inhibition of KV1.3 resulted in significantly reduced phagocytic activity compared to control, demonstrating that KV1.3 activity is required for efficient phagocytosis in neutrophils. Taken together, these findings reveal that KV1.3 regulates SOCE under flow and is therefore essential for post-arrest modification steps under physiological shear stress conditions as well as phagocytic activity of neutrophils.

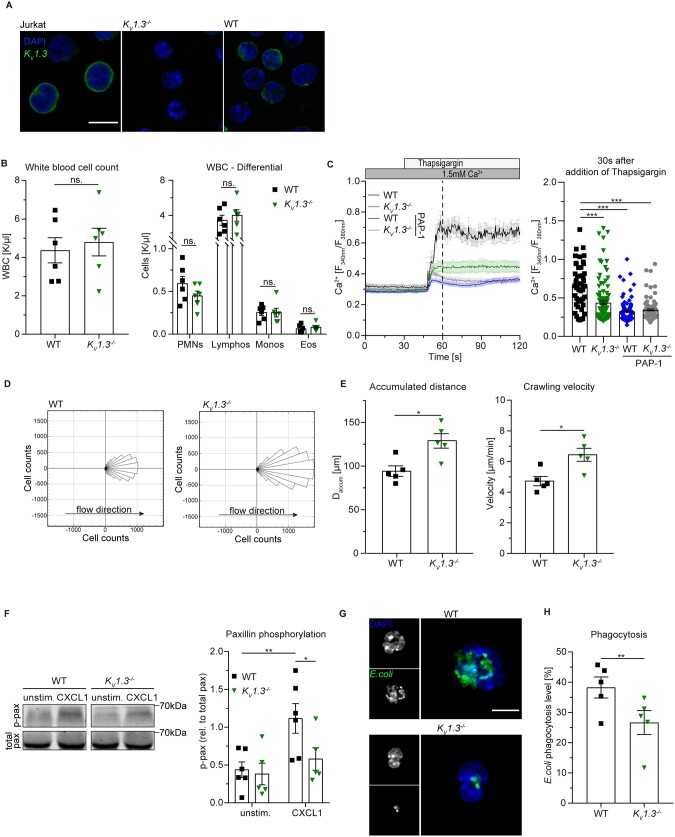

3.3 Genetic loss of KV1.3 impairs neutrophil crawling and phagocytosis in vitro

To elucidate the role of KV1.3 on post-arrest modification steps in more detail, we made use of KV1.3−/− mice,19 which lack the expression of KV1.3 on neutrophils (Figure 3A). Under homeostatic conditions, KV1.3−/− mice exhibited no differences in overall white blood cell (WBC) counts compared to wildtype (WT) mice (Figure 3B). Based on our observations that pharmacological inhibition of KV1.3 interferes with [Ca2+]i upon activation in human neutrophils, we first analysed SOCE in Fura-2 AM-loaded murine WT and KV1.3−/− neutrophils. WT cells showed a marked increase in [Ca2+]i 30 s after Ca2+ store depletion, whereas KV1.3−/− neutrophils exhibited significantly lower cytosolic Ca2+ levels (Figure 3C). Interestingly, PAP-1 treatment of both WT and KV1.3−/− cells reduced SOCE in a similar fashion and was more pronounced than in KV1.3−/− cells without PAP-1 treatment. This might indicate additional effects of PAP-1 in this setting.

Figure 3.

Genetic loss of KV1.3 reduces SOCE in neutrophils and impairs crawling and phagocytosis in vitro. (A) Surface localization of KV1.3 was determined by confocal microscopy (representative images from n=3 independent experiments, scale bar =10 µm). (B) Overall WBC counts (n=6 mice, unpaired Student’s t-test) and cell counts of leukocyte subsets (PMN: neutrophils, Lymphos: lymphocytes, Monos: monocytes, Eos: eosinophils; n=6 mice per group, two-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparison) are shown. (C) CRAC channel dependent Ca2+ influx in WT and KV1.3−/− neutrophils was determined under static conditions and [Ca2+]i was quantified 30 s after addition of Thapsigargin to the medium in absence and presence of PAP-1 [n=49 (WT), 107 (KV1.3−/−), 120 (WT + PAP-1), and 118 (KV1.3−/ + PAP-1) cells from 5 independent experiments, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparison]. (D) Neutrophil crawling of bone marrow-derived murine neutrophils was analysed in E-selectin, ICAM-1, and CXCL1-coated flow chambers under constant shear and (E) accumulated distance and crawling velocity were quantified [197 (WT) and 272 (KV1.3−/−) cells of n=5 mice per group, unpaired Student’s t-test]. (F) ICAM-1-induced paxillin phosphorylation of isolated WT and KV1.3−/− neutrophils upon CXCL1 stimulation was analysed by western blot (representative western blot of n=5–6 mice per group, two-way RM ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparison). (G) Phagocytic activity of neutrophils was measured using fluorescent E. coli particles in murine whole blood from WT and KV1.3−/− mice (representative micrographs, scale bar =5 µm) and (H) analysed by flow cytometry (n=5 independent experiments, paired Student’s t-test). *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001, data in (B), (C), (E), (F), and (H) are represented as mean±SEM, (D) as rose blots and in (A), (F), and (G) as representative blots or images, respectively.

In human neutrophils, KV1.3 regulates post-arrest modification steps under flow (see Figure 2A–D). Therefore, we hypothesized that crawling of mouse neutrophils is affected by the absence of KV1.3 as well. To test this, we introduced matured bone marrow-derived neutrophils from KV1.3−/− or WT mice into E-selectin, ICAM-1, and CXCL1-coated flow chambers and applied constant shear stress (2 dyne cm−2) after an initial 3 min time period in which the cells were allowed to adhere to the coated surface. In line with human data, where inhibition of KV1.3 resulted in reduced neutrophil spreading capability and increased susceptibility of the cells to increasing shear stress, KV1.3−/− cells were not able to firmly adhere to the coated flow chamber surface and exhibited a ‘jumping behavior’ instead of proper crawling on the substrate (Supplementary material online, Movie S1). Consequently, KV1.3−/− neutrophils covered a longer distance in flow direction after 20 min compared to WT cells (Figure 3D). In addition, accumulated crawling distance and crawling velocity (Figure 3E) were significantly increased in KV1.3−/− neutrophils compared to controls, emphasizing a crucial role of KV1.3 in mediating post-arrest modifications in neutrophils.

In order to investigate Kv1.3 dependent post-arrest modifications on a molecular level, we next investigated paxillin phosphorylation during outside-in signalling. Tyrosin phosphorylated paxillin links activated β2 integrins to the actin cytoskeleton.35 We analysed paxillin phosphorylation in isolated WT and KV1.3−/− neutrophils seeded on ICAM-1. In WT cells, CXCL1 stimulation significantly induced paxillin phosphorylation compared to unstimulated condition, while KV1.3−/− neutrophils failed to phosphorylate paxillin (Figure 3F). These results suggest that KV1.3 activity is important for β2 integrin outside-in signalling during neutrophil recruitment.

Next, we also studied phagocytic activity of murine peripheral blood neutrophils. Whole blood from KV1.3−/− or WT mice was incubated with fluorescent E. coli particles and analysed by confocal microscopy and flow cytometry (Supplementary material online, Figure S4). Similar to pharmacological inhibition in human neutrophils, genetic ablation of KV1.3 significantly reduced phagocytic activity of murine neutrophils compared to WT control (Figure 3G and H).

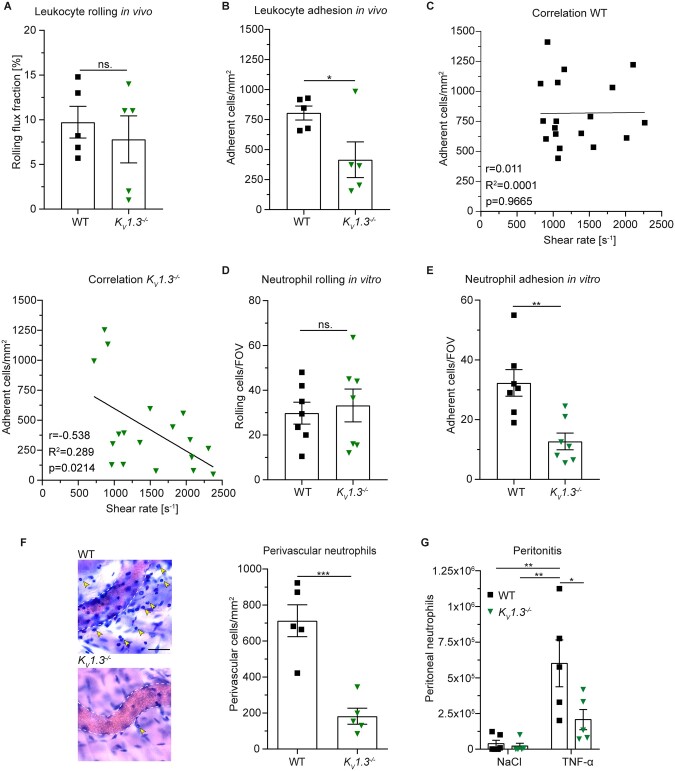

3.4 Genetic loss of KV1.3 impairs neutrophil recruitment in vivo

Next, we assessed whether loss of KV1.3 and resulting impaired neutrophil spreading and crawling affects leukocyte recruitment in mouse models of microvascular inflammation in vivo. First, we performed intravital microscopy of post-capillary venules in the mouse cremaster muscle 2 h after intrascrotal (i.s.) injection of TNF-α (Supplementary material online, Movie S2). This model is a well-established technique to study acute, predominantly neutrophil-driven inflammatory processes.36 Rolling flux fraction (percentage of rolling leukocytes as a function of total WBC flux37) was not altered in KV1.3−/− mice compared to WT control (Figure 4A). However, KV1.3−/− mice exhibited significantly reduced numbers of adherent cells to the inflamed endothelium compared to control (Figure 4B). In line, i.s. application of PAP-1 into WT mice 1 h prior to injection of TNF-α did not alter leukocyte rolling, but reduced leukocyte adhesion compared to vehicle application (Supplementary material online, Figure S5). Interestingly, PAP-1 did not further reduce leukocyte adhesion in KV1.3−/− mice, indicating specificity of PAP-1 in this in vivo model of microvascular inflammation. Of note, microvascular and hemodynamic parameters (vessel diameter, blood flow velocity, shear rate, WBC, and neutrophil count) were not different among the groups (Supplementary material online, Table S1). To see whether genetic loss of KV1.3 results in increased susceptibility to physiological shear forces in vivo similar to PAP-1 mediated inhibition in vitro (shown in Figure 2D), we correlated individual numbers of adherent leukocytes to the inflamed vessel surface with the respective shear rate levels of each venule measured during intravital microscopy. Whereas leukocyte adhesion did not correlate with shear rate levels in WT mice, KV1.3−/− mice exhibited a significant negative correlation (Figure 4C), underlining the important role of KV1.3 in mediating neutrophil adhesion strengthening in vivo. Importantly, overall surface expression of CD18, CD11a, CD11b, PSGL-1, CD44, L-selectin, and CXCR2 on peripheral blood neutrophils did not differ between KV1.3−/− and WT mice (Supplementary material online, Figure S6). In order to focus exclusively on neutrophils and to elucidate the function of KV1.3 during neutrophil recruitment in a reduced environment, we performed in vitro flow chamber assays using E-selectin, ICAM-1, and CXCL1-coated glass capillaries and murine whole blood. This combination of recombinant proteins captures almost exclusively neutrophils. Also in this experimental setting, genetic deletion of KV1.3 did not affect neutrophil rolling (Figure 4D) but significantly reduced numbers of adherent neutrophils per FOV compared to control (Figure 4E). In line, pharmacological inhibition using PAP-1 did not affect neutrophil rolling, but significantly reduced shear-resistant neutrophil adhesion to the coated glass capillaries (Supplementary material online, Figure S7A and B). In addition, PAP-1 did not further decrease neutrophil adhesion in KV1.3−/− mice thereby excluding any additional effects of the inhibitor on neutrophil adhesion. Importantly, WBCs of the mice did not differ among the groups (Supplementary material online, Figure S7C and D). These findings clearly show that KV1.3 is dispensable for neutrophil capture and rolling along inflamed endothelium, but plays a critical role in mediating β2 integrin-dependent firm adhesion, a process that is highly dependent on SOCE.38

Figure 4.

Genetic loss of KV1.3 impairs neutrophil recruitment in vivo. WT and KV1.3−/− mice were stimulated i.s. with TNF-α 2 h prior to intravital microscopy of post-capillary venules of the cremaster muscle and (A) neutrophil rolling and (B) number of adherent neutrophils per vessel surface were analysed [18 (WT) and 18 (KV1.3−/−) vessels of n=5 mice per group, unpaired Student’s t-test]. (C) Intravascular shear rates were correlated with respective numbers of adherent cells in WT and KV1.3−/− mice [n=18 (WT) and 18 (KV1.3−/−) vessels of 5 mice per group, Pearson correlation]. E-selectin, ICAM-1, and CXCL1-coated flow chambers were perfused with murine whole blood from KV1.3−/− and WT mice and number of (D) rolling and (E) adherent cells FOV−1 were analysed (20–22 flow chambers from n=7 mice per group, unpaired Student’s t-test). (F) TNF-α stimulated cremaster muscles were stained with Giemsa (representative micrographs, scale bar =30 µm, arrows: transmigrated neutrophils) and number of perivascular neutrophils was quantified [25 (WT) and 59 (KV1.3−/−) vessels of n=5 mice per group, unpaired Student’s t-test]. (G) Normal saline (NaCl) or TNF-α was injected i.p. into WT and KV1.3−/− mice and numbers of recruited neutrophils to the peritoneum were assessed 6 h later (n=5 mice per group, two-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparison). *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, data in (A), (B), and (D)–(G) are represented as mean±SEM, in (C) as Pearson correlation, and in (F) as representative images.

To test whether reduced leukocyte adhesion in KV1.3−/− mice results in reduced numbers of transmigrated neutrophils, we stained TNF-α stimulated cremaster muscles with Giemsa and quantified neutrophil extravasation into the inflamed tissue. Genetic deletion of KV1.3 resulted in significantly reduced numbers of perivascular neutrophils compared to WT (Figure 4F). In addition, we analysed the extravasation index (number of perivascular neutrophils in relation to intravascular adherent neutrophils) in TNF-α stimulated cremaster muscles of KV1.3−/− and WT mice. KV1.3−/− mice exhibited a significantly lower extravasation index compared to WT control (Supplementary material online, Figure S8A) suggesting a role for KV1.3 not only in intraluminal post-adhesion steps in vivo, but also in neutrophil transmigration into inflamed tissue.

Finally, we tested the effect of KV1.3 activity on neutrophil extravasation in an in vivo peritonitis model. KV1.3−/− and WT mice were intra peritoneally (i.p.) treated with TNF-α and number of recruited neutrophils into the peritoneum was assessed 6 h later by flow cytometry. Basal neutrophil levels (NaCl treatment) did not differ between KV1.3−/− and WT mice, whereas numbers of neutrophils in the peritoneal lavage following TNF-α stimulation were significantly decreased in KV1.3−/− compared to WT mice (Figure 4G and Supplementary material online, Figure S8B), confirming impaired neutrophil extravasation to the site of inflammation in the absence of KV1.3.

4. Discussion

In neutrophils, changes in [Ca2+]i need to be tightly regulated in a spatiotemporal manner to control the various downstream effector pathways during their recruitment from the intravascular compartment into affected tissues.4 Current knowledge of the complex network of ion channels, i.e. which channels are expressed and how they differentially convert Ca2+ oscillations into distinct intracellular signals is incompletely understood, but has made significant progress in recent years. In this study, we discover expression and functionality of the voltage-gated potassium channel KV1.3 in neutrophils and describe severe impairment of neutrophil functions during acute inflammation when KV1.3 is genetically absent or pharmacologically blocked (see Graphical Abstract).

The role of KV1.3 in regulating membrane potential and Ca2+ flux in immune cells has been intensively investigated in T cells, showing that an increase in [Ca2+]i and concomitant depolarization of the cell membrane opens this voltage-gated channel, allowing K+ to leave the cell.39 K+ efflux in turn hyperpolarizes the cellular membrane supporting sustained Ca2+ influx via CRAC channels. KV1.3 mediated long lasting high [Ca2+]i regulate T cell activation, proliferation, cytokine production, and motility within inflamed tissue.16,40 Using a whole-cell patch-clamp approach and calcium imaging, we show that depolarization of human neutrophils results in a characteristic KV1.3 outward current and, similar to T cells, pharmacological inhibition or genetic ablation of KV13 reduces SOCE and [Ca2+]i.

During neutrophil recruitment, fluid shear forces exerted by the flowing blood within the vasculature act on LFA-1/ICAM-1 bonds of adherent neutrophils and amplify CRAC channel dependent Ca2+ influx.32 This enables the cells to rearrange their cytoskeleton, leading to subsequent shape change, polarization, and migration. We now demonstrate that neutrophils require KV1.3 function to efficiently adhere to the endothelium and to rearrange their cytoskeleton under flow. Consequently, neutrophils lacking KV1.3 or neutrophils treated with a KV1.3 inhibitor are unable to spread and to crawl properly and to withstand physiological shear forces. The predominant CRAC channel in neutrophils that cooperates with LFA-1 to regulate Ca2+ entry during recruitment is Orai1.4 During activation, it is recruited to sites of focal adhesion and co-localizes with high-affinity LFA-1 to facilitate F-actin polymerization and neutrophil shape change.32 This is achieved by formation of a molecular complex consisting of LFA-1, Kindlin3, and Orai1, which induces through mechano-signals local increase of [Ca2+]i, thereby creating Ca2+-rich microdomains that enable fast and efficient reorganization of the cytoskeleton that guide neutrophil migration.41 We expand this picture by showing that K+ efflux through KV1.3 is critical for maintaining a high electro-chemical driving force during LFA-1-mediated Ca2+ influx via SOCE. Thus, it appears that KV1.3 is involved in the generation of locally high Ca2+ concentrations within adhesive sites as well. Support for this comes from observations showing a physical interaction of KV1.3 with integrins in T cells and melanoma cells.42,43

Interestingly, pharmacological inhibition of KV1.3 did not alter β2 integrin affinity states upon CXCL8 treatment, demonstrating that KV1.3 is not involved in chemokine-induced integrin inside-out signalling. However, KV1.3 and sustained Ca2+ influx are indispensable for efficient outside-in signalling as inhibition/lack of KV1.3 resulted in impaired paxillin phosphorylation and a higher susceptibility of adherent neutrophils to detach from inflamed venules with increasing shear forces exerted by blood flow. This highlights KV1.3 as an important player in linking adhesion receptors to the cytoskeleton.

The critical role of KV1.3 during neutrophil recruitment is also supported by our in vivo observations that both, genetic deletion of KV1.3 and application of PAP-1 reduced the number of adherent and extravasated cells in mouse models of acute microvascular inflammation. We interpret reduced extravasation in parts as a consequence of reduced adhesion and impaired post-arrest modifications. In addition, the calculated extravasation index suggests that KV1.3 might also be involved in neutrophil transmigration across the inflamed endothelium. This hypothesis is supported by reports revealing that interference with KV1.3 reduces cell migration in macrophages,44,45 T cells,40 or microglia cells,46 too.

Besides KV1.3, the calcium-gated potassium channel KCa3.1 is also expressed on neutrophils and was shown to have a role in the regulation of neutrophil migration,29 although an in-depth analysis on the role of KCa3.1 in neutrophil recruitment and a potential cooperative interplay of KCa3.1 with KV1.3 are still missing and warrant further investigation.

Of note, Grimes et al.30 recently described different populations of bone marrow-derived murine neutrophils with a distinct expression pattern of KCa3.1 and characteristic calcium signalling signatures which led them to conclude that regulation of membrane potential might be developmentally controlled. However, this has not been studied for KV1.3, but is of great interest as neutrophil function has been reported to be ontogenetically regulated acquiring full functionality only after birth.47,48

Finally, we report that KV1.3 is involved in effector functions of neutrophils within the tissue, as absence of channel activity reduces phagocytic activity in human and murine neutrophils. Similar results were described for KV1.3 and its role in phagocytosis in microglia cells.46 Many events during phagocytosis are dependent on Ca2+ signalling in neutrophils, such as fusion of primary and secondary granules to the early phagosome or formation of the actin meshwork surrounding phagosomes.8 Our results indicate that sustained Ca2+ influx mediated by K+ efflux via KV1.3 is a prerequisite for efficient phagocytosis. Furthermore, K+ efflux has also been reported to be important for maintaining phagosomal NADPH oxidase activity.49,50 Thus, neutrophil-expressed KV1.3 might also be involved in retaining sufficient ROS thereby ensuring bacterial killing.

In recent years, KV1.3 has become an interesting pharmacological target to treat T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS),51 rheumatoid arthritis52 type I diabetes mellitus,16 or psoriasis,53 as well as neurodegenerative disorders.54 The great therapeutic potential of KV1.3 blockers is based on the fact that KV1.3 specifically gets up-regulated in TEM cells but not in naïve or central memory T (TCM) cells.15 TEM cells play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of many autoimmune diseases.55 By showing that KV1.3 regulates important neutrophil functions during recruitment and within the tissue, we expand the application field of KV1.3 inhibitors to acute and chronic inflammatory disorders that go along with overwhelming immune responses, such as autoimmune arthritis, atherosclerosis, or COPD.56–58 This also includes autoimmune diseases as MS, psoriasis, or Alzheimer’s disease where neutrophils have been shown to contribute to the progression of the diseases.3

Albeit, its remarkable role in immune regulation of both, innate and adaptive immune cells, mice lacking KV1.3 do neither exhibit any obvious immuno-phenotype, nor alterations in WBC under homoeostatic conditions. This may in part be explained by compensatory Cl− currents as suggested earlier.19 Although we did not account for compensatory anion currents in knockout neutrophils, we demonstrate that CRAC channel dependent Ca2+ influx is impaired, ensuring that the observed effects in this study can be attributed to KV1.3 function and impaired sustained Ca2+ signalling.

Taken together, we identify the neutrophil-expressed voltage-gated potassium channel KV1.3 as a critical regulator of neutrophil function, and show that its absence or pharmacological inhibition leads to impaired intracellular Ca2+ signalling and reduced neutrophil recruitment into inflamed tissue. Interfering with KV1.3 activity in neutrophils may therefore offer a broad range of new therapeutic opportunities in patients with unwanted excessive neutrophil recruitment, which is observed frequently not only in acute and chronic inflammatory disorders, but also in autoimmune disorders and graft-vs.-host disease.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Authors’ contributions

R.I. designed and conducted experiments, analysed data, and wrote the manuscript. W.N., A.B., V.M., I.R., S.M.-A., T.S., and A.Y. acquired and analysed data. O.S., M.M., T.G., and E.R.B. provided their expertise. S.I.S., M.R., and S.Z. designed experiments and edited the manuscript, analysed results and provided their expertise. M.P. designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript and M.S. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dorothee Gössel, Anke Lübeck, and David Kutschke for excellent technical assistance, Stephan Grissmer for providing critical reagents and helpful discussions and the core facility Bioimaging at the Biomedical Center, LMU, Planegg-Martinsried, Germany.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) collaborative research grant SFB914, projects A01 (to M.M.), B01 (to M.S.), B11 (to M.P.) the DFG TRR-152, projects P14 (to S.Z.) and P15 (to T.G.), by the FöFoLe-Program of the Medical Faculty, LMU Munich (R.I. and M.S.), and the National Institute of Health of the USA (NIH), grant R01 AI047294 (to S.I.S.).

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its Supplementary material online. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Contributor Information

Roland Immler, Walter Brendel Centre of Experimental Medicine, Biomedical Center, Institute of Cardiovascular Physiology and Pathophysiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Großhaderner Straße 9, 82152 Planegg-Martinsried, Germany.

Wiebke Nadolni, Walther-Straub Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Goethestraße 33, 80336 Munich, Germany.

Annika Bertsch, Walter Brendel Centre of Experimental Medicine, Biomedical Center, Institute of Cardiovascular Physiology and Pathophysiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Großhaderner Straße 9, 82152 Planegg-Martinsried, Germany.

Vasilios Morikis, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Graduate Group in Immunology, University of California, 451 E. Health Sciences Drive, Davis, CA 95616, USA.

Ina Rohwedder, Walter Brendel Centre of Experimental Medicine, Biomedical Center, Institute of Cardiovascular Physiology and Pathophysiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Großhaderner Straße 9, 82152 Planegg-Martinsried, Germany.

Sergi Masgrau-Alsina, Walter Brendel Centre of Experimental Medicine, Biomedical Center, Institute of Cardiovascular Physiology and Pathophysiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Großhaderner Straße 9, 82152 Planegg-Martinsried, Germany.

Tobias Schroll, Walter Brendel Centre of Experimental Medicine, Biomedical Center, Institute of Cardiovascular Physiology and Pathophysiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Großhaderner Straße 9, 82152 Planegg-Martinsried, Germany.

Anna Yevtushenko, Walter Brendel Centre of Experimental Medicine, Biomedical Center, Institute of Cardiovascular Physiology and Pathophysiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Großhaderner Straße 9, 82152 Planegg-Martinsried, Germany.

Oliver Soehnlein, Institute for Cardiovascular Prevention (IPEK), Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Pettenkofer Straße 8a, 80336 Munich, Germany; Department of Physiology and Pharmacology (FyFa), Karolinska Institutet, Solnavägen 1, 17177 Stockholm, Sweden; Institute for Experimental Pathology (ExPat), Center for Molecular Biology of Inflammation (ZMBE), Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Von-Enmarch-Straße 56, 48149 Münster, Germany.

Markus Moser, Institute of Experimental Hematology, School of Medicine, Technical University Munich, Einsteinstraße 25, 81675 Munich, Germany.

Thomas Gudermann, Walther-Straub Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Goethestraße 33, 80336 Munich, Germany.

Eytan R Barnea, BioIncept LLC, New York, 140 East 40th Street #11E, NY 10016, USA.

Markus Rehberg, Institute of Lung Biology and Disease, Helmholtz Zentrum München, Ingolstädter Landstraße 1, 85764 Neuherberg, Germany.

Scott I Simon, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Graduate Group in Immunology, University of California, 451 E. Health Sciences Drive, Davis, CA 95616, USA.

Susanna Zierler, Walther-Straub Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Goethestraße 33, 80336 Munich, Germany.

Monika Pruenster, Walter Brendel Centre of Experimental Medicine, Biomedical Center, Institute of Cardiovascular Physiology and Pathophysiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Großhaderner Straße 9, 82152 Planegg-Martinsried, Germany.

Markus Sperandio, Walter Brendel Centre of Experimental Medicine, Biomedical Center, Institute of Cardiovascular Physiology and Pathophysiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Großhaderner Straße 9, 82152 Planegg-Martinsried, Germany.

Translational perspective

Neutrophils exert important immune functions during tissue injury or bacterial infection through leaving the vasculature and extravasate into affected tissues. Conversely, neutrophils trigger the pathogenesis of acute and chronic inflammatory disorders and are involved in the development and maintenance of various autoimmune diseases. Within this study, we show that the voltage-gated potassium channel KV1.3 is functionally expressed on neutrophils and affects calcium signalling thereby regulating neutrophil effector functions during immune responses. Hence, KV1.3 represents an interesting potential new target to treat unwanted excessive neutrophil invasion in various disorders ranging from autoinflammatory disorders to ischemic tissue injury.

References

- 1. Schmidt S, Moser M, Sperandio M. The molecular basis of leukocyte recruitment and its deficiencies. Mol Immunol 2013;55:49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ley K, Hoffman HM, Kubes P, Cassatella MA, Zychlinsky A, Hedrick CC, Catz SD. Neutrophils: new insights and open questions. Sci Immunol 2018;3:eaat4579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Németh T, Sperandio M, Mócsai A. Neutrophils as emerging therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020;19:253–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Immler R, Simon SI, Sperandio M. Calcium signalling and related ion channels in neutrophil recruitment and function. Eur J Clin Invest 2018;48:e12964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schaff UY, Yamayoshi I, Tse T, Griffin D, Kibathi L, Simon SI. Calcium flux in neutrophils synchronizes β2 integrin adhesive and signaling events that guide inflammatory recruitment. Ann Biomed Eng 2008;36:632–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kruskal BA, Shak S, Maxfield FR. Spreading of human neutrophils is immediately preceded by a large increase in cytoplasmic free calcium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1986;83:2919–2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schwab A, Fabian A, Hanley PJ, Stock C. Role of ion channels and transporters in cell migration. Physiol Rev 2012;92:1865–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nunes P, Demaurex N. The role of calcium signaling in phagocytosis. J Leukoc Biol 2010;88:57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clemens RA, Lowell CA. Store-operated calcium signaling in neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol 2015;98:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clemens RA, Lowell CA. CRAC channel regulation of innate immune cells in health and disease. Cell Calcium 2019;78:56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feske S, Wulff H, Skolnik EY. Ion channels in innate and adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2015;33:291–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zierler S, Hampe S, Nadolni W. TRPM channels as potential therapeutic targets against pro-inflammatory diseases. Cell Calcium 2017;67:105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krause KH, Welsh MJ. Voltage-dependent and Ca2+-activated ion channels in human neutrophils. J Clin Invest 1990;85:491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perez GM, Cidad P, Lopez-Lopez JR. The secret life of ion channels: kv1.3 potassium channels and cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2018;314:C27–C42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wulff H, Calabresi PA, Allie R, Yun S, Pennington M, Beeton C, Chandy KG. The voltage-gated Kv1.3 K+ channel in effector memory T cells as new target for MS. J Clin Invest 2003;111:1703–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beeton C, Wulff H, Standifer NE, Azam P, Mullen KM, Pennington MW, Kolski-Andreaco A, Wei E, Grino A, Counts DR, Wang PH, LeeHealey CJ, S Andrews B, Sankaranarayanan A, Homerick D, Roeck WW, Tehranzadeh J, Stanhope KL, Zimin P, Havel PJ, Griffey S, Knaus H-G, Nepom GT, Gutman GA, Calabresi PA, Chandy KG. Kv1.3 channels are a therapeutic target for T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:17414–17419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chandy KG, Norton RS. Peptide blockers of Kv1.3 channels in T cells as therapeutics for autoimmune disease. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2017;38:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen YC, Rivera J, Fitzgerald M, Hausding C, Ying Y-L, Wang X, Todorova K, Hayrabedyan S, Barnea ER, Peter K. PreImplantation factor prevents atherosclerosis via its immunomodulatory effects without affecting serum lipids. Thromb Haemost 2016;115:1010–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koni PA, Khanna R, Chang MC, Tang MD, Kaczmarek LK, Schlichter LC, Flavell RA. Compensatory anion currents in Kv1.3 channel-deficient thymocytes. J Biol Chem 2003;278:39443–39451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaying V, Longhair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez J, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 2012;9:676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Immler R, Lange-Sperandio B, Steffen T, Beck H, Roth J, Hupel G, Pfister F, Popper B, Uhl B, Mannell H, Reichel C, Vielhauer V, Scherberich J, Sperandio M, Pruenster M. Extratubular polymerized uromodulin induces leukocyte recruitment and inflammation in vivo. Front Immunol 2020;11:588245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meijering E, Dzyubachyk O, Smal I. Methods for cell and particle tracking. Methods Enzymol 2012;504:183–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rohwedder I, Kurz ARM, Pruenster M, Immler R, Pick R, Eggersmann T, Klapproth S, Johnson JL, Alsina SM, Lowell CA, Mócsai A, Catz SD, Sperandio M. Src family kinase-mediated vesicle trafficking is critical for neutrophil basement membrane penetration. Haematologica 2020;105:1845–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pruenster M, Kurz ARM, Chung K-J, Cao-Ehlker X, Bieber S, Nussbaum CF, Bierschenk S, Eggersmann TK, Rohwedder I, Heinig K, Immler R, Moser M, Koedel U, Gran S, McEver RP, Vestweber D, Verschoor A, Leanderson T, Chavakis T, Roth J, Vogl T, Sperandio M. Extracellular MRP8/14 is a regulator of β2 integrin-dependent neutrophil slow rolling and adhesion. Nat Commun 2015;6:6915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ley K, Gaehtgens P. Endothelial, not hemodynamic, differences are responsible for preferential leukocyte rolling in rat mesenteric venules. Circ Res 1991;69:1034–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kurz ARM, Pruenster M, Rohwedder I, Ramadass M, Schäfer K, Harrison U, Gouveia G, Nussbaum C, Immler R, Wiessner JR, Margraf A, Lim D, Walzog B, Dietzel S, Moser M, Klein C, Vestweber D, Haas R, Catz SD, Sperandio M. MST1-dependent vesicle trafficking regulates neutrophil transmigration through the vascular basement membrane. J Clin Invest 2016;126:4125–4139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grossinger EM, Weiss L, Zierler S, Rebhandl S, Krenn PW, Hinterseer E, Schmolzer J, Asslaber D, Hainzl S, Neureiter D, Egle A, Pinon-Hofbauer J, Hartmann TN, Greil R, Kerschbaum HH. Targeting proliferation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells through KCa3.1 blockade. Leukemia 2014;28:954–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmitz A, Sankaranarayanan A, Azam P, Schmidt-Lassen K, Homerick D, Haensel W, Wulff H. Design of PAP-1, a selective small molecule Kv1. 3 blocker, for the suppression of effector memory T cells in autoimmune diseases. Mol Pharmacol 2005;68:1254–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Henríquez C, Riquelme TT, Vera D, Julio-Kalajzić F, Ehrenfeld P, Melvin JE, Figueroa CD, Sarmiento J, Flores CA. The calcium-activated potassium channel KCa3.1 plays a central role in the chemotactic response of mammalian neutrophils. Acta Physiol 2016;216:132–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grimes D, Johnson R, Pashos M, Cummings C, Kang C, Sampedro GR, Tycksen E, McBride HJ, Sah R, Lowell CA, Clemens RA. ORAI1 and ORAI2 modulate murine neutrophil calcium signaling, cellular activation, and host defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020;117:24403–24414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morikis VA, Masadeh E, Simon SI. Tensile force transmitted through LFA-1 bonds mechanoregulate neutrophil inflammatory response. J Leukoc Biol 2020;108:1815–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Morikis VA, Simon SI. Neutrophil Mechanosignaling Promotes Integrin Engagement With Endothelial Cells and Motility Within Inflamed Vessels. Front Immunol 2018;9:2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morikis VA, Chase S, Wun T, Chaikof EL, Magnani JL, Simon SI. Selectin catch-bonds mechanotransduce integrin activation and neutrophil arrest on inflamed endothelium under shear flow. Blood 2017;130:2101–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Evans R, Patzak I, Svensson L, Filippo KD, Jones K, McDowall A, Hogg N. Integrins in immunity. J Cell Sci 2009;122:215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cohen-Hillel E, Mintz R, Meshel T, Garty BZ, Ben-Baruch A. Cell migration to the chemokine CXCL8: paxillin is activated and regulates adhesion and cell motility. Cell Mol Life Sci 2009;66:884–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Frommhold D, Ludwig A, Bixel MG, Zarbock A, Babushkina I, Weissinger M, Cauwenberghs S, Ellies LG, Marth JD, Beck-Sickinger AG, Sixt M, Lange-Sperandio B, Zernecke A, Brandt E, Weber C, Vestweber D, Ley K, Sperandio M. Sialyltransferase ST3Gal-IV controls CXCR2-mediated firm leukocyte arrest during inflammation. J Exp Med 2008;205:1435–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sperandio M, Pickard J, Unnikrishnan S, Acton ST, Ley K. Analysis of leukocyte rolling in vivo and in vitro. Methods Enzymol 2006;416:346–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dixit N, Yamayoshi I, Nazarian A, Simon SI. Migrational guidance of neutrophils is mechanotransduced via high-affinity LFA-1 and calcium flux. J Immunol 2011;187:472–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cahalan MD, Chandy KG. The functional network of ion channels in T lymphocytes. Immunol Rev 2009;231:59–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Matheu MP, Beeton C, Garcia A, Chi V, Rangaraju S, Safrina O, Monaghan K, Uemura MI, Li D, Pal S, la Maza L D, Monuki E, Flügel A, Pennington MW, Parker I, Chandy KG, Cahalan MD. Imaging of effector memory T cells during a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction and suppression by Kv1.3 channel block. Immunity 2008;29:602–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dixit N, Simon SI. Chemokines, selectins and intracellular calcium flux: temporal and spatial cues for leukocyte arrest. Front Immunol 2012;3:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Levite M, Cahalon L, Peretz A, Hershkoviz R, Sobko A, Ariel A, Desai R, Attali B, Lider O. Extracellular K+ and opening of voltage-gated potassium channels activate T cell integrin function: physical and functional association between Kv1.3 channels and β1 integrins. J Exp Med 2000;191:1167–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Becchetti A, Petroni G, Arcangeli A. Ion channel conformations regulate integrin-dependent signaling. Trends Cell Biol 2019;29:298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kan XH, Gao HQ, Ma ZY, Liu L, Ling MY, Wang YY. Kv1.3 potassium channel mediates macrophage migration in atherosclerosis by regulating ERK activity. Arch Biochem Biophys 2016;591:150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wu B, Liu J, Bian E, Hu W, Huang C, Meng X, Zhang L, Lv X, Li J. Blockage of Kv1.3 regulates macrophage migration in acute liver injury by targeting δ-catenin through RhoA signaling. Int J Biol Sci 2020;16:671–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Grimaldi A, D’Alessandro G, Castro MD, Lauro C, Singh V, Pagani F, Sforna L, Grassi F, Angelantonio SD, Catacuzzeno L, Wulff H, Limatola C, Catalano M. Kv1.3 activity perturbs the homeostatic properties of astrocytes in glioma. Sci Rep 2018;8:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sperandio M, Quackenbush EJ, Sushkova N, Altstätter J, Nussbaum C, Schmid S, Pruenster M, Kurz A, Margraf A, Steppner A, Schweiger N, Borsig L, Boros I, Krajewski N, Genzel-Boroviczeny O, Jeschke U, Frommhold D, Andrian U. V. Ontogenetic regulation of leukocyte recruitment in mouse yolk sac vessels. Blood 2013;121:e118–e128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nussbaum C, Gloning A, Pruenster M, Frommhold D, Bierschenk S, Genzel-Boroviczény O, Andrian U. V, Quackenbush E, Sperandio M. Neutrophil and endothelial adhesive function during human fetal ontogeny. J Leukoc Biol 2013;93:175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Reeves EP, Lu H, Jacobs HL, Messina CGM, Bolsover S, Gabella G, Potma EO, Warley A, Roes J, Segal AW. Killing activity of neutrophils is mediated through activation of proteases by K+ flux. Nature 2002;416:291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Segal AW. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu Rev Immunol 2005;23:197–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Beeton C, Wulff H, Barbaria J, Clot-Faybesse O, Pennington M, Bernard D, Cahalan MD, Chandy KG, Beraud E. Selective blockade of T lymphocyte K+ channels ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a model for multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:13942–13947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Serrano-Albarrás A, Cirera-Rocosa S, Sastre D, Estadella I, Felipe A. Fighting rheumatoid arthritis: kv1.3 as a therapeutic target. Biochem Pharmacol 2019;165:214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kundu-Raychaudhuri S, Chen YJ, Wulff H, Raychaudhuri SP. Kv1.3 in psoriatic disease: PAP-1, a small molecule inhibitor of Kv1.3 is effective in the SCID mouse psoriasis - Xenograft model. J Autoimmun 2015;55:63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sarkar S, Nguyen HM, Malovic E, Luo J, Langley M, Palanisamy BN, Singh N, Manne S, Neal M, Gabrielle M, Abdalla A, Anantharam P, Rokad D, Panicker N, Singh V, Ay M, Charli A, Harischandra D, Jin LW, Jin H, Rangaraju S, Anantharam V, Wulff H, Kanthasamy AG. Kv1.3 modulates neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. J Clin Invest 2020;130:4195–4212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Devarajan P, Chen Z. Autoimmune effector memory T cells: the bad and the good. Immunol Res 2013;57:12–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cowburn AS, Condliffe AM, Farahi N, Summers C, Chilvers ER. Advances in neutrophil biology: clinical implications. Chest 2008;134:606–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Németh T, Mócsai A, Lowell CA. Neutrophils in animal models of autoimmune disease. Semin Immunol 2016;28:174–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thieblemont N, Wright HL, Edwards SW, Witko-sarsat V. Human neutrophils in auto-immunity. Semin Immunol 2016;28:159–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its Supplementary material online. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.